Abstract

This research sets up a new DEA model, Entropy Meta Two Parallel Three-Stage Dynamic DDF, to evaluate the efficiency of 42 banks in China over the period 2019–2023. Different from other studies, we integrate enterprise risk into the efficiency analysis framework, account for the stage characteristics of banks (enterprise risk, operation, sustainability, and market), exploring the changes in heterogeneous bank efficiency. The findings are as follows. (a) Most banks show positive growth in total efficiency. (b) The enterprise risk stage efficiency generally rises with a slight fluctuation, the operation stage efficiency is at a relatively high level, 70% of banks have superior performance in sustainability stage, and 80% of banks still have not achieved superior market efficiency. (c) There is a negative correlation between enterprise risk and operational stage efficiency and a positive correlation between sustainability stage and market stage efficiency. The systems exhibit a high degree of coupled coordination. (d) Most banks have higher operational efficiency than sustainability efficiency and higher sustainability efficiency than market efficiency. State-owned commercial banks have the strongest risk resistance and perform optimally in different stages. Lastly, we note that joint-stock commercial banks must pay attention to the sustainability stage and market stage efficiencies, urban commercial banks should target to improve market stage efficiency, and rural commercial banks need to focus on enhancing enterprise risk stage efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

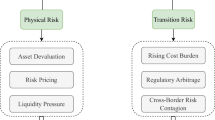

Banks serve as a critical intermediary in fund financing, while also bearing significant responsibility for optimizing financial resource allocation and mitigating economic risks. Recent global market uncertainties and unforeseen events have significantly impacted corporates’ business operations (Gulati, 2022). These risks also profoundly affect banks’ asset quality, profitability, and operational efficiency (Gulati et al., 2023). China’s capital market has shown remarkable growth in recent years, with the banking industry maintaining its central role in the financial system. Banks’ sound operation is crucial for the country’s macroeconomic stability and vitality of microeconomic entities. However, the traditional bank efficiency literature has primarily focused on overall efficiency or isolated operational and financial efficiency. While studies have yielded valuable insights, they often lack a comprehensive analysis of the enterprise risk and bank efficiency nexus (Cai et al., 2024).

Given the critical role of bank risk management in maintaining financial stability and preventing systemic risks, our analytical framework incorporates risks faced by bank vendors. This approach enables a more accurate assessment of banks’ real efficiency. This analytical framework also offers a robust foundation for the scientific development of bank risk management strategies and efficiency optimization. Such analysis is not only vital for the sustainable development of banks, but also contributes significantly to enhancing market efficiency and stability (Fang et al., 2020).

Although banks differ from traditional enterprises, their core objective remains profit maximization. As banks are regarded as a unique type of enterprise, their efficiency analysis focuses on maximizing output with minimal input. At the micro-level, commercial banks utilize resources such as human capital, financial capital, and technology to conduct activities like deposits, loans, investments, and asset management services, generating interest and non-interest income to achieve profit maximization (Shi et al., 2022). Therefore, bank efficiency is reflected in operational quality and specifically the optimization of input-output ratios. High-efficiency banks demonstrate more rational resource allocation and superior input-output ratios. One major limitation of early studies is the simplification of bank operations into an opaque “black box”, focusing only on macro-level inputs and outputs while neglecting the specific operations of internal sub-stages (Hwang et al., 2012). This perspective may incur misjudgments of overall bank efficiency, as certain sub-stages may exhibit inefficiencies despite apparent effectiveness at the macro-level, ultimately affecting decision-making quality.

Traditional DEA models typically assume that all producers operate under the same technological conditions. However, the decision-making units (DMUs) under evaluation often exhibit varying production technologies due to differences in geographic location, national policies, and socio-economic factors. To address these limitations, we propose the Entropy Meta Two Parallel Three-Stage Dynamic DDF model to calculate the efficiency of the overall system and individual production units. Compared with the dynamic network DEA model, the model used in this paper considers cross-period continuous effects, regional differences, and parallel issues in different stages. Based on the results, decision-makers can reallocate resources among different production units within the system more effectively, thereby enhancing system efficiency and avoiding any underestimation or overestimation of efficiency values and improvement potential.

Against this backdrop we focus on the impact of enterprise risk on banks’ sustainability and market efficiency, using the Entropy Meta Two Parallel Three-Stage Dynamic DDF model to measure enterprise risk efficiency, operational efficiency, sustainability efficiency, and market efficiency of 42 Chinese commercial banks. Considering the phased characteristics of bank operations, we examine overall efficiency, four-stage efficiency, inter-stage correlations, coupling coordination, and efficiency changes of the heterogeneous banks over recent years.

The three main contributions of this paper are as follows. (a) The research methodology improved the bank efficiency assessment model. It is the first to employ the Parallel Entropy Three-stage Dynamic DDF model as the research methodology. Compared with the dynamic network DEA model, this model considers inter-period continuity effects, regional differences, and parallel issues in different stages. (b) Other studies do not incorporate enterprise risk into the efficiency analysis framework of banks, and so there is a gap in the literature on the relationships among enterprise risk, banks’ sustainability, and market efficiency. This paper fills this gap by integrating enterprise risk into the efficiency analysis framework, thereby expanding the relevant literature. (c) By opening the “black box” of enterprise operations, we move beyond focusing solely on overall bank efficiency or operational and financial efficiencies in isolation. Instead, we construct a multi-stage efficiency evaluation process for banks, comprehensively considering risk management, operational efficiency, sustainability capabilities, and market competitiveness, and evaluate the efficiency of banks in different stages.

Literature review

Enterprise risk and bank efficiency

Enterprise risk

The enterprise risk literature primarily focuses on venture capital, risk management, and risk-taking. During the growth or startup phase of enterprises, venture capital (VC) plays a crucial role by providing essential expansion funds. However, the high risk of VC does not always correlate with high returns (Xuanling and Meng, 2023). Wen and Feng (2018) found during their sample period that VC overall lowers the innovation levels of small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), suggesting that the value-added benefits provided by Chinese VC to startups may be very limited. Risk management reduces unnecessary losses by identifying and controlling potential risks, but building a risk management system requires significant resource investment that negatively affects operational efficiency to some extent (Chen et al., 2019). (Hughes and Mester, 2013) based on top US bank holding companies incorporated risk endogeneity into bank economies of scale and found that traditional methods ignored risk endogeneity, leading to estimation bias, emphasizing the necessity of risk adjustment.

Regarding risk management, most scholars have studied its effectiveness and optimal strategies. For instance, Huang et al. (2020) used a two-Stage DEA model to investigate the impact of risk management efficiency on the production efficiency of Chinese listed companies from 2002 to 2016, demonstrating that companies with low enterprise risk management index efficiency tend to have lower performance. Olson and Wu (2023) utilized a DEA model to illustrate the application of risk value in enterprise risk management and how DEA can be used for efficiency analysis and risk assessment. The level of risk-taking enhances supply chain management and promotes the improvement of enterprise value (Zhang et al., 2023). Financial risk and credit risk are also types of enterprise risks. Tsolas (2021) used two-stage DEA combined with a bootstrapped approach to assess the credit risk of Greek pharmaceutical companies, revealing that operational efficiency is generally higher than effectiveness, but there is no significant correlation between the two. Bagade et al. (2023) evaluated the financial efficiency and credit risk of SMEs, finding no direct relationship between the two. Nourani et al. (2020) suggest that the regulatory environment also changes the degree of external risk, leading to differences in efficiency.

