Abstract

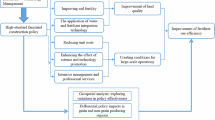

The application of fertilizer is an important means of farmland management in both the past and the modern society, which is of great significance to increase food yield and improve soil structure to achieve sustainable development. Even in modern agriculture, how to scientifically and effectively apply fertilizers while reducing environmental pollution is still a key problem to be solved. China has a long history of farmland management theory and practical experience, and offers valuable insights through historical literature. Although research has revealed manuring practices across regions like Europe, Asia, and Africa since the Neolithic periods, the guiding principles remain insufficiently understood. Here we examine Chinese fertilization-related texts, highlighting principles of past fertilization according to time, soil, crops, and human effort, anchored in the San Cai theory (Heaven, Earth, and Humanity). Ancient farmers had already understood the importance of applying targeted fertilizers at different stages of crop cultivation and adjusting fertilizer application based on seasonal rhythms. They knew how to apply fertilizers according to the soil characteristics influenced by both zonal and non-zonal factors, and could adjust fertilizer types and application techniques to suit the specific needs of different crops. Over time, the role of humanity within the fertilization system became increasingly emphasized, encompassing both human labor and the harmonious unity between individuals and society. This reflects the deepening integration of the San Cai fertilization framework. By revisiting these practices, this study helps fill the gaps in our understanding of prehistoric land management and provides valuable insights for advancing sustainable agricultural development in diverse ecological and cultural contexts. The emphasis on organic fertilizers, nutrient cycling, and soil conservation in ancient China presents a sustainable model for contemporary agriculture, offering more eco-friendly and efficient solutions to issues such as soil degradation, nutrient imbalances, and the overuse of chemical fertilizers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the last Ice Age, climatic changes have significantly impacted human activity patterns and living conditions (Li, 2022). Agriculture has gradually emerged as the principal economic activity driving human survival and development. Agriculture’s development, as a process of adaptation to and transformation of the natural environment, reflects the evolving human-environment relationship and its underlying mechanisms (Xia and Zhang, 2019), while also embodying historical wisdom about achieving harmony and unity between humans and nature (Guo et al. 2016). Under the background of climate and environmental changes, the adaptation strategies and processes employed by humans in agricultural activities have become a focal point for scholars in archaeology, agronomy, and related fields.

Extensive research indicates that effective farmland management is essential for achieving sustainable agricultural development (Jin et al. 2024; Styring et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2022). Recently, techniques such as stable isotope analysis, soil micromorphology, and weed ecology have become pivotal tools for uncovering ancient agricultural practices, including manuring and irrigation strategies (Bogaard, 2004; Bogaard et al. 2013; Canti, 1997; Yang et al. 2022). Significant advancements in understanding fertilization practices and their effects on social complexity across Europe, West Asia, West Africa, and East Asia have emerged from modern planting experiments (An et al. 2015; Bogaard et al. 2013; Ouyang et al. 2024; Styring et al. 2016; Styring et al. 2017; Styring et al. 2019). These studies reveal that by 5900 BC, European farmers had integrated intensive manuring with livestock breeding, playing a pivotal role in the expansion of mixed farming, pastoral livelihoods, and the social differentiation of agricultural communities (Bogaard et al. 2013). Manuring was integral to agricultural strategies in northern Mesopotamia during the seventh millennium BC, supporting early urban development through extensive cultivation methods that involved larger land areas with lower manure inputs per unit area (Styring et al. 2017). Furthermore, manuring practices were evident in the cultivation of pearl millet in West Africa from AD 500 to 1150(Styring et al. 2019).

In East Asia, research has predominantly focused on China. Approximately 6000 years ago, millet-based rain-fed agriculture, featuring indigenous crops such as foxtail and broomcorn millet, became firmly established in northern China (Zhao, 2019), coinciding with the flourishing Yangshao culture and a significant expansion of population and cultural distribution (Han, 2015). However, the Loess Plateau, where the Yangshao Culture thrived, is characterized by widely distributed yellow loam soil with a shallow plough layer, poor fertility, low organic matter content, and nitrogen deficiency (Soil Survey Office of Shaanxi Province, 1992; The Scientific Investigation Team of the Loess Plateau, 1992). Research indicates that an intensive agricultural system integrating millet cultivation with pig husbandry developed in northern China around 5500 BP (Yang et al. 2022). Manuring played a crucial role in expanding millet agriculture, supporting population growth, and fostering the development of the Yangshao Culture during the late Neolithic period (Wang et al. 2018). Since the Bronze Age, the manuring practices of ancient Chinese farmers have been meticulously documented in texts such as The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) and Qi Min Yao Shu (齐民要术), which serve as significant records of China’s enduring manuring history.

In contemporary agriculture, fertilizers are indispensable materials for production. The excessive use of chemical fertilizers in modern agricultural practices has resulted in significant issues, including resource wastage, soil compaction, and environmental pollution, which have attracted growing attention (He et al. 2006; Sims et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2010). Numerous studies have demonstrated that organic fertilizers play a crucial role in enhancing crop yields, preserving biodiversity, and reducing net carbon emissions (Liu et al. 2024; Qian et al. 2023; Shi et al. 2024; Tian et al. 2022). Before the advent of chemical fertilizers, ancient farmers primarily relied on organic fertilizers. What principles guided their fertilization practices? What philosophical concepts underpin these methods? Addressing these questions is essential for understanding prehistoric manuring practices worldwide, where written records are limited, and may also provide valuable insights for the development of global sustainable agriculture today.

Ancient Chinese philosophers referred to heaven, earth, and humanity as San Cai (三才), a concept integral to understanding the relationship among all entities in the world. The San Cai theory, elaborated in the Zhou Yi (周易), posits that heaven, earth, and humanity are the three fundamental components of the universe, expressed through the concepts of 天时、地利、人和 (favorable climatic, geographical, and human conditions). This framework, which also extends to Three Appropriateness (三宜, adaptation to time, soil, and crops), profoundly influenced agricultural practices and has guided traditional Chinese farming, either consciously or unconsciously, over millennia (Jin and Lü, 2016). This concept of harmony between human activity, natural conditions, and crops provided essential guidance for diverse agricultural environments across China (Wang, 2024).

The San Cai theory forms the foundation of Chinese agricultural philosophy, facilitating the development of traditional agriculture as central to Chinese thought (Li, 1997). By the end of the Warring States period, the theory’s influence was evident in works like Lü Shi Chun Qiu (吕氏春秋), where texts such as Shen Shi highlighted the interconnected roles of humanity, land, and heaven in farming. In this text, it is stated that “Farming is carried out by humans, nourished by the land, and sustained by the heavens,” emphasizing human activity, soil understanding, and the importance of climatic conditions (Lü, 2011). Under the San Cai framework, humanity serves as the primary force in agricultural production, while crop properties provide the foundation for farming practices. Mastery of these properties, along with an understanding of favorable climatic and geographical conditions, is essential for achieving harmony between heaven, land, and crops. The interplay of human labor, crop growth, and the environment forms the “Green Triangle” (Guo, 1992), which drives the “Three Appropriateness,” requiring coordination of time, soil, and crops for optimal agricultural production.

