Abstract

While research on land use efficiency (LUE) - defined as the added value of secondary and tertiary industries per unit of urban land - has advanced considerably, systematic understanding of its temporal dynamics during urban land maturation and its growth potential remains limited. This study develops a novel analytical framework for urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement (ULMEE), conceptualizing it as a dynamic process of functional transition from singular to multiplex configurations with concomitant LUE improvements over time. Using multi-source data fusion and LitPop method to identify the spatiotemporal patterns in pixel-scale LUE among Chinese coastal cities, this study reveals that: the average LUE of urban land at the ages of 5, 15, and 25 years is 323 million, 695 million, and 922 million yuan/km2, respectively, validating the ULMEE process. Because as much as 69% of urban land is under 15 years old, there remains plenty of potential for ULMEE. This study applies the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) method to reveal that, except for scenario SSP3 (regional rivalry pathway in SSPs), cities of all scales will rely on ULMEE to meet the demands of a 5% economic growth rate before 2035. However, after 2040, cities of all scales will need to add new urban land to meet the demands of economic growth. This study provides a theoretical foundation for restricting the scale of newly added urban land in China’s coastal cities and selecting potential pathways for ULMEE. These findings provide a theoretical basis for sustainable urban expansion strategies with global implications for developing economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization is an inevitable trend as human society evolves. The global urbanization rate is unprecedented, at a level four times greater than previously estimated (Meyfroidt et al., 2022; Winkler et al., 2021; Liu et al. 2020). Urbanization not only supports economic development, but also causes environmental and social challenges, including climate change such as urban heat island effect (Zhou et al., 2004), soil erosion by water (Borrelli et al., 2020), deteriorating air quality and human health (Hong et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2024), and infrastructure inequality (Pandey et al., 2022). Due to the rapid advancement of urbanization and the increasing scarcity of land resources, available land in plains and low-altitude areas has gradually been occupied by urban construction, forcing agriculture, industry and residential activities to move to mountainous highlands and marginal farmland areas (Bren d'Amour et al., (2017); Chen et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). With the limited availability of land resources, related farmland protection policies, and urban sustainable development, an inefficient and extensive land use development pattern is no longer viable. Therefore, under the premise of ensuring the livability of the city, rationally increasing the level of intensive utilization and the orderly development of land resources are essential to resolving the “human–land conflict” and ensuring high-quality urban economic and regional coordinated development. As a direct consequence, a fundamental tension emerges between urban economic growth and sustainable development: while cities must expand to accommodate economic activities, unconstrained spatial expansion leads to irreversible ecological damage and ultimately undermines long-term economic viability. In this context, enhancing land use efficiency provides a fundamental pathway to reduce unnecessary spatial expansion and its associated environmental pressures.

Improving land use efficiency is an important solution to balance urban economic growth and sustainable use of land resources. Considering the economic benefits of urban land, LUE is defined as the economic output per unit of urban land area (He et al., 2020; Li et al., 2014; Luo and Wu, 2003; Wu et al., 2017; Yang and Luan, 2024). The Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China emphasize the comprehensive improvement in resource utilization efficiency. Therefore, it is essential to conduct research related to LUE. Current, LUE research focuses on measurement methodologies, research scales, and driving factors. Employing mainly quantitative methods, such as data envelopment analysis (Chen et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019) and stochastic frontier analysis (Wang et al., 2021). The spatial scales are dominated by macro scales, such as countries, urban agglomeration, and developed-region cities. The driving factors include economic development level (Chen et al., 2016), population density (Xue et al., 2022), industrial structure (Liu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023), industrial agglomeration (Zhang et al., 2022), spatial structure (Liao et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2022), regional integration (Zhao et al., 2021), and transportation accessibility (Wu et al., 2017).

Existing studies rely mostly on statistical data to measure LUE, presenting several limitations. The first is the measurement of urban land area: The conversion of non-urban land to urban land, as an important feature of the change in land use patterns, is a byproduct of the demand for urban land during urbanization and economic development. However, in the process of computing LUE, the built-up area in the statistical data is generally recorded as urban land area, resulting in a discrepancy between this value and the actual urban land area. Second, the spatial heterogeneity of LUE within cities has not been adequately considered: Socioeconomic statistical data, typically available as text at various levels of administrative divisions, are suitable for macro-analysis and the overall evaluation of cities (S. Liu et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022), but make it difficult to investigate the spatial heterogeneity of LUE within cities or at a fine scale. Third, there is a lack of focus on the urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement (ULMEE) process: Existing research focuses on the spatiotemporal evolution of LUE and the identification of influencing factors, whereas LUE characterization in the ULMEE process is relatively weak. Fourth, while LUE is a direct representation of the economic output capability of urban land, its impact on urban economic growth has not been fully explored in the literature.

China’s coastal cities, accounting for over 20% of the country’s population and 30% of its economic output, have a well-developed industrial structure and strong scientific and technological innovation capabilities, giving them substantial economic and strategic advantages. These cities have the highest rate of urban land expansion in the country (Liu et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015), with a high level of urbanization, extensive land redevelopment (Cao et al., 2023; Huang et al. 2023), and significantly higher economic exposure than inland cities (Chan et al., 2021). China is currently undergoing substantial land use reform (Han et al., 2023). Coastal cities, as the core areas of China’s economic development, face more stringent land resource limitations. Therefore, in response to the abovementioned limitations of LUE studies and given the representativeness and uniqueness of China’s coastal cities, the main objectives of this study are as follows: (i) to use various land use data and high-definition remote sensing images to measure the urban land area, and gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of urban land in China’s coastal cities; (ii) to propose a LitPop method for measuring LUE that integrates nighttime light and statistical data, and investigate the spatial pattern of LUE at the micro-scale and with comprehensive spatial information; (iii) based on the process of increasing the total economic output of urban land of different ages (the difference between the urban land generation year (time of conversion from non-urban land to urban land) and 2020) and enhancing the LUE of land at different ages, to clarify the specific ULMEE process and reveal the characteristics of LUE differences in coastal cities and of different urban scales; and (iv) from the perspective of different urban scales, using shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs), to predict future LUE at different ages and determine whether relying on the ULMEE process can meet the demands of a 5% urban economic growth rate. This method overcomes the limitations of administrative divisions and contributes to the dynamic supervision and intensive utilization of urban land. Simultaneously, based on the ULMEE process to determine whether it satisfies economic growth demands, this study helps clarify the imbalanced economic development of China’s coastal cities and contributes to decision-making support by revealing strategies to enhance urban economic development.

