Abstract

Ambivalent sexism, which includes both hostile and benevolent sexism, exerts a substantial influence on the trajectory of women’s careers. In this research, we conducted two quasi-experimental studies (Study 1 and Study 2) and one large-scale survey study (Study 3) to investigate the dual impact of ambivalent sexism held by female candidates and male interviewers on women’s job interview outcomes. The data were collected in China, with Studies 1 and 2 involving undergraduate students as participants and Study 3 focusing on employed professionals. As predicted, Study 1 (n = 80) and Study 2 (n = 80) demonstrated that both hostile and benevolent sexism among female candidates and male interviewers negatively impacted the evaluation of women’s employment probability. Study 3 further revealed that this negative effect was mediated by the underestimation of women’s competence. Besides, the findings of three studies indicated that when benevolent sexism levels are high, the negative impact of hostile sexism on the evaluation of female candidates’ competence and their employment probability is significantly intensified. Based on these findings, we suggest that more social attention should be paid to gender bias, and female job seekers should develop more reasonable self-perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

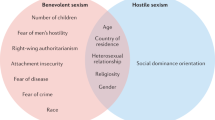

There are gender differences between men and women in human society. Indeed, the physiological differences between men and women are determined by heredity and evolution (Alexander and Borgia, 1979), and we cannot deny the existence of these differences. However, sexism is an artificial factor contributing to inequality (Allport, 1954). It refers to biased and erroneous opinions about sex roles and relationships, or unfair views and attitudes toward the other sex, arising from perceived gender differences (Brandt, 2011). Since the 1950s, sexism has garnered significant attention from scholars in the field of social psychology. In this period, it is generally believed that sexism manifests as a hostile attitude toward women (e.g., Swim et al., 1995). Subsequently, as the understanding of sexism has deepened, scholars have developed the concept of ambivalent sexism and suggested that sexism includes both hostile sexism (HS) and benevolent sexism (BS; Glick and Fiske, 1996, 2001).

According to ambivalent sexism theory (AST; Glick and Fiske, 1996), HS is a more aggressive belief system that portrays women as deceitful and manipulative, attempting to use sexual allure or false claims of discrimination to gain power and control over men. In contrast, BS refers to a seemingly positive yet paternalistic ideology that views women as virtuous and warm, and thus considers them deserving of protection and adoration by men (Glick et al., 1997; Hopkins-Doyle et al., 2019). HS, due to its overtly discriminatory nature, is readily recognized as sexism and is likely to elicit anger and increase motivation to perform. On the other hand, BS, which is more subtle and seemingly positive while implicitly suggesting women’s lack of capabilities, may not be perceived as sexism and is less likely to elicit the same level of motivation to perform (Dardenne et al., 2007). Research suggests that this warm, affectionate facet of sexism makes women more accepting of their status and treatment, thereby diminishing their drive to enhance their social and economic positions (Bollier et al., 2007; Connelly and Heesacker, 2012; Glick and Fiske, 2001; Hammond and Sibley, 2011). Recently, a growing number of studies have begun to focus on ambivalent sexism in the occupational field (e.g., Eagly and Mladinic, 2016; Erin et al., 2017; Rubin et al., 2019; Warren et al., 2020). Many empirical studies have shown that ambivalent sexism can deprive women of opportunities for their development, inhibit their developmental potential, and affect the formation of their career ambitions and creativity (Bareket and Fiske, 2023; Dardenne et al., 2007).

Previous studies have demonstrated the negative impact of ambivalent gender biases on women’s career development (e.g., Barron et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2020; Chawla and Gabriel, 2024). However, it remains unclear how ambivalent sexism held by female candidates and male interviewers, respectively, influences the job application process for women, the mechanisms through which these influences occur, and the interactive effects between hostile and benevolent sexism. What’s more, despite significant progress in understanding gender bias in various cultural contexts (e.g., Eagly and Mladinic, 2016; Fleming et al., 2020; Moscatelli et al., 2020), there remains a gap in the literature regarding the combined effects of benevolent and hostile sexism on women’s career advancement, especially within the unique social and cultural environment of China.

The present research was conducted to address these issues. Specifically, this research was conducted in China, where traditional gender roles and workplace dynamics present unique challenges for women’s career advancement. We investigate the impact of ambivalent sexism held by female candidates and male interviewers on the likelihood of women being selected for leadership positions. It also examines the mediating role of perceptions of women’s competence, as well as the interactive effects between hostile and benevolent sexism in this process.

Women’s ambivalent sexism and their cognition about themselves

A substantial body of research has documented various subtle yet significant barriers that affect women’s chances of being hired and attaining high-status positions (Bourabain, 2021; Moscatelli et al., 2020; Watkins et al., 2006). Much of this research highlights the central role of gender stereotypes, which portray men as more competent, while women are viewed as warmer and better suited for care activities or domestic roles (Glick et al., 1988; Mccreary et al., 1998; Rose and Rudolph, 2006). Consequently, there is a perceived mismatch between the requirements of specific organizational roles—emphasizing traits like assertiveness, competitiveness, and ambition—and the attributes typically ascribed to women, reducing their likelihood of being hired compared to men (Barron et al., 2024). Notably, men are often perceived as more competent and hirable than women, even when both genders exhibit similar performance or qualifications (Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2023).

