Abstract

University science parks are an important arena and driver for science and technology innovation and development. In this study, we developed the theoretical framework for evolutionary economic geography, which considers the agglomeration effect, path dependence, spin-off process, and local institutions. Next, we investigated the development model and driving mechanism of university science parks using China as a typical case study. We identified three types of development models—university-driven, university–government cooperation, and local dependence—for China’s university science parks. The theoretical contributions of this study lie in constructing an analytical framework for university science parks from the perspective of evolutionary economic geography, thereby expanding the global knowledge system of science and technology park development. In addition, this study supports the development and decision-making surrounding university science parks in China and other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of increasingly global innovation competition, university science parks—serving as core policy instruments for governments to foster business-cluster development—have emerged as critical hubs, bridging academia, industry, and policy-making (Hamon et al. 2024). These nonspontaneous, policy-driven clusters are essentially artifacts of political decision-making: through specialized management teams, they systematically cultivate knowledge and technology-intensive enterprises, with the explicit goal of driving high-value-added transformation in regional economies (Poonjan et al. 2022; Unlu et al. 2023). Whether developed countries leverage institutional strengths to construct innovation ecosystems or developing nations accelerate technological catch-up through policy transplantation, the worldwide proliferation of science parks has profoundly reshaped the geography of innovation. Substantial public investment in establishing and promoting these parks reflects nations’ strategic expectations for their role in advancing high-technology innovation and entrepreneurship (Anton-Tejon et al. 2024). However, the academic community has long fixated on successful paradigms in specific regions, overlooking the institutional dynamics underpinning divergent practices in emerging economies.

University science parks originated with the Stanford Research Park, established by Stanford University in the United States. The definition of university science parks can be summarized in three ways: concentration of high-technology industries and professional services, technical support provided by at least one university or technical college, and the inclusion of research and development in business activities (Guadix et al. 2016). Various countries consistently use university resources to cultivate, practice, and develop enterprises (Soetanto and Jack, 2016). The initial provision of offices and shared facilities gradually evolved into technology transfer, business mentoring, and capital support for emerging enterprises.

Based on different factor resources and external support, countries have formed development paths with unique characteristics in the development of university science parks. For example, in Spain, initial science parks did not link to universities and were established with the sole objective of attracting large science and technology firms; it was only with a deeper understanding of the key role of universities in technology transfer that the model of establishing science parks in universities became a major initiative to support research and development (R&D) and innovation (Rocio Vasquez-Urriago et al. 2016). Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry provides subsidies to university science parks to support technology commercialization by enterprises (Lynn and Kishida, 2004). Sweden established intellectual property commercialization mechanisms to support the commercialization of university research (Goldfarb and Henrekson, 2003). The development of university science parks in China has gone through early stages of cooperation between universities and enterprises in the form of technical support for enterprises and their commercial activities, working toward the expansion of tripartite cooperation between universities, enterprises, and governments in the form of local government planning, site selection, and collaboration with scientific research institutions.

University science parks can promote the commercialization and industrialization of scientific and technological achievements through the advantages of effective integration of knowledge, talents, and an innovation environment, with universities, capital, management, and demands of the market, driving regional economic development (Bruneel et al. 2012). University science parks are gradually becoming an important arena for talent cultivation, industrial agglomeration, enterprise incubation, knowledge spillover, and independent innovation.

However, existing studies have focused on the homogenization of university science parks, the impact of capital investment, management style, and policy on university science parks. Extant studies also described the impact of university science parks on innovation performance (Bathelt et al. 2010; Diez-Vial and Montoro-Sanchez, 2016; Gilsing et al. 2010; Siegel et al. 2002). Researchers have paid less attention to how place-specific models have been formed in the process of university science park development.

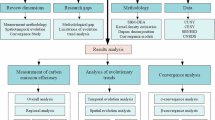

Taking China as a typical case, this study explored the diversified and localized development models and dynamics of university science parks from the perspective of evolutionary economic geography. Specifically, in this study, we explored the spatial behaviors of China’s university science parks in location choice from the micro- (incubatees), meso- (science and technology parks and industries), and macro- (regional) levels, based on the theoretical framework of evolutionary economic geography. We also sought to examine the dynamic mechanism of university science parks from the perspectives of economic, institutional, and geographic differences.

The contribution of this study is multifold. First, this study extends the global body of knowledge on science-park development from the perspective of evolutionary economic geography. By integrating core mechanisms of evolutionary economic geography—including firm spin-off processes, path dependence, agglomeration effects, and local institutions—with production factors such as regional economic disparities under the factor-endowment hypothesis and financing environments, this study constructs a unified analytical framework. We use this framework to elucidate how university science parks develop distinct models in specific contextual settings, thereby addressing a critical gap in existing theories that have struggled to explain the nonlinear developmental trajectories of science parks. Second, this study has practical applications for the development of university science parks in China and other emerging markets. Existing research on science parks is predominantly situated in the contextual frameworks of developed countries. In contrast, in this study, we systematically articulate the unique regional innovation ecosystems that have emerged under China’s institutional environment, unraveling the spatial logic through which emerging economies achieve technological catch-up through institutional embeddedness. Finally, study findings will be of value to the Chinese government’s policy optimization on university science park development. Local governments can replicate and promote region-specific development models informed by the resource endowments of different regions and science parks, while fostering the targeted development of context-specific dynamic mechanisms.

Literature review

University Science Park

The early development of university science parks primarily focused on supporting enterprises and their commercial activities through technical means (Patton and Marlow, 2011), with startups accessing technology transfer through university laboratories acting as “technical intermediaries.” Universities play a critical role in generating and facilitating knowledge dissemination that underpins industrial innovation (Barbera and Fassero, 2013). As these parks evolved, governments increasingly recognized their strategic value in incubating new enterprises through resource integration, providing additional support through funding, tax incentives, and other mechanisms (Henriques et al. 2018). Governments also became pivotal in addressing market failures in innovation during the incubation process, thereby gradually becoming key stakeholders in university science parks (Tang et al. 2014). Planners and policymakers in regions such as Singapore, China, and Malaysia have employed science and technology parks as essential policy tools for high-technology development (Hamon et al. 2024). This university–industry–government collaborative model has spawned diverse management mechanisms: in mature innovation ecosystems, market-driven autonomous models emphasize spontaneous collaboration between universities and enterprises, leveraging institutional advantages to create virtuous cycles of knowledge spillover; in emerging economies, policy-driven top-down designs accelerate technological catch-up through centralized resource allocation, demonstrating the efficient agglomeration of innovative factors under government leadership (Hamon et al. 2024).

The diversification of resource inputs represents another critical feature of university science park development (Lopes et al. 2025). The early single-source investment model, dominated by government funding and university-endowed resources, has evolved into a composite ecosystem encompassing capital, talent, technology, and spatial infrastructure. As core knowledge generators, universities provide not only technical support through laboratory access and the presence of research teams, but also intellectual resources through entrepreneur mentor networks and student innovation teams, forming a direct conduit to transform academic talent into entrepreneurial talent (Lew et al. 2018; Lofsten and Klofsten, 2024). Beyond financial support, governments reduce operational costs for enterprises through land allocation and shared laboratory infrastructure (Takeda et al. 2008); industry and civil-society entities enrich resource supply by establishing joint R&D centers, defining targeted technical demands, and building resource-matching platforms to shorten technology commercialization cycles (Durao et al. 2005). Consequently, the Triple Helix paradigm—centered on industry, university, and government collaboration—has gained wide acceptance in research on university science parks (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 1997).