Materials and methodology

Study area

China’s coastal region comprises 51 cities (excluding Hainan Province), including 4 super cities, 4 megacities, 3 Type I large cities, 19 Type II large cities, 18 medium-sized cities, and 3 Type I small cities (Fig. 1). As the core engine of China’s economic development, coastal cities concentrate the nation’s primary economic output, population resources, and high-tech industries, while leading urbanization with their unique geographical advantages. Compared with other cities, coastal urban expansion demonstrates distinct characteristics: the outward-oriented economy drives more globalized and market-oriented spatial expansion with diversified land use demands; constrained by coastal geography, these areas face more rigid land resource limitations, often resorting to special development models like large-scale land reclamation. However, rapid urbanization has brought multiple challenges including population over-concentration, land resource shortages, and ecological fragility, particularly prominent environmental risks like sea-level rise and coastal erosion. Concurrently, the intertwining issues of regional development imbalance and “urban diseases” make these areas crucial for researching land use efficiency improvement, economic potential realization, and sustainable development optimization.

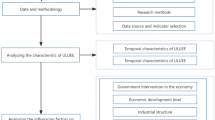

Technology framework

The technical framework is detailed in Fig. 2, with the specific process consisting of four key components: (A) deriving the spatiotemporal patterns of LUE in China’s coastal cities through multi-source data fusion and the LitPop method; (B) investigating the urban land maturation and efficiency improvement process by incorporating the “age” concept; (C) assessing whether urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement can support future economic growth requirements based on SSPs scenarios; and (D) examining the underlying mechanisms of urban land maturation and efficiency improvement through POI data analysis using kernel density estimation.

Data

The primary data utilized in this study includes the following: The land use data for China can be found at https://www.resdc.cn/DOI/DOI.aspx?DOIID=54. The nighttime lighting dataset (DMSP/OLS and NPP/VIIRS) can be found at https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/. China City Statistical Yearbook can be found at http://www.stats.gov.cn/. To account for price changes affecting real GDP growth, this study selected 1995 as the base year and used officially released secondary and tertiary GDP indices to deflate nominal GDP from 2000 to 2020, thereby eliminating price factor interference and obtaining the real GDP of secondary and tertiary industries for each city. A gridded dataset comprising value-added of primary, secondary and tertiary industries in China under shared socioeconomic pathways from 2020–2100 can be found at https://doi.org/10.4121/14113706.v2 (Jing et al., 2022). Point of interest data can be found at https://www.amap.com/. All data are included in the manuscript and/or SI, Table S1.

Methodology

Calculation of the economic elasticity coefficient (EEC)

To assess the balance of economic development and urban land expansion in China’s coastal cities, as well as their degree of synergy, this study employs the economic elasticity coefficient (EEC) to examine the relative changes in economic development and urban land expansion at various urban scales (Huang et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017). The analysis of the EEC contains six study phases: 1995–2000, 2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, 2015–2020, and 1995–2020. The computation formula is as follows:

In the formula, \({\rm{EEC}}\) development and urban land expansion reflect the relative speed of economic growth and urban land expansion, respectively; \({{GDP}}_{a}\), \({{GDP}}_{b}\) are the sums of the GDP of the secondary and tertiary sectors of different urban scales in the base and target years, respectively; \({{UL}}_{a}\), \({{UL}}_{b}\) are the urban land area in the base and target years for different urban scales, respectively; and \(n\) is the study period. The degree of synergy is divided into four categories based on the EEC: economic or urban land contraction (EEC < 0), urban land expansion (0 ≤ EEC < 1), fundamental economic–urban land harmonization (1 ≤ EEC < 5), and economic growth (EEC ≥ 5) (Ouyang and Zhu, 2020; Qiao and Huang, 2021).

Measurement of the LUE

Nighttime light images are closely associated with human economic activities and have been widely used in GDP and population spatialization studies at various spatial scales (Wu et al. 2013; Li and Zhou, 2018; Tan et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2023). Furthermore, for countries and regions with poor quality or missing data, nighttime light data may be a useful supplement to economic indicators (Chen and Nordhaus, 2011). Previous spatialization of socioeconomic data has principally utilized nighttime light data to decompose data proportionally to each pixel. However, the application of this proportional relationship leads to overallocation in suburban areas and underallocation in urban areas (Eberenz et al., 2020). To alleviate this phenomenon, (Zhao et al., 2017) proposed the LitPop method with higher accuracy, which combines nighttime light data with population data to generate lighted population images and then decomposes them proportionally. (Eberenz et al., 2020) further enhanced the LitPop method, leading to its widespread application (Li et al., 2024; Wang and Sun, 2022). Therefore, this paper proposes a framework for measuring LUE based on the LitPop method. The process of measuring LUE includes the following: (i) corrected nighttime light images are cropped based on the urban land area in different years to avoid overestimation of light area caused by the spillover effect of nighttime light data; (ii) based on the improved LitPop method (Eq. (2)) to generate light population images from 1995 to 2020; and (iii) constructed a mapping relationship between the real GDP of each city’s secondary and tertiary industries and light population images; (iv) based on the mapping relationships (Eq. (3)), the real GDP of each city’s secondary and tertiary industries was distributed across a smaller regular grid (1 km × 1 km) to measure LUE in coastal cities. The above LUE measurement framework will help alleviate the saturation effect and more accurately reflect the real economic activities of the city. The formula is as follows:

