Abstract

As a strategy for rural revitalization and poverty alleviation, the rural cluster residence policy has been implemented in 24 provinces across China. This study estimates the impact of rural cluster residence on gift-giving expenditure of rural households based on a dataset from Sichuan province. The results indicate that the rural cluster residence has increased the gift-giving expenditure of rural households. The mechanism analysis has proved that the rural cluster residence has improved the motivation of rural households to seek social status and increase social network bonds, thereby increasing rural households’ gift-giving expenditure. The results of this study have important implications for further reducing the gift-giving expenditure burden on rural households and realizing rural revitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amid the forces of globalization and modernization, rural areas across the globe are experiencing significant economic and social transformations. This shift is particularly pronounced in developing countries, where traditional lifestyles and economic practices are evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the largest developing nation, China stands at the forefront of these transformations. Over the past few decades, the country has experienced substantial socio-economic shifts in its rural regions, driven by various national policies that focus on promoting rural development. For instance, initiatives aimed at enhancing agricultural productivity and transforming rural life (Chen et al., 2008; Fan et al., 2004; Gong, 2018; Guo and Liu, 2021). Policies such as the “Rural Revitalization Strategy”, implemented in recent years, underscore the government’s commitment to addressing the challenges faced by rural areas while fostering sustainable economic growth (Chen, 2019; Ma and Mu, 2024).

Since the early 21st century, the Chinese government has actively pursued the “New Rural Construction” policy, aimed at enhancing farmers’ quality of life and modernizing rural areas. Among these initiatives, the Rural Cluster Residence policy (ReCR) has been considered as a pivotal strategy to address the imbalances in rural development (Chen et al., 2016). By relocating dispersed rural residents to centralized communities, the government aims to optimize land use, improve the efficiency of public services, and promote comprehensive rural development (Liu et al., 2020).

ReCR reflects not merely a domestic policy response within China, but aligns with a wider global trajectory of rural restructuring through planning and locally grounded implementation strategies. For instance, South Korea’s “New Village Movement” promoted rural modernization through collective resettlement, which improved basic amenities and housing (Asian Development Bank, 2012). Similar initiatives were undertaken in African countries such as Tanzania and Algeria, where centralized rural living was encouraged to reduce geographic isolation and improve service delivery (Alaci, 2010; Brebner and Briggs, 1982; Lerise, 2000). In Japan, voluntary relocation programs were introduced to mitigate rural depopulation while enhancing residents’ quality of life (Palmer, 1988). The United Kingdom, after World War II, introduced the Key Settlement Policy to stabilize rural populations (Lockhart, 1982).

According to the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission, 39,000 centralized residential areas and 2.6 million resettlement houses were built across the country, with plans to relocate 9.3 million registered poor individualsFootnote 1. Sichuan province, a major agricultural region in southwestern China, serves as an exemplary case study of the implementation of this policy. The region’s complex geography and diverse socio-economic structure provide a valuable context for examining the impacts of ReCR.

With the implementation of the ReCR policy, formerly dispersed households are relocated to centralized living areas, reducing the physical distance between families and increasing opportunities for social interaction. This social proximity is expected to influence the frequency and scale of gift-giving practices, which play a crucial role in traditional Chinese society, particularly in rural areas. In relationship-oriented societies like China, “gift-giving expenditure” generally refers to the economic costs incurred by individuals or families during social interactions, such as reciprocating favors or participating in ceremonies like weddings and funerals (Yan, 1998). Gift-giving is not only a means of maintaining social bonds but also reflects the continuation of cultural traditions (Kipnis, 1997).

In Western societies, the act of exchanging gifts among friends and family is a well-established practice that serves to reinforce interpersonal relationships and foster social bonds. Research by Andreoni and Bernheim (2009), Ellingsen and Johannesson (2008), and Levine (1998) indicates that gift-giving is often seen as a means of expressing care, appreciation, and commitment, contributing to the overall strength and stability of these relationships. Gifts can take many forms, and are often selected with the recipient’s preferences in mind, reflecting the thoughtfulness behind the gesture. In contrast, the culture of gift-giving in China has unique characteristics that reflect its social and historical context. Cash gifts, particularly in the form of “red envelopes” (cash in a red envelope), are prevalent during various celebrations and significant life events. This tradition, as noted by Yang (1994) and Bian (1997), is deeply rooted in Chinese culture, symbolizing good fortune, prosperity, and goodwill. The practice of giving red envelopes is especially significant in rural communities, where it is an essential part of social interactions and community dynamics. In rural Chinese communities, gift-giving practices are deeply embedded in the social fabric, playing a critical role in maintaining social networks and community cohesion (Hu et al., 2021; Chiu et al., 2023).

In recent years, with the acceleration of agricultural modernization in China, farmers’ incomes have increased steadily, leading to a significant rise in the value of cash gifts, accompanied by a continuous increase in gift-giving expenditures. However, Bulte et al. (2018) pointed out that gift-giving expenditures have gradually become a financial burden for rural households in China. Hu et al. (2021) suggest that gift-giving expenditures, while crucial for maintaining social relationships, may, as they escalate, negatively affect individual well-being. In fact, gift-giving expenditures account for as much as 20.1% of total household expenditures in some rural areas, according to the database used in this study. The reasonable gift-giving expenditure can reflect the normal consumption tendency of the family, but when the proportion of the gift-giving expenditure reaches a certain level, it may crowd out other essential household spending and negatively affect overall household welfare (Hu et al., 2021).