In innovation performance, companies with formal cooperation agreements with universities and research institutions derive the greatest benefits from park membership, as they can more easily integrate existing knowledge into their operations to enhance product innovation (Zhang et al. 2024). Researchers have shown a positive correlation between universities’ active engagement in science park management (e.g., direct administrative control versus no formal ties) and the number of patent applications filed by parks (Albahari et al. 2017). Companies collaborating with research entities through such agreements can share internal R&D resources to facilitate product innovation more effectively (Diez-Vial and Fernandez-Olmos, 2015). For example, based on Spain’s annual technological innovation surveys, Vásquez-Urriago found that science parks strongly and positively influence the likelihood and the quantity of product innovation among tenant firms (Rocio Vasquez-Urriago et al. 2016). Yang et al. (2009) also highlighted that new technology-based firms in science parks exhibit higher investment efficiency, attributed to their marginal R&D advantages, cluster effects, and institutional linkages between enterprises and research organizations.

Methodologically, extant literature is dominated by quantitative approaches, using panel-data regression, spatial econometric models, and other techniques to analyze explicit indicators like patent counts and GDP contributions in evaluating policy impacts and innovation outputs; in contrast, social-network analysis reveals knowledge flows among innovation actors (Anton-Tejon et al. 2024; Liberati et al. 2016; Schiavone et al. 2014; Squicciarini, 2008). Although these methods effectively capture statistical relationships between variables, they struggle to explain the tacit mechanisms in innovation processes or dynamic institutional changes (Mohammadi et al. 2024). This struggle constitutes a key rationale for our adoption of qualitative methods: through multiple-case comparisons and process tracing, we were able to deeply decode the formation logic of diverse development models and the adaptive strategies emerging from resource games among stakeholders.

Evolutionary economic geography

Since its emergence in the late 20th century, evolutionary economic geography (EEG) has established itself as a pivotal theoretical paradigm to explicate the spatial evolution of regional economies. Amid the complex challenges of the knowledge economy’s ascendancy, accelerated technological disruptions, and escalating global developmental uncertainties, this discipline has catalyzed a “multidimensional turn” in economic geography through its synthesis with evolutionary economics (R.A. Boschma and Frenken, 2006). This intellectual shift transcends the static equilibrium frameworks of traditional location theory, redefining the microfoundations of spatial-evolution research by emphasizing dynamic, process-based analyses (R. Boschma and Frenken, 2011).

EEG’s theoretical edifice is anchored in three foundational pillars of evolutionary economics: generalized Darwinism, path-dependence theory, and complexity science. Generalized Darwinism introduces mechanisms of diversity, variation, selection, and retention into economic systems, conceptualizing corporate routines as inheritable organizational “genes” that shape firms’ spatial behaviors (Martin and Sunley, 2015). These routines—forged through historical learning, organizational adaptation, and institutional interaction—govern firm structure, decision-making, and innovation trajectories, propagating through processes of firm spawning and interfirm knowledge transfer (Coe, 2011). Path-dependence theory underscores the localized embeddedness of technological, institutional, and economic configurations whereby historical choices lock regions into specific developmental pathways, imposing enduring constraints on contemporary economic opportunities (R. Boschma et al. 2017). Complexity science, in contrast, illuminates multiscalar interactions in and across economic systems, recognizing that regional economies are nested in hierarchical networks of global, national, and local forces (Martin and Sunley, 2007). This systemic perspective enables EEG to model the intricate interplay of factors—from microlevel firm dynamics to macrolevel institutional landscapes—thereby enriching its capacity to explain spatial outcomes as emergent properties of adaptive systems. By integrating these pillars, EEG offers a holistic framework to analyze firm-location choices, technology-diffusion patterns, and the influences of localized knowledge ecosystems, organizational practices, and policy regimes (Essletzbichler, 2012). This approach not only deciphers the formation of enterprise clusters but also raises alerts to risks of innovation stagnation arising from rigid path dependence, providing a dynamic lens for understanding the variegated trajectories of regional development (Hassink et al. 2014).

In empirical applications, EEG demonstrates exceptional explanatory versatility. The concept of “related variety,” for instance, elucidates the coevolutionary dynamics between emerging and incumbent industries, offering insights into how postindustrial regions leverage technological adjacencies to facilitate green industrial transformations (Jakobsen et al. 2022). Through the lens of “firm heterogeneity,” researchers tracked the spatial restructuring of industrial clusters, revealing how technological spillovers from lead firms reorganize regional divisions of labor, fostering specialized innovation ecosystems (Cainelli and Iacobucci, 2016). In policy arenas, EEG challenges universal institutional transplantation, advocating instead for context-sensitive policy designs that align with regional technological endowments and institutional thickness (Benner, 2022). This stance informs the formulation of development strategies that balance global integration with local specificity (Yeung, 2021; Zhu and He, 2022).

As highlighted earlier, traditional quantitative approaches to innovation metrics suffer from “variable segmentation,” reducing complex interactions—such as technology investment, firm spawning, and policy interventions—to isolated variables in linear models. These methods falter in unpacking the “black box” of implicit mechanisms underpinning innovation, such as knowledge tacitly exchanged in localized networks or institutional routines shaping firm behavior. EEG addresses this gap by prioritizing historical contingency and spatial embeddedness, casting university science parks as “innovation nodes” within evolving regional ecosystems. EEG’s core proposition posits that regional innovation systems evolve not as linear, additive processes but as outcomes of coevolving technological legacies, institutional architectures, firm networks, and geographical contexts (Ter Wal and Boschma, 2011). Temporally, these contexts manifest as a dialectic between path dependence—wherein past successes reinforce specific trajectories—and path creation—wherein disruptions (e.g., policy shocks and radical innovations) enable new developmental paths (Hassink et al. 2019). Spatially, these contexts materialize in the interplay between agglomeration economies—driving knowledge spillovers and productivity gains—and institutional designs—shaping spatial distributions of resources and regulatory frameworks (Harris, 2021). By integrating these temporal–spatial dynamics, EEG not only rectifies the neglect of process and context in traditional research, but also uncovers the structural determinants of divergent innovation performance among science parks, thereby advancing theoretical rigor and policy relevance in an era of global economic reconfiguration.

Theoretical background and analytical framework

Firm innovation comes from the degree of access to external knowledge and the ability to exchange and combine this knowledge with the traditional role of the university as a knowledge producer; firm innovation has geographically bridged the distance of knowledge exchange between firms and institutes through the development of science parks (Kogut and Zander, 2003). Because the first university science park was established in Stanford in 1951, the role of science parks in facilitating firm innovation has been widely recognised. Although Phelps et al. viewed firms as different nodes in a knowledge network (Phelps et al. 2012), university science parks play the role of knowledge repositories, connecting industries, universities, intermediaries, researchers, and firms, providing internodal access, transfer, and creation of knowledge channels (Soetanto and Jack, 2016); the position of firms in the network structure determines the ability to absorb knowledge (Diez-Vial and Montoro-Sanchez, 2016; Patton, 2014; Soetanto and van Geenhuizen, 2015).