where \({\rm{Lit}}\) is the pixel value of the nighttime light images, \({\rm{Pop}}\) is the pixel value of the population grid data, \({{LitPop}}_{{pixel}}\) is the pixel value of the \({\rm{LitPop}}\) images, \({{SLP}}_{i}\) is the sum of the pixels in the nighttime light population image of each city, \({{GDP}}_{i}\) is the sum of the real GDP of the secondary and tertiary industries in each city, and \({{LUE}}_{{LitPop}}\) is LUE for each pixel.

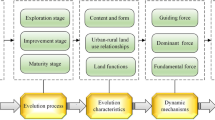

Definition of the ULMEE process

In 1985, the scholar Luis Suarez-Villa proposed the urban life cycle theory, which suggests that cities go through four successive stages: birth, growth, maturity, and recession. A city’s life cycle is determined by the superposition of the life cycles of various economic elements that make up the city’s occurrence and development (Suarez-Villa, 1985). This study expands the micro perspective of the urban life cycle theory based on LUE and applies the theory to the development process of LUE. The life cycle of LUE is a conceptual framework defined as the initial, growth, maturity, and recession stage. The progression of these four stages is the ULMEE process (Fig. 3A). The stages are as follows. (i) Initial stage: Land use types are transformed and urban land is developed from scratch, resulting in a relatively low degree of LUE. (ii) Growth stage: As urbanization progresses and economic development continues, a variety of resources are concentrated on urban land, and LUE shows an increasing trend. (iii) Maturity stage: Land resources are fully developed, the industrial system and structure have become more reasonable, and LUE is steadily expanding and gradually approaching its pinnacle. (iv) Recession stage: Because of the long-term rough growth of urban land, some urban land is idle or semi-idle, causing LUE to enter a decline stage. However, when urban planning prioritizes foresight and strategic planning for urban land transformation in advance (successful transformation of urban land), LUE may reach a new stage of development.

To further concretize ULMEE, the concept of “age” is introduced, defined as the difference between the year of urban land generation (time of conversion from non-urban land to urban land) and the year 2020. For urban land in 1995, the age of urban land from 1995 to 2020 is recorded as 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years (with 5-year intervals). For urban land in 2000, the age from 2000 to 2020 is recorded as 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years (with 5-year intervals); and so on. As the age of urban land increases, the functions of urban land gradually become more complex through economic development (industrial structure upgrading, capital accumulation), policy intervention (intensive land management, spatial planning guidance), and transformation and innovation (improvement of production efficiency), which in turn leads to the improvement of LUE (Fig. 3B). The above process is the maturation and efficiency enhancement process.

Results

Increasingly efficient and intensive urban land in China’s coastal cities

Urban land provides the spatial location for economic development, which promotes its expansion of urban land. The rapid economic development of China’s coastal cities has gradually expanded the scale of urban land, making the degree of coordination between economic development and urban land increasingly important. The EEC of different urban scales has obvious stage characteristics, primarily of two types: economic–urban land basic coordination and economic growth (Fig. 4). Economic growth mainly occurs in three stages: 1995–2000 (super cities, type I large cities, type II large cities, and type I small cities); 2005–2010 (type I small cities); and 2010–2015 (super cities, megacities, medium-sized cities, and type I small cities). All except the economic growth type belong to the economic–urban land basic coordination type. With the continuous advancement of urbanization, industrial agglomeration, and industrial structure optimization processes, coastal cities’ economic growth has been considerably faster than urban land expansion in that they are developing more intensively and efficiently (Li et al., 2020). The decoupling of economic growth from urban land is critical for the sustainable development of coastal cities. To achieve more sustainable decoupled development, it is recommended to promote a three-dimensional development model for urban land, encourage functional replacement of existing land and improve efficiency; at the same time, promote the “multi-plan integration” spatial planning system and strengthen the control of land space use.

Expansion characteristics of urban land

The urban land expansion of coastal cities grew from 8351.82 km2 in 1995 to 30843.52 km2 in 2020, with an average annual growth rate of 899.67 km2. Coastal cities’ urban land expansion has distinct phases, with the largest area of new urban land added between 2005 and 2010. During the study period, the top 10 cities in terms of new urban land area were Tianjin, Dongguan, Tangshan, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Ningbo, Weifang, Quanzhou, Dalian, and Nantong, which are all above the level of a large city, further capitalizing on the locational advantages of large cities. The new urban land exhibits radioactive expansion based on a multi-center ring, or gradual expansion from point to surface, with agglomeration characteristics along the coast and roads (SI, Fig. S1A). There is a gap in the urban land area of different urban scales (SI, Fig. S1B), indicating the pattern of type II large cities > medium-sized cities > super cities > megacities > type I large cities > type I small cities. The urban expansion intensity index and the urban expansion intensity difference index were used to disclose the vertical and horizontal expansion process of urban land, and it was found to have clear stages and fluctuation characteristics (SI, Fig. S1C, and S1D).

