Abstract

This study investigates the impact of modern technological tools, specifically the Framapad online word processor and the Moodle platform, on collaborative writing among second language (L2) students in Algerian universities. The study involved 24 third-year French as a second language students, divided into a control (GT) and experimental (GE) group, each comprising three subgroups. The data were analysed in two phases: initial and revision. Initially, the produced fables were evaluated based on four criteria: structure, content, language, and collaborative writing. In the revision stage, the produced fables were analysed, focusing on the textual changes made—additions, deletions, replacements, and text rearrangements. A comparative assessment was conducted to examine the impact of technology on the quality and creativity of collaborative writing. The results reveal that the experimental group outperformed the control group in structuring fables, exhibiting better integration of plot and moral elements. Both groups addressed Algerian issues, but the experimental group displayed greater creativity. The experimental group demonstrated more effective teamwork and tended to enhance storytelling during revisions by adding more elements and deleting fewer than the control group. These results highlight the potential benefits of integrating technology into language learning contexts to improve writing proficiency and foster collaborative skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exploring the impact of digital scaffolding on collaborative writing practices among second language (L2) students remains an underexplored area in applied linguistics. Existing research in educational linguistics has examined various aspects of L2 instruction, including foreign language teaching strategies (e.g., Abushihab 2020; Algazo 2023; Al-Shahwan 2024; Swaie and Algazo 2023; Alghazo et al. 2023), as well as the role of digital technology in certain areas of L2 education (see, for example, Abusalim et al. 2024; Alzobidy et al. 2024; Rayyan et al. 2024). However, the influence of digital technology on collaborative writing among L2 learners appears to be one of the overlooked domains in the Algerian context.

Collaborative writing, where two or more students work together to produce a single text, has become a widely used approach in language teaching (Rezeki 2016; Zhang and Zou 2022). This method not only enhances students’ ability to construct knowledge collectively but also fosters autonomy, creativity, and critical thinking (Hodges 2002; Lowry et al. 2004; Nevid et al. 2012). In the context of technology-assisted writing, students collaborate through digital tools such as word processing software, making the writing process a shared experience rather than a solitary task. By working together, they benefit from collective scaffolding, which helps them develop a deeper understanding of linguistic structures and writing techniques compared to working alone (Storch 2011; Swain 2010).

At the same time, the rapid rise of digital culture and technological advancements over the past few decades has significantly influenced education, including the way writing skills are taught and developed. While research highlights the benefits of integrating information and communication technologies (ICTs) into teaching and learning, their adoption in Algeria remains limited (Boussebha 2023). Many universities still struggle to incorporate Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) into their curricula due to various challenges, such as budget constraints, inadequate infrastructure, a lack of ICT training, technical difficulties, and even resistance from both students and educators (Bouchefra 2016). Moreover, despite the growing global interest in digital collaborative learning, research on this topic within the Algerian context remains scarce, leaving a significant gap in the literature that needs further exploration.

This study examines how Framapad and Moodle can facilitate collaborative writing among second language (L2) students in Algerian universities, addressing a research gap in ICT integration in Algerian higher education. Framapad was chosen for its real-time, interactive collaboration features, making writing more engaging and dynamic, while Moodle provides a structured space for feedback and revisions. These tools complement each other, offering both immediate interaction and ongoing support for student writing. By investigating their impact, this study not only raises awareness among educators, students, and policymakers about the role of technology in education but also enriches the limited research on online collaborative writing in Algeria and similar contexts. This study is guided by the following research questions:

-

1.

How do Framapad and Moodle platforms affect the collaborative writing of French as a second language students?

-

2.

How do the control and experimental groups differ in their creativity during collaborative writing?

Literature review

Online collaborative writing

Collaborative writing can be defined as an activity in which two or more writers collaborate together to produce a piece of writing or a single text (Storch 2019). In educational environments, the practice of collaborative writing is traditionally an activity that takes place in the physical classroom, where learners engage in this activity using paper and pen while communicating face-to-face. However, with the rapid development of technology in the last three decades, it has become possible to carry out collaborative writing through the use of computer-mediated platforms, such as wikis, Google Docs, and Framapad. Therefore, in the last two decades, several studies (e.g., Farrah 2015; Lee 2010; Rahimi and Fathi 2022; Wang 2024) have explored the impact of digital tools on collaborative writing in L2 learning, focusing on how technology enhances writing performance, student engagement, and learning autonomy in different educational contexts. For example, Rahimi and Fathi (2022) conducted a study to explore the impact of wiki-mediated collaborative writing on university students’ writing performance, writing self-regulation, and writing self-efficacy. The findings showed that students in the wiki-mediated collaborative writing group outperformed those in the non-wiki collaborative writing group. The study also revealed several peer writing mediations that enhanced students’ writing content (clarity of message), writing organization (sequencing of information), and language use (grammar, vocabulary, and mechanics) in the wiki space.

Furthermore, Wang (2024) conducted a study in a Chinese university, exploring how digital tools impact L2 collaborative writing. The findings highlight that these tools help foster a sociocognitive learning community where students actively engage, construct knowledge, and develop their language skills. The findings suggest that integrating Web 2.0 applications into collaborative writing makes the process more flexible and interactive, allowing students to co-create content without the usual time and space constraints. These tools also provide additional support through multimedia and interactive features, enriching the learning experience (Shadiev et al. 2017; Zhang and Zou 2022).

Framapad and Moodle

Framapad and Moodle, two Web 2.0 applications, can significantly simplify the online collaborative writing process and enhance students’ learning and interactions. Web 2.0 refers to the second generation of internet-based services that emphasize user-generated content, real-time collaboration, and interactivity (O’Reilly 2007). Unlike static Web 1.0 platforms, Web 2.0 technologies facilitate dynamic participation, allowing users to create, edit, and share content collectively. These applications support social constructivist learning, where knowledge is co-constructed through interaction (Garrison and Anderson 2003).

Farmapad is a technology tool that facilitates online communication and collaboration, enabling users to share ideas and cooperate in real-time. It is similar to other technology tools designed for collaborative work purposes, such as Google Docs, blogs, and wikis (Berkowitz et al. 2023; Linh 2021). It includes word processing capabilities referred to as a pad, which enables multiple users (i.e., writers) to work on the same document simultaneously or asynchronously (Linh 2021). Collaborative text editors, such as Framapad, enable real-time collaboration on shared documents, thereby fostering collaborative writing processes (Brodahl et al. 2011; Zhang and Zou 2022). These editors are dynamic facilitators who streamline collaborative writing by promoting interaction among peers (Hadjerrouit 2011; Kessler et al. 2012; Woodrich and Fan 2017). Furthermore, they facilitate the exchange of ideas, editing, and revision processes, thereby enhancing the overall quality of written texts (Aydin and Yildiz 2014; Mak and Coniam 2008; Zhang and Zou 2022).

