Abstract

Childhood experiences play a crucial role in shaping lifelong happiness, yet their long-term implications remain underexplored. Drawing on life course and multidimensional capital perspectives, we examine the association between childhood left-behind experiences (LBE) and adult happiness using panel data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The analysis is based on 4,464 Chinese individuals (mean of age = 30.5, with 48.3% being male) with LBE measured between the ages of 0 and 12. We find that LBE is associated with lower adult happiness. Mediation analysis indicates that the negative association operates primarily through declines in traditional human capital—especially physical and mental health—and weakened family social capital, including relationships with parents and spousal intimacy. In contrast, the role of new human capital is limited. Moreover, a robust kinship network may partially mitigate the adverse consequences associated with LBE. We further use the KHB method to decompose the association and quantify indirect pathways. Overall, the findings are consistent with the long-term implications of early adversity and underscore the relevance of considering early interventions to support left-behind children (LBC) and promote better life outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of global labor migration, China’s internal migration since the late 1970s stands out not only for its massive scale but also for its profound social implications. Millions of rural residents relocated to urban centers in search of better economic opportunities, resulting in the largest internal migration in China’s history and one of the most extensive globally. However, China’s rigid hukou (household registration) system continues to restrict migrant workers’ access to basic public services in cities, such as education and healthcare for their children (Wei and Chen 2018). Consequently, a significant number of rural children have been left behind in their hometowns, often under the care of grandparents or other relatives. In 2010, the population of left-behind children (LBC) was estimated at 61.03 million (All-China Women’s Federation 2013). As these children have matured and entered the labor market, their happiness provides insights into the broader social welfare in China. According to the World Happiness Report 2025, China’s average life evaluation score stands at 5.921 out of 10, ranking 68th globally—leaving substantial room for improvement (Helliwell et al. 2025). With 376 million migrants recorded in the 2020 national census, the prevalence of LBC is expected to persist, with many transitioning into adulthood (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). Therefore, examining how LBE relates to adult happiness is of great significance for improving the overall level of subjective well-being in China.

While extant research has predominantly explored the short-term associations of parental migration with LBC, less attention has been paid to the long-term consequences of these experiences. The separation induced by parental migration deprives children of direct parental care and emotional support, often leading to the development of negative personality traits such as loneliness, low self-esteem, and increased social anxiety (Lu 2011). Furthermore, these children tend to exhibit reduced emotional well-being, particularly in positive emotional development, which adversely affects both their physical and psychological health (Yuan and Xing 2017). The absence of parental guidance further contributes to academic underachievement among LBC, as they generally fall behind their peers in school performance (Li 2013). Moreover, these children are more vulnerable to problematic behaviors such as truancy, internet addiction, and other forms of deviant behavior (Ye and Lu 2011; Meng and Yamauchi 2017).

Also missing from the extant research is an exploration of the long-term impact of LBE on happiness among the general adult population, as existing studies have focused on specific subgroups such as university students and migrant workers. Recent studies suggest that individuals with LBE tend to exhibit lower levels of happiness (Zhou et al. 2014; Yao and Zhang 2018), reduced emotional connectedness with parents, and increased pessimism about future family life (Zhao et al. 2018). For university students, LBE are correlated with heightened feelings of inferiority and insecurity, which subsequently contribute to increased aggression (Zhang and Xu 2020) and impair non-cognitive abilities (Guo 2020). Similarly, migrant workers who experienced being left behind during childhood tend to develop low self-esteem, coupled with an excessive sense of self-reliance, which complicates their ability to socialize effectively (Liu and Xu 2020). Moreover, existing research on the long-term associations of LBE has paid insufficient attention to both the mechanisms—how early-life separation reduces adult happiness—and the heterogeneity of outcomes across different types of parental absence.

To address these gaps, this article draws on life course theory (Elder 1994) and the multidimensional capital framework (Schultz 1990; Heckman et al. 2006), conceptualizes LBE as a critical early-life adversity that may be associated with slower accumulation of various forms of human capital—educational, physical, psychological, non-cognitive skills, and family social capital—that are known to influence long-term happiness (Coleman 1988; Xu et al. 2013). The current study contributes to the literature in three key ways. First, it addresses a critical gap by analyzing the mechanisms through which LBE influences adult happiness from the perspective of multidimensional capital accumulation, offering a novel and comprehensive explanation that has been largely overlooked in previous research. Second, the study further broadens the scope of analysis by shifting the focus from specific groups, such as university students and migrant workers, to the entire adult population, thereby enhancing the generalizability of its findings. Third, the research adopts a multifaceted approach to LBE by considering the type of parental absence (father-only absence, mother-only absence, or both parents absent), the age stage (0–3 age stage, 4–12 age stage, or both the 0–3 and 4–12 age stages), and the duration (ranging from six months to over three years), providing a nuanced understanding of the phenomenon. Additionally, the use of a two-way fixed-effects model with multi-period panel data from the CFPS, combined with PSM and IV methods, provides a rigorous framework to examine the association between LBE and adult happiness, helping to mitigate selection bias and address potential issues of reverse causality.

Literature review

Definitions and Measurements of LBE

The definition of LBC varies across studies and is generally structured around three key dimensions: (1) whether the definition requires both parents or only one parent to be absent; (2) the duration of parental absence—how long must a parent be away for the child to be considered left-behind (e.g., one year, six months, or three months); and (3) the age range of children who qualify as left-behind (Zhou and Duan, 2006).

Most existing studies address one or more of these dimensions. A majority of scholars adopt the broader definition that a child is considered left-behind if at least one parent is away for work (Duan and Yang 2008; Sun and Wang 2016). In contrast, some researchers argue that only children whose parents are both absent experience a substantial disruption in parental supervision, leading to a distinct form of “parent-child separation” and emotional detachment. These studies define LBC strictly as children with dual-parent absence (Liu 2008). Regarding the duration of absence, many studies take six months as a practical threshold, based on evidence that such a time span is associated with measurable declines in children’s well-being (Hao and Cui 2007; Tan 2011). Others apply more stringent or more lenient criteria, using a threshold of one year (Sun and Wang 2016) or even four months (All-China Women’s Federation Research Group 2013). As for the age definition, most studies do not explicitly discuss it. However, some limit their research subjects to those under 18 years old (Duan et al. 2013), aligning with the international standard. According to Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), a child is defined as “every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier” (United Nations 1989).

As the first generation of children of migrant workers has now entered adulthood, the focus of LBC research has gradually shifted from left-behind status to LBE (Ye 2019). The definition of LBE generally builds upon the established LBC definitions, referring to whether an individual has ever been left behind during childhood. Some studies further distinguish the experience by stage, duration, and age of occurrence (Liu et al. 2022), while others categorize it based on parental migration type (e.g., father-only absence, mother-only absence, or both parents absent) (Liang and Li 2021; Han et al. 2023).

In line with these definitions, this study defines LBE as having one or both parents away from home for six months or more. The measurement further distinguishes LBE by the type of parental absence, duration of being left-behind, and the age stage during which the experience occurred.

Heterogeneous effects of LBE on adult happiness

Life course theory posits that an individual’s trajectory is profoundly shaped by the broader social structure, with childhood representing a pivotal phase in personal development. Experiences during this formative period are believed to exert enduring implications throughout the life course (Elder 1994, 2002). Parental absence during childhood can weaken attachment among LBC and is linked with reduced happiness in their university years, ultimately reducing their happiness. (Zhou et al. 2014). Importantly, these adverse associations are not limited to childhood but persist into adulthood.

