Abstract

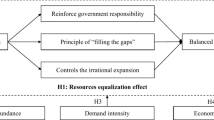

Medical humanities have demonstrated their significance in medical education and practice, significantly enriching the understanding of health care professions through profound explorations of life, illness, and the doctor–patient relationship. In response to shifting disease patterns and increasingly diverse health challenges, health humanities have emerged, expanding the boundaries of traditional medical humanities through a broader and more inclusive perspective. Certain scholars maintain that health humanities constitutes a superior and more inclusive conceptual framework than medical humanities. This contention prompts critical consideration of how these fields might navigate their evolving relationship within interdisciplinary scholarship. Notably, extant literature addressing both domains remains predominantly theoretical. In response, this study employs bibliometric keyword co-occurrence analysis—supplemented by visualisation tools—to systematically map medical and health humanities research retrieved from the Web of Science. Through this analysis, it systematically reveals their distinctions and interconnections within the academic landscape, proposing a novel framework to model their dynamic interaction. Keyword co-occurrence analysis identifies distinct research clusters: medical humanities (4 themes), health humanities (5 themes), and their intersection (6 themes). Subsequent comparison reveals three key distinctions within medical education practice:divergent educational audiences, contrasting curricular frameworks, and differentiated practical content; Humanitarian interventions: medical humanities and health humanities operate on distinct timescales; Public health engagement: medical humanities demonstrates insufficient attention to public and global health; Mental health applications: medical humanities focuses on distress alleviation, health humanities emphasises well-being promotion; Cost-effectiveness: health humanities represents the most economical approach for population health enhancement; Social justice imperative: health humanities application to health disparities is strategically indicated. While health humanities expand the scope of medical humanities, the former’s broad vision cannot encompass medical humanities’ profound understanding of life and disease. Consequently, their relationship is characterised by coexistence rather than substitution—enabling these complementary disciplines to collectively enhance human well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mindset of medical humanities has a long-standing history. In 1919, William Osler, hailed as the father of modern clinical medicine, delivered a keynote speech titled “The old humanities and the new science”, in which he first proposed the concept of medical humanists (Osler, 1919). In the following decades, however, medical humanities failed to develop. The rapid growth of medical technology in the 20th century, especially the rise of molecular biology in the 1960s, created new ways for scientists to explore the mysteries of life and disease. The widespread application of medical technologies in clinical practice has fostered a belief among clinicians that technology can overcome all clinical challenges while reinforcing medical authoritarianism. This paradigm assumes patient compliance with prescribed procedures as the primary pathway to disease eradication, resulting in the conceptual separation of illness from the person—a disjunction that ultimately precipitates the divorce between medical practice and humanistic values.

George Engel (1977) introduced the biopsychosocial model of medicine, which emphasises a holistic view of health and illness and the consideration of psychosocial factors. This model provided a theoretical basis for medical humanities, prompting the medical field to reaffirm the importance of medical humanism and spurring the growth of medical humanities. The biopsychosocial medical model initiated the shift from disease-centred to patient-centred medicine by integrating humanistic perspectives into clinical practice, thus providing profound insights into doctor–patient relationships while strengthening ethical and compassionate care. In 1978, the International Conference on Primary Health Care, meeting in Alma-Ata, strongly reaffirmed that health, which is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, is a fundamental human right and that the attainment of the highest possible level of health is the most important worldwide social goal whose realisation requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector (WHO). While the biopsychosocial medical model emphasised holistic health at the individual level, the Alma-Ata Declaration established population health rights through primary health care.

In 1986, the World Health Organization introduced the concept of “health promotion” in the Ottawa Charter, emphasising the role of individuals and communities in maintaining and improving health and advancing the development of a health-centred medical model (WHO, 1986). In the 21st century, we are confronted with an increasing number of complex global health challenges. It is unacceptable for global health systems to focus on a limited number of individuals while neglecting the billions who bear the greatest burden of disease (Onen, 2004). Against this backdrop, the concept of health humanities has emerged. Crawford’s perspective on health humanities suggests that art and the humanities can contribute to physical and mental well-being without needing to wait for a doctor’s prescription. By engaging in self-help, group, or community mutual assistance, especially through participation in art and humanities activities, people can improve their health through a variety of non-medical options (Crawford et al., 2010).

The growing contemporary discourse surrounding “medical and health humanities”—even occasionally phrased as “medical/health humanities” (Klugman et al., 2021)—prompts a fundamental question: what precisely constitutes the relationship between medical humanities and health humanities within this evolving academic landscape? Some scholars argue that the term “medical humanities” sounds exclusive. This term is often associated with clinical medicine, as though it does not encourage the involvement of paramedics, patients, or carers (Allsopp, 2020). Jones et al. (2017) also cited a common complaint among many health care professionals that the word “medical” denotes just that, medicine, not dentistry, nursing, pharmacy, or physiotherapy. Crawford et al. (2010) have argued that health humanities encompass medical humanities, whereas others have argued that the term “medical humanities” should be replaced by the more right and inclusive term “health humanities” (Jones et al., 2017; Squier, 2007). While the rise of health humanities has provided fresh perspectives and tools, whether its broad scope can encompass medical humanities’ profound understanding of life and disease and whether it can fully supplant medical humanities remain subjects worthy of rigorous enquiry.

