Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive integrative review of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and organizational change, an analysis crucial for understanding the evolution of these concepts. While both the concepts individually date back to the 1970s, it is only in the late 1990s and early 2000s that these gained prominence together. The primary reasons are the vicissitudes in economic systems across countries, changing demands in the workplace, and evolving roles of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), leading to organizational change in HEI research being largely fragmented. This study acknowledges the current forces at work and the advancement of management research on organizational change in higher education institutions (HEIs). Performance and content analysis are offered by including citations in Scopus’ multi-disciplinary database over the last 25 years (1999–2024). VOSviewer and Bibliometrix R were employed to generate visualizations of the bibliometric networks. The systematic synthesis of published research has identified thematic areas and emerging trends, providing a roadmap for future research directions in this interconnected field and the sustainable development of HEIs. This study’s findings hold significant implications for future research in the field of higher education institutions (HEIs) and organizational change. The results advocate for a comprehensive approach in future research, suggesting the application of established Organizational Change models alongside the development of new models to explore and document the change process within an HEI. Steering points are suggested to organizational change practitioners and higher education policymakers regarding managing change and further developing HEIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have been considered pivotal in transforming societies through imparting education (Brennan et al. 2004; Labanauskis and Ginevičius 2017; Aubry et al. 2021). While the conventional role continues to be played, academics and other key stakeholders are increasingly apprehensive of the impact of privatization and other external pressures on HEIs across regional and international contexts (Syed et al. 2024a; Boyce 2003), resulting in increased demand and stronger intent for transformation, which has ensued in organizational change in HEIs gaining prominence (Lozano et al. 2013). This has led to a rising interest in researching organizational issues such as culture, structure, and governance (Trowler 2008; Austin and Jones 2016) and comprehending the experiences and effects of organizational change within the domain of higher education (Marshall 2010; Syed et al. 2022).

Researchers have made various attempts to guide organizational change in HEIs, such as developing models and frameworks. For instance, drawing on his experience within an HEI, developed a dynamic organizational change model that focused on education, resources, leadership, policy, and advocacy. Furthermore, (Velazquez et al. 2006) proposed a four-phase model that enables the development of a sustainable university, encompassing vital strategic perspectives: campus sustainability, outreach and partnerships, education, and research. While such models and frameworks highlighted certain key aspects of organizational change in HEIs, they received criticism for not considering ‘processes of change’ (Stephens and Graham 2010). Also, (Aubry et al. 2021) posit that the ‘purpose’ of change should be considered and explicitly communicated to all the stakeholders of the HEI. In the last few years, one of the predominant purposes for organizational change in HEIs has been ‘sustainability’ (Sanjeev et al. 2024; Lozano et al. 2013; Blanco-Portela et al. 2017; Ferrero-Ferrero et al. 2018). While various case studies have captured the journey of organizational change in HEIs toward sustainability and the role of human factors involved, there is hardly any synthesis of research carried out in this area.

It is evident that ‘Organizational Change’ as a concept has become prominent in higher education in the last two decades (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017). The fragmentation of the research domain is apparent, as evidenced by over 2000 articles published and indexed in the Scopus database, none of which provide a comprehensive review and analysis to synthesize the diverse aspects and themes associated with organizational change and higher education institutions. Therefore, this essay investigates the following research questions:

RQ 1: How has the publishing trend in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and Organizational Change evolved over time?

RQ 2: What structures characterize the literature on higher education institutions and organizational change?

RQ 3: What are the probable future research directions on organizational change and HEIs?

Investigating the above research questions would help uncover not only the evolution of this research field through thematic mapping and content analysis, but also the integration of this interconnected research field.

Many scholars recommend bibliometric analysis because it enables researchers to not only achieve a comprehensive grasp of the existing literature but also synthesize it effectively (Cisneros et al. 2018). Moreover, current research trends and future avenues/directions of the research body could be identified using bibliometric analysis (Li et al. 2017). Furthermore, the structure and central themes of a particular research area can be ascertained through content analysis, along with bibliometric analysis (Tunger and Eulerich 2018). Most recently, this technique was adopted by Jiménez et al. (2019) and Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop (2019). However, their research work focuses on different areas within the higher education domain. While Jiménez et al. (2019) conducted a bibliometric review on technology and higher education (Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop 2019), it primarily focused on the sustainable development aspect of higher education. Motivated by their works, we conducted bibliometric and content analyses of published literature on organizational change and HEIs.

The originality of our study can be summarized as follows. Firstly, previous authors consider technology and sustainability as just two of the many factors or motives for adopting organizational change processes in HEIs. Our work is comprehensive and is not limited to any factors. To the best of our knowledge, no study has utilized bibliometric analysis to examine the expansion of the research field and to achieve the research objectives outlined in this work. Since the mid-1990s, when significant changes occurred in the organization of higher education, a comprehensive historical approach has been applied for 25 years. Cluster analysis, co-authorship analysis, co-citation analysis, and phrase co-occurrence analysis were all utilized. Table 1 summarizes prior research and emphasizes the differences from our study.

This work aims to contribute not only to theory but also to practice. First, research carried out on organizational change and HEIs in the past 25 years is presented systematically, providing an overall view of the research area. Second, thematic areas and emerging trends within the field are recognized and categorized in clusters, which aid in identifying future research directions of this multifaceted and interconnected field. Third, steering points are suggested to organizational change practitioners and higher education policymakers regarding the management of change and the further development of HEIs. The subsequent sections outline the research methodology employed, present the analysis and findings, and address the limitations and conclusions.

Research methodology

The process undertaken concerning the bibliometric analysis of published articles on Organizational Change and HEIs in the Scopus database is explained in this section. The initial task was identifying the most suitable database (Albort-Morant and Ribeiro-Soriano 2016). Scopus was chosen for many reasons:

First, the Scopus database has greater coverage of journals and articles than others, including Web of Science (Albort-Morant and Ribeiro-Soriano 2016). Second, a more comprehensive overview of global research output is provided in Scopus, which aids the origination of bibliographical research interests among academics and other professionals (Durán-Sánchez et al. 2019). Third, and most importantly, while many articles published on organizational change and higher education separately have been indexed in the Scopus database, no bibliometric analysis work has been carried out and published on organizational change and higher education together. This study aims to bridge this gap and encourage additional research on organizational transformation within higher education institutions.

The research framework of our Investigation is depicted in Fig. 1. Both content analysis and performance analysis are incorporated into bibliometric analysis. The study objectives were analyzed, and visual representations of bibliometric networks were generated using two software tools: Bibliometrix R and VOSviewer. Clusters derived from content analysis were used to ascertain the current state and future trajectory.

