Abstract

Strengthening government guidance and policy support is an important path to promote digital transformation in various countries and enhance their core competitiveness in the digital era. This paper explores the differentiated feedback of enterprises with varying transformation costs in developing countries, using China as an example, towards government digital transformation policies. It finds that enterprises with low digital transformation costs provide positive feedback to government policies, while those with high costs exhibit limited and strategic feedback, resulting in differences in policy performance—specifically, innovation output. The analysis of mechanism indicates that lowering the costs of connectivity, integration, and financing for digital transformation will improve enterprises’ feedback on government-led policies and accelerate their own digital transformation processes. The capability to connect to the outside world, adapt to change, and mitigate financing constraints constructed by enterprises in the process of cost reduction will contribute to the development of their innovation activities, resulting in better innovation performance. The above logic is further verified empirically based on the quasi-experiment of Internet Plus promoted by the State Council of China in 2015. Therefore, to enhance the effectiveness of digital policies in developing countries, enterprises need to improve their dynamic adaptability and effectively reduce the costs of digital transformation. More importantly, the governments of developing countries should learn from developed countries in formulating digital transformation strategies and policies. They should create digital roadmaps suitable for their national development, forming targeted support policies for various types of enterprises, thereby providing real assistance for enterprises to break through and move forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research on corporate innovation behavior has a long-standing scholarly tradition. Early studies focused on internal firm-specific factors, including organizational characteristics (technological capabilities, human capital endowment, firm size, strategic orientation) and entrepreneurial attributes (founder background, risk propensity, age), to drive innovation (Barker and Mueller, 2002; Laforet, 2008). Recently, the rapid advancement of digital technologies has led to the emergence of research focused on innovation drivers from the perspectives of digital technology adoption and digital transformation, creating a vibrant and prolific field of study (Gao et al., 2022; Torre and Iván, 2025).

Digital transformation is the process by which businesses adapt to a changing environment by integrating digital technology to optimize resources, reorganize production methods, and enhance business models and culture for improved efficiency. (Heiferman et al., 2020). The booming development of digital technology driving the accelerated development of enterprise digital transformation practices. Many studies have found that digital transformation not only creates profound changes in society and industries at the macro level (Majchrzak et al., 2016), but more importantly at the micro level. On the one hand, digital technologies enhance corporate production management and supply chain optimization, not only improving operational efficiency but also creating significant competitive advantages and profit growth potential. Research indicates that technologies such as Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) and flexible production systems enable precise production scheduling, efficient logistics management, and optimal resource allocation, thereby substantially boosting productivity (Guchhait et al., 2024; Guchhait and Sarkar, 2024). Meanwhile, blockchain and Industrial Internet of Things (BIIoT) technologies strengthen supply chain coordination capabilities and elevate end-consumer experiences (Guchhait and Sarkar, 2024; Amankou et al., 2024). On the other hand, digital transformation has also induced organizational transformation, value discovery, and performance enhancement of enterprises (Nadkarni and Prügl, 2020; Clohessy et al., 2017). The reason is that the extensive use of digital technologies enhances the structural efficiency (Byun et al., 2018) and operational efficiency (Vial, 2019) of the enterprise’s organizational model while influencing the scale and convergence of information flows. It enables more effective innovations within the enterprise and promoting data as a new advantage feature. These studies provide valuable insights for systematically understanding how digital transformation is emerging as a pivotal force driving systemic organizational change and technological capabilities leapfrogging from an internal management perspective.

In essence, the systemic nature of corporate innovation reveals that innovation is not confined to internal firm factors—external elements such as institutional environments are equally critical (Shi and Wu, 2017). Particularly, governmental policies (Aschhoff, 2009) and other external environmental factors have emerged as significant forces shaping corporate innovation activities. Consequently, it is imperative to adopt a macro-level policy environment perspective to examine how government-led initiatives—including prioritizing enterprise digital transformation and implementing digital strategies—exert profound influences on micro-level corporate innovation behaviors.

Digital transformation has become an important hand for countries to enhance competitiveness, cultivate new kinetic energy, and improve innovation. Accordingly, in an effort to secure a leading position in industrial digitalization and digital technology innovation, many developed countries have proactively introduced relevant policies at an early stage. These policies are formulated in accordance with their respective factor endowments and industrial structures, aiming to facilitate the digital transformation of the manufacturing sector and foster the advancement of digital technology innovation: The United States focuses on cutting-edge technologies and high-end manufacturing industries, and has successively introduced the National Strategy for Advanced Manufacturing, the United States Government National Standards Strategy for Critical and Emerging Technology, and other plans. It provides multi-dimensional and long-cycle financial support and builds a nationwide innovation network to help enterprises leapfrog over the valley of death. The EU is constantly refining its strategic deployment of digital transformation. A new Industrial Strategy for a globally competitive, green and digital Europe explicitly proposes the creation of an open and collaborative innovation system and the cultivation of innovative enterprises as a path to ensure that the EU is a global leader in the industrial digital transformation. Japan proposed the development model of connected industry in 2017. Combined with its own characteristics, Japan has adopted diversified means to promote the implementation and promotion of connected industry. It strengthens funding for basic research and application of new-generation information technology and provides guidance for the development of key areas of the digital industry. In addition to developed countries, developing countries represented by Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) had also observed the opportunities brought by the new technological revolution to their development. And it had also promoted the implementation of digital transformation programs based on their own national conditions, increased the level of R&D investment in key areas, and created a favorable innovation ecosystem.

For many developed countries, the primary objective of digitalization policies is to enhance their competitiveness at the technological frontier. The core of these efforts is the pursuit of rule-setting power to sustain technological leadership. In promoting the enterprises’ digital transformation, these countries often maintain their traditional roles, primarily acting as regulators and ecosystem builders within the digital economy (Zahorodnia et al., 2021). Meanwhile, owing to their higher level of digital maturity, developed countries possess greater experience in formulating a clear strategic vision for national digital transformation. This includes the establishment of well-defined priorities and objectives, measurable targets, adequate financial and human resources, and comprehensive monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Consequently, their digital economy policies tend to exhibit clearer orientation and more robust institutional frameworks. Under the clear strategic guidance of the government, enterprises respond to market demands by continuously learning, experimenting, and innovating throughout the process of digital transformation. The extent to which enterprises align with governmental strategic objectives significantly influences the effectiveness of their technological transformation: Higher alignment tends to amplify the benefits derived from digitalization (Hong, 2024).

