Abstract

In Europe, allonormative beliefs are common. These beliefs assume that all people desire sexual activity with others. Individuals who are single or asexual differ from these norms and may face social disapproval, including discrimination. The present study investigated whether individuals’ benevolent intentions and behaviors toward a new co-worker vary depending on the co-worker’s sexual orientation (specifically being asexual) and relationship status (specifically being single). A total of 1028 participants (50.0 percent cisgender women and 50.0 percent cisgender men; 78.3 percent heterosexual and 21.7 percent sexual minority participants; mean age 29.2 years, standard deviation 8.8) living in German-speaking countries in Europe each read one of 18 fictional scenarios describing the introduction of a new co-worker. The scenarios varied by the co-worker’s gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status. After reading the scenario, participants indicated how likely they would be to share information with, befriend, gossip about, or show interest in supporting the co-worker’s success. A multivariate analysis of covariance was conducted while controlling for participants’ allonormative beliefs, age, relationship status, nationality, sexual orientation, education, and occupation. The results showed that female participants were less likely to share knowledge with a person who was single by circumstance than with a person in a relationship. Male participants were more likely to befriend a single-by-choice gay man than a gay man who was in a relationship. These findings highlight bias against single individuals in workplace-related contexts. The results can help raise awareness of subtle prejudices based on sexual orientation and relationship status. Recognizing these biases is an important first step in developing interventions to reduce discrimination in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In North America and Europe, the belief that all people are inevitably attracted to and desire sexual activity with others is widespread. This belief is referred to as allonormativity (Brandley and Dehnert 2024). Individuals who do not conform to such social expectations are at risk of experiencing social disapproval. People who violate social norms may face stigmatization, meaning they are labeled and associated with negative attributions and stereotypes, resulting in lower social status or reduced power (Pescosolido and Martin 2015). Individuals who are different to norms may also become targets of discrimination, which involves unequal treatment that disadvantages the person (Scherr and Breit 2018). Asexual and aromantic individuals, defined as people who experience little or no sexual and/or romantic attraction toward others (Moser and Hinderliter 2015), as well as single individuals, may face devaluation, stigmatization, or discrimination (Komlenac and Hochleitner 2023).

In a recent vignette study (Finch 1987; Wallander 2009), participants from the United States and the United Kingdom read descriptions of either a heterosexual or an asexual fictional character (Zivony and Reggev 2023). The asexual character was judged to be less social than the heterosexual character. Moreover, participants who strongly believed that sexual attraction is a necessary part of adulthood were less likely to express an intention to befriend the asexual character compared to participants who did not hold allonormative beliefs.

The present vignette study builds on prior research by focusing not on attitudes toward asexual individuals, but specifically behavioral intentions that reflect social rejection or unfavorable treatment in a workplace setting. This study expands the existing literature by including a third condition in which the fictional character is described as gay or lesbian. This design allows for the comparison of responses to asexual characters versus those who belong to a sexual minority group, helping to determine whether rejection is due to asexuality specifically or to minority sexual orientation more generally (Zivony and Reggev 2023). Another novel aspect of the present study is the inclusion of variations in the character’s relationship status. This enables the investigation of the intersection between sexual orientation and relationship status in shaping favorable or unfavorable treatment in a professional context (Wyatt et al. 2022).

Literature Review

Heteronormativity

According to heteronormative ideas about sexuality, people are expected to be attracted to and engage in sexual activity only with individuals of a different gender (Marchia and Sommer, 2019). As a result, individuals who are not attracted to persons of a different gender deviate from these norms and often face devaluation, stigmatization, or discrimination (Meyer 2003, 2013). Sexual minority individuals frequently encounter subtle forms of discrimination, referred to as microaggressions. These microaggressions are not always intentional but can take the form of unintentional communications of disapproval and social rejection (Marchi et al. 2024). Before such microaggressions can be addressed, the individuals who communicate this subtle or unintentional disapproval need to become aware of their behavior (Warner et al. 2020). The present study may help foster such awareness.

In addition, compared to heterosexual individuals, sexual minority individuals often receive fewer social signals indicating inclusion, acceptance, or social security (Diamond and Alley 2022). Experiences of discrimination, being targeted by microaggressions, and receiving signs of disapproval are all risk factors for poor psychological or physical health, according to the minority stress model (Borgogna et al. 2025; Cardoso et al. 2023; Meyer 1995). Therefore, identifying these patterns of treatment is important for the development of interventions aimed at improving workplace conditions for sexual minority individuals (Gould et al. 2025).

A central assumption of heteronormativity is the belief that all people are attracted to and desire sexual activity with others. This belief is referred to as allonormativity (Brandley and Spencer 2023). Allonormative beliefs emphasize that engaging in partnered sexual activity is essential for individual happiness and well-being (Brandley and Spencer 2023).

Individuals who do not meet allonormative expectations, including asexual and aromantic individuals as well as single individuals, are at risk of social exclusion, bullying, disaffirmation, and invalidation (Brandley and Dehnert 2024; Zivony and Reggev 2023). Moreover, allonormative expectations often differ for women and men. Sexual double standards, which involve different norms and expectations based on gender, place greater pressure on women to be in a committed relationship compared to men (Apostolou et al. 2023; Endendijk et al. 2020; Gui 2020; Kahalon et al. 2019; Kislev and Marsh 2023). In a qualitative study from the United Kingdom, single women reported that conversations about their relationship status were often avoided or cut short (Gilchrist 2023). Many women also felt that being in a committed sexual relationship was tied to their sense of femininity. As a result, not being in such a relationship and not having children was often perceived as failing to meet societal expectations of femininity (Gilchrist 2023).

Asexual persons

Asexual individuals experience little or no sexual attraction toward others. Aromantic individuals do not experience romantic attraction toward others (Bogaert 2015; Moser and Hinderliter 2015). Asexuality can be understood as an umbrella term that encompasses a spectrum of identities. These identities range from having no need for romantic or sexual attraction or intimacy to having selective or situational desires for particular aspects of intimacy (Higginbottom 2024). Asexual individuals often perceive societal pressure to exhibit sexual interest and desire. As a result, they may experience exclusion or marginalization. This can take the form of being “othered,” meaning being perceived as not belonging, or “dehumanized,” meaning being viewed as lacking fundamental human qualities (Brandley and Dehnert 2024; Higginbottom 2024).

