Abstract

The integration of digital technology into rural governance has reshaped the governance model, providing new opportunities for promoting digital rural governance. However, the empowering role of digital technology in rural governance has not yet been fully realized, and digital rural governance still faces many challenges. This paper, based on the assumption of bounded rationality, constructs a dynamic evolutionary game model involving three parties: local governments, village collectives, and villagers. By incorporating system dynamics for numerical simulation, it explores in depth the strategic choices of three parties under different scenarios. The study finds that under certain conditions, there exists an equilibrium strategy that satisfies the interests of local governments, village collectives, and villagers. Government subsidies are an important external factor influencing the strategic choices of village collectives and villagers, but excessively high subsidies can increase local governments’ fiscal burden. Digital literacy is an internal driving factor that ensures village collectives and villagers participate in digital rural governance. In the long term, even with reduced or entirely absent government subsidies, higher digital literacy can effectively achieve rural digital governance. This paper helps in comprehensively understanding the micro-level mechanisms of rural digital governance, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing the incentive policy system and promoting rural digital governance. It also offers a new perspective on how to advance digital rural governance in the absence of government subsidies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid development and application of digital technology provide an important opportunity for the transformation of traditional rural governance (Li, 2022). Promoting digital rural governance is of significant practical importance for advancing rural revitalization in poverty alleviation areas, accelerating the modernization of agriculture and rural areas, and contributing to the construction of a digital China. To this end, the central government has intensively planned to accelerate digital rural development, providing legal guarantees and institutional support for digital rural governance through top-level design. Local governments have actively responded by implementing a series of specific policies and projects to improve the construction of digital infrastructure and the application of data platforms, ensuring that rural governance becomes more intelligent and efficient. However, the overall level of digitalization in rural areas of China is still relatively low, and the empowering role of digital technology in rural governance has not been fully realized (Yang, 2021).

Current research on digital rural governance mainly focuses on the mechanisms through which digital technology empowers rural governance, the development challenges, and the pathways to achieve this transformation.

From the perspective of mechanisms, on the one hand, digital technology can improve the interaction model among multiple stakeholders, promoting rural social governance towards a bidirectional and interactive transformation (Mergel et al., 2019). Public service platforms built on digital technology can connect “atomized” villagers dispersed across different spaces, thereby reshaping villagers’ discourse system and promoting village self-governance. On the other hand, digital technology can not only strengthen the monitoring of grassroots power and standardize the governance behavior of officials but also enhance villagers’ subjective rights, promoting the transformation of rural public dynamics from “authority-dominated” to “interactive and game-based.” This helps achieve comprehensive coverage, broad participation, and full-process supervision in rural governance (Du, 2020).

However, digital rural governance in China is still in an early stage, facing external challenges such as incomplete hardware infrastructure and irregular policy implementation (Jiang, 2021). Additionally, issues related to the lack of digital literacy and low governance willingness among stakeholders should not be overlooked. To address these development challenges, it is necessary to strengthen the top-level design and implement relevant policies for digital rural governance at the institutional level. Additionally, from a practical perspective, efforts should be made to enhance digital infrastructure, improve digital literacy among stakeholders, and establish a rural governance system driven by endogenous demand (Tang, 2022). In addition, the integration of digital technology into rural areas requires attention to the capacity of rural organizations. Establishing organizational rules and implementing collective action are essential prerequisites for embedding digital technology (Pavan, 2014). Relying on rural organizations helps establish a pattern of multi-stakeholder governance, improve the institutional framework, and promote the sustainable development of rural society (Shen, 2020).

In summary, existing research has recognized the importance of digital rural governance but has primarily focused on analyzing mechanisms and external macro factors. There is less attention on the intrinsic logic and operational mechanisms of achieving collaborative governance among multiple stakeholders, and there is insufficient micro-level analysis of how digital technology empowers rural governance.

In reality, information asymmetry and conflicting interests among multiple stakeholders in rural governance complicate their interactions. Investigating how digital technology empowers rural governance requires an in-depth analysis of the interest relationships between local governments, village collectives, and villagers. Evolutionary game theory is a powerful tool for analyzing individual behavior and strategy evolution in complex systems (Xie et al., 2018). Due to bounded rationality, local governments, village collectives, and villagers find it difficult to determine the optimal strategy in a single game. They need to adjust their decisions based on past experiences and environmental changes, gradually finding the optimal strategy through repeated games. The process of finding the optimal strategy involves multi-level interactions among multiple stakeholders, which aligns with the analytical framework of evolutionary game theory.

Existing studies have used evolutionary game models to analyze the multi-stakeholder dynamics in rural governance. For example, Lv et al. (Lv, 2020) constructed an evolutionary game model with local governments, village collectives, and councils as the stakeholders to explore the stability of rural governance from the perspective of the integration of “rural elite”. Yin et al.(Yin et al., 2024) constructed a three-party game model involving village administrative organizations, new agricultural business entities, and peasant households, underscoring the need for positive incentives and a robust fault-tolerance mechanism to foster collaborative governance. Zheng et al. (Zheng et al., 2024) combine evolutionary game theory to analyze the digital transformation of agriculture, emphasizing the importance of government subsidies. However, existing evolutionary game studies mainly focus on traditional rural governance models, with limited use of three-party evolutionary game models to explore the micro-mechanisms of digital rural governance.

Drawing on existing research, with the aim of clarifying the micro-level mechanisms for achieving digital rural governance, this paper constructs a three-party evolutionary game model involving local governments, village collectives, and villagers to analyze the diversity and stability of the strategies of multiple stakeholders. The potential marginal contributions of this paper are mainly reflected in the following two aspects: First, by constructing a dynamic evolutionary game model, this paper illustrates the strategy choices and evolutionary paths of stakeholders at different stages, thus expanding the micro-level research on digital rural governance. Second, in the early stages, government subsidies are an important institutional arrangement for enhancing the willingness of village collectives and villagers to participate. However, existing research rarely addresses how to promote digital rural governance when government subsidies are reduced or entirely absent. This paper uses digital literacy as a moderating variable to analyze the choices of village collectives and villagers in scenarios where government subsidies are reduced or absent, providing a new perspective for advancing digital rural governance.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical analysis. Sections 3 constructs an evolutionary game model. Section 4 conducts numerical simulation combining system dynamics. The conclusions and implications are explained in Section 5.

Theoretical analysis

Application scenarios of digital technology empowering rural governance

Digital rural governance aims to apply information, digital, and network technologies to the social governance in rural areas, empowering various aspects such as rural Party-building, social governance, lifestyle, and ecological protection. It seeks to promote digital symbiosis and collaboration across all fields of rural governance (Zhao, 2021).

