Abstract

The terms left and right are essential poles in the context of political ideology. Their meanings and understandings vary across contexts, affecting political communication, discourse, representation and polarisation dynamics. We know less about how different meanings and understandings manifest themselves beyond differential usage of the left-right scale. Building on this research gap, I measure how associations with left and right systematically vary across different political positions. I present a novel theoretical two-dimensional model distinguishing between left- and right-leaning individuals and their associations with left and right. In doing so, I propose ‘in-ideology’ (alignment with one’s political leanings) and ‘out-ideology’ (opposition to one’s leanings) as a theoretical foundation to understand diverging associations. Using data from German GLES candidate studies (2013, 2017, 2021), I introduce a methodological framework that maps left-right word associations from open-ended survey responses into a semantic space, combining these with political positions to reflect the in- and out-ideology dichotomy. The findings reveal substantive differences based on left-right positions, manifested in associations with positive connotations for in-ideology—for example, justice (left) and patriotism (right)—and negative connotations for out-ideology—for example, racism (right) and socialism (left). The model’s applicability is demonstrated in scaling parliamentary speeches and is reliable across different model specifications in terms of construct and external validity. The study advances the understanding of ideological associations and their role in political research by highlighting the importance of distinguishing between in- and out-ideology in explaining ideological language across the political spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ serve as foundational markers in politics, encapsulating broad ideological associations that help individuals situate themselves and others within the political system (Arian and Shamir, 1983; Cochrane, 2015; Downs, 1957; Feldman and Johnston, 2014; Jost, 2021; Kitschelt and Hellemenas, 1990).Footnote 1 Several studies claim that left and right have different meanings and represent different political dimensions across contexts (Bauer et al. 2017; Beattie et al. 2022; Dinas, 2017; Dinas and Northmore-Ball, 2020; Lewis, 2021; Tavits and Letki, 2009; Yeung and Quek, 2024), which affects how individuals perceive and evaluate ideology. When individuals attach sharply different meanings to left and right, the implications for the political system are profound. Without a shared understanding, ideological signals are misinterpreted, effective political communication is inhibited, and representational mechanisms suffer when asymmetry spills over into policy-making (Broockman and Skovron, 2018). Divergent understandings of left and right may also increase polarisation by reinforcing in-group loyalty and out-group aversion (Abramowitz and Webster, 2016; Costa, 2021; Iyengar et al. 2012; Wagner, 2021). Despite these dynamics, however, research lacks a coherent framework for measuring left-right meanings in a way that captures these in-group and out-group dynamics. This study aims to provide such a framework.

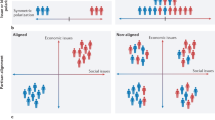

The theoretical conceptualisation bridges findings from studies of political categorisation that affect the left-right continuum with positional in-group and out-group biases (Bølstad and Dinas, 2017; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019) and a systematic approach to studying the semantics (Palmer, 1981) of ideological associations (Bauer et al. 2017). Research on political ideology shows that different manifestations around left and right are variable in their complexity—concrete policies, values, but also complex world views and isms—which also vary between positive and negative connotations (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023). To account for this complexity, I propose a two-dimensional theoretical model that distinguishes between left-leaning and right-leaning political actors on one dimension and between left and right associations on a second semantic dimension to conceptualise group-specific categorisation differences. The resulting ‘quadrants’ represent the function political position has for the associations of left and right. Left-leaning individuals have positive connotations with left (e.g., ‘justice’) and negative connotations with right (e.g., ‘racism’). Similarly, right-leaning individuals should have positive connotations with right (e.g., ‘patriotism’) and negative connotations with left (e.g., ‘socialism’). This theoretical distinction based on positional and semantic differences can be understood in a dichotomous manner by treating the diverging association regimes as ‘in-ideology’ and ‘out-ideology’. In-ideology is the dynamic in which individuals refer to the ideological pole to which they also positionally belong—left-leaning individuals’ associations with left, and right-leaning individuals’ associations with right. Out-ideology refers to the opposite dynamic, in which individuals refer to the ‘opposing’ ideological pole—left-leaning individuals’ associations with right and right-leaning individuals’ associations with left.

Empirically, I draw on data from the 2013, 2017 and 2021 candidate survey waves of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) (GLES, 2014, 2018, 2023a), as politically sophisticated elites exhibit coherent, unidimensional left-right preferences that are a prerequisite for valid ideological mapping (Lupton et al. 2015). In particular, I use the survey items in which candidates were asked what they associate with left and right, respectively, in addition to left-right self-placement as a central indicator of political position. Methodologically, I a) rely on word embeddings to unify the left-right associations and map them into a one-dimensional semantic space and b) combine this semantic dimension with left-right positions to construct the two-dimensional space reflecting the in- and out-ideology dichotomy. After constructing and demonstrating the applicability of the method, I show its construct validity by using different embeddings and varying model parameters, and its external validity by scaling parliamentary speeches of German MPs.

The results show clear differences in how left and right are associated based on the political position of elite individuals, in line with the theoretical expectations of ‘in- and out-ideological associations’. Left-right associations often indicate the ideological position of the individual, although some terms remain ‘centrist’ or ideologically non-indicative, as they are used similarly by both left- and right-leaning individuals to describe in-ideology. Interestingly, ‘out-ideology’ or ‘negative ideology’ (associations of left-leaning individuals with the right and right-leaning individuals with the left) appears to be more informative than ‘in-ideology’. Specifically, both left-leaning and right-leaning individuals maintain coherent and prominent associations with the opposite ideological label, whereas associations with the right as in-ideology are less consistent. I demonstrate construct validity by using different embeddings and varying model parameters, and external validity by using in- and out-ideological associations separately to scale parliamentary speeches of German Bundestag MPs.

The paper contributes to the study of ideology by theorising and measuring divergent associations of left and right. Left and right are central categories, prominent in public discourse and fundamental to political science. The distinction between in-ideology and out-ideology is crucial for several aspects of political research, including behavioural, communicative, psychological and representational aspects, where the conceptualisation and explanation of concrete association regimes has not yet been comprehensively addressed. In this light, the study facilitates an explanation of political conflict through the variability of ideological language use across the political spectrum.

Left and right: unified or divided perception?

The study of political ideology is based on several theoretical frameworks, with the left-right dichotomy taking centre stage. Traditionally, left and right have been seen in terms of policies, values and, more broadly, the societal goals and systems of ideas they represent. The left typically advocates for social equality, governmental intervention in the economy, and progressive social policies, while the right emphasises free-market principles, limited government, and traditional social norms (Cochrane, 2015; Jost, 2021; Ostrowski, 2023; Zechmeister and Corral, 2013). These concepts are not static and can vary significantly across different political contexts, reflecting the dynamic nature of political ideologies (Dinas, 2012; Dinas and Northmore-Ball, 2020; Jahn, 2023; Yeung and Quek, 2024). Understanding the processes behind political categorisation, where individuals perceive ideological elements based on varying political meanings, is crucial in examining how left and right serve as shorthand for more complex political dynamics (Bauer et al. 2017; Bølstad and Dinas, 2017; Dinas, 2012; Ostrowski, 2023; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019; Zollinger, 2024). Recent empirical research emphasizes that left-right categorisations often encapsulate deeper identity- and group-based elements rather than mere policy preferences (Claassen et al. 2015; Devine, 2015; Ellis and Stimson, 2012; Jahn, 2023; Mason, 2018; Popp and Rudolph, 2011).