Allonormative beliefs have been linked to anti-asexual bias (Vu et al. 2022). In a study conducted with Australian undergraduate psychology students, those who strongly endorsed allonormative beliefs reported feeling less confident and more uncomfortable about the idea of working with asexual clients in the future. These students also expressed greater safety concerns (Vu et al. 2022). Similarly, in a vignette-based study, participants demonstrated anti-asexual bias by being less willing to befriend a character identified as asexual (Zivony and Reggev 2023). Stereotypes that depict asexual individuals as immature or non-social may influence others’ willingness to interact with them (Brandley and Dehnert 2024).

The present study extends previous research on anti-asexual bias by examining a broader set of workplace-relevant behaviors. These include both positive behaviors such as knowledge-sharing (Bock et al. 2005), and showing interest in supporting the other person’s success (Gerbasi and Prentice 2013), as well as negative behaviors such as gossiping or spreading rumors. The study also assesses the intention to befriend an asexual co-worker (Zivony and Reggev 2023). Gaining insight into subtle or unintentional bias against asexual individuals is important for raising awareness, encouraging self-reflection, and developing interventions to reduce discrimination in the workplace (Chaudoir et al. 2017; Lesiak 2023; Möller et al. 2024).

Single persons

Single individuals are those who perceive themselves as not being involved in a romantic and/or sexual relationship (Beckmeyer and Jamison 2023; Fitzpatrick 2023; Kislev 2024). These individuals may or may not engage in casual, sexual, or intimate interactions with others (Beckmeyer and Jamison 2023). Some people are single by choice, meaning they have consciously decided to remain single. Others are single by circumstance, meaning they are not currently in a romantic or sexual relationship but may desire or actively seek one (Kislev 2024).

DePaulo and Morris (2005) brought attention to the stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination faced by single individuals in the United States. The term singlism describes the rejection, stigmatization, or discrimination that single individuals face as a result of their singlehood (DePaulo 2023; DePaulo and Morris 2005). In societies that uphold allonormative beliefs, such as those in Europe and North America, laws and policies related to pensions, inheritance, housing, and welfare benefits often privilege couples over single individuals (DePaulo 2023).

Stereotypes about single individuals include beliefs that they are more miserable, lonelier, less warm, and less caring than people in relationships (DePaulo and Morris 2006; Greitemeyer 2009; Hertel et al. 2007). In a recent vignette study conducted among German-speaking adults, participants perceived single individuals as having lower levels of life satisfaction and as being less socially and sexually fulfilled than individuals in relationships (Komlenac et al. 2025). Other stereotypes portray single individuals, especially those who are single by choice, as narcissistic, manipulative, awkward, untrustworthy, or antisocial (Beckmeyer and Jamison 2023; Dupuis and Girme 2024; Slonim et al. 2015).

Because the stereotypes about single individuals often involve socially undesirable traits, people may be less inclined to interact with single persons. This includes being less willing to provide support, share information, or initiate friendships. The present study examined whether participants’ willingness to help, befriend, or support a new co-worker varied based on the co-worker’s relationship status. The study also controlled for participants’ explicit beliefs about singlehood (Pignotti and Abell 2009).

Intersection

Being single or identifying as asexual stands in contrast to heteronormative expectations (Marchia and Sommer 2019). As a result, both groups may experience overlapping forms of marginalization that arise from similar sources of bias (Lavender-Stott 2023). However, stereotypes and expectations may differ based on sexual orientation, leading to distinct forms of discrimination or exclusion depending on a person’s identity (Javaid 2021). For example, gay men are sometimes stereotyped as being highly sexually active or having many partners (Beam and Wellman 2024). Thus, gay men who are single may encounter different forms of discrimination compared to single men of other sexual orientations (Kislev and Marsh 2023).

At the same time, individuals may face “double jeopardy” if they belong to more than one marginalized group (Berdahl and Moore 2006). For instance, a vignette study found that female participants were more likely to socially distance themselves from a lesbian woman who was single than from a lesbian woman in a relationship (Cook and Cottrell 2024).

To account for the complexity of identity-based experiences, the present study considered the intersection of sexual orientation and relationship status, as well as the gender of both the participant and the fictional character described in the vignette. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of how different social identities influence perceptions and behaviors in a workplace context (Kislev and Marsh 2023).

The Present Study

The present vignette study examined whether adults treat asexual and/or single individuals less favorably than heterosexual and/or coupled individuals in a fictional workplace context. The study contributes to the existing literature by adopting an intersectional approach to investigating discrimination against single individuals (Kislev and Marsh 2023). Given the well-established associations between allonormative beliefs and the unfavorable treatment of both asexual and single individuals (Brandley and Dehnert 2024; Zivony and Reggev 2023), the study included allonormative beliefs as a control variable (Pignotti and Abell 2009) and tested the following hypotheses:

H1: Participants will treat single individuals less favorably in a workplace context than individuals in relationships. This includes being less willing to share information, befriend the person, help them achieve occupational goals, and being more inclined to engage in gossip or idle talk.

H2: Asexual individuals will be treated less favorably than heterosexual individuals.

H3: The difference in treatment based on relationship status or sexual orientation will vary depending on whether the character is described as a woman or a man.

Method

Measures

Sociodemographic Information

Participants reported their age in years using a free-text response. Additional sociodemographic variables were assessed using self-constructed questions on gender identity (Fraser 2018), sexual orientation (identity label) (Young and Bond 2023), relationship status, highest level of education, employment, and nationality (Table 1).

Working situation

Participants were presented with one of 18 fictional workplace scenarios adapted from Bos et al. (2007). Participants were asked to imagine that their company had merged with another, and a new co-worker named Toni would be joining their team. Toni’s gender (woman or man), sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay or lesbian, or asexual), and relationship status (single by choice, single by circumstance, or in a committed relationship) were varied systematically. Participants were randomly assigned to one scenario, resulting in an approximately equal distribution across conditions (Table 1). The exact wording of all scenarios, including the original German-language versions, is available in Supplementary Material (S1) and the scenario in which Toni is a heterosexual man who is single-by-choice read:

Imagine you are working for the company Gruber GmbH. Due to the current economic situation, the rival company Maier & Co has merged with your company. As a result, you now have to work with a new male co-worker named Toni. To be able to achieve your future work goals, successful cooperation with your new co-worker is essential. Both companies organize a joint summer party so that all new co-workers can get to know each other better. The atmosphere at the summer party is very exuberant and you talk with Toni. You think Toni is quite a nice person, but you also realize that you find Toni sexually unattractive. In the relaxed and laid-back atmosphere Toni reveals quite a bit about themselves. In addition to talking about hobbies such as cooking and cycling, Toni also tells you that they once hit a parked car and then fled without reporting the damage or leaving contact information. Toni also told you about their private life such as living as a gay man who is single but wants a serious relationship (emphasis added, indicating variable parts of the scenario).