Prior studies have examined the determinants of gift-giving expenditures from various analytical perspectives. Confucian values around hierarchy and reciprocity strongly influence gift-giving expectations (Joy, 2001; Liu et al., 2010). The closeness, status gap, and nature of interpersonal relationships can affect gift value and selection (Caplow, 1982; Camerer, 1988). Individual factors such as income, age, and conformity also contribute to variations in gift spending behavior (Cheal, 1986; Givi and Galak, 2019; Zhang, 2022). Additionally, situational factors—such as the type and emotional tone of the occasion—shape both the norm and size of gift expenditures (Pieters and Robben, 1999; Hwang and Chu, 2019). However, few studies have examined how residential restructuring, such as ReCR, may reshape social interactions and alter gift-giving behavior.

The evolving nature of gift-giving expenditures in rural Chinese society reflects broader structural changes within these communities. Although such expenditures may appear voluntary on the surface, they are often driven by strong social norms, particularly under the centralized residential arrangements introduced by the ReCR policy. ReCR differs significantly from conventional urbanization. Instead of relocating rural residents to urban centers, it consolidates dispersed households into moderately scaled settlements within their original rural areas. Participants retain their agricultural hukou, land-use rights, and agrarian livelihoods.

Compared with the social disintegration often associated with urbanization, ReCR tends to preserve—and in some cases reinforce—existing social networks. The increased spatial proximity enhances social visibility and comparison, intensifying the pressure to conform to prevailing gift-giving norms (Chen et al., 2012). In China’s guanxi-based rural society, failure to reciprocate appropriately may lead to social exclusion and the erosion of informal support networks (Yan, 1998). As a result, gift-giving under ReCR becomes not only a cultural practice but also a financial obligation that can strain household welfare and undercut some of the intended benefits of the policy.

Building on these dynamics, it is crucial to explore whether and how ReCR influences rural households’ gift-giving behaviors. This study addresses this question by empirically examining the impact of ReCR on gift-giving expenditures and uncovering the underlying mechanisms.

Accordingly, in this study, we estimate the impact of ReCR on rural households’ gift-giving expenditure, and explore the impact-occurring mechanism, based on the first-hand data obtained from household survey in Sichuan province, China. The empirical results indicate that ReCR has increased the gift-giving expenditure of rural households. The mechanism analysis has proved that this increase is primarily driven by enhanced motivation among rural households to seek social status and strengthened social network bonds, both facilitated by the ReCR policy.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: First, existing research on ReCR primarily focuses on its positive impacts on rural infrastructure improvement and land use efficiency (Liu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019) and its influence on life satisfaction (Chen et al., 2016), clean energy choice (Liu et al., 2020), labor migration (Liu and Zhou,2021), energy poverty (Liu et al., 2023), health of the acting heads (Liu and Zhou, 2023) and welfare of rural households (Peng, 2015; Zhao and Zhang, 2017). However, few studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of ReCR on the rural households’ gift-giving expenditure. This study fills that gap by providing novel evidence on how spatial interventions can influence traditional social practices. Our findings align with those of Reddy et al. (2022), who show that targeted development programs in rural India reshape community-level social capital and reciprocity. Together, these studies underscore that distinct policy instruments—spatial restructuring in the case of ReCR and resource targeting in the Indian context—can lead to similar transformations in rural society.

Second, our study connects the ReCR policy to wider economic discourses by framing it as a form of residential concentration and spatial restructuring, consistent with themes in urban and regional economics on spatial agglomeration (Glaeser and Gottlieb, 2009; Henderson, 2010), development economics on rural relocation and infrastructure access (Arndt, 1981; McKenzie and Paffhausen, 2017), and social economics on signaling, comparison, and network-embedded reciprocity (Bourdieu, 1984; Putnam, 2000; Thaler, 1980). By situating a China-specific policy within global theoretical frameworks, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how spatial interventions affect economic outcomes.

Third, our mechanism analysis reveals that ReCR strengthens social network bonds, leading to increased gift-giving expenditures, aligning with Granovetter’s (1985) theory of embeddedness.

Fourth, this study employs an instrumental variable approach to effectively address the endogeneity issue, accurately identify the causal effect of the ReCR policy on rural household gift expenditures, thereby enhancing the robustness of the findings.

Finally, the study offers guidance for the development of policies that can steer gift-giving practices in a direction more conducive to the sound operation of society. The findings carry significant policy implications, particularly in terms of reducing the economic burden of gift-giving on rural households while still promoting the benefits of ReCR policies.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section “Policy background” provides the relevant policy background, Section “Data, variable, and method” describes the data and presents descriptive statistics of key variables, Section “Empirical findings” outlines the empirical analysis and robustness checks, Section “Mechanism analysis” discusses the mechanism analysis, and Section “Conclusions” concludes with policy recommendations.

Policy background

With the acceleration of urbanization, many rural laborers have migrated to urban areas, leading to the “hollowing out” of villages. To address the problem of serious waste of land resources in rural areas accordingly, in October 2004, the State Council issued the Decision on Deepening Reform and Strict Land Management, which encouraged provinces and municipalities to reorganize rural construction land while ensuring food production safety. Sichuan province has actively promoted the policy of Rural Cluster Residence as a key initiative under the broader framework of “New Rural Construction”Footnote 2.

The ReCR policy aims to relocate scattered rural households into moderately dense residential communities equipped with essential infrastructure, public services, and environmental facilities. Site selection is guided by considerations such as topography, accessibility, and planning feasibility, ensuring that resettled households benefit from improved living conditions and better access to public goods. The central objective is to modernize rural living environments while maintaining the essential character of rural communities.