Parents fulfill distinct roles in their children’s upbringing, with mothers primarily providing physical nurturing and fathers often assuming responsibility for social education (Fei 1998). Existing research suggests that the presence of both parents—what is often termed as “dual-parent nurturing”—is optimal for children’s development (Wu et al. 2018). Li et al. (2019) found that while the absence of one parent did not significantly affect children’s happiness, the absence of both parents notably diminished the happiness of LBC. Li et al. (2008) demonstrated that mothers not only address children’s daily needs with meticulous care but also provide essential emotional support, whereas fathers’ involvement tends to be less comprehensive in both practical and emotional domains. These findings imply that the absence of a parent may affect children’s happiness differently, depending on whether it is the father or the mother who is absent. Furthermore, parental absence may have long-lasting associations, continue to influence happiness into adulthood. Based on this, we hypothesize that the absence of fathers and mothers will have differential impacts on adult happiness.

The development of children’s abilities follows distinct stages, with specific skills emerging at critical junctures in the life course. Missing these ‘sensitive periods’ can result in substantial developmental deficits that may be difficult or costly to compensate for later in life (Cunha et al. 2010). Research consistently links early childhood experiences to long-term psychological outcomes, indicating that parental absence during these formative stages can significantly disrupt emotional and psychological development (Thompson 2008). Consequently, such disruptions have enduring negative implications for individuals’ happiness in later life.

According to Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, ages 4 to 12 correspond to two critical stages: the initiative vs. guilt stage (preschool) age and the industry vs. inferiority stage (school age). During these periods, children actively engage with their environment, developing their imagination and social skills. When their efforts are supported, they cultivate a sense of achievement and happiness. Conversely, if their autonomy is restricted, they may experience diminished initiative and self-confidence, which can have long-lasting repercussions on their happiness in adulthood (Erikson 1968). These years thus represent a pivotal “sensitive period” for the formation of happiness (Luby et al. 2013; Gee et al. 2013; Caspi et al. 2003). Given the importance of this developmental window, parental absence during these formative years is expected to exert a particularly detrimental impact on long-term happiness.

Several studies suggest that health inequalities are often the result of cumulative disadvantages rooted in structural positions, which progressively build up over the life course and lead to systematic disparities in health outcomes among individuals or groups (Dannefer 2003). In line with this framework, the duration of LBE appears to have a compounding association with children’s psychological well-being. As the length of time spent in left-behind circumstances increases, so too does the negative impact on mental health. Liu et al. (2022) found that longer cumulative periods of being left behind are significantly associated with greater reductions in happiness during adulthood.

Traditional human capital, new human capital accumulation and adult happiness

Schultz’s human capital theory, which first conceptualized individuals as resources for investment, posits that human capital can be enhanced through five primary channels: medical and healthcare investment, on-the-job training, formal education, adult learning, and labor migration (Schultz 1990). Among these, subsequent research emphasizes that education and health are the most important components of human capital (Heckman 2019).

However, parental labor migration can negatively impact the accumulation of educational human capital, as LBC often experience reduced parental supervision, leading to poorer academic performance (Li 2013). Education consistently has a positive relationship with happiness across age groups, with higher education levels being particularly correlated with greater happiness among younger people (Qiu and Zhang 2021). Specifically, higher education significantly enhances happiness. Moreover, participation in educational activities later in life, particularly among the elderly, has been shown to enhance happiness by creating positive learning environments (Sun and Liu 2020). Thus, parental migration-induced disruptions in educational attainment can have lasting negative impacts on both the human capital and happiness of LBC.

Parental migration also affects the accumulation of health-related human capital among LBC. Physically, reduced parental care and companionship result in poorer health outcomes, including malnutrition, compared to their non-left-behind peers (Li and Zang 2011). Psychologically, parental absence exacerbates stress and feelings of loneliness among LBC (Duan et al. 2023), contributes to a lack of security. Furthermore, LBC are also more susceptible to experiences of bullying than their peers (Chen et al. 2021), which can have long-term detrimental implications for their psychological health. Adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse and family discord, negatively affect mental health throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Crowne et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2019), further influencing economic and social status in later life (Metzler et al. 2017). Existing research indicates that both physical and psychological health contribute to improved happiness, with psychological health exerting a greater influence than physical health (Xu et al. 2013). Therefore, we posit that LBE hinders the accumulation of both educational and health-related human capital, thereby negatively affecting adult happiness.

Heckman et al. (2006) introduced the concept of “new human capital”, expanding the research focus beyond traditional domains such as education and health to include non-cognitive skills. Non-cognitive abilities hold significant investment value during both early and later stages of childhood development (Cunha et al. 2010), although they are more malleable and easier to cultivate during the later stages (Heckman 2000). Parental absence during the critical and sensitive periods of non-cognitive skill formation hinders the accumulation of new human capital for LBC, limiting opportunities for later compensation. The separation caused by parental migration is associated with reduced openness and emotional stability of LBC (Cui and Xu 2021), particularly as the income effect of maternal migration is insufficient to offset the negative impact of separation (Liu et al. 2021). Zhang and Li (2017) found that agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and emotional stability are all positively correlated with happiness in a study of university students. We hypothesize that LBE weakens the accumulation of new human capital, thereby negatively affecting happiness in adulthood.

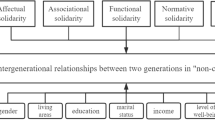

Family social capital accumulation and adult happiness

Coleman (1988) proposed that the relationship between parents and children can be understood as social capital, specifically family social capital. He emphasized that key factors influencing the development of children’s social capital include parent-child interaction, reciprocity, and trust. Parental migration results in spatial separation and weakened parent-child bonds, thereby impeding the accumulation of family social capital among children, and these implications may last into adulthood. Existing studies have shown that family social capital contributes positively to happiness (Zhang and Wan 2020). We hypothesize that parental migration impedes the accumulation of family social capital, which in turn negatively affects children’s happiness in adulthood.

In addition to its implications for children’s family social capital, parental migration also influences family dynamics more broadly. Bowen’s family systems theory suggests that individuals tend to replicate the relationship patterns they learned in their family of origin when forming future interpersonal relationships, such as in romantic, spousal, and intimate relationships (Bowen 1993). These patterns are transmitted to subsequent generations (Zhou et al. 2021) and are, to some extent, dependent on the accumulation of family social capital. This leads us to consider the intimacy between children and their spouses as a crucial form of family social capital. Parental labor migration often results in another form of family separation—between spouses—which hinders the development of intimacy, causing relational distance that can be passed on to the next generation. Existing research shows that more harmonious family relationships—particularly between spouses—correlate with higher levels of family happiness (Song et al. 2014). Therefore, we expect that LBE may reduce marital intimacy in adulthood, thereby negatively affecting adult happiness.

In the mid-20th century, the work of Talcott Parsons and other modern sociologists laid the foundation for the theory of family modernization (Parsons 1943). This theory posits that, under the forces of industrialization and urbanization, traditional patriarchal and extended families gradually gave way to atomized nuclear families, which were better suited to the individualistic and egalitarian values of modern society (Goode 1986). However, since the 1970s, this theory has been increasingly questioned and revised. The revised “developmental family modernization theory” emphasizes that although kinship networks no longer dominate the functioning of nuclear families in contemporary society, they still play vital roles in providing material support, emotional comfort, and behavioral role models. In this way, kinship networks remain an important support system for nuclear families to cope with various risks (Coall and Hertwig 2010; Milardo 2010). Accordingly, family research has shifted from an exclusive focus on modernity and individualism to a renewed recognition of the positive role of extended family ties and kin networks during periods of social transformation (Tang 2010).