To assess attention and comprehension, participants were asked to recall the character’s relationship status(1 = single, 2 = open relationship, 3 = serious relationship), sexual orientation (1 = heterosexual, 2 = gay/lesbian, 3 = bisexual, 4 = pansexual, 5 = asexual), or gender (1 = man, 2 = woman, 3 = no gender, 4 = non-binary). and the name of the fictional company. Participants could also respond that they did not know the answer. Those who answered any of these questions incorrectly or indicated they did not know were excluded from the analyses (Curran 2016; Ward and Meade 2023).

Allonormative beliefs

Participants’ beliefs regarding the superiority of marriage over singlehood were measured using the corresponding subscale of the Negative Stereotyping of Single Persons Scale (Pignotti and Abell 2009). The ten-item scale includes statements such as “It’s only natural for people to get married,” rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 7 = completely agree). Higher mean scores indicate stronger allonormative beliefs. The reported internal consistency of the scale was α = 0.87 (Pignotti and Abell 2009). The items were translated from English to German with the back-translation method by two independent professional translators (Brislin 1970). The German-language version had reliabilities higher than. 84 (Table 2).

Intention to share knowledge

Participants’ intention to share helpful knowledge with the scenario’s character was assessed using five statements from the Intention to Share Knowledge Scale (Bock et al. 2005). An example item is, “I intend to share my experience or know-how from work with other organizational members more frequently in the future.” Participants indicated the likelihood of engaging in these behaviors using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 5 (extremely likely). Higher mean scores indicated stronger intentions to share knowledge. The original scale had an internal consistency of α = 0.93 (Bock et al. 2005). For the present study, all statements were adapted to refer specifically to the character described in the scenario. For instance, “other organizational members” was replaced with “Toni.” In addition, any phrasing that implied a change in frequency of behavior, such as “more frequently,” was removed to align with the hypothetical nature of the scenario (e.g., “I intend to share my experience or know-how from work with Toni frequently in the future”). Items were translated into German using the back-translation method (Brislin 1970). The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.87 (Table 2).

Gossip

Participants were asked to indicate how often they thought they would engage in idle talk or spread rumors or personal information about Toni using the four items from the gossip subscale of the Uncivil Workplace Behavior Questionnaire (Martin and Hine 2005). Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (many times). Higher mean scores indicated stronger intentions to gossip. The original scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a reliability of α = 0.84 (Martin and Hine 2005). For the present study, items were translated into German using the back-translation method (Brislin 1970) and adapted to the scenario. For instance, possessive terms such as “your” were replaced with “Toni’s.” The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.70 (Table 2).

Friendship Intentions

To assess participants’ intention to become friends with the scenario’s character, six items were drawn from three prior studies (Furman and Buhrmester 2009; Kononov and Ein-Gar 2023; Zivony and Reggev 2023). An example item is, “How much would you wish to be friends with Toni?” Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Higher mean scores indicated stronger intentions to befriend Toni. The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.89 or higher (Table 2). All items used to measure friendship intentions can be found in Supplemental Material S2.

Other-interest

Participants’ probable pursuit of gains for the scenario’s character in socially valued domains, including occupational goals, was measured using the other-interest subscale of the Self- and Other-Interest Inventory (Gerbasi and Prentice 2013). Participants indicated their agreement with nine statements, such as “I want to help people I know to do well,” using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher mean scores reflected stronger other-interest. The other-interest subscale demonstrated strong internal consistency in the original validation, with a reliability of α = 0.91 (Gerbasi and Prentice 2013). All statements were translated into German using the back-translation method (Brislin 1970). For the purpose of this study, the items were adapted to refer specifically to the scenario’s character by replacing references to “my acquaintances” with “Toni.” The internal consistency in the present sample was α = 0.91 or higher (Table 2).

Procedure

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013) and APA standards (APA 2002). The study was exempt from formal review by the local ethics board under Austrian law (“Federal Act on the Organisation of Universities and their Studies (Universitätsgesetz 2002 – UG)”, 2002; “Hospitals and Health Resorts Act (Bundesgesetz über Krankenanstalten und Kuranstalten - KAKuG)”, 2016) and was confirmed exempt on January 27, 2022. Recruitment occurred from October to November 2023 via Prolific Academic (London, UK) (Chandler and Shapiro 2016; Gleibs 2017) and through social media posts on the first author’s private Facebook and Instagram accounts (Stokes et al. 2019). Prolific participants were required to be at least 18 years old and located in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland. To achieve gender balance, 600 women and 600 men were recruited. Participants received £1.60 for approximately 9 min of participation (SD = 3.4).

The questionnaire was administered using SoSci Survey (SoSci Survey GmbH, Munich, Germany). Participants provided informed consent by agreeing to data storage and use for research purposes.

Of the 1272 individuals who entered the survey, 11 were excluded for being underage or not reporting their age. An additional 199 were excluded due to incorrect responses to attention check items. Gender minority participants (n = 34, 3.2%) were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient statistical power for subgroup comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) as well as correlations between continuous variables were calculated. None of the variables showed substantial violations of the assumption of normal distribution, with skewness values ranging from −0.7 to 1.7 and kurtosis values ranging from −0.8 to 4.0 (Weston and Gore 2006). Levene’s tests of homogeneity of error variance were non-significant for all dependent variables (p ≥ 0.237), except for the variable gossip (p = 0.033) (Field 2009).

A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted. The dependent variables included intention to share knowledge, gossip, friendship intentions, and other-interest. The independent variables were the gender of the participant, the gender of the character, the character’s relationship status, and the character’s sexual orientation. In addition, the following covariates were included in the analysis: participants’ allonormative beliefs, age, relationship status, nationality, sexual orientation, education, and occupation. Pillai’s trace was used to assess multivariate effects. Results were considered statistically significant at p-values less than 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Participants

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Of the 1028 participants, half identified as women and half as men. Most participants identified as heterosexual, were in a relationship, and held the nationality of a German-speaking country. Nearly half of the sample reported having a university degree, and approximately half were employed. The majority of participants were recruited via Prolific Academic (Prolific, London, UK).

Descriptive statistics

Most participants indicated a strong likelihood of sharing knowledge with the character described in the vignette (see Table 2) and reported a low likelihood of speaking negatively about the character. The average scores for friendship intentions and other-interest in the character were near the midpoint of the respective scales. On average, participants did not endorse allonormative beliefs (Table 2).

