Abstract

This study employs global survey data and multilevel linear models to analyze the effects of contextual factors on intergenerational educational mobility across 49 countries. The first conclusion is that the educational mobility-promoting effects of economic development are stronger in nations with lower levels of inequality than in nations with higher levels. As income inequality rises, its mobility-inhibiting effect would outweigh the facilitation of economic development, implying that income inequality hinders socioeconomic development’s efforts to positively enhance educational mobility. The second is that women’s intergenerational educational mobility is more strongly influenced by macro factors than men’s. When the external social environment improves, women would have more mobile educational attainment and when the social environment deteriorates, women’s educational solidification grows rapidly. The third is that socioeconomic inequality restricts mobilities for the older cohort more noticeably, whereas the younger cohort benefits more from the expanded educational opportunities brought on by economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intergenerational educational mobility (IEM), an indicator depicting the influence of parental education on their children’s education, is widely recognized for its fundamental association with educational opportunity, significant impact on the acquisition of status, and structural reflection of social fairness (Corak, 2013). Higher IEM implies lower intergenerational educational association or persistence, suggesting a more equitable educational environment that enables individuals to transcend their family background. Conversely, lower IEM corresponds to higher educational persistence, where parental education strongly predicts children’s educational attainment. This indicates a more rigid educational structure in which socioeconomic advantages or disadvantages are transmitted across generations, limiting opportunities for upward mobility and perpetuating inequalities.

What are the influencing factors of IEM and how about their influencing mechanisms? According to conventional studies of IEM in social mobility research, individual factors like gender, age at school entry, family economic circumstances, and parents’ employment status have correlations with intergenerational mobility of education in specific single countries (Lillard and Willis, 1994; Bauer and Riphahn, 2009; Kishwar and Alam, 2021), while macro factors like the process of industrialization or modernization, education policies, and the structure of social opportunities are used to explore the IEM variations across nations (Jerrim and Macmillan, 2015; Guo, Song and Chen, 2019). These studies concentrate on the factors’ direction and intensity in influencing IEM and make an effort to explain the underlying process from multiple disciplines.

We argue that the previous studies may be inadequate for understanding what would happen when IEM is subjected to complex social forces that have opposing effects. From the insights of economic development theory and social inequality theory on how social elements determine IEM (Treiman and Yip, 1989; Erikson and Goldthorpe, 1992), the former emphasizes the positive impact of economic progress on social mobility by raising the educational level of the entire society, and the latter focuses on the negative influence of social disparity which limits the educational attainment of lower social class. Along with the theories, extensive studies provide empirical evidence that a higher degree of intergenerational mobility is associated with a higher level of economic conditions (Neidhöfer, Serrano and Gasparini, 2018) while “the Great Gatsby Curve” concludes that more income inequality is linked with less intergenerational mobility (Krueger, 2012; Corak, 2013). A blended example points to the equalizing effect in Scandinavian countries which may be attributed to the educational chances diffusion brought by industrial growth and the lower educational barriers for working-class children brought by the social equality policies, thus, increasing mobility (Hertz et al., 2008; Esping-Andersen and Wanger, 2012; Esping-Andersen, 2015). The findings, however, are usually merged into the research for general social mobility, intergenerational income mobility, and intergenerational occupational mobility where education is assumed as an influencing factor rather than a study variable. More importantly, they do not clarify the inner association of the influences on IEM from the diverse contextual factors. We would like to know with two factors having opposite influences, which one is more likely to affect the degree of educational mobility, as well as their heterogeneous impacts among populations.

This study extends existing research in two ways. The first is proposing an integrated framework of social contexts on IEM. Building upon the industrialization thesis and inequality thesis, the model expands them by including the comparative analysis of the competitive moderating effects. We use the categorical perspective to show the mobility variations in countries with divergent social characteristics. The second is demonstrating the heterogeneous effects for gender and age groups in the integrated model. The previous research finds that the educational attainment of male and female, youth and older people is influenced differently by parental education (Bauer and Riphahn, 2009; Huo and Golley, 2022), but it did not go further in examining the differences in the intensity of contextual factors by age and gender.

Aiming to explore descriptive patterns and associations rather than to establish causality, the following analysis includes three steps. First, we analyzed data from the European Value Study (EVS) and the World Value Survey (WVS) that provided educational information about respondents and their parents in a wide range of nations/territories with different external social environments. We estimated the influencing strengths of macro factors on IEM in the integrated country-level mixed models, and used intergenerational educational elasticity, a concept denoting the percentage change in the children’s education for the change in the parents’ education. A higher value of intergenerational educational elasticity indicated stronger intergenerational relevance and education inheritance.

Secondly, we classified the countries of interest according to the level of economic development and social inequality, then, presented the effects of macro factors under different social scenarios. Research on the social influences of intergenerational mobility suggests that higher mobility is linked with higher economic development and less income inequality (Gugushvili, 2017), but sometimes the two conditions do not occur simultaneously in a single country. How is IEM in countries with high levels of inequality and high levels of economic development, or societies with low levels of inequality and low levels of economic development? Our study found that the mobility-promoting effect of economic development was constrained in countries with higher levels of social inequality.

Thirdly, we explored differences in the effects of macroscopic factors in gender and cohort subsamples. We argued that different genders and birth cohorts differ in the extent to which was associated with paternal education under the influence of macro factors, in contrast to earlier studies that focused on the relationship of the entire population. By presenting standardized sub-sample results, we showed that the educational mobility outcomes of groups were differentiated by varied social factors.