Bank efficiency

Existing literature has examined the multifaceted efficiency of banks. For example, Kamarudin et al. (2013) focus on the price efficiency of 74 banks in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and further analyze the cost efficiency, revenue efficiency, and profit efficiency of banks. Thaker et al. (2022) examine the new technical efficiency, new cost efficiency, and new profit efficiency of Indian banks from a corporate governance perspective. Kamarudin et al. (2022) analyze the impact of country governance on banks’ productivity by focusing on the country governance dimension using a sample of banks from Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and Singapore. Obadire et al. (2022), on the other hand, focus on the operational and investment efficiency of 45 listed banks operating in 6 African countries. Most relevant to the bank efficiency studied in this paper is the study of Chen et al. (2024) on operational efficiency, market efficiency and sustainability in Taiwan’s banking sector, which analyze 32 banks using a two-stage dynamic SBM model and found that the financial holding banks were leading across the board in terms of operational, market and sustainability efficiencies. However, this study did not incorporate corporate risk factors into the analytical framework, which limiting the comprehensiveness of the findings.

There is a literature on ESG and bank efficiency. Corporate ESG practices are one of the key indicators for evaluating corporate sustainability, which is related to banks’ risk-taking behavior and bank value (Di Tommaso and Thornton, 2020). Inadequate operational, financial sustainability may lead to overall inefficiency (Mia et al., 2023). Aevoae et al. (2023) verified that ESG scores can mitigate bank-specific risks based on 367 listed banks in 47 countries. Controversial positions on ESG and bank efficiency have emerged from several cross-country studies, with one strand of literature supporting the positive contribution of ESG to corporate efficiency. Stakeholder theory emphasizes that a bank’s good ESG performance improves performance by improving the firm’s relationship with its stakeholders, reducing transaction costs and creating a market premium (Bouattour et al., 2024). Using a sample of banks from 21 countries, Chiaramonte et al. (2022) demonstrate that the longer the duration of ESG disclosure, the greater the stability of the bank. ESG investments, through the human capital transmission mechanism, can be externalized into quantifiable benefits such as reduced employee turnover, increased capacity to attract top talent, and increased labor productivity (Adeabah and Andoh, 2020).

Some studies have challenged the above findings, with some scholars arguing that ESG practices have a negative impact on bank efficiency. For example, the findings of Batae et al. (2021) negate the prediction of stakeholder theory that social responsibility is positively related to financial performance. Bruno et al. (2024), based on European listed banks, find that even though ESG practices can improve bank stability, they increase non-performing loans, suggesting that ESG has a trade-off with risk. Liu et al. (2023a; 2023b) find similar negative effects on a sample of US commercial banks. Some other scholars argue that there is uncertainty about the impact of ESG practices on bank performance (Islam et al., 2025). For example, Saif-Alyousfi et al. (2023) find a non-linear relationship between ESG and bank performance from a sample of 1385 banks from 89 countries around the world, with the environmental and social dimensions having a negative impact on bank diversification and the corporate governance dimension having a positive impact. Therefore, further examination of bank ESG is warranted in this paper by including bank sustainability dimensions in the framework.

Enterprise risk and bank efficiency

Research on enterprise risk and micro-size enterprises is abundant, but there is a notable gap in studies addressing the impact of enterprise risk on banks’ sustainability and market efficiency. The literature has primarily examined the effects of enterprise risk on credit efficiency, investment efficiency, and financing efficiency. Interestingly, studies on how enterprise risk affects banks are not only limited, but also yield controversial conclusions (Huizhi and Xianghua, 2023). One strand of the literature supports a positive effect between firm risk reduction and bank efficiency. For example, Chaoqun et al. (2024) measured the credit business efficiency of 26 listed commercial banks in China based on a dynamic network DEA and Malmquist index model, finding that reducing risk and uncertainty supports the stable development of the financial sector. Jiang et al. (2024), using a sample of listed companies on the Australian Stock Exchange, found that effective risk management committees mitigate both overinvestment and underinvestment, thereby enhancing corporate investment efficiency. Sulistyawati and Suryani (2022), based on data from 130 manufacturing companies listed on the Indonesian Stock Exchange, used a DEA model to measure operational efficiency and found that risk disclosure positively impacts corporate operational efficiency. Another strand of literature takes the opposite view. For example, Ullah et al. (2023) use DEA to explore the determinants of bank efficiency in emerging economies and find that enterprise risk management adversely affects the efficiency of banks. Liu et al. (2023a; 2023b) argue that increased economic policy uncertainty allows firms to gain competitive advantages and excess returns through immediate investments, thereby improving investment efficiency.

In summary, the related literature has the following limitations. (a) Studies typically focused on the overall efficiency of banks or operational and financial efficiencies in isolation, with limited attention to the sustainability and market efficiency of bank vendors. (b) There is a lack of focus on incorporating enterprise risk into the efficiency analysis framework of banks. (c) A significant gap exists in research addressing the relationship between enterprise risk and the sustainability and market efficiency of banks.

Bank efficiency evaluation methods

In evaluating bank efficiency, scholars commonly employ two types of methods: parametric and non-parametric. Parametric methods often use Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA), while non-parametric methods frequently utilize Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). Both SFA and DEA models have their respective strengths in different efficiency measurement contexts, and the choice between them should be based on specific application scenarios and research needs. Compared to SFA, DEA does not require a predefined production function form, offering unique advantages in studies involving multiple inputs and outputs. Therefore, this study uses a DEA model to assess the performance of banks.

When Chinese scholars use a DEA model to evaluate bank efficiency, they often employ extended forms such as the dynamic network DEA (Zhao and Wu, 2024), DEA-Malmquist (Yan and Feng, 2021), SBM-DEA (Wang, 2022), and SBM network DEA (Zhu et al., 2023). However, the application of the Directional Distance Function (DDF) model remains limited (Zhang and Zhou, 2022). International studies have more applications for DDF, for example, Sun et al. (2017) combined DDF with the meta-frontier approach to evaluate the efficiency of bank supply chain systems, with the model’s main feature being its consideration of intrinsic technological differences among supply chains. Hamid et al. (2017) emphasized that non-performing loans, often overlooked, must be incorporated into efficiency evaluations in the banking sector. Ignoring these undesirable outputs may lead to misleading results and unfair assessments. They used the DDF method to handle both desirable and undesirable outputs of banks, revealing that domestic banks slightly outperform foreign banks in Malaysia in terms of DEA technical efficiency. Lee et al. (2024) constructed a Meta Entropy Dynamic Two-Stage DDF model, incorporating financial technology (fintech) to examine the operational and market efficiencies of Taiwanese banks, providing a new perspective for bank performance analysis.

We choose the DDF-DEA approach to evaluate bank efficiency for three main reasons. (a) DDF ensures that efficiency values decrease when inputs and undesirable outputs increase or desirable outputs decrease, and vice versa, making efficiency evaluation more intuitive. (b) Unlike radial models, DDF allows for custom direction vectors based on research needs, enabling independent changes in input and output indicators, which more accurately simulate the economic behavior of banks. (c) This model overcomes the limitation of traditional DEA methods that ignore the internal structure of DMUs (Xie et al., 2022).

A fundamental type of network structure is the parallel system, where DMUs in the production process are composed of sub-units. The Network DEA model applies sub-production technology to explore the impact of input allocation and intermediate products on the production process, rather than treating them as an unassessable “black box” (Färe et al., 2007). Kao (2009) investigated the relationship between subsystem inefficiency and overall system inefficiency, proposing a parallel DEA model to calculate the efficiency of both the entire system and the parallel subsystems. Tone and Tsutsui (2014) further introduced Weighted Slack-Based Measures Dynamic Network DEA, using the linkage between departments of DMUs as the analytical foundation for the network DEA model. In this approach, each department is treated as a sub-DMU, with carry-over activities serving as the linkages.

Traditional DEA models typically assume that all producers operate under the same technological conditions when conducting efficiency evaluations. However, the DMUs under evaluation often exhibit varying production technologies due to differences in geographic location, national policies, socio-economic factors, and other conditions. To address this, Battese and Rao (2002), Battese et al. (2004), and O’Donnell et al. (2008) introduced the concept of the Meta Frontier into DEA efficiency estimation. By measuring the distance between the Group Frontier and the Meta Frontier, they calculated the Technology Gap Ratio (TGR) to account for differences in production technologies. This approach resolves the problem of DMUs’ heterogeneous production technologies.