The debate over the meaning of left-right is dominated by two theoretical lenses—operational and symbolic ideology. Operational ideology typically equates the left-right scale with policy preferences or an aggregation of policy preferences as a super-issue, following the classic Downsian conception (Downs, 1957). Symbolic ideology, on the other hand, refers to ideological attachments and identification with ideological poles, such as left and right or liberal and conservative (Devine, 2015; Popp and Rudolph, 2011).

However, the empirical manifestation is not necessarily clear. Some scholars equate operational ideology with concrete policy preferences and symbolic ideology with the left-right and/or liberal-conservative scale (Claassen et al. 2015; Popp and Rudolph, 2011). In contrast, Vegetti and Širinić (2019) emphasise specific in-group and out-group symbolic manifestations that shape the understanding of left-right, reflecting heuristic cognitive processes that shape how individuals use the left-right scale. Ideological symbols, such as parties, are therefore categorised and placed on the ideological spectrum based on in- and out-group categorisation biases. Vegetti and Širinić (2019) find evidence of an out-group bias: individuals perceive out-group parties as more distant than they actually are, based on their categorical camp (left or right) on the left-right spectrum. Bølstad and Dinas (2017) find spatial ‘in-group favouritism’, which leads to a biased perception of smaller political differences within the same ideological (again, left or right) camp.Footnote 2

Hence, there is both theoretical and empirical evidence to conclude that there is an asymmetrical understanding of the left-right scale based on biased spatial symbolic manifestations of ideology. The evidence of the differential understanding of the left-right scale is, however, conceptually limited. We know that symbolic elements are affected by spatial in- and out-group biases, but we know less about what these look like beyond the given examples of political actors, such as parties and party supporters. In short, we lack a clear understanding of how ideological meanings are manifested on a broader scale and how to measure them systematically. This gap calls for a comprehensive theoretical and empirical approach to analysing ideological elements within the left-right spectrum.

In the context of a deeper understanding of ideological manifestations and understandings, recent studies examine open-ended survey responses with ideological associations (Bauer et al. 2017; Gidron and Tichelbaecker, 2025; Jankowski et al. 2023; Zollinger, 2024; Zuell and Scholz, 2019). By analysing these responses, we can identify patterns in the semantic associations of left and right and their correspondence with other political covariates. Semantics, as the study of meaning in language, plays a decisive role in understanding diverging ideological associations based on contextual factors (Palmer, 1981).

Associations with ideology are by definition broad and include a variety of different associations, encompassing both operational and symbolic elements (Bauer et al. 2017). Associating ideology serves a heuristic purpose, reflecting different understandings depending on an individual’s political position as demonstrated by Bauer et al. (2017): When individuals position themselves on the left-right scale, they project certain ideas of ideology, in other words, ideological associations, onto the left-right continuum, resulting in a variability regime of divergent associations. More specifically, left-right associations differ in terms of different connotations—positive and negative—but the authors do not further synthesise how this systematically relates to ideological in-group and out-group categorisations. Thus, a concrete theoretical integration of divergent left-right associations based on left-right position is missing, which is striking given the spatial categorisation biases (Bølstad and Dinas, 2017; Devine, 2015; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019) and polarised nature of contemporary political systems (Iyengar et al. 2012; Wagner, 2021).

The analysis of left-right associations is possible for different types of individuals, provided that the left-right distinction plays a role in the embedded political context. Research shows, however, that the understanding of left and right differs across individuals, based on the degree of political sophistication (Gallina, 2023; Lupton et al. 2015). Lupton et al. (2015) find that there is a sharp distinction between politically sophisticated and unsophisticated individuals, where the empirical manifestation is mostly pronounced between elites and citizens. Political elites structure their political attitudes and preferences in a unidimensional way, constituting a systematic understanding of the left-right continuum that allows for political abstraction. The study of political elites is further motivated by their relevance to the political system, given their role in party politics, political communication and representation, as well as effective policy-making and governance capabilities (Körösényi, 2018). Finally, it is striking that the study of elites in the context of left-right associations has received far less attention (Jankowski et al. 2023) than that of citizens (Bauer et al. 2017; Gidron and Tichelbaecker, 2025; Zollinger, 2024; Zuell and Scholz, 2019), despite their political relevance and the level of sophistication in relation to the left-right continuum.

A theoretical model of diverging left-right associations

In this section, I present a theoretical model for systematically measuring left-right ideological associations by distinguishing between a) in-group and out-group mechanisms and b) semantic differences. Synthesising in- and out-group dynamics that underlie polarised partisan identities and symbolic ideological categorisation with left-right associations, I project ideological association identities as in-ideology and out-ideology into a political space that accounts for systematic spatial divergences based on varying left-right perceptions and understandings.

Transferring ideology into the in- and out-group dimension, in-ideology refers to the ideology individuals feel close to, and out-ideology refers to the ideology individuals oppose. While ideological understanding can be inherently multidimensional, e.g., reflecting both economic and cultural elements (Carmines and D’Amico, 2015; Feldman and Johnston, 2014), I use left and right in a dichotomous unidimensional manner in this context, reflecting the ‘politically sophisticated’ capabilities of political elites (Lupton et al. 2015). Hence, there are two ideological groups, left- and right-leaning individuals (elites). Consequently, the in-ideology of left-leaning individuals is left, while the out-ideology is right. The same pattern applies for right-leaning individuals, with right as the in-ideology and left as the out-ideology.Footnote 3

The spatial categorisation biases drive the distinction between in- and out-ideological associations. Ostrowski (2023, p. 1) argues that left and right ‘are designed to prompt clear positive or negative (and occasionally, but rarely, neutral) inferences about the ideas, people and so on, they are attached to.’ Positive and negative connotations are therefore a key driver of divergent left-right associations, resulting in in-ideology associated with positive connotations and negative out-ideology associated with negative connotations. Differentiating between left and right, I expect that associations with the left will have positive connotations for left-leaning individuals and negative connotations for right-leaning individuals. Conversely, associations with the right will have negative connotations for left-leaning individuals and positive connotations for right-leaning individuals.

The theoretical insights culminate in a two-dimensional theoretical framework, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In-ideological associations are represented by the upper right (right-leaning associations with the right) and the lower left quadrant (left-leaning associations with the left). Conversely, out-ideological associations are represented by the upper left (left-leaning associations with the right) and lower right quadrant (right-leaning associations with the left).

Understanding how ideological associations manifest is essential before moving on to analyse the positional and semantic dimensions. In other words, what kinds of associations exist, what reflections of the left-right continuum are to be expected? Beyond widely known and approached symbolic cues, such as party identities (Bølstad and Dinas, 2017; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019), ideologies as broad systems of ideas can evoke several types of associations, such as values (Carmines and D’Amico, 2015; Rohan and Zanna, 2001), policies (Downs, 1957) and ‘isms’ (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023).

While some associations may have neutral or ideologically non-group-specific connotations, I expect the majority of associations to be normatively charged according to their position on the left-right continuum (Bauer et al. 2017; Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023; Zollinger, 2024). The type of association also influences the connotation. While values are comparatively positive connoted (Carmines and D’Amico, 2015), I expect them to drive in-ideology more than out-ideology. Broader concepts, such as ideological isms, are more complex by nature. Kurunmäki and Marjanen (2018) describe that isms, such as liberalism, socialism and conservatism, were initially used pejoratively, while there was also space for a positive re-identification as a positive in-group identification. However, for certain ‘isms such as racism or terrorism’ (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018, p. 261), a positive connotation is practically not possible as their pejorative character is decisive.