First, Party-building has always been the fundamental task in rural governance (Cao, 2020). Rural digital Party-building relies on new-generation information technologies to integrate fragmented information and dispersed resources, enrich the functions of digital Party-building platforms, and closely combine grassroots Party-building with rural governance, thereby improving service quality. The digital practices of rural Party-building mainly focus on building Party affairs information databases and systems for training Party members and cadres. For example, Zigui County in Hubei Province established the “Smart Party-building Cloud Platform” to integrate Party member information and enhance management efficiency, while the “Hanzhong Smart Party-building Cloud Platform” in Hanzhong, Shanxi Provinc,e serves as an important medium for Party member education.

Secondly, rural governance covers a wide range of areas, involves numerous tasks, and requires substantial effort. The traditional governance model faces limitations such as inefficiency, cumbersome procedures, and unscientific decision-making, making it difficult to meet the needs of rural revitalization in the current era (Xiao et al., 2024). Promoting the deep integration of digital technology into the rural governance system can enhance governance efficiency, enable precision governance, and foster a collaborative governance model with multiple stakeholders. For example, Ninghai County launched the “Villagers’ e-Access” village-level management service platform, which includes six major functions: village introduction, community services, public feedback, information disclosure, consultation and communication, and grassroots Party-building, serving as an important medium for multi-stakeholder collaborative governance. The “Zheliban” platform, which incorporates the concept of “at most one visit,” integrates resources from top to bottom to offer government services and policy information, improving the grassroots public service system and increasing villagers’ participation in rural governance.

Thirdly, digital technology has significantly transformed farmers’ lifestyles, particularly in various aspects of rural life such as healthcare, shopping, transportation, and entertainment. New models built upon the “Internet + “ strategy further enable one-stop services for rural governance, reducing the cost of villager self-governance and promoting a smarter way of life for villagers (Feng, 2020). For example, the Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital assisted in building the first “Health Hut” in Suotuo Village, Yonghe County, Shanxi Province, enabling over 500 residents to remotely access healthcare resources from top-tier hospitals through the village health clinic. To address the issue of villagers delaying treatment for minor ailments or enduring serious illnesses, the government of Deqing County, Zhejiang Province developed a “Digital + Rural Healthcare” system to facilitate online consultations and medical services, allowing villagers to receive expert healthcare without leaving the village.

Fourthly, the development of digital technology has advanced rural ecological environment governance toward intelligent monitoring and long-term management, providing new methods for modernizing ecological governance. For example, Anji County in Zhejiang Province, known as the “Home of Bamboo in China,” has used drones and satellite remote sensing technology to monitor bamboo forests in real-time, preventing illegal logging and fires. Additionally, big data analysis has been applied to assess the growth of bamboo, optimize bamboo forest management, and improve ecological protection.

The mechanism of digital technology empowering rural governance

Institutional analysis and development framework

The institutional analysis and development framework (IAD Framework) is a comprehensive analytical framework consisting of components such as external variables, action arena, patterns of interaction, evaluation criteria, and outcomes. The core of the IAD framework is the action situation within the action arena, which determines how individuals link exogenous variables to outcomes through their actions. This is also the key to using the IAD framework for institutional analysis. The IAD framework aims to explain how exogenous factors, including rules, influence policy outcomes in the self-governance of common-pool resources. It provides resource users with a set of institutional design solutions and standards that can enhance trust and cooperation (Kiser and Ostrom, 1982). The IAD framework has been continuously refined in practical applications and is now widely used in various public governance scenarios, providing a reference for understanding rural governance in China (Ostrom, 2019; Wang, 2021). This paper, based on the rural governance IAD framework proposed by Wang (Wang, 2022) and incorporating findings from field research, constructs an institutional analysis framework for rural governance from three dimensions: rule supply, rule enforcement, and rule maintenance (Wang, 2021), as shown in Fig. 1.

In the dimension of rule supply, rural governance rules mainly include formal rules based on national laws and policies, semi-formal rules such as village regulations and conventions, and other informal rules. In the practice of rural governance in China, institutional construction at the rule level is relatively well-developed, with legal provisions at the national level and institutional arrangements at the regional level. However, issues such as incomplete self-governance capacity and the lack of an effective policy consultation mechanism have constrained the efficiency of rural rule supply.

In the dimension of rule enforcement, mutual supervision among multiple stakeholders is an important foundation for enforcing rural governance rules, and a good conflict mediation mechanism helps resolve conflicts and issues that pre-arranged rules cannot address. However, the supervision and mediation mechanisms in rural governance in China currently rely mainly on local governments, and the internal mutual supervision mechanisms within rural communities are not yet well-developed.

In the dimension of rule maintenance, rural governance relies on multi-level nested organizations, particularly village collectives, which play an important coordinating role in the governance process. Building service platforms for information sharing, communication, consultation, and feedback through village collectives is key to enhancing the capacity for self-governance. However, excessive administrative intervention at the current stage affects villagers’ willingness to participate in governance, leading to difficulties in rural governance (Sun, 2020).

The mechanism of digital technology empowerment

Digital technology is essentially an exogenous factor, embedded in rural society mainly through digital infrastructure development and the establishment of digital service platforms. Based on the connectivity and accessibility of technology, it provides space and support for digital rural governance (Galdeano‐Gómez et al., 2011). From the perspective of hardware-based digital infrastructure, according to the China Digital Rural Development Report (2022), by the end of 2021, the broadband coverage rate of administrative villages nationwide reached 100%, achieving full coverage of rural network infrastructure. This hardware connectivity has propelled farmers into the digital age. In terms of software-based digital platforms, building integrated service platforms based on digital technology has become a new trend in advancing digital governance across regions. Examples include the “1 + 1 + 4 + N” holistic smart governance system built by Kunyang Town in Zhejiang Province, and the “eLanmingguo” mini-program developed by the Agricultural and Rural Bureau of Yueqing City, Zhejiang Province, which provides information on education, policies, insurance, and more. The accessibility of software has opened new digital channels to serve farmers in their production and daily life. Overall, during the process of embedding exogenous digital technology into rural society, the continuous coverage of digital infrastructure and the constant improvement of digital platform functionalities have enabled farmers to access more quality information and services, thereby laying a solid foundation for digital rural governance.

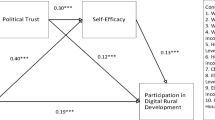

Digital technology provides new solutions to address the multiple institutional challenges currently faced in rural governance in China, primarily by reducing the costs of information searching, tracking, and transmission. It addresses insufficient, inefficient and inadequate issues from the three dimensions of rule supply, rule enforcement, and rule maintenance. The mechanism of digital technology empowering rural governance is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Firstly, digital technology ensures villagers’ access to information, reducing search costs and improving the efficiency of rule supply in rural governance. It makes it easier for villagers to promptly refine governance provisions based on practical experience, thereby enhancing the scientific basis and appropriateness of village regulations and policies. This, in turn, improves villagers’ sense of self-efficacy, encouraging them to participate more actively in rural governance (Zimmerman, 1990).