Since the dynamic network DEA model proposed by Tone and Tsutsui (2014) does not account for cross-period carry-over effects, regional heterogeneity, or parallel structures, we integrate Tone and Tsutsui’s (2014) dynamic network DEA model with Kao’s (2009) parallel DEA model to propose the Entropy Meta Two Parallel Three-Stage Dynamic DDF model. This model calculates the efficiencies of both the overall system and individual production units. Based on the results, decision-makers can more effectively reallocate resources among different production units within the system, thereby enhancing system efficiency, avoiding an underestimation or overestimation of efficiency values, and targeting improvement potential.

Research methodology and data sources

Entropy method

In this model, the input items in Stage 1.1 (enterprise risk stage) consist of two dimensions.

(a) Corporate Governance Input Indicators: Composed of foreign ownership ratio, domestic ownership ratio, and insider ownership ratio.

(b) Corporate Characteristics Input Indicators: Composed of firm size, leverage ratio, opacity, liquidity, idle funds, sales growth rate, and operating costs.

Since the input indicators in this stage are divided into two dimensions, each encompassing multiple detailed indicators, directly incorporating these detailed indicators into the DEA model would lead to unsolvable problems. Therefore, this model first uses Shannon’s (1948) entropy method to synthesize the detailed indicators within the two dimensions - (a) corporate governance input indicators and (b) corporate characteristics’ input indicators - into a single composite value for each dimension. The specific steps of the entropy method are as follows.

Step 1: Data Standardization. Standardize the (a) corporate governance input indicators and (b) corporate characteristics’ input indicators for the 42 Chinese banks using the following formula:

Here, rmn is the standardized value of the nth metric for the mth bank, \(\max {{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{mn}}}\) is the minimum value of the nth metric for the mth bank, and \(\max {{\rm{x}}}_{{\rm{mn}}}\) is the maximum value of the nth metric for the mth bank.

Step 2: Aggregation of Standardized Values. Sum the standardized values of (a) corporate governance input indicators and (b) corporate characteristics’ input indicators in Stage 1.1.

Here, Pmn denotes the sum of the standardized values of the nth indicator for m banks.

Step 3: Calculate the entropy value (en) for the nth metric.

Step 4: Calculate the weight (wn) of the nth indicator.

Based on the steps outlined above, calculate the weights and output values for (a) corporate governance input indicators and (b) corporate characteristics’ input indicators in Stage 1.1.

Entropy meta two parallel three-stage dynamic DDF model

Assume that DMUs (j = 1, …, N) have three stages within each time period t (t = 1, …, T). Stage 1 is parallel, consisting of Stage 1.1 (enterprise risk stage) and Stage 1.2 (operational stage). Stage 2 is the sustainability stage, and Stage 3 is the market stage.

In Stage 1.1 there are I inputs \({{\rm{X}}11}_{{\rm{i}}{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{i}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{I}}\right)\) that generate D intermediate products \({{\rm{z}}11}_{{\rm{dj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{d}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{D}}\right)\) and K desired outputs \({{\rm{y}}11}_{{\rm{kj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{k}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{K}}\right)\). In Stage 1.2 there are A inputs \({{\rm{X}}12}_{{\rm{aj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{a}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{A}}\right)\) that generate B intermediate products \({{\rm{z}}12}_{{\rm{bj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{b}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{B}}\right)\) and F desired outputs \({{\rm{y}}12}_{{\rm{fj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{f}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{F}}\right)\). Stage 2 uses U inputs \({{\rm{X}}2}_{{\rm{u}}{\rm{j}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{u}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{U}}\right)\) and generates S desired outputs \({{\rm{y}}2}_{{\rm{sj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{s}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{S}}\right)\) and E intermediate products \({{\rm{z}}2}_{{\rm{ej}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{e}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{E}}\right)\). Stage 3 uses V inputs \({{\rm{X}}3}_{{\rm{vj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{v}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{V}}\right)\), while creating L desired outputs \({{\rm{y}}3}_{{\rm{lj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{l}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{L}}\right)\). \({{\rm{c}}}_{{\rm{hj}}}^{{\rm{t}}}\left({\rm{h}}=1,\ldots ,{\rm{H}}\right)\) is the carry-over factor.

We divide the efficiency of banks into three stages. Figure 1 illustrates the specific structure.

In Stage 1.1: Enterprise Risk Stage, where the inputs are corporate governance and corporate characteristics, and the outputs are default risk and business risk. The outputs of this stage are treated as intermediate products (link) and serve as inputs for Stage 2 (Huang et al., 2020).

In Stage 1.2: Operational Stage, where the inputs are employees and deposits, while the outputs are loans, investment, income, and profit. The income and profit outputs of this stage are treated as intermediate products (link) and serve as inputs for Stage 2 (Liao et al., 2024).

In Stage 2: Sustainability Stage, where the inputs include income and profit (shared by both stages), board compensation, taxes and fees payable, and the two outputs from the enterprise risk stage (default risk and business risk). The outputs of the sustainability stage are indicators of environment, society, and corporate governance. The environmental and social outputs of this stage are treated as intermediate products (link) and serve as inputs for Stage 3 (Lee and Saen, 2012).

In Stage 3: Market Stage, where the inputs are environmental indicators and social indicators, and the outputs are market value and earnings per share. Fixed assets from each period are carried over to the next period (Lee et al., 2023).

Assume there are 42 bank DMUs (j = 1, …, n) spanning 5 periods (t = 1, …, T). Each DMU has inputs and outputs in each of the 5 periods, and the input and output variables are connected to the next period (t + 1) through carry-over activities.

Meta-Frontier (MF)

Due to differences in management types, resources, regulations, or environments, all banks N (j = 1,…,N) are composed of g groups of DMUs \(\left({\rm{N}}={{\rm{N}}}_{1}+{{\rm{N}}}_{2}+...+{{\rm{N}}}_{{\rm{G}}}\right)\). Under the MF, each DMU p selects the most favorable weights for its final outputs to maximize its efficiency value.

The efficiency of DMU p is:

Subject to:

Stage 1.1: Enterprise risk stage | Stage 1.2: Operation stage |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{X11}_{{ijg}}^{t}\le {X11}_{{ipg}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1.1{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{ipg}}^{t}\quad\forall i,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{y11}_{{kjg}}^{t}\ge {y11}_{{kpg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.1{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{kpg}}^{t}\quad\forall k,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{z11}_{{djg}}^{t}\ge {z11}_{{dpg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.1{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{dpg}}^{t}\quad\forall d,\forall t\) | \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{X12}_{{ajg}}^{t}\le {X12}_{{apg}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1.2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{apg}}^{t}\quad\forall a,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{y12}_{{fjg}}^{t}\ge {y12}_{{fpg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{fpg}}^{t}\quad\forall f,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{z12}_{{bjg}}^{t}\ge {z12}_{{bpg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{bpg}}^{t}\quad\forall b,\forall t\) |

Stage 2: Sustainability stage | Stage 3: Market stage |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{X2}_{{ujg}}^{t}\le {X2}_{{upg}}^{t}-{\theta }_{2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{upg}}^{t}\quad\forall u,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{y2}_{{sjg}}^{t}\ge {y2}_{{spg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{spg}}^{t}\quad\forall s,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{z2}_{{ejg}}^{t}\ge {z2}_{{epg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{2{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{epg}}^{t}\quad\forall e,\forall t\) | \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{X3}_{{vjg}}^{t}\le {X3}_{{vpg}}^{t}-{\theta }_{3{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{vpg}}^{t}\forall v,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{y3}_{{ljg}}^{t}\ge {y3}_{{lpg}}^{t}+{\theta }_{3{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{lpg}}^{t}\quad\forall l,\forall t\) |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}{c}_{{hjg}}^{t}\le {C}_{{hpg}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1{pg}}^{t}{q}_{{hpg}}^{t}\quad\forall h,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{{jg}}^{t}=1\quad{\lambda }_{j}^{t}\ge 0\forall j,\forall t\) |

Link between Stage 1.1 and Stage 2:

Link between Stage 1.2 and Stage 2:

Link between Stage 2 and Stage 3:

Link of two periods:

Here, \({w}_{1}^{t}\) \({w}_{2}^{t}\), and \({w}_{3}^{t}\) represent the weights assigned to the efficiency of Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3, respectively. Hence, \({w}_{1}^{t},{w}_{2}^{t},{w}_{3}^{t},\,\ge 1\), and \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}{\gamma }_{{tg}}=1\).

