Abstract

Illicit personal information trading, a hallmark of internet dark and gray industries, has deeply infiltrated the global criminal economic system, serving as a critical driver and “raw material factory” for numerous offenses. This study focuses on its role as the core enabler of China’s telecom fraud criminal ecosystem, revealing its systemic characteristics and multi-dimensional evolutionary patterns, with significant theoretical and practical implications. Utilizing telecom fraud case data and anonymous network transaction data, this research employs analytical description and Event Logic Graph (ELG) to systematically uncover the operational mechanisms and evolutionary rules of illicit personal information trading. The findings demonstrate a pronounced “data capitalization” feature within this trade, empirically validating the cybercrime economics law of “data-as-criminal-capital”. The constructed “communication-fund flow-transaction” evolution model reveals a paradigm shift from traditional tool reliance to technology-driven operations: communication modes migrated from traditional channels to hybrid Telegram API and Tor+Signal architectures; fund flow evolved from fiat cash to USDT mixing and money laundering via “Pao Fen” platforms; transaction models upgraded from bulk sales to “customized subscription” services. This illicit trade has matured into an industrialized division of labor: upstream actors steal full-lifecycle data via automated scripts; midstream processes and packages standardized data products; downstream legitimizes criminal proceeds through diverse money laundering methods. This research not only deepens the understanding of cybercrime economics but also, by uncovering the evolutionary pathways of the criminal ecosystem and its industrial chain structure, provides crucial theoretical foundations and practical targets for formulating targeted governance strategies and building a global collaborative regulatory framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s contemporary Internet landscape has undergone a profound technological metamorphosis, characterized by synergistic innovations in artificial intelligence, distributed ledger technologies, and ubiquitous computing infrastructure. This digital leapfrogging has precipitated a paradigm shift in technological architectures and application ecosystems, catalyzing unprecedented expansion of digital economic activities. China’s digital economy has demonstrated sustained exponential growth since 2014, with a compound annual growth rate exceeding 15%. Empirical data from the 53rd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China reveal a networked population of 1.092 billion individuals, representing 77.5% penetration and a year-on-year growth of 24.8 million users (CNNIC, 2023). This digital saturation has facilitated the complete integration of cyber-physical systems into quotidian socioeconomic activities, from educational platforms to financial technologies.

Concomitantly, this rapid digitization has engendered a parallel shadow economy exhibiting increasing sophistication. The cyber-underground now features specialized markets, including personal information commodification, automated fraud-as-a-service platforms, blockchain-based money laundering solutions, and AI-enhanced social engineering toolkits (Tang et al. 2022). These illicit ecosystems demonstrate remarkable adaptive capabilities, with attack vectors evolving through continuous technical iteration. Current manifestations include polymorphic malware targeting financial infrastructures and AI-generated synthetic identities for fraudulent applications. As Sharma, Sharma (2024) document, this has crystallized into a fully articulated value chain encompassing data harvesting, attack orchestration, and value extraction—what Interpol classifies as “Cybercrime 3.0” infrastructure (Luo, 2023).

Telecommunication fraud (hereinafter referred to as telecom fraud) is a prominent manifestation within this illicit ecosystem. It is defined as a form of cybercrime in which perpetrators use telecommunication networks (such as phone calls, text messages, social media, or internet-based communication platforms) and information technology to impersonate legitimate entities (e.g., government agencies, financial institutions, service providers) or fabricate scenarios. The deliberate intent is to deceive victims into voluntarily transferring funds or divulging sensitive personal and financial information for illicit financial gain.

Notably, telecom fraud and its associated illicit personal data trade have emerged as particularly pervasive and emblematic manifestations within this illicit ecosystem (Cecelia and Hossein, 2021). There exists a significant causal relationship between telecom fraud and illicit personal information trading. The illicit trade of personal data provides critical support for telecom fraud, serving as a key tool for criminals to carry out scams. It can be said that telecom fraud and personal information leakage are mutually reinforcing. On one hand, the illegal acquisition and trade of personal information enable precise targeting for telecom fraud. On the other hand, the high profits from fraud incentivize criminals to continue obtaining and trading personal data illegally.

Criminals acquire personal information through various illicit means (such as selling, scraping, and stealing), then use this data to conduct targeted fraud. For instance, they analyze personal information to create detailed user profiles and employ specialized scripts to execute scams. Telecom fraud has evolved into an “industrial chain” centered around personal information trading, encompassing illegal data trading, fraud implementation, and subsequent money laundering. These components are closely interconnected, forming an extensive criminal network.

The illicit trade of personal information has emerged as one of the most pervasive and damaging manifestations within China’s internet black and gray markets. Recent years have witnessed an alarming escalation in both the scale and sophistication of personal data breaches, reflecting the maturation of a fully-fledged underground economy. This phenomenon is exemplified by several high-impact incidents: the June 2022 compromise of “Chaoxing Study” platform resulted in the exfiltration of over 170 million user credentials, including comprehensive registration details that were subsequently monetized on dark web marketplaces. Similarly, the August 2022 breach of Shanghai’s “SS Code” municipal service application exposed 48.5 million resident profiles containing sensitive personally identifiable information (PII) such as national ID numbers, contact details, and residential histories. Perhaps most staggering was the February 2023 exposure of 4.5 billion data records (435.35 GB) aggregated from major e-commerce and logistics platforms, enabling the reverse identification of individuals through simple telephone number queries.

The continued vulnerability of critical systems was further demonstrated by the July 2023 breach of Renmin University’s student database and the November 2023 leak of a domestic e-commerce platform’s transaction records, collectively exposing millions of additional sensitive records including biometric data, academic information, and financial documents. These incidents collectively illustrate the industrial-scale operation of personal data exploitation networks, with compromised information serving as the foundational currency for subsequent fraudulent activities.

The illicit personal information industry’s transition from peripheral activity to institutionalized criminal enterprise presents multifaceted challenges to China’s digital governance framework. Three primary obstacles hinder effective regulation: legislative ambiguity regarding emerging technologies, evidentiary complexities in digital forensic investigations, and jurisdictional limitations in cross-platform enforcement. These systemic vulnerabilities have allowed the illicit personal information ecosystem to flourish, generating significant threats to individual privacy rights (through identity theft and financial fraud), economic security (via illicit transactions estimated at ¥50 billion annually), and national stability (through the erosion of public trust in digital infrastructure) (Ming, 2019).

