Abstract

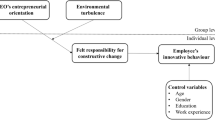

Environmental innovation is an important way for firms to actively fulfill their social responsibilities, and it is also a popular choice for firms to move towards a green path. Based on upper-echelons theory, we examine the relationship between CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation from the perspective of overt leadership traits. Selecting 381 heavily polluting firms in China from 2017 to 2022 as the research sample, multiple regression analysis was used to examine the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on environmental innovation, as well as the mediating effect of face awareness and the moderating effect of firm visibility. The results showed that CEO facial attractiveness promoted firms’ environmental innovation, and face awareness played a mediating role. Firm visibility negatively moderated the relationship between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness. The study reveals the positive impact of a CEO’s positive image in promoting the process of corporate environmental innovation, especially in state-owned firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of globalization, phenomena such as climate change and resource depletion are becoming increasingly serious, raising significant public concern about environmental issues. Industrial firms are the main contributors to environmental pollution and, therefore, must take responsibility for protecting the environment (Fang and Li, 2024; Luo et al. 2023). Firms need to facilitate environmental innovation to promote green development. However, engaging in environmental innovation poses challenges for firms regarding natural supply and the time-consuming and uncertain nature of the environmental innovation process (Sun et al. 2024). Previous research on firms’ environmental innovation has mainly focused on external factors such as environmental regulations, public demand for green practices, and competitor pressure (Chen et al. 2024; Liao and Liu, 2022; Tatoglu et al. 2020; Teeter and Sandberg, 2017), plus internal factors focused on the values and resources of the executive team (Cainelli et al. 2015; Przychodzen and Przychodzen, 2015). There are also some studies that specifically target firms’ chief executive officers (CEOs), taking into account their personal traits and conduct (Li et al. 2024; Ortiz‐de‐Mandojana et al. 2019).

Undoubtedly, firms’ CEOs frequently receive attention from various sectors of society, with a focus on their personal characteristics and the impact they have on the outside world (Lu et al. 2022). In the current social context, the role that CEOs play in environmental innovation is crucial (Al-Shaer et al. 2023). For example, previous studies have validated the impact of CEO traits on firms’ environmental innovation, including CEOs’ religious beliefs (Liao et al. 2019), power (Gull et al. 2023), marketing experience (Huang et al. 2023), and overseas experience (Wang et al. 2022), but there are still some gaps. First, previous studies have overlooked the more observable personal characteristics of CEOs, such as facial attractiveness. According to the upper-echelons theory, the personal characteristics of corporate executives have a significant impact on a firms’ decision-making and operations (Hambrick and Mason, 1984).

Facial attractiveness is the most innate characteristic of executives. Numerous studies have shown that attractive individuals tend to receive more positive evaluations compared to unattractive individuals (Eagly et al. 1991; Langlois et al. 2000). CEOs with high facial attractiveness receive more positive reviews from the public and preferential treatment in all aspects (Hamermesh and Abrevaya, 2013). This may encourage CEOs to take proactive action to uphold their personal image and organizational reputation—specifically, by leading the way in guiding their firms to assume greater social responsibility (Borghesi et al. 2014). Furthermore, external beauty is often associated with moral beauty, so beautiful people are seen as more likely to fulfill their social responsibilities (Wang et al. 2015). Firms’ environmental innovation saves resources, reduces environmental pollution, and demonstrates corporate social responsibility, which strengthens public trust (Mrkajic et al. 2019; Yuan and Cao, 2022). Therefore, CEOs with higher facial attractiveness are more likely to promote firms’ environmental innovation.

If a CEO has a high level of facial attractiveness, they often have a high degree of satisfaction with their personal image, and, therefore, are eager to showcase this advantage to the outside world in order to obtain the benefits of a good reputation, excellent image, and the trust of others (Chen et al. 2014; Dion et al. 1972; Ridgway and Clayton, 2016). This is also known as face-saving consciousness (Goffman, 1955). When CEOs have a high level of facial attractiveness, they are more likely to gain a good impression from the outside world. From the perspective of impression management theory, in order to maintain this initial impression and maintain face, CEOs are often more likely to take actions to consolidate their reputation image, such as leading the firm in environmental innovation (Zhang et al. 2024). Because ethical and public welfare behaviors can enhance the images of CEOs, behaviors such as environmental innovation have pro-social characteristics (Galaskiewicz and Burt, 1991; Godfrey, 2005; Seifert et al. 2003; Suganthi, 2019). However, previous research on the relationship between CEO facial attractiveness, face awareness, and environmental innovation is scarce. Stakeholders’ understanding of a firm often depends on its visibility (Bushee and Miller, 2012). Existing research mainly focuses on the impact of firm visibility on social responsibility, while neglecting the important role of the CEO, especially a visually attractive CEO. So, under the context of high visibility, the effect of CEOs with a beauty premium on face awareness is a topic worth paying attention to.

In this study, we explore how CEO facial attractiveness influences their firm’s environmental innovation. We will consider face awareness as a mediating variable factor and firm visibility as a moderating variable. This study makes the following contributions to the literature. First, it enriches the research on the driving factors of firms’ environmental innovation. Starting with the unique characteristic of the CEO, it elaborates on the impact of face attractiveness on environmental innovation, which adds to the upper-echelons theory by exploring the influence of CEO facial attractiveness on business operations. Second, we examine the mediating role of face awareness and how it influences the relationship between facial attractiveness and environmental innovation, especially the effect of CEO facial attractiveness on face awareness. Third, firm visibility as the moderating variable enhances the understanding of the relationship between facial attractiveness and face awareness, enriching the literature on facial attractiveness.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Face attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation

Facial attractiveness refers to the degree to which the appearance of a face brings pleasure to others (Sigall and Landy, 1973). As the most direct external characteristic of an individual, the appearance of the face is often used as the basis for judging others (Todorov et al. 2005). For example, a person’s levels of empathy, intelligence, and personal prestige can be expressed in their facial appearance (Zebrowitz et al. 2002). Previous studies have shown that facial attractiveness carries an implicit advantage in the job market and can enhance employees’ confidence and performance (Scholz and Sicinski, 2015; Halford and Hsu, 2020). Furthermore, the impact of facial attractiveness applies not only to ordinary employees but also to corporate executives. For example, executives with an outstandingly good appearance may have an advantage in terms of total compensation compared to those with an average appearance (Ahmed et al. 2023), and the salaries of the CEO and top executives of a firm may also vary based on their appearance. Typically, CEOs with high facial attractiveness receive higher salaries (Li et al. 2021).