In semantic terms, associations differ, as some are much more prominent or even exclusively associated with the left or the right. In this respect, socialism is semantically left and conservatism is semantically right, while liberalism is harder to locate, given its more centrist position in the evolution of ideologies, but also its pronounced polarity against the right or conservative, especially in the US (Caprara and Vecchione, 2018; Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023). Given the rise of anti-immigration attitudes among the political right (Dennison and Geddes, 2019), I expect ‘racism’ to be a prominent semantically right out-ideological association, given its negative connotation and semantic role in the context of anti-immigration policies of the right. Kurunmäki and Marjanen (2018) discuss distinctive isms with diverging positive and negative connotation regimes and find that patriotism (in contrast to nationalism) corresponds to a positive in-group identification. Therefore, I expect ‘patriotism’ to be a prominent ideological association of the right, as it semantically reflects the political right along with nationalism (Herrmann and Döring, 2023), but represents a more positive ideological identification.

Analogously, semantically left associations can also be differentiated between in- and out-ideology. Research has found that left-leaning individuals place particular emphasis on values such as justice and egalitarian principles (Carmines and D’Amico, 2015; Graham et al. 2009). Given the positive connotation of values, I expect ‘justice’ to form an in-ideological association identity. Larson (2021) stresses that socialism, next to communism, has faced negative connotations related to the ideological pejorative dynamic (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018). While there may be positive (in-ideological) connotations with socialism, also referring to many parties using that ideological label, there seems to be specific saliency in its out-ideological use (Ciuk and Yost, 2016). Chong and Druckman (2007) theorise that political concepts, such as ideological constructs, have alternating meanings depending on their framing. Specifically, political communication considerations drive the framing of political concepts, resulting in either positive or negative connotations. Thus, the framing of socialism as a harmful political concept, driven by the negative connotations of right-leaning actors, constitutes its out-ideological salience and drives my expectation that ‘socialism’ is a manifestation of left out-ideology. Related research shows that salient political issues, such as immigration, as discussed above, are a key target for political framing (Helbling, 2014; Klein and Amis, 2021; Roggeband and Vliegenthart, 2007). While the framing of political issues tends to reflect symbolic ideological mechanisms, the framing of socialism tends to manifest an abstract ideological concept, which is far less empirically studied than the framing of political issues. In this respect, the exploration and mapping of ideological associations, also beyond the case of socialism, on a larger scale, relates to a novel exploration of political communication mechanisms.

Table 1 presents the given examples of left and right ideological associations, highlighting their connotations and conceptually mirroring the two dimensions of Fig. 1.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the examples given have a degree of vagueness, as associations vary according to various contextual factors. Nevertheless, I assume that they represent valid assumptions about how left and right are manifested in associative terms by incorporating their salient positive and negative connotations, which is based on several findings from the literature as shown above. However, there are many more associations with left and right that I will systematically explore with my empirical strategy.

Before elaborating on the dimensional mechanisms, I would also like to emphasise that (1) more detailed representative deductive hypotheses—reflecting concrete associations—are not easy to pin down, as associations are generally variable and not uniform (Bauer et al. 2017; Zollinger, 2024). (2) Left-right associations can effectively manifest both elements of operational and symbolic ideology, since the theoretical model is somewhat agnostic about this debate, since my reading of the literature is that ideological associations, such as isms and values, can be interpreted in both operational and symbolic terms, since the associations are not limited in terms of abstraction.

Positional dimension

This section focuses on the dynamics along the positional (horizontal) dimension. Specifically, it examines how shifts in an individual’s left-right position influence associations with ‘left’ and ‘right’. I argue that such shifts are not only spatial but also semantic, as they fundamentally alter the connotations attached to ideological associations.

Figure 1 displays four ‘quadrants’ that could signal a categorical understanding of the left-right semantic space; I want to stress that these mechanics are essentially continuous, both positionally (horizontally) and semantically (vertically). This can be demonstrated best with an example. The three ideological isms, racism, nationalism and patriotism represent typical associations with the right (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023). However, they are characterised by different connotations corresponding to diverging political positions on average. Racism is expected to have the most negative connotation (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018), hence it is used by more left-wing individuals to associate with the right, compared to nationalism and patriotism.

While nationalism and patriotism can be seen as conceptually very close, Kurunmäki and Marjanen (2018) stress that patriotism has a more positive ideological identification compared to nationalism. In this context, findings from social psychology explain why very similar words—as nationalism and patriotism arguably are in the ideological context—can guide distinctive positive and negative characteristics by referring to ‘semantic prosody’ (Hauser and Schwarz, 2018, 2023).

If we synthesise these three diverging connotation patterns, we can think of political position as a function for specific associations. The more left-leaning an individual’s position, the more likely she or he is to associate the right with racism compared to nationalism and patriotism. As one ‘moves’ to the right along the left-right position dimension (representing a horizontal shift on Fig. 1), other associations with increasingly positive connotations become more prominent.

Thus, as I argue, nationalism has a less negative connotation compared to racism, resulting in a higher (more right) average left-right position when associating with the right. Patriotism is even ‘more right’ in positional terms, as it has fewer negative connotations compared to racism and nationalism. In other words, the association of the right with patriotism is less (more) achieved by left-wing (right-wing) individuals compared to nationalism and especially racism. Racism and to a lesser extent nationalism hence present cases of out-ideological associations, as they reflect how left-leaning individuals associate their out-ideology (the right). I assume that patriotism should have a comparatively positive association character in this context (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018).

This example of right-wing associations also applies to left-wing associations. Socialism should, on average, have a more negative connotation than justice, which would lead to more left-wing positions with justice compared to socialism. Justice is therefore an ideologically neutral association, reflecting how left-leaning individuals associate with the left. Socialism is less an in-ideological association in comparison, as it reflects particular out-ideological associations (Larson, 2021). Mapping left and right associations in terms of their concrete positional character is complex. It is challenging to assert that patriotism is as positive as justice regarding the (average) political position of individuals associating it with the right or left. This intriguing complexity justifies an inductive exploratory analytical framework, both theoretical and empirical.

Semantic dimension

The above examples relate to position (horizontal) dynamics. In other words, if a person’s position changes, how does this affect the association with left and right? I argue that a positional change is related to a change in connotations, which has a fundamental impact on how left and right are associated. On the other hand, semantic change (vertical dimension, as demonstrated in Fig. 1) refers ‘how left’ or ‘how right’ a term is, regardless of whether the associating individuals are left-leaning or right-leaning.

Racism and nationalism are almost exclusively associated with the right, although they are used differently across the political spectrum, while the same applies to socialism on the left. Despite their different prevalence depending on the political position, as demonstrated before (associating racism with the right is heavily dominated by left-wing individuals, while associating nationalism with the right seems to be less exclusively accomplished by left-wing individuals), they are clearly associated with either the left or the right. Hence, they present clear indications of left and right.

The continuous character of the positional horizontal dimension also applies to the semantic vertical dimension. An association can be ‘more left’ or ‘more right’. If individuals associate both justice and socialism equally often with the left, they are semantically both equally left, regardless of the diverging political positions of the individuals. Justice has a more positive connotation than socialism, so the former is hence more prominent for left-wing individuals, while the latter is more prominent for right-wing individuals to associate with the right, respectively. The proximity of the words, depending on their overall association and thus linguistic usage, matters in this dimension, while the individual left-right position does not, at least not primarily.

