Abstract

Social robots are increasingly used to support children’s cognitive, emotional, and social development, yet systematic research on overarching themes remains limited. This study addresses the gap with a bibliometric analysis of 5688 publications (2013–2023), leveraging Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, and Tableau. Results show a steady increase in publications, with a notable rise in the last decade due to advancements in AI and robotics. Key research areas identified include robotics education, human-robot interaction, STEM education, and the use of robots for children with disabilities. Emerging trends focus on preschool education, inclusivity, and classroom teaching. Four themes, including motor, niche, emerging/disappearing, and basic, highlight creativity development and AI integration as under-researched. The U.S. leads geographically, followed by China and Europe, revealing disparities between regions. These findings underscore the need for greater global collaboration to better integrate social robots into child development and therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social robots are autonomous or semi-autonomous artificial agents with human-like or animal-like characteristics. They engage in social interactions with humans through speech, gestures, or facial expressions, influencing their cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social development (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b; Feil-Seifer and Matarić, 2011). Research has shown that social robots can enhance cognitive and emotional abilities and satisfy psychological needs in specific tasks (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b; Lee and Lee, 2022). Social robots come in various forms. For example, based on physical appearance, they can be categorized as humanoid, mechanistic, or cartoon-like (Wang et al., 2023). In terms of physical form, they are either virtual or embodied. Virtual social robots are presented on devices like laptops, tablets, and smartphones, while embodied robots exist in the physical world, equipped with sensors such as cameras, microphones, and touch sensors. These allow them to perceive their surroundings, move, and interact with objects, thereby better understanding and responding to human needs and blending naturally into social interactions (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b).

With rapid advancements in robotics and artificial intelligence (AI), social robots have increasingly been integrated into educational settings, especially for child development (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b; Neumann, 2023). This is largely because children tend to form strong emotional bonds with social robots, as they are more open to such technology, often attributing human-like emotions to them (Neumann, 2023). As a result, children are more likely to be influenced by social robots than adults (Vollmer et al., 2018). Younger children may even believe that social robots possess life-like qualities, such as the ability to eat or grow (Neumann, 2023).

Due to their human-like traits, social robots often take on roles such as companions, assistants, or tutors, providing emotional support and helping children with academic learning (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b; Toh et al., 2016). Specifically, social robots have been increasingly adopted to support both typically developing learners and students with diverse needs. In mainstream learning settings, social robots have been used to enhance engagement, promote collaborative learning, and support STEM education through interactive, hands-on activities (Chaidi et al., 2021; Coufal, 2022). At the same time, social robots have shown significant promise in supporting children with learning disabilities and developmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), by providing consistent, nonjudgmental interactions that can help improve communication, social skills, and emotional regulation (Armstrong and Huh, 2021; Fortunati and Edwards, 2024). The integration of robots into educational and therapeutic settings reflects broader societal shifts in how technology is used to mediate human development and inclusion. Overall, from 2013 to 2023, research on the application of social robots in child development has made significant strides, covering areas such as cognitive development, emotional support, and social skills enhancement. This has provided valuable insights into the potential and applications of social robots for child development, laying the groundwork for further innovations in education.

However, there is still a lack of systematic reviews of research practices across countries, which limits our understanding of the latest developments and evolving trends in this field. Though Zhang et al. (2023) attempted to map research patterns in this area, their study was constrained by a small sample size of only 517 publications. This limitation arose from a narrow selection of keywords (e.g., using only “child*” to identify studies related to children), resulting in an incomplete representation of the research trajectory of social robots for child development. To address this gap, we conduct a comprehensive bibliometric analysis using Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, and Tableau, expanding the scope of literature to uncover global research trends in this field by incorporating a broader range of synonyms for both children and social robots. This quantitative approach offers several advantages (Hallinger and Kovačević, 2019; Mukherjee et al., 2022): (a) By reviewing a large volume of literature, it provides an overview of research practices across countries, helping to identify research hotspots, commonalities, and differences in the use of social robots for child development, thus deepening our understanding of the field’s development. (b) It tracks the evolution of research themes, examining keywords, citation patterns, and publication volume to reveal shifts and growth in various research topics related to social robots. (c) By comparing publication output and research priorities across countries, we can gain insights into different nations’ research directions and preferences regarding the use of social robots in child development.

This study offers a systematic review of global research practices, providing a thorough understanding of the trends and dynamics in this field. It will assist researchers and developers in identifying the frontiers and emerging areas of interest in social robots for child development. Additionally, this study highlights the research preferences and priorities of different countries, fostering deeper international collaboration and shared research priorities, ultimately driving innovation and further development in this growing field.

Research design

The data in this study was collected from the Web of Science (WOS) database, encompassing journal articles, conference proceedings, and online publications. Information such as titles, years, abstracts, keywords, authors, institutions, and regions were extracted and analyzed using three key tools: Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, and Tableau. Bibliometrix, an R-based software (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017), provides a range of bibliometric indicators, such as keyword co-occurrence, co-citation analysis, collaboration networks, and topic analysis. VOSviewer is designed for visualizing collaboration networks and creating thematic maps to explore relationships between publications and research structures. Tableau was employed for geographic distribution mapping, enabling the visualization and analysis of data by region. Together, these tools offer a comprehensive, multi-dimensional view of global research trends, collaboration networks, and thematic developments in the field of social robots for child development.

The study focuses on data from 2013 to 2023, a period selected due to significant breakthroughs in AI and machine learning, such as the widespread adoption of deep learning and advances in affective computing and human-computer interaction (Bengio, 2013; Ramakrishnan and El Emary, 2013). These technological innovations have provided a robust foundation for the development of social robots, allowing them to engage more naturally with humans. The bibliometric analysis addresses three key research questions:

RQ1: What has been the overall trend in research on social robots for child development from 2013 to 2023?

RQ2: What are the research hotspots and trends in this field?

RQ3: What are the characteristics of collaboration among research institutions and countries worldwide in this field?