Bivariate correlations between variables are presented in Table 3. Participants who expressed stronger intentions to share knowledge also reported stronger friendship intentions and other-interest in the character, and were less likely to express intentions to gossip. Compared to heterosexual characters, gay or lesbian characters were more likely to elicit intentions to share knowledge, befriend the character, and support the character’s success. Female participants reported higher friendship intentions than male participants. Older participants were less likely to gossip about the character, whereas participants with a nationality other than that of a German-speaking country were more likely to express intentions to gossip. Additionally, sexual minority participants were more likely than heterosexual participants to indicate an intention to gossip about the character (Table 3).

Participant’s gender, character’s gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status

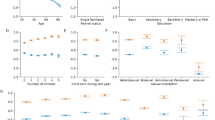

The MANCOVA indicated that participant gender, participant sexual orientation, and several interactions were significantly associated with participants’ intentions toward the character. Specifically, the following interactions were significant: Gender of participant × Relationship status of character, Gender of participant × Sexual orientation of character, Gender of participant × Gender of character × Sexual orientation of character, and Gender of participant × Relationship status of character × Sexual orientation of character (Table 4).

Follow-up ANCOVAs showed that none of the investigated variables were significantly associated with participants’ intentions to speak negatively about the character (Table 5).

Intentions to share knowledge

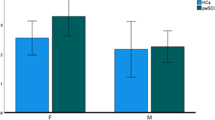

Participants’ gender, the character’s gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status were associated with participants’ intentions to share knowledge (Table 5). Female participants were less likely to intend to share knowledge with characters who were single by circumstance (M = 3.8, SE = 0.1) compared to those in a committed relationship (M = 4.0, SE = 0.1; mean difference = −0.2, SE = 0.1, p = 0.007)Footnote 1 (Fig. 1).

Male participants were more willing to share knowledge with lesbian female characters (M = 4.2, SE = 0.1) than with heterosexual female characters (M = 3.9, SE = 0.1; mean difference = −0.3, SE = 0.1, p = 0.013). Female participants were more willing to share knowledge with gay male characters (M = 4.0, SE = 0.1) and asexual male characters (M = 4.0, SE = 0.1) than with heterosexual male characters (M = 3.8, SE = 0.1; mean differences = −0.2, SEs = 0.1, ps = 0.036 –0.039).

Friendship intentions

Participants’ gender, the character’s gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status were associated with participants’ friendship intentions (Table 5). Participants were more likely to want to befriend gay or lesbian characters (M = 2.8, SE = 0.0) than heterosexual characters (M = 2.6, SE = 0.0; mean difference = -0.2, SE = 0.1, p = 0.002).

This pattern was primarily driven by female participants. Among women, friendship intentions were higher for gay or lesbian characters (M = 2.8, SE = 0.1) compared to heterosexual characters (M = 2.6, SE = 0.1; mean difference = −0.3, SE = 0.1, p < 0.001). Female participants were also more willing to befriend asexual characters than heterosexual ones (mean difference = -0.2, SE = 0.1, p = 0.011).

A significant three-way interaction indicated that this preference for sexual minority characters among female participants was present only when the character was male. Specifically, female participants reported higher friendship intentions for gay male characters (M = 2.9, SE = 0.1) and asexual male characters (M = 2.8, SE = 0.1) compared to heterosexual male characters (M = 2.3, SE = 0.1; mean differences = −0.6 to −0.4, SEs = 0.1, ps = 0.001 to <0.001). This pattern was not observed when the character was female; friendship intentions did not differ by the character’s sexual orientation (all Ms = 2.8, SEs = 0.1; mean differences = −0.1, ps > 0.588).

Additionally, male participants were more likely to befriend a gay man who was single by choice (M = 3.0, SE = 0.1) than a gay man who was in a relationship (M = 2.5, SE = 0.1; mean difference = −0.3, SE = 0.1, p = 0.038).

Other-Interests

Participants’ gender and the character’s sexual orientation were associated with reported other-interest (Table 5). Participants expressed more other-interest in gay or lesbian characters (M = 4.3, SE = 0.1) and asexual characters (M = 4.2, SE = 0.1) than in heterosexual characters (M = 4.0, SE = 0.1; mean differences = −0.3 to 0.2, SE = 0.1, ps = 0.011 to <0.001).

This relationship was strongest among female participants. Women expressed more other-interest in gay or lesbian characters (M = 4.3, SE = 0.1) and asexual characters (M = 4.3, SE = 0.1) than in heterosexual characters (M = 4.0, SE = 0.1; mean differences = −0.4, SE = 0.1, ps = 0.001 to <0.001).

Male participants also showed greater other-interest in gay or lesbian characters (M = 4.3, SE = 0.1) compared to heterosexual characters (M = 4.1, SE = 0.1; mean difference = –0.2, SE = 0.1, ps = 0.001 to 0.037)Footnote 2.

Discussion

In the present study, one hypothesis, namely that participants less often intended to share knowledge with persons who were single by circumstance than with persons in relationships, was supported in women (H1; Fig. 1). In contrast to expectations, some asexual characters were treated more favorably by some participants than were heterosexual characters (H2). Namely, mostly female participants were more likely to share knowledge, befriend, or have other-interests in sexual minority men than in heterosexual men (H3).

Findings consistent with the hypotheses

Although participants overall did not endorse allonormative beliefs, meaning they did not believe that happiness necessarily depends on being in a relationship, they may still hold gendered expectations shaped by societal norms. Previous research has shown that women experience stronger social pressure than men to enter and maintain committed relationships (Apostolou et al. 2023; Endendijk et al. 2020; Gui 2020; Kahalon et al. 2019; Kislev and Marsh 2023).

This pressure may contribute to internalized stereotypes that depict single individuals in a negative light. These stereotypes include assumptions that single people are narcissistic, untrustworthy, or socially withdrawn (Beckmeyer and Jamison 2023; Dupuis and Girme 2024). Previous research has shown that women experience stronger social pressure than men to enter and maintain committed relationships (Apostolou et al. 2023; Endendijk et al. 2020; Gui 2020; Kahalon et al. 2019; Kislev and Marsh 2023). As a result, women may be more likely than men to hold these stereotypes about single individuals. In the present study, female participants may have been less inclined to share knowledge with single individuals because such stereotypes might have led them to expect a lower level of reciprocity from those individuals.