From the above results, the Meta-Frontier model can be used to obtain overall efficiency, period efficiency, stage efficiency, and period-stage efficiency.

Group-Frontier (GF)

Due to each DMU under the Group-Frontier selecting the most favorable weighted final outputs, the efficiency of DMUs under the Group-Frontier is solved using the following equation.

The efficiency of DMU p is:

Subject to:

Stage 1.1: Enterprise risk stage | Stage 1.2: Operation stage |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{X11}_{{ij}}^{t}\le {X11}_{{ip}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1.1p}^{t}{q}_{{ip}}^{t}\quad\forall i,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{y11}_{{kj}}^{t}\ge {y11}_{{kp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.1p}^{t}{q}_{{kp}}^{t}\quad\forall k,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{z11}_{{dj}}^{t}\ge {z11}_{{dp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.1p}^{t}{q}_{{dp}}^{t}\quad\forall d,\forall t\) | \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{X12}_{{aj}}^{t}\le {X12}_{{ap}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1.2p}^{t}{q}_{{ap}}^{t}\quad\forall a,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{y12}_{{fj}}^{t}\ge {y12}_{{fp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.2p}^{t}{q}_{{fp}}^{t}\quad\forall f,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{z12}_{{bj}}^{t}\ge {z12}_{{bp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{1.2p}^{t}{q}_{{bp}}^{t}\quad\forall b,\forall t\) |

Stage 2: Sustainability stage | Stage 3: Market stage |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{X2}_{{uj}}^{t}\le {X2}_{{up}}^{t}-{\theta }_{2p}^{t}{q}_{{up}}^{t}\quad\forall u,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{y2}_{{sj}}^{t}\ge {y2}_{{sp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{2p}^{t}{q}_{{sp}}^{t}\quad\forall s,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{z2}_{{ej}}^{t}\ge {z2}_{{ep}}^{t}+{\theta }_{2p}^{t}{q}_{{ep}}^{t}\quad\forall e,\forall t\) | \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{X3}_{{vj}}^{t}\le {X3}_{{vp}}^{t}-{\theta }_{3p}^{t}{q}_{{vp}}^{t}\quad\forall v,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{y3}_{{lj}}^{t}\ge {y3}_{{lp}}^{t}+{\theta }_{3p}^{t}{q}_{{lp}}^{t}\quad\forall l,\forall t\) |

\(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}{c}_{{hj}}^{t}\le {C}_{{hp}}^{t}-{\theta }_{1p}^{t}{q}_{{hp}}^{t}\quad\forall h,\forall t\) \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j}^{n}{\lambda }_{j}^{t}=1\quad{\lambda }_{j}^{t}\ge 0\forall j,\forall t\) |

Link between Stage 1.1 and Stage 2:

Link between Stage 1.2 and Stage 2:

Link between Stage 2 and Stage 3:

Link of two periods:

Here, γt is the weight assigned to period t. \({w}_{1}^{t}\) \({w}_{2}^{t}\), and \({w}_{3}^{t}\) represent the weights assigned to the efficiency of Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3, respectively. Hence, \({w}_{1}^{t},{w}_{2}^{t},{w}_{3}^{t},\ge 1\), and \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{g=1}^{G}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{t=1}^{T}{\gamma }_{{tg}}=1\).

From the above results, overall efficiency, period efficiency, stage efficiency, and period-stage efficiency are obtained.

Technology Gap Ratio (TGR)

Since the Meta-Frontier model comprises g groups, the technical efficiency of Meta-Frontier Efficiency is less than that of Group-Frontier Efficiency. The ratio between the two, known as the TGR, is given by:

Coupling coordination model

To examine the degree of coupling coordination among the banks’ stages, we construct a coupling coordination model for four subsystems. The coupling coordination among the enterprise risk system (S11), operational system (S12), sustainability system (S2), and market system (S3) is treated as a dynamic process. A state of complete coupling coordination is achieved when all subsystems operate efficiently. The degree of coupling function for the four systems is:

Here, \({{\rm{S}}}_{11}^{{\rm{meta}}},{{\rm{S}}}_{12}^{{\rm{meta}}}{,{\rm{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{meta}}}\) and \({{\rm{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{meta}}}\) represent the indicator values of each system, and C denotes the system’s degree of coupling with a value range of [0, 1]. A value of C = 0 indicates that the systems or their internal elements are in a disordered state, while C = 1 signifies strong coupling among the systems.

Here, D represents the degree of coupling coordination, where a higher D value indicates better coordination and operational efficiency among the subsystems. T represents the comprehensive coordination coefficient of the four systems, with ai reflecting the contribution weights of each system.

Indicator selection and data sources

Based on the principle of data availability, we select 42 Chinese banks from the CSMAR and iFind databases. The sample includes 5 state-owned commercial banks, 10 joint-stock commercial banks, 17 urban commercial banks, and 10 rural commercial banks. According to banks’ ownership type, the sample is divided into four groups: Group 1 consists of state-owned commercial banks, Group 2 includes joint-stock commercial banks, Group 3 comprises urban commercial banks, and Group 4 represents rural commercial banks. The sample period spans 2019 to 2023. Table 1 lists the specific measurement indicators for the enterprise risk stage. Table 2 presents detailed indicator selection and descriptive statistics. Table 3 provides the complete list of bank samples.

Bank efficiency analysis

Total efficiency

We analyze bank efficiency using three efficiency types: Meta Frontier (MF), Group Frontier (GF), and TGR. We employ a four-quadrant method with total efficiency improvement on the vertical axis and total efficiency on the horizontal axis, using the median as the dividing criterion. This results in a four-quadrant diagram appear in Fig. 2. The quadrants are defined as follows: Quadrant I (high efficiency-positive growth), Quadrant II (low efficiency-positive growth), Quadrant III (low efficiency-negative growth), and Quadrant IV (high efficiency-negative growth). If a bank is in Quadrant I, then it not only maintains a high level of efficiency, but also demonstrates a growth trend.

Under MF the average efficiency of Chinese banks from 2019 to 2023 is 0.650 with a median of 0.649. There are 13 banks in Quadrant I, 15 in Quadrant II, 6 in Quadrant III, and 8 in Quadrant IV. Most banks are concentrated in Quadrants I and II, indicating that the majority exhibit positive growth in total efficiency and improvements in technological levels. Under GF the average efficiency is 0.925 with a median of 0.967. There are 2 banks in Quadrant I, 11 in Quadrant II, 8 in Quadrant III, and 3 in Quadrant IV. Compared to MF, efficiency performance under GF improves. Although only 2 banks are in Quadrant I, 18 banks show zero efficiency growth, with 16 of them having efficiency values close to or at the effective state. This occurs, because the DEA efficiency measurement evaluates relative efficiency, and GF improvement results from the restructuring of meta-frontier DMUs, leading to convergence of the group frontier. Therefore, it is necessary to use the meta-frontier approach to assess bank efficiency. From the perspective of TGR, the average efficiency is 0.690 with a median of 0.687, indicating a gap between the actual technological levels of banks and the potential optimal levels, with an overall improvement potential of 31%. There are 13 banks in Quadrant I, 14 in Quadrant II, 7 in Quadrant III, and 8 in Quadrant IV. Over half of the banks exhibit positive efficiency growth, and the gap with the overall optimal level is narrowing.

