Abstract

Illegitimate tasks, as a prevalent source of workplace stress, exert a substantial impact on employee behavior. Drawing on affective events theory and conservation of resources theory, the present study investigates the effects of illegitimate tasks on employee silence and prohibitive voice behavior, with discrete negative emotions—specifically boredom and anger—serving as mediators. Additionally, the study examines the cross-level moderating role of job insecurity climate. Data were collected from 459 employees nested within 89 teams, and analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) and SPSS. The results indicate that illegitimate tasks elicit boredom and anger, which subsequently lead to increased silence and enhanced prohibitive voice behavior, respectively. Moreover, job insecurity climate significantly weakens the positive association between anger and prohibitive voice behavior, while its moderating effect on the relationship between boredom and silence behavior is not statistically significant. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the emotional and contextual mechanisms underlying employees’ responses to illegitimate tasks and offer practical implications for managing workplace stressors and fostering constructive employee behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High levels of stress are prevalent across many occupations, with studies reporting a significant rise in Western countries over the past few decades (Lahti and Kalakoski 2024). In China, rapid economic development and intensified workplace demands have similarly heightened occupational stress, with its negative impacts becoming increasingly evident. Among various stressors, illegitimate tasks—defined as work assignments that violate employees’ professional roles and identities (Semmer et al. 2010)—have emerged as a prominent source of workplace stress in modern organizational contexts. These tasks undermine employees’ sense of purpose and contribute to significant psychological strain, leading to adverse outcomes such as diminished job satisfaction, mental health issues, and reduced work engagement and work performance (Kilponen et al. 2021; Koçak and Ünal 2022; Andrade and Neves 2024). Surveys consistently show the widespread prevalence of illegitimate tasks, with a substantial proportion of employees identifying such assignments as part of their workload (Shaya et al. 2024). In Chinese enterprises, the challenges posed by illegitimate tasks are particularly acute due to hierarchical workplace structures and collectivist cultural norms, which often amplify the burden of role violations (Zou et al. 2023). Interviews with employees at various organizational levels further underscore the pervasive nature of these tasks and their profound implications for workplace dynamics (Li et al. 2024). Understanding how employees respond to illegitimate tasks is therefore essential for developing strategies that enhance employee well-being and improve organizational efficiency.

While existing research has demonstrated that illegitimate tasks can lead to overt negative behaviors (see Table 1), these findings do not fully capture the broader spectrum of employee responses, particularly those driven by motives of resource preservation or harm prevention. Silence behavior, defined as the withholding of valuable suggestions or opinions, reflects a passive coping strategy that allows employees to conserve psychological resources when dealing with stressors like illegitimate tasks (Dyne et al. 2003). In contrast, illegitimate tasks may also evoke prohibitive voice, a form of active resistance aimed at preventing harm or addressing inefficiencies in the workplace (Liang et al. 2012). Unlike promotive voice—which is future-oriented, innovation-driven, and requires significant cognitive and emotional investment—prohibitive voice focuses on drawing attention to disruptions in the current status quo (e.g., coordination issues) or identifying risks that could hinder organizational efficiency (e.g., flawed processes) (Liang et al. 2012). Given its reactive and harm-prevention orientation, prohibitive voice is more likely to be triggered by external work pressures or immediate stressors, such as illegitimate tasks.

The voice or silence of employees constitutes a pivotal proposition concerning the organizational well-being and sustainable development. It is imperative to ascertain whether employees will voice their opinions in a prohibitive manner to relieve their dissatisfaction and attempt to change the situation when confronted with illegitimate tasks, or if they will opt for silence as a means of self-resource preservation, or perhaps a combination of both. Despite the significance of these behaviors, the mechanisms through which illegitimate tasks influence prohibitive voice and silence remain insufficiently examined. Emotions play a pivotal role in shaping these responses, as they directly impact employees’ decisions to speak up or withhold their perspectives (Duan 2012; Kashif et al. 2020). Illegitimate tasks often evoke strong negative emotional reactions, which can act as triggers for either proactive or defensive behaviors (Wang and Zong 2023). Hence, drawing on the framework of affective events theory (AET) and aligned with the conservation of resources theory (COR), this study explores the emotional pathways that connect illegitimate tasks to these behavioral outcomes. Specifically, it investigates how negative emotions function as a mediating mechanism, linking the experience of illegitimate tasks to the likelihood of employees engaging in either prohibitive voice or silence behavior.

It is also important to examine the organizational contexts in which employees may display different prohibitive voice or silence behaviors in response to illegitimate task assignments, as workplace characteristics significantly influence the affective pathways shaping an individual’s behavioral response to work events (Miao et al. 2024) and their decision-making process to speak up is highly context-dependent (Nyfoudi and Wilkinson 2024). This study focuses on job insecurity climate. The psychological sense of safety that employees derive from their work environment is a crucial determinant in whether they choose to express their opinions or remain silent (Chen and Tang 2019). When work environments threaten job security or career advancement, a lack of psychological safety can significantly diminish an employee’s willingness to express themselves, thereby making it more challenging for them to voice their dissatisfaction and increasing the likelihood of remaining silent (Breevaart et al. 2020). Moreover, due to the COVID-19 pandemic-induced unemployment crisis, job insecurity has become a crucial factor that employees pay more attention to in their work. Their behavioral decisions may significantly vary depending on the job insecurity climate. In comparison to a low job insecurity climate, employees in a high job insecurity climate may be more inclined to choose remaining silent rather than voicing their opinions.

To address these gaps, this study aims to investigate the affective mechanisms connecting illegitimate tasks to silence and prohibitive voice behaviors, incorporating job insecurity climate as a boundary condition. Taken together, this study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it enhances existing knowledge regarding how employees cope when assigned illegitimate tasks. Previous research has shown that illegitimate tasks tend to evoke negative work cognitions and emotions in employees (Ahmed et al. 2018; Pindek et al. 2018; Fila et al. 2023), leading to job burnout and fostering negative work behaviors (Zhao et al. 2022; Ouyang et al. 2023; Wang and Jiang 2023). However, limited attention has been given to the possibility of positive behavioral responses in this context. By assessing prohibitive voice and silence behavior, this study thus contributes to the literature by investigating whether employees assigned illegitimate tasks choose to conserve resources through a milder form of silence behavior or actively engage in voicing their concerns, being outspoken about issues that undermine the organization’s status quo. Second, by examining discrete negative emotions as a mechanism to explain the influence of illegitimate tasks on prohibitive voice and silence behavior, this study enriches the literature from an affective perspective. Third, in response to the call for emphasizing the influence of organizational contextual factors on individual coping processes through conducting cross-level research (Ding and Kuvaas 2023), this study explores whether employees’ decision-making regarding voice behavior produces varying outcomes in different workplace insecurity climates. such knowledge can assist organizations in mitigating adverse responses to illegitimate tasks by cultivating an appropriate organizational culture and climate.

Theoretical Background and hypotheses development

Illegitimate tasks refer to work assignments that violate normative expectations of what can reasonably be expected from an individual, thereby offending their professional identity and sense of self (Semmer et al. 2010). These tasks are broadly categorized into two types: unreasonable tasks, which fall outside the scope of employees’ responsibilities, such as assigning security staff to perform janitorial duties, and unnecessary tasks, which are inefficient or irrelevant, such as repetitive approvals due to a leader’s preference (Semmer et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020). Despite their differences, both types share two core characteristics. First, they breach role expectations by challenging employees’ understanding of their roles and creating a misalignment between organizational expectations and job responsibilities (Semmer et al. 2015; He et al. 2024). Second, they threaten professional identity by undermining employees’ sense of self-worth, signaling disrespect, and diminishing the significance of their contributions (Mäkikangas et al. 2023).

