Abstract

The rapid development of virtual social networks has transformed word-of-mouth (WOM) communication, breaking traditional spatial and temporal constraints and profoundly influencing consumer decision-making and corporate image-building. Internet word-of-mouth (IWOM) in tourist attractions is a mediated context formed through the interaction between tourist groups and the environmental settings of tourist destinations, significantly influenced by the interplay of media and physical spatial environments of the attractions. This study constructs a multidisciplinary framework to analyze the mechanisms driving IWOM, employing machine learning to measure the impact of environmental factors. Additionally, it explores the characteristics of IWOM from macro and micro perspectives. The key findings are as follows: (a) Tourists exhibit high satisfaction and positive experiential perceptions toward the scenery of attractions, with tourist attractions, management services, and transportation facilities being the core elements of concern. The spatial distribution of IWOM in tourist attractions is dependent on the destination, displaying a pattern of “large agglomeration with small dispersion” within regions. (b) The distribution of IWOM in natural ecology, historical and cultural, and modern amusement tourist attractions exhibits a multi-center pattern, while industrially integrated tourist attractions demonstrate a single-center distribution. Scenery, history, projects, and porcelain are the core high-frequency terms in the IWOM of various typical tourist attractions. (c) Scenery has emerged as a decisive factor in the IWOM of tourist attractions, particularly significant in industrially integrated attractions. Government attention and internet popularity are identified as the primary media environmental factors influencing IWOM. The impact of various factors on IWOM shows significant spatial heterogeneity. Systematically identifying the characteristics and mechanisms influencing IWOM in tourist attractions can provide effective theoretical support for the management and sustainable development of tourist destinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The proliferation of Internet technologies has fundamentally transformed information dissemination patterns. Internet-based word-of-mouth (WOM) communication, characterized by its spatiotemporal transcendence, has become a pivotal force in reshaping modern consumption behavior and revolutionizing marketing management mechanisms in both consumer and industrial markets (Liu et al., 2024). Within tourism research, Internet word-of-mouth (IWOM) constitutes informal yet impactful exchanges through digital platforms, wherein tourists and opinion leaders collaboratively generate and disseminate multifaceted evaluations encompassing destination-specific products, service quality, experiential features, and post-visit perceptions. Functioning as an authentic repository of tourist experiences, IWOM plays a determinant role throughout the consumption decision-making cycle. Through strategic information acquisition, cognitive evaluation, and participatory content creation regarding destinations, tourists effectively address heterogeneous information requirements while simultaneously reducing risk perceptions and augmenting experiential value (Prendergast et al., 2010; King et al., 2014). Tourism IWOM further serves as a critical manifestation of destination image formation, with its diversified content constituting an indispensable basis for destination governance systems and precision marketing strategies. In the context of China’s tourism sector transitioning towards quality-oriented development, the multiplier effects of IWOM have witnessed substantial intensification. This enhanced influence on destination evolution and brand system optimization has precipitated three interconnected transformations: the rationalization of tourism resource allocation, the spatial reconfiguration of destination landscapes, and the synergistic integration of regional industrial chains. These structural shifts collectively drive the optimization of regional sustainable development trajectories.

Literature review

Since the 1990s, academia has focused on defining, measuring, and exploring the influencing factors of IWOM across various consumer products. IWOM originates from the concept of WOM in communication studies (Liu et al., 2024). It emerged in the Internet era as interpersonal communication gradually shifted to online platforms. Consumers, after making purchases, share their actual experiences and disseminate product-related information through informal exchanges on virtual communities such as microblogs, social networks, and consumer review platforms. (King et al., 2014). IWOM provides functions such as information accumulation, querying, consultation, and organization (King et al., 2014). These informal exchanges generate IWOM data, which has become a vital foundation for quantitatively measuring satisfaction with products and services, offering direct insights for consumer decision-making and the formulation of corporate marketing strategies. Scholars studying IWOM measurement have generally focused on single dimensions, including IWOM volume, quality, and valence. IWOM volume reflects the extent of WOM communication among potential consumers (Liu, 2006), with higher volumes corresponding to greater perceived usefulness (Ismagilova et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2006). IWOM quality indicates consumers’ perception and reception of products and services, with high-quality information better reflecting actual product attributes and being more readily accepted by recipients (Lee and Youn, 2009). IWOM valence evaluates consumer satisfaction with consumption experiences based on keywords in micro-level review texts (Duan et al., 2008; Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2006), providing insights into areas for corporate image improvement and shifts in marketing strategies (Loureiro and Kastenholz, 2011; Jasin, 2022). In terms of influencing factors, IWOM represents the interaction between transmitters and receivers during information transmission, with stronger relationships increasing the likelihood of influence (Forman et al., 2008; Akdim, 2021; Kim and Lee, 2017). Additionally, IWOM is affected by the transmitter’s occupation, gender, purchasing preferences, and social network status (Wang and Chen, 2019), while the receiver’s expertise, product characteristics, and network involvement result in varied responses to the same IWOM (Forman et al., 2008; Akdim, 2021; Kim and Lee, 2017). Tourist attraction IWOM, as an important component of IWOM, is more susceptible to the influence of uncertainty and risk.Academic studies on tourism IWOM have primarily focused on its relationship with service quality, tourist decision-making, and IWOM communication processes (Chen, 2024; Medeková and Pompurová, 2024). Scholars generally regard tourism IWOM as a critical indicator of destination service quality and a direct reflection of visitor experiences (Arismayanti et al., 2024; Sukaris et al., 2020). Its quality and credibility significantly affect tourists’ decision-making processes (Wang, 2016). Tourism IWOM is notably influenced by the expertise of both publishers and receivers, the closeness of their relationship, visual cues, and the inherent bias of IWOM (Luo and Zhong, 2015).

While extensive research has been conducted on general IWOM and tourism-specific IWOM, most studies have relied on theoretical frameworks from communication studies, information behavior, and psychology to examine IWOM measurement and its impacts. These studies primarily adopt qualitative analyses, with limited application of mathematical and spatial models for quantitative research, which hampers a comprehensive understanding of the macro- and micro-level features of tourism IWOM. Against the backdrop of transformative changes in research paradigms, knowledge production has increasingly shifted from isolated approaches to integrated frameworks, with interdisciplinary interactions, penetration, and fusion becoming dominant trends in academia. This highlights the relatively narrow and outdated scope of tourism IWOM research and underscores the need to transcend traditional research domains.

The advancement of geographic information technologies has enhanced the role of spatial models across various fields. These models provide an intuitive understanding and analysis of spatial relationships, patterns, and trends, improving data readability and comprehension while supporting decision-making. Tourism IWOM is widely recognized as reflecting destination image, influencing tourist behavior, and indirectly altering the effectiveness of tourism activities. However, the status of tourism destinations and their associated IWOM is significantly influenced by regional human-environment relationships, with natural and cultural factors playing essential roles in shaping destination image. Strengthening the spatial structure of tourism IWOM enriches the research perspective on IWOM and provides strong support for regional tourism resource integration and industrial competitiveness. Based on this understanding, this study aimed to comprehensively characterize tourism IWOM through macro-level spatial structures and micro-level review valences. Using the theory of human-environment relationships as a foundation, the study integrated interdisciplinary theoretical approaches to construct a framework for exploring the influencing mechanisms of tourism IWOM. Machine learning methods were employed for quantitative analysis, extending the research scope of tourism IWOM and promoting sustainable regional development.