Being excluded from the sharing of useful knowledge can be stressful because it may reduce the experience of social safety cues. These cues include indicators of social connection, inclusion, and acceptance (Diamond and Alley 2022). Even though such exclusion may appear small in scope, these types of behaviors, often referred to as micro-practices or microaggressions, can be harmful. Over time and across different situations, the accumulation of such small acts may contribute to meaningful disadvantages for the individuals affected (Diamond and Alley 2022; Liang et al. 2019).

Recognizing and being aware of subtle or unintentional bias against single individuals in the workplace is an important step in helping people reflect on their own biases and in developing interventions to reduce discrimination against single individuals in organizational contexts (Chaudoir et al. 2017; Lesiak 2023; Möller et al. 2024). Once individuals become aware of their existing biases (Gould et al. 2025), workplace interventions aimed at addressing allonormative beliefs can support the exploration of underlying assumptions and emotional responses (Gupta 2017). Such interventions can also promote the development of clear rules and policies to counteract bias. The present study contributes to these efforts by uncovering subtle forms of bias against single individuals within organizations. In doing so, it supports progress toward the achievement of several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 5 on gender equality, Goal 10 on reducing inequalities, and Goal 16 on promoting peace, justice, and strong institutions (United Nations, n.d.).

Alternative findings

In the present study, women and men were more likely to share knowledge with and show other-interest in sexual minority individuals of another gender. These individuals were potentially not sexually interested in the participants. Additionally, women were more likely to befriend a sexual minority man than a heterosexual man. This finding is consistent with prior research, which has shown that women tend to feel more comfortable around gay men and are more likely to form friendships with them (Russell et al. 2018; Russell et al. 2017; Semenyna and Vasey 2021). One explanation for this pattern is that women may trust gay men more and perceive them as less likely to engage in sexually or competitively motivated deception (Russell et al. 2018; Russell et al. 2017; Semenyna and Vasey 2021).

The present findings extend this research by showing that women also had stronger motives to befriend asexual men than heterosexual men. Future research is needed to determine whether similar underlying mechanisms, such as reduced sexual threat or increased trust, also apply in the case of asexual men (Russell et al. 2017).

Women who were more inclined to befriend sexual minority men were also more likely to share knowledge with and express other-interest in these men. These relationships are likely related, given the strong correlations among these three variables. Friendships are often built on reciprocity (Rivas 2009), and women may expect greater reciprocal behavior and emotional symmetry from gay or asexual men than from heterosexual men. This expectation could contribute to the increased willingness to support sexual minority men (Bedrov and Gable 2024; Hall 2011; Olk and Gibbons 2010).

Male participants in the present study were more willing to share knowledge with and show other-interest in lesbian women than in heterosexual women. This is in line with previous findings that lesbian women more often form cross-gender friendships than heterosexual women (Baiocco et al. 2014; Galupo 2009; Rumens 2011). However, the specific mechanisms by which men support or help lesbian women remain underexplored (Bedrov and Gable 2024; Hall 2011; Olk and Gibbons 2010). These friendships between men and lesbian women may also be influenced by differences in privilege and lived experience, particularly when lesbian women experience minority stress (Dion 2023).

In contrast to past research showing that heterosexual men often socially distance themselves from gay male characters (Cook and Cottrell 2024), male participants in the present study were more likely to befriend a single-by-choice gay man than a gay man in a committed relationship. This pattern may not be due to adherence to allonormativity (Brandley and Spencer 2023) but instead may reflect heterosexist beliefs, defined as the devaluation of non-heterosexual orientations (Price 1999). One potential explanation is that single-by-choice gay men might display fewer public expressions of same-gender affection than gay men in relationships. This difference may reduce the likelihood of triggering bias among male observers (Floyd 2000; Kite et al. 2021; van de Rozenberg et al. 2024).

Attitudes toward gay men and attitudes toward same-gender sexual behavior can differ. For instance, in one study, heterosexual men reported low prejudice toward gay individuals but rated photos of two men kissing as significantly more disgusting than photos of a heterosexual couple kissing or neutral images (Kiebel et al. 2017; O’Handley et al. 2017). Moreover, sexual minority individuals often face pressure to “perform” same-gender behaviors in order to validate their identity (Boyer and Galupo 2015). As a result, participants may have perceived single-by-choice gay men as less authentic in their sexual identity than gay men in relationships, which in turn may have reduced their bias (Cook and Cottrell 2024).

In Germany, men are more likely than women to hold negative opinions about same-gender sexual behavior (Ludwig et al. 2023). Organizational interventions that encourage perspective-taking and foster awareness of unconscious or unintentional bias can help reduce negative attitudes and discriminatory behavior toward sexual minority individuals (Felten et al. 2024; Gould et al. 2025). Making employees aware of these biases is an important first step. In addition, formulating clear rules and organizational policies that explicitly prohibit discriminatory behavior can help establish standards and accountability. Furthermore, increasing positive contact and providing more opportunities for meaningful interaction with sexual minority individuals have been shown to reduce prejudice and improve attitudes (Cramwinckel et al. 2021; Lemm 2006).

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. Vignettes offer a valuable method for simulating real-life decision-making in a controlled context (Riley et al. 2021). However, it remains unclear whether the brief scenario used in the present study elicited the types of emotional responses typically involved in workplace interactions. Although participants were tested on their recall of the vignette, future studies may benefit from employing qualitative methods such as the think-aloud protocol to better understand the emotions and thought processes triggered by vignette content (Eccles and Arsal 2017).

To reduce potential confounding by sexual interest, the vignette included the statement “but you also realize that you find Toni sexually unattractive.” Furthermore, participants’ sexual orientation was statistically controlled in all analyses.

While many findings showed small effect sizes, this does not negate their practical importance. Sexual minority individuals often experience micro-practices, small acts of exclusion or bias, that accumulate over time and across contexts (Diamond and Alley 2022; Liang et al. 2019). Although each instance may appear minor, the cumulative impact can be substantial.

The number of sexual minority participants in this study was too small to include sexual orientation as a factor in the analysis. It is possible that sexual minority individuals hold fewer heteronormative beliefs than heterosexual participants (García-Berbén et al. 2022). However, it is also possible that internalized stigma may shape their responses toward other sexual minority individuals (Antebi-Gruszka and Schrimshaw 2018; Berg et al. 2016; Szymanski and Mikorski 2016). Similarly, the experiences of gender minority participants were not analyzed due to small sample size. Future research should use targeted recruitment strategies to ensure adequate representation of sexual and gender minority individuals.

In addition, future studies should include more than two gender categories. Gender minority individuals frequently encounter systemic barriers in the workplace that were not addressed in the present study (Hart and Shakespeare-Finch 2022).