These characteristics collectively result in adverse outcomes, including psychological resource depletion and emotional distress (Wang and Zong 2023; Shaya et al. 2024). AET provides a valuable framework for understanding how illegitimate tasks, as negative work events, evoke emotional responses that shape employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Weiss and Cropanzano 1996). Through cognitive evaluations, employees compare these tasks against their role expectations and professional identity, leading to the development of emotional responses, which subsequently influence their attitudes and behaviors (Ilies et al. 2024). For instance, Miao et al. (2024) demonstrated that illegitimate tasks affect volunteer engagement through emotional labor, highlighting how AET links workplace stressors to emotional and behavioral outcomes. Within this framework, the emotional responses elicited by illegitimate tasks are particularly relevant for understanding their impact on silence and prohibitive voice behaviors (Pahng and Kang 2023).

While AET explains the emotional mechanisms driving these behaviors, COR complements this by focusing on the resource dynamics underlying employees’ responses to illegitimate tasks (Hobfoll et al. 2018). COR posits that individuals strive to protect, conserve, and replenish their valuable resources when faced with stressors (Yuan et al. 2024). The emotional distress triggered by illegitimate tasks signals a threat to resources such as self-esteem and professional identity (Shaya et al. 2024). In response, employees may adopt silence as a defensive strategy to conserve their remaining resources, avoiding further depletion. Conversely, they may perceive prohibitive voice as a proactive strategy to address the source of stress and potentially restore their resource balance (Halbesleben et al. 2014).

Together, AET and COR provide a nuanced framework for understanding how illegitimate tasks influence employees’ silence and prohibitive voice behaviors. AET highlights the emotional pathways linking illegitimate tasks to behavioral outcomes, while COR elucidates the motivational factors driving employees’ decisions to conserve or acquire resources. This integrated perspective allows for a comprehensive understanding of how negative work events, emotional reactions, and resource states collectively shape employee behavior in response to illegitimate tasks.

Illegitimate tasks and employees’ silence behavior and prohibitive voice behavior

Although silence and voice are related, they are distinct and relatively independent concepts (Duan 2012; Sherf et al. 2021; Hao et al. 2022). Voice behavior involves expressing opinions and providing suggestions on significant organizational issues, yet it does not necessarily require complete information sharing (Yuan et al. 2024). The absence of voice, referred to as “no voice,” reflects a lack of ideas or proactive concealment, whereas silence behavior entails the deliberate withholding of information or viewpoints (Sherf et al. 2021). Liang et al. (2012) further categorized voice behavior into promotive voice, which focuses on generating new ideas to improve organizational functioning, and prohibitive voice, which addresses existing or potential problems. Prohibitive voice is critical for organizational health as it identifies hidden issues and prevents problematic outcomes. Silence and voice behaviors are not two ends of the same continuum but rather complementary constructs that merit concurrent examination (Pinder and Harlos 2001). Research indicates that stressors, such as perceived unfairness and disrespect, are significant predictors of employees’ tendencies to either voice concerns or remain silent (De Clercq and Pereira 2023). As illegitimate tasks often convey perceptions of unfair treatment and disrespect (Schulte-Braucks et al. 2019; Semmer et al. 2015), they can substantially influence employees’ decisions to speak up or withhold their opinions.

Firstly, illegitimate tasks may significantly influence employees’ silence behavior. On one hand, being assigned unnecessary or unreasonable tasks can lead employees to perceive these assignments as unfair, resulting in doubts about their value and significance within the organization. Such perceptions elicit negative cognitions and emotions (Semmer et al. 2015) and require employees to expend psychological resources for self-regulation (Baumeister and Vohs 2007). On the other hand, illegitimate tasks violate the principle of reciprocal exchange between employees and the organization (Ouyang et al. 2022). These tasks demand that employees fulfill their primary responsibilities while investing additional time and energy in activities outside their role, increasing the costs of work engagement, depleting cognitive resources, and encroaching upon their professional identity. This cumulative strain leads to significant psychological resource depletion, rendering employees “resource poor” (Zhang et al. 2021).

In response, employees may adopt defensive strategies to safeguard their remaining resources (Hobfoll et al. 2018). Illegitimate tasks trigger avoidance motives and heighten resource protection awareness through cognitive appraisal (Yuan et al. 2024). To prevent further resource loss, employees may preserve resources by withholding information and contributions beneficial to organizational development. Silence behavior, in this context, serves as a “cost avoidance” strategy and self-protection mechanism, helping restore psychological balance and conserve existing resources (Zhang et al. 2021). Based on this reasoning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Illegitimate tasks are positively associated with employees’ silence behavior.

Secondly, illegitimate tasks may also serve as a driving force for employees’ prohibitive voice behavior. While mainstream views emphasize the negative impacts of illegitimate tasks, recent studies have highlighted their potential positive effects (Ding and Kuvaas 2023; He et al. 2024). According to COR, stress can lead to resource depletion but may also act as a catalyst for resource enhancement (He et al. 2024). When facing resource losses, employees may strategically channel their remaining resources into proactive efforts to acquire new ones (Halbesleben et al. 2014). For instance, several studies suggest that employees adopt job crafting as a proactive strategy to cope with illegitimate tasks and replenish their resource pool (Jiang and Wang 2024; Mäkikangas et al. 2023; He et al. 2024). Job crafting involves actively reshaping and redefining job tasks to better align with personal and professional goals (Bindl et al. 2019).

Similarly, prohibitive voice behavior, which entails identifying and addressing existing or potential organizational problems, reflects a proactive effort to instigate change (Liang et al. 2012). Employees confronted with illegitimate tasks may be more inclined to adopt prohibitive voice strategies as a means of managing these challenges and regaining control over their circumstances (He et al. 2024). From a resource acquisition perspective, such behavior allows employees to mitigate the resource depletion caused by job stress and avoid further losses (Fila and Eatough 2020). By raising concerns about organizational issues, prohibitive voice enables employees to secure resource returns more quickly (Li and Zhong 2020). This behavior holds instrumental value, as it focuses on harm prevention and mitigating adverse consequences associated with illegitimate tasks (Lin and Johnson 2015). Furthermore, engaging in prohibitive voice not only helps employees reduce perceived losses but also positively contributes to their job satisfaction (Liang et al. 2012). Based on these insights, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H2: Illegitimate tasks are positively associated with employees’ prohibitive voice behavior.

The mediating role of negative emotions

Discrete emotions denote specific inclinations towards action or states of preparedness, each characterized by a unique set of motivational and relational objectives aimed at influencing, preserving, or altering a given circumstance (Wattoo et al., 2025). For instance, anger serves as a catalyst for addressing perceived injustices (Khattak et al., 2019), thereby eliciting behaviors associated with approach or confrontation (Lebel 2017). Subsequent studies consistently demonstrate that experiencing anger is generally linked to proactive behaviors (Lebel 2017; Liu et al. 2024). The emotion of anger is characterized as “negative & forceful” (HUMAINE Association 2006), highlighting its motivational and assertive aspects, often associated with employees’ proactive speaking up (Kirrane et al. 2017). Moreover, another prevalent negative emotional state prompts action tendencies aimed at alleviating adverse emotional conditions, typically manifesting as “negative & passive,” as exemplified by boredom. Despite its frequent occurrence in the workplace, boredom often lacks proper acknowledgment (Gkorezis and Kastritsi 2017). Regarded as a moderately negative emotion, boredom is less likely to precipitate immediate extreme behaviors such as counterproductive work behavior (CWB) (van Hooff and van Hooft 2014), but instead tends to lead to withdrawal behaviors among employees, potentially closely associated with employee silence (Kirrane et al., 2017). Therefore, this study adopts a discrete emotions perspective, investigating the mediating role of both anger and boredom.