The topic search was performed in the Scopus database in early 2025 on similar lines to that of (Benomar et al. 2022; Durán-Sánchez et al. 2019). The data extraction from Scopus revealed a scarcity of papers from 1964 to 1995, with no apparent continuity throughout. Hence, the time frame from 1999 onward was chosen, as it coincided with a period of continuous and considerable publication output in this research field. An initial search identified as many as 2307 publications in 25 years (1999–2024). Furthermore, multiple filters were applied to obtain only relevant articles.

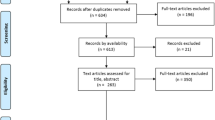

Step 1 excluded conference papers, book chapters, book chapters, conference papers, proceedings, errata, editorials, and reviews (618 papers excluded). Step 2 excluded papers published in languages other than English (97 papers excluded). Step 3 consisted of manual screening by the authors. Irrelevant publications were identified through the examination of the abstract and title, resulting in the elimination of 1111 papers. The 481 remaining papers were subjected to a bibliometric analysis. Figure 2 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram, which highlights the search strategy, data collection technique, and statistical summary of the research conducted in the field of organizational transformation and higher education institutions (HEIs).

Analysis and findings

This section addresses the research questions by incorporating content analysis (Ahmad et al. 2020; Shi et al. 2020; Bouckenooghe et al. 2021), keyword analysis (Syed et al. 2024b; McAllister et al. 2022), co-citation analysis (Menegaki et al. 2021), and thematic mapping (Syed et al. 2023).

RQ 1: How has the publication trend in Organizational Change and HEIs evolved over time?

The Scopus database was analyzed to address RQ 1 by categorizing publication trends in the field of Organizational Change and Higher Education Institutions over a twenty-five-year period by year and journal.

Publication by year

Figure 3 illustrates the timeline and volume of publications regarding organizational change and higher education institutions over the past twenty-five years. The consistent increase in the volume of publications evidences the growing acceptance of organizational change within the higher education sector, both in practice and research.

Publication in journal

The top 25 journals in Organizational Change and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are listed in Table 2 by total publications (TP). Additional factors to consider are the year of initial publication on this subject (PY_start), h-index, m-index, and total citations (TC). These journals were chosen not only because of the (TP) but also because of their impact (citations) on the literature development through the published articles. The leading three journals are Higher Education, Library Management, and International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education. Moreover, many journals in the table possess a Scopus Quartile ranking of Q1, which advocates that the top journals in management and higher education have picked up this field of research.

Higher Education leads the table with a total of 18 publications with an h-index of 13, followed by Library Management and the International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education with an h-index of 7 and 9, respectively. Variance in the order of the top 5 is noted due to the lesser impact (in terms of total citations) garnered by Library Management. In terms of m-index, Higher Education Research and Development leads the group with an m-index of 0.67. It confirms the steady growth of this journal regarding organizational change and HEIs despite having a shorter production timeline when compared to others who have been publishing for decades.

Further analysis suggests that the top five journals have witnessed a steady and gradual enhancement in the field of Organizational Change and HEIs. Among them, Higher Education and Journal of Organizational Change Management lead the list with sharp, inclined curves showing positive signs. Interestingly, the former has dropped from the ABDC rankings (2019) due to a lack of business angle in its publications, while the latter has retained its B ranking in the list.

RQ 2: What structures characterize the literature on Organizational Change and HEIs?

Conceptual structure

The primary topics that researchers have investigated in the field of Organizational Change within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are the focus of this study. The author’s keywords effectively encapsulate the article’s content, necessitating the implementation of keyword and co-occurrence analysis (McAllister et al. 2022; Singh et al. 2025). Keyword co-occurrence serves as an illustration of the interconnection of numerous concepts within an article (Kent Baker et al. 2020). Academics frequently implement co-occurrence analysis to distinguish and categorize data in the realms of business and management (Castriotta et al. 2019). Thematic mapping of this field was generated and illustrated using Biblimetrix R and VOSviewer. The primary subjects are depicted in Fig. 4.

The number of keyword co-occurrences and the proximity of subjects to the center of the network map and each other increased. Additionally, the extent of the sphere representing each topic increased in proportion to the frequency with which the authors utilized a specific phrase. Additionally, the bubbles and connections are distinguished by their respective colors, symbolizing the various clusters and their corresponding themes. The subsequent section on intellectual structure provides further insights into the pertinent components of clusters and their significance in the development of the field of study. Thematic mapping was employed to elucidate the numerous subtopics that authors have investigated over the past twenty-five years and to offer a comprehensive overview of the topic’s development (Figs. 5–7). Two cut-off points were established to partition the chronology into three periods, with an equal number of articles in each category. The subsequent subsections illustrate the conceptual development of this diverse domain.

Time period 1 (1999–2013)

The first time period (Fig. 5) saw papers focused mainly on topics such as the development of entrepreneurial universities (Ramaprasad and La Paz 2008) and leadership (Bryman and Bryman 2008). Etzkowitz (1998) had introduced the concept of the ‘second academic revolution,’ which illustrates the participation of HEIs in a region’s economic and societal development. Furthermore, it was during this period that sustained efforts to bring the industry and academia closer were observed, which resulted in the conceptualization of a ‘triple-helix model’ portraying the association of university, industry, and government (Etzkowitz 2003).

The immediate effect of these changes was evident in the emergence of the term ‘entrepreneurial university’ (Siegel et al. 2007; Ramaprasad and La Paz 2008) and the increasing number of university spin-offs (Etzkowitz 1998; Kirby 2006). These changes led to the education sector imbibing industry-oriented research goals and collaborating with the industry to conduct commercially viable research (Toole and Czarnitzki 2010). The paradigm shifts garnered much attention from academics to further research into related aspects such as collaboration (Boh et al. 2003; Mowery and Sampat 2004), academic entrepreneurship (Mars and Rios-Aguilar 2010; Grimaldi et al. 2011), and university patents (Mowery and Sampat 2005; Van Praag and Versloot 2007). This phase also witnessed scholars assessing the effect of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which was the foundation for the commercialization of research in higher education (Mowery and Sampat 2005) and the development of entrepreneurial universities (Syed and Spicer 2025).

Time period 2: 2014–2021

While the research theme ‘collaboration’ held its ground, newer research topics, such as faculty development, recognition, and social change related to organizational change in HEIs, began to emerge during the second period (Fig. 6). This was the period of increased emphasis on implementing a third mission in the business model of HEIs (Pugh et al. 2016). Furthermore, the concept of ‘entrepreneurial society’ was introduced by Audretsch (2014), indicating entrepreneurship’s significance in piloting economic development. Thus, a more inclusive approach is seen during the time period in contrast to the previous one, with an increased focus on governance and organizational transformation (Aubry et al. 2014a).

Another curious aspect in this category is the emergence of faculty development as a theme, mainly because implementing the changes in HEIs necessitated preparing employees through facdevelopment initiatives (Lozano et al. 2013). This period also marked the authors’ research focus moving beyond American borders and probing the changes in HEIs and the societal impact within European countries. (Philpott et al. 2011; Stam 2015) and Australian contexts (Sen and Cowley 2013), as these regions were experiencing changes in policy and mandates (Fitzgerald and Cunningham 2016). This phase also lays the groundwork for researchers to delve deeper into the micro aspects of organizational change, implementation, and governance.

