Abstract

A quarter of a century has passed since the late Terry Crowley summed up the academic consensus that the creole language Bislama poses no immediate threat to any of Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages. Does this remain true today? Since that time, evidence both quantitative and qualitative has been accumulating that indicates Bislama is indeed gaining ground at the expense of Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages. In a targeted review of this evidence, this article brings together and assesses the insights of linguists, ethnographers, and others on the causal mechanisms that explain an ongoing shift towards Bislama. It thereby provides both a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a provisional causal framework for understanding current threats, predicting future threats and, potentially, intervening to prevent future threats. Language endangerment and extinction is a global issue with devastating implications for communities worldwide—one which Vanuatu, the world’s most linguistically diverse country, has thus far remained resilient in the face of. However, this review of the available evidence warns that Bislama will continue to disrupt intergenerational transmission of Indigenous languages unless a suite of inter-related mechanisms can be counteracted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spurred by dire warnings in the early 1990s about the impending devastation of the world’s languages (e.g., Krauss, 1992), a debate surfaced over whether Vanuatu’s celebrated linguistic diversity was threatened by Bislama, the country’s lingua franca, which is based mainly on English. Predictions by Mühlhäusler (1987) and Dixon (1991) about the bleak future for Oceanic and Melanesian languages prompted Crowley, a specialist in Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages as well as Bislama, to argue in his influential review of the language situation in Vanuatu that “in no case is any indigenous language in any obvious immediate danger of being replaced by Bislama” (Crowley, 2000, p 125, though compare his later work, e.g. 2006a).

Crowley’s perspective here aligns with a view of Bislama that emphasises its underdog status: how it has been sidelined within Vanuatu and looked down upon as ‘broken English’ and ‘not a real language’ (Early, 1999; Lynch, 1996). Accordingly, much scholarship has sought to understand Bislama as a new Melanesian language that emerged from humble beginnings on the shipping lanes crisscrossing the South Pacific in the 19th century, amongst the Melanesians working the cotton and sugar plantations of Australia (from which it derives a common ancestry with Papuan Tok Pisin and Solomon Islands Pijin), and later on the colonial plantations of Vanuatu itself (for key works on the history of Bislama, see: Crowley, 1990; Keesing, 1988; Tryon and Charpentier, 2004). Research has outlined how Bislama was disparaged by Christian missionaries because it was ‘insufficient’ as a language of the heart (Crowley, 1990, p 171), an attitude that persisted into the 1960s and 1970s even as Bislama was adopted as the language of national politics in the movement for Vanuatu’s independence (Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, pp 285–286, p 410). It was Bislama’s status as a unifier across the divide between anglophones and francophones created by Vanuatu’s former colonial powers, the rivals Britain and France, that led to its institutionalisation as the ‘national language’ of the new independent state of Vanuatu in 1980 (Bolton, 1999b, pp 50–52). Yet this should not be confused with Bislama gaining much greater status. As Crowley (1990, p 4) explains, Bislama was employed primarily “to avoid divisive wrangling over whether it was to be French or English which would ‘win’.”

It might therefore seem unlikely for Bislama to pose much of a threat, given its historical perception as a “plantation language” used by those who are outcast or who leave their homes, families, and villages to earn cash instead of playing their part in their home communities (Crowley, 1990, p 352; Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, Chapter 8). Despite its constitutional recognition as the national language, in 1988 the Ministry of Education directed its staff to avoid using Bislama even when talking to gardeners and cleaners (Crowley, 1990, p 398). In 1995, the Education Minister authored an official directive warning that use of any language other than English or French in school classrooms would be treated as ‘professional misconduct’ (Lynch, 1996, pp 247–248). While some researchers did argue that Bislama’s sidelining was necessary for maintaining Vanuatu’s language diversity (meaning maintenance of both English and French alongside the Indigenous vernaculars; see Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, pp 419–421, pp 424–454), more agitated for an increased recognition and official use of Bislama as a respectable language in its own right (Crowley, 1996; Early, 1999; Lynch, 1996).

The argument advanced by Crowley and others is that contact with and use of Bislama does not threaten Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages. Instead, Bislama increases the range of linguistic options available to speakers, providing another communicative tool useful for meeting a particular range of sociolinguistic needs (Connell, 2020; Crowley, 1995, 2004; Lindstrom, 2007). Contact with new languages and multilingual environments indeed does not necessarily lead to language shift (Thomason, 2018; also Bromham et al. 2022). This is clearly the case in Vanuatu, which can claim to be the most linguistically diverse country on earth with respect to the number of Indigenous languages by population and by area (François et al. 2015, p 8; Crowley, 2000, p 50). Moreover, Vanuatu’s tradition of linguistic diversity—and the impressive multilingualism it requires of individual speakers—has been maintained for hundreds of years of migration, trade, and intermarriage. Of course, the situation in Vanuatu today is very different from that which existed prior to the institution of joint colonial rule by Britain and France, the reorganisation of social systems under Christian missionary influence, and the arrival of infectious diseases and Western weaponry that created widespread death and social collapse (see Lavender Forsyth and Atkinson, 2024). These factors certainly did have effects on Vanuatu’s indigenous languages. But Crowley and others point out it has not been the spread of Bislama, or indeed English or French, that has reduced Vanuatu’s linguistic diversity. Instead, the threat has come from larger Indigenous languages replacing smaller ones. This process is well-documented. The island of Erromango, for example, has just one Indigenous language today, whereas it used to have at least three (Crowley, 1997). Here, I present no rebuttal of this process. Instead, I review more recent evidence that a shift towards Bislama has emerged as an additional and increasingly threatening alternative route towards declining linguistic diversity in Vanuatu.

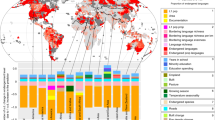

In 2009, Vanuatu’s National Bureau of Statistics released some data that reinvigorated debate over the threat posed by Bislama. The 2009 census asked respondents to state the main language of their household—either an Indigenous language or Bislama, or alternatively English or French. The question had been asked once before in 1999, so 2009 was the first time answers could be compared to a previous benchmark. This comparison shows that the percentage of households using Bislama as their main language increased and had done so at the expense of the percentage of households using an Indigenous language (Fig. 1; also François, 2012). This is not just an artefact of urbanisation (contra Connell, 2020; and Crowley, 1995, p 336). Even in rural Vanuatu, the percentage of households with an Indigenous main language decreased compared to the percentage of households using Bislama. Use of Bislama in the household plausibly increases the likelihood that children will grow up speaking it as a first language. Indeed, the most recent 2020 census data show that of the population who also speak an Indigenous language, Bislama is the first language for 14% (note the census only asked this question to individuals also able speak an Indigenous language), including more than one in ten people in rural areas, and of those aged 4–20 years old it is the first language of 20% or one in five (data provided by Vanuatu’s National Bureau of Statistics). These statistics tally with on-the-ground concerns expressed by many people within Vanuatu about Bislama (Love et al. 2019), with some accounts reporting “unanimous responses filled with concern for what many perceive as imminent indigenous language loss due to the rise of Bislama use among young children” (Shipman, 2008, p 95). While we are not aware of any comprehensive review of the evidence to update the picture presented by Crowley (2000), growing numbers of researchers’ field reports document that Bislama may indeed pose a threat to Indigenous languages in Vanuatu (e.g., Barbour et al. 2018; Budd, 2011; François, 2012; Gray, 2012; Guérin, 2008; Murray, 2018; Ridge, 2019; Takau, 2016; Walworth et al. 2021). Bislama has even been described in the national press as a ‘parasite language’ for its apparent role in interrupting the transmission of Indigenous languages (Tokona, 2020).

Graphs showing that from 1999 to 2009 the percentage of households with an Indigenous main language decreased and the percentage of households with Bislama as their main language increased, both in rural (A) and urban (B) settings. Note that, due to overall population increase, the raw number of households using an Indigenous language between 1999 and 2009 increased in rural areas and stayed roughly stable in urban areas. The most recent 2020 census did not include a question on the main household language. Data provided to the author by Vanuatu’s National Bureau of Statistics.

