Abstract

Exploring the framing in the Chinese government's disaster science communication, as well as whether there are differences in framing between routine and emergency periods of a disaster, can help summarize the models of government-led science communication for disaster risk reduction. This study takes the content related to science communication on rainstorm disasters from the Chinese government’s 82 official Weibo accounts as the research object, and utilizes LDA topic modeling and sentiment lexicon matching to explore the three-tiered framing under both routine and emergency periods. The high-level framing explores the communication themes. Six themes were discovered, corresponding to three types of scientific knowledge: practical, theoretical, and conceptual. The mid-level framing examines the content preferences of the government in routine and emergency periods. It was found that the routine period focuses more on communicating theoretical and conceptual scientific knowledge, while the emergency period places more emphasis on the communication of practical scientific knowledge. The low-level framing explores the government’s emotional expression strategies in routine and emergency periods it was observed that in the routine period, encouraging and guiding expressions account for a higher proportion, while in the emergency period, conciliatory, mandatory, and emphasis expressions account for a higher proportion. These findings can serve as an effective complement to the scientific communication for disaster risk reduction efforts carried out by scientists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compared with other types of science communication, disaster science communication is closely associated with public safety and physical health. Disaster science communication can spread the knowledge of self-rescue and mutual-rescue and improve the public’s risk awareness, thus serving as the most effective, economical, and safest approach to the reduction of losses from disasters (Weichselgartner and Pigeon, 2015; Kondo et al. 2019). In 2022, a number of Chinese government agencies jointly issued the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for the Development of National Science and Technology Communication, which specifically proposed that the Government should establish and improve national mechanisms for disaster science communicationFootnote 1. Among the many kinds of disasters, the communication of scientific knowledge on rainstorms is particularly important because they are common and cannot be prevented by means of prevention, but if they are handled appropriately, the damage can be greatly mitigated. China has suffered greatly from the devastation of rainstorm disasters. The “2021.7.20 Henan (a province in China) Rainstorm” disaster caused a direct economic loss of 120.06 billion yuan (around US$17.15 billion)Footnote 2. And the “2023.7.31 Beijing Rainstorm” event resulted in 33 fatalities and 18 people missingFootnote 3. In China, the government bears the main responsibility for disaster response. What communication strategies can be used by the government to effectively spread scientific knowledge about rainstorms to the public has become a pressing issue. And disaster science is spread conveniently due to the widespread development of social media (Panagiotopoulos et al. 2016; Ghosh et al. 2018). In particular, social media is used by the government as the most official channel for science communication (Kavanaugh et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2013), which demonstrates the significance of clearly defining its framing in communication.

Social media use amplifies public attention to disasters (Liu and Han, 2025), while government-led science communication on these platforms enhances public disaster response capabilities. At present, the research on disaster science communication is conducted from the aspects of communication subjects, communication content, and communication channels. From the perspective of communication subjects, the researchers explore the strategies of communicators, the needs and acceptance of receivers, and the interaction between the two sides. Such research covers the analysis of, shaping public understanding of scientific issues by experts (Mikulak, 2011; Hu et al. 2018; Ballo et al. 2024), the role of scientists in crisis risk communication (Haynes et al. 2008; Andreastuti et al. 2023), the effects of science communication (Longnecker, 2023), the role of different institution in science communication (Maier et al. 2016; Deng, 2024), public attitudes towards the dissemination of scientific knowledge (Allum et al. 2008; Gong et al. 2022), dissemination, dialog and participation of three kinds of crisis information communication mode (Stewart, 2024) and so forth. From the perspective of communication content, the research focuses on the influence of communication content on audience attention (Dvir-Gvirsman, 2017; Dai and Wang, 2023), narrative of science in information communication (Jones and Anderson, 2017; Hutchins, 2020), communication of information in public health events (Li et al. 2021), public response at different stages of disaster development (Xu et al. 2020). From the perspective of communication channels, the research focuses on communication platforms, such as the selection of different ways of communication in emergency events (Xie et al. 2017; Hinata et al. 2024), the role of social media in the communication of crisis events (Eckert et al. 2018; Reuter et al. 2018), and the credibility of disaster science communication on social media (Zimmermann et al. 2024). A comprehensive review of the current research field reveals that there are many unexplored dimensions in disaster science communication. Firstly, although the communication of scientific knowledge during the emergency response period following a disaster event has been widely researched, the exploration of science communication in the stage of early warning and routine times of disaster risk is still weak. Second, current research focuses on the influence of key opinion leaders or famous scientists on social media platforms, while there is a lack of analysis on the communication effects and strategies of the government as an authoritative information source. Finally, in terms of research methodology, most of the existing studies rely on qualitative research and text content analysis, and attempts can be made to introduce machine learning technology and natural language processing to achieve in-depth analysis, so as to enrich the perspective and depth of research.

The three-level framing theory is a very influential news framing theory, which was put forward by Tsang Kuo-jen (1999). Accordingly, this paper adopts the Three-Level Framing Theory, collects the research samples from the posts of government agencies’ official accounts on Sina Weibo related to rainstorms, and explores the method of machine learning. Based on the three-level framing, this paper describes the high-, mid-, and low-level framing of the government’s science communication. In the high-level framing, the scientific communication topics of rainstorm were analyzed; in the mid-level framing, the content preferences of government departments were analyzed both in the routine period and emergency period; in the low-level framing, the government’s emotional expressions were analyzed both in the routine period and emergency period.

Literature review

Framing theory and its development

Originating from sociology and psychology, the framing theory was introduced into journalism and communication in the 1980s, which attracted great attention. The concept of “framing” was traced back to A Theory of Play and Fantasy (Gregory Bateson, 1972). He believed that framing is a limited explanatory context, which means that both parties share the interpretation rules of the content transmitted. In the following developments, sociologists and psychologists have further explored the concept of “framing”. Sociologist Erving Goffman (1974) defined framing as a cognitive structure that people use to recognize and explain social life experience, and as “a set of rules that individuals use to convert social life experience into subjective cognition”. In the field of communication, Gamson (1975) developed the framing theory. He believed that collective action framing is a framing built by social movement organizations or groups to change the social status quo, including diagnostic frame, prognostic frame and motivational frame. The media plays an important role in this shift in the framing of collective action. Entman (1993) believed that framing involves selection and prominence. Framing is to select certain aspects of perceived reality and make them more prominent in communication texts, which can contribute to the definition of a unique problem, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and solution-related advice. Scheufele (1999) analyzed how framing affects audience attitudes and behaviors through news reports. He proposes the multiple levels of framing and explores how framing shapes social cognition in news reporting. Gitlin (2003) defined the term “framing” as “media framing” which is “the criteria used for selection, emphasis, and representation on what exists, happens, and makes sense”.