Government dominance is a relatively prominent feature in the development processes of developing countries (Adelman, 1999). Similarly, in the context of digital transformation, governments in developing countries often assume a direct and leading role. This is largely attributable to constraints such as limited resources, underdeveloped market mechanisms, and insufficient capabilities within the private sector. As a result, governments frequently undertake critical functions, including strategic planning, public investment, and regulatory oversight. Heeks (2010), in his analysis of the impact of ICT on developing countries, highlighted the necessity of government leadership in resource allocation and policy formulation. Echoing this perspective, the World Bank (2016) emphasized that “Without good governance, technological progress will be difficult to be transformed into productivity,” thereby underscoring the government’s role in digital infrastructure development and addressing the digital divide. Similarly, the Pathways for Prosperity Commission (2019) asserted that governments in developing countries must lead digital technology governance and steer market behavior by bridging digital inequalities. This view is further reinforced by the consensus in the literature that governments in developing countries are pivotal actors in driving digital infrastructure and institutional design (Avgerou, 2008), particularly in ensuring infrastructure development and universal connectivity (ITU, 2023). In practice, several empirical cases highlight the pivotal role of governments in developing countries as both institutional builders and market facilitators in the process of digital transformation (UNCTAD, 2019). For instance, the WoredaNet project in Ethiopia, initiated and led by the national government, has enabled the implementation of local-level digital governance by establishing a government communication infrastructure (Senshaw and Twinomurinzi, 2022). In Ghana, despite resource constraints, the government has actively promoted the development of financial technology (fintech), contributing to improved financial inclusion and innovation in digital payment systems (Senyo et al., 2024). Similarly, the Ugandan government played a foundational role in developing a national digital identity system, which laid the groundwork for broader participation in the digital economy during its formative stages (Iyer, 2021). These examples underscore the critical function of state leadership in shaping digital institutions and guiding market dynamics in resource-limited settings.

In both developed and developing countries, competition in industrial digital transformation and digital innovation has intensified significantly. Governments have introduced a range of strategies and policies, all centered on enhancing state support and guidance for the development of next-generation information technologies and the transformation and upgrading of key industries. The fundamental objective is to accelerate industrial digital transformation and promote the acquisition and mastery of core digital technologies. However, in developing countries, several challenges hinder effective digital transformation. On the one hand, as late entrants in the digitalization process, governments often have significantly less experience in strategic planning and policy-making compared to their counterparts in developed economies. It can lead to issues such as overly idealized policy objectives and a disconnect between policy implementation and the actual needs of enterprises, ultimately resulting in a mismatch between policy measures and enterprises’ real-world demands. On the other hand, a more pronounced issue lies at the micro level: Enterprises in developing countries often differ significantly from those in developed economies. Many enterprises face substantial capacity constraints and short-term survival pressures, and the greater heterogeneity among these enterprises can limit their ability to respond effectively to policy measures.

Therefore, when examining the policy detachment surrounding digitalization in developing countries—specifically, the challenges enterprises face during digital transformation—it’s crucial to consider the differences in costs among enterprises. The enterprise heterogeneity has garnered widespread attention in the economics literature since the 1990s—beginning with Bernard et al. (1987), who demonstrated that enterprises with varying productivity levels make different decisions regarding exports and foreign investment. Melitz (2003) further advanced the field by developing a seminal model of heterogeneous enterprises in international trade. Notably, enterprise heterogeneity is even more pronounced in developing countries than in their developed counterparts. Therefore, analyzing the varying motivations and economic outcomes of digital transformation based on cost heterogeneity is particularly relevant in the context of developing economies.

Since enterprise digitalization constitutes a form of technological upgrading and innovation, its success fundamentally depends on the realization of innovation outcomes. This raises a critical question: Why do enterprises in developing countries, despite operating under the same government-led policy environment, exhibit significant differences in both the process and outcomes of digital transformation? In other words, how does the divergence in innovation performance arise, and what drives the misalignment between enterprise-level digital transformation behaviors and government policy objectives? China, as the largest developing country and a representative case, provides a compelling context for examining this issue.

Compared with most developing countries, China’s economic development benefits from its strong state capacity. China’s economic development also benefits from the tenacity and resilience of the party and state system when compared to other transitional economies. In the realm of digital economy development, a notable distinction has been identified between the technological innovation models of the United States and China, particularly in the semiconductor industry. The Chinese model is characterized by a government-centered approach, wherein the state plays a leading role in driving technological innovation by formulating and implementing policies that mobilize the participation of multiple innovation actors. As a result, this paper takes China as a representative case to examine the heterogeneous responses of enterprises to government-led digital transformation policies and the resulting variation in innovation outcomes. To identify the above issues, this paper expands on two aspects. First, at the theoretical level, it constructs a logical self-referential framework that explains how different feedback to government-guided policies arises from variations in the costs of enterprise digital transformation, which subsequently leads to differences in transformation effectiveness. Second, at the empirical level, a quasi-experiment of Internet Plus promoted by the State Council of China in 2015 is used to verify the above theory. So, this paper seeks to explore how governments in developing countries can more effectively design targeted and context-specific guiding policies. Specifically, it emphasizes that the success of digital transformation policies hinges on lowering the response costs for enterprises and improving the practical operability of policy measures. In doing so, the paper aims to offer valuable insights and guidance for policymakers, regulatory bodies, and other stakeholders engaged in digital strategy formulation in developing countries.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Theoretical propositions” provides a framework. Based on cost heterogeneity, it explains a rationale and internal mechanism by which varied degrees of feedback from different enterprises about digital policies result in disparate policy outcomes. Section “Estimation strategy, variable descriptions and data” introduces the background of the policy, and illustrates econometric methods such as model setting and variable selection. Section “Empirical results” presents the analysis of the empirical results. Section “Conclusions” includes discussion of the study and the limitations.

Theoretical propositions

Stylized Facts

From a theoretical perspective, in developing countries such as China, the technical barriers and uncertainty risks inherent in enterprise digital transformation give rise to multiple forms of market failure within the digital economy. As a result, digital economy policies are expected to play a critical role in correcting these externalities and in stimulating as well as guiding the digital transformation processes of enterprises. Although China’s governments have introduced a number of digital incentives, from a practical point of view, there is a reality paradox in the feedback of enterprise digital transformation to government guidance policies: According to a McKinsey report, the failure rate of enterprise digital transformation is even as high as 80%. Digital transformation is inherently costly, time-consuming, and complex, posing significant challenges to the cash flow of many organizations (Chen et al., 2023). The Research Report on Digital Transformation of Chinese Private Enterprises 2022Footnote 1 also shows that China’s private enterprises, especially micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, are still in the early stage of digital transformation. It indicates a lack of consensus on digital strategy and a generally low evaluation of transformation effectiveness. At present, the overall level of digital transformation of Chinese manufacturing enterprises is low, as well as the level of application of advanced digital technology. The reason is that many enterprises believe that government support and supervision in digital transformation is insufficient, especially for the policy initiatives introduced by local governments to support the digital transformation of local enterprises. They believe that there may be a lack of relevance and implementation at the implementation level, so that the effect has not yet fully met their expectations. In this situation, it is essential to look at the gap between government ambition and market reality in the digital transformation process, particularly from the perspective of enterprise cost heterogeneity. This misalignment represents a structural challenge that must be addressed to enhance the effectiveness of digital transformation policies.

Responses of enterprises with heterogeneous cost to digital transformation policy guidance

While digital technologies have the potential to drive transformative change within enterprises, their adoption also introduces a range of risks. The substantial upfront investment required for advanced technologies—such as artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and blockchain—combined with the considerable costs of ongoing operation and management, presents significant financial and strategic challenges. Moreover, the implementation of these technologies can give rise to new technological and operational uncertainties, thereby elevating the overall risk exposure faced by enterprises (Chen et al., 2023; Zhou and Zhang, 2025). In addition, such adoption may alter internal control structures, increase governance-related risks, and generate substantial sunk costs (Heavin and Power, 2018). These risks and costs associated with digital transformation tend to vary significantly across enterprises, reflecting differences in enterprise characteristics.