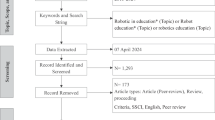

Data collection

The WOS database was selected as the data source, which indexes titles, abstracts, keywords, and full texts across multiple disciplines. While Scopus indexes a larger number of journals, WOS is often favored by researchers across various disciplines due to its precision, comprehensive citation data, and focus on high-impact journals (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). The following search parameters were used:

-

Topic: (“companion robot*“ OR “social robot*“ OR “sociable robot*“ OR “socially assistive robot*“) AND (adolescent* OR child* OR student* OR kid* OR pupil*) AND (educat* OR learn* OR teach*).

-

Time range: January 1, 2013—December 31, 2023.

-

Language: English only.

-

Document types: Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, early access, and book chapters.

The articles were selected based on the following criteria: (a) The research must focus on aspects of child development, such as cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social skills, excluding studies solely related to the design of robotics technology. (b) The research should cover either typically developing children or those with special needs, excluding applications of social robots in higher education or adult learning. (c) The social robots studied must demonstrate capabilities for expression and emotion sensing, enabling meaningful communication with children through social cues such as speech, gestures, movements, and eye contact. In the end, after multiple rounds of searching and filtering, 5688 valid papers were selected for analysis.

To ensure data accuracy and consistency, the following procedures were applied during the initial data cleaning phase and throughout the analysis process: (a) Merging variations of author and institution names where discrepancies were detected; (b) Unifying synonymous or closely related keywords to avoid fragmentation in co-occurrence networks; (c) Manually reviewing and correcting typographical errors in high-frequency entries; (d) Removing non-standard records and ensuring only peer-reviewed and indexed materials were included.

Data analysis

The data for 5688 articles (see the Supplement File for the raw data) were exported from WOS in bibtex, txt, and excel formats and processed using Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, and Tableau. Bibliometrix was used to generate word clouds, keyword growth charts, high-frequency keyword age charts, and thematic evolution graphs to uncover trending research topics. VOSviewer primarily analyzed co-citation maps, co-occurrence networks of author-defined keyword, and collaboration networks between institutions and countries. Tableau helped visualize the geographic distribution of publications, offering insights into the research output disparity between developed and developing nations and between Eastern and Western countries.

Summary of the included data

Table 1 shows that conference proceedings dominate the research output (55.61%), reflecting the rapid publication of new findings in this fast-evolving field. The average publication age of 4.99 years indicates a relatively recent body of research. The field also has a high rate of international collaboration due to its interdisciplinary nature and global relevance, promoting innovation and knowledge sharing. However, the relatively low number of single-authored papers (456) suggests that the complexity of the research often requires collaboration across different fields, including robotics, education, psychology, and engineering.

Research results

This section presents the findings of the bibliometric analysis in three key areas: (a) Publication trends in research on social robots for child development; (b) Research hotspots and trends in this field; (c) Collaboration patterns among institutions and countries.

Publication trends in research on social robots for child development

Publication trends were examined through annual publication counts, geographical distribution of publications, source journals, and citation data to answer RQ1.

Annual publication volume

Figure 1 shows the annual number of publications and citations from 2013 to 2023. The purple bars represent publication counts, while the dark purple line indicates citation frequency. Overall, research in this field has shown a clear upward trend, with two distinct phases: a rapid development period from 2013 to 2019 and a steady growth period from 2020 to 2023. Notably, the number of publications surged significantly after 2016, reaching a peak in 2020. Although publication numbers dipped slightly in 2021 and 2022, they remained in a growth phase. Citation frequency has consistently increased from 2013 to 2023, indicating rising academic interest in this area.

Top 10 countries by publication count

Table 2 presents the top 10 countries contributing the most publications in the field. It is important to note that countries were determined by the corresponding authors’ affiliations in the included publications. To visualize the geographical distribution, the data from Table 2 was imported into Tableau to create Fig. 2. The United States lead with 1162 publications, accounting for 20.4% of the total, followed by China with 522 publications (9.2%), and Spain with 373 publications (6.5%). Japan and Italy rounded out the top five with 243 and 232 publications, respectively. The data in Table 2 highlight a significant imbalance in research output, with developed countries (N = 2689) far surpassing developing countries like China and Brazil (N = 691 combined). Western countries (N = 2622) have produced far more research than Eastern countries (China and Japan, N = 765), emphasizing the gap in research between regions.

Top 10 countries by citation count

Table 3 ranks the top 10 countries by total and average citations. The U.S. remains the most cited, with 14,919 total citations and an average of 12.8 citations per article, followed by China (3575 total citations, 6.8 average), Spain (2801 total citations, 7.5 average), and the UK (2686 total citations, 12.9 average). Interestingly, while Switzerland did not appear in the top 10 countries by publication count, its research has significant global influence, as it ranked in the top 10 for citations. Conversely, Japan, which ranked fourth in publication count, dropped to tenth in citation ranking, and Brazil, despite ranking eighth in publication count, did not appear in the top 10 for citations.

Distribution of publications by journal (2013–2023)

Figure 3a illustrates the distribution of articles by journal. The International Journal of Social Robotics ranked first, focusing on topics such as the use of social robots in language, mathematics, and science education (e.g., Belpaeme et al., 2018b; Chandra et al., 2020). Education and Information Technologies followed, covering various educational applications of social robots (e.g., Ekström and Pareto, 2022; Shahab et al., 2022). Frontiers in Robotics and AI ranked third, addressing a wide range of robotics and AI-related topics (e.g., Ali et al., 2021; Clabaugh et al., 2019). IEEE Transactions on Education ranked fourth, featuring research on social robots in school curricula, programming education, and STEM (e.g., Laut et al., 2014; Shim et al., 2016).

Figure 3b shows that most articles fall under educational research (N = 11362) and robotics (N = 1275), followed by electrical engineering (N = 1023) and science disciplines (N = 1003). Despite the diverse fields, the common goal across these domains is to explore the educational, entertainment, and therapeutic potential of social robots. For example, social robots have shown significant educational value as early learning aids, helping children with language acquisition, basic math, and cognitive skills (e.g., Toh et al., 2016). They also support programming and STEM education (e.g., Xia and Zhong, 2018). Additionally, social robots provide interactive entertainment and emotional support for children (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b) and therapeutic benefits, particularly for children with autism, by improving social skills, facial expression recognition, and emotional communication (Clabaugh et al., 2019; Rudovic et al., 2018).