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), which emphasizes responsibility attribution and context-adjusted strategies (Coombs, 2017), offers a new approach for managing crisis events effectively. Combining SCCT with the three-level framing theory not only addresses the limitations of traditional crisis communication theories, particularly in terms of content hierarchy and emotional expression, but also helps governments develop scientifically grounded communication strategies during public crises such as natural disasters or pandemics. This integration allows for the optimization of information structure and tone of expression. Previous studies have demonstrated the value of this combined approach. Claeys and Cauberghe (2014) examined how emotional and rational frames influence public trust. Similarly, Niu and Ma (2023) distinguished various emotional message frames through the lens of framing theory and SCCT. Schwarz and Diers-Lawson (2024) focused on communication content and how media or organizations shape public interpretations of crises by “highlighting specific elements”, arguing that integrating SCCT and framing theory reveals how narratives and meanings are constructed in crisis contexts. Nashmi and Bashir (2024) investigated how the Kuwaiti government employed “instructive” and “adjustive” messages via Twitter during the pandemic, reflecting SCCT’s core strategies. Tian and Yang (2022) found that political actors used SCCT strategies aligned with their policy goals, generating distinct patterns of public response on social media. Thus, incorporating SCCT into the analysis of government communication during rainstorm-related crises enhances understanding of government responsibility, facilitates public action, and fosters trust—ultimately contributing to the achievement of public goals.

The analytical structure of the three-level framing

Based on the existing theories and concepts abroad, Tsang Kuo-jen (1999) decomposed the concept of “framing” into three analytical levels. He believed that framing is the thinking form of processing information, which comprises structures that fall under analogous systems and are divided into three levels: high, middle, and low, which can be understood as the role of communication subjects and content at different levels and their impact on the audience. These views coincide with those of Gamson (1975), Entman (1993), and Scheufele (1999), who divide framing into three levels, making the analysis of framing effects clearer. This framing goes beyond the potential ambiguity or simplicity that may have characterized earlier framing analyses. The analytical structure of the three-level framing presents a more systematic, multi-dimensional, and holistic analytical structure. It further summarizes the viewpoints of previous scholars and extends to social reality and subjective reality (Linjing, 2022). Specifically, it outlines a clear and coherent set of analytical steps. These steps enable researchers to conduct a hierarchical analysis, starting from macroscopic themes and gradually delving into microscopic language elements. This approach effectively circumvents fragmented or one-sided interpretations. Moreover, this framing clearly differentiates between the various levels of framing functions. Zhang (2022) adopted the analytical logic of the three-level framing approach in his analysis of the narrative framing of social actors in China Daily, summarizing government responsibility at the high level, analyzing role attribution at the mid-level, and examining language choices at the low level. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2020), in their study on crisis collective memory making on social media, also followed the logic of this three-tiered framing. A substantial number of studies on communication frameworks can be classified according to this framing. For these reasons, we adopt it as the fundamental research framework (Fig. 1).

High-level: the communication theme

Tsang (1999) defined that the high-level framing reflects the communication theme in various contexts. Many scholars’ research on communication framing aligns with Tsang’s description of this high-level framing. Ng and Tan (2021) examined A comparison of news themes in different cultural contexts. Imran et al. (2015) discussed. The main topics of media information during emergencies. Singh et al. (2019) explored the Classification of information communication in natural disasters. Tian et al. (2024) described Topics related to the sustainable development of education in China. Hu et al. (2024) summarized. Themes of public religious cultural communication on social media. A high-level framing analysis of the government’s scientific communication on heavy rainfall should also focus on the theme of its communication, thus giving rise to the first research question.

RQ1: What are the communication themes in the government’s science communication about rainstorms, and do these themes differ between routine and emergency phases?

Mid-level: the content preferences

Tsang (1999) believed that the mid-level framing emphasizes building identity among specific social groups. It focuses on the content preferences of different departments. Many scholars’ research of communication framing also conforms to the description of the mid-level framing. Scott and Errett (2018) summarized communication preferences of disaster information dissemination on social media; Hong et al. (2017) generalized. The difference between public and government communication of disaster content. Focusing on the research of this article, the mid-level framing will pay attention to how different government departments choose different communication topics. It will also focus on the division of labor and collaboration logic among departments and the tracing of behavioral motivations. Ultimately, it aims to depict the process in which these departments work together to complete the dissemination of scientific information about rainstorms. Therefore, the second research question are proposed

RQ2: What are the distinct communication themes selected by different government departments, and do these choices vary between routine and emergency phases?

Low-level: the emotional expressions

Tsang (1999) argues that the low-level framing is mainly formed by language, symbols, and rhetoric, which are combined into the external expression and embody the direct interpretation and feedback of the individual to the information. The mode of expression in the process of communication is also a key focus of common concern among scholars. Warnick (2001) focused on the application of rhetorical criticism in mass media. Meadows et al. (2022) focused on the semantic network of official media regarding the COVID-19 epidemic. Han et al. (2022) focused on the contrast between official and public emotional expression regarding disasters. Shen et al. (2025) used social media data from Weibo to conduct topic modeling and sentiment analysis of public discourse regarding the earthquake in Turkey and Syria. Nagel et al. (2012) focused on verbal, visual, and vocal communication in political communication. Focusing on the research of this article, the low-level framing research focuses on the external manifestations of information communication, including metaphor, emotional semantics, and symbolic expression. By directly activating readers’ cognitive schemas through specific symbols, it evokes emotional responses and thereby influences the public’s cognition and behavior regarding rainstorm disasters. Therefore, the third research question of this study is proposed as follows:

RQ3: What emotional expressions are present in the government’s science communication about rainstorms, and do these expressions differ between routine and emergency phases?

Data and methods

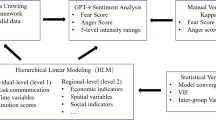

The data sources and research methods of this study are shown in Fig. 2. First, analysis data are obtained through big data text mining. Then, the study is conducted using the LDA topic model from unsupervised machine learning and sentiment semantic analysis from supervised machine learning.

Data sources and processing

By the end of September 2023, Sina Weibo, the largest social media platform in China, registered 605 million monthly active users and 260 million daily active usersFootnote 4, which demonstrated its large user base. Meanwhile, the vast majority of government agencies have signed up their official Weibo accounts, which can provide basic data for this study. Therefore, Sina Weibo is selected as the data source for this study.

On September 18, 2020, the Opinions on Further Strengthening Emergency Science Communication and Education Work were jointly issued by five government agencies in ChinaFootnote 5. The policy indicates that the China Association for Science and Technology, the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, the National Health Commission, and the Emergency Management Department of the People’s Republic of China are the main institutions for disseminating scientific knowledge about rainstorms. When choosing Weibo accounts, we first focused on the official accounts of these five departments since each province has its own provincial-level subordinate departments. We further selected the accounts of the subordinate institutions of 31 provinces (municipalities), excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan. Eventually, we determined 82 official Weibo accounts. These accounts are the main force in science communication and present a subordinate relationship between central and local institutions. The responsibilities of the departments are similar, which is more conducive to grasping and understanding the communication content of similar departments at both the central and local levels.