Theoretical framework

Conventional models of intergenerational educational mobility

Previous research on the influence of contextual factors on IEM across regions has developed two main theories: the economic development theory and the social inequality theory.

The economic development theory assumes that IEM would decrease when increasing the children’s educational attainment in the general society, especially the lower social classes and it contains two main hypotheses. The industrialization hypothesis holds two mechanisms of structural changes and social choice to lift the IEM (Lipset and Zetterberg, 1959; Erikson and Goldthorpe, 1992). The public support hypothesis is enlightened by the human capital models (Becker and Tomes, 1979) by arguing that the government’s public funding of education can make up for the lack of human capital investment in education by families with lower socioeconomic status (Roy, Basu and Roy, 2022). In empirical studies, economic development is usually measured by per-worker GDP or GDP per capita, and higher GDP per capita is associated with lower IEM (Yaish and Andersen, 2012; Neidhöfer, Serrano and Gasparini, 2018). People have higher educational outcomes in more developed regions with more public support investments (Aydemir and Yazici, 2019), otherwise, in a region with few public education scholarships and poor infrastructure, the educational persistence between generations is strong (Roy, Basu and Roy, 2022).

The social inequality theory assumes that IEM would rise when the polarization of the education level of children’s generation rises. The positive relationship between social inequality and IEM has two explanations: the educational resource inequality hypothesis and the cost-benefit of education hypothesis. The former believes that inequality concentrates wealth and resources in the upper social class and exacerbates stratified social outcomes originating from family traits, allowing social class with competitive privileges to provide resources, structure policies, and shape opportunities to ensure the persistence of education and occupation (Corak, 2013). The lack of adequate resources in the lower social class would result in children’s decreasing upward educational mobility (Wang and Wu, 2023). The sustain, even the expansion, of education inequality would increase IEM. The latter considers that inequality would increase closed social opportunity, making the cost-benefit ratio of educational investment in the lower social class even lower, so that they are more likely to refrain from taking risky chances (Jackson and Schneider, 2022). The level of IEM would be higher if lower-class children’s educational attainment remained constant or even declined, while upper-class children have higher educational attainment. Neidhöfer, Serrano, and Gasparini (2018) compared intergenerational educational persistence in Latin America and showed a significantly positive relationship with inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient of disposable household per capita income.

The industrialization theory, though, contains gaps in its justification that the link between modernization and IEM can only be observed in a nation with high levels of economy (Yaish and Andersen, 2012). This perspective tends to overlook constraints from social structures. The relationship between social inequality and IEM is also debatable. Liberal economists and structural-functional sociologists hold the view that social inequality encourages individuals to pursue higher levels of education and employment depending on skill and necessity through unequal incentives and rewards (Davis and Moore, 1945).

Incorporating the intrinsic connection between contextual factors’ effects on intergenerational educational mobility

Social inequality spans multiple dimensions and levels, such as digital skills gap, inequitable legal protections, wealth accumulation and poverty perpetuation, gender and racial discrimination, etc., encompassing disparities and unfairness arising from the unequal distribution of resources, power, opportunities, or social status (Goldthorpe, 2010; Raudenbush and Eschmann, 2015). The current study focuses on income inequality, which represents a significant aspect of social inequality, and examines how economic contexts influence individual educational opportunities and the disparities therein. The integrative and divisive forces embedded within the economic dimension of different countries shape the opportunities and constraints individuals in attaining education.

We contend that the previous theories show inconsistent or contradictory results for not incorporating the interrelation of the effects on IEM from social factors. The Kuznets hypothesis (Kuznets, 1955) explored the connection between economic growth and inequality, imposed a certain inverted U curve of income inequality over various stages of economic growth, and inspired research on the possible consequences of social structures (Naguib, 2017; Ail et al., 2022). What about the relations of their impacts on IEM?

The mechanism of structural change under the influence of income inequality. Economic growth drives structural transformation toward technocracy in the labor market and a rise in the educational level of society’s members. Those who initially succeed in seizing the opportunity of market-oriented reform and transform into new social elites are typically individuals with a prominent position in the distribution system and stronger cultural capital and social capital, which would increase the returns of family resources in terms of education and employment (Gerber and Hout, 2004; Yaish et al., 2021). And the rising income inequality would make the feature more pronounced. While higher-class children continue to enter highly skilled fields, the flow effect brought on by industrialization will be mitigated. It can be argued that the vertical segmentation of the labor market has concentrated the young generation of the lower class in jobs with less demanding educational attainment, constraining IEM.

The mechanism of social choice under the influence of income inequality. The growing income inequality shapes how opportunities are distributed in schools and labor markets, where social choice mechanisms primarily take place. In schools, teachers, as agents of the elite, evaluate students using the cultural norms established by the upper class. In the labor market, the lower-class young generations have fewer benefits of human capital because screening criteria for employers are equally dependent on educational attainment and abilities. They may only get employment identical to those of their fathers, restricting prospects for mobility. In conclusion, income inequality reinforces and even worsens the distribution of resources based on socioeconomic rank, the social choice process is subordinated to impediments to class mobility, and the bottom class only receives a limited amount of benefit from the development of meritocracy.

The mechanism of public support under the influence of income inequality. Jackson and Schneider (2022) stated that public spending on education, as a more universal investment, has a top-down effect on family education expenditures, i.e., public investment decreases the education expenditures of high-class households but does not change the expenditures of low-middle-class households. Currently, public education spending in most countries concentrates more on elementary and secondary education rather than tertiary education. When society becomes increasingly unequal, children from low families face fewer marginal enrollment opportunities and fewer options for higher education, and the free-up resources of public education expenditures are scarcely beneficial for them. Although progressive public policies anticipate a steady convergence of the education gap, this objective may be challenging to reach in an unequal society.