Secondly, digital technology can achieve transparency and dynamic traceability throughout the rural governance process, reducing information tracking costs. It helps accurately record the specific actions of rural governance stakeholders, clarifying roles and responsibilities and establishing an effective supervision and mediation mechanism. This greatly facilitates mutual supervision among stakeholders and provides a solid data foundation and pathway for “targeted governance.” (Meng, 2021)

Thirdly, the decentralization enabled by digital technology helps establish a multi-stakeholder governance structure, reducing the sole reliance on local governments for rural governance. The digital service platforms built by collective organizations facilitate the seamless flow of governance information both online and offline, becoming an important medium for increasing the frequency of communication between the government and villagers. Through orderly information transmission, efficient information governance, and secure information sharing, digital technology can effectively reduce information transmission costs, overcome the shortcomings of high costs, low efficiency, and lack of transparency in traditional governance models, and achieve transparent, dynamic, and precise rural governance (University, 2020).

Model construction

Based on the theoretical analysis in Section 2.2.2, digital technology enhances rural governance by reducing the costs of information searching, transmission, and tracking, thereby improving rule supply, enforcement, and maintenance. In this section, we adopt a tripartite evolutionary game model involving three stakeholders—local government, villagers, and village collectives—each with distinct strategy choices and payoff structures. By constructing the payoff matrices for all stakeholders and incorporating replicator dynamics, we analyze the evolutionary process and stability of their strategic interactions, aiming to explore the behavioral evolution mechanism of rural governance under the empowerment of digital technology. In this model, the level of digital infrastructure development (β) is used to capture the impact of digital technology on governance participation costs, reflecting the cost-reduction mechanism proposed in the theoretical analysis. Meanwhile, digital literacy (λ) represents the stakeholders’ capacity and willingness to engage in digital governance, which in turn affects their expected payoffs—corresponding to the theoretical discussion on how digital technology enhances governance efficiency and mobilization. In addition, the model introduces other benefit and cost parameters to reflect how digital technology reshapes the incentive mechanisms and responsibility structures in the tripartite game.

The model construction process is as follows:

Scenario description

Evolutionary game theory combines principles from biological evolution and game theory, starting from the assumption of bounded rationality. It focuses on individuals adjusting their strategies during the dynamic evolutionary process through learning and imitation to reach a stable state, effectively addressing the limitations of the complete rationality assumption and multiple equilibrium issues in classical game theory. Evolutionary game theory can provide an analytical framework to explain how to promote digital rural governance, serving as an effective tool for understanding the behavioral strategies and interactions among local governments, village collectives, and villagers.

Specifically, digital rural governance is a process of “reconstructing the countryside with digital technology.” Its characteristics of informatization, networking, and intelligence are gradually being embedded into grassroots governance, unleashing the “digital dividend” that supports comprehensive agricultural upgrades, rural progress, and overall farmer development (Liao, 2023; Bing, 2023). However, the non-uniform development of digital infrastructure and the diversity in digital technology user groups have inevitably led to the emergence of “digital divide” phenomena such as digital barriers, digital inequality, and digital space segregation (Salemink et al., 2017). Rural population aging further exacerbates the marginalization of vulnerable groups. Older laborers, limited by learning capabilities and risk-averse attitudes, tend to prefer traditional rural governance models, making it difficult for digital technology to achieve the desired outcomes in rural areas (Lu, 2023). Digital technology can enhance the scientific basis of government decision-making and improve management efficiency. However, the dispersal and mobility of villagers lead to increasingly diverse interests and needs, resulting in significant organizational costs for local governments (Li, 2023). Government participation in rural governance urgently requires the intervention of intermediary organizations to offset organizational costs. The cooperative tradition, resource advantages, and organizational strengths of village collectives can significantly reduce organizational costs (Zhou, 2020). Local governments, relying on village collectives to build digital service platforms, can effectively lower platform construction investment as well as communication and coordination costs. The standardization of village collectives can also significantly reduce platform operation and government supervision costs. Successful organizations may be rewarded to boost their governance motivation. Villagers, as direct beneficiaries of the digital rural governance, gain from the collaboration between local governments and village collectives, thereby enhancing their willingness to participate in governance and establishing a multi-stakeholder governance structure. Based on this, this paper constructs a “local governments—village collectives—villagers” three-party evolutionary game model. The game tree among the three parties is shown in Fig. 3.

Model assumption

Assumption 1: One of the central principles of evolutionary game theory is that agents participate in repeated games under the assumption of bounded rationality until the game system evolves toward a stable state over time. This model involves three primary stakeholders: local governments, village collectives and farmers. Every stakeholder operates under bounded rationality, continuously learning from one another throughout the game process to make decisions that best align with the evolving environment and their own interests.

Assumption 2: Local governments, as administrators, have two strategies. The first strategy is to subsidize, which is denoted as \({F}_{1}\), with a probability of \(x\). And the second strategy is not to subsidize, which is denoted as \({F}_{2}\), with a probability of \(1-x\). The set of strategies for governments is \(\left({F}_{1},{F}_{2}\right)=(x,1-x)\).

Assumption 3: Village collectives, as coordinators, and there are also two strategies. The first strategy is digital governance, which is denoted as \({E}_{1}\), with a probability of \(y\). And the second strategy is traditional governance, which is denoted as \({E}_{2}\), with a probability of \(1-y\). The set of strategies for village collectives is \(\left({E}_{1},{E}_{2}\right)=(y,1-y)\).

Assumption 4: Farmers, as direct participants in rural governance, and there are two strategies. The first strategy is to participate, which is denoted as \({J}_{1}\), with a probability of \(z\). And the second strategy is not to participate, which is denoted as \({J}_{2}\), with a probability of \(1-z\). The set of strategies for farmers is \(\left({J}_{1},{J}_{2}\right)=(z,1-z)\).

The game tree is shown in Fig. 3.

The variables and their denotations used in this paper are listed in Table1.

Expected payoff and replicator dynamics equation

Payoff matrix

Based on the above assumptions, the payoff matrix for the “local governments—village collectives—villagers” three-party game can be obtained, as shown in Table 2.

Expected Payoff

Let the expected payoffs for local governments when choosing to subsidize and not subsidize be \({E}_{11}\) and E12, respectively, with an average payoff of \(\bar{{E}_{1}}\). Then:

Let the expected payoffs for village collectives when choosing between digital governance and traditional governance be \({E}_{21}\) and \({E}_{22}\), respectively, with an average payoff of \(\bar{{E}_{2}}\). Then:

Let the expected payoffs for villagers when choosing to participate and not participate be \({E}_{31}\) and \({E}_{32}\), respectively, with an average payoff of \(\bar{{E}_{3}}\). Then:

Replicator dynamics equation

Local stability strategy analysis

Local governments

According to the stability conditions of the replicator dynamics equation, when \(F\left(x\right)=0\) and \({F}^{{\prime} }(x) < 0\), the point is an evolutionary stable point. (1) When \(\beta {C}_{g}-y\lambda {A}_{O}-z\lambda {A}_{V}=0\), \(F\left(x\right)\equiv 0\). In this case, the local governments’ strategy is not influenced by the evolutionary system, and any strategy is a stable strategy. (2) When \(\beta {C}_{g}-y\lambda {A}_{O}-z\lambda {A}_{V} > 0\), \(F^{\prime} (x)|(x=1) < 0\), \(F^{\prime} (x)|(x=0) > 0\). In this case, \(x=1\) is local governments’ evolutionary stable strategy. (3) When \(\beta {C}_{g}-y\lambda {A}_{O}-z\lambda {A}_{V} < 0\), \(F{\prime} (x)|(x=1) > 0\), \(F^{\prime} (x)|(x=0) < 0\). In this case, \(x=0\) is local governments’ evolutionary stable strategy.