Empirical analyses have demonstrated a significant positive correlation between illegitimate tasks and specific negative emotions experienced by employees, such as job resentment, shame, and anger (Ding and Kuvaas 2023; Wang and Jiang 2023). Some scholars have also included various specific emotions in constructing the concept of negative emotion. For example, Ahmed et al. (2018) integrated three specific emotions: anger, anxiety, and depression, while Pindek et al. (2018) selected four negative emotions: anger, hatred, disgust, and resistance. Building upon this, they verified the inducing effect of illegitimate tasks on employees’ negative emotions by integrating multiple emotions. Illegitimate tasks, which assign work beyond employees’ job roles, create a sense of discrepancy when employees compare role expectations with actual work situations (Omansky et al. 2016). From the perspective of relative deprivation, individuals experience distress when they perceive that the “actual state” does not match the “should state,” leading to negative feelings of being deprived of positive outcomes (Walker and Pettigrew 2011). Simultaneously, illegitimate tasks signal disrespect and denigration to employees, requiring them to complete unreasonable and unnecessary tasks at the expense of their individual resources (Zong et al. 2022). This results in a perception of effort-reward imbalance when employees compare job inputs and outcomes, leading to feelings of tension and reduced happiness (Yang and Li 2021). Such experiences of distress and dissatisfaction may evoke discrete emotions such as anger (Munir et al. 2017; Jordan et al. 2020).

Additionally, according to control-value theory, emotions arise from individual appraisals of control over and value of their actions and outcomes (Pekrun 2006). In this context, boredom may arise when individuals engage in unchallenging activities or those perceived as lacking value due to being unenjoyable or unrelated to goal attainment (Harju et al. 2022). By applying these principles, it can be inferred that illegitimate tasks, characterized by a lack of significance or relevance, may exacerbate employees’ feelings of boredom. When employees engage in tasks they perceive as meaningless or inconsequential, they are likely to experience heightened levels of boredom. In summary, based on existing research and theoretical analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Illegitimate tasks are positively associated with employees’ discrete negative emotions, namely, anger and boredom.

Emotions can be defined as subjective feeling states that shape our behavior and influence how we interact with others (Kirrane et al. 2017). In the context of employee voice and silence behavior, previous studies have examined how positive or negative emotions mediate the effects of variables such as abusive supervision, self-sacrificing leadership, upward developmental feedback, and workplace ostracism on employee voice or silence behavior (Kiewitz et al. 2016; Kashif et al. 2020). Emotions have long been recognized as a critical factor influencing human behavior, as specific emotional states can predict an individual’s attitudes and actions (Ashkanasy et al. 2017). Research suggests that emotions such as anger and guilt can encourage employees to voluntarily report job-related injustices, while emotions such as anxiety, fear, and shame may lead to employee silence behavior (Morrison 2023; Kirrane et al. 2017). Furthermore, some scholars have investigated the broad categories of positive and negative emotions and pointed out that individual positive and negative emotions have dual effects on voice and silence decision-making, making them a “double-edged sword” (Duan 2012; Fu et al. 2012). It is evident that employee emotions play a significant role in explaining voice and silence behavior in the workplace.

Negative emotions, such as anger triggered by illegitimate tasks, are often associated with heightened motivation and can lead to positive outcomes (Li and Zhong 2020). This motivational influence is closely intertwined with employees’ strategies for seeking resources (Zhang et al. 2021). Specifically, as a highly activating negative emotion, anger can serve as perceptual cues for individuals to identify and address problems in their current situation (Hsiung and Tsai 2017). When individuals adopt a strategy focused on acquiring resources, they become highly motivated and willing to challenge the status quo (Fu et al. 2012). In this context, prohibitive voice behavior, rooted in a loss-prevention perspective, directs attention to past or current issues (Li and Zhong 2020), underscoring a robust causal link between anger and prohibitive voice behavior (Lin and Johnson 2015). High-intensity activated negative emotions can cause employees to experience self-depletion, lack self-control, act impulsively, and engage in voice behavior without careful consideration (Lam et al. 2018). Under the dominance of negative emotions such as anger, employees may pay less attention to the potential adverse consequences of voice behavior, such as challenging leadership authority or leaving a troublesome impression (Morrison 2023). Consequently, they may break through their psychological defenses and aggressively point out problems in the organization, in an attempt to quickly obtain resource returns and alleviate negative emotions. As Kirrane et al. (2017) demonstrated that anger is not always a destructive emotion, but can be constructive in the form of speaking up. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4a: The specific negative emotion of anger plays a mediating role in the relationship between illegitimate tasks and employees’ prohibitive voice behavior.

In contrast to anger, boredom is characterized by diminished interest and concentration and can be defined as a negative (i.e., unpleasant, dissatisfying) and often deactivating (i.e., low arousal) activity-related emotion (Fisher, 1993). Employees often suppress boredom at work to “power through” boring tasks and objectives, resulting in lapses of attention and productivity deficits during future work episodes (Belinda et al. 2024). Previous research has linked boredom to reduced work engagement and burnout (Harju et al. 2022; Harju et al. 2023). Boredom at work reflects a perception of tasks as lacking in meaning and challenge, resulting in mental disengagement (Harju et al. 2023). The experience of boredom can be particularly frustrating as individuals feel unchallenged and perceive the situation as meaningless (Van Tilburg and Igou 2012). Consequently, employees may resort to silence, refraining from sharing their thoughts or suggestions, as they perceive the tasks unworthy of further engagement. This silence behavior could stem from a reluctance to invest additional effort in discussing or contributing to tasks perceived as unstimulating (Yuan et al. 2024). Hence, boredom may induce a cycle of suppression and subsequent disengagement, leading to silence among employees during collaborative efforts. Furthermore, the accumulation of workplace boredom can significantly influence employees’ perceptions of their work and themselves, leading them to become indifferent to organizational interests, neglect internal issues, and withhold contributions to organizational development (van Hooff and van Hooft 2014). This may prompt avoidance and inaction motives, ultimately resulting in silence behavior (Chen and Tang 2019). Thus, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4b: The specific negative emotion of boredom plays a mediating role in the relationship between illegitimate tasks and employees’ silence behavior.

The moderating effect of job insecurity climate

In today’s fast-paced world, technology is evolving rapidly, and information is constantly changing, which has led to an increase in complexity and ambiguity in the environment. Employees in the workplace are facing greater instability and uncertainty, including a decrease in the significance of their work, the replacement of their work by machines, or even losing their jobs (Wang et al. 2024). Such circumstances create a sense of job insecurity among employees (Sverke et al. 2002). Recently, scholars have turned their focus to job insecurity climate, defined as the shared perception among team members that they are about to lose their jobs within the team and that job continuity cannot be maintained (Sora et al. 2013). Job insecurity climate describes the characteristics of an organization or team and presents members’ common perceptions and emotional experiences of the work situation (Yüce-Selvi et al. 2023). A beneficial and efficient work climate can significantly enhance employees’ positive work behavior (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008). However, job insecurity climate, as a pressure atmosphere, has a significant negative impact on employees’ job satisfaction, happiness, organizational commitment, organizational trust, and work involvement (Sora et al. 2009; Hsieh and Kao 2021). This, in turn, hinders employees from exhibiting organizational citizenship behavior and innovative behavior, ultimately affecting their work performance, leading to their intention to leave and damaging their physical and mental health (Låstad et al. 2018). Nonetheless, some studies have also pointed out that anxiety about losing existing jobs and the expected risk to job continuity may to some extent stimulate employees’ innovation and motivation to work hard (Yang and Zhang, 2012).