In the face of digital development and the implementation of digital strategies, the government is a digital leader. The government can not only improve its service capability and governance level through digital transformation, but more importantly, it can guide, support and empower enterprises through digital means, that is, drive the advancement of enterprises’ digital transformation through policy guidance. When the government has complete information for enterprises with different digital transformation costs, it will provide differentiated policy guidance according to the specific characteristics of enterprises. At this time, enterprises can make necessary responses to government guidance policies to achieve the optimal of the whole society. In reality, when the government’s guidance policies are introduced, it is impossible to have a god perspective, that is, there is incomplete information about the transformation costs of enterprises. At this time, different enterprises will give differentiated feedback to the government’s indifferent guidance policies. The differentiated policy feedback is particularly pronounced in China and can be largely attributed to the high degree of cost heterogeneity faced by Chinese enterprises during the digital transformation process.

In China, the costs associated with digital transformation vary substantially across enterprises, depending on their size, ownership structure, and industry. These heterogeneous characteristics lead to notable differences in how enterprises respond to government guidance and policy incentives. First, at the enterprise size level, large enterprises generally possess greater financial, technological, and human resources, affording them a comparative advantage in implementing digital transformation initiatives. Moreover, they are more likely to access government subsidies, preferential loans, and participation in national-level digital pilot programs, thereby maintaining stronger institutional linkages with the state. In contrast, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often operate on a smaller scale, face weaker bargaining power within industry supply chains, experience more severe financing constraints, and exhibit lower risk tolerance. Additionally, SMEs typically lack a clear strategic understanding of digital transformation and have limited capacity to accurately assess both the costs and long-term benefits involved. As a result, they tend to be more sensitive to the high-cost nature of digital transformation (Zhu et al., 2023; Du, 2024). Second, at the ownership level, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China face a distinct set of institutional constraints arising from their unique structural characteristics (Shao, 2011). In particular, regulatory frameworks—such as the systems governing ownership rights and the appointment of enterprise leadership—exert a profound influence on the strategic behavior and developmental trajectories of SOEs (Huang et al., 2018). Compared with private or foreign-invested enterprises, SOEs are typically burdened with greater policy responsibilities, reflecting their closer alignment with government objectives and mandates (Liu et al., 2024). As a result, SOEs tend to be more proactive in responding to national initiatives such as the Digital China strategy. This responsiveness is partly due to their relatively weaker cost constraints and a greater tolerance for projects that may not yield immediate financial returns. SOEs are often able—and in some cases expected—to prioritize policy alignment over short-term profitability. In contrast, non-state-owned enterprises (NSOEs), operating under intense market competition, are primarily driven by efficiency considerations. Their digital transformation decisions are typically subject to stricter cost-benefit assessments. For many of these enterprises, the anticipated long-term gains from digital transformation are often outweighed by the substantial short-term costs, making them more cautious in their engagement with such initiatives. Third, at the industry level, the degree of factor intensiveness reflects varying technological foundations, levels of R&D investment, and capacities for technology absorption and integration across sectors. These differences contribute to significant variation in the costs associated with digital transformation. Digital transformation, defined as the adoption of digital technologies to induce substantial changes and improvements in an organization’s structure and processes (Vial, 2019; Verhoef et al., 2021), requires varying levels of readiness across industries. Enterprises in technology-intensive industries typically possess more advanced technical foundations, greater experience in R&D, and a more strategic orientation toward the integration of emerging digital technologies. Consequently, their costs of transformation tend to be relatively lower than those enterprises in labor-intensive or capital-intensive industries, which often lack the requisite technological infrastructure and capabilities (Zhao and Ren, 2023).

It follows that, differentiated by size, ownership, and industry, enterprises in China face varying digital transformation costs and durations of transitional pain periods. It is shaped by differences in access to critical resources such as technology, capital, talent, and data. Consequently, cost-heterogeneous enterprises exhibit divergent responses to government-led digital policy initiatives: Under various government incentives for digital transformation, enterprises’ feedback to government guidance is significantly different. The reason is that there are differences in the cost of digital transformation among different enterprises, so although the prospect of digital transformation is infinite, new digital risks will follow. Different enterprises have significant differences in the digital transformation ecology supported by multiple factors such as technology, capital, talent and data, which makes different enterprises have different digital transformation capabilities, costs and pain periods.

Alternatively, enterprises with relatively high costs will respond insufficiently to the government’s undifferentiated guiding policy of promoting digital transformation. It is because they have insufficient strategic deployment, a weak foundation, an unreasonable organizational structure, and a shortage of talent. They often adopt a small way to deploy digitalization. It is difficult to fully tap the value of digitalization, which makes the final innovation effect of digitalization limited.

Proposition 1: Due to the heterogeneity of digital transformation costs, enterprises present differentiated feedback to government guidance policies, and thus form different innovation effects.

Innovation effects of reducing the three types of costs: toward positive policy feedback

It can be seen that to form a consistent goal with the government digital guidance policy and then promote the vertical and horizontal fission of new technologies, new industries, new formats, and new models through digitization, enterprises need to reduce the cost of digital transformation through multiple means. Specifically speaking, the cost of digital transformation has three major dimensions: connection costs, integration costs, and financing costs.

Firstly, the reduction of the connection costs will enhance the capability of enterprises to connect with external relationships, creating a significant innovation effect

In the process of digital transformation, the Internet, open innovation platform and other channels can make it more convenient for enterprises to contact heterogeneous knowledge through cross-regional and cross-industry connection. It will expand the diversity of knowledge, provide more knowledge puzzles for innovation, and reduce the costs of connecting with external knowledge. Enterprises aiming to reduce connection costs during the process of digital transformation can effectively alleviate information asymmetry with lower search costs (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019). It helps enterprises to quickly identify innovation opportunities and expand their scanning of the innovation environment (Ghosh et al., 2022), then enhance their environmental sensing ability. Moreover, they can respond promptly to changes in the external environment, seizing fleeting innovation opportunities in a timely manner. By obtaining cooperative partners quickly and efficiently (Malhotra et al., 2005), enterprises can embed external knowledge into the internal R&D process relying on cross-border learning networks and ecological cooperation to reduce the trial-and-error cost. In addition, reducing connection costs for enterprises is conducive to the adjustment and optimization of their internal resource structure: By connecting multiple entities, it can break the barriers of traditional organizations and quickly absorb consumers’ feedback to optimize the direction of innovation. Then, it forms an adaptive innovation mechanism that iterates dynamically between learning, innovation, and relearning. In conclusion, the reduction of connection costs during the process of digital transformation makes the transmission of tacit knowledge more efficient by reshaping the dynamic abilities of enterprises to communicate and connect with the outside world (Forman and Zeebroeck, 2019). Through cognition, learning, absorption of external knowledge and reorganization of internal knowledge, the dynamic capabilities in searching for opportunities to transformation, learning transformation models from other enterprises, and adjusting the logic of previous actions have significantly improved (Warner and Wager, 2019). As a result, their feedback to government-guided policies will improve, which will further accelerate the improvement of innovation levels.