Characteristics analysis of LUE

The total economic output of coastal cities increases annually, from 1542.49 billion yuan in 1995 to 17917.18 billion yuan in 2020. The total amount of newly added economic output increased from 1147.94 billion yuan from 1995–2000 to 4340.36 billion yuan during 2015–2020 (SI, Fig. S2A). The total economic output of different urban scales varies as follows: type II large cities > super cities > medium-sized cities > megacities > type I large cities > type I small cities. The LUE of coastal cities is highest in the city center and gradually decreases toward the edge, with distinct spatial heterogeneity within the cities (SI, Fig. S2B). The average LUE of coastal cities continuously increased, from 203 million yuan/km2 in 1995 to 605 million yuan/km2 in 2020, with an average annual increase of 16 million yuan/km2 (SI, Fig. S2D). Comparing the LUE of each city in the six study periods with the average LUE of coastal cities, the LUE of 22, 24, 25, 27, 27, and 22 cities, respectively, is greater than the mean value of coastal cities, indicating spatial differences in LUE and the uneven economic development of coastal cities. Cities of all scales generally follow the rule of increasing LUE annually, although the degree of increase varies (SI, Fig. S2C).

ULMEE process

Figure 5 depicts the total economic output from urban land of various ages between 1995 and 2020, focusing on the differences between coastal cities and diverse urban scales. When the age of urban land increases (the maturation process), whether in coastal cities or different urban scales, the pattern states that the older the urban land, the higher the total economic output. The total economic output of urban land at different ages in coastal cities, ranked in order of size, was urban land in 1995, 2020, 2010, 2005, 2015, and 2000. This result is directly related to differences in the area size and maturation processes. The total economic output of different urban scales does not entirely follow the order of urban scales. Taking urban land in 1995 as an example, by 2020, super cities, type II large cities, and medium-sized cities are the top three performers in terms of total economic output, while megacities, type I large cities, and type I small cities are the bottom three performers.

According to Table 1, the average LUE of coastal cities increased from 323 million yuan/km2 at the age of 5 years to 695 million yuan/km2 at the age of 15 years, and finally to 922 million yuan/km2 at 25 years. These results verify that the maturation process of urban land was accompanied by efficiency enhancement. The LUE at 0 years continuously increased from 205 million yuan/km2 in 2000 to 531 million yuan/km2 in 2020. This demonstrates that the later urban land is developed, the higher the initial LUE. This pattern is strongly related to the urban land growth model, which states that new urban land develops along with the expansion of the original urban land (Chakraborty et al., 2022). On the one hand, when the urban planning department formulates a plan to optimize the urban functional layout, it prioritizes guiding commercial development in a more compact and intensive direction, which promotes the effective aggregation of resources and improves LUE. In contrast, new urban land is developed along previous urban land and can use the original urban land’s infrastructure (e.g., transportation networks), which can improve the LUE of new urban land. To demonstrate the efficiency enhancement process, taking urban land in 1995 as an example, when urban land was just formed, the LUE was at a low level. As urbanization progressed, various material and economic resources accumulated on urban land, and LUE improved gradually. Subsequently, the urban economy has developed steadily, the industrial structure has become more reasonable, and LUE has gradually reached a historical peak.

Urban scale directly reflects urban economic development and has an evident impact on economic growth. Disclosing the efficiency improvement process of urban land is critical for designing development strategies at various urban scales. Comparing the polygons of different colors in Fig. 6 (LUE of different urban scales and at different ages), this study finds the following: (i) Different ages: Overall, there is a trend of continuous improvement in LUE as urban land matures, indicating that the maturation proceeds alongside efficiency enhancement. However, it does not completely conform to the shape of “concentric circles.” Taking urban land in 1995 as an example, the LUE of different urban scales at 25 years is lower than that at 20 years. (ii) Different urban scales: Using urban land in 1995 as an example, as of 2020, the LUE followed the pattern of super cities > type I large cities > megacities > type II large cities > medium-sized cities > type I small cities. This indicates that it does not completely follow the pattern in which the larger the urban scale, the higher the LUE. Comparing the red polygons in Fig. 6 (LUE of different urban scales at the same age), taking the super cities as an example, the LUE for 0 years of age increased from 261 million yuan/km2 in 1995 to 498 million yuan/km2 in 2020, indicating that the later the urban land is developed, the higher its initial LUE.

Can ULMEE meet the demands of future economic growth?

On the one hand, the results in Table 1 and Figs. 5 and 6 confirm the ULMEE process; on the other hand, as of 2020, the percentage of urban land under 15 years is as high as 69%, leaving plenty of potential for ULMEE. This result provides a theoretical basis for determining whether the ULMEE process can meet the needs of future economic growth. Shared socioeconomic pathways depict different development models of the future socioeconomic system and provide multiple development scenarios for predicting LUE (O Neill et al., 2014; O Neill et al., 2017). Therefore, this study applies the SSPs method to predict the LUE of various urban scales at different ages and determines whether relying on the ULMEE process can meet the needs of future economic growth in China’s coastal cities.

A gridded dataset comprising value-added primary, secondary and tertiary industries in China under shared socioeconomic pathways from 2020–2100 is used to predict the LUE of various urban scales at different ages. The LUE at different ages exhibits diverse degrees of growth between 2025 and 2050, with the total LUE shown mostly in the first half of an inverted “U”-shaped curve (SI, Fig. S3). In other word, LUE will be a higher growth degree before 2035, but its growth rate will gradually decline after 2035. From different scenarios of SSPs, in 2025, the difference in LUE predicted by SSP1–SSP5 (sustainability (SSP1), middle of the road (SSP2), regional rivalry (SSP3), inequality (SSP4), and fossil-fueled development (SSP5)) is not significant. As ULMEE progresses, the difference in LUE gradually increases. SSP5 has the highest LUE, whereas SSP3 has the lowest. As of 2050, the LUE of various urban scales at different ages, in descending order, is super cities, type I large cities, megacities, type I small cities, type II large cities, and medium-sized cities.