Etzkowitz and Leydsdorff (1997) introduced the role of government involvement in university–firm interactions based on the triple helix model, arguing that the government moderates the way universities and firms collaborate through financial and fiscal instruments (Albahari et al. 2017; Cooke and Leydesdorff, 2006). From an entrepreneurial perspective, research in science parks, in contrast, has focused on the impact of incubation support and innovation on entrepreneurial performance (Aernoudt, 2004). Universities conduct scientific research and research spin-offs, supporting business innovation through innovative products or services. However, many barriers accrue to this innovation support due to limitations in the market and in the operational skills of firms (Gredel et al. 2012; van Geenhuizen and Soetanto, 2009). Therefore, a spatial carrier of business environments to support entrepreneurship has been constructed by university incubators such that universities, companies, and facilities concentrate in a single location (Bergek and Norrman, 2008; Nosella and Grimaldi, 2009).

Existing research explains university science parks as a relationship established between universities, firms, and the government, and how this relationship facilitates technological innovation in the field. However, most researchers defaulted to the homogeneity of university science parks and ignored the impact of exogenous factors. Do all science parks benefit from the same development model? Do they have the same impact on all enterprises entering the park? Considering these issues, some scholars have questioned the above assumptions (Diez-Vial and Fernandez-Olmos, 2015; Huang et al. 2012; Liberati et al. 2016).

EEG has gradually emerged in recent years with a theoretical basis derived from the modern biological evolutionary theory of generalised Darwinism, which considers regional economic landscapes to be the product of historical activity. Starting from the coevolution law of enterprises, industries, networks, cities, and regions, we not only considered the impact of university science parks on the regional economy, but also deliberated on the impact of the heterogeneity of location conditions in different regions on the development path of university science parks. We established the spatial-network relationship of university science parks from a dynamic perspective. The theory of EEG takes the spin-off process as an important mechanism in the diffusion of knowledge and practices and avers that the parent enterprise replicates knowledge and successful practices to subsidiary enterprises (Buenstorf and Klepper, 2009). The formation path of university science parks relies on the practices and knowledge base of its “parent” higher education institutions. EEG considers path dependence, as a basic feature of local economic structure, as the trajectory of past paths on which the system relies in its development (Martin and Sunley, 2006), emphasising the cognitive proximity of the park’s development direction to the local industrial structure and the comparative advantage generated by new technologies and products through technological linkages (R. Boschma et al. 2012). In contrast, science parks, as spatial agglomerations of firms, benefit from agglomeration effects for labour, knowledge spillovers, and cost reductions (McCann and Folta, 2008; Oerlemans and Meeus, 2005). In addition, quantitative studies of EEG have gradually noticed regional institutions (Wenting and Frenken, 2011), often manifesting as important conditions for the development of new industries and breakthroughs of mature industries (Maskell and Malmberg, 2007).

Based on EEG, for this study, we constructed a theoretical-analysis framework for university science parks through four interplaying driving forces: a spin-off process, path dependence, an agglomeration effect, and local institutions.

Spin-off process

EEG suggests that, in the spin-off process, derivatives tend to inherit the successful practices of the parent and have a higher probability of developing a new industry to gain a comparative advantage compared to competitors (Klepper, 2007). In the spin-off model constructed by Arthur (1994), existing firms spin off new firms, and the probability of new firms being created depends on the number of local parent firms; also, spin-off firms have a competitive advantage over other firms in the industry. However, in this model, subfirms are considered to be homogeneous and stationary; therefore, in an evolutionary framework, Klepper (2010) proposed that higher-performing new firms do not originate from the number of local firms; rather, they rely on parent-firm practices that the new firm inherits at entry. In empirical studies, the automotive industry in the UK, the tire industry in Ohio, and the motorbike industry in Italy have confirmed the important role of spin-off processes in industry formation (Ron A. Boschma and Wenting, 2007; Buenstorf and Klepper, 2009; Morrison and Boschma, 2019). Based on the evolutionary perspective of university science parks, the entrepreneurial foundation of the university is as a “parent enterprise,” whose technology, competence, and resources are transformed into the development path of new enterprises (Asheim et al. 2011; Frenken et al. 2007). In empirical studies of university participation in science parks, knowledge spillovers from university research are usually geographically localised (Fischer and Varga, 2003; Sonn and Storper, 2008) and the spin-off process establishes a link between the university and the firm to transfer knowledge and practices to the incubatees to ensure they have a comparative advantage in industrial competition (Perkmann et al. 2013).

Path dependence

Path dependence emphasises “non-transitivity” (i.e., regional development cannot escape from its history). Economic phenomena are not only dependent on current conditions, but also influenced and constrained by past historical conditions of the event (R.A. Boschma and Frenken, 2006), and the causes include the impact of natural resources, the sunken costs of local assets and infrastructure, the spillover effect of industrial-technology externalisation, and the technological lock-in effect (Martin and Sunley, 2006). Industrial development emphasises the path dependence of technological relatedness, and knowledge spillovers can only occur between industries with strong technological relatedness. Neffke et al. (2011) found that regional diversity exhibits a significant path-dependence process through a study of data on industrial firms in 70 regions in Sweden, where the entry of a new industry is influenced by the preexisting economic structure of the region; further, if the industry is located in a more marginal position in the regional industrial structure, then the probability of its exit is higher. Moreover, the importance of technological relatedness for the formation of new industries has been confirmed at the industry, city, regional, and national levels (Essletzbichler, 2015; Frenken et al. 2007).

Based on the theoretical basis of path dependence, university science and technology parks play the role of a bridge, linking universities to the local knowledge structure, and incubatees in the parks are able to move into a central position in the regional industrial structure by combining their knowledge with that provided by other local technological affiliates to obtain knowledge spillovers (Colombo and Delmastro, 2002; Lee et al. 2001; Phelps et al. 2012). In Diez-Viel and Montoro-Sanchez’s (2016) study of the Madrid Science Park, the authors confirmed that sharing in the same area promotes the frequency of interactions and knowledge diffusion between local firms and universities.

Agglomeration effect

The agglomeration effect stems from spatial concentration among firms, and the high correlation of spatial proximity among firms fosters knowledge spillovers, specialisation, and labour markets, creating agglomeration economies (Porter, 2000; Scott, 1988). In the monopolistic-competition model, Krugman (1991) used the interaction between increasing returns to scale and markets to explain the endogenous dynamics of spatial agglomeration. However, the evolution of economic phenomena over time cannot be explained because the time dimension was not introduced. Therefore, EEG argues that the formation of industrial clusters comes from the entry of firms, and the more local the firms, the more new entrants; and at the same time, the high entry rate of new entrants guides local firms’ entrepreneurship through the demonstration effect (Stuart and Sorenson, 2003; Wenting and Frenken, 2011). In a study of clustering in science parks, researchers found that university science parks have contributed to the geographical concentration of a range of specialised firms from an economic geography perspective (Koh et al. 2005). Similarly, at the meso level, the concentration of science parks in a region also contributes to knowledge sharing, talent mobility, and competitive cooperation among universities, laboratories, and firms (Opper and Nee, 2015; Sun and Lee, 2013).