ReCR fundamentally differs from conventional urbanization. Unlike urban migration, which often severs farmers’ ties to their land and disrupts traditional social networks, ReCR retains residents in their original rural territories–the land of the original villages, mostly or neighboring ones in some cases. Participants keep their agricultural hukou, land-use rights, and agrarian livelihoods. The size of individual settlements ranges from 6 to 536 households, underscoring the policy’s emphasis on moderate concentration rather than urban-scale clustering. This design seeks to preserve community cohesion and support rural revitalization rather than facilitate full-scale urban transformation.

Regional implementation of ReCR also reflects important institutional distinctions. In developed eastern provinces such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, rural housing reforms have sometimes led to the commodification of homesteads through apartment-style redevelopment, thereby weakening traditional rural bonds. In contrast, ReCR in Sichuan focuses on spatial reorganization without altering land tenure systems. Despite physical improvements to housing, all land and property remain under collective ownership, regulated by China’s Land Administration Law. Homesteads are not privatized or monetized, and non-participating households retain their original property.

During the extensive implementation phase, the ReCR policy was applied throughout Sichuan province, allowing each village to implement the policy. In the process of promoting ReCR residence, it is fully up to rural households’ willingness to participate in ReCR after the announcement of the relevant ReCR resettlement project and accompanying subsidy rule. In practice, approximately one year prior to the start of construction of ReCR settlements, village collectives publicly disclose key details of the program—including the location of the centralized settlement, the per capita housing area, the available housing typologies, and the corresponding subsidy scheme. Based on this information, rural households can voluntarily decide whether to participate in the ReCR program. For any given resettlement project, the subsidy formulation is identical for all households involved and is not negotiable and not manipulable, though the subsidy formulation may vary across resettlement projects. The size of the subsidy is deterministically pre-decided by two pre-ReCR household characteristics. One is the family size, representing the total number of family members with local agricultural hukou one year before the announcement of the resettlement project. The second variable is the pre-ReCR housing area approved by the local government when the original house was built several years or even decades ago (see Liu et al. (2020), Liu and Zhou (2021) for more background details and subsidy formulation examples).

Regardless of whether a household chooses to ultimately embrace ReCR, the household can calculate the one-time housing subsidy it would receive if it chose to embrace ReCR. The subsidy is a one-time, transferred directly to house constructors hired by the local governments, not through households, to cover part of the construction cost of ReCR housing in the fiscal year of house construction. Therefore, since the anticipated subsidy is deterministically pre-decided by two pre-ReCR household characteristics, it is conditionally independent after controlling for these two pre-ReCR household characteristics. Many studies have adopted the same causal identification strategy to control for key variables that affect both outcome variables and instrumental variables to ensure that the IV is independent conditionally (Angrist and Pischke, 2009; Angrist et al., 2010; Nunn and Wantchekon, 2011; Allcott et al., 2016).

Data, variable, and method

Data source

The data used in this study is derived from data obtained from on-site household surveys conducted in 2017 in Sichuan province, China. Data collection is based on the principle of stratified sampling (Please refer to Liu et al. (2020) for more details about sampling). All variables related to household expenditures—including gift-giving, income, and communication costs—refer specifically to the full calendar year of 2016.

The data includes: the characteristics of rural households’ family members, the characteristics of rural households’ housing and land, the assessment of rural households’ own living environment and village living environment, rural households’ income and expenditure, and the natural, economic, and social environmental characteristics of the administrative village. The dataset covers 20 county-level cities or districts, 105 villages, and 3551 rural households. After removing 51 observations with missing values, a final dataset of 3500 observations was obtained for analysis in this study.

In this study, the term “village” refers to the administrative village officially defined by the local government. The boundaries of the villages remain consistent before and after the implementation of the ReCR policy, and the villages serve as the core unit for sample grouping and fixed effects. Importantly, within a given village, both ReCR households (i.e., those that opted into the centralized resettlement) and non-ReCR households (i.e., those that remained in their original dwellings) may coexist. This intra-village variation is essential to our identification strategy.

Empirical model

To estimate the impact of rural cluster residence on the gift-giving expenditure of rural households, the benchmark model is constructed as followsFootnote 3:

We mainly adopt the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation method, and the corresponding first-stage equation and second-stage equation are as follows:

In the above three equations, i represents rural household; j represents administrative village where the rural household is located; k represents the within-town villages group which includes the villages administrated by the same town; Y represents the natural logarithm of gift-giving expenditure; ReCR represents the rural household’s choice of rural cluster residence; Sub_ReCR represents the instrumental variable of this study, i.e., anticipated one-time subsidy for a household; X represents a series of control variables impacting the rural household’s gift-giving expenditure including the above-mentioned two subsidy-determining pre-ReCR household characteristics, \(\omega ,\rho ,\varphi\) represent the fixed effect of within-town villages group fixed effects in the three equations.

Descriptive statistics of variables

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics results of the variables used in this study. In the full sample, the mean value of the variable of the logarithm of gift-giving expenditure is 8.335. About 26.1% of households chose to embrace ReCR. The mean value of the variable of the anticipated one-time subsidy is 6.157Footnote 4.

Empirical findings

Instrument validity tests

This study takes the anticipated one-time subsidy for choosing ReCR (Sub_ReCR) as an instrumental variable. The IV (Sub_ReCR) is a deterministic function of these exogenous pre-policy characteristics. One is the total number of family members with local agricultural hukou one year prior to the announcement of the resettlement project (Pre-ReCR family size), and the other is the pre-ReCR housing area approved by the local government for the original house (Pre-ReCR housing area).