The search function on Sina Weibo was utilized to retrieve keywords related to scientific knowledge about rainstorm The selected keywords strictly follow the Chinese emergency management terminology system and the communication practices of Chinese government's new media to ensure the complete capture of the target content. It includes disaster-type terms such as "rainstorm, flood, typhoon, mudslide", etc., covering the main meteorological derivative disaster chains defined in the “National Natural Disaster Relief Emergency Plan”, to avoid sample omission due to the search for a single disaster term. The terms of communication forms, including "popular science, emergency popular science, and knowledge popularization", etc., are officially expressed in the “Outline of the National Action Plan for Improving Public Scientific Literacy” issued by the State Council. Among them, "emergency popular science" is the core concept currently promoted by the Chinese government. Academic benchmarking terms include "science communication, knowledge dissemination, flood control knowledge, and disaster prevention tips", supplementing general academic expression terms to prevent the loss of content in government documents that is not marked as "popular science" but is essentially science communication. And try to conduct a combined search on these phrases. The terms of communication forms, including "popular science, emergency popular science, and knowledge popularization", etc., are officially expressed in the "Outline of the National Action Plan for Improving Public Scientific Literacy" issued by the State Council. Among them, "emergency popular science" is the core concept currently promoted by the Chinese government. The time of data selection was set for the three years following the release of the Opinions, spanning from September 18, 2020, to September 18, 2023.

To compile the corpus of this study, Python was employed to gather data on science communication on rainstorms from the official Weibo accounts of 82 central and local governments. We used a three-round screening standard to screen 7027 pieces of data. First, use machine preprocessing. Data was screened out through the removal of HTML tags, special characters, URLs, and other unnecessary elements, thus ensuring that the text analysis object is pure semantic content. Secondly, conduct manual interpretation. Non-popular science content, government announcements, interactive instructions, and other content have been deleted. Finally, carry out the deduplication process. The same account has been deleted for repeatedly pushing the same content within one day. After irrelevant and duplicate information was removed through review and filtering, a final data set of 4008 Weibo posts was obtained for this study. On the basis of China’s geographical location and climate features, the routine period is defined as the period of occasional rainstorms, ranging from October to April of the following year, and the emergency period is defined as the period of frequent rainstorms, ranging from May to September every year. The two periods serve as a standard of two sub-corpora classification'sFootnote 6.

Unsupervised machine learning: LDA topic modeling

The latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) topic model is usually used for unsupervised topic identification and extraction of large amounts of text data. It is a probabilistic generative model and has wide applications in text mining, natural language processing, and information dissemination analysis. This method is widely applied in topic identification, topic evolution, public opinion analysis, sentiment analysis, and discourse analysis. In terms of theme identification, Xie et al. (2022) identified the theme of science communication of the Chinese government during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Mutanga et al. (2022) identified the theme tweets of the South African government regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of public opinion analysis, Zhang et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2021) analyzed the evolution law of online public opinion themes. In terms of user demand analysis, Xie et al. (2021) analyzed the public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic on Weibo. Surian et al. (2016) described the public’s views and discussions on HPV vaccines on Twitter. In terms of discourse analysis, Brookes and McEnery (2019) evaluated the usability of LDA in the study of media and policy discourse from the perspective of discourse analysis. Schönfeld et al. (2018) conducted a policy discourse analysis in United Nations speeches using LDA. As LDA topic recognition does not rely on manually predefined classifications, it automatically mines structured communication topics, avoiding human subjectivity. Each topic can be described by keywords, which is convenient for understanding what "government science communication content" is. Especially in the research of government scientific information dissemination, LDA can effectively identify the underlying semantic structure and discourse patterns behind the text, providing a solid methodological foundation for understanding the dissemination content, identifying the issue structure, and predicting the dissemination effect.

First, the LDA topic modeling was used to identify the topics of science communication on rainstorms, the python-based GenSim (General Simulation) was adopted to conduct the modeling work of those topics, the Jieba library was utilized for text pre-processing, which includes the process of word segmentation and the removal of Chinese stop words in the posts of science communication on rainstorm. The LDA topic modeling was calculated for the extraction and naming of the topics according to the information related to science communication on rainstorms.

Second, content preferences were identified according to the evolution of LDA topics. TF-IDF calculation was conducted on the two sub-corpora of the routine period and the emergency one, feature extraction was used to identify buzzwords, and the topic popularity was visualized. Through this process, the evolution of topics and the dynamics of buzzwords were concluded, which clarified the content preferences of the communication subjects.

Supervised machine learning: emotional Thesaurus matching

Emotion synonym database matching has significant advantages in tasks such as Chinese sentiment analysis, government text mining, and public opinion sentiment recognition. Especially in contexts where data is scarce, semantic expressions are diverse, and explanatory requirements are strong, the combination of sentiment dictionaries and supervised learning plays an irreplaceable role.

Firstly, the library of emotional thesaurus was established. There are different types of emotion classifications in the existing studies. Some studies emphasized that attention should be paid to reducing the public's sense of panic by expressing empathy during the dissemination of disaster information (Liu et al. 2011). Some scholars divided the Chinese government's strategies for emotional expression in disaster events into instructing information, adjusting information, advocacy, and bolstering (Li et al. 2022). Some scholars proposed that the government should use emphasis, bolstering, and minimizing in the process of crisis communication (Coombs, 2007). Chinese scholars have summarized the strategies of the government’s disaster communication into guidance information, debugging information, reshaping information, reminding information, and dilution information (Shi and Qiu, 2018). Based on the existing classification, this paper divides the emotional expressions in the government Weibo accounts into five categories: conciliatory expressions, encouraging, mandatory, guiding, and emphasis. Five categories of expressions were selected through small-sample manual interpretation and high-frequency word analysis, and expert consultation was conducted to establish a government sentiment expression lexicon (Table 1).

Secondly, emotional labels were defined. These labels were extracted based on the features of the Bag of Words. A logistic regression model was trained through the function of the logistic regression in the scikit-learn library, and a logistic regression sentiment classifier was trained through the annotated data and extracted features. These trained models were evaluated and optimized.

Thirdly, a thesaurus match was conducted. A sentiment word-based statistical method was employed in this study. When a specific category of sentiment word appeared, the count for that category increased by "1". The frequency of sentiment expressions was then calculated. The word frequency analysis results were further normalized to obtain the final coefficients, enabling the identification and confirmation of sentiment expressions in the texts of the science communication on rainstorms.

Determination of the number of themes

First, perplexity was chosen as two factors of mutual verification to check and determine the optimal number of topics. Perplexity focuses on the generalization ability of the model. According to the total amount of corpus data, the maximum number of topics was set to 10, and the degree of perplexity and coherence were measured, respectively. In terms of perplexity calculation, as the number of topics increased, the perplexity continued to decrease. When the number of topics reached 6, the perplexity reached a tipping point and presented the minimum value (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, according to the results of the pyLDAvis visualization (Fig. 4), when 'K' (the number of topics) reached "6", the overlap between topics is relatively low, and the classification is quite effective. Therefore, the number of topics was set to "6".

