Abstract

Household consumption has emerged as a key driver of economic growth in China. This study empirically investigates whether perceptions of livelihood risks constrain household consumption, utilizing data from the 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020 waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The results indicate that perceptions of livelihood risks significantly suppress household consumption, leading to both reduced consumption levels and a narrower consumption structure. A mechanism analysis reveals that perceptions of livelihood risks reduce consumption by eroding consumer confidence. Furthermore, households’ risk preferences and proactive government interventions serve as effective moderating factors, significantly mitigating the negative impact of perceptions of livelihood risks, thus offering supporting household consumption. This study contributes new evidence to the growing literature on the economic impacts of risk perceptions and offers valuable insights for policymakers seeking to enhance livelihood development and stimulate economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, international political tensions, and escalating trade protectionism has precipitated a structural contraction in the global trade system. In response, the Chinese government has accelerated the construction of a new development pattern characterized by “domestic circulation as the mainstay, and the mutual promotion of domestic and international circulations.” In this strategic transformation, activating residents’ consumption potential and expanding domestic demand have become the core engines of economic growth. Despite the government’s sustained efforts to implement consumption-stimulus policies, the latent consumption potential of Chinese households remains underutilized. Data shows that China’s final consumption expenditure contributes far less to GDP growth than that of developed countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany, as well as Asian countries like Japan and South Korea, and even trails emerging economies such as India and Brazil (Bai et al., 2012). Some scholars attribute China’s “high savings, low consumption” dilemma to factors such as liquidity constraints, precautionary savings, life cycle and income distribution (Modigliani and Cao, 2004). These theories explain the impact of persistent economic uncertainty on consumption but ignore the consequences of inadequate social security systems.

During this critical period of social transformation, China’s social security system remains fraught with shortcomings, exposing residents to a range of livelihood-related risks. For instance, sluggish healthcare reforms have led to costly and inaccessible medical care. The imbalanced allocation of educational resources has given rise to problems such as limited school choice and high tuition costs. The multi-track pension system has intensified intergenerational pressures on pension reserves. Moreover, shortages in eldercare and childcare services have sparked conflicts between family responsibilities and work, while speculative housing market trends have made homeownership increasingly unattainable. Structural adjustments in the labor market have increased employment instability. These challenges shape residents’ “risk perception-precautionary savings” mental accounts, thereby affecting their consumption decisions. People’s perception of livelihood risks (PPLR) is defined as the subjective judgment and expectation formed by residents, based on their personal living conditions and external environmental changes, about the potential economic pressures and uncertainties in key livelihood areas such as education, healthcare, housing, employment, and pensionsFootnote 1. Compared to the extreme, low-probability, high-damage events like earthquakes or terrorist attacks, livelihood risks are intrinsically linked to daily life, leading to a much stronger PPLR and a correspondingly greater impact on consumption behavior.

Scholars have revealed the multifaceted impact of livelihood risk perception on household consumption. Campos and Reggio (2015) analyzed households with employed primary earners, demonstrating that even the mere possibility of unemployment significantly reduces total household consumption expenditure. Harmenberg and Öberg (2021) differentiated consumption structures, finding that expectations of unemployment risk primarily drive declines in durable goods consumption, while actual unemployment more strongly affects non-durable goods consumption. Krueger et al. (2006) showed that the widening income disparity not only reduces total social consumption but also exacerbates consumption stratification through wealth distribution effects, leading to a vicious cycle of “wealth gap-consumption suppression.” Dong et al. (2017), Luo et al. (2004), studied the housing market, noting that rising housing prices had a non-linear effect on consumption: when price increases exceed affordability, housing assets shift from the “wealth effect” to the “crowding-out effect,” causing a significant contraction in household consumption expenditure. Luo (2004) analyzed urban residents in China, finding that unemployment risk, income volatility, and the uncertainty of medical and educational expenses all suppressed household consumption. Li and Wang (2023) focused on environmental quality, observing that air pollution prompts protective measures, which, while safeguarding health, limits consumption scenarios and capacity, leading to a significant reduction in total consumption. Huang et al. (2023) argued that stronger earthquake risk perception reduces spending, particularly on food, transportation, communication, and education/cultural entertainment, with information dissemination amplifying risk perception and driving consumption declines. Furthermore, factors such as liquidity constraints (Hayashi, 1985; Zeldes, 1989), mortgages (Fan and Yavas, 2020), digital finance (Chen et al., 2024; Song et al., 2024), household assets (Eika et al., 2020; Friend and Lieberman, 1975), and population age structure (Dynan et al., 2009; Han et al., 2022) significantly influence household consumption. However, various livelihood risks are not isolated; they are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Whether the comprehensive nature of perceived livelihood risk exerts a more pronounced suppressive effect on household consumption remains underexplored.

In summary, while existing research confirms that PPLR significantly suppresses household consumption, several limitations remain: (1) previous research typically employs macro-level proxy measures (e.g., unemployment rates, the Gini coefficient) to gauge PPLR; however, these metrics fail to capture the nuanced risk expectations that individuals hold regarding education, healthcare, pensions, and income inequality; (2) most studies focus on the impact of a single dimension of PPLR on consumption, overlooking the systemic complexity of livelihood service development. Imbalances within the system can give rise to a “barrel effect,” potentially skewing estimates; and (3) despite widespread recognition of the “reservoir effect” of savings on consumption, little research explores how PPLR, via modifications in psychological accounts, triggers reductions in consumption.

This paper, based on data from the 2014–2020 China Family Panel Studies, empirically analyzes the impact of PPLR on household consumption and elucidates its underlying mechanisms. The potential contributions of this study are as three-fold: (1) by constructing a comprehensive PPLR index through the entropy weight method and empirically testing its consumption-suppressing effect using micro-level resident survey data, this research offers a novel perspective and comprehensive evidence to explain China’s phenomenon of “high savings and low consumption”; (2) it uncovers the transmission pathways through which PPLR affects consumption behavior from three key perspectives: consumption confidence, risk preference, and government intervention; and (3) through the analysis of differences across various groups and regions, this paper confirms the “inverted effect” of risk and wealth distribution in the relationship between PPLR and household consumption. While lower social strata exhibit greater PPLR intensity, the suppressive effect of PPLR on consumption behavior remains relatively consistent across social strata. This finding lends strong support to the core proposition of risk society theory, particularly the idea of the “democratization of risk distribution.”