Secondly, the reduction of integration costs will enhance the organization’s own capability to adapt to change, creating a significant innovation effect

The disruptive changes caused by the new generation of information technology (Tapscott, 1995) require that business organizations need to change continuously during digital transformation, i.e., the ultimate goal is to form agile organizations (Heiferman et al., 2020). This is because the changes brought about by digital technologies have transformed the original sustainable competitive advantage of enterprises into a transient one, making it difficult to adapt to the existing environment. Therefore, in the digital era of the Internet of Everything, enterprises have to strengthen their adaptability to the new environment on the basis of the continuation of their previous resources and knowledge and the retention of their previous advantages. The core of enhancing the organization’s capability to adapt to change lies in the construction of dynamic capabilities with integration capabilities as the main content (Demeter et al., 2020), i.e., the improvement of the integration capability. It involves the ability of enterprises to formulate strategies and develop advanced solutions while adapting to digitization, to choose complementary products or service providers and platforms in implementation, and to utilize existing resources and apply them to products or strategies to cultivate new capabilities. And it is the key to enterprises’ successful participation in digital platforms or ecosystems (Vial, 2019). It is also an important dimension of enterprises’ innovation capability to improve integration among leadership, culture, business model, and digital architecture in digital transformation. Because the integration capability of enterprises in embracing the process of digitization can horizontally extend to the enterprise’s knowledge, technology, market, and enterprise itself aspects, achieving good and effective integration. According to Bloom et al. (2013), the supplemental improvement of all types of internal and external integration capacity will lower the cost of knowledge and information penetration. Therefore, enterprises can innovate at a lower trial-and-error cost. (Meng and Gong, 2024). The improvement of multi-dimensional integration and application capabilities will help to form the acquisition, absorption, and re-creation of various types of knowledge, and the source power of enterprise innovation will be more abundant.

Thirdly, the reduction of financing costs will enhance the capability of financing constraint alleviation, creating a significant innovation effect

Enterprise digitization requires continuous investment of funds, and the transformation risk is high, which is the reason why enterprises have doubts about the effect of digitization and low willingness to transform. If enterprises can effectively use the digital financing platform to crack the credit distortion caused by information asymmetry, explore through multiple channels and apply by multiple means, and reduce their financing costs under the condition of the digital economy, it will send a message to the market. That is, it signals the improvement of the capability of information processing and circulation efficiency. With a better understanding of the enterprise, banks and other external investors will demand a lower risk premium for them, thus reducing the enterprise’s financing costs. Enterprises not only use digital technology to seek to reduce financing costs, but also to re-engineer the financial system. Building a financial system with financial digitalization as the core can drive enterprises to reach the optimal expansion boundary under the limited financial resource boundary, improve their financial stability and reduce financial risks (Zhao et al., 2024). Thus, the enterprise digital transformation can improve the information asymmetry and strengthen the positive expectations of the market, as well as enhance the value of enterprises and financial stability (Xu et al., 2022), and in turn achieve the effect of lowering the financing costs. By reducing the financing costs, not only will the digital transformation dilemma be effectively resolved, but also the cost constraints on innovative activities that are long, risky, uncertain, and have a high failure rate will be significantly improved, and innovative activities will increase frequently.

Proposition 2: Enterprises can accelerate their own digital transformation by lowering the connection costs, integration costs, and financing costs of digital transformation, thereby providing positive feedback to the government’s guiding policies. In the process of cost reduction of digital transformation, enterprises will significantly improve their capability to connect with external relations, capability to adapt to change and capability to alleviate financing constraints, which will lead to a more significant innovation effect.

The above propositions and related logics are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Estimation strategy, variable descriptions and data

Background

Led by the construction of the Digital China, China is actively embracing the wave of digitization and seizing the commanding heights of global digital economy development. In December 2015, General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out at the opening ceremony of the Second World Internet Conference that China is implementing the Internet Plus initiative, promoting the construction of Digital China, developing the sharing economy, supporting all kinds of Internet-based innovations, and improving the quality and interest of development. Since then, under the unified leadership and deployment of the Central Committee of the CPC, the State Council, and governments at all levels, the construction of Digital China has been launched in full swing. The basic consensus is that China’s digital economic policy, implemented from 2015 onwards, is characterized by developing a model that integrates digital technology with industry and planning a program for the digital transformation of the real economy, centered around Internet + Industry. This policy initially opened up the pattern of China’s digital economy development.

In 2015, Guiding Opinions on Actively Promoting the Internet Plus Action (Opinions for short) was issued by the State Council. The core of the Opinions lies in the fact that the Internet is the underlying universal technology in the era of digital economy. The Internet economic model, leveraging contemporary information technologies, can optimize the stock and enlarge the incremental volume, facilitating the profound integration of traditional industries with the Internet sector, the advancement of intelligent manufacturing, and the emergence of novel business paradigms. And it will become the main form of China’s re-creation of its competitive advantages. The Opinions deployed Internet + Industry as the core of the real economy digital transformation plan, stressed the specific content and direction of the strengthening innovation-driven policy, and the promotion of NGIT to upgrade and industrialize the core technologies of key components. It can be seen that the Internet Plus initiative is the top-level design and specific government policy guidance for planning the enterprise digital transformation and promoting innovative development. However, the feedback of different enterprises to such specific guidance policies will be different, that is, the speed and degree of digital transformation will be significantly different. Accordingly, this paper uses the introduction of the Internet Plus initiative in 2015 as a policy shock, and adopt the Difference-in-Differences with a continuous treatment to systematically assess the differences in the feedback and innovation effects formed by enterprises on the government’s digitalization guidance policies and the corresponding channels of action, and verify the above theoretical hypotheses from an empirical point of view.

Estimation strategy

-

(1)

Benchmark model

The generalized difference-in-difference is used as the benchmark model, and is set as follows:

$${{Inno}}_{{it}}={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{{DID}}_{{it}}+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{{it}}+{\mu }_{i}+{\gamma }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{{it}}$$(1)where the dependent variable \({{Inno}}_{{it}}\) denotes innovation performance of enterprise \(i\) in year \(t\), including the number of patent applications and patent citations.\({{DID}}_{{it}}={{Digital}}_{i}\times {{post}15}_{t}\), where \({{Digital}}_{i}\) represents the level of digitization of enterprise \(i\), and \({{post}15}_{t}\) is a dummy variable of policy implementation. \({{post}15}_{t}\) equals to 1 if \(t\) is not less than 2015, otherwise it equals to 0. Although the policy is rolled out at the national level, the digital transformation level of different enterprises varies due to differences in transformation costs and feedback to the government’s digital guidance policy. Enterprises with higher feedback advance their digital transformation more deeply, with a relatively higher policy starting point and a stronger effect on innovation. \({X}_{{it}}\) are control variables of enterprises. \({\mu }_{i}\) and\({\gamma }_{t}\) are enterprise fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively. \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) are the error terms.

It is well known that the use of the Difference-in-Differences method presupposes that the prior common trend and the process of policy evaluation will not be disturbed by unobserved factors. So, the paper conducts a parallel trend test and designs a placebo test to confirm that the results of the benchmark regression are reliable.

In the parallel trend test, in order to compare the experimental group with the control group, it is necessary that the two groups have the same trend or no significant difference before the implementation of the policy. Since Internet Plus was launched simultaneously and indiscriminately across the country in 2015, there is no traditional experimental group or control group. However, a continuous variable, the level of digitalization, can be used to naturally group enterprises. In order to prevent the differences in innovation performance of different enterprises that existed before the implementation of the policy from interfering with the results, the method of event study to carry out the parallel trend test is adopted. The specific measurement model is as follows.