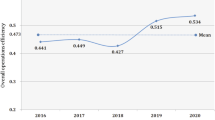

Stage efficiency

To explore the efficiency of Chinese banks from an internal perspective, this study opens the “black box” by examining their efficiency at different stages. Figure 3 illustrates the average efficiency and trends across stages. The values of MF, GF, and TGR vary significantly across stages, showing that MF > TGR > GF. Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of the average TGR efficiency for each of the 42 banks at every stage and identifies the specific stages each bank should prioritize for improvement.

Enterprise risk stage

The outputs of this stage are default risk and business risk. Higher efficiency values indicate higher risk levels. From 2019 to 2023, the average efficiency values are 0.8994, 0.9426, 0.9114, 0.9318, and 0.9442, respectively, suggesting 7–10% improvement potential. Figure 3a shows the trends of MF, GF, and TGR efficiency values are generally consistent during the study period. Although efficiency values decline slightly between 2020 and 2021, they exhibit a small fluctuating upward trend overall, indicating a gradual increase in enterprise risk.

Only 10 banks have efficiency values below 0.9, meaning lower risk. These banks include BOC, CCB, CMB, HXB, ICBC, CZB, CEB, ABC, CITIC, and CIB. They are either state-owned commercial banks or joint-stock commercial banks. State-owned commercial banks, backed by national ownership, have strong financial resources, high credibility, and robust risk resilience. Joint-stock commercial banks focus on market-oriented operations with strong financial innovation capabilities and advanced risk assessment technologies and management methods. Banks with poor enterprise risk efficiency are primarily urban commercial banks and rural commercial banks. Among them, PSBC, LZCB, NBCB, ZRCB, WRCB, and SRCB face significant enterprise risks. Urban commercial banks are highly susceptible to local economic fluctuations and industrial restructuring, while rural commercial banks are significantly affected by uncertainties in agricultural production and rural enterprise operations, leading to higher market risks.

Operation stage

In this stage the efficiency values represented by MF, GF, and TGR remain stable and consistently high. This indicates that Chinese banks have maintained robust operational performance in recent years with significant improvements in business process optimization. They demonstrate strong cost control capabilities, particularly in managing administrative and employee expenses. Among all banks, only CQRCB exhibits lower efficiency, while 24 banks achieve optimal efficiency levels. Overall, Chinese banks have shown excellent operational performance in recent years with stable and growing business outcomes.

Sustainability stage

In this stage the GF efficiency values remain stable and close to 1. In contrast, the MF and TGR efficiency values exhibit significant fluctuations, initially rising, then declining, and rising again. This indicates that while banks perform well in sustainability management within their groups, there is still room for improvement compared to the industry’s optimal technological level. Over 70% of banks successfully implement sustainable development principles and effectively integrate resources. However, 12 banks have efficiency values below 0.9 and need to prioritize improving their sustainability performance. These banks include HXB, CZB, BOB, CEB, QLB, QRCB, CITIC, GYCB, PAB, JSBC, XAB, and BZZH.

Market stage

In this stage the GF efficiency values remain stable and relatively high, while the MF and TGR efficiency values show a continuous upward trend. This indicates that banks have actively expanded into new market areas and business domains in recent years, adopting forward-looking strategic initiatives that have significantly driven efficiency improvements. However, 80% of banks have not achieved optimal market efficiency. Only 8 banks exhibit market efficiency above 0.9: ABC, CIB, CMB, NBCB, BOC, CCB, ICBC, and RFBC. Half of these are state-owned commercial banks, demonstrating their ability to effectively allocate resources, adapt to market conditions, and maintain strong competitiveness and advantages. These banks play a critical role in enhancing overall market efficiency and ensuring stable development. Despite significant progress in market efficiency, Chinese banks still lag behind in other stages, indicating the need for continued efforts.

The enterprise risk stage shows a slight fluctuating upward trend in efficiency. State-owned commercial banks and joint-stock commercial banks face lower enterprise risks, while urban commercial banks and rural commercial banks perform poorly in this stage. Therefore, it is necessary to further analyze the efficiency performance of heterogeneous banks. The operational stage exhibits stable and high efficiency levels. The sustainability stage shows significant fluctuations. In the market stage, efficiency values are rising, but 80% of banks still fall short of optimal market efficiency. State-owned commercial banks play a pivotal role in enhancing and stabilizing overall market efficiency. Comparing the stages, the enterprise risk and sustainability stages share similar fluctuation trends, while the market stage shows a notable gap compared to other stages. Further analysis is needed to explore the correlations and coupling coordination among these stages.

Robustness tests

In order to assess bank efficiency more comprehensively, this paper performs robustness checks on the weights of the entropy method and the sample of banks. Table 5 shows the efficiency values for each bank under the five scenarios. The weights of the entropy method are tested as follows: the weights are recalculated by changing the key input variables of the entropy method by excluding idle funds, excluding sales growth rate, and operating costs, respectively, and the efficiency is re-measured with the new weights. The test for the bank sample is to re-measure efficiency by excluding high-leveraged banks (leverage ratio greater than 93), and outlier banks, respectively. It can be seen that the efficiency values of the banks under different scenarios fluctuate less and the ordering of the efficiency values remains highly consistent, which fully demonstrates the robustness of the benchmark efficiency estimation results.

Stage relevance analysis

Correlation analysis

The impact of enterprise risk may be lagged or partially mitigated by bank policies. For example, banks’ risk management policies may dampen the immediate transmission of corporate credit risk to the financial system. To further explore the relationships between these stages, we conduct correlation tests and present the results in Table 6.

The correlation coefficient between enterprise risk and operational efficiency is −0.160, indicating a negative relationship. This validates the inclusion of enterprise risk in the bank efficiency evaluation framework. As risk increases, operational efficiency tends to decline. Risk transmission has immediate effects at the operational level, which is consistent with the current situation of financing difficulties for Chinese SMEs. Risk factors can hinder daily production and operational activities, leading to more cautious or conservative decision-making, which reduces decision-making efficiency and disrupts operational rhythms. Enterprise risk is not significantly correlated with sustainability efficiency, suggesting that ESG measures may create a risk buffer. Enterprise risk is weakly correlated with market efficiency, reflecting the filtering effect of investors on short-term enterprise risk. It is also a side note that China’s banking sector partially absorbs enterprise risk through policy interventions.

The correlation coefficient between sustainability efficiency and market efficiency is 0.430, showing a positive relationship. This suggests that improvements in sustainability efficiency positively contribute to market efficiency, creating a mutually reinforcing effect. In the sustainability stage, strong performance in areas such as green development, social responsibility, and long-term strategic planning can attract environmentally conscious consumers and socially responsible investors, thereby expanding market share and enhancing competitiveness. Conversely, improvements in market efficiency, such as increased product sales and resource accumulation through effective marketing, can provide financial support for sustainability projects, further driving continuous improvements in sustainability efficiency and forming a virtuous cycle. However, the correlation between operational efficiency and sustainability efficiency is not statistically significant.

Using a 1-period lag for enterprise risk, the results show that the correlation coefficients for enterprise risk lagged one period are highly consistent with the results for the current period, indicating that the immediate effect of risk transmission is robust.

Sensitivity test of stage weights

In the coupling coordination model, the contribution weights of each system are exogenous and can be adjusted according to the relative importance of each stage. In order to better compare the results of different weights, this paper conducts a weight sensitivity analysis based on univariate perturbation and extreme scenario pressure for the four stages. Taking the four stages with equal weights (0.25) as the base case, univariate perturbation is a perturbation of +10% and −10% applied to each stage weight in turn. Three scenarios were tested for extreme scenario stress, namely concentrated risk outbreak, market failure, and intensified policy intervention. The weighted results of the different scenarios are shown in Table 7. It can be found that the absolute change in the coupling coordination degree (D-value) under the alternative scenarios is less than 3% when using different weights, confirming the robustness. In this paper, the four components are considered to be important for the development of bank vendors, and thus they are each assigned a value of 0.25 (Wang, 2025).