Village collectives

According to the stability conditions of the replicator dynamics equation, when \(F\left(y\right)=0\) and \({F}^{{\prime} }(y) < 0\), the point is an evolutionary stable point. (1) When \(x\lambda {A}_{O}+z\alpha R+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2}-z{R}_{O}=0\), \(F\left(y\right)\equiv 0\). In this case, the village collectives’ strategy is not influenced by the evolutionary system, and any strategy is a stable strategy. (2) When \(\lambda {A}_{O}+z\alpha R+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2}-z{R}_{O} > 0\), \(F{\prime} (y)|(y=1) < 0\), \(F{\prime} (y)|(y=0) > 0\). In this case, \(y=1\) is village collectives’ evolutionary stable strategy. (3) When \(x\lambda {A}_{O}+z\alpha R+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2}-z{R}_{O} < 0\), \(F{\prime} (y)|(y=1) > 0\), \(F{\prime} (y)|(y=0) < 0\). In this case, \(x=0\) is village collectives’ evolutionary stable strategy.

Villagers

According to the stability conditions of the replicator dynamics equation, when \(F\left(z\right)=0\) and \({F}^{{\prime} }(z) < 0\), the point is an evolutionary stable point. (1) When \(x\lambda {A}_{V}+y\left(1-\alpha \right)R+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2}-y{R}_{V}=0\), \(F\left(z\right)\equiv 0\). In this case, the villagers’ strategy is not influenced by the evolutionary system, and any strategy is a stable strategy. (2) When \(x\lambda {A}_{V}+y\left(1-\alpha \right)R+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2}-y{R}_{V} > 0\), \(F{\prime} (z)|(z=1) < 0\), \(F{\prime} (z)|(z=0) > 0\). In this case, \(z=1\) is villagers’ evolutionary stable strategy. (3) When \(x\lambda {A}_{V}+y\left(1-\alpha \right)R+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2}-y{R}_{V} < 0\), \(F{\prime} (z)|(z=1) > 0\), \(F{\prime} (z)|(yz=0) < 0\). In this case, \(z=0\) is villagers’ evolutionary stable strategy.

Stability analysis

Under conditions of information asymmetry, the evolutionary stable strategy is necessarily a pure strategy. Letting \(F\left(x\right)=F\left(y\right)=F\left(z\right)=0\), eight pure strategy equilibrium points are obtained: E1 = (0,0,0), E2 = (1,0,0), E3 = (0,1,0), E4 = (0,0,1), E5 = (1,1,0), E6 = (0,1,1), E7 = (1,0,1), E8 = (1,1,1). According to Lyapunov’s stability theory, a local equilibrium point satisfies the condition of asymptotic stability if and only if all eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are negative. Therefore, based on the replicator dynamics equation, the Jacobian matrix is constructed, its eigenvalues are determined, and the evolutionary stability trend among local governments, village collectives, and villagers is analyzed.

Substituting each equilibrium solution into the Jacobian matrix yields the corresponding eigenvalues, as shown in Table3.

Currently, digital rural governance in China is in an early stage, with government-led governance still being the main model(Ren, 2023). The government-led model primarily involves top-down resource integration, specifically through the establishment of government information service platforms to achieve “precise governance and refined management,” thereby improving government administrative efficiency. Digital technologies such as big data enable the integration of regional administrative resources, significantly enhancing public service capabilities (Feng, 2020; Kosec and Wantchekon, 2020). To implement the digital rural strategy, local governments actively promote related policies and provide incentives. However, the current progress of digital governance in China is slow, mainly due to the following reasons:

On the one hand, according to the theory of organizational inertia, organizations tend to maintain the status quo and adopt a conservative attitude toward change (Kelly and Amburgey, 1991). Village collectives have long relied on traditional rural governance models. Familiarity with traditional governance, the lag in adapting to the digital environment, and the investment costs are all factors that may lead village collectives to reject digital governance. On the other hand, according to the technology acceptance model, villagers’ acceptance of digital technology is mainly determined by two factors: perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness (Marangunić and Granić, 2015). Due to the continuous outflow of young talent, rural hollowing and aging are becoming more severe. Insufficient digital literacy among villagers makes it difficult for them to master digital technologies, preventing them from benefiting from the “digital dividend” and thus making them reluctant to participate in digital governance.

Based on the above description, this paper assumes the following scenario:

Scenario 1: When \(\lambda {A}_{O}+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2} < 0\) and \(\lambda {A}_{V}+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2} < 0\), meaning that government subsidies and the “cost-reduction effect” brought by digital technology cannot compensate for the costs of transforming the traditional governance model, neither village collectives nor villagers will participate in digital governance. In this case, (1,0,0) is the evolutionary stable strategy of the game system.

Constrained by the digital literacy of stakeholders, village collectives and villagers find it difficult to experience the “digital dividend” objectively and are unwilling to participate in digital governance subjectively. As a result, the government-led governance model fails to achieve the expected outcomes. To improve the current situation, the central government has been strengthening the promotion of digital policies and introducing related policies to guide talent resources into rural areas. Under the background of rural revitalization, rural elites, leveraging their resource and technological advantages, improve villagers’ digital literacy through policy education, digital training, and other means, thereby encouraging villagers to participate in digital rural governance. With government support, when both village collectives and villagers actively participate in digital governance, on the one hand, higher governance efficiency can be achieved at lower costs, bringing considerable synergy benefits to both parties as well as government subsidies. On the other hand, collaborative governance by village collectives and villagers generates economic benefits for local governments, which in turn supports digital rural governance, enhancing the visibility and social status of local governments and achieving a “win-win-win” situation. Based on the above description, this paper assumes the following scenario:

Scenario 2: When \(\beta {C}_{g}-\lambda {A}_{O}-\lambda {A}_{V} > 0\), \(\lambda {A}_{O}+\alpha R+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2}-{R}_{O} > 0\), and \(\lambda {A}_{V}+\left(1-\alpha \right)R+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2}-{R}_{V} > 0\) i.e., for village collectives and villagers, when the policy rewards, synergy benefits, and the “cost-reduction effect” of digital governance exceed their respective traditional governance costs and speculative gains, all three stakeholders will participate in digital governance. In this case, (1,1,1) is the evolutionary stable strategy of the game system.

