Abstract

In practice, the implementation of a circular economy often encounters market failures. Can government intervention, as proposed in Enns’ theory, help mitigate these failures? To address this question, this study examines the relationship between green finance and the circular economy using data from 279 Chinese cities between 2006 and 2021. The findings reveal that green finance significantly promotes the development of the circular economy. Second, green finance fosters circular economy growth primarily by increasing social lending and driving innovation. Third, the impact of green finance on the circular economy is more pronounced under stringent environmental regulations, heightened public awareness of environmental issues, and lower pollution levels. Fourth, green finance exhibits positive spatial effects, meaning it benefits both local and neighboring cities’ circular economies. Finally, the green finance-driven circular economy contributes to carbon neutrality. This study evaluates the effectiveness of green finance and offers policy recommendations for advancing green finance and circular economy development in China and other developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 200 years, economic development has followed a “develop first, regulate later” approach, relying on excessive resource extraction and ongoing environmental degradation (Jovane et al., 2008). While this strategy has significantly boosted productivity, driving global economic prosperity and social progress, it has also left profound ecological and social challenges. According to the United Nations Environment Programme’s Global Resources Outlook 2024, the extraction and processing of material resources account for over 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions and 40% of air pollution-related health impacts. Biomass extraction and processing contribute to one-third of greenhouse gas emissions, while the combined extraction and processing of fossil fuels, metals, and non-metallic minerals make up 35% of global emissions. Some scholars have called for a shift away from the traditional linear economy of “resource extraction–product consumption–pollution emissions” and toward a model that balances development and environmental management within finite resource constraints (Chen, 2022). This approach, known as the circular economy, follows the principles of Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle (3R), transforming economic activities into a feedback loop of “resource extraction–product use–resource regeneration” (Chen et al., 2025).

However, implementing a circular economy is challenging and often met with obstacles. Market failures or inefficiencies hinder its progress, leading to difficulties in securing financing, high upfront investment costs, and the low prices of raw materials (Grafström and Aasma, 2021). At its core, these challenges stem from market failure theory. Relying solely on market mechanisms often fails to achieve optimal resource allocation. Therefore, Keynesian economic principles advocate for government intervention (Canova, 2009), which, when combined with the resource-based view (Wernerfelt, 1984), can help maximize policy effectiveness. In response, countries worldwide are exploring effective intervention strategies. Green finance, which prioritizes sustainable development and allocates capital to environmentally friendly initiatives, has emerged as a key financial instrument for advancing the circular economy (Kumar et al., 2024). On the hand, green finance directs targeted investments into the circular economy. For instance, the European Investment Bank has launched a €10 billion plan over five years to support circular economy initiatives through loans, equity investments, guarantees, and advisory services (Dewick et al., 2020). On the other hand, green finance fosters technological advancements that support circular economy models (Agrawal et al., 2024). By enabling more efficient resource allocation, it helps organizations invest in research and development, ensuring economic viability while minimizing resource waste and environmental impact (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018).

Globally, high-income transitioning countries such as those in Europe, North America, Japan, and South Korea have taken the lead in green finance policy design. These nations benefit from well-established market and regulatory mechanisms, and their circular economies are characterized by significant reductions in material consumption while maintaining public well-being. This suggests that the link between green finance and the circular economy is stronger in high-income transitioning countries. In contrast, middle-income developing countries like China, which are still in a phase of stable material consumption, face greater challenges in transitioning to a circular economy. Taking China, the largest emerging economy, as an example, the country is projected to face coal and oil shortages by the latter half of the 21st century (Singh, 1999). The dual pressures of sustaining rapid economic growth while dealing with impending resource depletion make the transition to a circular economy particularly challenging. Since the beginning of the 21st century, China’s financial system has undergone significant reforms (Allen et al., 2012). However, emerging financial instruments such as green finance still face substantial challenges, including market mechanism deficiencies, regulatory misalignment between central and local governments, interdepartmental coordination issues, and institutional inefficiencies (Heilmann and Schmidt, 2014). As a result, questions arise as to whether China’s green finance can drive circular economy development as effectively as in developed countries. To address this issue, this study aims to explore the relationship between green finance and the circular economy, contributing to the existing literature by filling this research gap.

As noted by Muganyi et al. (2021), green finance faces systemic risks that complicate its overall effectiveness, particularly in relation to the circular economy. To assess whether green finance encounters similar challenges in advancing China’s circular economy, this study raises the following research questions: (1) Can green finance promote the development of the circular economy in China? (2) If so, what are the potential mechanisms through which green finance exerts its influence? (3) Given the mobility of resources, does green finance impact the circular economy of neighboring regions? (4) From the perspective of institutional theory, how does the heterogeneity of green finance—shaped by government, market, and public—affect the circular economy? Specifically, do external pressures such as environmental regulations, regional pollution levels, and public environmental awareness moderate its impact? (5) What are the key characteristics of a circular economy driven by green finance? Addressing these questions enhances our understanding of the effectiveness of green finance. Moreover, the empirical findings of this study not only apply to China but also offer insights for other countries seeking to develop a circular economy.

This study contributes to the literature on green finance in four key ways. First, we provide the first systematic analysis of the relationship between green finance and the circular economy in the Chinese context. Previous studies have primarily focused on innovation, green economic growth, and pollution control (Huang et al., 2022; Iqbal et al., 2021), with relatively little attention given to the circular economy. Compared to other green development indicators, the circular economy achieves higher economic benefits while minimizing resource consumption and byproduct emissions (Sehnem et al., 2019). Therefore, examining the relationship between green finance and the circular economy is essential to enhancing our understanding of green finance.

Second, this study identifies the potential pathways through which green finance influences the circular economy. Currently, circular economy projects in China face significant challenges, including high financing costs and a lack of technological support (Rizos et al., 2016; Tleuken et al., 2022). Tian (2018) highlights that given the high initial costs, long payback periods, and inherent uncertainties of circular economy projects, market-oriented green finance is essential to their success. Therefore, this study focuses on two key mechanisms: social lending and green technological innovation. The former provides targeted financial support for circular economy initiatives, while the latter helps overcome technological barriers and fosters circular economy. This analysis offers a new perspective for policymakers seeking to enhance the role of green finance in promoting the circular economy.

Third, this study examines the spatial effects of green finance. In market mechanisms, market elements flow autonomously and orderly, either clustering or dispersing (Johnson and Lundvall, 1994). For example, green finance in China is showing regional clustering characteristics, with its influence spreading to nearby areas (Huang et al., 2022). This raises the question of whether this distribution of elements affects the development of the circular economy in neighboring cities. To address this, the study uses spatial econometric models to provide new insights for regional financial sector coordination and collaboration. Furthermore, external pressures can influence the relationship between green finance and the circular economy. This study, drawing on institutional theory, explores the heterogeneity of green finance, considering whether factors such as environmental regulations, regional pollution levels, and public environmental awareness affect the impact of green finance on the circular economy.

