Abstract

Transformation Design is an inter- and transdisciplinary approach aiming at establishing a positive interdependence of otherwise “incommensurable” or even opposed actors and forces in evolving societal systems. Its primary goal is to increase the “pan-resilience” of the overall system through the mutually productive interconnection of its constituent parts, for the sake of co-advancement. Contrary to previous, rather sector-focused approaches, contemporary interpretations of Transformation Design intend to forge a more encompassing interrelation of wholes and parts in communities, yet without reducing diversity. Under the pressure of disruptive systemic crises, Transformation Design intends to promote a better shared and, wherever possible, more holistic and thus more sustainable metamorphosis of societal processes in order to improve coherence, joint reliability and solidarity, as well as the mutual adaptation of dynamic processes within and from outside the social system to strengthen continuity. Contrary to its use in authoritarian environments, in open societies, Transformation Design fulfills this complex task, among other procedures, by constantly negotiating change conflicts through the creation of inclusive and system-oriented compromises at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels, while leaving the single participating actors and their societal sub-systems as autonomous and self-governed as possible. As such, in principle, multi-sectorial and transversal, communitarian and forward-oriented, i.e., synchronic and diachronic, and thus, on most occasions, a creatively pluri-dialogical approach, contemporary Transformation Design can be regarded as an example of transdisciplinarity applied to practical societal evolution. Transformation Design can therefore relate crucial aspects of its timely role and identity to the fact of being, to some extent, one realization of the classical “Charta of Transdisciplinarity” in action, 30 years later.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: a liminal world

Unlike in some earlier stages of its modern deployment, when both its self-definitions and ambitions appear to have been rather tighter (cf. Buenning, 2019; Kehrer, 2020; Molenaar & Kessler, 2021), contemporary Transformation Design could be defined as being one “strong” conceptual answer (among others) to the ever-changing world of “post-postmodern” hyper-complexity (Nealon, 2012). This is a world situated in the second decade of the 21st century, which tends to feature unconventional or even “post-formal” legitimatory, processual, and organizational patterns (Gidley, 2016). It is characterized by blurred order concepts, extended understandings of ethics, an increasing transversality of social subsectors, and shifting self-images of individual and collective actors (Benedikter and Fathi, 2021).

This world came into existence by the means of the first two decades of the 21st century, consisting of repeated “bundled crises” created by a previously unseen variety of persisting (and partly overlapping) “crisis bundles” that, over time, touched upon the socio-psychological bases of the until then customary social systems (Benedikter and Kofler, 2019; Fathi, 2021). The “two-thousands” have been considered as one of the most dynamic and instable eras of modernity, being branded as the historical phase of (1) the age of information and rapid technological advancements, (2) the dialectics of globalization, de-globalization and re-globalization, and (3) geopolitical shifts towards multipolarity and, in general, a more pluri-systemic global order (Steger, 2025; Benedikter, 2021).

As a result of such dynamic “liquidity” (Bauman, 2000), in the societal ecosystems of the 2020s, the principle of “liminality” (World Studies Federation, 2023) seems to have become the only constant in a maelstroem of phenomena and interpretations whose profoundly contested representations by information trusts tending to simplification and neo-ideologization have widely replaced the previously rather uniform notion of “facts”, thus creating life-worlds based on much more complex and unreliable patterns than the 20th century was used to. In this volatile ecosystem, the fundamental condition of “liminality” can be understood as the constant flow of simultaneous change processes without particular order or relation to each other, situated in environments of open yet undetermined transition. “Liminality” as the main characteristic of the “age of re-globalization” means that the previous order has been shaken or dissolved, but a new order is not yet in sight. It is a status of “in-between” the old and the new, the past and the future, where orientation is absent and change is the only graspable reality with which all actors have to deal practically, but, in most cases, on their own, at least in the perception and psychological sentiment of a majority of people.

Liminality and fragmentation

As, in this sense, liminality can be regarded as the primary condition of contemporary transformation processes, it itself is characterized, in its core, by the three pillars of hyper-complexity (Dominici, 2020), uncertainty (Foreign Affairs, 2022), and acceleration (Friedman, 2016). Together, these three pillars form a sort of self-fulfilling hermeneutical circle: hyper-complexity is defined by the combination of accelerated uncertainty and uncertain acceleration, and in turn constantly gives birth to both. Although there are, at any given moment in time, innumerable attempts to put a unifying structure to this “pluriversal” situation of – at least apparently – poorly- or even non-directed transition, there seems to be no overarching, consensually defined or shared point of arrival or precise goal of the respective procedures and processes of change (cf. Ford, 2006).

Consequently, a notorious fragmentation of interventions has become the systemic norm, leading to the widespread perception of a reduced or diminishing power of public policies, politics in general, and decision-makers at-large (Boulianne, Oser & Hoffmann, 2023). This has been accompanied by a “loss-of-control”-psychology (Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 2025; Martin, 2023; Benedikter and Fathi, 2021), which, on the one hand, leads to an increased “self-measurement” of individuals as “the new digital normality for the purposes of self-insurance” (Scheibmaier, 2021) and, on the other hand, promotes populist simplifications in the public realm in order to create a (false) sense of security. Other effects of social fragmentation by the means of the combination of complexity, uncertainty and acceleration are the polarization of public rationality in “black-or-white” views which cultivate an “either-or” mentality that is contrary to pluralistic democratic values, and the partial mutual self-isolation of actors and groups under the weight of the constantly moving economic, social, technological and ideological processes of an era, where there is an overflow of information that cannot be sufficiently integrated by the individual. Many people, especially in open societies, feel overwhelmed by the abundance of contradictory information and thus retreat into information and communication bubbles characterized by a uniform, if not “unitarian” world view in order to streamline things and make them better manageable.

This trend follows the paradoxical law of increased structural disconnectedness of individuals in highly networked societies (Minh Pham, Kondor, Hanel, and Thurner, 2020). This law consists of the trend of individuals to retreat into safe spaces of ideological and worldview peer groups, which tend, from an early stage on, to deform into interpretation and worldview bubbles aiming at being self-sufficient and not to interact anymore with other ideologies and worldviews in an increasingly virtual ecosystem characterized by a universalized “attention economy” (Goldhaber, 1997). The respective processes are, depending on specific contexts, co-defined by new political tribalisms (Chua, 2018) and “competing modernities” (Stuenkel, 2015), i.e., sub-cultures incubating (and propagating) very different and often opposed ideas of what a “good life” for themselves or the whole of society is or should be.

The greater picture: a “leviathanic” transformation scenery

All this truly “leviathanic” progression scenery is, last but not least, since the mid-2010s surrounded by a rather notoriously unstable geopolitical situation consisting of “slowbalization” (Aiyar & Ilyina, 2023) combined with “reglobalization” (Benedikter, 2020; Livni, 2024). In its framework, both principles and practices of global governance (cf. Jang, McSparren and Rashchupkina, 2016) have been gradually reduced, and pro-positive international interdependencies have been diminishing in the face of the rise of new nationalisms (cf. Benedikter, 2025a). In this regard, the rapid and widely unregulated development of the digital realm in the 2020s leading to competing AI- and chatbot-cultures of the East and the West located within a “splinternet” (York, 2022) of at least four different ideological realizations of the internet (O’Hara, Hall and Cerf, 2021) has played a seminal role in the step-by-step dissolving of known orientation instruments and, in general, the openness of joint global acting spaces.