This study posits that within a context of heightened job insecurity, employees often perceive an imminent risk of job loss and consequently grapple with feelings of powerlessness in safeguarding their current employment status (Sverke et al. 2002). This prevailing atmosphere of uncertainty can precipitate a decline in organizational trust and psychological safety (Sora et al. 2009), as employees may hesitate to fully invest themselves in their roles, fearing potential repercussions. Consequently, individuals may lean on their past experiences of success as a coping mechanism to navigate challenges and avoid disrupting the status quo or taking risks (Yang and Zhang 2012). The resulting psychological strain stemming from this uncertain organizational climate may undermine employees’ inclination to address negative emotions triggered by illegitimate tasks, altering their approach to seeking resources (Peltokorpi and Allen 2024). While negative emotions elicited by illegitimate tasks may typically serve as a catalyst for seeking change, the risk-averse tendencies instilled by a high job insecurity environment may counteract employees’ willingness to engage in proactive behaviors, such as prohibitive voice, driven by emotions like anger (Breevaart et al. 2020; Munoz Medina et al. 2023). This suggests that despite the potential motivational impact of negative emotions, the overarching context of job insecurity can significantly influence employees’ response strategies and dampen their readiness to challenge organizational norms (Yüce-Selvi et al. 2023). Therefore, the job insecurity climate may potentially diminish the positive impact of anger triggered by illegitimate tasks on prohibitive voice behavior.

On the other hand, the combination of high job insecurity and the boredom elicited by illegitimate tasks can create a synergistic effect, amplifying the tendency for employees to withdraw into silence (Yu et al., 2023). In an environment fraught with uncertainty regarding job stability, individuals may already experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety, consequently leading to diminished work engagement and job satisfaction (Hsieh and Kao, 2021). When confronted with tasks that lack meaningfulness or challenge, this stress may be compounded by feelings of ennui and disengagement commonly associated with boredom. Consequently, employees may find themselves more inclined to withhold their views and suggestions, opting instead to remain silent (Yu et al. 2023). This reluctance to speak up can be attributed to a desire to avoid drawing attention to oneself or risking potential negative consequences in an already uncertain organizational climate, as well as lower need fulfillment (Breevaart et al. 2020). Moreover, the dynamic interplay between job insecurity and boredom exacerbates the likelihood of silent behavior among employees, as the amalgamation of external pressures and internal discontent nurtures an atmosphere of reticence and disengagement (Hsieh and Kao 2021; Harju et al. 2023; Yu et al. 2023).

In summary, if the organization fails to provide job security, individually or collectively, employees’ tendency to behave favorably, including voice, might decrease (Yüce-Selvi et al. 2023). The job insecurity climate can impact employees’ perception of job stability and continuity, inducing psychological perceptions and behavioral tendencies that weaken the stimulating effect of angry on prohibitive voice behavior and strengthen the positive correlation between boredom and silence behavior. Based on this analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Job insecurity climate positively moderates the positive correlation between boredom and employees’ silence behavior, with this positive correlation being stronger when employees are in a high job insecurity climate.

H5b: Job insecurity climate negatively moderates the positive correlation between angry and employees’ prohibitive voice behavior, with this positive correlation being weaker when employees are in a high job insecurity climate.

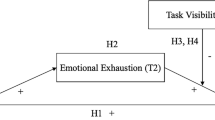

According to the analysis presented above, the theoretical model proposed in this study, which accounts for cross-level effects, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

This study conducted a comprehensive questionnaire survey among 25 enterprises located in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region of China, which is one of the most economically developed and industrially diverse regions in the country. The YRD region was chosen due to its pivotal role as a national economic engine, characterized by a high concentration of innovative enterprises and dynamic workforce structures. This makes it an ideal setting for investigating the organizational phenomena under study, such as illegitimate tasks and their behavioral consequences.

The sampled enterprises represent four key industries: construction (5), healthcare (4), manufacturing (9), and production and supply of electric power and heat (7). These industries were selected for their relevance to the study’s objectives, as they involve varying degrees of role complexity and task allocation, which are critical for exploring illegitimate tasks. Furthermore, the sizes of these enterprises, ranging from small to medium and large, ensure a diverse sample that captures heterogeneity in organizational practices and employee experiences. The 25 participating enterprises were identified through pre-established collaborations with the research group, which facilitated access to reliable data sources. Before distributing questionnaires, detailed communication was established with liaison personnel from each enterprise to explain the study’s objectives and procedures. This also allowed for the collection of pertinent information regarding company size and the number of work teams, ensuring the sampling process’s rigor. Using a simple random sampling technique, 92 work teams were selected, with team sizes ranging from 3 to 10 members. Tailored blank questionnaires were enclosed in sealed envelopes and dispatched to designated liaisons for distribution and subsequent collection.

A total of 500 questionnaires were disseminated across 92 teams, resulting in 459 valid responses after eliminating incomplete or invalid datasets. These responses represented 89 distinct work teams, yielding an effective response rate of 91.80%. The high response rate not only minimizes potential nonresponse bias but also ensures the robustness of the dataset for meaningful analysis. Moreover, the inclusion of employees from diverse departments within these enterprises enhances the generalizability of the findings across various organizational contexts.

In the sample dataset, the average number of members in each of the 89 work teams is 5.16. Of these teams, state-owned enterprises have the highest number of teams, with 44 teams accounting for 49.44%. Private enterprises follow with 22 teams, accounting for 24.72%, while the remaining 23 teams belong to joint ventures and other types of companies. Among the 459 participants, the gender ratio is balanced, with 205 males accounting for 44.66% and 254 females accounting for 55.34%. The age distribution is relatively wide, with the majority of participants being between 26–30 years old (110 people, 23.97%), followed by those above 40 years old (101 people, 22.00%). Over half of the participants hold a college undergraduate degree (264 people, 57.52%), and the majority of participants have worked in the company for more than 5 years (202 people, 44.01%). The sample distribution is broad and reasonable, with no limitations on the score ranges of each scale. This fulfills the research requirements and enables further statistical analysis.

Measurements

This study used the Likert 5-point scoring method for all measurement scales in this study. The responses for the illegitimate tasks scale were scored on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the frequency of their occurrence, ranging from “never” to “always”. Similarly, responses for the negative emotions scale were scored on a scale of 1 to 5 based on the extent to which they were experienced, ranging from “not at all” to “always”. The remaining items in the scales were scored based on the degree of agreement, with responses ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”. To control for potential confounding variables, this study included gender, age, education level, company nature, and work experience as control variables in the questionnaire. These variables were selected based on previous research and were included to ensure that their effects were fully considered in the analysis (Zhang et al. 2023; Lu et al. 2024).

Illegitimate tasks

The scale used in this study was developed by Semmer et al. (2010), consisting of 8 items that measure two dimensions, namely unreasonable tasks and unnecessary tasks. An example item for the former dimension is “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which you believe put you into an awkward position?” while an example item for the latter dimension is “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which keep you wondering if they make sense at all?”

Negative emotions

The self-report method was utilized to measure discrete negative emotions, which is considered the most straightforward and widely used approach for emotional assessment. Drawing on Qiu et al.‘s (2008) revised Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PA-NAS), participants indicated the frequency with which they felt or experienced anger and boredom during work or while thinking about work based on their experiences in the previous week.

Silence behavior

The scale is a modified version of the original scale developed by Dyne et al. (2003), which has been further refined by Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008). The revised scale consists of five items, with an example item being “ I remained silent when I had information that might have helped prevent a problem”.

Prohibitive voice behavior

The scale developed by Liang et al. (2012), which comprises five items, was used. A sample item is: “ Dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others”.