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

Theoretical basis

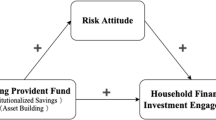

The precautionary savings theory reveals residents’ rational strategy to mitigate risks by increasing precautionary savings and reducing current consumption in response to potential income declines or expenditure surges (Leland, 1968; Deaton, 1991). This theory integrates elements such as risk perception, risk attitude, consumption confidence, and consumption behavior. Among these, risk perception exerts the most direct influence on consumption decisions. Preparing for uncertainties in future income and expenditure involves a cognitive assessment of potential risks. When residents choose to increase savings and reduce consumption, this reflects both a rational decision to maximize utility over time and a manifestation of declining consumption confidence and varying risk attitudes (Andersen et al., 2022). Typically, groups with lower consumption confidence exhibit more significant reductions in consumption under risk shocks (Mynaříková and Pošta, 2023). Risk perception is not isolated but is influenced by individual risk attitudes. Risk-tolerant individuals perceive potential risks less acutely, save less, and display more robust consumption behavior (Xie et al., 2022), while risk-averse individuals amplify risk perceptions, prioritizing precautionary savings and adopting more cautious consumption patterns (Giglio et al., 2021). Livelihood risks, rooted in public policies and economic cycles, surpass the coping capacity of individuals or households, so there is an urgent need for government intervention to distribute risks socially and address them at their source through institutional reforms and targeted measures. Therefore, this paper constructs a theoretical model of residents’ risk-perceived consumption decision-making, analyzing the correlation among risk perception, consumption confidence, risk attitude, government intervention and consumption behavior.

The direct impact of perceived livelihood risks on consumption

Empirical research indicates that, in anticipation of substantial fixed expenditures - such as those for education, medical care, and housing - households tend to adopt pronounced precautionary saving behaviors by dynamically adjusting their consumption budgets to achieve intertemporal smoothing (De Nardi, 2010; Morisset and Revoredo 1995; Chen et al., 2020). Furthermore, the direct threat of unemployment risks and anticipated income instability prompt households to curtail non-essential expenses (Stephens, 2004; Benito, 2006). In parallel, the widening income gap intensifies consumption segmentation (Aguiar and Bils, 2015), inhibiting consumption upgrading among low-income groups (Lee, 2022). It is important to recognize that risk comprises both objective threats and subjective perceptions (Hansson, 2010). Information asymmetry often magnifies risk perception, leading to anxiety and panic that drive overly cautious behavior, distorting consumption patterns (Huang, 2023). As PPLR escalates, households increasingly prioritize rigid budget for basic necessities - such as food, housing, and education (Li et al., 2020) - while cutting back on discretionary spending on luxury goods and entertainment services (Huang, 2023). In light of these observations, we propose Hypothesis 1:

H1: PPLR significantly suppresses household consumption.

The mechanism of perceived livelihood risks on consumption

Consumer confidence, as an affective dimension of PPLR, serves as a critical trigger for precautionary saving behavior. Widely recognized as a vital indicator of residents’ consumption propensity (Dees, 2013) and broader economic trends (Bovi, 2009), consumer confidence exhibits a well-documented positive correlation with consumption expenditure (Mynaříková and Pošta, 2023). Katona (1968) noted that optimistic sentiments stimulate spending, while increased pessimism promotes precautionary savings. Furthermore, amplified perception of risks and uncertainty intensifies fear and anxiety (Mi et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019), prompting an even more pessimistic outlook and overestimation of the potential adverse impacts of risk. As a result, when residents lose confidence in economic prospects, their PPLR increases significantly, giving rise to a “self-fulfilling pessimistic expectation.” Even absent an immediate economic crisis, apprehensions about future economic conditions drive households to increase precautionary savings, thereby curtailing immediate consumption (Brüggen et al.,2017;Hampson et al.,2021). Vanlaer et al. (2020) demonstrated that in the wake of the global financial crisis, declining consumer confidence significantly amplified household savings across 18 EU countries. On this basis, we propose Hypothesis 2.

H2: PPLR suppresses household consumption by undermining consumption confidence.

In consumption decision-making, risk attitude serves as a critical determinant of consumer behavior. Defined as the willingness of residents to accept risk under uncertainty (Wauters et al., 2014), risk attitude categorizes individuals into three groups: risk-seeking, risk-neutral, and risk-averse. Research has shown that consumption decisions are influenced by both risk perception and risk attitude (Pratt, 1978; Lopes, 1987). Risk attitude not only influences the selection of risk management strategies (Barberis, 2013) but also modulates the intensity of risk perception via cognitive filtering mechanisms. Consequently, variations in risk attitude give rise to differing levels of risk perception, which in turn lead to distinct consumption behaviors (Volland, 2017; Xie et al., 2022). Specifically, risk-averse individuals tend to overestimate the likelihood and severity of potential losses, leading them to significantly reduce consumption to build a financial safety net (Kai-Ineman and Tversky, 1979). Conversely, risk-neutral individuals align their consumption primarily with household needs and financial constraints, while risk-seeking individuals exhibit greater tolerance for uncertainty - often perceiving it as an opportunity - and may resort to borrowing or other strategies to meet future needs, resulting in a lower tendency toward precautionary savings (Guiso and Paiella,2008). Thus, we propose Hypothesis 3:

H3: Risk preference mitigates the suppressive effect of PPLR on household consumption.

According to social risk-buffering theory, government interventions can effectively mitigate residents’ economic vulnerability and stimulate consumption growth through policies such as the expansion of public services, the development of a robust social security system, and fiscal transfer payments (Cameron and Shah, 2015). Enhancing the provision of basic public services is essential for improving livelihoods. Such services yield both “income-enhancing” (Ganong et al., 2020; Bianchi et al., 2016; Thaler, 1990) and “expenditure-reducing” (Xiong et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2024) effects. These effects elevate residents’ sense of security, curb the need for precautionary savings, and unleash consumption potential. Specifically, investments in primary education and universal healthcare effectively address limited school access and high medical costs (Liang et al., 2024), promoting human capital development and increasing household income. In addition, policies such as strict regulations on housing speculation, housing renovation subsidies, and affordable housing initiatives mitigate the crowding-out effect on other consumption categories (Hui et al., 2018). Social insurance, through its risk-sharing mechanism, mitigates extreme economic risks faced by residents (Browning and Lusardi, 1996; Hubbard, 1995). Empirical findings reveal that once social insurance coverage reaches a critical threshold, residents’ risk discount factors decline significantly, thereby diminishing the suppressive impact of risk perception on consumption (Engen and Gruber, 2001). Moreover, by systematically communicating livelihood policies and current developmental realities, the government can foster a more rational understanding of livelihood risks among residents, counteracting irrational fears that further curtail consumption. On this basis, we propose Hypothesis 4:

H4: Government intervention mitigates the suppressive effect of PPLR on household consumption.