As a reaction to such overwhelming complexity, there have been growing trends to reduce pluralism in all kinds of transformation processes to simplified views and (wishful) “world explanations from a single mold”. The overall situation of social fragmentation leading to new nationalisms mixed with information bubbles was, in essence, predicted by “postmodern” philosophers and theorists from the second half of the 1980s onwards as an upcoming world of “fundamental incommensurabilities” (Lyotard, 1988) connected to “immaterialization” (Lyotard and Chaput, 1985) and a “loss of the real” (Noys, w.j.) which would eventually lead to the question of how democracy could survive a social condition with a high degree of fragility and no consensus among profoundly “different” actors (Lyotard, 1988). Despite this more or less precise anticipation, though, it could obviously not be prevented by policy-makers, technocrats, or public rationality, the latter in the sense of “acting by the means of non-violent communication” (Habermas, 1991). Some analysts thus interpret the “world of liminality” of the 2020s as being, in ultima ratio, the “natural” consequence of civilizational evolution towards a more mature modernity located within a saturated global technocracy where hyper-interconnection of profoundly “antipodal” actors leads to arbitrariness, a dilution of common values upon which to build joint concepts of change and, ultimately, to structural indifference.

Transformation in times of liminality: not conceivable without Anti-Transformation

Interestingly, this situation of dynamic complexity, looseness, and “post-stability” in turn tends to produce its own stabilities by – mostly subconsciously – opposing or blocking transformation. As sociologist Armin Nassehi has pointed out (Nassehi, 2024), exactly due to the contemporary characteristics of “liquid complexity” and the omnipresence of change as the “new normal”, societal structures tend to protect themselves from going into tilt by the means of a sturdy self-affirmation, which is implemented by institutional and systemic resistance to change. The resistance to “post-normal” change which is perceived, by larger parts of populations, as overwhelming, exaggerated, out of control or at least not sufficiently manageable, has been interpreted by some pundits as a “social pathology” which is an effect – and at the same time stands at the roots of – the “polycrisis” age of the 21st century (Purdey, 2025).

As Nassehi analyzes, it is therefore time for communities to think differently about the very nature and essence of social transformation because there is an obstinacy of society against it, which reacts stubbornly and with its own means to any form of transformation, control, improvement, or change (Nassehi, 2024). This has led to a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, in the 2020s, there is a constant discourse on transformation related mainly to sustainability, while on the other hand, change is perceived as a threat by those whose way of life depends on the fragile balance of existing conditions. These strata of the population are not only the elites but also the middle classes, which feel threatened by decline. Social practice is therefore primarily characterized by self-affirmation, repetition, and the self-stabilization of the tried and tested. This leads to the question: Are contemporary societies transforming or being transformed? In such situations, some people love grand gestures in evoking transformation, something pastoral, which – like everything pastoral – provokes resistance, especially among non-believers.

Contrary to such a pathos-ridden approach claiming that transformation must save the world, if possible here and now, it seems wiser and more productive to think more concretely not only about generating solutions, but also (1) where and how such solutions can be implemented in society, and (2) where society’s backlash to attempts of transformation can be expected. As Nassehi and scholar Roland Psenner (Psenner, 2025) have pointed out, systems are more stable than their environment. This inertia is the ordering function of systems of all kinds, including social systems, which do not implement environmental, economic, political, or technological changes one-to-one. Inertia is not a program, not a whim, not a matter of taste, but a structural protective mechanism against transformation built into the self-preservation of everything that exists – a mechanism of delay and procrastination which also has its costs. Every day routines are resistant; habit is powerful. From a sociological perspective, the moderating factor is society itself, its internal dynamics, its self-limitation, and the specific form of its possibilities. When experts try to convince people how wonderful the transformed world will be, this very attempt per se generates resistance, incomprehension, and even hatred. One starting topic of understanding Transformation Design must therefore be the question of how society “naturally” reacts to the pressure for transformation. In this sense, Transformation Design must be conceived as being not so much about individual programs, but about the operating system on which the single programs run.

This suggests that Transformation Design only makes sense if it is calibrated in a holistic manner for the whole of society; if its single measures are concrete rather than rhetorical; and if they are implemented in harmony with social issues, not as social issues. All single issues with which Transformation Design can or should deal, such as, to take just a few eclectic examples, climate protection, transport planning, architecture, energy, nutrition, etc., should, according to Nassehi, be addressed in small, concrete steps instead of great gestures of transformation. In Nassehi’s view, small steps are not a reduced form, but the right evolutionary form of change in times of fragmentation, exactly when a more holistic approach is attempted, which may seem a paradox. Nassehi, therefore in ultima ratio advocates an ethic of transformation that increases the range of choices available for the greatest number of people (Nassehi, 2024).

Changing ecosystems at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels

Against the backdrop of this profoundly paradoxical structure of contemporary change (and for the reasons connected to and implied with it), the very raison d’etre of any potential or actual intervention is, first of all by sheer instinct, to try to deal inclusively with this multi-fragmented, socially and ideologically shattered world and its often paradoxical challenges, so to make no enemies and to leave no one behind. Consequently, the primordial idea of Transformation Design already implies aiming at more than just those justice-oriented, selective, and situational interventions, as preached by the remnants of constructivism and deconstructivism as the allegedly sole options remaining in the 21st century. Transformation Design, at its very roots and in principle, does not follow the ideologies of universal relativism. It, on the contrary, aims at serving as an integrative tool in the double sense of a theoretical umbrella and networked policy choice rooted both above and within hypercomplexity-driven change processes.

This – certainly bold and ambitious – aspiration of trying to converge the non-integrable has come into existence primarily due to the fact that Transformation Design in the 21st century has been operating, by its contemporary founding principles (Jonas, Zerwas & von Anshelm, 2015), on the ground of complex ecosystems (Caspers, 2021). These ecosystems have been – and are – in most cases created by – and situated at – the interfaces of already in themselves inter- and trans-disciplinarily structured local, regional, national, and trans-national contexts of reference, including widely differing and often conflicting social, political, economic, and cultural subsystems, habits, and lead narratives.

For example, post-pandemic Transformation Design has to acknowledge that the self-conception of globalization, as the so-far most complexity-adequate point of reference in governing “complex and fast” change (Steger, 2017), has transformed from “one globalization” dominating the three globalization-“happy” decades from 1990 to 2020 to a de facto situation of double or “unhappy” “twin globalization” in the 2020s (Benedikter, 2023a). The term “twin globalization” seeks to describe the coexistence of two competing macro-conceptions of globality and globalism, which are advanced in conflicting ways by the two global blocs of democracies versus autocracies. These two blocs are increasingly challenging each other for supremacy as regards economy, politics, and ideology, thereby igniting both conflict and innovation. To make things even more tricky, both blocs remain financially, economically, and technologically closely intertwined, and thus constantly produce “hybrid” ideas, things, institutional procedures, and, last but not least, people at their interface. No wonder, then, that there is a third bloc situated exactly between them which calls itself “Actively Non-Aligned”, or the ANA countries bloc (Heine, 2025), which takes advantage by adhering to no side but choosing and switching freely and ad hoc for its own benefit.

In addition, twin globalization as the macro-vessel of contemporary transformation is being accompanied by the three historical forces of:

-

1.

re-globalization (Benedikter, 2021),

-

2.

glocalization (Benedikter, Gruber & Kofler, 2021), and

-

3.

futurization (Benedikter, 2025b).

