Abstract

This study evaluates the insurance-like effects of brand equity and corporate social responsibility (CSR) on the financial value of firms affected by Chinese product-harm crises. It also explores how socio-cognition influences insurance mechanisms within this collectivist society. The results find that the financial losses of a crisis are contingent upon its severity, with less serious events failing to generate meaningful valuation declines. Both brand equity and CSR can mitigate financial losses and offer insurance-like protections for affected firms. However, CSR demonstrates a stronger insurance-like effect on financial value because of the socio-cognition in this collectivist society. The findings presented herein support the argument that cultural socio-cognition can contribute to investor judgments and provide a theoretical basis for understanding the role of cultural socio-cognition in insurance mechanisms. In doing so, this study validates the distinct insurance-like effects of brand equity and CSR on financial value, while establishing cultural socio-cognition as a moderating factor in risk management, thereby expanding the theoretical boundaries of risk management. Additionally, it offers practical guidance for firms operating in diverse markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Product-harm crises, characterized by actual or potential threats to consumer health and safety, represent critical issues that have garnered significant social attention (Utz, 2019). Currently, such crises have persistently occurred across diverse markets and societies (Cleeren et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2023). Their occurrence implies that affected firms deviate from general social expectations (Shea and Hawn, 2019; Sharpe and Hanson, 2021), potentially causing stakeholders to form negative judgments of those firms. Accordingly, product-harm crises are generally perceived to damage the financial value of affected firms (Ni et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2016).

Risk management research has primarily focused on penance and insurance mechanisms to explore ways to mitigate risks (Kang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2023). Penance mechanisms suggest that crisis response strategies or recovery strategies, such as price adjustments, advertising, and ex-post corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, can mitigate risks posed by product-harm crises (Cleeren, 2015; Cleeren et al., 2017; Noack et al., 2019). However, once a crisis occurs, losses are inevitable, even with optimal recovery strategies. It is therefore necessary to seek ex-ante strategies and understand their insurance mechanisms.

Previous research, which has primarily been conducted in individualistic contexts, has demonstrated that two firm-level strategies (i.e., consumer-based brand equity, hereafter brand equity, and CSR) can provide insurance-like protection for affected firms (Hsu and Lawrence, 2016; Kim and Woo, 2019). More precisely, high brand equity operates through market logic, which emphasizes efficiency, competition, and performance, to positively influence stakeholder perceptions. It thereby enhances consumer trust in product quality and strengthens investors’ confidence in the firm’s capability to produce high-quality products and to weather crises (Ahmad et al., 2022). In contrast, high CSR engagement leverages family logic, which prioritizes care, trust, and social responsibility, to influence stakeholders’ attributions. With higher CSR, stakeholders are more likely to view the firm as ethically responsible and to attribute the crisis to managerial missteps rather than malicious intent (Kim and Woo, 2019). Together, these two strategies function as “insurance” by protecting stakeholders’ trust in the firm’s capability or character and attenuating their negative judgments (Bitektine and Song, 2021).

As demonstrated, risk management literature has primarily examined insurance mechanisms in individualistic societies (Liu et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021), with particular attention paid to firm-level contingencies (Cleeren et al., 2017). However, firms operate in diverse cultural contexts, where the social cognition differs significantly (Au et al., 2018). Cultural studies have confirmed that cultural factors influence individual behavior through socio-cognition (Tan et al. 2019; Kaustia et al., 2023). Notably, Griffin et al. (2021) demonstrate that Hofstede’s collectivism dimension of culture affects individuals’ behavior via socio-cognition, implying that stakeholders in collectivist societies may interpret firm strategies and respond to product-harm crises differently from those in individualistic societies. Despite these findings, the risk management research still lacks the integration between cultural social cognition and firm-level responses. To bridge this gap, this study incorporates cultural social cognition as a moderating factor in risk mitigation.

Specifically, we investigate the insurance mechanisms and the role of socio-cognition within a collectivist context. We use the Chinese society as a paradigmatic case. In Chinese society, brand equity is important because of market competition, and CSR activities are becoming increasingly prevalent due to government involvement and social promotion (Yue et al., 2025). Meanwhile, Chinese collectivism emphasizes familial obligations and collective welfare over individual interests (Wang and Juslin, 2009), which can profoundly influence social cognitive processes (Du, 2016). We propose that this cultural lens alters how stakeholders perceive and react to firm strategies when market or family logic is activated during product-harm crises. Consequently, we examine whether brand equity and/or CSR retain their insurance-like effects in this collectivist setting and how socio-cognition moderates the insurance mechanisms by influencing stakeholder cognition and behavior.

This study makes three significant contributions to the relevant literature. First, by integrating Chinese cultural norms into the analytical framework, we demonstrate that the insurance-like effect of firm strategy intensifies when aligned with societal values. This highlights the moderating role of cultural social cognition in risk management and advances the understanding of risk management theory. Second, building on Hsu and Lawrence’s (2016) work, we show that brand equity maintains its insurance-like protections for affected firms in the collectivist context. This finding confirms the validity of established insurance mechanisms, while extending the boundaries of risk management theory (Bitektine and Song, 2021). Finally, the results indicate that family logic prevails in Chinese product-harm crises, making CSR more effective than brand equity in mitigating financial penalties. This finding substantiates the cultural specificity of insurance mechanisms and could explain some cases where CSR is relatively effective in collectivist contexts (Zhang et al. 2014).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section “Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis Development” lays out the theoretical foundation for integrating risk management and socio-cognition in a collectivist context and develops the key assumptions based on this theoretical foundation. Section “Methodology” shows sample construction, variable measurements, and interaction models. Section “Results” presents empirical analyses of the insurance-like effects of brand equity and CSR. Section “Discussion” provides discussion based on the research analyses. Finally, Section “Conclusion and Future Research” concludes this article.