Results and analysis

High-level framing: themes identification

After the theme extraction of the content related to science communication on rainstorms in the official Weibo accounts, 6 topics were obtained. The final topic naming came from the human interpretation of the text content with topic extraction results and representative feature words (Table 2). The content of these extracted topics shows clear connotations. Despite some overlaps in the keywords of extracted topics, these topics generally demonstrated accurate content and direction of science communication on rainstorms. Topic 1 is concluded as the guideline for avoiding the dangers of traffic travel and outdoor activities, including the dangerous scenarios and self-rescue measures of traffic travel in rainstorms, as well as the precautions and avoidance strategies of outdoor rainstorms. Topic 2 is summarized as the safety tips for post-rain diets and epidemic prevention, including precautions for potential health issues and epidemic prevention in the aftermath of the rainstorm. Topic 3 is concluded as lightning protection and safety guidance on electricity use in rainstorms, such as the safety precautions of electricity use at home or outside during rainstorms and thunderstorms, as well as guidelines for preventing and avoiding lightning strikes in open places or mountainous areas. Topic 4 is summarized as the formation and self-rescue of secondary disasters caused by rainstorms. This topic introduces the potential secondary disasters of rainstorms, explains their causes and occurrence principles, and popularizes their prevention, management, and survival skills. Topic 5 is concluded as safety in business operations and home life, covering personal home safety and business production safety before and after the rainstorm. Topic 6 is summarized as rainstorm warnings and the explanation of rainstorm causes, shedding light on two aspects of information: early warning and forecast of the rainstorm disaster, and explanation of its formation conditions and causes.

Types of scientific knowledge

After further analysis and classification of the above-mentioned six themes, it can be found that the six themes of science communication on rainstorms can be categorized as three types of scientific knowledge: practical knowledge, theoretical knowledge, and conceptual knowledge. To gain a clearer understanding of these six types of themes related to the dissemination of scientific information about heavy rain, these themes have been further classified at the knowledge level to help readers better understand how the government authorities disseminate scientific knowledge to the public through the Internet. The dissemination of scientific knowledge, especially that during disasters, can be based on the content of the information (Paul, 2001). It is classified in multiple dimensions such as communication purpose (Stewart, 2024) and communication timing (Girard et al. 2014). Gilbert et al. (1998) proposed that scientific understanding should encompass three types of knowledge: descriptive knowledge, explanatory knowledge, and procedural knowledge. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) classified knowledge into four categories: factual knowledge, conceptual knowledge, procedural knowledge, and metacognitive knowledge. This paper integrates these viewpoints and further classifies the themes of government scientific information dissemination on rainstorms in China into three categories: Practical knowledge, Theoretical knowledge and Conceptual knowledge.

The Practical knowledge concept emphasizes that the information released by the government should provide the public with specific and actionable content, focusing on "what to do and how to do it", and offering the public concrete and executable operations. For example, when a disaster occurs, key information such as evacuation and emergency rescue should be clearly informed to the public (Rollason et al. 2018), enabling the public to independently judge the disaster situation and take corresponding actions based on this information (Cooper et al. 2022). This risk communication aims to clearly present action options and operational guidelines, promoting the transformation of public awareness into practical actions (Mostafiz et al. 2022). Studies have shown that providing targeted practical information can significantly improve the response rate of residents to disaster response measures (Ping et al. 2016). In the dissemination of information on rainstorm disasters, in addition to practical guidance on "what to do and how to do it", the government also needs to systematically explain Theoretical knowledge on "why to do it this way" in order to truly enhance the public’s understanding of risks and their ability to act. Lazrus et al. (2016) emphasized that in information dissemination, physical mechanisms such as water level rise and their triggering conditions should be explained to help the public understand the scientific logic of early warning for correct decision-making. Rogers (1975) proposed the theory of protection motivation. He also emphasized that only by first allowing the audience to scientifically perceive the threat and clarifying the disaster mechanism and occurrence probability through theoretical information can disaster prevention actions be stimulated. Conceptual knowledge involves values, information trust, etc., focusing on "how to view disaster risks and information itself", and requires the formation of risk responsibility attribution and the shaping of risk culture. The research indicates that risk communication not only focuses on facts but also emphasizes trust, transparency, and public participation (Boholm, 2019), which are at the core of building public trust and social resilience. Dressel (2015) proposed the individual-oriented, state-oriented, and fatalistic orientation of "risk culture", analyzed its role in crisis communication, and sorted out the conceptual content in crisis communication. Loroño-Leturiondo et al. (2019) pointed out that the dissemination of scientific information and risk communication must adopt a two-way communication strategy to help the public accurately assess the value of disasters and trust the government, which is an important part of communication.

Practical knowledge, covered in Topics 1 and 3, focuses on operating guidelines for the public during rainstorms, such as risk avoidance and lightning protection. This type of science communication provides actionable skills and information to help the public prepare for and respond effectively to rainstorms. As a foundational element, it enables people to make informed decisions and take appropriate action. Theoretical knowledge, presented in Topics 4 and 6, includes professional information on rainstorm causes, climate science, and early warning systems. Its purpose is to deepen public understanding, enhance scientific literacy, and raise awareness of disaster prevention. As the core of science communication, this knowledge helps the public form a sound understanding of rainstorms and take informed action. Conceptual knowledge, found in Topics 2 and 5, emphasizes public safety awareness, responsibility, and mutual assistance. Its goal is to shape disaster prevention behaviors and foster societal synergy in responding to rainstorms. This type of knowledge lays the groundwork for the public to understand and apply emergency principles effectively.

LDA topic weights present the characteristics of knowledge distribution and communication. Through the calculation of LDA, we obtained the weights and proportions of the six topics in each piece of Weibo data. Finally, the total weights of the six topics in 4008 pieces of data were calculated. According to the calculation results, practical knowledge holds a dominant position, closely followed by theoretical knowledge, and then conceptual knowledge. Practical knowledge holds the highest proportion, reaching 34.53%. Among them, the proportion of the routine period is 2.95%, and the proportion of the emergency period is 31.58%. It means that among the three types of knowledge, practical knowledge occupies a dominant position in terms of communication frequency and quantity, highlighting its importance in the current science communication on rainstorms. Theoretical knowledge takes the second place, accounting for 33.9%, of which 2.54% is in the routine period and 31.36% is in the emergency period. This indicates that apart from practical knowledge, theoretical knowledge has been given considerable attention in the communication system of science communication on rainstorms. Introducing the causes and scientific knowledge of rainstorms to the public helps to correctly understand the harmfulness and severity of rainstorms. The proportion of conceptual knowledge in the communication, albeit being the lowest, accounting for 31.54%, including 2.76% in the routine period and 28.78% in the emergency period. Conceptual knowledge, which usually involves views, attitudes, and values on events, plays a critical role in improving the public awareness and behavioral standards of rainstorm response.