Building on the previous analysis, the specific objectives of this study were as follows: (1) Based on Ctrip’s tourist attraction rating data and review texts from typical tourist attractions, this study analyzes the spatial structural characteristics and valence conditions across different dimensions and types. (2) Integrating multidisciplinary theories to develop a framework for understanding the influencing mechanisms of tourist attraction IWOM, and applying the XGBoost-SHAP model to quantitatively identify the factors that influenced IWOM. (3) Proposing optimization strategies aimed at enhancing IWOM and promoting the sustainable development of tourist attractions, considering both a regional perspective and the viewpoint of individual tourist attractions.

Research design

This study focused on the theme of tourist attraction IWOM, with the primary objective of describing its key features and exploring the factors influencing it. Specifically, the characteristics of the IWOM of tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province were examined, along with the factors that influenced it (Fig. 1). In the feature analysis, four key dimensions—comprehensive, scenery, interesting, and cost performance—were characterized by analyzing score values and high-frequency words (Step 1). Furthermore, based on spatial structure and high-frequency word features, the macro and micro characteristics of IWOM across four major types of tourist attractions—natural ecology, historical and cultural, modern amusement, and industrial integration—were analyzed (Step 2). It should be noted that steps 1 and 2 successfully integrated both macro and micro analyses and combined quantitative and qualitative approaches to characterize the IWOM of tourist attractions. For the factor analysis, multidisciplinary theories were integrated to analyze the interactions within the “ tourist attraction environment - tourist - IWOM “ framework, leading to the construction of a mechanism for the influence of IWOM in tourist attractions (Step 3). Additionally, machine learning methods were employed to quantitatively identify the factors affecting IWOM across the entire region, specific tourist attractions, and various types of tourist attractions, enabling a comprehensive analysis of IWOM at the scale of overall, type and individual (Step 4).

The research architecture follows a systematic progression: The introductory section systematically establishes the theoretical foundation by delineating the academic significance and contextual background of IWOM investigations in tourism destinations, synthesizing extant scholarly work while articulating the research objectives and theoretical contributions. Subsequent methodological components maintain rigorous separation: The Research Design segment clarifies conceptual frameworks and analytical approaches, while the Materials and Methods chapter specifies the geographical parameters, data provenance, and methodological protocols. Empirical findings are methodically presented through three analytical lenses: The Results section initially reveals multidimensional evaluation patterns through integrated assessment of numerical ratings, spatial configurations, and lexical frequencies across attraction typologies. Subsequently, it develops an influence mechanism framework grounded in human-environment interaction theory, complemented by XGBoost-SHAP modeling applications that quantitatively elucidate determinant factors across macro-regional, meso-categorical, and micro-site analytical scales. The Discussion section critically evaluates methodological innovations in spatial characterization and multi-scale factor analysis, while proposing IWOM-informed management strategies for sustainable destination development in Jiangxi Province. Concluding remarks consolidate principal theoretical advancements and practical implications, maintaining thematic alignment with initial research objectives throughout the structural narrative.

Materials and methods

Study area

China possesses abundant and diversified tourism resources across multiple typological categories. To standardize destination management and elevate service quality, the China National Tourism Administration implemented the Rating Standards for A-Level Tourist Attractions, establishing a comprehensive evaluation framework encompassing resource quality, service standards, development levels, and infrastructural conditions. This hierarchical system categorizes attractions into five tiers (designated as 1 A to 5 A), where higher classifications correspond to superior integrated quality in resource endowment, service delivery, and facility provision (Qiu et al., 2021). Jiangxi Province, situated in southeastern China, exhibits distinctive tourism resource advantages characterized by its revolutionary heritage (red tourism), ecological landscapes (green tourism), and historical-cultural relics. As of March 2023, the province hosts 484 A-level tourist attractions, ranking among China’s top-tier regions in attraction quantity, with spatial distribution patterns detailed in Fig. 2. The “National County-Level Tourism Development Research Report 2024” further highlights Jiangxi’s prominent position in China’s tourism landscape: six counties are listed among the nation’s top 100 for comprehensive tourism strength (fourth-highest provincial ranking), while nine counties feature in the top 100 for tourism development potential (second-highest provincial ranking). These metrics collectively demonstrate Jiangxi’s accelerated tourism sector growth in recent years. However, persistent challenges constrain the province’s tourism development, including a relatively small industry scale compared to national benchmarks, limited brand influence and market visibility, and structural imbalances between resource abundance and economic conversion efficiency (Mao et al., 2024). These issues underscore the necessity for strategic interventions to optimize Jiangxi’s tourism development trajectory.

Data source and description

This study focuses on A-level tourist attractions as the research object. The list of attractions was obtained from the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism (http://dct.jiangxi.gov.cn/) and supplemented with data from the MAIGOO platform (https://www.maigoo.com/goomai/190683.html). As of March 2023, Jiangxi Province has a total of 484 tourist attractions.

Ctrip, one of China’s leading online travel service platforms, is widely recognized for its extensive data volume, diverse sources, timely and accurate updates, multidimensional evaluation system, and strong user interaction capabilities. These characteristics make it a highly authoritative and valuable resource for studying IWOM related to tourist attractions (Li et al. 2010; Tsung-Nien, 2020). In this study, Python was used to scrape data from the Ctrip platform (https://www.ctrip.com/) to collect overall ratings and dimension-specific scores for tourist attractions. After data cleaning, random verification, and the removal of outliers, a dataset containing IWOM scores for A-level tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province was obtained.

To further analyze the sentiment characteristics of IWOM, 5A-level tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province were selected as representative examples. Review text data was scraped from Ctrip, resulting in a collection of 14,327 reviews. After deduplication, cleaning, and general preprocessing, 13,912 valid reviews were retained.

In the analysis of factors influencing IWOM, Python was used to scrape data from WeChat Mini Programs, Weibo, and Gaode Maps, focusing on metrics such as the WeChat index, check-in counts, accommodation options, scenic environment, and cost performance. These metrics were used to determine fame level, internet popularity, hotel accommodation, scenic area scenery, and cost performance. Additionally, policy documents, regulations, and notices related to tourist attractions were collected from the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism website to construct a dataset reflecting government attention to these attractions.

Research methods

Kernel density estimation

Kernel Density Estimation is an effective technique to measure local density changes and explore spatial hotspots. It can calculate the density of point elements around each output grid to show the concentration and dispersion of the spatial distribution of tourist attractions (Wang et al., 2020). The specific formula is as outlined in Eq. (1):

In the formula, \(D({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\) is the kernel density value of IWOM of tourist attractions at the spatial position \(({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\); r is the search radius, also known as bandwidth; Is a point element whose distance from the u position \(({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\) is less than or equal to the radius r; k function represents the spatial weight function; d is the point distance between the current point element and \(({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\).

In kernel density analysis, the choice of bandwidth significantly influences the degree of smoothing in the results. However, there is currently no universal consensus on how to determine an optimal bandwidth size (Kloog et al., 2009). Some researchers argue that the bandwidth should not exceed the highest required resolution, while others suggest basing the kernel density bandwidth on the nearest neighbor distance (Kloog et al., 2009). In this study, the nearest neighbor index for tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province was measured, revealing an expected average nearest neighbor distance for IWOM of 11.2 km. Additionally, the bandwidth calculation method proposed by BAILEY and GATRELL (Bailey and Gatrell, 1995) was employed, resulting in a kernel density bandwidth of 12.8 km for IWOM in Jiangxi Province. By averaging these two results, a kernel density search radius of 12 km was established. To better illustrate the overall spatial structure of tourist attractions across the entire region, kernel density calculations were performed using bandwidths of 24 km, 36 km, 48 km, and 60 km. Among these, a bandwidth of 48 km was found to best capture the spatial distribution characteristics of IWOM for tourist attractions. Consequently, this bandwidth was used for the kernel density analysis of IWOM across various types of tourist attractions.