Theoretical foundation and hypothesis development

Theoretical foundation

Product-harm crises refer to issues where products pose a threat to consumer health and/or safety (e.g., recalls due to food safety concerns). Therefore, such crises represent critical issues where market and societal concerns intersect. These crises threaten consumer welfare while also impacting broader familial networks (e.g., affecting parents, children, and siblings), thereby simultaneously activating market and family logic (Bitektine and Song, 2021). Once triggered, these logics reshape stakeholder perceptions and judgment, ultimately influencing the financial value of the affected firms (Ngoye et al., 2019).

In general, market logic prioritizes efficiency, competition, and profit maximization, forming the cornerstone of economic systems. Under this logic, investors primarily focus on the firm’s financial performance and market competitiveness (Bitektine and Song, 2021). Meanwhile, family logic emphasizes collective welfare, social responsibility, and harmony, which are related to home, mutual support, and concern for the interests of others (Glaser et al., 2017; Bitektine and Song, 2021). This logic urges investors to assign greater importance to the firm’s social image and ethical performance.

Risk management

Risk management research has shown that brand equity and CSR can have insurance-like effects on financial value during a product-harm crisis (Hsu and Lawrence, 2016; Kong et al., 2019; Kim and Park, 2020). Here, brand equity, a direct outcome of market competition, is primarily formed and accumulated through market mechanisms (e.g., consumer choice). Thus, brand equity reflects a firm’s competitive position in the market (Keller, 1993; Yoganathan et al., 2015). High brand equity suggests that the firm emphasizes its competence in delivering quality products as perceived by customers (Ioannou et al. 2023) and places the highest priority on profit-making (Zhou et al., 2005). By leveraging market logic, high brand equity not only fosters consumer trust in product quality but also reinforces investor confidence in the firm’s capability to deliver superior products and weather crises (Fayez Ahmad et al. 2022).

CSR activities are the social requirement for sustainable economic development, implying that a firm attempts to perform certain social goods beyond its own financial interests (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001; Cheah et al., 2007). CSR activities often involve family-related issues, such as employee well-being and community development. That is to say, CSR emphasizes the firm’s contribution to the collective interests of the society (Godfrey, 2005). By using family logic, a high CSR performance yields a positive moral evaluation among stakeholders, subsequently accumulating moral capital for the firm (Godfrey, 2005; Shiu and Yang, 2017). Moral capital can serve as character evidence on behalf of the firm, maintaining stakeholder trust and protecting revenue streams against loss (Godfrey, 2005).

Social cognitive theory

Social cognitive theory suggests that both internal and external stimuli can influence an individual, thereby facilitating the acquisition or extinction of certain behaviors (Wood and Bandura, 1989). These stimuli include skills training, observed behaviors, customs and traditions, the environmental context, and internal/external cues to action. Recent studies have applied the social cognitive framework in the business field to explore workplace spirituality (Otaye-Ebede et al., 2020) and entrepreneurial orientation (Liu and Xi, 2022). According to this theory, cultural context influences an individual’s cognitive processes and trading behaviors through symbol systems, behavioral patterns, and reward/punishment mechanisms. Empirical cultural studies have indicated that the collectivism dimension of the culture influences individuals’ judgments and trading behaviors through socio-cognitive pathways.

As a context-dependent moderating factor, socio-cognition highlights the importance of cultural heterogeneity in risk management (Griffin et al., 2021). In China, socio-cognition rooted in Confucianism can moderate risk management and influence insurance mechanisms (Du, 2016). Specifically, Confucian principles, such as ren (benevolence), yi (righteousness), and li (rituals), underpin the societal expectations of firms and influence their risk management (Jin et al., 2023). Ren embodies compassion, empathy, and caring for others, encouraging the fair and humane redistribution of resources and supplementing government welfare systems through communal support. Yi involves moral integrity, justice, and doing what is ethically right, emphasizing sustainable development. Li refers to proper conduct, etiquette, and social norms that respect interpersonal communal relationships and is crucial for maintaining a harmonious society. Therefore, socio-cognition rooted in Confucianism can influence stakeholders’ judgments of firm strategies and responses to product-harm crises.

Thus, considering the two logics and socio-cognitive processes, this study explores how brand equity and CSR strategies impact financial value during Chinese product-harm crises. While this study tests whether product-harm crises have negative effects on financial value (H1a) and whether these effects are more negative for crises with more serious hazards (H1b), the focus of this study is the insurance-like effects of brand equity (H2) and CSR on the financial value of affected firms during product-harm crises (H3), and which insurance-like effect is more effective for affected firms in a collectivist society (H4). Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework.

Hypothesis development

Crisis severity and negative judgments

Significant research efforts have investigated the financial impacts of product-harm crises, but the results are varied or even contradictory. The findings are mainly divided into two categories: the financial impact of product-harm crises is significant or insignificant. These findings are mixed because of the different industries or the different crisis severities being studied (Chen et al., 2009; Thirumalai and Sinha, 2011). In this study, to obtain unified and objective conclusions, product-harm crises are divided by crisis severity.

In terms of crisis severity, previous research has classified the food, consumer products, and medical equipment industries into three classes. The severity ranges from low to high (i.e., from minimal to serious adverse health consequences) (Thirumalai and Sinha, 2011; Kini et al., 2017). According to social cognitive theory, product hazards with high severity violate social norms more severely than those with low severity, resulting in more negative judgment and stronger negative stock market reactions.

Specifically, severe product hazards carry more negative information to consumers (i.e., public health risks), leading to consumers’ more negative judgment (Dedman and Lin, 2002; Mafael et al., 2022). In this case, consumers are more likely to boycott these products. Meanwhile, investors of companies involved in the product-harm crises are more likely to make illegitimacy judgments and sell off stocks to protect their profits or reduce their losses (Rogers, 1975; Shafu Zhang et al., 2021). Investors may dump as many of their stocks as possible after considering their profits and other interests, resulting in a sharp decline in stock price (Ni et al., 2016). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

H1a. Product-harm crises have significantly negative effects on affected firms’ financial value.