Finally, we analyze whether the circular economy, driven by green finance, can contribute to achieving sustainable development goals. In contrast to the traditional, resource-intensive economic development model that leads to deteriorating living conditions (Basten and Jiang, 2015; Liu and Lin, 2019), the circular economy itself has dual aspects. On the positive side, the circular economy can help achieve carbon neutrality. However, on the darker side, the development of the circular economy involves significant cost investments (Rizos et al., 2015). To further explore the dual nature of the circular economy, we analyze, from both the benefit and cost perspectives, whether the green finance-driven circular economy can achieve carbon neutrality while controlling costs.

Background and hypothesis development

Literature review

The defining feature of green finance is its focus on environmental factors within financial activities. Green finance includes various financial instruments such as green credit, green bonds, and green funds, aimed at supporting environmental protection projects and the development of a low-carbon economy. Countries worldwide have made significant efforts to promote the development of green finance. For example, the European Investment Bank has led numerous green finance projects, including those in wind energy, solar energy, and energy efficiency. Countries such as the UK, France, and Germany have enacted stringent environmental regulations to encourage financial institutions to invest in sustainable and eco-friendly projects (Park and Kim, 2020; Bourcet and Bovari, 2020; Kalkbrenner and Roosen, 2016). Despite fluctuating government support, the private sector in the United States is highly active in green finance, involving investment companies and funds (Wang, 2017). It is evident that green finance serves as both a market mechanism and a manifestation of institutional frameworks.

The development of green finance in China began later, with the earliest mention of it in the 2007 “Opinions on Implementing Environmental Policy Regulations.” It was not until 2016 that green finance development was formally promoted through official documents. According to official data, by 2021, the value of China’s green bond market reached $163 billion (1.1 trillion RMB), and the balance of green loans amounted to $2.4 trillion (16 trillion RMB). It is clear that green finance is playing an increasingly important role in the national economy. Many scholars have pointed out the significant role of green finance in micro-level aspects, such as stakeholder benefits for enterprises (Tang and Zhang, 2020), energy efficiency (Jin et al., 2021), and green performance (Xu et al., 2020); At the macro level, it influences carbon dioxide emissions (Meo and Abd Karim, 2022), green innovation (Huang et al., 2022), climate change governance (Zhang et al., 2022), and foreign direct investment (Chen et al., 2021); However, there is limited research addressing the circular economy.

Figure 1 illustrates the spatiotemporal distribution of green finance based on the project’s database. The darker the color, the higher the green finance index. From a temporal perspective, in 2006, green finance was relatively scarce and concentrated in the eastern coastal regions. Most areas showed a light blue color, indicating limited green finance activity. Subsequently, green finance activities saw a notable increase, particularly in the eastern coastal regions. By 2021, green finance had significantly expanded, with an increasing number of cities and provincial capitals participating in green finance activities. From a spatial perspective, the eastern coastal regions have consistently been the stronghold of green finance. Cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen serve as the hubs of green finance, likely due to their economic development, infrastructure, and government policies that support green investments. In contrast, green finance is weaker in the western and northern regions, reflecting a lower concentration of activities and the need for more infrastructure and policy support. Overall, as time progressed, green finance noticeably increased in central and some western regions. However, the eastern regions still dominate, with Beijing, Guangdong, and Zhejiang continuing to lead the country in green finance investments.

The concept of the circular economy first appeared in the research of Pearce and Turner (1989), who described the linear mechanism of the contemporary economic system and depicted the Earth as a closed-loop system, inferring that the economy and the environment should coexist in balance. Stahel and Reday-Mulvey (1976), based on industrial ecology, described certain features of the circular economy, including waste prevention, creating regional employment, resource efficiency, and the dematerialization of industrial economies. Subsequently, the concept of the circular economy has extended to various sectors, including circular and performance economy (Stahel, 2010), industrial ecology (Graedel, 1996), and blue economy (Pauli, 2010). The circular economy is seen as a perfect cycle that promotes slow material flows, facilitates the transition from consumer to user, and decouples resource use, environmental impact, and economic growth (Lazarevic and Valve, 2017). In addition to studying the concept of circular economy, some scholars have attempted to quantify circular economy systems (García-Barragán et al., 2019; Moraga et al., 2019) and further explore its drivers, including innovation (Chen et al., 2025), supply chain management (De Angelis et al., 2018), Industry 4.0 technologies, and green logistics (Seroka-Stolka and Ociepa-Kubicka, 2019). However, few scholars have focused on the impact of green finance on the circular economy.

Table 1 illustrates the relationship between green finance and green development. Most studies primarily focus on carbon footprint, energy efficiency, green innovation, and green production efficiency, with little attention given to the circular economy. While the circular economy overlaps with these factors, it emphasizes the central role of economic actors, with the aim of achieving both economic and environmental benefits, while adding social benefits as a secondary goal. It follows principles of resource reduction, reuse, and recycling to promote coordinated environmental and economic development with limited resources (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017).

Theoretical analysis: circular economy and Keynesian school

The circular economy is often seen as an innovative model for economic development, but it is not a new idea. It is based on scientific and semi-scientific concepts, including ecological economics, industrial economics, and eco-efficiency (Korhonen et al., 2018). The concept of the circular economy is diverse, but it is generally understood in academia as a departure from the traditional linear production model, aimed at extending the lifecycle of resources through a cyclical approach (Blomsma and Brennan, 2017). Specifically, according to the 3R principles of Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle, the goal is to retain resource value as much as possible throughout the various economic activity cycles (Blomsma and Brennan, 2017). Later scholars expanded on the 3R concept, introducing the 4R (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Recover) and 6R (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Recovery, Remanufacturing, Redesign) principles. Regardless of the principle, the early stages of circular economy transformation increase investment uncertainty (Garcés-Ayerbe et al., 2019), particularly in situations where market mechanisms are imperfect or absent.

Clearly, market failures are a key barrier to the development of the circular economy. So, why do market failures occur in the circular economy? There are three main reasons: first, financing difficulties in the circular economy model. Waste recycling projects may require technological investment, supply chain development, and recycling standards, which stakeholders often find difficult to bear due to the associated risks (Tura et al., 2019). Second, inaccurate upfront investment costs. The circular economy model relies heavily on specific infrastructure and technological investments, such as waste treatment facilities, remanufacturing equipment, and resource recycling systems (Ghisellini et al., 2016). Traditional financial mechanisms may not be able to allocate resources accurately to circular economy projects. Third, low raw material prices. Fossil fuels and mineral resources, commonly used in traditional production models, have low extraction costs. This low price reduces the competitiveness of recycled materials and circular models (Kinnunen and Kaksonen, 2019), hindering the development of the circular economy. At this point, intervention by the government or financial institutions is crucial. According to Keynesian theory, when the market cannot self-adjust, government intervention in economic and social activities is necessary (Pasinetti, 2005).