Text analysis

The ROST CM6 software, developed by Dr. Shenyang’s team at Wuhan University, is a large-scale, free social computing platform capable of performing text content analysis functions such as word segmentation, word frequency statistics, cluster analysis, and sentiment analysis. It provides an objective and systematic method for description and analysis (Wang, 2023). In this study, the ROST CM6 software was used to extract high-frequency words from tourist IWOM review texts, aiming to analyze tourists’ feedback on the IWOM of scenic areas.

XGBoost-SHAP model

XGBoost model

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is an ensemble learning algorithm (Chen et al. 2015). This algorithm constructs CART (Classification and Regression Trees) in a sequential manner, continuously adding new base classifiers (CART trees) to the model to optimize a newly defined objective function that fits the residuals from the previous prediction. The final prediction is obtained by summing the outputs of all the base classifiers. Assuming there are k classification decision trees, the prediction result obtained through the ensemble strategy can be expressed by Eq. (2):

In the formula, \({x}_{i}\) represents the i sample, \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) denotes the predicted value, \({f}_{k}\) is the prediction result of the k-th tree, and F represents the corresponding function space generated by all CART trees. In the XGBoost algorithm, the optimization of regression trees proceeds iteratively, starting from the first tree and sequentially progressing to the k-th tree. Based on this process, the objective function of XGBoost is expressed as shown in Eq. (3):

The first term, \(l({y}_{i},{\hat{y}}_{i})\), represents the training loss, which aims to calculate the difference between the true value \({y}_{i}\) in the dataset and the predicted value \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) generated by the model. The second term, \(\Omega ({f}_{k})\), represents the complexity of the k-th tree, serving as the regularization term in the objective function.

The training loss function is approximated by expanding it into three terms using the Taylor series, resulting in a new objective function, as shown in Eq. (4):

where \({g}_{i}\) represents the first-order derivative of the training loss \(l({y}_{i},{\hat{y}}_{i})\), \({h}_{i}\) represents the second-order derivative of \(l({y}_{i},{\hat{y}}_{i})\), and C denotes the constant term.

To evaluate the predictive performance of the model, this study employs the coefficient of determination R2 (2 Squared Correlation Coefficient), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) as evaluation metrics.

SHAP model

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a method grounded in cooperative game theory designed for interpreting machine learning models (Lundberg et al. 2020). It quantifies the relationship between individual features and model predictions by treating each feature as a “contributor” and calculating its contribution value. These contributions are then aggregated to obtain the model’s final prediction. For ensemble models, particularly in classification tasks, the model typically outputs a probability value. SHAP assigns a Shapley value to each feature, which quantitatively measures the contribution of that feature to the model’s final prediction. Let f denote the model to be interpreted, k represent the total number of features, and ϕ the Shapley value of each feature. The specific formula is as outlined in Eq. (5)

In the formula, \({f}_{n}\) represents the predicted value, \({\upphi }_{0}\) is the average predicted value of all training samples, and \({\upphi }_{i}\) denotes the Shapley value of the i-th feature. The specific formula is as outlined in Eq. (6)

In the formula, N represents the set of all features, S denotes a subset of N with a specific order, \({f}_{x}(S\cup \{i\})-{f}_{x}(S)\) represents the marginal contribution of feature i when added to subset S, and M is the total number of input features. One significant advantage of SHAP is its ability to reflect the contribution of each feature to the prediction results.

Results and analysis

Scoring characteristics of IWOM for tourist attractions

The Ctrip travel platform provides comprehensive evaluations of tourist attractions based on the services they offer. Its evaluation framework includes multiple dimensions such as scenery, entertainment value, and cost performance. Visitors can submit textual reviews based on their experiences and rate these dimensions on a scale of 1 to 5. Ctrip employs a Bayesian average algorithm to allocate weights to each dimension and analyze the confidence levels of user ratings, ultimately calculating an overall score. Additionally, the platform applies smoothing techniques to the results to mitigate the impact of outliers and extreme values, providing a more objective reflection of the true quality of tourist attractions and the authentic experiences of visitors.

The average IWOM score for A-level tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province is 4.25, with 62.60% of attractions scoring above 4.00. This indicates that tourists generally report positive experiences and high satisfaction levels. In terms of specific dimensions, the average scores for scenery, interesting, and cost performance are 4.35, 4.19, and 4.20, respectively. Significant differences are observed in the dimension scores across different types of tourist attractions, with the scenery dimension consistently achieving higher ratings across all categories. Figure 3 illustrates that natural ecology attractions receive mid-level IWOM scores across all dimensions, without exhibiting any particularly outstanding features. Among these, the scenery dimension achieves the highest average score of 4.126. Historical and cultural attractions, by comparison, rank second in the scenery dimension among all types of tourist attractions but achieve the highest scores in overall ratings, interestingness, and cost performance. Modern amusement attractions outperform others in the scenery dimension, with a peak score of 4.705, but perform less competitively in other IWOM dimensions. Finally, industrial integration attractions score lower across all dimensions relative to other types of tourist attractions, with their highest score also found in the scenery dimension.

Analysis of high-frequency words of IWOM for tourist attractions

This study imported review text data from representative tourist attractions (5A-level) into the ROST CM6 software. Using “word frequency analysis,” a word frequency table was generated. After removing irrelevant or meaningless words, a word cloud was created using visualization software, as shown in Fig. 4. High-frequency words in the total dimension primarily reflect the attractions’ appeal, including terms such as scenery, landscape, waterfall, sunrise, history, architecture, culture, and environment. The management and service quality of the attractions significantly influence their IWOM, resulting in high-frequency words such as tour guide, hotel, driver, staff, and ticket. Additionally, transportation-related terms such as cable car, plank road, sightseeing bus, electric cart, and boat were frequently mentioned. Moreover, high-frequency verbs primarily reflect tourists’ behavioral motivations, such as playing, sightseeing, queuing, and photographing. Finally, high-frequency adjectives in the reviews capture tourists’ subjective experiences during their visits, including terms such as fun, exciting, satisfying, disappointing, and mediocre. Overall, tourists’ online reviews mainly focus on the six key elements of travel: “food, accommodation, transportation, sightseeing, shopping, and entertainment.”

The extraction and visualization of high-frequency words across different dimensions of IWOM text provide scientific insights for brand building and image improvement of tourist attractions. In the “scenery” dimension, high-frequency words in IWOM text primarily reflect the overall evaluation of scenic resources. The most frequently mentioned terms include scenery and landscape. Within scenic resources, tourists focus mainly on natural features such as waterfalls, sunrises, seas of clouds, fresh air, mist, forests, and ancient trees. These features are often described using adjectives such as beautiful, elegant, spectacular, comfortable, and exquisite.

In the “interesting” dimension, high-frequency words in IWOM text mainly highlight recreational activities, including rafting, performances, hot springs, boat tours, movies, evening parties, and exhibitions. Tourists’ evaluations of these activities frequently include terms such as fun, interesting, exciting, unique, and lively. Moreover, tourist comments emphasize aspects such as the attraction’s planning, playability, traditional culture, man-made attractions, and whether it is considered a “social media hotspot,” all of which are closely associated with the interesting dimension of IWOM. In the “cost performance” dimension, high-frequency nouns in IWOM text primarily relate to expenditures, including hotels, ticket prices, accommodation, souvenirs, shops, combo tickets, and coupons. Tourists’ evaluations in this dimension frequently include terms such as discounted, commercialized, expensive, and cost-saving.