Data and empirical strategies

Data

This study empirically investigates the impact of PPLR on household consumption behavior using micro-level data from four waves (2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020) of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Administered by the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University, the CFPS continuously tracks and collect data on household economic behavior and risk perception across 25 provincial-level administrative regions in mainland China (excluding Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Hainan). This dataset provides a robust micro-level empirical basis for examining the long-term dynamics of consumption. The selection of the 2014–2020 period is justified for several reasons: (1) this timeframe spans the conclusion of the 12th Five-Year Plan and the implementation of the 13th Five-Year Plan, enabling effective observation of the structural evolution in PPLR in the context of national strategic initiatives such as targeted poverty alleviation and rural revitalization; (2) the biennial tracking design facilitates the identification of long-term risk accumulation trends, such as employment adjustments following the 2016 supply-side structural reform and the repercussions of the 2018 US-China trade dispute on China’s export-driven economy - while minimizing distortions from short-term volatility inherent in annual data; and (3) as 2020 marks the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the data capture the abrupt impact on high-risk groups, including informal workers and interprovincial migrant laborers. Through a longitudinal comparison with preceding waves, this study isolates the marginal impacts of extreme external shocks on the PPLR-consumption relationship, thereby elucidating the intrinsic connection between PPLR and household consumption behavior. Moreover, province-level economic indicators, such as per capita GDP and financial loan data, are introduced as control variables to account for the influence of regional developmental disparities on micro-level behavior.

Before the empirical analysis, were processed as follows: (1) a hierarchical linkage was established among the household, adult, and household member databases using the household identification code, creating a unified analytical unit; (2) the household member identified as “most familiar with household finances and capable of answering financial questions” was designated as the household head, and samples with household heads younger than 16 years were excluded; (3) only records with positive household income and consumption were retained, eliminating cases in which total annual consumption or survival-related expenditures were zero; (4) all monetary indicators (e.g., income, expenditure, assets, and GDP) were adjusted to constant 2013 prices using the Chinese Consumer Price Index (CPI) to account for inflation; (5) to ensure sample continuity, comparability, and information richness, only those samples that participated in at least three survey waves were included; and (6) records with missing, anomalous, or invalid key variables were removed. After these steps, an unbalanced panel dataset was constructed, consisting of 30,557 households across four time points: 7959 samples in 2014, 8191 in 2016, 8146 in 2018, and 6281 in 2020.

Variables

Household consumption

This study measures household consumption through two dimensions: consumption level and consumption upgrading. The analysis focuses on daily household consumption, with expenditures classified into three categories per the National Bureau of Statistics of China: survival consumption (food, clothing, housing), development consumption (healthcare and education & culture), and enjoyment consumption (transportation and communication, household equipment and supplies, and others). Total household expenditure is calculated as the sum of these categories, with its natural logarithm as a proxy for the household consumption level. Drawing on previous literature (Qi and Liu, 2020; Hu et al., 2023), the share of development and enjoyment consumption expenditures relative to total consumption expenditure is used as a proxy for consumption upgrading.

People’s perception of livelihood risks

PPLR refers to the residents’ subjective and integrated assessment of both the likelihood and potential losses associated with uncertain events in the livelihood sector (e.g., unemployment or sudden increases in medical expenses). In alignment with China’s current livelihood policies, this study utilizes a core item from the CFPS questionnaire - “How serious do you think the following issues are in our country?” - as the measurement instrument. This item probes perceptions of key livelihood challenges, including employment, education, housing, healthcare, income disparity, and social security, rated on a 0–10 Likert scale (0 = not serious at all, 10 = extremely serious), where higher scores indicate greater perceived severity of risk in each domain. By employing the entropy weight method to assign weights to these dimensions, a comprehensive, multi-dimensional PPLR index is constructed.

Consumer confidence

Due to data constraints, this study uses the CFPS survey question “How confident are you about your future?” as the indicator for consumer confidence. This item is rated on a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = no confidence, 5 = very confident), with scores positively correlated with consumption confidence, such that higher scores reflect greater consumer confidence.

Risk attitude

Due to the absence of direct measures of risk attitude in the CFPS questionnaire, this study constructs a proxy variable for risk attitude following the methodology outlined in the literature (Chen, 2019). Two questionnaire items were selected: “Does your household currently hold any financial products (such as stocks, funds, government bonds, etc.)?” and “What is the total return from financial investments in the past 12 months?” These items are used to infer risk preferences based on household participation in risky financial investments. Households that continue to hold risky financial investments after incurring losses in the previous period are assumed to exhibit high-risk tolerance and a strong pursuit of risk; these are classified as extremely risk-seeking and assigned a value of 3. If residents either break even in the previous period and maintain their investments, or did not invest previously but start investing in the current period, they are deemed to have a moderate risk acceptance and are classified as comparatively risk-seeking, with a value of 2. Households that continue holding profitable investments from the previous period or exit the market after experiencing losses demonstrate a conditional openness to risk, adjusting strategies based on investment outcomes; these are categorized as generally risk-seeking and assigned a value of 1. Households that have never participated in risky financial markets - precluding determination of whether they are risk-neutral or risk-averse - are classified as non-risk-seeking and assigned a value of 0. This classification forms an ordered variable ranging from 0 to 3, where higher values indicate greater risk preference, derived from the relationship between households’ intertemporal investment decisions and their profit or loss outcomes.

Government intervention

In this study, the government intervention variable is constructed using the CFPS survey question, “How would you rate the overall performance of your county or county-level city/district government last year?” This item is assessed on a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied) to capture public evaluation of local government performance. The variable indicates the extent of public endorsement of the local government’s efforts in the preceding year; higher scores suggest effective policy implementation and a strong sense of accountability in managing livelihood risks.

Control variables

In line with existing literature on household consumption, this paper incorporates control variables across three dimensions: the personal characteristics of the household head, family economic characteristics, and regional characteristics. Specifically, personal characteristics of the household head include variables such as gender, age, marital status, health status, and education level (Qi and Liu, 2020; Chamon and Prasad, 2010). Family economic characteristics include household size, child dependency ratio, elderly dependency ratio, per capita income, and financial asset holdings (Agarwal and Qian, 2014; Aladangady, 2017; Kukk, 2016). At the regional level, the model controls for macroeconomic indicators including provincial economic development and financial deepening (Zhang et al., 2020). Detailed definitions of these variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the analyzed variables. As shown in the data, the sample households have an average income of 20,650.75 RMB and financial assets of 72,614.08 RMB. Regarding household heads, the majority are male, with a mean age of 51.39 years, 96% are married, and they report average health status and 7.89 years of formal education. The average household size is 4.24 members. Notably, these families bear a substantial dependency burden, as evidenced by a combined child-dependency and elderly-dependency ratio of 0.61.