Ancient China boasts a long history of fertilization practices. According to the interpretations of oracle bone inscriptions by oracle bone scholars, as early as the Shang Dynasty, there were expressions such as 屎西单田 and 屎有足, 乃贵田. These phrases referred to the practice of applying manure to farmland, followed by plowing and weeding to enhance soil productivity (Hu, 1981). By the Spring and Autumn period, philosophers like Xun Zi (荀子) emphasized that proper fertilization could lead to substantial agricultural yields, with the responsibility of applying fertilizers lying with the farmers (Xun, 2015). Han Feizi (韩非子) further supports this by noting that the application of manure and irrigation was essential for successful farming (Han, 2010). In ancient China, the term 粪 (dung) was used to describe various types of manure, including human and animal excrement, as well as green manures such as 苗粪 (seedling manure) and 草粪 (grass manure). The act of manuring fields was also called 粪田 or 壅田 (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences et al. 1985). The application of manure was critical to agricultural productivity, adhering to the principle of “Three Appropriateness” in farming practices. Ancient texts advocate applying fertilizers at the right time, based on soil conditions, and according to the specific needs of crops (Chen, 2015; Wang, 1957). This approach ensures the harmony of time, land, humanity, and crops, promoting sustainable agricultural success.

Current research on ancient Chinese fertilization primarily focuses on general historical overviews (Cao, 1984) or specialized studies of fertilization techniques in specific periods (Du, 2018; Zhou, 2006). However, there is still a lack of comprehensive studies that examine the history of Chinese fertilizers and their cultural connotations from an integrated perspective. As a result, our understanding of the cultural philosophy and practical wisdom behind the ancient fertilization system remains underdeveloped. Ancient Chinese fertilization was not just a technical operation, but deeply rooted in the ancestors’ respect and understanding of the harmonious unity between heaven, earth, and humanity. The San Cai theory exactly provides such a perspective, reflecting the relationships between different elements of agricultural production from the levels of heaven, earth, and humanity, which helps further understand the internal logic and cultural connotations of the ancient fertilization system. Therefore, this paper adopts the perspective of the San Cai theory and systematically examines the fertilization practices of ancient Chinese ancestors based on rich literature records, aiming to enrich the understanding of ancient Chinese farming systems and provide insights into the agricultural management practices of prehistoric societies and contemporary sustainable agricultural development.

Methods

This study adopts a qualitative research approach based on historical literature, exploring ancient Chinese fertilization practices within the framework of the San Cai theory. By comprehensively reviewing and integrating agricultural-related historical literature, the study focuses on philosophical concepts, primarily the diachronic changes in fertilization practices centered around the San Cai theory, and the interrelationship between fertilization and crop growth. The research methods include:

Literature review

Original sources, including classical agricultural texts such as Qi Min Yao Shu (齐民要术), The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书), and Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书), were examined to investigate historical fertilization practices. Secondary sources provided additional reference information, focusing on the development of agricultural philosophy and the important role of the San Cai theory in fertilization practices.

Thematic categorization

The reviewed materials were categorized into themes including the adaptation of fertilization to time, land, and crop characteristics. Key principles from the San Cai theory, such as the harmony between heaven, earth, and humanity, were identified as core guiding factors in ancient manuring practices.

Comparative analysis

This involved comparing fertilization practices across different historical periods and regions, including assessing how ancient farmers adjusted their practices in response to environmental conditions, population growth, and agricultural demands, with a particular focus on the role of the San Cai theory in shaping fertilization techniques.

Synthesis of findings

The findings were synthesized to identify fertilizer application patterns based on soil characteristics, crop needs, and climatic rhythms. This comprehensive analysis highlighted the dynamic relationship between environmental factors, human labor, and agricultural output; it also interpreted ancient fertilization practices within the context of archaeological research and modern sustainable agriculture, exploring how ancient fertilization wisdom, especially the San Cai theory, contributes to a comprehensive understanding of ancient land management and offers contemporary solutions for issues such as soil degradation and the overuse of chemical fertilizers.

Manuring adapting to the time

Crops are intricately interconnected with shifts in the natural environment. Throughout the historical development of agriculture, Chinese farmers consistently emphasized that agricultural production should 不违农时(not violate the farming time). Lü Shi Chun Qiu (吕氏春秋) states, “The wise value timing above all else. When water is frozen and the ground is hard, even Hou Ji(后稷) refrains from sowing. His sowing must await spring” (Lü, 2011), underscoring the need for agricultural production to align with natural laws. The principle of “not violating the farming time” underscores the necessity of adhering to the entire crop cultivation process, including seed preparation, sowing, growth management, and harvest and storage. The application of fertilizer, spanning the entire cultivation process, highlights the ancient peoples’ profound understanding of the significance of the farming time and their wisdom in adapting to it.

Manuring at different steps of crop cultivation

In relation to the specific operational steps taken in crop cultivation, such as seed preparation, sowing, irrigation, weeding, and other agricultural techniques, fertilizers are categorized into seed fertilizers, base fertilizers, and topdressing fertilizers. These categories represent the application of fertilizers at different stages of the cultivation process. Each of the three fertilization methods serves a distinct purpose and they interact with each other.

Seed fertilizer involves applying fertilizer near or mixing it with seeds during sowing, with the goal of establishing optimal nutritional and environmental conditions for seed germination and growth (Tan and Han, 2021). The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) from the Western Han Dynasty records various methods for seed fertilizer, such as soaking seeds in a mixture of bone broth and manure or immersing wheat seeds in sour liquid combined with silkworm droppings (Shi, 1956). Similarly, Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) from the Southern Song Dynasty describes a process of clearing the soil, burning ashes, sifting through husks and chaff, gathering straw and leaves, burning them, and using manure liquid to water the ashes. The finest ash is mixed with seeds and scattered lightly, ensuring the seeds remain pest-free and promoting better yields (Chen, 2015). The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) also describes a fertilizing method called 溲种法: “Crush horse bones, boil one part of bone with three parts of water, boiling three times. Filter out the residue, soak five pieces of aconite for three to four days, then remove it, and mix the liquid with equal parts of silkworm and sheep droppings, stirring until the mixture resembles thick porridge. This method prevents locust infestations, resists drought, and doubles the usual harvest” (Shi, 1956). The broth extracted from horse bones is processed several times and blended with silkworm droppings and sheep manure to create a thick porridge-like mixture, which is repeatedly applied to the seeds before planting. This method prevents insect damage, mitigates drought effects, and enhances crop yield. In modern agriculture, seed coatings are widely used, typically water-soluble and containing fast-acting fertilizers and hormones (Zhu, 1983).The effects of 溲种法 are comparable to those of modern seed coatings, as both methods facilitate rapid absorption of water and nutrients by seeds.