Numerical simulation

The stability analysis describes two scenarios: evolutionary stable points (1,0,0) and (1,1,1). According to the analysis in Section 3.5, government subsidies and the participation of both village collectives and villagers in digital governance is the ideal state for digital rural governance. Therefore, this paper mainly discusses scenario (1,1,1) to analyze the impact of important parameter changes on the evolutionary results of the three parties. Since local governments need to respond to the national call for digital rural governance, their willingness to participate is relatively high, while village collectives and villagers have no significant preference for digital rural governance. Thus, the initial values of the three stakeholders are set to (0.5,0.3,0.3).

The data source and parameter calibration in this paper are primarily based on the following principles, and the assignments of key parameters are shown in Table 4:

Research cases. Zhejiang Province, as the only pilot zone for digital rural development in China, embarked on digitalization relatively early. It has encountered both challenges and successes, offering valuable insights for the digital transformation of other regions. Therefore, we selected three relatively successful pilot areas for digital rural development—Pingyang County, Wencheng County, and Cangnan County—as the basis for our research. We conducted surveys among local farmers, focusing primarily on their benefits and costs of participating in digital rural governance. Based on the survey data, we further assign values to farmers’ digital benefits, governance costs, and learning costs under certain constraints.

Policy documents. We have systematically reviewed the government reports related to rural governance including Digital Rural Development Work Priorities for 2024, Notice on Launching the Second Batch of National Digital Village Pilot Programs, Notice on the Allocation of 2024 Central Government Subsidy Funds for Supporting Rural Revitalization through Coordinated Efforts, Notice of the General Office of the People’s Government of Zhejiang Province on Issuing the Twenty Support Policies for Rural Revitalization and other reports. Based on this, the initial values of subsidy and cost parameter are set following the principles below: on the one hand, the value setting follows the conditions in Scenarios 2. On the other hand, when ESS changes, the change in variable values is kept as small as possible to avoid disproportionate numbers, facilitating subsequent sensitivity analysis of parameters.

Expert opinions. For data that are difficult to obtain, we consulted 10 senior experts in the field of rural governance from universities, research institutions, and government departments. The relevant parameters were determined by summarizing expert opinions and calculating the average value to ensure the scientific validity and reliability of the research data.

This paper uses system dynamics for numerical simulation. System dynamics is a simulation method that combines qualitative and quantitative analysis, emphasizing perspectives of development, connections, and motion. It is often used to simulate complex system structures and analyze their dynamic change trends (Forrester, 1987). This paper constructs a system dynamics model of the evolutionary game involving local governments, village collectives, and villagers using Vensim PLE. The system flowchart is shown in Fig. 4. The initial model conditions are set as follows: \({INITIAL\; TIME}=0,{FINAL\; TIME}=10,{TIME\; STEP}=0.25,{Units\; for\; Time}=Y{ear}\).

The impact of government subsidies on system evolution

Government subsidies can effectively cover the governance costs of village collectives and alleviate the economic pressure. This paper expands the benchmark assignment of \({A}_{O}\) by [100%,180%], setting its values to 2,2.4,2.8,3.2,3.6, respectively. Keeping other parameters unchanged, the simulation results are shown in Fig. 5.

According to Fig. 5a, as government subsidies increase, the willingness of local governments to support digital governance decreases, and there even emerges a tendency towards “no subsidy”. The possible reason lies in that high subsidy policies require corresponding financial support, but at this stage, rural infrastructure construction occupies the majority of expenditures in rural public finance, making it difficult for existing financial resources to sustain the costs incurred by high subsidy policies in the long term (Ding, 2007). At the same time, long-term high subsidies may lead to “welfare dependence” among village collectives, reducing their motivation and ability for independent development(Gottschalk and Moffitt, 1994). On the other hand, the economic benefits brought by digital governance may not be significant in the short term. Meanwhile, the social benefits of digital governance, such as enhancing governance transparency, improving the quality and efficiency of public services, often possess non-exclusivity and non-competitiveness characteristics and are regarded as public goods. Therefore, these benefits are difficult to directly convert into current economic gains, making it impossible to promptly offset the high costs of incentive strategies.

According to Fig. 5b, c, increasing subsidies to village collectives can directly enhance their willingness to participate in digital governance and, to a certain extent, promote villagers’ participation as well. The reason is that when the willingness of village collectives to engage in governance increases, they are more likely to receive government subsidies, which in turn provides them with more capital for policy promotion and guiding villagers to participate in digital governance. Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province, has leveraged government financial support to develop a public-private partnership model for digital rural governance. This convenient and efficient governance platform has boosted the enthusiasm of grassroots party organizations, fully leveraging their leading role in rural governance. It has enabled real-time monitoring, dynamic analysis, and precise decision-making in village-level governance.

Government subsidies are a crucial factor influencing villagers’ behavioral decisions and motivating their enthusiasm for governance (Li, 2016). This paper expands the benchmark assignment of \({A}_{V}\) by \([100 \% ,180 \% ]\), setting its values to 1,1.2,1.4,1.6,1.8, respectively. Keeping other parameters unchanged, the simulation results are shown in Fig. 6.

According to Fig. 6c, increasing subsidies to villagers helps to enhance their willingness to participate. The city of Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, China, has carried out a pilot project for rural areas under the “Azalea Plan”. By introducing blockchain technology to establish a reward mechanism, villagers are provided with corresponding material rewards and policy preferences. This has enhanced villagers’ sense of happiness and fulfillment, and effectively stimulated villagers for rural governance. According to Fig. 6a, b, increasing \({A}_{V}\) has no significant impact on the strategic choices of local governments and village collectives. On the one hand, due to the relatively low cost of \({A}_{V}\), increasing \({A}_{V}\) has a certain inhibitory effect on local governments’ willingness to subsidize, but the inhibition is not significant. For village collectives, an increase in villagers’ willingness to participate helps reduce the cost of village governance and, to a certain extent, enhances the village collectives’ willingness for digital governance. However, the promotional effect is not obvious, indicating that the strategic choices of village collectives are more dependent on government guidance.

When both \({A}_{O}\) and \({A}_{V}\) are simultaneously adjusted within the range of \(\left[100 \% ,180 \% \right]\), the simulation results are presented in Fig. 7. Increasing both \({A}_{O}\) and \({A}_{V}\) can further promote the participation of village collectives and villagers in governance. However, a heavier financial burden may reduce local governments’ willingness to support, potentially leading to a situation of “no subsidies” in the later stages. The key to achieving digital transformation in rural governance lies in ensuring the governance effectiveness of village collectives and villagers even under scenarios of low or absent government subsidies.