Top 10 publications by citation count

In addition to the publication count, citation frequency is a key indicator of an article’s academic impact (Hallinger and Kovačević, 2019). Scholars in the field tend to cite articles that are highly relevant to their own research, so the citation count of an article reflects its importance to some extent (Zupic and Čater, 2015). This study examines local citations, which refer to how often an article has been cited by the publications included in this specific literature review (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017).

Table 4 lists the top 10 most locally cited articles in the field. These studies focus primarily on how social robots affect children’s cognitive development, learning outcomes, and engagement, especially in early childhood (e.g., Di Lieto et al., 2017; Fridin, 2014) and elementary education (e.g., Baxter et al., 2017). Many of the most cited studies explore how social robots can foster computational thinking and support STEM education (e.g., Atmatzidou and Demetriadis, 2016; Angeli and Valanides, 2020; Bers et al., 2014). A smaller number of studies focus on language learning (Fridin, 2014) and cognitive development (Di Lieto et al., 2017), while few address teacher professional development (Kim et al., 2015). Overall, these articles highlight the potential of social robots to foster computational thinking, enhance STEM education, and offer engaging, personalized learning experiences for students.

Research hotspots and trends in this field

This section analyzes the research hotspot and emerging trends in the field of social robots for child development. Using word cloud visualizations, keyword co-occurrence networks, temporal keyword analysis, and thematic mapping, we seek to address RQ2.

Word cloud analysis

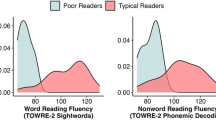

Figure 4 presents a word cloud of the top 25 author-defined keywords, which is an essential tool for visualizing research trends in social robots for child development. The size of each keyword indicates its frequency, with larger words representing higher usage and greater relevance to the field. The most frequent term is “Robotics Education” (N = 855), followed by “STEM Education” (N = 579), “Educational Robots” (N = 554), “Human-Robot Interaction” (N = 398), “Computational Thinking” (N = 316), and “Programming” (N = 299). These terms collectively point to a concentrated focus on how social robots engage with children to promote cognitive, social, and computational skills. Terms such as “Robotics Education” and “Human-Robot Interaction” highlight the growing role of social robots in classrooms. “Robotics Education” often utilizes robots as platforms for hands-on STEM learning that fosters creativity and technical proficiency (Ali et al., 2021; Angeli and Valanides, 2020), while “Human-Robot Interaction” in education emphasizes engaging students effectively and enhancing their learning experiences through carefully crafted interactions (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b). Unlike traditional educational tools such as tablets or coding software, social robots combine physical embodiment, interactivity, and relational capabilities, making them uniquely positioned to support cognitive, social, and emotional development (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b). Together, these fields demonstrate why social robots are increasingly seen as essential tools for educational reform (Chen et al., 2023), possessing interdisciplinary potential across various subjects.

Co-occurrence network of author-defined keywords

Figure 5 illustrates the co-occurrence network of author-defined keywords, a method highlighted by Law and Whittaker (1992) as reflective of a field’s core themes. In the VOSviewer software, we first selected “co-occurrence” and then “author-defined keywords” to generate the VOSviewer map, which contains a total of 9244 keywords. We conducted a manual harmonization process to merge synonymous or closely related terms under unified labels. Below are several examples of the standardization we applied:

-

“autism” and “autism spectrum disorder” → autism spectrum disorders

-

“human robot interaction” and “child-robot interaction” → human-robot interaction

-

“k-12,” “elementary education” → k-12 education

-

“humanoid robot” → humanoid robots

-

“coding,” “visual programming,” “raspberry pi,” “robot programming” → programming

-

“stem,” “computer science,” “engineering,” “mathematics” → stem education

This normalization step helped eliminate redundancy and increased the semantic clarity of the keyword co-occurrence network. By doing so, we aimed to enhance the reliability and validity of our bibliometric visualization and ensure that key research themes are represented more cohesively.

To identify the meaningful clusters of keywords, we undertook an iterative and reflective process involving multiple trials, interpretation cycles, and consultation of relevant literature. Eventually, we set the keyword frequency threshold to 22, resulting in 37 key terms. The larger the circular node, the more frequently the keyword appears, and the more it represents a hot topic in the field. The lines between nodes represent the strength of the association; the thicker the line, the more often the two keywords appear together in the same article. Four distinct clusters are identified with different colors.

Cluster 1 centers on themes related to robotics education and learning, with key terms such as Robotics Education, STEM Education, Project-Based Learning, and Educational Innovation. Social robots are revolutionizing how children engage with STEM education by offering hands-on, problem-based learning experiences (Coufal, 2022). Tools like LEGO Mindstorms allow children to design, build, and program robots, boosting creativity and enhancing STEM concepts. As a part of educational innovation, social robots also address Industry 4.0 demands, preparing students with the technical and collaborative skills required for future careers.

Cluster 2 focuses on human-robot interaction and therapy for children with disabilities. The following keywords are covered, including Human-Robot Interaction, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Special Education, Cerebral Palsy, Artificial Intelligence, Humanoid Robots, Reinforcement Learning, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning. Human-robot interaction technology is being used to support child development, particularly for children with disabilities. Social robots have shown promise in providing targeted assistance to children with autism, offering potential benefits in several areas. Research suggests that social robots can effectively help children with autism spectrum disorders improve social, language, and behavioral skills (Armstrong and Huh, 2021). Moreover, social robots contribute to postural education for children with autism, where collaboration between humanoid robots and therapists offers valuable insights into their motor development and body awareness (Palestra et al., 2014). However, it is important to note that while children with autism often show strong interest in social robots, they may struggle to understand the robots’ mental states during interactions (Zhang et al., 2019). This challenge should be considered when designing robot-based interventions aimed at improving social behaviors in children with autism.