Job insecurity climate

The scale was adapted from the work of Hellgren and Sverke (2003) and consists of three items, such as “I am worried about having to leave my job before I would like to”. Individual employee scores were aggregated at the team level, and the results of the aggregation test showed an Rwg value of 0.88, an ICC(1) value of 0.69, and an ICC(2) value of 0.92, all of which met the standard criteria for aggregation. Thus, the job insecurity climate scale is considered suitable for aggregating individual source data to the team level.

Result analysis

Reliability and validity testing

This study employed Cronbach’s α coefficient and composite reliability (CR) to assess reliability, with results presented in Table 2. The internal consistency α coefficients of each variable ranged from 0.802 to 0.916, and CR values ranged from 0.807 to 0.922, all surpassing the baseline value of 0.700. Therefore, the reliability of the scales utilized in this study is deemed satisfactory.

Regarding convergent validity, this research conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and computed the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to evaluate aggregation validity. As depicted in Table 2, all variables exhibited AVE values exceeding 0.5. Subsequently, a five-factor model encompassing illegitimate tasks, negative emotions, employee silence behavior, prohibitive voice behavior, and job insecurity climate was examined through CFA using AMOS 21.0, with nested structural models established. The goodness-of-fit indices for each model are presented in Table 3. Among the tested models, the five-factor model demonstrated optimal fit, meeting recommended thresholds across all fit indices (χ2/df=2.180, RMSEA = 0.051, GFI = 0.917, NFI = 0.929, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.954). Furthermore, discriminant validity was assessed via Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT), with all HTMT values below the threshold of 0.85, indicating favorable discriminant validity of the questionnaire. HTMT results are presented in Table 2. In summary, the sample data of this study exhibit commendable reliability and validity.

Common method bias test

This study has diligently addressed the issue of common method bias by implementing rigorous preemptive control measures. These measures included ensuring strict anonymity, incorporating attention check questions in the questionnaire, and randomizing the order of questions to reduce bias related to specific items or topics. This proactive strategy has significantly enhanced the robustness and credibility of the research outcomes. Harman’s single-factor test demonstrated the effectiveness of these measures, showing that the common method factor explained merely 29.832% of the variance. This percentage is considered an acceptable indicator of common method bias according to established research standards (Waqas et al. 2021). Additionally, as presented in Table 3, the results of the single-factor structural equation model indicated unsatisfactory fit indices, with χ2/df=16.043, RMSEA = 0.181, GFI = 0.529, NFI = 0.455, CFI = 0.469, and TLI = 0.408. These outcomes collectively suggest that the measurement items of the variables are not substantially influenced by a common method factor, thereby instilling confidence in the interpretation of the study results.

Descriptive statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on all variables prior to hypothesis testing. As shown in Table 4, there was no significant correlation between employee prohibitive voice behavior and silence behavior (β = -0.005, p > 0.05). Illegitimate tasks were significantly and positively correlated with two negative emotions experienced by employees, namely boredom and anger, as well as with silence behavior, and prohibitive voice behavior (β = 0.425, p < 0.01; β = 0.469, p < 0.01; β = 0.381, p < 0.01; β = 0.216, p < 0.01). The specific negative emotion of boredom was significantly and positively correlated with silence behavior (β = 0.313, p < 0.01). The specific negative emotion of angry was significantly and positively correlated with prohibitive voice behavior (β = 0.160, p < 0.01). Job insecurity climate was significantly and negatively correlated with employee prohibitive voice behavior (β = −0.167, p < 0.01). These results provide preliminary support for the research hypotheses and offer a basis for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing

(1) Test of main effects and mediating effects. Given the construction of a multilevel model that accounts for both individual-level (level 1) and team-level (level 2) variables, multilevel regression analysis was conducted using HLM software to establish analytical models for hypothesis testing. As shown in Table 5, null models (Model 1, Model 4, Model 7, and Model 9) were created for employee silence behavior, prohibitive voice behavior, and the two negative emotions, boredom and anger. Following this, the “1-1-1” mediation model analysis procedure proposed by Zhang et al. (2009) was employed to test the hypotheses. To differentiate between within-group and between-group variations of illegitimate tasks and discrete negative emotions, both variables were group-mean centered, and the corresponding group means were included in the level-2 intercept as control variables.

According to the results from Model 2 and Model 5, illegitimate tasks exhibited significant within-group effects on employee silence behavior (Model 2, γ10 = 0.398, p < 0.001) and prohibitive voice behavior (Model 5, γ10 = 0.284, p < 0.001), respectively, thus providing support for H1 and H2. In Model 8 and Model 10, illegitimate tasks had significant within-group effects on discrete negative emotions, specifically boredom (Model 8, γ10 = 0.529, p < 0.001) and anger (Model 10, γ10 = 0.586, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H3. When both illegitimate tasks and the specific negative emotion of boredom were included in the model (Model 3), the within-group effect of boredom was significant (γ20 = 0.135, p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the effect of illegitimate tasks on employee silence behavior was still significant (γ10 = 0.319, p < 0.001), but the coefficient was significantly lower than in Model 2, indicating that boredom can mediated the positive effect of illegitimate tasks on employee silence behavior. Similarly, in Model 6, the within-group effect of angry was significant (γ20 = 0.127, p < 0.05), while the within-group effect of illegitimate tasks remained significant (γ10 = 0.213, p < 0.01), but the coefficient was significantly lower than in Model 5, indicating that angry mediated the positive effect of illegitimate tasks on employee prohibitive voice.

To further validate the robustness of the research findings, Monte Carlo simulations were employed to confirm the significance of the within-group mediation effects of discrete negative emotions. The results indicated that the within-group mediation effect of anger was significant in the relationship between illegitimate tasks and employee prohibitive voice behavior, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.003, 0.060]. Similarly, the within-group mediation effect of boredom was significant in the relationship between illegitimate tasks and employee silence behavior, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.010, 0.084]. Since both confidence intervals did not include zero, it can be concluded that the mediation effects of negative emotions were significant, thus providing support for hypotheses H4a and H4b.

(2) Test of moderating effects. To investigate the cross-level moderating effect of job insecurity climate, two-level models were constructed and analyzed using HLM, as presented in Table 6. For employee silence behavior, Model 11 was first built by introducing the Level-1 predictor, boredom, which was centered around the group mean. The results revealed that boredom significantly and positively predicted employee silence behavior (γ10 = 0.236, p < 0.001), explaining 10.2% of the within-group variance of silence behavior, while the between-group variance, τ00, remained significant. Subsequently, the Level-2 predictor, job insecurity climate, was introduced into Model 12, with the intercept as the outcome variable. The findings indicated that the effect of job insecurity climate was not significant, and the slope variance, τ11, also did not exhibit significance. To further explore the moderating effect of job insecurity climate, Model 14 was constructed. The results demonstrated that job insecurity climate did not significantly moderate the positive relationship between employee boredom and their silence behavior. Therefore, hypothesis H5a was not supported by the data.

A similar examination was conducted for employee prohibitive voice behavior. Model 14 was constructed by introducing the Level-1 predictor, anger, which was centered around the group mean. The results revealed that anger significantly and positively predicted employee prohibitive voice behavior (γ10 = 0.194, p < 0.01), explaining 14.1% of the within-group variance of prohibitive voice behavior, while the between-group variance, τ00, remained significant. Subsequently, the findings from Model 15 indicated that job insecurity climate significantly and negatively predicted employee prohibitive voice behavior (γ10 = -0.295, p < 0.001), and 16.1% of the between-group variance of prohibitive voice behavior could be explained by job insecurity climate. Moreover, the slope variance, τ11, remained significant (p < 0.01). Consequently, job insecurity climate was incorporated into the cross-level model with the slope as the outcome variable, resulting in Model 16. The results revealed that the interaction term significantly and negatively predicted employee prohibitive voice behavior (γ11 = -0.204, p < 0.01), indicating that job insecurity climate significantly moderated the relationship between employee angry and their prohibitive voice behavior, with a moderation effect of 26.5%, i.e., 26.5% of the slope variance could be explained by job insecurity climate. Therefore, Hypothesis H5b was supported.