Time period 3: 2022–2024

This time period (Fig. 7) saw a surge in the number of papers on topics revolving around sustainability (Ferrero-Ferrero et al. 2018; Žalėnienė and Pereira 2021) due to the impact of disruptive technological advancements and diverse societal demands, which necessitated a realignment of HEIs’ vision, mission, and strategy (Miller and Acs 2017). Additionally, numerous articles emphasize the importance of organizational culture (Williamson 2018) and technology (Fitzgerald and Cunningham 2016; Dalmarco et al. 2018). Over the past five years, there has been a notable improvement in the field of research, encompassing both general and specialized subjects. Furthermore, to improve their comprehension and communication of dynamics within specific contexts, researchers implemented case study methodologies to investigate the micro aspects of change, including resistance and individual actions (Diedericks et al. 2019).

Social structure

The social structure was derived from content analysis, the application of VOSviewer software, and the organizational and country affiliations of authors. Collaboration among scholars is a formal means of involvement in an intellectual association (Cisneros et al. 2018). Global collaboration networks enable countries across various geographic regions to contribute to knowledge development and advancement, despite developed countries often pioneering knowledge creation (Palacios-Callender and Roberts 2018). Collaboration yields a multifaceted progression of ideas due to the varied backgrounds and diverse disciplines of researchers (Tahamtan et al. 2016).

It is evident from Fig. 8 that the USA and the UK lead the bulk of the collaboration network, forming two major clusters. They are followed by the Netherlands, Germany, and Spain, leading the remaining three smaller yet-to-be-developed clusters. It is rational, as well as expected, because HEIs in these countries have undergone substantial organizational changes, and funding agencies based in these countries have been sponsoring research pursuits, enabling scholars to probe further into various aspects of organizational change in HEIs and publish the analysis of findings.

Table 3 further illustrates other characteristics of collaboration among corresponding authors based in various countries. In terms of network analysis, a higher value of a node’s betweenness implies a greater ability of the node to connect other less-connected parts of the network. The USA, with the highest betweenness value (208.92), leads the largest cluster of the network, signifying that it acts as the strongest connector or broker of knowledge flow within the network. Apart from the USA, the UK is the only country in the network with a betweenness value of over 100, and is followed by other Western countries. This implies that the flow of knowledge and collaboration remains concentrated within a few countries. However, the MCP ratio was determined to include newer countries in their due credit. The higher MCP ratio of Asian countries, such as China and Singapore, indicates that corresponding authors in these countries are more inclined to engage in collaborative research pursuits compared to those leading the table. This could also be attributed to the ‘collectivist’ aspect of societies in Asian countries, in contrast to the ‘individualist’ characteristics of Western societies.

Intellectual structure

The intellectual structure of a research domain can be examined by assessing the connectivity between influential articles and authors based on the number of citations, known as co-citation analysis (Singh and Malik 2022). The co-citation analysis displays the intellectual structure by grouping articles into homogeneous groups (clusters), which can also be recognized as essential themes in the research domain. The four prominent research clusters identified in the present co-citation analysis were created using VOSviewer, with a citation threshold of 5 and the option to remove isolated nodes. Papers in each cluster were studied to build a common theme (refer to Fig. 9), a conventional approach in bibliometric analysis research (Tian et al. 2018).

Cluster 1: How is the research being carried out?

This cluster comprises articles that primarily focus on the approaches and methods researchers adopt to investigate various aspects of organizational change in HEIs. Authors of papers within this cluster illustrate the motive and significance of employing methods such as case studies and other qualitative analyses (Wentworth et al. 2018). Regional and global perspectives of changes in practice and organizational policy within HEIs were also highlighted.

Cluster 2: Motives of organizational change in HEIs

Authors of papers within this cluster have discussed various motives pushing for organizational change, such as governmental policy and accreditation (Carroll et al. 2009), technology (Markman et al. 2005; Marshall, 2010; Wright 2014; Boh et al. 2016), innovation (Marshall 2010; Cunningham and Menter 2021), and sustainability (Velazquez et al. 2006; Blanco-Portela et al. 2017; Ferrero-Ferrero et al. 2018).

Cluster 3: Dynamics of / resistance to organizational change in HEIs

This cluster emphasizes the interplay of other meso and micro aspects, further influencing the change. These include people (Akin and Demirel 2015), diversity (Miller and Acs 2017), and culture (Eddy 2006; Žalėnienė and Pereira 2021). Additionally, the dynamics surrounding the direction of organizational change — top-down (driven by top management), bottom-up (propelled by employees), or a combination of both — have been extensively investigated.

Cluster 4: Leading organizational change process in HEIs

This cluster illustrates the role of leadership in the organizational change process. The key aspects of leadership and organizational leadership have been elucidated by Altmann and Ebersberger (2013), Hempsall (2014), and Žalėnienė and Pereira (2021). Furthermore, the significance of strategic planning and knowledge management in leading and managing organizational change in HEIs is covered by Papa et al. (2017), Al-Abri et al. (2018), and Fischer et al. (2021).

Discussion

This study’s thematic mapping of all the literature reveals context-specific dynamics as well as common patterns in higher education institutions (HEIs). Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) globally usually encounter similar internal issues, such as cultural resistance, siloed structures, and communication gaps, that may impede change (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017). According to our study, the factors that affect and cause change vary by region, customs, and government structures (Lee and Lee 2019). We now advance from a simple overview to a detailed and evaluative analysis of core items. Governance models, diversity and inclusion pressures, financing structures, and regulatory contexts affect organizational change across different world regions. We connect our work with prior findings (e.g., Lozano et al. 2013; Blanco-Portela et al. 2017) to situate our perceptions within the broader literature and research, and to inform a future agenda that is sensitive to global diversity in higher education systems (Forster 2018).

Governance and policy contexts across regions

Governance arrangements, as well as government policies, emerge as key factors that shape change within universities, differing significantly by both country and region (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017). Ministries or government agencies exercise substantial control over universities’ direction in more centralized systems, such as those found in many parts of Western Asia and Southeast Asia, directly steering organizational change through plans and national reforms. When these top-down approaches are aligned with specific geostrategic goals, they can enable rapid and large-scale changes. (Lazzeretti and Tavoletti 2005; Seeber et al. 2012). Several Western Asian countries, as a part of broader development agendas, have pursued aggressive modernization and “world-class university” initiatives, often encouraging government-industry-university partnerships and entrepreneurial institutional models. Alternatively, HEIs in North America typically possess greater institutional autonomy. Academic self-governance is customarily enjoyed throughout much of Western Europe. (Bleiklie & Michelsen, 2013). Even when still bounded by external accountability and competition, such as that in a market, and internal decision-making, these factors tend to drive the change that occurs in these settings.