To validate our IV approach, we conducted several tests. Firstly, this instrumental variable satisfies the relevance assumption. Column (1) of Table 2 reports the results of the first-stage regression, showing a coefficient of 0.031, which is significant at the 1% confidence level, indicating that the anticipated one-time subsidy of rural cluster residence increases the probability of rural households’ choice of rural cluster residence. In addition, the value of Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic is 184.62, which is far greater than the corresponding critical value 16.38 (Stock and Yogo, 2005). It proves that the instrumental variable used in this study is not a weak instrumental variable.

Secondly, our IV strategy rests on the exclusion assumption that ReCR is the only channel through which Sub_ReCR affects the outcome variables. To investigate whether this exclusion restriction is satisfied, we test whether the reduced-form relationship between Sub_ReCR and the outcome variables is insignificant in the subsamples where Sub_ReCR has an insignificant impact on ReCR (Angrist et al., 2010). To do a test, we extract a subsample out of the baseline sample in which the original housing age is less than or equal to 5 years. Specifically, households whose original housing was constructed within five years of the ReCR policy announcement. Since it costs a lot to build a house and the subsidy only covers a portion of the construction cost, these households have strong incentives to remain in their existing homes regardless of the subsidy. As shown in Table 2 (Columns 2 and 3), within this subsample, Sub_ReCR has no significant effect on ReCR adoption (first stage) or on gift-giving expenditure (reduced form). This subsample tests provide no evidence that the exclusivity assumption is violated.

Finally, we conduct a sensitivity analysis following the framework proposed by Cinelli and Hazlett (2020, 2022) and Cinelli et al. (2020), which quantifies how strong unobserved confounding factors would need to be to nullify the observed effects. Our results in Table 3 show that even if unmeasured confounders were as strong as the most predictive observed covariates (e.g., geomantic beliefs, household head education or household labor ratio), the main findings would remain robust.

Baseline regression results

Columns (1) and (3) of Table 4 respectively report the regression results of OLS and 2SLS. The regression results show that the ReCR has a positive impact on households’ gift-giving expenditure. The difference between OLS and 2SLS estimates may be caused by the endogeneity problem aforesaid. In order to determine whether the endogeneity problem exists, we conducted an endogeneity test. The results show that the null hypothesis is rejected at the 5% level, illustrating that the variable ReCR is an endogenous variable. Therefore, the interpretation of the regression results is based on the estimated results of 2SLS. The coefficient of the second-stage regression is 0.788, significant at 5% confidence level. The empirical results show that the rural cluster residence has increased the rural households’ gift-giving expenditure by nearly 120%. This indicates that moving to centralized residential areas has a significant impact on household gift-giving expenditureFootnote 5. In rural China, gift-giving is important for maintaining social relationships and status. By living closer together, households may face more frequent social interactions and increased pressure to participate in events like weddings and funerals, leading to higher gift-giving expenditures.

Robustness tests

In the following section, we further test the robustness of the baseline regression results. First, the standard errors of the benchmark regression are clustered at the level of village. We re-cluster the standard errors at the levels of town and county for the robustness test. The corresponding results are reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 5. The results show that the two-stage estimation result is always significant at the significance level of 5%, regardless of the clustering level.

Second, outliers can disproportionately affect regression outcomes by skewing the results, leading to biased or unreliable conclusions. To minimize the potential influence of outliers on the regression results, we excluded 37 households whose gift-giving expenditures exceeded the 99th percentile. The corresponding results, reported in column (3) of Table 5, remain robust, indicating that the findings are not driven by these extreme observations. This further strengthens the conclusion of this paper, demonstrating that the relationship holds even when the most extreme data points are excluded from the analysis.

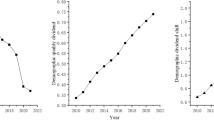

Third, we conduct a placebo test to prove the accuracy of the model setting and the reliability of the regression results. Specifically, step 1, we calculate the proportion of rural cluster residence in each within-town villages group; Step 2, delete all samples of rural cluster residence and regard the remaining samples as the test samples; Step 3, randomly set the rural households of cluster residence as placebo rural cluster residence for each within town villages group according to the proportion of rural cluster residence calculated in step 1 in the test samples; Step 4, the 2SLS estimation method is still used for regression, and the above process is repeated for 1000 cycles to check whether the coefficients of placebo rural cluster residence are significant. The results in Table 6 show that across 1,000 placebo replications, the proportions of estimated coefficients that are significantly different from zero at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance levels are 1.9%, 0.1%, and 0%, respectively. Thus, it is even more reasonable to believe in the robustness of the estimated results in this study.

Mechanism analysis

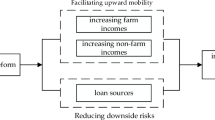

Empirical results demonstrated that ReCR has a positive impact on the household’s gift-giving expenditure. What is the mechanism of this impact? Many scholars have studied the behavior of gift-giving expenditure from a sociological perspective. We also try to use the social status theory and social network theory to explore the mechanisms of the impact of ReCR on the rural households’ gift-giving expenditure.

Social status perspective

Social interactions between Chinese families are relatively strong. In these close social networks, the size of the family’s housing and the level of gift-giving expenditure clearly reflect the family’s social status (Knight and Song, 2006; Brown et al., 2011). Gift-giving expenditure not only serves an intrinsic function but also acts as a means of displaying social status. The “relative income hypothesis”, introduced by Duesenberry (1949), suggested that consumption is influenced not only by individual income but also by those around them. People gain relative utility through “demonstration” and “comparison.” As part of household consumption, gift-giving expenditure is also influenced by these “demonstration” and “comparison” effects. Higher gift-giving expenditures by peers heighten individuals’ motivation to pursue social status, prompting households to signal their social standing by increasing their gift-giving expenditures (Chen et al., 2012). Simultaneously, individuals seek a sense of belonging within aspirational social groups through these expenditures. Consequently, when ReCR increases group-level gift-giving expenditures, rural individual households’ gift-giving expenditures similarly rise.