In a sexist environment, women’s self-confidence is heavily influenced by societal stereotypes, leading them to doubt their competence for challenging tasks (de Sousa Santos et al., 2020; Fleming et al., 2020). The negative self-perceptions of women regarding their development potential, their self-efficacy, and their intentions are key factors in the gender differences observed in women’s career ambitions (Bareket and Fiske, 2023). As a result, these HS toward themselves contribute to their lower participation in competitive activities. When competing with men for the same jobs, women may underestimate their abilities and believe they are not qualified for positions that are perceived as more suitable for men. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1a: Female candidates’ hostile sexism has a significant negative impact on their evaluations of employment probability, specifically, the higher the level of hostile sexism among female candidates, the lower their evaluations of their own employment probability.

H1b: The evaluation of women’s competence plays a mediating role in the relationship between female candidates’ hostile sexism and their evaluations of their own employment probability.

On the other hand, women who hold strong BS values believe that they should adhere to the traditional gender division of labor. They insist that men should act as providers and protectors, while women should rely on men to maintain their economic and social status (Glick and Fiske, 2010). BS affirms the interdependence between men and women, but it promotes the institutionalization of the gender division of labor in a seemingly benign form (Moya et al., 2007; Napier et al., 2010). This subtle form of sexism causes women to forego the opportunity to compete fairly with men, thereby reinforcing societal concepts of gender hierarchy (Chawla and Gabriel, 2024). Specifically, BS emphasizes women’s warmth, selflessness, and dependency, which reinforces the role of men as protectors and providers, placing women at a disadvantage in career development and personal achievement.

In an environment permeated by stereotypes, women may develop a sense of learned helplessness. Over time, they internalize the belief that they have little control over their outcomes, leading to a lack of self-confidence and a tendency to underestimate their abilities (Hopkins-Doyle et al., 2019). In the job-seeking process, this can manifest as a lack of confidence in their competence and a reduced expectation of employment success. Consequently, women who internalize benevolent sexist beliefs may be less likely to pursue competitive positions or negotiate for better terms, further perpetuating the gender gap in the workforce. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H2a: Female candidates’ benevolent sexism has a significant negative impact on their evaluations of employment probability, specifically, the higher the level of benevolent sexism among female candidates, the lower their evaluations of their own employment probability.

H2b: The evaluation of women’s competence plays a mediating role in the relationship between female candidates’ benevolent sexism and their evaluations of their own employment probability.

According to the risk-enhancement model, when two risk factors exist simultaneously, one risk factor can enhance the influence of another (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005). This model suggests that the presence of multiple risk factors can create a synergistic effect, leading to more severe outcomes. In the context of job interviews, HS is a significant risk factor that can negatively impact women’s perceptions and experiences. The presence of BS further compounds this risk by influencing women’s self-perceptions and responses to unfair treatment.

More specifically, hostile sexism can lead to biased evaluations and reduced opportunities for female candidates, and the presence of benevolent sexism can exacerbate these effects. Benevolent sexism, while seemingly positive, reinforces traditional gender roles and can make women more likely to accept and internalize negative stereotypes. Studies have shown that women who have a high level of benevolent sexism are more likely to tolerate unfair treatment in the workplace (Moya et al., 2007). This acceptance of benevolent sexism can diminish their self-esteem and confidence, making them more susceptible to the negative impacts of hostile sexism (Chawla and Gabriel, 2024; Moscatelli et al., 2020). Therefore, the interaction between HS and BS will exacerbate female candidates’ cognitive bias of their competence and employment probability. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H3: Female candidates’ benevolent sexism plays a moderating role in the (a) direct and (b) indirect influences of their hostile sexism on their evaluations of their own employment probability, such that the direct and indirect effects are stronger among those with higher benevolent sexism than among those with lower benevolent sexism.

Interviewers’ ambivalent sexism and their cognition of females

In addition to the sexism held by female candidates themselves, the sexism possessed by interviewers also has a significant impact on women’s career development. Research by Eagly and Karau (2002) highlights a notable negative correlation between HS and the approval of women in managerial positions. Their study indicates that individuals with high levels of HS tend to hold less favorable views toward women as leaders compared to those with low HS. Further exploration by Masser and Abrams (2004) into the glass ceiling effect in management revealed a significant positive correlation between HS and negative evaluations of women. In contrast, there is a significant positive correlation between HS and the positive evaluation of men. Erin et al. (2017) found that leaders who adhere to HS values generally believe that female interns are less competent than male interns.

Recent research extended this line of inquiry. For example, Erin et al. (2017) found that leaders who endorse HS values are more inclined to believe that female interns are less competent compared to their male counterparts. This disparity in perceived competence can have far-reaching implications for career advancement, as it may lead to fewer opportunities for professional growth and development for women. Relevantly, study of Moscatelli et al. (2020) suggested that women are evaluated against multiple criteria and might therefore be asked to meet more requirements than men to be selected and make a career. Given these empirical findings, it is reasonable to infer that during the hiring process, interviewers with high levels of HS are more prone to underestimate the competence of female candidates and are less inclined to offer them positions. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H4a: Male interviewers’ hostile sexism toward female candidates has a significant negative impact on their evaluations of the female candidates’ employment probability, specifically, the higher the level of hostile sexism among male interviewers, the lower their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability.

H4b: The evaluation of women’s competence plays a mediating role in the relationship between male interviewers’ hostile sexism and their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability.