These are three powerful macro-trends operating transversally within the ecosystem of contemporary complexity, uncertainty, and acceleration. They are contributing towards transforming the patterns of present (and probably also upcoming) interconnectivity (Benedikter, 2025c). Consequently, they, too, are modifying the mechanisms of how to master processes in the realms of transition (economy), change (politics), and transformation (society).

The contemporary key question of how to re-create the “social organism”. The answer is: By interconnecting “layers of stratification”

Together, these elements and forces specific to contemporaneity have led to today’s stratified network of pluri-systemic layers of actors, receivers, and impact factors. These are of unequal size and of highly diverse, partly mutually opposed guiding imaginaries and narratives. They cultivate a wide range of anticipatory expectations and timeframe projections of whereto transformation may lead and when. Faced with the task of managing their evolving interface, including utopian and dystopian imaginaries which, in times of globally interconnected media, are becoming ever more directly politically influential and exert an impact on contextual political factors such as social psychology, culture, world views and philosophy (Goodin & Tilly, 2006), Transformation Design is challenged to act in multi-layered ways considering both space and time. This means that it must try to integrate not only the perspective of a linear dimension of evolution, but three simultaneously present levels:

-

the linear diachronic level, including historical subconscious factors, remnants of archetypes, and continued identity projections from the past;

-

the non-linear synchronic level, including the synchronicity of often contradictory actors, ideologies, influences and timely events, trends and pressures;

-

and the meta-linear anticipatory level, including the paradoxical emergence of unknowns, the unforeseeable, the unexpected and the impact of the still-not-existent (Poli, 2019).

Challenged by the “age of uncertainty” (Foreign Affairs, 2022), Transformation Design is therefore tasked to equally interact with – and learn from – all three classical pillars in the time-space continuum: the past, the present, and the future. Ideally, it should do so in balanced, pragmatic, ideologically unbiased, and viability-oriented ways which serve the primary task of “social integration” by converging layers of “social stratification” (Grunow et al. 2023).

Transformation towards what? By necessity, the future

If these are the main ingredients with which Transformation Design must work, the question extent to which there is a methodological integrability of past, present and future at all at the interface of analysis and action remains a huge difficulty that reaches far beyond systems thinking and transformation government (cf. Omar, Weerakkody and Daowd, 2020). In particular, the question: How can we learn from a non-existent future for, and in, the present to optimize hyper-heterogeneous transformation mechanics? has become an essential benchmark of credibility for every complexity-adequate Transformation Design. This fundamental question is about integrating futures thinking (Benedikter, 2025c) into the understanding of transformation, so as to be able to co-design futures (Groß & Mandir, 2024) by looking backwards from (still non-existent) futures to emerging presents on various levels of action, from the systemic to the specialist one (Marien, 2010). Looking backwards from an imagined yet still-not-real future in the sense of “present-oriented reparative futures” (Gómez-Suárez, 2023) is increasingly becoming available to transformation research and analysis (Richardson, Burgess, and Hofmann, 2024) and transformation leadership (Stojanovic, 2019). This is a result of the rapidly advancing options offered by the combination of sensor-gained microdata, automatization of data integration through Big Data, AI (systemic), and Chatbot (individual) information-integration options, and the multiplication of predictive approaches. Their combination by Transformation Design ensures that futures are coming closer to reality than ever before, with increasing precision. In this way, futures are changing the present of transformation, as well as the self-understanding of its role and function regarding the nature, the direction, and the goal of processes of change (cf. Benedikter and Fathi, 2021).

Evolving self-concepts of transformation

As a result of the growing infusion of futures in the realities of transformation, the so far self-ascribed identities of Transformation Design are themselves in flux. Over the past few years, most of its – previously often strongly differing – concepts have become increasingly permeable to each other, with one unifying constant: What was “Transformation Design” is now on its way to “Transformative Design”. This means that the focus has shifted from shaping transformation processes by design to making design itself an, in principle, conscious and active transformative tool wherever it is applied. As a consequence, Transformation Design can no longer be primarily understood as just an instrumental tool that is, to some extent, conceived as an application from the outside for better reliability and process optimization. On the contrary, Transformation Design must have the aspiration of being transformative itself. It must, thus, act as a fluid and changeable operator in constant self-improvement. Involved in its evolution towards becoming an expression of transformativity sui generis are:

-

1.

design discourses and narratives of transformation in general (Prendeville & Koria, 2022),

-

2.

approaches to designing specifically for transitions and transformations (Coops et al., 2022), and

-

3.

design ideas stemming from the practical history of urban transformations (Hanson, 2001).

These are three distinct embodiments of interpretative self-reflections that can neither be reduced to each other nor simply “integrated” into a unity in the traditional sense, but rather coexist as parallel and sometimes even conflicting strands of conceiving design as transformative. Some theorists hold that the further evolution of Transformation Design towards “self-transformativity” – which has been a relatively recent development – should remain non-conclusive or even contradictory in itself for reasons of open creativity and vitality, since it will be, as Marco Van Hout put it, an evolution that is destined to occur essentially in a “post-design thinking era” (Van Hout, 2023).

The point of convergence: the transformative experience

Overall, despite differences in the self-projection of identities, methodologies, and goals, there is a certain consistency within – and basic coherence among – contemporary approaches to Transformation Design. Most of them circle around the fundamental term “transformation”; and this term, in essence, encompasses, in almost every case, what has been branded by contemporary social philosophy as the “transformative experience” (Chan, 2024). In its core, it is defined as an “experience that radically changes the experiencer in both an epistemic and personal way” (ibid.). Such experience can occur both to individual actors and systems; and it can be induced by either the skillful from-the-outside application of a tool to a process, or by the very character of the tool itself, which impacts what is done with it.

Design in which sense exactly? The case of designing systems

If transformation is, therefore, a complex and sometimes shapeshifting term, the second component of “Transformation Design” – the concept of design – seems to be it in no less a form. Over the last couple of years, the term “design” has become fashionable and en vogue, perhaps even too much. By now, basically everything is being – or can be – called design. Often, the term is added to another concept as a cheap suffix. At the same time, the methodological part of what “design” exactly is, does, and should do remains underdeveloped, particularly when it comes to its exact application to the social sphere. Most of the contemporary academic work invested in the term “design”, especially when connected in various ways to the term transformation, points towards exemplifying its role as some sort of practically useful systemic tool. Nevertheless, in recent years, a certain amount of work has been carried out on a more complexity-oriented methodological pluralism in systemic design, and the respective references are important if both the terms transformation and design are to come together within given contexts, or even work together in efficient tandems appropriate to the circumstances.

As one of these recent attempts at clarification of the issue, Birger Sevaldson in 2022, building on previous analyses since the 2010s, defined systemic design as “designing complexity” and as “practice of systems-oriented design” (Sevaldson, 2022). In his work, which can be regarded as foundational for a specifically contemporary understanding of Transformation Design, Sevaldson explores the methodology and practices associated with Systems Oriented Design (SOD) (Systems Oriented Design Network, 2024). According to Sevaldson, SOD has, in itself, complex roots (Sevaldson, w.y.) and is thus destined by its very character to address complexity in design processes (Sevaldson, 2013). Sevaldson argues that SOD is essential for navigating the inherent complexities in contemporary design challenges (Sevaldson, 2013), but also that Systems Oriented Design may help democracy, which can also be regarded as a system to work more efficiently and thus manifest a “healthy” status to its citizens (Sevaldson, 2022a). A more efficient SOD may help to counter inner polarization and disillusionment with politics.