The spatial pattern of IWOM for tourist attractions

Spatial distribution pattern of total IWOM for tourist attractions

To further illustrate the spatial distribution of IWOM for tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province, kernel density analysis was conducted using IWOM scores as the input data, with bandwidths set at 12 km and 48 km, respectively. The density values were classified into nine categories using the Natural Breaks (Jenks) method (Fig. 5).

The kernel density map with a 12 km bandwidth clearly revealed the clustering patterns of IWOM for tourist attractions. Significant spatial disparities were observed, with high-density regions forming a distinct “three-pole, multi-center” distribution pattern. The highest-density centers emerged in the central-western part of Nanchang, supported by attractions such as Tengwang Pavilion; the central part of Jingdezhen, centered around the Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln and Folk Customs Museum; and the northeastern part of Jiujiang, driven by Mount Lushan. These high-density clusters not only reflected the spatial agglomeration of tourist attractions but also emphasized the prominence of well-established tourism brands within these clusters. At the secondary level, sub-clusters were identified in Shangrao, Fuzhou, Pingxiang, Yichun, and Ji’an, with Fuzhou hosting the largest number of sub-centers, totaling five. However, the IWOM performance of tourist attractions in these areas still requires improvement, and further efforts are needed to enhance their image and reputation.

The kernel density map with a 48 km bandwidth provided a comprehensive depiction of the overall spatial structure of IWOM for tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province. High-density IWOM areas were primarily concentrated in the central and northern regions of Jiangxi, forming a contiguous development pattern. Spatially, this distribution exhibited a “one-pole, multi-core” structure characterized by “large clusters and small dispersions,” while the southern region of Jiangxi remained sparsely distributed. The absolute highest-density center for IWOM was located in the central-western part of Nanchang, positioning the provincial capital as the core area for IWOM in Jiangxi Province. Secondary core areas were observed in the northeastern part of Jiujiang and the central part of Jingdezhen. Together, these core and secondary core areas formed a spatial pattern resembling a “tripod”, with Nanchang, Jiujiang, and Jingdezhen serving as the focal points. This configuration highlights these regions as critical areas for unlocking the potential of Jiangxi’s tourism economy and driving its core economic growth. In addition, high-density IWOM centers were identified across all prefecture-level cities, with each center exhibiting a concentric ring pattern of density values that gradually declined outward. This hierarchical distribution underscores the importance of these core areas in shaping the province’s tourism landscape and further emphasizes the need to strengthen them to enhance the overall competitiveness of Jiangxi’s tourism sector.

Analysis of IWOM for different types of tourist attractions

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial distribution patterns of IWOM for different types of tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province under a 48 km bandwidth. For natural ecological attractions, the IWOM exhibited a multi-core pattern in the central and northern regions of Jiangxi, with continuous east-west expansion. In contrast, the southern region displayed a relatively scattered and independent point-like distribution. High-density IWOM clusters were concentrated in northern Jiangxi, supported by the Lushan Mountain Range, and in western Jiangxi, along the Luoxiao Mountain Range. Secondary core areas were primarily located in the central-northern and northeastern regions of Jiangxi. In the central region, IWOM density clusters were observed along the Gan River, while in the southern region, independent IWOM clusters emerged around the Dayuling and Jiulian Mountain Ranges. For historical and cultural attractions, high-density IWOM centers were identified in northeastern Jiangxi, influenced by its ceramic culture, and in central Jiangxi, shaped by its Luling culture. These clusters collectively formed a “diamond-shaped” spatial pattern, with relatively independent scattered aggregation centers surrounding the periphery. For modern entertainment attractions, high-density IWOM centers were concentrated in Jiujiang, Nanchang, and Fuzhou, while secondary core areas were formed at the Pingxiang-Yichun border and in Shangrao. These regions displayed significant clustering. In contrast, relatively low-density scattered regions were observed in northeastern, central, and southern Jiangxi. For industrially integrated attractions, the spatial distribution exhibited a “small cluster, large dispersion” pattern. High-density IWOM centers were observed in Nanchang, the provincial capital, with a secondary core area identified in Jingdezhen. Smaller clustered regions featured IWOM centers distributed in Jiujiang, Nanchang, and Fuzhou, extending southeastward to Shangrao. Independent group-like clusters were observed in areas such as Jiujiang, Pingxiang-Yichun, Ji’an, and Ganzhou, forming a dispersed spatial structure. Overall, while the spatial distribution of IWOM across different types of tourist attractions exhibited distinct regional characteristics, high-density areas were predominantly concentrated in central and northern Jiangxi. These findings highlight the significant clustering of IWOM in these regions and underscore their strategic importance as key focal points for the development and promotion of tourism in Jiangxi Province.

To gain deeper insights into the primary areas of tourist focus across different types of attractions, a representative site was selected from each category, and high-frequency words were extracted from their IWOM review texts. Figure 7 highlights that Lushan, as a representative natural ecology attraction in Jiangxi Province, features high-frequency words related to the environment, such as scenery, sunrise, sea of clouds, air, history, and culture. In terms of tourism services and infrastructure, reviews emphasize cable cars, ropeways, restrooms, sightseeing buses, coaches, and restaurants. Additionally, aspects related to management and operations, such as queuing, order, and scheduling, as well as tourism expenses, including ticket prices, commodity prices, and cost performance, also receive significant attention. Tourists primarily provide positive feedback on their experiences, using terms such as fun, comfortable, interesting, and safe.

Tengwang Pavilion was selected as a representative historical and cultural attraction. High-frequency words in its IWOM review texts primarily focus on elements of the humanistic environment, including history, culture, knowledge, and architecture. Tourists frequently highlight activities such as performances, light shows, night tours, boat rides, exhibitions, and social media check-ins. Regarding infrastructure and services, key areas of focus include elevators, parking, sanitation facilities, guided tours, and directional signage. Tourism-related expenses, such as souvenirs, cultural and creative products, and ticket prices, are also frequently mentioned. Tourist feedback on Tengwang Pavilion is overwhelmingly positive, often described as spectacular, human-centered, commercialized, and enjoyable.

Sunac Land, representing modern amusement attractions, demonstrates that amusement activities are the primary focus of tourist reviews, with high-frequency words related to movies, performances, and programs. Additionally, high-frequency words highlight concerns about cost performance, ticket prices, and discounts, as well as basic facilities such as ticket machines, parking, restrooms, and storage. Feedback for modern amusement attractions is predominantly positive, with descriptions such as exciting, safe, and relaxing being commonly used.

The Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln Folk Customs Museum, a representative industrial integration attraction, features high-frequency words in its IWOM review texts related to the humanistic environment, including ceramics, history, culture, knowledge, and heritage sites. Tourists place great importance on activities such as performances, handicrafts, and manufacturing experiences, as well as the services provided by staff, such as explanations and interactive experiences. Tourism expenses, including discounts, costs, and ticket prices, are also prominent in the reviews. Feedback on industrial integration attractions highlights their uniqueness, meaningfulness, and playability.

In summary, tourist feedback across all types of attractions consistently underscores the importance of the tourism environment, consumption, infrastructure, and services. However, notable differences exist in the areas of focus among different attraction types. Natural environmental factors are a primary concern for natural ecology attractions, while humanistic environmental elements are significant in natural ecology, historical and cultural, and industrial integration attractions. In contrast, modern amusement attractions show relatively low attention to environmental factors, with the primary focus placed on amusement activities.