Comparison of themes

After clarifying the themes and types of knowledge of the government in the dissemination of scientific information on rainstorm disasters, the differences between these themes during routine and emergency periods were analyzed. Based on the output of the LDA topic model and the degree of support, this paper calculated the topic intensity of science communication on rainstorms at various stages and developed a table of topic popularity to visually assess the level of topic intensity at each stage (Fig. 5).

Theme selection in the routine periods

In the routine periods, the change of preference of each theme fluctuates obviously, and the popularity difference between themes is large. In terms of topic focus, official governments attached greater importance to the communication of principle knowledge during the routine periods, and to the introduction of basic knowledge, including the causes, development, and prevention measures of rainstorms. In Fig. 5, Stage 1 (September 2020 to April 2021), Stage 3 (October 2021 to April 2022), and Stage 5 (October 2022 to April 2023) belonged to the routine periods. In those periods, the popularity of different topics is quite different, which shows a clear preference for the communication topics of science communication on rainstorms. Topics 4 and 5 are significantly higher than other topics, which is especially prominent at Stage 3 from September 2021 to April 2022. Among these topics, Topic 4 and Topic 5 belong to theoretical knowledge and conceptual knowledge, respectively. Such a communication strategy fully reflects the government’s emphasis on theoretical knowledge and conceptual knowledge during the relatively stable development of the scenario. These two types of knowledge not only enhance the public understanding of rainstorms, but also improve their awareness of disaster prevention and mitigation, and self-protection ability in daily life.

Theme selection in the emergency periods

In the emergency periods, the change in preference for each topic fluctuates less, and the popularity difference between themes is smaller. In terms of topic focus, as the rainstorm is often accompanied by great danger and uncertainty, the science communication of official governments focuses on the communication of practical escape skills. Stage 2 (May 2021–September 2021), Stage 4 (May 2022–September 2022), and Stage 6 (May 2023–September 2023) in Fig. 5 belonged to the period of frequent rainstorms in the emergency periods. According to the analysis of the popularity map, the popularity of different topics in the emergency periods is less changeable than that in the routine periods, which shows that the government has adopted a comprehensive and extensive communication strategy in the emergency periods to ensure all topic content is adequately covered. Among the more balanced popularity levels, Topics 1 and 3 stand out, both involving practical knowledge, which aligns with the characteristics of the emergency periods where the government focuses on providing the public with guidance that can be translated into appropriate response behaviors.

Mid-level framing: content preferences

The analysis of the mid-level framing mainly explores the content preferences of the science communication of various government departments under the “routine-emergency” scenario. To explore the content preferences of different government departments, this paper further conducts a cross-analysis of themes and subjects under different periods in the analysis of the mid-level framing strategy. The purpose of introducing the analysis of communication subjects is to reveal the roles and functions of different subjects in the communication of science communication on rainstorm information. The 82 official Weibo accounts are divided into the emergency management system, public health system, scientific communication system, and government publicity system, which can help understand the contribution and impact of these four systems in the science communication on rainstorms. Figure 6 adopts the cross-analysis method to obtain the topics of science communication used by these four systems of government departments under the routine periods.

Content preferences in the routine periods

It can be seen that the content preferences of different government departments vary greatly (Fig. 6a). The emergency management system focuses on spreading theoretical and conceptual knowledge with the frequent use of Topics 4 and 5. The public health system emphasizes the communication of practical and theoretical knowledge with the predominant uses of Topics 1 and 4. Both the scientific communication system and the government publicity system prefer to spread conceptual and theoretical knowledge through the frequent use of Topics 2 and 4. It can be concluded that under the routine periods, these four systems all attach great importance to the communication of theoretical knowledge. Furthermore, the public health system tends to spread practical knowledge, whereas the emergency management system, public health system, scientific communication system, and the government publicity system all tend to spread conceptual knowledge. Such a difference can be explained by the routine work and practical application of the public health system.

Content preferences in the emergency periods

In the emergency periods, each subject often adopts relatively consistent strategies to spread the six topics (Fig. 6b). In emergencies, each subject tends to adopt similar communication methods and content to convey key information quickly and effectively, and ensure the punctuality and accuracy of information. This consistent communication strategy not only improves the efficiency and coverage of information communication, but also enhances the public’s trust in the official media system. The more timely, comprehensive, and frequent the communication of science communication on rainstorms, the more capable the public becomes in perceiving the severity of disasters (Gholami et al. 2011) and then taking proactive and efficient risk countermeasures. Based on common understanding and shared goals, this communication method can enhance the effectiveness of science communication on rainstorms and reduce the losses caused by disasters.

Low-level framing strategy: emotional expressions

Through the emotional lexicon matching in supervised machine learning, this paper identifies the proportion of the proportions of government expressions in the “routine-emergency” scenario, including conciliatory expressions, encouraging expressions, mandatory expressions, guiding expression, and expressions of emphasis (Fig. 7).

Emotional expressions in the routine periods

The proportion of encouraging expressions and guiding expressions in the routine periods of occasional rainstorms is higher than that in the emergency periods (Fig. 7). Such a difference can be explained by the non-urgency of the routine periods, where the government aims to provide guidance for the public in a more moderate and positive way to raise their awareness of disaster prevention and mitigation. The government adopts encouraging expressions to bolster public enthusiasm for participation and their confidence, and subsequently to support and implement the government initiatives of rainstorm response. Meanwhile, the government employs guiding expressions to promote the appropriate behavior and coping methods of rainstorm response, encourage the public to learn various escape and self-rescue skills in advance, take preventive measures, and guide the public to take appropriate actions. As a way to enhance the public enthusiasm for participation, encouraging expressions focus on rainstorm prevention, but guiding expressions provide specific action guidelines that help the public take targeted preventive measures. In the routine periods, these two expressions can enhance public awareness of disaster prevention and mitigation and strengthen the ability of the whole society to cope with rainstorms.

Emotional expressions in the emergency periods

Conciliatory expressions, mandatory expressions, and emphasis expressions showed an obvious increase in their proportions in the emergency periods (Fig. 7). The official Weibo accounts employ conciliatory expressions, a rational and conciliatory approach that can relieve the excessive anxiety of the public and steer them towards a less panicked and anxious state. The strategy of using conciliatory expressions can stabilize social sentiment and create a favorable environment for subsequent crisis response. Meanwhile, in the emergency periods, the government tends to adopt mandatory expressions, highlighting what the public "must do" and "cannot do", with the goal of regulating and restricting public behavior. The strategy of utilizing mandatory expressions is based on the provision of clear instructions and regulations to ensure that the public takes the appropriate actions in rainstorms and reduces potential losses. Furthermore, the government also resorts to emphatic expressions that can highlight the severity and influence of rainstorms to arouse great public concern and attention. The strategy of utilizing emphasis expressions can enhance public awareness of the crisis and ensure prudent actions and risk avoidance of the public during rainstorms.