According to the 2024 Economic and Financial Outlook Report released by the Bank of China Research Institute and the Analysis of China’s Economic Growth Prospects and Dynamics (2015–2050), an expected economic growth target of approximately 5% would meet the demands of China’s future economic development (Tang et al., 2020). A positive future economic development momentum is assumed. Further, based on the total LUE (total economic output of secondary and tertiary industries) predicted by SSPs, it is determined whether relying on the ULMEE process can meet the demands of a 5% urban economic growth rate. According to Fig. 7, except for scenario SSP3, all urban scales can meet economic growth needs before 2035 by relying on ULMEE. The longer it takes to rely on the ULMEE process to meet urban economic growth demands, the later it becomes necessary to add new urban land. After 2040, all urban scales would require additional new urban land to meet economic growth demands. In different scenarios, the time required for different urban scales to expand urban land to meet economic growth needs varies. Type I small cities would rely on the ULMEE process to meet economic growth demands for a longer time and require adding new urban land later.

Based on the perspective of different urban scales, SSPs is used to predict the land use efficiency of various ages. The sum of land use efficiency is compared with the 5% economic growth rate to determine whether urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement process can meet the needs of future economic growth. Blue represents that urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement process can meet the needs of economic growth, while pink represents that it does not meet the needs.

Discussion

Representativeness and typicality of coastal cities

Coastal cities were selected as research objects to explore whether the process of urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement can meet the needs of future economic growth, mainly based on their unique development conditions and demonstration value. In the past 30 years, the population, GDP and urban land area of 51 coastal cities in China accounted for 20.96%, 33.34%, and 55.91% of the national total, respectively. Compared with other cities, the urbanization process of coastal cities faces more complex resource and environmental constraints and development demands (Zhang et al., 2020): on the one hand, coastal cities are usually economically developed, densely populated, and extremely scarce land resources. Urban expansion is often limited by natural barriers such as oceans and mountains, and they have to expand space through special methods such as land reclamation; on the other hand, coastal cities bear the important functions of opening up to the outside world and economic growth engines, and the demand for urban land continues to be strong (Scherner et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2023). This contradiction is more prominent in the context of climate change, and risks such as sea level rise and coastal erosion have further compressed the development space. Simultaneously, coastal cities are often at the forefront of land management system innovation and intensive development. The development models they explored, such as stock renewal, three-dimensional development, and mixed functions, are of great reference significance to other regions. Research on land maturation and efficiency enhancement in coastal cities can reveal the inherent laws of urban development under tight resource constraints and provide practical samples for global implications for developing economies.

Mechanism analysis of ULMEE

As a dependable source of spatial data, point of interest (POI) data provides rich spatial location information and is widely used in urban functional area division and POI recommendation (Liu et al., 2024; Long et al., 2024; Xue et al., 2020). The increasing density and agglomeration characteristics of POI data make it possible to reveal the ULMEE process. The correlation coefficient is calculated based on the coastal city POI kernel density estimation (KDE) index and LUE. The result demonstrates an obvious positive correlation between the two, with a correlation coefficient of 0.57** (**0.01 level (two-tailed); the correlation is significant). Therefore, this study selected a plot with an area of 2.10 km2 in Dalian City, as shown in Fig. 8A. Between 2012 and 2020, the plot’s urban land area increased. The mechanism of the ULMEE process was analyzed using the number of POIs on the plot, the KDE index, and the percentage of their classification. The types of POIs on this plot have increased to residential categories in addition to commercial, industrial, public services, science, and education (Fig. 8B). The number of various POIs is gradually increasing, with the total number of POIs increasing from 114 in 2012 to 290 in 2020. Both the types and quantities of POIs show a trend of gradual improvement and enhancement. As Fig. 8C shows, the KDE index in 2012 ranged from 34.17 to 90.53 and was mostly less than 80. In 2020, it ranged between 35.68 and 275.91, with most values exceeding 100. The progressive increase in the POI KDE index supports the optimization and adjustment of the industrial structure, driving the service level and support capacity of urban land (Xue et al., 2020). Simultaneously, a denser POI indicates that the urban infrastructure layout is more complete, creating greater additional capacity and improving the intensity of urban land development and LUE.

The spatial heterogeneity of LUE within cities reflects the differences in the ULMEE process across different ages of urban land. Based on the spatial heterogeneity of the KDE index (Fig. 9), the POI KDE index in the urban center is significantly higher than that in the edge areas, which is consistent with the spatial pattern of LUE in this study (Fig. S2B). The central areas of coastal cities are often densely populated and have extensive business activities, with high population density and high-quality infrastructure conditions. Simultaneously, the continuous advancement in the ULMEE process has prompted the tertiary industry in urban centers to become the dominant industry, resulting in increased LUE in the central area. With further expansion to the periphery of the city, land policies have become permissive, and urban land expansion may be inefficient (Koroso, 2023). The infrastructure level, such as transportation accessibility in the city periphery, is gradually declining (Guo et al. 2024). Further, the industrial structure may change, and the leading industry may gradually transition from the tertiary to the secondary industry or even the primary industry, limiting the improvement of LUE in the city’s periphery (Wang et al., 2023). Therefore, the spatial heterogeneity of LUE within cities is determined by various factors, such as the economic development level, infrastructure level, population density, and industrial structure.