We analyze whether ReCR has brought about an increase in the group’s gift-giving expenditure, and then further analyze whether rural households are impacted by the “demonstration effect” or “comparison effect”. Specifically, we examine whether the group’s gift-giving expenditures have affected individual rural households’ gift-giving expenditures. We divide the total samples into different groups of rural households in the following way: Firstly, according to the status of ReCR of rural households, the rural households are divided into two parts: ReCR and non-ReCR. Secondly, the rural households in the ReCR and non-ReCR categories are divided into groups based on their village. For example, if a village (e.g., Village A) contains both ReCR and non-ReCR households, they are split into two groups: the ReCR group of Village A and the non-ReCR group of Village A. We construct the variable \({C}_{g(-i)}\) to measure the average gift-giving expenditure of all group members, excluding the considered household i as follows:

where \({N}_{g}\) is the total number of households in group g.

The regression results of ReCR on the average gift-giving expenditure of the peer group are presented in column (1) of Table 7. The result indicates that ReCR has increased the average level of gift-giving expenditure within the groups to which rural households belong. Column (2) shows that the impact coefficient (elasticity) of the group’s gift-giving expenditure on individual households’ gift-giving expenditure is 1.134, and its value is greater than 1, in line with the theory of “ratchet effect.” The intensified social proximity due to ReCR creates a “ratchet effect”, compelling households to exceed escalating gift norms to maintain their social standing (Chen et al., 2012). Because the amount of cash gift in the relationship is highly visible and has a signal transmission function, people use the gift-giving expenditure to show their social status. In the social interaction within the group to which they belong, rural households choose to increase the amount of cash gift in the household’s gift-giving expenditure.

Social network relation perspective

ReCR increases both the scale and intensity of social network connections among rural households. When rural households choose to migrate from scattered original residences to relatively densely populated residential areas, the geographical distribution of residential space changes from the scattered state to the centralized state (Liu and Zhou, 2021). The concentration of residents in rural areas can significantly enhance the social exchange opportunities for rural households. When families move from scattered living arrangements to relatively more densely populated residential areas, they encounter a higher frequency of social interactions. This shift not only fosters stronger community ties but also facilitates the sharing of resources, information, and support among neighbors.

From a social network theory perspective, social networks consist of both strong and weak connections (Granovetter, 1973). The frequency of social network connection can reflect the intensity of network connection. The more frequent connection of an individual with others means the stronger social network connection intensity. In the context of ReCR, improved communication infrastructure amplifies this effect. Digital tools such as WeChat and QQ have increasingly replaced traditional face-to-face visits, making social interactions more frequent and convenient.

It is important to recognize that while these tools strengthen local ties, they may also extend the scope of rural households’ social networks by enabling contact with distant relatives, urban acquaintances, and business partners. However, such outward connections do not necessarily come at the expense of local relationships. On the contrary, they may serve as a complement—particularly when local interactions have already been intensified through residential proximity.

Whether communication is concentrated within local networks or extends outward, the increase in interaction frequency reinforces interpersonal visibility and the perceived obligation to reciprocate. These forms of “social pressure” are key mechanisms that drive higher levels of gift-giving expenditure in rural China (Camerer, 1988; Carmichael and Macleod, 1997). In this way, ReCR not only strengthens social ties through physical proximity but also reshapes communication behaviors via digital connectivity, collectively contributing to increased household gift-giving.

Communication expenditure can reflect the scale of the network and the strength of its connections to a certain extent (Arora, 2023). We verify whether the scale and connection strength of the network have been increased and strengthened due to ReCR by exploring whether ReCR has brought about an increase in communication expenditure. The results in column (1) of Table 8 show that the ReCR has a significant positive impact on the family’s communication expenditure. The results in column (2) of Table 8 indicate that the increase in communication expenditure leads to an increase in gift-giving expenditure. The rise in communication expenditure among rural households due to centralized residence may reflect an expansion of the social network or the strengthening of social connections. The expansion in the scale of the social network and the strength of connections will lead to an increase in rural households’ gift-giving expenditure, which explains why the centralized residence leads to an increase in rural households’ gift-giving expenditure.

Social network structure perspective

The “structural approach” theory of social networks focuses on the network relationship structure in which individuals are embedded, and the benefits brought by these specific structures. Burt (1992) adopted a structuralist perspective to propose a structural hole theory: If an individual is connected to many unconnected individuals, this structure will be very beneficial to the individual; if the individual acts as a bridge between two unrelated groups, the benefits are further magnified. The structural hole provides opportunities for individuals to use information resources to make a profit, positioning them advantageously between networks (Podolny and Baron, 1997).

In rural China, individuals engaged in business activities naturally seek such advantageous positions by maintaining ties to multiple networks. By embedding themselves in both local and external economic relationships, they can access valuable upstream information (e.g., from wholesalers) and downstream demand signals (e.g., from consumers). However, maintaining these structural advantages requires continuous investment in social capital, often through gift-giving, which serves both to reinforce relationships and to signal trustworthiness and reciprocal intent.

The ReCR policy may facilitate this process indirectly by reshaping the spatial and infrastructural environment in which rural households operate. By increasing residential density and upgrading public infrastructure—particularly transportation—ReCR improves rural residents’ connectivity to external labor markets and commercial networks, thereby enhancing the feasibility of engaging in non-agricultural economic activities.