This study addresses critical gaps in understanding the operational symbiosis between illicit personal information trading and telecom fraud by focusing on the former as the core enabler of China’s telecom fraud criminal ecosystem. It aims to achieve three primary objectives:(1) Empirically validate the causal relationship between illicit personal information trading and telecom fraud through data analysis (case data + dark web transaction data); (2) Systematically model the evolutionary mechanisms of this illicit ecosystem across communication, transaction, and fund flow dimensions (2013–2022); (3) Deconstruct its industrial chain structure using event-based knowledge graphs.

The manuscript is organized as follows: The ”Methods” section systematically elaborates the research methodology, specifically covering the data collection and the analytical methods employed; The “Results” section presents key findings derived from quantitative and qualitative analyses, revealing the model characteristics and evolution rules of illicit personal information trading as the underlying support for telecom fraud; The “Discussion” section unfolds from the dual dimensions of academic value and practical significance, deeply analyzing the internal logic of illicit personal information trading as the core driving force of telecom fraud, and discussing its technology-driven industrialization characteristics and the division of labor pattern in the upstream, midstream, and downstream industrial chains; The “Conclusion” section summarizes the key contributions, acknowledges its limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

Literature review

The literature relevant to this study can be categorized into two core areas essential for understanding the illicit personal information ecosystem underpinning telecom fraud: (1) the symbiotic relationship between telecom fraud and illicit personal information trading, and (2) the evolutionary dynamics of illicit personal information trading itself, encompassing channels, transaction patterns, and criminal roles.

The symbiotic relationship between telecom fraud and illicit personal information trading

Telecom fraud is widely recognized as a complex and highly damaging systemic crime. Criminals leverage modern communication technologies and online platforms to establish comprehensive operational chains involving information acquisition, fraud planning, and fund transfers. Tactics include impersonating authorities (e.g., government agencies, financial institutions) via fraudulent communications (SMS, calls, social media) to exploit psychological vulnerabilities (fear, greed, information asymmetry) and induce rapid victim fund transfers (Li, 2023; Luo, 2023; Sun, 2023). The rapid development of ICT and imperfect cyber governance frameworks provides both the technical means and operational space for these crimes (Wang et al., 2023).

Crucially, the illegal acquisition and trade of personal information serve as the fundamental enabler and prerequisite for effective telecom fraud. Criminals obtain vast quantities of personal data (names, IDs, contact details, financial info) through cyber intrusions, phishing, and insider leaks (Tang et al., 2022; Wang, 2023). This data enables highly targeted scams (“precision profiling”), significantly increasing success rates by lowering victim vigilance—for instance, 80% of bank impersonation fraud victims were deceived due to prior information leaks (Li, 2021; Zhang, 2022). Personal information black markets provide continuous resources, creating a vicious cycle where fraud fuels demand for more data, and readily available data enables more fraud (Cheng and Wu, 2023). Information asymmetry stemming from data leaks and the misuse of communication technologies forms the core technical foundation for telecom fraud proliferation, highlighting the need for stronger data protection legislation (Xie et al., 2022).

Illicit personal information trading is thus identified as the core driver of telecom fraud. It provides precise targeting capabilities and reduces criminal costs through gray market technologies, establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of “data leakage → fraud execution → money laundering” (Fu, 2024). Examples include fraudsters purchasing social media data to fabricate trust relationships (boosting “romance scam” success by 40%) (Namnouvong, 2024), hackers stealing data via “man-in-the-middle” attacks on corporate databases to feed fraud syndicates (Zhou, 2023), and the open pricing of personal data (e.g., US SSNs for ~$5) on dark web markets facilitating identity theft for further crimes (David and Nuno, 2021). Critically, 60% of globally disclosed data breaches in 2022 were telecom fraud-related, and dark web “data service” transactions exceeding $1 billion annually directly fund telecom fraud activities (Maria, 2019; Mazi et al. (2020); FATF-Interpol-Egmont Group, 2023).

While prior studies have documented the symbiosis between personal data trading and telecom fraud (Zhang, 2022; Chen et al., 2023), critical gaps persist: Limited empirical analysis of the criminal evolutionary patterns (e.g., technology-driven shifts in money laundering); Absence of computational models capturing dynamic interactions across the fraud value chain. This research addresses these gaps by: (1) Integrating multi-source heterogeneous data (case records + dark web transactions) to construct an ELG-based evolutionary model; (2) Quantifying the “data capitalization” effect through tripartite metric analysis (commodity-vendor-transaction); (3) Revealing the industrial division of labor via upstream-midstream-downstream criminal typologies.

Evolution of illicit personal information trading: channels, patterns, and roles

The illicit personal information trade has evolved significantly in sophistication, forming a complex criminal ecosystem with distinct patterns and roles.

Channel evolution

Trading channels have diversified significantly, moving from offline forums and traditional black markets towards encrypted and anonymous platforms. The dark web has become a primary venue, facilitating anonymous transactions with high investigation difficulty and substantial unrecorded crime (Zhang, 2022; Chen, 2023). Over 50 types of sensitive personal information are openly traded on dark web forums (Chen et al., 2023). Furthermore, the rise of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology has integrated money laundering directly into the trading closed-loop. Illegal payment platforms (money-laundering platforms, “Pao Fen” platforms) and cryptocurrencies (like Bitcoin, USDT) are now dominant channels for obscuring financial trails, with 60% of 2022 global data breach transactions utilizing dark web/crypto channels (Lukas et al., 2021; Wang, 2023; Fu, 2024).

Transaction pattern evolution

The market has shifted from fragmented, ad-hoc sales towards industrialized integration and service orientation. Transaction models evolved from “bulk sales” to “scenario-based applications” and “precision profiling,” integrating diverse data sources (consumption, location) to build victim profiles for customized fraud targeting (Zhang, 2022; Mao and Dong, 2023). Concurrently, data sourcing transitioned from exploiting single leaks to proactive, multi-dimensional collection (e.g., credential stuffing, database dumps, web crawlers) (Chen et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2023). A prevalent hybrid model combines “compliant” data (public directories) with illegal data (stolen IDs) to create gray data packages that evade regulatory definitions (Tang et al., 2022). Technology-driven mass theft (malware, MITM attacks, automated crawlers) is now the primary acquisition method (Zhou, 2023), while insider threats remain significant (35% of leaks in sectors like aviation/logistics) (Ming, 2019).