The Keynesian school emphasizes the decisive influence of future uncertainty on people’s economic behavior (Ferrari-Filho and Conceição, 2005). Therefore, the government needs to stabilize market expectations through commitment mechanisms, combined with public expenditure, to create a dual mechanism of “Pigovian tax + Keynesian fiscal stimulus.” This would correct the externalities of the circular economy and encourage forward-looking investments to guide technological transformation and break free from technological lock-in effects. Additionally, drawing on the resource-based view, which suggests that rare resources are key to an organization’s sustainable development (Mahoney and Pandian, 1992), we consider how government guidance in directing specific resources can more effectively support the development of the circular economy. First, the technologies relied upon by the circular economy often have high research and development costs and path dependency, creating a “scarcity window” for technological resources. This requires the government to guide rare resources into targeted investments (Rodríguez-Pose and Wilkie, 2019). Second, the benefits of resource conservation and pollution reduction in the circular economy are public in nature, making it difficult to internalize resource value through the market. Only by the government integrating dispersed public resources (Nogueira et al., 2019) can a stable resource supply be provided for circular economy development. Third, through the government’s strong organizational capabilities, resources can be effectively allocated (Rankonyana, 2015), maximizing the advancement of circular economy development.

Given the financing constraints, technological dependence, and market barriers faced by the development of the circular economy, among various government tools, financial instruments are seen as targeted means to promote circular economy development (Kumar et al., 2024). Unlike traditional finance, green finance provided by financial institutions is highly targeted. First, green finance can drive targeted green elements into circular economy projects (Bracking and Leffel, 2021). Second, financial institutions can reduce uncertainty and potential risks in circular economy projects through risk-sharing (Alem and Townsend, 2014). Finally, green finance is specifically used to support technological research and development for circular economy growth, breaking free from technological path dependence (Negi et al., 2025). Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, the government has a reason to adopt green finance to promote the development of the circular economy.

Green finance and circular economy

In addition to the theoretical analysis, this study explains the relationship between green finance and the circular economy from the perspective of the 3R principles of the circular economy. First, in terms of reduction, green finance supports businesses and projects in reducing the use of raw materials and environmental pollution by promoting innovation and optimizing production processes, as well as improving energy efficiency (Sun and Chen, 2022). Lv et al. (2023) point out that green finance encourages organizations to adopt low-carbon, energy-saving production methods through financial support, thereby reducing resource waste from the source. Green finance can also promote the development of environmental protection industries by investing in areas such as clean production technologies (Koval et al., 2022), green buildings (Debrah et al., 2022), and green transportation (Haseli et al., 2024), thereby reducing negative environmental impacts.

Second, in terms of reuse, green finance can facilitate resource reutilization through innovative business models, such as product repair and second-hand markets (Parajuly et al., 2024). Furthermore, green finance can support the development of new product design concepts (Agrawal et al., 2024), enabling products to be disassembled, repaired, or directly repurposed after the end of their lifecycle. Finally, in terms of recycling, green finance provides financing for the recycling industry (Campiglio, 2016), supports the construction of recycling technologies and facilities, and promotes the effective recycling and reprocessing of waste (Miao, 2019). Especially in high-energy-consuming industries, such as electronic waste recycling and battery recycling, green finance can encourage organizations to adopt advanced recycling technologies (Agrawal et al., 2024), reducing resource waste and environmental pollution. Overall, green finance complements the 3R principles of the circular economy, driving its transformation. Based on this, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: There is a positive correlation between green finance and the circular economy.

The mediating role of social loans and green technological innovation

In addition to explaining the main effects of green finance on the circular economy, this study also elaborates on the potential pathways of green finance. First, circular economy projects often face difficulties in financing, long durations, and uncertainties (De Jesus and Mendonça, 2018; Masi et al., 2018). Green finance can provide financial support and reduce financing costs (Mohd and Kaushal, 2018), offering funding for environmental protection and sustainable development projects, including green bonds, green loans, and other financial instruments to promote the development of the circular economy. Specifically, green finance directs social capital into green projects (Campiglio, 2016), facilitates information exchange between enterprises and financial institutions, and reduces resource allocation costs (Wang and Zhi, 2016). Furthermore, green finance channels funds from capital-holding social entities (such as banks and investors) to those in need of funds (such as enterprises and local governments), supporting circular economy projects such as waste treatment facility construction or renewable resource development (Taghizadeh-Hesary, Yoshino (2020)).

Second, as Milios et al. (2019) mention, the development of the circular economy is hindered by the “technological lock-in,” while technology, especially green technological innovation, strongly supports the principles of resource reduction, recycling, and reuse (Chen et al., 2025). On the one hand, green finance focuses on the development of green technologies (Huang et al., 2022), guiding enterprises into the green sector and encouraging green technological innovation (Tang and Zhang, 2020), including biodegradable materials and chemical recycling technologies. Isa et al. (2021) note that Malaysia faces waste management issues, and green technologies are a key driver of the country’s circular economy development. Ivanova and Chipeva (2021) mention that green technologies related to waste recycling more effectively facilitate the transition from a linear economy to a circular economy. On the other hand, green finance promotes the commercialization of green technologies, transforming laboratory innovations into large-scale applications through equity financing (Owen and Vedanthachari, 2022). On the other words, green finance mitigates research and development risks (Yu et al., 2021; Almeida et al., 2013), converting green technologies into economic strategies and achieving the scaling and commercialization of technologies (Vysoká et al., 2021). Accordingly, we propose the following research hypothesis:

H2a: Green finance promotes the development of the circular economy through social loans.

H2b: Green finance promotes the development of the circular economy through green technological innovation.

Spillover effects of green finance

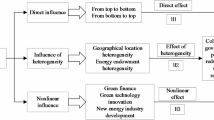

As Huang et al. (2022) note, green finance exhibits regional clustering characteristics, reflecting spillover effects. We explore the spillover mechanisms of green finance from perspectives such as geographic proximity, economic interlinkages, and technological diffusion. First, neighboring regions often have higher levels of connection and interaction (van den Berg et al. (2015)), such as trade relations, resource sharing, or environmental cooperation. Thun (2004) and Li et al. (2022) mention that when environmental regulations are adopted to tackle pollution, leaders in neighboring regions tend to imitate and adopt these practices due to promotion pressures. Second, economic interlinkages ultimately form interdependent and interactive relationships. In the circular economy, various industrial chains are located in different regions (Di et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2020), and the success of one region’s circular economy can affect other regions through the industrial chain. Third, according to the knowledge spillover theory (Hu et al., 2021), the innovative outputs driven by green finance have significant spillover effects. Pandey et al. (2022) argue that through forms such as business collaborations and academic exchanges, advanced technologies or management practices are not limited to the local area, leading to technological diffusion. Therefore, we propose the third research hypothesis, and Fig. 2 illustrates the logical framework:

H3: The impact of green finance on the circular economy has spatial spillover effects.

Data and model construction

To test our research hypothesis, we utilized urban data from the years 2006 to 2021 to investigate the relationship between green finance and the circular economy. The dataset was supported by multiple professional databases: urban data was sourced from the “China Urban Statistical Yearbook,” while other data was obtained from the “China Urban Construction Yearbook.” Missing data were imputed using mean substitution and linear interpolation methods. In the end, we collected 4,464 observations.

Building upon the studies of Chen (2022), Khan et al. (2022), and Lee, Lee (2022), this study extended the model to explore the relationship between green finance and the circular economy.