Previous studies (e.g., Berkowitz et al. 2023; Linh 2021; Talib and Cheung 2017) have shown that using Web 2.0 tools, including Framapad, helps learners improve their writing. For example, Linh (2021) conducted a study with 108 students studying a second language (L2) at a university in Vietnam. The data were collected through observations of the students’ writing using the technology tool Framapad for five weeks, as well as online questionnaires administered to the students in the final week of the study. The results showed that students’ writing ability improved, and questionnaire results revealed that students had positive attitudes toward using Framapad in their collaborative writing activities. Although the research investigating the Framapad technology tool is limited, findings in the literature overall indicate that incorporating Framapad into collaborative writing activities in writing courses can often enrich the learning experience and contribute to the development of learners’ writing skills.

Moodle, a free and open-source e-learning platform, serves as a cross-platform course management system widely utilized in online teaching and learning (Wu and Hua 2008; Gamage et al. 2022). Moodle, an acronym for Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment, is more than just a course management system; it is rooted in socio-constructivist pedagogy and designed to support interactive, collaborative learning (Brandle 2005). As Brandle notes, Moodle facilitates inquiry- and discovery-based learning through its flexible, modular architecture, making it especially suited for language learning tasks that benefit from peer interaction and scaffolding principles that align closely with the sociocultural framework of this study. This platform operates on the principles of social constructivism, aiming to facilitate online interaction and collaboration among educators and students (Tang 2013), allowing both teachers and students to contribute content (El-Maghraby 2021).

Several studies (e.g. El-Maghraby 2021; Eskandari and Soleimani 2016; Gulbinskienė et al. 2017; Kargiban and Kaffash 2011; Ziyad 2016) have noted Moodle’s role advantages in teaching and learning of L2s, including increasing students’ motivation, improving their attitudes, and enhancing learning outcomes in L2 learning. For example, El-Maghraby (2021) conducted a study to investigate the impact of the Moodle platform on the writing skills of sixty first-year L2 university students. The findings revealed that students demonstrated improved writing performance. Similarly, Ziyad (2016) investigated the impact of the Moodle platform on 24 second language (L2) university students in Morocco. The results showed that Moodle facilitated collaborative writing activities, maintained student motivation during out-of-class learning, and facilitated the exchange of feedback. Moodle’s potential as a digital learning platform is highly promising, particularly in enhancing the writing skills of L2 learners. Its effectiveness in higher education has made it a preferred choice among educators, highlighting its capacity for seamless integration into second and foreign language classes (Prasetya 2021; Tomo et al. 2022).

Theoretical framework

The sociocultural theory

This study is grounded in Sociocultural Theory, which posits that people learn and develop through interactions with others and the cultural tools available to them (Vygotsky 1978). When it comes to collaborative writing, this means that working with peers and using digital resources can significantly shape how students develop their writing skills. Two key ideas from this theory—the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and scaffolding—help explain how learners progress with the right kind of support. The ZPD is the gap between what a learner can do on their own and what they can achieve with guidance from a more knowledgeable peer or teacher (Wass et al. 2011). To bridge this gap, scaffolding provides just the right amount of support to help learners tackle challenges beyond their current abilities (Wilson and Devereux 2014). In a collaborative writing setting, this support comes from peer discussions, teacher feedback, and digital tools that guide students through the writing process.

Framapad and Moodle serve as digital scaffolding tools, providing students with a space to collaborate, share ideas, and refine their work. Framapad enables real-time collaboration, allowing students to support one another as they write. Moodle, on the other hand, offers a more structured environment for feedback and reflection, enabling students to review suggestions and refine their work at their own pace. By combining immediate interaction with structured support, these tools help students build confidence, take ownership of their writing, and develop stronger writing habits.

The ZPD also emphasises the importance of dynamic learning, which means that students make the most progress when they receive just enough help to advance their skills (Storch 2019). Collaborative writing encourages this process by letting students exchange ideas, build on each other’s knowledge, and problem-solve together. Web 2.0 tools, such as Framapad and Moodle, take this a step further by making collaboration more accessible and engaging for all learners, especially those who may require additional support. By creating a space where students learn from each other and refine their writing in a supportive environment, digital scaffolding plays a crucial role in developing both writing skills and collaborative learning habits.

Methodology

Setting and participants

The study was conducted at the French department of an Algerian University. The participants were enrolled in a writing course. The class consisted of 34 third-year students, of whom 24 volunteered to participate in the study. According to departmental language assessment and curriculum benchmarks, all participants demonstrated a B2 level of French proficiency, as defined by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), indicating upper-intermediate competence in reading and writing skills. The sample of participants consisted of 5 males and 19 females, with ages ranging from 21 to 23. All participants are native Algerian Arabic speakers and are majoring in French, which is a second language for them in the Algerian context.

Data collection

Data were collected by dividing student participants into two groups: a control group (GT) and an experimental group (GE). Each group consisted of 12 students, further subdivided into three subgroups of 4 students each. Subgroup formation was done using a stratified random assignment method, ensuring that gender balance and general academic performance (based on prior writing course assessments) were evenly distributed across the six subgroups (GT1, GT2, GT3 for the control group and GE1, GE2, GE3 for the experimental group). This strategy aimed to minimise pre-existing disparities among subgroups and to ensure equitable collaborative task dynamics.

Experimental procedure: protocol sessions

The experiment followed a protocol consisting of seven sessions, as detailed in Table 1 below. All participants, divided into six subgroups, attended the initial three sessions (Sessions 1, 2, and 3). Sessions 4 and 5 were specifically designated for students in the control group, while Sessions 6 and 7 were exclusively for those in the experimental group. The initial three sessions, which were for all participants, aimed to enhance students’ understanding of the characteristics of the fable genre, learning about the symbolic values of animals, narrative and actantial patterns, the peculiarities of 17th-century language, and mastering verb tenses, as well as using the French pronoun on in a fable. Sessions 4 and 5 were designated for participants in the control group to develop collective analysis, writing, and revision skills in a traditional environment, while sessions 6 and 7 were exclusively for students in the experimental group to develop these skills in a digital environment.

In the experimental group, after composing their fables collaboratively using Framapad, students were instructed on how to export their drafts as Word or PDF files. The instructor conducted a guided demonstration (Session 7) showing students how to access Moodle’s Assignment submission module, locate the relevant activity, and upload their revised fable. They were also shown how to review feedback through the Moodle interface and submit a second draft for final evaluation.