In addition to HS, BS also often imposes restrictions on women during the recruitment process. For example, noted that men tend to categorize women into positive or negative types based on their adherence to traditional roles. Research has consistently shown that BS is associated with positive evaluations of women who conform to traditional gender roles (e.g., Becker et al., 2011; Masser and Abrams, 2004). This association reinforces gender-based restrictions on women (Gutierrez and Leaper, 2024).

Despite its seemingly positive tone, BS acts as an invisible constraint on women (Dardenne et al., 2007). Specifically, positive evaluations of women who conform to traditional roles can create a double bind for female candidates. That means, if a woman does not fit the traditional stereotype, she may be seen as less competent or less likable. Conversely, if she does conform, she may be viewed as less ambitious or less capable of handling challenging roles (Cheng et al., 2020). This can lead to a situation where female candidates are evaluated more harshly or held to different standards than their male counterparts. Therefore, we can infer that BS also has an important influence on the interviewers’ cognition of female candidates’ competence and employment probability during the interview process. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H5a: Male interviewers’ benevolent sexism toward female candidates has a significant negative impact on their evaluations of the female candidates’ employment probability, specifically, the higher the level of benevolent sexism among male interviewers, the lower their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability.

H5b: The evaluation of women’s competence plays a mediating role in the relationship between male interviewers’ benevolent sexism and their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability.

The combined of HS and BS can significantly affect hiring decisions. By reinforcing the idea that women are either threatening (HS) or in need of protection (BS), these biases create a cycle where women are systematically excluded from leadership and decision-making roles. This exclusion further cements the status quo and makes it harder for women to break through the barriers that limit their career advancement (Becker et al., 2011). The interaction between HS and BS creates a multifaceted and pervasive influence on the evaluation of female job candidates. While HS directly undermines women’s competence and suitability for leadership, BS indirectly achieves the same effect by reinforcing traditional gender roles and creating subtle but significant barriers. This dual bias can lead to a consistent underestimation of female candidates’ capabilities and a reduced likelihood of their being hired. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H6: Male interviewers’ benevolent sexism plays a moderating role in the (a) direct and (b) indirect influences of their hostile sexism on their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability, such that the direct and indirect effects are stronger among those with higher benevolent sexism than among those with lower benevolent sexism.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 is to investigate the direct effects of female candidates’ HS and BS on their evaluations of their own employment probability, as well as the moderating role of BS in this direct effect. This will allow for testing H1(a), H2 (a), and H3(a).

Method

Participants and procedure

Firstly, we conducted a survey among female undergraduate students at two universities in China. Students who volunteered to participate in the study signed an informed consent form. We used Questionnaire Star software (https://www.wjx.cn/) to create the online questionnaire. Participants accessed the questionnaire by clicking on the provided web link. The survey content included demographic information (such as age, major, and contact information) and the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI, Appendix A). After collecting the data, we excluded invalid questionnaires, defined as those with a completion time of less than 30 s. Following this exclusion, we collected 1029 valid responses. The age range of participants was 18–24 years (M = 19.47, SD = 3.41).

Then, based on the ASI scores, four groups were selected to participate in the study. First, we calculated the mean scores and standard deviation for HS (M = 2.97, SD = 0.86) and BS (M = 3.64, SD = 0.96) for all participants. Participants whose HS scores were one standard deviation above the mean were classified into the higher HS group, while those whose HS scores were one standard deviation below the mean were classified into the lower HS group. The same criteria were applied to classify participants into high BS and low BS groups. By combining these classifications, we formed four groups: Group 1, higher HS and higher BS; Group 2, higher HS and lower BS Group 3, lower HS and higher BS; and Group 4, lower HS and lower BS. Second, to avoid significant differences in group sizes that could affect the study results, we randomly selected 20 participants from each group. Thus, the final participants of Study 1 comprising 80 students. All participants in this study were female, with ages ranging from 18 to 23 years (M = 19.91, SD = 2.31).

Next, each participant was brought into the lab, and only one student participated in the study at a time. The researcher acted as the interviewer and instructed the participants to imagine that they were candidates in an interview. Then, they were given a recruitment brief with job requirements. Before the study began, we developed a detailed job description for the recruitment process (see Appendix B for details). The position outlined in the recruitment brief is designed to attract potential reserve cadres for a Fortune 500 enterprise. We explained to the participants that they should consider only whether they were qualified for the job, not whether they liked it or not. The recruitment brief was evaluated as effective by 10 postgraduate students majoring in psychology and 2 professors specializing in psychometrics. After reading the brief, the participants completed the evaluation of employment probability scale.

Measures

Ambivalent sexism

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI), developed by Glick and Fiske (2001), was used to measure participants’ HS and BS. The ASI consists of two 11-item subscales that assess HS and BS. Following the methodology of Glick et al. (2000), who used the scale in cross-cultural studies across nine countries, we deleted six reverse-scored items and included 16 items in the analysis, as detailed in Appendix A. Responses were indicated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). A total score was calculated from the two subscales (HS Cronbach’s α = 0.74; BS Cronbach’s α = 0.78). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results indicate that the scale fits well (KMO = 0.85, Bartlett’s sphericity test, p < 0.001). The items are distributed accurately to the subscales, and the factor loadings range from 0.41 to 0.81, demonstrating good validity.

Evaluation of employment probability

The scale was developed by our research group and consists of one item measuring the participants’ evaluation of their probability of a successful application (e.g., “Do you think you should be hired for the job?”) on a scale from 1 (absolutely not) to 7 (absolutely yes).