Criminal role specialization and network evolution

A sophisticated division of labor characterizes the trade, forming an extensive criminal network. Upstream (resource layer): Individuals with technical expertise (hackers, tool developers) providing data and tools via attacks, malware, or exploiting vulnerabilities/infrastructure (Yuan et al., 2018; Zhang and Jiang, 2023). Midstream (service/processing layer): Actors involved in data processing (cleaning, desensitization, categorization—e.g., obscuring partial IDs), packaging standardized data products (e.g., social engineering databases), and facilitating transactions (e.g., “data brokers”) (Threat Hunter, 2024; Qi et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2022). Downstream (monetization layer): Criminal groups utilizing the data for fraud execution (telecom fraud syndicates) and laundering the proceeds through complex methods (bank card layering, third/fourth-party payments, crypto mixing, shell companies) (Zhang and Jiang, 2023; Yu et al., 2024).

Criminal networks have evolved from localized operations to transnational collaboration, forming a global division of labor: “technology developers - data suppliers - fraud executors—money launderers.” Examples include Southeast Asian groups establishing global distribution via Telegram and Northern Myanmar groups outsourcing AI tool development (Yu, 2021; Chen, 2023; Namnouvong, 2024). Criminal legal evasion strategies have also escalated, exploiting multinational data interfaces and regulatory gaps (e.g., mixing legal/illegal data to circumvent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)) and leveraging ambiguities in laws (e.g., prosecution thresholds in China) (Zhao, 2022; Huang, 2022; Lei, 2024).

Comparative analysis reveals distinct advancements in criminal tactics

Whereas early studies identified basic data trading on forums, recent works confirm the rise of AI-optimized “customized subscription” services (Vu et al., 2020). Similarly, traditional cash-based money laundering has been supplanted by cryptocurrency mixing—a shift quantified in this study through USDT transaction analysis (Interpol, 2023; Calafos and Dimitoglou, 2023).

This body of literature establishes the critical, symbiotic link between illicit personal information trading and telecom fraud, positioning the former as the essential fuel and enabler of the latter. It further documents the significant evolution of the illicit data trade towards industrialized, service-oriented models operating through encrypted channels (dark web, crypto) with sophisticated transnational networks and specialized roles. This evolutionary context - particularly regarding communication channels, fund flows (including laundering), transaction models, and criminal organization - provides the essential foundation for interpreting the findings of the present study on the operational mechanisms and evolutionary patterns of this illicit ecosystem.

Methods

Data

The overwhelming majority of illicit personal information trading activities involve cybercrime. Scholars in cybercrime research generally acknowledge that the lack of standardized legal definitions for cybercrime and the absence of effective, reliable official statistics make it challenging to accurately assess the prevalence or incidence of cybercrime globally (McGuire, 2012). Although law enforcement agencies in some countries do collect cybercrime data (e.g., police records and court verdicts), such official data inevitably suffer from underreporting and incomplete documentation (Bossler et al., 2020). This has prompted researchers to turn to alternative data sources for measuring cybercrime, including online transaction forums and cybersecurity firm datasets (Chen et al., 2024).

Illicit personal information trading data are characterized by high sensitivity, fragmentation, and strong anonymity, involving privacy-sensitive information (e.g., biometrics, financial data) traded in batches via dark web markets and encrypted communications, with cryptocurrency used to obscure financial flows. Key challenges in data collection include highly dispersed data(cross-platform, multi-layered resale), technologically adversarial environments (anti-crawling measures, dynamic encryption), and cross-border tracing difficulties (complex judicial coordination, anonymized identity attribution), necessitating integrated multi-source intelligence correlation and legally compliant forensic techniques to overcome barriers (citation needed). Among these data sources, technical datasets—such as crawled data, dynamically encrypted data, intrusion logs, and system logs—are frequently employed as proxy indicators across multiple dimensions of cybercrime and dominate macro-level cybercrime research literature (Loggen et al., 2024; Huang and Deng, 2023).

However, due to the anonymity and virtuality of cyberspace, cybercrime transcends national borders and jurisdictional boundaries, leveraging distributed controlled computers as platforms for illicit personal information trading. Techniques such as proxy servers, anonymous networks (e.g., Tor), virtual private networks (VPNs), and the widespread use of social media apps further complicate the statistical tracking and forensic attribution of such crimes, let alone undetected offenses (Huang and Deng, 2023). While some studies infer illicit personal information trading through related internet black market research, more granular and comprehensive empirical analyses remain scarce.

The data in this study primarily originate from two sources. The first comprises 3,080 telecom fraud case records obtained from the Criminal Investigation Specialized System and Anti-Fraud Platform on the public security internal network of Xiasha District, Zhejiang Province, covering the period from 2013 to 2022. These records include interrogation data (e.g., dialogs between victims and perpetrators, aimed at identifying the types of personal information obtained by criminals) and investigation data (e.g., tracing perpetrators’ methods of contacting victims, such as social media, emails, or phishing websites).

The second category of data comprises 53,100 entries crawled from two Chinese-language dark web platforms: “Dark Web Chinese Marketplace” and “Chang’an Nightless City”. These anonymous platforms, targeting Chinese-speaking users, host extensive illicit trade listings, predominantly involving illicit personal information transactions. These data include fields such as sellers, product titles, product descriptions, US dollar pricing, Bitcoin pricing, transaction volume, and customer reviews.

Analytical descriptive approach

This study employs an analytical descriptive approach (Blei and Lafferty, 2009; Wolniak, 2023) to systematically analyze the operational mechanisms and evolutionary patterns of the personal information black/gray industry chain through the lens of telecom fraud crimes.

Initially, within the descriptive research module, the study investigates the functional role of illicit personal information transactions in criminal supply chains. Through the mining and analysis of case data and dark web transaction data, this research identifies three core functions of illicit personal information transactions in telecom fraud ecosystems.

Subsequently, in the analytical research module, the study explores dynamic evolutionary models of illicit personal information transactions. By applying topic modeling and the temporal sequence analysis method (Chen et al., 2022) to conduct multidimensional modeling of longitudinal crime data spanning 2013–2022, focusing on three evolutionary dimensions: (1) Communication pattern evolution; (2) Transactional modality evolution; (3) Funds flow evolution.

Topic modeling

The implementation workflow of the topic modeling in this study is as follows:

-

Text preprocessing

Tokenization of case transcripts and dark web commodity descriptions (using the Jieba tokenizer).

Stopword filtering (augmented with a criminal investigation terminology stoplist).

Using the NLTK library in Python for lemmatization to reduce noise, lower dimensionality, and enhance topic consistency, thereby improving the performance and efficiency of the model.