Discussion

The strategy of content system building

Based on the high-level framing, we analyzed theme identification and answered RQ1. From the perspective of the current communication topic, the government is striving to popularize emergency science knowledge that is content-oriented, actively building a communication system for science communication on disaster (Wang et al. 2024). This study found that practical knowledge and theoretical knowledge are highlighted in the content of the current science communication, with the subtle incorporation of conceptual knowledge. The relationship between these six types of topics and the three types of knowledge content is shown in Fig. 8. Practical knowledge, including Topic 1 (Guidelines for traffic and outdoor risk avoidance) and Topic 3 (Lightning protection and electrical safety guidance). These two themes emphasize the most practical action manual when facing heavy rain, simply and directly informing the public what the correct approach is when encountering danger or potential danger, such as the precautions for driving in the rain and the correct way to deal with water accumulation while driving. How to avoid being struck by lightning when outdoors and the serious consequences of being struck by lightning. On the one hand, these disseminated contents can effectively convey the correct measures and methods for avoiding risks to the public. On the other hand, they can also draw the public’s attention to rainstorm disasters and enhance their risk perception. The fundamental purpose of the dissemination of such content is to urge the public to take the right actions in the face of rainstorm disasters. Studies have confirmed that the correct way of communication and clearly informing the public of the correct practices can reduce unnecessary disaster consequences (Lowrey et al. 2007; Akbar et al. 2025). The torrential rain in Zhengzhou, China, on 20 July was precisely caused by the wrong behaviors of some members of the public, which led to the tragedy.Footnote 7. In China's Law on Responding to Emergencies, it is clearly stipulated that "publicity and popularization activities of emergency knowledge to the public and necessary emergency drills should be carried out", and "news media should conduct public welfare publicity on laws and regulations on responding to emergencies, prevention and emergency response, self-rescue and mutual rescue knowledge, etc."Footnote 8, This also indicates from the side the importance of practical knowledge in the communication of emergency science.

Theoretical knowledge, including Topic 4 (Formation and prevention of secondary disasters caused by rainstorm) and Topic 6 (Rainstorm warning and rainstorm cause explanation). These two themes are explaining the principles to the public, helping them understand the causes of extreme weather and why secondary disasters occur, such as the conditions for mudslides to form, the precursors before typhoons, and the relationship between El Nino and meteorological disasters, etc. The fundamental purpose of disseminating such content is to understand the basic principles of disaster occurrence and help the public form the correct concept of attaching importance to disasters and respecting nature. As Pavitt (2000) pointed out, an important purpose of the dissemination of scientific information is to inform the public of the reasons behind phenomena rather than merely emphasizing actions. The research by Weichselgartner and Pigeon (2015) demonstrated that understanding the principles of disasters is a key prerequisite for taking appropriate actions, merely transmitting information is insufficient to guide actions. The public must understand the background mechanism and the consequences of system interaction in order to make adaptive responses. Gaillard and Mercer (2013) also hold that information is merely the starting point of action, but what truly drives disaster reduction actions is processed knowledge. In practice, the heavy rain in Beijing in 2023 also proved to us that, due to early warning and evacuation measures, the number of casualties was significantly lower than that of similar disasters in historyFootnote 9. This is consistent with the guiding ideology and policy guidelines in the Popular Science Law, which emphasize the dissemination of the essence, logic, and way of thinking of science in terms of "scientific thought" and "scientific spirit", rather than simply the indoctrination of skills. It also stresses that "we should adhere to the scientific spirit, oppose and resist pseudoscience, and only by disseminating scientific thought and logical methods can the public possess critical thinking and identify pseudoscience".

Conceptual knowledge, including Topic 2 (Dietary health and epidemic prevention safety after rain) andTopic 5 (Enterprise production and home safety). The content of these two themes is to help the public form good living habits and concepts. For instance, it is necessary to help the public establish healthy and hygienic habits after disasters, refrain from drinking untreated sewage, stay away from areas with unknown water sources, and form correct production and living habits to avoid potential safety hazards caused by bad habits. Appleby-Arnold et al. (2021) hold that the cultivation of this habit helps the public establish a correct disaster concept, thereby achieving the ultimate goal of science communication and improving the overall disaster literacy of citizens. The management measures for emergency Response plans for sudden incidents emphasize "providing 'easy-to-understand, memorable and commonly used' publicity materials" and "grasping and investigating the emergency resources held by relevant units and residents in the region"Footnote 10. This is conducive to enabling the public to master emergency knowledge and form good emergency behavior habits through regular publicity and popularization.

The purpose and focus of communication content in routine and emergency periods should be clearly distinguished, with a more prominent emphasis on different types of communication in each phase. In the routine period, communication should primarily serve the goals of popular science education and awareness-building. The objective is to enhance the public's long-term capacity for disaster prevention by popularizing the causes of rainstorms and disseminating disaster prevention knowledge and skills. In this stage, greater attention should be paid to the communication of conceptual and theoretical knowledge, which remains underrepresented. Importantly, the communication process should not be one-way: it is essential to build an interactive mechanism among government agencies, experts, and the public, where authorities provide authoritative content, experts interpret and explain scientific principles, and the public is encouraged to engage actively through questions and feedback. The use of engaging formats such as interactive games, expert-led lectures, and online Q&A platforms can help foster mutual understanding and increase the attractiveness of science communication.

In the emergency period, the purpose of science communication shifts toward emergency alerts and practical action-oriented information, aiming to deliver real-time updates on the rainstorm and provide guidance on risk avoidance to support a timely public response. Although the communication at this stage increasingly focuses on practical knowledge, further refinement is necessary–for instance, by clearly presenting early warning signals, risk alerts, evacuation routes, and emergency contact channels. To improve effectiveness, the emergency communication system should also maintain close collaboration among governments, scientific experts, and citizens, ensuring that the public receives accurate, timely, and easily actionable information through trusted channels.

The strategy of communication preferences

Based on the mid-level framing, we analyzed content preferences and answered RQ2. From the perspective of the mid-level framing, the analysis of the content preferences in official science communication on disaster revealed that the four systems of official sources lacked distinct characteristics in their content preferences. It is necessary to further design the content and knowledge in different departments of disaster science communication by utilizing the rainstorm scenario. Based on SCCT, a "scenario–responsibility–source" analysis was designed to construct the content of science communication for different government departments.