One can think of associations that are representative of the left and right and hence comparable semantically by ‘how left’ and ‘how right’ they are. If socialism is as strongly associated with the left as conservatism is associated with the right, and both terms are used equally by both left- and right-leaning individuals, then they are comparable in their semantic representativeness for the left and right, respectively. However, the question regarding the dynamics in the centre of the semantic dimension remains.

What happens in the centre?

In contrast to the introduced ideological associations that are clearly related to one pole, such as socialism and conservatism, there are also terms that are not ideologically informative, as they are used to describe in- or out-ideology to a similar extent by both left- and right-leaning individuals. From a conceptual standpoint, those terms are redundant regarding the left-right semantic dimension. For example, the term freedom has an inherent positive connotation and relates to both left (e.g., freedom as social participation) and right (e.g., economic freedom) associations (Ostrowski, 2023). There are also common terms in overall politics that should also play a prominent role in left-right associations with a less positive connotation. If people associate the left or right respectively with politics, policy, or mention the state per se, it is probably rather serving a descriptive purpose without communicating a concrete political stance or exclusive left or right meaning.

While Bølstad and Dinas (2017) see the role of the centre as dividing the political space into left and right by creating distinctive in-group biases, Ostrowski (2023) argues that the centre represents a distinctive ideological pole associated with, for example, liberalism. Ultimately, my framework captures both notions—the spatial categorisation that affects divergent associations that can be located distinctively to the left and right, but also the centre as a separate ideological space given positional and semantically neutral associations.

Associations can be equally (un)representative of left and right, but still have certain positional meanings. For example, the association of left and right with the state indicates a certain overall perception of the political system, which may be more prevalent for either left- or right-wing positions. It is important to distinguish the concrete positional differences for these ‘semantically neutral’ or ‘ideologically non-indicative’ associations.

If terms have a positive connotation, such as freedom, and are used by both left- and right-leaning individuals to associate with their in-ideology, this should be reflected in the left-right position distribution. Positive connotations with the left should be more pronounced for left-leaning positions, while positive connotations with the right should be more prominent for right-leaning positions. The reverse should be true for associations with negative connotations that are also used to describe both left and right, while certain associations, such as the state, or general references to the political system, should have a more neutral connotation that should reflect an equal left-right position distribution. The empirical investigation includes a specific section on the identification and positional assessment of the ideological semantic centre.

Mapping left-right associations

Open-ended survey associations with left and right: the case of German federal election candidates

There are several reasons for choosing Germany as an interesting and appropriate case for studying ideological associations in a dynamic context. The availability of high-quality GLES candidate surveys over three consecutive election cycles provides a comprehensive and longitudinal view of the political landscape GLES (2014, 2018, 2023a). The entry of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a radical right-wing party, into parliament in 2017, at a time marked by the migration crisis, adds an interesting dimension to the analysis (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019). The richness of the data, characterised by representative and stable indicators pooled from three survey waves, enhances the validity of the findings. One can extrapolate the characteristics of Germany’s party system to other Western European systems to a certain extent, as the party system has increasingly been shaped by multi-party fragmentation in recent years (Bräuninger et al. 2019). Federal election candidates as political elites are particularly suitable for the analysis of left-right associations due to their high level of political sophistication regarding ideological dynamics, as demonstrated before (Gallina, 2023; Lupton et al. 2015). Their understanding of ideology and the left-right continuum reflects established ideological patterns that can be effectively modelled.

The open-ended survey questions ask distinctly about descriptions with left and right (two items per survey), with the following question: ‘Can you please briefly describe what the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ stand for in politics today?’ (German: ‘Nun zur letzten Frage: Können Sie bitte kurz beschreiben, wofür die Begriffe ‘links’ und ‘rechts’ in der Politik heutzutage fur Sie stehen?’). Previous research has shown that asking for descriptions evokes specific associations that vary across contexts (Jankowski et al. 2023; Warode, 2025). The average number of words for the left item is 7.9 and 7.3 for the right item, indicating the concise and associative nature that justifies a term-focused research design.

After removing entries with missing values, the final sample includes 900 respondents for the 2013 wave, 700 for the 2017 wave, and 735 for the 2021 wave. Importantly, while the anonymity of respondents is preserved to prevent the identification of specific candidates, the samples are representative of the elected parliament, providing a robust basis for analysis (Zuell and Scholz, 2019). The data by party do not perfectly reflect the distribution of seats in the German Bundestag, but offer a sufficiently large sample size for each group. Smaller groups in the parliament, such as the Bavarian CSU, are also the smallest in the sample. Despite the sample’s minor discrepancies from the actual Bundestag, the average number of respondents per party over these years is 106, with a median of 118. The primary aim is to make claims on an aggregate level, making the sample appropriate for this purpose. Open-ended survey questions often face higher rates of item nonresponse than other types, influenced by factors such as the complexity of the question and respondents’ willingness to engage. In this study, the nonresponse rate for the open-ended question about left was 20.5% in 2013, 12.8% in 2017, and 19.9% in 2021. For the right item, the nonresponse rate was 20.8% in 2013, 13.1% in 2017, and 20.1% in 2021. These rates are relatively modest and balanced across waves and categories, facilitating a robust analysis of the responses provided (Millar and Dillman, 2012; Miller and Lambert, 2014; Scholz and Zuell, 2012; Zuell and Scholz, 2019).

Using word embeddings and left-right positions to project a left-right semantic space

The analytical framework employs word embeddings to map the semantic space of responses. Word embeddings, which form the foundation of modern large language models (LLMs), represent words as vectors in a semantic space (Mikolov et al. 2013; Palmer, 1981). Words with similar meanings are closer in this vector space, as word embeddings by default reflect linguistic patterns based on common language usage. Various powerful embedding-based models have proven effective in political research, as demonstrated by e.g. Rheault and Cochrane (2020); Rodriguez and Spirling (2022), who used these methods to assess party placements and ideological dimensions over time. For this study, I use the pre-trained BERT-based model bert-base-german-casedFootnote 4 to generate the word embeddings. This model is particularly suited for analysing German language text, and its transformer-based architecture and extensive pre-training make it capable of understanding linguistic patterns across domains (Vaswani et al. 2017).

The default semantic space that is represented by word embeddings reflects the linguistic context; hence, there is no distinctive representation of political or ideological semantics as presented in the theoretical model. For this reason, I include indications of political ideology through left-right semantics and left-right positions in the research framework. This procedure makes it possible to identify whether a term is genuinely associated with the left or the right—particularly relevant for ambiguous terms—and whether it reflects an in-group or out-group ideological perspective. This allows for a two-dimensional mapping of ideological language that supports interpretability and validity across a range of associations. It is important to acknowledge that the framework is limited to a word-based unit of analysis, as the aim of this paper is to measure and explore specific associations that are systematically mapped within the left-right continuum. Hence, rather complex constitutions of ideology that encompass a bundle of elements, such as values, policies and other concrete world views, are not particularly studied in this framework. However, through the aggregated view of the applied systematic mapping of individual word associations, constitutions of ideology emerge, and positional as well as semantic proximities can be comprehensively compared.