In order to avoid the affection of unobservable factors, which would lead to the model’s premise assumptions not being valid, a placebo test is conducted, and the form of the estimated coefficients can be rewritten as follows:

where \(C\) includes all control variables, time fixed effects, and individual fixed effects. \(\alpha\) represents the effects of unobservable factors on the dependent variable. If \(\alpha =0\), unobservable factors do not affect the estimation results. Specifically, the samples are re-estimated after randomization, and the randomization process is repeated 1000 times, thus obtaining 1000 estimated coefficients for DID.

-

(2)

Robustness test model

In the robustness test section, a DDD model and a PSM-DID are constructed. DDD model is constructed to introduce a third dimension to identify heterogeneous treatment effects of policy intervention across different groups through the difference between the treatment group and the control group. Considering that inter-regional differences in digital technology levels may have an impact on policy effects, this paper draws on a study (Liu et al., 2023) to construct a generalized DDD model. It helps to explain the impact of inter-regional digital technology levels on enterprises’ innovation performance based on comparing the differences in innovation performance after policy shocks for enterprises with different digitalization levels. The specific form of the model is as follows:

$${{patent}}_{{ijt}}={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{{DDD}}_{{ijt}}+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{{ijt}}+{\mu }_{i}+{\delta }_{j}+{\gamma }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{{ijt}}$$(3)where \({{DDD}}_{{ijt}}\) is the interactive term of DID and the variable of regional digital technology level. The regional digital technology level includes the size of digital talent pool (talent), the level of digital technology development (explore) and the level of digital technology service (service).

Generally speaking, a larger size of a region’s digital talent pool means a higher concentration of talent related to digital technology in this region, while the high-end talent combined with digital technology is the main force of enterprise innovation. In addition, the higher the level of digital technology development and services, the more widespread the adoption of digital technology in the region. The popularity of digital technology can accelerate the level of information sharing between departments of enterprises so that each department can efficiently integrate internal resources and strengthen the communication between R&D departments, thus promoting innovation efficiency (Feng et al., 2022). Besides, the higher the level of digital technology development and service, the closer the enterprise combines with digital technology in the process of R&D. On the one hand, the R&D department spills over to the application department with a high level of digital technology and innovation combined, providing advanced and diversified digital service platforms and digital thinking conducive to the change of the application department’s innovation mode; on the other hand, the promotion of digital technology in the application department provides the main body of innovation with efficient innovation services, enhances the commercialization capacity of new technologies, and releases the innovation spillover dividends of the application department (Feng et al., 2023). Therefore, the paper first uses the scale of regional employees in the information transmission and software industry to characterize the scale of the regional digital talent pool. Secondly, in terms of measuring the level of regional digital technology development, this paper adopts the indicators of value of contract inflows to domestic technical markets by region, the amount of regional technology introduction, the amount of regional technology development, internal R&D expenditure of the electronic and telecommunications equipment industry, and internal R&D expenditure of the computer and office equipment manufacturing industry to build a comprehensive index, which is calculated by the entropy method. Thirdly, it uses the proportion of high-tech product exports to total exports and regional software business revenue as the measure of the level of regional digital technology service. The data are all from China Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook on Science and Technology, China Statistical Yearbook on High Technology Industry, and China Statistical Yearbook on Electronic Information Industry. \({\delta }_{j}\) are region fixed effects, and the meanings of other variables are the same as in the previous section.

In terms of PSM-DID model, differences in policy effects due to differences in digitization levels will affect the innovation performance of enterprises. In order to avoid selectivity bias, this paper adopts the generalized propensity score matching method (GPS) to ensure reasonable comparison between the control group and the processing group. The advantage of the GPS lies in its capability to deal with multivariate or continuous variables, which not only has the characteristics of solving the endogeneity problem of variables in general PSM, but also can make full use of sample information. Accordingly, a counterfactual framework is further constructed to portray a dynamic description of the causal effects between enterprises at different levels of digital transformation and their innovation performance. Therefore, the innovation performance between any two enterprises at different levels of digitalization can be clearly compared.

The covariates selected include the proportion of digital intangible assets (Asset), the level of human capital (Human), the size of the enterprise (Size), the educational background of executives (Edu), the proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder (Top1) and the equity nature of the enterprise (EquityNature): (i) Digital assets are essential in the process of enterprise digital transformation, and the integration of innovation and digital assets is a key booster to improve the efficiency of enterprise innovation. This paper uses the ratio of the digital economy-related part in the intangible assets details, which are disclosed in the notes of listed enterprises’ financial reports, to the total intangible assets to indicate the digital assets of enterprises. (ii) Digital assets need to be combined with high-end human capital so that the enterprise digital transformation can be efficiently promoted. Thus, the proportion of skilled employees of enterprises is used to measure the level of human capital (Che and Zhang, 2018). (iii) To some extent, the size of the enterprise is one of the key factors influencing the adoption and diffusion of enterprise digital transformation (Zhu et al., 2006), so it is selected as a covariate. (iv) Another key element for the success of digital transformation is the talent with digital development thinking and leadership. As educational background, to a certain extent, represents leaders’ base of knowledge and ability, general manager’s education background is used to characterize the educational background of executives, which equals to1 if the general manager has a bachelor’s degree or above, and 0 otherwise. (v) The proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder reflects the concentration of the enterprise’s ownership. If the proportion is too high, it is difficult to avoid the risk of decision-making errors, and it will influence the decision of digital transformation due to information asymmetry. (vi) The equity nature affects the urgency and possibility of the enterprise digital transformation.

-

(3)

Mechanism model

In the mechanism discussion above, in order to form positive feedback to the policy in digital transformation, the key is to reduce various types of costs in digitization so as to accelerate enterprise digital transformation. Only through cost reduction in digital transformation can enterprises improve their capability to connect with external relations, capability to adapt to change and capability to alleviate financing constraints, which will make digital transformation produce more significant innovation effects. Therefore, this paper further constructs mediator variables to characterize this mechanism. The traditional mediation effect test is being rethought by international academics (Bullock et al., 2010), according to which some scholars have proposed a common improvement practice, i.e., when there is an intuitive causal relationship between the mediator variable and the dependent variable theoretically, it is possible to only examine the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable as well as the effect of the mediator variable on the dependent variable, so as to avoid unexplained direct effects. Since the relationship between the improvement of the three capabilities and the innovation performance of enterprises is logically clearer, the following model is constructed to discuss the mechanism. The specific model is as follows:

$${M}_{{it}}={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{{DID}}_{{it}}+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{{it}}+{\mu }_{i}+{\gamma }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{{it}}$$(5)where \({M}_{{it}}\) includes indicators for the capability to connect with external relationships, the capability to adapt to change, and the capability to mitigate financing constraints.