By distinguishing the level of income inequality, we assume that under the impact of wealth reproduction and class exclusion, the educational opportunity structure exhibits a trend of closure, similar to the conclusion of the Maximumly Maintained Inequality hypothesis (Raftery and Hout, 1993). Since previous studies have shown that the influences are skewed in the opposite direction, we believe that a comparative viewpoint made up of categorized contextual elements at the individual levels is effective in distinguishing the mixed effects. We propose the following hypotheses that with the increase in income inequality, the mobility-promoting effects of economic growth on IEM would be decreased.

Hypothesis 1a: The impact of economic growth on IEM is weaker in higher unequal countries than in lower unequal countries.

Hypothesis 1b: The impact of public support on IEM is weaker in higher unequal countries than in lower unequal countries.

Gender and cohort differences in the impact of contextual factors on intergenerational educational mobility

We find that previous studies only discuss whether IEM is high or low across groups but do not explore the heterogeneity of the degree of IEM influenced by macro factors across groups. Studies have been done on IEM differences related to gender (Huo and Golley, 2022) and age (Bauer and Riphahn, 2009) to explain the relative advantages of IEM in some privileged social groups. We consider IEM as the intergenerational variance in the educational status of social members. The concept offers a distinctive perspective of social incentives and resource distribution by combining family educational strategy and societal educational opportunity.

Regarding gender differences, the theories of rational choice, family resources, and gender roles assume education preference within the family because of the limited resources (Moen et al., 1997; Meemon et al., 2022). Structural change and social choice mechanisms seek efficiency and require a large labor force to create economic value to drive economic development, so more women are getting educated, participating in the labor market, and releasing themselves from the constraints of the family. Public support mechanisms enable government investment to compensate for the insufficiency of families that might only support boys for schools, making the “superfluous” educational opportunities now available to girls. Thus, the mobility-promoting effects facilitated by the economic development of women are more than that of men. Similar to this, households have a larger tendency to select males as the primary and steady beneficiaries of education when income inequality is on the rise, and girls may be less possible to be supported based on the investment risk of returns from higher education and projected future incomes. As a result, women are more susceptible than men to the effects of changes in the macro social environment.

Regarding cohort differences, the dynamics of structural change and social choice serve as important driving forces, which call for a sizable proportion of the young workforce, resulting in a quick rise in educational attainment in the young cohort. Also, a much bigger role of educational subsidies and welfare is observed in assisting the decrease of economic pressure and access to higher education for the young cohort as a result of broad educational expansion policies around the world. So educational mobility is more strongly moderated by economic development in the young cohort than that in the old cohort. As for the mobility-prohibiting effects of income inequality, we contend that for older cohorts, rising income inequality will make offspring more dependent on parental educational attainment, whereas, for younger cohorts, the abundance of educational institutions and educational options may lengthen the offspring’s years of schooling and weaken the relationship between them and their parental educational attainment. We then propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: The influences of economic growth, public educational expenditures, and income inequality on IEM are stronger for women than men.

Hypothesis 3: The mobility-promoting effects of economic growth and public educational expenditures on IEM are stronger for the recent cohort, and the mobility-prohibiting effects of inequality on IEM are stronger for the older cohort.

Data and variables

Data

This study applied universally represented data from the joint EVS and WVS. EVS and WVS are two large-scale and cross-sectional survey research programs aiming to investigate sociological questions. The surveys contain extensive replicated questions of educational attainment and demographic characteristics since wave one in 1981 and were conducted several waves based on multi-stage territorial stratified selection. We used the joint survey (EVS/WVS, 2021) with 81 countries/territories and 135,000 cases over other world datasets for two reasons: firstly, the data collects abundant representative data with individual and parental education in different regions, and secondly, it can be compared with other empirical findings. We selected countries based on two criteria: (1) samples are nationally representative, and (2) macroscopic indexes of GDP per capita, inequality ratio, and public expenditure on education (percent of GDP) are valid for a country.

We also extracted data from the United Nations Statistics (UN Data 2021), the World Income Inequality Database (WIID, 2021), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Statistic Database (UN Data 2021) to formulate macro variables.

This study focuses on individuals who have finished their schooling at the survey time and are between the ages of 25 and 65. The final sample is 64514 nested among 49 countriesFootnote 1, with New Zealand having the smallest sample with 576 observations and Canada having the largest sample with 2930 observations.

Measures

Individual-level variables

Respondent’s education. We recorded the highest educational level of respondents and their parents in the Joint EVS/WVS referencing from the International Standard Classification for Education system (ISCED-2011). No education, primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education, post-secondary non-tertiary education, short-cycle tertiary education, Bachelor or equivalent, Master or equivalent, and Doctoral or equivalent are all represented by numbers in the nationalized ISCED-2011 classification scheme. We converted ISCED-2011, a categorical variable, to the equivalent years, an interval variable, as required by the analytical strategy of this work.Footnote 2

Parental education. The information about the highest educational level that mothers and fathers have attained was retrospective records provided by the respondents. We transcribed these records the same as the respondents themselves and then took the maximum value. The underlying assumption is that the maximum years of mothers’ and fathers’ schooling represents the highest level of parental educational resources and is frequently used as a benchmark for a realistic approach to child-rearing.