H1b. The negative effects of product-harm crises increase as the crisis severity increases.

Market logic and negative judgments

As mentioned earlier, product-harm crises can result in negative judgments and subsequent financial penalties, regardless of market or family logic and self- or other- interests. By leveraging market logic, Cleeren et al. (2008) have shown that consumer loyalty and familiarity could shorten the time it took to repurchase the brand during the Australian peanut butter crisis, suggesting that high brand equity could mitigate the negative effect of the crisis. Hsu and Lawrence (2016) have found that brand equity can mitigate financial penalties during U.S. product recalls, since brand equity is the outcome of market competition and can therefore influence stakeholders’ attribution (Rovedder de Oliveira et al., 2018). The underlying rationale is that high brand equity generates greater consumer trust (F. Ahmad and Guzman, 2021) and signals a consumer perception of high product quality and selective attention (Datta et al., 2017). Thus, stakeholders are less likely to attribute crisis responsibility to a firm with high brand equity. In contrast, a relatively unknown brand facing a crisis is more likely to receive more complaints and bear more crisis responsibility (Laczniak et al., 2001).

Furthermore, Rovedder de Oliveira et al. (2018) have studied emerging markets in Latin America, demonstrating that brand equity can reduce financial risk and create shareholder value in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. However, cultural literature has suggested that stakeholders place less weight on brand equity in Eastern countries than in Western countries (Zhang et al., 2014). Therefore, an emerging market in a collectivist society would be a potential context to predict whether brand equity can mitigate the negative effects of product-harm crises.

Because firms with high brand equity are more likely to trigger positive associations in stakeholders’ minds than those with low brand equity (Rego et al., 2009), the former are less likely to face negative judgments and financial penalties during a crisis. Specifically, consumers perceive high brand equity products as having high quality, and they attribute the crisis to external causes. Further, investors can generally predict a sustainable cash flow for such affected firms. In contrast, consumers perceive low brand equity products as being of poor quality, and they tend to attribute such crises to internal causes, thus increasing the vulnerability of the company’s cash flow. Therefore, this study suggests that brand equity can provide an insurance-like effect for affected firms in this emerging market. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2. High brand equity can mitigate the negative effects of product-harm crises on affected firms’ financial value.

Family logic and negative judgments

This study applies family logic and considers that CSR can influence stakeholders’ negative judgments and investors’ financial penalties in the case of product-harm crises. CSR is defined as activities that are some social good beyond the financial interests of the firm and that go further than mere compliance with legal requirements (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001; Cheah et al., 2007). The concept of CSR implies that firms are responsible for their practices and extends from the concerns of shareholders’ profitability to diverse issues affecting employees, their families, communities, and society (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001; Bitektine and Song, 2021).

Recent studies have explored the relationship between CSR and firm risk. Their results have shown that CSR can have an insurance-like effect during a negative event (Jo and Na, 2012; Shiu and Yang, 2017). Building on the existing literature, some studies have revealed that CSR can also have an insurance-like effect on shareholder value during product-harm crises (Kong et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2025). Based on family logic, firms with a CSR strategy broadcast that they are concerned with the interests of consumers, other stakeholders, communities, and society as a whole. When a firm with a solid CSR strategy experiences a product-harm crisis, investors believe that they did not intend for it to occur and may forgive them easily. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H3. A high level of CSR can mitigate the negative effect of product-harm crises on affected firms’ financial value.

Socio-cognition and negative judgments

Although both brand equity and CSR provide insurance-like protection for affected firms, their underlying insurance mechanisms differ fundamentally (Garriga and Melé, 2004; Rego et al., 2009). Brand equity uses market logic to satisfy consumer demands and maintain consumer trust. In contrast, CSR leverages family logic to encompass the product market, as well as the workplace, the stakeholders, and the social and natural environments. Cultural studies have suggested that cultural socio-cognition can influence risk management and insurance mechanisms (Yang et al., 2022; Kaustia et al., 2023). Specifically, socio-cognition varies in its influence as a moderating factor across cultural contexts. For instance, consumers in collectivist cultures exhibit stronger family orientation, lower preference for well-known brands (Sun et al., 2004), greater participation in green initiatives (Ogiemwonyi and Jan, 2023), and more morally-driven investment choices (El Ghoul et al., 2019).

These arguments align with Confucian values (Parsa et al., 2021), which emphasize family commitment, collective welfare, and social harmony. In this culture, the family constitutes the fundamental unit of social and economic life; therefore, individuals in this context are accustomed to prioritizing family commitments. Moreover, Confucian ren emphasizes treating others with benevolence, which complements the social welfare system. Confucian yi highlights the importance of sustainable development. Confucian li regulates individual behaviors to mitigate conflicts and maintain social harmony. Thus, such socio-cognition influences how consumers and investors perceive brand equity and CSR, and how they respond to product-harm crises.

While brand equity aligns with market competition and profit achievement, CSR emphasizes broader societal welfare, which resonates deeply with Confucian principles. CSR reflects a moral philosophy whereby business activities transcend economics to embody ren (moral accountability), yi (sustainable practice), and li (harmonious stakeholder relations). This congruence explains why stakeholders in collectivist societies favor CSR (Alden et al., 1999; Moon and Shen, 2010; Kolk and Tsang, 2017), while accounting for the relative marginality of brand equity (Sha Zhang et al., 2014). Theoretical and empirical evidence have suggested that CSR provides a stronger insurance-like effect on financial value than brand equity during Chinese product-harm crises. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4. The insurance-like effect of CSR on financial value is stronger than that of brand equity during Chinese product-harm crises.