Results

Descriptive results

SPSS 20.0 software was used to analyze the relationship between variables and test the hypotheses. The descriptive statistics results for the main variables are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that participants’ HS is significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of employment probability (r = −0.65, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants’ BS is also significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of employment probability (r = −0.62, p < 0.001). These results provide preliminary evidence for our hypotheses.

The direct effect of female candidates’ ambivalent sexism

With HS and BS as independent variables and evaluations of employment probability as dependent variables, the results of ANOVA show that the main effect of HS is significant (F(1,77) = 212.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18). That is, participants with higher HS have lower evaluation of employment probability than those with lower HS. Therefore, H1(a) is supported. The main effect of BS is significant (F(1,77) = 18.25, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.23). That is, participants with higher BS have lower evaluation of employment probability than those with lower BS. Therefore, H2(a) is supported.

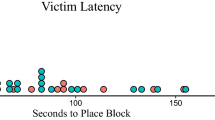

The moderating effect of female candidates’ BS

The interaction effect between HS and BS is significant (F (1,77) = 6.39, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.10). The results of the simple effect of HS and BS on the evaluation of employment probability are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Specifically, under the higher BS condition, participants with higher HS have a significantly lower evaluation of employment probability compared to those with lower HS (F (1,77) = 37.23, p < 0.001). However, under the lower BS condition, there is no significant difference in evaluation of employment probability between participants with higher HS and those with lower HS (F (1,77) = 0.37, p = 0.55). Therefore, H3(a) is supported.

Discussion of Study 1

Aligned with our hypotheses, the results of Study 1 indicate that both female candidates’ HS and BS have significant negative effects on their evaluation of their employment probability. Moreover, the results suggest that there is a risk-enhancement effect between HS and BS (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005), that is, female candidates’ BS can exacerbate the negative impact of HS. The reasons for these results may be that women’s self-confidence is deeply influenced by societal stereotypes, leading them to believe they are not sufficiently competent for challenging tasks (Curun et al., 2017; Dardenne et al., 2007). Additionally, protective paternalism may lead to women’s submission. If female candidates have a higher level of BS, they may be more likely to accept unfair restrictions (Moya et al., 2007). Under high HS condition, women’s BS seems to act as a “goodwill excuse” for the unfair treatment they suffer. Therefore, the interaction between HS and BS aggravates the cognitive bias of female candidates regarding their competence and employment probability.

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 is to investigate the direct effects of male interviewers’ HS and BS on their evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability, as well as the moderating role of BS in this direct effect. This will allow for testing H4(a), H5(a), and H6(a).

Method

Participants and procedure

In Study 2, we first conducted a survey among male undergraduate students at two universities in China. The procedure is similar to that of study 1. Questionnaire Star software was used to create the online questionnaire, and the participants accessed the questionnaire by clicking on the provided web link. The survey content included demographic information (such as age, major, and contact information) and the ASI. After using the same criteria as in Study 1 to exclude invalid data, 1029 valid responses remained. The age range of participants was 18–24 years (M = 19.47, SD = 3.41). The mean scores and standard deviation for HS (M = 3.11, SD = 1.57) and BS (M = 3.68, SD = 1.51) is calculated. Second, using the same criteria of study 1, four groups (80 students) were selected to participate in Study 2. All participants in this study were male, with ages ranging from 18 to 22 years (M = 19.35, SD = 2.01).

Then, each participant was brought into the lab, and only one student participated in the study at a time. The researcher asked the participants to imagine that he is participating in the interview as an interviewer. After that, they were given the recruitment brief with job requirements (as used in study 1) and a resume of a female candidate, containing her personal information, academic qualifications, and practice experience (see Appendix C for details). Before the study began, the resume was evaluated as effective by 10 postgraduates majoring in psychology and 2 professors majoring in psychometrics. After the participants read the recruitment brief and resume, they completed the evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability scale.

Measures

Ambivalent sexism

The adapted Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (the same scale used in study 1) was used to measure participants’ HS and BS (HS Cronbach’s α = 0.78; BS Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

Evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability

The scale used for the evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability is similar to the scale used in Study 1. In this study, the items have been modified to apply to the interviewer’s answers (e.g., “Do you think Wang should be hired for the job?”).

Results

Descriptive results

The descriptive statistics results for the main variables are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that participants’ HS is significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability (r = −0.61, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants’ BS is also significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability (r = −0.69, p < 0.001). These results provide preliminary evidence for our hypotheses.

The direct effect of male interviewers’ ambivalent sexism

With HS and BS as independent variables and evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability as dependent variables, the results of ANOVA show that the main effect of HS is significant (F(1,77) = 15.06, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.15). That is, participants with higher HS have lower evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability than those with lower HS. Therefore, H4(a) is supported. The main effect of BS is significant (F(1,77) = 55.50, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39). That is, participants with higher BS have lower evaluations of female candidates’ employment probability than those with lower BS. Therefore, H5(a) is supported.

The moderating effect of male interviewers’ BS

The interaction effect between HS and BS is significant (F (1,77) = 9.78, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.07). The results of the simple effect of HS and BS on the evaluations of employment probability are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2. Specifically, under the higher BS condition, participants with higher HS have a significantly lower evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability compared to those with lower HS (F(1,77) = 25.11, p < 0.001). However, under the lower BS condition, there is no significant difference in evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability between participants with higher HS and those with lower HS (F (1,77) = 0.78, p = 0.38). Therefore, H6(a) is supported.