Differences in the ULMEE process of various urban scales

The POI KDE index of super cities is much greater than that of surrounding cities, with Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen ranked first echelon (Fig. 9). As growth poles, large cities have stronger economic vitality, an improved infrastructure level, and a more advantageous population scale than medium-sized and small cities (Lei et al., 2021). The dense distribution of POI is evidence of these advantages; the POI KDE index further reflects the reasons for the differences in the ULMEE process of different urban scales. This study starts from the perspective of different urban scales and uses the core–periphery theory to explain the reasons for the differences in the ULMEE process across different urban scales. (i) Initial stage: Large cities rely on their location advantages to gradually gather economic resources, transforming them into the economic cores (core areas) of the entire region, while small cities become the influence areas (edge areas) for large cities. Simultaneously, the core area strengthens its control over the edge area and obtains production materials through control and production effects, while the core areas provide goods, information, and technology to the edge areas. At this stage, there is no major variation in the ULMEE process between the core and periphery areas. (ii) Growth stage: Large cities rely on the agglomeration of economic resources and scale effects to accelerate economic development. The polarization impact is substantially stronger than the diffusion effect, steadily widening the gap in ULMEE between large and small cities. (iii) Maturity stage: As the growth pole of regional economic development, large cities have continuously optimized industrial structures and play an important role in driving and boosting the development of surrounding economies. Due to the continuous development and agglomeration of industries and population in large cities, environmental pressure is increasing, forcing some economic activities and production factors in large cities to spread and transfer to small cities, hence promoting the ULMEE process in small cities. The ULMEE process of large and small cities develops in a coordinated manner at this stage, and LUE of the two progressively peaks. (iv) Recession stage: As the scale of urban land area in large and small cities continues to expand, long-term extensive growth results in idle or semi-idle conditions in urban land, causing a recession in LUE. However, when cities formulate suitable policies ahead of time to assist in the transformation of urban land, the ULMEE process will advance to the increasing stage.

Recommendations and limitations

The coordinated development of land use and economic output is an important aspect of urban economic growth, and the spatial mapping of urban economic growth is LUE (Y. Wu et al., 2013). A city’s location characteristics and spatial layout influence the level of urban economic development and LUE (Schiavina et al., 2022). Natural resources, the ecological environment, and climatic conditions play key roles in urban economic development, determining the urban leading industries and the economic direction. As areas with intensive economic activities, coastal cities have highly fragile ecosystems, therefore, more attention should be paid to the protection of the ecological environment to lay a solid foundation for sustainable and high-quality development in the future. The central place theory provides a theoretical foundation for urban spatial layout and defines three growth modes of urban land (infill, edge, and leapfrog expansion). This study found that LUE decreases in the following order: infill, edge, and leapfrog expansion (X. Guo et al., 2024). Therefore, the dominant pattern of urban land expansion in China’s coastal cities should shift toward a filling type, minimizing edge and leapfrog urban sprawl.

To support the sustained economic development of China’s coastal cities in the face of limited land resources, coastal cities can reduce their dependence on urban land increment by improving LUE. They should deepen and innovate the intensive utilization system of land resources and effectively revitalize idle urban land to control the inefficient expansion of urban scale. Coastal cities should also formulate strategies for industrial transformation, rationally allocate the functional layout of urban land development, strengthen and improve the urban transportation network, and enhance LUE (Wu et al., 2017). Population density has a positive pulling effect on LUE (Xue et al., 2022). Super cities and megacities should promote weight reduction and fitness strategies among citizens, and reasonably control population density. In other cities, population agglomeration should be appropriately guided to raise population density. In addition, promoting regional integration and industrial structure optimization and upgrading would contribute to the effective circulation of factors, have a positive impact on the sustainable use of urban land, and thereby effectively enhance LUE (Liu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021).

The land use efficiency life cycle theory (ULMEE) proposed in this study aims to systematically reveal the dynamic laws and internal mechanisms of the evolution of land use efficiency in coastal cities. As a preliminary conceptual analysis framework, the theory still needs to be further studied in the following aspects: first, it is necessary to incorporate key driving factors such as technological breakthroughs, and industrial upgrading to construct a multi-dimensional explanation system; second, a quantifiable and verifiable evaluation indicator system should be established for each development stage of the theory; finally, by improving the dynamic response mechanism of the framework, it can more accurately depict the nonlinear evolution characteristics of land use efficiency in the process of urban development. The continuous improvement of this theoretical framework will provide a more explanatory and predictive analysis tool for urban land use research. This study did not adequately account for changes in characteristics such as the economic development stages and urbanization level of different cities (Chen et al., 2016). To comprehensively and systematically reveal the ULMEE process, future research should cover multiple regions, especially areas with relatively underdeveloped economies, to provide a theoretical foundation for achieving the efficient integration and coordinated development of urban land and social economy.

Conclusion

China’s coastal cities are experiencing rapid urbanization, leading to challenges such as unreasonable land use structure and indiscriminate urban scale expansion. The contradiction between economic development and land resource allocation has become increasingly prominent. As an important basis for optimizing efficient land use, LUE fully reflects the degree of intensive use of land resources and the status of human economic activities. This study selected 51 coastal cities, the core areas of China’s economic development, and proposed a novel LUE measurement method based on data fusion. This method overcomes the limitations of administrative divisions and displays LUE with more spatial information at the pixel scale. It shows that ULMEE process is based on increased overall economic production from urban land of various ages and enhanced LUE. Applying the SSPs method to predict the LUE of urban land of different ages, this study determined whether the ULMEE process could meet the needs of future economic growth and predicts when new urban land is required to meet the demands of economic growth.

Understanding the spatial heterogeneity of LUE in coastal cities will help alleviate issues such as idleness and inefficient use of urban land. Exploring the ULMEE process would help reveal the inherent mechanisms and LUE’s evolution characteristics. Assessing whether urban land meets the needs of future economic growth based on the ULMEE process of urban land provides a theoretical basis for regulating the scale of new urban land and ensuring sustainable development. These findings can inform urban land development and utilization patterns and serve as a reference for adjusting the spatial layout and optimizing land resource allocation. They can also serve as a reference for the expansion of urban land and economic development patterns in other cities, especially in developing countries. In conclusion, this study underscores the importance of balancing growth with efficient land use in coastal cities. By implementing strategies to enhance LUE and control urban sprawl, coastal cities can achieve sustainable and high-quality development, paving the way for a prosperous future.