The meaning of each notation can be summarized in the following table:

Variable descriptions

-

(1)

Innovation performance of enterprises. The enterprise innovation emphasized in this paper focuses on the impact on the output side. Compared with R&D expenditures, measuring enterprise innovation by patents has some obvious advantages. As a result, this paper uses the natural logarithm of the number of patents applied (Inno_apply) by enterprises as the measure of enterprise innovation performance. Considering only by the number of patent applications might overlook qualitative differences of innovation, the natural logarithm of the number of patent citations (Inno_cite) is introduced as a Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1 Meaning of notation in the models. -

(2)

Enterprise digital transformation level. On the portrayal of the degree of enterprise digital transformation, this paper uses crawler technology to extract digital-related words from enterprise annual reports and conducts word frequency analysis. Zhao et al. (2023), Wang et al. (2023), and Qi et al. (2022) use text analysis to construct a more comprehensive reflection of the Chinese listed enterprises’ indicators of the degree of digitization. The vocabulary in annual reports can reflect the strategic characteristics and future outlook of enterprises, as well as their business philosophy and development paths. Therefore, this paper draws on the practice of existing studies, making use of the text of listed enterprises’ annual reports on artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud computing, big data, digital technology application and other keywordsFootnote 2 to construct the text intensity of digital transformation. That is, add 1 to the word frequency and take the natural logarithm to get the final enterprise digital transformation index (Digital).

-

(3)

Control variables. The selection of control variables mainly refers to Hu and Yang (2022), Yu and Hu (2023), and Xia and Jia (2023), which consider the duration of enterprise survival (Age) and related financial data, such as enterprise growth (Grow), return on assets (Roa), debt ratio (Lev), liquidity (Liq), enterprise value growth (Vag). In addition, fix effects of industry (Industry), location (Location) and year (Year) are added. The specific calculations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Definition of variables. -

(4)

Mechanism variables.

-

a.

Connection costs: the capability to connect to external relationships (Con). Focusing on the impact of digital transformation on the level of innovation, the absorptive capacity of enterprise proposed by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) is used to characterize the capability of enterprise to connect to external relationships. The absorptive capacity of an enterprise includes knowledge acquisition capacity, knowledge absorption capacity, knowledge transformation capacity, and knowledge utilization capacity. When an enterprise is able to develop a better capability to absorb external knowledge in the process of digital transformation, it indicates that the enterprise has a stronger capability to connect to external heterogeneous knowledge. Generally speaking, R&D intensity is a common measure of an enterprise’s absorptive capacity, so the natural logarithm of R&D expenditures is used to measure the absorptive capacity of the enterprise. In order to avoid losing the observation that R&D expenditure is zero, this paper takes the natural logarithm after adding one to R&D expenditure to construct the proxy variable for the capability of enterprises. to connect with external relationships.

-

b.

Integration costs: the capability to adapt to change (Adm). The level of corporate governance is used to characterize the level of capability to adapt to change. With a high level of governance, enterprises are generally more energetic and have a relatively strong capability to adapt to the changes and innovations in the process of digital transformation, which can make an obvious innovation performance. It has been argued that the board of directors is the core of the modern corporate governance structure, and the introduction of independent directors improves the independence of the board of directors and then improves the quality of corporate decision-making (Han et al., 2023). Accordingly, the number of independent directors is introduced as a proxy variable to measure the level of corporate governance. If the number of independent directors is greater than one-third of the number of board members, the indicator is assigned a value of 1. Otherwise, the indicator is assigned a value of 0. It can eliminate the problem of false governance to a certain extent.

-

c.

Financing costs: the capability to alleviate financing constraints (FC&KZ). Drawing on Kaplan and Zingales (1997) and Hadlock and Pierce (2010), financial constraints can be measured by the FC index and the KZ index. The larger the FC index and the KZ index, the stronger the financing constraints. The specific models of FC index are as follows:

$${\rm{P}}\left({\rm{FC}}=1\,{\rm{or}}\,0|{Z}_{{it}}\right)=\frac{{e}^{{Z}_{{it}}}}{1+{e}^{{Z}_{{it}}}}$$(6)where

$${Z}_{{it}}={\alpha }_{0}+{\alpha }_{1}{{size}}_{{it}}+{\alpha }_{2}{{lev}}_{{it}}+{\alpha }_{3}{\left(\frac{{CashDiv}}{{ta}}\right)}_{{it}}+{\alpha }_{4}M{B}_{{it}}+{\alpha }_{5}{\left(\frac{{NWC}}{{ta}}\right)}_{{it}}+{\alpha }_{6}{\left(\frac{{EBIT}}{{ta}}\right)}_{{it}}$$(7)where \({size}\) denotes the size of the enterprise’s assets, measured by the natural logarithm of total assets; \({lev}\) is the asset liability ratio; \({CashDiv}\) is the cash dividend paid by the enterprise in that year; \({MB}\) is the ratio of market-to-book of the enterprise, which is calculated by dividing market value by book value; \({NWC}\) is net working capital, equal to working capital minus money capital minus current investments; \({EBIT}\) is earnings before interest and tax, and \({ta}\) represents total assets.

-

a.

And the specific models of KZ index are as follows:

where \({CF}\) is net operating cash flow; \({ASSET}\) is asset of the enterprise; \({LEV}\) is the asset liability ratio; \({DIV}\) is cash dividend; \({CASH}\) is cash holdings, and \(Q\) is value of Tobin’s Q.

(5) Heterogeneity test variables. The scale, equity nature and industry of enterprises are selected for heterogeneity test. First, the scale of enterprises is divided into three types—large, medium and small—based on the tertiles of total assets, and SMEs are merged. The value for large enterprises is 1, and for SMEs, it is 0. Second, in terms of equity nature, the value for SOEs is 1, and for NSOEs, it is 0. Thirdly, referring to Liu et al. (2023), enterprises are classified into labor-intensive, capital-intensive and technology-intensive according to their industries. The value of labor-intensive is 0, that of capital-intensive is 1, and that of technology-intensive is 2.

Data sources

The R&D and innovation data of listed enterprises used in this paper come from the Chinese Innovation Research Database(CIRD) of the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS),Footnote 3 and other relevant indicators about listed enterprises come from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research(CSMAR), including China Listed Firm’s Financial Reporting Database, China Listed Firm’s Financial Indicators Analysis Database, China Listed Firm’s IPO Database and China Listed Firm’s Financial Statements Notes Database. This paper uses the stock code of listed enterprises as the matching label. In addition, missing data are filled in by manually searching through the Flush software, such as the establishment date and ownership form of individual enterprises. The word frequency data of enterprise digitalization level is obtained by using Python to crawl the keywords related to digitalization in the annual reports, which are identified in the previous section, then making word frequency statistics and text analysis.

Since China’s listed enterprises began to implement the new accounting standards in 2007, it is set as the starting year to ensure the consistency of the caliber of calculation of the relevant accounting data. In addition, there was almost no enterprise digital transformation before 2007, so it is appropriate to choose this starting point. In order to make the data more representative, enterprises with abnormal listing status and those with special treatment are excluded. To eliminate the interference of outliers on the results, a two-sided 1% shrinking tail treatment (winsor) is applied to the key indicators. Finally, there are 15,959 sample data of listed enterprises from 2007 to 2020.