The Moodle tools used in this study primarily included the Assignment activity, which allowed individual students to upload the group’s collaborative text, and the Feedback section, where both peer and instructor comments were shared. No real-time collaborative writing occurred within Moodle; rather, it was used as a structured platform for document submission, revision tracking, and reflective feedback. The six subgroups were asked to write a fable addressing a subject in Algerian society. The fable should encompass a narrative and an explicit moral. The participants were also instructed about the allocated time for the writing process. The participants in the experimental subgroups wrote fables using Framapad, a collaborative text editor software, while the students in the control subgroups carried out the writing process in a traditional manner, working face-to-face in a classroom setting and composing their fables by hand using pen and paper. These handwritten drafts were then collected by the instructor and later digitised (typed) for the purpose of evaluation and comparative analysis.

The writing process proceeded in two stages. In the first stage, subgroups wrote their fables and submitted them; after that, one of the authors corrected and evaluated their draft fables. Then, participants were asked to revise their written fables for publication on the Moodle platform. In the experimental group, students received clear guidance on how to publish, review, and refine their work on Moodle. They were walked through the process of uploading their drafts, providing peer feedback, and making revisions before submitting the final version. Unlike traditional collaborative writing, where feedback occurs in real-time, Moodle enables students to collaborate asynchronously, track their progress, and receive structured input from both peers and their instructor.

After submitting their second drafts to be published on the platform, the author who had corrected the first draft also reviewed and corrected the second drafts of the subgroup’s writing and evaluated them. By evaluating the second draft of the students’ written fables, the data collection process of the study was completed.

Data analysis procedure

After the protocol sessions were completed, the participants in the six subgroups had to choose a topic and write a fable related to Algerian contextual issues. Then, there were two rounds of analysis of the six subgroups’ writing works. In the first round of analysis, the fables produced through collaborative writing by participants in subgroups were evaluated based on four criteria (i.e., Fable Structure, Content, Language, and Collaborative writing) derived from the text characteristics. On each criterion, a positive (+) sign was given for good performance and a negative (-) sign for poor performance. At this stage, the subgroups (i.e., GE1, GE2, and GE3) forming the experimental group used the word processor Farmapad in writing their fables, while the subgroups (i.e., GT1, GT2, and GT3) forming the control group wrote theirs in the traditional face-to-face manner. This round of analysis aimed to compare the performance of the experimental group with that of the control group. In the second round of analysis, the subgroups were asked to revise their fables for publication on the Moodle platform. It is worth mentioning, as clear in Table 1, that the experimental group received training on publishing on the platform, while the control group did not receive such training.

The subgroups’ written work was evaluated using Fabre’s (1990) framework, which outlines four key types of text revisions: addition, deletion, replacement, and movement. According to Fabre, writers refine their drafts by adding new words, phrases, or sentences to enhance clarity and detail. They also delete unnecessary or redundant elements, replace words or phrases with more precise alternatives, and rearrange text to improve coherence and flow. This approach provides valuable insight into how students develop their writing skills, shedding light on their cognitive and linguistic growth throughout the revision process.

Analysis and results of fables written before publishing

In order to analyse the fables written online and in person by the six subgroups, we created an analysis grid based on the characteristics of the text to be written. The grid analysis includes aspects of fable structure, content, language, and collaborative work. Specifically, the evaluator has assessed specific elements in each aspect:

-

1.

Fable Structure: Includes elements of introduction, plot development, and moral.

-

2.

Content: Includes elements of theme relevance/symbolism and creativity.

-

3.

Language: Includes elements of verbal tenses and pronoun usage.

-

4.

Collaborative Writing: Includes elements of organisation/management and cohesion/interaction.

Based on these four aspects and their elements, the subgroup writing work has been graded with a positive sign (+) for good performance or with a negative sign (-) for poor or unsatisfactory performance. Table 2 below illustrates the results of the groups, graded according to the criteria adopted in this study for evaluating the writing work of the six subgroups.

A closer examination of individual subgroup performance reveals key contrasts. GT1 and GE2 received the most negative evaluations across the four assessed aspects. GT1 struggled particularly in plot integration and collaborative organisation. Their fable lacked narrative coherence, and member roles were not clearly defined, resulting in low interaction and weak story progression. GE2, while in the experimental group, also received negative marks in plot and moral development, suggesting that digital tools alone were insufficient to offset limited group cohesion and planning. In contrast, GE3, the best-performing subgroup, demonstrated strong structure, creativity, and effective collaboration. Their fable employed vivid imagery, symbolic animal characters, and a clear moral message, supported by high levels of interaction and idea-sharing throughout the process. GE3’s performance exemplifies the pedagogical potential of well-orchestrated digital scaffolding when combined with active peer engagement and narrative creativity.

Aspect of fable structure

An analysis of the fables shows that both control group and experimental group did good performance. In a sense, all subgroups incorporated an introduction into their writing, indicating a solid understanding of the fundamental structure of the genre under study. For example, the subgroup GE3 from experimental group wrote: “Dans mon pays l’Algérie, Dans un très beau désert doré, Vivaient des animaux, une population respectée. Parmi eux, trois amis malins et rusés, Le corbeau, le chameaux et le renard, complices et aguerris.” [In my country Algeria, in a beautiful golden desert, lived animals, a respected population. Among them, three clever and cunning friends, the raven, the camel, and the fox, accomplices and seasoned]. Similarly, GT3 from the control group wrote: “Un jeune rêveur nommé Rida, l’esprit fier, Se préparait pour partir, loin des frontières. Vers des villes nouvelles, pleines de mystères, Pour faire son avenir, loin des chimères”. [A young dreamer named Rida, with a proud spirit, was preparing to leave, far from the frontiers. Towards new cities, full of mysteries, to make his future far from chimaeras]. The performance of all subgroups was very good, and all of them received a positive result (+), indicating no difference between the control group and the experimental group in this regard.

Regarding the element of plot, subgroups GT2, GE1, and GE3 successfully integrated a plot into their fables. For example, the subgroup GE1, which wrote about the topic of unemployment, carefully depicted and described unemployment as an obstacle to the well-being of young Karim (the central character of the story). GE1 wrote:

Dans cette ville, vivait un jeune homme, appelé Karim, plein d’espoir, avec un cœur brave en somme. Il cherchait du travail, une chance à saisir, Pour bâtir son avenir, sans jamais défaillir. Mais les portes se fermaient, l’emploi manquait, La frustration grandissait, le moral s'éteignait. Karim se sentait dépassé, Par ce chômage tenace, son avenir est menacé.

In this town lived a young man, named Karim, full of hope, a brave heart within. He sought work, a chance to seize, to build his future, never to cease. But doors closed, jobs were scarce, Frustration grew, morale became terse. Karim felt overwhelmed, by this persistent unemployment, his future seemed felled.