-

Hyperparameter tuning

Optimal number of topics (K = 12) determined via perplexity and coherence score evaluation (search range: K = 5–20).

Dirichlet priors: α = 0.1, β = 0.01.

-

Model training

Trained using the Gensim library for 1000 iterations with a convergence threshold of 1e−5.

Extracted top 20 salient terms per topic.

Temporal sequence analysis

Temporal sequence analysis models, mines and forecasts event or state sequences ordered in time, uncovering temporal dependencies and evolutionary laws to portray system dynamics. Temporal sequence analysis models the evolving timing and ordering of cyber-criminal actions to reveal how illicit infrastructures, attack flows and money-laundering chains adapt over time; by mining these temporal patterns across dark-web markets, phishing campaigns and blockchain transactions, defenders can forecast the next tactics or cash-out points and interdict emerging black-gray ecosystems before they scale. This paper’s temporal sequence analysis workflow for the black-and-gray industry proceeds as follows.

-

Phase segmentation

Divided the period 2013–2022 into three intervals: T1 (2013–2015), T2 (2016–2018), T3 (2019–2022).

-

Feature quantification

Tool usage rate: Calculated as the ratio of cases using a specific tool in a given interval to total cases (e.g., telephone/text message usage rate: 91% in T1). and then calculate the technological generational nigration index.

Event Logic Graph approach

An Event Logic Graph (ELG) is a knowledge base of event logic that describes the evolutionary patterns and mechanisms between events (Li et al., 2023; Natthawut and Ryutaro, 2018). The primary purpose of employing ELG in this study is threefold: (1) To model causal-temporal dynamics of criminal activities by formalizing event sequences (e.g., “data theft → dark web transaction → money laundering”) that traditional statistical methods cannot capture; (2) To identify critical leverage points in illicit ecosystems by quantifying relationship weights (e.g., transition probabilities between fraud implementation and fund laundering events); (3) To enable predictive analysis of criminal adaptation patterns through graph-based inference (e.g., simulating impacts of regulatory interventions on transaction evolution).

Structurally, an ELG is a directed cyclic graph where nodes represent events, and directed edges denote logical relationships between events, including temporal succession, causality, conditionality, and hypernymy-hyponymy relations. By integrating the nature, characteristics, and dynamics of illicit personal information trading, event extraction and event relation extraction techniques can construct an ELG for illicit personal information transactions from case data and web-crawled datasets, particularly focusing on three core patterns: “Data transfer patterns,” “Interaction communication patterns,” and “Fund flow patterns,” thereby enabling advanced analysis of their evolutionary mechanisms and lifecycle (Chen et al., 2024).

As a symbolic representation tool for dynamic event evolution, the theoretical framework of ELG is rooted in cognitive linguistics and complex systems theory, using structured knowledge bases to reveal temporal correlations, causal laws, and conditional constraint networks among events (Zhao, 2022). As a novel knowledge representation method in knowledge engineering, ELG emphasizes the construction of event evolution networks with temporality, causality, and logical relevance.

Unlike static knowledge graphs, ELGs capture evolutionary mechanisms through directed edges annotated with transition probabilities. Its technical architecture comprises a node set (E = {e_1, e_2, …, e_n}) and a directed edge set (R = {r_1, r_2, …, r_m}), forming a directed cyclic graph with dynamic evolution features. Nodes represent event entities (e.g., “data theft,” “information resale”), while edge attributes are quantified through binary tuples <relationship type, transition probability > to formalize logical relationships such as succession, causality, conditionality, and hypernymy. Compared to traditional knowledge graphs, ELG demonstrates unique advantages in temporal modeling, evolutionary inference, and situational prediction (Li et al., 2023).

Topologically, ELG manifests as a directed cyclic complex network: nodes represent semantically independent event entities (e.g., “data breach,” “illegal transaction”), and directed edges encode multi-level inter-event relationships via predicate logic, including succession (“data collection → cleansing”), causality (“vulnerability exploitation → system intrusion”), conditionality (“dark web platform existence → black-market activity”), and hypernymy (“phishing attacks ⊂ social engineering techniques”) (Pharris and Perez-Mira, 2023; Liao et al., 2022). For illicit personal information trading, ELG construction based on multi-source heterogeneous data (case records, dark web marketplace data) prioritizes three core patterns: (1) Data Transfer Patterns: Chain evolution paths from data theft (e.g., malware implantation) to intermediary resale (e.g., dark web forum transactions) and data cleansing (e.g., anonymization); (2) Interaction Communication Patterns: Criminal group communications via traditional tools, niche social apps, C2 server architectures (e.g., P2P dynamic proxies), encrypted protocols (e.g., Telegram API), and anti-detection tactics (e.g., IP spoofing); (3) Fund Flow Patterns: Cross-border financial pathways involving cash payments, third-party platforms, cryptocurrency mixing (e.g., CoinJoin), and shell company laundering (e.g., offshore account layering) (Shubhdeep and Sukhchandan, 2020; Chen et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2021).

In this study, to establish traceable connections between methodology and findings, the ELG was constructed through four validated stages:

-

Event extraction: From telecom fraud cases (N = 3080) and dark web transactions (N = 53,100), we identified core events using semantic role labeling (e.g., “data theft”, “cryptocurrency payment”) with >92% F1-score in pilot testing.

-

Relationship annotation: Subject matter experts labeled temporal/causal relationships between events (e.g., “phishing → credential capture”) using Cohen’s k = 0.81 inter-rater reliability threshold.

-

Graph assembly: Events became nodes; annotated relationships formed directed edges weighted by transition probability P calculated from case co-occurrence frequency.

-

Validation: The ELG’s precision was verified against 200 ground-truth investigator reports (recall=0.87, precision=0.91).

The methodology flowchart of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Results

Underlying illicit personal information transactions fuel telecom fraud

Based on the telecom fraud case data (N = 3080 cases), and through LDA topic modeling, high-frequency word clusters were identified, combined with co-occurrence network semantic mining, to uncover the semantic features and thematic distribution patterns of illicit personal information trading crimes. Word cloud visualization revealed that high-frequency terms were clustered around core concepts, including “data breach” (term frequency density: 23.7%), “dark web transactions” (18.2%), and “social engineering databases” (12.4%). The semantic network exhibited the strongest co-occurrence triad as “data theft → dark web forums → cryptocurrency payments” (pointwise mutual information, PMI = 3.21, p < 0.001), validating the tripartite structure (“resource acquisition → transaction facilitation → fund circulation”) of the criminal chain.