It is therefore imperative to understand the processes driving the apparent shift from Indigenous languages to Bislama. It remains true that compared to many other places around the world, Vanuatu has maintained impressive linguistic diversity (François et al. 2015), but this also means Vanuatu is a country with a great deal to lose. While it is therefore important to acknowledge the impressive resilience of Vanuatu’s language diversity, we must also understand the endangerment process before irreversible damage is caused and before communities face the manifold negative consequences that can result from language loss (Taff et al. 2018; Willans and Jukes, 2017). Vanuatu’s government has pledged to protect the country’s Indigenous languages (Department of Strategic Policy Planning and Aid Co-ordination, 2016), so a causal understanding of the endangerment process could help inform these policy aims.

Furthermore, the world is going through a major language extinction event that requires explanation. So far, large-scale analyses have identified common correlates of language endangerment across different contexts (Amano et al. 2014; Bromham et al. 2022), but our understanding of the causes of language endangerment remains less well developed. Causal inference demands researchers make assumptions about the nature of the system under study, and best practice is for these assumptions to be informed by domain-relevant expert knowledge (Bulbulia et al. 2021; McElreath, 2020).

For both these reasons, therefore, I here interrogate the factors that linguists, ethnographers, and others have proposed as explanations for the spread of Bislama at the expense of Indigenous languages. Following other researchers working in Melanesia, my analysis of this mostly qualitative research is as a set of empirically informed insights into potential mechanisms that have a great deal to contribute to debates about causal processes (Brandl and Colleran, 2024).

Defining ‘threat’

The claim that Bislama threatens Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages demands clarity about the nature of the threat. Ultimately, the gravest threat a language faces is being forgotten, often termed its ‘extinction’ (e.g., Nettle and Romaine, 2002). But linguists have also sought warning signs to identify languages that could face extinction in the future. The presence of such warning signs is termed ‘endangerment’. Of these signs, the clearest is when children stop using and learning a language, which interrupts its intergenerational transmission (Krauss, 2008; Lee and Van Way, 2016; Lewis and Simons, 2010; UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages, 2003). Beyond this criterion, different frameworks identify a great variety of warning signs. Some include the absolute number of speakers of the language, for instance, or community members’ attitudes about the language. To draw a clear line between language endangerment and its conjectured causes, and to avoid dependence on a single theoretical perspective, I will restrict endangerment here to mean interruption to a language’s transmission between generations. The ‘threat’ Bislama may pose is therefore an interruption to the intergenerational transmission of Indigenous languages.

Proximity to urban centres

As is clear in Fig. 1, the main household language is more likely to be Bislama in Vanuatu’s urban areas compared to its rural areas. A straightforward explanation for this is that Bislama is simply more widely used in urban life compared to rural life (Tryon, 2006, p. 107). One report finds that 93% of Ni-Vanuatu (i.e., Indigenous) youths surveyed in the capital, Port Vila, say that amongst friends they speak Bislama almost exclusively (Vanuatu Young People’s Project, 2008). Correspondingly, whereas in rural areas the use of Indigenous languages remains widespread, with 83% of rural Ni-Vanuatu reporting daily use, Indigenous languages are used much less in the cities, where only 34% of urban Ni-Vanuatu report daily use (VNSO, 2021, p 112). There is therefore an immediate pressure to learn Bislama to operate effectively in Vanuatu’s urban spaces. Observers describe how this social pressure results in the children of migrants in Port Vila learning Bislama as their first language (François, 2012, p 103; though this does not necessarily prevent children from also acquiring an Indigenous language, see Lindstrom, 2018, p 62). Similar effects of interruption to intergenerational language transmission have been observed in traditional villages situated close to Port Vila (Ridge, 2019, pp 84–85). Census statistics support this observation, with 19% of the Indigenous language-speaking population of peri-urban villages near Vila reporting Bislama as their first language (specifically, Mele, Ifira, Erakor, and Pango) compared to 31% of the overall urban population and 11% of the overall rural population (VNSO, 2020, pp 178–181).

The secondary question, then, is why Bislama is so widely used in the cities. This seems related to the cities’ histories as ‘foreign’ spaces. Only Port Vila (population 49,000) and the second city of Luganville (population 18,000) are classed as ‘urban’ by the National Bureau of Statistics. Both were founded by Europeans, and today they contain a great variety of people, both from overseas and from different islands in Vanuatu (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, pp 39–43). Compare this to the 78% of Vanuatu’s population that live in rural villages and hamlets, of whom 79% live on their customary (kastom in Bislama) ground (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, p. 15, 83). The cities are thus the places most influenced by the former colonial powers (Connell and Lea, 1994) and the areas closest to the cities are widely considered to be the places that have suffered the greatest loss of kastom, or Indigenous culture, worldview, and lifeways (Naupa, 2004, p 36; Philibert, 1992, p 128; Thieberger, 2006, pp 18–20). Given Bislama’s history as a language used in situations of contact with outsiders, and the colonial power asymmetry between foreigners and Indigenous Ni-Vanuatu (see Miles, 1998), it should not be surprising to find it most firmly established in the places where contact with outsiders has been greatest, in Port Vila and Luganville.

Another part of the explanation for the link between urban life and the shift towards Bislama and away from Indigenous languages, however, is likely that living in or near an urban centre introduces other factors that are themselves related to language endangerment, which I will discuss below. These include in-migration, access to formal education, access to technology for communication and transportation, and exposure to the forces of economic development. Proximity to an urban area would thus be associated with a shift towards Bislama due to the combined forces of the social pressure created by widespread use of Bislama in urban settings, which relates back to their history as places of contact with outsiders, and of exposure to downstream factors that are themselves products of urban living and which in turn promote Bislama’s spread. Nevertheless, as already noted, the shift towards Bislama must be explained not just in urban areas but in rural communities too.

In-migration

One of the explanations for the endangerment of Indigenous languages in Vanuatu most discussed by researchers is the degree of migration into a community, with higher numbers of migrants making usage and transmission of Indigenous languages less likely and instead incentivising the use of the lingua franca, Bislama. I have already noted this occurring in the discussion of proximity to urban centres, with city migrants shifting towards Bislama. However, in-migration does not only occur in cities, and researchers have argued that migration patterns are also important for explaining Bislama’s increasing prevalence in rural Vanuatu.

A particular focus in the literature is on an apparently increasing trend for marriages between people of different language backgrounds. As more marriage partners come from further afield than they did traditionally, they are less likely to learn the community’s language and instead raise their children with Bislama (Barbour et al. 2018, p 166; Budd, 2011, p 194; Crowley, 2006a, p 7; Guérin, 2008, pp 52–53; Hess, 2009, p 70; Jauncey, 2011, p 7; Philibert, 1988, p 169; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 104; Vari-Bogiri, 2005, pp 60–61). In one village on Malekula, more than half the students at the primary school apparently learnt the local vernacular as a second language because they came from ‘mixed’ households reliant on Bislama (Shipman, 2008, pp 97–98). In northern Vanuatu, some parents of different language backgrounds teach their children Bislama because they think they would be confused by growing up in a multilingual household (François, 2012, pp 105–106). Migration in this context thus does seem associated with the displacement of Indigenous languages by Bislama, specifically by encouraging use of Bislama as the household language, thus interrupting Indigenous language transmission (Daly and Barbour, 2021, pp 1426–1427).

Reports suggest similar processes take place at a community level, whereby outsiders’ presence at public events prompts the use of Bislama. In church services, regardless of denomination, Bislama is more likely to be used when the audience contains people from outside the community (Crowley, 2000, p 66; Natosansan, 1989, p 79; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 115). Indeed, the association between Bislama and public speechmaking (in politics as well as religion) has become so strong as to persist even when outsiders are no longer present (François, 2012, p 105; see also Barbour, 2009, p 231). Historical examples of community language shift are also implicated in migration. For instance, the presence of a coastal plantation on Malekula drew people from across the island into a mixed language environment in which Bislama displaced the local language (Crowley, 2006a, p 6, 2006b, pp 1–2). Similar processes of community migration have resulted in Bislama gaining dominance in regions of other islands too, as on Pentecost and Malo (Gray, 2012, p 10; Jauncey, 2011, p 5).