Gender. We coded female participants as the reference group.

Cohort. We divided the sample into different cohorts based on birth years: 1950s and earlier, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Individual-level control variables. Other demographic variables are coded to reduce the omitted variables bias in models. (1) Age. (2) Father’s Job. Influenced by the study norms of the status acquisition model (Blau and Duncan, 1967), the respondent’s father’s job is coded as an elite, a nonmanual worker, or a manual worker according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations in the database, with the elite as the reference group. (3) Immigrant status is coded as a binary variable indicating whether the respondent is born in the country or is an immigrant. (4) Religious belief is also coded as a binary variable, indicating if the respondent has a religious belief. (5) Household income is measured based on the respondent’s subjective perception of their household income level relative to others in the country, with higher values indicating better income status.

National-level variables

The study needs to operationalize the broad topics into observational pieces and choose several measurements as representatives of macro influences. The primary challenge at the societal level is properly aligning macro-level information with individuals. There have been three types of measurements developed according to the recording time of macro-level variables: (1) some studies use macro-level data from two decades before the social surveys (Treiman and Yip, 1989; Yaish and Andersen, 2012); (2) some studies select specific years that can reflect their study objectives (Gugushvili, 2017); and (3) some studies use contemporaneous measures (Hertel and Groh-Samberg, 2019). It is claimed that the stated results and various assessments are substantially similar because the inequality and economic development ranking have largely remained constant over the last decades (Hertel and Groh-Samberg, 2019; Yaish and Andersen, 2012). We choose the third way, that is applying the contemporaneous national-level data to match the time when EVS/WVS surveys were administered in the main part of our analysis.

Economic development. The data on GDP per capita was sourced from the National Accounts Statistics: Analysis of Main Aggregates database (United Nations Statistics Division, 2021) in US dollars. We calculated the logarithms of GDP per capita to adjust the range of values.

Public expenditure on education. The data was sourced from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021), showing the share of public expenditure on education divided by GDP.

Income inequality. We used the income ratio of the top 20% to the bottom 20% to represent the relative advantages of the highest-income group over the lowest-income group. It reflected the degree of income inequality in a country significantly determined by the status of the income gap between the highest and lowest income group. The indicator was sourced from the WIID 2021 with a higher value standing for a higher income inequality.

See Table 1 for the descriptive details of the variables. Also, table A1 in the Appendix exhibits the abbreviations, number of cases, fieldwork period, and the mean of key variables of each country included in the analysis.

Analytical strategy

The common methodological approaches applied in the field are the mobility matrix and regression methods. The former is first proposed by Driver (1962) as a diagonal mobility index without controlling other factors (Erikson and Goldthorpe 2002), and the latter is more rigorous in considering multiple determinants (Solon, 1999; Gong, Leigh and Meng, 2012). The coefficients of parental education in regression models denote the degree of intergenerational persistence of education, which is the inverse of IEM. This paper uses the latter methodology to estimate the IEM coefficient in Stata 17.0.

Regarding the data structure, individual-level data are nested within macro-level structures, making the independence assumption of the Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis untenable. Regarding the real-world contexts, individuals’ educational attainment is heavily influenced by the sociopolitical, cultural-historical, and economic environments of their countries. In light of this, we use multilevel linear models (MLM) to examine the differential effects of national macro variables on groups with varied demographic characteristics and family backgrounds. More rigorously, the scope of this study is to describe the associations under control.

Random-coefficient regression models are set up in the following forms. At the individual level, we estimated the IEM coefficient using Equation 1:

where \({y}_{{ij}}\) and \({parental\_education\_years}\) denoted the years of schooling of respondent \(i\) and his/her parents, respectively for country \(j\). \({Z}_{{ij}}\) standed for the control variables for respondent \(i\) in country \(j\), including gender, age, \({{age}}^{2}/100\), and the respondents’ father’s job. \({\varepsilon }_{{ij}}\) denoted the individual error term.

We also introduced contextual variables of economic development, public educational investment, and income inequality at the macro level using Equation 2:

\(\begin{array}{ll}{\beta}_{0j}={\gamma}_{00}+{\gamma }_{01}{\rm{In}}({economic\_}{{deveolpment}}_{j})+\,{\gamma }_{02}{public\_education\_}{{investment}}_{j}\\\qquad+{\gamma }_{03}{social\_}{{inequality}}_{j}+\,{\mu }_{0j}\\{\beta }_{1j}={\gamma }_{10}+{\gamma }_{11}{\rm{In}}({economic\_}{{deveolpment}}_{j})+\,{\gamma }_{12}{public\_education\_}{{investment}}_{j}\\\qquad+\,{\gamma }_{13}{social\_}{{inequality}}_{j}+\,{\mu }_{1j}\\{\beta }_{z}={\gamma }_{z}\end{array}\)

The interactions of contextual factors and independent variables were added to the models in order.

Results

Descriptive results

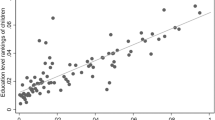

We show the distribution of the IEM coefficients and macro factors as for the descriptive results (see Fig. 1). The bar chart presents the marginal estimated coefficients of IEM from a country-fixed model in order from the lowest to the highest. A preliminary analysis suggests that higher IEM coefficients are associated with lower levels of per capita GDP, lower levels of educational expenditures, and higher inequality ratios.

We also created matrix plots to illustrate the pairwise correlations between the main variables (see Appendix Figure A1).

