Abstract

Computer-mediated communication is so popular in social interaction that Cyberpragmatics has been formulated to study emojis from the perspective of Relevance Theory. According to Relevance Theory, individuals tend to select information that provides the most significant cognitive benefits while requiring the least processing effort during comprehension. Emojis, as concise and efficient communication stimuli, can demonstrate how interlocutors of different ages adjust their processing effort in response to contextual effects. However, most previous studies focused on specific English emojis in a particular age group. Little attention has been paid to the rules governing emoji usage for different age groups in the Chinese context. We contend that a productive way to examine emoji usage is by considering the different cognitive processes involved in different usages, specifically using Yus’s relevance-theoretic model, Cyberpragmatics. We proposed five pragmatic functions of emojis (i.e., filling, enhancing, weakening, challenging, and substituting) and believed these five functions could cost different processing efforts and produce different contextual effects. The “filling” function involves adding emotional expression to otherwise neutral or emotionless text, while the “enhancing” function refers to amplifying the emotional expression in a text that already conveys an emotional tone. The “substituting” function works when emojis replace verbal elements to assist in conversational management, such as turn-taking and backchannel cues. The “challenging” function involves emojis contradicting the explicit content of utterances, while the “weakening” function pertains to mitigating the illocutionary force of a speech act. Furthermore, employing a mixed method, this study investigated how younger and older individuals on WeChat used these five emoji functions. The results demonstrated that the younger and older groups exhibited variations in how they chose emojis to achieve relevance. The older adults preferred to conserve efforts, whereas the younger individuals sought to maximize contextual effects with less concern for efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) refers to any form of communication through digital devices and networks. It involves communication via email, instant messaging, social media platforms, and other digital means. CMC facilitates interaction between individuals or groups regardless of geographical distance, allowing for exchanging text, images, audio, and video in real-time or asynchronously. In this study, CMC means communication on mobile devices. Exploring various language forms leads to a deeper comprehension of discourse phenomena in an era where emoji communication plays a critical role, sometimes even surpassing textual communication. New theories have been formulated to study CMC, such as Cyberpragmatics, which builds on Relevance Theory by applying its core principles to the context of internet-mediated communication and examining how relevance-oriented cognitive processes shape online interactions (Yus, 2016). According to Relevance Theory, communication is guided by the principle of relevance, with individuals focusing on stimuli that are deemed potentially relevant while disregarding those considered irrelevant (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 63).

Emotion can be inferred and interpreted through a stimulus in ostensive-inferential communication. Emojis are a unique stimulus in CMC to express, interpret, and infer emotions. It is assumed that each used emoji carries an inherent potential for optimal relevance, which can be achieved through its ability to produce specific contextual effects. An emoji is considered relevant to an individual when the contextual effects it generates upon optimal processing are significant, while the cognitive effort required for such processing is minimal. This study aims to explore how younger and older Chinese adults use emojis to achieve relevance on WeChat, focusing on generational variations. The findings are expected to contribute significantly to advancing the field of discourse studies.

A widely used social media platform that provides insight into emoji usage within a Chinese context is WeChat, a multifunctional application that integrates messaging, social networking, and various digital services. It was launched by Tencent in China in January 2011 with advances in Internet and smartphone technology. As an intelligent application for instant messaging, it can send messages across vast distances almost instantaneously, freed from time and space constraints. WeChat’s built-in emoji keyboard and its integration with a wide range of expressive, animated emojis make it an ideal choice for examining emoji usage in everyday CMC communication. Characterized by its simple operation and straightforward interface, WeChat has become one of the most popular social media platforms, with many active users of diverse ages. The large user base and complexity of users’ demographic structure determine the diversity and discrepancies in WeChat conversation features. Age makes a difference in interactive behaviors, such as formulating the proper messages for communication (Yan and Sorenson, 2004). Age-related differences in communication styles shape how emojis convey meaning and establish relevance in conversations.

Emojis are extensively used in WeChat conversations to make up for the absence of facial expressions in CMC. They originated from emoticons created by Scott Fahlman around the 1980s, which were essentially ASCII glyphs utilized to express an emotional state in email or news, such as smiley face “:-)” for humor, laughter, friendliness, occasionally sarcasm, and frowny face “:-(” for sadness, anger, or upset. Emojis and stickers are novel forms of emoticons that keep pace with communication technology as unique and effective devices in CMC systems, leading to more interesting, creative, and relaxing interactions. In this study, emoticons, emojis, and stickers will be used with parallel definitions and taken into consideration, referred to collectively as emojis. Examining the usage of emojis is anticipated to enhance the effectiveness of communication in WeChat interactions. Moreover, emoji usage and comprehension are closely related to age, leading to the phenomenon that older users employ emojis differently from younger ones (Koch et al., 2022). However, how age influences emoji usage, especially in the Chinese context, remains underexplored and hence is our core research question in this study.

Our study engages with the comprehensive emoji system in WeChat discourse to investigate the differences in emoji usage between younger and older individuals from the perspective of Relevance Theory (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). It mainly focuses on the following questions: (1) What are the patterns of frequency and proportion of these functions? (2) How are these functions distributed among younger and older adults? The significance of this study lies in two aspects. This study is expected to show how different age groups employ this non-verbal communication tool, thus reducing intergenerational misunderstandings. Moreover, this study demonstrates a new approach and insights into CMC studies by following Yus’ (2021) Cyberpragmaics framework and applying Relevance Theory to analyze data.

Literature review

CMC, age, and emoji usage

The favorable attitudes of older adults toward Internet technologies show positive correlations with both their overall social and psychological well-being (Tsai et al., 2010; Zambianchi and Carelli, 2018). Fuss et al. (2019, 2022) found a positive association between high CMC use and social functioning and argued that CMC played a crucial role in sustaining support, potentially lessening social isolation among older adults by enabling them to remain connected with family and friends. These positive effects benefit from the current era in which older adults have the opportunity to engage in online interactions as CMC becomes prevalent. They can access more information, engage in intergenerational connections, and establish relationships with peers of similar age (Blit-Cohen and Litwin, 2004; Wright, 2000). CMC’s immediacy and asynchrony nature especially contribute to forming genuine human relationships within the virtual community, involving social bonds with others and supportive and companionship relationships (Kanayama, 2003).

The interest in examining interpersonal interaction and communication among older adults has been increasing in recent decades, and scholars have found that age is associated with the frequency and variety of emoji usage. However, findings of studies on the associations of age with emoji usage vary widely, given their distinct foci on specific platform software (Koch et al., 2022). For instance, Yu et al. (2018) focused on Facebook users. They examined the adoption of social network sites among older adults and found that they were involved in smaller and narrower Facebook networks than their younger counterparts. Still, they visited the site as frequently as the younger group. Koch et al. (2022) systematically examined age-linked language variations in WhatsApp messages and concluded that the younger group used emoticons and expressed emotions more frequently, but no age-related differences were observed in emoji usage compared to the older group. Both studies demonstrated the proactive online activity of older users.