Will CEOs with high facial attractiveness not only have an impact on individuals, but also on the firm? According to the upper-echelons theory, as senior managers in a firm, their personal traits can influence their own behavior and decision-making, and further shape the firm’s strategic choices and specific actions (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). Among the various dimensions of individual characteristics, external features are usually easier to observe and quantify than internal features, which prompts existing research to use CEO demographic background characteristics as a starting point to examine their impact on firm decision-making and performance (Elsheikh et al. 2025), and CEO facial attractiveness belongs to this category of background features (Guo et al. 2022). For example, in the context of upper-echelons theory, Mills and Hogan’s (2020) study has confirmed that the attractiveness of a CEO’s face directly affects their financial decisions. In addition, the attractiveness of the CEO’s face can also affect their negotiation and merger and acquisition behavior, thereby affecting the firm’s profits and performance, especially for publicly traded firms (Rosenblat, 2008). A CEO with an extraordinary appearance can attract more financing (Halford and Hsu, 2020; Rule and Ambady, 2008).

It is worth noting that in addition to objective firm performance, the CEO’s appearance can also have a significant impact on a firm’s pro-social behavior. Studies have found that the appearance of a CEO is closely related to a firm’s philanthropic behavior, and CEOs with different levels of appearance have different attitudes towards philanthropy as a pro-social behavior (Ling et al. 2022). Analyzing the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon, individuals with a superior appearance often exhibit more kindness, sympathy, and altruism (Dion et al. 1972), and Wang et al. (2017) showed that individuals with an outstandingly attractive appearance are more likely to engage in moral actions. Furthermore, individuals with higher facial attractiveness often exhibit pro-social behavior as a response to preferential treatment from the outside world, which serves as feedback to society (Konrath and Handy, 2021; Wilson and Eckel, 2006). However, attractive individuals create a positive first impression with their appearance and also tend to appear more confident in their behavior and performance, which enhances the overall positive perception others have of them (Pfann et al. 2000). This confidence causes others to believe they have superior abilities (Mobius and Rosenblat, 2006). Therefore, society has high expectations of individuals who are attractive, including expectations of positive qualities and behaviors, which may encourage the individuals to participate more in social activities (Li et al. 2021). This idea can be applied to CEOs and corporate managers. CEOs with a beauty premium are more inclined to lead firms to actively fulfill voluntary social responsibilities (Wang et al. 2025). Moreover, environmental innovation by firms is a manifestation of fulfilling social responsibility (Arena et al. 2018), as well as moral and pro-social behavior (Suganthi, 2019).

Environmental innovation is defined as new or improved processes, practices, systems, and products that are beneficial to the environment and have a positive impact on sustainable development (Oltra and Jean, 2009). Environmental innovation is a way to create commercial value for firms, is beneficial for enhancing competitiveness (Dah et al. 2024), and also helps firms make rational use of resources (Sun and Sun, 2021). In other words, environmental innovation improves production efficiency and reduces operating costs for firms. Environmental innovation also means firms complying with environmental regulations, allowing them to avoid risks and enjoy various preferential policies (Leenders and Chandra, 2013; Shui et al. 2025). Moreover, environmental innovation can reduce resource consumption and pollution, which is conducive to promoting green environmental protection, which can be seen as the contribution of firms to human society (Ge et al. 2018; Song and Yu, 2018). Therefore, environmental innovation by firms can improve people’s quality of life and facilitate firms’ active social responsibility (Jiménez-Parra et al. 2018).

Therefore, a highly attractive CEO not only presents a beautiful appearance but also contains moral beauty. Their behavior better reflects their pro-social nature; in response to external expectations, the attractive CEO is likely to encourage the firm to assume social responsibility. Environmental innovation is a pro-social behavior and a manifestation of the firm actively fulfilling social responsibility. That is to say, CEOs with high facial attractiveness have sufficient conditions to lead the firm towards an eco-friendly direction. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

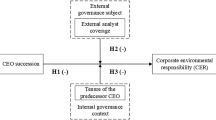

H1: The attractiveness of CEO’s faces has a positive impact on firms’ environmental innovation.

The mediating role of face awareness

The concept of saving face comes from the need to be respected, and individuals need to maintain their public image, reputation, and positive evaluation from the outside world (Hwang, 1987; Lim and Bowers, 1991). The willingness to face and be afraid of losing face is the awareness of face (Bao et al. 2003), which can also be understood as the desire of individuals to improve their social status and reputation within the social group (Zhang et al. 2011). If an individual values power, status, and image, and enjoys showcasing their identity, it indicates they have a high sense of face (Belk et al. 1982; French and Raven, 1959), and abstract concepts such as power, status, and image can be expressed in concrete forms such as wealth, knowledge, and beauty. Therefore, individuals who are noticeably attractive tend to value the advantages bestowed by their external image, which leads them to pay special attention to their self-esteem (Wade, 2000). This high level of self-esteem is a manifestation of high face awareness. Moreover, people with a superior appearance often exhibit a strong desire for a noble status and good reputation because an attractive appearance requires a high-quality status and reputation to match. After reaching a higher social status, they will work more actively and hard to stabilize it in order to avoid losing that status (He et al. 2019), which also confirms the importance of face-saving for people who are attractive.

For the group of corporate CEOs, upper-echelons theory suggests that facial features are both observable demographic background characteristics of executives and the most intuitive outward identification (Datta and Rajagopalan, 1998). This visual trait can significantly shape society’s evaluation of executives and form initial impressions. For example, CEOs with outstanding appearance are often perceived as more capable, credible, and leadership, leading to positive stereotypes (Halford and Hsu, 2020). It is worth noting that this initial impression formed based on facial advantages is not a static existence. In the long-term process of social interaction, CEOs with high facial attractiveness will continue to receive positive feedback from the outside world, which makes them highly sensitive to their own image and social evaluation (Hamermesh and Abrevaya, 2013). In other words, such CEOs are more likely to receive positive feedback and a positive image from others, and are more concerned about maintaining these advantages, which in turn fosters a strong sense of face and motivates impression management. According to the classic interpretation of impression management theory, in order to effectively maintain and enhance others’ positive evaluations of oneself, individuals will actively adopt various behaviors and strategies to shape their self-image (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). That is to say, CEOs with prominent physical appearance, driven by a strong sense of face, will actively manage their own impressions and take practical actions. Celebrity CEOs often have a strong sense of face to maintain their celebrity status and image, and within the framework of impression management, this sense of face drives them to take specific actions (Lee et al. 2020). CEOs typically have a higher sense of face management motivated by impression management, which ultimately drives them to maintain impression advantages (Lin et al. 2024; Zhou et al. 2023).