Existing work thus strongly emphasises in-migration as a factor driving the shift towards Bislama. Nevertheless, it remains important to consider alternative explanations for this relationship. The urban areas are the places that attract the most migrants (Haberkorn, 1989), so we might expect some of the observed relationship between in-migration and the shift towards Bislama to be explained by other factors related to distance to an urban centre. Similarly, attaining higher levels of education requires travel away from home, making it more likely that those with more education will find marriage partners from further afield, implicating education as a more ultimate cause in this scenario. Also, as I discuss below, it is difficult to disentangle causal directionality in the relationship between in-migration and economic development. We could thus expect some of the relationship between in-migration and the shift towards Bislama to be driven by a common cause related to economic development. These possibilities, however, do not detract from the testimonies of researchers on the ground that in-migration, even in relatively remote communities, causes increased use of Bislama in households and in public.

Formal education

Individuals’ educational attainment is related to their greater use of Bislama and lower use of Indigenous languages in available survey data (VNSO, 2021, p 113). A likely explanation for this is the widespread observation that Bislama is favoured by the education system’s failure to promote Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages (Crowley, 2000, pp 85–86; McCarter and Gavin, 2011, p 5; Regenvanu, 2004; Tamtam, 2004; Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, p 454). This failure is partly legislative. For a long time, Indigenous languages were banned from classrooms to promote students’ uptake of English and/or French, two languages arguably of practical use to only a small section of Ni-Vanuatu (Shipman, 2008; Willans, 2015). Efforts to promote bilingual English–French education to the exclusion of Indigenous languages led Vanuatu’s government, some argue, to “inadvertently promulgate” “colonisation by language” (Daly and Barbour, 2021, p 1426; also Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013a). Moreover, these official prohibitions backfired by promoting Bislama as the de facto classroom language (Siegel, 1996; Willans, 2011).

The school system’s inadvertent promotion of Bislama is also partly practical. From the early 2010s, Vanuatu’s government has been working to implement Indigenous language curricula for the first three years of primary education. The scheme is having an impact, with teaching resources developed for at least 58 Indigenous languages (Early, 2023, pp 174–176). But uptake has been slow due to both the sheer number of Indigenous languages for which teaching resources are needed and concerns from teachers about getting adequate support and training to implement these resources (Barbour et al. 2018; Daly and Barbour, 2021, pp 1422–1423; Lindstrom, 2020, p 156; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 111; Ridge, 2019, pp 31–32). Because teachers often come from other parts of the country, they do not always feel comfortable speaking the local language (Barbour, 2009, p 232; François, 2002, p 101; Love et al. 2019, p 90). Many schools, in any case, serve linguistically mixed communities (Barbour, 2009, p 232; Nako, 2004; Ridge, 2019, p 75). This is especially true for secondary education, which, because of Vanuatu’s dispersed population, frequently requires inter-island travel and thus creates linguistically diverse communities of young people that depend on Bislama (Budd, 2011, pp 194–195; François, 2002, p 8; Hoback, 2024, p 131; Jauncey, 2011, p 7; Tryon, 2006, pp 107–108).

Still, education has not always played this role. Until the mid-20th century, essentially all education was provided by Christian missions whose primary focus was enabling people to read scripture in (some) Indigenous languages (Campbell, 1974, p iv; Siegel, 1996). Missionary education standards were low, but also posed no serious challenge to Indigenous language transmission (Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, p 403). This began to change from the 1950s, when the two colonial governments began to play greater roles in education (Woodward, 2014, p 83). The French administration created a string of boarding schools to challenge the dominance of Protestant missionary schools, while the British increasingly directed and expanded upon the Protestant school system (Miles, 1998, pp 46–51; Van Trease, 1987, pp 108–111). Each administration’s schools prioritised their own language to promote anglophone or francophone influence within the country (Crowley, 2000, pp 74–75). That these changes to the education system in fact promoted Bislama was thus an unintended result (Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, pp 404–405). Following Vanuatu’s independence, despite the anticipation that the colonial education system would be overhauled in favour of Indigenous languages, this has not properly taken place (Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013a; Willans, 2015).

Notwithstanding the likelihood of a causal effect of exposure to formal education on the shift towards Bislama, it remains important to consider alternative pathways between these factors. Provision of education is easier and better in urban compared to rural areas (Cox et al. 2007, p 4; Policy and Planning Unit, 2014), which goes some way to explain why educational attainment is highest in the cities (VNSO, 2021, p 128), although we would also expect more educated people to migrate to urban areas for economic opportunities. It is also difficult to disentangle the directionality of formal education’s relationship with economic development, as I discuss further below. Part of the association between education and the spread of Bislama does therefore seem likely due to these common causes. Nevertheless, overall, recognition of these alternative pathways does not detract from the accounts of researchers and others that describe putative mechanisms by which formal education may itself facilitate a shift towards Bislama.

Communication and transportation technologies

By enabling communication between people who do not live in close geographic proximity to each other, greater access to communication and transportation technologies plausibly incentivises the use of languages that enable cross-community communication, which in Vanuatu’s case is Bislama (Riehl, 2019). While these technologies are more widespread in the urban areas, their rural reach has also grown substantially (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, pp 65–66, p 89). The importance of mobile phones and internet access in Vanuatu, alongside access to means of physical transportation, thus seems important for explaining the greater use of Bislama in rural areas as well as urban areas.

Even before the recent spread of mobile phones and the internet, an association existed between Bislama and communication and transportation technologies. By enhancing connectivity between communities, the introduction of trucks, motorboats, and aeroplanes likely increased the importance of knowledge of Bislama in daily life. Motorcars were present on several islands by the mid-1920s, albeit limited to the European population at this stage (Colonial Office, 1928, p 11), while following the American military’s withdrawal in 1945, jeeps were common on some islands for decades after (Allen, 1964). The first form of mass media in Vanuatu was radio, especially after Radio Vila began broadcasting in 1966 (Bolton, 1999a; MacClancy, 1981, p 71). Bislama quickly came to prevail in as much as 90% of broadcasts (Crowley, 1990, p 17), constituting a “powerful influence” on these generations’ familiarity with and use of Bislama (Sperlich, 1991, pp 32–33). Bislama fluency thus became necessary to engage with national life and keep up with current affairs and political debates (Ridge, 2019, p 28). Meanwhile, the landline telephone network remained limited and patchy even by the time of the millennium (Crowley, 2000, pp 49–50). Mobile phone technology also had a slow start following its 2001 introduction, due to prohibitive costs and patchy coverage, but the establishment of the Digicel network in 2008 proved to be a revolution (Kraemer, 2018). Mobiles “quickly became expensive necessities” (Lindstrom, 2020, p 162) and by the following year, 71% of rural households had mobile access (VNSO, 2009, p 141). Mobile-based internet access has since developed, too. By the time of the 2020 census, 26% of individuals said they had used online services in the previous week, including 20% of those in rural areas (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, pp 65–66).

With this communications revolution has come an increased role for Bislama in public and private life. Mobile texting almost always relies on Bislama (Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013b) and, as Vanuatu has become more online, Bislama has come to dominate these spaces also (e.g., Willans, 2017). This marks a key shift in Bislama’s history: a transition away from its status as an oral language. Bislama’s place as the primary language of telecommunication affords it a new form of prestige, with a perhaps growing perception that Bislama proficiency indexes cosmopolitanism and adeptness to modernity (Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013b, p 174). This is not a uniquely urban development. Introduction of online communication on Ahamb has increased the practical importance of Bislama to daily life because the local Indigenous language has not transitioned into this new space, a development that leads observers to worry for the community’s future ability to transmit the language to younger generations (Rangelov et al. 2019, pp 113–114).

As well as a direct effect on the increasing prevalence of Bislama in daily life, communication and transportation technologies are likely also linked to the shift towards Bislama via indirect, ‘backdoor’ paths. I note above that access to these technologies is influenced by proximity to an urban centre, and so some of the relationship between Bislama and the presence of these technologies will likely be explained by this common cause. It would also appear difficult to disentangle the close relationship between communication and transportation technologies and economic development, discussed further below. Nevertheless, given the testimony of researchers, an independent effect of increasing access to communication and transportation technologies on language shift towards Bislama seems likely.