On the other hand, subgroups GT1, GT3, and GE2 encountered serious challenges in integrating plots in their fables. For example, GE3 did not introduce the plot well and instead described the animals’ reaction to these influencers. GT1 also did not develop the plot well about Imane, a character in the fable who is a high school student. Specifically, they did not clearly explain Imane’s sadness or the context in which Iman met the old man in the story. Nevertheless, in terms of the element of development, both groups —the control group and the experimental group —developed their fables satisfactorily, demonstrating a comprehension of narrative progression. For example, in the experimental group, the subgroup GE3 has made a remarkable effort in developing their ideas and adopting a creative approach that includes using animals to effectively represent the subject of their fable. This approach is not only innovative, but it also fits within the age-old tradition of fables, where animals serve as metaphors to explore human behaviours and life lessons. GE3 wrote: “Un jour, ils virent arriver, au loin, Un groupe d’influenceurs, plein de prétentions. Ces animaux venus d’ailleurs, avec leurs mots promettaient richesse et gloire, un avenir meilleur. Le corbeau, curieux, s’approcha, Pour découvrir les secrets de ces invités-là.” [One day, they saw arriving, far away, a group of influencers, full of pretensions. These animals from afar, with their words promised wealth, and glory, a shining future. The crow, curious, approached, to uncover the secrets of these guests].

Similarly, subgroups of the control group developed excellent ideas in their writing works. For example, GT3 wrote :

Les expériences des aventuriers lui faisaient écho, Leur gloire et leur fortune semblaient si beaux. Mais un sage vieillard, aux cheveux blancs, Lui conta les misères que la mer cachait. Mon enfant, méfie-toi de ce voyage incertain, Les flots sont parfois cruels, sans pitié, sans lueur. Des destins emportés par les vagues amères, Le prix à payer pour des rêves éphémères.

The adventurers’ experiences resonated with him, Their glory and fortune seemed so grand. But an old wise man, with white hair, Told him of the miseries the sea concealed. “My child, beware of this uncertain journey, The waves are sometimes cruel, merciless, without light. Fates swept away by bitter waves, The price to pay for fleeting dreams.

Regarding the incorporation of morals in the written fables, the GT1, GE1, and GE3 groups successfully included it, while the GT2, GT3, and GE2 groups struggled to integrate it satisfactorily. In other words, two subgroups of the experimental group received (+) in this regard, whereas only one subgroup in the control group succeeded in incorporating moral in their fable. For example, GE3 from the experimental group wrote: “Qui trouvèrent le bonheur, l’essence du meilleur. Dans ce monde virtuel, où se mêlent les échos, L’authenticité et la vérité sont les plus belles.” [Who found happiness, the essence of the best. In this virtual world, where echoes mingle, authenticity and truth are the most beautiful]. In the control group only one subgroup GT1 achieved this aspect. GT1 wrote: “Ainsi on termine notre histoire, sur la fraude au Bac, Rappelons que la vraie réussite s’installe dans le cœur, Quand l'éthique et l’effort guident le meilleur”. [Thus we end our story, on fraud at the Bac, let us remember that true success settles in the heart when ethics and effort guide the best].

On the other hand, subgroups GT2, GT3, and GE2 encountered some challenges. Specifically, they did not introduce a moral in their narratives. Introducing morals requires the ability to synthesise the events of the story into a universal lesson, which can be a challenge for students who are not familiar with creative writing. Therefore, some students chose to leave the story open to the reader’s interpretation rather than proposing an explicit lesson. Overall, in terms of the structure of the fable, the subgroups of the experimental group generally achieved better performance than the subgroups of the control group. Specifically, in the experimental group, subgroups GE1 and GE3 received a positive sign (+) in all aspects of the fable’s structure, while only subgroup GE2 received two negative (-) signs and two positive (+) signs. However, all subgroups of the control group received at least one negative sign (-).

Aspect of content

The students in both the control group and the experimental group selected excellent topics for their fables related to important issues in the Algerian context. Table 3 shows the fable topics selected by each subgroup and presents some explanations about the meaning of these topics in the Algerian context.

All subgroups have received a positive (+) sign on the element of theme relevance, as all the selected topics are excellent and address important issues in the Algerian context. In terms of characters/ symbolic elements, all subgroups received a positive (+) sign because students in subgroups exhibited adeptness in selecting characters that represent various facets of Algerian life, showcasing a diversity of protagonists. Specifically, by incorporating a diverse array of characters, including clever animals like ravens, camels, goats, and foxes, as exemplified by GE3’s portrayal of the fox as “cunning and observant,” and pure-hearted humans such as kings, princesses, and curious pupils, as seen in GT1’s depiction of high school students planning to cheat on an exam, in which the storytellers showcased a profound grasp of human intricacies. All the fables written by the subgroups showcased a profound grasp of human complexities, skilfully crafting characters with multifaceted traits that vividly depicted the nuances of human nature. Consequently, each group rightfully deserved a plus (+) sign.

With respect to the element of Creativity, GT2, GE2, and GE3 exhibited exceptional creativity and a profound connection to Algerian culture. They accomplished this by crafting fables that were distinctly Algerian, drawing inspiration from their experiences, customs, landscapes, and values. These groups skillfully wove authentic tales deeply rooted in Algerian identity. Their talent lies in conveying pertinent messages through which Algerian readers can recognize themselves, reflecting their daily realities and challenges, such as Harrgaa, unemployment, and milk shortages. For example, GE3 creativity shines in their ability to transform a barren landscape into a canvas for profound reflection: “Dans ce beau désert, les véritables richesses étaient claires, L’amitié, l’honnêteté et la sagesse, des valeurs intemporelles et sincères”. [In this beautiful desert, the true riches were clear, Friendship, honesty, and wisdom, timeless and sincere values]. Through the simple yet evocative imagery of the desert, they convey a profound message about the enduring value of friendship, honesty, and wisdom, infusing the scene with timeless and sincere sentiments.

Overall, all subgroups demonstrated exemplary performance in the aspect of content, with each subgroup receiving a plus (+) sign for theme relevance and characters/ symbolic elements. However, the experimental subgroups excelled in creativity, with GE2 and GE3 receiving plus (+) signs in this aspect. In contrast, among the control group, only GT2 earned a plus (+) sign for creativity.