ELG of personal information trading

Applying the methodology described in the “Method” section, we derived the full-chain event logic graph through systematic analysis of telecom fraud cases and dark web data. Key construction metrics include:

-

□•78 core event nodes extracted (e.g., “Data Pricing”, ‘Telegram API Communication’)

-

□•214 causal relationships identified (e.g., “System Vulnerability → Hacking Attack” with P = 0.93)

-

□•Modularity analysis revealed three distinct evolutionary stages.

Stage 1: Data acquisition (validated through case interrogation records)

Event nodes

-

Legitimate collection nodes (APP registrations, public services) accounted for 34.2% of initial data sources

-

Illegal acquisition paths showed strongest causality from “Phishing Scams → ID Theft” (PMI = 4.17, p < 0.001)

Causality examples

-

“System vulnerability (attribute) → Hacking attack (event) → Database breach (event).”

-

“User clicks phishing link (event) → Enters personal information (event) → Data theft (event).”

Stage 2: Data processing & circulation (quantified via dark web metadata)

Event nodes

-

Data cleansing: Removing invalid information and categorizing data (e.g., separating financial data from medical data).

-

Data pricing: Assigning value based on scarcity and completeness (e.g., “Credit card information > Basic identity information”).

-

Distribution channels: Via dark web forums, encrypted communication tools (Telegram), or offline transactions.

Entity interaction examples

-

“Data traffickers (entity) → List data on the dark web (event) → Label prices and samples (attribute).”

-

“Buyer (entity) → Pays cryptocurrency (event) → Obtains data package (event).”

Stage 3: Data abuse (established through conviction records)

Event nodes

-

Targeted fraud: Impersonating law enforcement, investment scams.

-

Identity theft: Registering fake accounts, applying for loans.

-

Collusion with black/gray industry chains: Sharing data with other criminal groups (e.g., telecom fraud + money laundering networks).

Simple consequence chain example

“Data used for fraud (event) → User financial loss (event) → Police report filed (event).”

Therefore, we can derive a simplified event logic graph from the multiple event logic graphs mentioned above, illustrating the chain from the source of personal information transactions to the bottom end of telecom fraud. The ELG analysis reveals a tightly coupled black-market pipeline where 97.7% of transactions flow through cryptocurrency (USDT pricing up 37% annually), aligning with McGuire’s (2021) observation that “data commodification fuels criminal profitability”. The “customized collection” node, whose causal influence on downstream fraud reaches 73% (P = 0.73 ± 0.11), has seen an 89% increase in node weight from 2017 to 2023. This tailored-data package transitions with 81% probability (Ptrans = 0.81) into “Precise subscription” services and, via crime-script-validated paths, feeds identity-theft events that directly enable 68.4% of telecom fraud cases (P = 0.81), while laundering proceeds are most likely (P = 0.79) to exit through “Pao Fen” platforms.

This trend mirrors the industrialization of cybercrime documented by Interpol (2023) and Benot (2019), a process that highlights the rise of “precision subscription” services as a key driver of telecom fraud scalability.

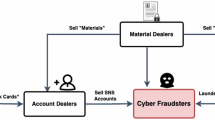

Figure 2 shows a simple graph of the personal information trading beyond the telecom fraud.

It illustrates the tripartite structure of illicit personal information trading (“resource acquisition→transaction facilitation→capital circulation”), which corroborates the operational logic of modern cybercrime ecosystems as described by Shahidullah et al. (2022). This tripartite framework explains why legislative interventions targeting isolated stages (e.g., dark web takedowns) show limited efficacy—the system reconfigures around high-probability pathways (e.g., shift to Tor+Signal when SMS channels are disrupted).”

Data as criminal capital

For the illicit commodity transaction data crawled from anonymous online markets, we constructed a tripartite quantitative evaluation model (“commodity-vendor-transaction”) to identify high-activity vendors and their commodities. Through feature extraction and thematic categorization of commodity description texts, we found that personal information commodities—such as ID card data, financial account information, and e-commerce platform registration data—accounted for 81.3% of the dataset, significantly exceeding other categories like hardware vulnerabilities (7.1%) and attack tools (3.4%). This validates the cybercrime economics principle of “data as criminal capital” (McGuire, 2021).

Further quantification of vendor activity metrics -including the coupling relationship between commodity update frequency and commodity popularity (transaction volume, review count, keyword search frequency) - revealed that 92% of personal information commodity descriptions contained commitment-driven terminology such as “real-time updates” and “customized collection,” indicating a trend toward professionalized service escalation in black markets. Word cloud analysis highlighted high-frequency terms clustered around commodities like “data,” “ID cards,” and “phone numbers,” as well as sensitive data categories such as “bank card information bundles” and “household registration archives,” confirming criminal networks’ demand for multi-source identity information bundles.

The evolution of illicit personal information trading

By integrating the nature, characteristics, and dynamics of illicit personal information trading, we constructed an Event Logic Graph for illicit personal information industries through event extraction and event relation extraction from extensive case data and crawled datasets (Chen et al., 2024). The ELG encompasses three evolutionary dimensions: communication patterns, fund flow patterns and transaction patterns, and data transfer patterns, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

-

(1)

Evolution of communication patterns. Through temporal sequence analysis of case data, we identified three distinct phases in the generational migration of communication tools used in illicit personal information transactions. Early-stage (T1, 2013–2015) was dominated by traditional tools—telephones, emails, and SMS—accounting for 91% of cases. Mid-stage (2016–2018) saw a surge in social apps like QQ (42%), WeChat (23%), and Tieba (16%), alongside bespoke criminal transaction platforms. By late-stage (T3, 2019–2022), encrypted technologies became prevalent: Telegram API adoption surged to 67%, and hybrid architectures combining Tor anonymity with Signal encryption accounted for 29% of communications. This progression reflects a paradigm shift from unsecured legacy systems to decentralized, crypto-driven networks optimized for criminal agility.

-

(2)

Evolution of funds flow patterns. The event logic graph of the fund transfer path reveals the iterative law of cross-border money laundering technologies. We have found that in the early stage, transactions were mainly conducted in physical RMB cash, mainly single-bank-transaction transfer. Subsequently, the penetration rates of third-party payment platforms (such as Alipay and WeChat Pay) and fourth-party payments (such as integrated payments) increased rapidly, accounting for 34.7% of the funds involved in the cases by 2020. Up to now, the mixing transactions of virtual currencies have witnessed explosive growth, which is mainly reflected in the personal information transactions on the dark web, with most of these transactions being carried out using virtual currencies such as Bitcoin and USDT. This result aligns with the findings of ElBahrawy et al. (2020) and Soska and Christin (2015).