Local institutions

In the controversy over the homogeneity of university science parks, most parks avoid the local characteristics of the institutions, especially in China’s model of progressive regional reform and development, resulting in significant regional institutional differences. Political decision-making, which determines the establishment of public resources and norms, is also reflected in the important opportunity conditions for the formation of new industries and the impact on business practices. In recent years, scholars have gradually introduced institutional variables into EEG such as policy arrangements in the German software industry that manifested in coevolutionary effects on technological innovation (Strambach and Halkier, 2013), the regulation of design professions in Paris that limited the growth of the advertising and design industry (Wenting and Frenken, 2011), and the important impact of institutions on the formation of cultural and creative industries in national to local scales (Gong and Hassink, 2017). In Spain, the early construction of science parks was not related to the government until 1999, when, with the support of the central and local governments, science parks experienced significant expansion and became the current main form of R&D (Rocio Vasquez-Urriago et al. 2016). In contrast, in the construction of university science parks in China, provincial science and education administrations proposed the identification of national university science parks to the State Council’s science and education administrations, in which the government clearly played a leading role.

Method and materials

This study adopted the hybrid method combining case study, inductive summarization, and exploratory theoretical analysis, taking China as a typical case. We took the 115 national university science parks in China as samples, employing GIS spatial analysis to map their nationwide distribution patterns. By integrating regional economic, educational, and policy characteristics with theoretical frameworks from university science park research, we identified common driving mechanisms and categorized typical development models. Methodologically, this approach offered three distinct advantages: First, its comprehensive spatial analysis of China’s university science parks mitigates the inherent selection bias in traditional case studies, ensuring representativeness across diverse regional contexts. Second, by synthesizing spatial data of science parks, local policy documents, and university technology-transfer pathways, we retained the institutional embeddedness of individual cases while enabling cross-regional pattern extraction, thereby bridging case-specific idiosyncrasies with generalizable insights into innovation ecosystem dynamics. Third, through an iterative comparison of developmental trajectories, we empirically validated how mechanisms such as firm spawning, path dependence, and agglomeration effects drive path creation in university science parks, revealing the interactive roles of contextual factors and evolutionary processes. This integrative methodology not only enhances the rigor of spatial analysis in innovation studies but also provides a systematic basis for understanding how institutional, educational, and locational attributes collectively shape the evolution of university science parks in transitional economies.

With its rapid economic growth and transformation development, the Chinese government has paid increased attention to scientific and technological innovation. The Chinese government has put forward the strategy of innovation-driven development. China’s government has developed many incentive policies over the years for university science parks, which are an important driver of science and technology innovation.

China, as a typical case for studying university science park development, stems from the multidimensional convergence of its institutional context, transformational dynamics, and practical realities. Institutionally, the tripartite interaction of a “strong government–large market–dense social network” creates a unique “policy experimentation arena” distinct from Western market-dominated models, where state-led strategies intersect with market mechanisms and social networks to foster adaptive institutional ecosystems. Transformationally, China’s incremental reforms generate substantial institutional accumulation and an “institutional leverage” effect, offering a dynamic perspective to observe the coevolution of government, universities, and enterprises through evolving governance frameworks that balance top-down design with bottom-up innovation. Practically, the Chinese experience challenges neoclassical market centralism by positioning the government as a “meta-governor” mediating market efficiency and societal goals, providing empirical grounding for technological gain in emerging economies through the coordination of innovation resources. This contextual specificity highlights how the interplay of institutional, transformational, and practical dimensions shapes a distinctive setting for analyzing science-park evolution, bridging local institutional realities with global theories of innovation in transformative economies.

The Measures for the Identification and Management of National University Science Parks, issued by China in 2010, defined national university science parks as

organizations that rely on universities with strong scientific research strengths, combine the advantages of comprehensive intellectual resources of the universities with other advantageous resources of the society, and provide platforms and services to support the transformation of scientific and technological achievements of universities, the incubation of high-tech enterprises, the cultivation of innovative and entrepreneurial talents, and the integration of industry, academia and research.

At the same time, the Measures stipulated that national university science parks recognized by China’s government should have more than 15,000 m2 of space, with more than 50 enterprises under incubation, and that 50% of enterprises in the parks should have a substantive connection with the relying university. National university science parks are exempted from business tax, income tax, property tax, and urban land-use tax for a certain period from the date of their accreditation, and the local government provides the necessary support for the construction and development of the national university science parks. As a result of the various preferential policies and support measures enjoyed by national university science parks, they have received a positive response from colleges and universities and are developing rapidly.

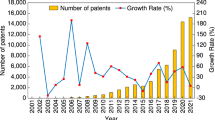

Northeastern University established China’s first university science park in Shenyang in 1988. China’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and Ministry of Education (MOE) have recognized ten batches of 115 national university science parks. This was the main research object of this study. The data and policy documents for this study were obtained from the China Torch Statistical Yearbook, compiled by MOST, and MOST and the People’s Republic of China MOE websites. The geographical location information of university science parks comes from the address information published on the official website of each science and technology park. Thus, we obtained a complete list and geographical location information of China’s national university science parks and were able to map their nationwide distribution patterns.

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of China’s national university science parks, showing a decreasing distribution pattern from east to west, forming the aggregation areas of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei and the Yangtze River Delta, as well as the subaggregation areas of Jilin, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Gansu, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Hubei, Jiangxi, and Guangdong.

Development model of university science parks in China

In long-term practice, regions have formed a diversified development model of university science parks with special characteristics in the context of local conditions in China. The development model of university science parks is mainly determined by the integrated effect of different factors, which can be divided into three development models: university-driven, university–government cooperation, and local dependence. The driving factors of university science parks are not independent of each other, but rather have a continuous interaction. In addition, regional economic development and the financing environment play an important role in the development of university science parks at all stages.

The university-driven development model

Driven by the benefits of university spin-offs and agglomeration, Tsinghua University Science Park, Peking University Science Park, and Zhejiang University Science Park represent this development model. University science parks are based on the talent and discipline advantages of the university and have formed a development path that relies on the characteristics of the university. Universities facilitate the transfer of laboratory technologies to enterprises in science parks through patent licensing, assignment, or authorization, providing a technical foundation for park-based firms, especially startups, to directly commercialize. This practice offers dual benefits: it not only shortens the R&D cycle and reduces the cost of technology acquisition for enterprises, but it also attracts entrepreneurial teams to science parks with the commercial potential of university patents, thereby forming a closed-loop ecosystem of a “patent–entrepreneurship–industry.” The long-established virtuous cycle between Stanford University and Silicon Valley serves as a quintessential example of successful university–industry collaboration in the United States.