However, some other studies showed that younger participants used emojis for a notably extended duration and with greater frequency, contributing to a heightened familiarity with emojis in their everyday communication (Danet and Herring, 2007; Liu et al., 2021; Weiß et al., 2020). For instance, Oleszkiewicz et al. (2017) examined the usage patterns of emojis in a subset of 86,702 individuals on Facebook, and their results showed that the frequency of emoji usage was negatively associated with age. Prada et al. (2018) discovered that younger individuals reported a higher frequency of emoji usage in their daily digital communication and expressed stronger motives for using emojis, such as facilitating the expression of emotions, enhancing message content, and softening the tone of a message. Their study also suggested that patterns of emoji usage demonstrated generational differences, and it was worth exploring how emojis could improve communication across generations. Maíz-Arévalo (2020) examined age differences in compliments performed by Spanish users on Facebook and found the younger group employed more multimodal messages (e.g., emojis).

Age is also combined with other factors influencing emoji usage, such as relationships and social status (Cui, 2022). Cavalheiro et al. (2023) conducted a correlational study and found that younger age was linked to more frequent emoji use with close contacts such as family and friends, while older age was associated with increased emoji use frequency with more distant interlocutors like supervisors and doctors. Liu et al. (2021) investigated the impact of age on Chinese requests in social media communication. They discovered that the younger group utilized emojis most frequently, whereas the older group completely avoided using them. However, the younger group refrained from using emojis when making requests to individuals of higher social status.

Age and emoji comprehension

Besides usage, emojis exhibit significant variability in their comprehension as distinct emotions, suggesting a degree of dependence on specific contexts as well (An et al., 2018; Brants et al., 2019; Kutsuzawa et al., 2022; Sun, 2021). For instance, older individuals tend to associate the classic smiley and frowny emojis with emotions such as joy and frustration, respectively, in contrast to younger individuals who link them more with contentment and sadness (Weiß et al., 2020). The variability in emoji comprehension is notable, particularly concerning valence, which refers to the emotional positivity or negativity associated with the conveyed emotion, indicating the degree of pleasantness or unpleasantness expressed by an emoji. For those emojis with the same valence as positivity or negativity, a difference exists in the perceived degree of emotion between older and younger groups. Kutsuzawa et al. (2022) conducted an online survey with a nine-point scale to investigate how the interpretation of facial emojis influenced the arousal-valence dimensions across diverse age groups. It was revealed that when presented with negative emojis, middle-aged people were more likely to interpret these symbols as expressing stronger or more intense emotions than their younger counterparts.

Regarding whether the emotional valence of an emoji matches or contradicts that of the accompanying text, Walther and D’Addario (2001) experimented to assess the impact of three frequently used emoticons on the comprehension of messages and found that verbal messages conveyed emotional information more effectively than emoticons, except when the emoticon conflicted with the positive emotional valence of the verbal expression, indicating that contradictory information held more significance than supportive information. Derks et al. (2008) and Boutet et al. (2021) also demonstrated that emoticons lacked the power to reverse the emotional valence of the written message. All three studies showed that text carries a higher expressive valence than emojis. Through two experiments, Riordan (2017) also concluded that even emojis representing objects could enhance the emotional impact of a message when combined with text, compared to a message containing only text, thereby contributing to the overall positive valence of a message.

When considering the influence of age on emoji valence, older individuals generally tended to be subjectively more positive than their younger counterparts and offer more favorable evaluations of them (Hsiao and Hsieh, 2014). But it remains a controversial issue. Weiß et al. (2020) investigated how age contributed to the specific processing of emotions represented by emojis. They found that such positivity bias pattern specific to certain age groups was only observed exclusively in smiley emojis, whereas other emojis became increasingly associated with negative emotions as age advanced.

Variability in the comprehension of emojis might lead to an ambiguous understanding of emotions, and sarcasm is one of the most susceptible ones to be influenced due to its implicit nature, which academia has delved into. Garcia et al. (2022) investigated the influence of the winking face emoji with an online rating task on both the comprehension and perception of message intent for sarcastic or literal criticism or praise. Results demonstrated that older adults were less proficient in comprehending and perceiving sarcastic intent than their younger counterparts. Their capacity to address sarcastic intent saw a notable improvement when a winking face emoji accompanied the messages. Their study further confirmed that emojis, able to serve as an indicator of sarcasm, made up for the lack of non-verbal cues in written communication and exerted an impact on satisfying intergenerational communication. The conclusion is consistent with Zhou et al.’s (2017) study, in which they found that smiling emoji was deemed as a genuine smile standing for happiness and hospitality for older adults, while younger generations assigned it a sarcastic meaning and seldom used it sarcastically when the younger ones communicated with family members.

Cui (2022) further investigated the differences between younger and older adults in making judgments about ambiguous statements accompanied by a smiling emoji and how age influenced the understanding of such statements. She found that for younger adults, the sender’s age showed a noteworthy correlation with how they perceived sarcasm in emoji-based ambiguous statements. In contrast, for older adults, the age of the sender had no impact on their comprehension of sarcasm in such statements. However, studies also exist that find no disparities in the comprehension of emoji meanings between older and younger individuals (Gallud et al., 2018).

Emoji usage and comprehension on WeChat in the Chinese context

The vast majority of language-oriented CMC studies have focused on the English language, partly due to the Internet’s origins in the United States. However, with the rapid spread of the Internet beginning in the mid-1990s, native language traditions in CMC started to emerge in other countries. Cross-linguistic studies have identified both similarities and cultural specificities in online language use. These studies have shown that the usage and comprehension of emojis have long been influenced, both consciously and unconsciously, by cultural differences (Liu et al., 2022), shaped by factors such as national (Gao and VanderLaan, 2020), ethical (Ji and Biaus, 2024), and regional (Wang, 2004) variations. Therefore, further studies are needed, particularly on pragmatic phenomena, including emoji usage in languages other than English (Herring et al., 2013).

Chinese players dominate their American counterparts in the realms of search, social media, and e-commerce within their domestic market (Statista, 2019). They have their specific way of using emojis in online communication. For instance, Yang and Liu (2020) explored the patterns and communicative functions of emojis on Weibo in their co-occurrence or co-presentation with Chinese text. They found that emojis co-occurred with texts to create a multimodal meaning. Their study suggested that emojis not only served to substitute, reinforce, or complement text but also functioned in performing speech acts, emphasizing subjective interpretations, and conveying higher levels of informality and/or casualness.

In the Chinese context, the specific characteristics of emoji usage and comprehension, as well as their cultural factors, have attracted considerable research attention. Li and Yang (2018) investigated the pragmatic functions of emoji usage on WeChat, finding that Chinese users tend to employ exaggerated and generalized emojis, distinguishing them from users in other countries. However, their study only focused on participants aged 20–40. Chinese users are more likely than Spanish users to use non-verbal cues, such as emojis, to convey negative emotions (Cheng, 2017). Chen et al. (2024) conducted a comparative study between participants from the UK and China to explore the cultural influence on emoji comprehension. They found that UK participants generally demonstrated greater accuracy in identifying emotions conveyed by emojis, except for the feeling of disgust. Several scholars have examined the reasons for the characteristics from the perspective of Chinese cultural specificities. Sun et al. (2023) highlighted the role of individualism and collectivism in shaping the usage and interpretation of emojis. Wang et al. (2019) explored how cultural context intersects with emojis usage, noting that property—particularly respect for social hierarchies and collectivist values influenced by Confucianism—played an essential role in impression management among participants.