Discussion of Study 2

The results of Study 2 indicate that both male interviewers’ HS and BS have significant negative effects on their evaluation of female candidates’ employment probability. The interactive effect between HS and BS is also found, that is, male interviewers’ BS can exacerbate the negative impact of HS. Consistent with previous research (Barron et al., 2024; Fleming et al., 2020; Hopkins-Doyle et al., 2019), this study confirms that when interviewers have high levels of ambivalent sexism, they tend to reduce the possibility of granting candidates employment opportunities. Similar to the results of Study 1, and consistent with the framework of the risk-enhancement model, interviewers’ benevolent sexism further reinforces the gender constraints imposed by hostile sexism on women. It aggravates the interviewer’s cognitive bias toward female candidates.

Study 3

The aim of Study 3 is to re-examine the direct impacts of HS and BS in both female candidates and male interviewers, test the mediating effects of evaluations of women’s competence, and explore the moderating effect of BS. This will allow for testing of H1–H6.

Method

Participants and procedure

We recruited participants from Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/), which is a leading online crowdsourcing platform like Mechanical Turk in China. It comprises 2.6 million respondents, whose personal information was confirmed, allowing for an authentic, diverse, and representative sample. To ensure the quality of the data, participants were restricted to individuals who are currently employed. We also excluded participants under the age of 18. Participants accessed the questionnaire by clicking on the provided web link. To minimize the concerns of common method variance (CMV), we collected data at two time points (Podsakoff et al., 2012). At Time 1, research assistants distributed questionnaires to 2000 participants who agreed to participate in the study. The questionnaire contained items on demographic information and ASI. A total of 1735 participants responded at Time 1. At Time 2, ~2 weeks later, research assistants distributed a second questionnaire to those 1735 participants. The Time 2, participants answered the survey containing evaluation of competence and employment probability for a leadership position. Invalid questionnaires with regular responses pattern were deleted, remaining 1557 valid responses. Of the participants, 66% were female. The age range of participants was 18–32 years (M = 25.77, SD = 3.01).

Measures

Ambivalent sexism

The adapted Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (the same scale used in Study 1 and 2) was used to measure participants’ HS and BS (HS Cronbach’s α = 0.83; BS Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

Evaluation of competence

We adapted the scale developed by Good and Rudman (2010) to measure participants’ evaluation of women’s competence for a leadership job. The scale consists of 4 items (see Appendix D for details). Responses were indicated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). A total score was calculated from the four items, with high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

Evaluation of employment probability

The similar scales used in Study 1 and 2 were used to measure participants’ evaluation of women’s employment probability for a leadership job. For male participants, the items have been modified (e.g., “Do you think a woman should be hired for a leadership job?”).

Results

Common method variance (CMV) check

Harman’s single-factor analysis method was used to check the CMV in this study. The results show that the explanation rate of the first factor for the total variance is 25.99%, which does not exceed the standard of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Hence, it appears that CMV showed no substantial threat to our research.

Descriptive results

The descriptive statistics results for the main variables are shown in Table 5. It can be seen that participants’ HS is significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of women’s competence(r = −0.29, p < 0.001) and employment probability for a leadership job (r = −0.25, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants’ BS is also significantly negatively correlated with their evaluation of female candidates’ competence (r = −0.20, p < 0.001) and employment probability (r = −0.19, p < 0.001). These results provide preliminary evidence for our hypotheses.

The direct effect of ambivalent sexism

We tested our hypotheses by linear regression and the PROCESS macro with bootstrapping techniques in SPSS. First, we divided the participants into female and male groups based on their self-reported gender. In female group, with HS and BS as independent variables and evaluations of women’s employment probability as dependent variables, the results of linear regression show that the direct effect of HS is significant (b = −0.09, se = 0.05, p = 0.001). Therefore, H1(a) is supported. The main effect of BS is also significant (b = −0.08, se = 0.05, p = 0.002). Therefore, H2(a) is supported. In male group, same analysis was conducted. The results of linear regression show that the direct effect of HS is significant (b = −0.11, se = 0.04 p < 0.001). Therefore, H4(a) is supported. The main effect of BS is also significant (b = −0.10, se = 0.03, p = 0.001). Therefore, H5(a) is supported.

The mediating effect of evaluation of competence

In female group, with HS and BS as independent variables, evaluation of women’s competence as mediating variable and evaluations of women’s employment probability as dependent variables, the results of PROCESS macro with bootstrapping (Model 4) show that, female participants’ HS (b = −0.32, se = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.39, −0.26]) and BS (b = −0.24, se = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.32, −0.17]) are negatively related to evaluation of women’s competence. Evaluation of women’s competence is positively related to evaluation of employment probability (b = 0.10, se = 0.03, p = 0.001, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.16]). Besides, the mediating effects of evaluation of competence in the relationship between HS and employment probability (b = −0.03, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.01]), as well as in the relationship between BS and employment probability are significant (b = −0.02, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.04, −0.01]). Therefore, H1(b) and H2(b) are supported.