From a closer perspective, the principles of SOD try, in essence, to integrate systems thinking into the design process, enabling designers to understand and tackle multifaceted issues more holistically and within a structural long-term perspective. For this purpose, Sevaldson provides a comprehensive overview of the tools and frameworks used in SOD, including inter- and trans-disciplinary mapping techniques and stakeholder analysis, which help identify interdependencies among social sectors and leverage multiple perspectives in problem-solving. Overall, Sevaldson emphasizes the importance of adopting a systemic perspective to generate effective and sustainable design solutions across various domains, from environmental design to social innovation. By highlighting case studies where SOD was applied, his work illustrates how SOD facilitates the design of systems that are not only functional but also resilient. Additionally, Sevaldson discusses the role of the designer as a facilitator in collaborative processes of transformation, encouraging active participation from all stakeholders involved. The aim is to empower designers to create “horizontal” solutions that are adaptable to changing conditions while fostering an understanding of the complex relationships between various elements within a system (Sevaldson, 2022). Overall, Sevaldson’s work has contributed to the growing body of knowledge on systems-oriented practices in design, encouraging practitioners to embrace the complexities of the post-postmodern world for more impactful outcomes.

Along similar lines, Sevaldson, Haley Fitzpatrick, and Tobias Luthe in 2024 tried to advance these ideas further by sketching a “systemic design approach for place-based sustainability transformations” (Sevaldson et al., 2024). Here, they presented a comprehensive examination of methodological pluralism as a crucial approach in addressing sustainability challenges through systemic design, arguing that employing a variety of methodologies enhances design practices by allowing for an appreciation of the intricate specificities and interrelations within local contexts. The approach particularly emphasizes the need for a systemic design approach that integrates diverse frameworks, tools, and perspectives to effectively facilitate sustainability transformations at the community level. The guiding hypothesis is that different methods can be tailored to fit specific challenges, thus fostering meaningful engagement with local stakeholders who are not always sufficiently considered, thus harming sustainability. According to the authors, successful interventions are, in general, inter- and trans-disciplinary in nature, which makes them more holistic; and this allows for “transversal” collaborations which can lead to more effective, responsive, and co-creational design outcomes. The authors hold that to achieve “place-based sustainability transformations”, it is of particular importance to align design processes with the values and joint aspirations of the respective community (Sevaldson et al., 2024), ensuring that solutions are culturally relevant and contextually appropriate for its members. Furthermore, by advocating a more pluralistic methodology, the structural uncertainties inherent, by necessity, in sustainability efforts can be better faced because pluralism diversifies the answers, ultimately contributing towards improved chances for long-lasting societal changes.

Last but not least, Marie Davidová, Maria Claudia Valverde Rojas, and Hanane Behnam in 2025 tried to develop an understanding of “Transformative Design” as an approach of “co-designing more-than-human ecosystems within social and environmental systems” (Davidová et al., 2025), thereby emphasizing not only the potentials of pluralism and heterogeneity, but also of dynamizing them through “gamification”. In essence, the authors investigate the concept of co-designing ecosystems that extend beyond mere human interaction (Davidová et al., 2025) to encompass social and environmental mechanisms. According to them, in order to progress to a successful, i.e., contextually embedded Transformation Design, it will be necessary to leverage gamification strategies to engage diverse, particularly young stakeholders in socio-ecologically healthy decision-making processes. This is not least due to the growing impact of the entertainment-driven attention economy and the influencer and gaming industries on the everyday behavior of younger generations. Davidová and colleagues emphasize the significance of fostering collaboration among human and non-human entities (Davidová et al., 2025), as the complexities of modern environmental challenges require multi-faceted approaches. By integrating AI- and, more in general, algorithm-driven game mechanics, Transformation Design can gain attention and likeability, and, as a consequence, can aim to enhance user participation and awareness, ultimately leading to more informed and memorable choices regarding sustainability. Furthermore, gamification can create immersive experiences that inform users about the impacts of their actions on the environment in impressively experiential yet non-dangerous ways, thus adding another level to the “transformative experience”. Overall, the study performed by Davidová’s team demonstrates the potential of technology-sustained participatory design as a means to achieve social innovation, advocating gaming methods that empower communities to actively participate in ecological stewardship. Designing more-than-human ecosystems can encourage so far non-participating sections of the population to become stakeholders in the adaptability of Transformative Design within the ever-evolving socio-ecological landscape.

System orientation as transdisciplinarity in action

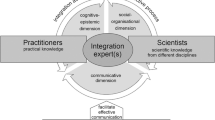

Summing up, in present times, the unifying goal of the various approaches to Transformation Design has become a more systemic and, at the same time, instrumentally and ideologically open orientation of both its main components, transformation and design. The objective is to master an ever more complicated, i.e., disrupted and interconnected reality by consciously applying a plurality of existing and emerging methodologies that is as diverse as possible in order to allow people and communities to constantly adapt to the fast-moving contexts of contemporary transformation (Miller, 2018). Besides a variety of other implications, effects, and consequences (Kang, w.y.), such an open-minded approach makes Transformation Design an active part of – and creative element in – the above-mentioned re-globalization and glocalization processes. It enables it to serve as a trans-systemic steering option between the Scylla and Charybdis of “twin globalization”. Furthermore, it ultimately makes it an attempt conceptually close to, but not identical with, the nascent discipline of anticipation as such (Poli, 2019; Miller, 2018). Given all this, contemporary Transformation Design can, in principle, be interpreted as a complexity-oriented approach to realize and put into practical action the “Charter of Transdisciplinarity” launched by progressive pioneers in June 1994 (CIRET, 1994), which in 2024 celebrated its 30-year anniversary with widely unbroken intellectual attractivity, verve, and vigor (University of Florence, 2024).

The framework for an encompassing view: the 6+4 Model

Summing up, the characteristics and role of Transformation Design in our time suggest that in order to realize it, it will be crucial for both the system as a whole and its specifics to be considered equally, although this is, per se, a complex endeavor. Here, one has to distinguish between the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels of relevance. Also, we should keep in mind that the macro-civilizational framework we experience today might be one that, in its archetypes, will probably persist well into the 2030s and perhaps even until the middle of the century.

In our view, an innovative framework of reference which can form the basic pattern for the present and future work of Transformation Design under contemporary conditions consists, in the very first place, of a revolving circle between nature and society. In their interplay, be it harmonious or conflicting, all human history has evolved, all values have been produced, and it remains the defining relationship for basically everything to come. Within this circle, the human world, including its activities and self-understandings, consists of a number of fundamental realms which differentiate themselves from each other and can be reduced to a woodcut-like typology of six archetypes. These six societal “field archetypes” have been dominating societies since the start of the era of modernity, characterizing them both trans-civilizationally and meta-systemically, i.e., in both democracies and autocracies alike. Amid increasing dynamism produced by the modern mobilization of history, the six archetypes form a relational net that defines most of the “integrated diversification” of modern societies, making each of the six realms both a cooperative part and a more or less autonomous or even self-governed actor in the greater whole of societies’ evolving process. The six realms, which each come with their own field logics, social mechanisms, and implicit value patterns, are (Benedikter, 2013ff.):

-

1.

economics,

-

2.

politics,

-

3.

culture,

-

4.

religion/spirituality,

-

5.

technology and

-

6.

demography.

Each and all of these six dimensions constantly create, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in opposition to each other, sometimes to the benefit of all other realms, and sometimes in rather selfish ways, their own order patterns and conditions of resilience and transformation. They also tend to develop their own ideal and non-ideal imaginaries, i.e., implicit ethical blueprints about what transformation is and should be about, depending on the overall socio-historical circumstances, and contribute them to the overall process.