Fig. 1 presents the dynamics of PPLR and household consumption among the sample residents from 2014 to 2020. The data show significant improvements in both the level and structure of household consumption in China. Average annual household consumption rose from 44,639.19 yuan to 61,908.39 yuan, indicating an overall increase of 38.686%. The highest growth rate occurred between 2014 and 2016 (19.831%), followed by stabilization at 7.498% to 7.662% in subsequent periods. Consumption upgrading rose gradually from 0.408 in 2014 to 0.430 in 2018, but reverted to its initial level in 2020, indicating temporary obstacles to upgrading. The PPLR index remained low overall (ranging from 0.041 to 0.047), though its fluctuations were pronounced; it increased by 6.818% to 0.047 during 2014–2016, dropped to 0.041 in 2018, and rebounded to 0.046 in 2020. It is noteworthy that in 2020, the slowdown in consumption growth and a temporary decline in consumption upgrading (–5.116%) coincided with a 12.195% rebound in PPLR. This phenomenon suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may have suppressed consumption by reinforcing PPLR.

Figure 2 highlights a distinct “stratification” pattern in PPLR. Households in rural and underdeveloped areas of western China, characterized by fewer years of education and poorer economic conditions, exhibit a stronger PPLR, compared to those from higher social strata. This may be due to their greater exposure to risks such as unemployment, employment instability, persistent income declines, and various challenges in accessing quality education, healthcare, improving living conditions, and social welfare. The immense pressure of daily life exacerbates their concerns about future uncertainty, creating a stronger risk perceptions. It is worth noting that this finding contrasts sharply with the view proposed by Xu and other scholars, who suggested that “the higher the social class, the stronger the PPLR” (Xu et al., 2021).

Empirical strategy

Basic regression model

To examine the impact of PPLR on household consumption, this study constructs the following baseline regression model:

Where:

- The dependent variable \({{Con}}_{{it}}\) represents the consumption of household i in year t.

- The independent variable \({{\rm{PPLR}}}_{{it}}\) denotes the livelihood risk perception level of household i in year t.

- \({P}_{{it}}\)、\({F}_{{it}}\)、\({R}_{{it}}\) are control variables at the individual, family, and regional levels, respectively.

-\({\alpha }_{0}\)、\({\alpha }_{1}\)、\({\alpha }_{2}\)、\({\alpha }_{3}\) are the parameters to be estimated.

- \({\mu }_{i}\) represents the province fixed effect.

- \({\delta }_{t}\) represents the year fixed effect.

Transmission mechanism model

Consumer confidence significantly influences household consumption levels and consumption upgrading. To clarify the relationship between PPLR, consumer confidence, and household consumption and to specifically assess whether consumer confidence mediates the suppressive effect of PPLR on household consumption, this study adopts the mediation analysis framework proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) and Wen et al. (2014). This approach is used to test Hypothesis 2. The specific mediation models are as follows:

Where:

- \({{Con}\_{conf}}_{{it}}\) is the consumer confidence evaluation for household i in year t.

- \({\beta }_{0}\)、\({\beta }_{1}\)、\({\beta }_{2}\)、\({\beta }_{3}\) are the parameters to be estimated.

-The meanings of the other variables are the same as in Model (1).

3.4.3 Moderating effect model

In Model (3), the role of consumer confidence as a potential transmission mechanism in the relationship between PPLR and household consumption, with a focus on mitigating future uncertainty risks. However, this analysis has limitations, as it does not account for the influences of household risk tolerance and government intervention measures. To address this, we construct a moderation effect model to verify whether risk preference and government intervention can effectively alleviate the suppressive effect of PPLR on household consumption, thus evaluating Hypothesis 4 and Hypothesis 5. To achieve this, we incorporate interaction terms of PPLR and risk preference, as well as PPLR and government intervention, into Model (1), to construct Moderation Effect Models (4) and (5). The specific models are as follows:

where:

-\({{Risk\_att}}_{{it}}\) represents the risk preference of household i in year t.

-\({Gov\_inter}\) represents government intervention.

- \({{risk}\_{per}}_{{it}}\times {{Risk\_att}}_{{it}}\) represents household.

- \({\beta }_{0}\)、\({\beta }_{1}\)、\({\beta }_{2}\)、\({\beta }_{3}\) are the parameters to be estimated.

-The meanings of the other variables are the same as in Model (1).

Result

The direct impact of people’s PPLR on household consumption

Table 3, based on the regression results from Model (1), indicates that PPLR exerts a significant inhibitory influence on household consumption. Specifically, Columns (1) and (2) report the effects of PPLR on household consumption levels without and with control variables, respectively, while Columns (3) and (4) demonstrate its impact on consumption upgrading under the same conditions. The findings reveal a statistically significant negative relationship between PPLR and household consumption at the 1% significance level. Each 1-unit increase in PPLR is associated with a 72% reduction in household consumption and a 13.10% downgrade in consumption structure. To illustrate this impact, the analysis uses the 2020 median household consumption of 45,170 yuan as a benchmark. According to the results, the average annual consumption per household would decline by 32,522.40 yuan (45,170 × 72%), with development/enjoyment expenditure (median proportion of 39.22%) decreasing by 1670.94 yuan (32,522.40 × 39.22% × 13.10%). Extrapolating this effect to China’s 494 million households (per the National Bureau of Statistics’ “Seventh National Population Census Bulletin”), national consumption could contract by approximately 160.66 trillion yuan (32,522.40 × 4.94), equivalent to 158.13% of China’s 2020 GDP (101.60 trillion yuan). Overall, these results indicate the highly elastic suppressive effect of PPLR on household consumption, suggesting its potential systemic repercussions for national economic development, thereby confirming Hypothesis 1.

The regression results in Columns (2) and (4) elucidate the effects of control variables on household consumption. In terms of the individual characteristics of the household head, the positive and statistically significant coefficients for gender, marital status, and education level imply that females, married, and more educated household heads tend to have higher consumption expenditure. This increase is accompanied by a shift in consumption structure from basic survival-related spending to development-oriented and enjoyment-based spending. However, the negative significant coefficients for age and health suggest that older household heads or those in good health tend to exhibit lower consumption expenditures.

In terms of family characteristics, household size significantly influences household consumption, but the analysis reveals no notable effects of child dependency ratio or elderly dependency ratio on consumption outcomes. The urban-rural divide significantly affects household consumption: urban households exhibit consumption levels 10.20% higher than those of rural households, yet their consumption upgrading is 4.70% lower. This may be due to rural households’ lower costs for essentials like food and housing, coupled with rising income levels and evolving consumption attitudes. Government policies such as “new energy vehicles and home appliances for rural areas” and the spread of the internet and rural e-commerce have accelerated the upgrading of rural household consumption structure. Additionally, per capita household income has a positive impact on both consumption level and consumption upgrading.

Finally, there is a significant positive correlation between regional economic development and household consumption. This is because economic growth generates job opportunities, increases household income, and thus enhances consumption capacity.