Aspect of language

Examining written fables of GT2, GT3, GE2, and GE3 subgroups showcases their mastery of verbal tenses, incorporating the imperfect, past simple, and present narrative forms (e.g., jumped, found, travelled, complemented). Moreover, these subgroups skilfully employed the indefinite pronoun “on” (e.g., we understood, we listened, we decided), creating an intriguing and somewhat enigmatic quality in their narratives that arouses readers’ curiosity. On the other hand, GT1 and GE1 displayed some errors in these linguistic aspects. Inappropriately used verb tenses at times resulted in inconsistencies and potential misunderstandings in their narratives. For example, GT1 made mistakes in “Petit à petit, la situation améliora, Le lait retrouvai une valeur sans éclat. Les fermiers souriaient, le cœur apaisé, Leur travail reconnu, leur courage compensé.” retrouvai should be changed to retrouva to match the subject “the milk” and to use the correct simple past tense. Une valeur sans éclat could be correct, but the expression is somewhat ambiguous; it could be clarified or rephrased depending on what exactly it means to regain its usual value. In addition, “la satituation améliora”[the situation improved], should be corrected to “la situation s’améliora” since it’s a reflexive verb, the student added the “s”.

Similarly, GE1 made mistakes in: “Sois unis, aimez notre terre, notre Algérie, Et préserver ensemble notre amour, notre vie.” [Be united, love our land, our Algeria, And preserve together our love, our life]. Such errors may have impeded the fluidity of reading and diverted attention from the intended messages. For example, 1) “Sois unis”: “Sois” is the form of the verb “être” (to be) in the singular, conjugated in the second person singular (tu). However, “unis” is an adjective in the plural form, which creates a mismatch. If the intention is to address a group, it would be more appropriate to say “Soyez unis,” using the verb “être” in the plural form of the imperative. 2) “préserver”, here, the verb “préserver” is in the infinitive, which is inconsistent with the other verbs in the imperative in the sentence. To maintain consistency and the imperative mood, the verb should be conjugated in the same mode and person: “préservons” if the intention is to include the speaker, or “préservez” to continue addressing the group.

Furthermore, the improper use of the indefinite pronoun on in their fables could have confused them. The incorrect application of this pronoun sometimes made it challenging to determine the subject of the action, diminishing the clarity and engagement of the narrative, as seen in the example from group GT1: “On doit lever la tête, ne pas s'égarer dans nos peurs, Le Bac est un défi, certes, mais on a la clé la meilleure.” [We must raise our heads, not get lost in our fears, The Bac is a challenge, certainly, but we have the best key]. This misuse may have hindered a clear understanding of the narrative and the conveyed messages. In general, the control group and the experimental group were comparable in their performance in the aspect of language. Two subgroups from the control group received a positive (+) sign, while one subgroup received a negative (-) sign. Similarly, two subgroups from the experimental group received a positive (+) sign, and one subgroup received a negative (-) sign.

Aspects of collaborative writing

Regarding the element of organisation/ management, subgroups of GT2, GT3, GE1, and GE3 demonstrated their ability to organise and manage their work efficiently and harmoniously during the collaborative writing process. They showcased cohesion and coordination, positively reflected in the quality of their fables. They effectively divided tasks, allowing each member to contribute meaningfully, and established a climate of trust and open communication, fostering a constructive exchange of ideas. However, GT1 and GE2 subgroups encountered difficulties in organising and managing their collaborative work. For example, GT1 did not establish a clear strategy to define specific roles for each member. This lack of clarity had a direct impact on the narrative coherence of their fable, resulting in sections that were contradictory and compromised the flow and understanding of the story.

The absence of defined roles and responsibilities occasionally led to misunderstandings and tensions within these groups, negatively impacting the quality and coherence of their fables. Consequently, in the element of Organization/Management, both the control group and the experimental group were equal, with each group receiving two positive (+) signs and one negative (-) sign. In terms of cohesion and interaction, the GT3, GE1, and GE3 groups exhibited visible cohesion. However, in GT1, GT2, and GE2 subgroups, some students did not actively participate in the group work. Therefore, the experimental subgroups outperformed the control group in this element. The experimental subgroups received two positive (+) signs and only one negative (-) sign, while the control subgroups received two negative (-) signs and only one positive (+) sign.

Analysis and results of written fables published on Moodle platform

After completing the evaluation of the written fables produced by subgroups, we invited the participants to revise their initial versions of the fables. It is essential to highlight that the experimental group received instructions regarding publishing the rewritten fables on the Moodle platform, but the control group did not receive these instructions. The subgroups’ writing works were evaluated based on the framework of Fabre (1990), as shown in Table 4 below. According to Fabre (1990), there are four main types of modifications applied during the revision or rewriting of a text: addition of words, phrases, or even entire paragraphs; replacement of one expression with another; movement of words; and deletion of text segments. The first two operations, namely addition and replacement, are considered explicit corrections that generate a metalinguistic discourse, while operations of deletion and movement are seen as adjustments modulated by a semiotic system that is part of the paralinguistic (Rey-Debove 1982).

The number of modifications—relocations, replacements, and additions—observed in the revised versions by the students demonstrates a significant evolution in their reflective approach to writing. This active revision process suggests that the group has not only become aware of the importance of rewriting but has also developed the ability to evaluate their own text critically. This reflective approach is crucial in learning to write, as it enables students to understand that the first draft is often just a rough outline that needs refinement and improvement. By engaging in ongoing dialogue with their text, students learn to identify weaknesses, ambiguities, or redundancies and consider clearer or more expressive alternatives. This ability to revise and improve their work reflects a maturity in writing skills, showing that they perceive writing not as a task to be accomplished linearly but as a creative and interactive process. It is essential to note that the study involved only six subgroups; therefore, the findings should be interpreted qualitatively and within the context of a case study approach. While numerical trends can be observed, these do not imply generalizability or statistical significance.

Regarding of additions, the experimental group made more additions (86, 91, 109) than the control group (60, 51, 48). Here are a few examples of the lexical additions we found most interesting in the work of the GE3 subgroup which in the first draft of their fable, they wrote:

Un jour, ils virent arriver, au loin, Un groupe d’influenceurs, plein de prétentions. Ces animaux venus d’ailleurs, avec leurs mots promettaient richesse, prospérité et gloire, un avenir. Le corbeau, curieux, s’approcha, Pour découvrir les secrets de ces invités-là.

One day, they saw arriving, far away, a group of influencers, full of pretensions. These animals from afar, with their words promised wealth, prosperity, and glory, a future. The crow, curious, approached, to uncover the secrets of these guests.

In the second version of the written fable, the students of the GE3 have made many additions to their fable, as in the following:

Un jour, ils virent arriver, au loin dans l’horizon, Un groupe d’influenceurs, plein de prétentions. Ces animaux venus d’ailleurs, avec leurs mots promettaient richesse, prospérité et gloire, un avenir étincelant. Le corbeau, curieux et malicieux, s’approcha, Pour découvrir les secrets de ces invités-là.