Cluster 3 centers on programming education and the development of computational thinking, with key themes such as Computational Thinking, Programming, K-12 Education, Assessment, Collaborative Learning, and Early Childhood Education. Social robots play an important role in child development by fostering computational thinking and programming skills, particularly in K-12 education (Angeli and Valanides, 2020). These robots provide hands-on, interactive experiences where children learn to break down problems and think algorithmically. Moreover, social robots facilitate collaborative learning by engaging children in tasks that require teamwork, such as problem-solving activities, where the robot acts as a mediator or facilitator. These robots help children share ideas, communicate, and work together to achieve goals, enhancing both their cognitive and social skills (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b; Lee and Lee, 2022).

Cluster 4 focuses on add-on technologies for social robots, including topics such as 3D Printing, Arduino, Augmented Reality (AR), Educational Technology, and Virtual Reality (VR). These technologies play a crucial role in enhancing the design, functionality, and educational applications of social robots for child development. Over the past decade, the advancements in robotics technology have been remarkable. For instance, an interdisciplinary vision (such as STEM subjects) and technological tools (like Arduino) have greatly enhanced the development of students’ thinking and abilities. Arduino, as hardware technology supporting social robots, has been widely used in elementary education (García-Tudela and Marín-Marín, 2023). The integration of 3D printing technology with robotics can assist in the learning of STEM-related content (Jdeed et al., 2020).

Temporal evolution of high-frequency keywords

Keywords provide a concise summary of a paper’s content, and high-frequency keywords in a research field can reveal the foundational topics, research hotspots, and trends. Figure 6 shows the evolution of high-frequency keywords in research on social robots for child development over time. The size of each circle represents the frequency of the keyword, while the lines indicate the time span during which the keyword was actively used in research. The minimum frequency is set at five, with three key terms highlighted each year to represent significant topics. As seen in Fig. 6, between 2013 and 2023, terms like Robotics Education, Computational Thinking, and STEM appear most frequently, which aligns with both the word cloud (Fig. 4) and the co-occurrence network of author-defined keywords (Fig. 5).

In terms of time span, keywords like Embedded Systems (2014–2021), Teamwork (2015–2020), Mobile Robots (2013–2018), and Cerebral Palsy (2015–2021) remained relevant for over 6 years. More recent research trends from the last three years include Preschool, Inclusive Education, and Improving Classroom Teaching.

Specifically, the Embedded Systems learning approach (2014–2021) integrates hardware resources and open-source code to combine robotics and embedded systems, supporting project-based learning. For example, the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay’s e-Yantra project holds annual large-scale online robotics competitions, using these systems to teach embedded systems and robotics concepts through project-based learning (Panwar et al., 2020). Teamwork (2015–2020) is a critical skill fostered in STEM education. Studies like those by Menekse et al. (2017) show a strong correlation between teamwork quality and team performance in robotics competitions, with effective collaboration significantly enhancing students’ ability to create high-quality engineering solutions.

Mobile Robots (2013–2018) are robots capable of movement in a physical environment and are powerful tools for studying child development and pediatric rehabilitation. A key factor in establishing meaningful and sustained interaction with children is a robot’s mobility. For instance, Köse et al. (2015) explored how humanoid robots facilitated learning through interactive sign language games with children who had communication disorders. Cerebral Palsy (2015–2021) is another area where early intervention using robots has shown significant benefits. Research (e.g., Buitrago et al., 2020) suggests that humanoid social robots can aid in the treatment of children with motor disabilities.

Preschool (2019–2023) has gained increased attention in recent years. Social robots can support parents by offering social, educational, entertainment, and counseling functions for preschoolers (Lee et al., 2022). Moreover, these robots assist young children in learning STEM subjects and coding, fostering an early interest in technology (Dorouka et al., 2020). Inclusive Education (2020–2023) focuses on providing equal access to quality education for all students, including those with diverse abilities. For instance, Esfandbod et al. (2024) demonstrated how a new social robot, APO, helped hearing-impaired individuals improve their lip-reading skills through educational games. Finally, Improving Classroom Teaching (2020–2023) refers to the use of social robots as teaching assistants to enhance classroom interaction. Al Hakim et al. (2022) found that middle school students showed increased motivation, engagement, and academic performance when learning English through interactive lessons with a robot.

Thematic map of research focus

Figure 7 presents a thematic map based on the clustering and interconnections of author-defined keywords (Agbo et al., 2021). The horizontal axis represents centrality, which shows the strength of relationships between clusters, while the vertical axis represents density, indicating the internal coherence of a cluster (Nájera-Sánchez et al., 2020). The size of the thematic bubbles indicates the frequency of the respective theme, and four quadrants host 13 thematic bubbles.

(1) Motor themes (high centrality, high density) represent well-established and important research topics with strong connections to other themes. This quadrant includes topics such as STEM Education, Programming, Human-Robot Interaction, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Arduino. These motor themes align with the four clusters from the keyword co-occurrence network (Fig. 5), which feature robotics education, human-robot interaction, programming education, and computational thinking. Human-Robot Interaction, Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Engagement, and Reinforcement Learning appear at the intersection of both motor and basic themes, suggesting they are foundational and central topics in social robot research.

(2) Niche themes (high density, low centrality) are specialized topics that, while well-developed, are more narrowly focused within the field of social robots for child development. This quadrant includes Control Education and Cerebral Palsy. For example, Filippov et al. (2017) explored how to simplify control engineering concepts for elementary students through engineering projects. Social robots are also used in the treatment of cerebral palsy, as demonstrated by Fridin and Belokopytov (2014), who found that children with cerebral palsy showed higher levels of interaction with robots than typically developing children, suggesting that robot-assisted movement therapy may encourage these children’s physical activity.

(3) Emerging or disappearing themes (low density, low centrality) reflect topics that may be either newly emerging or phasing out. This quadrant includes themes such as E-learning, Educational Innovation, Constructivism, Creativity, VR, and AR. While E-learning might be a fading topic, others like Virtual and Augmented Reality are on the rise. The combination of VR/AR technologies with robotics has been shown to promote cognitive development and reasoning in typical children (Chiu, 2021), as well as support children with autism and intellectual disabilities by encouraging expression, physical activity, and social interaction (Roberts-Yates and Silvera-Tawil, 2019).