For students and research funding, American and Canadian universities operate in competitive environments. This situation pressures them to innovate as well as restructure from within. Universities in Western Europe are mostly state-run and controlled. They have increasingly been granted more autonomy in their management roles, prompting reforms within internal governance to enhance responsiveness and efficiency (Forster 2018). Local governance traditions with policy frameworks shape the impetus toward change and the levers by which change may be implemented, so inter-country comparisons thus indicate that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to organizational change in higher education.

Governments respond to shifts in geostrategy by adjusting policies that influence higher education institutions (HEIs) across regions, such as those related to international rankings. Therefore, university transformation depends on state control and the degree of institutional autonomy. When comparing change strategies, our findings reinforce the idea that understanding a country’s higher education governance model is crucial, as the same reform may manifest in a significantly different way in decentralized systems, such as the United States or Germany, than in centralized systems, like Malaysia or Oman.

Diversity and inclusion as drivers of change

The evolving dynamics of student and faculty diversity represent another vital factor that reshapes organizational change processes in higher education institutions (HEIs) (Williams 2013). Institutional culture and practices must change in turn because universities grapple with demands related to greater equity, inclusivity, and representation across various contexts.

Long-term efforts to increase racial, ethnic, and gender diversity have emerged in North America (Bhopal and Pitkin 2020). Universities then worked to implement new hiring practices and curricula, such as incorporating diverse perspectives into support systems, to foster an inclusive campus climate. Such efforts often require organizational change and learning, such as creating units dedicated to equity and inclusion or training leaders in diversity competence (Knight 2015; Bendermacher et al. 2017).

Western European institutions vary by country, yet they face similar pressures increasingly – for instance, EU policies and funding incentives now encourage research teams to achieve gender balance and disadvantaged groups to have accessibility, so universities adjust their structures accordingly. Diversity dynamics suppose other dimensions within areas such as Western Asia and Southeast Asia. Many universities in these regions are rapidly internationalizing, bringing in students as well as faculty from diverse countries and cultural backgrounds (Phillips 2014). This international diversity forces institutions to adapt their student services, pedagogy, and governance to a more global constituency.

Additionally, some Western Asian HEIs include women as they ensure access in customarily male-dominated systems. This prompts them to create women’s campuses or revise codes of conduct and leadership pathways for inclusivity. Our review suggests that diversity with inclusion initiatives catalyze organizational change when they challenge established norms and prompt institutions to become more responsive to all stakeholders. Universities must evolve to reflect as well as serve diverse communities, aligning with their social responsibility and broader societal views (Lozano et al. 2013). Diversity is not simply a moral or compliance issue; it has been linked to improved innovation, better decision-making, and enhanced academic outcomes, which reinforces the importance of planned inclusive change management in HEIs. These dynamics remain understudied beyond Western contexts; therefore, future research should continue to examine the various forms of diversity (Žalėnienė and Pereira 2021). Diversity regarding culture, language, and socioeconomics particularly prompts or influences change at many universities.

Financial models and resource pressures

The financing model of a university – namely, how it generates its primary income – significantly influences its evolution and the reasons behind it. Universities face distinct change drivers under constraints. This is especially true for those working under varied financial systems. Higher education is primarily financed by many Western European nations and regions in Asia. The state now provides most of this funding. Substantial public financing can provide stability, as it enables long-term planning for change initiatives (for example, funding new programs or infrastructure; Jongbloed and Vossensteyn 2016).

However, governments rely on their budgets, connecting institutional change to political priorities and economic cycles. Austerity measures or shifting government agendas can then slow down or reverse reforms (Marginson 2018). Universities may be forced to downsize or reorganize reactively, rather than tactically, if others earmark public funding for specific outcomes or are subject to budget cuts. Conversely, universities in North America, as well as other market-led systems, depend significantly on tuition fees, private donations, and competitive research grants. This dependence strongly incentivizes organizations to change in ways that serve to improve efficiency, attract students through new offerings or prestige, and generate alternative revenue streams (Cunningham and Menter 2021). American institutions, for example, have widely adopted adaptive responses to deal with financial pressures, such as entrepreneurial activities that include startup incubators, online programs, global branch campuses, and corporate-style management practices (Naidoo 2018). Whilst these changes are fostering innovation, such market-responsive shifts also risk prioritizing revenue over academic values (Mok and Jiang 2018).

We observe hybrid financing models within emerging higher education systems in Southeast Asia and the West Asia region. Resource constraints can limit the change to be more incremental for others, especially those in developing economies.

Meanwhile, some institutions enjoy generous government support or endowment support (notably those within oil-rich Gulf states), which enables rapid expansion and the adoption of cutting-edge initiatives. According to Blanco-Portela et al. (2017), successful change is facilitated by adequate resources, as well as aligned budgeting, although ubiquitous barriers include financial strains. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of organizational change within HEIs should consider the economic situation, whether change stems from seeking additional funding or aiming for improved outcomes with fewer resources (Hillman 2016).

For further illumination of the finance-change nexus, future studies could usefully compare how financing reforms (such as introducing performance-based funding or increasing tuition) have impacted organizational innovation in different regions.

Regulatory and accreditation pressures

External regulatory forces, including national quality assurance frameworks and accreditation requirements, as well as global rankings, exert significant pressure on universities, often triggering organizational change (Bergan and Deca 2018). Higher education systems have implemented stricter accountability measures over the past two decades. Due to the Bologna Process in Europe and national frameworks for qualifications, universities were compelled to restructure their degree programs into cycles of bachelor’s/master’s degrees, adopt assessments of learning outcomes, and improve systems for credit transfer (Hou et al. 2015). These externally driven changes required a significant internal organizational adjustment, illustrating how international policy coordination can standardize certain aspects of university operations across countries.

Accreditation agencies can indeed be powerful drivers. These agencies act as drivers of change worldwide (Carroll et al. 2009). Accreditation standards typically require institutions to plan tactically and ensure effective learning processes. These standards, whether national or international, such as ABET for engineering and AACSB for business schools, also require faculty development with adequate resources. Universities frequently establish new administrative units, formalize decision-making processes, and implement consistent improvement loops to demonstrate organizational changes and maintain or achieve accreditation (Hazelkorn 2015). Such changes are reported throughout regions; for example, universities in Southeast Asia and the Middle East have sought US or European accreditations to strengthen their legitimacy, which has led to the adoption of Western academic practices and governance structures.