One day, they saw arriving, far away on the horizon, a group of influencers, full of pretensions. These animals from afar, with their words promised wealth, prosperity, and glory, a shining future. The crow, curious and mischievous, approached, to uncover the secrets of these guests.

In the second version, several additions were made in the second version of the fable to enrich the description and narration. First, the phrase “in the horizon” was added to provide more depth to the scene where the influencers appear. Secondly, they expanded the promise of the influencers by adding “a dazzling future” to the existing promises of “wealth, prosperity, and glory”, thereby intensifying the allure and mystery surrounding these characters. Lastly, the character of the crow is deepened with the addition of the adjective “malicious” next to “curious”, offering an additional nuance to his behaviour and potential interaction with the influencers. These modifications bring a richer and more detailed dimension to the narrative. Regarding deletions, students in the experimental group generally made fewer deletions (43, 23, 45) than the control group (25, 34, 39). For example, to give their fable more sonority, the GE1 group made some deletions. In the first draft they wrote : “La gazelle belle et pleine de talents et de courage d’ardeur, Frappée par le chômage, sa vie en pâleur. Elle espérait un emploi, un moyen de s'épanouir, Mais les portes restaient fermées, elle était fort désespérée.” [The gazelle beautiful and full of talents and courage of ardour, struck by unemployment, her life in pallor. She hoped for a job, a way to blossom, but the doors remained closed; she was desperate].

In the second version, they made some deletions as follow: “La gazelle belle et pleine de talents et d’ardeur, Frappée par le chômage. Elle espérait un emploi, un moyen de s'épanouir, Mais les portes restaient fermées, elle était fort désespérée.” [The gazelle beautiful and full of talents and of ardour, struck by unemployment. She hoped for a job, a way to blossom, but the doors remained closed; she was desperate]. Students in GE1 chose to delete certain words to improve the sonority of their fable. The specific removal of words such as “of courage” shows an effort to avoid redundancies. By deleting “of courage”, the students may have judged that the mention of the gazelle’s talents and ardor was sufficient to convey the idea of her determination and ability to face challenges, making the specific addition of courage superfluous. The expression “her life without pallor” was also deleted in the revised version. This deletion is particularly interesting because it changes the way the gazelle’s character is presented. Initially, the phrase “her life in pallor” suggests a life devoid of vitality or color, which visually reinforces the impact of unemployment on the gazelle’s life. However, deleting this part of the sentence may indicate a desire to focus the message on the direct emotional aspect and the critical situation of the gazelle (her despair due to unemployment), rather than on the metaphorical description of her state of life.

With respect to moving, the moving processes in all subgroups were fewer compared to processes in other aspects. Students made adjustments by moving some content during the revision process to enhance coherence, clarity, and effectiveness. For example, GE1 wrote in the first draft: “Convoqua une assemblée, une action sans fin, Le lion, déterminé à changer le destin,” [Convened an assembly, endless action, the lion, determined to change destiny]. However, in the second version, they moved the phrase “Convoqua une assemblée, une action sans fin” to the beginning of the sentence, imposing urgency and drawing the reader’s attention to the meeting of the animals and their determination to find solutions. This shift would adjust the rhythm and tone of the narrative, making the fable more appealing to the reader. Furthermore, GE3 in their first version wrote : “Dominait tous les autres, avec avidité, Le lion, roi des réseaux, imposant sa fierté. “ [Dominated all the others, with greed, the lion, king of the networks, imposing his pride]. However, in the second version, they moved the expression “Dominated all the others, with greed” to the beginning of the sentence, highlighting the arrogant attitude of the lion, who greatly desired to reign over the other influencers. It is important to note that the findings are based on a small sample size (n = 6), which limits the ability to generalize the results to other contexts or populations.

Discussion

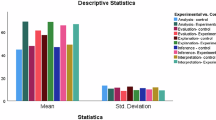

The results, in the first round of writing before publishing the written fables on the Moodle platform, indicate that the performance of the experimental group that used Framapad in their fables writing was better than that of the control group that wrote the fables through the traditional way, face-to-face. The evaluation of subgroups’ writing in the first round of writing before publishing is based on four aspects (i.e., the fable structure, content, language, and collaborative writing). The experimental group received better results in aspects of the fable structure, content, and collaborative writing, while the results were equal among the two groups in the aspect of language. In the second round of writing for publishing on the Moodle platform, the experimental group results were also better than the control group in the second round of subgroups’ writing, which was conducted in order to be published on the Moodle platform. The evaluation of subgroups’ writings is based on four aspects: Additions, deletions, replacement, and moving.

These results suggest that the use of Web 2.0 applications facilitates interaction and collaboration among students, leading to improved performance in L2 collaborative writing. Notably, online interaction on Framapad facilitated real-time collaboration, enabling students to revise and edit their fables seamlessly. The results of this study align with previous studies’ results (e.g., Linh 2021; Rahimi and Fathi 2022; Zhang and Zou 2022; Ziyad 2016) that explored the impact of Web 2.0 applications on the performance of collaborative writing among L2 learners.

In discussing these results within the framework of sociocultural theory (Vygotsky 1978), particularly focusing on the concepts of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and scaffolding, it becomes evident that the online collaborative writing environment provided students with opportunities for collective problem-solving, negotiation of meaning, and scaffolding of knowledge. Vygotsky (1978) emphasises the role of social interaction and collaborative activities in cognitive development, highlighting how individuals learn and develop within their social and cultural contexts through interactions with more knowledgeable peers or adults. In the context of this study, the collaborative writing process enabled students to co-construct knowledge, share perspectives, and collectively create meaningful texts, aligning with the notion of learning within the ZPD (Vygotsky 1978). The application of scaffolding facilitated the transfer of knowledge and skills from more proficient peers to those with less expertise.

Furthermore, the online applications in this study facilitated collaboration by providing students with a shared space to write, edit, and exchange feedback. Framapad enabled them to work together in real-time, making immediate edits and discussing changes as they wrote. Meanwhile, Moodle provided a structured platform where students could review each other’s work, give feedback, and refine their writing based on both peer and instructor suggestions. These features encouraged more active participation and helped students develop their writing skills through meaningful collaboration.

The analysis of fable structure reveals that both the control and experimental groups demonstrated a solid understanding of fable elements, including introduction, plot development, and morals. However, the experimental group generally exhibited better performance, particularly in integrating the plot and incorporating morals. This suggests that the online collaborative writing environment fostered richer discussions and deeper engagement with the thematic and moral aspects of fable writing, leading to more cohesive and nuanced narratives. Moreover, the selection of topics related to pressing societal issues in the Algerian context reflects the students’ engagement with real-world concerns and their ability to connect personal experiences with broader social themes. This aligns with the acknowledgement of the importance of cultural tools and artefacts in mediating cognitive processes (Vygotsky 1978). Students made their writing more relatable and realistic by using familiar cultural topics and discussing current issues in their society. This helped them connect their stories to the world around them.