As with most survey-based studies, the current findings are based on self-reports. Participants may have provided socially desirable responses, although vignettes are generally seen as less susceptible to this issue (Choi and Pak 2005; Wilks 2004). Finally, participant motivation and attention were addressed by excluding individuals who failed multiple vignette comprehension checks (Huang et al. 2012). This suggests that the remaining participants engaged with the materials carefully.

Conclusion

The present study found that female participants were less willing to share knowledge with individuals who were single by circumstance than with those in committed relationships (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that subtle biases or micro-practices may disadvantage single individuals in workplace contexts. Further research is needed to examine other forms of singlism and the extent to which such biases cause stress or reduce performance (DePaulo 2023; DePaulo and Morris 2005).

Another key finding was that male participants were more likely to befriend a single-by-choice gay man than a gay man in a relationship. This result may be better explained by heterosexist attitudes (Price 1999) rather than by beliefs about the value of being in a relationship (Brandley and Spencer 2023). Future research should investigate organizational interventions that aim to reduce discriminatory attitudes and behaviors toward sexual minority individuals (Felten et al. 2024). It is also important to explore individual, social, and organizational factors that support the development of friendships across differences in privilege and experiences of discrimination (Dion 2023).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

All other means are reported in the Supplementary Material and contrasts were non-significant (p > 0.05).

Even though the relationship Gender participant x Character’s gender x Character’s sexual orientation was not significant, the contrast analysis revealed that male participants had more other-interests in lesbian women (M = 4.5, SD = 0.1) than in heterosexual women (M = 4.1, SD = 0.1; mean difference = -0.4, SE = 0.1, p = .022), but similar other-interests in gay men (M = 4.2, SD = 0.1) as in heterosexual men (M = 4.1, SD = 0.1; mean difference = −0.1, SE = 0.2, p = 0.504).

References

Antebi-Gruszka N, Schrimshaw EW (2018) Negative attitudes toward same-sex behavior inventory: An internalized homonegativity measure for research with bisexual, gay, and other non–gay-identified men who have sex with men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diversity 5(2):156–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000292

APA (2002) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Am Psychologist 57(12):1060–1073. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1060

Apostolou M, Alexopoulos S, Christoforou C (2023) The price of being single: An explorative study of the disadvantages of singlehood. Personal Individ Differences 208:112208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112208

Baiocco R, Santamaria F, Lonigro A, Ioverno S, Baumgartner E, Laghi F (2014) Beyond similarities: Cross-gender and cross-orientation best friendship in a sample of sexual minority and heterosexual young adults. Sex Roles 70(3):110–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0343-2

Beam AJ, Wellman JD (2024) The consequences of prototypicality: Testing the prejudice distribution account of bias toward gay men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diversity 11(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000581

Beckmeyer JJ, Jamison TB (2023) Understanding singlehood as a complex and multifaceted experience: Insights from relationship science. J Fam Theory Rev 15(3):562–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12497

Bedrov A, Gable SL (2024) Just between us…: The role of sharing and receiving secrets in friendship across time. Personal Relatsh 31(1):91–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12527

Berdahl JL, Moore C (2006) Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. J Appl Psychol 91(2):426–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.426

Berg RC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Ross MW (2016) Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. J Homosexuality 63(4):541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788

Bock G-W, Zmud RW, Kim Y-G, Lee J-N (2005) Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q 29(1):87–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

Bogaert AF (2015) Asexuality: What it is and why it matters. J Sex Res 52(4):362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1015713

Borgogna NC, Vaughn J, Owen T, Brasil KM, Kraus SW, Levant RF, McDermott RC (2025) Differences in cross-sectional and daily diary problematic pornography use correlates. J Behav Addictions 14(1):155–165. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2025.00008

Bos AER, Dijker AJM, Koomen W (2007) Sex differences in emotional and behavioral responses to HIV+ individuals’ expression of distress. Psychol Health 22(4):493–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320600976257

Boyer CR, Galupo MP (2015) Prove it!’ same-sex performativity among sexual minority women and men. Psychol Sexuality 6(4):357–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2015.1021372

Brandley B, Dehnert M (2024) “I am not a robot, I am asexual”: A qualitative critique of allonormative discourses of ace and aro folks as robots, aliens, monsters. J Homosexuality 71(6):1560–1583. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2023.2185092

Brandley B, Spencer LG (2023) Rhetorics of allonormativity: The case of asexual Latter-day Saints. South Commun J 88(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2022.2108891

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cultural Psychol 1(3):185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Cardoso BLA, Paim K, Catelan RF, Liebross EH (2023) Minority stress and the inner critic/oppressive sociocultural schema mode among sexual and gender minorities. Curr Psychol 42:19991–19999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03086-y

Chandler J, Shapiro D (2016) Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 12(1):53–81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093623

Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE (2017) What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit. J Soc Issues 73(3):586–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12233

Choi BCK, Pak AWP (2005) A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Preventing Chronic Dis 2(1), Article A13

Cook CL, Cottrell CA (2024) Relationship status moderates sexual prejudice directed toward lesbian women but not gay men. J Soc Psychol. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2024.2321580

Cramwinckel FM, Scheepers DT, Wilderjans TF, De Rooij R-JB (2021) Assessing the effects of a real-life contact intervention on prejudice toward LGBT people. Arch Sex Behav 50:3035–3051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02046-0

Curran PG (2016) Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J Exp Soc Psychol 66:4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.07.006

DePaulo B (2023) Single and flourishing: Transcending the deficit narratives of single life. J Fam Theory Rev 15(3):389–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12525

DePaulo BM, Morris WL (2005) Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inq 16(2/3):57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2005.9682918

DePaulo BM, Morris WL (2006) The unrecognized stereotyping and discrimination against singles. Curr Directions Psychological Sci 15(5):251–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00446.x

Diamond LM, Alley J (2022) Rethinking minority stress: A social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse populations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 138:104720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104720

Dion KK (2023) Intergroup friendship: A reflective spotlight. Personal Relatsh 30(4):1185–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12514

Dupuis HE, Girme YU (2024) Cat ladies” and “Mama’s boys”: A mixed-methods analysis of the gendered discrimination and stereotypes of single women and single men. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 50(2):314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231203123

Eccles DW, Arsal G (2017) The think aloud method: What is it and how do I use it? Qualitative Res Sport, Exerc Health 9(4):514–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1331501

Endendijk JJ, van Baar AL, Deković M (2020) He is a stud, she is a slut! A meta-analysis on the continued existence of sexual double standards. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 24(2):163–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868319891310