In the transfer of scientific research results to the industrialisation of electronic information, biopharmaceuticals, new energy, digital economy, new materials, and other advantageous disciplines of universities, several excellent high-technology enterprises were born, represented by Tsinghua Tongfang, Peking University Founder, and United Mechanical & Electrical. For small- and medium-sized incubatees in the park, Tsinghua University Science Park provides the sharing of scientific-research laboratories and other infrastructures in the university, reducing the cost through sharing, giving full play to the intensive and professional advantage, and reducing the financial pressure in the early stage of the enterprise. At the same time, through the construction of “one university with multiple parks,” the disciplinary advantages of university science parks spread to other regions. For example, Tsinghua University Science Park has built subparks in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangxi, Xi’an, and nearly 30 cities; Peking University Science Park covers Nanjing, Guangzhou, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, and Silicon Valley in the United States; and Zhejiang University Science Park has set up subparks in Ningbo, Changxing, Wenzhou, and other cities.

With the successful development of university science parks in China, major universities have begun to actively explore the construction model of university science parks. Twenty-six university science parks, including Peking University, Tsinghua University, Beihang University, and Beijing Institute of Technology, have formed a more concentrated geographic agglomeration in Beijing’s Haidian District, generating spatial agglomeration benefits and strengthening knowledge sharing, talent flow, and competitive cooperation among universities, laboratories, and enterprises. According to the Beijing Municipal Three-Year Action Plan to Promote the Construction of the Belt and Road, only the Zhongguancun area has gathered 30% of the national key laboratories. The technology overflow between universities, research institutes, and enterprises has accelerated through cooperation and coconstruction. In addition, university-science-park alliances are an important model of cooperation and knowledge flow. The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei University Science Park Alliance and Zhejiang Province University Science Park Alliance have established a mechanism for sharing the resources of universities in the region, further enhancing the interactive platform for industry–university research between universities.

The university-driven development model positions the disciplinary strengths and resource agglomeration of top-tier universities as the core driver. Drawing on the research capabilities of the university's “parent institution,” it systematically converts the scientific outputs of advantageous disciplines into industrial applications through patent management, technology transfer, and incubation services, forming a vertical transformation chain of “discipline–technology–enterprise.” Its primary advantage lies in the high-level integration of academic resources: universities reduce startup costs through shared laboratories, interdisciplinary expert teams, and alumni networks, while the prestige of renowned institutions accelerates market trust and capital accumulation. However, this model entails notable limitations. Overreliance on a single university may foster disciplinary insularity that impedes cross-field collaboration; misalignment between academic research priorities and market demands can dramatically undermine the efficiency of technological translation. The model’s success hinges on two critical factors: on one hand, the proactive alignment of university-discipline planning with emerging industrial needs; on the other hand, the adaptive integration of market mechanisms. A disconnection between these elements risks create a paradox where robust academic foundations fail to generate commensurate industrial outcomes, a scenario often characterized as “strong academia, weak industry.”

The university–government-cooperation development model

The university–government-cooperation development model refers to an operation and management model in which universities and local governments jointly build science and technology parks. Through cooperation, the government is responsible for the construction of public infrastructure, and universities operate and manage the parks. Relying on the education, intelligence, and scientific research resources of universities, local governments provide support in taxation, financing, and policies to realize the industrialization and agglomeration of scientific-research achievements in university science parks.

For example, Nanjing University–Gulou University Science Park was developed by Nanjing University, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Hohai University, and the Nanjing Gulou District Government. The Gulou District Government initially invested 20 million RMB in the development of science parks, and Nanjing University of Technology, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, and China Pharmaceutical University jointly built a university science park through the transformation of science-and-technology resources. The local government is developing the National University Science Park in Henan Province with Zhengzhou University, Henan Agricultural University, Henan University of Technology, and Zhengzhou University of Light Industry. The local government has given greater support to enterprises in the park in policies, projects, and funds. In addition, the Donghu High-Tech Zone National University Science Park in Wuhan, the Changzhou National University Science Park, and the Beibei National University Science Park in Chongqing were all built on this model.

Collaborative partnerships between local governments and multiple universities characterize the university–government-cooperation development model, whereby governments undertake infrastructure investment and policy design, and universities contribute disciplinary expertise. Through systematic integration of cross-university resources—laboratory facilities, research teams, and intellectual property—this model fosters the formation of interdisciplinary technology clusters, thereby facilitating regional industrial upgrading. Its primary strengths lie in two interrelated dimensions: the horizontal expansion of resource pooling across academic institutions, which mitigates the narrowness of single-university innovation; and the institutional stability provided by government policy, which reduces market uncertainties for enterprises and accelerates agglomeration economies. However, the model confronts significant governance challenges. Coordination costs escalate with the number of stakeholders, as interuniversity rivalries and misaligned policy objectives, such as divergent metrics for academic excellence versus industrial output, often strain collaborative efficacy. Empirical evidence from failed cases highlights that ambiguous roles and responsibilities among governmental agencies, universities, and enterprises are the root cause of inefficiency, underscoring the necessity for formalized governance frameworks. Such frameworks must explicitly define institutional mandates, establish transparent communication mechanisms, and align incentive structures to ensure congruence between academic-research trajectories and regional-development priorities.

The local-dependence development model

Driven by path dependence, this development model invests the scientific research achievements of universities into related industries with local industrial advantages to obtain the support of regional knowledge, resources, and capital. Jilin University Science Park, Southeast University Science Park, Liaoning National University Science Park, and Harbin Engineering University Science Park represent this model.

Jilin Province has a large proportion of traditional farming, with a grain output of 38.78 billion kg in 2019, accounting for 41.2% of the country’s incremental output. At the same time, the automobile manufacturing industry has formed a more complete automobile-industry system with China FAW GROUP Corporation as the leader, and the brand involves Hongqi, Jiefang, Bestune, Volkswagen, and Toyota. Therefore, Jilin University Science Park has specially set up modern agriculture and biotechnology parks and automotive technology parks in the planning stage to ensure the transformation of scientific research results into incubation. As a nationally important comprehensive industrial base, Nanjing has formed an industrial structure with electronic information, petrochemicals, automobile manufacturing, and steel as the pillars. Therefore, Southeast University Science Park, Nanjing University of Science and Technology Science Park, and Nanjing Tech University Science Park also focus on the above-mentioned industries in the form of participating holdings and joint research. Liaoning National University science park closely follows the development strategy of Liaoning’s old industrial base and vigorously develops the equipment-manufacturing industry and the emerging industries represented by electronic information, biopharmaceuticals, and marine aquaculture. Harbin Engineering University's science park has developed industries related to information technology and national defense. Relying on the local industrial structure, the development of the park takes relevant industries offering a comparative advantage as the direction of evolution and realises the industrial transformation of the university’s technological advantages and resources.

The deep binding of university research to regionally advantageous industries characterizes the local-dependence development model. By focusing on the needs of the local industrial structure, this model drives indigenous industrial upgrading through targeted technological R&D, forming a closed-loop mechanism of “local demand–university innovation–industrial feedback.” Its core strength lies in strong industrial adaptability: local governments support science parks through sector-specific policies such as preferential land allocation and financial subsidies, while university technologies directly translate into regional economic applications, achieving mutually beneficial social and economic benefits. However, the model confronts notable structural limitations. Excessive reliance on traditional industries often leads to path curtailment, exemplified by science parks in Northeast China that missed opportunities in emerging sectors due to prolonged focus on heavy industry. Additionally, the constrained capacity of regional markets can significantly constrict the commercialization potential of technologies, limiting their scalability beyond local contexts.