The preprocessing steps were rather limited. For consistency of associations, all text data was converted to lower case, and stop words were removed after the embedding model was applied to remove irrelevant terms from the final analysis. To present the results, I automatically translate all the words displayed from English to German using the R package polyglotr (Iwan, 2025). For certain words, I adjust the manual translation to be more appropriate in the context of political ideology. Compared to other word embedding frameworks such as the original word2vec (Mikolov et al. 2013) and fastText (Bojanowski et al. 2017), BERT leverages the powerful transformer infrastructure (Vaswani et al. 2017) and scales well with large amounts of text data to provide a more comprehensive standard approach to language. Given that open-ended survey responses are quite short compared to other sources of political text, such as parliamentary speeches or party manifestos, I rely on the pre-trained richness of BERT in this context.Footnote 5 I validate the model relying on pre-trained German BERT embeddings with pre-trained German fastText embeddings.

To map the ideological associations in a positional space (reflecting the x-axis of Fig. 1, I simply calculate the mean left-right self-placement for every individual who has used a specific word in the left and right association responses, which yields a left-right positional indication per word. The different left-right positions per word association reflect the different connotations that ideological connotations carry (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023), based on their role as either in-group or out-group associations (Bølstad and Dinas, 2017; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019). Left-leaning individuals associate the left with rather positive connotations and the right with rather negative connotations, while right-leaning individuals associate the left with rather negative connotations and the right with rather positive connotations. As some word associations occur in both the left and right items, I rely on a word frequency weighted left-right self-placement mean reflecting the relative proportions.

The left-right semantic association (the y-axis of Fig. 1) projection is a bit more complex. I use the following steps to unify the left and right word embeddings into a single dimension that reflects ‘how left’ (bottom) and ‘how right’ (upper) words are by incorporating embedding similarity and relative frequency:

-

1.

Mean vector computation: Mean word embedding vectors are computed separately for left and right association embeddings. These vectors are weighted by word frequency, giving more influence to frequently occurring words, thereby emphasising prominent word associations in the overall left and right mean vectors. This step forms the basis of the bipolar left-right semantic space by creating a semantic representation based on aggregated ideological associations.

-

2.

Embedding space unification: Left and right word embeddings are then integrated into a combined space, where terms appearing in both left and right associations are averaged (e.g., common associations like ‘politics’), allowing for a unified representation across both semantic orientations. The unification of left and right associations, based on two separate survey items, represents the ideological synthesis that is the foundation for mapping associations in one semantic dimension. Treating co-occurring associations (those that appear in both left and right associations) by averaging them ensures that associations that are not specific to either left or right receive a more neutral semantic meaning, proportional to how much they are used to describe left or right, respectively.

-

3.

Left-right association scoring: Left-right association scores are calculated by determining the cosine similarity of individual word embedding vectors with both the left and right mean vectors. The final association score is obtained by subtracting the left similarity value from the right similarity value. Relying on cosine similarity is a well-established approach to identifying similarity for embeddings, as direction is important, which is not reflected in other measures such as magnitude. Furthermore, cosine similarity is scale invariant and produces normalised values in a computationally efficient and robust manner.

-

4.

Frequency weighting: These scores are further refined by applying a frequency weighting parameter ranging from 0 to 1. A value of 0 gives full weight to cosine similarity alone, while a value of 1 gives full weight to word frequency, allowing for flexible adjustment based on analytical requirements. I rely on a default value of 0.5 for the following analysis. Relying equally on the relative frequencies from three pooled waves alongside the standard semantic values derived from the embeddings ensures that left-right word associations are representative of both ‘raw semantics’ and their relative importance in ideological associations. I present construct validity checks for different values of the frequency weighting parameters, along with BERT and fastText derived scores (Fig. 8).

-

5.

Score normalisation: Finally, the ‘semantic association scores’ are normalised on a scale from -1 to 1, where -1 indicates a left semantic association and 1 indicates a right association. The normalisation ensures that the scores are interpretable on a dimension that maintains relative proportions, as a true 0 value also indicates semantically neutral word associations.

Results

Descriptives

The first part of the results section presents descriptive statistics and visualisations to provide a basic understanding of the data. In order to justify the case selection and the focus on elites (candidates), Fig. 2 shows how left-right self-placement, the central variable next to left-right open-ended survey response indications, correlates with central policy issues for both candidates (GLES, 2014, 2018, 2023a) and citizens (GLES, 2019a, b, 2023b) in the German federal elections of 2013, 2017, and 2021.Footnote 6

Overall, a higher left-right self-placement is correlated with a preference for lower taxes, more restrictive migration policy and less emphasis on climate change. The first redistributive tax issue is representative of the classic economic left-right dimension, while migration and climate-related issues represent the cultural left-right dimension (Kriesi et al. 2006). Figure 2 shows that the correlation of left-right self-placement, as well as the correlation of issues with each other (intra-issue correlation), is substantially higher for candidates than for citizens in all three waves of the survey. Moreover, the highest correlation found for citizens, between the issue of climate and migration in 2021 (R = 0.48), is lower than the lowest correlation found for candidates (the issue of climate and migration in 2013, R = 0.49). More importantly, there is a consistent correlation of left-right self-placement with the three policy issues, ranging from R = 0.55 to R = 0.79 in absolute terms.

This brief examination of the left-right scale and policy issue correlations shows a) that there are strong associations between the left-right dimension and key policy issues, and b) that elites have a much higher and more consistent association of the left-right dimension with policy issues than citizens. Therefore, this justifies the case selection of elites for the systematic study of the left-right continuum in a unidimensional way, confirming the findings of previous studies (Gallina, 2023; Lupton et al. 2015).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of left-right self-placement across different political parties for the years 2013, 2017, and 2021. The left-right self-placement ranges from 1 (‘left’) to 11 (‘right’) and asks respondents to place themselves within this integer range. This figure illustrates how respondents from various parties position themselves on the ideological spectrum, with mean (at the right end of the distribution) and median (vertical lines within the distribution) values indicated for each group.Footnote 7

The candidates are ideologically representative in terms of their left-right distribution according to the German party system (Jolly et al. 2022). I would like to stress that they are not necessarily representative of the elected MPs and the entire candidate pool, which would be particularly important for individual-level causal estimation frameworks, which is, however, not the aim of this paper. Rather, they represent valid representations of German party elites by corresponding to ideological party positions over three consecutive survey waves, as the purpose of this paper is to rely on valid aggregated indications of left-right ideology.

In Fig. 3, the centre-left SPD and centre-left Greens generally position themselves towards the left, while the liberal centre-right FDP and Christian democratic/conservative centre-right CDU/CSU are situated more towards the centre and slightly to the right. Left-wing DIE LINKE remains consistently on the far left, and the far-right AfD moves increasingly to the (far-)right. This distribution provides a solid basis for further analysis of ideological associations and confirms distinct ideological self-placements among German political elites.Footnote 8

Figure 4 uses dimensionally reduced (PCA) word embeddings to demonstrate the semantic proximity of the respective most prominent 50 associations per left and right.Footnote 9 The model bert-base-german-cased is used to map these terms in a semantic space, illustrating how closely related ideological concepts cluster together. As shown in the figure, ‘socialism’ and ‘nationalism’ are semantically close, indicating a strong linguistic association, despite their distance in established ideological dimensions. Socialism is typically located at the left-wing spectrum of politics, while nationalism is associated with the right. Similarly, terms like ‘social’ and ‘national’ also show proximity, suggesting that these ideological attributes are contextually linked in a similar fashion.