The intrinsic connection between contextual factors’ effects on intergenerational educational mobility

The multilevel effects on personal education

Before MLM, we applied a null model to examine the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for respondents’ years of schooling, which calculated the ratio of the between-country variance to the total variance. The ICC indicated that 19.9% of the variation in personal educational attainment lies between countries, which revealed the necessity of MLM. See Table 2 for the results of MLM.

Model 1-1 examined the random effects of the relationship between individual factors and respondents’ educational years. Controlling for other factors, parental educational years had a distinct impact on respondents’ educational years for one unit increase in parental educational years, respondents were expected to increase by 0.263 units in education, which was the mean value of IEM in all countries. Males’ educational years were statistically higher than females’ (0.068). The estimation of age denoted a declining influence on education for people usually obtain the highest education in their twenties. A higher value of household income and immigrant status were associated with higher education attainment. Compared with fathers’ being management and technical elites, a statistically negative effect was found between fathers’ having routine nonmanual jobs or manual jobs and children’s education (-0.125 and -0.740).

Model 1-2 added macro-level variables. Controlling for other variables, the log of GDP per capita was statistically positively associated with personal educational years and the inequality ratio was statistically negatively linked to it. Models 1-1 and 1-2 indicated that from the macro level, increasing economic development, growing public education support, and decreasing income inequality were associated with increased personal educational attainment.

Models 1-3, 1-4, and 1-5 added cross-level interaction terms between parental educational years and log of GDP per capita, inequality ratio, and public spending on education separately, whose coefficients showed the moderating effects of macro factors on respondents’ education. The cross-level interaction for a log of GDP per capita was significantly negative, suggesting that respondents in a country with higher GDP per capita were facing statistically less influence of parental education (−0.034). It implied that economic development could weaken the effects from the parental generation to offspring, showing mobility-promoting effects. The interaction term of public spending on education and parental education revealed similar implications (-0.032). As opposed to the mobility-promoting effect, the interaction of inequality ratio and parental educational years had a statistically significant coefficient (0.010), suggesting that a country with a higher inequality ratio was facing a stronger relationship between parents and children’s education. The three models supported the conventional models of contextual factors’ influence on IEM.

Model 1-6 was a full model. Controlling for other variables, the moderating effect of GDP per capita was not statistically significant, yet the inequality ratio and public spending on education had sustained significant moderating effects (0.008 and −0.026). After examining the cross-level interaction effects of macro-level and individual factors, the residual variance of parental educational years varied from 0.010 to 0.008, suggesting that the usage of macro factors did explain the variance of IEM among countries/regions. ICC varied from 0.205 to 0.258, suggesting that between-country variance help explain 20%–25% of the variation in the effects of parental education. The results implied that macro-micro interactions were crucial to shaping how IEM exists nationwide.

We also provide the estimation that the standard errors are clustering at the country level in the Appendix Table A3, accounting for potential within-country correlations that may arise due to shared living contexts among individuals from the same country. The coefficients remain largely consistent and p values reflect a more conservative estimation.

The comparison of the interaction effects

To better examine the dynamic relation of influence of macro factors, we divide countries into two groups based on the median value of the inequality ratio in samples: lower-inequality-ratio countries and higher-inequality-ratio countries. We conduct sub-sample analyses to compare the interaction effects, after centering and standardizing the macro factors (see Table 3). Fisher’s Permutation test is applied in the post-test to compare whether the differences between coefficients are statistically significant (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994).

Controlling for other factors, Models 2-1 and 2-2 illustrate that the moderating effect of the log of GDP per capita on IEM is only significant in countries with lower inequality ratios (−0.035). In higher unequal societies, the influence of GDP per capita on IEM is reduced by 40% than in lower unequal societies and the difference in coefficients is statistically significant with an empirical p value of 0.010. It means that only in roughly socially equal countries, the increasing economic development could reduce intergenerational educational solidification and bring up educational mobility opportunities. In higher-inequality-ratio countries, even though economic development may be advanced, they cannot moderate personal education for the effect of income inequality may eliminate the mobility-promoting opportunities of economic development. Models 2-3 and 2-4 testify to the moderating effect of public spending on education, which is another dimension of industrialization. Again, we find that the moderating effect of modernization is particularly social-context-dependent, and in lower-inequality countries, the rising public expenditures and support for education could statistically decrease IEM (−0.031), while the effect is not statistically significant in higher-inequality countries. The post-test difference is not statistically significant, though, showing that in lower-inequal and higher-inequal countries, the disparity of the mobility-promoting role of public support in education is less than that of GDP per capita.

To test the effects of the other side, we also divide countries into higher-GDP/lower-GDP groups (see Table 4). The moderating effect of income inequality is not statistically significant in both group. These results support Hypothesis 1a and 1b.

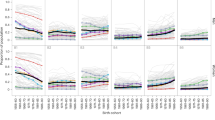

Gender and cohort differences

We conducted two sets of tests and divided the whole samples into male and female, younger cohort and older cohort. The results of the sub-sample estimation (see Table 5 and Fig. 2) show that females and males are facing differential influence from macro variables. As for females, all three factors play the corresponding significant roles as mentioned. As for males, economic development factors do not have a significant role in moderating parental educational influence. The mobility-promoting effects of GDP per capita and public educational support on IEM for women are about 1.9 times than that of men (p = 0.000). The moderating effect of inequality on women’s education is also larger than that of men and women suffer 36.4% more than men from the mobility-prohibiting effects of income inequality. Compared with men, women are more susceptible to contextual factors. The higher the level of economic development and public spending on education, the greater the reduction in the intergenerational persistence of women’s education; the higher the level of social inequity, the more the restriction on their educational opportunities.