Endogeneity analysis

To address potential endogeneity, this study adopts the two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach and selects two instrumental variables: the average PPLR of other residents in the respondent’s community (excluding the respondent) and the number of corrupt officials. The selection of the community average PPLR as an instrument is justified for two reasons: (1) residents in the same community share a similar policy environment, making the community mean a robust proxy for collective PPLR that is strongly correlated with individual perceptions; and (2) aggregated subjective perceptions at the community level are unlikely to directly cause differences in household consumption expenditures. Nonetheless, this instrument has certain limitations. First, community PPLR is often influenced with factors such as local economic conditions, the supply of public services, and overall community governance performance, which are not fully captured by CFPS control variables, potentially introducing omitted variable bias. Second, individual PPLR is affected by the overall community environment while simultaneously influencing the community mean through social networks, creating a bidirectional causality issue. Finally, extreme polarization within a community could distort the accuracy of the community average, leading to measurement errors.

In response, this paper adds the number of corrupt officialsFootnote 2 as an additional instrumental variable. The rationale is that corruption diverts public fiscal resources, exacerbating livelihood challenges and thereby heightening PPLR, yet it does not directly affect household consumption. In addition, this paper includes livelihood fiscal expenditure as a control variableFootnote 3. Livelihood fiscal subsidies alleviate the economic pressure in areas such as education, healthcare, and housing (Hu et al., 2025), thereby promoting other types of consumption. Furthermore, regional livelihood fiscal investment is negatively correlated with risk perception and positively correlated with corruption levels (Aizer et al., 2016; Zhang, 2019).

As demonstrated in Table 4, the first-stage regression results (columns (1)–(2)) reveal that community average risk perception and official corruption both exert a significantly positive influence on individual PPLR, confirming the strong explanatory power of the selected instrumental variables for the endogenous variable PPLR. Instrument validity tests yield an F-statistic of 283.348 (P = 0.000) and the Sargan test rejects the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, thus confirming the exogeneity of the instruments. In addition, the Durbin and Wu-Hausman statistics consistently indicate the presence of endogeneity. Furthermore, the LIML estimation results presented in columns (4–5) of Table 4 closely align with the 2SLS regression outcomes, providing robust evidence that PPLR suppresses household consumption and thereby corroborating Hypothesis 1.

Robustness test

Replacing the dependent variable

To verify the robustness of the findings, this study replaces household consumption level with the Engel coefficient and substitutes the consumption upgrading measure with a consumption structure advanced index. The consumption structure advanced index is defined as the ratio of development-oriented consumption expenditure to basic consumption expenditure, where higher values indicate greater consumption upgrading (Sun, 2023). The regression results, presented in Columns (1)–(2) of Table 5, demonstrate that the effect of perceived livelihood risk (PPLR) on both household consumption level and consumption upgrading remains statistically significant even after these substitutions, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression outcomes.

Replacement of data sources

In this section, we incorporate data from the Chinese Social Survey (CSS), published by the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, to conduct a cross-data source robustness test. The CSS database comprises mixed cross-sectional data for the years 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2021, which, in conjunction with the CFPS data, create complementary samples interwoven across cycles. This integration provides robust empirical support for studying the consumption effects of PPLR. Variable construction adheres strictly to the procedures described in Section “Data”, “Data and Variables” with the measurement of the dependent variable remaining consistent. The core explanatory variable is derived from the CSS questionnaire item “Evaluation of the social security provided by the government” (covering six dimensions: employment, education, healthcare, housing, social security, and minimum living guarantee). A PPLR index is constructed using the entropy weight method. The regression results, presented in Columns (3–4) of Table 5, show a significantly negative coefficient for PPLR, further corroborating Hypothesis 1.

Propensity score matching regression

Although this study has used instrumental variable methods to address potential endogeneity issues in the core explanatory variable, selection bias may persist due to inherent differences between individuals with high and low PPLR. To mitigate this bias, we utilize the propensity score matching (PSM) method to balance these differences and verify the robustness of the finding that PPLR suppresses household consumption. Table 6 presents the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) values derived from three matching methods: one-to-four nearest neighbor matching, caliper matching, and kernel matching. The results show a significant negative effect of PPLR on household consumption across all matching methods.

Mechanism analysis

Transmission mechanism analysis

Consumer confidence, as a key indicator of residents’ psychological state, often shapes both current and long-term consumption decisions. Compared to optimistic and confident households, pessimistic household tend to adopt cautious and conservative consumption behavior. The regression results in Column (1) of Table 7, based on Model (2), show that PPLR negatively affects consumer confidence. Further, the regression results in Columns (2) and (3), based on Model (3), show that the test statistics for consumer confidence are significant at the 1% level. These results indicate that PPLR indirectly suppresses household consumption by lowering consumption confidence, validating Hypothesis 2.

Moderation mechanism analysis

As for the moderating role of risk attitude, risk attitudes significantly influence household consumption behavior, particularly in current consumption decisions. Individuals with greater risk preference tend to approach uncertainty proactively, increasing current consumption by reducing their sensitivity to potential risks. This psychological mechanism prompts them to perceive risks as opportunities for immediate gratification or potential gains, rather than as barriers to consumption. The regression results in Columns (1) and (3) of Table 8, derived from Model (5), show that the interaction term between PPLR and risk attitudes has a positive effect on household consumption, though its impact on promoting consumption upgrading is less pronounced. These findings suggest that risk preference moderates the suppressive impact of PPLR on household consumption, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

In terms of the moderating effect of government intervention, solving livelihood issues and ensuring public welfare are fundamental responsibilities of the government. Whether dealing with challenges in employment, healthcare, housing, education, income, and social security individually or addressing multiple complex issues in the livelihood sector, the government must show a high degree of responsibility and proactive engagement. Inadequate handling of these issues can lead to their entanglement and trigger systemic social risks that ultimately undermine social stability. According to the regression results shown in Columns (2) and (4) of Table 8 from Model (5), the interaction term between PPLR and government intervention has a positive effect on household consumption levels and consumption upgrading, with statistical significance at the 5% level for consumption levels and the 10% level for consumption upgrading. These findings indicate the importance of effective government intervention in the livelihood sector in mitigating the negative effect of PPLR on household consumption. In other words, robust government performance in addressing livelihood issues mitigates the negative impact of PPLR on household consumption, thereby supporting Hypothesis 4.