The analysis of language use and collaborative writing strategies highlights the importance of effective communication and coordination in collaborative writing tasks. The experimental group demonstrated greater cohesion and organization in their collaborative efforts, resulting in more polished and coherent fables. This underscores the role of the digital environment in enhancing social interaction, scaffolding writing skills, and fostering collaborative competence.

The difference between the two groups can largely be attributed to the support provided by Framapad and Moodle. Framapad enabled students to collaborate in real-time, share ideas instantly, and refine their writing together, making the process more interactive than traditional methods. Moodle further enhanced the experience by organizing peer and instructor feedback in a structured way, enabling students to track changes and improve their work more effectively. These digital tools also kept students more engaged and accountable, fostering deeper collaboration and leading to stronger, more creative writing in the experimental group. The experimental group demonstrated relatively higher creativity in their fables, particularly in the originality of themes, symbolic character choices, and cultural relevance, compared to the control group.

Overall, the results suggest that the writing processor Framapad and the Moodle platform can serve as valuable tools for promoting meaningful engagement, peer interaction, and collaborative learning in the context of fable writing. By leveraging the affordances of digital technologies to facilitate communication and collaboration, educators can create rich and dynamic learning environments that support both cognitive and socio-emotional development. Moreover, the study underscores the importance of applying sociocultural theories when designing and implementing collaborative writing activities to enhance student learning and engagement.

These findings also resonate with previous research on online collaborative writing using digital tools. For example, Rahimi and Fathi (2022) found that wiki-mediated collaborative writing enhanced students’ content clarity and language accuracy, which aligns with our observation of improved narrative development and reduced deletion rates in the experimental group. Similarly, Linh (2021) reported that Vietnamese L2 learners exhibited positive attitudes and improved performance when using Framapad—findings that are mirrored in our participants’ creative engagement with culturally relevant topics. Wang (2024) also emphasized that digital tools foster sociocognitive learning communities, where learners co-construct knowledge—an outcome clearly reflected in our experimental group’s superior performance in the collaborative aspects of writing. Ziyad (2016) likewise demonstrated how Moodle enhanced motivation and feedback exchange, supporting our findings regarding the structured and reflective nature of the revision process facilitated by Moodle. These convergences reinforce the argument that digital scaffolding tools like Framapad and Moodle are not only pedagogically aligned with sociocultural principles but also empirically validated as effective instruments for enhancing collaborative writing practices in L2 contexts.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that Web 2.0 tools have a positive impact on knowledge exchange and sharing, while also reinforcing collaboration. Collaborative tools played a crucial role in fostering learner engagement and dedication, thereby facilitating the creation of new knowledge. Synchronous discussions and peer-to-peer interaction notably improved the quality of written fables and enhanced participants’ skills development. The online digital environment provided by Framapad proved to be advantageous for students, who found it easier to express themselves and actively engage in collaborative writing. The absence of face-to-face pressure empowered these students to express themselves more freely, participate actively, and take initiative. Framapad, being a powerful and adaptable tool, offers an environment conducive to collaboration, enabling students to harness the benefits of interaction while enjoying the flexibility of online collaboration.

This study implies that integrating modern technological tools such as Framapad and Moodle into language education can enhance collaborative writing practices among L2 students in Algerian universities. The findings suggest that utilizing these tools can lead to improved narrative structuring, enhanced creativity in addressing local issues, and more effective teamwork among students. This highlights the potential benefits of integrating technology into L2 learning environments to enhance writing skills and foster collaboration.

Future research could investigate how digital scaffolding influences writing skills over time, its effectiveness in various learning settings, and the challenges students encounter when utilising these tools. Comparing Framapad and Moodle with other platforms could reveal what works best for collaborative writing. Additionally, examining how teachers guide and support students in digital collaboration can provide valuable insights for enhancing teaching strategies.

Data availability

All data analyzed are fully included in the paper.

References

Abusalim N, Rayyan M, Alshanmy S, Alghazo SM, Al Salem MN (2024) Revolutionizing pedagogy: the influence of H5P (HTML5 Package) tools on student academic achievement and self-efficacy. Int J Inf Educ Technol 14(8):1090–1098

Abushihab I (2020) The effect of critical rhetoric in teaching English as a foreign language. Theory Pract Lang Stud 10(7):744–748

Algazo M (2023) Functions of L1 use in the L2 classes: Jordanian EFL teachers’ perspectives. World J Engl Lang 13(1):1–8

Alghazo SM, Jarrah M, Al Salem MN (2023) The efficacy of the type of instruction on second language pronunciation acquisition. Front Educ 8(1):1182285. Article

Al-Shahwan R (2024) The attitudes of students at the translation Department at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan towards using translation from English language into Arabic language by the instructors as a medium of instruction in translation courses. Al-Zaytoonah Univ Jordan J Hum Soc Stud 5(1):176–190

Alzobidy S, Al-qadi MJ, Belhassen SB, Naser IMM, Al Maaytah SA (2024) The effect of multi-media usage in cognitive demands for teaching EFL among Jordanian secondary school learners. World J Engl Lang 14(3):471–481

Aydin Z, Yildiz S (2014) Use of wikis to promote collaborative EFL writing. Lang Learn Technol 18(1):160–180

Baudrit A (2007) Apprentissage coopératif/Apprentissage collaboratif: d’un comparatisme conventionnel à un comparatisme critique. Les Sciences de l’éducation-Pour l’Ère nouvelle 40(1):115–136

Berkowitz H, Brakel F, Bussy-Socrate H, Carton S, Glaser A, Irrmann O, De Vaujany FX (2023) Organizing commons in time and space with Framapads: feedback from an open community. J Openness Commons Organ 2(1):6–11

Bouchefra M (2016) Computer assisted language learning at Djilali Liabes University: attitudes and hindrances. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sidi Bel Abbes

Boussebha N (2023) Educational technology to enhance EFL learners’ research skills: the case of third-year students at Naama University Center, Algeria. Arab World Engl J 1:99–113

Brandl K (2005) Review of are you ready to” Moodle”? Lang Learn Technol 9(2):16–23

Brodahl C, Hadjerrouit S, Hansen NK (2011) Collaborative writing with Web 2.0 technologies: education students’ perceptions. J Inf Technol Educ Innov Pract 10:73–103

El-Maghraby AL (2021) Investigating the effectiveness of moodle based blended learning in developing writing skills for university students. J Res Curric Instr Educ Technol 7(1):115–140