Recently, emoji usage on WeChat has garnered increasing attention from scholars. Li and Yang (2018) concluded that emojis on WeChat were of high frequency, functionality, and efficiency in Internet-based communication. In terms of public life, Zhang et al. (2020) examined how emojis were utilized in comments responding to push notifications from the official WeChat account of Guokr. They argued that emojis played a significant part in integrating traditional social norms from everyday situations with the evolving standards of social media communication. This function extended beyond mere playful effects to preserve face and maintain social harmony. Considering non-Chinese users, Szurawitzki (2022) pointed out that the digital environment in China was highly penetrated by emojis and analyzed emoji usage and its functions in the context of German expatriates’ communication in China via WeChat. It was concluded that emoji usage was highly favored among German-speaking expatriates in their WeChat communications, with over 60% of them employing emojis frequently or more often.

It has been noticed that emoji usage and comprehension are closely related to age on WeChat. Liu et al. (2022) examined multi-dimensional factors influencing emoji usage and identified age as one of these factors through semi-structured interviews and questionnaires, focusing on WeChat users as research subjects. Occasionally, emojis might be wrongly sent in their usage and cause embarrassment. Liu et al. (2020) argued that users between the ages of 18 and 25, as well as those aged 26–30, were more prone to feeling embarrassed when they mistakenly sent emojis on WeChat compared to individuals aged 31–40. Age also exerts an influence on the comprehension of emojis. Chen et al. (2024) examined emoji comprehension of people of different ages on four commonly used platforms, including WeChat, and found notable impacts of age on the accuracy of surprised, fearful, sad, and angry emojis, indicating that as participants’ age increased, their accuracy decreased. However, age was found not to influence the comprehension of disgusted and happy emojis.

Studies on emoji usage in the Chinese context are necessary and significant as an essential part of composing CMC discourses. However, on the one hand, most previous studies paid attention to a specific emoji, such as a smile or wink face, when comparing their usage by different age groups instead of considering a complete range of emojis. On the other hand, they might investigate the usage of various emojis centering on a particular age group. Consequently, the conclusions regarding the rules for emoji usage among individuals of multiple ages lack comprehensiveness and systematic elaboration, particularly within the Chinese context.

In terms of the theoretical framework, many scholars have proposed various taxonomies of emoji functions. Among these taxonomies, conveying emotion is a common and significant function (e.g., Herring, 2017: 104; Al, 2018: 118; Ge and Herring, 2018; Sampietro, 2019: 110; Völkel et al., 2019). However, it was only regarded as a small part of the entire framework in these taxonomies and has not been analyzed with a focus. And some other function classifications didn’t even mention this significant function (e.g., Durante, 2016: 61–62; Herring and Dainas, 2018; Siever, 2020; Siever and Siever, 2020; Panckhurst and Frontini, 2020). However, emotional communication is an indispensable aspect of personal interactions and tends to be tricky and elusive, especially in online communication. It needs to be explored more deeply.

Additionally, most scholars have classified them from linguistic and semantic perspectives (e.g., Siever and Siever, 2020; Panckhurst and Frontini, 2020), while others, though adopting a pragmatic approach (e.g., Sampietro, 2019), have not focused on Relevance Theory. Yus (2001, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016, 2021) proposed Cyberpragmatics, which aimed to apply relevance-theoretic claims to the specific environment of Internet-mediated communication and analyzed exchanges in all forms of Internet-mediated communication. However, there are particular issues with his theoretical framework. Based on Yus’ (2021) framework, we propose five pragmatic functions of emojis (i.e., filling, enhancing, weakening, challenging, and substituting) to analyze the data more clearly. An effective approach to analyzing emoji usage is to explore the distinct cognitive processes underlying various uses, particularly through Yus’s relevance-theoretic model, Cyberpragmatics.

The usage of the WeChat emoji system by people of different ages has not been explicitly examined with a focus on emotional expression, particularly from a theoretical perspective such as Relevance Theory. Based on the previous studies, this study involves the entire emoji system to explore the distinction of emoji usage between younger and older individuals in terms of Relevance Theory. As the sole research of its kind, the study demonstrates that a cognitive structure such as Relevance Theory has the potential to shed light not just on how interpretations are made but also on how non-verbal language is used. Consequently, it can be employed to uncover new emoji usage patterns across different age groups that have not been explored before.

Relevance theory and related studies on CMC

According to Sperber and Wilson (1995: 55), “The kind of explicit communication that can be achieved by the use of language is not a typical but a limiting case.” Inferential processes are involved in verbal communication and coding processes and operate through producing and interpreting evidence. The inference of emotion as a non-propositional object is a particularly elusive issue (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). Emotion can be inferred and interpreted through stimulus in ostensive-inferential communication in which “the communicator produces a stimulus which makes it mutually manifest to the communicator and audience that the communicator intends, employing this stimulus, to make manifest or more manifest to the audience a set of assumptions (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 63)” and “the act of ostensive communication automatically communicates a presumption of relevance” (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 156). The principle of relevance refers to the fact that an act of ostension carries a guarantee of its optimal relevance.

Having some contextual effects in a context is a necessary condition for relevance. A stimulus is relevant to an individual to the extent that the contextual effects achieved when it is optimally processed are large, and the effort required to process it optimally is small (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 145). Sperber and Wilson (1995: 108, 117) described that “a deduction based on the union of new information P and old information C is a contextualization of P in C. Such a contextualization can only give rise to contextual effects in the form of an erasure of some assumptions from the context, a modification of the strength of some assumptions in the context, or the derivation of contextual implication”.

“Contextual effects are brought about by mental processes… which involve a certain effort and expenditure of energy (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 124)” and “central processing resources have to be allocated to the processing of information which is likely to bring about the greatest contribution to the mind’s general cognitive goals at the smallest processing cost (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 48).” The processing effort involved in achieving contextual effects is a negative factor to assess degrees of relevance: other things being equal, the greater the processing effort, the lower the relevance in contrast to the positive factor contextual effects of an assumption (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). The processing of stimuli is geared to the maximization of relevance to achieve a specific cognitive effect with the minimization of processing efforts.

How an emoji is processed cognitively, concerning processing efforts and contextual effects, can explain how it is used to perform a function. The integrated new framework further demonstrates that Relevance Theory can shed light on not just cognitive processes but also usage patterns, making it helpful in uncovering previously undiscovered trends of emoji use among different age groups. This study will explore how interlocutors can achieve maximum relevance with the minimization of mental efforts based on contextual effects in which emojis are involved in WeChat discourses from the perspective of Relevance Theory. Yus (2016) examined emoticons from a pragmatic, relevance-theoretic perspective about such issues as the extent to which emoticons led to the eventual relevance of the information communicated by the texts typed on the keyboard and how emojis helped to convey users’ feelings, attitudes, and emotions in a relatively nuanced way. He believed that emojis were input with anticipation of relevance, and receivers were compelled to engage in supplementary processing efforts to ascertain the affective or emotional connotation conveyed by the emoji and to discern its correlation with the concurrent verbal expressions. The additional efforts can be offset by extra cognitive effects.

Yus (2014) isolated eight functions of emojis based on previous classifications using a pragmatic, relevance-theoretic approach, as shown in Table 1, which was relatively comprehensive. He highlighted emojis’ role in promoting the eventual relevance of the texts they accompany. Compared with previous ones, this classification focused more on the relationship between emojis and texts instead of regarding emojis solely. Yus aimed to explore how emojis could contribute to (or at least try to lead to) a more accurate interpretation of the coded verbal message that followed/preceded them regarding underlying attitudes, feelings, and emotions. The criterion unified as the interpretation of verbal texts made this classification more comprehensive and organized.