In addition, because ReCR settlements are often located at a relatively greater distance from agricultural land, households residing in these areas face higher opportunity costs associated with farming. This spatial reallocation of residence reduces the practicality of agricultural production, thus increasing the incentive to allocate labor toward off-farm pursuits.

Empirical evidence from our survey supports this mechanism. Compared to non-ReCR households, those living in ReCR settlements reside closer to transportation hubs (2.08 km vs. 3.06 km to the nearest bus stop) and significantly farther from their farmland (2.23 km vs. 0.53 km), suggesting both reduced logistical barriers to off-farm mobility and a reduced dependence on agriculture. Consequently, ReCR households are more likely to participate in non-agricultural sectors, where maintaining extensive and strategically positioned social networks becomes increasingly important for accessing economic opportunities.

The regression results in column (3) of Table 8 show that the ReCR significantly increases the probability of rural households’ participation in off-farm business activities; the regression results in column (4) show that rural households’ engagement in non-agricultural business activities leads to a significant increase in rural households’ gift-giving expenditure. This explains that the rural cluster residence brings about an increase in the family’s gift-giving expenditure by enhancing the probability of rural households’ non-agricultural business activities.

Conclusions

In this study, the first-hand microdata are used to investigate the impact of ReCR on the family’s gift-giving expenditure. The findings reveal that rural households choosing rural cluster residence experience an increase in their gift-giving expenditures. A series of robustness checks and placebo tests confirms the reliability of the empirical results. Further analysis of the underlying mechanisms suggests that centralized residence can increase gift-giving expenditures through improving the motivation of rural households to seek social status and increasing social network bonds.

Despite the strengths of this study, one important caveat of this study should be noted. The dataset does not provide detailed information on the identities or types of gift recipients. As such, we are unable to empirically distinguish whether increased gift-giving expenditures under ReCR are directed toward newly formed social ties or pre-existing relationships. While several indirect indicators—such as increased communication expenditures and peer convergence in gift-giving behavior—support our proposed mechanism of enhanced social interaction and status signaling, the lack of direct recipient data prevents a more granular assessment of how social networks evolve after relocation. Future research could address this gap by collecting qualitative or longitudinal data on the nature and direction of gift exchanges.

Our study finds that the ReCR significantly increases household gift-giving expenditures, and this effect presents both positive and negative dimensions. On the positive side, ReCR enhances residential proximity and infrastructure quality, which strengthens social interactions and community cohesion. These changes contribute to the formation of social capital and help sustain traditional mutual support systems in rural areas. On the negative side, we observe that for some households, gift-giving accounts for a large share of total expenditure, potentially crowding out essential spending such as education, healthcare, and productive investments. This is consistent with concerns raised in prior studies (Bulte et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2021).

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed. First, since ReCR leads to increased social interaction through the physical concentration of households, local authorities can reduce the economic pressure of gift-giving by investing in shared public facilities for hosting major social events. Establishing community centers, multipurpose halls, or other accessible venues within ReCR settlements can lower the costs of weddings and funerals, which are primary occasions for ceremonial expenditures. These shared infrastructures can help shift the focus away from private material display toward collective participation, thereby reducing household-level financial burdens.

Second, ReCR’s residential clustering tends to intensify social comparisons and gift reciprocity expectations. To moderate these effects, local governments and village collectives can facilitate the development of internal community norms that encourage more modest and rational gift-giving behavior. Rather than enforcing hard regulations, communities can adopt participatory village guidelines that reflect shared values. These soft norms can help realign expectations without directly intervening in culturally significant practices.

Third, ReCR creates socially visible settings that can also be leveraged positively. Publicly recognizing households or communities that adopt moderate gift-giving practices—such as simplified ceremonies or restrained monetary exchanges—can gradually shift prestige norms. By reinforcing the social value of moderation through recognition, rather than regulation, such incentives can reshape behavior in a way that is compatible with both economic resilience and cultural continuity.

Together, these recommendations aim to address the unintended rise in gift-related expenditures brought about by ReCR-induced social dynamics, while respecting the cultural foundations of rural community life.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in its Supplementary Information files.

Notes

Although ReCR was introduced as part of the broader “New Rural Construction Policy” (NRCP), it operates distinctively and sets it apart from other interventions under the same umbrella. Whereas the NRCP encompasses a wide range of rural development initiatives—such as environmental improvements and poverty alleviation programs—ReCR uniquely restructures the spatial configuration of rural households by encouraging voluntary relocation to centralized residential areas. This spatial consolidation not only changes living conditions but also alters patterns of social interaction and community engagement. These distinct implementation features of ReCR provide the empirical basis for isolating its specific effects from those of the broader NRCP framework.

It is important to note that both the treatment group (ReCR households) and the control group (non-ReCR households) were exposed to the same overarching NRCP environment. Therefore, any general effects from macro-level rural revitalization—such as poverty alleviation—would likely influence both groups similarly. The differential exposure to the ReCR intervention serves as the basis for causal identification.

It is worth noting that although both gift-giving expenditure (Y) and anticipated one-time subsidy (Sub_ReCR) are measured in yuan, they differ in their temporal scopes and distributions. The gift-giving expenditure captures the total annual amount spent by each household in 2016 on cash gifts related to social events (e.g., weddings and funerals). In contrast, the anticipated one-time subsidy (Sub_ReCR) refers to a one-time lump-sum subsidy computed at the time of the relevant ReCR project initiative announcement. Additionally, Sub_ReCR includes zero values for households in some villages, mechanically lowering its overall mean in the full sample.