Empirical results

Benchmark regression

Table 3 reports the results of the DID regressions using the Internet Plus strategy (2015) as an exogenous shock. For the number of patents applications and patents citations, whether to join the control variable or not, the coefficient of DID is positive and statistically significant at 5%. This suggests that in the average sense, the layout and planning of the Internet Plus strategy in the digital economy era has a significant effect on the improvement of enterprises’ innovation performance. It further suggests that different enterprises have different levels of digital transformation due to different feedback on the government’s guidance policies. The positive regression coefficient also implies that enterprises with better feedback to the policy have higher levels of digital transformation, which have a greater effect on enterprise innovation performance with the help of the Internet Plus strategy. And hypothesis 1 is confirmed. It can be said that the more consistent the enterprises are with the policy objectives guided by the government in the process of digital transformation, i.e., the lower the cost of their digital transformation, the stronger the innovation effect will be with the support of the government’s effective assistance. Fig. 1.

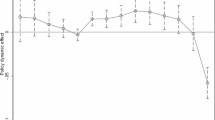

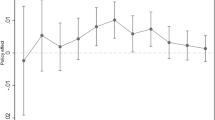

Figure 2a, c show the results of the parallel trend test. It can be seen that the null hypothesis that the coefficient is 0 cannot be rejected by the variable DID before 2015.The coefficient of DID has no significant trend and is fluctuating around 0, indicating that the parallel trend is satisfied. As to the patents applications, after the implementation of the policy, \({\beta }_{t}\) is significantly not 0, with a clear increasing trend, indicating that the effect of the policy exists. However, the persistence of the policy is not strong: The duration is only 4 years, and there is a decreasing trend from 2019. However, the treatment effect about patents citations is even less obvious, and the coefficient is always positive.

Figure 2b, d report the probability density distribution of 1000 estimated coefficients by 1000 random processes, which have much smaller mean values than the coefficient estimates of the baseline model (0.870 and 1.116). As can be seen from the figure, the randomly assigned estimated coefficient values are centrally distributed around 0, which is basically in line with the normal distribution, indicating that the sample is free from the interference of the random factor, and the results of this model are reliable.

Robustness test

To ensure the reliability of the estimation results, this part further tests the robustness of the model in the following aspects.

-

(1)

Replace dependent variable and independent variable. Generally speaking, in the research of enterprise innovation, the basic consensus is that invention patents belong to substantive innovation or breakthrough innovation, so the total number of invention patents enterprises applications and the total number of invention patents enterprises citations are taken as the dependent variables. According to the study of Zhou et al. (2022), the digital transformation of enterprises can be replaced by a dummy variable did, i.e., whether to implement digital transformation, which equals to 1 if the frequency of words related to digital technology is greater than 0, and 0 otherwise. Column (1) and column (5) show that the coefficient of DID is positive and significant, which is consistent with the results of the benchmark regression. Column (2) and column (6) show that enterprises that respond positively to policies have better innovation performance.

-

(2)

Add province fixed effects and industry fixed effects. Most enterprises do not change provinces and industries, but ignoring this possibility may lead to biased and inconsistent estimation results, so province fixed effects and industry fixed effects are added. Column (3) and column (7) show shows that the model is still robust after adding those fixed effects. Column (4) and column (8) show the results of adding interactive fixed effects, which are used to control for the impact of unobservables at the industry level in different provinces on enterprises’ innovation performance. The advantage of controlling for such a set of fixed effects is that the variation used to identify the coefficients of the key independent variable is from across enterprises within the same industry and within the same province, making the coefficients more accurate. The results are still robust. Table 4.

Table 4 Robustness test. -

(3)

Construct a difference-in-differences-in-differences (DDD) model with a continuous treatment. The results of the model are shown in Table 5. It shows that whether control variables are added or not, the coefficients of DDD are significantly positive. That is, the higher the level of regional digital technology and the level of enterprise digitalization, the more obvious the policy effect is, and the innovation performance of enterprises can be improved to a higher level.

Table 5 DDD model. -

(4)

Construct PSM-DID model. The results of the PSM-DID are shown in Table 6. The conditional distribution of the digitization level of the treatment variables is first estimated with the given covariates. Since the treatment variables do not follow a normal distribution, the Fractional Logit model is used for estimation. In column (1), it can be seen that the coefficients of each covariate pass the significance test, and the value of AIC is 0.9467, which indicates that the setting of the model and the selection of covariates are reasonable. From the estimation results, except the coefficients of Top1 and EquityNature are negative, the coefficients of other covariables are positive. It indicates that elements such as enterprise digital assets and human capital can contribute to the level of digitization, and larger enterprises are faster in advancing the process of digital transformation, making them have a higher level of digitization. In addition, the higher the education level of executives, the stronger the management coordination ability and decision-making ability, and the faster the speed of digital transformation. But excessive concentration of equity will have a negative impact on the digital transformation, and SOEs are not performing well in the process of the digitization. Column (2) and column (3) show the re-estimated results of policy effects using GPS, and it can be seen that there is no significant change, indicating that the results above are robust.

Table 6 PSM-DID model.

Heterogeneity analysis

In order to avoid the accuracy bias of conclusions caused by sample loss, full sample method of heterogeneity analysis is adopted, that is, the interaction term between variables of enterprise characteristics and dependent variable is introduced for regression. Moreover, only the number of patent applications is used as the dependent variable as the main regression for heterogeneity analysis.

Table 7 shows the results. Columns (1) shows that compared with SMEs, large enterprises have better feedback on government guiding policies during digital transformation and have a more significant promoting effect on their innovation performance. This also confirms that large enterprises have relatively complete governance structures and the ability to cooperate and communicate with other R&D organizations. They perform better than SMEs in responding to the government’s digital guidance policies and forming their own consensus on digital strategies. Column (2) indicates that compared with NSOEs, SOEs respond more actively to the government’s digital guidance policies. On the one hand, SOEs, as an important pillar of the national economy, undertake the responsibility of achieving major national strategic goals. Therefore, actively responding to the call of national policies is their obligation and mission. On the other hand, SOEs are backed by the government. The abundant resource and policy support enable them to promote digital transformation at a relatively low cost. However, in the face of complex external risks and resource pressure, NSOEs need to make decisions prudently based on their own development path. The results of column (3) about the industries of the enterprises show that the innovation performance of technology-intensive enterprises in digital transformation is significantly better than that of capital-intensive and labor-intensive enterprises, which verifies the theoretical discussion in the previous section.

Mechanism: based on the capabilities constructed in digital transformation

Further, according to Eq. (5), Table 8 shows the logic that the reduction of three kinds of transformation costs and the improvement of the three major capabilities built by enterprises in digital transformation affect innovation. Since mechanism identification focuses on the effects of localized independent variables on dependent variables, only the direct effects of the key variables are reported. Column (1) illustrates that in the face of the government’s digital guidance policy, enterprises can form more effective feedbacks by lowering connection costs, and their capability to identify and acquire external knowledge and information is also enhanced, which significantly contributes to the innovation performance of enterprises. Column (2) reports the effect of the capability to adapt to change, where in the face of the same guidance policy, the enterprises with a stronger capability to adapt to change have more significant innovation performance in digital formation. Column (3) and column (4) report the mediation effect of the capability to alleviate financing constraints on innovation. The application of enterprise digital technology will form a signal release effect, that is, strengthen the positive expectations of the market, so as to achieve the effect of reducing costs through financing and provide sufficient financial support for enterprise innovation.