In families where parents migrate to urban areas for work, caregiving responsibilities are often assumed by grandparents or the parents’ siblings (Chen and Liu 2012), forming a de facto “extended family” structure. In essence, these close relatives also constitute an integral part of the family’s social capital. In practice, when parents are absent, children tend to develop stronger ties with other family members. Therefore, we advocate for a broader understanding of family social capital that incorporates extended kinship ties, in order to better capture the full scope of the social environment surrounding LBC. We further argue that broader family social capital can, to some extent, compensate for the material and psychological harms caused by parental absence.

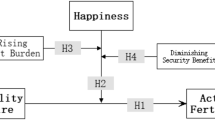

Based on these findings, we propose the following hypotheses: (1a) the LBE group has lower levels of happiness compared to non-LBE group; (1b) Different types of parental migration (e.g., father-only absence, mother-only absence, or both parents absent) will have varying impacts on adult happiness; (1c) Adults who were left behind during sensitive period for happiness perception will experience lower levels of happiness; and (1d) The longer the duration of being left behind, the lower the individual’s happiness in later life.

Furthermore, grounded in a multidimensional capital accumulation perspective, we hypothesize that the impact of LBE on adult happiness is mediated through human capital and family social capital. Specifically, LBE will negatively affect the accumulation of (2a) educational capital, (2b) physical health, (2c) mental health, and (2d) non-cognitive abilities, thereby reducing adult happiness.

In terms of family social capital, we propose that LBE weakens core familial relationships:(3a) it damages the relationship with the father, (3b) it impairs the relationship with the mother, and (3c) it reduces spousal intimacy in adulthood, all of which negatively affect adult happiness. Building further on the extended family perspective, we hypothesize that:(3d) stronger kinship network resources (e.g., care and support from grandparents, uncles, or aunts) may serve a compensatory function and buffer the adverse consequences of being left behind and mitigate the negative impact of LBE on adult happiness.

The research framework, including the mediation and moderation analyses, is shown below (see Fig. 1).

Data and methodology

Data

This study utilizes the data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), conducted by the Chinese Center for Social Science Research (CSSR) at Peking University. The CFPS 2010 baseline survey covered 25 out of 31 provinces, collecting data at the individual, family, and community levels. It established a longitudinal cohort of participants, including all family members and their future biological or adopted children. The present research focuses on the impact of LBE on adult happiness, drawing from the 2010 baseline questionnaire regarding parental non-residence and happiness measures from the follow-up surveys conducted in 2014, 2018, and 2020. A longitudinal sample from the 2010 survey, with successful follow-ups in the subsequent years, was analyzed.

The baseline survey includes 33,598 individuals. To examine the long-term associations between LBE and adult happiness, we construct a balanced panel dataset based on the following sample restriction steps: First, as the study focuses on rural LBE, we retained only individuals whose household registration (hukou) was classified as agricultural at age 3, yielding 27,969 observations. Second, to control for historical shifts in migration patterns following China’s economic reforms, we restricted the sample to individuals born after 1980, consistent with existing literature (Zheng et al. 2022), resulting in 5666 individuals. Third, to ensure the measurement of adult happiness, we limited the sample to individuals aged 18 or older at the time of the happiness survey, reducing the sample to 4877. Fourth, we excluded individuals who did not live with their parents due to parental death or divorce. Only respondents whose parents were both alive and in a marital relationship in 2010 were retained, leaving 4043 observations. Fifth, we excluded respondents who answered “don’t know” or refused to answer the four key questions used to define LBE, yielding a baseline sample of 3860 valid cases. Finally, to ensure consistency in outcome measurement, we retained only those individuals who provided valid responses to the happiness question in all three follow-up waves (2014, 2018, and 2020). This produced a balanced panel of 1488 individuals, contributing a total of 4464 person-year observations (1488 individuals × 3 waves) in the final analysis.

Measures

The CFPS measures adult happiness using a single-item overall happiness scale. Respondents rate their happiness on a scale from 0 to10, based on the question, “How happy do you feel (score)?” This data was collected in the CFPS surveys conducted in 2014, 2018, and 2020. The mean happiness score for the sample was 7.571.

To assess respondents’ LBE, the CFPS 2010 questionnaire included four questions about parental absence during the infancy and childhood stages: “What was the longest continuous period your father/mother did not live with you by age 3?” and “What was the longest continuous period your father/mother did not live with you between ages 4 and 12?“The questions capture the type, age stage, and duration of parental absence, which are essential elements in defining the LBE during childhood. Consistent with established research, LBC are identified as those who have been separated from one or both parents for more than six months due to parental migration for work (Zhou et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2018). Based on these definitions, we derived four key indicators to characterize LBE:

-

1.

Left-Behind Status: Whether or not the child was left behind.

-

2.

Type of Left-Behind: Categorized as father-only absence, mother-only absence, or both parents absent.

-

3.

Age Stage: The age range during which the child was left behind (0-3 age stage, 4–12 age stage, or both the 0–3 and 4–12 age stages).

-

4.

Duration: The length of the left-behind period, categorized into four groups: six months to one year, one to two years, two to three years, and more than three years.

A respondent is classified as having experienced left-behind if they reported a separation of more than 24 weeks in response to any of the four questions. This classification enables a nuanced understanding of the varying impacts of parental absence on children, taking into account different types, age stages, and durations of separation.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, 8.2% of the respondents reported having experienced left- behind status during childhood, defined as being separated one or both parents for a period exceeding six months. In terms of the type of LBE, 0.4% of the sample had only their mother absent, 4.57% had only their father absent, and 3.23% experienced the absence of both parents. These data indicate that the most common forms of LBE involve the father or both parents migrating for work.

Regarding the age at which children were left behind, the highest incidence (4.64%) occurred during the 4–12 age stage, while the lowest proportion (0.87%) was during infancy (0–3 age stage). Additionally, 2.69% of respondents experienced being left behind during both the infancy (0–3 age stage) and childhood stage (4–12 age stage). It is noteworthy that the proportion of children left behind during the infancy stage, when parental care is critically important, is lower than in the childhood stage.

In terms of the duration of the LBE, the largest proportion of respondents (2.89%) were left behind for more than three years, followed by those who experienced one to two years (2.15%), two to three years (1.82%), and six months to one year (1.34%).

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of LBE by type, age stage, and duration. To further examine the association between LBE and adult outcomes, Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the dependent variable (happiness) and mediating variables (multidimensional capital) stratified by LBE status. Notable differences are observed between the two groups across key variables, including happiness, father relationship and mother relationship.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of key variables stratified by LBE. On average, individuals with LBE report lower happiness scores (7.260) than those without such experience (7.599). Relative to the non-LBE group, the LBE group shows lower physical and mental health levels and non-cognitive ability scores; their average years of education are slightly greater (10.669 vs. 10.532), and the difference is not statistically significant. In terms of family social capital, respondents with LBE report more distant relationships with both parents and slightly lower ratings of spousal intimacy. These observed differences offer preliminary evidence that LBE may be associated with a range of adult outcomes across psychological, social, and cognitive domains, highlighting the potential mechanisms to be examined in subsequent empirical analyses.

The mediating variable in this study is multidimensional capital, encompassing traditional human capital, new human capital and family social capital.