Economic development

I have already noted that penetration of the forces of economic development (defined after, e.g., Wolf, 2010) is plausibly linked to a shift towards Bislama as well as several of the other factors discussed. It is linked with proximity to urban centres because the major industries and employment opportunities are located in the cities, whereas horticultural self-subsistence is more characteristic of rural areas (Cox et al. 2007). Economic development also has complex, likely bidirectional relationships with rates of in-migration, access to education, and access to communication and transportation technologies. This means we might expect economic development to be both a product and a cause of each of these factors. Economic development brings opportunities that encourage migrants, whose arrival spurs further development (Posso and Clarke, 2016). Economic development also affords greater access to education, with greater access to education providing further economic opportunities (Gounder, 2016; Mullins, 2018). And just as economic development permits greater access to communication and transportation technologies, these technologies in turn facilitate further development (Lindstrom, 2020, pp 161–162). Relationships between economic development and these other variables would partially explain why we find them co-occurring: the cities have the most economic development, the greatest access to education, the greatest in-migration, and the greatest access to communication and transportation technologies, as well as being the places where Bislama is strongest. We therefore have reason to suspect indirect ‘backdoor’ paths connecting economic development with a shift towards Bislama.

But what evidence exists for a direct effect, independent of other factors? Economic development is not confined to cities, but wherever it has become established, it seems Bislama has too. This is true as far back as Bislama’s origins on the Australian plantations and its subsequent characterisation as a ‘plantation language’. For example, one of the earliest examples of Bislama as a first language comes from a plantation on Efate that drew in men from other parts of Vanuatu for work in the 1920s, where they married local women and began living permanently at Saama village, raising their children using Bislama (Crowley, 1990, p 384). We might note that economic development here spurs the growth of Bislama by way of increasing migration. But migration is not always necessary for economic development to promote Bislama. The general usefulness of Bislama in pursuing economic success is expressed in popular attitudes that link a lack of Bislama fluency to being man bus, a term used to denote those not savvy to the opportunities of the modern world (Crowley, 1990, p 15). Indeed, the perception that Bislama is important for success in business and for upward social mobility is identified by some observers as an important reason for its rising success over Indigenous vernaculars (Guérin, 2008, p 53; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 118).

However, some researchers have argued that lack of economic development could encourage a shift towards Bislama. Crowley (1995, p 340) argues that Bislama might be embraced by disadvantaged communities as a strategy to ‘catch up’ with more economically successful ones, while Budd (2011, p 196) argues that, because economically deprived communities are less able to afford education, they are more likely to be served by Bislama-speaking schoolteachers and church leaders from outside the community. It may be plausible that these factors complicate a straightforward relationship between the spread of economic development and Bislama. But it seems doubtful they would override the historic association between Bislama and economic development described above. Given that Crowley’s argument necessitates a link between Bislama and economic success that economically disadvantaged communities can perceive, even if they were to self-consciously adopt Bislama, it would be surprising for them to do so more than the more economically integrated communities that would face the greater day-to-day need for it. Likewise, granting Budd’s point about the difficulties that poorer communities might face in filling community positions that require expensive amounts of formal education, it is doubtful this would override the greater exposure to Bislama the community would receive if more of them could afford access to secondary education. Overall, while acknowledging the potential for these counter-tendencies, the balance of evidence suggests economic development may encourage a shift towards Bislama.

Youth

Another clear trend in the census data is that self-reported ability to speak an Indigenous language is lowest amongst youth, particularly those under thirty (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, pp 64–65). Despite the clarity of this pattern, however, this seems more likely due to an indirect ‘backdoor’ path rather than a direct causal path.

First, youth is strongly connected to two variables that we have already related to the shift towards Bislama: migration and access to education. Migration is understandably biased towards younger adults, especially the 15–29 age group (Muthiah and Seetharam, 1993), and because access to education in Vanuatu has increased over time, younger adults are more educated than older ones (VNSO, 2021, p 128). If we suspect these factors of causing a shift towards Bislama, we should therefore not be surprised that this shift disproportionately affects younger people. For instance, Duhamel (2020b) explains the higher frequency of borrowings from Bislama in the speech of young people through their contact with Bislama in schools and colleges. Nevertheless, ‘backdoor’ causal explanations do not preclude the existence of a direct causal path. For instance, young people’s nonconformist dispositions may incline them to language shift. However, any test of this is complicated by the association of youth with language shift that we would expect as a consequence of language shift itself. Because languages are generally learnt in childhood, if a community shift is ongoing, it will appear first amongst children and young people before adults (Krauss, 2008). Given a mechanistic relationship between youth and language shift should thus exist in any case, it seems redundant to speculate on further mechanisms for which we do not have direct evidence.

My scepticism that young people actively drive the shift towards Bislama contrasts with some moralising attitudes about language shift in Vanuatu (e.g., Vari-Bogiri, 2005, p 62). Concerns about Bislama can sometimes draw on broader fears of young people’s perceived loss of kastom: associated with other aspects of youth subculture like reggae, Bislama, or lanwis blo rod (language of the road), represents to some “a double illegitimacy as being neither traditionally Melanesian nor Western” (Levisen, 2017, p 114). Blame can also sometimes be directed towards parents who are perceived to be making insufficient effort to transmit kastom language knowledge to their children, as articulated by a recent Prime Minister (Oswald, 2021). This kind of reasoning reframes a social issue as a personal one, shifting responsibility from structural factors onto individuals. Ultimately, the personalisation of a complex process makes it easier to comprehend, while the identification of a group at fault, either lazy youths or careless parents, provides a cause célèbre that distracts from difficult discussions about policy and social change.

Arrival of Christian missionaries

Based on the experience of Christian missionisation and the loss of linguistic heritage in other parts of the world (e.g., Epps, 2005), we could expect the arrival of missionaries in the 19th century (Presbyterian, Anglican, and Catholic) to be a factor in weakening Indigenous languages and thus speeding them towards replacement by Bislama. Colonial-era Christian denominations did suppress many aspects of Indigenous culture (Fox, 1958, pp 46–47; Mander, 1954, p 463; Scarr, 1967, pp 236–248). The very idea of kastom (i.e., traditional culture) developed as an antonym of skul, a word which referred to Christian missions and their institutions (Jolly, 1982, pp 339–341; MacClancy, 1983, pp 97–98). This perception persists, for example, in some Malekulan people’s contention that the arrival of missionaries precipitated the loss of traditional ecological knowledge, a concept closely tied to Indigenous languages (McCarter and Gavin, 2014). It is true that some missionaries did denigrate Vanuatu’s linguistic diversity. According to one, “the confused Babel of tongues spoken by the natives” “is a serious obstacle to Mission work” which “will go the way of the language of the Scottish Highlands.” But the same missionary found that the “native languages are not the barbarous jargon” they had expected, seeing “no resemblance between the [savage] people and the language they use” (Rev. Frater in Langridge, 1918, pp 9–10). Another similarly describes the languages as “one of the things that heathen nations have not degenerated in” (Rev. Milne in Don, 1918, p 114). Indeed, most missionaries seem to have believed that evangelism was most effective using Indigenous languages (Campbell, 1974, pp 6–7; Gardner, 2006; Miller, 1978, pp 108–111; Whiteman, 1983, p 34). The missionaries’ enthusiastic embrace of Indigenous language-evangelism was a counterpart to their particularly strong aversion towards Bislama, and their consensus on its uselessness lasted until the 1960s (Crowley, 1990, p 171; Mühlhäusler, 2002). As one Presbyterian missionary explained, “[a]s a vehicle for the expression of theological ideas it [Bislama] left a lot to be desired” (Riddle, 1949, p 77), in agreement with an Anglican who adds “it is a barrier to knowledge of every sort” (Rev. Warren in Whiteman, 1983, p 230).

The importance placed on Indigenous language evangelism led to the Presbyterians and Anglicans being the first groups to develop writing systems for the Indigenous languages, teach literacy, and provide Indigenous language literature in the form of scripture and hymns, and they trained local evangelists to preach amongst their own people (Miller, 1978; Monnier, 1989; Whiteman, 1983; though their success in instilling Indigenous language literacy was far from comprehensive: Lynch, 1979). Moreover, the missions’ Bible-centric curricula and low educational standards put Indigenous languages in little danger (Campbell, 1974; McKenzie, 1972). Opposition to the perceived ‘evils’ of kastom does not directly translate, therefore, into aversion to Indigenous languages (Gardner, 2006). Despite the deleterious effects that missionaries had on various aspects of traditional culture (e.g., Lynch and Spriggs, 1995), a shift towards Bislama was not one of them (Crowley, 2001). Indeed, exposure to missionaries’ efforts to use Indigenous languages may even have helped them survive an era of catastrophic depopulation and political destabilisation.