Base fertilizer is incorporated during tillage preparation. The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) records: “In each field block, plant four grains. Mix one dou (斗) of silkworm droppings with soil manure” (Shi, 1956), indicating that silkworm manure and soil manure are mixed as base fertilizer in field planting.Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) mentions that rice fields should be cultivated before sowing: “In early spring, plow and harrow the field again, fertilize it thoroughly, and prepare the soil. Then apply husk manure, tread it into the mud, level the field, and finally sow the grain seeds” (Chen, 2015). Fertilizer should be applied at least twice before sowing, reflecting the refinement of base fertilizer application practices. The Book of Bao Di Quan Nong (宝坻劝农书) from the Ming Dynasty elaborates on the importance of base fertilizer application based on crop nutrient absorption characteristics: “Base manure is applied deep in the soil, encouraging deeper root growth, while surface manure causes roots to grow upwards. Skilled farmers apply manure during plowing and avoid fertilizing after sowing” (Wang, 2024). The comparison between 基肥 (base manure) applied in the initial planting stage and 追肥 (relay manure) emphasizes the importance of paying attention to base fertilizer. Yang Shen(杨屾) in the Qing Dynasty further proposed the theory of 胎肥祖气 (foundation fertilizers and core vitality) in Zhi Ben Ti Gang (知本提纲), stating: “Foundation fertilizers nurture the plant’s core vitality, while superficial fertility leads to excessive leaf growth without substance” (Wang, 1957). He argued that applying only topdressing, without base fertilizer, would result in excessive leaf growth and poor seed harvests. Ancient agricultural texts emphasize that base fertilizer was the most used, typically consisting of human and animal dung and green manure, which required long decomposition times and slow fertilizer release. These characteristics made base fertilizer essential for supporting long-term crop growth, thus receiving the most attention in ancient agricultural practices.

Topdressing refers to fertilizers applied during crop growth. While ancient agricultural texts record fewer references to topdressing compared to base fertilizers, The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) notes: “When a sapling is one foot tall, fertilize it with three liters of silkworm droppings. If unavailable, one liter of well-rotted manure from latrines will also suffice” (Shi, 1956). This suggests that topdressing, typically applied during hemp planting, can involve silkworm droppings or decomposed human dung. From a crop growth perspective, when hemp reaches one foot in height, it is the critical period for fertilization. The silkworm droppings and decomposed human dung used are fast-acting fertilizers, making the fertilization effect generally ideal. Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) also contains numerous references to topdressing. After the Song and Yuan Dynasties, records of topdressing increased significantly (Table 1), but its importance was still considered secondary to that of base fertilizer. In Bu Nong Shu (补农书), it is recorded: “If ashes are added after the bean seedlings have grown, they stick to the leaves and scatter around, failing to reach the roots. This is no different from not applying ashes at all” (Wang, 2024). This highlights the concern that topdressing may not be absorbed by the roots. In Zhi Ben Ti Gang (知本提纲), author Yang Shen compares topdressing with base fertilizer to emphasize the importance of base fertilizer (Wang, 1957).

Although ancient farmers did not place as much emphasis on topdressing as on base fertilizers, the differentiated nutrient requirements of crops at different growth stages did affect crop yields. Through long-term practice, ancient farmers gained more detailed experiential knowledge regarding topdressing. Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书), written during the Ming Dynasty, states that fertilization should occur after the “Limit of Heat” (处暑), when seedlings are forming buds (作胎) and turning yellow: “If the seedlings are not yellow, do not apply fertilizer. For dense but weak seedlings, apply three dou (斗) of cake fertilizer per acre after the ears emerge. Fertilizing too early results in healthy seedlings but poor rice yields” (Wang, 2024).The term 作胎 refers to the differentiation stage of young crop ears, a phase that demands the highest amounts of fertilizer and water (Min, 1992). The nutritional condition of crops is indicated by the color of the seedlings, making it essential to observe the seedlings before applying fertilizer. Nong Sang Yi Shi Cuo Yao (农桑衣食撮要) from the Yuan Dynasty also describes the practice of topdressing outside the root: “Once new leaves appear, perform weeding and apply ash early in the morning when dew is present. Repeat weeding and fertilization twice” (Lu, 1985).This indicates that after the crop’s stems and leaves have developed, fertilizers such as grass and wood ash are applied to the stems and leaves, in addition to other fertilizers applied to the soil. Modern research shows that applying fertilizer to the crop’s leaf surface promotes rapid nutrient absorption, reduces the risk of lodging, and enhances yield (Lin, 1993). This demonstrates a significant innovation in ancient fertilization techniques, reflecting a deeper understanding of crop growth stages by farmers of the time.

In summary, base fertilizers, seed fertilizers, and topdressing fertilizers, as the three fertilization methods in the crop cultivation process, reflect the systematic nature of fertilization techniques. The more refined practices of topdressing also reflect the ancient farmers’ deeper understanding of the specific physiological changes in crops throughout their life cycle. These practices clearly exemplifying the principle of “manuring adapting to the time” in crop cultivation.

Manuring according to climate rhythm

China, located in a typical monsoon climate region, is significantly affected by climate change, particularly through the timing of shifts in climate and high variability in precipitation, which impact crop growth. Moreover, climate change also influences fertilization practices.

In response to extreme conditions such as low temperatures, drought, and frost, ancient farmers adapted their fertilization practices accordingly. For instance, Feng Rubi (冯汝弼) of the Ming Dynasty, in You Shan Za Shuo (祐山杂说), summarized the principle of avoiding excessive fertilization during prolonged droughts, noting that “intense heat and moisture can cause the soil to rot, and excess fertilizer will exacerbate this issue” (Feng, 1985). Regarding the replanting of rice after a flood, Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书), advises: “As long as the fields are free of weeds, do not overwork or over-fertilize. Excessive fertilization leads to excessive branch growth, delaying the development of rice heads and resulting in plants with heads but no grain. Exercise caution” (Wang, 2024). From the perspective of rice growth, replanting occurs later in the season, and if fertilization delays ear formation, low temperatures may prevent seed setting. During the Qing Dynasty, Nong Yan Zhu Shi (农言著实) focused on the fertilization of wheat crops in the Guanzhong region, advising that fertilization should be adjusted based on climate and weather conditions: “Apply surface manure, and additional fertilizer can be applied once the ground freezes.” In the absence of rainfall, fertilization should be avoided, as “On elevated land with strong winds and intense sunlight, floating manure would be wasted, as it could be blown away or evaporate” (Yang, 1957). In cotton cultivation along the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, farmers implemented measures to prevent cotton roots from freezing during cold spells. Xu Guangqi (徐光启), in Nong Zheng Quan Shu (农政全书) during the Ming Dynasty, advised that “After plowing in late winter or early spring, sow a few liters of barley per acre. Before planting cotton, turn the soil to cover the barley seedlings. The barley roots protect the cotton roots from the cold, allowing for earlier planting by 10–15 days” (Xu, 1979). That is, barley is typically sown at the end of winter or early spring, and after harvesting and soil preparation, cotton can be planted, as it is known to be cold-resistant.