Face is not a unilateral existence, but an interdependent social resource that also requires the participation and recognition of others (Wan et al. 2016). Because if a person’s performance falls below the expectations of the outside world or there is a gap between their behavior and the standards required by their social status, they will lose face (Ho, 1976), while people with high face awareness will focus on their image and social status. If people’s behavior can earn them respect from others, they will save face (Zhao et al. 2019). Therefore, individuals often leverage pro-social qualities to seek a good word-of-mouth reputation to improve their self-image, social status, and gain respect from others and gain face. People with a strong sense of face will pay special attention to their personal image and social status, and crave positive evaluation and respect from others. In order to achieve these goals, they are more likely to exhibit pro-social behavior.

Research has found that people with a strong sense of face tend to focus on ecological issues (Shin et al. 2007) and are also more inclined to express their ecological and environmental vision through pro-social green behaviors, in order to enhance their social status and reputation (Griskevicius et al. 2010), thus gaining face. Compared to ordinary-looking CEOs, CEOs with a beauty premium tend to receive more attention, and their social status and image often receive high praise and expectations from the outside world. So, for CEOs with a beauty premium, losing face can have a negative impact on their personal image and social status, and engaging in pro-environmental actions can help them improve their status and gain face (Griskevicius et al. 2010). Therefore, they are more willing to promote environmental innovation in their firms. In other words, highly attractive CEOs are more inclined to lead firms in implementing environmental innovation because they have a stronger sense of face, so they are more likely to adopt pro-social behavior, and having a wider range of practices in environmental innovation is a manifestation of social responsibility and altruism. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Face awareness plays a positive mediating role between the facial attractiveness of CEOs and their firms’ environmental innovation.

The moderating role of firms’ visibility

Firm visibility reflects the firm’s public awareness (Campbell and Slack, 2006), which is one of the important characteristics of a firm and can be measured by the firm’s media exposure (Brammer and Pavelin, 2006). Based on stakeholder theory, visibility is a reflection of the information that a firm transmits to the outside world, and which attracts attention (Baker et al. 1999). This is facilitated by providing multiple channels for external stakeholders to understand the information of the firm, thereby alleviating the problems caused by information asymmetry. However, visibility can also increase the exposure of executives, who frequently appear in the public eye and have a high level of attention (Deng et al. 2024).

When the visibility of the firm is high, the CEO, as the highest executive officer of the firm, will inevitably attract public attention, thereby gaining more popularity. At this point, the positive image of a CEO with a high facial attractiveness will be repeatedly reinforced through media and other channels, and they may become a celebrity CEO themselves, which will significantly enhance the goodwill and recognition of the outside world towards them (Agnihotri and Bhattacharya, 2021; Li et al. 2019). The strong psychological security gained from this makes them inclined to believe that the public is more likely to accept and love them, even if they have done something wrong (Ling et al. 2022). Therefore, such CEOs are less sensitive to negative evaluations or image damage events, and do not need to be overly anxious about maintaining face. In other words, high firms’ visibility amplifies the strengthening effect of physical advantages on the positive impression of CEOs, thereby reducing their level of concern for adverse events and weakening their sense of face.

On the other hand, CEOs with high facial attractiveness, as their appearance itself is a symbol of a superior image, do not need to invest excessive effort in shaping their external image, which allows them to act with less concern and reduces their worries about potential face damage from conflicts (Chen et al. 2021; Shtudiner and Klein, 2020). In addition, in high-visibility environments, CEOs with outstanding appearances will receive more positive feedback from the media, which not only enhances their confidence but also makes them more likely to attribute certain successes to their own abilities (Chen et al. 2025; Fu et al. 2025). This inherent attributional tendency diminishes individuals’ reliance on others’ evaluations, thereby further reducing their sensitivity to face. It is worth noting that in low-visibility environments, CEOs with high facial attractiveness may need to actively showcase their physical advantages to gain benefits and shape their image (Wang et al. 2025). However, under high visibility, its image advantage has been established, allowing more energy to be invested in substantive operations and strategic decision-making of the firm (Klein and Shtudiner, 2021; Wang et al. 2019). Compared to actual business performance, the importance of face has significantly decreased, which has also contributed to the weakening of their sense of face. In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Firm visibility plays a negative moderating role between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness.

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical model of this study.

Method

Data sources

This study selected heavily polluting A-share listed firms in China from 2017 to 2022 as a sample. The firms’ financial data were sourced from CSMAR, the annual reports of the firms came from Juchao Information, and the environmental innovation data of the firms, and the online news reporting data of the firms, all came from CNRDS. The green patent research database in CNRDS is a combination of Chinese patent data and the green patent classification number standards published by the World Intellectual Property Office. Considering the reliability and completeness of the data, this study excluded firms with ST and * ST, firms with missing data, and firms with CEO photos that did not meet the testing software requirements. Ultimately, balanced panel data were obtained for 381 heavily polluting firms and 636 CEOs. In order to reduce the impact of extreme values, this study applied winsorization at the 1% and 99% levels to all continuous variables.

Variable measurement

CEO facial attractiveness (CFA)

Using software to measure the attractiveness of a CEO’s face is an efficient way to obtain objective evaluation results, helping us to accurately capture and analyze facial features. The aim of software measurement is to accurately compare the facial ratio of the subject with the golden ratio to obtain an attractiveness score. This includes calculating the ratio of facial width to height, the ratio of nose to ear length, and nose width to face width, facial symmetry, and other indicators (Blankespoor et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2021; Schmid et al. 2008). This technology has been applied in the research of CEO facial attractiveness assessment by Halford and Hsu (2020), Liu et al. (2022), Yang et al. (2024), and Zhang et al. (2024), and has become one of the most popular methods for appearance assessment due to its scientific and objective advantages. This study obtained clear and complete frontal photos of CEOs from websites such as Sogou, Baidu, and the firm’s official websites based on the firm name and CEO's name. The inclusion criteria were that the CEO’s facial expression should be neutral, the photo should have no editing marks, and the resolution should be high enough. Drawing on the method of Chiu et al. (2024), Baidu AI facial recognition technology was used to recognize and score the CEO’s face for 150 key points, producing a score of 0–10, which was ultimately used as the CEO’s facial attractiveness score.

Environmental innovation (EI)

Based on the research by Brunnermeier and Cohen (2003) and Chang and Sam (2015) this study used the number of environmental innovation patents to measure the level of corporate environmental innovation. We considered that green invention patents can better reflect the level of corporate environmental innovation (Fu et al. 2023; Li, 2022), and so this study uses the number of authorized green invention patents to measure the level of environmental innovation of firms as detailed by Liao et al. (2024). Because some firms have no patent numbers, 1 was added to the number of patents before logarithmizing the values.