The growth of evangelising Christian denominations

While available evidence does not indicate that the arrival of Christianity in general has driven a shift towards Bislama, an intriguing possibility is that Bislama’s spread is related to an ongoing change in Vanuatu’s religious landscape. Since the beginning of the 20th century, various denominations other than the ‘established’ churches discussed above have arrived in Vanuatu. Especially since the 1970s, ‘evangelising’ churches have attracted growing numbers of converts, and an explosion in small, often charismatic sects is arguably one of the most significant social transformations in the country since independence (Eriksen, 2022; Zocca, 2006). Intriguingly, researchers have observed that these churches, including the Seventh-day Adventists and various Pentecostal groups, use more Bislama in their religious activities compared to the ‘established’ denominations (Crowley, 2000, pp 65–66; Hyslop, 2001, p 6). Given the social importance of Christian institutions throughout Vanuatu (Cox et al. 2007; Eriksen, 2022), if evangelising denominations do use more Bislama than others, their growth could displace Indigenous languages from a prestigious and materially important arena.

Evangelising denominations’ frequent and harsh criticisms of kastom, as a heathen hangover that must be overcome to attain development and modernity (Eriksen, 2014; Hess, 2009, pp 157–158; Miles, 1998, pp 108–109; Rio, 2010), might be invoked to explain these denominations’ favouring of Bislama. Yet we must be cautious because, as discussed above, ideological opposition to kastom does not necessarily imply opposition to Indigenous languages. Nevertheless, perhaps a more precise case could be made for an affinity between several evangelising denominations’ ideological orientation towards modernity and Bislama, use of which is described as a notable signal of engagement with modernity (Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013b, p 174). However, empirically-informed arguments for such a link, along the lines of Whiteman’s (1983, pp 268–269; also Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo, 1991, pp 268–269) description of the South Sea Evangelical Mission’s fundamentalist outlook being responsible for their use of Solomon Islands Pijin, are lacking for Vanuatu. An ideological explanation must therefore remain somewhat speculative.

Another potential mechanism whereby the growth of evangelising Christian denominations may contribute to the spread of Bislama is more practical, following from their need to recruit converts. Whereas the established churches are largely content to pastor to the communities with which they already have longstanding relationships, what distinguishes these denominations is their prioritisation of evangelism (Austin, 2014, p 116; Miles, 1998, pp 110–115; Zocca, 2006, p 260). Their use of Bislama could therefore follow from their need to communicate with the maximum number of potential converts (e.g., Jarraud-Leblanc, 2013, p 106). One of the first Pentecostal groups to arrive, Assemblies of God, for instance, “quickly” recognised that “using the Bislama language in their services” would help them evangelise (Ellison and Ellison, 2007). SDA missionaries on Mavea did not consider translating materials into the Indigenous language, reportedly because the speech community was too small to justify the effort, and since then all religious services and ceremonies have operated in Bislama, apparently contributing to the endangerment of the local Indigenous language (Guérin, 2008, p 52). François (2012, p 108), meanwhile, explains the evangelising denominations’ greater reliance on Bislama in northern Vanuatu through their reliance on pastors from outside the region. But the argument from practicality is not entirely straightforward either. We have already encountered evidence that congregations of all kinds switch to Bislama when outsiders are present. There are also descriptions of established denominations, particularly the Presbyterians, routinely conducting services in Bislama, for reasons including that they too can prefer to appoint pastors from elsewhere or because Indigenous language materials are not available (Barbour, 2009, pp 231–232; Jauncey, 2011, pp 7–8; Paviour-Smith, 2008, pp 5–7; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 105; Shipman, 2008, p 73). Indeed, from the 1960s onwards, the established denominations collaborated to produce a Bislama-language Bible (Miles, 1998, p 142). Counter-examples like these make a significant impact of the growth of evangelising denominations on the shift towards Bislama less plausible.

Furthermore, the spread of evangelising churches is itself likely to be an outcome of many of the factors noted above. Evangelising denominations’ growth in the Pacific and elsewhere is clearly linked to urbanisation and exposure to global economic and social forces (Ernst, 2006, pp 713–716). In Vanuatu, small denominations tend to begin work in Port Vila or Luganville, before producing ‘daughter’ congregations that extend their reach to rural islands (Eriksen, 2012, p 111; Taylor, 2015, p 39). These denominations are also enthusiastic adopters of new communication technologies, including radio and online social media (Austin, 2014; Eriksen, 2014, p 134), and they benefit from high levels of migration (Eriksen, 2014, pp 148–149). We should therefore expect an association between the presence of evangelising churches and a greater shift towards Bislama, even if only because both have common causes.

Language attitudes

Attitudes towards language, sometimes called ‘language ideology’, have understandably attracted much interest from researchers. Thus far, I have noted language attitudes somewhat implicitly in discussing other factors. For example, when discussing associations between Bislama, communications technologies, and economic development, I noted evidence that Bislama fluency is perceived as important for gaining economic opportunities and signals engagement with modernity (Barbour, 2009; Crowley, 1990, p 15; Guérin, 2008; Rangelov et al. 2019; Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013b). However, positive perceptions of Bislama’s usefulness are balanced to some extent by negative perceptions of its merely being a ‘broken’ and lower-status form of English (Schneider, 2018; Willans, 2017) or insufficiently expressive compared to the richness of kastom languages (Barbour et al., 2018, pp 170–171). Attitudes like these would seem implicated in the concerns, noted above, that many people hold about the prospect of Bislama replacing Indigenous languages (Love et al. 2019; Shipman, 2008, p 97). At the same time, ideas about kastom languages’ richness can slide into pessimistic perceptions that contemporary varieties are already corrupt vestiges of a more perfect linguistic past, an attitude that some researchers argue may expedite language shift (Meyerhoff, 2014, p 127; Rangelov et al. 2019, p 118; Ridge, 2019, p 80; Schneider, 2018; Takau, 2016, p 20). This mixed picture makes it unclear what the prevailing language attitudes are (Duhamel, 2020a, pp 164–165; Shipman, 2008, pp 101–107; Vari-Bogiri, 2005, pp 62–63; Willans, 2017). Further data are needed to determine the content of the prevailing language attitudes, before ascribing a causal role to them in driving larger trends like the shift towards Bislama.

Speaker population size

Roughly 72% of Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages are spoken by fewer than 1 000 individuals, and just one is spoken by more than 10,000 (François et al. 2015, p 8). Based on these numbers alone, many language endangerment frameworks would classify nearly all of Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages as endangered, because “a small speech community is always at risk” (UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages, 2003:2; Krauss, 1992; Lee and Van Way, 2016). The statistical relationship between speaker numbers and extinction risk is borne out by worldwide data (Amano et al. 2014; Bromham et al. 2022). However, several researchers working in Vanuatu are sceptical that small speaker sizes constitute an important causal factor in language endangerment (Early, 2023; Willans and Jukes, 2017).

There are two parts to this argument: that a small community size does not inhibit intergenerational language transmission, and that size is itself an outcome of language endangerment. Vanuatu demonstrates the first point well, with a large number of small language communities that have, so far at least, robustly transmitted Indigenous languages down to the present. Moreover, this situation is likely representative of the precolonial pattern, with “language communities … typically … the size of one or two villages with no more than a few hundred members” (François et al. 2015, p 8). If Vanuatu’s language communities have always generally been small, and these have proven resilient, it reduces the worry that this puts them at imminent risk of extinction. For example, of the two Malekulan villages that speak Neverver, the larger is at more imminent danger from Bislama compared to the smaller, more isolated village (Barbour, 2009). Other factors, these researchers argue, are thus more important for explaining endangerment.