In Eq. (1), the dependent variable is the circular economy (CE), which is measured using the super-efficiency SBM model. This study draws mainly from the research of De Pascale et al. (2021), Wang et al. (2018), and Chen (2022) in selecting six input factors, including capital, labor, land and resources, pollution control investment, and wastewater treatment capacity. Additionally, four expected outputs are considered, comprising regional GDP, wastewater treatment rate, municipal solid waste treatment rate, and industrial dust removal rate. Three unexpected outputs are also included, encompassing industrial wastewater, industrial dust, and industrial sulfur dioxide emissions. In terms of resource recycling indicators, besides the industrial solid waste utilization rate mentioned by Chen (2022), this study also takes into account the capacity for reclaimed water production. As mentioned by Voulvoulis (2018), water reuse is a crucial element in the circular economy. All data are sourced from the “China Urban Statistical Yearbook” and the “China Urban Construction Yearbook.”

Figure 3 displays the circular economy of 279 cities. The redder the color, the stronger the circular economy. From a temporal perspective, in 2006, China’s circular economy was still in its early stages, with limited activity in most regions. However, the eastern coastal regions made some initial efforts to implement circular economy practices. Subsequently, circular economy activities continued to expand, particularly in the eastern and southern regions of China. By 2021, eastern provinces maintained their leading position, but many central and even some western regions had made substantial progress in promoting circular economy initiatives. From a spatial perspective, the East China region, including cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, remains the most advanced in circular economy activities. These regions benefit from advanced infrastructure, policies that support sustainable development, and a high level of economic development. Overall, there is a clear gap between the eastern coastal regions and the more remote inland and western areas. Circular economy activities in the eastern regions have remained active over the years, while the central and western regions have gradually improved over time, with significant progress by 2021.

The independent variable is green finance (GF), as calculated following the method of Yang et al. (2021). Yang et al. (2021) computed provincial-level green finance based on five aspects: green credit, green securities, green investments, green insurance, and carbon finance. Additionally, following the approach of Chen (2023) who estimated the share of renewable energy in urban and provincial electricity consumption, we used the share of loans balance by financial institutions at the city level to estimate city-level green finance. This is because the development of green finance is closely tied to financial development (Guo et al., 2023).

The control variables in this study were selected based on references to the research conducted by Chen (2022), Khan et al. (2022), Meo and Abd Karim (2022), and Al Mamun et al. (2022). These control variables include: GDP (logarithm of GDP); IS (Share of the tertiary industry’s output); Tech (Share of scientific and technological expenditures); FDI (logarithm of Foreign Direct Investment); PD (Population density); Hos (logarithm of per capita hospital beds); Cul (logarithm of per capita books). These variables were included to control for potential confounding factors and ensure the robustness of the study’s findings. Table 2 shows the green finance, circular economy and other characteristics. In addition, there is no multicollinearity isuue in our model (the correlation coefficient is less than 0.7 and the VIF is 1.93 less than 10).

Regression results

Baseline regression

Table 3 illustrates the relationship between green finance and the circular economy. The results indicate a positive correlation between green finance and the circular economy at a 5% significance level (Hypothesis 1: 0.998), supporting Hypothesis H1. This suggests that green finance can promote the development of the circular economy, overcoming the market barriers highlighted by Grafström and Aasma (2021). This is because green finance provides financial support for circular economy initiatives, including efficient resource utilization, waste reduction, innovative technologies, and market development.

Robustness test

Up to this point, we have conducted a preliminary validation of the relationship between green finance and the circular economy. In this section, we employ instrumental variable methods, a new dependent variable approach, and sub-sample analysis to enhance the robustness of our analytical results.

-

1.

Instrumental variable method: We draw inspiration from the studies by Lee et al. (2023), Ran and Zhang (2023) and use the reciprocal of the shortest distance between cities and ports multiplied by the provincial annual average of Green Finance as our instrumental variable (IV). Ran and Zhang (2023) have noted that distance is exogenously determined, and the interaction term ensures the time variability of the instrumental variable. The first-stage tests for identification and weak identification in the instrumental variable method indicate that the selection of instruments is valid. Additionally, the Hansen test yields a p-value of 0.000 and shows “equation exactly identified,” suggesting that the model is correctly specified.

-

2.

Replacement of the new dependent variable: We have calculated the new circular economy (CE1) using the entropy weight method.

-

3.

Subsample analysis method: Direct-controlled municipalities and provincial capitals receive policy support (Zhang et al., 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to exclude the influence of these cities on the regression results.

-

4.

Propensity Score Match (PSM): To minimize the influence of confounding factors, this study employs PSM. Since the key independent variable is continuous, traditional PSM methods cannot be directly applied. Following Campello and Larrain (2016), the sample is divided into high and low green finance groups based on the upper and lower tertiles, assigned values of 1 and 0, respectively. Using one-to-one nearest neighbor matching, treatment and control groups with parallel pre-treatment trends are constructed to enhance comparability. This is then combined with a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to address endogeneity arising from unobserved factors, strengthening causal inference. Appendix A presents kernel density plots demonstrating a marked improvement in matching quality.

-

5.

New sample period: Although we control for time effects to mitigate the impact of extreme events, the lagged effects of the 2008 financial crisis and the economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of 2019 lead us to limit the regression analysis to panel data from 2010 to 2019, with time effects controlled. First, because the influence of the 2008 financial crisis persisted, we follow the common practice in the literature by starting from 2010 (Campello et al., 2010). Second, as the pandemic emerged late in 2019 with limited impact that year (Hallaert, 2020), 2019 is chosen as the endpoint, excluding 2020 from the sample.

Table 4 shows the results of the three robustness analysis methods. The results show that green finance can contribute to the development of a circular economy.

Mediation effects tests

This section examines how green finance promotes the circular economy from an input-output perspective. As the term suggests, green finance relaxes lending conditions and increases social financing (Guo et al., 2023). On the other hand, the “green” aspect involves the development and innovation of green technologies (Huang et al., 2022). Therefore, we analyze the potential pathways of green finance through two dimensions: social loans and green innovation (both log-transformed). The results in Table 5 indicate significant positive correlations between green finance and social loans (1.482, p < 0.01) as well as green innovation (3.295, p < 0.05). This suggests that increasing social loans and fostering green innovation are critical pathways through which green finance drives the development of the circular economy.

Heterogeneity analysis

Institutional theory suggests that laws, regulations, customs, social norms, professional standards, culture, and ethics influence organizational behavior (Scott, 2005) to maintain legitimacy. In the context of sustainable development, green finance’s promotion of circular economy practices is influenced by multiple pressures from stakeholders such as the government, market, and the public. Correspondingly, this study introduces environmental policy regulation, pollution levels, and environmental awareness to measure the heterogeneity of green finance. Environmental policy regulations are calculated by analyzing the frequency of environmental and pollution-related terms in city government reports (Bao and Liu, 2022). Pollution levels are measured using the average values of industrial sulfur dioxide, wastewater, and soot (Xu et al., 2023). Environmental awareness is measured by the Baidu Index (similar to Google Trends), which tracks the frequency of public searches for environmental terms on Baidu (Lu and Li, 2023). Group regressions are performed based on the median value for each of the three pressures, with the regression results presented in Table 6. The results show that under high environmental regulation, strong environmental awareness, and low pollution levels, green finance significantly promotes the development of the circular economy. However, its impact is not significant in other groups. This suggests that external pressures lead to varying results in how green finance promotes the development of the circular economy.