At the multiple intersections between the six dimensions, there are interwoven (active and passive) creative processes among, in essence, four types of actors or drivers (Steger, 2020). Globalization scholar Manfred B. Steger has, on multiple occasions and in pathbreaking writings, brilliantly described them as follows (Eurac Research, 2020):

-

people (embodied drivers of transformation),

-

things (material or objective drivers of transformation),

-

ideas (disembodied drivers of transformation), and

-

institutions (institutional drivers of transformation).

That makes it 6+4=10 impact factors altogether. These 10 are the creative forces of –and in –transformational processes.

Importantly, all of them are connected by a bio-socio-psychological nexus. This is a relational pattern that might be immaterial, but forms the strongest center of gravity that keeps the whole social system together in practice. The bio-socio-psychological nexus is both a mirror and generator of relations between the 6+4, and its moods and colors change constantly, thus both representing the situation and shifting the patterns between the 10 components. Sometimes reduced by empirical social science to “consumer mood” or “behavioral patterns”, it is much more than that since it generates its own realities, expectations, hopes, and fears, and in so doing changes the overall arrangement of the individual parts that form the system. The bio-socio-psychological nexus is a sort of invisible continuum between the material, the communitarian, and the immaterial drivers of society, which is best studied by “contextual political analysis” (Goodin & Tilly, 2006).

Seen in its “existential” reality, this overall process occurs without any precise order, and in principle and per se, does not pursue any precise goal, nor is it “directed” at a given or predetermined space or time of arrival or completion. Not all of its fields and actors are of the same impact at all times. Although all of them have to be taken as, in principle, of equal structural importance and value for the evolution of the whole, some of the dimensions and actors might be more influential and have a certain lead over the others in given moments in time, i.e. historical eras, as the latter are always characterized by the predominance of a selection of fields and actors.

If the productive circle between nature and society, the six typological archetypes or field logics within it, the four types of actors’ logics as transversal drivers or “free actors”, and the bio-socio-psychological revolving center are combined, a clear yet highly complex guiding image of how transformation works in our time is drawn. It is an image that, first and foremost, can teach what factors not to forget in analysis, or what to explicitly include in the overall consideration to grasp complexity in all of its main components. The hypothesis here is that for any proper understanding and analysis of current transformation processes, it is important to work with the whole picture of the complete “6+4 model”, not just with parts of it, as is often the case in overspecialized social analysis, since leaving out just one element would undoubtedly lead to reductionism, thus inviting one-sidedness or even bias. Since reductionism and simplification are the main mechanisms used by populism and ideology, using the 6+4 model holds a certain promise to relativize or even overcome both, although this expectation should not be overstated.

The complete 6 + 4 system – which, in reality, should be read as a 2 + 6 + 4 + 1 living pattern – can be depicted as follows (Fig. 1):

A closer look: The circular laws of 6 + 4 interconnectivity

A closer look reveals some further laws within the model. These laws, or functional mechanisms, seem to be auto-produced, e.g., aspects of “autopoiesis”, i.e. self-organization of the system.

A first law is that of the spaces of activity and limits of validity of the (in total) 10 components. In times of hyper-connectivity, liquid modernity, and post-formality, it is basically impossible to restrain the four types of drivers within their sectoral borders or isolated decisional mechanisms, let alone hinder them from interacting more freely with all six typological dimensions of society. A certain restriction may apply only to institutions. Consequently, the full complexity of transformation in the highly differentiated societies of our time is, in principle, always the result of “6+4”, be it in implicit or explicit, obvious or tacit ways, or be it camouflaged (for example, by propaganda) or openly visible (for example, when science makes activities transparent). Change in our time is the result of the interactive mutual impact of the four actors/drivers and the six dimensions upon each other, thereby touching on – and at the same time being fed by – the bio-socio-psychological nexus, while being constantly embedded into the revolving circle of nature-society. This produces a variety of sub-processes that oscillate among their constituent elements and often touch on pre- or non-normative realms, since many of the resulting emerging realities are created anew or previously unknown.

Second, some dimensions and actors/drivers are, at least temporarily, more important for the ongoing overall transformation process than others. This is because there is systemic equality but structural difference between the components of the system. This means that while all six dimensions and four drivers, embedded in the circle nature-society and kept together by the bio-socio-psychological nexus, are, in principle, of the same value for the system, and none of them can be missed or left out from any meaningful analysis. Nevertheless, structurally speaking, some of them always tend to take the relative lead over the others within a certain historical timeframe, and such dominance might alternate according to historical cycles.

For example, in the Cold War era from 1947 until 1991, economy and politics were, according to most analyses, the most impactful of the six typological dimensions, with institutional and embodied actors (people, i.e., charismatic statesmen) as those dominating the others. In that era, society – in the form of the dialectic between state capitalism (communism) versus private capitalism (democracy) – was decisively more in the eye of transformational leaders than nature; and the bio-socio-psychological nexus reflected the split and highly militarized mood of the times. Yet, after the collapse of the East-West conflict in 1991 and since the beginning of globalization, fundamental demographic shifts, with the Global North declining and the Global South increasing their populations, as well as the rise of the internet and computing ecosystems in the 1990s and then, since the 2010s, those of AI, Chatbots, Blockchain, Fusion technology and Quantum computing, have led to a constellation where the two typological dimensions of demography and technology (and their manyfold ramifications and implications, such as migration and fake news) have established the relative dominance in the interplay of the six dimensions, with now material/objective and disembodied/idea-driven actors as the relatively most influential ones. In this era, due to climate change and the planetary environmental crisis, the focus has shifted from society to nature and has created a more balanced view of their interrelation, mirrored in the mood of the times, that, while primarily occupied with demography and technology, also incorporates the planetary perspective on nature much more into the overall consideration of transformation than previous eras.

This historical alternation in the combination of dominant factors is probably not the last one, but is destined to continue amid new historical turns. This would suggest that there are, to some extent, circular movements among the 6+4 elements of the system of transformation, reflected – and fed by – the circle of nature-society and the bio-socio-psychological nexus. It would mean that after a certain period of time, during which one combination of elements had the lead, another combination within the system of 6+4 will take the lead over the others, and so on. The constant mutual replacement of temporary predominance among the dimensions and drivers could even be regarded as one basic law of the historical process itself, as it, over longer periods of time, seems to occur in a rather similar way to transformation in the narrower sense. Nevertheless, neither exact sequences nor combinations regarding the transformative predominance of elements can be precisely predicted. Whoever claims that would be misleading, since history, as the encompassing larger vessel of transformation, is full of the unpredictable, improbable, and even impossible, regularly transferring its surprises to the realities of transformation on the ground.

Political implications

Seen as a whole, all this, similar to history itself, has to be viewed as both “serious and playful” process and, as may seem obvious, taken with a grain of salt when it comes to the details depending on contexts and circumstances. Nevertheless, the political implications are serious and manifold, and many of them seem rather direct. Attempts towards deglobalization (Garcia Arenas, 2018), which increased both in number and depth in the 2020s, have not changed the fact of the high level of interdependence of local to global sub-systems, such as of the financial, trade or migration systems on their different levels of application. It is the contradiction between weakening macro-interdependency and simultaneous meso- and micro-interweavement (Benedikter, 2021) that, for a couple of years now, has been throwing international institutions into crisis, primus inter pares the United Nations and its sub-organizations, such as the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) or the UN Commission on the Status of Women (UN Women). All of them are imbued in processes of internal polarization between democracies and autocracies and resulting paralysis (UN News, 2020), presenting their own need for fundamental transformation (Hathaway, Mills & Zimmerman, 2024).