Nevertheless, it remains plausible that, other things being equal, smaller language communities are more at risk than larger ones, like how smaller gene pools are affected by genetic drift more than larger ones (Masel, 2011). Small community sizes could enhance endangerment risks that are caused by other factors (e.g., François, 2012, pp 95–96). For example, in-migration would have a relatively larger effect on smaller communities than on larger communities. Here, the second part of the argument comes in, however: that small language community size is itself an outcome of endangerment (Ravindranath and Cohn, 2014). At its extreme, language extinction requires a fall in speaker numbers. Vanuatu has several languages that have just a handful of speakers each, and all of these examples are results of disruptions to intergenerational transmission (François et al. 2015, pp 7–8). It is therefore difficult to discern the effect of language community size on endangerment in a way that precludes reverse causation: the effect of endangerment on language community size. Disentangling this would seemingly require a natural experiment in which language endangerment is initiated by an exogenous variable that similarly affects a range of language communities of different sizes. Until then, the magnitude of the role that speaker community size plays in the shift towards Bislama remains hypothetical.

Historical destabilisation

An intriguing possibility is that of long-term implications from historical population displacement and collapse on the contemporary shift towards Bislama. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Vanuatu’s islands underwent sociopolitical upheaval and catastrophic population decline. This occurred due to diseases introduced by Europeans (Spriggs, 1997, pp 255–263), migration due to the establishment of coastal plantations and Christian villages (Bonnemaison, 1994, p 44; de Lannoy, 2004; Eriksen, 2008, pp 36–38), overseas labour recruitment (Scarr, 1967, p 188), wars between different groups (Bonnemaison, 1994, pp 166–168; Crowley, 2006c), and migration due to geological and climate-related disasters (Tonkinson, 1985; Yoann and Vincent, 2020). Existing work indicates these historical perturbations’ main linguistic impact was the loss of dialectal variation, with relatively few languages themselves becoming extinct (Crowley, 2000, p 57; François et al. 2015, p 12; Gray, 2012, p 9). Language diversity was thus reduced by the consolidation of Indigenous languages, rather than any shift towards Bislama, English, or French.

But would areas that suffered the greatest historical destabilisation or collapse be those most susceptible to displacement by Bislama today? This seems a reasonable hypothesis to test. For example, the widespread use of Bislama in southeast Malo is likely related to the contraction of the Indigenous population over the 19th and early 20th centuries due to introduced diseases, alongside 20th-century influxes of people from Pentecost, fleeing local warfare, and from Ambrym, fleeing volcanic disaster (Jauncey, 2011, p 5). However, it is also plausible that in some cases, greater language attrition in the past decreases the chances of a shift towards Bislama in the present. Crowley (2006a) indicates that islands with just one Indigenous language might have an advantage in maintaining vitality compared to islands with more complex language situations. This aligns with the ‘extinction filter’ concept from conservation science, which states that extinction events consolidate the best-surviving species (or languages) and that these survivors are more resilient to subsequent threats, which has found some support in previous analyses of language endangerment (Amano et al. 2014). Further data are thus needed to adjudicate on whether historical destabilisation contributes to contemporary language shift and whether it does so by aiding or hindering Bislama’s spread.

Why Bislama specifically?

One could argue it is not Bislama per se that poses the threat to Indigenous languages, but rather the social factors outlined above. But it is important to recognise that it is specifically Bislama that these factors favour, rather than English, French, or another language. This follows from Bislama’s status as Vanuatu’s lingua franca, which in turn follows from Bislama’s role in Vanuatu’s history. The inability of Britain and France to vanquish the other precluded either English or French from gaining precedence (Tryon and Charpentier, 2004, p 403). Following independence, Bislama helped unite the country by evading anglophone-francophone differences and by distinguishing independent Vanuatu from its colonial past. Bislama thus embodies Vanuatu’s complex experience of colonisation, both as a product of it and as an Indigenous creation in response to it, a balance that is likely useful in navigating the post-colonial context (Lavender Forsyth and Atkinson, 2024).

Bislama also possesses features that have likely favoured its becoming Vanuatu’s lingua franca. Heated academic debate continues over whether languages like Bislama, created in situations where a community learns a language that is not their first language, have features that prioritise learnability over complexity (Jourdan, 2021). In any case, Bislama certainly has features that make it specifically easier to learn for speakers of Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages, including sound types, grammatical structures, words, and expressions that match those common across these Oceanic languages (Crowley, 1990). A combination of inherent and contextual factors thus seems responsible for why it is Bislama that has come to pose a threat to Vanuatu’s Indigenous languages.

Predictions for the future, or what can be done?

The available evidence indicates that the spread of Bislama is not merely adding to Vanuatu’s linguistic diversity. As reflected in the census data, there has been increasing use of Bislama in the key domain of household use, and a significant proportion of people—youths especially—now speak Bislama as their first language. It will be significant to see how these figures change in the next census. Vanuatu’s outstanding linguistic diversity is not currently in a state of collapse, but this review indicates that processes are underway that do pose a real danger.

To understand the process of language shift, I have used linguistic and ethnographic reports to identify the most likely contributing factors and work through their inter-relationships. Rather than singling out a key variable, my analysis highlights an interconnected suite of factors that are familiar to studies of language endangerment across the world (Amano et al. 2014; Bromham et al. 2022). These factors, including in-migration, formal education, communication and transportation technologies, and economic development, are all likely to be causally connected and, perhaps, mutually reinforcing. Proximity to an urban area is another significant factor, though it is crucial to note that Bislama poses a threat in rural areas too. If factors like the rate of urban growth continue at current trends (Hakkert and Pontifex, 2022, p 4, pp 14–15), they are likely to continue driving a shift from Indigenous languages towards Bislama in the future. The next stage for future work will be to operationalise the framework outlined here for statistical analysis, with quantitative tests of the magnitude of the different factors’ effects on the shift towards Bislama that are informed by this ‘bottom-up’ qualitative description of the ongoing process of language shift. I also advocate for more concerted work on the content of language attitudes, building on initial studies conducted in Vanuatu (Ridge, 2019) and drawing on wider Melanesian scholarship (Kulick, 1992).

The convergence of national statistics with descriptions of plausible causal mechanisms from ‘on-the-ground’ research indicates that the spread of Bislama does pose a risk to Vanuatu’s language diversity. Given that the erosion of this diversity is something many people in Vanuatu want to avoid (Barbour et al., 2018, p 170; Daly and Barbour, 2021, p 1423; Love et al. 2019; Naupa, 2011, p 128; Regenvanu, 2004; Shipman, 2008, pp 95–97; Takau, 2016, pp 21–22), and the government has promised to promote and protect linguistic diversity as a part of its official development objectives (Department of Strategic Policy Planning and Aid Co-ordination, 2016), what can this review of the available evidence teach us that might be used to help defend Vanuatu’s linguistic diversity?

The picture I present above, based on the current evidence available, is not totally deterministic, and the factors I discuss are potentially amenable to intervention. In education, for instance, the government is already beginning to institute Indigenous languages in the first three years of primary school (Vanuatu National Language Policy, 2015). This scheme has the double benefit of encouraging the use of Indigenous languages in a prestige domain and giving children a more accessible learning experience in their first language (Daly and Barbour, 2021; Willans, 2017). While some problems of implementation have arisen, reports indicate that the project is having a widespread positive impact (Early, 2023). Another potential government intervention would be to reduce the number of public sector employees placed in communities where they do not speak the language, especially teachers, by making local language knowledge a factor in deciding job placementsFootnote 1. Nongovernmental interventions could include support for community initiatives to teach local languages to migrants. The village of Makatu, for instance, is so small that in-marriage is necessary to maintain the population, but strong norms requiring incoming partners to speak the local language mean the language is spoken by all (Walworth et al. 2021; see also Hoback, 2024, p 145). Some communities have also begun to use Indigenous languages in online spaces, though this tends to be small-scale (François, 2018, p 284; Krajinović et al. 2022; Vandeputte-Tavo, 2013b), and this is also something that could be encouraged more widely. While it remains unknown whether such interventions could avert language shift towards Bislama, and clear constraints limit what the government and other institutions can do (see Vari‐Bogiri, 2009, pp 170–171), targeting interventions based on a mechanistic understanding of the process of language shift in Vanuatu could help maximise impacts relative to costs.