Face awareness (FW)

The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis posits that language reflects an individual’s values and cognition, and the words appearing in text can reflect an individual’s thoughts (Short et al. 2010). The annual report of a firm is the channel for communication between the CEO and the outside world. The CEO usually uses the annual report to convey the firm’s strategy, achievements, and plans to the outside world (Wagner and Fischer-Kreer, 2024). In addition, the annual report of a firm is carefully edited and confirmed by the CEO, and previous research has confirmed that the CEO’s involvement in the annual report is extremely high (Gamache et al. 2015). Meanwhile, Nadkarni and Chen’s (2014) study revealed that the words used by CEOs in corporate annual reports are closely related to the words used in press releases and public speeches. Therefore, the annual report of a firm can reflect the personal preferences and awareness of the CEO (Eggers and Kaplan, 2009; Marcel et al. 2011; Nadkarni and Barr, 2008). For example, Gamache et al. (2020) and Liang et al. (2024) have used corporate annual reports to measure CEOs’ regulatory focus, while Liao et al. (2025) have also used corporate annual reports to measure CEOs’ dependency-based self-construction awareness. Based on the method of Yadav et al. (2007), we conducted text analysis on the firms’ annual reports, using the frequency of keywords to measure the CEO’s face awareness. First, starting from the definition of face awareness, “achievement,” “reputation,” “external image,” “status,” and “influence” were selected as seed words. Second, after studying a large number of annual reports of firms, we established eight keywords: “enormous value,” “first place,” and “international advanced level.” Finally, we used Python software to calculate the frequency of each keyword in the annual reports of sample firms, and added 1 to take the logarithm for processing, in order to measure the CEO’s face awareness.

Firm visibility (FV)

Using Wang’s (2016) method, we measured the firms’ visibility by multiplying the number of times their name appeared in online news and then taking the logarithm of this count to determine the news coverage rate.

Control variables

Referring to the research of Liao et al. (2024) and Zhu et al. (2023), CEO’s gender, tenure, and dual role integration were selected as control variables. Firm age, size, return on assets (Roa), gross profit margin (GP), board size (Board), and total number of shares held by the largest shareholder (Top1) were selected as control variables at the firm level, and firm age and size were logarithmically processed.

Results

Descriptive analysis

This study used Stata 18 for statistical analysis, and Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results for each variable.

Table 1 shows that the average CEO facial attractiveness is 4.1643, with a standard deviation of 1.2114, indicating that the sample data fluctuates greatly, and the collected data is comprehensive. The average value of firm visibility is 4.1001, with a standard deviation of 0.8339. The data range is relatively large, indicating that different firms have varying degrees of visibility. The correlation coefficient between CEO facial attractiveness and environmental innovation is 0.0527, which is significant at the 5% level; the correlation coefficient between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness is 0.1132, which is significant at the 1% level. Overall, the coefficients did not exceed 0.5, indicating that there are no multicollinearity issues.

Hypothesis testing

Benchmark regression results

This study constructed a panel data model with dual fixed effects and conducted multiple regression analysis to explore the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on firms’ environmental innovation. The results are presented in Table 2.

From Model 1a in Table 2, it can be seen that the control variable, integration of two roles, has a significant impact on the environmental innovation of the firm. Model 1b shows that the coefficient of influence of CEO facial attractiveness on firms’ environmental innovation is 0.0177, which is significant at the 5% level. This indicates that CEO facial attractiveness has a positive promoting effect on firms’ environmental innovation. Therefore, H1 is supported.

Mediation effect test

Table 3 shows the regression results of the mediating effect of face awareness between CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation.

Model 2a in Table 3 indicates that gender and the number of shares held by the largest shareholder have a significant impact on face awareness. According to Model 2b in Table 3, the coefficient of influence of CEO facial attractiveness on face awareness is 0.0169, which is significant at the 10% level. This indicates that CEO facial attractiveness has a significant positive impact on face awareness, and CEOs with a beauty premium are more face-conscious. Model 2c shows that the coefficient of influence of face awareness on environmental innovation is 0.0383, which is significant at the 10% level. The coefficient of influence of CEO facial attractiveness on firms’ environmental innovation is 0.0170, which is significant at the 5% level. This indicates that after adding face awareness, the relationship between CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation remains unchanged. Therefore, it can be concluded that face awareness plays a mediating role between CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation; that is, the higher the CEO facial attractiveness, the stronger their face awareness will be, ultimately promoting firms’ environmental innovation. Therefore, hypothesis H2 is supported.

Moderating effect of firm visibility

Table 4 shows the moderating effect of firm visibility on the relationship between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness.

Model 3a in Table 4 indicates a positive effect of CEO facial attractiveness on face awareness, with an impact coefficient of 0.0166, which is significant at the 10% level. Model 3b shows that after adding interactivity, the significance level remains unchanged, while the interaction term of CEO facial attractiveness and firm visibility has an impact coefficient of −0.0158 on face awareness, significant at the 5% level. This indicates that firm visibility plays a negative moderating role between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness, and therefore, hypothesis H3 is supported. The negative moderating effect of firm visibility is shown in Fig. 2.

Robustness testing

To verify the robustness of the results, we included control variables at the CEO and corporate levels. We also selected regional-level control variables to address important factors that were omitted in the regression analysis. Following the methods of Zhang et al. (2022), Liu et al. (2020), and Luo et al. (2021), we included industrial structure (ISU), government intervention level (GOV), research and development intensity (R&D), industrialization level (Ind), technology market development level (TM), and informatization level (Inf) as control regional variables, as shown in Table 5. The results are consistent with the above research.

Heterogeneity testing

Chinese firms can be divided into state-owned firms and non-state-owned firms based on the nature of property rights. State-owned firms have significant advantages in resource acquisition, credit environment, financing conditions, and policy support and are more likely to engage in environmental innovation (Andrews et al. 2022). Therefore, we used Andrews et al.’s method and divided firms into state-owned and non-state-owned ones to explore the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on environmental innovation. The results are shown in Table 6.

From Model 5b in Table 6, it can be seen that the facial attractiveness of CEOs of state-owned firms has a significant promoting effect on environmental innovation, with a coefficient of 0.0352, which is significant at the 5% level, while the CEO facial attractiveness of non-state-owned firms does not have a significant effect on environmental innovation.

Conclusion and discussion

This study takes heavily polluting A-share listed firms in China from 2017 to 2022 as its sample, and explores the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on environmental innovation from the perspective of the upper-echelons theory. The mediating role of face awareness was examined, and the moderating effect of firm visibility. The final research conclusions are as follows.