This study employs bibliometric keyword co-occurrence analysis and visualisation tools to map medical and health humanities research. First, we identify core research themes and the health topics included within these themes. Building on these results, we then examine the distinctions in how these topics are approached within medical humanities versus health humanities. Previous scholarship on medical and health humanities has focused predominantly on theoretical perspective papers. This research objectively delineates the distinctions and interconnections between medical humanities and health humanities within academic research while revealing their respective limitations, thus advancing fresh perspectives for conceptualising their relationship.

Methods

Dataset construction

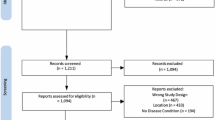

In the present study, data were retrieved from the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE, 1900–2023), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI, 1900–2023), and Arts & Humanities Citation Index (AHCI, 1975–2023) within the Web of Science (WOS) Core Collection database (Vlase and Laehdesmaeki, 2023; Yang et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). The search date was the publication date, ranging up to 31 December 2023, and the document types were articles, review articles and early access. The search terms for this study included medical, medicine, health, healthy, and humani*. Initially, a total of 7088 articles related to “medical humanities” were retrieved via the strategy (TS= (medical OR medicine)) AND TS = (human*), constituting dataset 1. Similarly, the strategy “(TS= (health or healthy)) AND TS = (humani*)” retrieved a total of 10,967 articles related to “health humanities”, constituting dataset 2. Notably, there is an intersection between dataset 1 and dataset 2 because of the shared research content in medical humanities and health humanities. This study aims to compare the research contents of medical humanities and health humanities. To eliminate the influence of the intersection above on the research results, we combined search sets (dataset 1 and dataset 2) using the AND or NOT operators to construct datasets 3, 4 and 5. The retrieval strategy for each dataset is shown in Table 1.

Data screening

Given the multidisciplinary convergence inherent in medical and health humanities scholarship, data acquired through topic searches may contain ostensibly related yet actually irrelevant works. Therefore, a manual screening process is often performed to identify the final literature to be analysed, thus ensuring its close relevance to the research topic.

The manual screening process consisted of three steps. First, the literature records (including titles, author keywords, and abstracts) containing irrelevant terms were screened out and removed. For example, the biomedical construct “humanised mouse” refers to genetically engineered or cell-engrafted murine models carrying functional human genes, cells, or tissues, which are specifically designed to mimic human physiological systems or disease pathogenesis. This literature is beyond the scope of this study. Second, the remaining records were excluded according to the research area, which included “construction building technology”, “energy fuels”, etc. After these two steps, most irrelevant records were eliminated. Finally, a comprehensive review of the records was conducted to identify the literature required for the study with the greatest accuracy. The data relationships and final screening results are illustrated in Fig. 1, and the entire screening process is depicted in Fig. 2.

Keyword standardisation

The records of articles downloaded from WOS contain two types of keywords: author keywords and keywords plus. Some records lack author keywords, and the keywords plus provided by WOS can—to a certain extent (approximately 20%) (Zhang et al., 2013)—serve as proxies for author keywords. For records lacking author keywords, we combined their titles and abstracts to assess whether keywords plus could effectively substitute for author keywords and increase the representation of content. Unstandardised keywords exhibit variations such as singular/plural forms, synonyms, and abbreviations (e.g., healthcare vs. health care, art vs. arts). To ensure accurate keyword frequency analysis and meaningful clustering results, it is necessary to standardise keywords by merging variants in the aforementioned categories.

Network visualisation

VOSviewer is a software tool for constructing and visualising bibliometric networks (see www.vosviewer.com). Yang et al. (2023) employed VOSviewer to conduct a keyword co-occurrence analysis of literature focused on policy analysis research, thus identifying the core concerns in this academic field. Aristovnik et al. (2020) employed the VOSviewer co-occurrence network analysis function to investigate the disciplinary differences in the content of COVID-19 research across the science and social science research landscape. This study uses the text mining function provided by VOSviewer to construct and visualise the co-occurrence network of keywords extracted from the medical and health humanities literature. In the keyword co-occurrence “Network Visualisation”, nodes represent keywords, and edges represent the co-occurrence relationship between keywords. Node size reflects the number of occurrences of the keywords, and the thickness of edges may represent the strength or frequency of co-occurrence. The colour of nodes is used to distinguish different clusters; each cluster can be assigned a unique colour, and different topics or research fields in the network can be quickly identified by the colour of the cluster (Van Eck and Waltman, 2010).

Results

Time trend of the publications

In general, the medical-health humanities field has exhibited consistent growth. Some scholars have described this growth as three waves (Zhang, 2015), but this study divided the growth trend into four stages. In the first stage (1902–1972), the earliest known paper in medical humanities appeared in 1902; from that point until 1967, only 18 papers were published. In the following 5 years, the number of publications in medical humanities was interrupted. During this period, two publications in health humanities in WOS appeared, in 1967 and 1972. In the second stage (1973-1989), the number of annual publications in medical humanities was stable, with an average of 4.1 publications per year and a total of 70 publications. At the same time, publications in health humanities began to appear, with a total of 28 articles. In the third stage (1990–2004), there were some small fluctuations in the number of annual publications. The average annual number of publications in medical humanities was 31.4, and the total number of publications was 471. The average annual number of publications in health humanities was 25.5, and the total number of publications was 357. In the last stage (2005–2023), the year 2005 was a watershed in terms of the number of medical humanities and health humanities publications because of two characteristics. First, the acceleration of the annual growth in medical and health humanities publications increased significantly after 2005, showing an exponential growth trend. Second, the number of annual publications in health humanities began to exceed that in medical humanities. The annual average numbers of publications in medical humanities and health humanities were 122.8 and 286.4, respectively, and the total numbers were 2334 and 5443, respectively. In terms of publication output, the relationship between health humanities and medical humanities across these four stages can be summarised as “far behind”, “within reach”, “neck and neck”, and “leading by a wide margin”. This alteration substantiates the transition in the perspective of health care from a disease-centric perspective to a health-centric perspective. The distribution of publication dates is shown in Fig. 3.