These descriptive statistics directly motivate the synthesis of left-right associations and left-right position. Without the positional context and without an indication of ‘how left’ and ‘how right’ those words are in relative terms, the research question cannot be fully answered. First, without integrating left and right associations into one-dimensional space, there is no concrete indication of whether a word is actually associated with left or right. While this seems rather redundant in the context of ideological associations like socialism and conservatism—which are clearly attributable to left and right—it is likely to become increasingly relevant for more vague associations that individuals use to describe both ideological poles. Second, without integrating the positional component that incorporates the connotation, it remains unclear whether the associations were motivated by an ‘in-group’ or ‘out-group’ individual and hence reflect in- or out-ideology associations. The results demonstrate how the integration of left-right associations into one semantic dimension and the political position dimension yields a two-dimensional map of ideological associations in the context of in- and out-ideology. I specifically concentrate on the most prominent associations that are essential for facilitating validity and interpretability.

Exploring patterns of in- and out-ideological associations with left and right

Figure 5 displays the results of the methodological application uniting left and right associations and the underlying left-right positions into a two-dimensional space. By incorporating the most common 35 words per left and right item, the scatter plot provides an insight into how different ideological terms are associated based on the mean left-right self-placement value of individuals who have used the term in their response on the x-axis and the left-right semantic dimension on the y-axis. I focus on the most common words, in this case the overall top 35, for reasons of representativeness—as the application of the model to the pooled empirical base aims to identify salient and representative indications of ideological associations—and for reasons of effective visual communication—as visual space is limited before the mapped associations become illegible. Figure A1 in the Online Appendix shows the distribution of all word associations derived from pooled open-ended survey responses, and effectively shows that the used model with the default specification—relying on pre-trained German BERT embeddings and using a frequency weighting parameter of 0.5—effectively produces left, right and neutral clusters in both semantic and positional terms, as desired by the theoretical demands. In the following sections, I present validation frameworks that include more words and assess model performance and results with other model specifications and external data sources.

Vertical dotted lines indicate the overall left-right self-placement mean of the top 35 associations only (dark grey) and all associations (light grey). Horizontal dotted lines indicate left-right semantic association score means for the top 35 associations only (dark grey) and all associations (light grey). GLES candidate surveys 2013, 2017, and 2021.

Continuing with the visual interpretation of the results, ‘semantically left’ terms are at the bottom, while ‘semantically right’ terms are located at the top. The upper left quadrant reflects out-ideological associations from left-leaning individuals about the right, while the upper right quadrant represents in-ideological associations from right-leaning individuals about the right. The bottom left quadrant reflects in-ideological associations from left-leaning individuals about the left, and the bottom right quadrant features out-ideological associations from right-leaning individuals about the left. The vertical and horizontal lines represent the respective mean values that serve as a marker to signal the boundaries of the ideological quadrants.

In the bottom left quadrant, we find terms like justice, peace, social, solidarity and tolerance, which are indicative of left in-ideological associations. These words reflect positive core values often associated with left-wing ideologies, and also confirm the theoretical expectations. Conversely, the bottom right quadrant is characterised by left-out-ideological associations, featuring terms such as paternalism, egalitarianism, socialism, and socialist. These terms, while associated with left ideology, often carry more complex or negative connotations, particularly in discussions around state intervention and equality. In addition, terms like welfare state and redistribution are also present, but with a less right-leaning and hence less negative connotation, underlining the continuous positional character and justifying the model’s capabilities of projecting non-categorical indications.

Importantly, socialism (alongside socialist) as a central left-wing ism is present as an out-ideological association, confirming its hypothesised role as a central negative representation in ideological language. It is important to note, however, that this does not mean that socialism has no role for left in-ideological associations in general. Rather, it shows that socialism is more salient for left out-ideological associations, relating to how right-leaning elites frame the left—in a negative way (Chong and Druckman, 2007). This finding extends our understanding of issue ownership (Budge, 2015) in ‘negative ideological’ terms and speaks to the decisive differences, how elites communicate political issues, e.g., in social media and legislative debates (Gilardi et al. 2022; Lau and Rovner, 2009; Sältzer, 2022).

Prominently positioned in the upper left quadrant are terms such as fascism, racism and racist, nationalism, conservatism and conservative, indicating a strong association with right-wing ideologies. These terms have a high ‘right semantic association’, but align with left-leaning positions, resulting in out-ideological associations. In addition, within-quadrant variation exists and confirms the theoretical expectation as the out-ideological associations fascism and racism are characterised by more left-leaning positions than nationalism and conservatism are. Conservative and conservatism as associations have higher mean left-right self-placement values, reflecting their less negative connotation and more neutral or partly ideologically neutral usage.Footnote 10

An intriguing dynamic emerges in the upper right quadrant, which is almost empty compared to the other quadrants. The ‘global’ top words barely feature in the in-ideological right-wing context. This uneven distribution of top words across the quadrants suggests a potential disconnect or divergence in the semantic associations that typically characterise right-wing ideologies, highlighting unique patterns in ideological language use. Right-wing in-ideological associations appear less unified and less prominent compared to other associations, which is an interesting finding with theoretical implications related to the German context and its political legacies. Specifically, far-right ideologies, such as fascism, have significantly influenced how the label right is employed in contemporary German (elite) discourse (Sierp, 2014; Warode, 2025).

Building on the dynamics observed in the upper right quadrant, where the ‘global’ top words barely feature in the in-ideological right-wing context, it is crucial to accurately identify representative words for the four quadrants as depicted in Fig. 1. To do this, I consider associations as left-leaning if their left-right self-placement mean value is below 0.5 standard deviations of the global left-right self-placement mean and right-leaning if their left-right self-placement mean value is above 0.5 standard deviations of the global left-right self-placement mean. Analogously, I consider associations as semantically left if they deviate by at least 0.5 standard deviations below the semantic association score mean, and as semantically right if they deviate by at least 0.5 standard deviations above the semantic association score mean.

Quadrant-based top words are essential for understanding asymmetric ideological association landscapes. Figure 6 illustrates the 15 respective top words (60 in total) for each of the four quadrants that meet the quadrant identification criteria, providing a separated representation of the most prominent ideological terms for left and right in- and out-ideological associations. This approach provides a detailed understanding of ideological term usage.

Vertical dotted lines indicate the overall left-right self-placement mean of the top 60 associations only (dark grey) and all associations (light grey). Horizontal dotted lines indicate left-right semantic association score means for the top 60 associations only (dark grey) and all associations (light grey). GLES candidate surveys 2013, 2017, and 2021.

In the upper right quadrant, a clear depiction of right in-ideological associations emerges, including terms like patriotic and patriotism, home(land), rule of law, family, personal responsibility and performance principle. The associations capture both economic and cultural value characteristics of right-wing ideology. Interestingly, the term ‘right-wing extremist’ appears in this quadrant, which is characterised by its negative connotation and contrasts with the generally positive terms present, highlighting a complex dynamic that potentially distinguishes centre-right from far-right associations. Meanwhile, the other quadrants overall maintain their previous configurations, illustrating consistent ideological associations according to the in- and out-ideological characteristics. Considerable additions are market and anti-Semitism as further out-ideological associations with the right, and ‘ideology’ as an out-ideological association with the left. While anti-Semitism is not unexpected given its negative connotations and similarity to other negatively associated isms such as fascism and racism, market refers to descriptions of economic elements, where one could also assume rather neutral and positive connotations. The term ‘ideology’ on its own apparently has a negative connotation and is associated with the left. This is a very interesting finding, reflecting the inherent negativity of associations that refer to the concept of ideology itself. It is also interesting that ideology is associated with the left and not with the right, while the ‘negativity of ideology’ corresponds to the negativity of ideological isms, both on the left and the right. Further research should investigate this dynamic in a more detailed manner.