To rule out concerns about transitional disruptions or anticipatory effects, we verified the relocation status of all ReCR households. Based on administrative records and field interviews, all participating households had relocated to centralized settlements by the time of the field survey. The latest relocation occurred no later than 2014, whereas gift-giving expenditure was measured for 2016. Thus, all ReCR households had resided in their new homes for at least 2 years, ensuring that the outcome variable reflects post-relocation behavior.

References

Alaci DSA (2010) Regulating urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa through cluster settlements: lessons for urban managers in Ethiopia. Theor Empir Res Urban Manag 5(14):20–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24861503

Allcott H, Collard-Wexler A, O’Connell SD (2016) How do electricity shortages affect industry? Evidence from India. Am Econ Rev 106(5):587–624. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140389

Andreoni J, Bernheim BD (2009) Social image and the 50-50 norm: a theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica 77(5):1607–1636. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7384

Angrist JD, Pischke J (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press

Angrist J, Lavy V, Schlosser A (2010) Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ 28(4):773–824. https://doi.org/10.1086/653830

Arndt HW (1981) Economic development: a semantic history. Econ Dev Cult Change 29(3):457–466. https://doi.org/10.1086/451266

Arora A (2023) Communication costs in science: evidence from the early internet. Industrial and Corporate Change. Oxford University Press

Asian Development Bank (2012) The Saemaul Undong movement in the Republic of Korea sharing knowledge on community-driven development. Available via Adb Reports. https://www.adb.org/publications/saemaul-undong-movement-republic-korea. Accessed Jun 2012

Bian Y (1997) Bringing strong ties back in: indirect ties, network bridges, and job searches in China. Am Econ Rev 62(3):366–385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657311

Bourdieu P (1984) A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA

Brebner P, Briggs J (1982) Rural settlement planning in Algeria and Tanzania: a comparative study. Habitat Int 6(5–6):621–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(82)90028-5

Bulte E, Wang R, Zhang X (2018) Forced gifts: the burden of being a friend. J Econ Behav Organ 155(1):79–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.08.011

Burt RS (1992) Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Brown PH, Bulte E, Zhang X (2011) Positional spending and status seeking in rural China. J Dev Econ 96(1):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.05.007

Camerer C (1988) Gifts as economic signals and social symbols. Am J Socio 94(S1):S180–S214. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2780246

Carmichael HL, Macleod WB (1997) Gift giving and the evolution of cooperation. Int Econ Rev 38(3):485–509. https://doi.org/10.2307/2527277

Caplow T (1982) Christmas gifts and kin networks. Am Socio Rev 47(3):383–392. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094994

Chen X, Kanbur R, Zhang X (2012) Peer effects, risk pooling, and status seeking: what explains gift spending escalation in rural China?. Available via SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1988708. Accessed 20 Jan 2012

Chen Y, Lü B, Chen R (2016) Evaluating the life satisfaction of peasants in concentrated residential areas of Nanjing, China: a fuzzy approach. Habitat Int 53:556–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.01.002

Chen X (2019) The core of China’s rural revitalisation: exerting the functions of rural area. China Agr Econ Rev 12(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/caer-02-2019-0025

Chen PC, Ming-Miin YU, Chang CC, Hsu SH (2008) Total factor productivity growth in China’s agricultural sector. China Econ Rev 19(4):580–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2008.07.001

Cheal DJ (1986) The social dimensions of gift behaviour. J Soc Pers Relat 3(4):423–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407586034002

Cinelli C, Hazlett C (2022) An omitted variable bias framework for sensitivity analysis of instrumental variables. Available via SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4217915. Accessed 28 Nov 2024

Cinelli C, Hazlett C (2020) Making sense of sensitivity: extending omitted variable bias. J R Stat Soc B 82(1):39–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssb.12348

Cinelli C, Ferwerda J, Hazlett C (2020) Sensemakr: sensitivity analysis tools for OLS in R and Stata. Available via SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3588978. Accessed 28 May 2020

Duesenberry J S (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Harvard University Press

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M (2008) Pride and prejudice: the human side of incentive theory. Am Econ Rev 98(3):990–1008. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.3.990

Fan S, Zhang L, Zhang X (2004) Reforms, investment, and poverty in rural China. Econ Dev Cult Change 52:395–421. https://doi.org/10.1086/380593

Givi J, Galak J (2019) Keeping the Joneses from getting ahead in the first place: envy’s influence on gift giving behavior. J Bus Res 101:375–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.046

Glaeser EL, Gottlieb JD (2009) The wealth of cities: agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the United States. J Econ Lit 47(4):983–1028. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.4.983

Gong B (2018) Agricultural reforms and production in China: changes in provincial production function and productivity in 1978–2015. J Dev Econ 132:18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.12.005

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Socio 78(6):1360–1380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392

Granovetter M (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am J Socio 91(3):481–510. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780199

Guo Y, Liu Y (2021) Poverty alleviation through land assetisation and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 105:105418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105418

Hu M, Xiang G, Zhong S (2021) The burden of social connectedness: do escalating gift expenditures make you happy? J Happiness Stud 22:3479–3497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00341-6

Henderson JV (2010) Cities and development. J Reg Sci 50(1):515–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00636.x

Hwang J, Chu W (2019) The effect of others’ outcome valence on spontaneous gift-giving behavior: the role of empathy and self-esteem. Eur J Mark 53(4):785–805. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2017-0602

Joy A (2001) Gift giving in Hong Kong and the continuum of social ties. J Consum Res 28(2):239–256. https://doi.org/10.1086/322900