First, CEO facial attractiveness positively influenced firms’ environmental innovation. Previous studies have mainly focused on the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on themselves, such as salary levels, career development, etc. (Colombo et al. 2022). This study extends the scope of research to the corporate level and is consistent with the findings of Wang et al. (2025), who found that the attractiveness of the CEO’s face remains an important factor in driving corporate social responsibility. But what sets this study apart is that it profoundly reveals the important role of CEO facial attractiveness in driving firms’ environmental innovation, further expanding the factors driving firms’ environmental innovation and filling the gap in previous research. At the same time, extending the boundaries of upper-echelons theory, existing research has categorized CEO facial attractiveness into the personal traits of executives from the perspective of upper-echelons theory. Based on this, this study continues to provide insights for subsequent reasons. Facial attractiveness is undoubtedly the most prominent trait of individuals, and CEOs with high facial attractiveness often exhibit more enthusiasm and kindness, as well as a greater willingness to be responsible and contribute to society (Ling et al. 2022). Particularly amid the growing severity of environmental challenges, CEOs who prioritize physical appearance proactively drive the implementation of environmental innovation initiatives. Such efforts not only yield tangible environmental benefits for contemporary society but also lay a solid foundation for safeguarding the well-being of future generations.

Second, face awareness plays a positive mediating role between CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation. CEOs are not entirely rational; they also pursue social status, reputation, influence, and achievements. Furthermore, CEOs with a beauty premium often have a better image and higher status and are given more positive (Cipriani and Zago, 2011). CEOs who prioritize beauty often have the motivation to maintain or further increase this privilege, which significantly enhances their sense of face. In order to maintain or win face, from the perspective of impression management, CEOs who prioritize beauty will achieve this goal through environmental innovation measures. Leading firm in environmental innovation often leads to positive evaluations, social status, and respect from the public, and can also continue to shape an excellent personal image (Liao et al. 2025), which is beneficial for enhancing the CEO’s face among peers. In addition, this study applies impression management theory to the fields of facial attractiveness, face awareness, and environmental innovation, effectively linking the three and extending the application scope of impression management theory, providing a new perspective for subsequent research.

Third, firm visibility plays a negative moderating role between CEO facial attractiveness and face awareness. The results show that when firm visibility is high, CEOs with a beauty premium are less concerned about face. In the annual reports of high-visibility firms, they often use more cautious and conservative wording to reduce risks such as litigation and other factors (Thng, 2019), and this masks the CEO’s strong sense of face. Moreover, when firm visibility is high, CEOs with a beauty premium will be more cautious in their words and actions, because positive evaluations can bring pressure on individuals to maintain an enhanced image, even resulting in more interpersonal competition. Therefore, CEOs may feel uncomfortable with these positive evaluations and even avoid them (Cook et al. 2022; Reichenberger et al. 2018; Weeks et al. 2019). In China, Eastern culture emphasizes the importance of humility and appearing low-key, so CEOs with a beauty premium often display behaviors that signal humility and pragmatism. In the public spotlight, CEOs need to approach positive evaluations rationally and pay attention to their public words and actions (Reichenberger et al. 2019; Weeks, 2015), which may lead to CEOs deliberately concealing their face-consciousness. However, in high-visibility firms, the CEO’s achievements depend on their professional abilities. Therefore, even when an attractive CEO garners substantial attention, they will still prioritize practical actions and tangible achievements to secure recognition—rather than focusing on face-saving.

Fourth, in terms of the nature of firm property rights, the attractiveness of CEOs of state-owned firms had a promoting effect on environmental innovation, while this effect was not seen in non-state-owned firms. State-owned firms have a natural connection with the government, and CEO facial attractiveness is more likely to attract attention from the outside world, including government agencies. On the one hand, CEOs can strengthen the connection between their firms and the government through environmental innovation (Oliver and Holzinger, 2008), reduce policy uncertainty, and strive for political favoritism and benefits (Ovtchinnikov et al. 2020). On the other hand, firms’ environmental innovation improves the prospects for future promotion of CEOs of state-owned firms (Chen et al. 2016), which is also a potential factor causing different results in the nature of firm property rights.

Managerial implications

The findings of this study enrich the upper-echelons theory and have implications for the development of firms. Firstly, the personal characteristics of the CEO will affect the operation and decision-making of the firm; therefore, the firm should guide the CEO’s traits reasonably, so that they can move towards the direction that is conducive to firm operation and environmental innovation, and transform the traits into driving factors for fulfilling social responsibility. Secondly, the CEO is the “business card” of the firm, so it is necessary for CEOs to pay attention to their image, which is conducive to shaping the image of the firm and bringing it closer to meeting stakeholder expectations. Firms should guide their employees’ face awareness psychology correctly, and design a reasonable incentive system to transform face awareness into action, thereby improving their performance and contribution to the firm. Finally, using the firm’s visibility to create a better personal image for the CEO to gain market recognition can promote products and improve the positive image and profitability of the firm by showcasing its social responsibility and environmental innovation achievements to the outside world.

Research limitations and future research directions

The findings of this study provide new insights into the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on firms’ environmental innovation, but it has some limitations. First, this study selected firms from China’s heavily polluting industries, which indicates that the value of generalizability still needs further testing. Therefore, future research can examine other industries in manufacturing and services. Second, this study only evaluates attractiveness based on the CEO’s facial appearance, but physical attractiveness also includes aspects such as height, body shape, temperament, and personality. Future research can explore these aspects when considering the CEO’s personal traits to add to our findings. Third, this study used annual reports for text analysis to measure CEO face awareness. Although it is a creative method, future research could use methods such as questionnaire surveys and interviews to measure CEO face awareness. Finally, the CEOs selected in this study are deeply influenced by Chinese culture, and future research could choose different cultural backgrounds. Based on this, we will continue to explore how the face consciousness of CEOs with a beauty premium will change according to firm visibility.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Agnihotri A, Bhattacharya S (2021) Can CEOs’ facial attractiveness influence philanthropic behavior? Evidence from India. Manag Organ Rev 17(1):112–142

Ahmed S, Ranta M, Vähämaa E, Vähämaa S (2023) Facial attractiveness and CEO compensation: Evidence from the banking industry. J Econ Bus 123:106095

Al-Shaer H, Albitar K, Liu J (2023) CEO power and CSR-linked compensation for corporate environmental responsibility: UK evidence. Rev Quant Financ Account 60(3):1025–1063

Andrews DS, Fainshmidt S, Ambos T, Haensel K (2022) The attention-based view and the multinational corporation: Review and research agenda. J World Bus 57(2):101302

Arena C, Michelon G, Trojanowski G (2018) Big egos can be green: A study of CEO hubris and environmental innovation. Br J Manag 29(2):316–336

Baker HK, Powell GE, Weaver DG (1999) Does NYSE listing affect firm visibility? Financ Manag 28(2):46–54

Bao Y, Zhou KZ, Su C (2003) Face consciousness and risk aversion: do they affect consumer decision‐making? Psychol Mark 20(8):733–755

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529

Belk RW, Bahn KD, Mayer RN (1982) Developmental recognition of consumption symbolism. J Consum Res 9(1):4–17