In addition, due to the pluri-disciplinary characteristics of basically all important contemporary problems of the times, governance approaches are changing at a rapid pace towards trans-disciplinarity, partly independent of the specific transformation of their underlying political and social systems (cf. United Nations, 2020). This causes a new level of trans-sectoral and inter-systemic complexity sui generis which, due to the unavoidable lack of experience, is still barely handled by national and local communities, let alone by single actors on the different levels of policy. The resulting necessity of intensified non-traditional interconnectivity has given birth to new approaches for handling complex change. These include, but are not limited to, cultural diplomacy (Institute for Cultural Diplomacy, 2024) and science diplomacy (European External Action Service, 2022) as proposed by the 2021-founded United Nations Unit on Non-Traditional Diplomacy UNTRAD (UNU-CRIS, 2021), situated at the United Nations University’s Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies UNU-CRIS (UNU-CRIS 2024).

The respective ecosystems and networks are still underdeveloped but are likely to become core constituent parts of any future Transformation Design. This need is due to the recent regressive interpretations of “embodied” transformational leadership, which have revived the politics of the “strong man” around the globe, including China, Russia, Africa, Latin America, the U.S., and some EU countries, decreasing the role of international laws, rules, and formal and normative procedures. In the framework of the recent historical turn towards new “Cesarean politics” (Sata & Karolewski, 2022), transformational complexity is often met with logics of simplification based on generalization rather than with strategies of well-balanced trans-disciplinary management. However, we need the latter to become able to face wicked problems (Stony Brook University, 2024), including the unconventional finding of ways to spot (usually widely fragmented) “still-weak signals from the future” from early on, i.e. in due time (Poussa & Ylikoski, 2025).

A main trajectory of contemporary Transformation Design: Designing unpredictability

Last but not least, embedded in such a volatile (and sometimes confusing) framework as further drivers of change are, again as parts of the currently co-dominating technological dimension of society, the data-extraction economy and its orifices in information trading. Particular importance has acquired since 2022 the various, geopolitically competing and rapidly spreading forms of “chatbot integrators” of information pluralism. Tending to the universalization of the algorithmic and the virtual, these “emerging radical tecno-transformers” (Linturi & Kuusi, 2018) are triggering socio-cultural changes of still not fully foreseeable depth and bandwidth. For example, they are reducing pluralism in the behavior of users of search engines, thereby creating challenges at the human-machine and natural intelligence vs. artificial intelligence interfaces on an unseen scale (Benedikter, 2023b).

The dominance of new technologies such as AI chatbots is also in the process of creating a new form of the “disembodied” typology of drivers, which, not in line with Steger’s fourfold system, is no longer about ideas or ideologies, but rather about the immaterial becoming its own ideological force in the form of abstract entities such as chatbots. These are neither institutional nor embodied nor material, but seem to have acquired something of all these categories while not belonging to any of them. To this structural “hybrid immaterialization” also belong the foreseeable end of cash and the virtualization of finance, as cryptocurrencies are aiming at becoming the new world “reserve currency” system. Taken together, the trend from the intangible to the immaterial seems to be encrypted in the very basic code of universal technologization. Although this development was, to some extent, predicted by forward-looking intellectuals such as, for example, Jean-Francois Lyotard as early as the middle of the 1980s (cf. Centre Pompidou, 1985) and is nowadays taken up by post-postmodern reflection, the non-physical and immaterial dimension of transformation is growing at a pace at which the material is left behind, and attempts at anticipation are entering a fog of intangibility which makes conscious Transformation Design more difficult, if not more improbable.

In sum, the profoundly transient and ephemeral nature of today’s change ensures that transformative processes become more unpredictable, despite the fact that there are probably more practical instruments at hand than ever before. In these conditions, the effectiveness of transformation governance, based on (but not limited to) shared power projection, the non-violent negotiation and discursive balancing of interests (Habermas, 1991), and, in the ideal case, the cooperative redistribution of potential gains, has not kept pace with the depth and speed of open and post-formal multi-level transformation. Most importantly, actions of political, social, economic, cultural, and religious actors in the 2020s have reduced the mutual international permeability for knowledge access and the respective primordial trust network. Thus, global interrelations have become less transparent and readable, not least because real-time media-proliferation processes have become ever more ideologically splintered, competitive, and interpretation-driven, thus producing a mass of conflicting over-information and thereby making the manageability of realities on the ground rather more difficult than easier. Resulting knowledge conflicts and power shifts regarding access to know-how and advanced technology indicate that self-projected “lonely winners” (Garton Ash, Krastev & Leonard, 2024) use the current “deep” transformation processes to emerge, but also that existing transsystemic models of cooperation are being questioned due to selfish projection bubbles which could ultimately lead to de facto global dysconnectivity unsuited for a time of unprecedented acceleration of innovation.

The challenge of creating trust in times of VUCA and BANI: the core prerequisite for positive cooperative transformation

As a result of these conditions, the five procedures of contemporary change-steering:

-

1.

horizon-scanning and scouting,

-

2.

classifying phenomena according to the 6-4 model,

-

3.

integrating the conflicting and the non-aligned,

-

4.

comprehensive strategy-building, and

-

5.

practice

must be precisely applied and eventually brought to the point where they smoothly interact in order to master such a difficult framework. A softening factor at their intersection, suitable for smoothing the transitions between the five procedures that are often too harsh, is the advancement of a primordial culture of trust based on some sort of neo-humanistic thought, such as “resonance” (Rosa, 2019). In the age of over-complexity, the term resonance between the actors is regarded as one core prerequisite for communitarian transformative progress by many thinkers. It is a description of deeper communication and consequently demanded as a founding requirement in relevant networks of change and development. The goal is, as for example social philosopher Hartmut Rosa puts it, to master “uncontrollability” by “the politics of resonance” (Rosa, 2020), which consist in questioning our “relationship to the world”, in order to ultimately create a “resonant society” (Rosa, 2023) as the democratic answer to an ever-transforming globalized civilization.

It is plausible that the cultivation of such an approach today needs a much higher degree of contextual understanding than in the past, as well as a particularly “resonant” sensitivity to trans-sectorial noises and nuances at the overlap between the six dimensions and four drivers. Although contemporary change, as said, is imprinted especially by the dimensions of technology and demography, all six dimensions and four drivers and their respective institutional and contextual political actors are faced with substantial VUCA-levels (Togan, 2025) – i.e. with high degrees of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity which impact transformation processes not only in their physical realities, but also in their bio-socio-psychological cloud. In certain phases, VUCA sometimes, dependent on temporary situations of emergency due to the combination of negative factors, or “black swans” (Taleb, 2007) – may lead to the extreme form of BANI, i.e., the perception of transformation processes as brittle, anxious, non-linear, and incomprehensible (Giangiacomo, 2024). On the other hand, the activation of the bio-socio-psychological nexus often leads to conscious counter-movements, namely the voluntarily positive reinterpretation of VUCA as the chance for better vision, understanding, clarity, and adaptability/agility (VUCA World, 2024). It is exactly the latter, positive interpretation to which Transformation Design must be dedicated if it wants to be a pro-active factor in society – which, however, may sound easier than it is.