The seasons and solar terms (节气) are crucial factors in agricultural production, following the principle of 春生、夏长、秋收、冬藏 (spring birth, summer growth, autumn harvest, winter storage). Manuring practices are also influenced by seasonal rhythms. Wu Xing Zhang Gu Ji (吴兴掌故集) from the Ming Dynasty records: “Experienced farmers advise against fertilizing too early, as it can cause stunted ears by autumn. Use river mud at planting for slow, lasting effects. Apply ash or cake fertilizer in midsummer for gradual benefits. Apply heavy fertilizer between the Start of Autumn (立秋) and End of Heat (处暑) for stronger, longer rice ears” (Xu, 1560). By aligning the growth and development stages of rice with fertilizer characteristics, it is recommended that various types of fertilizers be applied during different solar terms. Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书) discusses the seasonal application of fertilizers for mulberry trees (Wang, 2024), dividing it into three periods: winter, spring, and summer. Applying river mud before spring nourishes the soil, supporting winter buds. Around Qingming (清明), apply human manure to boost mulberry leaf growth (Zhang, 1989). Yang Shen also pointed out in Zhi Ben Ti Gang (知本提纲) that fertilization practices vary by season: “Use human and animal manure in spring, grass and mud manure in summer, fire ash in autumn, and bone, shell, or fur manure in winter” (Wang, 1957), emphasizing that different fertilizers are suited for different seasons.

Manuring adapting to the land

Variations in land location, terrain elevation, and soil moisture significantly impact plant growth. Natural environmental conditions vary across regions, leading to different inputs of light, heat, water, gases, and nutrients into agricultural systems. According to Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) from the Southern Song Dynasty, people in the Xia Dynasty(2070BC-1600BC) were taught to recognize differences in land elevation and soil fertility (Chen, 2015). Recognizing regional land differences requires observing soil characteristics and applying fertilizers appropriate to its type (Chen, 2015). After extensive fertilization practice, ancient farmers gradually developed targeted fertilization methods to address the differences between zonal and non-zonal soils.

Manuring under the influence of zonal differences

Due to zonal factors such as climate and vegetation, there are distinct zonal differences in soil properties across China. In the Yuan Dynasty, Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) noted: “The land across the country is evenly divided between northern highlands and southern lowlands. North of the Yangtze and Huai Rivers, the elevated plains are suitable for millet and other dry crops. South of the Yangtze and Huai Rivers, the low and muddy lands are ideal for rice and glutinous crops. As one moves further north or south, the climate differences increase, affecting planting schedules. The east-west regions have more balanced climates, but still show variations between north and south” (Wang, 2009), reflecting the general understanding of the difference between the north and the south.

From the Bronze Age to the Han Dynasty, northern China served as the core area for population growth and agricultural development. To support the growing population, the farming system in northern China gradually shifted from the fallow system to continuous farming, with fertilization becoming a crucial factor for maintaining land productivity (Han, 2012). The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) and Qi Min Yao Shu (齐民要术) record that human and animal excrement, grass and wood ash, weeds, cultivated green manure, and manure from cow barns were key fertilizer sources used by northern farmers during this period (Table 2). Later, events such as the Disaster of Yongjia (永嘉之乱), the An Lushan Rebellion (安史之乱), and the Jingkang Incident (靖康之难) led to a large-scale migration of the northern population to the south, shifting the economic center of gravity southward (Han, 2012).

To support the large influx of people migrating south, producing sufficient food in the less agriculturally developed southern regions became a significant challenge. Building on northern fertilization practices, the ancestors gradually developed fertilizer sources with southern characteristics to enhance agricultural production in the south (Table 2). Taking advantage of the dense water network in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) records: “To make mud fertilizer, use boats and bamboo clamps to extract green mud from ditches or ports. Pour it onto the bank to solidify, cut it into blocks, and transport it to mix with manure for use in the fields” (Wang, 2009). The ancestors creatively utilized mud manure, and mixed it with other fertilizers, which can still be observed in rural areas of southern China today (Fig. 1). To adapt to the acidic soil in the southern region, the text also records: “When the water in paddy fields is cold, lime can be used as fertilizer to warm the soil and improve its quality” (Wang, 2009), indicating that lime neutralizes acidity in paddy soil. Similarly, Tian Gong Kai Wu (天工开物) records: “For cold and damp soil, dip seedling roots in bone ash or soak the seedlings in lime to prevent cold damage. However, this method is unsuitable for sunny and warm soil” (Song, 2021). For acidic soil fields with poor drainage and low temperatures in southern China, cremains are applied to supply phosphorus, and lime is used to neutralize soil acidity. Additionally, important innovations in fertilizer fermentation were made in the south, particularly in watery environments. In contrast to Qi Min Yao Shu (齐民要术), which mentions the cow barn as the accumulation site for manure (Jia, 2015), Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) and Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) refer to the manure house (Chen, 2015) or manure pit (Wang, 2009) as dedicated composting facilities. Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) records: “Southern farmers often build brick pits near their fields to ferment fertilizers thoroughly before use, resulting in highly fertile fields,” which highlights the specialization of composting in the south.

A Photo of mud manure collection in contemporary southern China. The photo was obtained from the Archives of Jingjiang City, Jiangsu Province, China (http://jjdag.jingjiang.gov.cn). B Tools for collecting river mud (Chen, 1958).

Manuring under the influence of non-zonal differences

Non-zonal factors such as soil parent material, topography, and groundwater level often result in a variety of soils with distinct properties within the same geographical area.

To adapt to varying soil properties, Zhou Li (周礼) recorded that agricultural officials understood the need for fertilization methods to align with the land’s characteristics. The specific practices are recorded as: “Different soils require specific animal manures: strong soil uses ox manure, red clay uses sheep manure, mound soil uses elk manure, marshy land uses deer manure, salty land uses raccoon manure, loose soil uses fox manure, clayey soil uses pig manure, compact soil uses bran manure, and light soil uses dog manure” (Zhou, 2014). In other words, specific types of animal manure are applied depending on soil properties. This illustrates the guiding principle of applying fertilizer according to soil characteristics.

Based on extensive planting experience, ancient farmers during the Tang and Song dynasties recognized significant variation in soil characteristics (Chen, 2015), leading to differences in soil fertility, and thus requiring distinct fertilization practices for different soils. According to Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书), “While black soil is fertile, excessive fertility can lead to lush crops with weak grains. Adding fresh soil balances this, making it appropriately loose. Barren, hard soil is poor, but with proper fertilization, crops thrive and yield solid grains. Success lies in managing the soil properly” (Chen, 2015). For fertile black soil, fresh, unfertilized soil is mixed in to avoid over fertility, which leads to dense stems but poor fruit yield. In contrast, for poor soil, additional manure should be applied.