Heterogeneity analysis

Heterogeneity analysis across consumption levels and structures

To explore the differential effects of PPLR on consumption groups, this study stratifies the sample based on the mean values of consumption level and consumption upgrading, and applies the Chow test to identify group differences. As indicated in Table 9, the Chow test statistics for the consumption level grouping and the consumption upgrading grouping are 669.11 and 1428.22, respectively (P < 0.01), indicating significant differences in the impact of PPLR across consumption groups. Specifically, the negative impact of PPLR is more pronounced in the high consumption level group (β = −0.229) compared to the low consumption level group (β = −0.204). Similarly, PPLR exerts a greater impact on groups with lower consumption upgrading (β = −0.143) than on those with higher consumption upgrading (β = −0.112). With respect to consumption level, high consumption groups are inclined to allocate a larger income share to high-priced goods or development and enjoyment expenditures, which are more susceptible to reduction or substitution as risk perceptions intensify, thereby amplifying the effect of PPLR. In contrast, low consumption groups mainly focus on essential items, such as food, clothing, and housing, with limited room for further cuts; therefore, the marginal impact of PPLR is comparatively smaller. Regarding consumption upgrading, groups with lower upgrading levels, whose consumption patterns are still forming, exhibit high elasticity in demand for development and enjoyment consumption, leading to greater reductions when risk perceptions rise. In contrast, groups with higher consumption upgrading show more stable patterns, such as regular tourism or advanced healthcare, supported by robust asset allocation and credit capacity, which buffer short-term liquidity pressures and mitigate the adverse influence of PPLR.

Heterogeneity analysis by regional distribution

Urban-rural heterogeneity

The rural consumption market holds vast potential and serves as a critical driver of domestic demand (Yu et al., 2024). Subgroup regression results by urban and rural residents (Table 10) show that PPLR has a stronger suppressive effect on consumption level among urban residents, while its negative impact on consumption upgrading is more pronounced among rural residents. Urban residents, characterized by high commodification of daily necessities, heavy reliance on social security, and limited access to substitute resources like land (Zhang and Li, 2020), exhibit lower resilience to risk. When PPLR intensifies, urban residents reduce non-essential service consumption and opt for lower-priced substitutes, leading to a marked decline in overall consumption. In contrast, although rising incomes among rural residents drive demand for durable goods and leisure services, their development/enjoyment consumption remains highly elastic and less rigid. Consequently, when PPLR increases, the limited wealth accumulation in rural households barely covers basic survival needs, resulting in a significant reduction in development and enjoyment consumption expenditures.

Heterogeneity by East, Central, and West Regions

In China, regional heterogeneity in economic development, livelihood service provision, and consumption policy frameworks result in heterogeneous impacts of PPLR on household consumption. To explore these differences, the full sample was divided into three subsamples: Eastern, Central, and Western regions, for separate regression analyses. Table 11 shows that the suppressive effects of PPLR on household consumption differ significantly across regions. For consumption levels, the negative impact is most pronounced in the Central region, followed by the Eastern region, and least evident in the Western region. With respect to consumption upgrading, a statistically significant downgrading effect is observed only in the Eastern region, with no significant effects in the Central or Western regions. This pattern may be attributed to the Eastern region’s service-sector dominance and diverse consumption profile, where development and enjoyment consumption account for an average of 44.33% of the sample. High market orientation renders this region structurally sensitive to consumption suppression, driving residents to cut non-essential high-end services - such as entertainment and tourism - under intense PPLR shocks, giving rise to consumption downgrading. Conversely, local policy instruments (consumption vouchers) often subsize everyday necessities and durable goods rather than services, thereby exacerbating structural contraction. In the Central region, ongoing industrial restructuring and rapid urbanization, combined with inadequate social security and industrial volatility, expose households to income fluctuations and rigid expenditure burdens. This contributes to a broad reduction in consumption without differentiation. In the Western region, characterized by lower economic development and a high proportion of survival consumption (60–65% since 2014), PPLR affects consumption levels to a limited extent. Central transfer payments and informal mutual aid networks among residents provide a cushioning effect, mitigating the impact on survival consumption. As a result, the consumption structure remains relatively stable, exhibiting a pattern of constrained overall consumption with a rigid structure, resistant to systemic downgrading.

Heterogeneity analysis by socioeconomic status

Heterogeneity by income levels

Income significantly influences household consumption. To explore the heterogeneous effects of PPLR, the sample is stratified into three income groups based on per capita household income: low-income group (per capita income ≤15,000 RMB), middle-income group (15,000 RMB < per capita income ≤35,000 RMB), and high-income group (per capita income > 35,000 RMB). Table 12 shows that PPLR significantly suppresses consumption levels across all income groups and induces a consumption structure downgrade in both low-income and high-income households. Notably, high-income households exhibit the strongest sensitivity, experiencing the greatest reduction in total consumption and the most pronounced downgrade in consumption structure. This may be due to high-income households’ significant allocation of assets to financial investments, which are highly sensitive to economic volatility, coupled with increased precautionary savings driven by high occupational mobility. Additionally, social status pressures force these households to cut non-essential spending to maintain their public image. Consequently, under PPLR conditions, high-income households face compounded pressures, experiencing a significant decline in overall consumption and a structural downgrade.

Heterogeneity by education level

Education level reflects differences in individuals’ learning abilities, risk perception, and consumption attitudes. To investigate the heterogeneous role of education as a human capital factor in moderating consumption behavior, we categorize the sample into two groups based on years of education. With an average of 7.68 years of education in the sample, individuals with 9 years or fewer are classified as the low-education group, while those with more than 9 years form the high-education group. The subgroup regression results in Table 13 show that PPLR has a stronger suppressive effect on the consumption levels of the low-education group, while it exerts a greater inhibitive effect on consumption structure upgrading in the high-education group. These findings suggest that education level moderates responses to livelihood risks, differentially influencing household consumption levels and structure.

Conclusion

This paper develops a theoretical framework to systematically examine the effect of PPLR on household consumption and its underlying mechanisms, empirically testing these propositions using panel data from the CFPS. The main findings are as follows. (1) PPLR significantly suppresses household consumption, reducing both overall consumption levels and inducing a downgrading of the consumption structure. Mechanism analysis shows that this adverse effect is rooted in a lack of consumer confidence: heightened risk perceptions erode confidence, strengthen precautionary saving motives, and reduce current consumption propensity. However, the moderating roles of risk preferences and government intervention can alleviate this inhibitory effect; and (2) the suppressive effect of PPLR on consumption varies across groups and regions. With respect to consumption levels, households with higher consumption, urban households, those in the eastern region, high‑income groups and less educated groups experience stronger effects. For consumption structure, households with lower consumption, rural households, those in the eastern region, high‑income groups and more educated groups experience more pronounced downgrading.

The findings of this study offer crucial policy implications. First, it is imperative to recognize, in an objective manner, the importance of ensuring and improving livelihoods for economic and social development. On one hand, policies should reduce regional imbalances in livelihood service provision. While the Eastern region continues to enhance its public services, concerted efforts are needed to increase livelihood investments in the Central and Western regions through optimized resource allocation, the establishment of a project supply compensation mechanism, and systematic promotion of equitable regional development. On the other hand, policy initiatives should improve the livelihood conditions of rural areas and for vulnerable populations by enhancing access to quality basic education, developing a robust employment support framework, strengthening healthcare services, improving housing security standards, and reinforcing social security networks to address gaps in livelihood development.