Results of keyword co-occurrence analysis

This section offers a thorough and detailed analysis of the research themes in the field of medical and health humanities. Table 2 presents the titles of each theme and the number of keywords contained.

Medical humanities

The keyword co-occurrence analysis identified 6351 keywords from 2909 records, with 210 keywords meeting the threshold, which formed four clusters. We determined the research theme of each cluster by analysing its constituent keywords.

Theme I (Fig. 4: red cluster) is titled “the disciplinary framework of medical humanities”. The keywords included in this topic mainly involve medical history, ethics, philosophy, literature, etc., which constitute the theoretical basis of medical humanities. The combination of medicine and ethics provides moral guidance and a decision-making framework for medical practice (Vevaina et al., 1993; Beauchamp, 2019). The ethics in the keyword network include “medical ethics”, “bioethics”, and “neuroethics”. The keywords related to the history of medicine include “anatomy”, “Renaissance”, “Galen”, and “Vesalius”. Galen and Vesalius, although separated by a thousand years, have together shaped our understanding of human anatomy. Galen was the first physician to systematically perform human dissections, and his work laid the foundation for medieval medicine (Standring, 2016), whereas Vesalius overturned many of Galen’s theories through empirical research, paving the way for the development of modern anatomy. The philosophy of medicine is also an important medical humanities discipline, providing ethical guidance, epistemology, critical thinking, values and principles for medicine (Dooley-Clarke, 1982). Philosophy of science is also related to philosophy of medicine. Arthur Caplan (1992) suggests that philosophy of medicine was actually a branch of philosophy of science and that its goal or focus should be on epistemology rather than ethics. Literary works can indirectly affect the doctor–patient relationship and provide deep insight into medical experience. The relevant keywords include “literature”, “narrative”, and “metaphor”. Keywords demonstrating the “interdisciplinarity” of medical humanities include “psychiatry”, “epistemology”, “neurology”, “sociology”, “psychotherapy”, “anthropology”, and “law”.

Theme Ⅱ (Fig. 4: green cluster) is titled “cultivating clinical humanistic literacy in medical education”. This theme focuses on how medical humanities can enrich the content of medical education, improve the professional quality and clinical ability of medical students, and improve physician‒patient relationships and medical service quality through humanistic care. Keywords associated with clinical competence and professionalism, including “humanism”, “humanistic practice”, “patient-focused care”, “palliative care” and “patient safety”, collectively represent the fundamental purpose of this thematic domain. Narrative reflexivity is exemplified by the keywords “narrative medicine”, “reflection”, “reflective writing”, “poetry”, and “film”. Narrative medicine is a form of “reflective writing” that emphasises the use of narrative in the medical process to increase the understanding of patients’ experiences, improve doctor–patient communication, and promote doctors’ empathy and reflective practice (Charon, 2001). The keywords “compassion” and “empathy” are the cornerstones of good medical practice (Isaac, 2023). Art plays a significant role in medical practice and medical education (Moniz et al., 2021). Figure 4 illustrates specific manifestations such as visual arts, which help medical students improve their observation ability, a skill crucial for clinical diagnosis (Chisolm et al., 2021). The keywords “gross anatomy education”, “death”, and “end of life” may pertain to the cultivation of reverence for life. Keywords related to teaching methods and evaluation include “curriculum”, “hidden curriculum”, “invisible courses”, “problem-based learning”, “assessment”, “educational measurement”, “evaluation”, etc.

Theme III (Fig. 4: blue cluster) is titled “humanitarian assistance during transnational crises”. Figure 4 shows that the causes of crises include the keywords “disaster”, “war” and “earthquake”. The target of assistance is “refugees” affected by disasters, with a particular focus on protecting “children”. Keywords such as “emergency medicine”, “disaster medicine”, “military medicine”, “surgery”, and “pain management” indicate a focus on providing surgical care in crisis situations. The keywords “resilience”, “rehabilitation”, and “quality of life” pertain to sustainable restoration in post-disaster contexts.

Theme Ⅳ (Fig. 4: yellow cluster) is titled “technoscience and humanistic values in the pandemic”. This thematic content exhibits a tripartite “pandemic–technoscience–humanities” structure, encompassing epidemiological dimensions (“COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “coronavirus”), technoscientific governance (“artificial intelligence” (AI), “machine learning” (ML), “evidence-based medicine”, “precision medicine”), and humanistic concerns (“humanitarian logistics”, “anxiety”, “depression”, “trauma”, “research ethics”). This theme integrates the spheres of medicine, technoscience, and humanistic care to investigate effective health care delivery during global health crises while achieving equilibrium between humanistic values and scientific advancement.

Health humanities

The keyword co-occurrence analysis identified 11,786 keywords across 5828 records, with 319 keywords meeting the threshold, which formed five clusters.