The differences in cohort groupings are even larger than in gender grouping (see Table 6 and Fig. 3). Regarding the younger cohort, which was born after 1990, the rising GDP per capita and public spending on education are noticeably reducing the rising level of parental educational influence. The inequality ratio does not appear to be significantly correlated to their IEM. For the elder cohort, which was born before 1960, the incremental inequality ratio is statistically significant in relation to the expanding parental influence, or the declining IEM. While public investment in education is statistically significant in relation to the rising IEM, the effect of GDP per capita is not. When controlling for other factors, socioeconomic inequality restricts the IEM for the older generation more noticeably and industrialization boosts it for the younger generation. Specifically, younger cohorts enjoy two times of mobility-promoting effects brought by the increasing GDP per capita than older cohorts (p = 0.008), and older cohorts face six times of mobility-prohibiting effects of income inequality than younger generations (p = 0.000). We argue that the small difference in the impact of public spending on IEM across cohorts may be due to how the variable is measured. Public spending is typically expressed as a share of GDP. The amount of public investment in education may have increased significantly over time in a country, but its percentage of GDP shows a relatively stable state and rarely fluctuates wildly, so for different cohorts, public investment in education reduces their IEM, but the coefficients are not statistically significantly different. These findings support Hypotheses 2 and 3.

Robust test

In the baseline estimations in the previous subsections, a key concern arises regarding the unclear causal relationship between macro-level indicators (economic growth, income inequality, and public expenditure) measured after the completion of education, and individual-level IEM. Since contemporaneous macro-level variables were employed, respondents aged over 25 were analyzed using economic conditions and income distributions measured after their educational trajectories had concluded. This introduces a temporal mismatch that challenges the validity of any causal interpretation. Specifically, the macro-level conditions that should have influenced individuals’ educational decisions are, in this case, captured only retrospectively. Consequently, the observed associations between these contemporaneous macro-level indicators and educational attainment may be misleading, as they risk conflating correlation with causation.

To address this critical methodological limitation, we reconstructed the dataset by aligning each respondent with macroeconomic indicators (GDP per capita, inequality ratio, and public education expenditure) measured in the year they were likely to complete their schooling (approximately at age 25, covering the years 1977–2017). This adjustment improves the temporal validity of our analysis and allows for a more plausible investigation of the macro-level influences on IEM. However, for many countries (especially developing ones), it was difficult to obtain consistent and publicly available macro data over multiple years. This issue stems from inconsistencies in measurement standards and limited transparency in statistical reporting. As a result, the effective sample size in the robustness check was reduced by approximately two-thirds due to extensive missing data.

We employed a three-level linear model, nesting individuals within countries and time periods, to examine the interactive effects of macro-level variables in a small sample. Additionally, we conducted OLS regressions with country-clustered standard errors, incorporating country and year fixed effects to provide more robust estimates. The direction and magnitude of macro-level effects in Appendix Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, and Table A7 are largely consistent with the main findings.

Conclusion and discussion

Our research falls under the scope of fourth-generation intergenerational mobility studies (Yaish and Andersen, 2012; Ganzeboom, Treiman and Ultee, 1991) which explores whether there are systematic differences in intergenerational mobility between nations and the structural determinants for them. The most recent data and diverse nations help to promote contemporary social mobility research, particularly in the area of education. We view educational mobility from a dual perspective of the economic development theory and social inequality theory by integrating them into one framework, which might contribute to explaining the dynamic relation of the contrast forces affecting IEM.

We investigated the relationship between IEM and economic growth, public educational expenditures, and income inequality and focused our study on individuals at the ages of 25–65 across 49 countries in six continents, analyzed the heterogenous effects from contextual factors on gender and cohort, clarified the inverse influence of economic growth and unequal resources on the parent-to-children educational association, and discussed their inner association. We have reached the following three conclusions.

The first conclusion is that income inequality may surpass the facilitation of social development in improving IEM. Economic development has a substantial influence on increasing mobility in nations with low levels of inequality, but it has no significant impact in nations with high levels of inequality due to disparities in educational possibilities among classes. As income inequality increases, the upper class is able to seize opportunities for mobility and shape policy-making to monopolize educational resources for their offspring; in contrast, the lower social class may lack the motivation and ability to pursue higher education based on risk-reward predictions (Breen and Jonsson, 2005). Hence, the educational mobility chances produced by economic development are likely to remain in the privileged class, until the prevailing pattern of income inequality is changed. It differs from the arguments supporting the industrialization hypothesis (e.g., Yaish and Andersen, 2012; Lee and Lee, 2021). While we acknowledge that economic development can propel social mobility, this conclusion must be considered in light of the distribution of income inequality within society.

The second conclusion is that when the external social environment improves, women would have more mobile educational attainment, and when the social environment deteriorates, women’s educational solidification rapidly increases. By demonstrating the extent to which educational attainment by gender is moderated by macro factors, we find that boy preferences in family structures and cultural conceptions are widespread. In contexts of economic uncertainty, families may prioritize educational investment in sons over daughters, reinforcing existing gender gaps. Parental expectations and societal norms regarding gender roles can shape educational aspirations and opportunities as well. Women are the last to pursue education when economic development brings mobility-promoting effects and the first to face educational deficits when income inequality brings mobility-prohibiting effects. It highlights systematic gender disparities beyond income disparities. It also extends the conclusions of previous gender studies by not only addressing the lack of educational mobility among women (Schneebaum, Rumplmaier and Altzinger, 2016; Huo and Golley, 2022), but also further exploring how women’s educational mobility changes and becomes constrained under the influence of different macro-level factors.