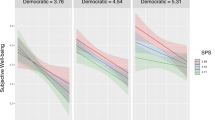

To further elucidate the negative moderating effect of job insecurity climate on the relationship between anger and prohibitive voice behavior, a simple slope analysis was conducted, and a moderation effect graph was plotted. As shown in Fig. 2, under a low job insecurity climate, the regression line between employee anger and prohibitive voice behavior was steeper, with a higher slope value (γ10 = 0.413, p < 0.05). However, under a high job insecurity climate, the positive effect of employee anger on prohibitive voice behavior was no longer significant (γ10 = 0.046, p > 0.1). These findings suggest that job insecurity climate negatively moderated the relationship between employee anger and prohibitive voice behavior, with the positive correlation being stronger under low job insecurity climate.

Discussion and conclusions

Through theoretical deduction and empirical analysis, this study examined the specific mechanism of the effects of illegitimate tasks on employee silence behavior and prohibitive voice behavior, and arrived at the following conclusions: First, illegitimate tasks are positively related to both employee silence behavior and prohibitive voice behavior. Second, discrete negative emotions, specifically anger and boredom, respectively mediate the positive relationship between illegitimate tasks and employee prohibitive voice behavior, as well as silence behavior. Third, the job insecurity climate negatively moderates the positive correlation between illegitimate task-induced angry and employee prohibitive voice behavior, while the moderating effect on the positive correlation between boredom and employee silence behavior is not statistically significant.

Empirical evidence suggests that illegitimate tasks not only increase employees’ prohibitive voice behavior but also trigger unfavorable silence behavior. Prohibitive voice behavior involves highlighting issues that impede efficiency and harm organizational operations, which can be perceived as challenging by managers and entail high risks (Li and Zhong 2020). Thus, a high-intensity driving mechanism is needed to encourage this behavior. Illegitimate tasks can serve as an external driving force for this mechanism by creating a sense of relative deprivation and unfairness among employees, leading to high motivational negative emotions, particularly anger. When employees experience strong anger towards their work and work environment, they are more likely to overcome psychological barriers and boldly challenge the status quo, pointing out issues in existing management practices and procedures. Therefore, illegitimate tasks can stimulate employees’ prohibitive voice behavior by arousing their anger.

Furthermore, illegitimate tasks have a significant positive predictive effect on employees’ silence behavior, which is consistent with previous research showing that illegitimate tasks reduce employees’ work motivation, resulting in a variety of negative work behaviors such as work withdrawal and deviance (Wang et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2022). Prohibitive voice behavior arises when employees break through their psychological defense lines and vent their dissatisfaction, while silence behavior is the “invisible” retaliatory behavior that employees adopt in response to illegitimate tasks. Under the passive negative emotions, particularly boredom, employees become indifferent to critical aspects of organizational operations and refrain from expressing views and suggestions that could promote organizational development, maximizing the preservation of their own resources to alleviate the psychological imbalance caused by undertaking illegitimate tasks.

In addition, this study reveals the attenuating effect of job insecurity climate on the relationship between employee anger and prohibitive voice behavior. When the job insecurity climate is high, employees perceive a threat to their job value and an increased risk of unemployment, resulting in a lack of motivation to take risks and a decreased willingness to challenge the status quo. Consequently, this hampers the generation and development of prohibitive voice behavior. However, the moderating effect of job insecurity climate on the relationship between boredom and silence behavior is not significant. This may be attributed to the nature of prohibitive voice behavior as an uncertain pressure response that employees use to seek resources in the context of resource loss pressure caused by illegitimate tasks. On the contrary, maintaining silence is an essential way for employees to prevent further loss of personal resources and ensure effective survival. Guided by the principle of resource conservation, illegitimate tasks may have a more stable correlation with employee silence. Additionally, influenced by the traditional Chinese value of “silence is golden,” employees tend to habitually remain silent. Silence behavior possesses more implicit characteristics compared to prohibitive voice behavior, suggesting that it reflects the complex psychological tendencies and multiple internal driving forces of employees. Consequently, silence behavior is less sensitive to changes in external environmental characteristics. Under the influence of illegitimate tasks, boredom serves as only one component of the driving mechanism behind silence behavior. Employees may exhibit silence behavior to seek emotional release and psychological balance, but this process is unaffected by the shared perception of job continuity within the team. In other words, the impact of job insecurity climate on employees may not be substantial enough to alter the extent to which employees are influenced by emotions like boredom and exhibit silence behavior.

Theoretical Implications

First, this study makes a valuable contribution to the existing literature by enhancing the understanding of the dependent variables of illegitimate tasks. Prior research has associated illegitimate tasks with intense negative behaviors among employees, such as counterproductive work behavior and work deviance. This study shifts its focus to the more subtle form of work negativity, the employee silence. Although less overt, employee silence can have significant detrimental effects on organizations. The study investigates the positive relationship between illegitimate tasks and the newly identified negative outcome, namely, silence behavior. Additionally, the research endeavors to broaden the understanding of illegitimate tasks by investigating whether they can also trigger employees to engage in prohibitive voice behavior, a behavior beneficial for organizational health. By investigating illegitimate tasks as negative work events that elicit discrete negative emotions in employees, leading to both prohibitive voice behavior and silence behavior, this study advances the theoretical framework of illegitimate task mechanisms and contributes to the expansion of knowledge in this domain.

Second, this study offers a more practical and innovative insight into the intricate relationship between workplace stressors and the dynamics of employee voice and silence, viewed through the lens of discrete negative emotions. While prior research extensively explored the determinants of employee voice and silence behaviors, there has been limited investigation into their interrelationship and common triggers, such as illegitimate tasks. Our research aims to address this gap by establishing a positive correlation between illegitimate tasks and both employee prohibitive voice and silence behaviors. This is based on the foundational understanding that prohibitive voice behavior and silence behavior are distinct constructs with no significant interconnections (Duan 2012; Sherf et al. 2021). This endeavor responds directly to the growing call for enhanced research on the combination of employee voice and silence (Chen and Tang 2019). Within the framework of affective event theory, we scrutinize the “negative & forceful” emotion of anger as a catalyst for prohibitive voice behavior and the “negative & passive” emotion of boredom as a facilitator of silence behavior. Our findings not only validate prior assertions regarding the dual impact of employees’ negative emotions on voice and silence behaviors (Duan 2012; Fu et al. 2012) but also provide a more fine-grained interpretation of the mechanisms underlying discrete negative emotions. In summary, our study enriches the existing literature by introducing discrete negative emotions as pivotal emotional mechanisms, thereby shedding light on the relationship between illegitimate tasks and employee voice-silence behavior.

Third, this study contributes to the ongoing research concerning the impact of job insecurity climate in the contemporary workplace. In response to the call made by Wang et al. (2020), our research explores the effects of situational factors on the consequences of illegitimate tasks. Specifically, we introduce job insecurity climate as a relevant cross-level moderator, a concept of increasing significance in today’s work environment. The post-pandemic era has led employees to become more aware of job insecurity, underscoring its importance. In this evolving landscape, our study identifies boundary conditions that influence the outcomes of illegitimate tasks and adds to the existing discourse on the impact of job insecurity climate. By examining employees’ decision-making inclinations regarding whether to voice their concerns or remain silent, and by acknowledging their heightened need for work continuity in the post-pandemic era, our research unveils a crucial facet—how job insecurity climate plays a pivotal role in influencing employees’ choices to engage in prohibitive voice behavior. In summary, our study sheds light on the evolving significance of job insecurity climate in the contemporary workplace and underscores its pivotal impact on employees’ decisions to speak up.