Theme I (Fig. 5: red cluster) is titled “nursing humanities education and primary health care”. With respect to disciplinary content, nursing humanities education is comparable to medical humanities education. At the practical level, “patient-centred care” and “effective communication” are the key contents of humanistic nursing practice. Providing medical care services that respect and meet the needs of patients and nursing staff is essential to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care (Kwame and Petrucka, 2021). Primary health care represents the initial point of contact for health care services, which are typically provided by family doctors, nurses, and other health professionals. Nursing staff assume a pivotal role in the delivery of primary health care, with responsibilities encompassing “health promotion”, “health education”, and “health management”. In the case of chronic conditions, trained nurses may be able to provide equal or possibly even better quality of care than primary care doctors (Laurant et al., 2018). The keywords “elderly”, “paediatrics” and “women’s health” indicate that particular groups, including elderly individuals, women and children, are the primary focus of health care services. The research content related to maternal health is particularly extensive, encompassing topics such as “pregnancy”, “prenatal care”, and “humanised delivery”. This theme explains the fundamental position and multifaceted function of nursing in contemporary medicine. By virtue of interdisciplinary education and patient-centred practice, nursing staff are able to provide patients with comprehensive and high-quality health care services. In particular, the work of nursing staff in the field of primary health care has a twofold impact: not only does it affect an individual’s health, but it also has a profound effect on the collective health of the community (Leipert, 1996). In conclusion, humanistic nursing facilitates the advancement of health care services in a manner that is more humane and of superior quality.

Theme II (Fig. 5: green cluster) is titled “global health topics and public health”. In the context of contemporary globalisation, many dimensions of public health are now global (Kraemer and Fischer, 2018). The field of global health encompasses a range of cross-border and cross-cultural health issues that have a profound impact on human well-being (Chen et al., 2020). The field of global health encompasses a range of cross-border and cross-cultural public health issues that have a profound impact on human well-being, including “infectious diseases”, “climate change”, “vaccination” and “health equity”. The infectious diseases in the keyword network specifically include “COVID-19”, “Ebola”, “HIV/AIDS” and “malaria”. The keywords closely linked to climate change are “global warming”, “environmental health”, “sustainable development” and “biodiversity”, all of which have important implications for human health. The strong link between vaccination and refugees suggests vaccination difficulties and vaccination inequalities for refugees (Crawshaw et al., 2022; Aghajafari et al., 2024). The right to health is a fundamental “human right” (WHO, 2023), as enshrined in numerous international laws. Achieving health equity is a crucial means of realising this right. The development and implementation of effective health policies and governance measures are essential for advancing health equity and social justice (Ruger, 2012). In the context of response strategies, the application of “AI” and “ML” is becoming increasingly prevalent in the domain of “public health emergencies”. These technologies offer a robust technical foundation for addressing and mitigating the challenges posed by such emergencies, as evidenced by the utilisation of ML algorithms for monitoring the propagation of the COVID-19 outbreak (Alimadadi et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023; Cho et al., 2024).

Theme III (Fig. 5: blue cluster) is titled “humanitarian assistance for refugees”. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the underlying causes of humanitarian crises are wars, armed conflicts and natural disasters, which have resulted in the forcible displacement of millions of individuals, mostly in “low- and middle-income countries” across the “Middle East” and “sub-Saharan Africa”. The plight of refugees is manifested mainly in the following six areas. (1) The non-satisfaction of the basic needs of refugees, who often lack access to food, clean water and safe shelter, poses a direct threat to their survival. (2) Special groups denoted by keywords such as “newborn, “infants”, “children”, “adolescents” and “maternal” may be exposed to higher health risks due to poor conditions, “malnutrition” and a lack of adequate medical care, particularly with respect to the “breastfeeding” of infants and young children and the nutritional status of children. (3) Security issues require special attention and protection, and the presence of “gender-based violence” makes women particularly vulnerable during crises. (4) In humanitarian crises, the provision of basic health care to control communicable diseases (e.g., cholera), maintain “sexual and reproductive health” and manage chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) becomes a major challenge. (5) “Malnutrition” and “food security” problems faced by refugees have serious impacts on their health and resilience. (6) During crises, “psychosocial” support is essential for alleviating psychological stress, promoting social integration and improving the quality of life of refugees. In addition, the theme includes needs and impact assessments of assistance, as well as monitoring of disease and nutritional status to ensure the effectiveness and relevance of assistance interventions. This theme focuses on the health impact of humanitarian crises and how effective response and implementation strategies can improve the health and well-being of affected groups.

Theme IV (Fig. 5: yellow cluster) is titled “mental health”. Mental health problems encompass a range of conditions, including “anxiety”, “depression”, “post-traumatic stress disorder”, and, in severe cases, “psychosis” and “schizophrenia”. In some instances, mental health problems may even result in “suicide”. The underlying causes of mental health problems can be attributed to various factors, such as “loneliness”, “trauma”, and “stress”. The illness itself can be a significant source of distress, particularly when coupled with the “stigma” and discrimination that individuals with mental health illnesses often face. As depicted in Fig. 5, the populations most affected by mental health concerns include “adolescents”, “older adults”, “university students”, individuals with “disabilities”, and “military” personnel. Mental health services are a series of interventions aimed at promoting individual psychological well-being and coping with psychological disorders. The content related to mental health services includes “psychometrics”, “counselling”, “psychosocial intervention”, and psychotherapy. The keywords related to psychological intervention include “positive psychology”, “mindfulness”, “self-care” and “self-compassion”. In mental health services, by integrating the principles of positive psychology, mindfulness exercises, and strategies to promote self-care and self-compassion, individuals can be helped to establish a stronger psychological adaptation mechanism and to improve their resilience. This comprehensive approach not only contributes to the rehabilitation of mental illness patients but also helps promote overall psychological well-being and quality of life (Slade, 2010). This theme focuses on improving the mental health of individuals and groups through humanistic care and scientific intervention strategies, especially coping ability and psychological resilience in the face of challenges such as life stress, social conflicts and disasters.