(4) Basic themes (high centrality, low density) are crucial but under-researched topics that require further development. This quadrant includes themes such as Creativity and Artificial Intelligence. For example, Ali et al. (2021) found that social robots could serve as agents of creativity for children. AI technology can empower robots in supporting precision education (Chen et al., 2023).

Collaboration patterns among institutions and countries

This section addresses RQ3 on the characteristics of collaboration between institutions and countries.

Top 10 institutions conducting research on social robots for child development

The analysis using VOSviewer identified 4512 institutions involved in research related to social robots for child development. After setting a minimum publication threshold of 28 papers, 19 institutions met the criteria, forming 108 links across five clusters, with a total link strength of 710. As shown in Fig. 8 and Table 5, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) emerged as the most influential institution, leading in both publication volume and citation impact, followed by Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Universidade de Lisboa, Tecnológico de Monterrey, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, and Carnegie Mellon University. MIT, located at the center of the network, has extensive collaborations with numerous universities, underscoring its critical role in research on the application of social robots in child development. Notably, EPFL and Universidade de Lisboa are also major contributors and display close collaborative ties, reflecting a significant partnership in this research area.

It is important to note that the differences observed between the top publishing and cited countries (“Top 10 countries by publication count” and “Top 10 countries by citation count”) and the top contributing institutions (Top 10 institutions conducting research on social robots for child development) are not contradictions but reflect differences in analytical granularity. Country-level data aggregate outputs from all institutions within a nation, which explains why countries like China rank highly due to their large number of contributing institutions. In contrast, the institution-level analysis highlights individual universities or research centers with sustained contributions in the field. The absence of Chinese institutions in the Top 10 list likely indicates a more distributed research landscape, where no single institution dominates in publication volume.

Analysis of regional collaboration networks

The analysis of regional collaborations revealed 25 countries/regions in the network, grouped into four clusters, with a total link strength of 1184. As shown in Fig. 9, the US stood out with collaborative relationships in 24 regions, particularly strong with China, Japan, the UK, Spain, and Italy, indicating its leadership in this field. Spain maintained partnerships with 16 countries, with notable collaborations with the US, China, Japan, and the UK. The UK collaborated with 22 countries, most notably with the US, China, Japan, and Italy. Israel, as a smaller node in the network, has key partnerships with the US, representing an additional cluster of collaboration.

Discussion

This study used bibliometric analysis to examine 5688 articles published between 2013 and 2023 on the use of social robots for child development, aiming to answer the following three questions:

(RQ1) What has been the overall trend in research on social robots for child development from 2013 to 2023?

Both the number of publications and citations showed a continuous upward trend between 2013 and 2023. Conference papers account for more than half of the total, primarily because of the relatively high efficiency of conference paper publication, which can meet the rapid development demands of robotics technology (Kanero et al., 2022). Regarding the geographic distribution of publications, there remains a significant gap between Eastern and Western countries and between developed and developing regions. Developed countries far outnumber developing countries in terms of publications, with Western countries producing significantly more research than Eastern countries. The number of citations is generally proportional to the number of publications by country.

From a disciplinary perspective, research on social robots in child development represents a cross-disciplinary effort between educational research and robotics, focusing on how social robots influence children’s learning and development in school or home environments (Lee and Lee, 2022). Another area of interest is how social robots, acting as caregivers, impact the growth and development of children with special needs (Zhang et al., 2019). In terms of highly cited articles, the top ten studies focus primarily on the impact of social robots on children’s cognitive development, learning outcomes, and student engagement, particularly in early childhood and elementary education.

Overall, research on social robots in child development has seen steady growth over the past decade. Several factors may contribute to this trend: First, as technology advances, AI and robotics have become focal points, and social robots have garnered increasing interest from scholars and researchers (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b). Second, social robots have significant potential applications in child development, such as in education, entertainment, and mental health. As awareness in these fields deepens, research on the role of social robots in child development is expected to increase (Lee and Lee, 2022). Third, the study of social robots often involves multiple disciplines, such as computer science, psychology, and education. Interdisciplinary collaboration fosters deeper and more innovative research, attracting scholars from diverse fields to this area of study. And fourth, as AI technologies become more widely applied in society, their impact on children’s development has also attracted broader social attention. Governments, schools, and families are increasingly interested in how social robots affect child development, driving further research in this area.

(RQ2) What are the research hotspots and trends in this field?

The co-occurrence network of author-defined keywords presents four clusters of research, including (a) robotics education and learning, (b) human-robot interaction and therapy for children with disabilities, (c) programming education and computational thinking, and (d) add-on technologies for social robots. This finding demonstrates the multifaceted role social robots play in supporting child development. In STEM education, social robots offer interactive, hands-on experiences that nurture critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Bers et al., 2014). For children with special needs, especially those with autism, social robots provide personalized, supportive interactions that promote social and communication development, making them valuable in therapeutic contexts (Cabibihan et al., 2013). In programming education, social robots help children build computational thinking by offering real-time feedback during coding tasks, enhancing engagement (Grover and Pea, 2013). Technological innovations, particularly in AI and machine learning, continue to improve the personalization and adaptability of these robots, increasing their effectiveness in both educational and therapeutic settings (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b). These research areas highlight the broad potential of social robots in fostering child development across multiple domains.

Based on the temporal analysis of high-frequency keywords, the emerging key research topics of the past three years include Preschool, Inclusive Education, and Improving Classroom Teaching. These keywords highlight how social robots are leveraged to support child development, particularly in early education environments. In preschool settings, social robots offer interactive, age-appropriate learning experiences that promote early cognitive, social, and emotional growth through playful activities, while also fostering foundational skills such as language and motor coordination (Bers et al., 2014). In the context of inclusive education, social robots provide personalized, non-judgmental interactions, making them especially beneficial for children with disabilities, by helping them develop social and communication skills in a supportive learning environment (Cabibihan et al., 2013). Additionally, social robots are increasingly being used to enhance classroom teaching by serving as co-teachers or teaching assistants, enabling more engaging lessons, particularly in STEM education, and offering personalized feedback to improve student learning outcomes (Benitti, 2012). These keywords underscore the potential of social robots to create more interactive, inclusive, and effective educational environments for all children.