Practical Implications

In the current human-centered macro environment, there is increasing attention being paid to employee work stress and emotion management. This study attempts to reveal the causes of employees’ prohibitive voice behavior and silence behavior when facing illegitimate tasks as a source of stress from the perspective of emotional mechanisms. Based on the research findings, the following management implications are proposed:

First, organizations and managers need to acknowledge the various adverse effects of illegitimate tasks on employee work emotions and behaviors. On the one hand, organizations can assist in raising awareness among managers at all levels regarding the potential negative consequences of illegitimate tasks through various means, such as themed training and symposiums, and guide them to avoid issuing such tasks while carrying out their managerial responsibilities. On the other hand, managers themselves should exhibit proper behavior and refrain from imposing additional work burdens on employees based on their personal preferences. They should exercise prudence when it comes to resource allocation and task distribution, clarify job responsibilities, and prevent the intentional or unintentional imposition of illegitimate tasks on employees.

Second, managers should actively monitor and respond to employees’ emotional states. Upon observing negative emotions during work, managers should firstly reflect on whether they have assigned illegitimate tasks that contravene employees’ professional identities and role expectations. Secondly, managers should strengthen effective communication with employees through various means, such as face-to-face interviews, psychological counseling, and other methods, to comprehend their true thoughts and needs, timely address and mitigate negative emotions, and reduce the likelihood of employees exhibiting passive work behaviors, such as silence.

Third, organizations should endeavor to avoid the creation of a climate of high job insecurity within their teams. This can be achieved through the implementation of appropriate recruitment and screening procedures, the establishment of clear employment terms, the refinement of promotion and transfer regulations, and the scientific formulation of assessment and elimination criteria, thus providing employees with a reasonable level of job security. Furthermore, if individuals within the organization exhibit excessive job insecurity, they should be provided with appropriate stress management training to prevent the transmission of perceptions and experiences of impending job loss during interactions with other employees. This can help to prevent the spread of job insecurity within the work team, mitigate group panic and concern, and ultimately facilitate the emergence and development of employee prohibitive voice behavior.

Limitations and future research directions

Due to constraints in time and resources, this study has certain limitations that warrant further attention in future research. First, the use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to examine the dynamic effects of illegitimate tasks on employees’ negative emotions, prohibitive voice, and silence behaviors. Longitudinal studies with multi-source data collection methods could offer more robust evidence for causal relationships. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported measures may introduce common method bias, potentially affecting the validity of findings. Future research could mitigate this issue by employing diverse data collection methods, such as peer evaluations or objective performance metrics. Second, while the measurement of discrete negative emotions in this study is a conventional approach, it may not fully capture the dynamic and situational nature of emotions. Advanced methodologies, such as physiological measures or experience sampling techniques, could provide more nuanced insights into emotional responses to illegitimate tasks. Third, the research framework primarily examines the moderating role of team-level job insecurity climate. However, other contextual or individual-level factors, such as organizational culture, leadership style, or personality traits, may also influence employees’ responses. Expanding the framework to incorporate these boundary conditions could enhance understanding of the complexity of these relationships. Lastly, integrating cross-cultural perspectives could provide valuable insights into the manifestation and impact of illegitimate tasks in different cultural contexts. For example, in individualistic cultures, illegitimate tasks may be perceived as violations of autonomy, eliciting stronger negative emotions. Conversely, in collectivist cultures like China, hierarchical workplace structures and group harmony norms may exacerbate silence behaviors as a coping strategy. Comparative studies can illuminate these cultural nuances, thereby enriching the global understanding of illegitimate tasks.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmed SF, Eatough EM, Ford MT (2018) Relationships between illegitimate tasks and change in work-family outcomes via interactional justice and negative emotions. J Vocat Behav 104:14–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.002

Andrade C, Neves PC (2024) Illegitimate tasks and work-family conflict as sequential mediators in the relationship between work intensification and work engagement. Adm Sci 14(3):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14030039

Ashkanasy NM, Humphrey RH, Huy QN (2017) Integrating emotions and affect in theories of management. Acad Manage Rev 42(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0474

Baumeister RF, Vohs KD (2007) Self-Regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 1(1):115–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x

Belinda C, Melwani S, Kapadia C (2024) Breaking boredom: Interrupting the residual effect of state boredom on future productivity. J Appl Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001161

Bindl UK, Unsworth KL, Gibson CB et al. (2019) Job crafting revisited: Implications of an extended framework for active changes at work. J Appl Psychol 104(5):605–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000362

Breevaart K, Lopez Bohle S, Pletzer JL et al. (2020) Voice and silence as immediate consequences of job insecurity. Career Dev Int 25(2):204–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2018-0226

Chen LJ, Tang NY (2019) The antecedents and consequences of employee silence: a literature review and future prospects. Hum Resour Dev China 36(12):84–104. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.112822/c.2019.12.006

Chen S, Liu W, Zhang G et al. (2022) Ethical human resource management mitigates the positive association between illegitimate tasks and employee unethical behaviour. Bus Ethics Environ Respons 31(2):524–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12411

De Clercq D, Pereira R (2023) Unfair, uncertain, and unwilling: How decision-making unfairness and unclear job tasks reduce problem-focused voice behavior, unless there is task conflict. Eur Manage J 41(3):354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2022.02.005

Ding H, Kuvaas B (2023) Illegitimate tasks: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Work Stress 37(3):397–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2022.2148308

Duan JY (2012) A study of the relationships between employee voice and employee silence: a nomological network perspective. Nankai Bus Rev 15(4):80–88

Dyne LV, Ang S, Botero IC (2003) Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J Manage Stud 40(6):1359–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00384

Fila MJ, Eatough E (2020) Extending the boundaries of illegitimate tasks: The role of resources. Psychol Rep 123(5):1635–1662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119874292

Fila MJ, Semmer NK, Kern M (2023) When being intrinsically motivated makes you vulnerable: illegitimate tasks and their associations with strain, work satisfaction, and turnover intention. Occup Health Sci 7:189–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00140-w

Fisher CD (1993) Boredom at work: A neglected concept. Hum Relat 46:395–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600305

Fu Q, Duan JY, Tian XM (2012) The emotion mechanism of employee voice behavior: A new exploratory perspective. Adv Psychol Sci 20(2):274–282

Gkorezis P, Kastritsi A (2017) Employee expectations and intrinsic motivation: work-related boredom as a mediator. Employee Relat 39(1):100–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2016-0025

Halbesleben JR, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC et al. (2014) Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manag 40:1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hao L, Zhu H, He Y et al. (2022) When is silence golden? A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of employee silence. J Bus Psychol 37:1039–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09788-7

Harju LK, Seppälä P, Hakanen JJ (2023) Bored and exhausted? Profiles of boredom and exhaustion at work and the role of job stressors. J Vocat Behav 144:103898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103898

Harju LK, Van Hootegem A, De Witte H (2022) Bored or burning out? Reciprocal effects between job stressors, boredom and burnout. J Vocat Behav 139:103807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103807

He X, Zheng Y, Wei Y (2024) The double-edged sword effect of illegitimate tasks on employee creativity: positive and negative coping perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag 17:485–500. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S444960

Hellgren J, Sverke M (2003) Does job insecurity lead to impaired well-being or vice versa? Estimation of cross-lagged effects using latent variable modeling. J Organ Behav 24:215–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.184

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP et al. (2018) Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 5:103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hsieh HH, Kao KY (2021) Beyond individual job insecurity: A multilevel examination of job insecurity climate on work engagement and job satisfaction. Stress Health 38:119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3082