Secondly, it is necessary to build a consumption resilience support system oriented toward livelihoods. In the Eastern region, where the consumption structures are highly sensitive, it is recommended to introduce a “development and enjoyment-oriented consumption security plan.” This plan would involve government and market collaboration to share risks associated with consumption structure fluctuations, alongside optimizing consumption voucher distribution by allocating a portion to cultural entertainment, tourism, and healthcare. In the Central region, a “social security payment deferral and rights retention” policy should be introduced to ease household consumption pressure during industrial transformation. In the Western region, policymakers should increase the share of central transfer payments used for consumption protection, prioritizing coverage of essential survival needs, including food, clothing, and housing, so as to enhance the risk resilience of low-income populations.

In addition, digital finance has been shown to significantly mitigate livelihood risks and stimulate consumption potential (Gomber et al., 2017; Ozili 2018; Li et al., 2020). Therefore, policymakers should accelerate the development of digital infrastructure, deepen the integration of digital financial services across various livelihood sectors, and enhance public awareness and proficiency in utilizing digital finance. These efforts will ensure that digital finance can benefit a wider range of population.

Data availability

Due to the restrictions outlined in the CFPS Data Use Agreement (https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/cjwt/fbxg/1379024.htm), the study is not permitted to share the raw or processed datasets on external websites. However, the raw CFPS data is publicly available on the official CFPS website (https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/).

Notes

In the international, the concept of “Minsheng” is not common; instead, governments and academics often use terms such as “livelihood”, “well-being” and “welfare” to discuss the protection of citizens’ rights and the boundaries of State responsibility. In China, “Minsheng” has a rich and specific connotation, which is a generalization of the basic existence, quality of life, and social justice of nationals, specifically, people’s livelihood covers many areas such as employment, education, medical care, housing, old age, childcare, public security and environmental protection, etc. The concept of “seven accesses” was raised in the Report to the 19th CPC National Congress in 2017, which emphasized the need to improve people’s lives, address their concerns, strengthen areas of weakness through development, and promote social fairness and justice. The seven aspects include people’s access to childcare, education, employment, medical services, elderly care, housing, and social assistance.

The number of corrupt officials refers to the number of government officials prosecuted by the procuratorial authorities who have committed crimes of office. These data are sourced from the Procuratorial Yearbook of China and the work reports of the provincial people’s procuratorates.

Drawing on previous studies (Gu Cheng, 2024; Wang Liejun, 2023), expenditures directly related to livelihood—such as education expenditure, social security and employment expenditure, healthcare expenditure, and housing expenditure—are defined as livelihood fiscal expenditure. Data are obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

References

Agarwal S, Qian W (2014) Consumption and debt response to unanticipated income shocks: evidence from a natural experiment in Singapore. Am Econ Rev 104(12):4205–4230

Aguiar M, Bils M (2015) Has consumption inequality mirrored income inequality? Am Econ Rev 105(9):2725–2756

Aizer A, Eli S, Ferrie J, Lleras-Muney A (2016) The long-run impact of cash transfers to poor families. Am Econ Rev 106(4):935–971

Aladangady A (2017) Housing wealth and consumption: evidence from geographically linked microdata. Am Econ Rev 107(11):3415–3446

Andersen AL, Hansen ET, Johannesen N, Sheridan A(2022) Consumer responses to the COVID‐19 crisis: evidence from bank account transaction data. Scand J Econ 124(4):905–929

Bai CE, Wu BZ, Jin Y(2012) Effects of old age insurance contributions consumption and saving. Soc Sci China 08:48–71

Barberis NC (2013) Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: a review and assessment. J Econ Perspect 27(1):173–196

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182

Benito A (2006) Does job insecurity affect household consumption? Oxf Econ Pap 58(1):157–181

Bianchi F, Melosi L (2016) Modeling the evolution of expectations and uncertainty in general equilibrium. Int Econ Rev 57(2):717–756

Bovi M (2009) Economic versus psychological forecasting. Evidence from consumer confidence surveys. J Econ Psychol 30(4):563–574

Browning M, Lusardi A (1996) Household saving: micro theories and micro facts. J Econ Lit 34(4):1797–1855

Brüggen EC, Hogreve J, Holmlund M, Kabadayi S, Löfgren M (2017) Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J Bus Res 79:228–237

Cameron L, Shah M (2015) Risk-taking behavior in the wake of natural disasters. J Hum Resour 50(2):484–515

Campos RG, Reggio I (2015) Consumption in the shadow of unemployment. Eur Econ Rev 78:39–54

Chamon MD, Prasad ES (2010) Why are saving rates of urban households in China rising? Am Econ J Macroecon 2(1):93–130

Chen B, Yang X, Zhong N (2020) Housing demand and household saving rates in china: evidence from a housing reform. J Hous Econ 49:101693

Chen X (2019) Does mental health affect households’ participation in risky financial markets? Evidence from China Family Panel Studies. China Econ Stud 2:27–42

De Nardi M, French E, Jones JB (2010) Why do the elderly save? The role of medical expenses. J Polit Econ 118(1):39–75

Deaton A (1991) Saving and liquidity constraints. Econometrica 59(5):1221–1248

Dees S, Brinca PS (2013) Consumer confidence as a predictor of consumption spending: evidence for the United States and the Euro area. Int Econ 134:1–14

Dong Z, Hui EC, Jia S (2017) How does housing price affect consumption in China: wealth effect or substitution effect? Cities 64:1–8

Dynan KE, Edelberg W, Palumbo MG (2009) The effects of population aging on the relationship among aggregate consumption, saving, and income. Am Econ Rev 99(2):380–386

Eika L, Mogstad M, Vestad OL (2020) What can we learn about household consumption expenditure from data on income and assets? J Public Econ 189:104163

Engen EM, Gruber J (2001) Unemployment insurance and precautionary saving. J Monetary Econ 47(3):545–579

Fan Y, Yavas A (2020) How does mortgage debt affect household consumption? Micro evidence from China. Real Estate Econ 48(1):43–88

Friend I, Lieberman C (1975) Short-run asset effects on household savings and consumption: the cross-section evidence. Am Econ Rev 65:624–633

Ganong P, Noel P, Vavra J (2020) US unemployment insurance replacement rates during the pandemic. J Public Econ 191:104273

Giglio S, Maggiori M, Stroebel J, Utkus S (2021) Five facts about beliefs and portfolios. Am Econ Rev 111(5):1481–1522

Gomber P, Koch JA, Siering M (2017) Digital Finance and FinTech: current research and future research directions. J Bus Econ 87:537–580

Gu C, Zhang JN (2024) Fiscal decentralization, audit supervision and responsiveness of Subnational Governments: empirical evidence from fiscal expenditure of municipal governments to meet basic living needs. Financ Trade Econ 45(6):21–37