Given such a spiraling evolutionary context of elements, enterprises try to balance the weaknesses in their organizations through the trust-related development of highly trans-disciplinarily structured “business ecosystems” in order to increase stability by creating more pillars and to maintain their innovational fervor by cultivating “improbable partners” as creative hubs. As a result, technology-driven socio-economic ecosystems all over the world – not limited to Silicon Valley or Tel Aviv – continue to function well despite VUCA or BANI, the more effectively they are transdisciplinarily structured and trust-related, because investors, providers of ideas, and start-ups stimulate each other on cross-sectorial and – as much as possible – informal bases beyond their domains of specialization. In contrast, many all-too-traditional businesses that still focus exclusively on disciplinary specialization lack the respective cross-border innovation within their models and thereby fall behind more multifaceted and flexible ecosystems – as demonstrated, to mention just one negative example of the mid 2020s, by the German car industry, characterized by a strong sense of internal competition and a high degree of traditional specialization. Yet, in order to generate new impulses, businesses and decision-makers at large now must venture beyond their own limitations into different, sometimes completely opposed realms in order to reintegrate inspiration into their often all-too-rigid, self-referential, and secluded organizational habits and cultures. With this need, a decisive field of transformative action and leadership is described. It is exactly here where Transformation Design should come into play and should, in the ideal case, serve as a force of transdisciplinary revitalization and renewal, in the ideal case by using the 6+4 model of reference as blueprint for “pluriversal” action.

Teachings of the turn to inter- and trans-disciplinarity: Transformative readiness cannot be just a sectoral goal

Overall, due to persisting threats of VUCA, not to speak of – probably recurring – phases of BANI, non-solvable conflicts and tensions have become the new normal in economic, political, social and communicative contexts alike. In response, coping mechanisms by means of strengthening trans-disciplinarity and trust to foster stability and continuity apply to business models as equally as to multi-level governance and policies. Governance today is faced with the challenge of recognizing the profound complexity of change processes and contexts. Thus, Transformation Design, when employed with the idea of cultivating “resonance” as the embodiment of trust among the fields and actors to create the prerequisite for positive change, needs to undertake two steps first and foremost:

-

firstly, make the goals of transformation transparent and the subject of a broader dialog among specialized sectors;

-

secondly, apply an adaptable methodology of transformation which operates by the idea of interrelated ecosystems according to the 6+4 blueprint – i.e., considering economic, political, cultural, religious-spiritual, demographic, and technological sectors, and involving people, things, ideas and institutions. In the ideal case, all of them reach out beyond their disciplinary or habitual identities and narrative borders. Transformative Design must contextualize the process according to the needs on the ground.

After what we have seen, the reason for the crucial importance of these two steps is obvious. Competitiveness and wealth creation (in the economy), stability and continuity of development based on participation, justice and fairness (in politics and the societal order), creativity and basic coherence of values (in culture, understood in the broader sense), respect and tolerance (in religion and spirituality), fecundity and intergenerational cohesion (in demography), modernization and efficiency (in technology) and, in general, quality of life (in society) are major overarching objectives of Transformation Design. In contemporary societies, these objectives are all closely interlinked and interdependent on each other. They include a multitude of conflicting sub-goals on all levels of development, which are also interrelated. It is therefore important to recognize that many disciplinary models of transformation tailored for specialized sectors that have existed since the 1980s and the start of modern-day globalization in the 1990s have become at least questionable. It is time to start interlinking the major goals of reasoned transformation in serious and lasting ways.

Given all this, it becomes obvious that Transformation Design cannot remain an isolated goal of single sectors, not even when they include some inter- and trans-disciplinary elements in their own reasoning. Rather, it must conceive itself as a comprehensive strategy for strengthening interconnectedness and pursuing consciously transversal goals both within societies and among societies, including different political, economic, cultural and social sub-systems, and ultimately also comprising different ideological sides by pushing a series of lowest common denominators. To this end, a culture of prioritizing internal and external networks is needed that makes it possible to introduce conflicting goals into a joint, yet positively heterogeneous transformation process, which also explicitly anticipates potential undesired consequences. Over the coming years, procedures understanding transformation as relating macro-change to regional and local development by “glocalization” must be seen as a priority (Blatter, 2025). Leaders must not ignore examples of failed transformation due to the insufficient consideration of “glocalized” integration efforts – including stagnating economies, frozen conflicts, or even failed states.

Similarities in the characteristics of transformations and futures: the hermeneutical circle of narration, anticipation, and realization

In sum, the intellectual, social, cultural, and political classes of today’s societies need to design change through systemic transformative design, i.e., by developing a complexity-adequate understanding and integration of the implications and perspectives of disciplines, sectors, areas, and actors involved. The crucial interdependence of 6+4 – economic, political, cultural, religious-spiritual, demographic, and technological dimensions of change involving people, things, ideas, and institutions – is palpable in basically all contemporary challenges, including the fundamental relation between sustainability and resilience. It makes transdisciplinary thinking and networked acting the unavoidable precondition of good transformative governance. Trans-sectorial thinking and acting help to overcome the conflicting goals of differing actors in order to manage the complex roots of common problems. This requires, first of all, a more pronounced ability to ask the “right questions” in order to cope with the origins, nature, and perspectives of contemporary change.

As becomes clear from all this, contemporary Transformation Design needs to be a lively incubator at the bio-socio-psychological nexus of dimensions and drivers. Obviously, this incubator cannot only work in – and for – the present. Given that transformation by its very nature always occurs directed into the “still-not” or the unknown, it must include an expertise and anticipation capability with regard to “futures”. Therefore, “futures thinking” (Benedikter, 2025c) becomes a primordial embodiment of the capacity of governing transformation. Such a “futures thinking” is nevertheless still developing as a systematic and philosophically grounded approach. It can thus be co-shaped by present generations while it has, since the 2020s, de facto already become a global priority for all societies which, in one way or another, cultivate transformation (ibid.).

This is mainly due to the above-mentioned technological and demographic changes, which, over the past years, have led to a notable ramification and interdependence of incoming unknowns. Since futures as the potential arrival spaces of transformation processes, are often constituted as self-fulfilling prophecies that strongly depend on narratives about possible, desirable, or expected situations in the “thereafter”, narration, anticipation, and realization have become inextricably interwoven under the conditions of contemporary transformation. This has proven to be particularly true when it comes to the rather new interconnectedness of sustainability and science with futures studies and futures research (cf. Benedikter, 2025b). It is manifested in the fact that the most important hubs for sustainability are increasingly interested in combining it with a more transdisciplinary and globally networked futures expertise, since sustainability must not least be achieved also through anticipation, which is always, by its own nature, directed towards the future. Therefore, hubs such as the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASVIS) are embracing major self-innovation projects such as the “Ecosystem Future project”, which started in May 2025, “to bring futures and long-termism stably into the public sustainability discourse” (ASVIS, 2025).

As in this example, Transformation Design now needs a better systematic integration of interagency between past, present and futures, as sketched, for example, in the so-called foresight diamond of Rafael Popper (Popper, 2008). This requires in primis the inclusion of three methodological strands:

-

1.

Proven scientific research methods of the social sciences, such as representative surveys, in-depth delphi interviews or discourse analysis;

-

2.

experimental futures research methods, such as the future ripples method, scenario building, weak signals search or horizon scanning, including a common-sense-based perspective on longtermism (Poussa and Ylikoski, 2025);

and

-

3.

generally useful creative methods such as brainstorming, mind-mapping, steelmanning, or storytelling.