Blankespoor E, Hendricks BE, Miller GS (2017) Perceptions and price: Evidence from CEO presentations at IPO roadshows. J Account Res 55(2):275–327

Borghesi R, Houston JF, Naranjo A (2014) Corporate socially responsible investments: CEO altruism, reputation, and shareholder interests. J Corp Financ 26:164–181

Brammer S, Pavelin S (2006) Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies. J Bus Financ Account 33(7‐8):1168–1188

Brunnermeier SB, Cohen MA (2003) Determinants of environmental innovation in US manufacturing industries. J Environ Econ Manag 45(2):278–293

Bushee BJ, Miller GS (2012) Investor relations, firm visibility, and investor following. Account Rev 87(3):867–897

Cainelli G, De Marchi V, Grandinetti R (2015) Does the development of environmental innovation require different resources? Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. J Clean Prod 94:211–220

Campbell DJ, Slack R (2006) Public visibilty as a determinant of the rate of corporate charitable donations. Bus Ethics: A Eur Rev 15(1):19–28

Chang CH, Sam AG (2015) Corporate environmentalism and environmental innovation. J Environ Manag 153:84–92

Chen FF, Jing Y, Lee JM (2014) The looks of a leader: Competent and trustworthy, but not dominant. J Exp Soc Psychol 51:27–33

Chen JZ, Kolev K, Luo X, Yang L (2025) What are they looking at: directors’ facial appearances and shareholder voting outcomes. J Bus Res 198:115479

Chen J, Zhu D, Ding S, Qu J (2024) Government environmental concerns and corporate green innovation: Evidence from heavy‐polluting enterprises in China. Bus Strategy Environ 33(3):1920–1936

Chen LH, Loverio JP, Shen CC (2021) The role of face (Mien-Tzu) in Chinese tourists’ destination choice and behaviors. J Hosp Tour Manag 48:500–508

Chen X, Qin Q, Wei YM (2016) Energy productivity and Chinese local officials’ promotions: Evidence from provincial governors. Energy Policy 95:103–112

Chiu YL, Wang JN, Hsu YT (2024) Can lawyers’ facial attractiveness increase the popularity or customer satisfaction? An example of Expert Q&A Services. Serv Sci 16(4):332–348

Cipriani GP, Zago A (2011) Productivity or discrimination? Beauty and the exams. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 73(3):428–447

Colombo MG, Fisch C, Momtaz PP, Vismara S (2022) The CEO beauty premium: Founder CEO attractiveness and firm valuation in initial coin offerings. Strateg Entrep J 16(3):491–521

Cook SI, Moore S, Bryant C, Phillips LJ (2022) The role of fear of positive evaluation in social anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract 29(4):352–369

Dah BA, Dah MA, Frye MB (2024) Board refreshment: like a breath of fresh air. Br J Manag 35(1):378–401

Datta DK, Rajagopalan N (1998) Industry structure and CEO characteristics: An empirical study of succession events. Strateg Manag J 19(9):833–852

Deng L, Jiang P, Li P, Zhu W (2024) Media coverage and bond covenants: evidence from China. Br J Manag 35(4):1798–1821

Dion K, Berscheid E, Walster E (1972) What is beautiful is good. J Person Soc Psychol 24(3):285–290

Eagly AH, Ashmore RD, Makhijani MG, Longo LC (1991) What is beautiful is good, but….: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychol Bull 110(1):109–128

Eggers JP, Kaplan S (2009) Cognition and renewal: Comparing CEO and organizational effects on incumbent adaptation to technical change. Organ Sci 20(2):461–477

Elsheikh T, Hashim HA, Mohamad NR, Youssef MAEA, Almaqtari FA (2025) CEO masculine behavior and earnings management: does ethnicity matter? J Financ Report Account 23(3):959–983

Fang L, Li Z (2024) Corporate digitalization and green innovation: Evidence from textual analysis of firm annual reports and corporate green patent data in China. Bus Strategy Environ 33(5):3936–3964

French JR, Raven B (1959) The bases of social power. Stud Soc Power 150:259–269

Fu L, Hu Y, Lu C (2025) CEO Overconfidence and open innovation in Chinese biopharmaceutical industry: does top management team social capital matter? Technol Anal Strateg Manag 37(7):784–797

Fu L, Yi Y, Wu T, Cheng R, Zhang Z (2023) Do carbon emission trading scheme policies induce green technology innovation? New evidence from provincial green patents in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(5):13342–13358

Galaskiewicz J, Burt RS (1991) Interorganization contagion in corporate philanthropy. Adm Sci Q 36(1):88–105

Gamache DL, McNamara G, Mannor MJ, Johnson RE (2015) Motivated to acquire? The impact of CEO regulatory focus on firm acquisitions. Acad Manag J 58(4):1261–1282

Gamache DL, Neville F, Bundy J, Short CE (2020) Serving differently: CEO regulatory focus and firm stakeholder strategy. Strateg Manag J 41(7):1305–1335

Ge B, Yang Y, Jiang D, Gao Y, Du X, Zhou T (2018) An empirical study on green innovation strategy and sustainable competitive advantages: Path and boundary. Sustainability 10(10):3631

Godfrey PC (2005) The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad Manag Rev 30(4):777–798

Goffman E (1955) On face-work: An analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatry 18(3):213–231

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Van den Bergh B (2010) Going green to be seen: status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J Person Soc Psychol 98(3):392–404

Gull AA, Hussain N, Khan SA, Mushtaq R, Orij R (2023) The power of the CEO and environmental decoupling. Bus Strategy Environ 32(6):3951–3964

Guo J, Kim JY, Kim S, Zhou N (2022) CEO beauty and management guidance. Asian Rev Account 30(1):152–173

Halford JT, Hsu HCS (2020) Beauty is wealth: CEO attractiveness and firm value. Financ Rev 55(4):529–556

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manag Rev 9(2):193–206

Hamermesh DS, Abrevaya J (2013) Beauty is the promise of happiness? Eur Econ Rev 64:351–368

He X, Yin H, Zeng Y, Zhang H, Zhao H (2019) Facial structure and achievement drive: Evidence from financial analysts. J Account Res 57(4):1013–1057

Ho DYF (1976) On the concept of face. Am J Sociol 81(4):867–884

Huang H, Chang Y, Zhang L (2023) CEO’s marketing experience and firm green innovation. Bus Strategy Environ 32(8):5211–5233

Hwang KK (1987) Face and favor: The Chinese power game. Am J Sociol 92(4):944–974

Jiménez‐Parra B, Alonso‐Martínez D, Godos‐Díez JL (2018) The influence of corporate social responsibility on air pollution: Analysis of environmental regulation and eco‐innovation effects. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 25(6):1363–1375