Federal Act on the Organisation of Universities and their Studies (Universitätsgesetz 2002 – UG), (2002)

Felten H, Keuzenkamp S, de Wit J (2024) Interventions used in practice to reduce prejudice and stereotypes toward lesbian and gay people: Theory-based evaluation. J Sex Res. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2331275

Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd

Finch J (1987) The Vignette Technique in survey research. Sociology 21(1):105–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038587021001008

Fitzpatrick J (2023) Voluntary and involuntary singlehood: Salience of concepts from four theories. J Fam Theory Rev 15(3):506–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12526

Floyd K (2000) Affectionate same-sex touch: The influence of homophobia on observers’ perceptions. J Soc Psychol 140(6):774–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540009600516

Fraser G (2018) Evaluating inclusive gender identity measures for use in quantitative psychological research. Psychol Sexuality 9(4):343–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1497693

Furman W, Buhrmester D (2009) Methods and measures: The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version. Int J Behav Dev 33(5):470–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025409342634

Galupo MP (2009) Cross-category friendship patterns: Comparison of heterosexual and sexual minority adults. J Soc Personal Relatsh 26(6-7):811–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509345651

García-Berbén AB, Pereira H, Lara-Garrido AS, Álvarez-Bernardo G, Esgalhado G (2022) Psychometric validation of the Portuguese version of the Modern Homonegativity Scale among Portuguese college student. Eur J Investig Health, Psychol Educ 12(8):1168–1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12080081

Gerbasi ME, Prentice DA (2013) The Self- and Other-Interest Inventory. J Personal Soc Psychol 105(3):495–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033483

Gilchrist KR (2023) Silencing the single woman: Negotiating the ‘failed’ feminine subject in contemporary UK society. Sexualities 26(1-2):162–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607211041100

Gleibs IH (2017) Are all “research fields” equal? Rethinking practice for the use of data from crowdsourcing market places. Behav Res Methods 49(4):1333–1342. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0789-y

Gould WA, Kinitz J, Shahidi FV, MacEachen E, Mitchell C, Venturi DC, Ross LE (2025) Improving LGBT labor market outcomes through laws, workplace policies, and support programs: A scoping review. Sexuality Res Soc Policy 22:329–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00918-9

Greitemeyer T (2009) Stereotypes of singles: Are singles what we think? Eur J Soc Psychol 39(3):368–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.542

Gui T (2020) Leftover women” or single by choice: Gender role negotiation of single professional women in contemporary China. J Fam Issues 41(11):1956–1978. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x20943919

Gupta K (2017) And now I’m just different, but there’s nothing actually wrong with me”: Asexual marginalization and resistance. J Homosexuality 64(8):991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236590

Hall JA (2011) Sex differences in friendship expectations: A meta-analysis. J Soc Personal Relatsh 28(6):723–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510386192

Hart B, Shakespeare-Finch J (2022) Intersex lived experience: Trauma and posttraumatic growth in narratives. Psychol Sexuality 13(4):912–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1938189

Hertel J, Schütz A, DePaulo BM, Morris WL, Stucke TS (2007) She’s single, so what? How are singles perceived compared with people who are married? Z f ür Familienforschung 19(2):139–158

Higginbottom B (2024) The nuances of intimacy: Asexual perspectives and experiences with dating and relationships. Arch Sex Behav 53:1899–1914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-024-02846-0

Hospitals and Health Resorts Act (Bundesgesetz über Krankenanstalten und Kuranstalten - KAKuG), (2016)

Huang JL, Curran PG, Keeney J, Poposki EM, Deshon RP (2012) Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. J Bus Psychol 27(1):99–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9231-8

Javaid A (2021) A table for one: The homosexual single and the absence of romantic love. In C.-H. Mayer & E. Vanderheiden (Eds.), International handbook of love: Transcultural and transdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 391–403). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45996-3_21

Kahalon R, Bareket O, Vial AC, Sassenhagen N, Becker JC, Shnabel N (2019) The Madonna-whore dichotomy is associated with patriarchy endorsement: Evidence from Israel, the United States, and Germany. Psychol Women Q 43(3):348–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319843298

Kiebel EM, McFadden SL, Herbstrith JC (2017) Disgusted but not afraid: Feelings toward same-sex kissing reveal subtle homonegativity. J Soc Psychol 157(3):263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2016.1184127

Kislev E (2024) Singlehood as an identity. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 35(2):258–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2023.2241937

Kislev E, Marsh K (2023) Intersectionality in studying and theorizing singlehood. J Fam Theory Rev 15(3):412–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12522

Kite ME, Whitley BE, Buxton K, Ballas H (2021) Gender differences in anti-gay prejudice: Evidence for stability and change. Sex Roles 85:721–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-021-01227-4

Komlenac N, Hochleitner M (2023) Being single does not equate with being unhappy. J Sex Med 20(12):1361–1363. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsxmed/qdad122

Komlenac N, Mair C, Walther A, Hochleitner M (2025) Perceiving being single as inherently negative: When participant ratings of another person’s life satisfaction rely solely on that person’s relationship status. BMC Psychol. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03359-8

Kononov N, Ein-Gar D (2023) Beautiful strangers: Physical evaluation of strangers is influenced by friendship expectation. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 50(12):1725–1736. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231180150

Lavender-Stott ES (2023) Queering singlehood: Examining the intersection of sexuality and relationship status from a queer lens. J Fam Theory Rev 15(3):428–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12521

Lemm KM (2006) Positive associations among interpersonal contact, motivation, and implicit and explicit attitudes toward gay men. J Homosexuality 51(2):79–99. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n02_05

Lesiak AJ (2023) I’m a trans scientist — here’s my advice for navigating academia. Nature. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00923-3

Liang R, Dornan T, Nestel D (2019) Why do women leave surgical training? A qualitative and feminist study. Lancet 393(10171):541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32612-6

Ludwig J, Brunner F, Wiessner C, Briken P, Gerlich MG, von dem Knesebeck O (2023) Public attitudes towards sexual behavior–Results of the German Health and Sexuality Survey (GeSiD). PLOS ONE 18(3):e0282187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282187. Article

Marchi M, Travascio A, Uberti D, De Micheli E, Quartaroli F, Laquatra G, Grenzi P, Pingani L, Ferrari S, Fiorillo A, Converti M, Pinna F, Amaddeo F, Ventriglio A, Mirandola M, Galeazzi GM (2024) Microaggression toward LGBTIQ people and implications for mental health: A systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry 70(1):23–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231194478

Marchia J, Sommer JM (2019) (Re)defining heteronormativity. Sexualities 22(3):267–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717741801