Although covering most possible emojis’ functions involved in online conversations, Yus’ classification still can’t be considered flawless. First, some of the statements are abstract and elusive, and it is difficult to sort out data in practice, such as function (7) “to add a feeling of emotion towards the communicative act.” It expresses the sender’s emotion while editing information (Sun, 2021). Since the feelings of communication at every moment are ephemeral and affected by many other factors besides the contents of the utterance, this function may be hard to capture in concrete discourses.

Second, the distinction among certain items, rooted in differences between attitudes and emotions, is blurred. Function (6) differs from function (1), and function (8) differs from function (2) mainly based on whether emojis impact emotion or attitude. Although many scholars have distinguished emotion and attitude (Pilkington, 2000), a degree of intersection still exists between them. For instance, Cowie and Cornelius (2003) acknowledged that the distinction between terms denoting emotions and those referring to attitudes was challenging. Yus (2014) also highlighted that attitudes and emotions overlapped because attitudes entailed categorizing a stimulus along an evaluative dimension, and evaluation was regarded as a fundamental aspect of emotionality. Consequently, emoji usage is difficult to classify into these blurry function categories.

Finally, this framework underestimates those emojis appearing alone, which is a prominent phenomenon in WeChat discourses because it focuses on emojis following or preceding texts. Sun (2021) partly noticed this defect and introduced turn-taking and backchannel devices to the framework from Ikeda and Bysouth’s (2013) study. In general, even though Yus’ (2014) eight categories are extensive enough to cover most of the emojis’ function in CMC and notice the close relationship between emojis and texts from the perspective of Relevance Theory, function (7) is almost infeasible to judge in practice and the criterion of attitude/emotion is blurred. Besides, with emojis emerging alone taken into consideration, the modified framework presented by Sun (2021) becomes complicated and ununified.

Yus (2021: 83) further proposed his new pragmatic taxonomy of functions as “emoji within,” “emoji without,” and “emoji beyond descriptions” according to emojis’ contribution to the comprehension of the text they accompany. His new taxonomy encompasses a broader range of situations for emoji usage compared to the one he proposed in 2014, which included only eight functions. The new taxonomy comprises 17 functions and follows a more succinct categorization principle. It addresses the limitation of solely focusing on emojis with texts instead of emojis used independently. However, the new taxonomy still fails to address the first two issues concerning elusive standards such as feeling, emotion, or attitude towards communicative acts and the blurry boundary between emotion and attitude. Based on Yus’ (2021) framework, we propose our framework, which includes five pragmatic functions of emojis: filling, enhancing, weakening, challenging, and substituting. These will be elaborated on in the section “Analytical framework”.

The study

Participants and data source

This project aimed to collect natural conversations from WeChat in which emojis were used among 20 younger and 20 older users. These conversations had already occurred at the time of collection, with no influence from the study’s presence. Except for age, the other variables were controlled. First, all these 40 participants were at a similar level of intimacy—they were acquaintances but not quite close friends. Second, the two groups were at similar education levels—they all received tertiary education. Third, the two groups came from the northern part of China with similar geographical features. The descriptive statistics of participants are detailed in Table 2.

Participants in the younger group were students or university graduates, aged 25–30 at the time of the data collection, while those in the older group were more than 60. These two groups were selected as subjects: First, individuals aged 60 years and older in China are still active online, especially on WeChat, to maintain relationships with family and friends compared with older persons. Second, users in their twenties are a representative group in online communication owing to their lively characteristics. They pursue enjoyable and playful activities, but are mature enough to form their online behavioral style. With a relatively large age gap between the two groups, they exhibit diverse emoji usage habits, which are worth studying through comparison.

Although the sample size is relatively small, similar qualitative studies in comparable contexts have successfully used small-scale samples, leading to valuable insights (Sun, 2021; Li and Yang, 2018). These studies demonstrate that, particularly in exploratory research, a smaller sample from specific groups does not compromise the reliability of the findings and is sufficient to generate meaningful results. Moreover, current computer software tools cannot identify and analyze emojis. While the corpus should not be too small, it needs to be of a size that can be manually managed (Li and Yang, 2018). Furthermore, given the scarcity of participants and the study’s specific aims, adopting this sample size is both reasonable and feasible.

Procedure

A combination of purposive and snowball sampling methods was employed in this study, given the personal privacy of conversations on WeChat. First, an older adult and a younger one were recruited after asking for permission, marked as P1 and P2. P1 is a 60-year-old female teacher who has retired from a primary school, and P2 is also a female, 25 years old, who has just graduated from a university. Then, twenty WeChat friends of the younger individuals and twenty of the older adults who met the age criteria were selected to compose the older group and the younger group, respectively.

Conversations on WeChat of P1 and P2 with their twenty friends, spanning from October 2019 to October 2022, in which emojis were used, were collected. It was chosen for this period due to the convenience of data collection while ensuring a relatively complete data span over time. The 3-year duration minimizes the risk of bias from temporary phenomena, providing a more robust and generalizable dataset. It is seen as a conversation when it encompasses a coherent exchange of ideas, information, or perspectives between interlocutors in which they finish discussing an integrated event. Emojis, together with all texts in a piece of conversation, were taken into consideration. When all conversations based on such criteria were collected within a similar time duration, there were 171 conversations from younger users and 82 conversations from older users with similar intimacy levels over WeChat. Emojis, whether alone or used as clarifying text, were annotated and counted manually in these conversations according to the five pragmatic functions illustrated in the section “Analytical framework,” the analytical framework part. An annotator conducted the annotation process twice, with a 2-month interval in between. Intra-coding reliability testing was performed using SPSS software, resulting in a high Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.853, indicating a favorable level of consistency between the two annotation sessions.

In addition, textual elements were counted to calculate the ratio of emojis to textual elements, revealing the proportion of emojis used in conversations across different age groups. Textual elements included both the textual messages and the texts included in emojis themselves, as they serve a similar function in aiding comprehension and usage. The statistical results provide insights into the frequency and proportion of these functions. By comparing different functions used by older and younger groups on WeChat, we can explore how these functions are distributed differently among younger and older adults. Furthermore, four participants (two from the younger group and two from the older group) were selected for interviews to validate the hypothesized processing effort and contextual effect for each function within the framework outlined in Table 5 of the section “Analytical framework.” Since conducting interviews is time-consuming and labor-intensive, a smaller number of interviewees ensures both the quality of the interviews and the thoroughness of the analysis in this exploratory study. These four interviewees included the two individuals who recruited other participants. Before conducting the interviews, the four participants were provided with detailed explanations and examples of the five pragmatic functions of emojis, their usage, and the meanings of processing effort and contextual effect to ensure their comprehension. The interview results are presented in Appendix 1.

Pearson’s chi-square analysis was employed to examine the relationship between nominal variables through crosstabulation. Given that both age group and pragmatic function of emojis were treated as nominal variables, as will be described in the section “Analytical framework,” Chi-square analysis was chosen to assess their association, elucidating patterns and dependencies within the given nominal datasets. Initially, a null hypothesis was set: “There is complete independence, and no association, between the age groups and the pragmatic function of emoji usage.” Chi-squared test and age group*pragmatic function of emojis crosstabulation were made using software SPSS, as presented in Tables 3 and 4.