Spatial effect test

Spatial correlation test

Before conducting spatial econometric analysis, the Moran I index is used to test the spatial correlation of the circular economy. The index value ranges from −1 to 1, where [0,1] indicates spatial clustering and [−1,0] indicates spatial dispersion. Table 7 shows the results based on the distance matrix, and it can be observed that circular economy exhibits significant positive spatial correlation across all years.

Model selection

To determine the best model, we provide regression results for four models: OLS, spatial fixed effects, time fixed effects, and spatial-temporal fixed effects in Table 8. First, the \({R}^{2}\) of spatial effect model is relatively larger. Additionally, the significance of LM_lag and LM_error suggests that choosing the spatial fixed effects model is reasonable.

In the third step, we determine which spatial econometric model to use. So far, three commonly used spatial econometric models are Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), Spatial Lag Model (SLM), and Spatial Error Model (SEM). The SDM accounts for spatial spillover effects in both dependent and independent variables. The SLM focuses solely on the spatial spillover effects of the dependent variable. In contrast, the SEM assumes spatial correlation in the error term and emphasizes spatial dependence within the error structure. The background of LR test and Wald test is that SDM will degenerate into SEM or SLM. Therefore, the results in Table 9 indicate that SDM is the best choice.

In this section, we consider the spatial effects of Green Finance. The results of spatial model experiments in the appendix indicate that selecting the Durbin spatial model with spatial effects is appropriate. Therefore, Table 10 presents the regression results for the distance matrix and the economic matrix. The results show that regardless of which matrix is used, Green Finance exhibits positive spatial effects. Specifically, Green Finance not only promotes the Circular Economy in the local cities but also stimulates the development of neighboring cities.

Performance test for circular economy

The above research demonstrates the strong connection between green finance and the circular economy. But how does the green finance-driven circular economy perform in terms of benefits and costs? We examine this question from the perspectives of carbon emission and governance cost. As shown in Table 11, this relationship results in a significant reduction in carbon emission (CO2: −239.119, p < 0.01) and governance cost (GC: −0.0002, p < 0.01). This indicates that the development of a green finance-driven circular economy positively contributes to achieving sustainability goals and highlights green finance as a crucial financial tool for advancing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Discussion

Our study contributes to the development of the circular economy in multiple ways. First, we incorporate the intersection of green finance, circular economy, spillover effects, and strategic goals within the context of China’s national conditions, filling the gap in traditional circular economy research that has largely overlooked the role of green finance (Ghenţa and Matei, 2018). The findings of this study suggest that green finance can drive the development of the circular economy, extending conclusions drawn from previous research on the role of green finance in innovation, green economic development, and pollution control (Huang et al., 2022; Iqbal et al., 2021). Additionally, as noted by De La Cuesta-Gonzalez and Morales-García (2022) and Saarinen and Aarikka-Stenroos (2022), businesses and individuals participating in the circular economy often face financing difficulties. This study addresses this issue by showing that green finance can provide funding support for circular economy development, including effective resource utilization, waste reduction, technological innovation, and market cultivation.

Second, we analyze in-depth the potential mechanisms of green finance, offering valuable insights for its development. The research findings indicate that social loans and green technological innovation play significant intermediary roles. As Yu et al. (2021) mention, green finance can alleviate corporate financing constraints. At the urban level, green finance can provide strong financial support to the increasingly revitalized environmental protection market. Considering that circular economy-oriented projects are characterized by high risk and substantial capital requirements, finance can reduce investment risks and promote project implementation (Goovaerts and Verbeek, 2018). This research is also supported by Irfan et al. (2022), which highlights that green finance drives technological innovation, including waste regeneration, renewable energy, and environmental technologies, contributing to the realization of the circular economy’s 3R approach (Khajuria et al., 2022). Furthermore, the results based on institutional theory indicate that green finance can significantly advance circular economy development only under high environmental regulation, environmental awareness, and low pollution levels. In environments with high environmental regulation and awareness, green finance can provide the necessary financial support for circular economy projects, while being subject to government and public oversight (van Langen and Passaro, 2021; Gu et al., 2021). It is worth noting that the impact of green finance is insignificant in areas with high pollution levels. This is due to the concentration of industrial enterprises in such regions (Fu et al., 2021), where economic development is heavily dependent on industrial support. The costs of transitioning to a circular economy far exceed their capacity (Yang et al., 2023), and there is insufficient demand for green products and finance (Ozili, 2022).

Finally, considering that green finance in China exhibits characteristics of free flow (Baele et al., 2007), we explore the spatial effects and find that green finance can promote the development of the circular economy in both local and neighboring cities. On a direct level, green finance directly invests in environmental protection and sustainable development projects, such as waste treatment plants, clean energy projects, and renewable resource utilization. On an indirect level, green infrastructure, technology, and knowledge flow can drive the expansion of the circular economy industry chain, promoting the development of neighboring cities or acting as a demonstration effect (Lee et al., 2023). Additionally, this study reveals that the circular economy driven by green finance can reduce carbon emission and pollution control costs. This finding expands on Chen (2022)’s conclusion about the reduction of carbon emissions through the circular economy. Green finance, by optimizing capital allocation and incentivizing low-carbon technology innovation, achieves low-carbon sustainable development and reduces governance costs. Our findings further enhance the theoretical linkage between the circular economy and sustainable development, emphasizing the driving role of green finance.

Conclusion

This study is the first to utilize urban data from 2006 to 2021 to analyze the relationship between green finance and the circular economy, along with its potential effects. The findings are as follows: First, green finance promotes the development of the circular economy. Second, increased social loans and innovation outputs are key potential pathways for green finance. Third, green finance has a greater impact on the circular economy in environments with strong environmental regulations, public awareness, and low pollution levels. Fourth, green finance positively affects both local and neighboring cities’ circular economies. Lastly, the circular economy driven by green finance contributes to the achievement of carbon neutrality goals.

Theoretical Implications

The theoretical significance of this study is multifaceted. First, by addressing the lack of research on the role of green finance in circular economy practices, this study integrates Keynesian theory and the resource-based view to construct a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between green finance and the circular economy, providing new insights into how green finance can promote the transition to a circular economy. Second, the study identifies social loans and green technological innovation as potential pathways for green finance’s impact on the circular economy, emphasizing the importance of supporting pathways to maximize the effectiveness of green finance in driving the transition.

Third, by incorporating institutional theory, the study highlights how pollution levels, environmental regulations, and public awareness influence the effectiveness of green finance. This provides a new theoretical basis for understanding the relationship between finance, the circular economy, and external pressures, enriching the theoretical research in this field. Lastly, the study offers empirical support for policymakers, helping to advance the organic integration of green finance and the circular economy across multiple dimensions. This mixed research approach, combining theory with practice, aids in translating theoretical developments into real-world applications, further promoting the role of green finance in circular economy practices.