Driving factors of university science parks in China

Based on the theory of EEG, and considering the influence of production factors such as regional economic differences and financing environments under the factor-endowment hypothesis, we identified the driving factors of the development of university science parks in China, including university spin-offs, path dependence, the agglomeration effect, local institutions, regional economic development, and the financing environment (Fig. 2).

University spin-off

The location choice of university science parks is influenced by the spin-off process and mainly relies on the scientific and educational intellectual resources of universities. Science parks realize the knowledge reserves and scientific and technological achievements of universities through the provision of places, technology transfer, and assistance in financing, thereby facilitating the close integration of high-technology resources in the market and promoting regional development. Therefore, the development of university science parks depends on the layout of existing universities. Given that the 211 Project was launched in 1995 and the accreditation of national university science parks commenced in 2001, this study, grounded in the principles of research timeliness and policy relevance, offers an empirically anchored analysis of the historical correlation between university resource agglomeration and science-park development during this formative period. Comparing the distribution of university science parks and Project 211 universities (national key universities in China), we found that the coupling rate is as high as 80% (Fig. 3). This verifies the dependence of university science parks on universities. With technical and talent support from universities, enterprises in the parks promote the codevelopment of university science parks, universities, and enterprises in an industry–university-research combination model.

In the development of university science parks, on one hand, the routines of the university have been consigned to the operation and management of the science park, and on the other hand, through the construction of the park in different places, the successful experience of the science park has gradually spread to other areas. For example, Tsinghua University Science Park has built subparks in Beijing, Shanghai, Xi’an, and nearly 30 other cities; Zhejiang University Science Park has established subparks in Ningbo, Changxing, and Wenzhou. Through the construction of subparks, technology, and management output, university science parks have achieved a wider spread of talent, technology, and industry.

Path dependence

Regional industrial development rests on path dependence, determined by the technological relatedness of the industrial structure. The production of related products often requires similar production factors and knowledge technology between industries. If the direction of industrial development in the university science park has a high degree of technological relevance to the university’s advantageous disciplines and local advantageous industries, it is more likely to have the resource endowment required for industrial development; the conversion rate of scientific and technological achievements will be higher.

In Liaoning Province, for example, equipment manufacturing, the petrochemical industry, and the metallurgical industry occupy a larger proportion of industrial products (Fig. 4). As a result, Northeastern University National University science park in Liaoning has a high output of industrialisation and transformation of mechanical engineering, materials science, automation, and metallurgical engineering.

Agglomeration effect

The location selection of university science parks has an agglomeration effect. When a city has more university science parks, science parks can benefit from the sharing of professional knowledge and human resources. Through the clustering between science parks and enterprises in the parks, new routines in enterprises constantly emerge, the flow of knowledge and innovation accelerates, and the spillover effect realises the transformation and upgrading of relevant industries in the form of talent clustering and knowledge concentration, ultimately promoting regional development. Zhongguancun in Beijing, for example, has a concentration of 26 university science parks, 112 state-level key laboratories, and 206 national research institutes. As the most densely populated region in China in science, education, and high-level talent, Zhongguancun has established a network for innovation and cooperation in building joint laboratories, technology transfer, and science and technology humanities exchanges based on the geographic clustering of science and technology enterprises. Six key industrial clusters have formed, including next-generation Internet, mobile Internet, satellite applications, biohealth, energy-saving and environmental protection, and rail transportation. In 2017, the average land output rate was as high as 10.86 billion yuan per square kilometer. Simultaneously, the model of “one university with multiple parks” and the university–science-park alliance can concentrate on scientific research, talent, and experimental equipment of universities, thereby realizing the clustering effect of science parks and increasing returns to scale.

Local institutions

The development of university science parks depends on the policy support of local governments. In the past, the public sector joined in the establishment of new institutions of knowledge, resources, and industry, and institutions often showed a very close coevolutionary relationship with the evolution of economic agents (Maskell and Malmberg, 2007; Sotarauta and Pulkkinen, 2011). In the construction of science parks, land-development rights are an important tool for spatial planning, reflecting the development direction under the guidance of local policy. An indicator of the average site area of university science parks, we used the China Torch Statistical Yearbook to measure the support of local governments for science parks. We found that university science parks built with government participation tend to be larger in construction scale than those built by the universities alone. Government participation in the construction of university science parks can provide enterprises with preferable infrastructure and support; at the same time, government participation can also give rise to the problem of mismatched power and responsibility.

At the macro level, university science parks aim to realize the functions of social service and combine industry with the academic research of universities. Therefore, national policies guide every stage of the development process of Chinese university science parks. Construction of national university science parks started by MOST and MOE developed rapidly after the 10th Five-Year Plan, which explicitly included the construction of national university science parks in the local economic and social development plan. As a result, various regions introduced financial subsidies, tax incentives, and other supportive policies to promote the development of local university science parks.

Notably, the policy logic underpinning China’s university science parks differs fundamentally from traditional economic incentive models. For example, China’s Special Economic Zones policy frameworks primarily promote export-oriented growth through measures such as tax exemptions and land concessions, centered on strategies of deep integration into economic globalization. In contrast, China’s university science parks adopt an endogenous-development paradigm, where policy incentives focus on constructing innovation ecosystems. Through targeted fiscal subsidies and tax preferences, these policies nurture university-spawned enterprises, driving regional economies toward knowledge-intensive transformation.

Regional economic development and the financing environment

China is a vast country with large disparities in economic base and resource endowment among regions, and its economic development is obviously unbalanced. By comparing the revenues of incubatees in university science parks in China’s provinces, we found that most regions with better economic performance of university science parks are located in the eastern developed region. The top five provinces (Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shanghai, and Beijing) all have high levels of economic development. Economic development can reflect regional support for science parks in market demand, public infrastructure, and labour resources.

University science parks are functionally positioned as innovation and entrepreneurship platforms for small- and medium-sized science and technology enterprises. The key challenges facing the development of small- and medium-sized enterprises are financing difficulties and high capital costs. A university science park provides start-up funds and shareholding through the cooperation of the university, the government, and enterprises, which can solve initial financing problems to a large extent. According to data from the 2018 China Torch Statistical Yearbook, the total start-up funds of Beijing, Jiangsu, and Shanghai science parks were 1.091 billion yuan, 332 million yuan, and 134 million yuan, respectively, ranking among the top three in China, and the performance of the university science parks in the three provinces ranked among the top five in China. In contrast. The total start-up funds of Shanxi, Ningxia, Guizhou, and Xinjiang were 5 million yuan, 5 million yuan, 4.3 million yuan, and 3 million yuan, respectively, and their performances ranked lower.