Data availability

The original datasets used in the studyare included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Borrelli P, Robinson DA, Panagos P et al. (2020) Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015–2070). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117(36):21994–22001. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2001403117

Bren d'Amour C, Reitsma F, Baiocchi G et al. (2017) Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 114(34):8939–8944. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606036114

Cao K, Deng Y, Wang W et al. (2023) The spatial heterogeneity and dynamics of land redevelopment: Evidence from 287 Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 132:106760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106760

Chakraborty S, Maity I, Dadashpoor H et al. (2022) Building in or out? Examining urban expansion patterns and land use efficiency across the global sample of 466 cities with million+ inhabitants. Habitat Int 120:102503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102503

Chan FKS, Chen WY, Sang Y et al. (2021) Build in prevention and preparedness to improve climate resilience in coastal cities: Lessons from China’s GBA. One Earth 4(10):1356–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.09.016

Chen G, Li X, Liu X et al. (2020) Global projections of future urban land expansion under shared socioeconomic pathways. Nat Comm 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14386-x

Chen X, Nordhaus WD (2011) Using luminosity data as a proxy for economic statistics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 108(21):8589–8594. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017031108

Chen Y, Chen Z, Xu G et al. (2016) Built-up land efficiency in urban China: Insights from the General Land Use Plan (2006–2020). Habitat Int 51:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.10.014

Eberenz S, Stocker D, Röösli T et al. (2020) Asset exposure data for global physical risk assessment. Earth Syst Sci Data 12(2):817–833. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-817-2020

Guo C, Zhou W, Jing C et al. (2024) Mapping and measuring urban–rural inequalities in accessibility to social infrastructures. Geogr Sustain 5(1):41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2023.11.004

Guo X, Chen Y, Jia Z et al. (2024) Spatial and temporal inequity of urban land use efficiency in China: A perspective of dynamic expansion. Environ Impact Asses 104:107357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107357

Han B, Jin X, Sun R et al. (2023) Understanding land–use sustainability with a systematical framework: An evaluation case of China. Land Use Policy 132:106767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106767

He S, Yu S, Li G et al. (2020) Exploring the influence of urban form on land–use efficiency from a spatiotemporal heterogeneity perspective: Evidence from 336 Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 95:104576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104576

Hong C, Zhang Q, Zhang Y et al. (2019) Impacts of climate change on future air quality and human health in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 116(35):17193–17200. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812881116

Huang Y, Chen T, Hu D et al. (2023) Spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of urban ecological space availability in coastal cities of China during rapid urbanization. Ecol Indic 154:110757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110757

Huang Z, An X, Cai X et al. (2023) The impact of new urbanization on PM2.5 concentration based on spatial spillover effects: Evidence from 283 cities in China. Sustain Cities Soc 90:104386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104386

Huang Z, He C, Wang W (2013) Land use changes and urban economic growth in China. Urban Dev Stud 20(7):35–43. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-3862.2013.07.006

Jing C, Su B, Zhai J et al. (2022) Gridded value–added of primary, secondary and tertiary industries in China under Shard Socioeconomic Pathways. Sci Data 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01440-0

Koroso NH (2023) Urban land policy and urban land use efficiency: An analysis based on remote sensing and institutional credibility thesis. Land Use Policy 132:106827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106827

Lei W, Jiao L, Xu Z et al. (2021) Scaling of urban economic outputs: insights both from urban population size and population mobility. Comput Environ Urban 88:101657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2021.101657

Li X, Deng Y, Liu B et al. (2024) GDP spatial differentiation in the perspective of urban functional zones. Cities 151:105126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105126

Li X, Zhou W (2018) Dasymetric mapping of urban population in China based on radiance corrected DMSP–OLS nighttime light and land cover data. Sci Total Environ 643:1248–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.244

Li Y, Shu B, Wu Q (2014) Urban land use efficency in China: Spatial and temporal characteristics, regional difference and influence factors. Econ Geogr 34(01):133–139. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2014.01.017

Li Z, Luan W, Zhang Z et al. (2020) Relationship between urban construction land expansion and population/economic growth in Liaoning Province, China. Land Use Policy 99:105022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105022

Liao X, Fang C, Shu T et al. (2023) Spatiotemporal impacts of urban structure upon urban land-use efficiency: Evidence from 280 cities in China. Habitat Int 131:102727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102727

Liu J, Hou X, Wang Z et al. (2021) Study the effect of industrial structure optimization on urban land–use efficiency in China. Land Use Policy 105:105390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105390

Liu S, Xiao W, Li L et al. (2020) Urban land use efficiency and improvement potential in China: A stochastic frontier analysis. Land Use Policy 99:105046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105046

Liu T, Liu H, Qi Y (2015) Construction land expansion and cultivated land protection in urbanizing China: Insights from national land surveys, 1996–2006. Habitat Int 46:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.10.019

Liu X, Huang Y, Xu X et al. (2020) High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nat Sustain 3(7):564–570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0521-x

Liu Z, Meng L, Sheng QZ et al. (2024) POI recommendation for random groups based on cooperative graph neural networks. Inf. Process. Manag. 61(3):103676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2024.103676

Long Y, Wu Y, Huang L et al. (2024) Assessing urban livability in Shanghai through an open source data–driven approach. Npj Urban Sustainability 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-024-00146-z

Luo G, Wu C (2003) Comparative study on urban land use efficiency. Econ Geogr 23(3):367–370. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8462.2003.03.018. 392

Meyfroidt P, de Bremond A, Ryan CM et al. (2022) Ten facts about land systems for sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 119 (7). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2109217118

O Neill BC, Kriegler E, Ebi KL et al. (2017) The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Global Environ Chang 42:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.01.004