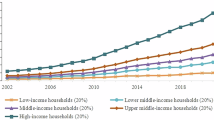

The impact of digital literacy on system evolution

Digital literacy is related to individuals’ cognitive level, learning ability, and operational skills, serving as the endogenous driving force for their engagement in rural governance (Shangguan, 2024). The range of digital literacy is [0,1]. In order to explore under what conditions digital literacy can enable the system to reach its most ideal state, this paper assigns corresponding values to it within the range with a step size of \(0.2\), i.e., setting λ = 0.1,0.3,0.5,0.7,0.9, while keeping other parameters constant. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8a, when \(\lambda \le 0.3\), local governments’ strategic choices evolve towards “1”, and the smaller \(\lambda\) is, the lower local governments’ financial burden becomes, and the faster the evolution speed is. When \(\lambda > 0.3\), as financial burden increases, their willingness to subsidize begins to decline; when \(\lambda \ge 0.7\), local governments choose the “no subsidy” strategy. As illustrated by Fig. 8b, c, when \(\lambda =0.1\), neither village collectives nor the villagers’ strategic evolution can reach a stable state within the simulation period. This indicates that when digital literacy is low, the agents find it difficult to recognize the “digital dividends” and are more inclined to choose more familiar traditional governance models (Zimmerman, 1990). Under such conditions, even if local governments provide external incentives, it is often difficult to achieve the desired effects due to the lack of endogenous motivation among the agents. When \(\lambda > 0.1\), subsidy policies can guide the game choices of village collectives and villagers to evolve toward dominant strategies. And within a certain limit, the larger \(\lambda\) is, the faster the evolution speed will be, which means that enhancing digital literacy contributes to promoting digital rural governance.

Comparing the two scenarios of \(\lambda =0.7\) and \(\lambda =0.9\), the latter exhibits a faster evolution speed in the early stages but slows down in the later stages. The possible reason is that when \(\lambda =0.9\), local governments choose the “no subsidy” strategy earlier due to greater financial pressure, resulting in insufficient funding support in the later stages. However, due to higher digital literacy, village collectives and villagers participate in digital rural governance with endogenous motivation. This provides the possibility to explore how to promote digital rural governance in scenarios where government subsidies are withdrawn.

The impact of government subsidies on system evolution moderated by digital literacy

Elite theory holds that elites are a small, dominant group that always plays a leading role. Similarly, in the field of rural governance, a few elites occupy a dominant position within the public power structure and lead the operational process of rural governance (Lu, 2009). Ordinary villagers face practical difficulties such as limited information access, low levels of organization, and insufficient economic resources, which lead to a lack of endogenous motivation to participate in digital rural governance (Su, 2022). Rural elites with good digital literacy leverage their own resources and technological advantages to enhance villagers’ digital literacy through policy promotion, digital education, and other forms, thereby playing an important leading and exemplary role.

As analyzed above, subsidy policies serve as an important tool to incentivize village collectives and villagers to participate in digital governance, but long-term subsidies also pose a significant financial burden on local governments. In scenarios where government subsidies are reduced or even absent in the later stages, how to stimulate the endogenous motivation of villagers is crucial for ensuring the digital rural governance. Based on this, this section sets three scenarios with λ = 0.1,0.3,0.5, representing low, medium, and high digital literacy, respectively. Additionally, the subsidy parameters are scaled within the range of \([-50 \% ,50 \% ]\), specifically with AO = 1,1.5,2,2.5,3 and AV = 0.5,0.75,1,1.25,1.5. The simulation results are shown in Figs. 9–11.

As can be seen from Fig. 9, when the digital literacy of village collectives and villagers is low, increasing subsidies helps evolve the game choices of both parties toward dominant strategies, but it fails to reach a stable state. This indicates that relying solely on exogenous policy incentives cannot achieve good governance outcomes. When \(\lambda =0.3\), increasing subsidies helps the game choices of village collectives and villagers stabilize more quickly towards the dominant strategy. However, high-level subsidies can impose financial pressure on local governments, leading to a tendency to adopt a “no subsidy” strategy. When \(\lambda =0.5\), due to financial pressure, local governments choose the “no subsidy” strategy in the middle to later stages. However, because the villagers have high digital literacy and possess certain endogenous motivation, providing lower subsidies can still achieve good governance effects.

Take Yucun Village in Anji County, Zhejiang Province, China, as an example. During the construction of the “Future Village” initiative, local residents actively participated in village affairs management, environmental evaluation, and public oversight by using digital platforms such as “Zheliban.” This led to the development of a relatively comprehensive system of digitally enabled collaborative governance. Despite the absence of systematic government subsidies, villagers were able to shift from passive acceptance to active participation in governance by continuously improving their digital literacy. Similar situations can be observed in international cases as well. For instance, under the “Digital India” initiative, rural women in Rajasthan have acquired basic digital skills through training programs and have voluntarily engaged in community information management and public services without relying on subsidies, becoming a driving force in local governance. In Kenya, some farmers have taught themselves to use platforms such as iCow and M-Farm for agricultural decision-making and collaboration, significantly enhancing community governance capacity and information transparency.

On the whole, as digital literacy increases, the willingness of village collectives and villagers for governance also rises. From the local governments’ perspective, compared to directly increasing subsidies, formulating policies to attract elites into rural areas to enhance digital literacy can not only reduce the dependency of village collectives and villagers on subsidies but also facilitate more reasonable resource allocation, thereby promoting the sustainable development of digital rural governance.

Discussion

There are significant differences in the human capital levels of rural residents, degree of fiscal decentralization, and the degree of local government attention to rural governance across different provinces or counties in China. And this regional heterogeneity has a substantial impact on the promotion of digital technology, the effectiveness of government subsidies, and the pathways for enhancing residents’ digital literacy. Therefore, in the process of advancing rural digital governance, it is essential to consider local conditions and explore differentiated, tiered policy implementation pathways.

In the relatively less developed central and western or remote areas, residents generally have lower educational levels, and their ability to independently improve digital literacy in the short term is limited. In these regions, the government should play a “starter” role by leading digital infrastructure development through fiscal subsidies, along with basic digital skills training. It should also establish intermediary mechanisms, such as digital service personnel and rural grid workers to help villagers connect with digital governance platforms. At this stage, subsidies are not only rewards for users but also a basic provision of the digital environment. In the more developed eastern regions with higher human capital and more active economies, residents have a stronger ability to receive digital information and are more willing to participate in governance. In these areas, governance transformation is more influenced by incentive mechanisms and collaborative systems. To improve the sustainability of digital rural governance, policy design should moderately reduce subsidies and focus on refining digital literacy, optimizing participation mechanisms, and co-creating and sharing platform governance rules, thereby stimulating residents’ endogenous motivation for continued participation through empowerment-based governance. Moreover, the differences in local government attention to governance and fiscal autonomy also significantly affect policy implementation outcomes. In counties or districts that are highly dependent on fiscal transfers, governments may lack the willingness or capacity to drive digital governance transformation. In such cases, a “central special funds guidance + performance evaluation linkage” mechanism could be considered to enhance their enthusiasm. In contrast, in developed counties with strong governance enthusiasm and fiscal autonomy, they could be allowed to explore more regionally distinctive “digital rural experimental zones” models, engaging in diversified explorations in areas such as subsidy methods, platform construction, and data management.