The tasks and positions of the four systems vary in terms of responsibilities. The emergency management system is responsible for the safe management of disasters, the emergency rescue of rainstorms, and the communication of emergency knowledge and skills. Specifically, in the emergency period, we should pay attention to the early warning information, such as rainstorm level, impact scope, and duration. Update the disaster situation, including water points and rescue progress. As well as to provide the public with a guide to safety, including the introduction of escape techniques and escape tools. In the routine period, it mainly focuses on policy interpretation, including publicity of the emergency plan and the disaster insurance system; Carry out typical case publicity, including the promotion and encouragement of disaster relief hero stories and successful risk aversion cases. The public health system bears the responsibility for health emergency work, disease prevention and control during rainstorms, post-disaster medical and health rescue, and the training drills of medical rescue. In the emergency period, it is necessary to provide post-disaster epidemic prevention knowledge, such as drinking water disinfection, environmental cleanup, and infectious disease prevention; Provide first aid skills, such as drowning first aid, trauma treatment; Provide mental health support, such as post-disaster psychological adjustment methods.

In the routine period, there is a need to provide information on the prevention of storm-related diseases and promote healthy lifestyles. The scientific communication system is responsible for improving the scientific literacy of the whole people, popularizing science and technology, and promoting practical technology. In the emergency period, the system should pay attention to the scientific explanation of the cause of rainstorm, such as meteorological conditions and rainfall mechanism; Scientific interpretation of secondary disasters, such as the formation principle of flood and debris flow; And the technical popularization of rainstorm disaster prevention. In the routine period, attention will be paid to the systematic popularization of rainstorm scientific knowledge and interactive science popularization activities, such as online Q&A. The government publicity system is responsible for promptly releasing and spreading information after rainstorms, maintaining close communication with the public, addressing public concerns and questions, following up on the progress of the incident in a timely manner, and announcing government countermeasures and risk warnings. In the emergency period, the system needs to issue authoritative rainstorm warnings and disaster information in a unified manner to ensure the authority of information. There is also a need to coordinate media coverage to spread positive energy and relief stories. In addition, it is necessary to clarify rumors and guide the public to properly deal with disasters. In the routine period, it is necessary to publicize disaster prevention and reduction policies, shoot and disseminate relevant public service advertisements and publicity films, and encourage the public to participate in disaster prevention and reduction work through positive publicity.

Therefore, the responsibilities of these four communication systems should be associated with the specific scenarios of rainstorms, including the outdoor risk avoidance scenario, rescue scenario, health protection scenario, and disaster early warning scenario, which can highlight the professional focus and role differentiation among emergency communication systems, define the precise position of different subjects, and shape a cycle of knowledge communication. Meanwhile, in terms of sources, it is important to strengthen the construction of science communication teams. It is essential to develop a science communication team equipped with professional knowledge and communication skills, responsible for planning, producing, and promoting science communication content. In particular, building cooperation with authoritative experts and public figures is crucial to enhancing the credibility and recognition of science communication on disasters.

The strategy of emotional expressions

Based on the low-level framing, we analyzed emotional expressions and answered RQ2. Emotional expressions play a vital role in the dissemination of rainstorm emergency science knowledge by official media. As a link between the individual and the public, emotion is constantly constructed in social interaction. The analysis and exploration of emotional tendencies provide a new angle and direction for people to explain complex social and cultural phenomena (Zou, 2020). The emotional expressions of a government are a process of constructing and conveying specific meanings, values, and ideologies through certain forms, contents, and strategies of discourse expressions. As an authoritative platform of official information, the government's official Weibo accounts adopt an emotional expression strategy in the dissemination of rainstorm emergency science knowledge, which is not only related to the efficiency of information communication, but also directly affects the public perception and attitude to disasters. In the past, the undesired effect of information dissemination and the public distrust of government discourse were explained by the problems of the communication discourse in crisis events, including the lack of emotional appeal, the lack of rhetorical devices in dealing with a crisis, and the lack of rational appeal in rhetorical behavior (Howarth et al. 2021). The difference in emotional expression between the public and government media shapes public mood and understanding, and fosters public resonance in disaster management (Han et al., 2022). Therefore, improve the government's emotional expression strategy in the dissemination of emergency science knowledge, adopt emotional expression through rhetorical devices, value transmission, and cultural shaping, continuously improve the government's mobilization capability in the dissemination of crisis event knowledge, and guide the public to understand, accept, and agree the intention and position behind the discourse of science communication on disaster.

Different approaches should be adopted for scientific information dissemination depending on the period, as public mental states, communication objectives, and information needs vary. During emergency periods, the public is prone to panic, so emotional expression should focus on calming emotions, providing a sense of security, and enhancing confidence. Ulmer et al.'s (2022) research also indicates that organizations (including governments) need to demonstrate care, commitment, and transparency, advocating that communication should focus on “what we can do” rather than overemphasizing "how bad things are", so as not to cause panic or confusion. The public's nervous and anxious state requires emotional reassurance and immediate support. Brashers (2001) expressed the emotional comfort of the government, conveyed the commitment of "facing together", indirectly reduced the sense of helplessness, enhanced the sense of control over the system, and strengthened the public's confidence and trust in the government when facing disasters. When official media adopt the "Emotional Solidarity Framing", they are more likely to win public trust (Kim and Niederdeppe, 2013). Given the urgency of the situation, emotional expression should emphasize action. Scientific communication should use concise, direct language with short sentences, clear instructions, and a sense of urgency. Vaughan and Tinker (2009) emphasized that information needs to be clear, specific, feasible, and endowed with a sense of efficacy. Avoid using threatening or overly technical language. A study on the readability of COVID-19 prevention guidelines found that simple and understandable language expression can also reduce the action cost for the public and enable them to easily master scientific knowledge (Basch et al. 2022). Real-time interaction with the public is essential to provide emotional support, achieving a balance between warmth and warning in emotional expression.

In routine periods, the public's psychological state is relatively stable, so emotional expression should prioritize education and inspiration to improve disaster prevention awareness and scientific literacy. Excessive emphasis on the severity of threats can trigger avoidance psychology. On the contrary, cultivating the public's disaster literacy and using practical and encouraging expressions can trigger stronger Self-Efficacy and Response Efficacy, making it easier for the public to accept and cooperate (Floyd et al. 2000). The confidence building of "can do" (verbal persuasion/self-efficacy messages) and the social norm framing are more effective than simple risk alerts (Lim, 2021). Compared with fear appeals, the expression is based on empowerment and optimism. In non-emergency situations, it is more likely to promote continuous behavioral change and the improvement of readiness attitudes (Levy and Bodas, 2024). The long-term value of disaster prevention and mitigation should be conveyed by encouraging the public to actively learn about rainstorms. Since the public is less attentive during non-emergency periods, scientific information risks being overlooked. Therefore, language should be more detailed, vivid, and engaging, with a focus on interaction and interest to capture public attention. Joubert et al. (2019) found that if science communication can integrate emotional connection and narrative arc structure, it will greatly enhance the audience’s participation, understanding, and information recall. Sundin et al. (2018) packaged complex research in the form of stories, which not only enhanced the participation and knowledge retention of the target group, but also increased the possibility of their willingness to act, especially with remarkable effects in the communication related to environmental decision-making.