Hsiung HH, Tsai WC (2017) The joint moderating effects of activated negative moods and group voice climate on the relationship between power distance orientation and employee voice behavior. Appl Psychol 66:487–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12096

HUMAINE Association (2006) Humaine emotion annotation and representation language (EARL): Proposal. http://emotion-research.net/projects/humaine/earl/proposal

Ilies R, Bono JE, Bakker AB (2024) Crafting well-being: employees can enhance their own well-being by savoring, reflecting upon, and capitalizing on positive work experiences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 11:63–91. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-110721-045931

Jiang F, Wang Z (2024) Craft it if you cannot avoid it: job crafting alleviates the detrimental effects of illegitimate tasks on employee health. Curr Psychol 43:7924–7935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04958-7

Jordan PJ, Troth AC, Ashkanasy NM et al (2020) The Antecedents and Consequences of Fear at Work. In: Yang L-Q, Cropanzano R, Daus CS, Martínez-Tur V, eds. The Cambridge handbook of workplace affect. Cambridge handbooks in psychology. Cambridge University Press, p 402–413

Kashif M, Gürce MY, Tosun P et al. (2020) Supervisor and customer-driven stressors to predict silence and voice motives: mediating and moderating roles of anger and self-control. Serv Mark Q 41:273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2020.1786247

Khattak MN, Khan MB, Fatima T et al. (2019) The underlying mechanism between perceived organizational injustice and deviant workplace behaviors: moderating role of personality traits. Asia Pac Manag Rev 24:201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2018.05.001

Kiewitz C, Restubog SLD, Shoss MK et al. (2016) Suffering in silence: investigating the role of fear in the relationship between abusive supervision and defensive silence. J Appl Psychol 101:731–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000074

Kilponen K, Huhtala M, Kinnunen U et al. (2021) Illegitimate tasks in health care: Illegitimate task types and associations with occupational well-being. J Clin Nurs 30:2093–2106. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15767

Kirrane M, O’shea D, Buckley F et al. (2017) Investigating the role of discrete emotions in silence versus speaking up. J Occup Organ Psychol 90:354–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12175

Koçak ÖE, Ünal ZM (2022) Task assignments matter: the relationship between illegitimate tasks, work engagement and silence. Int J Work Organ Emot 13:330–349. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2022.127656

Lahti H, Kalakoski V (2024) Work stressors and their controllability: content analysis of employee perceptions of hindrances to the flow of work in the health care sector. Curr Psychol 43:639–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04328-3

Lam CF, Rees L, Levesque LL et al. (2018) Shooting from the hip: a habit perspective of voice. Acad Manag Rev 43:470–486. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0366

Låstad L, Näswall K, Berntson E et al. (2018) The roles of shared perceptions of individual job insecurity and job insecurity climate for work- and health-related outcomes: A multilevel approach. Econ Ind Democr 39:422–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X16637129

Lebel RD (2017) Moving beyond fight and flight: A contingent model of how the emotional regulation of anger and fear sparks proactivity. Acad Manag Rev 42:190–206. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0368

Li FJ, Zhong XP (2020) The distinction between promotive and prohibitive voice. Adv Psychol Sci 28:1939–1952

Li PB, Chen T, Huang ZX et al. (2024) The influence mechanism of illegitimate tasks on work withdrawal behavior among hotel employees: a moderated chain mediation model. Tourism Science 4:99–118. https://doi.org/10.16323/j.cnki.lykx.2024.04.002

Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh JL (2012) Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manag J 55:71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Lin SH, Johnson RE (2015) A suggestion to improve a day keeps your depletion away: examining promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors within a regulatory focus and ego depletion framework. J Appl Psychol 100:1381–1397. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000018

Liu F, Li J, Lan J et al. (2024) Linking perceived overqualification to work withdrawal, employee silence, and pro-job unethical behavior in a Chinese context: the mediating roles of shame and anger. Rev Manag Sci 18:711–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00619-y

Lu S, Sun Z, Huang M (2024) The impact of digital literacy on farmers’ pro-environmental behavior: an analysis with the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front Sustain Food Syst 8:1432184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1432184

Mäkikangas A, Minkkinen J, Muotka J et al. (2023) Illegitimate tasks, job crafting and their longitudinal relationships with meaning of work. Int J Hum Resour Manag 34:1330–1358. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1987956

Miao Q, Pan C, Schwarz G (2024) Revisiting the impact of illegitimate tasks on volunteers: Does emotional labor make a difference? VOLUNTAS: Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Organ 35(5):1006–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-024-00670-7

Morrison EW (2023) Employee voice and silence: Taking stock a decade later. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 10:79–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-054654

Munir H, Jamil A, Ehsan A (2017) Illegitimate tasks and their impact on work stress: the mediating role of anger. Int J Bus Soc 18(S3):545–566

Muñoz Medina F, Lopez Bohle S, Jiang L et al. (2023) Qualitative job insecurity and voice behavior: evaluation of the mediating effect of affective organizational commitment. Econ Ind Democracy 44(4):986–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X221101655

Nyfoudi M, Kwon B, Wilkinson A (2024) Employee voice in times of crisis: a conceptual framework exploring the role of human resource practices and human resource system strength. Hum Resour Manag 63(4):537–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22214

Omansky R, Eatough EM, Fila MJ (2016) Illegitimate tasks as an impediment to job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation: moderated mediation effects of gender and effort-reward imbalance. Front Psychol 7:1818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01818

Ouyang C, Ma Z, Ma Z et al. (2023) Research on employee voice intention: conceptualization, scale development, and validation among enterprises in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag 16:2137–2156. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S414623

Ouyang C, Zhu Y, Ma Z et al. (2022) Why employees experience burnout: an explanation of illegitimate tasks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(15):8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923

Pahng PH, Kang SM (2023) Voice vs. silence: the role of cognitive appraisal of and emotional response to stressors. Front Psychol 14:1079244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1079244

Pekrun R (2006) The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ Psychol Rev 18(4):315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Peltokorpi V, Allen DG (2024) Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. J Organ Behav 45(3):416–433. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2728

Pindek S, Demircioğlu E, Howard DJ et al. (2018) Illegitimate tasks are not created equal: examining the effects of attributions on unreasonable and unnecessary tasks. Work Stress 33(3):231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1496160

Pinder CC, Harlos KP (2001) Employee silence: quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. Res Pers Hum Resour Manage 20:331–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(01)20007-3

Qiu L, Zheng X, Wang YF (2008) Revision of the positive affect and negative affect scale. Chin J Appl Psychol 14(3):249–254+268

Schulte-Braucks J, Baethge A, Dormann C et al. (2019) Get even and feel good? Moderating effects of justice sensitivity and counterproductive work behavior on the relationship between illegitimate tasks and self-esteem. J Occup Health Psychol 24(2):241–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000112

Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL et al. (2015) Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work Stress 29(1):32–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.1003996

Semmer NK, Tschan F, Meier LL et al. (2010) Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behavior. Appl Psychol 59(1):70–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00416.x

Shaya N, Mohebi L, Pillai R et al. (2024) Illegitimate tasks, negative affectivity, and organizational citizenship behavior among private school teachers: A mediated–moderated model. Sustainability 16(2):733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020733

Sherf EN, Parke MR, Isaakyan S (2021) Distinguishing voice and silence at work: Unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Acad Manag J 64(1):114–148. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1428

Sora B, Caballer A, Peiro JM et al. (2009) Job insecurity climate’s influence on employees’ job attitudes: Evidence from two European countries. Eur J Work Organ Psy 18(2):125–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320802211968

Sora B, De Cuyper N, Caballer A et al. (2013) Outcomes of job insecurity climate: The role of climate strength. Appl Psychol 62(3):382–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00485.x