The Pearson Chi-square value was high, and the p value was less than 0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis was rejected and that significant differences existed regarding the pragmatic function of emojis used by the younger and older groups.

Analytical framework

This study applies Relevance Theory and reclassifies the pragmatic functions of emojis, grounded on the three forms of contextual effects (Sperber and Wilson, 1995), into five categories: filling, enhancing, weakening, challenging, and substituting. These five functions differ in processing efforts and contextual effects when emojis are used to achieve optimal relevance. Based on the functions’ definitions, characteristics, and usage mechanisms, “processing efforts” and “contextual effects” are hypothesized to be categorized into five levels according to their relative magnitude in a qualitative manner. This will be explained in detail after Table 5.

To distinguish this general concept of contextual effect from the specific one with hypothesized values proposed in the framework, we refer to the general concept in Relevance Theory as “contextual adjustment” in Table 5. The values of processing efforts and contextual effects in Table 5 represent relative levels among the five functions but do not carry any actual numerical significance. Larger numbers in the processing efforts and contextual effects columns indicate higher levels. For example, the number for the “challenging” function in the processing efforts column is the largest, signifying that it requires the most effort to process among the five functions. Similarly, the number for the “filling” function in the contextual effects column is the largest, indicating that it can produce the most effects. The rationale for the hypothesized ranking of processing efforts and contextual effects for the five functions is presented in the following section.

The congruency between the emoji and text is a critical factor in processing effort. When both the emoji and the text express the same emotional tone, whether positive or negative, the emoji enhances users’ ability to process information and better understand the intended meaning, requiring less mental effort to process (García-Carrión et al., 2024). Zhong et al. (2025) conducted a neural experiment and found that extra cognitive effort was needed to resolve the inconsistency when an emoji contradicted the sentence’s emotion. Based on the definition of the five functions shown in Table 5, four of them (“filling,” “enhancing,” “weakening,” and “challenging”) are involved in the direct combination of emoji and text. They can be regarded as a continuum, among which the “enhancing” function of emojis is a typically congruent case, while the “challenging” function is an incongruent one. They are at opposite ends of the continuum. The other two functions are positioned between the two ends of this continuum, with the incongruity of “weakening” greater than that of the “filling” function. Therefore, apart from the “substituting” function (in which emojis are used independently), the “enhancing” function requires the least processing effort among the four functions. In contrast, the “challenging” function involves the most processing effort. The “weakening” function requires more processing effort than the “filling” function, but both are less than “challenging” and greater than the “enhancing” function. The ranking of the four functions in processing effort should be enhancing < filling < weakening < challenging.

The “substituting” function refers to instances where emojis replace verbal elements in a message, aiding conversational management, such as turn-taking and backchannelling. Since the “substituting” function does not directly combine with text to convey information, typically taking on the role of text with minimal supporting text, the relevance between the emoji and text must be optimal to ensure effective communication. This is often achieved by designing emojis for ease of understanding, sometimes incorporating artistic fonts within the emoji itself to enhance comprehension. As a result, the “substituting” function is a unique case where the degree of incongruency in the context approaches zero, and the degree of congruency nears infinity. Thus, the processing effort required for the use of “substituting” emojis is minimal, as reflected by a value of 1 in Table 5.

Contextual effects are also influenced by the congruency between the emoji and text, but the influence is primarily reflected in the intensity. Several studies have found stronger emotional reactions in situations where the text and the emoji share the same emotional valence (Lohmann et al., 2017). Emotionally matching sentence-emoji pairs led to greater emotional activation compared to mismatched ones (typically “challenging” function) (Zhong et al., 2025). Therefore, when considering only the intensity of emotion emojis elicit, their contextual effects can be ranked in terms of the impact of the degree of congruency as follows: substituting > enhancing > filling > weakening > challenging.

However, according to Relevance Theory, the intensity of emotion is only involved in one type of contextual effect: “a modification of the strength of some assumptions.”; beyond this, two additional forms of contextual effect that emojis can produce are “the derivation of contextual implications” and “the erasure of certain assumptions from the context” (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 117), as is shown in the “contextual adjustments” column in Table 5. This study proposes an alternative ranking of functions according to contextual effect based on Relevance Theory (Sperber and Wilson, 1995): filling > substituting > enhancing > weakening > challenging, which takes into consideration all three diverse forms of contextual effect they are capable of generating in CMC communication. The reasons are as follows.

According to Relevance Theory, the three forms of contextual effect arise from the interaction between new and old information (Sperber and Wilson, 1995: 109). This theoretical premise provides a basis for understanding how the degree of constraint placed on new information varies depending on the nature of the contextual effect. Specifically, the new information (an emoji) is most constrained by the existing information (the accompanying text) in the case of “an erasure of some assumptions from the context”, as it is used and interpreted in a highly limited context to express irony and joking. Conversely, it is least constrained in the case of “a derivation of contextual implications,” where it is used and interpreted more flexibly and expansively since text places the least restriction on emoji usage. The degree of constraint in “a modification of the strength of some assumptions” lies between these two extremes.

As is shown in Table 5, the form “a derivation of contextual implications” includes the “filling” and “substituting” functions, in which the emoji usage is less constrained by text. Therefore, they can generate more specific contextual effects in flexible usage. The “filling” function involves adding emotional expression, which would be difficult to convey without the aid of the emoji, to the propositional content and communicative act. Since the accompanying text itself does not directly convey emotional information, emojis have the flexibility to express a wider range of emotions, unhindered by the limitations of the text. Moreover, the text aids in contextualizing the emojis, helping to clarify their meaning and fostering the generation of a more nuanced contextual effect.

However, emojis performing the “substituting” function fully take on the role of text with minimal verbal support, producing diverse contextual effects by innovatively replacing language to convey emotion and encouraging the audience to engage in meaning construction. The absence of accompanying texts limits this function’s flexibility to achieve comprehension compared to the “filling” function. Consequently, the contextual effect generated by the “substituting” function is slightly lower—rated at 4—while the “filling” function produces the most substantial contextual effect, with a value of 5, as shown in Table 5. By contrast, the “challenging” function falls under the case of “an erasure of some assumptions from the context,” which contradicts the explicit content of utterances and produces specific contextual effects, such as joking and irony. The value of the contextual effect for the “challenging” function is the lowest, with a value of 1.

The “enhancing” and “weakening” functions involve the “modification of the strength of some contextual assumptions,” thus placing them in the middle range in terms of contextual effect. Emojis perform an “enhancing” function in which emojis usually serve to amplify the emotional expression in text that already conveys an emotional tone. Compared to the “filling function, they are limited in the diversity of generated contextual effects, primarily yielding intensification and emotional modulation, as emojis must align with the textual meaning to enhance the intensity of emotion, thereby securing the congruency between the emoji and the text. However, they are more flexible than the “weakening” function, which has more limited contextual applicability, primarily appearing in sensitive contexts to soften the mood and mitigate illocutionary force. Thus, the “weakening” function gives rise to fewer types of contextual effects than the “enhancing” function.