The documents from the Ming and Qing Dynasties that reflect this thought are particularly abundant. The Book of Bao Di Quan Nong (宝坻劝农书) records: “Compact soil should be deeply plowed and covered with loose sand to loosen it. Loose soil benefits from being enriched with river mud. Cold soil can be treated by burning grass roots or applying lime to alleviate its coldness” (Wang, 2024). In other words, different fertilizers are selected for compact, loose, and cold soils. Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书) also notes: “Sheep manure is suitable for mulberry fields, while pig manure is ideal for rice paddies. Ash should not be used on loose soil as it depletes fertility, but it works well on fields to loosen the soil” (Wang, 2024), highlighting the importance of matching fertilizer to the soil characteristics of mulberry and paddy fields. Song Yingxing (宋应星) elaborated on the principle of fertilizing according to local conditions in Tian Gong Kai Wu (天工开物). Using rice planting as an example, he stated: “If the soil is dry and infertile, the rice ears will be sparse. For cold and damp soil, dip seedling roots in bone ash or soak the seedlings in lime to prevent cold damage. However, this method is unsuitable for sunny and warm soil. For hard and compact soil, it is better to plow and stack the soil in ridges, then burn the soil with firewood, but this is not suitable for clayey soil” (Song, 2021). Nong Zheng Quan Shu (农政全书) records: “For cotton fields, apply fertilizer before Qingming (清明), using manure, ash, bean cake, or fresh mud. The amount depends on the fertility of the field” (Xu, 1979). It emphasizes that fertilizer should not be applied indiscriminately; instead, different types should be used based on the field’s fertility. Wen Su Lu (问俗录), written during the Qing Dynasty, records: “In mountainous regions where the climate is cold and the soil is thin and poor, use burned cow bone ash mixed with plant ash and soil dust. Coat the seedling roots with this mixture before transplanting into the mud to ensure strong growth” (Chen, 1997). It records that farmers in Gu Tian used plant ash and cattle ashes to improve the cold and barren paddy fields. Yang Shen systematically summarized the method of fertilizing according to land in Zhi Ben Ti Gang (知本提纲): “Different soils require different fertilizers, just as diseases require specific treatments. For example: damp and cold land needs ash-based manure; yellow soil requires residue manure; sandy soil benefits from grass and mud manure; paddy fields work well with animal fur, horns, and bone manure; high, dry areas are best with pig manure. Salt-affected land should not be fertilized, as it causes white patches and prevents crop growth” (Wang, 1957). All these show that after long-term agricultural practice, ancient farmers deepened the understanding of fertilization according to the land, and knew how to improve the soil according to its characteristics.

Manuring adapting to the crops

Different crops have varying nutrient requirements, and the effectiveness of fertilizers varies accordingly. Consequently, fertilizer application must be tailored to the specific needs of each crop. This involves not only selecting the appropriate types of fertilizers for each crop but also adjusting fertilization techniques, including the quantity, timing, and method of application, based on the specific needs of the crop.

Application of different types of fertilizers based on crops

Extensive documentation exists on applying fertilizers tailored to the specific nutrient needs of various crops and varieties. For instance, in preparing rice seedling fields, Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) recommends fire ash, singed pig hair, and fermented coarse rice husks as the most suitable fertilizers (Chen, 2015). For wheat and vegetables, Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) identifies fire ash as the most suitable fertilizer (Wang, 2009). In fertilizing flowers, fruits, and vegetables, Zhong Yi Bi Yong (种艺必用) distinguishes specific fertilizers: jasmine and lilies require chicken manure, while grapes benefit from rice rinse water and black bean husks (Wu, 1963). Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书) records that sheep manure is suitable for mulberry fields, while pig ash is used on flower and grass fields to protect plants and loosen the soil (Wang, 2024). Bu Nong Shu (补农书) highlights the difference in fertilization between wheat and beans: “Beans require only ash, while wheat requires both ash and manure” (Wang, 2024). Yang Shen summarizes in Zhi Ben Ti Gang (知本提纲): “Different crops require specific fertilizers based on their characteristics. For example, rice fields benefit from bone, hoof, and fur fertilizers; wheat and millet require black bean manure and seedling manure; vegetables benefit from human manure and oil cakes” (Wang, 1957), illustrating how fertilizer suitability varies with different crops.

The records in Fu Jun Nong Chan Kao Lue (抚郡农产考略) further elaborate on fertilizers for different bean varieties. For instance, soybeans benefit from rice straw, thatch, ash, and manure, while black beans require only grass ash and soil manure, avoiding strong fertilizers (He, 1907). This demonstrates that even within the same crop category, such as beans, fertilizer requirements vary among different varieties.

Application of different fertilization techniques based on crops

Fertilization techniques involve key factors such as the amount of application, timing, and methods (Tan and Han, 2021). The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) outlines “zone planting” methods, which include specific fertilization techniques tailored to different crops. As shown in Table 3, mixing manure with soil is a general requirement for zone planting; however, fertilizer composition and quantities vary. For example, gourds require silkworm excrement, while taro requires moist soil. In terms of quantity, millet fields require one liter of manure per zone, while beans need one liter of manure per kan (坎). For melons, one mu (亩) requires 24 dan (石) of manure, while one mu of beans requires only 16 dan and 8 dou (斗), highlighting significant differences. Previous studies indicate that one mu of land is approximately 3840 zones, and about 1680 kan (Shi, 1956). According to the above records, one mu of millet requires 3840 liters of manure, while one mu of beans requires 1680 liters of fertilizer, indicating a significant difference between them. One mu of melons requires 24 dan of manure, whereas one mu of beans requires only 16 dan and 8 dou of manure, further demonstrating the differences. Fertilization timing also varies. Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) states: “In planting hemp, apply fertilizer once every ten days” and “For wheat cultivation, plow frequently and apply manure repeatedly” (Chen, 2015), indicating that the fertilization schedule for hemp differs from that of wheat.

Different rice varieties require distinct fertilization techniques, as detailed in Shen Shi’s Nong Shu (沈氏农书): “Early white rice is ideal but challenging to fertilize—too little and it grows poorly, too much and it harms the seedlings. Yellow rice, however, tolerates heavy fertilization and water” (Wang, 2024), highlighting the difference in fertilization needs between early white rice and yellow rice. The same book also discusses wheat: “Water wheat once in winter and again in spring; excessive fertilization leads to poor yields. Barley and millet, however, tolerate heavy fertilization, but the fertilizer should be concentrated in the latter half of their growth” (Wang, 2024). This demonstrates differences in the amount and timing of fertilization for various wheat varieties. Similarly, Qi Min Si Shu (齐民四术) of the Qing Dynasty states: “Barley is fertilized when it grows spikes; wheat is fertilized during root development” (Bao, 2001). This aligns with the previously mentioned principles, emphasizing the differences in fertilization timing for various crops.

Doing the farmers’ best

The San Cai theory emphasizes the harmonious unity of heaven, earth, and humanity, with the emphasis on humanity being a core element of the San Cai framework in ancient agricultural practices.