Kim JYJ, Shi L, Zhou N (2021) CEO pulchronomics and appearance discrimination. Asian Rev Account 29(3):443–473

Klein G, Shtudiner Z (2021) Judging severity of unethical workplace behavior: Attractiveness and gender as status characteristics. BRQ Bus Res Q 24(1):19–33

Konrath S, Handy F (2021) The good-looking giver effect: The relationship between doing good and looking good. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 50(2):283–311

Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M (2000) Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull 126(3):390–423

Lee G, Cho SY, Arthurs J, Lee EK (2020) Celebrity CEO, identity threat, and impression management: Impact of celebrity status on corporate social responsibility. J Bus Res 111:69–84

Leenders MA, Chandra Y (2013) Antecedents and consequences of green innovation in the wine industry: The role of channel structure. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 25(2):203–218

Li F, Morris T, Young B (2019) The effect of corporate visibility on corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 11(13):3698

Li J (2022) Can technology-driven cross-border mergers and acquisitions promote green innovation in emerging market firms? Evidence from China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(19):27954–27976

Li M, Triana MDC, Byun SY, Chapa O (2021) Pay for beauty? A contingent perspective of CEO facial attractiveness on CEO compensation. Hum Resour Manag 60(6):843–862

Li X, Guo F, Wang J (2024) A path towards enterprise environmental performance improvement: How does CEO green experience matter? Bus Strategy Environ 33(2):820–838

Liang J, Jain A, Newman A, Mount MP, Kim J (2024) Motivated to be socially responsible? CEO regulatory focus, firm performance, and corporate social responsibility. J Bus Res 176:114578

Liao Z, Liu Y (2022) Why firm’s reactive eco-innovation may lead to consumers’ boycott. Br J Manag 33(2):1110–1122

Liao Z, Chen K, Ren X (2025) Star CEOs and firms’ environmental innovation: the role of interdependent self‐construal and risk perception. Bus Strategy Environ 34(3):2993–3007

Liao Z, Dong J, Weng C, Shen C (2019) CEOs’ religious beliefs and the environmental innovation of private enterprises: The moderating role of political ties. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(4):972–980

Liao Z, Liu P, Bao P (2024) Environmental information disclosure, environmental innovation, and firms’ growth performances: The moderating role of media attention. Sustain Dev 32(1):425–437

Liao Z, Xu L, Zhang M (2024) Government green procurement, technology mergers and acquisitions, and semiconductor firms’ environmental innovation: The moderating effect of executive compensation incentives. Int J Prod Econ 273:109285

Lim TS, Bowers JW (1991) Facework solidarity, approbation, and tact. Hum Commun Res 17(3):415–450

Lin S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Geng H (2024) The impact of CEO reputation on ESG performance in varying managerial discretion contexts. Financ Res Lett 70:106368

Ling L, Luo D, Li X, Pan X (2022) Looking good by doing good: CEO attractiveness and corporate philanthropy. China Econ Rev 76:101867

Liu C, Gao X, Ma W, Chen X (2020) Research on regional differences and influencing factors of green technology innovation efficiency of China’s high-tech industry. J Comput Appl Math 369:112597

Liu Y, Qian X, Wu Q (2022) Officials’ turnover, facial appearance and FDI: evidence from China. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 58(3):896–906

Lu Y, Ntim CG, Zhang Q, Li P (2022) Board of directors’ attributes and corporate outcomes: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int Rev Financ Anal 84:102424

Luo G, Guo J, Yang F, Wang C (2023) Environmental regulation, green innovation and high-quality development of enterprise: Evidence from China. J Clean Prod 418:138112

Luo Y, Salman M, Lu Z (2021) Heterogeneous impacts of environmental regulations and foreign direct investment on green innovation across different regions in China. Sci Total Environ 759:143744

Marcel JJ, Barr PS, Duhaime IM (2011) The influence of executive cognition on competitive dynamics. Strateg Manag J 32(2):115–138

Mills J, Hogan KM (2020) CEO facial masculinity and firm financial outcomes. Corp Board: Role Duties Compos 16(1):39–46

Mobius MM, Rosenblat TS (2006) Why beauty matters. Am Econ Rev 96(1):222–235

Mrkajic B, Murtinu S, Scalera VG (2019) Is green the new gold? Venture capital and green entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 52:929–950

Nadkarni S, Barr PS (2008) Environmental context, managerial cognition, and strategic action: An integrated view. Strateg Manag J 29(13):1395–1427

Nadkarni S, Chen J (2014) Bridging yesterday, today, and tomorrow: CEO temporal focus, environmental dynamism, and rate of new product introduction. Acad Manag J 57(6):1810–1833

Oliver C, Holzinger I (2008) The effectiveness of strategic political management: A dynamic capabilities framework. Acad Manag Rev 33(2):496–520

Oltra V, Saint Jean M (2009) Sectoral systems of environmental innovation: an application to the French automotive industry. Technol Forecast Soc Change 76(4):567–583

Ortiz‐de‐Mandojana N, Bansal P, Aragón‐Correa JA (2019) Older and wiser: How CEOs’ time perspective influences long‐term investments in environmentally responsible technologies. Br J Manag 30(1):134–150

Ovtchinnikov AV, Reza SW, Wu Y (2020) Political activism and firm innovation. J Financ Quant Anal 55(3):989–1024

Pfann GA, Biddle JE, Hamermesh DS, Bosman CM (2000) Business success and businesses’ beauty capital. Econ Lett 67(2):201–207

Przychodzen J, Przychodzen W (2015) Relationships between eco-innovation and financial performance–evidence from publicly traded companies in Poland and Hungary. J Clean Prod 90:253–263

Reichenberger J, Smyth JM, Blechert J (2018) Fear of evaluation unpacked: day-to-day correlates of fear of negative and positive evaluation. Anxiety Stress, Coping 31(2):159–174

Reichenberger J, Wiggert N, Wilhelm FH, Liedlgruber M, Voderholzer U, Hillert A, Blechert J (2019) Fear of negative and positive evaluation and reactivity to social-evaluative videos in social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 116:140–148

Ridgway JL, Clayton RB (2016) Instagram unfiltered: Exploring associations of body image satisfaction, Instagram selfie posting, and negative romantic relationship outcomes. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19(1):2–7

Rosenblat TS (2008) The beauty premium: Physical attractiveness and gender in dictator games. Negotiat J 24(4):465–481

Rule NO, Ambady N (2008) The face of success: Inferences from chief executive officers’ appearance predict company profits. Psychol Sci 19(2):109–111

Schmid K, Marx D, Samal A (2008) Computation of a face attractiveness index based on neoclassical canons, symmetry, and golden ratios. Pattern Recognit 41(8):2710–2717