Methodology

Sample structure

We identify product-harm crises through systematic searches of official regulatory announcements (China Food and Drug Administration [CFDA], State Administration for Market Regulation [SAMR]) and verify them through news reports. More precisely, we utilize specific keywords, including “unqualified products,” “substandard products,” and “product quality issues”, to search regulatory databases (CFDA, SAMR) and news sources. Only incidents formally acknowledged by regulatory agencies or widely reported by credible media sources are retained and evaluated. Each case is cross-verified across at least two independent sources (e.g., regulatory records + major news outlets) to ensure reliability. Rumors or unverified claims are excluded. Minor incidents (e.g., those with no regulatory action or limited public impact) are omitted.

The sample period spans from the beginning of 2014 to the end of 2017, considering the limited reports of product-harm crises before 2014 and a more dynamic macro environment since 2018. Incorporated firms are A-share listed corporations in China and need to be based in China and traded on China’s mainland exchange. Their stock returns can be obtained from the CSMAR database.

Panel A of Table 1 displays the sample distribution by crisis severity. Crisis severity is divided into three levels: Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 events. Class 1 events are the least severe (e.g., packaging problems); Class 2 events are possible to induce temporary, medically reversible adverse health consequences or major financial losses (e.g., expired foods); and Class 3 events, which are the most severe, may result in adverse health consequences or death (e.g., drugs discovered to have carcinogenic substances or faulty automobile brakes) (Kini et al., 2017). Finally, Panel A includes 208 samples. Of these, Class 3 events account for 51.44%.

Panel B of Table 1 presents the one-level industry classification code (INC) industry distribution by crisis severity. In terms of industry distribution, the manufacturing sector has the most product-harm crises: 90 cases of Class 3 events, 57 cases of Class 1 events, and 19 cases of Class 2 events. The reason for this phenomenon is that food, beverages, and medicines all belong to the B2C manufacturing industry, which is more likely to experience cases that may cause potential or substantial damage to consumers. As a result, their product-harm events have a wider range of influence and dominate all industries.

Due to the wide impact of product-harm crises in the manufacturing sector, such crises are more likely to cause a loss of shareholder value, thus highlighting the need to elucidate the relevant insurance mechanisms. Panel C of Table 1 presents the details of the manufacturing industry and its sub-industry distribution by crisis severity. There exist nine two-level INC industries in the manufacturing sector. The food, beverage, and medicine industries are more prone to product-harm crises owing to the nature of the products and the strict associated regulations. Considering their daily use, defects in these products can directly affect consumer health and safety, spark widespread backlash and media attention, and escalate into large-scale crises.

Independent variables

According to the research design, the key independent variables in this study include severity, brand equity, and CSR. Severity is represented by three dummy variables: 1 for Class 1 events, for Class 2 events, and for Class 3 events in the product-harm samples based on event severity, and 0 for other firms.

Brand equity refers to consumer-based brand equity and is an added value by associating a product with a brand logo and/or name (Rego et al., 2009). Based on consumers’ perceptions of the brand, there exists one broad measurement system (Datta et al., 2017), i.e., the consumer-based system of Keller (1993). Currently, examples such as rankings of the most valuable brands are commonly used to measure consumer-based brand equity (Rovedder de Oliveira et al., 2018). In the Chinese context, the publicly available ranking is “China’s Most Valuable Brands,” which is accessed by World Brand Lab (www.worldbrandlab.com). Therefore, this study uses the “China’s 500 Most Valuable Brands” ranking to measure brand equity. Sampled firms on the list are considered to have high brand equity and are rated as 1, while all other firms are given a 0. This dummy variable of brand equity is used to determine whether the financial impact of product-harm crises differs for firms with high brand equity compared with other firms (Hsu and Lawrence, 2016).

CSR indicates socially responsible firms. This research adopts the CNI ESG 300 index, which includes 300 firms with good environment, society, and governance (ESG) performance in the A-share stock market, as the basis for identifying socially responsible firms. Thus, sampled firms in the index meeting the criteria for good CSR practices are set to the value of 1, and all other firms are given a 0. In doing so, this study could explore whether the CSR strategy can influence stakeholders’ illegitimacy judgments and subsequent financial risks (Cheah et al., 2007).

In addition, Table 2 shows the results of a univariate nonparametric test for various product-harm classes based on variables that could influence product-harm crises. On the basis of previous studies, these variables include Size (Chen et al., 2009), RDI (Zou et al., 2020), BL (Wiles et al., 2012), and BTM (Zou and Li, 2016). Size is measured as the natural logarithm of the firm’s total assets. RDI is measured as the research and development spending over the total assets. BL is the ratio of the sum of debt in current liabilities and the long-term debt to the total assets. BTM is calculated as the ratio of the book value to the market value. All variables are computed at the end of the previous year and obtained from the CSMAR database. Notably, the overall sample includes all product-harm events covered in this study; the manufacturing sample involves the product-harm events in all manufacturing industries.

For the overall sample, the results indicate that Size, BL, and BTM are significant at the 10%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively. For the manufacturing subsample, the results show that RDI and BL are significant at the 10% and 1% levels, respectively. Together, these results reveal that variables may differ significantly across product-harm classes.

Dependent variable

Event study methodology (ESM) is used to estimate the impact of product-harm crises on the affected firms’ financial value (Zhao et al., 2013). Using ESM, this study calculates the abnormal returns (ARs) of product-harm events, mirroring the financial effects of such events in one day. The value of ARs is the result of actual returns minus normal returns around the event publicity date. Furthermore, cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) mirror the cumulative effects of the firm’s product-harm event. The value of CARs is equal to the sum value of the ARs during the event windows. A negative CARs value indicates that the event is unfavorable and, thus, typically suggests a negative forecast of future profitability.

More details are as follows. The earliest publicized day of the product-harm crisis is termed as the event publicity date. Then, this study measures CARs over a few days surrounding the publicity date because many product-harm crises are initially exposed in-house prior to the publicity, and therefore, information can be leaked to the market before the event publicity date. Thus, this study calculates CARs considering the time before the event publicity date to account for any leaks. More precisely, the event windows include (−1, +1), (−1, +5), (−5, +1), (−10, +5), and (−10, +10), with day 0 indicating the event publicity date.