Theme V (Fig. 5: purple cluster) concerns the “economic burden of disease and quality of life of patients”. This topic focuses on a comprehensive assessment of the impact of disease on patients from multiple dimensions, and the way to obtain information such as patient quality of life is patient-reported outcomes (PROs). PROs refer to data reported directly from patients. As shown in Fig. 5, the information provided by these data includes overall quality of life, economic burden, disease burden, work productivity, outcomes, etc. In clinical trials and medical practice, PROs are considered important indicators for assessing treatment effectiveness and patient satisfaction. They are powerful tools for clinicians and policy-makers to address morbidity and patient suffering (especially in chronic diseases), which can influence clinical decision-making and health policy formulation (Anker et al., 2014).

Intersection

The keyword co-occurrence analysis identified 6174 keywords across 2762 records, with 325 keywords meeting the threshold of 5 occurrences, which formed six clusters. The intersectional component represents overlapping research between medical humanities and health humanities. Comparative analysis of Figs. 4–6 reveals that this intersection encompasses health topics addressed in both fields while also identifying an emergent theme: health disparities.

Theme VI (Fig. 6: orange cluster): health disparities. Health disparities refer to differences in health outcomes observed between populations or social groups that may include disease incidence, mortality, health status, longevity, etc. A multitude of factors contribute to these disparities, two of which are illustrated in the figure: gender and race. These two factors are associated with the keywords “diversity” and “cultural competence”. This result suggests that different races, ethnicities, and religions in the world each have their own distinctive cultures and that different cultural backgrounds shape people’s perceptions of health, understanding of disease, and treatment preferences. Furthermore, it indicates that cultural competence is a key competency for health care professionals to ensure that health care is respectful and adaptable to patients from different cultural backgrounds (Hoang and Erickson 1982). This theme is concerned with the analysis of health inequalities resulting from cultural diversity and gender differences.

Discussion

Before discussing the other distinctions between medical and health humanities, we need to clarify how they are conceptualised in this study. A logically coherent conceptual system with a rational structural hierarchy is an important indicator of whether medical humanities is a relatively independent discipline. Medical humanities lack a general conceptual or theoretical framework in the education of health professionals (Isaac, 2023). In this study, the “humanities” concept encompasses terms such as “humane”, “humanism”, “humanity”, and “humanitarian”, with medical humanities having three interrelated meanings: “medical humanistic spirit”, “medical humanistic care”, and “medical humanities disciplines”. In 2010, Crawford et al. (2010) formally introduced the “health humanities” concept in their paper, defining it as “the integration of arts and humanities into the education of all professionals engaged in healthcare, health, and well-being, advocating for enhanced sharing of artistic and humanistic resources among formal healthcare practitioners, informal caregivers, and patients themselves to improve health and care environments.” Health humanities emphasise that prioritising and sustaining existing therapeutic applications of arts and the humanities for the benefit of national health and social welfare constitutes less of a conceptual framework and more of an inclusive and applied approach. However, the keyword “health humanities” in this study occurred with insufficient frequency to meet the threshold for visual representation, indicating that the field is rarely conceptualised holistically. Nevertheless, health humanities encompass emergent concepts—including global health humanities (Stewart and Swain 2016; Hassan and Howell 2022), planetary health humanities (Lewis, 2021), and integrative health humanities (Duan, 2017)—that provide novel perspectives and methodologies, advancing the field towards maturity.

Figures 4–6 illustrate the integral relationship between humanities disciplines and medical education. This study identifies three key distinctions in how medical humanities and health humanities manifest within medical education practice: distinct educational audiences, divergent curricular frameworks, and differentiated practical content.

Medical humanities and health humanities target distinct educational audiences

Humanities education represents a shared theme in medical and health humanities scholarship. Whereas medical humanities education targets medical students, doctors, and patients, health humanities education encompasses three distinct cohorts: patients; health care workers such as nurses and health professionals; and groups in the general public, notably elderly adults, women, and children. Health humanities distinctly expand their focus beyond the patient-centred scope of medical humanities to encompass broader public audiences.

The medical humanities curriculum is relatively fixed, whereas the health humanities curriculum is open-ended

The medical humanities movement has led to foregrounding the salience of arts and the humanities in medical education, and it has explored how medicine and its work can be inflected by these, for example, through the study of the history of medicine, philosophy of medicine, anatomical drawing, ethics, literature and drama (Crawford and Brown, 2020). Gradually, these humanities disciplines have become an important part of the curriculum in medical education. Although there is no uniformity in the provision of medical humanities programmes across institutions, there is a relatively high degree of consensus. For example, the three most common medical humanities disciplines in the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada are history, literature/narrative medicine and the arts (Howick et al., 2022). Evans (2004) suggested that medical humanities as a field of study should be interdisciplinary, but true interdisciplinarity is difficult to achieve. The current medical humanities are a collection of multidisciplinary disciplines, and at this stage, they should be referred to in the plural. Medical humanities programmes have not yet formed a coherent system. This is largely due to the relatively independent nature of each discipline’s contribution to medical education and research. That is, they remain multidisciplinary in form rather than integrated.