Although this paper focuses on the digital transformation of rural governance in China, the findings are also relevant from an international perspective. In fact, digital technology is widely regarded as an important tool for solving rural governance challenges. In this process, both government subsidies and digital literacy have been reflected in policy practices across various countries, playing different roles.

From the experience of developing countries, government subsidies, as an external incentive mechanism, are often used to promote infrastructure development, information platform construction, and initial technology adoption in rural areas. For example, in Sri Lanka’s “Smart Villages” initiative, government funding supported the construction of rural ICT centers and the integration of digital service outsourcing platforms, enabling local residents to initially access and use digital technologies. This model achieved significant success in its early stages, but after subsidies gradually phased out, some villages experienced a decline in platform usage and a loss of management personnel, highlighting the sustainability limitations of relying solely on fiscal incentives in promoting digital governance. Meanwhile, some countries focus more on building endogenous momentum by enhancing residents’ digital literacy. For instance, in Nigeria’s “Digital Community Program,” multiple rural areas have collaborated with cooperatives, religious groups, and local NGOs to carry out grassroots digital education and mobile skills training. Despite extremely limited government financial support, trained residents have significantly increased their usage of digital tools for agricultural management, community oversight, and public services. Additionally, self-organized digital collaboration platforms have gradually formed. In the rural governance practices of developed countries, the importance of digital literacy is even more pronounced. For example, in Finland and Estonia’s digitalization of rural public services, the focus has been on improving citizens’ information literacy and administrative transparency, which has helped foster trust in digital platforms and increased residents’ willingness to use them.

In summary, achieving the digital transformation of rural governance should emphasize the coordination between external incentives and internal capabilities. This will help avoid the risks of path dependence and project dependency in digital reforms, while simultaneously enhancing digital literacy through diverse methods.

Conclusions and policy implications

Conclusions

This study develops an evolutionary game model grounded in bounded rationality to examine the strategic interactions and dynamic evolution among governments, village collectives, and villagers in the context of digital transformation in rural governance. A system dynamics approach is further employed to conduct numerical simulations and validate the model’s implications. The key findings are as follows:

First, through replicator dynamic analysis, this study identified two possible evolutionarily stable strategies, (1,0,0) and (1,1,1). When the constraints \(\beta {C}_{g}-\lambda {A}_{O}-\lambda {A}_{V} > 0,\lambda {A}_{O}+\alpha R+\beta {C}_{O1}-{C}_{O2}-{R}_{O} > 0,\lambda {A}_{V}+\left(1-\alpha \right)R+\beta {C}_{V1}-{C}_{V2}-{R}_{V} > 0\) are met, the system evolves to the optimal stable equilibrium of (1,1,1).

Second, the study elucidates the key factors influencing the digital transformation of rural governance by capturing the strategic interdependencies among stakeholders. Government subsidies emerge as a critical external driver that positively influences the strategic choices of village collectives and villagers. However, excessive subsidies may impose fiscal burdens on the government, potentially prompting it to scale back or even withdraw support to contain costs.

Third, digital literacy functions as an essential internal driver that significantly strengthens the willingness of village collectives and villagers to engage in digital governance. Even in the face of reduced or absent government subsidies, higher levels of digital literacy among villagers can still enable the realization of effective governance.

Policy implications

The digital rural governance not only relies on external incentives but also relies heavily on endogenous digital literacy. Based on the research findings, we propose the following suggestions:

Firstly, categorized guidance tailored to regional differences is an important prerequisite for digital rural governance. Considering the varying resource environments, social locations, and differentiated digital literacy among villagers in different regions, targeted and operable digital transformation plans should be formulated to fully leverage regional resource and location advantages, thereby facilitating the stable realization of digital rural governance.

Secondly, subsidies should be scientifically formulated, leveraging the efficiency and traceability of digital platforms to regularly review and assess the implementation effects of policies, and promptly adjust according to regional economic development and actual outcomes. Local governments can introduce diversified funding sources by encouraging and guiding enterprises and social capital to participate in digital rural governance. This not only provides financial support but also alleviates local governments’ financial pressure and promotes rational allocation of funds.

Thirdly, local governments should focus on enhancing villagers’ digital literacy to foster endogenous impetus for digital rural governance. On the one hand, digital skills training should be strengthened in rural areas by regularly dispatching professionals for on-site guidance and offering personalized courses tailored to villagers of different ages, education levels, and occupational backgrounds. Meanwhile, leveraging the widespread use of smartphones, mobile learning models should be promoted to enhance farmers’ digital capabilities and application initiatives. On the other hand, it is necessary to accelerate the cultivation of leading talents and innovation teams in the field of digital rural development, improve the evaluation system and incentive policies for agricultural digital talents, and promote talent flow to rural areas.

Future research directions

The theoretical contribution of this study lies in the development of a multi-agent game framework that systematically examines the key factors influencing digital rural governance. From a practical perspective, the simulation results offer viable pathways toward achieving collaborative governance among governments, village collectives, and villagers, while also providing targeted policy recommendations. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the analysis is primarily grounded in evolutionary game theory, without incorporating alternative theoretical perspectives such as behavioral economics, complex systems theory, or institutional analysis. Future research could adopt a more interdisciplinary approach to better capture the complexity of real-world decision-making processes. Second, to simplify the model, this study adopts a static subsidy mechanism, which may not fully reflect the dynamic nature of policy implementation. Future work could explore dynamic subsidy schemes to enhance the model’s adaptability. Third, the evolutionary game model requires more precise and context-specific data to accurately predict stakeholder behavior. Although the parameters in this study are informed by relevant policies and existing literature, some degree of subjectivity remains. Future research could improve the model’s robustness by incorporating additional variables, case studies, or empirical testing.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bing (2023) From “Digital Embedding” to “Digital Inclusion”: reflection on the way of digital transformation of rural governance. J Nanchang Univ (Humanities Soc Sci) 5(54):93–103

Cao (2020) The practical logic of village-level party building leading rural governance in the new era. Probe 01:109–120

China Digital Rural Development Report (2022). Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Available via DIALOG. https://www.cac.gov.cn/2023-03/01/c_1679309718486615.htm. Accessed 1 March 2023

Ding (2007) Theory and practice of public finance coverage in rural areas. J Manag World 10:1–7

Du (2020) Technology dispels autonomy: study on the dilemma of village governance after technology involvement. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 03(20):62–68

Feng (2020) Digitization of rural governance: current status, demands, and countermeasures research. E-Gov 06:73–85

Forrester JW (1987) Lessons from system dynamics modeling. Syst Dyn Rev 2(3):136–149