Interaction between the driving factors

The driving factors of university science parks are not independent and separate; rather, they have interaction and synergy that form the structure and model of university science parks in their long-term evolution. As shown in Fig. 2, university spin-offs, regional economic development, and the financing environment together shape the path-dependent foundation of university science parks. The industrial-development direction of university science parks is often closely related to the dominant disciplines of the university, and the university’s disciplinary advantages promote the transformation of scientific and technological achievements and industrial upgrading. University science parks usually choose to match the industrial foundation and development needs of their region to obtain more market opportunities. Spin-off paths of local universities, the existing development paths, the level of regional economic development, and the financing environment usually influence regional institutions developing university science parks, ensuring policies can effectively promote scientific and technological innovation and socioeconomic development. Local governments formulate appropriate support policies based on the universities’ superior disciplines and R&D strengths, the region’s resource-factor endowment, and the current status and potential of local economic development. University spin-offs and regional institutions play an important role in the agglomeration effect. Universities, as an important source of knowledge and technological innovation, have a strong ability to transform their scientific research results, attracting related industries to gather around them, forming industrial clusters and economies of scale. Local governments usually adopt a series of strategies to promote the formation and development of industrial clusters, including land supply, tax incentives, and special funds to optimize the industrial structure, promote the construction of regional brands, and enhance the strength of the regional economy.

University–science-park growth is a dynamic and intricate process, impacted by a number of interrelated driving factors. A change in one factor frequently triggers a change in the entire environment. To determine the factors that influence university science parks, local government must methodically consider the intensity and the dynamic changes of the driving factors, analyze the park’s development from a dynamic perspective using systematic thinking, and create development measures that are effective and current.

Discussion

In this study, we engaged in theoretical dialogue with extant literature by expanding the conceptualization of dynamic mechanisms driving university–science-park development, critically reconstructing the role of institutional contexts. Early researchers emphasized universities as “technological intermediaries” (Patton and Marlow, 2011), a perspective that aligns with this paper’s focus on the vertical transformation of disciplinary resources through university spin-offs as a core driver of innovation. Although most research teams acknowledged the significance of institutions in shaping science-park evolution (Hamon et al. 2024; Henriques et al. 2018; Tang et al. 2014), they have not adequately explicated the uneven power structures and nonlinear causal relationships embedded in the institutional environments of emerging economies. By integrating insights from path dependence theory and regional institutional analysis, in this study, we uncovered how administrative interventions may induce structural rigidities in science-park development: although policy tools such as preferential land allocation and tax incentives effectively accelerate the agglomeration of innovation resources, consistent with Hamon et al.’s (2024) policy-driven framework, their long-term efficacy is mediated by path lock-in effects. Government support for traditional industries, while enhancing short-term adaptability to regional economic needs, can entrench “institutional sunk costs” through overreliance on historical industrial trajectories. As technological disruptions (e.g., new energy vehicles reconfiguring the automotive value chain) challenge established sectors, delayed policy adjustments and slow academic realignments toward emerging fields can trap science parks in a state of “adaptive rigidity,” where institutional inertia overrides the adaptive capacity enabled by university spin-offs.

Existing literature, often anchored in the triple-helix model, tends to emphasize balanced collaboration among universities, governments, and industries while overlooking the critical role of regional embeddedness (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 1997). In this study, we addressed this gap by adopting an EEG framework to demonstrate how regional market heterogeneities—encompassing economic development levels, industrial structures, and financing ecosystems—shape the boundaries of the potential for technology commercialization. Despite central-government efforts to foster innovation agglomeration through policy coordination, regional capacity constraints frequently emerge as “spatial bottlenecks.” In central and western China, for example, science park enterprises leveraging technology transfers from university spin-offs can achieve initial product development but face substantial hurdles in scaling up, due to low-end local industrial chains, limited capital mobility, and insufficient supporting industries. These regional market deficiencies, manifesting as weak demand or missing production networks, highlight how institutional interventions must be contextualized within localized socioeconomic landscapes to avoid mismatches between technological supply (facilitated by university spin-offs) and market demand.

Conclusion

University science parks are an important part of the national innovation system, playing a key role in cultivating innovative and entrepreneurial talent, transforming scientific and technological achievements of universities, incubating high-technology enterprises, and accelerating regional economic growth. Over time, China has formed a diversified development model of university science parks with characteristics embedded into local conditions, including university-driven, university–government cooperation, and local-dependence development models. In this study, we expanded the research on university science parks from the perspective of economic geography and introduced the concepts of spin-off, path dependence, agglomeration effect, and local institutions. Considering the influence of regional economic differences and the financing environment under the factor-endowment hypothesis, in this study, we constructed driving mechanisms for the development of university science parks.

Results show that the driving factors of university science parks are not independent of each other; rather, they form the structure and behaviour of university science parks in a continuous interaction. Regional economic development and the financing environment play a key role in the various development stages of university science parks. An important recommendation is to adopt targeted policies and a development model of university science parks according to local conditions, resource endowments, and the financing environment.

In this study, we examined the development model and driving mechanism of university science parks in China, extending the research on the evolution process of university science parks. However, considering the regional heterogeneity, scholars have yet to more deeply question the spatial dynamic data of enterprises in the parks to reveal the influential mechanism of the development of university science parks from different scales and perspectives. In addition, follow-up studies must use more quantitative methods and cross-country comparative studies.

Data availability

Data is provided as a supplementary file.

References

Aernoudt R (2004) Incubators: tool for entrepreneurship? Small Bus Econ 23(2):127–135

Albahari A, Perez-Canto S, Barge-Gil A, Modrego A (2017) Technology Parks versus Science Parks: does the university make the difference? Technol Forecast Soc Change 116:13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.012

Anton-Tejon M, Barge-Gil A, Martinez C, Albahari A (2024) Science and technology parks and their heterogeneous effect on firm innovation. J Eng Technol Manag 73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2024.101820

Arthur WB (1994). Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press

Asheim BT, Boschma R, Cooke P (2011) Constructing regional advantage: platform policies based on related variety and differentiated knowledge bases. Reg Stud 45(7):893–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.543126

Barbera F, Fassero S (2013) The place-based nature of technological innovation: the case of Sophia Antipolis. J Technol Transf 38(3):216–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-011-9242-7

Bathelt H, Kogler DF, Munro AK (2010) A knowledge-based typology of university spin-offs in the context of regional economic development. Technovation 30(9-10):519–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2010.04.003

Benner M (2022) Retheorizing industrial-institutional coevolution: a multidimensional perspective. Reg Stud 56(9):1524–1537. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1949441

Bergek A, Norrman C (2008) Incubator best practice: a framework. Technovation 28(1–2):20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2007.07.008

Boschma R, Coenen L, Frenken K, Truffer B (2017) Towards a theory of regional diversification: combining insights from Evolutionary Economic Geography and Transition Studies. Reg Stud 51(1):31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

Boschma R, Frenken K (2011) The emerging empirics of evolutionary economic geography. J Econ Geogr 11(2):295–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq053

Boschma R, Frenken K, Bathelt H, Feldman M, Kogler D (2012) Technological relatedness and regional branching. In: Bathelt H, Feldman MP, Kogler DF (eds) Beyond territory: dynamic geographies of knowledge creation, diffusion and innovation. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, London, pp 64–68

Boschma RA, Frenken K (2006) Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. J Econ Geogr 6(3):273–302

Boschma RA, Wenting R (2007) The spatial evolution of the British automobile industry: does location matter? Ind Corp Change 16(2):213–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm004

Bruneel J, Ratinho T, Clarysse B, Groen A (2012) The evolution of business incubators: comparing demand and supply of business incubation services across different incubator generations. Technovation 32(2):110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.11.003

Buenstorf G, Klepper S (2009) Heritage and agglomeration: the Akron tyre cluster revisited. Econ J 119(537):705–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02216.x