Traditional human capital includes education and health, with health further divided into physical and mental components. The average level of educational attainment among respondents was 10.543 years, approximately equivalent to the completion of the first year of high school. Regarding physical health, a significant proportion of respondents rated themselves as relatively healthy (43.2%), healthy (23.4%), or very healthy (19.4%). For analysis purposes, respondents with physical health scores above the mean were classified as healthy; otherwise, they were categorized as unhealthy. Overall, 86.0% of respondents were considered healthy.

Mental health was assessed using the CES-D8 scale from the CFPS 2018 and 2020 datasets (Turvey et al. 1999; Van and Earleywine 2011; Karim et al. 2015), ensuring consistency in the analysis of the mental health mechanism. Earlier CFPS data (CFPS 2014) used the K6 scale but were excluded for uniformity. Respondents were asked to reflect on the frequency of eight feelings or behaviors experienced over the past week, including: (1) I felt depressed. (2) I felt that everything I did was an effort. (3) My sleep was restless. (4) I was happy. (reverse-scored) (5) I felt lonely. (6) I enjoyed life. (reverse-scored) (7) I felt sad. (8) I could not get “going”. Responses were recorded on a scale of 0 to 3, indicating the frequency of these feelings or behaviors: 0 = Most or all of the time (5–7 days), 1 = Occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days), 2 = Some or a little of the time (1–2 days), 3 = Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day). Items (4) and (6) were reverse-coded to align with others. Scores across all eight items were standardized and summed to produce a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 24, where higher scores represent better mental health. The mean mental health score in the sample was 18.590, suggesting that the respondents generally displayed good mental health.

The concept of “new human capital” has increasingly emphasized the importance of non-cognitive abilities. Research frequently uses tools such as the Self-Esteem Scale (Cunha et al. 2010), the Internal and External Control Scale (Rotter et al. 1966), and the Big Five Personality Inventory (Costa and McCrae 1992) to measure these abilities. Chinese scholars suggest that the Big Five personality traits provide a comprehensive framework for understanding non-cognitive abilities in the Chinese context (Wang et al. 2010). Costa and McCrae (1992) formalized the Big Five Personality Taxonomy, classifying non-cognitive abilities into five traits: conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and emotional stability.

The CFPS 2018 questionnaire provides comprehensive data on the Big Five personality traits, which are absent in the 2014 and 2020 surveys. This study uses the 2018 data to measure five dimensions of non-cognitive abilities, each assessed by three items rated on a 1-to-5 scale. The total score for the three questions within each dimension produced a continuous variable ranging from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating a stronger trait in that dimension. The mean scores for the Big Five personality dimensions—conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and emotional stability—were 11.260, 9.866, 11.294, 9.605, and 9.063, respectively. Notably, the average scores for conscientiousness and agreeableness were significantly higher than those for the other traits. Details are provided in Supplementary Material Table S1.

To investigate the mediating role of non-cognitive abilities between LBE and adult happiness, we constructed an overall non-cognitive index using principal component analysis (PCA). Based on eigenvalues greater than 1, two principal components were extracted, with a cumulative variance contribution of 73.1%. The final index was calculated as a weighted sum of these components, using their respective variance contributions as weights.

Family Social Capital. The CFPS 2018 is the sole dataset including variables on relationships with the father, mother, and spousal intimacy, which are used for the mechanism analysis. Of the 4464 total samples, 1488 are from CFPS 2018. After excluding cases of deceased parents, refusal to answer, or inapplicable questions, valid observations are 1332 for father, 1375 for mother, and 1409 for spousal intimacy. Relationships were rated on a 1-to-5 scale, with higher scores indicating closer ties and higher family social capital.

The mean scores reported by respondents were 4.224 for the relationship with their father, 4.383 for the relationship with their mother, and 4.408 for the importance of closeness to their spouse (see Table 1). These results suggest that, on average, respondents experience a high degree of closeness with both their parents and their spouse.

The moderating variable in this study is the kinship network, which represents an important dimension of family social capital. It is measured using the CFPS 2010 baseline question on the number of extended family members within the respondent’s family and is treated as a continuous variable. Since this item is only available in the 2010 wave, the analysis of the moderating association of kinship network is restricted to that wave. After excluding observations with missing values on key variables, the final sample consists of 3845 individuals. In the 2010 data, adult happiness is measured on a 1–5 scale, with higher values indicating greater happiness. As shown in Table 1, respondents report an average of 5.327 extended family members within the respondent’s family.

The control variables include individual characteristics, such as age, gender, marital status, household registration, absolute income, and relative income, as well as family characteristics, including father’s and mother’s years of education, father’s and mother’s occupational prestige, and the number of siblings. Descriptive statistics of control variables are presented in Table 2.

Methodology

This study explores the impact of LBE on adult happiness and assesses whether multidimensional capital serves as a moderating factor. Utilizing a three-period panel dataset with happiness as a continuous dependent variable, we conducted a Hausmann test (p = 0.000) and subsequently employed a fixed-effects model to control for individual heterogeneity and time-invariant characteristics. Additionally, time-fixed effects and province-fixed effects are included in the model.

The empirical model is specified as follows:

where \({{happiness}}_{{ijt}}\) represents the happiness level of residents i in province j at time \(t\), \({{LBE}}_{{ijt}}\) indicates the LBE of residents in the same context, \({X}_{{ijt}}\) denotes control variables, \({u}_{{prov}}\) and \({\lambda }_{t}\) are the fixed effects for province and year, respectively, and \({\varepsilon }_{{ijt}}\) is the random error term.

Results and analysis

LBE and adult happiness

Table 3 presents the regression results, showing the progressive addition of control variables across Columns (1) through (3). In all models, the coefficients for LBE remain negative and statistically significant, supporting the robustness of the findings. Specifically, in Column (3) of Table 3, the results indicate that LBE is associated with a 0.194-point reduction in adult happiness, with statistical significance at the 5% level. The pattern of estimates supports Hypothesis 1a and is consistent with a lasting negative association between LBE and adult happiness.

Although this study focuses on China, similar patterns have been documented in other developing and transitional contexts. In the Philippines, for example, parental migration—especially that of mothers—has been linked to heightened emotional distress and lower academic performance among children (Parreñas 2005). In Mexico and other Latin American countries, children left behind by migrant parents have exhibited long-term declines in subjective well-being and educational attainment (Dreby 2007). More recent research extends this evidence base. Fu et al. (2023, 2025) highlight that parental migration in the Philippines and Indonesia negatively affects children’s psychological well-being, with the timing of migration and the mental health of substitute caregivers playing a critical role. In Bangladesh, Jahan and Khanam (2023) report that parental absence—particularly involving both parents—significantly impairs early childhood development.

In Europe, Račaitė et al. (2024) find that LBC in Lithuania experience higher levels of emotional and behavioral difficulties compared to their peers, with outcomes shaped by gender, living environment, and school engagement. Transnational evidence from Sri Lanka further supports these findings, where Wickramage et al. (2015) observe that 40% of children left behind by international labor migrants show signs of mental health problems, and nearly 30% of children under five are underweight. Antia et al. (2020) similarly find that LBC exhibit elevated levels of depression and loneliness, although the strength and direction of these effects vary by region, culture, and family characteristics. Notably, evidence of adverse outcomes appears particularly strong in studies from South Asia and the Americas.