According to the keyword cloud analysis and the thematic evolution graph, social robots have long been recognized for their role in making STEM education more accessible and engaging, providing hands-on experience in programming, and offering valuable interaction support for children with disabilities, improving social and communication skills (Cabibihan et al., 2013; Benitti, 2012). However, there is a notable shift in recent years towards topics related to creativity and AI, indicating an evolving perspective on the role of social robots. Beyond supporting technical skills, social robots are now being examined for their potential to stimulate imaginative play, creative problem-solving, and critical thinking—skills essential for holistic development in an AI-driven world (Lee and Lee, 2022; Neumann, 2023). This expanding focus suggests that social robots are seen not only as tools for STEM and special education but also as facilitators of broader, more dynamic learning experiences that prepare children for future challenges in an AI-rich environment (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b).

(RQ3) What are the characteristics of collaboration among research institutions and countries worldwide in this field?

MIT dominates the central position in the research of social robots for child development, along with significant contributors such as EPFL, Universidade de Lisboa, and other institutions. MIT’s extensive collaborations suggest that it is at the forefront of developing innovative applications of social robots in child development. The geographic analysis also shows that the US plays a central role, fostering cross-regional collaboration that helps expand the global impact of social robot research. Regional partnerships, especially among leading nations like the US, the UK, China, and Spain, highlight the importance of international cooperation in advancing the role of social robots in education and therapy for children, a trend also supported by recent literature on the global nature of educational technology research (Belpaeme et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Contribution and implications

This study makes several important contributions to advancing the field of social robots in child development. First, it underscores the critical role of social robots in enabling personalized and engaging learning experiences for children. By adapting to individual learners’ needs, interests, and abilities, social robots support cognitive, social, and emotional growth. Their effectiveness is especially notable in domains such as STEM education, computational thinking, and second language acquisition, where they foster creativity, problem-solving, and sustained engagement.

Second, the paper highlights the promising use of social robots in inclusive education. For children with special needs, such as those with autism or developmental challenges, interacting with socially responsive robots can help enhance communication skills, motor coordination, and social interaction, making social robots a powerful assistive tool in both therapeutic and educational settings.

Third, this study contributes methodologically by conducting a large-scale bibliometric analysis that systematically maps the knowledge structure and evolution of this growing field. By analyzing 5688 peer-reviewed publications, the study offers a comprehensive, data-driven overview of research trends, thematic developments, and collaboration networks over time. Together, these findings not only deepen our understanding of the current research landscape but also provide a valuable foundation for guiding future inquiry, practice, and policy in the integration of social robots into diverse educational and developmental contexts.

The findings of this study have important implications for future research, educational practice, and the design of social robots in child development. First, social robots serve as powerful tools for fostering computational thinking and problem-solving skills, particularly within programming and STEM education. By offering interactive, hands-on experiences, these robots can help make abstract concepts, such as algorithms, logic, and coding, more accessible and engaging for young learners (Burleson et al., 2017). Future robot design could also integrate adaptive learning technologies, enabling robots to tailor instruction and difficulty levels based on individual learner performance. Leveraging AI, these systems could track developmental progress in real time, adjusting their interactions to provide personalized feedback and support (Chen et al., 2023). Moreover, AI-enabled affective computing capabilities could allow robots to detect emotional cues like frustration or confusion and respond with empathetic and encouraging feedback, strengthening not only cognitive outcomes but also emotional engagement in learning.

Second, the research landscape remains heavily skewed toward institutions in developed countries. This concentration highlights an urgent need for more inclusive, international collaborations that bring in underrepresented regions. Such partnerships are critical for ensuring the global relevance of social robot technologies, as diverse cultural, educational, and socioeconomic contexts offer valuable insights into how these tools can be adapted and applied effectively worldwide.

Third, in early childhood education, social robots have shown promise in supporting cognitive, emotional, and social development through playful interactions. Young children are especially receptive to learning experiences that blend fun and education, and well-designed robots, which incorporate storytelling, language development, and emotional support, can be powerful companions during these foundational years (Shahid et al., 2014).

Fourth, social robots have demonstrated strong potential in therapeutic and special education contexts, particularly for children with autism and other developmental challenges. As use cases expand, optimizing human-robot interactions to address diverse learner needs is essential. Design considerations should focus on sustaining engagement and minimizing frustration, which are two critical factors in maintaining the effectiveness of therapeutic or educational interventions.

Finally, while the benefits of social robots are compelling, their potential drawbacks must not be overlooked. For instance, overdependence on robots could reduce opportunities for authentic human interaction, potentially affecting children’s emotional and social development (Sharkey, 2016). Ethical concerns also arise around data privacy, emotional safety, and the responsible use of these technologies with vulnerable populations. It is imperative for researchers and designers to prioritize ethical safeguards, ensuring that these tools enhance rather than replace essential human relationships and that they are deployed in ways that protect the autonomy, dignity, and well-being of the children they aim to support (Formosa, 2021).

Limitations and future research

The findings of this study should be interpretated with caution. First, this study primarily relied on the WOS database, which, although comprehensive, might miss relevant studies published in other databases or non-English languages. Future research could expand by incorporating additional databases and considering non-English publications to offer a more complete global perspective on the field.

Second, this study may have a geographical bias, with most research concentrated in developed countries such as the US, the UK, and Western Europe. This creates a skewed understanding of the field. Future research should aim for a more balanced geographical analysis by including research from developing countries, thereby exploring the unique challenges and opportunities for social robot integration in those contexts.

Third, the dominance of conference papers, which make up over half of the dataset, may affect the depth of insights derived. Conference papers often emphasize emerging trends but may lack the thorough and detailed methodologies of journal articles. Future research is suggested to prioritize including more peer-reviewed journal articles to provide more rigor and depth to the analysis.

Data availability

The data for this study were extracted from the Web of Science database and have been included in the Supplementary File.