It is indicative of the crucial importance of integrating the contemporary understanding of transformation with that of futures that some of the most renowned outlets on transformation that exist have created interfaces that try to include narration, anticipation, and realization. For example, the initiatives of the “Nature Futures Framework” (NFF) (Nature Futures Framework, 2025), brought forward by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in cooperation with the United Nations Environment Program, try to popularize such an integrative approach, including the creation of collections of scenarios at the Nature-Future interface (Springer Nature, 2025). Similarly, the Stockholm Resilience Center of Stockholm University is linking the transformative potential of resilience to “creating a set of illustrative narratives of futures” (Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2024). Meanwhile, publications such as the “Encyclopedia of the Possible” (Glăveanu, 2019) aim at bridging the gap between transformation knowledge and futures expertise by disseminating knowledge regarding their overlaps. To this responds, as just one example, the series “Futures” of the journal Nature (Nature, 2024), which uses science fiction to inspire practical transformation. The journal has, in the meantime, collected hundreds of useful examples. As a result, “designing sustainable futures” (Press & Celi, 2024) is being increasingly linked to futures imagination research.

Forward to diversification: transformation design vis-a-vis design thinking, speculative design, futures casting, futures staging, and futures design

These and similar – today still widely experimental, but highly fertile – initiatives are bringing together transformation and futures to form the new mantra of “transformative futures” (Light et al., 2022). This mantra can and should not claim to be the new mainstream in Transformation Design. But it could produce a rich harvest and a continuing dividend if it is properly included in the further theorization and application of Transformation Design as a whole, among other approaches. For example, it could strengthen and expand attempts at “Anticipatory Innovation Governance” (OECD, 2024) as one potential path of interconnecting transformation-oriented organizations with the “politics of the future” (Berten & Franke, 2022).

For such a task, the – consciously hybrid – approach of “design thinking” (Han, 2022) may offer some practical options. As mentioned, similar to “futures thinking”, design thinking is not yet a precise discipline, but remains a pre-scientific, practice-oriented and, in the first instance, trans- and pluri-disciplinary approach. It tries to identify complex issues and to provide some highly contextualized means of governance for them. In addition to the much-requested programmatic reduction of over-complexity by typologization (Mazlish, 2013), it tries to assist the translation of profoundly different perceptions of change into jointly manageable imaginaries, notions, and terms, and for this, it uses visualization and haptic devices like no other branch.

Visualization, by the way, is also the main strength of four more, rather new approaches to working with “transformative futures”: “Speculative Design” (Xiao, 2024), “Futures Casting” (Shamiyeh, 2024), “Futures Staging” (SCI-Arc, 2024), and “Futures Design” (Arts, 2023). All of them converge in aiming at providing tools for taming overcomplexity and linking it with creative imaginaries. “Speculative Design” and “Futures Casting” are quite similar, as they are both dedicated to “rehearsing” a variety of different options unfolding with one narrative about a potential development by imagining scenarios and tailoring them to present needs and expectations. In this, both work like a theater rehearsal, which tries to find the suitable actor for a defined role without immediately deciding on one specific candidate, since every single one of them manifests its strengths and weaknesses regarding the required role. “Futures Staging”, then, can be thought of like the resulting theater event, where the focus is on the credibility and the realism of the representation. All of them together are often used for streamlining possible outcomes of change and to provide futures with a specific form and flavor before they are fully noted or go mainstream – an approach that, in an attempt at generalization, is called “Futures Design”.

Approaches to interrelated transformative practices: the key is progressive pan-resilience based on minimally converging notions of values

Considering these per se partial yet inspiring tools as auxiliary instruments for working with change, Transformation Design has little other option than to conceive itself as something like their converging path. It is, then, about interfacing, connecting and bridging processes of transition by mutually inspiring businesses, cultures, social spheres, civil actors, and (political) thinkers by the means of anticipatory narration and visualization. In this sense, Transformation Design must be considered, in quite “natural ways”, as being always also about “Imaginal Politics” (Bottici, 2014), including public imaginaries (Faessel, Falk & Curtin, 2020). Any Transformation Design of – and for – “the future” must therefore combine hard-core competence in governance with transdisciplinary methods of handling the imaginaries embedded in multiple uncertainties. Rather than just questioning a specific service or product innovation, it also has to address questions about the imaginal innovation needed as the underlying process.

The overall goal of such a procedure can ultimately be only one: to increase interdependent pan-resilience. Instead of just putting effectiveness before efficiency or dealing with the ability to “bounce back” to a given state of origin after a crisis, the more encompassing explorative – and thus clearly not normative – field of “Evolutionary Resilience” (Walker & Cooper, 2011) presents close relations to Transformation Design. The term “evolutionary resilience” has different meanings and is used in a variety of intents. With regard to transformation, it is not understood as the resilience of evolution, but as the (hopefully constant) evolution of resilience within and by the means of transformative processes. Evolutionary resilience looks at change as a dynamic process of permanent self-renewal in the sense of a system becoming stronger by experience. Heterogeneity requires flexibility in integrating both proactive and reactive components, which need to be interconnected and mutually adapted while in flux. The respective effort is not a one-night stand, but must be a permanent relationship while things happen, or in actu. This, in turn, will make it easier to cope with disruptive events and may help to prepare for unforeseeable occurrences.

The challenge of progressive pan-resilience-building, as mirrored in the idea and practice of evolutionary resilience, is crucial not only for good progress within contemporary systems but also among them. In particular, the interconnected evolution of value systems of differing strands of society towards a common pan-resilience has been strongly neglected over the past years. It has been poorly addressed both by theories of democracy and geopolitics, as well as by those regarding Transformation Design, with the latter often being conceived all too tightly and thus ignoring aspects of tacit relations implicit in value patterns. This is not a critique of the depoliticization of Transformation Design, which has occurred over the past years. It is rather a wake-up call for a rational awareness-building on the significance of values in transformative processes and, thus, on the responsibility that the management of them bears on a larger scale.

In our experience, one minimal, very basic common ground with regard to the future co-existence of different or even opposed value systems within processes of transformation could indeed be how actors interpret the strategic key transformative term resilience and its projection towards pan-resilience. On the one hand, it has been understood as the ability of a system to “bounce back” to a status of origin or status quo at any given moment in time, which is certainly part of the transformational process. On the other hand, resilience has been interpreted as sustainable relation-building in the sense of a transdisciplinary bundle of measures dedicated to fostering evolution towards something novel, yet, to some extent, common in perspective. As experience teaches, this novel state is often created by the dialog about which values to pursue between “improbable partners”, i.e., by those who are unknown to each other or come from profoundly different sectors with different value traditions.

The benchmark: Cooperative Transformation Design for the pan-resilience of complexly evolving ecosystems

Thus, Transformation Design in our time can be understood as a shared procedure of fostering creative interconnectedness, which pursues the goal to better manage the relation between resilience and sustainability according to some minimally shared values. Those values, in order to be minimally common, do not necessarily have to mirror actual presents, but can be just projected ones into unknown futures. Transformation Design, then, is about reconciling projections with values. It can be understood as a dynamic process-steering towards positive systemic evolution around cooperational patterns that take into account (and safeguard) the specifics of identities, histories, and worldviews, as represented in values. Looking through this lens, Transformation Design would also mean safeguarding stability, reliability, and liability, and prioritizing trust through the respect for the value patterns embedded, consciously or unconsciously, in the economic, political, cultural, religious, demographic, and technological developments of the times.