By carving out areas of use for Indigenous languages, initiatives like these, alongside others including kastom schools and church-led language revitalisation campaigns (Love et al. 2019), should aim to engender a stable form of multilingualism and thus prevent the replacement of Indigenous languages by Bislama. As per experiences in other parts of the world, maintenance of demarcated venues in which Indigenous language knowledge is recognised as valuable or advantageous will likely be central to safeguarding these languages’ vitality (Lewis and Simons, 2016; Nettle and Romaine, 2002). The provisional picture I have outlined here does converge against Indigenous languages and in favour of Bislama. But Vanuatu has the advantage that, today, its linguistic diversity does remain vital. Challenges may lie ahead, but a causal understanding of the processes favouring an ongoing shift from Indigenous languages to Bislama points the way forward for the continued fight to see Indigenous languages flourish in Vanuatu.

Data availability

The census data shared by Vanuatu’s National Bureau of Statistics with the author unfortunately cannot be made publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions. For more details about the data, please contact the author.

Notes

I attribute this idea to Andrew Gray, in a personal communication of 2 October 2024.

References

Allen MR (1964) The Nduindui: a study in the social structure of a new Hebridean community. PhD thesis, Australian National University

Amano T, Sandel B, Eager H, Bulteau E, Svenning J-C, Dalsgaard B, Rahbek C, Davies RG, Sutherland WJ (2014) Global distribution and drivers of language extinction risk. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci 281:20141574. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1574

Austin L (2014) Faith-based community radio and development in the South Pacific Islands. Media Int Aust 150(1):114–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1415000122

Barbour J (2009) Neverver: a study of language vitality and community initiatives. In: Florey M (ed) Endangered languages of Austronesia. Oxford University Press, pp 225–244

Barbour J, Wessels K, McCarter J (2018) Language contexts: Malua (Malekula Island, Vanuatu). Language Doc Descr 15:Article 0

Bolton L (1999a) Radio and the redefinition of Kastom in Vanuatu. Contemp Pac 11(2):335

Bolton L (1999b) Women, place and practice in Vanuatu: a view from Ambae. Oceania 70(1):43–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4461.1999.tb02988.x

Bonnemaison J (1994) The tree and the canoe: history and ethnogeography of Tanna. University of Hawaii Press

Brandl E, Colleran H (2024) Does bride price harm women? Using ethnography to think about causality. Evol Hum Sci 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2024.21

Bromham L, Dinnage R, Skirgård H, Ritchie A, Cardillo M, Meakins F, Greenhill S, Hua X (2022) Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity. Nat Ecol Evol 6(2):163–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01604-y

Budd (2011) On borrowed time? The increase of Bislama loanwords in Bierebo. Language Doc Descr 9:169–198. https://doi.org/10.25894/LDD208

Bulbulia J, Schjoedt U, Shaver JH, Sosis R, Wildman WJ (2021) Causal inference in regression: advice to authors. Relig Brain Behav 11(4):353–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2021.2001259

Campbell MH (1974) A century of Presbyterian mission education in the New Hebrides: Presbyterian mission educational enterprises and their relevance to the needs of a changing Melanesian society, 1848–1948. Masters thesis, University of Melbourne

Colonial Office (1928) New Hebrides. Report for 1927. His Majesty’s Stationary Office

Connell J (2020) Islands, languages, and development: a commentary on dominant languages. Prof Geogr 72(4):644–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2020.1744171

Connell J, Lea J (1994) Cities of parts, cities apart? Changing places in modern Melanesia. Contemp Pac 6(2):267–309. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23707238

Cox M, Alatoa H, Kenni L, Naupa AU, Rawlings GE, Soni N, Vatu C (2007) The unfinished state: drivers of change in Vanuatu. Australian Agency for International Development

Crowley T (1990) Beach-la-Mar to Bislama: the emergence of a national language in Vanuatu. Clarendon Press

Crowley T (1995) Melanesian languages: do they have a future. Ocean Linguist 34(2):327. https://doi.org/10.2307/3623047

Crowley T (1996) Yumi toktok Bislama mo yumi tokbaot Bislama: teaching Bislama in Bislama. In: Mugler F, Lynch J (eds) Pacific languages in education. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, pp 258–272

Crowley T (1997) What happened to Erromango’s languages? J Polyn Soc 106(1):33–63

Crowley T (2000) The language situation in Vanuatu. Curr Issues Lang Plan 1(1):47–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664200008668005

Crowley T (2001) The indigenous linguistic response to missionary authority in the Pacific. Aust J Linguist 21(2):239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268600120080587

Crowley T (2004) Borrowing into Pacific languages: language enrichment or language threat? In: Tent J, Geraghty PA (eds) Borrowing: a Pacific perspective. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, pp 41–53

Crowley T (2006a) Naman: a vanishing language of Malakula (Vanuatu) (Lynch J (ed)). Pacific Linguistics

Crowley T (2006b) Nese: a diminishing speech variety of Northwest Malakula (Vanuatu) (Lynch J (ed)). Pacific linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University

Crowley T (2006c) Tape: a declining language of Malakula (Vanuatu) (Lynch J (ed)). Pacific Linguistics

Daly N, Barbour J (2021) ‘Because, they are from here. It is their identity, and it is important’: teachers’ understanding of the role of translation in vernacular language maintenance in Malekula, Vanuatu. Int J Biling Educ Biling 24(9):1414–1430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1604625

de Lannoy J (2004) Through the Vale of Darkness: history in South Malakula, Vanuatu. University of Oxford

Department of Strategic Policy Planning and Aid Co-ordination (2016) Vanuatu 2030: the people’s plan. https://policy.asiapacificenergy.org/sites/default/files/Vanuatu%20Sustainable%20Dev.%20Plan%202030-EN_0.PDF

Dixon RMW (1991) The endangered languages of Australia, Indonesia, and Oceania. In: Robins RH, Uhlenbeck EM (eds) Endangered Languages. Berg, pp 229–255

Don A (1918) Light in dark isles: a jubilee record and study of the New Hebrides mission of the Presbyterian Church of New Zealand. Foreign Missions Committee

Duhamel M-F (2020a) Borrowing from Bislama into Raga, Vanuatu: borrowing frequency, adaptation strategies and semantic considerations. Asia-Pac Lang Var 6(2):160–195. https://doi.org/10.1075/aplv.19015.duh

Duhamel M-F (2020b) Variation in Raga—a quantitative and qualitative study of the language of North Pentecost, Vanuatu. PhD Thesis, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University

Early R (1999) Double trouble, and three is a crowd: languages in education and official languages in Vanuatu. J Multiling Multicult Dev 20(1):13–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434639908666367

Early R (2023) Social dynamics, public policy and language endangerment in Melanesia: an enduring enigma. In: Brown P, Gaertner-Mazouni N (eds) Small Islands, big issues: Pacific perspectives on the ecosystem of knowledge. Peter Lang Verlag, pp 165–185

Ellison JG, Ellison L (2007) About us. Vision for Vanuatu: the mission work of J. Gary and Lori Ellison. https://visionforvanuatu.com/about/

Epps (2005) Language endangerment in Amazonia: the role of missionaries. In: Wohlgemuth J, Dirksmeyer T (eds) Bedrohte Vielfalt: Aspekte des Sprach(en)tods = Aspects of language death. Weißensee Verlag, pp 311–328

Eriksen A (2008) Gender, Christianity and change in Vanuatu: an analysis of social movements in North Ambrym. Ashgate Publishing

Eriksen A (2012) The pastor and the prophetess: an analysis of gender and Christianity in Vanuatu. J R Anthropol Inst 18(1):103–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2011.01733.x

Eriksen A (2014) A cursed past and a prosperous future in Vanuatu: a comparison of different conceptions of self and healing. In: Rollason W (ed) Pacific futures: projects, politics and interests. Berghahn Books, pp 133–151

Eriksen A (2022) Christian politics in Vanuatu: lay priests and new state forms. In: Tomlinson M, McDougall D (eds) Christian politics in Oceania. Berghahn Books, pp 103–121

Ernst M (2006) Part III: analysis. In: Ernst M (ed) Globalization and the re-shaping of Christianity in the Pacific Islands. Pacific Theological College, pp 686–755

Fox CE (1958) Lord of the Southern Isles: Being the Story of the Anglican Mission in Melanesia 1849–1949. A. R. Mowbray & Co

François A (2002) Araki: a disappearing language of Vanuatu. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University

François A (2012) The dynamics of linguistic diversity: egalitarian multilingualism and power imbalance among northern Vanuatu languages. Int J Sociol Lang 214:85–110. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2012-0022