The hypothesized levels of processing efforts and contextual effects for each function have been validated by the interview results of four participants in Appendix 1. They all provided consistent rankings regarding processing efforts and contextual effects of each function, aligning with those proposed in the framework. Emojis in Fig. 1 were used to perform the pragmatic function of “filling,” which could sometimes be difficult to distinguish from the “weakening” or “challenging” functions. The “weakening” function typically affects the illocutionary force of a speech act, especially in requests or commands, while the “challenging” function tends to contradict the explicit content of the text. In this example, neither the illocutionary force of a speech act nor the contradictory meaning between the text and emojis is involved. The interlocutors derived emotional contextual effects such as kindness, apology, and appreciation from the emojis, which were not revealed by the texts. This conversation took place between two university students when A should be on duty in the reading room but failed to enter without the key, so B planned to go to give it. Texts were accompanied by two types of emojis to convey information. As is shown in the above screenshot, no emotion of the interlocutors was expressed between the lines literally. But emojis, including  and

and  were interspersed in the communication process to endow emotional features to the monotonous words so the two parties could perceive the emotions of each other. Essentially, B was sorry for not giving the key to A in advance. However, A didn’t blame her, actually, and appreciated that B was willing to come to deliver the key.

were interspersed in the communication process to endow emotional features to the monotonous words so the two parties could perceive the emotions of each other. Essentially, B was sorry for not giving the key to A in advance. However, A didn’t blame her, actually, and appreciated that B was willing to come to deliver the key.

The conversation in Fig. 2 occurred during the spring festival in China, when it was a tradition for the Chinese to celebrate and bless each other. The emotion of blessings and celebration has been coded in the texts directly. In other words, they could already be perceived by receivers even without the attached emojis. But the senders still used repeated emojis, such as  and

and  to strengthen the emotion. That behavior demonstrated the emojis’ “enhancing” function in intensifying the festive feeling in this situation. With such emojis, a stronger emotion of blessing and celebration could be communicated.

to strengthen the emotion. That behavior demonstrated the emojis’ “enhancing” function in intensifying the festive feeling in this situation. With such emojis, a stronger emotion of blessing and celebration could be communicated.

In Fig. 3, the use of emojis serves to mitigate the illocutionary force of the speech act, which is inherently one of requirement or command. Emojis help align the emotional tone with a more cooperative or friendly approach, softening the tone of the message. By employing the emojis  and

and  , Speaker A can convey the necessity of completing the task (i.e., the weekly youth learning) while also signaling a less demanding or stern attitude. This reduces the potential for the message to be perceived as overly authoritative or forceful, which could be seen as a face-threatening act in a more formal or hierarchical context.

, Speaker A can convey the necessity of completing the task (i.e., the weekly youth learning) while also signaling a less demanding or stern attitude. This reduces the potential for the message to be perceived as overly authoritative or forceful, which could be seen as a face-threatening act in a more formal or hierarchical context.

Figure 4 is the only example of the emojis’ pragmatic function of “challenging.” To perform this function, they are likely to be used to express emotions concerning irony and joking. Senders usually use emojis of this kind to express satirical emotion and make the receivers aware of it. Sometimes, they are used to contradict the explicit content of the verbal utterance. The complex inference process determines its large efforts to comprehend. In this case, A was explaining to B that she couldn’t see the movie with B as planned. A said “OK” verbally, absolutely a happy consent, but then added an emoji  that expressed the contrary meaning. In addition to gladly looking forward to meeting next time, A also showed depressed emotion owing to failing to meet this time. The emoji worked to erase the purely glad emotional context, allowing the conveyed emotion of the sender to become richer and more complicated.

that expressed the contrary meaning. In addition to gladly looking forward to meeting next time, A also showed depressed emotion owing to failing to meet this time. The emoji worked to erase the purely glad emotional context, allowing the conveyed emotion of the sender to become richer and more complicated.

The closing emoji was a cartoonish egg saying “OK” with a big smile in Fig. 5, which performed the “substituting” function. They could communicate complete messages on their own without relying on accompanying texts. Embracing textual information itself, the lively emoji derived the contextual effects of a relaxing and pleasant agreement response and expressed the sender’s emotion to gladly know B was coming right down, which was not explicitly related to the emotion involved in the previous conversation. It was designed effectively through the cooperation between pictures and words, requiring minimal effort to understand.

Research results

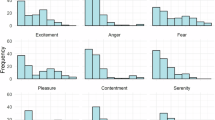

The above analytical framework in Table 5 was systematically applied to the collected data to annotate the functions emojis perform. Reorganizing “age group * pragmatic function of emojis crosstabulation” from Table 4, Table 6 presents the statistical results regarding frequency, proportion patterns of the five functions, and ratio of emojis/textual elements, demonstrating their distribution among younger and older adults as outlined in the research questions. Figure 6 is a comparative bar chart illustrating the proportion of emoji usage for different functions by younger and older age groups, providing a visual representation of preferences for emoji functions across users of different ages.

As seen from Table 6 and Fig. 6, emoji usage is similar between younger and older individuals in three aspects. First, the “challenging” function is the least frequent among the five functions, with “weakening” being the second least frequent, in conversations for the younger and older groups. Notably, the data of older users includes the occurrence of the number 0 in the “challenging” function. Second, the “substituting” function occupies a large proportion among both groups at 33.28% and 41.41%, respectively. Third, the ratio of emojis to textual elements shows little variation, with the number slightly higher in the older group than their younger counterparts. The ratio of emojis to textual elements in the younger group is 4.42%, while in the older group, it is 5.99%.

Salient differences in emoji usage exist between the younger and the older groups. First, there is a notable difference in the total number of conversations that include emojis. Within approximately the same period, 171 conversations, including 625 emoji usages, were identified among younger users, while only 82 conversations involving 256 emoji usages were found among older users on WeChat. Second, the pragmatic function of “filling” accounts for the most significant proportion, as 43.36%, among younger adults, while for older individuals, it is only intermediate in frequency, accounting for ~16.1%. Third, the “enhancing” function percentage among the younger group is 15.68%, obviously lower than the previous two functions, but still a significant part. For the older group, the “enhancing” function accounts for the second largest proportion, 39.84%, indicating that older individuals are more willing to convey emotions already involved in literal content with emojis than their younger counterparts. Fourth, “substituting” is the most frequent pragmatic function for older persons, accounting for 41.41%, but serves as the second most common one for younger individuals. That means older users are more willing to use emojis to perform this function than younger users.

Regarding the interview results drawn from Appendix 1, all the interviewees ranked the five pragmatic functions consistently, whether according to the levels of processing effort required or contextual effects. They ranked processing efforts as challenging > weakening > filling > enhancing > substituting, and contextual effects as filling > substituting > enhancing > weakening > challenging. Both also align with the previously hypothesized rankings in Table 5. When it comes to the subjective questions, first, both older and younger adults believed that younger individuals communicated more on WeChat and generally used more flexible and varied emojis than older adults, because younger adults were more proficient with digital devices and wanted to employ emojis in a more creative way than older adults. Second, older adults believed that they used “weakening” and “challenging” functions less frequently than the other three because these two functions required significant processing efforts and easily led to misunderstandings due to the complex emotions involved. Younger individuals attributed this phenomenon to the degree of intimacy in the relationship between interlocutors. Because they were not very close friends, they rarely made demands of the interlocutor or expressed complex emotions, such as joking and irony.