Martin RJ, Hine DW (2005) Development and validation of the Uncivil Workplace Behavior Questionnaire. J Occup Health Psychol 10(4):477–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.477

Meyer IH (1995) Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav 36(1):38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bull 129(5):674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer IH (2013) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diversity 1(S):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.3

Möller C, Passam S, Riley S, Robson M (2024) All inside our heads? A critical discursive review of unconscious bias training in the sciences. Gend, Work Organ 31(3):797–820. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.13028

Moser C, Hinderliter A (2015) Asexual. In P. Whelehan & A. Bolin (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality (pp. Article 9781118896877). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs038

O’Handley BM, Blair KL, Hoskin RA (2017) What do two men kissing and a bucket of maggots have in common? Heterosexual men’s indistinguishable salivary α-amylase responses to photos of two men kissing and disgusting images. Psychol Sexuality 8(3):173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2017.1328459

Olk PM, Gibbons DE (2010) Dynamics of friendship reciprocity among professional adults. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(5):1146–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00614.x

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK (2015) The stigma complex. Annu Rev Sociol 41(1):87–116. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145702

Pignotti M, Abell N (2009) The negative stereotyping of single persons scale: Initial psychometric development. Res Soc Work Pract 19(5):639–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731508329402

Price J (1999) Navigating differences: Freindships between gay and straight men. Routledge

Riley AH, Critchlow E, Birkenstock L, Itzoe ML, Senter K, Holmes NM, Buffer SW (2021) Vignettes as research tools in global health communication: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2020. J Commun Healthc 14(4):283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2021.1945766

Rivas J (2009) Friendship selection. Int J Game Theory 38(4):521–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00182-009-0168-3

Rumens N (2011) Minority support: Friendship and the development of gay and lesbian managerial careers and identities. Equality, Diversity Incl: Int J 30(6):444–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151111157684

Russell EM, Ickes W, Ta VP (2018) Women interact more comfortably and intimately with gay men—but not straight men—after learning their sexual orientation. Psychological Sci 29(2):288–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617733803

Russell EM, Ta VP, Lewis DMG, Babcock MJ, Ickes W (2017) Why (and when) straight women trust gay men: Ulterior mating motives and female competition. Arch Sex Behav 46(3):763–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0648-4

Scherr A, Breit H (2018) Erfolgreiche Bewältigung von Diskriminierung. In P. Genkova & A. Riecken (Eds.), Handbuch Migration und Erfolg: Psychologische und sozialwissenschaftliche Aspekte (pp. 1–24). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18403-2_41-1

Semenyna SW, Vasey PlL (2021) Women’s trust in gay men: An experimental study. Personal Individ Differences 175:110727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110727. Article

Slonim G, Gur-Yaish N, Katz R (2015) By choice or by circumstance? Stereotypes of and feelings about single people. Stud Psychologica 57(1):35–48. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2015.01.672

Stokes Y, Vandyk A, Squires J, Jacob J-D, Gifford W (2019) Using Facebook and LinkedIn to recruit nurses for an online survey. West J Nurs Res 41(1):96–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945917740706

Szymanski DM, Mikorski R (2016) External and internalized heterosexism, meaning in life, and psychological distress. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diversity 3(3):265–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000182

United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Retrieved 08.05.2025 from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

van de Rozenberg TM, Kroes ADA, van der Pol LD, Groeneveld MG, Mesman J (2024) Same-sex kissing and having a gay or lesbian child: A bridge too far? Parent-child similarities in homophobic attitudes and observed parental discomfort. J Homosexuality 71(10):2341–2365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2023.2233658

Vu K, Riggs DW, Due C (2022) Exploring anti-asexual bias in a sample of Australian undergraduate psychology students. Psychol Sexuality 13(4):984–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1956574

Wallander L (2009) 25 years of factorial surveys in sociology: A review. Soc Sci Res 38(3):505–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.03.004

Ward MK, Meade AW (2023) Dealing with careless responding in survey data: Prevention, identification, and recommended best practices. Annu Rev Psychol 74(1):577–596. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-040422-045007

Warner NS, Njathi-Ori CW, O’Brien EK (2020) The GRIT (Gather, Restate, Inquire, Talk It Out) Framework for addressing microaggressions. JAMA Surg 155(2):178–179. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4427

Weston R, Gore PA (2006) A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Counseling Psychologist 34(5):719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345

Wilks T (2004) The use of vignettes in qualitative research into social work values. Qualitative Soc Work: Res Pract 3(1):78–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325004041133

World Medical Association (2013) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20):2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Wyatt TR, Johnson M, Zaidi Z (2022) Intersectionality: A means for centering power and oppression in research. Adv Health Sci Educ 27:863–875. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10110-0

Young SK, Bond MA (2023) A scoping review of the structuring of questions about sexual orientation and gender identity. J Community Psychol 51(7):2592–2617. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.23048

Zivony A, Reggev N (2023) Beliefs about the inevitability of sexual attraction predict stereotypes about asexuality. Arch Sex Behav 52:2215–2228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02616-4

Acknowledgements

The study is funded by the State of the Tyrol (F.44681).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NK, MH. Data curation: NK. Formal analysis: NK. Funding acquisition: NK. Investigation: NK. Methodology: NK. Project administration: NK. Resources: NK. Software: NK. Supervision: NK. Validation: NK. Visualization: NK. Writing – original draft: NK. Writing – review & editing: NK, MH, JB, AW. Revisions: NK All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Review Board (ERB) of the Medical University of Innsbruck exempted the present study from full ethics review on 27 January 2022 (ID: 27.01.2022/MJ), as under Austrian law it did not require formal approval by an ethics committee. This was because the study was not classified as a medical study (“Federal Act on the Organisation of Universities and their Studies (Universitätsgesetz 2002 – UG)”, 2002; “Hospitals and Health Resorts Act (Bundesgesetz über Krankenanstalten und Kuranstalten - KAKuG)”, 2016).

Informed consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013) and the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA 2002). Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to their participation. Before beginning the online questionnaire (administered between October and November 2023), participants were presented with an information page describing the study aims, procedures, voluntary nature of participation, data protection and confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Only those who confirmed their understanding and provided active consent by clicking the “I agree” button were able to access the survey. Consent was recorded on the date of each participant’s survey completion. Data were collected anonymously and stored securely for research purposes only.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Komlenac, N., Haller, M., Birke, J. et al. Benevolent intentions towards a new co-worker depend on the co-worker’s sexual orientation and relationship status. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05963-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05963-w