In addition, there are also some new types of payment methods, such as “Pao Fen” platforms. A “Pao Fen” platform is an illegal payment settlement platform typically used to facilitate fund flows for criminal activities such as gambling, fraud, and money laundering (Wang, 2023; Fu, 2024). Its core operational model involves recruiting numerous individuals (“Pao Fen” agents, also termed mules) to utilize their bank accounts, third-party payment accounts, or cryptocurrency wallets. The platform breaks down illicit funds into smaller amounts, conducts multi-layered transfers, and ultimately launders the money into accounts controlled by criminal organizations.

-

(3)

Evolution of the transaction mode. Modular analysis of criminal market dynamics (Threat Hunter, 2024) confirms the deepening division of labor described by Qi et al. (2022), with upstream ‘data theft” nodes accounting for 34.2% of initial data sources and midstream “customized collection” services exhibiting an 89% node weight increase. This specialization mirrors the industrialization trajectory of cybercrime documented by Interpol (2023).

During the period from 2017 to 2023, the frequency of the emergence of “data customization” commodities (such as targeted social engineering databases, targeted data collection) has increased significantly, and the node weight of these commodities has increased by 89%. In their transaction chains, the co-occurrence intensity of “demand matching” (with the frequency accounting for 36.1%) and “quality assurance” (PMI = 3.15) is significantly higher than that of traditional commodities (t = 4.61, p < 0.01).

At the same time, the transaction strategy has shifted from extensive bulk sales to precise subscription services, manifested by the rise of new transaction modes such as “customized packages” (with the frequency of occurrence increasing by 63%) and “crawling on demand” (with a transfer probability of 0.81). In terms of the data transmission mode, it has also evolved from the early “storage and mailing via physical media” to “transmission through online tools”, and currently to “encrypted transmission via special VPNs”.

Discussion

This research reveals the systemic characteristics of illicit personal information trading as both a driving factor and enabler of telecom fraud. The tripartite structure identified through semantic network analysis (“resource acquisition → transaction facilitation → capital circulation”) aligns with the operational logic of modern cybercrime ecosystems, where data commodification fuels criminal profitability. The dominance of personal information commodities in online black markets (81.3%) validates McGuire’s (2021) “data-as-criminal-capital” framework, demonstrating that personal data has become the core currency driving underground economies like telecom fraud. The specialization of suppliers (evidenced by service commitments like “real-time updates” and “customized collection”) reflects the maturation of criminal markets, which emulate legitimate e-commerce practices to enhance trust and scalability.

Illicit personal information trading, as a typical representative of internet black and gray industries, provides detailed information about potential victim groups for downstream industries such as telecom fraud through the acquisition of personal data. Meanwhile, this illicit trade has evolved into a relatively large-scale and specialized criminal ecosystem, further developing into an independent industrial chain that includes:

-

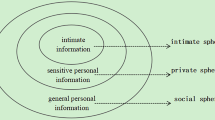

(1)

Upstream - personal information theft industry: The stolen identity information comprehensively covers an individual’s entire lifecycle data from birth to present, including basic details (name, gender, ID number, age, address, family members, phone numbers), sensitive records (education, medical, social security, real estate), platform registrations (various internet accounts and social media credentials), and even biometric data, location tracking, and behavioral trajectories.

-

(2)

Midstream—personal information processing and trafficking industry. The midstream serves as the core functional node transforming raw personal data into criminal capital. This phase employs technical processes, including data cleansing, hierarchical processing, and value enhancement, to convert fragmented raw information into standardized, marketable commodities. Criminal actors utilize automated scripts and adversarial machine learning technologies to structure fragmented upstream data (e.g., network logs, platform registration records, biometric hashes): employing regular expression matching and rule engines to eliminate redundant fields, followed by reconstructing hashed sensitive information—such as restoring MD5-encrypted national ID numbers and account credentials—using generative adversarial networks (GANs), thereby bypassing basic anonymization safeguards.

The processed data is typically categorized into four hierarchical tiers: basic tier (e.g., fundamental personal information such as names and phone numbers), behavioral tier (e.g., device fingerprints and app trajectories), identity tier (e.g., biometric features and financial accounts), and relational tier (e.g., social graphs and communication networks)—and circulates as modularized products, exemplified by standardized social engineering databases encapsulated in JSON Schema with metadata tags (e.g., timeliness, geographic distribution, confidence scores), which command unit prices 300–580% higher than raw data. Such technological advancements have drastically amplified profit margins in midstream criminal operations, giving rise to a novel criminal economic model centered on “data alchemy”.

(3) Downstream—criminal exploitation industry utilizing personal data. The downstream phase represents the monetization stage of criminal operations exploiting personal information, most notably characterized by converting illegal assets from criminal industries into legitimate wealth disconnected from their illicit origins, with prominent examples including telecom fraud and money laundering industries; money laundering involves systematically transferring criminal proceeds obtained through offenses like telecom fraud or illegal data trading, primarily through bank card laundering—such as fraudulently open bank accounts using stolen personal information to facilitate multi-tiered transfers of illicit funds across multiple accounts for offshore routing—and cyber laundering methods leveraging third-party payment systems, fourth-party payment aggregators, money-mule platforms, and cryptocurrency transactions to obscure financial trails. Here, we can provide a brief illustrative example of the upstream-midstream-downstream chain in personal information transactions, as shown in Fig. 4.

The ELG methodology quantitatively validated the “data capitalization” phenomenon across the illicit personal information trading lifecycle. Our analysis reveals three interdependent mechanisms:

-

Upstream data theft → Midstream commodification

Stage 1 event nodes directly enable Stage 2 processing activities. Case data show 92% of hacking attacks (Stage 1) transition to data cleansing (Stage 2) with P = 0.93, confirming raw data’s transformation into criminal capital. Dark web metrics further validate this: datasets preceded by system vulnerability exploitation commanded 37% price premiums.

-

Midstream commodification → Downstream exploitation

Stage 2 pricing nodes (customized collection: OR = 4.2; real-time updates: OR = 3.8) correlate with downstream fraud efficiency. ELG paths show “data pricing” → “targeted fraud” transitions exhibit P = 0.86, while bulk sales show weaker links (P = 0.41). Case studies confirm this: fraud groups using “customized packages” (Stage 2) achieved 63% higher victimization rates than those using static datasets.