Scholz JK, Sicinski K (2015) Facial attractiveness and lifetime earnings: Evidence from a cohort study. Rev Econ Stat 97(1):14–28

Seifert B, Morris SA, Bartkus BR (2003) Comparing big givers and small givers: Financial correlates of corporate philanthropy. J Bus Ethics 45(3):195–211

Shin SK, Ishman M, Sanders GL (2007) An empirical investigation of socio-cultural factors of information sharing in China. Inf Manag 44(2):165–174

Short JC, Broberg JC, Cogliser CC, Brigham KH (2010) Construct validation using computer-aided text analysis (CATA) an illustration using entrepreneurial orientation. Organ Res Methods 13(2):320–347

Shtudiner Z, Klein G (2020) Gender, attractiveness, and judgment of impropriety: The case of accountants. Eur J Polit Econ 64:101916

Shui X, Zhang M, Wang Y, Smart P (2025) Do climate change regulatory pressures increase corporate environmental sustainability performance? The moderating roles of foreign market exposure and industry carbon intensity. Br J Manag 36(1):223–239

Sigall H, Landy D (1973) Radiating beauty: Effects of having a physically attractive partner on person perception. J Personal Soc Psychol 28(2):218–224

Song W, Yu H (2018) Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 25(2):135–150

Suganthi L (2019) Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. J Clean Prod 232:739–750

Sun X, Cifuentes‐Faura J, Xiao Y, Liu X (2024) A good name is rather to be chosen: The impact of CEO reputation incentives on corporate green innovation. Bus Strategy Environ 33(3):2413–2431

Sun Y, Sun H (2021) Green innovation strategy and ambidextrous green innovation: The mediating effects of green supply chain integration. Sustainability 13(9):4876

Tatoglu E, Frynas JG, Bayraktar E, Demirbag M, Sahadev S, Doh J, Koh SL (2020) Why do emerging market firms engage in voluntary environmental management practices? A strategic choice perspective. Br J Manag 31(1):80–100

Teeter P, Sandberg J (2017) Constraining or enabling green capability development? How policy uncertainty affects organizational responses to flexible environmental regulations. Br J Manag 28(4):649–665

Thng T (2019) Do VC-backed IPOs manage tone? Eur J Financ 25(17):1655–1682

Todorov A, Mandisodza AN, Goren A, Hall CC (2005) Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science 308(5728):1623–1626

Wade TJ (2000) Evolutionary theory and Self‐perception: Sex differences in body esteem predictors of Self‐perceived physical and sexual attractiveness and self‐esteem. Int J Psychol 35(1):36–45

Wagner A, Fischer‐Kreer D (2024) The role of CEO regulatory focus in increasing or reducing corporate carbon emissions. Bus Strategy Environ 33(2):1051–1065

Wan LC, Poon PS, Yu C (2016) Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility brands: the role of face concern. J Consum Mark 33(1):52–60

Wang J, Tian T, Xu L, Ru T, Mo C, Wang TT, Mo L (2017) What is beautiful brings out what is good in you: The effect of facial attractiveness on individuals’ honesty. Int J Psychol 52(3):197–204

Wang L, Wei F, Zhang XA (2019) Why does energy-saving behavior rise and fall? A study on consumer face consciousness in the Chinese Context. J Bus Ethics 160(2):499–513

Wang S, Wang X, Li Q (2025) Beauty premium: the impact of CEO facial attractiveness on corporate social responsibility. Chin Manag Stud 19(1):55–84

Wang T, Mo L, Mo C, Tan LH, Cant JS, Zhong L, Cupchik G (2015) Is moral beauty different from facial beauty? Evidence from an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10(6):814–823

Wang Y, Qiu Y, Luo Y (2022) CEO foreign experience and corporate sustainable development: Evidence from China. Bus Strategy Environ 31(5):2036–2051

Wang Z (2016) Firm visibility and voluntary environmental behavior. Land Econ 93(4):654–666

Weeks JW (2015) Replication and extension of a hierarchical model of social anxiety and depression: Fear of positive evaluation as a key unique factor in social anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther 44(2):103–116

Weeks JW, Howell AN, Srivastav A, Goldin PR (2019) Fear guides the eyes of the beholder”: Assessing gaze avoidance in social anxiety disorder via covert eye tracking of dynamic social stimuli. J Anxiety Disord 65:56–63

Wilson RK, Eckel CC (2006) Judging a book by its cover: Beauty and expectations in the trust game. Political Res Q 59(2):189–202

Yadav MS, Prabhu JC, Chandy RK (2007) Managing the future: CEO attention and innovation outcomes. J Mark 71(4):84–101

Yang C, Yang Z, Zhou W, Du P, Lu C (2024) The golden-mean fallacy: A medium-attractiveness face predicts less funding on a crowdfunding platform. Inf Manag 61(5):103963

Yuan B, Cao X (2022) Do corporate social responsibility practices contribute to green innovation? The mediating role of green dynamic capability. Technol Soc 68:101868

Zebrowitz LA, Hall JA, Murphy NA, Rhodes G (2002) Looking smart and looking good: Facial cues to intelligence and their origins. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 28(2):238–249

Zhang L, Ma X, Ock YS, Qing L (2022) Research on regional differences and influencing factors of Chinese industrial green technology innovation efficiency based on Dagum Gini coefficient decomposition. Land 11(1):122

Zhang XA, Cao Q, Grigoriou N (2011) Consciousness of social face: The development and validation of a scale measuring desire to gain face versus fear of losing face. J Soc Psychol 151(2):129–149

Zhang X, Wang Y, Xiao Q, Wang J (2024) The impact of doctors’ facial attractiveness on users’ choices in online health communities: A stereotype content and social role perspective. Decis Support Syst 182:114246

Zhang Y, Sun Z, Sheng A, Zhang L, Kan Y (2024) Can green technology mergers and acquisitions enhance sustainable development? Evidence from ESG ratings. Sustain Dev 32(6):6072–6087

Zhao H, Zhang H, Xu Y (2019) How social face consciousness influences corrupt intention: Examining the effects of Honesty–Humility and moral disengagement. J Soc Psychol 159(4):443–458

Zhou L, Long W, Qu X, Yao D (2023) Celebrity CEOs and corporate investment: A psychological contract perspective. Int Rev Financ Anal 87:102636

Zhu C, Li N, Ma J (2023) Environmental backgrounds of CEOs and corporate environmental management information disclosure: The mediating effects of financing constraints and media attention. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30(6):2885–2905

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (23&ZD101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Zhongju LIAO, Writing-original draft: Ke CHEN, Methodology: Xiaoyun REN.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any experiments conducted by the author on animal or human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, Z., Chen, K. & Ren, X. CEO facial attractiveness and firms’ environmental innovation: how does looking good lead to doing good?. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1553 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05879-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05879-5