To predict expected daily returns, this study employs the market model (Eq. 1), estimated using daily returns over the period (−200, −11). Then, the study measures the abnormal return for firm i on day t (ARit) using Eq. (2).

where \({\hat{R}}_{{it}}\) is the expected daily return, RPit is the market risk premium factor, Rmt is the return of the CSMAR equally weighted index, α and β are estimated parameters, and Rit is the return for firm i on day t.

Interaction models

To test whether brand equity and CSR can mitigate the negative effects of product-harm crises on shareholder wealth across industries, this study puts brand equity, CSR, and an interaction term with crisis severity into Eqs. (3) and (4):

To further test the dominant insurance-like effect in Chinese product-harm crises, this study puts brand equity, CSR, and their interaction terms with crisis severity into Eq. (5) and examines their effects on shareholder wealth across industries:

Results

Effects of product-harm crises by crisis severity

Panel A in Table 3 shows the means and t-test results of CARs for five windows around the event publicity date. The specific event windows are mentioned above. CARs are the difference between a firm’s actual return and its expected return; this is calculated based on the market model over the estimation period (−200, −11). The label “Class 1 & 2” in Table 3 refers to the grouping of Class 1 and Class 2 crises. Panel B of Table 3 presents the Kruskal–Walli’s test results for CARs of different crisis severities. The Kruskal–Wallis test is used to evaluate the effect of the product-harm crisis severity on shareholder value.

The results show that the mean CARs of Class 3 events are significantly negative for almost all of the event windows, both for the overall sample and for the subsamples. The mean CARs of Class 3 events are all significant at the 5% level at least. However, the mean CARs of the Class 1 & 2 groups are not significant for the overall sample; moreover, the mean CARs of the Class 1 & 2 groups are positive and weakly significant for the manufacturing sector. These findings reveal that the effect of Class 3 events is negative and serious, whereas Class 1 & 2 group events fail to show statistically significant negative effects. Consequently, Table 3 provides partial support for H1a and strong support for H1b.

Interactions between brand equity, CSR, and crisis severity for the overall sample

Table 4 shows the estimated results of these models for the overall sample during the sample period. The dependent variable is CARs (−5, +1), and all variables are measured for the year before the date of event publicity. Size is treated as a control variable in Column (1). RDI is added in Column (2), and BL and BTM are added in Column (3).

In Table 4, the coefficients for Class 1 and 2 events are not significant, but the coefficients for Class 3 events are negative and significant. These results further support H1b. Moreover, the coefficients for the Class 3 × Brand equity variable are positively significant at the 10% level in Columns (1) and (2) (α = 0.0203* and 0.0202*), indicating that high brand equity can mitigate the negative effect of a product-harm crisis on shareholder value. Additionally, the coefficients for the Class 3 × CSR variable are positive and significant at the 1% level in all columns (α = 0.0301***, 0.0325***, and 0.0329**), which confirms that firms with higher CSR suffer fewer losses in shareholder value. Thus, the results in Table 4 support H2 and H3.

Interactions between brand equity, CSR, and crisis severity for manufacturers

In addition, to check whether the above results are robust, this study further tests the insurance-like effects of brand equity and CSR for the manufacturing sector. Similarly, this study inserts brand equity/CSR and an interaction term with crisis severity into the models. Table 5 shows the estimated results of these models for all manufacturing industries during the sample period. All variables are measured as described above. Marginal effects are reported in Table 5.

Similar to Tables 4 and 5 show that the coefficients for Class 1 events are not significant but the coefficients for Class 3 events are negative and significant. Again, such results empirically support H1b. Moreover, the coefficients on the Class 3 × Brand equity variable are positively significant at the 10% level in Columns (1) and (2) (α = 0.0210* and 0.0240*), which reveals that high brand equity can mitigate the negative impact of product-harm crises on shareholder value. The coefficients on the Class3 × CSR variable are positively significant at the 1% level in all columns (α = 0.0339***, 0.0368***, and 0.0368***), suggesting that firms with a higher level of CSR suffer less loss in shareholder value. Again, the results in Table 5 support H2 and H3.

Three-way interactions among brand equity, CSR, and crisis severity

Table 6 shows the estimated results for the overall sample and all manufacturing industries during the sample period. All variables are measured as previously. Size is treated as a control variable in Column (1), and RDI is added in Column (2). Marginal effects are also reported in Table 6.

Consistent with Tables 4 and 5, the results in Table 6 show that the coefficients for the Class 3 × CSR variable are significant in Columns (1) and (2) (α = 0.0422***, 0.0452***; and 0.0427***, 0.0455***), but the coefficients for the Class 3 × Brand equity variable are not significant (α = 0.0144, 0.0141; and 0.0139, 0.0163), neither for the overall sample nor for the manufacturing industries. These results demonstrate that the insurance-like effect of CSR prevails over that of brand equity when both CSR and brand equity are incorporated. Specifically, the insurance-like effect of CSR holds at a 1% level, but that of brand equity is insignificant, implying that CSR matters more than brand equity in the context of Chinese product-harm crises.

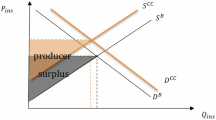

These results are illustrated in Fig. 2. This figure reveals the moderating effects of brand equity and CSR across four distinct scenarios: (1) Low Brand Equity, Low CSR; (2) High Brand Equity, Low CSR; (3) Low Brand Equity, High CSR; and (4) High Brand Equity, High CSR. Starting from the baseline scenario (Low Brand Equity, Low CSR), increasing either CSR or brand equity independently reduces the financial losses. These findings provide further support for H2 and H3. Notably, the marginal benefit analysis demonstrates that CSR provides superior financial protection compared with equivalent brand equity, i.e., CSR exerts a stronger insurance-like effect. Furthermore, at high levels of CSR (brand equity), further increasing brand equity (CSR) diminishes (increases) the insurance-like protection for the affected firm. These analyses suggest that increasing CSR is more effective than increasing brand equity in protecting financial value and promoting CARs. Therefore, Table 6 and Fig. 2 provide support for H4, while the non-linear effects identified through scenario analysis provide important boundary conditions for understanding these insurance mechanisms.