Zhou Li (周礼) records: “Agricultural officials must master the methods of improving the soil and choose crops based on the characteristics of the land” (Zhou, 2014). As early as the pre-Qin period, specialized officials were appointed to improve soil quality, particularly through fertilization. Lü Shi Chun Qiu (吕氏春秋) also states: “Farming is carried out by humans, nourished by the land, and sustained by the heavens” (Lü, 2011), placing humans at the center of agricultural production. This highlights the central role of human labor and asserts that “soil fertility can be enhanced through human effort,” reflecting the active human role in agricultural practices. However, historical records suggest that, until the Song Dynasty, human labor was often secondary to the principle of adhering to nature’s timing and properly utilizing the land, reflecting a more passive approach (Table 4).

By the Song Dynasty and beyond, rapid population growth and increased crop rotation made the challenge of maintaining and enhancing soil fertility unavoidable in agricultural production. To address this challenge, Chen Fu (陈旉) inherited and refined earlier soil theories, summarizing contemporary agricultural practices to propose the “Theory of Perpetual Soil Fertility (地力常新壮)” (Chen, 2015). This theory posits that through human fertilization efforts, soil fertility need not decline, but can instead remain consistently rich and productive. It refuted the widely held belief of the time that soil fertility inevitably declined with continuous farming. By emphasizing the active role of human labor in fertilization, this theory significantly advanced agricultural productivity and became a milestone in fertilization practices within the San Cai framework. This theory was further developed by later generations, as reflected in Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书): “If farmland is cultivated year after year, it will gradually become exhausted, its vitality will decline, and crops will fail to grow. Therefore, farmers must store decomposed manure to fertilize the soil, ensuring that its fertility remains strong and harvests do not diminish” (Wang, 2009). Subsequent agricultural texts also emphasize the importance of diligent fertilization and the experience of farmers (Table 4).

Of course, what is even more crucial is that humanity is both natural and social in nature (Zeng, 2001). In ancient Chinese society, the application of fertilizers was not merely an agricultural activity dependent on hard work and rich experience, but was also closely related to social factors of the time (Du, 2018). Therefore, under the San Cai framework, humanity includes not only physical labor (Fig. 2), but also the proactive adaptation to various social factors to achieve 人和, that is, fertilization carried out on the basis of harmony and unity between humans and society. Statistically, in the early 12th century, the population of Song Dynasty China surpassed the 100 million mark for the first time in history. By the 16th century, the population of the Ming Dynasty exceeded 200 million, and during the Qing Dynasty, it successively surpassed 300 and 400 million. This led to a significant decline in per capita arable land and exacerbated the man-land contradiction, especially in the southern regions (Du, 2018). In this context, various aspects of economic policy, land systems, tenant relations, and taxation systems changed. For instance, the popularity of monetary land rents and the prevalence of the perpetual lease system were significant. While these factors did not directly affect the fertilization process itself, they objectively increased the initiative of farmers in acquiring and investing in fertilizers, thereby promoting the advancement of the ancient Chinese fertilization system (Du, 2018). These developments clearly reflect the increasing importance of human involvement in the fertilization system and demonstrate the further deepening of the San Cai philosophy.

This illustration depicts diligent farmers carrying buckets filled with manure water on their shoulders to the fields, using a manure scoop to apply the fertilizer (Jiao, 2013).

Discussion and conclusions

This study examines ancient Chinese agricultural practices, with particular focus on fertilization practices centered around the San Cai theory. It reveals how ancient Chinese agricultural practices were shaped by both natural and human factors. The comprehensive analysis of fertilization practices from the perspective of the San Cai theory shows that although ancient people may not have had a systematic and mature understanding of plant physiology, they developed sustainable fertilization methods through experiential observation and practical knowledge. The long history of fertilization practices under the guidance of the San Cai philosophy fully reflects the ancestors’ experiential understanding of seasonal timing, soil, nutrient recycling from waste, and crops, as well as their proactive adaptation to and transformation of the environment. From a modern perspective, ancient fertilization still contains many reasonable elements.

Central to Chinese agricultural philosophy, the San Cai theory emphasizes the interrelationship between heaven, earth, and humanity. This concept profoundly influenced ancient manuring practices. As noted in classical texts, fertilization practices were adapted to time changes, soil conditions, and the specific needs of crops. Ancient Chinese agricultural texts, such as The Book of Fan Shengzhi (氾胜之书) and Qi Min Yao Shu (齐民要术), demonstrate a well-developed understanding of the necessity to adjust fertilizer types and quantities according to crop development and seasonal conditions. This approach mirrors contemporary precision agriculture principles, where inputs are tailored to specific conditions to optimize efficiency and sustainability.

From a global agricultural perspective, ancient European regions also recognized the role of fertilizers in soil improvement early on. Around the 4th century BC, in Greek agriculture, Xenophon suggested understanding which crops were suitable for planting in specific soils and recommended using ash from burned crop residues and livestock manure for fertilization (David, 2024). The Roman scholar Cassius considered bird manure, particularly pigeon manure, the best fertilizer for grain crops, while horse manure was regarded as the worst (Varro, 1997). Similar to the theory of “perpetual soil fertility” proposed in Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) during the Song Dynasty, around 60 AD, the Roman scholar Columella believed that by properly caring for the soil and regularly applying fertilizer, the soil would remain fertile and not become exhausted (David, 2024). However, according to existing records and studies, these ancient civilizations, including the Maya civilization of ancient America, ultimately faced the crisis of soil erosion and degradation. Some scholars even argue that soil problems were the “graveyard” of “Old World” empires (David, 2024). Although ancient China might have faced similar problems as well, its society continued to develop and it became the only ancient civilization in the world that was not interrupted, indicating that ancient fertilization practices in Europe and America were different from the more refined and systematic fertilization system in ancient China. Although ancient Chinese farmers were also aware that soil degradation could occur, they were more cautious with manure, with sayings like 惜粪如惜金 (manure is as precious as gold). In addition to manure, they made great efforts to collect and develop various types of fertilizers. According to statistics, during the Song and Yuan dynasties, over sixty types of fertilizers were used, and by the Ming Dynasty, Xu Guangqi (徐光启) recorded around 10 categories and approximately 120 types of fertilizers. By the Qing Dynasty, the number of types had reached 125 (Du, 2018). Specifically, besides manure, wood ash, and green manure common to both China and the West, Chinese fertilizers also included bone ash, cake fertilizers, mud fertilizers, etc. Fertilizer collection permeated all aspects of human life. Notably, human excrement was used, referred to as 金汁 (golden liquid) in China, and during the Ming and Qing dynasties, human excrement became an important commodity. The trade of human manure led to the establishment of a specialized “golden liquid industry,” which was rarely seen in Western agriculture (Du, 2018). More importantly, ancient Chinese farmers invested more energy in practicing and experimenting with fertilization, gaining more experience in the details of fertilization. This contributed to the continued intensification of Chinese fertilization, which was distinctly different from the leisure-based agricultural systems of “two-field” or “three-field” rotation in medieval Western Europe (Cao, 1984). It can be said that it was the principles of ancient Chinese fertilization distilled from the San Cai perspective that guided Chinese agriculture on a different developmental path from the West. The careful use of organic fertilizers not only nourished the soil but also maintained its long-term health, reflecting the ancient Chinese ancestors’ exceptional skills in soil fertility management and their early understanding of sustainable agriculture.