Regulators and accreditors may pose challenges, although they clearly benchmark and pressure for change. Rigid external standards may clash with local needs or institutional missions. Compliance costs can strain resources. External policy and quality mandates drive and bound the change of HEIs, as the literature identifies (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017). Our mapping suggests that institutions can successfully navigate all these pressures by proactively integrating quality improvement into their culture. It is not seen as just something to do. Continuous organizational learning normalization has been observed in regions with more mature quality assurance systems, such as North America’s accreditation tradition or Western Europe’s longstanding agencies. However, these mechanisms are still emerging in some developing systems, which can feel externally imposed through comparative perception. Future research may explore the calculated changes that occur as universities strive to enhance their global standing through participation in global ranking competitions and the adoption of new international frameworks, such as credential recognition.

Towards an integrated global perspective

Overall, our findings highlight that while specific themes change (such as the need for visionary leadership or the challenge of secure academic cultures) are common across the globe, a university’s change adventure is profoundly shaped by context (Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop 2019). Institutions in Western Europe and North America dominate documented literature on organizational change, maybe masking experiences unique to other regions.

This study contributes to the field by comparing it to other regions, such as Western Asia and Southeast Asia, which exhibit distinct characteristics in terms of high government involvement, rapid expansion, and quests for global visibility, unlike those in Western patterns. Theory and practice can significantly benefit from cross-regional perceptions (Kosmützky and Putty 2016).

These perceptions are important regarding advancement. Lozano et al. (2013) argued for sustainability and claimed that a holistic, system-wide approach is necessary for achieving it. Universities must undergo meaningful transformation to achieve it.

According to our analysis, which extends this concept, effective holistic change strategies must accommodate diverse economic, cultural, and governance contexts. Therefore, we echo the calls for more internationally comparative research on organizational change in HEIs. To shape change outcomes, future studies should examine in depth the interplay between government policy shifts, demographic changes (e.g., the rise of new student populations), and resource environments.

To develop a more inclusive global theory of change in higher education, longitudinal and cross-case research that covers underrepresented regions would be particularly valuable. Scholars critically compare, rather than describe. This way, they identify universally valid change management approaches, as well as context-dependent ones. University leaders, as well as policymakers, will craft subtle strategies through the use of such knowledge that acknowledge diversity while pursuing common goals of organizational innovation and resilience (Altbach and de Wit 2018).

A globally informed grasp of organizational change, incorporating views from all world regions, can improve both the academic literature and the toolkit for change in universities; this understanding fulfills our thematic mapping promise, setting a strong agenda for research.

Theoretical contribution and practical implications

The academic contributions of this paper can be summarized in some key points within the field of organizational change at HEIs. Firstly, the study gives a longitudinal as well as geographical mapping of research within this domain. It categorizes publications from the past 25 years by year, journal outlet, and country of origin. This thorough overview charts the growth trajectory within the field. It also highlights the global concentration of this research, confirming a surge in scholarly interest over the last two decades (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017). Because the review reveals that output is dominated by regions, such as the US and the UK, which lead in publication volume as well as collaboration networks, it underscores the international scope of HEI organizational change research while also pointing to a need for broader cross-country engagement to avoid regional silos.

Secondly, through citation analysis, the paper identifies influential and important works that shaped the development of this research area. Foundational contributions emerge as anchor points in the literature, as well as these contributions, such as Lozano et al. (2013) on advancing sustainability in higher education and Blanco-Portela et al. (2017) on the drivers and barriers of organizational change in universities, delineate the theoretical roots and dominant models that subsequent studies have built upon.

The study employs citation and co-occurrence network analyses to identify key thematic areas. It can thereby map the intellectual structure of the field for all. Bibliometric clustering reveals several prominent themes ranging from researchers employing research methodologies for study of change in HEIs, to the various motives causing organizational change (e.g. technological innovations, policy mandates, and sustainability initiatives), as well as the cultural dynamics of change (such as issues of organizational culture and stakeholder resistance) and the critical role leadership has in guiding transformations. These themes challenge central ideas noted in prior literature, such as sustainability driving change (Lozano et al. 2013), as well as working together to organize domain knowledge in a structured panorama.

Fourthly, the analysis examines the composition of research clusters and co-authorship networks, thus illuminating the current state of research pursuits and scholarly collaboration in this field. It depicts how researchers’ teams have gathered around organizational change topics in HEIs. It depicts the way these groups connect or stay relatively separate. Notably, our findings indicate that Western institutions dominate in specific thematic clusters and collaborations, reflecting the influence of North American and European contexts. This understanding of the pattern of collaborations emphasizes the need to foster more cross-regional and international research partnerships to improve and balance the field’s development. Ultimately, the review highlights several potential avenues for further inquiry and identifies numerous critical gaps within the literature that hinder integrative development across the research field.

Notably, it highlights the scarcity of primary and cross-national empirical research on organizational change procedures, as well as the absence of an accepted, comprehensive “roadmap” or framework for managing change within HEIs. In echoing the calls of contemporary scholars (Syed et al. 2024a; Blanco-Portela et al. 2017) for context-sensitive, holistic models, our study identifies these deficiencies and suggests future research directions. Such suggestions might help academics prevent further fracturing of the discipline and encourage the formation of new, unified research groups in the future. The recommendations aim to develop unified frameworks that incorporate the major drivers of change and encourage broader scholarly collaboration.

The practical implications of these findings can be outlined as follows. Firstly, this study equips the governing bodies of universities, such as Boards of Trustees or equivalent governing bodies, with a broader understanding of the motives and dynamics of HEI organizational change. Our results support top-level decision-makers, as they synthesize diverse case evidence and drivers of change, recognize the key forces prompting change – from shifting government policies and market pressures to sustainability mandates – and understand how these forces interact within their institutions (Lozano et al. 2013; Syed et al. 2024a). This improved understanding of both what catalyzes change and what potentially challenges it (such as stakeholders resisting cultural change or misalignment) can inform oversight more effectively, allowing boards to anticipate necessary changes and support strategies that transform responsively and well-informedly.

Secondly, the findings give direction to authorities in higher education and policymakers. These findings will assist them in drafting more comprehensive organizational change frameworks tailored to HEIs in their regions. Identified themes from the literature, alongside best practices, provide an evidence-based basis for policy creation. This foundation is attuned to global trends while adaptable to local contexts. For example, since typical reasons for change include quality control demands and sustainability aims (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017; Lozano et al. 2013), it implies that national higher education policies must incorporate sustainability-focused strategies and active enhancement methods within their directives for institutional transformation. Ministry officials can design more holistic change frameworks by drawing upon collective perceptions, as provided in this review, and aligning university development plans with broader social and economic objectives, while accounting for region-specific drivers and constraints.

The study provides a helpful guide. It is designed for HEI leaders as well as change management consultants who are implementing organizational change initiatives. Strong leadership, effective planning, and stakeholder engagement are demonstrated within the synthesized evidence on how change unfolds within universities. This evidence provides actionable guidance for navigating the change process. Our analysis reinforces that embedding sustainability considerations into the institution’s planned vision as well as its operations can be a critical success factor for change (Lozano et al. 2013). It highlights the importance of proactively addressing common barriers to change, such as stakeholder resistance or resource limitations, as identified in prior studies (Blanco-Portela et al. 2017).