Moreover, this study measures the average CARs of high brand equity firms and those of high CSR corporations, i.e., firms appearing on the MVB 500 and ESG 300 lists, respectively, and compares the differences between them. Results show that firms with a high CSR have higher stock prices and receive less shock from product-harm crises. Figure 3, therefore, further supports H4.

Discussion

Risk management research has predominantly examined insurance mechanisms from a firm-level perspective. However, social cognition, which varies across cultural contexts, can influence these insurance mechanisms. This study adopts a socio-cognitive lens to explore how insurance mechanisms function during Chinese product-harm crises. Our findings reveal that product-harm crises exert an increasingly negative effect on affected firms’ financial value as the crisis severity escalates (H1b). Notably, both brand equity and CSR have insurance-like effects on financial value (H2 and H3), with CSR demonstrating a greater insurance-like effect than brand equity (H4).

The mechanism governing CSR’s insurance-like effect is clarified as follows. That is, when a firm announces a product-harm crisis, family logic is activated, and CSR leverages this logic to influence stakeholder perceptions and responses. Moreover, socio-cognitive norms rooted in Confucian culture moderate risk management outcomes. To be specific, when the affected firm demonstrates high CSR engagement, stakeholders perceive its actions through the lens of Confucian values. They consider that such a firm treats others with moral integrity (ren), i.e., pursuing profits through ethical means (yi), and engaging in sustainable business practices, thereby aligning CSR with deeply held cultural values. This cultural interpretation offers a powerful cognitive mechanism: stakeholders perceive that this firm has genuine moral character and develop strong social identification, likely trusting the firm and attributing the crisis to unfortunate accidents rather than intentional wrongdoing.

Additionally, the results reveal an interesting pattern, i.e., increasing CSR engagement is more effective in promoting CARs when there is a relatively low brand equity (see Fig. 2). When there is a high level of brand equity, providing high CSR engagement does not make a significant marginal contribution to CARs. This may imply that the relationship between CSR and brand equity in mitigating financial risks is substitutive (Caloghirou et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2018). There may be diminishing marginal returns when adopting multiple risk-mitigation strategies.

Theoretical implications

This study yields some important theoretical implications. First, we challenge the presumed universality of socio-cognitive processes in risk management by demonstrating systematic variations across cultural contexts. We provide novel evidence showing how socio-cognition rooted in collectivism influences stakeholder perceptions and behaviors during product-harm crises. These findings substantially expand the socio-cognition framework’s application in risk management research, while calling for greater attention on cultural contexts in theoretical development.

Second, we empirically demonstrate the validity of insurance-like protection of brand equity and CSR in the collectivist context. Our finding reveals that in the Chinese context, either brand equity or CSR can independently provide insurance-like protection for affected firms, and the corresponding strategy can mitigate their financial risks during product-harm crises. By this, we extend the boundaries of risk management research beyond the individualistic contexts that have been the predominant focus of prior studies.

Third, we empirically reveal the cultural specificity of insurance mechanisms. Our analysis shows that in collectivist contexts like China, CSR exhibits a stronger insurance-like effect than brand equity during product-harm crises. This finding underscores the importance of cultural heterogeneity in risk management, thereby validating Oh et al. (2025) argument that CSR’s risk-mitigation effects are contingent on contextual moderators. Further, for such crises, if an effective strategy is consistent with the culture’s core values, then another risk-mitigation strategy may not be necessary. Thus, to mitigate risks, firms do not necessarily need to adopt as many risk-mitigation strategies as possible.

Practical implications

This study offers several actionable guidance for risk management. In collectivist societies, firms with high CSR engagement exhibit greater resilience to product-harm crises than those relying primarily on high brand equity. This finding emphasizes the role of socio-cognition in insurance mechanisms, reinforcing the need for firms to align their strategies with cultural values. By developing a nuanced understanding of socio-cognitive influences, managers can make more informed decisions to facilitate proactive risk prevention and enhance risk mitigation effectiveness across cultural contexts.

Notably, while CSR proves more effective insurance-like protection, brand equity maintains strategic value for market expansion and competitive positioning. Consequently, managers should strategically calibrate their portfolio by balancing self-interest initiatives (e.g., brand equity) with normative commitments (e.g., CSR), thereby enhancing their long-term resilience across cultural contexts and temporal phases.

Conclusion and future research

In a nutshell, this study investigates whether brand equity and/or CSR can provide an insurance-like protection when the firm experiences product-harm crises. Specifically, we examine whether brand equity and CSR can mitigate financial risks from product-harm crises. The findings demonstrate that firms can prepare themselves with high brand equity or high CSR engagement to withstand the financial impact of product-harm crises. Notably, in collectivist societies like China, a high level of CSR is more effective in reducing financial risks arising from a severe product-harm crisis. By providing empirical evidence, this study offers actionable insights for firms operating in Asian markets, enabling them to adopt risk management strategies that align with regional cultural values and stakeholder expectations.

This study focuses on one type of corporate scandal, i.e., product-harm crises. Future research could extend the investigation to other types of crises. For instance, it could explore the relative effects of CSR and brand equity in other crises, such as environmental disasters (e.g., oil spills), climate governance failures (e.g., carbon emission controversies), or socio-ethical misconduct (e.g., labor rights violations). Additionally, the role of socio-cognitive processes underlying stakeholder judgments merits further investigation in culturally hybrid settings, particularly in Global South economies undergoing rapid individualization (e.g., Vietnam). Thus, future research could investigate how cultural hybridization moderates stakeholder reactions to firm strategies and crises.