The study further emphasizes the importance of adapting fertilization practices to specific soil conditions, as exemplified in the differentiated fertilization strategies for northern and southern soils in ancient China. Environmental factors, such as soil type, moisture levels, and climatic conditions, played a pivotal role in determining the types and quantities of fertilizers applied. For example, in areas with heavy clay soils, fertilizers such as pig manure were used to improve soil structure, while lighter soils were enriched with materials like ash or lime. This nuanced approach to fertilization, tailored to the specific characteristics of the land, reflects a profound ecological understanding and aligns with sustainable land management principles observed in contemporary agricultural practices.

Since the economic center of China gradually shifted from the north to the southern areas during the Tang and Song dynasties, the fertilization knowledge accumulated in the past, which focused on northern dryland farming, faced a crisis. The increasingly strained man-land relationship created a more urgent demand for efficient agricultural practices. Although the southern and northern regions of China faced different environmental and cultural factors, and the southern regions lagged behind the north in terms of agricultural development, the basic principle of adapting fertilization to time, soil and crops helped the ancestors innovate. They not only developed new fertilization methods to suit the local environment, such as mixing mud with other fertilizers and using lime to neutralize acidic soils, but also, from a technological history perspective, they developed distinctive practices in areas such as fertilizer collection, storage, tools for fertilization, and fertilization theory. For example, when making forks to collect manure, northern regions commonly used willow twigs, while southern regions preferred bamboo. For manure transportation, short distances were carried by humans, while longer distances saw the use of carts and horses in the north with dry manure, while the south predominantly used boats to transport manure (Du, 2018), often in the form of manure water, applying it with manure scoops (Fig. 2). Overall, these practices indicate that fertilization technology in the southern regions developed its own system, even surpassing the northern regions. This reflects the resilience of ancient people in adapting to various environmental conditions for fertilization, guided by the fundamental idea of the harmonious unity between heaven, earth, and humanity, shaped by long-term practical experience.

An important insight from this study is that ancient Chinese fertilization techniques developed based on the diligence and rich experience of farmers, as well as the harmonious unity between humanity and society. People increasingly recognized the significant role that humans play in enhancing soil fertility. Texts such as Chen Fu’s Nong Shu (陈旉农书) and Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu (王祯农书) emphasize the importance of applying fertilizers at the right time and in the proper amount, while also highlighting the core role of humans in this process. This emphasis is not only reflected in the labor aspect, marking an important shift from the early passive adherence to the natural rhythms of the land to active intervention, but also in the fertilization practices that adapt proactively to various social factors, achieving “harmony between humanity”.

The archaeological significance of this study is considerable. By examining ancient fertilization techniques and their integration into crop cultivation, the research provides valuable insights into the daily practices and agricultural philosophies of ancient Chinese societies. This contributes to a broader understanding of prehistoric land management and farming systems, particularly in regions where written records are scarce.

The contemporary relevance of these ancient practices is also immense. As modern agriculture confronts challenges such as soil degradation, nutrient imbalances, and the overuse of chemical fertilizers, ancient fertilization techniques offer invaluable lessons. The emphasis on organic fertilizers, nutrient cycling, and soil conservation in ancient China presents a sustainable model for contemporary agricultural practices. By revisiting these practices and integrating them into modern farming systems, more environmentally friendly and efficient fertilization methods can be developed to mitigate the negative impacts of chemical fertilizers. From an environmental and sanitation perspective, ancient China made full use of manure, waste, and other by-products. In contrast to 19th-century London, which spent millions of pounds annually to manage sewage pollution in the Thames River, ancient China’s approach was fully endorsed by Karl Marx (Du, 2018). This method of waste management still holds reference value today, particularly in reducing environmental pollution and saving on the financial costs of waste treatment.

In conclusion, this study not only illuminates the depth of ancient Chinese agricultural practices but also underscores the importance of integrating philosophical concepts, such as the San Cai theory, with practical farming techniques. The sustainable practices developed by ancient farmers—particularly their use of organic fertilizers and emphasis on soil health—offer valuable insights for modern agricultural system. This study underscores the importance of understanding historical agricultural wisdom as a means of addressing current environmental challenges. By integrating traditional knowledge with modern innovations, a more sustainable and resilient agricultural future can be cultivated, promoting harmony between humans and the environment.

Future research could focus on how specific ancient fertilization techniques, such as those used in rice and wheat cultivation, can be adapted to modern agricultural systems. Additionally, examining the role of crop-specific fertilizers within the context of modern organic farming could provide further insights into the benefits of integrating ancient practices with contemporary ecological farming techniques.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

An C-B, Dong W, Chen Y et al. (2015) Stable isotopic investigations of modern and charred foxtail millet and the implications for environmental archaeological reconstruction in the western Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Res. 84(1):144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2015.04.001

Anonymous (2015) Shi Jing. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Bao SC (2001) Qi Min Si Shu. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Bogaard A (2004) Neolithic farming in central Europe: An archaeobotanical study of crop husbandry practices. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203358009

Bogaard A, Fraser R, Heaton TH et al. (2013) Crop manuring and intensive land management by Europe’s first farmers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110(31):12589–12594. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1305913110

Canti M (1997) An investigation of microscopic calcareous spherulites from herbivore dungs. J. Archaeol. Sci. 24(3):219–231. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1996.0119

Cao LG(1984) A History of Fertilizers. China Agriculture Press, Beijing

Chen F (2015) Chen Fu’s Nong Shu. China Agricultural Press, Beijing

Chen HL (1958) Research of Bu Nong Shu. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Chen SS (1997) Wen Su Lu. Taiwan Province Historical Document Series, Taiwan Province Documentation Committee. (in Chinese)

Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanjing Agricultural University, the Chinese Agricultural Genetics Research Institute (1985) A Concise History of Ancient Chinese Agricultural Science and Technology. Jiangsu Science and Technology Press, Jiangsu

Dai S (2017) Li Ji. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

David R (2024) Dirt: The erosion of civilizations. Yilin Press, Jiangsu

Du XH (2018) Research on Traditional Fertilizer Knowledge and Technical Practice in China: 10th - 19th Century. China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, Beijing

Feng RB (1985) You Shan Za Shuo. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Guo WT (1992) A discussion on traditional agronomy during the Qianlong period. Agric Archaeol. 3:126–133

Guo ZT, Ren XB, Lü HY et al. (2016) Impacts of climate change and human adaptation over the past 20,000 years: Research progress of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Strategic Priority Program ‘Carbon Budget Certification and Related Issues for Coping with Climate Change’. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 31(1):142–151+53