University administrators, as well as consultants, can better tailor change interventions for their institution’s context and culture by following these evidence-based perceptions. This improves the likelihood of successful and lasting organizational improvements.

Thirdly, Academic faculty in higher education can incorporate the research’s relevant perceptions into teaching and knowledge dissemination, ultimately. As educators infuse the classroom with up-to-date research findings on organizational change in HEIs, they can prepare students – future managers, policymakers, as well as scholars – to grasp the complexities of change management in academic settings.

Theory and practice can be bridged by discussing real-world cases of institutional change in conjunction with theoretical frameworks and analyses from the literature (Syed et al. 2024a), as well as by enhancing students’ learning experiences. Academics can foster within students a nuanced understanding of how higher education institutions evolve and how change can be effectively managed within the sector by integrating topics such as stakeholder analysis, the various drivers for change, and the challenges involved in implementing change into the curriculum.

RQ 3: What are the probable future research directions on organizational change and HEIs?

The bibliometric and content analyses of research published on organizational change and HEIs illustrate various factors impeding the effective growth of this research area. However, there is scope and a need for it. However, key areas have been identified that are worthy of future investigations:

-

a.

Need for a comprehensive roadmap: Many studies have examined different aspects of organizational change in HEIs, such as leadership (Altmann and Ebersberger 2013), technology (Jiménez et al. 2019), and sustainability (Lozano et al. 2013). However, an all-inclusive and widely accepted roadmap could further develop this research area. It would not only assist in halting the further disintegration of the research field but also aid practitioners involved in organizational change in HEIs.

-

b.

Lack of international academic collaboration: Collaboration among academic scholars facilitates the enhancement of research through the flow of information (Cisneros et al. 2018). Most studies on organizational change in HEIs are generic. The proposed models and conceptual frameworks may not be applicable in different countries or regions due to institutional, social, economic, and political differences. Additionally, cross-country or multi-country studies are strongly recommended to better understand the dynamics and differential factors influencing organizational change in HEIs across various regional contexts.

-

c.

Lack of primary research studies: Few studies have incorporated primary data or documented organizational change in HEIs. Understanding the motives and dynamics of organizational change in HEIs across diverse settings would be vital. Therefore, a comprehensive database should be developed that facilitates systematic and effective research across different regions.

-

d.

Lack of concept building: Although various authors have introduced key concepts regarding organizational change in HEIs over the last twenty years, the academic community has not further investigated or developed those areas.

-

e.

Thematic Specialization in Journals: This area of research has been widely published in journals in the last two and a half decades, especially with the recent increase in special issues. While cluster analysis (refer to Fig. 9) illustrates the emergence of critical themes, a journal call could consider more in-depth analysis of the themes for papers on special issues, which could result in some of the themes being probed further:

Cluster 1: What models could be adopted to effectively assess the impact on HEIs during and after organizational change implementation? What are the better means or techniques to conduct comprehensive research on organizational change in HEIs? How can the organizational change process be more effectively assessed, particularly in Asian and African contexts?

Cluster 2: Are there any other motives to initiate the organizational process in HEIs apart from the ones elucidated in the literature? In African and Asian countries, how is the triple-helix model of innovation implemented? What aspects of local/international higher education accreditation processes have the most decisive influence?

Cluster 3: How does organizational culture impact organizational change in HEIs across regions? How does the diversity of people in HEIs shape the entire process? What are the challenges faced by students and academics in the organizational change process?

Cluster 4: How has strategic planning and leadership in HEIs evolved in developing countries? What is the interplay between transformational and transactional variables during the organizational change process? What is the significance of knowledge transfer during the organizational change process in HEIs?

Conclusion

The existing literature on organizational change in HEIs provides a reasonable basis for understanding and further developing the field. Data from the published literature advocate the impact of organizational change on HEIs’ sustainability. This work illustrates that the research field has developed due to the contributions of scholars worldwide. However, there is scope for further heterogeneity and spread of impact across most authors. In conclusion, this study offers a unique and clear perspective on organizational change in HEI research, utilizing bibliometrics and content analysis. However, this inquiry, like any other, has limits. Scopus was the sole database used to retrieve published papers on the selected subject. Supplementary research may include reviewing published articles from databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO, Web of Science, and Open-Access Journals. Comparative studies across these databases could also be considered. Second, keywords were selected based on our interpretation of organizational change in HEIs after reviewing the existing literature. Other keywords may have been left out, and new ones might come up in the future. It is recommended that additional or newer keywords be incorporated after reviewing the literature from other databases mentioned above.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Ahmad N, Menegaki AN, Al-Muharrami S (2020) Systematic literature review of tourism growth nexus: an overview of the literature and a content analysis of 100 most influential papers. J Econ Surv 34(5):1068–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12386

Akin HB, Demirel Y (2015) Entrepreneurship education and perception change: the preliminary outcomes of compulsory entrepreneurship course experience in Turkey/Girisimcilik Egitimi ve Algida Degisim: Türkiye’de Zorunlu Girisimcilik Dersi Deneyiminin Ilk Sonuçlari. Selcuk Üniv Sos Bilim Enst Derg 2015(34):15–26

Al-Abri MY, Rahim AA, Hussain NH (2018) Entrepreneurial ecosystem: an exploration of the entrepreneurship model for SMEs in Sultanate of Oman. Mediterr J Soc Sci 9(6):193–206. https://doi.org/10.2478/mjss-2018-0175

Albort-Morant G, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2016) A bibliometric analysis of the international impact of business incubators. J Bus Res 69(5):1775–1779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.054

Altbach PG, de Wit H (2018) The challenge to higher education internationalization. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180220091648602

Altmann A Ebersberger B (2013) Universities in change: managing higher education institutions in the age of globalization. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4590-6

Aubry M et al. (2021) Higher education for sustainability: a global perspective. J Clean Prod 2(3):41–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj/pmj/pmj/pmj/pmj

Aubry M, Richer MC, Lavoie-Tremblay M (2014a) Governance performance in a complex environment: the case of a major transformation in a university hospital. Int J Proj Manag 32(8):1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.07.008

Audretsch DB (2014) From the entrepreneurial university to the university for the entrepreneurial society. J Technol Transf 39(3):313–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9288-1

Austin I, Jones GA (2016) Governance of higher education: global perspectives, theories, and practices. Routledge

Bendermacher GWG, Egbrink MGA, Wolfhagen IHAP, Dolmans DHJM (2017) Unravelling quality culture in higher education: a realist review. High Educ 73(1):39–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9979-2

Benomar L et al. (2022) Bibliometric analysis of the structure and evolution of research on assisted migration. In: Current forestry reports. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, pp 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-022-00165-y