Neutral associations or centrist ideology?

Until now, much of the analysis has bypassed the ideological centre; hence, distinctively examining ‘semantically neutral’ words addresses this gap. Semantically neutral or ‘centrist’ terms are used to describe both the left and the right, and are therefore non-discriminatory and non-ideological in terms of whether a term is associated with the left, such as socialism, or the right, such as conservatism. Conceptually, semantically neutral words are identified by a central semantic association score, which represents the middle or second tertile (−0.33 < semantic association score <0.33; as shown in the Online Appendix Fig. A1). The theoretical discussion before has shown that there are diverging notions regarding the role of the ideological centre. Bølstad and Dinas (2017) conclude that the centre essentially acts as a spatial divider, separating left and right from each other. Ostrowski (2023) emphasises the distinct role of the centre in terms of ideological manifestations, for example, populated by liberalism, but also acknowledges that it is much less clear compared to the left and right.

Both notions of the centre—the centre as a divider and the centre as an ideological pole—can be manifested in ideological associations. However, it is empirically difficult to identify its categorical meaning within the given research framework. By analysing the context of political position separated by whether individuals associate centrist or semantically neutral terms with either left or right, we can assess the connotations these terms carry in different contexts, thereby enriching our understanding of their variable role within ideological associations. In this context, Fig. 7 shows the distribution of left-right self-placement for the top six, based on total frequency, semantically neutral words: staat (‘state’), menschen (‘people’), politik (‘politics’ and/or ‘policy’), freiheit (‘freedom’), wirtschaft (‘business’), and verantwortung (‘responsibility’).Footnote 11 Each panel presents a density plot where the red distribution corresponds to the associations of the word with the left, and the blue distribution corresponds to the associations with the right. The vertical lines within each distribution indicate the mean values of left-right self-placement when the word is mentioned to associate with the left or the right, respectively. The horizontal line connecting these vertical lines represents the difference between these means.

The red distribution represents associations of the word with the left, while the blue distribution represents associations of the word with the right. The mean values of the left-right self-placement of the left and right associations are indicated by the vertical line, and the difference between the two means is indicated by the connected horizontal line. GLES candidate surveys 2013, 2017 and 2021.

The figure demonstrates terms that maintain a balanced presence across the ideological spectrum, underscoring their neutral character. However, there is interesting left-right positional variability in the word associations. The most prominent neutral word association, state, is used by individuals who have a rather higher left-right self-placement value, both when they associate state with the left (\(\bar{x}=6.02\)) and the right (\(\bar{x}=5.85\)). The distance between the two mean values is low (0.17).

The second and third most prominent neutral word associations, people and policy/politicsFootnote 12 have a lower left-right self-placement mean for both left and right compared to state, but also no variability in terms of the left-right self-placement when associated with both left and right.

Freedom, the fourth most prominent neutral word association, exhibits a different dynamic. When individuals associate freedom with the left they have a lower left-right self-placement (\(\bar{x}=3.55\)), while individuals associating freedom with the right have a higher left-right self-placement (\(\bar{x}=6.56\)), which translates into a high distance of 3.01. Both rather left-leaning and rather right-leaning individuals associate freedom with their in-ideology. As theorised before, this can be explained by the positive connotation of freedom compared to other terms with a rather neutral or even negative connotation (Ostrowski, 2023). While a thorough analysis of the further associational context is beyond the scope of this paper, I expect that the respective positive connotation materialises around different patterns of associational co-occurrence. For the left, this could be expressed in the perception of freedom as freedom of life choices and social participation, while for the right, the positive connotation and perception of freedom could be expressed in an understanding of economic and market freedom.

‘Liberal’, shown in Fig. A3 in the Online Appendix, shows the same pattern of positive connotations as freedom. Given that liberal also plays a decisive role in the formation of political ideology in the tripolar scenario with conservatism, socialism, and liberalism as the main poles of political ideology, in particular from a historical perspective (Kurunmäki and Marjanen, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023), it is interesting that left-leaning individuals associate liberal with left and right-leaning individuals with right which implies a rather positive connotation.

Future research should analyse the associations and perceptions of these ‘ism-related’ centrist terms, as they are likely to play a significant role in politics, for example, the liberal FDP could ‘own’ the label of liberal(ism), related to the notion of issue ownership, but in an ideological context (Budge, 2015). In addition, the framing of ideological terms, such as liberal(ism), is a central aspect of political communication at the elite level, with downstream consequences for political representation and agenda setting (Gilardi et al. 2022; Lau and Rovner, 2009). As Ostrowski (2023) points out, both the (centre-)left and the (centre-)right are typically associated with liberalism, with the former referring to ‘social liberalism’, and the latter to ‘market liberalism’. Going one step further, ‘social liberalism’ tends to reflect cultural issues and ‘market liberalism’ tends to reflect economic issues (Kriesi et al. 2006), but further analyses of left-right multidimensionality are beyond the scope of this analysis, and clearly relevant targets for future research agendas.

The fifth most prominent neutral word association, economy, tends to reflect the neutral association pattern of state, people and politics/policy, but also exhibits a slightly negative connotation pattern, as rather right-leaning individuals mention the economy in their associations with the left and rather left-leaning individuals associate economy with the right. This is however rather marginal compared to the pattern around freedom. The context is probably decisive, as associational patterns around the economy could heavily vary by perception and framing.

Responsibility, as the sixth most prominent association, shows a similar pattern to freedom, reflecting the positive connotation and ideological reflection. This suggests that while these terms are neutral in meaning, their associations are more polarised, potentially reflecting the theoretical expectations. The clear separation in their distributions indicates a connotation divergence in how left- and right-leaning individuals perceive these concepts. Overall, the figure provides empirical support for the theoretical arguments and illustrates the complex dynamics of neutral word associations within the ideological landscape.

Construct validity: comparing semantic association scores from BERT and fastText

As emphasised above, the empirical strategy depends on a valid representation of semantics to successfully measure ‘how left’ and ‘how right’ word associations are. To test the validity of the left-right semantic association dimension, I present different model specifications in Fig. 8 by a) modifying the frequency weighting parameter and b) replacing the pre-trained German BERT embeddings with pre-trained German fastText embeddings (Bojanowski et al. 2017).Footnote 13 Specifically, I correlate the resulting association scores for all models based on BERT and fastText embeddings with frequency weighting parameters of 0, 0.5, and 1, respectively.