Guiso L, Paiella M (2008) Risk aversion, wealth, and background risk. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(6):1109–1150

Hampson DP, Gong S, Xie Y (2021) How consumer confidence affects price conscious behavior: the roles of financial vulnerability and locus of control. J Bus Res 132:693–704

Han X, Wei C, Cao GY (2022) Aging, generational shifts, and energy consumption in urban China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 119(37):e2210853119

Hansson SO (2010) Risk: objective or subjective, facts or values. J Risk Res 13(2):231–238

Harmenberg K, Öberg E (2021) Consumption dynamics under time-varying unemployment risk. J Monetary Econ 118:350–365

Hayashi F (1985) The effect of liquidity constraints on consumption: a cross-sectional analysis. Q J Econ 100(1):183–206

Hu DL, Cai X, Li YJ (2025) Does the Fiscal Expenditure Structure Promote Residents’ Service Consumption?Res Financial Econ Issues 3:87–100

Hu D, Zhai C, Zhao S (2023) Does digital finance promote household consumption upgrading? An analysis based on data from the China family panel studies. Econ Model 125:106377

Huang W (2023) Risk perception, online search and consumption distortion. China Econ Q Int 3(2):88–102

Hubbard RG, Skinner J, Zeldes SP (1995) Precautionary saving and social insurance. J Political Econ 103(2):360–399

Hui EC, Dong Z, Jia S (2018) Housing price, consumption, and financial market: evidence from urban household data in China. J Urban Plan Dev 144(2):06018001

Kai-Ineman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):363–391

Katona G (1968) On the function of behavioral theory and behavioral research in economics. Am Econ Rev 58(1):146–150

Krueger D, Perri F (2006) Does income inequality lead to consumption inequality? Evidence and theory. Rev Econ Stud 73(1):163–193

Kukk M (2016) How did household indebtedness hamper consumption during the recession? Evidence from micro data. J Comp Econ 44(3):764–786

Lee JH, Kim W (2022) Impact of production-distribution income gap on household consumption and housing prices in the region. J Public Policy Stud (4):23–30

Leland HE (1968) Saving and uncertainty: the precautionary demand for saving. Q J Econ 82(3):465–473

Li J, Wu Y, Xiao JJ (2020) The impact of digital finance on household consumption: evidence from China. Econ Model 86:317–326

Li Z, Sha Y, Song X, Yang K, ZHao K, Jiang Z, Zhang Q (2020) Impact of risk perception on customer purchase behavior: a meta-analysis. J Bus Ind Mark 35(1):76–96

Li S, Wang M (2023) Effects of improved air quality on household consumption: empirical evidence from China Family Panel Studies. China Popul Resour Environ 33(10):24–34

Liang HJ, Zhang HL, Xia XL (2024) Study on basic public services, perceived social justice and consumption of rural residents.World. Agriculture 10:115–127

Lopes LL (1987) Between hope and fear: the psychology of risk. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 20:255–295

Luo C (2004) Uncertainty during economic transition and household consumption behavior in urban China. Econ Res J 39(4):100–106. in Chinese

Mi LH, Ryong KJ, Han JS (2019) The effect of perceived risk on negative emotions, trust, and investment intentions: focused on investors and potential investors. Int J Tour Hospitality Res 33:19–31

Modigliani F, Cao SL (2004) The Chinese saving puzzle and the life-cycle hypothesis. J Econ Lit 42(1):145–170

Morisset J, Revoredo C (1995) Savings and education: a life-cycle model applied to a panel of 74 countries. No. 1504. The World Bank

Mynaříková L, Pošta V (2023) The effect of consumer confidence and subjective well-being on consumers’ spending behavior. J Happiness Stud 24(2):429–453

Ozili PK (2018) Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Review

Pratt JW (1978) Risk aversion in the small and in the large. Econometrica 32:59–79

Qi H, Liu Y (2020) Change of population age structure and the upgrading of household consumption: an empirical research based on CFPS data. China Popul Resour Environ 30(12):174–184

Song Y, Gong Y, Song Y, Chen X (2024) Exploring the impact of digital inclusive finance on consumption volatility: insights from household entrepreneurship and income volatility. Technol Forecast Soc Change 200:123179

Stephens Jr M (2004) Job loss expectations, realizations, and household consumption behavior. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):253–269

Thaler RH (1990) Anomalies: saving, fungibility, and mental accounts. J Econ Perspect 4(1):193–205

Vanlaer W, Bielen S, Marneffe W (2020) Consumer confidence and household saving behaviors: a cross-country empirical analysis. Soc Indic Res 147:677–721

Volland B (2017) The role of risk and trust attitudes in explaining residential energy demand: evidence from the United Kingdom. Ecol Econ 132:14–30

Wang LJ (2023) Scale, characteristics, and trends of China’s expenditure on People’s Welfare. J Manag World 39(03):62–69

Wauters E, Van Winsen F, Yann de Mey LL (2014) Risk perception, attitudes towards risk and risk management: evidence and implications. Agricl Econ 60(9):389–405

Wen ZL, Ye BJ (2014) Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv Psychol Sci 22(05):731–745. in Chinese

Xie X, Tong Z, Xu S (2022) Risk attitudes and household consumption behavior: evidence from China. Front Public Health 10:922690

Xiong X, Yu X, Wang Y (2022) The impact of basic public services on residents’ consumption in China. Human Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–8

Xu YH, Lai DP (2021) On the risk perception in people’s livelihood and urban residents’ mental health. J East China Norm Univ 53(02):104–116

Yu S, Ma X, Zhan P (2024) Effects of the resident basic medical insurance reform on household consumption in China. China World Econ 32(1):96–129

Zeldes SP (1989) Consumption and liquidity constraints: an empirical investigation. J Political Econ 97(2):305–346

Zhang X, Yang T, Wang C, Wan G (2020) Digital finance and household consumption: theory and evidence from China. Manag World 36(11):48–62

Zhang X (2019) Fiscal decentralization and political centralization in China: implications for regional inequality. In China’s Rural Economy after WTO. Routledge, pp 310–324

Zheng C, Zhang J, Guo Y, Zhang Y, Qian L (2019) Disruption and reestablishment of place attachment after large-scale disasters: the role of perceived risk, negative emotions, and coping. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 40:101273

Acknowledgements

National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC) Major Project (20ZDA038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data employed in this study were obtained from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The CFPS dataset is a secondary dataset, so ethical approval was obtained by the CFPS project team, not by the authors of this paper. The CFPS project and its data collection procedures were granted ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB PU). The ethical approval number is IRB00001052-14010.

Informed consent

The informed consent of CPFS project can be found here:http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20200615135138318338.pdf.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, P., Li, L., Xu, M. et al. The impact of people’s perception of livelihood risks on household consumption in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 52 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05774-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05774-z