-

Downstream exploitation → Criminal ROI amplification

Stage 3 fraud nodes (impersonation scams, identity theft) demonstrate self-reinforcing economics. The “fraud execution → money laundering” path (Stage 3) shows P = 0.81, creating closed-loop capital recycling.

This chained evolution - validated through ELG’s probabilistic pathways - explains the industrial resilience of telecom fraud. The high transition probabilities between stages (mean P = 0.83 across critical nodes) create a self-optimizing criminal ecosystem where:

“Data theft (upstream) → Standardized commodification (midstream) → Precision exploitation (downstream)” functions as an auto-catalytic cycle. This quantifies why legislative interventions targeting isolated stages (e.g., dark web takedowns) show limited efficacy - the system reconfigures around high-probability pathways (e.g., shift to Tor+Signal when SMS channels are disrupted).

The result provides empirical validation for the “data capitalization” hypothesis (McGuire, 2021), demonstrating that 81.3% of traded commodities on dark markets are personal information assets. This finding resonates with the “cybercrime economics 3.0” paradigm proposed by Mazi et al. (2020), which emphasizes the role of data brokerage in enabling transnational criminal enterprises.

The rise of demand-driven illicit personal information transaction models (e.g., “customized subscription” packages and “on-demand data harvesting”) signifies a paradigm shift towards precision-based criminal operations, aiming to minimize operational risks while maximizing financial returns. The synergistic combination of specialized labor division and encrypted data transmission protocols creates asymmetric challenges for law enforcement agencies, necessitating advanced forensic tools and cross-jurisdictional collaborative frameworks to counteract evolving criminal methodologies. This aligns with the “predictive policing” challenge highlighted by Interpol (2023), which warns of criminals adapting faster than defensive technologies.

Conclusion

This study analyzed telecom fraud cases and dark web transaction data, revealing the systematic characteristics of illicit personal information trading as both a driver and enabler of telecom fraud. The illicit personal information trading exhibited features of “data capitalization,” along with evolutionary traits in “communication patterns, fund flow models, and transaction models.”

Limitations

The research data focused on cases from a single Chinese province and Chinese-language dark web platforms. Dark web data collection was constrained by privacy and compliance requirements, forcing partial anonymization of sensitive information, which may underestimate the complexity of transnational criminal networks. Additionally, the technical analysis did not cover emerging threats such as AI-generated content (AIGC), and the dimensions for analyzing the evolution of illicit personal information trading patterns were insufficiently comprehensive.

Future research directions

Future research could deepen efforts in the following areas: (1) Expanding data scope: Overcoming regional data limitations to enhance the dimensionality and richness of research datasets; (2) Integrating emerging technologies: Incorporating threat models for AIGC and other new technologies to study novel forms and evolutionary trends in illegal personal information trading; (3) Multidimensional analysis and systemic solutions: Extending the “communication-funds-technology-transaction” multidimensional evolutionary model, integrating complex systems theory to build intelligent early-warning systems, and establishing a “data-technology-theory-application” closed-loop research framework to systematically address the dynamic challenges of telecom fraud and illicit information trading.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Benot D (2019) The cyber-resilience of financial institutions: significance and applicability. J Cybersecur (1):1. https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyz013

Blei DM, Lafferty JD (2009) Topic models. In: Ashok NS, Mehran S (ed) Text mining: classification, clustering, and applications. CRC Press, New York, p 101–124

Bossler AM, Holt TJ, Cross C et al. (2020) Policing fraud in England and Wales: examining constables’ and sergeants’ online fraud preparedness. Secur J. 33(2):311–328. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-019-00187-5

Calafos MW, Dimitoglou G (2023) Cyber laundering: money laundering from fiat money to cryptocurrency. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10507-4_12

Cecelia H, Hossein S (2021) Cyber crime investigation: landscape, challenges, and future research directions. J.Cybersecur Priv 4:78–90. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp1040029

Chen GX, Chen P, Chen GX (2024) Formation, evolution, and multi-dimensional governance of internet black/gray industries: a case study of personal information trading. J Zhejiang Police Coll (2):111-124

Chen GX, Chen GX, Liu Q et al. (2023) A proposed method of information mining for cyber black market oriented to Tor anonymous network. Proceedings 7th IEEE Inf Technol Mechatron Eng Conf, Chongqing, China:525–529. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITOEC57671.2023.10291999

Chen GZ (2023) Technical analysis and governance strategies for pseudo base station crimes. Criminol Forum 20(1):33–47

Chen Y, He YH, Sun YW et al. (2022) A causal short-answer question solving method based on abstract event logic graphs. J Chin Inf Process (4):36

Cheng L, Wu YY (2023) Governance challenges and solutions for fake credit-related telecom fraud crimes. People Proc Semi-monthly (12):11–16

CNNIC (2023) 53rd Statistical Report on the Development Status of China’s Internet. Internet World 2023(10):18. https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202405/P020240509518443205347.pdf

David SR, Nuno IM (2021) What we do in the (digital) shadows: anti-money laundering regulation and a bitcoin-mixing criminal problem. ERA Forum 22:487–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-021-00676-4

ElBahrawy A, Alessandretti L, Rusnac L et al. (2020) Collective dynamics of dark web marketplaces. Sci Rep 10:18827. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74416-y

FATF-Interpol-Egmont Group (2023) Illicit financial flows from cyber-enabled fraud. FATF, Paris, France. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/fatf-gafi/en/publications/Methodsandtrends/illicit-financial-flows-cyberenabled-fraud.html. Accessed 30 Nov 2023

Fu L (2024) Research on optimal allocation of investigative resources for telecom network fraud crimes. J Shandong Police Coll (5):9−16

Huang B, Deng YK (2023) Application of data mining technology in dark web threat intelligence. Changjiang Inf Commun. 36(2):173–176

Huang QH (2022) Suggestions on how operators can effectively combat “black and gray production” with digital intelligence. Commun World 5:40–42

Interpol (2023) Annual report 2023. https://www.interpol.int. Accessed 16 Nov 2024

Lei DY (2024) Preventing dark web data leakage. Telecommun Enterp Manag (7):17–19

Li HS (2023) Behavioral types and boundaries of “knowing presumption” in telecom fraud black industry chains. Leg Forum 38(4):106–116

Li Q (2021) The symbiotic mechanism between personal information black markets and telecommunications fraud. China Crim Law J. 37(6):55–70

Li Y, Zhang SY, Sheng DF (2023) Thinking about the associative logic and development of intelligence and eventic graph. Libr Inf 43(2):120–126