Figure 5 reveals minimal differentiation in curricular content between health humanities education and medical humanities education. One of the earliest explicitly global health humanities courses, Humanities in Global Health, was introduced in 2012 as a component of the Global Health BSc programme at Imperial College London, UK (Stewart and Swain, 2016). Beyond this course, few formal health humanities courses exist that parallel medical humanities’ established elective or compulsory offerings. Some institutions deliver health humanities projects, providing participants with perspectives such as historical, ethical, literary/cultural, and community-engaged frameworks, as exemplified by courses such as Chronic Illness and Self-Care, Narratives of Disability, and Medicine, Health, and Literature under literary and cultural perspectives (Hausman et al., 2023). We contend that health humanities curricula exhibit an open-ended nature, epitomised by the Health Humanities Consortium (HHC), an organisation dedicated to resourcing individuals and institutions developing health humanities courses (Klugman and Jones, 2021). The HHC further launched the Health Humanities Syllabus Repository, a novel resource for medical/health humanities educators, while actively inviting field members to contribute their syllabi.

Medical humanities primarily operate within clinical settings, whereas health humanities engage predominantly in community contexts

The practice of medicine is a profoundly social enterprise, and the values that inform medical practice are highly important (Halperin, 2010). In terms of practical application, Berwick et al. (2008) proposed an important framework for improving the health care system in their research, namely, the “Triple Aim”, which aims to improve the patient experience of care, improve the health of the population and reduce the per capita cost of health care. This concept not only indicates the direction of medical education but also provides a blueprint for clinical practice. The applied concepts (Zhang, 2021) of medical humanities mainly include professional spirit, humanistic care, medical decision-making, doctor–patient communication, empathy, patient-centred, etc. These concepts together constitute the core of medical humanities in clinical practice. However, this content alone can only achieve the goal of “improving the individual experience of care” because the attention of medical humanities education to public health and the burden of disease is still insufficient at this stage. To achieve the second goal of improving the level of health of the population, the perspective of medical humanities needs to be further broadened, and the focus of research and practice should be shifted to broader public health issues such as disease prevention, health promotion and community health improvement. The advantages of health humanities are increasingly apparent in this context. As shown in Fig. 5, health humanities practices are closely aligned with primary health care. This field distinguishes itself through stronger practical engagement, extending beyond the treatment of individual diseases to enhance community-wide health by optimising lifestyle choices, improving environmental conditions, and promoting healthier behaviours.

Whilst medical humanities and health humanities share common research themes—such as humanitarian assistance, public health, and mental health—they exhibit differential emphasis in addressing these areas. Each discipline engages with these themes through distinct conceptual perspectives and problem-solving orientations.

Medical humanities and health humanities interventions have different timescales in regard to humanitarian assistance

Humanitarian assistance represents a shared concern within both medical and health humanities. This field is characterised by a profound commitment to preserving life, coupled with an emphasis on safety and security—values that are central to both disciplines. While rooted in empathy for human suffering and a shared dedication to improving quality of life, distinct approaches emerge between the two fields. Medical humanities focus predominantly on the provision of medical aid during disasters, including surgical interventions, injury diagnosis, and acute treatment (Dolinskaya et al., 2018). In contrast, health humanities prioritise post-disaster refugee welfare, addressing issues such as water supply, food security, and women’s reproductive health, including pregnancy care (Brown et al., 2020). It follows that in humanitarian assistance, medical humanities ensure the humanisation and ethical underpinnings of medical practice, whereas health humanities work to break down structural inequalities and promote sustainable health equity.

Medical Humanities pays insufficient attention to public health and global health

This study found that there are fewer public health-related studies in medical humanities research, and no corresponding themes have been developed. COVID-19 is a public health event that was relevant to medical humanities. In the process of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, although both medical humanities and health humanities were concerned with human health, there were some differences in their perspectives. COVID-19 is classified as a humanitarian assistance theme in medical humanities research, which to some extent indicates that medical humanities focused more on the individual level of care, ethical decision-making and patient narratives in the this pandemic. In health humanities research, the “global health humanities” (Hassan and Howell, 2022) and “planetary health humanities”(Lewis, 2021) concepts suggest that health humanities are closely linked to global health. The health humanities are concerned not only with public health emergencies caused by infectious diseases but also with climate change, environmental health, food security, health equity and other health issues.

The different dimensions of medical and health humanities in relation to mental health: alleviating distress and promoting well-being

The categorisation of the research themes reveals some differences in focus on mental health between the medical and health humanities, i.e. they have different starting points. The starting point is different. Medical humanities focus on the mental health problems of refugees in humanitarian disasters, alleviating the anxiety and depression caused by trauma. In contrast, the field of health humanities establishes a connection between mental health and well-being, underscoring its intrinsic relationship with overall life satisfaction.

From a cost-effectiveness perspective, health humanities practice represents the most economical approach to promoting population health

Research on the economic burden of health care can be divided into studies from a population perspective and an individual perspective. Population-based studies focus on the economic costs to society and the health resources consumed in the fight against disease, as well as epidemiological studies on the economic burden of the whole population (Ding et al., 2016). At the individual level, studies focus on the economic burden of a disease on an individual or a family (Palli et al., 2021). Expertise in health economics is essential when studying the economic burden of disease. However, the current field of medical humanities research has not extensively addressed this dimension, resulting in an under-representation of economic factors in relevant studies. As an extension of medical humanities, health humanities have begun to emerge, with studies focusing on economic burden. Health economics has theories and methods that are important for multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research in medical humanities and health humanities. Integrating the theory and practice of health economics into the research framework of medical and health humanities not only enriches research in these fields but also may become a hot area for future research. Thus, future research trends are likely to involve a deeper integration of medical and health humanities with health economics to fully understand and address the economic burden of disease.