Eskandari M, Soleimani H (2016) The effect of collaborative discovery learning using MOODLE on the learning of conditional sentences by Iranian EFL learners. Theory Pract Lang Stud 6(1):153–163

Fabre C (1990) Les brouillons d'écoliers ou l’entrée dans l'écriture. Librairie de l’Université

Farrah MA (2015) Online collaborative writing: students’ perception. J Creat Pract Lang Learn Teach 3(2):17–32

Gamage SH, Ayres JR, Behrend MB (2022) A systematic review on trends in using Moodle for teaching and learning. Int J STEM Educ 9(1):1–24

Garrison DR, Anderson T (2003) E-learning in the 21st century: a framework for research and practice. Routledge

Gulbinskienė D, Masoodi M, Šliogerienė J (2017) Moodle as virtual learning environment in developing language skills, fostering metacognitive awareness and promoting learner autonomy. Pedagogika/Pedagogy 127(3):176–185

Hadjerrouit S (2011) A collaborative writing approach to Wikis: design, implementation, and evaluation. Issues Inf Sci Inf Technol 8:431–449

Hodges G (2002) Learning through collaborative writing. Reading 36(1):4–10

Kargiban ZA, Kaffash HR (2011) The effect of e-learning on foreign language students using the student’s attitude. Middle East J Sci Res 10(3):398–402

Kessler G, Bikowski D, Boggs J (2012) Collaborative writing among second language learners in academic web-based projects. Lang Learn Technol 16(1):91–109

Lee L (2010) Exploring wiki-mediated collaborative writing: a case study in an elementary Spanish course. Calico J 27(2):260–276

Linh MLTT (2021) Online collaborative writing through Framapad: students’ perspectives. In: Proceedings of the international virtual conference 2021: technologies and language education. UEH University, pp 104–117

Lowry PB, Curtis A, Lowry MR (2004) Building a taxonomy and nomenclature of collaborative writing to improve interdisciplinary research and practice. J Bus Commun 41(1):66–99

Mak B, Coniam D (2008) Using wikis to enhance and develop writing skills among secondary school students in Hong Kong. System 36(3):437–455

Nevid JS, Pastva A, McClelland N (2012) Writing-to-learn assignments in introductory psychology: Is there a learning benefit? Teach Psychol 39(4):272–275

O’Reilly T (2007) What is Web 2.0: design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Commun Strateg 65(1):17–37

Prasetya RE (2021) Effectiveness of teaching english for specific purposes in LMS moodle: lecturers’ perspective. J Engl Lang Teach Linguist 6(1):93–109

Rahimi M, Fathi J (2022) Exploring the impact of wiki-mediated collaborative writing on EFL students’ writing performance, writing self-regulation, and writing self-efficacy: a mixed methods study. Comput Assist Lang Learn 35(9):2627–2674

Rayyan M, Abusalim N, Alshanmy S, Abu Awwad F, Alghazo SM (2024) Enhancing academic performance through blended learning: a study on the relationship between self-efficacy and student success. Int J Interact Mob Technol 18(19):52–67

Rey-Debove J (1982) Pour une lecture de la rature. In: Fuchs C, Grésillon A (eds) La genèse du texte—Les modèles linguistiques. Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, pp 103–127

Rezeki YS (2016) Indonesian english-as-A-foreign-language (EFL) learners’ experiences in collaborative writing. University of Rochester

Shadiev R, Hwang WY, Huang YM (2017) Review of research on mobile language learning in authentic environments. Comput Assist Lang Learn 30(3-4):284–303

Storch N (2011) Collaborative writing in L2 contexts: processes, outcomes, and future directions. Annu Rev Appl Linguist 31:275–288

Storch N (2019) Collaborative writing. Lang Teach 52(1):40–59

Swaie M, Algazo M (2023) Assessment purposes and methods used by EFL teachers in secondary schools in Jordan. Front Educ 8:1–10

Swain M (2010) “Talking-it-through”: languaging as a source of learning. In: Batstone R (ed) Sociocognitive perspectives on language use/learning. Oxford University Press, pp 112–130

Talib T, Cheung YL (2017) Collaborative writing in classroom instruction: a synthesis of recent research. Engl Teach 46(2):43–57

Tang J (2013) The research on blended learning of ESL based on Moodle platform. Stud Lit Lang 6(2):30–34

Tomo T, Widodo JP, Yappi SN (2022) The effect of a Moodle-based LMS in “Article Writing for Journal” subject for post graduate students. Bp Int Res Crit Inst J Humanit Soc Sci 5(1):5448–5456

Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press

Wang S (2024) The dimensions and dynamism of group engagement in computer-mediated collaborative writing in EFL classes. SAGE Open 14(1):1–14

Wass R, Harland T, Mercer A (2011) Scaffolding critical thinking in the zone of proximal development. High Educ Res Dev 30(3):317–328

Wilson K, Devereux L (2014) Scaffolding theory: high challenge, high support in academic language and learning (ALL) contexts. J Acad Lang Learn 8(3):A91–A100

Woodrich MP, Fan Y (2017) Google Docs as a tool for collaborative writing in the middle school classroom. J Inf Technol Educ Res 16:391–410

Wu WS, Hua C (2008) The application of Moodle on an EFL collegiate writing environment. J Educ Foreign Lang Lit 7(1):45–56

Zhang R, Zou D (2022) Types, features, and effectiveness of technologies in collaborative writing for second language learning. Comput Assist Lang Learn 35(9):2391–2422

Ziyad H (2016) Technology-mediated ELT writing: acceptance and engagement in an online Moodle course. Contemp Educ Technol 7(4):314–330

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Souad Benabbes (first author) conceptualized and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, wrote the “Methodology” section, and drafted the main findings. Muath A. Algazo (second author) wrote the “Literature review” and “Discussion” sections and assisted with proofreading. Sharif M. Alghazo (third author) wrote the “Abstract”, “Introduction”, and “Conclusion”, and contributed to editing and final proofreading of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria. The approval number is EC-UOEB/23-092, granted on March 5, 2023. All research activities involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The scope of the approval included voluntary participation of university students in a writing-focused educational intervention, the use of anonymized written texts, and follow-up analysis for research purposes.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Consent was obtained in March 2023, after ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee, using a standard written form. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any point without penalty. The consent form also specified that the data collected (written texts and anonymized feedback) would be used solely for research purposes and publication. All participants were assured that their identities would remain confidential and that their responses would be anonymized in any dissemination of results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benabbes, S., Algazo, M.A. & Alghazo, S.M. Exploring the impact of digital scaffolding on collaborative writing practices. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05606-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05606-0