Bergan S, Deca L (2018) Twenty years of the Bologna process: achievements and challenges. Eur J Educ 53(1):51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12258

Bhopal K, Pitkin C (2020) ‘Same old story, just a different policy’: race and policy making in higher education in the UK. Race Ethn Educ 23(4):530–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1718082

Blanco-Portela N et al. (2017) Towards the integration of sustainability in higher education institutions: a review of drivers of and barriers to organizational change and their comparison against those of companies. J Clean Prod 166:563–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.252

Bleiklie I, Michelsen S (2013) Comparing HE policies in Europe: Structures and reform outputs in eight countries Higher Education 65:113–133

Boh WF et al. (2003) ‘What are the trade-offs of academic entrepreneurship? An investigation on the Italian case. J Technol Transf 43(4):661–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9399-6

Boh WF, De-Haan U, Strom R (2016) University technology transfer through entrepreneurship: faculty and students in spinoffs. J Technol Transf 41(4):661–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9399-6

Bouckenooghe D et al. (2021) Revisiting research on attitudes toward organizational change: bibliometric analysis and content facet analysis. J Bus Res 135:137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.028

Boyce ME (2003) Organizational learning is essential to achieving and sustaining change in higher education. Innovative higher education 28:119–136

Brennan J, King R, Lebeau Y (2004) The role of universities in transforming societies. Association of Commonwealth Universities, p 72. https://doi.org/10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2013)08-2071-04

Bryman A (2008) Effective leadership in higher education: a literature review. Stud Higher Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685114

Carroll M et al. (2009) Progress in developing a national quality management system for higher education in Oman. Qual High Educ 15(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320902731328

Castriotta M et al. (2019) What’s in a name? Exploring the conceptual structure of emerging organizations, Scientometrics. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2977-2

Cisneros L et al. (2018) Bibliometric study of family business succession between 1939 and 2017: mapping and analyzing authors’ networks, Scientometrics. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2889-1

Cunningham JA, Menter M (2021) Transformative change in higher education: entrepreneurial universities and high-technology entrepreneurship. Ind Innov 28(3):343–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2020.1763263

Dalmarco G, Hulsink W, Blois GV (2018) Technological forecasting & social change creating entrepreneurial universities in an emerging economy: evidence from Brazil. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.04.015

Diedericks JC, Cilliers F, Bezuidenhout A (2019) Resistance to change, work engagement and psychological capital of academics in an open distance learning work environment. SA J Hum Res Manag 17:1–14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v17i0.1142

Durán-Sánchez A et al. (2019) Mapping of scientific coverage on education for entrepreneurship in higher education. J Enterp Communities 13(1–2):84–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-10-2018-0072

Eddy PL (2006) Nested leadership: the interpretation of organizational change in a multi-college system. Community Coll J Res Pract 30(1):41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920500248878

Etzkowitz H (1998) The norms of entrepreneurial science: cognitive effects of the new university-industry linkages. Res Policy 27(8):823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00093-6

Etzkowitz H (2003) Innovation in innovation: the triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Soc Sci Inf 42(3):293–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184030423002

Ferrero-Ferrero I et al. (2018) Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting in higher education. Int J Sustainability High Educ 19(2):313–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe-06-2016-0116

Fischer B et al. (2021) Knowledge transfer for frugal innovation: where do entrepreneurial universities stand? J Knowl Manag 25(2):360–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2020-0040

Fitzgerald C, Cunningham JA (2016) Inside the university technology transfer office: mission statement analysis. J Technol Transf 41(5):1235–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9419-6

Forster M (2018) Higher education reform in the Gulf States: possibilities and limitations of applying policy borrowing models. Comp: A J Comp Int Educ 48(1):36–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1318377

Grimaldi R et al. (2011) 30 years after Bayh-Dole: reassessing academic entrepreneurship. Res Policy 40(8):1045–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.04.005

Hallinger P, Chatpinyakoop C (2019) A bibliometric review of research on higher education for sustainable development, 1998–2018. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082401

Hazelkorn E (2015) Rankings and the reshaping of higher education: the battle for world-class excellence, 2nd edn. Palgrave Macmillan

Hempsall K (2014) Developing leadership in higher education: perspectives from the USA, the UK, and Australia. J High Educ Policy Manag 36(4):383–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2014.916468

Hillman N (2016) Why performance-based college funding doesn’t work. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/why-performance-based-college-funding-doesnt-work/

Hou YC, Ince M, Tsai S (2015) Quality assurance in higher education: a comparison of the mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong experiences. Front Educ China 10(4):486–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03397019

Jiménez CR, Prieto MS, García SA (2019) Technology and higher education: a bibliometric analysis. Educ Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030169

Jongbloed B, Vossensteyn H (2016) University funding and student funding: International comparisons. In The Palgrave international handbook of higher education policy and governance. Palgrave Macmillan, pp 439–462

Kent Baker H et al. (2020) A bibliometric analysis of board diversity: current status, development, and future research directions. J Bus Res 108:232–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.025

Kirby DA (2006) Creating entrepreneurial universities in the UK: applying entrepreneurship theory to practice. J Technol Transf 31(5):599–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-006-9061-4

Knight J (2015) International universities: misunderstandings and emerging models? J Stud Int Educ 19(2):107–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315572899

Kosmützky A, Putty R (2016) Transcending borders and traversing boundaries: a systematic review of the literature on transnational, offshore, cross-border, and borderless higher education. J Stud Int Educ 20(1):8–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315604719

Labanauskis R, Ginevičius R (2017) Role of stakeholders leading to the development of higher education services. Eng Manag Prod Serv 9(3):63–75. https://doi.org/10.1515/emj-2017-0026

Lazzeretti L, Tavoletti E (2005) Higher education excellence and local economic development: The case of the entrepreneurial University of Twente European Planning Studies 13:475–49

Lee MNN, Lee MM (2019) Higher education in Malaysia: emerging directions. In: Mok K-H, Neubauer I (eds) Higher education in Asia-Pacific. Springer, pp 201–217

Li C, Wu K, Wu J (2017) A bibliometric analysis of research on haze during 2000–2016. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24(32):24733–24742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0440-1

Lozano R et al. (2013) Advancing higher education for sustainable development: international insights and critical reflections. J Clean Prod 48:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.03.034

Marginson S (2018) The new geo-politics of higher education. Cent Glob High Educ Working Pap Ser 34:1–29. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31234.89285

Markman GD et al. (2005) Innovation speed: transferring university technology to market. Res Policy 34(7):1058–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.007

Mars MM, Rios-Aguilar C (2010) Academic entrepreneurship (re)defined: significance and implications for the scholarship of higher education. High Educ 59(4):441–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9258-1

Marshall S (2010) Change, technology, and higher education: are universities capable of organizational change? ALT-J Res Learn Technol 18(3):179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687769.2010.529107