Heterogeneity analyses of LBE type, age stage and duration

The type of LBE and adult happiness

In Table 4, Column (1) presents the associations between different types of LBE and adult happiness. The findings reveal that the absence of both parents, as well as father-only absence are associated with lower adult happiness. Specifically, the absence of both parents is significant at the 5% level, while father-only absence is significant at the 1% level. Adults who experienced father-only absence report a 0.323-point reduction in happiness compared to the non-LBE group, while adults who experienced the absence of both parents report a 0.388-point reduction in happiness. Point estimates for the mother-only group are positive but statistically indistinguishable from zero. Given the small sample size (n = 18) and limited statistical power, these results are imprecise; therefore, we exclude this category from further substantive discussion.

The observed association between father-only absence and lower adult happiness may reflect multiple underlying mechanisms. First, fathers are often considered important in shaping children’s character (Zhou et al. 2022), and their absence may be associated with less favorable personality development, thereby influencing adulthood outcomes. Second, in traditional Chinese culture, where men often play a dominant role in the public and familial spheres, the absence of a father may reduce children’s exposure to key cultural influences within the family, which could have longer-term implications. Moreover, the absence could limit access to parental care and is consistent with lower reported happiness in adulthood. These findings provide support for Hypothesis1b.

The age stage and duration of LBE and adult happiness

Column (3) reports the associations between different age stages and LBE on adult happiness. The results indicate that being left behind during the 4–12 age stage is statistically significant, as is the experience of being left behind during both the 0–3 and 4–12 age stages. Specifically, adults who were left behind at 4–12 age stage report a 0.196-point reduction in happiness compared to non-LBE group, while those left behind during both age stages report a 0.449-point reduction. The separation from parents during the 4–12 age stage may be associated with greater feelings of loneliness, which could adversely affect psychological development and hinder the establishment of close parental bonds. This pattern shows a comparatively stronger statistical association with lower adult happiness, which may be consistent with the lasting salience of early-life parental absence.

A possible explanation for the greater impact of being left behind during both age stages, compared to only during the 4–12 age stage, may reflect the cumulative consequences of prolonged separation, which could exacerbate adverse outcomes. These findings provide partial support for Hypothesis 1c.

Column (5) examines the associations between the duration of LBE and adult happiness. The results reveal that adults with LBE lasting more than three years exhibit significantly lower levels of happiness, with statistical significance at the 10% level. Specifically, compared to non-LBE group, those with over three years of LBE report a 0.377-point reduction in happiness. Other durations of LBE did not show statistically significant associations, suggesting that longer durations of LBE are associated with lower adult happiness, consistent with a potential “duration effect”. This pattern may be consistent with partial buffering from alternative caregivers and intermittent contact, which could mitigate the negative consequences of short-term LBE. Conversely, LBE lasting more than three years may be linked to greater psychological burdens, which could contribute to feelings of abandonment compared to their peers. Additionally, prolonged separation from parents is also correlated with weaker parent-child bonds and lower reported happiness. These findings are consistent with existing research (Liu et al. 2022) and provide partial support for Hypothesis 1d.

These findings are consistent with and extend prior research. For instance, Liu et al. (2022) documented a significant time-based effect of LBE on adult happiness, particularly highlighting the psychological scars associated with early and prolonged separation. Similarly, Liang and Li (2021) found that dual-parent absence had more detrimental consequences than single-parent absence, which aligns with our results on the disproportionate impact of father-only absence and both parents absent. Han et al. (2023) emphasized that physical and emotional neglect during childhood impaired long-term social functioning, which is echoed in our findings on the mediating role of family social capital. By providing evidence from panel data and causal identification strategies, our study complements and extends prior research, offering additional support for the long-term consequences of LBE.

To address concerns about potential endogeneity, we re-estimated all models for the heterogeneous estimates using an instrumental variable approach. The two-stage least squares (2SLS) results, clustered at the county level, are reported alongside the original OLS estimates for comparison (Table 4). The consistency between the IV and OLS estimates supports the robustness of the results and is consistent with a causal interpretation under the standard IV assumptions.

To address potential endogeneity concerns, we employ Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression alongside Propensity Score Matching (PSM) and Instrumental Variables (IV) techniques to assess the robustness of our findings. The estimation results are presented in the Supplementary Material, Section S1 (Fig. S1; Tables S2 and S3). In addition, we conduct a series of robustness checks—such as replacing the dependent variable, redefining the LBE, and excluding respondents with poor memory—and report the results in the Supplementary Material, Section S2 (Table S4).

Multidimensional capital mediation analysis

Human capital mediation analysis

This section examines the mediating role of human capital from two perspectives: traditional human capital, which includes years of schooling, physical health, mental health, and new human capital, focusing on non-cognitive abilities.

As illustrated on the left side of Fig. 3, the estimated association between LBE and years of schooling is statistically insignificant, suggesting no clear association with the accumulation of educational human capital. One possible explanation for this finding is dual impact of parental migrating on children’s education. On the one hand, remittances sent by migrant parents may improve educational opportunities for LBC (Peng et al. 2022). On the other hand, the absence of parental supervision can hinder academic performance, potentially increasing the likelihood of school dropout due to insufficient oversight (Li et al. 2020). These opposing forces may offset each other, which could help explain the overall insignificant association observed in educational outcomes.

CFPS2018. In the figure, each arrow starts from the independent variable and points to the dependent variable, with the values representing estimated coefficients. 2. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. 3. Education, mental health, and non-cognitive ability are continuous variables, and the impact of childhood left-behind experience on these variables is estimated using OLS regression models. 4. Physical health is a binary variable, estimated using probit regression; the relationships with the father, mother, and spousal intimacy are ordinal variables, estimated using ordered probit regression, with the reported coefficients being average marginal effects. 5. The control variables in each model are consistent with those in Table 2. 6. On the right side of the figure, since adult happiness is a continuous variable, all regressions use OLS.

However, LBE is significantly associated with poorer physical and mental health in adulthood, with both associations statistically significant at the 5% level. This suggests that LBE is negatively associated with the accumulation of health-related human capital. Compared to the non-LBE group, the LBE group is 10.2% less likely to report being in good physical health, and their mental health scores are 0.965 points lower.

One possible explanation is that parental migration may reduce the extent of care children receive in their daily lives. Since childhood is a sensitive period of physical development, inadequate nutrition during this stage may be associated with poorer physical health later in life. Furthermore, the emotional neglect experienced by LBC compared to their peers can have lasting psychological consequences. Caregivers, whether negligent, overly indulgent, or strict, are unable to fully substitute parental care. The absence of parents during early childhood leaves children without emotional support when facing challenges such as school bullying (Chen et al. 2021). If not addressed in time, such adverse experiences may have lasting psychological consequences.

On the right side of Fig. 3, it is shown that years of schooling, physical health, and mental health are all positively associated with adult happiness. Each additional year of schooling is associated with a 0.029-point higher happiness score. Adults in good physical health report happiness scores 0.663 points higher than those in poor physical health. Additionally, for every unit increase in mental health, happiness scores rise by 0.16 points. Combining these findings with the results from the left side of Fig. 3, these results are consistent with the interpretation that physical and mental health may be important pathways linking LBE to adult happiness. While Hypothesis 2a, which proposed that LBE negatively affects the accumulation of educational human capital, is not supported, Hypotheses 2b and 2c were supported by the pattern of estimates.

Figure 3 further shows that LBE is not significantly associated with non-cognitive abilities. However, non-cognitive abilities are positive associated with adult happiness. We find no evidence that non-cognitive abilities mediate the relationship between LBE and adult happiness, and Hypothesis 2d is not supported.