François A (2018) In search of island treasures: language documentation in the Pacific. In: McDonnell BJ, Berez-Kroeker AL, Holton G (eds) Reflections on language documentation: 20 years after Himmelmann 1998. University of Hawai’i Press, pp 276–294

François A, Franjieh M, Lacrampe S, Schnell S (2015) The exceptional linguistic density of Vanuatu: introduction to the volume. In: François A, Franjieh M, Lacrampe S, Schnell S (eds) The languages of Vanuatu: unity and diversity. Asia-Pacific Linguistics, pp 1–21

Gardner HB (2006) ‘New heaven and new earth’: translation and conversion on Aneityum. J Pac Hist 41(3):293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223340600984778

Gounder R (2016) Effects of income earnings and remittances on education: some empirical results. Bus Manag Rev 7(5):423–429

Gray A (2012) The languages of Pentecost Island. Manples (BFOV) Publishing

Guérin V (2008) Writing an endangered language. Lang Doc 2(1):47–67

Haberkorn G (1989) Port Vila, transit station or final stop? Recent developments in Ni-Vanuatu population mobility. ANU Press

Hakkert R, Pontifex S (2022) Vanuatu 2020 National Population and Housing Census: Analytical Report, vol 2. Vanuatu Bureau of Statistics and the Pacific Community

Hess SC (2009) Person and place: Ideas, ideals and the practice of sociality on Vanua Lava, Vanuatu. Berghahn Books

Hoback B (2024) A sociolinguistic study of language documentation: Denggan (Banam Bay, Malekula, Vanuatu). PhD thesis, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington

Hyslop C (2001) The Lolovoli dialect of the north-east Ambae language, Vanuatu. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University

Jarraud-Leblanc C (2013) The evolution of Written Bislama. PhD thesis, University of Auckland

Jauncey DG (2011) Tamambo: the language of West Malo, Vanuatu. ANU Pacific Linguistics Press

Jolly M (1982) Birds and banyans of South Pentecost: Kastom in anti-colonial struggle. Mankind 13(4):338–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.1982.tb00999.x

Jourdan C (2021) Pidgins and Creoles: debates and issues Annu Rev Anthropol 50(2021):363–378. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-121319-071304

Keesing RM (1988) Melanesian pidgin and the Oceanic substrate. Stanford University Press

Kraemer D (2018) ‘Working the mobile’: giving and spending phone credit in Port Vila, Vanuatu. In: Foster RJ, Horst HA (eds) The moral economy of mobile phones: Pacific Islands perspectives. Australian National University Press, pp 93–106

Krajinović A, Billington R, Emil L, Kaltap̃au G, Thieberger N (2022) Community-Led Documentation of Nafsan (Erakor, Vanuatu). In: Vetulani Z, Kubis M, Paroubek P (eds) Human language technology. Challenges for computer science and linguistics, vol. 13212. Springer International Publishing, pp 112–128

Krauss M (1992) The world’s languages in crisis. Language 68(1):4–10. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1992.0052

Krauss M (2008) Classification and terminology for degrees of language endangerment. In: Brenzinger M (ed) Language diversity endangered. De Gruyter Mouton, pp 1–8

Kulick D (1992) Language shift and cultural reproduction: socialization, self, and syncretism in a Papua New Guinean Village. Cambridge University Press

Langridge AK (ed) (1918) Quarterly jottings from the New Hebrides South Sea Islands, No. 101, July. The John G. Paton Mission Fund

Lavender Forsyth GA, Atkinson QD (2024) A brief history of political instability in Vanuatu. Anthropol Forum 34(3):253–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2024.2346190

Lee NH, Van Way J (2016) Assessing levels of endangerment in the Catalogue of Endangered Languages (ELCat) using the Language Endangerment Index (LEI). Lang Soc 45(2):271–292. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404515000962

Levisen C (2017) The social and sonic semantics of reggae: language ideology and emergent socialities in postcolonial Vanuatu. Lang Commun 52:102–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2016.08.009

Lewis MP, Simons GF (2010) Assessing endangerment: expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Rev Roum Linguist 55(2):103–120

Lewis MP, Simons GF (2016) Sustaining language use: perspectives on community-based language development. SIL International

Lindstrom L (2007) Bislama into Kwamera: code-mixing and language change on Tanna (Vanuatu). Lang Doc 1(2):216–239

Lindstrom L (2018) Surprising times on Tanna, Vanuatu. In: Connell J, Lee H (eds) Change and continuity in the Pacific: revisiting the region. Routledge, pp 55–68

Lindstrom L (2020) Tanna Times: islanders in the world. University of Hawaii Press

Love MW, Brown MA, Kenneth S, Ling G, Tor R, Bule M, Ronalea G, Vagaha S, Kami K, Luki D (2019) What’s in a name? case-studies of applied language maintenance and revitalisation from Vanuatu. Hist Environ 31(3):86–97. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.822720231095354

Lynch J (1979) Church, state, and language in Melanesia: an inaugural lecture. University of Papua New Guinea

Lynch J (1996) The banned national language: Bislama and formal education in Vanuatu. In: Mugler F, Lynch J (eds) Pacific languages in education. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, pp 245–257

Lynch J, Spriggs M (1995) Anejom̃ numerals: the (mis)adventures of a counting system. Te Reo 38:37–52

MacClancy J (1981) To kill a bird with two stones: a short history of Vanuatu. Vanuatu Cultural Centre Publishing

MacClancy J (1983) Vanuatu and Kastom: a study of cultural symbols in the inception of a nation state in the South Pacific. PhD thesis. Oxford University

Mander LA (1954) Some dependent peoples of the South Pacific. Brill

Masel J (2011) Genetic drift. Curr Biol 21(20):R837–R838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.007

McCarter J, Gavin MC (2011) Perceptions of the value of traditional ecological knowledge to formal school curricula: opportunities and challenges from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 7(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-7-38

McCarter J, Gavin MC (2014) Local perceptions of changes in traditional ecological knowledge: a case study from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. AMBIO 43(3):288–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-013-0431-5

McElreath R (2020) Statistical rethinking: a Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan, 2nd edn. Taylor and Francis, CRC Press

McKenzie DJN (1972) The Melanesian Mission in the New Hebrides since 1945. Master's thesis, University of Auckland

Meyerhoff M (2014) Borrowing in apparent time: with some comments on attitudes and universals. Univ PA Work Pap Linguist 20(2), Article 14

Miles WFS (1998) Bridging mental boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: identity and development in Vanuatu. University of Hawai’i Press

Miller JG (1978) Live, a history of church planting in the New Hebrides to 1880: Book one. Committees on Christian Education and Overseas Missions, General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of Australia

Monnier (1989) One hundred years of mission: the Catholic Church in New Hebrides-Vanuatu, 1887–1987. Mission Catholique

Mühlhäusler (1987) The politics of small languages in Australia and the Pacific. Lang Commun 7(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5309(87)90010-3

Mühlhäusler (2002) Pidgin English and the Melanesian Mission. J Pidgin Creole Lang 17(2):237–263. https://doi.org/10.1075/jpcl.17.2.04muh

Mullins K (2018) Vanuatu barriers to education study. Ministry of Education and Training

Murray JC (2018) Ninde: a grammar sketch and topics in nominal morphology. Master's thesis, University of Waikato

Muthiah AC, Seetharam KS (1993) Demographic and migration analysis of the 1989 census. Vanuatu Statistics Office

Nako A (2004) Vernacular language policy in Vanuatu. In: Sanga K, Niroa J, Matai K, Crowl L (eds) Re-thinking Vanuatu education together. Vanuatu Ministry of Education; Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, pp 40–43

Natosansan M (1989) The Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu: mission to Church: an independent or dependent Church? 1848–1980. Bachelor’s thesis, Pacific Theological College

Naupa AU (2004) Negotiating land tenure: cultural rootedness in Mele, Vanuatu. Master's thesis, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Naupa AU (ed) (2011) Nompi en Ovoteme Erromango = Kastom mo Kalja Blong Erromango = Kastom and culture of Erromango = La Coutume et Culture d’Erromango. Erromango Cultural Association

Nettle D, Romaine S (2002) Vanishing voices: the extinction of the world’s languages. Oxford University Press