Han FZ (2010) Han Fei Zi. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Han JY (2015) On the origin, formation, and development of ‘Early China’ in cultural terms. Jianghan Archaeology 67–74

Han ML (2012) The Historical Agricultural Geography of China: Volume 1. Peking University Press, Beijing

He GD (1907) Fu Jun Nong Chan Kao Lue. Soochow Printing Bureau

He HR, Zhang LX, Li Q (2006) Study on farmers’ fertilization behavior and agricultural non-point source pollution. Agric Technol. Econ. 6:2–10

Hu HX (1981) Further discussion on the fertilization practices of the Yin Dynasty. Soc. Sci. Front 1:102–109

Jia SX (2015) Qi Min Yao Shu. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Jiang G (2002) Pu Mao Nong Zi. Shanghai Classics Publishing House, Shanghai

Jiao BZ (2013) The Picture of Farming and Weaving during the Reign of Emperor Kangxi. Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, Zhejiang

Jin D, Shang X, Jiang H et al. (2024) Agricultural practices during the middle and late Yangshao periods (6000–4500 BP) in the Guanzhong Basin. North China J. Archaeol. Sci: Rep. 53:104345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.104345

Jin JF, Lü SG (2016) Complete Explanation of Zhouyi. Shanghai Classics Publishing House, Shanghai

Lao Z (2014) Lao Zi. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Li GP (1997) Agricultural practices and the formation of the Sai Cai theory. Agric Archaeol. 1:104–107+18

Li XQ (2022) The origin, spread, and impact of agriculture. Acta Anthropol Sinica 1097–1108. 10.16359 (in Chinese)

Lin PT (1993) Discussion on the application of plant ash. Agric Archaeol. 1:78–80+86

Liu B, Guo C, Xu J et al. (2024) Co-benefits for net carbon emissions and rice yields through improved management of organic nitrogen and water. Nat. Food 5(3):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00739-6

Lu MS (1985) Nong Sang Yi Shi Cuo Yao. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Lü BW (2011) Lü Shi Chun Qiu. Translated and annotated by Lu Jiu. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Min ZD (1992) A Brief History of Ancient Chinese Farming. Hebei Science and Technology Press, Hebei

Ouyang H, Shang X, Hu Y et al. (2024) Experimental archaeological study in China: Implications for reconstruction of past manuring and dietary practices indicated by δ15N values of Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum. Herit. Sci. 12(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-00834-y

Qian H, Zhu X, Huang S et al. (2023) Greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation in rice agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4(10):716–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00385-7

Shi SH (1956) Interpretation of the Book of Fan Shengzhi. Science Press, Beijing

Shi TS, Collins SL, Yu K et al. (2024) A global meta-analysis on the effects of organic and inorganic fertilization on grasslands and croplands. Nat. Commun. 15(1):3411. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-13419-y

Sims J, Goggin N, McDermott J (1999) Nutrient management for water quality protection: Integrating research into environmental policy. Water Sci. Technol. 39(12):291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00331-1

Soil Survey Office of Shaanxi Province (1992) Shaanxi Soils. Science Press, Beijing

Song YX (2021) Tian Gong Kai Wu. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Styring AK, Ater M, Hmimsa Y et al. (2016) Disentangling the effect of farming practice from aridity on crop stable isotope values: A present-day model from Morocco and its application to early farming sites in the eastern Mediterranean. Anthropocene Rev. 3(1):2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019616630765

Styring AK, Charles M, Fantone F et al. (2017) Isotope evidence for agricultural extensification reveals how the world’s first cities were fed. Nat. Plants 3(6):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.76

Styring AK, Diop AM, Bogaard A et al. (2019) Nitrogen isotope values of Pennisetum glaucum (pearl millet) grains: Towards a reconstruction of past cultivation conditions in the Sahel. West Afr. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot 28:663–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-019-00739-8

Tan JF, Han YL (2021) Principles and Techniques of Crop Fertilization. China Agricultural University Press, Beijing

The Scientific Investigation Team of the Loess Plateau, Chinese Academy of Sciences (1992) Dataset of Resources, Environment, Society, and Economy in the Loess Plateau Region. China Economic Press, Beijing

Tian S, Zhu B, Yin R et al. (2022) Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation. Soil Biol. Biochem 165:108533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108533

Varro M (1997) On agriculture. The Commercial Press, Beijing

Wang SM (2024) A Collection of Chinese Ancient Agricultural Books. Phoenix Publishing House, Jiangsu

Wang X, Fuller BT, Zhang PC et al. (2018) Millet manuring as a driving force for the Late Neolithic agricultural expansion of north China. Sci. Rep. 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30889-5

Wang YH (1957) Qin Jin Nong Yan. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Wang Z (2009) Wang Zhen’s Nong Shu. Qi Lu Poetry Press, Shandong

Wu Y (1963) Zhong Yi Bi Yong. Agricultural Press, Beijing

Xia ZK, Zhang JN (2019) The rise, development, and prospects of environmental archaeology in China. J. Palaeogeogr. 21(1):175–188

Xu GQ (1979) Nong Zheng Quan Shu. Shanghai Classics Publishing House, Shanghai

Xu XZ (1560, 39th Year of the Jiajing Era) Wu Xing Zhang Gu Ji, 60

Xun Z (2015) Xun Zi. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Yang J, Zhang D, Yang X et al. (2022) Sustainable intensification of millet–pig agriculture in Neolithic North China. Nat. Sustain 5(9):780–786. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00935-8

Yang YC (1957) Nong Yan Zhu Shi. Shaanxi People’s Press, Shaanxi

Zeng XS (2001) A Primary Probe into the Problems about Human Elements in Traditional Chinese Agricultural Theory. Studies in the History of Natural Sciences (01):1-20

Zhang BY, Chen TL, Wang B (2010) The effect of long-term chemical fertilizer application on soil quality. China Agric Bull. 26(11):182–187

Zhang K (1989) Miscellaneous discussion on fertilization in ancient and modern China. Anc. Mod. Agric 2:24–31

Zhao ZJ (2019) An overview of the origins of Chinese agriculture. Heritage Conserv Res 1–7. https://doi.org/10.19490/j.cnki.issn2096-0913.2019.01.001

Zhou GD (2014) Zhou Li. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Zhou GX (2006) Research on techniques for traditional chinese manure, in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Nanjing Agricultural University

Zhu PR (1983) The emergence and development of coated seeds in China. Chin. Agric Hist. 1:17–21

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Projects of the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant number 21BKG040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OYHY and SX had the idea for the article; OYHY performed the literature search and analysis, and drafted the work. SX critically revised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article draws upon existing literature and secondary sources of information and as per institutional guidelines, ethical approval was not necessary for this study.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouyang, H., Shang, X. The manuring principles in ancient China from the perspective of the San Cai theory. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1457 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05815-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05815-7