Health humanities should be applied to social justice issues: health disparities

Educators increasingly recognise the need to transcend the empathy and wellness frameworks, applying health humanities to address social justice issues (Mathieu and Martin, 2023). Social determinants of health (SDOHs) are factors determined by social structures and environmental conditions that are beyond an individual’s control, that influence the health status of an individual or group, and that are at the root of health disparities/inequalities (used interchangeably here) (Braveman, 2006). Taking lifestyle and behaviour as an example, health literacy directly affects a person’s lifestyle and behaviour. Health literacy is one of the SDOHs. All reported national population surveys have revealed a social gradient in health literacy, indicating that health literacy is associated with social and economic conditions (Nutbeam and Lloyd, 2021). The evidence indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only revealed existing health disparities but also intensified them (Jensen et al., 2021). Data from studies have demonstrated that older individuals and those with pre-existing health conditions are more vulnerable to the virus (Guan et al., 2020). It is valuable to consider that even though medical humanities do not encompass related research, this theme has emerged at the intersection of medical humanities and health humanities. This finding indicates that we can reduce health inequalities and enhance health outcomes for all by harmonising the functions of medical humanities and health humanities.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that medical humanities focus on disease as their core thematic concern, with physicians and patients constituting their primary demographic focus, and the physician-patient relationship forming their fundamental relational framework. In contrast, health humanities have expanded their scope from disease studies to encompass the broader public health domain. Its purview now extends across the entire healthcare industry chain, addressing not only health itself but also socio-political, economic, and cultural determinants of health. Furthermore, across multiple healthcare contexts—including humanitarian assistance and mental health issues—medical humanities and health humanities exhibit complementary perspectives. Their relationship is characterised by coexistence rather than substitution. Ultimately, as complementary humanities governance paradigms within medicine and health, these fields’ synergistic development proves essential for effectively serving the well-being of all humanity.

Limitations

This study acknowledges its methodological limitations. First, the exclusive reliance on WOS-derived data—prioritised for their authoritative and high-quality standards—risk excluding relevant literature from other databases. Second, while the visualisation outputs generated through VOSviewer are objectively derived, their interpretation remains vulnerable to subjective influences, as observers may analyse identical visualisations through disciplinary or cognitive biases, thus producing subjectively framed conclusions. Furthermore, the dependence on keyword-based analysis likely omits thematically pertinent articles lacking keyword metadata, potentially compromising the accuracy of the research findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aghajafari F, Wall L, Weightman A et al (2024) COVID-19 vaccinations, trust, and vaccination decisions within the refugee community of Calgary, Canada. Vaccines 12:177. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12020177

Alimadadi A, Aryal S, Manandhar I et al (2020) Artificial intelligence and machine learning to fight COVID-19. Physiol Genom 52:200–202. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00029.2020

Allsopp G (2020) Medicine within health humanities. In: The routledge companion to health humanities. Routledge, Abingdon, p 66

Anker SD, Agewall S, Borggrefe M et al (2014) The importance of patient-reported outcomes: a call for their comprehensive integration in cardiovascular clinical trials. Eur Heart J 35:2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu205

Aristovnik A, Ravšelj D, Umek L (2020) A bibliometric analysis of COVID-19 across science and social science research landscape. Sustainability 12:9132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219132

Beauchamp TL (2019) A defense of universal principles in biomedical ethics. In: Valdes E, Lecaros JA (eds) Biolaw and policy in the twenty-first century: building answers for new questions. Springer International Publishing AG, Cham, pp 3–17

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J (2008) The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff 27:759–769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

Braveman P (2006) Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health 27:167–194. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103

Brown CM, Swaminathan L, Saif NT, Hauck FR (2020) Health care for refugee and immigrant adolescents. Prim Care 47:291–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2020.02.007

Caplan AL (1992) Does the philosophy of medicine exist? Theor Med 13:67–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00489220

Charon R (2001) Narrative medicine—a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. J Am Med Assoc 286:1897–1902. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Chen W, Sa RC, Bai Y et al (2023) Machine learning with multimodal data for COVID-19. Heliyon 9:e17934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17934

Chen X, Li H, Lucero-Prisno DE et al (2020) What is global health? Key concepts and clarification of misperceptions: report of the 2019 GHRP editorial meeting. Glob Health Res Policy 5:. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00142-7

Chisolm MS, Kelly-Hedrick M, Wright SM (2021) How visual arts-based education can promote clinical excellence. Acad Med 96:1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003862

Cho G, Park JR, Choi Y et al (2024) Detection of COVID-19 epidemic outbreak using machine learning. Front Public Health 12:1381284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1381284

Crawford P, Brown B (2020) Health humanities: a democratising future beyond medical humanities. In: Bleakley A (ed) Routledge Handbook of the Medical Humanities. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 401–409

Crawford P, Brown B, Tischler V, Baker C (2010) Health humanities: the future of medical humanities? Ment Health Rev J 15:4–10. https://doi.org/10.5042/mhrj.2010.0654

Crawshaw AF, Farah Y, Deal A et al (2022) Defining the determinants of vaccine uptake and undervaccination in migrant populations in Europe to improve routine and COVID-19 vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 22:E254–E266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00066-4

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL et al (2016) The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 388:1311–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X

Dolinskaya I, Besiou M, Guerrero-Garcia S (2018) Humanitarian medical supply chain in disaster response. J Humanit Logist Supply CHAIN Manag 8:199–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-01-2018-0002

Dooley-Clarke D (1982) A philosophical basis of medical practice. J Med Ethics 8:160–161. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.8.3.160-a