In male group, same analysis was conduct. The results show that, male participants’ HS (b = −0.27, se = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.32, −0.21]) and BS (b = −0.27, se = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.33, −0.22]) are negatively related to evaluation of women’s competence. Evaluation of women’s competence is positively related to evaluation of employment probability (b = 0.19, se = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.23]). Besides, the mediating effects of evaluation of competence in the relationship between HS and employment probability (b = −0.05, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.04]), as well as in the relationship between BS and employment probability ate significant (b = −0.04, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.03]). Therefore, H4(b) and H5(b) are supported.

The moderating effect of BS

In female group, with HS as independent variable, BS as moderating variable, and evaluations of women’s employment probability as dependent variables, the results of PROCESS macro with bootstrapping (Model 1) show that, the moderating effect of BS is significant (b = −0.02, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.01]). The result of conditional effect shows that the effect of HS on employment probability at lower level of BS is not significant (b = 0.01, se = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.04]), while at higher level of BS is significant (b = −0.06, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.09, −0.04]). Therefore, H3(a) is supported.

In male group, same analysis was conduct. The results show that, the moderating effect of BS is significant (b = −0.02, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.01]). The result of conditional effect show that the effect of HS on employment probability at lower level of BS is not significant (b = −0.02, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.01]), while at higher level of BS is significant (b = −0.04, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.02]). Therefore, H6(a) is supported.

The moderated mediating effect

In female group, with HS as independent variable, BS as moderating variable, evaluations of women’s competence as mediating variable, and evaluations of women’s employment probability as dependent variables, the results of PROCESS macro with bootstrapping (Model 7) show that, the moderated mediating effect is significant (b = −0.01, se = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.02, −0.01]). The result of conditional effect shows that the indirect effect of HS on employment probability at lower level of BS is not significant (b = −0.01, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.01]), while at higher level of BS is significant (b = −0.03, se = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.01]). Therefore, H3(b) is supported.

In male group, same analysis was conducted. The results show that, the moderated mediating effect is significant (b = −0.01, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.01]). The result of conditional effect shows that the indirect effect of HS on employment probability at lower level of BS (b = −0.02, se = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.04, 0.01]), is significantly weaker than that at higher level of BS (b = −0.04, se = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.06, −0.03]). Therefore, H6(b) is supported.

Discussion of Study 3

In Study 3, we provide robust evidence that both forms of sexism—hostile and benevolent—continue to exert significant negative influences on the evaluation of women’s employment probabilities. One of the key contributions of Study 3 is its examination of the mediating role of competence evaluation. Our findings confirmed that perceptions of competence serve as a critical intermediary in the relationship between ambivalent sexism and employment probability. Specifically, when either female candidates or male interviewers hold sexist attitudes, it leads to an underestimation of women’s professional capabilities. This diminished perception of competence, in turn, significantly lowers the likelihood of successful job application outcomes for female candidates (Dardenne et al., 2007). Another important aspect of Study 3 was its investigation into the moderating effect of benevolent sexism. The results revealed that the presence of benevolent sexism can exacerbate the negative impact of hostile sexism. Benevolent sexism, often characterized by seemingly positive but patronizing attitudes, subtly reinforces stereotypes that undermine women’s professional ambitions and perceived competence (Bollier et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2020). This interplay between benevolent and hostile sexism creates a more complex and harmful environment for women seeking leadership roles (Connelly and Heesacker, 2012; Hammond and Sibley, 2011).

General discussion

This research contributes significantly to the understanding of how ambivalent sexism—comprising both hostile and benevolent forms—affects the women’s employment. Through two quasi-experimental studies (Study 1 and Study 2) and one large-scale survey study (Study 3), we explored the dual impact of ambivalent sexism held by female candidates and male interviewers on women’s job interview outcomes. Our findings consistently demonstrated that both female candidates and male interviewers who hold ambivalent sexist attitudes tend to underestimate women’s competence. This underestimation, in turn, negatively influences their evaluations of the probability of employment success for female candidates. A particularly noteworthy discovery was the moderating role of benevolent sexism. Contrary to its seemingly positive or protective facade, benevolent sexism significantly intensifies the negative effects of hostile sexism. This suggests that even ostensibly favorable attitudes toward women can perpetuate harmful stereotypes and hinder career advancement. The coexistence of both forms of sexism creates a synergistic effect that compounds the disadvantages faced by women in professional settings.

This research makes significant contributions to the existing literature on gender sexism and its impact on women’s employment. Firstly, we extend prior studies that typically adopt a single perspective, focusing either on the biases held by female candidates or male interviewers (Bourabain, 2021; de Sousa Santos et al., 2020; Fleming et al., 2020). This research simultaneously examines the effects of ambivalent sexism from both parties. By delving into how these biases interact during the interview process, we provide a more comprehensive understanding of the ambivalent sexism. This dual-perspective approach reveals the complex ways in which ambivalent sexism from both female applicants and male interviewers can influence the outcomes for women, offering new insights that extend beyond the limitations of earlier single-perspective studies.

Secondly, this research investigates the critical role of perceptions of a female candidate’s competence as an intermediary factor between ambivalent sexism and the employment probability. Building on calls from previous research (e.g., Barron et al., 2024; Hopkins-Doyle et al., 2019; Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2023) for deeper analysis of the mechanisms through which gender sexism affects candidate evaluation, our research provides evidence that biased perceptions of competence significantly mediate the impact of ambivalent sexism. We demonstrate that when either female candidates or male interviewers hold ambivalent sexism, it leads to an underestimation of women’s competence. This diminished perception of competence, in turn, lowers the evaluation of employment probability. By elucidating this mechanism, our findings offer valuable insights into how gender sexism can subtly yet profoundly affect the evaluation of female candidates’ qualifications, ultimately influencing their career advancement opportunities.