McAllister JT, Lennertz L, Atencio Mojica Z (2022) Mapping a discipline: a guide to using vosviewer for bibliometric and visual analysis. Sci Technol Libraries 41(3):319–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2021.1991547

Menegaki AN et al. (2021) The convergence in various dimensions of energy-economy-environment linkages: a comprehensive citation-based systematic literature review. Energy Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105653

Miller DJ, Acs ZJ (2017) The campus as an entrepreneurial ecosystem: the University of Chicago. Small Bus Econ 49(1):75–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9868-4

Mowery DC, Sampat BN (2004) The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 and university-industry technology transfer: a model for otherOECD governments? J technol transf 30:115–127

Mowery DC, Sampat BN (2005) The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 and university-industry technology transfer: a model for other OECD governments?. In: Essays in Honor of Edwin Mansfield: the economics of R&D, innovation, and technological change. pp 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-25022-0_18

Mok K H, Jiang J (2018) Massification of higher education and challenges for graduate employment and social mobility: East Asian experiences and sociological reflections. Int J Educ Dev 63:44–51

Naidoo R (2018) The competition fetish in higher education: shamans, mind snares and consequences. Eur Educ Res J 17(5):605–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118784839

Palacios-Callender M, Roberts SA (2018) Scientific collaboration of Cuban researchers working in Europe: understanding relations between origin and destination countries. Scientometrics 117(2):745–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2888-2

Papa A et al. (2017) The ecosystem of entrepreneurial university: the case of higher education in a developing country. Int J Technol Manag 1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2017.10009460

Phillips KW (2014) How diversity makes us smarter. Sci Am 311(4):42–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1014-42

Philpott K et al. (2011) The entrepreneurial university: examining the underlying academic tensions. Technovation 31(4):161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.12.003

Pugh R et al. (2016) A step into the unknown: universities and the governance of regional economic development. Eur Plan Stud 24(7):1357–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1173201

Ramaprasad A, La Paz AI (2008) Transformation to an entrepreneurial university: balancing the portfolio of facilitators and barriers. SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1307111

Sanjeev MA, Agrawal R, Syed RT, Arumugam T, K Praveena (2024) Impact of sustainability education on senior student attitudes and behaviours: evidence from India. Int J Sustain Higher Educ. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-01-2024-0024

Sen S, Cowley J (2013) The relevance of stakeholder theory and social capital theory in the context of CSR in SMEs: an Australian perspective. J Bus Ethics 118(2):413–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1598-6

Seeber M, Lepori B, Lomi A, Aguillo I, Barberio V (2012) Factors affecting web links between European higher education institutions. J informetr 6:435–447

Shi J et al. (2020) Comprehensive metrological and content analysis of the public-private partnerships (PPPs) research field: a new bibliometric journey. Scientometrics 124(3):2145–2184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03607-1

Siegel DS, Wright M, Lockett A (2007) The rise of entrepreneurial activity at universities: organizational and societal implications. Ind Corp Chang 16(4):489–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm015

Singh D, Malik G (2022) A systematic and bibliometric review of the financial well-being: advancements in the current status andfuture research agenda. Int J Bank Mark 40:1575–1609

Singh D, Srivastava AK, Malik G, Yadav A, Jain P (2025) Insurance and economic growth nexus: a comprehensive exploration of the dynamic relationship and future research trajectories. J Econ Surv 39:841–876

Stam E (2015) Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. Eur Plan Stud 23(9):1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

Stephens JC, Graham AC (2010) Toward an empirical research agenda for sustainability in higher education: exploring the transition management framework. J Clean Prod 18(7):611–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.07.009

Syed RT, Spicer D (2025) Entrepreneurial university development through the lens of stakeholders. Why? What? and How? J Innov Entrep 14(1):36

Syed RT, Singh D, Agrawal R, Spicer D (2024a) Higher education institutions and stakeholder analysis: theoretical roots, development of themes and future research directions. Ind High Educ 38(3):218–233

Syed RT, Singh D, Ahmad N, Butt I (2024b) Age and entrepreneurship: Mapping the scientific coverage and future research directions. Int Entrep Manag J 20(2):1451–1486

Syed RT, Singh D, Agrawal R, Spicer DP (2023) Entrepreneurship development in universities across Gulf Cooperation Council countries: a systematic review of the research and way forward. J Enterp Communities. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-03-2022-0045

Syed RT, Singh D, Spicer D (2022) Entrepreneurial higher education institutions: development of the research and future directions. Higher Educ Q https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12379

Tahamtan I, Safipour Afshar A, Ahamdzadeh K (2016) Factors affecting several citations: a comprehensive review of the literature. Scientometrics 107(3):1195–1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1889-2

Tian X et al. (2018) A bibliometric analysis on trends and characteristics of carbon emissions from the transport sector. Transp Res D Transp Environ 59:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.12.009

Toole AA, Czarnitzki D (2010) Commercializing science: is there a university “brain drain” from academic entrepreneurship? Manag Sci 56(9):1599–1614. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1100.1192

Trowler, P. (2008) Cultures and change in higher education: Theories and practices. Bloomsbury Publishing

Tunger D, Eulerich M (2018) Bibliometric analysis of corporate governance research in German-speaking countries: applying bibliometrics to business research using a custom-made database. Scientometrics 117(3):2041–2059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2919-z

Van Praag CM, Versloot PH (2007) What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Bus Econ 29(4):351–382

Velazquez L, Munguia N, Platt A, Taddei J (2006) Sustainable university: what can be the matter? J Cleaner Prod 14:810–819

Wentworth DK et al. (2018) Studies in higher education: implementing a new student evaluation of teaching system using the Kotter change model. Stud High Educ 0(0):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1544234

Williams DA (2013) Strategic diversity leadership: activating change and transformation in higher education. Stylus Publishing

Williamson B (2018) Silicon startup schools: technocracy, algorithmic imaginaries, and venture philanthropy in corporate education reform. Crit Stud Educ 59(2):218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1186710

Wright M (2014) Academic entrepreneurship, technology transfer, and society: where next? J Technol Transf 39(3):322–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9286-3

Žalėnienė I, Pereira P (2021) Higher education for sustainability: a global perspective. Geogr Sustain 2(2):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.05.001

Acknowledgements

The authors from the United Arab Emirates University would like to acknowledge the financial support received through the Strategic Research Program (Grant Code: G00004602).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RTS, DS, and SVK wrote the first draft of the manuscript, carried out data analysis, and developed visualization. RAA conceptualized this paper, brought the funding, and assisted in drafting and revising sections of the paper. TAA assisted in reviewing, drafting, and revising sections of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethics approval is not applicable for this study, as it does not involve any human participants or their data.

Informed statement

The informed statement is not applicable for this study, as it does not involve any human participants or their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alzahmi, R.A., Syed, R.T., Singh, D. et al. Organizational change in higher education institutions: thematic mapping of the literature and future research agenda. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05650-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05650-w