Kipnis A B (1997) Producing guanxi_ sentiment, self, and subculture in a North China village. Duke University Press

Knight J, Song L (2006) The rural–urban divide: economic disparities and interactions in China. Oxf Dev Stud 34(4):389–411

Levine DK (1998) Modeling altruism and spitefulness in experiments. Rev Econ Dyn 1(3):593–622. https://doi.org/10.1006/redy.1998.0023

Li Y, Westlund H, Liu Y (2019) Why some rural areas decline while some others not: an overview of rural evolution in the world. J Rural Stud 68:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.003

Liu Y, Liu J, Zhou Y (2017) Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J Rural Stud 52:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.04.002

Liu Z, Zhou Z (2021) Rural centralized residence and labor migration: evidence from China. Growth Change 52(4):413–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12556

Liu Z, Zhou Z (2023) Rural centralized residences and the health of the acting heads of rural households: the case of China. China Econ Rev 80:102011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2023.102002

Liu Z, Zhou Z, Liu C (2023) Estimating the impact of rural centralized residence policy interventions on energy poverty in China. Renew Sust Energ Rev 168:112942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113687

Liu Z, Wang M, Xiong Q, Liu C (2020) Does centralized residence promote the use of cleaner cooking fuels? Evidence from rural China. Energ Econ 91:104895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104895

Lerise F (2000) Centralised spatial planning practice and land development realities in rural Tanzania. Habitat Int 24(2):185–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(99)00037-5

Liu S, Lu Y, Liang Q, Wei E (2010) Moderating effect of cultural values on decision making of gift‐giving from a perspective of self‐congruity theory: an empirical study from Chinese context. J Consum Mark 27(7):604–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011086353

Lockhart D (1982) Patterns of migration and movement of labor to the planned villages of north east Scotland. Scot Geogr Mag 98(1):35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00369228208736513

Ma W, Mu L (2024) China’s rural revitalization strategy: sustainable development, welfare, and poverty alleviation. Soc Indic Res 174:743–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03410-y

McKenzie D, Paffhausen AL (2017) What is considered development economics? Commonalities and differences in university courses around the developing world. World Bank Econ Rev 31(3):595–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhx015

Nunn N, Wantchekon L (2011) The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. Am Econ Rev 101(7):3221–3252. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.7.3221

Palmer E (1988) Planned relocation of severely depopulated rural settlements: a case study from Japan. J Rural Stud 4(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(88)90076-9

Peng Y (2015) A comparison of two approaches to develop concentrated rural settlements after the 5.12 Sichuan earthquake in China. Habitat Int 49:230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.05.027

Pieters R, Robben H (1999) Consumer evaluation of money as a gift: a two-utility model and an empirical test. Kyklos 52(2):173–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1999.tb01441.x

Putnam R. D. (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon Schuster. https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990

Podolny JM, Baron JN (1997) Resources and relationships: social networks and mobility in the workplace. Am Socio Rev 62(5):673–693. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657354

Chiu YB, Wang Z, Ye X (2023) Household gift-giving consumption and subjective well-being: evidence from rural China. Rev Econ Househ 21:1453–1472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09631-9

Reddy AA, Sarkar A, Onishi Y (2022) Assessing the outreach of targeted development programmes—a case study from a South Indian village. Land-Basel 11(7):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11071030

Stock J H, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In Andrew D, Stock J (eds), Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 80–108

Thaler R (1980) Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. J Econ Behav Organ 1(1):39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(80)90051-7

Yan Y (1998) The Flow of gifts: reciprocity and social networks in a Chinese village. J Asian Stud 57(4):1129–1132. https://doi.org/10.2307/2659326

Yang M G (1994) Gifts, favors, and banquets: the art of social relationships in China. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Zhang T (2022) Measuring following behaviour in gift giving by utility function: statistical model and empirical evidence from China. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01214-4

Zhao Q, Zhang Z (2017) Does China’s ‘increasing versus decreasing balance’ land-restructuring policy restructure rural life? Evidence from Dongfan village, Shanxi province. Land Use Policy 68:649–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.08.003

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by The Major Special Project of the Philosophy and Social Sciences Fund of Sichuan Province [No. SCJJ24ZD38] and The National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 72574187].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Menghan Wang: Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Investigation, Data Curation, Methodology. Zhong Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. Chunlan Ji: Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee of the Institute of Industrial Economics, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics on December 6, 2016 (No. SWUFE-IIE-20161201). All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The scope of the approval covered all aspects of the study, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis.

Informed consent

This study involved non-interventional research using in-person household surveys and interviews. The surveys and interviews took place between January 14 and September 26 in 2017. Informed consent in the instructions of the questionnaire for this study was obtained in person before each participant took part in the survey or interview. All respondents were clearly informed in plain language that the study aimed to examine the impacts of rural cluster residence and that the data collected would be used exclusively for academic purposes and analyzed at an aggregate level, without individual analysis of any participant’s data. Participants were assured that the survey and the survey and the interview were completely anonymous, and their confidentiality would be strictly protected. Participation was entirely voluntary. Respondents were informed of their right to decline to answer any question or to withdraw from the survey at any time without any adverse consequences. Given the anonymous and minimal-risk nature of the study, the investigators of this research explicitly stated that voluntary completion and submission of the survey and the interview would be regarded as an indication of informed consent. All participants were aged 18 years or above. No personally identifiable information was collected at any stage of the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Liu, Z. & Ji, C. Does rural cluster residence increase gift-giving expenditure of rural households?—evidence from Sichuan province in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05908-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05908-3