Duan Z (2017) Comprehensive health humanities: the future of medical humanities and health humanities. Med Philos 38:6–9. https://doi.org/10.12014/j.issn.1002-0772.2017.06a.02

Engel G (1977) Need for a new medical model—challenge for biomedicine. Science 196:129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Evans HM, Macnaughton J (2004) Should medical humanities be a multidisciplinary or an interdisciplinary study? Med Humanit 30:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmh.2004.000143

Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382:1708–1720. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Halperin EC (2010) Preserving the humanities in medical education. Med Teach 32:76–79. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421590903390585

Hassan N, Howell J (2022) Global health humanities in transition. Med Humanit 48:133–137. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2022-012448

Hausman BL, Jaros P, Stone J et al (2023) Creating health humanities programs at liberal arts colleges: three models. J Med Humanit 44:107–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-022-09778-7

Hoang G, Erickson R (1982) Guidelines for providing medical-care to Southeast Asian refugees. J Am Med Assoc 248:710–714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.248.6.710

Howick J, Zhao L, McKaig B et al (2022) Do medical schools teach medical humanities? Review of curricula in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. J Eval Clin Pract 28:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13589

Isaac M (2023) Role of humanities in modern medical education. Curr Opin Psychiatry 36:347–351. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000884

Jensen N, Kelly AH, Avendano M (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for an equity-focused global health agenda. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00700-x

Jones T, Blackie M, Garden R, Wear D (2017) The almost right word: the move from medical to health humanities. Acad Med 92:932–935

Klugman CM, Bracken RC, Weatherston RI et al (2021) Developing new academic programs in the medical/health humanities: a toolkit to support continued growth. J Med Humanit 42:523–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-021-09710-5

Klugman CM, Jones T (2021) To be or not: a brief history of the health humanities consortium. J Med Humanit 42:515–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-021-09712-3

Kraemer A, Fischer F (2018) Recommendations for academic profiling of global public health in Germany. Gesundheitswesen 80:642–647. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-101516

Kwame A, Petrucka PM (2021) A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs 20:158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2

Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N et al (2018) Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001271. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3

Leipert BD (1996) The value of community health nursing: a phenomenological study of the perceptions of community health nurses. PUBLIC Health Nurs 13:50–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00218.x

Lewis B (2021) Planetary health humanities-responding to COVID times. J Med Humanit 42:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-020-09670-2

Mathieu IP, Martin BJ (2023) The art of equity: critical health humanities in practice. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 18:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13010-023-00149-1

Moniz T, Golafshani M, Gaspar CM et al (2021) How are the arts and humanities used in medical education? Results of a scoping review. Acad Med 96:1213. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004118

Nutbeam D, Lloyd JE (2021) Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. In: Fielding JE (ed) Annual review of public health, vol 42. Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, pp 159–173

Onen CL (2004) Medicine in resource-poor settings: time for a paradigm shift? Clin Med 4:355–360. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.4-4-355

Osler W (1919) The old humanities and the new science. Br Med J 2:1–7

Palli A, Peppou LE, Economou M et al (2021) Economic distress in families with a member suffering from severe mental illness: illness burden or financial crisis? Evidence from Greece. Community Ment Health J 57:512–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00674-9

Ruger JP (2012) Global health justice and governance. Am J Bioeth 12:35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2012.733060

Slade M (2010) Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv Res 10:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-26

Squier SM (2007) Beyond nescience—the intersectional insights of health humanities. Perspect Biol Med 50:334–347. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2007.0039

Standring S (2016) A brief history of topographical anatomy. J Anat 229:32–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12473

Stewart KA, Swain KK (2016) The art of medicine Global health humanities: defining an emerging field. Lancet 388:2586–2587. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32229-2

van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84:523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Vevaina J, Nora L, Bone R (1993) Issues in biomedical ethics. Dis–Mon 39:873–925

Vlase I, Laehdesmaeki T (2023) A bibliometric analysis of cultural heritage research in the humanities: the Web of Science as a tool of knowledge management. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:84. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01582-5

Wang C, Chen X, Yu T et al (2024) Education reform and change driven by digital technology: a bibliometric study from a global perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:256. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02717-y

WHO WHO called to return to the Declaration of Alma-Ata. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/declaration-of-alma-ata. Accessed 25 May 2025

WHO (1986) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/349652. Accessed 4 Nov 2024

WHO (2023) Human rights. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health. Accessed 11 Nov 2024

Yang Y, Tan X, Shi Y, Deng J (2023) What are the core concerns of policy analysis? A multidisciplinary investigation based on in-depth bibliometric analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:190. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01703-0

Zhang DQ (2015) Three waves of medical humanities. Med Philos 36:31–35, 62

Zhang J, Lu ZX, Duan ZG (2013) A study on the accuracy of Keywords Plus in the Web of Science database: taking patient compliance research papers as an example. Paper presented at the 1st Cross-Strait Symposium on Scientometrics and Informetrics, Xi´an, China

Zhang XQ (2021) The logic of the construction of medical humanities. Chin Med Humanit 7:16–19

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by The First Batch of New Liberal Arts Research and Reform Projects of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (NO. 2012020012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C Wang wrote the main manuscript text; Y Shi and HQ Guo were responsible for the data screening and analysis; RD Tian, D Luo and N Zhang were responsible for bibliographic retrieval, and ZG Duan was responsible for reviewing and guiding the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statements

Not applicable because the research did not involve human participants or their data.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Shi, Y., Guo, H. et al. How medical humanities and health humanities should get along: a keyword co-occurrence analysis of the literature. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1522 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05811-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05811-x