Coupling coordination analysis

Table 8 presents the coupling coordination levels across different stages for the banks. During the study period the degree of coupling coordination of all banks exceeds 0.6, indicating a high level of coordination. This suggests that Chinese banks have achieved strong collaboration among their enterprise risk, operational, sustainability, and market systems. Among the 42 banks, 28 show an increase in coupling coordination, while 10 maintain a degree of coupling coordination above 0.9 throughout the study period, reaching an extremely coordinated state. These banks include ICBC, CEB, PAB, CMBC, PSBC, CITIC, GYCB, BOS, XAB, and SRCB. Overall, most banks exhibit either an improvement or a consistently high level of coupling coordination. BOC and BOCOM show the most significant changes. BOC’s degree of coupling coordination rises from 0.6765 to 0.9779, while BOCOM’s declines from 0.8151 to 0.6384.

Efficiency analysis of heterogeneous banks

Analysis of grouping efficiency values

Based on ownership types of the banks, the sample is divided into four groups: Group 1 (state-owned commercial banks), Group 2 (joint-stock commercial banks), Group 3 (urban commercial banks), and Group 4 (rural commercial banks). The efficiency of each group relative to MF and GF is calculated, as shown in Table 9. By comparing MF and GF efficiencies across different stages and groups, we observe that GF ≥ MF in all cases.

During the study period, Group 1 achieves optimal efficiency in both the operational and sustainability stages, demonstrating superior resource allocation compared to other bank types. In the market stage, Group 1 improves from near-optimal MF efficiency in 2019–2021 to optimal efficiency in 2022–2023. This improvement may be attributed to the initial negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on market efficiency in 2019–2021, followed by a recovery as domestic pandemic control measures took effect in 2022–2023 (Gulati et al., 2023). Compared to other bank types, state-owned commercial banks exhibit greater resilience and controllable overall risk when facing pandemic shocks. Group 2 shows the following efficiency hierarchy relative to the industry’s optimal technological level: operational efficiency > sustainability efficiency > market efficiency. This group performs the worst in the sustainability stage among all bank types. Group 3 exhibits a similar efficiency pattern to Group 2 with operational efficiency > sustainability efficiency > market efficiency. However, this group performs the worst in the market stage among all bank types. Group 4 performs the worst in the enterprise risk stage compared to other bank types.

From the meta-frontier perspective, most banks exhibit the following efficiency hierarchy: operational efficiency > sustainability efficiency > market efficiency. This reflects the difference between banks’ pursuit of short-term goals and their long-term balanced development. In the short term, banks can rapidly improve operational efficiency by actively expanding business and optimizing processes. However, sustainability efficiency involves broader long-term factors, including environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations. Specifically, investments in green finance projects and the establishment of long-term monitoring and incentive mechanisms require time and resources, which may result in operational efficiency surpassing sustainability efficiency in the short term.

The higher sustainability efficiency compared to market efficiency can be attributed to two main factors. First, banks accumulate assets with long-term value that may not be fully recognized by the market due to information asymmetry. Second, real financial markets are not always fully efficient. Market efficiency focuses on how well prices reflect market information, but does not account for long-term sustainability strategies. In contrast, sustainability efficiency directly incorporates the value of long-term strategies, explaining why it tends to exceed market efficiency.

Given that enterprise risk efficiency is the weakest among the stages, a closer examination of the detailed enterprise risk values in Fig. 4 reveals the following. In Group 1, only one bank achieves optimal efficiency, accounting for 20% of the group. In Group 2, 7 banks reach optimal efficiency, representing 70% of the group. In Group 3, 7 banks achieve optimal efficiency, constituting 76% of the group. In Group 4, 9 banks attain optimal efficiency, making up 90% of the group, with 3 banks maintaining optimal efficiency throughout the study period. Based on these findings, we preliminarily conclude that Group 4 faces the highest enterprise risk, followed by Group 3, while Group 1 exhibits the lowest risk. This suggests that rural commercial banks, due to instability of rural economies, environmental vulnerabilities, and their smaller scale and lower capital levels, encounter the highest enterprise risk. Urban commercial banks and joint-stock commercial banks follow, while state-owned commercial banks demonstrate relatively stronger risk management capabilities and lower risk levels.

Analysis of efficiency differences

Following the approach of Sun et al. (2017) we examine the number of banks located on MF and GF across the four groups from 2019 to 2023, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The red line encloses the blue line, indicating that the number of banks on the GF significantly exceeds those on MF, particularly for Group 2 and Group 3. In the market stage, Group 2 has 41 observations on GF, but only 15 on MF, while Group 3 has 64 observations on GF, but only 26 on MF. This suggests that most joint-stock commercial banks and urban commercial banks have not optimized technologies conducive to improving market efficiency. Similarly, in the sustainability stage the gap between MF and GF for Groups 2 and 3 indicates that most banks in these groups have also failed to adopt technologies that support sustainable development. These findings further validate the analysis conclusions presented in Section “Analysis of Grouping Efficiency Values”.

To further determine whether significant differences exist between the four groups on MF and GF, we conduct Mann–Whitney U tests for each group’s efficiency. The results are in Table 10. The tests show that the operational efficiency, sustainability efficiency, and market efficiency of Group 1, the enterprise risk efficiency and operational efficiency of Group 3, and the sustainability efficiency of Group 4 all support the null hypothesis. This indicates that the differences between MF and GF efficiencies for these groups are not statistically significant. For the other groups, the p-values are less than 0.05, leading to a rejection of the null hypothesis and suggesting significant differences between MF and GF efficiencies.

Technology gap analysis

The Kruskal-Wallis H test is used to analyze differences among the four bank groups. The results are in Table 11. The p values for efficiency at each stage are statistically significant, leading to a rejection of the null hypothesis. This indicates that the differences in enterprise risk efficiency, operational efficiency, sustainability efficiency, and market efficiency among the banks are significant.

We further investigate the technology gaps among the four bank groups by visualizing the efficiency gaps at each stage using box plots, as shown in Fig. 6. The findings are as follows.

(a) The ranking of the gaps between each group’s risk levels and the overall optimal level is Group 4 > Group 3 > Group 2 > Group 1. This is consistent with the analysis in Section “Analysis of Efficiency Differences”. (b) The TGR efficiency values in the operational stage for Groups 1 and 3 are higher than those for Groups 2 and 4, indicating that Groups 1 and 3 possess superior operational technologies. Banks in Groups 2 and 4 should improve their operational-related technologies. (c) The technology gap in the sustainability stage for Group 2 is lower than that of other groups, suggesting significant potential for sustainable development. These banks should increase investments in ESG-related technologies to enhance their sustainability capabilities. (d) The market stage’s TGR for Groups 2, 3, and 4 shows a significant gap compared to Group 1, with most banks in these groups exhibiting low market efficiency.

The technology gaps among the four groups overall vary significantly. Group 1 achieves optimal efficiency or performs above the median in all three stages. This demonstrates that state-owned commercial banks maintain high and consistent technological maturity in risk management, operational optimization, and other areas.

For Group 2, the technology gaps in the sustainability stage are widely dispersed, with most banks performing below average. This highlights the weak link in sustainable development technologies among joint-stock commercial banks. They should increase their funding of green finance, sustainable investments, and other related technologies, while establishing long-term environmental and social risk management systems to enhance their competitiveness in sustainability.

Group 3 exhibits technology gaps mostly above the median across stages, but performs poorly in the market stage. This suggests that urban commercial banks should focus more on market-oriented strategies, develop personalized and differentiated service systems, and optimize marketing channels and strategies.

Group 4 also faces low market stage technology levels, but performs well in the sustainability stage. Rural commercial banks prioritize social benefits and long-term business planning, but underperform in market-oriented activities. This aligns with reality, as rural commercial banks, rooted in rural areas, often allocate resources to long-term initiatives such as rural development and farmers’ pension security. However, their reliance on traditional business models and slower adoption of innovative management techniques may limit their market competitiveness. Additionally, their limited use of big data analytics to precisely target customer needs restricts their market influence.