Practical implications

First, governments should recognize the effectiveness of green finance in circular economy practices and further improve the legal and regulatory framework for green finance. This includes providing clear standards and incentive measures for financial institutions. Specifically, unified green project certification standards should be established for green credit, green bonds, and other financial products to ensure that green finance funds are directed toward projects aligned with circular economy objectives. Second, governments can encourage financial institutions to increase funding for green projects by offering policies such as special funds, low-interest loans, and tax incentives. This support should be particularly focused on projects centered on green innovation technologies and products. Third, to improve the efficiency of green finance, governments should strengthen environmental regulations, particularly in high-pollution industries and regions. Implementing strict regulatory systems will help foster the development of the circular economy. Additionally, raising public awareness of environmental issues will increase societal recognition of, and participation in, the relationship between green finance and the circular economy. Fourth, governments should actively promote the establishment of regional green finance cooperation mechanisms. Encouraging neighboring cities and regions to collaboratively build cross-regional green development funds or green cooperation platforms will help drive the overall development of the circular economy. Lastly, governments must recognize that, in the pursuit of carbon neutrality goals, it is crucial to fully leverage green finance-driven circular economy practices to ensure the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of the entire economic transition process.

Limitations

There are several areas in this study that warrant further consideration and improvement. Firstly, this study estimates city-level green finance using financial development weights for cities and provinces, as well as provincial green finance indices. This method may introduce biases, and thus, in the future, we intend to estimate city-level green finance through on-site investigations. Secondly, this study focuses on China, which limits the generalizability of the research findings. However, the conclusions are valuable for other developing countries facing challenges related to pollution emissions and economic development conflicts. In the future, we plan to expand the scope of our research to enhance the feasibility of the results related to green finance. Lastly, at present, it is challenging to capture the flow of funds in green finance accurately. Therefore, in the future, we hope to collaborate with financial institutions to observe the flow of funds in green finance, thereby exploring the factors driving the circular economy. Despite the limitations in this study, being the first to explore the connection between green finance and the circular economy, this study contributes to enriching the existing literature.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Agrawal R, Agrawal S, Samadhiya A, Kumar A, Luthra S, Jain V (2024) Adoption of green finance and green innovation for achieving circularity: an exploratory review and future directions. Geosci Front 15(4):101669

Al Mamun M, Boubaker S, Nguyen DK (2022) Green finance and decarbonization: evidence from around the world. Financ Res Lett 46:102807

Alem M, Townsend RM (2014) An evaluation of financial institutions: impact on consumption and investment using panel data and the theory of risk-bearing. J Econ 183(1):91–103

Allen F, Zhang C, Zhao M (2012) China’s financial system: Opportunities and challenges. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17828

Almeida H, Hsu PH, Li D (2013) Less is more: Financial constraints and innovative efficiency. Available at SSRN 1831786

Baele L, Pungulescu C, Ter Horst J (2007) Model uncertainty, financial market integration and the home bias puzzle. J Int Money Financ 26(4):606–630

Bao R, Liu T (2022) How does government attention matter in air pollution control? Evidence from government annual reports. Resour, Conserv Recycling 185:106435

Basten S, Jiang Q (2015) Fertility in China: an uncertain future. Popul Stud 69(sup1):S97–S105

Blomsma F, Brennan G (2017) The emergence of circular economy: a new framing around prolonging resource productivity. J Ind Ecol 21(3):603–614

Bourcet C, Bovari E (2020) Exploring citizens’ decision to crowdfund renewable energy projects: quantitative evidence from France. Energy Econ 88:104754

Bracking S, Leffel B (2021) Climate finance governance: fit for purpose? Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Clim Change 12(4):e709

Campiglio E (2016) Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Ecol Econ 121:220–230

Canova TA (2009) Financial market failure as a crisis in the rule of law: from market fundamentalism to a new Keynesian regulatory model. Harv L Pol’y Rev, 3:369

Campello M, Graham JR, Harvey CR (2010) The real effects of financial constraints: Evidence from a financial crisis. J Financ Econ 97(3):470–487

Campello M, Larrain M (2016) Enlarging the contracting space: Collateral menus, access to credit, and economic activity. Rev Financ Stud 29(2):349–383

Chen, P (2022). The spatial impacts of the circular economy on carbon intensity-new evidence from the super-efficient SBM-DEA model. Energy Environ 0958305X221125125

Chen P (2023) Urban planning policy and clean energy development Harmony-evidence from smart city pilot policy in China. Renew Energy 210:251–257

Chen P, Chu Z, Zhao Y, Li Y (2025) Is urban innovation capacity shaping new models of economic development? Evidence from the circular economy. Sustain Dev 33(1):758–770

Chen Q, Ning B, Pan Y, Xiao J (2021) Green finance and outward foreign direct investment: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment of green insurance in China. Asia Pac J Manag 1–26

De Angelis R, Howard M, Miemczyk J (2018) Supply chain management and the circular economy: towards the circular supply chain. Prod Plan Control 29(6):425–437

De Jesus A, Mendonça S (2018) Lost in transition? Drivers and barriers in the eco-innovation road to the circular economy. Ecol Econ 145:75–89

De La Cuesta-Gonzalez M, Morales-García M (2022) Does finance as usual work for circular economy transition? A financiers and SMEs qualitative approach. J Environ Plan Manag 65(13):2468–2489

De Pascale A, Arbolino R, Szopik-Depczyńska K, Limosani M, Ioppolo G (2021) A systematic review for measuring circular economy: the 61 indicators. J Clean Prod 281:124942

Debrah C, Chan APC, Darko A (2022) Green finance gap in green buildings: a scoping review and future research needs. Build Environ 207:108443

Dewick P, Bengtsson M, Cohen MJ, Sarkis J, Schröder P (2020) Circular economy finance: clear winner or risky proposition? J Ind Ecol 24(6):1192–1200

Di K, Chen W, Zhang X, Shi Q, Cai Q, Li D, Di Z (2023) Regional unevenness and synergy of carbon emission reduction in China’s green low-carbon circular economy. J Clean Prod 420:138436

Ferrari-Filho F, Conceição OAC (2005) The concept of uncertainty in post Keynesian theory and in institutional economics. J Econ Issues 39(3):579–594

Fu S, Ma Z, Ni B, Peng J, Zhang L, Fu Q (2021) Research on the spatial differences of pollution-intensive industry transfer under the environmental regulation in China. Ecol Indic 129:107921

Garcés-Ayerbe C, Rivera-Torres P, Suárez-Perales I, Leyva-de la Hiz DI (2019) Is it possible to change from a linear to a circular economy? An overview of opportunities and barriers for European small and medium-sized enterprise companies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(5):851

García-Barragán JF, Eyckmans J, Rousseau S (2019) Defining and measuring the circular economy: a mathematical approach. Ecol Econ 157:369–372

Geissdoerfer M, Morioka SN, de Carvalho MM, Evans S (2018) Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. J Clean Prod 190:712–721

Geissdoerfer M, Savaget P, Bocken NM, Hultink EJ (2017) The Circular Economy–a new sustainability paradigm? J Clean Prod 143:757–768