Conclusions

To elucidate how government policies can more effectively empower enterprises in their digital transformation and provide references for the formulation and implementation of digital economy policies, this paper examines the issue from the perspective of enterprise cost heterogeneity. It argues that in many developing countries, notably China, enterprises exhibit substantial differences in the costs associated with digital transformation. These cost disparities lead to heterogeneous responses to government-led digitalization policies. Under uniform conditions of governmental guidance and policy support, enterprises with lower costs tend to align more closely with governmental digitalization objectives, thereby achieving greater innovation outcomes. In contrast, enterprises facing higher costs are more likely to experience misalignment with policy goals, resulting in comparatively weaker innovation performance. Furthermore, the paper posits that reducing the connection, integration, and financing costs of digital transformation significantly enhances enterprises’ responsiveness to policy guidance and accelerates their digital upgrading processes. During the process of cost reduction, the construction of capabilities related to external connectivity, adaptability to change, and alleviating financing constraints plays a pivotal role in fostering innovation. In addition, this paper tests the proposed theoretical framework using a quasi-experiment based on the China government’s launch of the Internet Plus initiative in 2015. The results demonstrate that enterprises with lower digital transformation costs exhibit more positive responses to government policy guidance and achieve more pronounced innovation effects.

Therefore, for many developing countries, to address the digitalization policies’ detachment and enhance government guidance and policy design to promote the digital transformation process in their own countries, there are two core policy implications at the following levels:

First, for enterprises in developing countries, overcoming the dual challenges of knowledge transformation and digital transformation under government policy guidance requires enhancing their digital governance capabilities and dynamic adaptability while effectively minimizing the costs associated with digital transformation. Enterprises should clear the direction and path of their digital transformation through adequate top-level planning and detailed digital transformation action plans. On the basis of clear objectives, building the dynamic capability of the enterprise as an adaptive subject is the core of enterprise digital transformation. It is necessary to not only accelerate the transformation of management thinking and corporate culture, but also comprehensively promote the digitalization from strategy to business and from internal control systems to outreach. At the same time, the government should fully recognize the value of digital talents and give them corresponding policy supports to solve the problem of unable to transform. In this process, it is important to take multiple measures to reduce the costs of digital transformation, such as promoting the transformation of enterprises into agile organizations and building endogenous digital teams, in order to crack the bottleneck of cost input.

More importantly, governments in developing countries should learn from the advanced experiences in digital strategy formulation of developed countries like European Union and the United States, taking on the role of latecomers. Specifically, when designing national digital strategies, developing countries should draw lessons from initiatives such as the EU’s Digital Compass and the U.S. National Strategic Plan for Advanced Manufacturing. A tailored digital transformation roadmap should be formulated in accordance with national development conditions, incorporating clearly structured short- and medium-term goals while avoiding abrupt or unsustainable policy shifts. Furthermore, it is essential to define explicit and measurable key performance indicators (KPIs)—such as the rate of digital skills diffusion, the adoption rate of digital technologies among SMEs, and the level of digitalization in public services. These indicators can provide critical references for both policy evaluation and enterprise decision-making. In addition, developing countries should emulate the practice of classification-based guidance and sector-specific support commonly found in the digital strategies of developed economies. Recognizing the heterogeneity of domestic enterprises, governments should identify priority sectors and emphasize implementable technologies to formulate differentiated and targeted support policies. Such policies can offer tangible assistance to enterprises striving to overcome transformation barriers.

It is also imperative to establish robust policy implementation and feedback mechanisms. Drawing on international experience, governments should enhance interaction and dialog with the business community via industry platforms and institutionalize feedback channels to gather enterprise-level input. These measures will enable the development of a dynamic, responsive framework for policy refinement. Finally, in line with the practices of developed countries, developing economies should advance digital talent development strategies and promote the digitalization of public services. These efforts can foster a supportive ecosystem for digital transformation and effectively lower entry barriers for enterprises across sectors.

There is no denying that this paper has some limitations. First, this paper examines the interaction between government and enterprises within the framework of information asymmetry. Specifically, it posits that governments are unable to fully observe the heterogeneous digital transformation costs faced by enterprises during the policy formulation process. In contrast, enterprises—owing to their informational advantage—can engage in strategic feedback behavior based on their individual cost structures, thereby limiting the overall effectiveness of policy implementation. However, the current analysis in this paper does not develop a formally theoretical model to capture this mechanism, which remains a foundational direction for future research. Second, with respect to the measurement of heterogeneity in enterprises’ digital transformation costs, this paper adopts an indirect approach. It infers cost differences from the observed speed and extent of digital transformation, under the assumption that faster digitalization implies lower transformation costs, and vice versa. While this serves as a useful proxy, future research should aim to construct more precise cost indicators using textual analysis and financial data at the enterprise level to improve measurement accuracy and deepen the empirical analysis. Third, regarding empirical strategy design, this paper relies on a single government digital policy initiative, namely the Internet Plus action, as a quasi-experiment. As a result, it does not capture the broader landscape of digital policy instruments, nor does it assess potential policy interactions or synergies. Exploring the effects of multiple policy interventions and their complementarities represents another important avenue for future inquiry.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the high cost of manual data collection and the need for follow-up studies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

It can be seen in the Research Report on Digital Transformation of Chinese Private Enterprises 2022, published by the China General Chamber of Commerce (CGC) and the Tencent Research Institute.

Artificial Intelligence technologies include: Artificial Intelligence, Business Intelligence, Image Understanding, Investment Decision Support System, Intelligent Data Analysis, Intelligent Robot, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Semantic Search, Biometric technology, Face Recognition, Speech Recognition, Authentication, Autonomous Driving, Natural Language Processing; Blockchain technologies include: Digital Currency, Intelligent Contracts, Distributed Computing, Decentralization, Bitcoin, Alliance Chain, Differential Privacy technology, Consensus Mechanism; Cloud Computing technologies include: Memory Computing, Cloud Computing, Stream Computing, Graph Computing, Internet of Things, Multi-party Secure Computing, Brain-inspired Computing, Green Computing, Cognitive Computing, Converged Infrastructure, Billion-level Concurrency, Exabyte Storage, Cyber Physical Systems; Big Data technologies include: Big Data, Data Mining, Text Mining, Data Visualization, Heterogeneous Data, Credit, Augmented Reality, Mixed Reality, Virtual Reality; digital technology applications include: Mobile Internet, Industrial Internet, Internet Healthcare, e-commerce, Mobile Payment, Third-Party Payment, NFC payment, B2B, B2C, C2B, C2C, O2O, Netflix, Smart Wearable, Smart Agriculture, Smart Transport, Smart Healthcare, Smart Customer Service, Smart Home, Robo-Advisor, Smart Cultural Tourism, Smart Environmental Protection, Smart Grid, Smart Energy, Smart Marketing, Digital Marketing, Unmanned Retail, Internet Finance, Digital Finance, Fintech, Quantitative Finance, Open Banking.

The quality of R&D expenditures, patents, and other data of listed companies published by the Chinese Innovation Research Database (CIRD) from the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS) is significantly better than that of China Listed Firm’s Patent Research Database in the CSMAR database, and the data related to R&D and other data of listed companies published in CSMAR are cluttered, and have too many missing values. By contrast, the data from CIRD of CNRDS have a high integrity based on the time dimension.