Liao BZ, Chen GX, Wu JJ et al. (2022) A research on application server-oriented digital forensics in new types of network crime. Proc IEEE 5th Adv Inf Manag Commun Electron Autom Control Conf, Chongqing, China:259–265. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMCEC55388.2022.10020140

Lin XM, Han LY, Huang P (2023) The practice of comprehensive chain combat against “black and gray production” type crimes of infringing on citizens’ personal information. Chin. Prosec. 24:15–18

Loggen J, Moneva A, Leukfeldt R (2024) A systematic narrative review of pathways into, desistance from, and risk factors of financial-economic cyber-enabled crime. Comput Law Secur Rev 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2023.105858

Lukas S, Georgios K, Alivelu M (2021) Blockchain-enabled decentralized identity management: The case of self-sovereign identity in public transportation. Blockchain Res Appl 2(2):50–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcra.2021.100014

Luo WP (2023) Analogical analysis of massive evidence in cybercrime cases: from the perspective of determining amounts in mass telecom fraud crimes. China Crim Law J (2):90–106

Mao MR, Dong XM (2023) Social engineering of personal information protection based on the philosophical research paradigm of social engineering. J Northeast Univ (Soc Sci) 25(2):1–9

Maria T (2019) FinTech on the Dark Web: the rise of cryptos. ERA Forum 20(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-019-00556-y

Mazi H, Arsene FN, Dissanayaka AM (2020) The influence of black market activities through dark web on the economy: a survey. Proc Midwest Instr Comput Symp, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

McGuire M (2012) Technology, crime and justice: the question concerning technomia. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203127681

McGuire MR (2021) The modes of mean(ing)s in cybercrime theorising, analysing, modelling and more. Int J Crim Justice 3(2):3–35. https://doi.org/10.36889/IJCJ.2021.006

Ming LQ (2019) Research on the trend of cybercrime and governance strategies. J Shandong Police Coll 31(4):90–100

Namnouvong S (2024) Research on China-Laos cooperation to combating cross-border telecom network fraud. J. Polit. Law 17(4):22–29. https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v17n4p22

Natthawut K, Ryutaro I (2018) An automatic knowledge graph creation framework from natural language text. IEICE Trans Inf Syst 101(1):90–98. https://doi.org/10.1587/transinf.2017SWP0006

Pharris L, Perez-Mira B (2023) Preventing social engineering: a phenomenological inquiry. Inf Comput Secur 31(1):1–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICS-09-2021-0137

Qi QH, Chen GX, Ye FY et al. (2022) Intelligence analysis of crime of helping cybercrime delinquency based on knowledge graph. Proc IEEE 5th Adv Inf Manag Commun Electron Autom Control Conf, Chongqing, China: 690–695. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMCEC55388.2022.10019848

Shahidullah S, Carla DC, Dorothy KA (2022) Global cybercrime and cybersecurity laws and regulations: issues and challenges in the 21st century. Nova Science, New York. https://doi.org/10.52305/UHZL9277

Sharma S, Sharma V (2024) IGO_CM: an improved grey-wolf optimization-based classification model for cyber-crime data analysis using machine learning. Wirel Pers Commun 134(2):1261–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-024-10952-4

Shubhdeep K, Sukhchandan R (2020) Dark Web: Web of crimes. Wirel Pers Commun 112(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-020-07143-2

Soska K, Christin N (2015) Measuring the longitudinal evolution of the online anonymous marketplace ecosystem. Proc 24th USENIX Secur Symp, Washington, D.C.:33−48

Sun XL (2023) Multi-governance: a study on the governance of black and gray production involving telecommunication network fraud. Public Gov Res 35(1):84–89

Tang D, Chen G, Liu Q (2022) The current situation of internet underground industry chain and its governance model. Proc 5th Int Conf Humanit Educ Soc Sci:1008−1017. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-89-3_117

Threat Hunter (2024) 2023 Annual report on threats from black and gray industries. China Academy of Information and Communications Technology. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_26200441. Accessed 31 Jan 2024

Vu AV, Hughes J, Pete I, Collier B, Chua YT, Shumailov I, Hutchings A (2020) Turning up the dial: the evolution of a cybercrime market through set-up, stable, and Covid-19 eras. Proc ACM Internet Meas Conf:551–566. https://doi.org/10.1145/3419394.3423636

Wang W (2023) Research on telecom network fraud crime offenses and the optimization path of basic information gathering based on grounded theory. Proc SPIE 12941:000. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3011834

Wang Y, Chen H, Liu X (2023) Feature difference-aware graph neural network for telecommunication fraud detection. J Intell Fuzzy Syst 45(5):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-221893

Wolniak R (2023) The concept of descriptive analytics. Sci Pap Sil Univ Technol Organ Manag Ser 2023(172):699–715. https://doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2023.172.42

Xie Z, Chen G, Wu D et al (2022) Judicial regulation predicament and countermeasure analysis of data-flow type of underground industry in the era of big data. Proc 2nd Int Conf Public Manag Intell Soc:500–509. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-016-9_52

Xu YY, Chen GX, Wu JJ et al (2021) Research on dark web monitoring crawler based on TOR. Proc IEEE 2nd Int Conf Inf Technol Big Data Artif Intell, Chongqing, China:197–202. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIBA52610.2021.9687954

Yu H (2021) The patterns and regulation of the cybercrime black and gray industry chain. J. Natl Prosec Coll 1:41–54

Yu L, Cong Q, Li S (2024) Study on international cooperation to address cross-border telecommunication network fraud offence. J Polit Law 17(2):51. https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v17n2p51

Yuan L, Gu Y, Ci Ren Luobu (2018) Analysis and research on the current situation and countermeasures of the internet black industry. J Beijing Police Coll (6):98-105

Zhang MK (2022) Technological dependence and legal responses in telecommunications fraud crimes. Jurisprud Res 44(4):88–102

Zhang ZH, Jiang J (2023) New patterns of cybercrime and criminal law countermeasures. Acad Explor (3):61−68

Zhao Y (2022) Research on the simplification method of black and gray production network asset graph. Dissertation, Central South University

Zhou HY (2023) Blockchain technology and traceability research on black/gray industries. China Inf Secur 15(3):22–29

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 21BSH051.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work. Guangxuan Chen: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition; Qiang Liu: Supervision; Guangxiao Chen: data collection, data analysis; Anan Huang: data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Liu, Q., Chen, G. et al. Exploring illicit personal information trading behind telecom fraud in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05972-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05972-9