Discussion

Emojis can be classified into three types based on their roles in communication: expressive emojis, interactive emojis, and symbolic emojis. Expressive emojis are primarily used to convey emotional expressions directly, such as smiling faces. Interactive emojis facilitate conversation engagement and interaction, expressing approval, disapproval, or encouragement, as seen in the thumbs-up emoji. Symbolic emojis represent tangible objects or abstract concepts, often symbolizing real-world entities, like a flower or a brain emoji. However, these categories are not always clearly distinct. For instance, interactive and symbolic emojis can also convey emotional information. We believe that all emojis can convey emotion regardless of specific types. And most emojis in our database are expressive emojis, which directly convey emotion. The emotional communication functions of emojis are the focus of this study.

In response to the research questions, our findings are as follows: First, both the younger and older groups used the “substituting” function a lot but seldom used “challenging” and “weakening” functions; second, the younger individuals were more likely to use the “filling” function whereas the older adults tended to employ the “enhancing” function. This section discusses the specific characteristics of emojis used by younger and older adults to convey emotion from the perspective of Relevance Theory. In general, the younger and older groups differ in their use of emojis to achieve optimal relevance. Older adults employ specific communication strategies to minimize effort: they use a smaller variety of emojis; in the “substituting” function, they tend to favor straightforward emojis that convey meaning more directly, rather than more cartoonish ones; they more frequently use the “enhancing” emojis over “filling” emojis, as the “enhancing” emojis require less cognitive effort; and the use of “challenging” emojis is absent, as they are the most effort-demanding. However, younger individuals tend to maximize contextual effects owing to their dynamic and lively characteristics, caring less about efforts. Furthermore, the usage patterns of older and younger participants are likely influenced by cultural factors, especially Confucianism.

Similarities

Although the total number of conversations that included emojis within the same period differed, the ratio of emojis to textual elements among the older and younger groups exhibited minimal difference. It indicates little variation in the general ratio of emoji usage to textual elements among groups of different ages. The results contradict previous studies that found that younger users used emojis more frequently than texts (Danet and Herring, 2007; Huang, 2022; Maíz-Arévalo, 2020; Weiß et al., 2020). However, several other studies demonstrated at least as active a role of older users as their younger counterparts in online communication (Koch et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2018). We found that users of different ages only differed in the diversity of emoji categories they used and their preference for employing emojis to perform various functions, rather than in the ratio of emojis to texts. It implies that emojis are becoming a standardized tool for emotional expression, transcending age-related differences in usage frequency as digital literacy rises across generations. More older adults engage with digital technologies and have developed a more intuitive understanding of how emojis can convey emotions, similar to their younger counterparts.

The pragmatic function of “substituting” plays a significant role in a large proportion of younger and older users’ conversations. And it was even the most frequently used function among older users. According to Relevance Theory, the relevance of a stimulus to an individual is determined by the extent to which the contextual effects, when optimally processed, are significant, and the effort required for optimal processing is minimal. As illustrated in the section “Analytical framework,” the analytical framework, the “substituting” function of emojis can achieve a high contextual effect (value 4) with minimal processing efforts (value 1) to express emotions with significant relevance. Therefore, it is the most popular type among both younger and older groups.

The “challenging” and “weakening” functions were much less frequent for both the younger and the older groups. These two functions require the most processing efforts (value 4 and value 5, respectively) of interlocutors to accomplish considerable relevance among the five functions, owing to relatively complex inference in emotional communication. The contextual effects they can produce are also limited to irony and softening mood (value 2 and value 1, respectively). In addition to the disproportionate effort for the minimal effect of both functions, the low frequency of their usage might be attributed to the intimacy degree of participants, since the relationship between interlocutors also plays a significant role in emoji usage (Cui, 2022). This factor is also verified by the interview results shown in Appendix 1, where participants report they tended to directly express their information rather than spend time hiding their real ideas because they were acquaintances but not close friends. Potentially, due to the low intimacy, they strived to maintain politeness and catered to each other, aiming to avoid increasing the cognitive load on the counterpart. This supports the idea that Chinese individuals, influenced by traditional cultures such as Confucianism, place greater emphasis on group harmony than those from individualistic cultures, where the focus is typically on individual identity (Nisbett and Masuda, 2003). The phenomenon is more pronounced among acquaintances than among close friends. They seldom employed sarcasm, irony, and banter concerning the “challenging” function, and they rarely imposed requirements involved in the “weakening” function.

Differences

Based on the statistical results, a comparison concerning emoji usage between younger and older users can be made. First, the total number of conversations that included emojis differed significantly between 20 younger and 20 older users during the same period. Conversations of younger users were twice as many as those of older individuals. The findings demonstrated that younger adults generally communicate more on WeChat. In terms of the general emoji category, emoji functions were distributed more evenly among younger individuals, while they were more concentrated among older users, according to the distributions of functions’ proportions shown in Table 6 and Fig. 6. The findings also indicated that the younger users in China overrode the older adults in variety when using emojis. Digital literacy and image management may help explain why the younger group engages in more online communication and uses a broader range of emoji categories.

The cognitive effort required to process emojis in social interactions is influenced by users’ digital literacy, which refers to an individual’s ability, attitude, and awareness of effectively using digital devices and resources for communication and meaningful social interaction (Martin, 2006). Users’ experiences with digital technologies largely depend on their level of digital literacy (Pool, 1997), directly influencing their willingness to use emojis in the future. Digital literacy is closely related to both the possibility and proficiency of technology implementation. The results demonstrate that, although digital literacy is increasing across generations, younger people, in contrast to older individuals, are still more adept at using a wider range of emojis and controlling them. This proficiency may spark greater interest and enthusiasm for multimodal expression (Maíz-Arévalo, 2020), which, in turn, further enhances proficiency.

It is confirmed by the interviewees’ report in Appendix 1 that, compared with younger individuals, older adults in China report being less proficient with the WeChat interface and its operating principle. It perhaps can be attributed to the fact that, unlike the older generation, the younger generation has grown up in an era where the virtual world has progressively emerged. Older adults tend to start using WeChat later, whereas younger individuals are introduced to it earlier, when their learning abilities are generally stronger. This early exposure allows younger individuals to adapt more quickly to it. In contrast, older adults may face challenges due to declining working memory capacity and processing speed as part of aging. These declines can impact their discourse processing abilities, even though their semantic knowledge remains intact (Kemper, 1992). It requires more processing effort for the older group to master the usage rules of a wider variety of emojis. Therefore, they use limited emoji functions to save effort, as mastering and employing more extensive emoji functions means expending larger processing efforts.

The image expectations for various age groups are different in Chinese culture. Visual elements, such as emojis, can serve as crucial tools for impression management on social media, as they reflect both the appearance and manner of individuals (Wang et al., 2019). In Chinese culture and modern society, people passing 35 are regarded as “middle-aged,” and over 50 are viewed as “old.” Such expressions are common in the news media as “this old woman at the age of 50.” Consequently, they may feel “old” and “inferior” psychologically and think they need more processing efforts to master the various emoji categories and achieve equal relevance to their younger counterparts. In addition, in Chinese traditional culture, old age means respectable, experienced, calm, and seriousness. The older group typically aims to present a stable, authoritative, and dependable image in response to social expectations, while the younger group tends to emphasize their dynamic and adaptable qualities (Huang, 2022). Therefore, the older group tends to use only certain emojis that align with their cultural image, avoiding those that might conflict with it.