Family social capital mediation analyses

In line with Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c, we examine whether family social capital mediates the association between LBE and adult happiness. As illustrated in Fig. 3, LBE is associated with lower reported closeness with their father, mother, and spouse. Crucially, the findings also show that improvements in these relationships are positively associated with adult happiness.

When parents migrate for work during childhood, children experience a form of separation, often referred to as the “separation effect”. This lack of parental presence and reduced intimacy during childhood may foster emotional distance, which persists into adulthood. Compared to the non-LBE group, those with such experiences report 0.442 units lower level of closeness with their father and 0.367 units lower level of closeness with their mother, respectively. These patterns are consistent with LBE being associated with lower family social capital, particularly in the parent-child relationship. Moreover, the LBE group also reports 0.344 units lower spousal intimacy compared to the non-LBE group, suggesting that LBE may inhibit the development of spousal social capital through the intergenerational transmission of close relationships.

The relationships with the father, mother, and spouse are each positively associated with adult happiness, with coefficients statistically significant. Specifically, a one-unit improvement in the relationship with the father, mother, and spouse is associated with an increase in adult happiness by 0.525, 0.502, and 0.898 points, respectively. Taking both stages into consideration, these findings are consistent with lower family social capital mediating part of the association between LBE and adult happiness. As a result, Hypotheses 3a, 3b and 3c are supported. To address potential endogeneity and enhance the robustness of the results, instrumental variable regressions were conducted. The results are largely consistent with those presented above, and the detailed estimates are provided in Supplementary Material Fig. S2.

In summary, physical and mental health (human capital) and relationships with the father, mother, and spouse (family social capital) emerge as plausible pathways linking LBE to adult happiness. We therefore apply the KHB method in the subsequent analysis to formally decomposes the association.

Karlson–Holm–Breen (KHB) mediation analysis

To investigate the mediating pathways through which LBE may influence adult happiness, we employ the KHB method. Originally developed for nonlinear models such as logit and probit regressions, the KHB approach has been widely applied to linear models for decomposing total effects into direct and indirect components (Karlson et al. 2012). This method allows us to examine the relative contribution of multiple mediators—such as physical and mental health, and family social capital—while controlling for covariates and addressing rescaling bias. The KHB framework is particularly useful for comparing the strength of competing mediators and assessing their significance within a unified model.

Table 5 presents the results of the KHB mediation analysis. The five mediating variables collectively account for 62.34% of the total estimated association, consistent with mediation operating as an important channel linking LBE to adult happiness. Among the mediators, mental health accounts for the largest share of the mediation, contributing 43.45% to the total mediation association. The next largest contributor is the relationship with the father, accounting for 20.12% of the mediating association.

Kinship network moderating analysis

In Model (1) of Table 6, the kinship network is positively associated with adult happiness, indicating that a greater number of direct relatives from the parental side is linked to higher levels of happiness in adulthood. The interaction term between LBE and kinship network is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level, suggesting that stronger kinship networks are associated with a weaker negative relationship between LBE and adult happiness. Specifically, for individuals with strong kinship networks, the adverse association of LBE with happiness is weaker, whereas for those with weak kinship ties, it is more pronounced. These findings are consistent with the compensatory role of the kinship network and align with Hypothesis 3d. In Model (2), IV regressions are employed to address potential endogeneity, and the results remain largely consistent with those obtained from the OLS estimation.

Discussion

The current study, grounded in life course theory and the multidimensional capital accumulation perspective, uses panel data from the CFPS to examine the long-term associations between LBE and adult happiness, and to explore the potential mechanisms. The findings indicate a statistically significant negative association between LBE and individual happiness that appears to extend into adulthood. This is consistent with the view that being left behind in childhood may have lasting implications for adult happiness (Liu et al., 2022). By extending the analysis beyond university students to the broader adult group (Yao and Zhang, 2018), this study provides more comprehensive insights into the scope of LBE’s impact. In particular, the negative association appears stronger in cases of father-only absence or both-parents absence, whereas estimates for mother-only absence are statistically insignificant and imprecise due to the small sample size. This pattern may reflect the important role of fathers in child-rearing and resonates with discussions of “absentee fatherhood” in Chinese society. The absence of fathers during critical developmental stages may be associated with enduring challenges to happiness. Moreover, the association between LBE and reduced happiness is particularly evident when it occurs during the 4–12 age stage, or across both the 0–3 and 4–12 age stages. These findings suggest that the 4-12 age stage represents a sensitive period for the development of subjective well-being. Longer durations of LBE (more than three years) are associated with lower levels of adult happiness, indicating a “duration effect” (Liu et al. 2022).

This study is among the first to examine the mechanisms through which LBE affects adult happiness. Contrary to expectations, educational capital and non-cognitive abilities did not show significant evidence of serving as mediating mechanisms. Although remittances from migrant parents may enhance educational opportunities (Peng et al. 2022), the lack of parental supervision can negatively impact academic performance. Additionally, while parental absence might foster resilience—a form of non-cognitive ability (Liu 2019)—it can also undermine emotional stability (Liu et al. 2021). Future research should further investigate why educational and non-cognitive capital appear less central as mediating mechanisms in this context. Consistent with expectations, physical and mental health were found to mediate the relationship between LBE and adult happiness, with the negative association between LBE and health persisting into adulthood, which in turn is correlated with lower levels of happiness (Gao et al. 2010).

Furthermore, this study also explores the role of family social capital, which more specifically refers to intra-family social capital. The results indicate that LBE weaken parent-child relationships, which in turn reduce adult happiness. Intimacy tends to be transmitted intergenerationally (Bowen 1993). The separation of parents due to migration may be associated with lower spousal intimacy, as children tend to replicate intimacy patterns learned in their family of origin. This pattern is consistent with diminished spousal social capital and lower happiness in adulthood. However, due to data limitations, external social capital could not be assessed, which suggests a potential direction for future research.

Beyond individual-level mechanisms, cultural and social contexts may shape the impact of LBE on adult happiness in important ways. First, the rural–urban divide in China creates vastly different caregiving environments. Children in rural areas often lack access to quality education, healthcare, and emotional support, which exacerbates the adverse consequences associated with parental absence. Second, traditional family roles in China designate mothers as the primary caregivers, which may suggest that maternal absence could have a stronger emotional impact on children. However, this study finds that paternal or dual-parent absence is associated with more significant reductions in adult happiness. One possible explanation is that the father’s absence is often linked to the loss of emotional security, discipline, or financial stability in the household, particularly in rural settings. Moreover, both parents absent creates a substantial caregiving gap, which may disrupt children’s emotional development and contribute to difficulties in later well-being. Third, community structures vary significantly across regions. In China, the provinces with the largest number of LBC—such as Sichuan, Anhui, Henan, Hunan, and Guizhou—are concentrated in the central and western parts of the country. In some of these areas, extended family members and village-based social networks can partially buffer the adverse consequences associated with parental migration. In others, the weakening of traditional communal ties may intensify emotional isolation and vulnerability. Future research should more explicitly incorporate these sociocultural dimensions into empirical analysis to better understand the heterogeneity in LBE outcomes across different regional and cultural contexts.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the sample structure poses constraints. The relatively small number of mother-only absence cases (n = 18) reduces statistical power, making estimates for this subgroup imprecise; we therefore caution against over-interpreting these results. In addition, the sample covers only individuals aged 18–38 years, restricting the analysis to early and middle adulthood. Future longitudinal surveys should extend the tracking window beyond 2020 to capture the long-term implications of LBE for happiness in later life.