References

Agbo FJ, Oyelere SS, Suhonen J, Tukiainen M (2021) Scientific production and thematic breakthroughs in smart learning environments: a bibliometric analysis. Smart Learn Environ 8(1):1–25

Al Hakim VG, Yang SH, Liyanawatta M, Wang JH, Chen GD (2022) Robots in situated learning classrooms with immediate feedback mechanisms to improve students’ learning performance. Comput Educ 182:104483

Ali S, Devasia N, Park HW, Breazeal C (2021) Social robots as creativity eliciting agents. Front Robot AI 8:673730

Angeli C, Valanides N (2020) Developing young children’s computational thinking with educational robotics: An interaction effect between gender and scaffolding strategy. Comput Hum Behav 105:105954

Aria M, Cuccurullo C (2017) Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr 11(4):959–975

Armstrong L, Huh Y (2021) Longing to connect: could social robots improve social bonding, attachment, and communication among children with autism and their parents? In: 13th International Conference on Social Robotics. Springer International Publishing, Singapore, p 650–659

Atmatzidou S, Demetriadis S (2016) Advancing students’ computational thinking skills through educational robotics: a study on age and gender relevant differences. Robot Auton Syst 75:661–670

Baxter P, Ashurst E, Read R, Kennedy J, Belpaeme T (2017) Robot education peers in a situated primary school study: Personalisation promotes child learning. PLoS ONE 12(5):e0178126

Belpaeme T, Kennedy J, Ramachandran A, Scassellati B, Tanaka F (2018a) Social robots for education: a review. Sci Robot 3(21):eaat5954

Belpaeme T, Vogt P, Van den Berghe R, Bergmann K, Göksun T, De Haas M, Pandey AK (2018b) Guidelines for designing social robots as second language tutors. Int J Soc Robot 10:325–341

Bengio Y (2013) Deep learning of representations: looking forward. In: International conference on statistical language and speech processing. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp 1–37

Benitti FBV (2012) Exploring the educational potential of robotics in schools: a systematic review. Comput Educ 58(3):978–988

Bers MU, Flannery L, Kazakoff ER, Sullivan A (2014) Computational thinking and tinkering: exploration of an early childhood robotics curriculum. Comput Educ 72:145–157

Buitrago JA, Bolaños AM, Caicedo Bravo E (2020) A motor learning therapeutic intervention for a child with cerebral palsy through a social assistive robot. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 15(3):357–362

Burleson WS, Harlow DB, Nilsen KJ, Perlin K, Freed N, Jensen CN, Muldner K (2017) Active learning environments with robotic tangibles: Children’s physical and virtual spatial programming experiences. IEEE Trans Learn Technol 11(1):96–106

Cabibihan JJ, Javed H, Ang M, Aljunied SM (2013) Why robots? A survey on the roles and benefits of social robots in the therapy of children with autism. Int J Soc Robot 5:593–618

Chaidi E, Kefalis C, Papagerasimou Y, Drigas A (2021) Educational robotics in primary education. a case in Greece. Res Soc Dev 10(9):e17110916371–e17110916371

Chandra S, Dillenbourg P, Paiva A (2020) Children teach handwriting to a social robot with different learning competencies. Int J Soc Robot 12:721–748

Chen X, Cheng G, Zou D, Zhong B, Xie H (2023) Artificial intelligent robots for precision education. Educ Technol Soc 26(1):171–186

Chiu WK (2021) Pedagogy of emerging technologies in chemical education during the era of digitalization and artificial intelligence: Aa systematic review. Educ Sci 11(11):709

Clabaugh C, Mahajan K, Jain S, Pakkar R, Becerra D, Shi Z, Matarić M (2019) Long-term personalization of an in-home socially assistive robot for children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Robot AI 6:110

Coufal P (2022) Project-based STEM learning using educational robotics as the development of student problem-solving competence. Mathematics 10(23):4618

Di Lieto MC, Inguaggiato E, Castro E, Cecchi F, Cioni G, Dell’Omo M, Dario P (2017) Educational robotics intervention on executive functions in preschool children: a pilot study. Comput Hum Behav 71:16–23

Dorouka P, Papadakis S, Kalogiannakis M (2020) Tablets and apps for promoting robotics, mathematics, STEM education and literacy in early childhood education. Int J Mob Learn Organ 14(2):255–274

Eguchi A (2016) RoboCupJunior for promoting STEM education, 21st century skills, and technological advancement through robotics competition. Robot Auton Syst 75:692–699

Ekström S, Pareto L (2022) The dual role of humanoid robots in education: as didactic tools and social actors. Educ Inf Technol 27(9):12609–12644

Esfandbod A, Nourbala A, Rokhi Z, Meghdari AF, Taheri A, Alemi M (2024) Design, manufacture, and acceptance evaluation of apo: a lip-syncing social robot developed for lip-reading training programs. Int J Soc Robot 16(6):1151–1165

Feil-Seifer D, Matarić MJ (2011) Socially assistive robotics. IEEE Robot Autom Mag 18(1):24–31

Filippov SA, Ten NG, Fradkov AL (2017) Teaching robotics in secondary school: examples and outcomes. IFAC-PapersOnLine 50(1):12167–12172

Formosa P (2021) Robot autonomy vs. human autonomy: social robots, artificial intelligence (AI), and the nature of autonomy. Minds Mach 31(4):595–616

Fortunati L, Edwards A (eds.) (2024) The De Gruyter handbook of robots in society and culture. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG

Fridin M (2014) Storytelling by a kindergarten social assistive robot: a tool for constructive learning in preschool education. Comput Educ 70:53–64

Fridin M, Belokopytov M (2014) Robotics agent coacher for CP motor function (RAC CP Fun). Robotica 32(8):1265–1279

García-Tudela PA, Marín-Marín JA (2023) Use of Arduino in primary education: a systematic review. Educ Sci 13(2):134

Grover S, Pea R (2013) Computational thinking in K–12: a review of the state of the field. Educ Res 42(1):38–43