Figure 8 shows the association scores for the 50 most prominent associations (in terms of frequency), showing a highly significant correlation between all model specifications, ranging from R = 0.606 to a perfect correlation of R = 1. To recapitulate, frequency weighting parameters of 0 give full weight to the cosine similarity, while values of 1 give full weight to the weights derived from the frequencies derived from the pooled associations of open-ended survey responses. In particular, the models with frequency weighting parameter values of 0.5 and 1 correlate strongly with each other, which is also reflected in the bimodal distributions of those specifications that rely on the model dynamics to construct semantically left and right clusters depending on the empirical frequencies, which is indeed a desired property. I conclude that (1) a sufficiently high (e.g., 0.5, which I used in the analysis) frequency weighting parameter should be considered as appropriate to properly reflect the empirical shape of left-right associations, and that (2) the construct validity of the semantic association dimension is sufficiently demonstrated given the high correlations of different measurement option specifications.Footnote 14

External validity: using in- and out-ideological words to scale parliamentary speech

In this section of the analysis, I focus on the external validation of the research framework by scaling political text. By using Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS), a semi-supervised machine learning model that provides polarity scores to words by estimating semantic proximity through word embedding algorithms (Watanabe, 2021), I validate the theoretical model of left-right in- and out-ideological associations using German Bundestag speeches from the 19th legislative period (2017-2021), which were obtained from the Open Discourse database (Richter et al. 2023).

I use the most prominent in-ideological and out-ideological word associations to scale parliamentary speeches by MP and compare the results on a party (parliamentary group) level. In detail, I conduct a dichotomised analysis by distinguishing between in-ideological and out-ideological associations to test their external validity separately. Parliamentary speeches are characterised by several institutional factors, such as strategic incentives for speakers (Benoit et al. 2009) and the government-opposition divide (Hix and Noury, 2016), which could impede the effective applicability of ideological language for scaling political actors. The following scaling application can therefore be considered a ‘hard test’.

Figure 9 shows the distribution of LSS scaling estimates by using the top 15 in- and out-ideological associations as seedwords respectively, representing the in- and out-ideological associations from Fig. 6. I calculate the mean LSS estimate per MP, using every speech she or he held during the 19th legislative period in the German Bundestag.

The figure shows the predicted mean LSS scaling estimates per MP. GLES candidate surveys 2013, 2017, and 2021 and Bundestag speeches from the 19th legislative period, 2017-2021 (Richter et al. 2023).

The analysis validates the in- and out-ideological differentiation approach by showing its applicability in scaling political text. The left plot shows the distribution of the LSS estimates for the model with in-ideological (positive) associations with left and right, while the right plot indicates the same for out-ideological (negative) associations. In other words, the LSS models confirm the approach of using in-group and out-group associations about left and right to scale external political text. The left plot shows strong in-ideological alignment for the far-right AfD (mean: 0.318), with CDU/CSU (mean: 0.071) and FDP (mean: 0.169) also showing positive alignment. In contrast, the SPD (mean: −0.181), the Greens (mean: −0.200) and DIE LINKE (mean: −0.268) have negative LSS estimates on average. The in-ideology seedword approach confirms that political speech can be scaled by ‘how left’ and ‘how right words’ are in terms of left and right positively connoted in-group associations.

The right plot shows a substantive out-ideological divergence for the AfD (mean: 0.519), with FDP (mean: 0.073) and CDU/CSU (mean: 0.030) on the right side as well. The SPD (mean: −0.111), the Greens (mean: −0.157) and DIE LINKE (mean: −0.226) show negative out-ideological associations scores. Out-ideology seedwords relate to the inverse of the in-ideology by indicating negative connotations. However, the model does not discriminate perfectly across party lines in both scenarios, as the distributions show intersections in their ideal point estimates. Still, the model does correspond to the one-dimensional left-right positions of German parties (Jolly et al. 2022). On a general left-right scale, the FDP is usually to the left of the CDU/CSU, but the in- and out-ideological associations scale them to the right.

Calculating the total difference between the highest and lowest estimates, the in-ideology difference between AfD (0.318) and DIE LINKE (−0.268) is 0.586. For out-ideology keywords, the difference between AfD (0.519) and DIE LINKE (−0.226) is 0.745. This indicates that the out-ideology seedword model shows a greater spread and is more discriminative in LSS estimates, highlighting in particular the significant divergence of the AfD from the opposing ideologies. This underlines the powerful role of out-ideology or ‘negative ideology’ in the context of political discourse (Abramowitz and Webster, 2016, 2018; Ostrowski, 2023; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019).

Figure 10 shows where the respective seedwords are mapped in the in- and out-ideological models by displaying the polarity scores (which are aggregated by MP in Fig. 9) and their (log) frequency in the speech corpus. The polarity scores depict the left-right continuum in parliamentary speech. The left side presents the in-ideological associations, the right side the out-ideological associations. While the associations differ in frequency—reflecting their salience in parliamentary discourse—they correspond strongly to their theoretical expectations in both models. For in-ideological language, in-ideological left associations correspond to left (low) polarity scores, while out-ideological associations with the right correspond to right (high) polarity scores. The pattern is flipped, as theoretically expected, for out-ideology: Out-ideological associations with the left are related to right (high) polarity scores, while right out-ideological associations correspond to left (low) polarity scores.

The figure shows the respective seedwords and their LSS polarity scores (x axis) and their logarithmic frequency in the speech corpus (y axis) per word association. GLES candidate surveys 2013, 2017, and 2021 and Bundestag speeches from the 19th legislative period, 2017-2021 (Richter et al. 2023).

The Online Appendix also presents LSS models with the respective top 5, top 15, top 35 and top 50 in- and out-ideological seedwords, providing additional validation in line with the top 15 model (Fig. A5). The LSS scaling application confirms the theoretical model, showing the strong in-ideological alignment of the AfD and the significant out-ideological divergence of the AfD, providing a comprehensive view of ideological associations in parliamentary speeches.

Discussion

This contribution advances the study of political ideology by exploring associations with left and right in a novel way through analysing open-ended survey responses and political position indications of German federal election candidates from three pooled consecutive survey waves (2013, 2017, and 2021). The theoretical model presented has two dimensions that reflect a) the political position of an association and b) the left-right semantic dimension, which indicates ‘how left’ or ‘how right’ an association is through its associational utilisation. By distinguishing between in-ideology (left-leaning individuals associating with left and right-leaning individuals associating with right) and out-ideology (left-leaning individuals associating with right and right-leaning individuals associating with left), I show how ideological term usage varies across the political spectrum. The empirical model projects left-right associations into a two-dimensional continuous space by considering a) the mean left-right self-placement of individuals when they use a word to associate left-right ideology, and b) the semantic dimension, ranging from ‘left semantics’ to ‘right semantics’, through relative frequency and embedding-based semantic similarity for single word associations, reflecting how representative a word is for left or right associations respectively. The main finding is an empirical confirmation of the theoretical assumption that different political positions systematically affect diverging associations with left and right.

The analysis reveals several remarkable dynamics. The main mechanism shows that left-right associations vary across the political spectrum. Left in-ideological associations feature prominently values like ‘justice’, ‘solidarity’ and ‘peace’ with a positive connotation. Out-ideological associations related to the left highlight the prominence of ideological isms, like ‘socialism’, but also ‘paternalism’ and ‘egalitarianism’. In-ideological associations are driven by positive connotations, out-ideological associations by negative connotations. The mechanism also encompasses out-ideological associations with the right. ‘Racism’, ‘fascism’ and ‘nationalism’ are out-ideological isms that are prominently associated with the right, while ‘conservatism’ is used from a less ideologically neutral position on average. Looking only at the overall most frequent word associations, clear right-wing ideological associations are rare. Positive associations with the right are less prominent in terms of overall frequency and less congruent than positive associations with the left. A further step of the analysis focusing on right-wing in-ideology reveals associations that emphasise ‘patriotism’, ‘rule of law’ and ‘personal responsibility’.