O Neill BC, Kriegler E, Riahi K et al. (2014) A new scenario framework for climate change research: the concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change 122(3):387–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0905-2

Ouyang X, Zhu X (2020) Spatio-temporal characteristics of urban land expansion in Chinese urban agglomerations. Acta Geographica Sinica 75(03):571–588

Pandey B, Brelsford C, Seto KC (2022) Infrastructure inequality is a characteristic of urbanization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 119 (15). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119890119

Qiao W, Huang X (2021) Patterns of urban land expansion and its driving forces in Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Econ Geogr 41(09):162–173

Scherner F, Horta PA, de Oliveira EC et al. (2013) Coastal urbanization leads to remarkable seaweed species loss and community shifts along the SW Atlantic. Mar Pollut Bull 76(1-2):106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.09.019

Schiavina M, Melchiorri M, Freire S et al. (2022) Land use efficiency of functional urban areas: Global pattern and evolution of development trajectories. Habitat Int 123:102543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102543

Shi L, Liu F, Zhang Z et al. (2015) Spatial differences of coastal urban expansion in China from 1970s to 2013. Chinese Geogr Sci 25(4):389–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-015-0765-y

Song Y, Yeung G, Zhu D et al. (2022) Efficiency of urban land use in China’s resource–based cities, 2000–2018. Land Use Policy 115:106009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106009

Suarez-Villa L (1985) Urban growth and manufacturing change in the United States–Mexico borderlands: A conceptual framework and an empirical analysis. The Annals of Regional Science 19(3):54–108

Tan M, Li X, Li S et al. (2018) Modeling population density based on nighttime light images and land use data in China. Appl Geogr 90:239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.12.012

Tang D, Liu X, Ni H et al. (2020) The changing global economic landscape and China’s potential growth rate and high–quality development in the post-epidemic era. Econ. Res. J 55(08):4–23

Wang K, Li G, Liu H (2021) Does natural resources supervision improve construction land use efficiency: Evidence from China. J Environ Manag 297:113317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113317

Wang T, Sun F (2022) Global gridded GDP data set consistent with the shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Data. 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01300-x

Wang Z, Fu H, Liu H et al. (2023) Urban development sustainability, industrial structure adjustment, and land use efficiency in China. Sustain Cities Soc 89:104338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104338

Winkler K, Fuchs R, Rounsevell M et al. (2021) Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat Comm 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22702-2

Wu C, Wei YD, Huang X et al. (2017) Economic transition, spatial development and urban land use efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Habitat Int 63:67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.03.012

Wu H, Fang S, Zhang C et al. (2022) Exploring the impact of urban form on urban land use efficiency under low-carbon emission constraints: A case study in China’s Yellow River Basin. J Environ Manag 311:114866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114866

Wu J, Wang Z, Li W et al. (2013) Exploring factors affecting the relationship between light consumption and GDP based on DMSP/OLS nighttime satellite imagery. Remote Sens Environ 134:111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2013.03.001

Wu T, Tasoglou A, Wagner DN et al. (2024) Modern buildings act as a dynamic source and sink for urban air pollutants. Cell Reports Sustainability 1(5):100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2024.100103

Wu Y, Wu C, Luo W (2013) Research on the influencing factors and the effects on urban land economic density based on the geonomics perspective. China Land Science 27(1):26–33. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-8158.2013.01.004

Xu X, Bao A, Chang C et al. (2017) Characteristics of urban built–up expansion and coordination of man-land allocation in the major cities in Xinjiang. Econ Geogr 37(10):92–99

Xue B, Xiao X, Li J (2020) Identification method and empirical study of urban industrial spatial relationship based on POI big data: A case of Shenyang City, China. Geogr Sustain 1(2):152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2020.06.003

Xue D, Yue L, Ahmad F et al. (2022) Empirical investigation of urban land use efficiency and influencing factors of the Yellow River basin Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 117:106117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106117

Yang C, Liu H, Li Q et al. (2022) Human expansion into Asian highlands in the 21st Century and its effects. Nat Comm 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32648-8

Yang D, Luan W (2024) Spatial-temporal patterns of urban land use efficiency in China’s national special economic parks. Ecol Indic 163:111959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111959

Zhang W, Chang WJ, Zhu ZC et al. (2020) Landscape ecological risk assessment of Chinese coastal cities based on land use change. Appl Geogr 117:102174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102174

Zhang W, Wang B, Wang J et al. (2022) How does industrial agglomeration affect urban land use efficiency? A spatial analysis of Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 119:106178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106178

Zhao J, Zhu D, Cheng J et al. (2021) Does regional economic integration promote urban land use efficiency? Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta, China. Habitat Int 116:102404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102404

Zhao N, Liu Y, Cao G et al. (2017) Forecasting China’s GDP at the pixel level using nighttime lights time series and population images. Gisci. & Remote. Sens. 54(3):407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2016.1276705

Zheng M, Huang W, Xu G et al. (2023) Spatial gradients of urban land density and nighttime light intensity in 30 global megacities. Hum Soc Sci Comm 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01884-8

Zhou L, Dickinson RE, Tian Y et al. (2004) Evidence for a significant urbanization effect on climate in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 101(26):9540–9544. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0400357101

Zhu X, Li Y, Zhang P et al. (2019) Temporal–spatial characteristics of urban land use efficiency of China’s 35mega cities based on DEA: Decomposing technology and scale efficiency. Land Use Policy 88:104083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104083

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42030409).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.X.L. and J.Y. contributed to all aspects of this work; X.L. collected the data, performed experiments and computational analysis, and wrote the manuscript; X.X., D.Y., Q.Q.L., Z.L., Z.P.S., and G.C. reviewed, edited and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, X., Luan, W., Yang, J. et al. Can urban land maturation and efficiency enhancement meet future economic growth demands in China’s coastal cities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06024-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06024-y