Conclusions and recommendations

Main findings

Enterprise risk is a critical factor influencing both short-term revenue and long-term development for banks. Therefore, assessing risks and evaluating efficiency at each stage are key priorities for banks. The main findings of this study are as follows.

(a) Efficiency analysis shows that most Chinese banks experienced positive growth in total efficiency from 2019 to 2023 with improvements in technological levels. However, a gap remains between their actual technological levels and the potential optimal levels, indicating an overall improvement potential of 31%.

(b) Enterprise risk efficiency exhibits a slight fluctuating upward trend, with risk levels ranked as follows: state-owned commercial banks < joint-stock commercial banks < urban commercial banks < rural commercial banks. Operational efficiency remains stable and at a high level. Sustainability efficiency shows significant fluctuations, with over 70% of banks implementing sustainable development principles. Market efficiency is on an upward trend, but 80% of banks still fall short of optimal market efficiency.

(c) Correlation analysis reveals a negative relationship between enterprise risk and operational efficiency, validating the inclusion of enterprise risk in the bank efficiency framework. A positive correlation exists between sustainability efficiency and market efficiency, meaning that improvements in sustainability efficiency positively contribute to market efficiency, creating a mutually reinforcing effect.

(d) Coupling coordination analysis shows that the degree of coupling coordination of all banks exceeds 0.6 during the study period. This reflects strong collaboration among enterprise risk, operational, sustainability, and market systems.

(e) Heterogeneous bank efficiency analysis demonstrates that state-owned commercial banks exhibit the strongest risk resilience, achieve optimal efficiency in the operational and sustainability stages, and lead in market efficiency. Joint-stock commercial banks need to focus on improving sustainability and market efficiency, urban commercial banks should prioritize market efficiency, and rural commercial banks must address enterprise risk efficiency. From a meta-frontier perspective, most banks show the following efficiency hierarchy: operational efficiency > sustainability efficiency > market efficiency.

(f) Technology gap analysis highlights significant differences in operational, sustainability, and market efficiencies among banks. The ranking of risk gaps relative to the optimal level is Group 4 > Group 3 > Group 2 > Group 1. Group 2 banks show the smallest technology gap in the sustainability stage, while Groups 2, 3, and 4 lag significantly behind Group 1 in market efficiency.

Policy recommendations

The findings of this paper provide policymakers, institutional leaders, and industry practitioners with information that can be used for decision-making.

(a) For policymakers, it is necessary to base on the characteristics of the correlation between risk and efficiency of the banking industry as a whole and formulate differentiated guidance policies. Incorporate efficiency indicators at various stages into regulatory ratings to transform resource advantages into industry leadership. At the same time, banks are required to regularly disclose the progress of improving the risk early warning mechanism and strengthen the demonstration role of macro risk prevention and control. Supportive policies need to be formulated in conjunction with local economic characteristics.

(b) For leaders of banking institutions, banks of different natures have different management strategies, specifically:

State-owned commercial banks should consolidate their advantages in the operational and sustainability stages while exploring potential improvements in market efficiency. Leveraging their abundant resources and extensive customer base, they should invest more in market trend research and customer demand analysis.

Joint-stock commercial banks should prioritize the development and application of sustainability technologies. After establishing dedicated sustainability research teams or departments, they should delve into green finance and formulate tailored sustainability strategies. Investments in environmental technologies and social responsibility projects can enhance long-term efficiency and market competitiveness. Additionally, they should optimize risk management systems to balance risk and return.

Urban commercial banks should focus on improving market-stage technologies. By enhancing market research and analysis, they can precisely target customer segments and develop differentiated financial products and services aligned with local economic characteristics and market demands. Strengthening collaborations with local governments and enterprises, they should actively participate in regional economic development projects to expand business channels and increase market share.

Rural commercial banks play a vital role in supporting the long-term stability of rural societies, but need to address weaknesses in operational and market efficiencies to achieve comprehensive sustainable development. By automating and digitizing processes, they can accelerate transaction speeds, reduce operational costs, and improve efficiency. Strengthening risk management capabilities is essential to address unique rural challenges.

(c) For industry practitioners, there is a need to break away from the traditional risk control framework and incorporate “efficiency-risk linkage thinking” into their daily work. Cross-stage collaboration should be strengthened, for example, operating departments should share customer data with marketing departments to avoid wasting resources.

In summary, given the negative correlation between enterprise risk and operational efficiency, the entire banking industry should prioritize risk management. Simultaneously, banks should enhance industry collaboration, share advanced technological experiences and risk management practices, and collectively improve the overall technological level and risk management capabilities of the banking sector. This will enable banks to adapt to the increasingly complex and dynamic financial market environment and to meet evolving societal demands.

Outlook

While the findings of this study provide insights into the relationships among enterprise risk efficiency, sustainability efficiency, and market efficiency for Chinese banks, they share limitations common to similar research. On the one hand, generalizability of the conclusions may be limited, because the selected banks are from a developing country. Thus, the findings and recommendations may not fully apply to developed or less developed nations. On the other hand, there are other important factors influencing bank efficiency that warrant further investigation. Future research could explore the efficiency performance of banks in a broader range of countries, incorporate additional exogenous variables into the framework, and consider more influencing factors to enhance the universal applicability of the results and to more accurately depict the interactions between enterprise risk and bank performance.

Data availability

All data obtained/generated has been provided.

References

Adeabah D, Andoh C (2020) Cost efficiency and welfare performance of banks: evidence from an emerging economy. Int J M anag Financ 16(5):549–574

Aevoae GM, Andrieș AM, Ongena S, Sprincean N (2023) Esg and systemic risk. Appl Econ 55(27):3085–3109

Bagade S, Chitta SS, Jain RK, Padmavathi V, Prasad K (2023) Association between financial efficiency and credit risk of Smes—a Study using Dea and Altman Z-Score. Fiib Bus Rev 12(2):1177182

Batae OM, Dragomir VD, Feleaga L (2021) The relationship between environmental, social, and financial performance in the banking sector: a European study. J Clean Prod 290:125791

Battese G, Rao D (2002) Technology gap, efficiency, and a stochastic metafrontier function. Int J Bus Econ 1:87

Battese G, Greene W, O’Donnell C, Podinovski V (2004) A metafrontier production function for estimation of technical efficiencies and technology gaps for firms operating under different technologies. J Product Anal 21:91–103

Bouattour A, Kalai M, Helali K (2024) The non-linear relationship between ESG performance and bank stability in the digital era: new evidence from a regime-switching approach. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–17

Bruno E, Iacoviello G, Giannetti C (2024) Bank credit loss and ESG performance. Financ Res Lett 59:104719

Cai Q, Wu Q, Wu G (2024) Local hidden debt, bank risk perception and corporate credit availability. China Indus Econ 15:112–130

Chaoqun H, Shen W, Huizhen J, Wei L (2024) Evaluating the impact of uncertainty and risk on the operational efficiency of credit business of commercial banks in China based on dynamic network Dea and Malmquist Index Model. Heliyon 10(1):e22850

Chen H, Du X, Wang L (2019) The impact of comprehensive risk management on corporate operational efficiency-an empirical study based on 45 life insurance companies. Insurance Res 39(2):3–15

Chen YC, Lin TY, Chiu YH, Yang C (2024) An exploration of operational efficiency, market efficiency, and sustainable development in the banking industry. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 31(5):4819–4848

Chiaramonte L, Dreassi A, Girardone C, Piserà S (2022) Do ESG strategies enhance bank stability during financial turmoil? Evidence from Europe. Eur J Financ 28(12):1173–1211

Di Tommaso C, Thornton J (2020) Do ESG scores effect bank risk taking and value? Evidence from European Banks. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(5):2286–2298