Data availability

The datasets of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad F, Guzman F (2021) Brand equity, online reviews, and message trust: the moderating role of persuasion knowledge. J Prod Brand Manag 30(4):549–564

Ahmad F, Guzmán F, Kidwell B (2022) Effective messaging strategies to increase brand love for sociopolitical activist brands. J Bus Res 151:609–622

Alden D, Steenkamp J-B, Batra R (1999) Brand positioning through advertising in Asia, North America, and Europe: the role of global consumer culture. J Mark 63(1):75–87

Au K, Han S, Chung H-M (2018) The impact of sociocultural context on strategic renewal: a twenty-six nation analysis of family firms. Cross Cult Strat Manag 25(4):604–627

Bitektine A, Song F (2021) On the role of institutional logics in legitimacy evaluations: the effects of pricing and CSR signals on organizational legitimacy. J Manag 49(3):1070–1105

Caloghirou Y, Kastelli I, Tsakanikas A (2004) Internal capabilities and external knowledge sources: complements or substitutes for innovative performance? Technovation 24(1):29–39

Chakraborty T, Mukherjee A, Chauhan SS (2023) Should a powerful manufacturer collaborate with a risky supplier? Pre-Recall Vs. post-recall strategies in product harm crisis management. Comput Industrial Eng 177

Cheah ET, Chan WL, Chieng CLL (2007) The corporate social responsibility of pharmaceutical product recalls: an empirical examination of US and UK markets. J Bus Ethics 76(4):427–449

Chen Y, Ganesan S, Liu Y (2009) Does a firm’s product-recall strategy affect its financial value? An examination of strategic alternatives during product-harm crises. J Mark 73(6):214–226

Cleeren K (2015) Using advertising and price to mitigate losses in a product-harm crisis. Bus Horiz 58(2):157–162

Cleeren K, Dekimpe MG, Helsen K (2008) Weathering product-harm crises. J Acad Mark Sci 36(2):262–270

Cleeren K, Dekimpe MG, van Heerde HJ (2017) Marketing research on product-harm crises: a review, managerial implications, and an agenda for future research. J Acad Mark Sci 45(5):593–615

Datta H, Ailawadi KL, van Heerde HJ (2017) How well does consumer-based brand equity align with sales-based brand equity and marketing-mix response? J Mark 81(3):1–20

Dedman E, Lin SWJ (2002) Shareholder wealth effects of CEO departures: evidence from the UK. J Corp Financ 8(1):81–104

Du X (2016) Does confucianism reduce board gender diversity? Firm-level evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 136(2):399–436

El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Kwok CCY, Zheng Y (2019) Collectivism and the costs of high leverage. J Bank Financ 106:227–245

Garriga E, Melé D (2004) Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J Bus Ethics 53(1):51–71

Glaser VL, Fast NJ, Harmon DJ, Green SE (2017) Institutional frame switching: How institutional logics shape individual action. Gehman J, Lounsbury M, Greenwood R, (eds) How Institutions Matter!, vol. 48A, pp 35–69

Godfrey PC (2005) The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: a risk management perspective. Acad Manag Rev 30(4):777–798. Review

Griffin D, Guedhami O, Li K, Lu G (2021) National culture and the value implications of corporate environmental and social performance. J Corp Financ 71:102123

Hsu L, Lawrence B (2016) The role of social media and brand equity during a product recall crisis: a shareholder value perspective. Int J Res Mark 33(1):59–76

Ioannou I, Kassinis G, Papagiannakis G (2023) The impact of perceived greenwashing on customer satisfaction and the contingent role of capability reputation. J Bus Ethics 185(2):333–347

Jin Z, Li Y, Liang S (2023) Confucian culture and executive compensation: evidence from China. Corp Gov Int Rev 31(1):33–54

Jo H, Na H (2012) Does CSR reduce firm risk? Evidence from controversial industry sectors. J Bus Ethics 110(4):441–456

Kang C, Germann F, Grewal R (2016) Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. J Mark 80(2):59–79

Kaustia M, Conlin A, Luotonen N (2023) What drives stock market participation? The role of institutional, traditional, and behavioral factors. J Bank Financ 148:106743

Keller KL (1993) Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J Mark 57(1):1–22

Kim J, Park T (2020) How corporate social responsibility (CSR) saves a company: The role of gratitude in buffering vindictive consumer behavior from product failures. J Bus Res 117461–117472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.024

Kim Y, Woo CW (2019) The buffering effects of CSR reputation in times of product-harm crisis. Corp Commun 24(1):21–43

Kini O, Shenoy J, Subramaniam V (2017) Impact of financial leverage on the incidence and severity of product failures: Evidence from product recalls. Rev Financ Stud 30(5):1790–1829

Kolk A, Tsang S (2017) Co-evolution in relation to small cars and sustainability in China: interactions between central and local governments, and with business. Bus Soc 56(4):576–616

Kong D, Shi L, Yang Z (2019) Product recalls, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: evidence from the Chinese food industry. Food Policy 83:60–69

Laczniak RN, DeCarlo TE, Ramaswami SN (2001) Consumers’ responses to negative word-of-mouth communication: an attributions theory perspective. J Consum Psychol 11(1):57–73

Liu AZ, Liu AX, Wang R, Xu SX (2020) Too much of a good thing? The boomerang effect of firms’ investments on corporate social responsibility during product recalls. J Manag Stud 57(8):1437–1472

Liu Y, Xi M (2022) Linking CEO entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the perspective of middle managers’ cognition. Entrepreneur Theory Pract 46(6):1756–1781

Lu H, Oh W-Y, Kleffner A, Chang YK (2021) How do investors value corporate social responsibility? Market valuation and the firm specific contexts. J Bus Res 125:14–25

Mafael A, Raithel S, Hock SJ (2022) Managing customer satisfaction after a product recall: the joint role of remedy, brand equity, and severity. J Acad Mark Sci 50(1):174–194