Factors influencing IWOM for tourist attractions

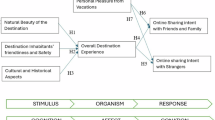

The influence mechanism of IWOM for tourist attractions

IWOM of tourist attractions refers to the process by which a group of tourists forms an overall perception of the destination’s environment, based on their sensory experiences of its external appearance. Tourist attractions integrate both the physical and media spaces of the destination, representing the product of capital production and consumption activities (Fig. 8). From the perspective of human-environment interactions, the IWOM of tourist attractions emerges as a complex media situation, shaped by the reciprocal influence between tourists and the destination environment. Tourists are the primary agents involved in both the experiential engagement with the attraction’s environment and the construction and dissemination of its IWOM. The environment of the tourist attraction exerts a permeation effect on tourists’ spatial practices, thus providing the physical space foundation for the development of the IWOM. Moreover, tourists’ direct experiences of the attraction are fed back into the IWOM through environmental perception, spatial representation, and information-social interaction. On the other hand, the IWOM of the tourist attraction impacts tourists’ behavioral decisions, further inducing either adaptation or resistance to the attraction’s environment. Overall, the collective IWOM generated by tourists offers a comprehensive and objective reflection of the spatial and environmental characteristics of the destination, thus serving as a crucial indicator of the destination’s overall reputation.

Market price, infrastructure, natural scenery, and government policy are key elements of the physical environment of tourist attractions. These environmental factors influence the formation of the IWOM (IWOM) of tourist attractions by affecting tourists’ spatial practices, environmental perceptions, and the spatial representation of their experiences. According to customer perceived value theory, the overall evaluation of a product or service is determined by weighing the perceived benefits against the costs incurred during the acquisition process. As a service-oriented activity, tourism involves tourists striving to maximize their benefits, with particular emphasis on the perceived value of the destination. When tourists capture information regarding the cost-performance ratio of a tourist attraction, this can influence their decision-making and behavioral practices, either enhancing or diminishing their perception of the attraction’s value, thereby impacting its IWOM (Zeithaml, 1988; Guttentag, 2015). Tourism activities encompass a complex system of experiences, including aspects such as dining, accommodation, transportation, sightseeing, shopping, and entertainment. The infrastructure and natural scenery of a tourist attraction serve as indicators of the attraction’s quality and level, influencing tourists’ experiences and, consequently, the IWOM of the attraction (Yang and Chen, 2007; Grosspietsch, 2006). The government intervention theory asserts that improving the market environment and regulating market factors are central to effective government involvement. Tourist attractions rely on the assistance of market intermediaries to manage their operations efficiently. In situations where the tourism service system is underdeveloped, policy support and attention become particularly crucial in optimizing the resource allocation of tourist attractions. Therefore, throughout the development process of a tourist attraction, policy support drives the growth of tourism activities, influences tourists’ perceptions and experiences of the attraction’s environment, and ultimately impacts the quality and effectiveness of the IWOM (Maškarin Ribarić and Ribarić, 2013). From the perspective of the media environment, the fame level and Internet popularity of tourist attractions, through information-social interactions, directly affect tourists’ activities and ultimately influence the IWOM of the attraction. In the context of tourist expectation theory, expectations represent customers’ predictions and opinions regarding the future performance of a product, largely shaped by advertising, business communication, WOM, and prior experiences. By enhancing tourists’ expectations of a tourist attraction, both tourist flow and satisfaction can be significantly improved. The fame level and Internet popularity of an attraction offer tourists valuable reference points to predict its future development trends. When this information enters tourists’ cognitive processes, it stimulates their evaluation, thus influencing the spatial representation and dissemination of the IWOM (Oliver, 1980).

Based on the above analysis, this study quantitatively measures the influencing factors of the IWOM for tourist attractions, selecting six specific indicators: the WeChat index (fame level), the number of hotel accommodations (hotel accommodation), scenery ratings (scenery), cost performance ratings (cost performance), the number of government-issued communications (government attention), and the number of Weibo check-ins (Internet popularity).

The influencing factors of IWOM for tourist attractions in Jiangxi province

During the construction of the model, 80% of the sample dataset was allocated as the training set, while the remaining 20% served as the test set. This partitioning ensured that the model exhibited strong generalization capabilities on independent datasets. The results showed that the training set achieved an R2 of 0.9900, RMSE of 0.0478, and MAE of 0.0303, indicating a high level of goodness-of-fit and predictive accuracy. For the test set, the R2 was 0.6516, RMSE was 2.1380, and MAE was 1.6291, demonstrating satisfactory generalization performance. With a coefficient of determination (R2) above 0.6, the validity and robustness of the model were confirmed. While the XGBoost model displayed exceptional predictive performance, its complexity as an ensemble learning algorithm often leads to it being regarded as a “black box” with limited interpretability. To address this, SHAP, grounded in the Shapley value principle from game theory, provides a powerful framework for interpreting the prediction process and evaluating the importance of features in machine learning models. SHAP values offer comprehensive global and local interpretability by fairly attributing the contribution of each variable. Through visualization, SHAP compensates for the interpretability limitations of traditional linear regression models (Ergün, 2023). For each sample, the SHAP model generates a “SHAP value,” which represents the average marginal contribution of a variable across all possible permutations.

Figure 9 presents the quantified contributions of individual features to the dependent variable based on feature importance weights. IWOM for tourist attractions is influenced by a variety of factors. Among these, scenery contributes the most significantly to IWOM, accounting for nearly 40%, making it the most decisive factor. Government attention and Internet popularity are also critical factors, contributing 20.20% and 17.58%, respectively. These findings underscore the substantial impact of government attention and Internet popularity on IWOM for tourist attractions. In contrast, factors such as fame level, hotel accommodation, and cost performance make comparatively smaller contributions to IWOM, with proportions of 9.99%, 6.44%, and 5.85%, respectively, indicating a relatively minor influence on the overall IWOM for tourist attractions.

To investigate the differences in factors influencing IWOM across four types of tourist attractions, the XGBoost-SHAP model was utilized to establish the relationship between IWOM and its influencing factors, and to calculate the contribution of each factor to IWOM, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The results demonstrate significant variations in contribution values across different attraction types. Scenery emerged as the most influential factor across all four types, particularly for industrially integrated attractions, where its contribution reached 49.57%. This highlights that scenery is the primary driving factor shaping IWOM for tourist attractions. For natural ecological attractions, the contribution values of influencing factors were ranked as follows: scenery, Internet popularity, fame level, cost performance, government attention, and hotel accommodation. Notably, the contributions of fame level, cost performance, and Internet popularity were higher for natural ecological attractions compared to other types. This is likely because Jiangxi Province is rich in natural resources and actively promotes its green tourism brand. For historical and cultural attractions, the contribution values were ranked as follows: scenery, Internet popularity, government attention, fame level, hotel accommodation, and cost performance. Among these, cost performance had the lowest contribution value across all attraction types, indicating a minimal impact. This is attributed to the fact that most cultural attractions in Jiangxi Province are free and serve as public resources for visitors. For modern entertainment attractions, the ranking of influencing factors was as follows: scenery, government attention, Internet popularity, fame level, hotel accommodation, and cost performance. It is noteworthy that hotel accommodation and government attention had the highest contribution values among all attraction types. This can be explained by the fact that modern entertainment attractions are often located in commercial districts with convenient facilities, encouraging visitors to stay nearby for further activities. Additionally, these attractions are typically situated in central urban areas, with their development heavily reliant on government planning and support. For industrially integrated attractions, the ranking of influencing factors was as follows: scenery, government attention, fame level, Internet popularity, hotel accommodation, and cost performance. As industrial integration attractions combine elements from multiple industries with tourism resources, they offer diversified tourism products and experiences to meet the varied needs of visitors. Consequently, factors such as scenery play a critical role in attracting tourists and enhancing their experience and satisfaction. This analysis underscores the distinct differences in the factors influencing IWOM across attraction types and highlights the need for tailored strategies that align with the specific characteristics and development needs of each type of tourist attraction.