Second, the data limit the depth of developmental analysis. Although we examine mediators such as schooling, health, non-cognitive skills, and parent–child relationships, the absence of detailed childhood process data prevents us from fully tracing dynamic developmental trajectories. To ensure cross-wave comparability of the outcome, we deliberately restrict the analysis to the 2014, 2018, and 2020 CFPS waves that use a consistent 0–10 happiness scale; nevertheless, inter-wave contextual changes may still shape the observed associations.

Third, the study relies on retrospective self-reports, which are vulnerable to measurement error. Respondents may recall or interpret past experiences inaccurately. Classical error would attenuate estimated associations, while non-classical error could bias them in unknown directions. Although we mitigate this risk by cross-validating definitions across waves and running robustness checks, residual error cannot be ruled out.

Fourth, unobserved heterogeneity remains a concern. While we employed fixed effects, Propensity Score Matching, and Instrumental Variables to address endogeneity, factors such as caregiving quality, intergenerational dynamics, or community support may still confound the results. Our identification relies on assumptions (e.g., selection on observables for PSM; instrument relevance and exclusion for IV). Although we provide first-stage strength and over-identification tests in the Supplementary Material, a fully causal interpretation should be treated with caution.

Finally, external validity is limited. Structural heterogeneity—by province, urban–rural setting, and caregiving arrangements—may shape both LBE exposure and its consequences, yet our subgroup analyses are constrained by sample sizes in certain cells. Future research should draw on larger, more representative samples and richer contextual data to clarify subgroup-specific associations.

Conclusion

This study investigates the long-term impact of LBE on adult happiness using panel data from the CFPS and a life course theoretical framework. The results show that LBE is consistently associated with lower levels of adult happiness, particularly in cases of father-only absence or absence of both parents, when experienced at ages 4–12, or for durations longer than three years. These findings enrich our understanding of how early disruptions in family structure and caregiving may be linked to outcomes well into adulthood.

This study makes several important contributions. Theoretically, it approaches the concept of LBE through a life course lens and integrates dimensions of human capital and social capital into a broader explanatory framework. This approach advances the literature by identifying how different configurations of LBE influence long-term well-being. Practically, the findings offer policy-relevant insights, especially concerning differentiated risks based on parental migration type and child age at exposure. The identification of key mediating pathways also offers guidance for targeted intervention. Socially, this study addresses the growing need to understand the emotional consequences of large-scale labor migration and points to the importance of designing inclusive family support systems in China’s rural and migrant communities.

Several policy implications follow from these findings. First, the study suggests the importance of promoting greater paternal involvement in childcare and reducing “absentee fatherhood”, through mechanisms such as flexible work schedules, fatherhood education, and financial incentives. Second, the evidence that the 4–12 age stage may represent a sensitive period suggests the value of targeted psychosocial support programs for LBC in schools and communities. Third, localized support systems in rural and high-incidence regions should be expanded through investment in caregiving infrastructure and school-family partnerships. Finally, reforms in migration-related social policies could focus on facilitating family reunification and addressing the long-term caregiving vacuum created by both parents’ migration.

Data availability

The data used in this article can be downloaded from the following website: https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/en/data/public/index.htm

References

All-China Women’s Federation (2013) Research report on the situation of left-behind children in rural China and migrant children in urban-rural areas, http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/0510/c70731-21441584.html (Accessed 1 October 2024)

All-China Women’s Federation Research Group (2013) National research report on left-behind children in rural China. Chin Women’s Movement (6):30–34

Antia K, Boucsein J, Deckert A, Dambach P, Račaitė J, Šurkienė G, Jaenisch T, Horstick O, Winkler V (2020) Effects of international labour migration on the mental health and well-being of left-behind children: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(12):4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124335

Bowen M (1993) Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Jason Aronson. National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) Bulletin of the Seventh National Census (No. 5), https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202302/t20230206_1902005.html, (Accessed 1 October 2024)

Chen J, Wang X, Guo X (2021) The influence of parental absence on school bullying encountered by adolescents in big cities. Youth Stud 2:82–93. 96

Chen F, Liu G (2012) The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. J Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 67(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr132

Coall DA, Hertwig R (2010) Grandparental investment: Past, present, and future. Behav Brain Sci 33(1):1–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X09991105

Coleman J (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:95–120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

Costa PT, Mccrae RR (1992) Four ways five factors are basic. Personal Individ Differences 13(6):653–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

Crowne SS, Juon HS, Ensminger M, Burrell L, McFarlane E, Duggan A (2011) Concurrent and long-term impact of intimate partner violence on employment stability. J Interpers Violence 26(6):1282–1304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510368160

Cui Y, Xu Z (2021) The effect and mechanism of parental migration on non-cognitive abilities of rural left-behind children in China. Zhejiang Academic J 5:125–136

Cunha F, Heckman JJ, Schennacb SM (2010) Estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Econometrica 78(3):883–931. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA6551

Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R (2003) Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 301(5631):386–389. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1083968

Dannefer D (2003) Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 58(6):S327–S337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327

Dreby J (2007) Children and power in Mexican transnational families. J Marriage Fam 69(4):1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00430.x

Duan W, Yu X, Tang X (2023) Humor ABC” program: specific strength intervention in facilitating the positive development of left-behind children. J Happiness Stud 24(4):1605–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00653-3

Duan C, Lü L, Guo J et al. (2013) The basic conditions of survival and development of left-behind children in rural China: an analysis based on the Sixth National Population Census. Popul J 35(3):37–49

Duan C, Yang G (2008) A study on the situation of left-behind children in rural China. Population Res (3):15–25

Elder GH (1994) Time human agency, and social change: perspectives on the life course. Soc Psychol Q 57(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786971

Elder GH (2002) Children of the great depression. Routledge

Erikson EH (1968) Identity youth and crisis (No. 7). WW Norton & Company

Fei X (1998). The fertility system. Peking University Press

Fu Y, Jordan LP, Zhou X, Chow C, Fang L (2023) Longitudinal associations between parental migration and children’s psychological well-being in Southeast Asia: The roles of caregivers’ mental health and caregiving quality. Soc Sci Med 320(1982):115701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115701

Fu Y, Asis MMB, Sukamdi Zhou X, Jordan LP (2025) A life course approach to examine cumulative impacts of parental migration on children’s psychological well-being and education in Southeast Asia. Developmental Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001879

Gao Y, Li LP, Kim JH, Congdon N, Lau J, Griffiths S (2010) The impact of parental migration on health status and health behaviors among left behind adolescent school children in China. BMC Public Health 10:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-56

Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, Goff B, Humphreys KL, Telzer EH, Hare TA, Bookheimer SY, Tottenham N (2013) Early developmental emergence of human amygdala–prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(39):15638–15643. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1307893110

Goode WJ (1986) The family (Z. Wei, Trans.). Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing (Original work published 1963)

Guo Y (2020) The Impacts of left-behind experience and its initial stage on college students’ noncognitive ability. Youth Studies 1, 12-23+94

Heckman JJ (2000) Policies to foster human capital. Res Econ 54(1):3–56. https://doi.org/10.1006/reec.1999.0225

Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24(3):411–482. https://doi.org/10.1086/504455

Heckman JJ (2019) A Dynamic Model of Health, Addiction, Education, and Wealth. the 2019 China Meeting of the Econometric Society, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. https://iesr.jnu.edu.cn/2019/0813/c17414a400995/page.psp

Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs J, De Neve J-E, Huang H, Wang S (2025) World Happiness Report 2025. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. https://worldhappiness.report/

Hao Z, Cui L (2007) A discussion on the criteria for defining left-behind children. China Youth Study (10):40–43

Han B, Wang S, Zhang J (2023) The impact of left-behind experience on rural children’s educational attainment in adulthood: The mediating effect of non-cognitive ability. Educ Econ 39(2):87–96

Karim J, Weisz R, Bibi Z (2015) Validation of the eight-item center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) among older adults. Curr Psychol 34(4):681–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9281-y

Karlson KB, Holm A, Breen R (2012) Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: a new method. Sociol. Methodol 42(1):286–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175012444861

Khanam SJ, Khan MN (2023) Effects of parental migration on early childhood development of left-behind children in Bangladesh: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. PLoS ONE 18(11):e0287828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287828

Li Q, Ye Y, Jiang T (2020) A study of the impact of parental absence on school dropout among rural left-behind children. Rural Econ 450(04):125–133 (in Chinese)

Li Q, Zang W (2011) The health of left behind children in rural China. China Economic Rev 10(01):341–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2015.04.004

Li Y, Luo P, Tan Y (2008) An investigation into the mental toughness of abandoned youngsters in rural places. J Henan Univ (Soc Sci) 01:13–18 (in Chinese)

Li Y, Wang J, Luo L (2019) Parental migration and children’s subjective well-being: evidence from rural China. China Economic Stud 01:66–79. https://doi.org/10.19365/j.issn1000-4181.2019.01.06

Li Y (2013) Self-selection, migration, and children educational performance: evidence from an under developed province in rural China. China Economic Q 12(3):1027–1050

Liang Z, Li W (2021) Left-behind experience and educational development of rural children. Educ Sci 37(3):8–18 (in Chinese)

Liu Z (2019) Left-behind experience and mental health—an empirical study of migrant workers burn after 1980. J China Agric Univ (Soc Sci) 36(1):111–127

Liu Z, Xu F (2020) Left-behind experience and social dysfunction—an empirical study of new-generation migrant workers. Chin J Soc Dev 7(3):61–78. 243

Liu Z, Yang S, Wang Y (2022) Window of time and trauma of time: the temporal effect of left-behind experience on subjective well-being. Society 42(6):188–213

Liu H, Chang F, Corn H, Zhang Y, Shi Y (2021) The impact of parental migration on non-cognitive abilities of left-behind children in northwestern China. J Asian Econ 72:101261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2020.101261

Liu Z (2008) A critical review and estimation of the definition and scale of left-behind children. J Guangxi Univ Nationalities (Philos Soc Sci Ed) 3:49–55

Liu Z, Yu L, Zheng X (2018) Longer left-behind: the impact of return migrant parents on children’s Performance. China Economic Rev 49:184–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.06.004

Lu J (2011) Emotional life loss of left-behind children: social price on the way to industrialization in China. J China Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 28(3):97–103

Luby J, Belden A, Botteron K, Marrus N, Harms MP, Babb C, Nishino T, Barch DM (2013) The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: The mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatrics 167(12):1135–1142. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139

Meng X, Yamauchi C (2017) Children of migrants: the cumulative impact of parental migration on children’s education and health outcomes in China. Demography 54(5):1677–1714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0613-z

Metzler M, Merrick MT, Klevens J, Ports KA, Ford DC (2017) Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: shifting the narrative. Child Youth Serv Rev 72:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021

Milardo RM (2010) The forgotten kin: aunts and uncles. Cambridge University Press

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) Bulletin of the Seventh National Census (No.5), https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202302/t20230206_1902005.html, accessed 1-10-2024

Peng X, Fu Y, Shi Q (2022) The impact and mechanism of migrant workers’ remittances on educational performance of left-behind children in rural areas: an empirical analysis based on CFPS data. China Rural Surv 5:168–184

Parreñas RS (2005) Children of global migration: transnational families and gendered woes. Stanford University Press

Parsons T (1943) The kinship system of the contemporary United States. Am Anthropologist 45(1):22–38. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1943.45.1.02a00030

Qiu H, Zhang L (2021) Gender difference of chinese youth education and its influence on subjective well-being. Popul J 43(6):85–93

Račaitė J, Antia K, Winkler V, Lesinskienė S, Sketerskienė R, Maceinaitė R, Tracevskytė I, Dambrauskaitė E, Šurkienė G (2024) Emotional and behavioural problems of left behind children in Lithuania: a comparative analysis of youth self-reports and parent/caregiver reports using ASEBA. Child Adolesc psychiatry Ment health 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00726-y

Rotter JB (1966) Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr 80(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0092976

Schultz TP (1990) Testing the neoclassical model of family labor supply and fertility. J Human Resources 599–634. https://doi.org/10.2307/145669

Song J, Zhang Y, Wang J (2014) Family types and family well-being: the case of Beijing. Popul Res 38(5):17–26 (in Chinese)

Sun L, Liu L (2020) Does education affect the subjective well-being of the elderly? An empirical study based on the rate of return to investment in education. Open Educ Res 26(5):111–120

Sun W, Wang Y (2016) The impact of parental migration on left-behind children’s health: a re-examination based on micro panel data. China Economic Q 3:963–988

Thompson RA (2008) Early attachment and later development: familiar questions New Answers. The Guilford Press

Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R (1999) A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 11(2):139–148. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610299005694

Tan S (2011) A literature review of research on rural left-behind children in China. Social Sci. China (1):138–150

Tang C (2010) A review and evaluation of the theory of family modernization and its development. Sociol Res (3):145–166

United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 1. United Nations Treaty Series, 1577, 3

Van Dam NT, Earleywine M (2011) Validation of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale—revised (CESD-R): Pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res 186(1):128–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018

Wang M, Dai X, Yao S (2010) Development of Chinese big five personality lnventory (CBF -PI): theoretical framework and reliability analysis. Chin J Clin Psychol 18(5):545–548

Wei D, Chen X (2018) Settlement threshold, skill bias and left-behind children: an empirical study on monitoring date of Chinese domestic migrants in 2014. China Economic Q 17(2):549–578

Wickramage K, Siriwardhana C, Vidanapathirana P, Weerawarna S, Jayasekara B, Pannala G, Adikari A, Jayaweera K, Peiris S, Siribaddana S, Sumathipala A (2015) Risk of mental health and nutritional problems for left-behind children of international labor migrants. BMC Psychiatry 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0412-2

Wu Y, Wang P, Du S (2018) China’s changing family structure and adolescent development. Soc Sci China 2:98–120. 206-207

Xu Z, Jin G, Zhang X, Geng Y (2013) An empirical analysis of factors affecting rural residents’ sense of happiness—Based on the comparison between the stricken area and non-stricken area after the earthquake in Sichuan Province. China Rural Surv (4):72-85+96

Yao Y, Zhang S (2018) The last “soul imprint”: how the left-behind duration influence the youth’s early subjective well-being. Youth Stud 3:23–33. 94-95

Ye J, Lu P (2011) Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J Peasant Stud 38(2):355–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.559012

Ye J (2019) Studies on rural left-behind population: general position, some misunderstandings and new theoretical perspectives. Popul Res 43(2):21–31

Yuan S, Xing Z (2017) On the relationship between left-at-home rural children’s social welfare and subjective well-being. Chin J Spec Educ 9:9–14

Zhang C, Xu W (2020) Left-behind experience and aggression in college students: the mediating role of sense of security and inferiority. Chin J Clin Psychol 28(1):173–177