Galdeano‐Gómez E, Aznar‐Sánchez JA, Pérez‐Mesa JC (2011) The complexity of theories on rural development in Europe: An analysis of the paradigmatic case of Almería (South‐east Spain). Sociologia Ruralis 1(51):54–78

Gottschalk P, Moffitt RA (1994) Welfare dependence: concepts, measures, and trends. Am Econ Rev 2(84):38–42

H Xie, W Wang and X Zhang (2018). Evolutionary game and simulation of management strategies of fallow cultivated land: a case study in Hunan province, China. Land Use Policy 71:86–97

Jiang (2021) Research on the promotion of modernization in rural governance system through digital technology. E-Gov 07:72–79

K Kosec and L Wantchekon (2020). Can information improve rural governance and service delivery? World Development (125): 104376

Kelly D, Amburgey TL (1991) Organizational inertia and momentum: a dynamic model of strategic change. Acad Manag J 3(34):591–612

L Kiser and E Ostrom (1982).The three worlds of action: a metatheoretical synthesis of institutional approaches in strategies of political inquiry. Strategies Polit Inquiry 13:179–222

Li (2016) Evaluation of the effects of agricultural subsidy policies: incentive effects and wealth effects. Chin Rural Econ 12:17–32

Li (2022) How can digital empowerment promote rural self-governance? Case analysis based on the “Azalea” plan. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 03(22):65–74

Li (2023) From “Scattered” to “Integrated”: advancing the organization of farmers in the comprehensive promotion of rural revitalization. Seeker 05:167–174

Liao (2023) Digital rural construction driven by “Data Governance”: functions, scenarios, and paths. Reform 12:113–127

Lu (2009) Inheritance and innovation of rural elite governance. Zhejiang Soc Sci 02:34–36

Lu (2023) Aging of rural labor force in the context of rura! revitalization: development trends, mechanism analysis, and response paths. J China Agric Univ (Soc Sci) 04(40):5–21

Lv (2020).Rural governance participation and stability analysis of village elite based on evolutionary game theory. issues in agricultural economy 4:111–123

M Xiao, S Luo and S Yang (2024).Synergizing technology and tradition: a pathway to intelligent village governance and sustainable rural development. journal of the knowledge economy 16:1768–1823

Meng (2021) Elements, mechanisms and approaches towards digital transformation of government: the dual drivers from technical empowerment to the state and society. Gov Stud 01(37):5–14

Mergel I, Edelmann N, Haug N (2019) Defining digital transformation: results from expert interviews. Gov Inf Q 4(36):101385

N Marangunić and A Granić (2015).Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univ Access Inf Soc 14:81–95

Pavan E (2014) Embedding digital communications within collective action networks: a multidimensional network approach. Mobilization Int Q 4(19):441–455

R. T. o. P. University (2020) Platform-driven digital government: capabilities, transformation, and modernization. E-Gov 07:2–30

Ren Y (2023) Rural China staggering towards the digital era: evolution and restructuring. Land 7(12):1416

Salemink K, Strijker D, Bosworth G (2017) Rural development in the digital age: a systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J Rural Stud 54:360–371

Shangguan W, Caiping Q, Lingyan Y(2024) Whether digital literacy promote farmers’ participation in rural governance or not: analysis of the mediating role based on subjective socio-economic status and sense of political efficacy J Hunan Agric Univ (Soc Sci) 01(25):54–63

Shen (2020) Rural technology empowerment: strategic choice for effective rural governance. J Nanjing Agric Univ(Soc Sci Ed) 2(20):1–12

Su (2022) Farmers’ digital literacy, elite identity and participation in rural digital governance. J Agrotech Econ 01:34–50

Sun (2020) The decline and reconstruction of village communities: “VillagersDiscussion on Rural Matters Of Common Interest” in Xiangshan County of Zhejiang Province as an example. China Rural Surv 01:17–28

Tang (2022) Digital technology drives high-quality development of agriculture and rural areas: theoretical interpretation and practical path. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 02(22):1–9

Wang (2021) Institutional analysis and theoretical insights of urban grassroots governance innovation: a case study of Beijing’s “Immediate Response to Complaints”. E-Gov 11:2–11

Wang Y, Li X(2022) Institutional analysis and theoretical enlightenment for the impact of digital technology on rural governance Chin Rural Econ 08:132–144

Yang (2021) On the tension between rural digital empowerment and digital divide and its resolution. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 05(21):31–40

Yin S, Li Y, Chen X, Yamaka W, Liu J (2024) Collaborative digital governance for sustainable rural development in China: An evolutionary game approach. Agriculture 9(14):1535

Zhao D, Ding Y(2021) On digitalization promoting rural revitalization: its mechanism, path and counter measures J Hunan Univ Sci Technol 6(24):112–120

Zheng Y, Mei L, Chen W (2024) Does government policy matter in the digital transformation of farmers’ cooperatives?—A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Front Sustain Food Syst 8:1398319

Zhou (2020) A study on the mechanism of village collective economic organizations in the revitalization of rural industries: take the “Enterprise+Village Collective Economic Organization+Farmers” model as an example. Issues Agric Econ 11:16–24

Zimmerman MA (1990) Taking aim on empowerment research: on the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. Am J Commun Psychol 18(1):169–177

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (21ASH009). Throughout the entire process of data collection, research design, result analysis, and paper writing, all intellectual creative activities were independently completed by the authors without the use of any generative AI tools.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yangyang Zheng performed data analysis, drawing all the legends and tables. Yangyang Zheng and Feng Liao wrote the main manuscript text. Di Yang and Feng Liao conceptualized, reviewed, and edited the article, and provided financial support. Feng Liao supervised and verified the article. Yangyang Zheng and Di Yang revised the paper according to the reviewers’ comments and responded.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Business School of Wenzhou University on 18 May 2024(approval number: WZU20240518003). This study is part of a more extensive study on the digital transformation of agriculture and rural areas. Ethical approval covers all aspects of the research, including questionnaire surveys and in-depth interviews, data analysis, and the publication of research findings. This committee reported on the appropriateness of the procedure followed for the study and all research procedures were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

The informed consent statement was obtained on 18 May, 2024. Before the survey, researchers read out the informed consent statement to the participants orally and all participants received comprehensive information detailing the study’s aims and objectives. Anonymity was rigorously guaranteed to ensure that all collected data would be used solely for academic research purposes and that participation involved no foreseeable risks or ethical compromises. In addition, participants were clearly advised before their engagement that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they possessed the unequivocal right to withdraw from the survey at any point without consequence or prejudice. The researchers would inform the participants that submitting the questionnaire would be considered as their consent. The questionnaires submitted by the villagers are regarded as a record and evidence of their informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, F., Zheng, Y. & Yang, D. Digital transformation in rural governance: unraveling the micro-mechanisms and the role of government subsidies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1423 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05716-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05716-9