Figure 11 illustrates the spatial distribution of the contributions of various influencing factors to IWOM for tourist attractions. The contribution of fame level to IWOM across all sampled tourist attractions ranges from 0.01% to 59.08%. Most contributions are concentrated in the 0%–10% range, with 293 tourist attractions falling within this interval. Spatially, the overall contribution of fame level demonstrates a pattern of being higher in the north and lower in the south, with a balanced distribution in the east and west. The contribution of hotel accommodation to IWOM ranges from 0.03% to 48.22%, with 389 tourist attractions having a contribution rate exceeding 10%. The scenery factor shows a contribution range of 1.16%–76.33%. Notably, 244 tourist attractions exhibit a contribution rate of over 40%, accounting for more than 50% of the total sample. Meanwhile, tourist attractions with a contribution rate within the 0%–10% range are distributed across all cities, with approximately 1–2 such attractions per city. This indicates that while Jiangxi Province generally possesses favorable scenic environments, certain tourist attractions still need to improve their scenic appeal to better attract visitors. The contribution of cost performance to IWOM ranges from 0% to 51.98%. For most tourist attractions, the contribution rate is below 10%, covering 391 attractions in total. As the consumption demands of Chinese nationals continue to rise, tourists have become less sensitive to pricing, demonstrating greater tolerance for the cost performance of attractions. Additionally, because most tourist attractions in Jiangxi Province are free to enter, the overall impact of cost performance on IWOM remains relatively low. The highest contribution of cost performance is observed in Yingtan City, while the lowest is in Pingxiang City. The contribution of government attention to IWOM ranges from 0% to 65.82%, with a relatively balanced distribution across all intervals. This reflects the province’s consistent focus on developing tourist attractions and its commitment to establishing Jiangxi as a leading tourism destination. The contribution of Internet popularity to IWOM spans from 0.09% to 59.18%, with the number of tourist attractions gradually decreasing as the contribution rate increases. Specifically, 156 tourist attractions fall within the 10%–20% range. The highest contribution of government attention is observed in Xinyu City, while the lowest is in Jiujiang City. The contribution of Internet popularity to IWOM is primarily concentrated below 30%. Tourist attractions with a contribution rate above 40% for Internet popularity are distributed across all prefecture-level cities, except Yingtan City, Xinyu City, and Ganzhou City. The highest contribution of Internet popularity to IWOM is observed in Ji’an City, while the lowest is in Yingtan City. This refined description highlights the spatial heterogeneity of influencing factors and underscores the significance of targeted strategies to enhance IWOM for tourist attractions.

Discussion

Characterization of the spatial patterns of IWOM in tourist attractions

With the advancement of information technology, OTAs are gradually reshaping the traditional marketing models of the tourism industry. This transformation fosters the integration of online platforms for tourism, accommodation, dining, and other services with physical stores, offering tourists new and varied options for planning their travel (Pinto and Castro, 2019). The IWOM data associated with OTA platforms has become an increasingly significant factor for both consumers and businesses in decision-making processes, profoundly influencing tourists’ purchasing behaviors (Ismagilova et al., 2017). The spatial activities of socio-economic entities within a given region and their interrelationships contribute to the formation of a spatial context (Yin et al., 2004). Spatial structure refers to the organizational framework shaped by human economic activities within a defined geographic area, reflecting the spatial relationships between various elements and systems within the regional economic system. By regulating the key elements of spatial structure, regional development can be optimized to achieve its most effective state (Yin et al., 2004). The spatial distribution of tourist attractions serves as the geographical projection of tourism activities, incorporating the spatial attributes and interrelationships of these activities. The rationality of this distribution directly influences the health and sustainability of tourism destinations (Ghodousi et al., 2020). If the spatial structure of IWOM as perceived by tourists is mapped, it can assist in identifying regional disparities in the development of tourist attractions, thus providing a scientific basis for optimizing regional tourism resource allocation. This study utilizes semantic analysis of online texts to preliminarily identify micro-level characteristic differences among tourist attraction types, suggesting potential strategies for differentiated destination branding and image management. Methodologically, the cross-referencing of Internet data and geospatial information offers a multidimensional perspective for tourism geography research. The combined examination of spatial patterns and online semantic features reveals the distribution characteristics of tourist attraction IWOM across both macro-structural and micro-linguistic dimensions. The application of this mixed-methods approach supports interdisciplinary research by proposing an analytical framework that bridges tourism geography and media geography.

Analysis of influencing factors of IWOM in tourist attractions

Traditional research on the influencing mechanisms of IWOM has predominantly concentrated on disciplines such as management and psychology, with a primary focus on exploring individual difference factors in IWOM and their impact on the dissemination of IWOM (Ling, 2023; Mishra and Satish, 2016). This study posits that the IWOM of tourist attractions serves as an objective reflection of the spatial environment of the tourism destination, effectively capturing the human-environment relationship within the tourism system. Within the framework of human-environment relationship theory, tourists are not only the experiencers of the tourism attraction environment but also the constructors and disseminators of IWOM. Tourist attractions influence tourists’ behaviors through both physical and media spaces, which subsequently feed back into the IWOM. In turn, IWOM impacts tourists’ decision-making through information interactions, progressively guiding the reshaping of the spatial environment of tourist attractions. Furthermore, this study draws on customer perceived value theory, government intervention theory, and tourist expectation theory to specifically analyze the pathways through which physical and media factors influence IWOM. Overall, the framework of the IWOM influencing mechanism, constructed by integrating multiple disciplinary theories, effectively reflects the reciprocal relationship between tourist attractions and their IWOM. This approach expands the research perspective on IWOM in tourist attractions. Additionally, within the context of interdisciplinary integration, we employ machine learning methods based on the influencing mechanism framework to quantitatively measure the factors influencing IWOM in tourist attractions. In contrast to the rigid assumptions of traditional statistical regression models, the XGBoost-SHAP model employed in this study provides accurate and easily interpretable predictions for factor analysis (Jas and Dodagoudar, 2023). The XGBoost model does not impose stringent assumptions on variables and offers high-precision predictive capabilities, addressing the limitations of traditional regression models, while the SHAP method provides both local and global interpretability. Current quantitative studies on the influence mechanisms of IWOM for tourist attractions within tourism geography mainly employ methods such as Geographically Weighted Regression and Geodetector. This study introduces machine learning algorithms as an alternative approach, providing a methodological avenue for analyzing nonlinear relationships between spatial determinants at various scales and IWOM propagation patterns.