Thirdly, this research advances the literature by exploring the interactive effects of hostile and benevolent gender sexism, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of ambivalent sexism. Our research demonstrates that the coexistence of seemingly positive but patronizing attitudes (benevolent sexism) alongside overtly negative stereotypes (hostile sexism) can compound the challenges faced by female job applicants. Specifically, we show that benevolent sexism significantly exacerbates the negative impacts of hostile sexism, creating a synergistic effect that intensifies barriers for women in the hiring process. This finding not only broadens the scope of existing research on ambivalent sexism (Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2023; Rubin et al., 2019; Warren et al., 2020) but also validates the applicability of risk-enhancement theory (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005) within the context of gender bias in employment settings. By uncovering these interactive dynamics, our research highlights the need for more comprehensive approaches to addressing gender biases in professional environments, ensuring fairer and more inclusive hiring practices.

Moreover, our research offers some practical implications. These results underscore the critical need for increased social awareness regarding gender biases in the workplace. Organizations and policymakers must recognize that both overtly hostile and covertly benevolent forms of sexism contribute to systemic barriers for women. Efforts should be directed toward fostering environments that challenge these biases and promote equitable opportunities for all genders. Moreover, our research has practical implications for female job seekers. By understanding the potential impacts of internalized biases, women can work toward establishing more realistic and positive self-perceptions. Educational programs and workshops aimed at building confidence and resilience could play a crucial role in mitigating the adverse effects of ambivalent sexism.

Limitations and future directions

First, while our findings provide valuable insights into sexism in the Chinese workplace, the specific cultural and social contexts of China may limit the generalizability of these results to other countries or regions. Therefore, we encourage future research to explore how cultural factors, such as unique societal norms and workplace dynamics, influence the manifestation and perception of sexism in different cultural settings. Second, there is a difference between the estimation and the final decision of employment. This research did not directly examine the impact of the interviewer’s ambivalence in a real interview situation. Therefore, it is necessary for future research to examine the impact of HS and BS on a real interview situation. Third, this research used the examination of sexism in interviewing activities, and a sample of college students facing employment was used. However, given the lasting and profound impact of ambivalent sexism on women’s career, it is necessary for future research to use other samples (e.g., real job seekers or interviewers) and conduct in-depth research on this issue. Fourth, while our current research provides valuable insights into the impacts of ambivalent sexism on female applicants, we acknowledge the significance of comparing outcomes for male and female candidates in future research. Future studies can explore whether hostile and benevolent sexism exert different effect on male and female applicants. Finally, future research can examine the effects of HS and BS on career development beyond the interview process, such as career choice, duty fulfillment, appointment and promotion, dismissal, and other activities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alexander RD, Borgia G (1979) On the origin and basis of the male-female phenomenon. In: Sexual selection & reproductive competition in insects. Academic Press, 111Fifth Aven, New York, pp 417–440

Allport GW (1954) The nature of prejudice. J Negro Hist 52(3):390–393

Bareket O, Fiske ST (2023) A systematic review of the ambivalent sexism literature: hostile sexism protects men’s power; benevolent sexism guards traditional gender roles. Psychol Bull 149(11-12):637–698

Barron K, Ditlmann R, Gehrig S, Schweighofer-Kodritsch S (2024) Explicit and implicit belief-based gender discrimination: a hiring experiment. Manag Sci 71:1600–1622

Becker JC, Glick P, Ilic M, Bohner G (2011) Damned if she does, damned if she doesn’t: consequences of accepting versus confronting patronizing help for the female target and male actor. Eur J Soc Psychol 41(6):761–773

Bollier T, Dardenne B, Dumont M (2007) Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: consequences for women’s performance. J Personal Soc Psychol 93(5):764–779

Bourabain D (2021) Everyday sexism and racism in the ivory tower: the experiences of early career researchers on the intersection of gender and ethnicity in the academic workplace. Gend Work Organ 28(1):248–267

Brandt MJ (2011) Sexism and gender inequality across 57 societies. Psychol Sci 22(11):1413–1418

Connelly K, Heesacker M (2012) Why is benevolent sexism appealing? Associations with system justification and life satisfaction. Psychol Women Q 36:432–443

Curun F, Taysi E, Orcan F (2017) Ambivalent sexism as a mediator for sex role orientation and gender stereotypes in romantic relationships: a study in Turkey. Interpersona Int J Personal Relatsh 11(1):55–69

Cheng P, Shen W, Kim KY (2020) Personal endorsement of ambivalent sexism and career success: an investigation of differential mechanisms. J Bus Psychol 35(6):783–798

Chawla N, Gabriel AS (2024) From crude jokes to diminutive terms: exploring experiences of hostile and benevolent sexism during job search. Pers Psychol 77(2):747–787

Dardenne B, Dumont M, Bollier T (2007) Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: consequences for women’s performance. J Personal Soc Psychol 93:764–779

de Sousa Santos J, Júnior JDOL, de Mesquita RF, Cruz VL (2020) Women’s self-perception of opportunities and challenges for entrepreneurship. In: Handbook of research on approaches to alternative entrepreneurship opportunities. IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp 379–394