Cainelli G, Iacobucci D (2016) Local variety and firm diversification: an evolutionary economic geography perspective. J Econ Geogr 16(5):1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv040

Coe NM (2011) Geographies of production I: an evolutionary revolution? Prog Hum Geogr 35(1):81–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364281

Colombo MG, Delmastro M (2002) How effective are technology incubators? Evidence from Italy. Res Policy 31(7):1103–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(01)00178-0

Cooke P, Leydesdorff L (2006) Regional development in the knowledge-based economy: the construction of advantage. J Technol Transf 31:5–15

Diez-Vial I, Fernandez-Olmos M (2015) Knowledge spillovers in science and technology parks: how can firms benefit most? J Technol Transf 40(1):70–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9329-4

Diez-Vial I, Montoro-Sanchez A (2016) How knowledge links with universities may foster innovation: the case of a science park. Technovation 50-51:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2015.09.001

Durao D, Sarmento M, Varela V, Maltez L (2005) Virtual and real-estate science and technology parks: a case study of Taguspark. Technovation 25(3):237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-4972(03)00110-x

Essletzbichler J (2012) Generalized Darwinism, group selection and evolutionary economic geography. Z Wirtschaftsgeogr 56(3):129–146

Essletzbichler J (2015) Relatedness, industrial branching and technological cohesion in US metropolitan areas. Reg Stud 49(5):752–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.806793

Etzkowitz H, Leydesdorff L (1997) Universities and the global knowledge economy: a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Pinter, London

Fischer MM, Varga A (2003) Spatial knowledge spillovers and university research: evidence from Austria. Ann Reg Sci 37(2):303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001680200115

Frenken K, van Oort F, Verburg T (2007) Relate variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Reg Stud 41(5):685–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120296

Gilsing VA, van Burg E, Romme AGL (2010) Policy principles for the creation and success of corporate and academic spin-offs. Technovation 30(1):12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.07.004

Goldfarb B, Henrekson M (2003) Bottom-up versus top-down policies towards the commercialization of university intellectual property. Res Policy 32(4):639–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(02)00034-3

Gong H, Hassink R (2017) Exploring the clustering of creative industries. Eur Plan Stud 25(4):583–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1289154

Gredel D, Kramer M, Bend B (2012) Patent-based investment funds as innovation intermediaries for SMEs: in-depth analysis of reciprocal interactions, motives and fallacies. Technovation 32(9-10):536–549

Guadix J, Carrillo-Castrillo J, Onieva L, Navascues J (2016) Success variables in science and technology parks. J Bus Res 69(11):4870–4875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.045

Hamon LAS, Ruiz Penalver SM, Thomas E, Fitjar RD (2024) From high-tech clusters to open innovation ecosystems: a systematic literature review of the relationship between science and technology parks and universities. J Technol Transf 49(2):689–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09990-6

Harris JL (2021) Rethinking cluster evolution: actors, institutional configurations, and new path development. Prog Hum Geogr 45(3):436–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520926587

Hassink R, Isaksen A, Trippl M (2019) Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Reg Stud 53(11):1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

Hassink R, Klaerding C, Marques P (2014) Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Reg Stud 48(7):1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

Henriques IC, Sobreiro VA, Kimura H (2018) Science and technology park: future challenges. Technol Soc 53:144–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.01.009

Huang K-F, Yu C-MJ, Seetoo D-H (2012) Firm innovation in policy-driven parks and spontaneous clusters: the smaller firm the better? J Technol Transf 37(5):715–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9248-9

Jakobsen S-E, Uyarra E, Njos R, Floysand A (2022) Policy action for green restructuring in specialized industrial regions. Eur Urban Reg Stud 29(3):312–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211049116

Klepper S (2007) Disagreements, spinoffs, and the evolution of Detroit as the capital of the US automobile industry. Manag Sci 53(4):616–631

Klepper S (2010) The origin and growth of industry clusters: the making of Silicon Valley and Detroit. J Urban Econ 67(1):15–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.004

Kogut B, Zander U (2003) Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. J Int Bus Stud 34(6):516–529. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400058

Koh FCC, Koh WTH, Tschang FT (2005) An analytical framework for science parks and technology districts with an application to Singapore. J Bus Ventur 20(2):217–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.002

Krugman P (1991) Increasing returns and economic-geography. J Political Econ 99(3):483–499. https://doi.org/10.1086/261763

Lee C, Lee K, Pennings JM (2001) Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: a study on technology-based ventures. Strateg Manag J 22(6-7):615–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.181

Lew YK, Khan Z, Cozzio S (2018) Gravitating toward the quadruple helix: international connections for the enhancement of a regional innovation system in Northeast Italy. R D Manag 48(1):44–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12227

Liberati D, Marinucci M, Tanzi GM (2016) Science and technology parks in Italy: main features and analysis of their effects on the firms hosted. J Technol Transf 41(4):694–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9397-8

Lofsten H, Klofsten M (2024) Exploring dyadic relationships between Science Parks and universities: bridging theory and practice. J Technol Transf 49(5):1914–1934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-024-10064-y

Lopes JM, Gomes S, Ferreira JJM, Dabic M (2025) Driving regional advancement: exploring the impact of science and technology parks in the outermost regions of Europe. Eur J Innov Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejim-03-2024-0278

Lynn LH, Kishida R (2004) Changing paradigms for Japanese technology policy: SMEs, universities, and biotechnology. Asian Bus Manag 3:459–478

Martin R, Sunley P (2006) Path dependence and regional economic evolution. J Econ Geogr 6(4):395–437

Martin R, Sunley P (2007) Complexity thinking and evolutionary economic geography. J Econ Geogr 7(5):573–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm019

Martin R, Sunley P (2015) Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography? Reg Stud 49(5):712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.899431

Maskell P, Malmberg A (2007) Myopia, knowledge development and cluster evolution. J Econ Geogr 7(5):603–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm020

McCann BT, Folta TB (2008) Location matters: where we have been and where we might go in agglomeration research. J Manag 34(3):532–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316057

Mohammadi N, Karimi A, Meidute-Kavaliauskiene I, Aghazadeh H (2024) Megatrends in science and technology parks and areas of innovation: co-citation clustering. J Sci Technol Policy Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/jstpm-02-2024-0050

Morrison A, Boschma R (2019) The spatial evolution of the Italian motorcycle industry (1893–1993): Klepper’s heritage theory revisited. Ind Corp Change 28(3):613–634. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty019

Neffke F, Henning M, Boschma R (2011) How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Econ Geogr 87(3):237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

Nosella A, Grimaldi R (2009) University-level mechanisms supporting the creation of new companies: an analysis of Italian academic spin-offs. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 21(6):679–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320903052657

Oerlemans LAG, Meeus MTH (2005) Do organizational and spatial proximity impact on firm performance? Reg Stud 39(1):89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320896

Opper S, Nee V (2015) Network effects, cooperation and entrepreneurial innovation in China. Asian Bus Manag 14(4):283–302. https://doi.org/10.1057/abm.2015.11

Patton D (2014) Realising potential: the impact of business incubation on the absorptive capacity of new technology-based firms. Int Small Bus J-Res Entrep 32(8):897–917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613482134