The third conclusion is that the younger cohort benefits more from the expanded educational options brought on by economic expansion. It aligns with previous findings, which suggest that the younger generation, particularly those at the bottom of the distribution, exhibit higher levels of educational mobility under the radiating influence of enhanced overall social mobility (Neidhöfer, Serrano, and Gasparini, 2018). This could provide an optimistic outlook for future educational mobility levels and create the possibility of more mobility opportunities for younger generations.

The study still has several limitations. Firstly, the analysis used in the study, which is cross-sectional in nature, aims to identify correlations between cross-country differences and macro-micro interactions. We cannot establish causality because of the missing diachronic data on the changing IEM, industrialization, or income inequality. Although we conducted robustness checks using a sub sample matched by the timing of macro-level variables, we would prefer to use longitudinal data, if available, to explicitly define the time correspondence using trend analysis and lagged variables, so that we could assess the causal relationships and identify unobserved heterogeneity across countries over time. Secondly, the current study primarily explores structural factors’ impacts. Other elements, such as parenting styles (Kalil and Ryan, 2020), family wealth gaps (Pfeffer, 2018), welfare state redistribution (Beller and Hout, 2006), and inter-class inequality (Hertel and Groh-Samberg, 2019), may contribute to a deeper understanding of the resources influencing IEM and the estimation of correlations. Thirdly, we did not provide a mechanism study to explore the mediating factors that link macro determinants and individual educational mobility. Future research could enhance the path analysis to provide more in-depth theoretical justifications for the variations between countries.

Keeping these drawbacks and caveats in mind, it is important to note that the research aims to illustrate the propelling forces of two antagonistic elements influencing IEM in a wide range of countries. To marginally advance the previous research, our study sheds light on the relative importance of individual and social-contextual factors, as well as the contrasting intensity of inequality and industrialization. Based on the theoretical conjecture and empirical conceptualization, it implies a rising trend of inequality that hinders socioeconomic development’s efforts to positively promote educational mobility. The principle of equal opportunity to succeed finds advocacy from numerous policy-makers and the general public worldwide, so in this context, it is of more urgent practical significance to remove the obstruct in the socio-economic system that hinders social openness, reduce structural inequality, unblock the channels of social mobility, and promote the fairness of educational mobility opportunities. Also, we use income inequality as a proxy for social inequality, and the impacts of broader forms of inequality warrant further exploration.

Data availablity

Data used in the study can be retrieved from public database as the follows: EVS/WVS (2022). European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2022 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS). JD Systems Institute & WVSA. Dataset Version 5.0.0, https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.26

Notes

The working dataset accounts for 47.8% of the original data. The majority of the sample comprises individuals living independently (83.83%), with a smaller proportion living with their parent(s) and/or parent(s) in law (16.17%). In subgroup analysis, we found that the degrees of IEM are similar between the two groups. We plan to explore the impact of co-residency during adolescence on the degree of IEM in future research.

We coded respondents’ years of schooling based on the schooling years when they got educational certificates in most countries in Asia and the Americas. Some of the countries may differ, but this does not affect the significance of the interval variable in the regression estimates. We also analyzed the original educational levels in the robustness check to enhance the consistency of the results.

References

Ali IMA, Attiaoui I, Khalfaoui R, Tiwari AK (2022) The effect of urbanization and industrialization on Income Inequality: an analysis based on the method of moments quantile regression. Soc Indic Res 161:29–50

Aydemir AB, Yazici H (2019) Intergenerational education mobility and the level of development. Eur Econ Rev 116:160–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.04.003

Bauer PC, Riphahn RT (2009) Age at school entry and intergenerational educational mobility. Econ Lett 103(2):87–90

Becker GS, Tomes N (1979) An equilibrium theory of the distribution of income and intergenerational mobility. J Polit Econ 87:1153–1189

Beller E, Hout M (2006) Welfare states and social mobility: how educational and social policy may affect cross-national differences in the association between occupational origins and destinations. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 24(4):353–365

Blau P, Duncan OD (1967) The American occupational structure. John Wiley Sons, NY, pp 74–80

Breen R, Jonsson JO (2005) Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Ann Rev Sociol 31:223–243

Corak M (2013) Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. J Econ. Perspect 27(3):79–102

Davis K, Moore WE (1945) Some principles of stratification. Am Sociol. Rev 10(2):242–249

Driver ED (1962) Caste and occupational structure in central India. Soc Forces 41(1):26–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/2572916

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ (1994) An introduction to the bootstrap, 1st edn. Chapman and Hall/CRC, New York

Erikson R, Goldthorpe JH (1992) The constant flux: a study of class mobility in industrial societies. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

Erikson R, Goldthorpe JH (2002) Intergenerational inequality: A Sociological Perspective Journal of Economic Perspectives 16:31–44

Esping-Andersen G (2015) Welfare regimes and social stratification. J Eur Soc Policy 25(1):124–134

Esping-Andersen G, Wagner S (2012) Asymmetries in the opportunity structure: intergenerational mobility trends in Europe. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 30(4):473–487

EVS/WVS (2021). European values study and world values survey: joint EVS/WVS 2017–2021 dataset (Joint EVS/WVS). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA7505. Dataset Version 2.0.0,