Second, even though the “substituting” function played a significant role among both younger and older users in their conversations, the specific ways of its operation differed slightly between different age groups. They can be regarded as distinct communication norms that both groups have developed when interacting with their internal members. As shown by the last emoji in Fig. 7 and all three in Fig. 8, the “substituting” function used by the younger primarily performed as a social etiquette marker to close a conversation, while by older users to extend greetings. In addition, it was found that emojis performing the “substituting” function used by the older generation were more intuitive and straightforward, tending to include textual information themselves. In contrast, those used by younger persons were more indirect and abstract, usually cartoonish.

The different usage habits also serve as a communication strategy for various age groups to balance processing effort and contextual effects to choose the most suitable approach. Some emojis convey the content directly, while others appeal to the imagination and sensitivity (Majkowska et al., 2022), requiring more processing efforts. The older adults aimed to achieve the greatest relevance and cognitive effects by expending the least processing efforts. At the same time, the younger individuals endeavored to accomplish this by generating the most significant contextual effects. Intuitive and straightforward emojis performing the “substituting” function are easily employed and understood by older adults with minimal processing efforts, through which they can achieve the greatest relevance in showing the mutual manifestness of co-presence among synchronously inter-connected interlocutors in the conversation (Yus, 2016) without extra word-typing. However, younger people were more inclined to deviate from special contextual effects by emojis at the expense of processing efforts. Even after concluding a text-based discussion in this study, they tended to end the conversation with an additional emoji. This way of communication contributed to reducing stilted texts, creating a livelier and more interesting context, and making the communication funnier in the end. Potentially, this communication norm may be related to traits such as humility and caution, which are more pronounced in younger individuals than their older counterparts. The person who gives the final reply is considered more polite. This behavior requires more processing efforts than those without the use of any emoji, but it can produce special cognitive effects. For instance, in Fig. 7, the last emoji of a cute cat holding a red heart generated contextual effects of finishing the conversation politely and harmoniously.

Third, emojis’ “filling” function in conveying emotion made up a considerable proportion of conversations among younger users. However, the “enhancing” function was more popular among older users. Although emojis are attached to sentences explicitly in both “filling” and “enhancing” functions, the degree of their relevance and the processing efforts to deal with them differ a lot. Emotions represented by emojis in the “enhancing” function are already revealed by the textual content. Through repeated expression, interlocutors can understand emotional information and achieve large relevance with less processing effort. In addition to processing efforts, a higher percentage of younger respondents (61%) reported being “very confident” in understanding the intended meaning of emojis on social media, compared to only 44% of older respondents (Herring and Dainas, 2020). The lack of confidence in understanding emojis leads the older group to rely more on the conventional way of text, with emojis serving only an auxiliary role in performing the “enhancing” function rather than the “filling” function.

Fourth, the number of “challenging” emoji functions in emotional communication among the older group was notably 0. The “challenging” function tends to appear when the addresser endeavors to be less than fully explicit and gets addressees to infer what is meant to achieve specific effects, such as humor and politeness with relevant emojis (Forceville, 2022). Those special contextual effects are generated at the expense of significant extra processing efforts. Older people were more willing to use direct social communication, perhaps to communicate efficiently and save efforts, than their younger counterparts in online social interaction. This may explain why the older group’s “challenging” function usage was particularly low, amounting to 0. Since older adults tend to favor formal language styles (Ghazanfar et al., 2024), they emphasize clear-cut and straightforward communication, particularly related to emotions and relationships.

Conclusion

This study investigated how communicators of various ages in WeChat conversations employed emojis to achieve specific goals by balancing the impact of contextual effects and processing efforts through the lens of Relevance Theory. Among the five functions, the “substituting” function of emojis is popular among both older and younger adults. However, older users prefer to save processing efforts, while younger users prefer to create interesting contextual effects through this function. “Weakening” and “challenging” are the least used functions by both groups due to the large efforts to process them. Both “filling” and “enhancing” entail explicit texts accompanied by emojis to convey emotions, but “enhancing” can repeat emotional information that texts have already revealed. Consequently, it requires fewer processing efforts and becomes more attractive for older adults than younger users. The conclusion can be drawn from this study that the younger individuals in China communicate more on WeChat than their older counterparts. Older adults employ emojis in WeChat mainly for the purpose of saving processing efforts and caring less about contextual effects, while younger individuals tend to produce special contextual effects even at the expense of increasing their efforts.

The usage of the WeChat emoji system across different age groups has not been comprehensively explored, especially from a theoretical standpoint like Relevance Theory. To sum up, this study delved into the intricate patterns of emoji usage in WeChat conversations across different age groups, examining how communicators strategically employed these visual elements to attain specific communicative goals. Drawing upon Relevance Theory, it elucidated the interplay between contextual effects and cognitive processing efforts in emoji utilization by analyzing data collected from the younger and older groups, aiming to broaden the theory’s application scope and enhance communication effectiveness through emojis in CMC interactions. The study demonstrated that a cognitive framework like Relevance Theory could shed light on interpretive processes and usage, thereby aiding in identifying previously unexplored communication patterns across different age groups.

However, this study is far from flawless. First, in terms of participants, the established corpus comprised merely 253 conversations from 40 participants, and only four of them participated in the interview, reflecting a relatively small and confined sample size. Future research endeavors are recommended to augment the sample and interview size, thereby enhancing the representativeness of the results across both groups. Participants were recruited through the personal connections of two individuals, one younger and one older. Given that these two participants were consistently involved in the message exchanges, the study may be confined within a limited social circle, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Future research could address this limitation by recruiting more diverse social network participants to ensure the findings are more widely applicable. Formal training of participants before the interview would be highly beneficial to the rigor of our study. Additionally, most of the participants were female, which probably influenced the study’s results. Gender factors are to be considered in future studies.

Second, while this study focuses primarily on the emotional expressive function of emojis, interactive and representational/symbolic emojis also play a significant role in communication. These absent types of emojis may limit the scope of our analysis. Other roles of emojis, apart from emotional communication, such as conveying interpersonal and illocutionary force, were underemphasized. Future research could explore these types and roles of emojis in greater depth, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how different emoji categories contribute to communication.

Third, the qualitative assumptions underlying the values assigned to processing effort and contextual effect contribute to the subjective nature of the framework. This subjectivity may impact the generalizability of the findings. Future research could aim to explore these values through more objective measures, which may provide further insights into their robustness and applicability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Al RF (2018) Functions of emojis in WhatsApp interaction among Omanis. Discourse, Context Media 26:117–126

An J, Li T, Teng Y, Zhang P (2018) Factors influencing emoji usage in smartphone mediated communications. In: Chowdhury G, McLeod J, Gillet V, Willett P (eds) Transforming digital worlds. Springer International Publishing, New York, p 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78105-1_46

Blit-Cohen E, Litwin H (2004) Elder participation in cyberspace: a qualitative analysis of Israeli retirees. J Aging Stud 18(4):385–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.06.007

Boutet I, LeBlanc M, Chamberland JA, Collin CA (2021) Emojis influence emotional communication, social attributions, and information processing. Comput Hum Behav 119:106722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106722

Brants W, Sharif B, Serebrenik A (2019) Assessing the meaning of emojis for emotional awareness—a pilot study. In: Liu L, White R (eds) WWW’19: companion proceedings of the 2019 World Wide Web conference. WWW’19: The Web Conference, San Francisco, 13–17 May 2019. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, p 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1145/3308560.3316550