Strategies for the healthy development of tourist attractions in Jiangxi province from the perspective of IWOM

Based on the research findings, the following strategic recommendations can be proposed. First, it is essential to scientifically and rationally plan regional development to create growth poles for regional tourism. The joint development of regional tourist attractions can strengthen the connections and communication between regions, promote integration, and help form a regional brand, thus enhancing the overall competitiveness of regional tourism (Luongo et al., 2023). In Jiangxi Province, the IWOM of tourist attractions is notably low in central Shangrao, southern Jiujiang, and parts of Ganzhou. These regions should focus on coordinated marketing efforts, jointly planning a series of activities, tapping into local cultural assets, and attracting more tourists to participate and engage with the destination. By developing tourist attractions with unique, innovative features that attract large crowds, these areas can create growth poles for regional tourism development, thereby enhancing the overall IWOM. Through collaborative efforts, the fame level and influence of these tourist destinations can be increased, leading to mutual development and prosperity within the region. Furthermore, the study indicates that the contribution of influencing factors on the IWOM of tourist attractions varies across different prefecture-level cities. In addition to the significant impact of scenery in all cities, government attention and Internet popularity also play substantial roles.

Second, it is crucial to enhance the core appeal of tourism services and amplify the volume of positive IWOM. Scenery, as a major contributor to the IWOM, should be prioritized, with each tourist attraction strategically planning its layout, developing high-quality, unique landscapes, and enhancing both the fame level and appeal of the attraction. Government attention and Internet popularity are key factors influencing the IWOM, which necessitates effective guidance from local authorities, increased marketing efforts, and a focus on boosting online visibility. Given the considerable differences in the contribution of influencing factors across different types of tourist attractions, it is essential to implement tailored strategies based on the unique characteristics of each attraction. For instance, natural ecology attractions exhibit a higher contribution from cost performance compared to other types, as these attractions typically have larger areas, more complex management, and higher admission fees. As a result, natural ecology attractions need to strike a balance between pricing and tourism supply (Li et al. 2023). An analysis of high-frequency terms in review texts suggests that these attractions should prioritize the development of key tourist draws, improve transportation infrastructure, and enhance safety measures. Historical and cultural attractions, with their prominent contributions from both scenery and Internet popularity, should focus on fully exploring local cultural heritage, emphasizing the unique features of the attractions, and improving tourist satisfaction. Additionally, efforts should be made to intensify online marketing campaigns to foster greater social discourse and interest (Han et al., 2023). Moreover, leveraging modern digital technologies to develop new attractions, enhance staff services, and introduce more cultural products and souvenirs will further enhance the tourist experience. For modern amusement attractions, hotel accommodation and government attention have a greater influence on IWOM than other types (Aguinis et al. 2023). Therefore, accommodations near these attractions must provide comprehensive services, and governments should set high standards and provide robust support for the development of these destinations. Furthermore, modern amusement attractions should focus on developing engaging, leisure-oriented, and safe entertainment options while enhancing infrastructure and basic services. Industrial integration attractions, due to their comprehensive nature, often have higher scenery ratings and fame levels compared to other types of attractions. Thus, these attractions should integrate unique tourism resources, foster in-depth collaborations, and learn from best practices to provide tourists with a superior experience (Lu, 2022). Additionally, enhancing brand development, strengthening publicity efforts, and focusing on WOM marketing will improve the visibility of industrial integration attractions. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation, along with enhancing staff service quality and increasing interactivity and playability, should be prioritized to maximize the overall impact.

Research limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, platform access constraints during data collection restricted the dataset to IWOM from major platforms, notably Ctrip and Tongcheng Travel. While reasonably representative, inherent differences in platform operations and user bases may introduce data variations. The constrained scope necessitates cautious generalization. Future research should integrate multi-platform datasets to enhance robustness, particularly given Web 2.0’s exponential growth of tourism IWOM.

Second, though employing human-environment theory to examine IWOM’s macro-micro characteristics in Jiangxi’s attractions, the framework omits individual cognition and decision-making processes. Its emphasis on collective behavior lacks a granular analysis of how psychological factors like perception biases and emotional responses, along with individual decision logic, dynamically shape IWOM generation. Subsequent studies should adopt mixed methods, including tourist surveys and behavioral experiments, to advance micro-mechanism understanding. Addressing these gaps would strengthen theoretical and practical contributions to sustainable destination management.

Conclusion

This study used Jiangxi Province, rich in tourism resources, as a case study, employing a combination of spatial and semantic analysis methods to examine the spatial patterns and high-frequency word characteristics of IWOM for tourist attractions. The research revealed both macro and micro differences in IWOM across different types of tourist attractions. Grounded in human–environment relationship theory, the study integrated multidisciplinary theories to construct an influencing mechanism framework for IWOM in tourist attractions, followed by a quantitative analysis of the factors influencing IWOM in Jiangxi Province using the XGBoost-SHAP model. The results indicated that the spatial structure of IWOM in tourist attractions exhibited a multi-core, uneven distribution. Key factors such as tourist attractions, management services, transportation facilities, behavioral motivations, and subjective experiences were the main aspects that tourists focused on during their travel experiences. Although IWOM varied across different types of tourist attractions, high-density areas were predominantly located in regions with abundant tourism resources and relatively developed economies, closely aligning with the geographic distribution patterns of these attractions. Furthermore, differences in the focal points of tourist feedback across various types of attractions suggested that personalized strategies should be implemented to enhance IWOM and improve the overall image of tourist attractions. Scenery was found to have the greatest contribution to the overall IWOM of tourist attractions. For natural ecology attractions, fame level and cost performance had a more significant influence on IWOM compared to other types of attractions. For historical and cultural attractions, scenery and Internet popularity had a slightly greater impact on IWOM compared to other types. In modern amusement attractions, hotel accommodation and government attention had a stronger influence on IWOM than in other types of attractions. Similarly, for industrial integration attractions, scenery also had a more substantial impact on IWOM compared to other categories. This study comprehensively analyzed the macro and micro characteristics of IWOM across various dimensions and types of tourist attractions and introduced machine learning methods to explore the influencing factors of IWOM. This study develops an analytical framework for tourist attraction IWOM, contributing to understanding the relationship between destination marketing strategies and spatial resource allocation. The application of multi-source data fusion methodology in specific case regions offers a multidimensional perspective, which may support attraction management decision-making.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available in the Harvard Dataverse repository at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/U3NVV1.

References

Aguinis H et al. (2023) The why, how, and what of public policy implications of tourism and hospitality research. Tour Manag 97:104720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104720

Akdim K (2021) The influence of IWOM. Analyzing its characteristics and consequences, and future research lines. Span J Mark -ESIC 25(2):239–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-10-2020-0186

Arismayanti NK, Andiani ND, Kusyanda MRP (2024) Tourist satisfaction model: structural relationship of destination image, electronic word of mouth, and service quality in Bali destination. Nurture 18(2):360–372. https://doi.org/10.55951/nurture.v18i2.623

Bailey TC, Gatrell AC (1995) Interactive spatial data analysis. Harlow Essex. https://doi.org/10.2307/2265559

Chen T, He T, Benesty M, et al. (2015) Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R package version 0.4-2 1(4):1–4

Chen W (2024) Exploring the dynamics of electronic word-of-mouth in Chinese tourism: a social network perspective. J Knowl Econ 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01780-9

Chevalier JA, Mayzlin D (2006) The effect of word of mouth on sales: online book reviews. J Mark Res 43(3):345–354. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.43.3.345

Duan W, Gu B, Whinston AB (2008) Do online reviews matter?—An empirical investigation of panel data. Decis Support Syst 45(4):1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2008.04.001

Ergün S (2023) Explaining Xgboost predictions with SHAP value: a comprehensive guide to interpreting decision tree-based models. N Trends Comput Sci 1(1):19–31. https://doi.org/10.3846/ntcs.2023.17901