Ghenţa M, Matei A (2018) SMEs and the circular economy: From policy to difficulties encountered during implementation. Amfiteatru Econ 20(48):294–309

Ghisellini P, Cialani C, Ulgiati S (2016) A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J Clean Prod 114:11–32

Goovaerts L, Verbeek A (2018) Sustainable banking: finance in the circular economy. Invest Resour Effic Econ Polit Financ Resour Trans 191–209

Graedel TE (1996) On the concept of industrial ecology. Annu Rev Energy Environ 21(1):69–98

Grafström J, Aasma S (2021) Breaking circular economy barriers. J Clean Prod 292:126002

Gu B, Chen F, Zhang K (2021) The policy effect of green finance in promoting industrial transformation and upgrading efficiency in China: analysis from the perspective of government regulation and public environmental demands. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28(34):47474–47491

Guo W, Yang B, Ji J, Liu X (2023) Green finance development drives renewable energy development: mechanism analysis and empirical research. Renew Energy 215:118982

Haseli G, Deveci M, Isik M, Gokasar I, Pamucar D, Hajiaghaei-Keshteli M (2024) Providing climate change resilient land-use transport projects with green finance using Z extended numbers based decision-making model. Expert Syst Appl 243:122858

Heilmann S, Schmidt DH (2014) China’s foreign political and economic relations: an unconventional global power. Rowman & littlefield

Hallaert J-J (2020) Poverty and Social Protection in Bulgaria. IMF Working Paper No. 20/147, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3721188

Hu F, Xi X, Zhang Y (2021) Influencing mechanism of reverse knowledge spillover on investment enterprises’ technological progress: an empirical examination of Chinese firms. Technol Forecast Soc Change 169:120797

Huang Y, Chen C, Lei L, Zhang Y (2022) Impacts of green finance on green innovation: a spatial and nonlinear perspective. J Clean Prod 365:132548

Iqbal S, Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Mohsin M, Iqbal W (2021) Assessing the role of the green finance index in environmental pollution reduction. Stud Appl Econ 39(3)

Irfan M, Razzaq A, Sharif A, Yang X (2022) Influence mechanism between green finance and green innovation: exploring regional policy intervention effects in China. Technol Forecast Soc Change 182:121882

Isa NM, Sivapathy A, Adjrina Kamarruddin NN (2021) Malaysia on the way to sustainable development: circular economy and green technologies. In Modeling economic growth in contemporary Malaysia (pp. 91–115). Emerald Publishing Limited

Ivanova V, Chipeva S (2021) The impact of green technologies on transition to circular economy. Manag Bus Res Q 17:55–71

Jin Y, Gao X, Wang M (2021) The financing efficiency of listed energy conservation and environmental protection firms: evidence and implications for green finance in China. Energy Policy 153:112254

Johnson B, Lundvall BA (1994) The learning economy. J Ind Stud 1(2):23–42

Jovane F, Yoshikawa H, Alting L, Boer CR, Westkamper E, Williams D, Paci AM (2008) The incoming global technological and industrial revolution towards competitive sustainable manufacturing. CIRP Ann 57(2):641–659

Kalkbrenner BJ, Roosen J (2016) Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: the role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Res Soc Sci 13:60–70

Khajuria A, Atienza VA, Chavanich S, Henning W, Islam I, Kral U, Li J (2022) Accelerating circular economy solutions to achieve the 2030 agenda for sustainable development goals. Circ Econ 1(1):100001

Khan MA, Riaz H, Ahmed M, Saeed A (2022) Does green finance really deliver what is expected? An empirical perspective. Borsa Istanb Rev 22(3):586–593

Kinnunen PHM, Kaksonen AH (2019) Towards circular economy in mining: opportunities and bottlenecks for tailings valorization. J Clean Prod 228:153–160

Korhonen J, Nuur C, Feldmann A, Birkie SE (2018) Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J Clean Prod 175:544–552

Koval V, Laktionova O, Atstāja D, Grasis J, Lomachynska I, Shchur R (2022) Green financial instruments of cleaner production technologies. Sustainability 14(17):10536

Kumar B, Kumar L, Kumar A, Kumari R, Tagar U, Sassanelli C (2024) Green finance in circular economy: a literature review. Environ Dev Sustain 26(7):16419–16459

Lazarevic D, Valve H (2017) Narrating expectations for the circular economy: towards a common and contested European transition. Energy Res Soc Sci 31:60–69

Lee CC, Lee CC (2022) How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energy Econ 107:105863

Lee CC, Wang F, Lou R, Wang K (2023) How does green finance drive the decarbonization of the economy? Empirical evidence from China. Renew Energy 204:671–684

Li L, Sun J, Jiang J, Wang J (2022) The effect of environmental regulation competition on haze pollution: evidence from China’s province-level data. Environ Geochem Health 1–24

Liu K, Lin B (2019) Research on influencing factors of environmental pollution in China: a spatial econometric analysis. J Clean Prod 206:356–364

Lu J, Li H (2023) The impact of environmental corruption on green consumption: a quantitative analysis based on China’s Judicial Document Network and Baidu Index. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 86:101451

Lv C, Fan J, Lee CC (2023) Can green credit policies improve corporate green production efficiency? J Clean Prod 397:136573

Mahoney JT, Pandian JR (1992) The resource‐based view within the conversation of strategic management. Strateg Manag J 13(5):363–380

Masi D, Kumar V, Garza-Reyes JA, Godsell J (2018) Towards a more circular economy: exploring the awareness, practices, and barriers from a focal firm perspective. Prod Plan Control 29(6):539–550

Meo MS, Abd Karim MZ (2022) The role of green finance in reducing CO2 emissions: an empirical analysis. Borsa Istanb Rev 22(1):169–178

Miao Q (2019) Environmental benefit analysis of China’s green finance in waste recycling. Adv Ind Eng Manag 8(1):4–6

Milios L, Beqiri B, Whalen KA, Jelonek SH (2019) Sailing towards a circular economy: conditions for increased reuse and remanufacturing in the Scandinavian maritime sector. J Clean Prod 225:227–235

Mohd S, Kaushal VK (2018) Green finance: a step towards sustainable development. MUDRA J Financ Account 5(1):59–74

Moraga G, Huysveld S, Mathieux F, Blengini GA, Alaerts L, Van Acker K, Dewulf J (2019) Circular economy indicators: what do they measure? Resour Conserv Recycling 146:452–461

Muganyi T, Yan L, Sun HP (2021) Green finance, fintech and environmental protection: evidence from China. Environ Sci Ecotechnol 7:100107

Negi L, Manpreet M, Singh M (2025) Green finance and digital strategies: catalysts for the expansion of circular technologies in the global market. In Innovating Sustainability Through Digital Circular Economy (pp. 281−304). IGI Global Scientific Publishing

Nogueira A, Ashton WS, Teixeira C (2019) Expanding perceptions of the circular economy through design: Eight capitals as innovation lenses. Resour Conserv Recycling 149:566–576

Owen R, Vedanthachari L (2022) Exploring the role of UK government policy in developing the university entrepreneurial finance ecosystem for cleantech. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 70(3):1026–1039