Eagly AH, Karau SJ (2002) Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev 109(3):573

Eagly AH, Mladinic A (2016) Are people prejudiced against women? Some answers from research on attitudes, gender stereotypes, and judgments of competence. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 5(1):1–35

Erin DR, Kadie RR, Germine HA (2017) Perceptions of male and female stem aptitude: the moderating effect of benevolent and hostile sexism. J Career Dev 44(2):1–15

Fergus S, Zimmerman MA (2005) Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health 26:399–41

Fleming AC, Hlebasko H, Adams SC, Roach KN, Christiansen ND (2020) Effects of sexism and job–applicant match on leadership candidate evaluations. Soc Behav Personal Int J 48(9):1–8

Glick P, Diebold J, Bailey-Werner B, Lin Z (1997) The two faces of Adam: ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 23(12):1323–1334

Glick P, Fiske ST (1996) The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Personal Soc Psychol 70:491–512

Glick P, Fiske ST (2001) An ambivalent alliance. hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am Psychol 56(2):109

Glick P, Fiske ST (2010) Hostile and benevolent sexism: measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychol Women Q 21(1):119–135

Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, Saiz J, Abrams D, Masser B, López WL (2000) Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. J Personal Soc Psychol 79:763–775

Glick P, Zion C, Nelson C (1988) What mediates sex discrimination in hiring decisions? J Personal Soc Psychol 55:178–186

Good JJ, Rudman LA (2010) When female applicants meet sexist interviewers: the costs of being a target of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles 62:481–493

Gutierrez BC, Leaper C (2024) Linking ambivalent sexism to violence-against-women attitudes and behaviors: a three-level meta-analytic review. Sex Cult 28(2):851–882

Hammond MD, Sibley CG (2011) Why are benevolent sexists happier? Sex Roles 65:332–343

Hopkins-Doyle A, Sutton RM, Douglas KM, Calogero RM (2019) Flattering to deceive: Why people misunderstand benevolent sexism. J Personal Soc Psychol 116(2):167–192

Kosakowska-Berezecka N, Bosson JK, Jurek P, Besta T, Olech M, Vandello JA, Van der Noll J (2023) Gendered self-views across 62 countries: A test of competing models. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 14(7):808–824

Masser BM, Abrams D (2004) Reinforcing the glass ceiling: the consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates. Sex Roles 51(9-10):609–615

Mccreary DR, Newcomb MD, Sadava SW (1998) Dimensions of the male gender role: a confirmatory analysis in men and women. Sex Roles 39(1-2):81–95

Moya M, Glick P, Expósito F, de Lemus S, Hart J (2007) It’s for your own good: benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 33:1421–1434

Moscatelli S, Menegatti M, Ellemers N, Mariani MG, Rubini M (2020) Men should be competent, women should have it all: multiple criteria in the evaluation of female job candidates. Sex Roles 83:269–288

Napier JL, Thorisdottir H, Jost JT (2010) The joy of sexism? A multinational investigation of hostile and benevolent justifications for gender inequality and their relations to subjective well-being. Sex Roles 62(7-8):405–419

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Rose AJ, Rudolph KD (2006) A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol Bull 132(1):98–131

Rubin M, Paolini S, Subašić E, Giacomini A (2019) A confirmatory study of the relations between workplace sexism, sense of belonging, mental health, and job satisfaction among women in male-dominated industries. J Appl Soc Psychol 49(5):267–282

Swim JK, Aikin KJ, Hall WS, Hunter BA (1995) Sexism and racism: old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J Personal Soc Psychol 68(2):199–214

Warren CR, Zanhour M, Washburn M, Odom B (2020) Help or hurting? Effects of sexism and likeability on third party perceptions of women. Soc Behav Personal Int J 48(10):1–13

Watkins MB, Kaplan S, Brief AP, Shull A, Dietz J, Mansfield MT, Cohen R (2006) Does it pay to be a sexist? The relationship between modern sexism and career outcomes. J Vocat Behav 69(3):524–537

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024QG187), the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of Shandong Normal University (2024YTR008), Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Soft Science Project: 2025RZB0504), the Center for Development of Degree and Graduate Education of the Ministry of Education of China 2024 Thematic Case Project (ZT-2410351006), the Major Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Zhejiang Province (21XXJC04ZD), the Zhejiang Province Humanities Laboratory for “Ecological Civilization and Environmental Governance”, Key Research Center of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Zhejiang Province (Institute of Medical Humanities, Wenzhou Medical University), Wenzhou Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Annual Project (25WSK013YB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First author: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; second author: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; third author: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Normal University (No. sdnu-2023-08-30-01). The approval was granted on August 30, 2023, prior to the commencement of the research. It covered the full scope of the study, including all procedures involving human participants, data collection methods, informed consent processes, and data storage and protection protocols.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained directly from all participants on the day of their participation. Specifically, consent was collected on September 15, 2023 (Study 1), October 20, 2023 (Study 2), and November 7, 2023 (Study 3) by the research team at Shandong Normal University. The scope of consent included voluntary participation, use of data for research purposes, and inclusion of anonymized data in publications. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures, assured of their right to withdraw at any time, and guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. They were also informed that no foreseeable risks were associated with participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Xia, X. & Wang, P. Two obstacles to the success of women: ambivalent sexism from interviewers and candidates themselves. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1276 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05583-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05583-4