Forman C, Ghose A, Wiesenfeld B (2008) Examining the relationship between reviews and sales: the role of reviewer identity disclosure in electronic markets. Inf Syst Res 19(3):291–313. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1080.0193

Ghodousi M, Sadeghi-Niaraki A, Rabiee F, Choi SM (2020) Spatial-temporal analysis of point distribution pattern of schools using spatial autocorrelation indices in Bojnourd City. Sustainability 12:26. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187755

Grosspietsch M (2006) Perceived and projected images of Rwanda: visitor and international tour operator perspectives. Tour Manag 27(2):225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2004.08.005

Guttentag D (2015) Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr issues Tour 18(12):1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Han Y, Liu Y, Wang C et al. (2023) Assessment of the cultural-natural importance of the tourist attractionss from a network perspective. Landsc Urban Plan 239:104861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104861

Ismagilova E, Slade EL, Rana NP et al. (2022) The effect of electronic word of mouth communications on intention to buy: a meta-analysis. Inf Syst Front 22:1203–1226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-019-09924-y

Ismagilova E, Dwivedi YK, Slade E et al. (2017) Impact of eWOM. Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the marketing context: a state of the art analysis and future directions 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52459-7_6

Jas K, Dodagoudar GR (2023) Explainable machine learning model for liquefaction potential assessment of soils using XGBoost-SHAP. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 165:107662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2022.107662

Jasin M (2022) The role of social media marketing and electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention of SMEs product. J Inf Syst Manag(JISMA 1(4):54–62

Kim J, Lee C (2017) Examining the role of relationship factors on IWOM effectiveness in social media. Int J Internet Mark Advert 11(2):103–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMA.2017.084078

King RA, Racherla P, Bush VD (2014) What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: a review and synthesis of the literature. J Interact Mark 28(3):167–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2014.02.001

Kloog I, Haim A, Portnov BA (2009) Using kernel density function as an urban analysis tool: Investigating the association between nightlight exposure and the incidence of breast cancer in Haifa, Israel. Comput Environ Urban Syst 33(1):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2008.09.006

Lee M, Youn S (2009) Electronic Word of Mouth (IWOM): how IWOM plat for influence consumer product judgment. Int J Advert 28(3):473–499. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048709200709

Li F, Liao X, Liu J et al. (2023) Investigating the tourism image of mountain tourist attractionss in China through the lens of tourist perception. J Mt Sci 20(8):2298–2314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-022-7791-x

Li G, Elliot S, Choi C (2010) Electronic word-of-mouth in B2C virtual communities: An empirical study from CTrip. com. J Glob Acad Mark 20(3):262–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/12297119.2010.9707352

Ling M (2023) Research and effectiveness evaluation of word-of-mouth marketing strategies based on social media. Adv Econ Manag Res 8(1):352–352. https://doi.org/10.56028/aemr.8.1.352.2023

Liu H, Jayawardhena C, Shukla P et al. (2024) Electronic word of mouth 2.0 (IWOM 2.0)–The evolution of IWOM research in the new age. J Bus Res 176:114587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114587

Liu Y (2006) Word of mouth for movies: Its dynamics and impact on box office revenue. J Mark 70(3):74–89. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.3.74

Loureiro SMC, Kastenholz E (2011) Corporate reputation, satisfaction, delight, and loyalty towards rural lodging units in Portugal. Int J Hospit Manag 30(3):575–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.10.007

Lu Y (2022) The measurement of high-quality development level of tourism: Based on the perspective of industrial integration. Sustainability 14(6):3355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063355

Lundberg S M, Erion G, Chen H, et al. (2020) From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat Mach Intell 2(1): 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9

Luo Q, Zhong D (2015) Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tour Manag 46:274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.07.007

Luongo S, Sepe F, Del Gaudio G (2023) Regional innovation systems in tourism: The role of collaboration and competition. J Open Innov Technol Mark Complex 9(4):100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100148

Mao L, Xia J, xie W (2024) Research on the integration strategy of Jiangxi into the Yangtze River Delta tourism. Jiang xi Soc Sci 44(03):59–67

Maškarin Ribarić H, Ribarić I (2013) Government intervention in driving the development of sustainable tourism. 2nd International Scientific Conference Tourism in South East Europe.[S.l.] : SSRN

Medeková K, Pompurová K (2024) Dynamics of electronic word-of-mouth: insights from destination management organizations. Theor Pract Res Econ Fields 15(2):319–334. https://doi.org/10.14505/tpref.v15.2(30).13

Mishra A, Satish SM (2016) eWOM: Extant research review and future research avenues. Vikalpa 41(3):222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090916650952

Oliver RL (1980) A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Mark Res 17(4):460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

Pinto I, Castro C (2019) Online travel agencies: factors influencing tourists’ purchase decisions. Tour Manag Stud 15(2):7–20. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1550-5867

Prendergast G, Ko D, Siu Yin VY (2010) Online word of mouth and consumer purchase intentions. Int J Advert 29(5):687–708. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048710201427

Qiu Y, Yin J, Zhang T et al. (2021) Spatiotemporal dynamic analysis of a-level tourist attraction in Guizhou Province, China. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf 10(8):568. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080568

Sukaris S, Hartini S, Mardhiyah D (2020). The effect of perceived value by the tourists toward electronic word of mouth activity: the moderating role of conspicuous tendency. J Siasat Bisnis 1–17. https://doi.org/10.20885/jsb.vol24.iss1.art1

Sun T, Youn S, Wu G et al. (2006) Online word-of-mouth (or mouse): An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J Comput-Mediat Commun 11(4):1104–1127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00310.x

Tsung-Nien K (2020) Research on evaluation of innovative 3-tier business model on online travel agency. Res evaluation innov 43–53. https://doi.org/10.20474/jabs-6.2.1

Wang T, Wang L, Ning ZZ (2020) Spatial pattern of tourist attractions and its influencing factors in China. J Spat Sci 65(2):327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14498596.2018.1494058

Wang C (2016) The influence of electronic word-of-mouth on the decision-making of online travel booking. 2016 International Symposium on Computer, Consumer and Control (IS3C). IEEE pp. 934–937. https://doi.org/10.1109/IS3C.2016.237

Wang D, Chen Y (2019) A neural computing approach to the construction of information credibility assessments for online social networks. Neural Comput Appl 3:259–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-018-3734-4

Wang Z, Zeng Z, Yang J, et al. (2023) Research on the perception of homesickness in ancient town landscape based on analysis of online texts and the IPA Model. Southwest Univ Nat Sci Ed 45(11):210–218

Yang Z, S Chen (2007) On “Tourism Destination” and “Tourism Transit Venue”. Tour Tribune (02):27–32

Yin Y, Lu Y, Deng Z (2004) A review of researches on tourism spatial structure in China. Tour Sci 04:49–54+61

Zeithaml VA (1988) Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Mark 52(3):2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42001189/No. 42201187) and the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education Graduate Innovation Fund Project (Grant No. YJS2023012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ and BH collected data. XH and LZ conducted empirical analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. XH obtained funds to support the project. QY and XH supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research study did not involve human participants, animals, or sensitive data requiring ethical approval. As such, ethical approval was not sought from an institutional review board or ethics committee.

Informed consent

This study did not involve human participants, human data, or human tissue. Therefore, informed consent was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, X., Jiang, L., Li, Q. et al. Characteristics and influencing factors of internet word-of-mouth of tourist attractions: evidence from Jiangxi, China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05713-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05713-y