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manag Rev 26(1):117–127

Moon J, Shen X (2010) CSR in China research: salience, focus and nature. J Bus Ethics 94(4):613–629

Ngoye B, Sierra V, Ysa T (2019) Different shades of gray: a priming experimental study on how institutional logics influence organizational actor judgment. Public Adm Rev 79(2):256–266

Ni J, Flynn BB, Jacobs FR (2016) The effect of a toy industry product recall announcement on shareholder wealth. Int J Prod Res 54(18):5404–5415

Ni JZ, Flynn BB, Jacobs FR (2014) Impact of product recall announcements on retailers’ financial value. Int J Prod Econ 153:309–322

Noack D, Miller DR, Smith D (2019) Let me make it up to you: Understanding the mitigative ability of corporate social responsibility following product recalls. J Bus Ethics 157(2):431–446

Ogiemwonyi O, Jan MT (2023) The influence of collectivism on consumer responses to green behavior. Bus Strat Dev 6(4):542–556

Oh W-Y, Chang YK, Kim T-Y (2018) Complementary or substitutive effects? Corporate governance mechanisms and corporate social responsibility. J Manag 44(7):2716–2739

Oh W-Y, Zeng R, Bu M (2025) Buffering or backfiring? A meta-analysis of the effects of corporate social (ir)responsibility on firm risk. Bus Soci 00076503251350044

Otaye-Ebede L, Shaffakat S, Foster S (2020) A multilevel model examining the relationships between workplace spirituality, ethical climate and outcomes: a social cognitive theory perspective. J Bus Ethics 166(3):611–626

Parsa S, Dai N, Belal A, Li T, Tang G (2021) Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: political, social and corporate influences. Account Bus Res 51(1):36–64

Rego LL, Billett MT, Morgan NA (2009) Consumer-based brand equity and firm risk. J Mark 73(6):47–60

Rogers RW (1975) A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol 91(1):93–114

Rovedder de Oliveira MO, Stefanan AA, Lobler ML (2018) Brand equity, risk and return in latin America. J Prod Brand Manag 27(5):557–572

Sharpe S, Hanson N (2021) Sales response to corporate social irresponsibility and the mitigating role of advertising. Manag Decis 59(10):2456–2472

Shea CT, Hawn OV (2019) Microfoundations of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility. Acad Manag J 62(5):1609–1642

Shiu Y-M, Yang S-L (2017) Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance-like effects? Strat Manag J 38(2):455–470

Sun T, Horn M, Merritt D (2004) Values and lifestyles of individualists and collectivists: a study on Chinese, Japanese, British and US consumers. J Consum Mark 21(5):318–331

Tan G, Cheong CS, Zurbruegg R (2019) National culture and individual trading behavior. J Bank Financ 106:357–370

Thirumalai S, Sinha KK (2011) Product recalls in the medical device industry: an empirical exploration of the sources and financial consequences. Manag Sci 57(2):376–392

Utz S (2019) Corporate scandals and the reliability of ESG assessments: evidence from an international sample. Rev Manag Sci 13(2):483–511

Wang L, Juslin H (2009) The impact of Chinese culture on corporate social responsibility: the harmony approach. J Bus Ethics 88(S3):433–451

Wiles MA, Morgan NA, Rego LL (2012) The effect of brand acquisition and disposal on stock returns. J Mark 76(1):38–58

Wood R, Bandura A (1989) Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Acad Manag Rev 14(3):361–384

Yang Y, Li S, Wu H (2023) Debt enforcement, financial leverage, and product failures: evidence from China and the United States. J Financial Res 46(3):763–789

Yang Y, Li S, Yang J (2025) Make it up to you or not: understanding the role of substantive versus symbolic CSR activities following product-harm crises. Eur J Financ 31(2):99–121

Yang Z, Freling T, Sun S, Richardson-Greenfield P (2022) When do product crises hurt business? A meta-analytic investigation of negative publicity on consumer responses. J Bus Res 150:102–120

Yoganathan D, Jebarajakirthy C, Thaichon P (2015) The influence of relationship marketing orientation on brand equity in banks. J Retail Consum Serv 26:14–22

Yue S, Bajuri NHB, Khatib SFA, Alshareef MN (2025) Ownership with a green twist: the role of top managers in driving environmental innovation. China Finance Rev Int

Zhang S, van Doorn J, Leeflang PSH (2014) Does the importance of value, brand and relationship equity for customer loyalty differ between eastern and western cultures? Int Bus Rev 23(1):284–292

Zhang S, Jiang L, Magnan M, Su LN (2021) Dealing with ethical dilemmas: a look at financial reporting by firms facing product harm crises. J Bus Ethics 170(3):497–518

Zhao X, Li Y, Flynn BB (2013) The financial impact of product recall announcements in China. Int J Prod Econ 142(1):115–123

Zhou KZ, Gao GY, Yang ZL, Zhou N (2005) Developing strategic orientation in China: antecedents and consequences of market and innovation orientations. J Bus Res 58(8):1049–1058

Zou P, Li G (2016) How emerging market investors’ value competitors’ customer equity: brand crisis spillover in China. J Bus Res 69(9):3765–3771

Zou P, Wang Q, Xie J, Zhou C (2020) Does doing good lead to doing better in emerging markets? Stock market responses to the SRI index announcements in Brazil, China, and South Africa. J Acad Mark Sci 48(5):966–986

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Yan’an University Doctoral Research Startup Project (Grant 205070040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author, Yaopan Yang, conceived the study, wrote the article’s draft, and was responsible for the design and development of the data analysis. The second author, Songsong Li, was responsible for the supervision and support with other sources. The third author, Daquan Gao, contributed to revision. The fourth author, Jin Wang, contributed to revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Li, S., Gao, D. et al. Hold up an umbrella on rainy days: the insurance-like effects of brand equity and corporate social responsibility during Chinese product-harm crises. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1733 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06020-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06020-2