Ozili PK (2022) Green finance research around the world: a review of literature. Int J Green Econ 16(1):56–75

Pandey N, de Coninck H, Sagar AD (2022) Beyond technology transfer: Innovation cooperation to advance sustainable development in developing countries. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Energy Environ 11(2):e422

Parajuly K, Green J, Richter J, Johnson M, Rückschloss J, Peeters J, Fitzpatrick C (2024) Product repair in a circular economy: exploring public repair behavior from a systems perspective. J Ind Ecol 28(1):74–86

Park H, Kim JD (2020) Transition towards green banking: role of financial regulators and financial institutions. Asian J Sustain Soc Responsib 5(1):1–25

Pasinetti LL (2005) The Cambridge school of Keynesian economics. Camb J Econ 29(6):837–848

Pauli GA (2010) The blue economy: 10 years, 100 innovations, 100 million jobs. Paradigm publications

Pearce DW, Turner RK (1989). Economics of natural resources and the environment. Johns Hopkins University Press

Ran C, Zhang Y (2023) The driving force of carbon emissions reduction in China: Does green finance work. J Clean Prod 421:138502

Rankonyana L (2015) An analysis of the effect of organisational capacity on organisational performance in project implementation: case of the Organisation of Rural Associations for Progress (ORAP) (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University)

Rasoulinezhad E, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2022) Role of green finance in improving energy efficiency and renewable energy development. Energy Effic 15(2):14

Rizos V, Behrens A, Kafyeke T, Hirschnitz-Garbera M, Ioannou A (2015) The Circular Economy: Barriers and Opportunities for SMEs. CEPS Working Documents No. 412/September 2015

Rizos V, Behrens A, Van der Gaast W, Hofman E, Ioannou A, Kafyeke T, Topi C (2016) Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): barriers and enablers. Sustainability 8(11):1212

Rodríguez-Pose A, Wilkie C (2019) Strategies of gain and strategies of waste: what determines the success of development intervention? Prog Plan 133:100423

Saarinen A, Aarikka-Stenroos L (2022) Financing-related drivers and barriers for circular economy business: developing a conceptual model from a field study. Circular Econ Sustain 1–25

Scott WR (2005) Institutional theory: contributing to a theoretical research program. Gt Minds Manag Process Theory Dev 37(2):460–484

Sehnem S, Vazquez-Brust D, Pereira SCF, Campos LM (2019) Circular economy: benefits, impacts and overlapping. Supply Chain Manag Int J 24(6):784–804

Seroka-Stolka O, Ociepa-Kubicka A (2019) Green logistics and circular economy. Transp Res Procedia 39:471–479

Sharma GD, Verma M, Shahbaz M, Gupta M, Chopra R (2022) Transitioning green finance from theory to practice for renewable energy development. Renew Energy 195:554–565

Singh S (1999) China’s energy policy for the 21st century. Strateg Anal 22(12):1871–1885

Soundarrajan P, Vivek N (2016) Green finance for sustainable green economic growth in India. Agricult Econ Zemědělská Ekonomika, 62(1)

Stahel W (2010) The performance economy. Springer

Stahel W, Reday-Mulvey G (1976) Jobs for Tomorrow: The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy, Report to the Commission of the European Communities (now European Commission). Commission of the European Communities, Brussels. Brussels

Sun H, Chen F (2022) The impact of green finance on China’s regional energy consumption structure based on system GMM. Resour Policy 76:102588

Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Yoshino N (2020) Sustainable solutions for green financing and investment in renewable energy projects. Energies 13(4):788

Tang DY, Zhang Y (2020) Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? J Corp Financ 61:101427

Tang J, Tong M, Sun Y, Du J, Liu N (2020) A spatio-temporal perspective of China’s industrial circular economy development. Sci total Environ 706:135754

Thun E (2004) Keeping up with the Jones’: Decentralization, policy imitation, and industrial development in China. World Dev 32(8):1289–1308

Tian H (2018) Establishing green finance system to support the circular economy. Industry 4.0: Empowering ASEAN for the Circular Economy, 203

Tleuken A, Tokazhanov G, Jemal KM, Shaimakhanov R, Sovetbek M, Karaca F (2022) Legislative, institutional, industrial and governmental involvement in circular economy in Central Asia: a systematic review. Sustainability 14(13):8064

Tura N, Hanski J, Ahola T, Ståhle M, Piiparinen S, Valkokari P (2019) Unlocking circular business: a framework of barriers and drivers. J Clean Prod 212:90–98

van den Berg P, Arentze T, Timmermans H (2015) A multilevel analysis of factors influencing local social interaction. Transportation 42:807–826

van Langen SK, Passaro R (2021) The Dutch green deals policy and its applicability to circular economy policies. Sustainability 13(21):11683

Voulvoulis N (2018) Water reuse from a circular economy perspective and potential risks from an unregulated approach. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2:32–45

Vysok L, Dörr R, Sarris S, Gáthy G (2021) Technology Transfer and Commercialisation for the European Green Deal

Wang EK (2017) Financing green: reforming green bond regulation in the United States. Brook J Corp Fin Com L 12:467

Wang KH, Zhao YX, Jiang CF, Li ZZ (2022) Does green finance inspire sustainable development? Evidence from a global perspective. Econ Anal Policy 75:412–426

Wang N, Lee JCK, Zhang J, Chen H, Li H (2018) Evaluation of Urban circular economy development: an empirical research of 40 cities in China. J Clean Prod 180:876–887

Wang Y, Zhi Q (2016) The role of green finance in environmental protection: two aspects of market mechanism and policies. Energy Procedia 104:311–316

Wernerfelt B (1984) A resource‐based view of the firm. Strateg Manag J 5(2):171–180

Xu C, Cai Y, Zhou C, Qi Y (2023) The impact of VAT tax sharing on industrial pollution in China. J Clean Prod 415:137926

Xu H, Mei Q, Shahzad F, Liu S, Long X, Zhang J (2020) Untangling the impact of green finance on the enterprise green performance: a meta-analytic approach. Sustainability 12(21):9085

Yang M, Chen L, Wang J, Msigwa G, Osman AI, Fawzy S, Yap PS (2023) Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues. Environ Chem Lett 21(1):55–80

Yang Y, Su X, Yao S (2021) Nexus between green finance, fintech, and high-quality economic development: empirical evidence from China. Resour Policy 74:102445

Yu CH, Wu X, Zhang D, Chen S, Zhao J (2021) Demand for green finance: resolving financing constraints on green innovation in China. Energy Policy 153:112255

Zhang D, Mohsin M, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2022) Does green finance counteract the climate change mitigation: asymmetric effect of renewable energy investment and R&D. Energy Econ 113:106183

Zhang K, Zhang ZY, Liang QM (2017) An empirical analysis of the green paradox in China: from the perspective of fiscal decentralization. Energy Policy 103:203–211

Acknowledgements

This study is sponsored by the National Social Science Fund of China (NO. 24XJL001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources; QC writing original draft, review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, P., Chen, Q. Two birds with one stone: can green finance drive the circular economy?. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05626-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05626-w