Hallinger P, Kovačević J (2019) A bibliometric review of research on educational administration: science mapping the literature, 1960 to 2018. Rev Educ Res 89(3):335–369

Jdeed M, Schranz M, Elmenreich W (2020) A study using the low-cost swarm robotics platform Spiderino in education. Comput Educ Open 1:100017

Kanero J, Oranç C, Koşkulu S, Kumkale GT, Göksun T, Küntay AC (2022) Are tutor robots for everyone? The influence of attitudes, anxiety, and personality on robot-led language learning. Int J Soc Robot 14(2):297–312

Kim C, Kim D, Yuan J, Hill R. B, Doshi P, Thai C. N(2015) Robotics to promote elementary education pre-service teachers' STEM engagement, learning, and teaching Computers & Education 91:14–31

Köse H, Uluer P, Akalın N, Yorgancı R, Özkul A, Ince G (2015) The effect of embodiment in sign language tutoring with assistive humanoid robots. Int J Soc Robot 7:537–548

Laut J, Bartolini T, Porfiri M (2014) Bioinspiring an interest in STEM. IEEE Trans Educ 58(1):48–55

Law J, Whittaker J (1992) Mapping acidification research: a test of the co-word method. Scientometrics 23(3):417–461

Lee H, Lee JH (2022) The effects of robot-assisted language learning: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 35:100425

Lee J, Lee D, Lee JG (2022) Can robots help working parents with childcare? Optimizing childcare functions for different parenting characteristics. Int J Soc Robot 14(1):193–211

Leonard J, Buss A, Gamboa R, Mitchell M, Fashola OS, Hubert T, Almughyirah S (2016) Using robotics and game design to enhance children’s self-efficacy, STEM attitudes, and computational thinking skills. J Sci Educ Technol 25:860–876

Ioannou A, Makridou E(2018) Exploring the potentials of educational robotics in the development of computational thinking: A summary of current research and practical proposal for future work Educ Inf Technol 23(6):2531–2544

Menekse M, Higashi R, Schunn CD, Baehr E (2017) The role of robotics teams’ collaboration quality on team performance in a robotics tournament. J Eng Educ 106(4):564–584

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis Scientometrics 106(1):213–228

Mukherjee D, Lim WM, Kumar S, Donthu N (2022) Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J Bus Res 148:101–115

Nájera-Sánchez JJ, Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado M, Mora-Valentín EM (2020) Mapping value co-creation literature in the technology and innovation management field: a bibliographic coupling analysis. Front Psychol 11:588648

Neumann MM (2023) Bringing social robots to preschool: transformation or disruption? Child Educ 99(4):62–65

Palestra G, Bortone I, Cazzato D, Adamo F, Argentiero A, Agnello N, Distante C (2014) Social robots in postural education: a new approach to address body consciousness in ASD children. In: 6th International Conference on Social Robotics, Australia, Springer International Publishing, pp 290–299

Panwar A, Chauhan A, Arya K (2020) Analyzing learning outcomes for a massive online competition through a project-based learning engagement. In: 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON). Porto, Portugal, IEEE, pp 1246–1251

Ramakrishnan S, El Emary IM (2013) Speech emotion recognition approaches in human computer interaction. Telecommun Syst 52:1467–1478

Roberts-Yates C, Silvera-Tawil D (2019) Better education opportunities for students with autism and intellectual disabilities through digital technology. Int J Spec Educ 34(1):197–210

Rudovic O, Lee J, Dai M, Schuller B, Picard RW (2018) Personalized machine learning for robot perception of affect and engagement in autism therapy. Sci Robot 3(19):eaao6760

Shahab M, Taheri A, Mokhtari M, Shariati A, Heidari R, Meghdari A, Alemi M (2022) Utilizing social virtual reality robot (V2R) for music education to children with high-functioning autism. Educ Inform Technol 27:819–843

Shahid S, Krahmer E, Swerts M (2014) Child–robot interaction across cultures: How does playing a game with a social robot compare to playing a game alone or with a friend? Comput Hum Behav 40:86–100

Sharkey AJ (2016) Should we welcome robot teachers? Ethics Inf Technol 18:283–297

Shim J, Kwon D, Lee W (2016) The effects of a robot game environment on computer programming education for elementary school students. IEEE Trans Educ 60(2):164–172

Toh LPE, Causo A, Tzuo PW, Chen IM, Yeo SH (2016) A review on the use of robots in education and young children. J Educ Technol Soc 19(2):148–163

Vollmer AL, Read R, Trippas D, Belpaeme T (2018) Children conform, adults resist: a robot group induced peer pressure on normative social conformity. Sci Robot 3(21):eaat7111

Wang X, Liu Q, Pang H, Tan SC, Lei J, Wallace MP, Li L (2023) What matters in AI-supported learning: a study of human-AI interactions in language learning using cluster analysis and epistemic network analysis. Comput Educ 194:104703

Xia L, Zhong B (2018) A systematic review on teaching and learning robotics content knowledge in K-12. Comput Educ 127:267–282

Zhang Y, Song W, Tan Z, Zhu H, Wang Y, Lam CM, Yi L (2019) Could social robots facilitate children with autism spectrum disorders in learning distrust and deception? Comput Hum Behav 98:140–149

Zhang N, Xu J, Zhang X, Wang Y (2023) Social robots supporting children’s learning and development: bibliometric and visual analysis. Educ Inform Technol 29:12115–12142

Zupic I, Čater T (2015) Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ Res Methods 18(3):429–472

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023MF059). This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2023MF059) and Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Qingdao (No.QDSKL2401291). This work was also supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R579), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinghua Wang and Zaipeng Zhang: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing; and Yu Wang3: data curation, software, formal analysis, writing-original draft; Zhongmei Han: Conceptualization, writing-review and editing; Yu Wang5: resources, data curation, methodology; Ziyu Duan and Taghreed Ali Alsudais: methodology, writing-review editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not involve human participants or their data. Therefore, ethical approval is not applicable.

Informed consent

This study does not involve human participants or their data. Therefore, informed consent is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Han, Z. et al. Social robots for child development: research hotspots, topic modeling, and collaborations. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05752-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05752-5