Fang Z, Gao X, Sun C (2020) Do financial development, urbanization and trade affect environmental quality? Evidence from China, J Clean Prod 259:120892

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Whittaker G (2007) Network Dea. Modeling Data Irregularities and Structural Complexities in Data Envelopment Analysis. Springer

Gulati R (2022) Global and local banking crises and risk-adjusted efficiency of indian banks: are the impacts really perspective-dependent? Quart Rev Econ Finance 84:23–39

Gulati R, Charles V, Hassan MK, Kumar S (2023) Covid-19 crisis and the efficiency of Indian Banks: have they weathered the storm? Socio Econ Plan Sci 88:101661

Hamid N, Ramli NA, Hussin SAS (2017) Efficiency measurement of the banking sector in the presence of non-performing loan. In AIP conference proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC

Huang CM, Yang W, Zeng RQ (2020) Analysis on the efficiency of risk management in the Chinese listed companies. Mathematics 8:1831

Hughes JP, Mester LJ (2013) Who Said Large Banks don’t experience scale economies? Evidence from a risk-return-driven cost function. J Financ Intermediation 22(4):559–585

Huizhi L, Xianghua Y (2023) The impact of uncertain financial risk on the operation efficiency of banks. Heliyon 9(12):e21378

Hwang RH, Kim SH, Lee DW, Nam DW (2012) A directional distance function approach on the efficiency of Chinese Commercial Banks. J Korea Soc Ind Inf Syst 17(2):81–94

Islam MU, Hamid BA, Shahid MN (2025) Esg activities and bank performance with the moderating influence of competition and regulatory quality: a study in the organization of Islamic Countries. Int J Islamic Middle East Financ Manag 18(2):441–466

Jiang H, Jia J, Chapple L (2024) Enterprise risk management and investment efficiency: Australian evidence from risk management committees. Aust J Manag 49(3):366–402

Kamarudin F, Mohamad Anwar NA, Md. Nassir A, Sufian F, Tan KM, Iqbal Hussain H (2022) Does Country Governance and Bank Productivity Nexus Matters? J Islamic Mark 13(2):329–380

Kamarudin F, Nordin BAA, Nasir AM (2013) Price efficiency and returns to scale of banking sector in gulf cooperative council countries: empirical evidence from islamic and conventional banks. Econ Comput Econ Cybern Stud Res 47(3):215–236

Kao C (2009) Efficiency decomposition in network data envelopment analysis: a relational model. Eur J Operat Res 192(3):949–962

Lee K, Saen RF (2012) Measuring corporate sustainability management: a data envelopment analysis approach. Int J Prod Econ 140(1):219–226

Lee PF, Lam WS, Lam WH (2023) Performance evaluation of the efficiency of logistics companies with data envelopment analysis model. Mathematics 11(3):718

Lee S, Chang TH, Chiu YH (2024) Exploring the influence of fintech patents on operation efficiency and market efficiency in Taiwan’s commercial banking sector‐meta entropy dynamic two‐stage Ddf model. Manag Decis Econ 45:4276

Liao SC, Lin TY, Chang TH, Chiu YH (2024) Non‐performance loans, operation, and recycle efficiency analysis—dynamic two‐stage directional distance function recycle with assurance regions model. Manag Decis Econ 45(2):952–974

Liu S, Jin J, Nainar K (2023a) Does ESG performance reduce Banks’ nonperforming loans? Financ Res Lett 55:103859

Liu T, Chen X, Liu J (2023b) Economic policy uncertainty and enterprise financing efficiency: evidence from China. Sustainability 15(11):8847

Mia MA, Rangel GJ, Nourani M, Kumar R (2023) Institutional factors and efficiency performance in the global microfinance industry. Benchmarking Int J 30(2):433–459

Nourani M, Malim NAK, Mia MA (2020) Revisiting efficiency of Microfinance Institutions (Mfis): an application of network data envelopment analysis. Econ Res -Ekonomska Istraživanja 34(1):1146–1169

Obadire AM, Moyo V, Munzhelele NF (2022) Basel III capital regulations and bank efficiency: evidence from selected African Countries. Int J Financ Stud 10(3):57

O’Donnell C, Rao D, Battese G (2008) Metafrontier frameworks for the study of firm-level efficiencies and technology ratios. Empir Econ 34(2):231–255

Olson DL, Wu D (2023) Data Envelopment Analysis. In: Enterprise Risk Management Models: Focus on Sustainability, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp 105–117

Saif-Alyousfi AYH, Saha A, Alshammari TR (2023) Bank diversification and ESG activities: a global perspective. Econ Syst 47(3):101094

Shannon CE (1948) A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J 27(4):623–656

Shi X, Chen Y, Xia M, Zhang Y (2022) Effects of the talent war on urban innovation in China: a difference-in-differences analysis. Land 11(9):1485

Sulistyawati SN, Suryani AW (2022) Achieving operational efficiency through risk disclosure. Asian J Bus Account 15(1):149–178

Sun J, Wang C, Ji X, Wu J (2017) Performance evaluation of heterogeneous bank supply chain systems from the perspective of measurement and decomposition. Comput Ind Eng 113:891–903

Thaker K, Charles V, Pant A, Gherman T (2022) A Dea and random forest regression approach to studying bank efficiency and corporate governance. J Operat Res Soc 73(6):1258–1277

Tone K, Tsutsui M (2014) Dynamic Dea with network structure: a slacks-based measure approach. Omega 42(1):124–131

Tsolas IE (2021) Firm credit scoring: a series two-stage Dea bootstrapped approach. J Risk Financ Manag 14(5):214

Ullah S, Majeed A, Popp J (2023) Determinants of Bank’s efficiency in an emerging economy: a data envelopment analysis approach. Plos ONE 18(3)

Wang X (2022) Research On Fintech and Total Factor Productivity of Listed Commercial Banks-Based On Three-Stage Sbm-Dea Model. Technol Econ 41(08):34–46

Wang X (2025) Research on dynamic monitoring and early warning for innovation ecosystem resilience: evidence from China. Systems, 13(2):102

Wen J, Feng G (2018) Venture capital and corporate innovation: the trade-off between value-added and capture. Econ Res 53(02):185–199

Xie Q, Xu Q, Chen L, Jin X, Li S, Li Y (2022) Efficiency evaluation of China’s listed commercial banks based on a multi-period leader-follower model. Omega 110:102615

Xuanling MA, Meng JI (2023) Analysis on liquidity risk management of monetary and financial services based on the goal of financial stability. Rom J Econ Forecast 26(2):72

Yan X, Feng X (2021) Research on the operational efficiency of rural small and medium-sized banks - an analysis based on Dea-Bcc Model and Dea-Malmquist Index Model. Financ Regulation Res (11):1–17

Zhang K, Zhou X (2022) Is promoting green finance in line with the long-term market mechanism? The perspective of Chinese commercial banks. Mathematics 10(9):1374

Zhang L, Dou Y, Wang H (2023) Green supply chain management, risk-taking, and corporate value—dual regulation effect based on technological innovation capability and supply chain concentration. Front Environ Sci 11:1096349

Zhao J, Wu R (2024) Efficiency measurement and analysis of influencing factors in commercial banks. Stat Decis Mak 40(12):157–161

Zhu N, Zeng H, Yu Z (2023) Research on the operational efficiency of Chinese commercial banks - an empirical analysis based on multi-stage cooperative network Dea. Financ Res 518(8):37–54

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Fujian Provincial Social Science Fund Project [Grant No.F12024XZB002], Major Project of Fujian Provincial Social Science Base [Grant No.FJ2022JDZ024].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhong Fang, Ying Chen and Yung-ho Chiu wrote the main manuscript text and Lingyi Chen took charge of the English polishing of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval & Consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Z., Chen, Y., Chen, L. et al. Bank efficiency estimation considering enterprise risk: entropy meta two parallel three-stage dynamic DDF model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05991-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05991-6