Ganzeboom HB, Treiman DJ, Ultee WC (1991) Comparative intergenerational stratification research: three generations and beyond. Annu Rev Sociol 17:277–302

Gerber TP, Hout M (2004) Tightening up: declining class mobility during Russia’s market transition. Am Sociol Rev 69(5):677–703

Goldthorpe JH (2010) Analysing social inequality: a critique of two recent contributions from economics and epidemiology. Eur Sociol Rev 26(6):731–744

Gugushvili A (2017) Political democracy, economic liberalization, and macro-sociological models of intergenerational mobility. Soc Sci Res 66:58–81

Guo Y, Song Y, Chen Q (2019) Impacts of education policies on intergenerational education mobility in China. China Econ Rev 55:124–142

Gong H, Leigh A, Meng X (2012) Intergenerational income mobility in Urban China. Rev Income Wealth 58(3):481–503

Hertel FR, Groh-Samberg O (2019) The relation between inequality and intergenerational class mobility in 39 countries. Am Sociol Rev 84(6):1099–1133

Hertz T, Jayasundera T, Piraino P, Selcuk S, Smith N, Verashchagina A (2008) The Inheritance of Educational Inequality: International Comparisons and Fifty-Year Trends. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 7(2):1–48

Huo Y, Golley J (2022) Intergenerational education transmission in china: the gender dimension. China Econ Rev 71:101710

Jackson MI, Schneider D (2022) Public investments and class gaps in parents’ developmental expenditures. Am Sociol Rev 87.1:105–142

Jerrim J, Macmillan L (2015) Income inequality, intergenerational mobility, and the great gatsby curve: Is education the key? Soc Forces 94(2):505–533

Kalil A, Ryan R (2020) Parenting practices and socioeconomic gaps in childhood outcomes. Future Child 30(1):29–54

Kishwar S, Alam K (2021) Educational mobility across generations of formally and informally employed: evidence from Pakistan. Int J Educ Dev 87:102505

Krueger A (2012) The Rise and Consequences of Inequality. Presentation made at the Center for American Progress, Washington, DC

Kuznets S (1955) International Differences in Capital Formation and Financing. Capital Formation and Economic Growth. Princeton University Press

Lee H, Lee JW (2021) Patterns and determinants of intergenerational educational mobility: evidence across countries. Pac Econ Rev 26(1):70–90

Lillard LA, Willis RJ (1994) Intergenerational educational mobility: effects of family and state in Malaysia. J Hum Resour 29(4):1126–1166

Lipset SM, Zetterberg HL (1959) Social Mobility in Industrial Societies. Berkeley: University of California Press

Meemon N, Zhang NJ, Wan TT, Paek SC (2022) Intergenerational mobility of education in Thailand: effects of parents’ socioeconomic status on children’s opportunity in higher education. Asia-Pac Soc Sci Rev 22(1):158–173

Moen P, Erickson MA, Dempster-McClain D (1997) Their Mother’s Daughters? The Intergenerational Transmission of Gender Attitudes in a World of Changing Roles. Journal of Marriage and Family 59(2):281–293

Naguib C (2017) The relationship between inequality and growth: evidence from new data. Swiss J Econ Stat 153(3):183–225

Neidhöfer G, Serrano J, Gasparini L (2018) Educational inequality and intergenerational mobility in Latin America: a new database. J Dev Econ 134:329–349

Pfeffer FT (2018) Growing wealth gaps in education. Demography 55(3):1033–1068

Raftery AE, Hout M (1993) Maximally maintained inequality: expansion, reform, and opportunity in irish education, 1921–75. Sociol Educ 66(1):41–62

Raudenbush SW, Eschmann RD (2015) Does schooling increase or reduce social inequality? Annu Rev Sociol 41(1):443–470

Roy P, Basu R, Roy SA (2022) Socio-economic perspective of intergenerational educational mobility: experience in West Bengal. J Quant Econ 20:903–929

Schneebaum A, Rumplmaier B, Altzinger W (2016) Gender and migration background in intergenerational educational mobility. Educ Econ 24(3):239–260

Solon G (1999) Intergenerational mobility in the labor market. Handb Labor Econ 3(A):1761–1800

Treiman DJ, Yip K-B (eds) (1989) Educational and occupational attainment in 21 countries. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA

UNU-WIDER, World Income Inequality Database (WIID) Companion dataset (WIID-country and/or WIID-global). Version 31 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/WIIDcomp-310521

UN Data (2021). United Nations Statistics Division, New York, National Accounts Statistics: Analysis of Main Aggregates (AMA) database. Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama/

United Nations Statistics Division National Accounts Statistics: Analysis of Main Aggregates (AMA) database, last accessed June 2021

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Montreal, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) statistics database, last accessed June 2021. Retrieved from https://databrowser.uis.unesco.org/browser/EDUCATION/UISSDG4Monitoring

Wang J, Wu Y (2023) Income inequality, cultural capital, and high school students’ academic achievement in OECD countries: a moderated mediation analysis. Br J Sociol 74(2):148–172. Mar

Yaish M, Andersen R (2012) Social mobility in 20 modern societies: the role of economic and political context. Soc Sci Res 41(3):527–538

Yaish M, Shiffer-Sebba D, Gabay-Egozi L, Park H (2021) Intergenerational educational mobility and life-course income trajectories in the United States. Soc Forces 100(2):765–793

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing -original draft; Writing - review & editing QZ: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Zhang, Q. Economic development benefits or social inequality hinders? Intergenerational educational mobility in 49 countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05687-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05687-x