Regardless of the period, emotional expression in disaster-related science communication should adhere to the following principles. In terms of rhetorical devices, five strategies should be combined. Highlight mandatory actions with words like "must", "remember", and "never", while promoting voluntary participation with expressions such as "try", "suggest", and "master in advance". This approach balances compulsory requirements with evocative language, emphasizing both emotional care and objective argumentation, blending education with encouragement. For value transmission, the first task is aligning emotion with cognition. Science communication should convey rational information while enhancing appeal through emotional elements. Describing specific scenarios can improve the public's risk perception of rainstorms. Dahlstrom (2014) holds that when communicating science to non-expert audiences, the narrative form of communication should not be overlooked. Narrative offers greater understanding, interest, and engagement. Sickler and Lentzner (2022) hold that personal narrative style can enhance audience immersion and identification in science communication, thereby improving the communication effect. The second task is resonating emotionally with the audience. Stories or plots that connect closely with the audience are more likely to evoke strong emotional responses. Kampmann and Pedell (2022) found that the story format can reduce the audience’s sensitivity to their own risk preferences, thereby shaping a generally higher level of action engagement. The research of Lejano et al. (2018) shows that for those groups with lower sensitivity to information, storytelling content is more understandable and acceptable than traditional technical announcement communication, thereby enabling the public to have a sense of participation and response awareness. The third task is diversifying emotional expression. Combining text, symbols, and visuals can strengthen public engagement and memory. In cultural shaping, emotional expressions should reflect the government's principle of prioritizing people and their lives. When designing science communication, if visual and textual elements are appropriately combined, it can more effectively guide the public to pay attention to and understand risky content (Sutton et al, 2021). Van Rompay et al. (2010) compared plain text and social media risk posts containing charts. The latter significantly enhanced risk perception, information perception, and willingness to share, indicating that the combination of text and images has more communicative power than plain text. Public feelings should be considered during information dissemination, helping them recognize the practical value of disaster science communication. Efforts should be made to break psychological barriers between the media and the public, guide rational public opinion, maintain social balance, foster a positive government image, and narrow the gap between the government and the public. This aims to build a shared societal concern for rainstorm preparedness.

Conclusions

Research conclusions

This paper collects the research data from the posts of Weibo's government affairs related to science communication on rainstorms, adopts the "three-level structure of news media framing" to explore and identify the framing of science communication on rainstorms by the government, and explains the similarities and differences of science communication on rainstorms in the emergency periods and the routine periods. Based on the traditional method of text analysis and qualitative analysis, this paper attempts to use the LDA topic model in unsupervised machine learning and emotion analysis in supervised machine learning to explore the three-level (high-, mid-, and low-level) framing strategy of different stages. The research findings of this paper are as follows.

In the high-level topic identification, six topics of science communication on rainstorm were discovered, including the guidelines of traffic travel and outdoor risk avoidance, post-rainstorm dietary and epidemic prevention advice, the guidance of lightning protection and electricity safety in rainstorms, the secondary disasters caused by rainstorms and self-rescue skills, safety in business operations and daily lives, the warning and causes of rainstorms. These six popular science themes are further divided into three types of knowledge content: practical, theoretical, and conceptual. Based on these findings, a tiered communication strategy is recommended, where conceptual knowledge should be emphasized in routine periods to cultivate disaster awareness, while practical and theoretical knowledge should be prioritized during emergencies to enhance public response capability. Policymakers should support multi-actor collaboration among government, experts, and communities to develop adaptive content and deliver it through diversified, accessible formats tailored to different audiences.

In the mid-level content preferences, the preference selection of communication subjects, the preferences for theme selection among the four types of government communication systems exhibit a fundamental consistency in the emergency periods, whereas, in the routine periods, these systems have yet to converge towards a unified communication direction. Based on this, it is recommended that government agencies adopt the principle of contextual adjustment in science communication–shifting the focus of content depending on the disaster phase to ensure seamless integration of front-end and back-end information. At the same time, responsibility attribution should be clarified to establish a coordinated mechanism across different entities. For instance, local governments should take the lead in localizing practical information, central authorities should promote theoretical knowledge in a coordinated manner, and experts and media should assume responsibility for guiding public understanding through conceptual knowledge during routine times. Together, these efforts can help systematically enhance public disaster literacy.

Based on the analysis of low-level emotional expressions in rainstorm science communication, it is evident that different emotional strategies are applied depending on the context: conciliatory, mandatory, and emphasis expressions dominate during emergency periods, while encouraging and guiding expressions are more common during routine periods. This variation indicates that policymakers need to adopt scenario-specific emotional communication strategies that align with the public's psychological states and needs. In emergency phases, authoritative and emphatic messaging helps maintain public order and compliance; during routine phases, encouragement and guidance promote active engagement and enhance public risk awareness and preparedness. Therefore, disaster communication policies should institutionalize flexible emotional framing, train communicators to balance firmness and empathy, and tailor messages to effectively both soothe and motivate the public across different disaster stages.

Implications and limitations

The first significance of this paper is to break through the limitations of the method. On the basis of the text analysis of news report information in traditional research, the LDA topic modeling of unsupervised machine learning is combined with the emotion analysis of supervised machine learning, and computer algorithms are deployed to identify communication topics and evolution processes, which can reduce the influence of the subjective judgments on research results, expand the sample size of the research, and improve the objectivity and reliability of the research. The second significance is to broaden the research perspective. The framing theory of journalism and communication is integrated with the emergency management of public management, while methods and paths are explored on how to improve the emergency literacy of the whole people and the mastery of emergency knowledge. This integration adopts the framing theory as a fundamental support and the dissemination of rainstorm knowledge as a pivotal aspect of the research. This interdisciplinary research perspective has brought new inspirations to the research in the fields of journalism, communication, and public management. The third contribution of this research is to enrich the research content. This paper creatively divides science communication on rainstorms into two scenarios: routine and emergency, and compares and discusses the similarities and differences of science communication on rainstorms in different scenarios. Such classification not only provides a new research perspective for science communication on disaster research, but also provides a certain reference direction for the future practice of science communication on rainstorms.

In addition, this study offers several policy implications for improving disaster communication framing in China. First, it suggests that local emergency management authorities adopt differentiated communication strategies according to the disaster phase–prioritizing practical and action-oriented knowledge during emergencies, and focusing on conceptual and theoretical knowledge in routine times to build long-term public awareness. Second, it is important to strengthen the attribution of responsibility in the dissemination of scientific information on stormwater and the adaptation of communication strategies to specific contexts. Government departments have different responsibilities and positions, and the roles of these departments in disseminating information should be further refined. Third, emotional expressions should be strategically used in official communication to guide public behavior without inciting panic–conciliatory and mandatory expressions during emergencies, and encouraging or guiding ones during routine periods. Finally, the study recommends that the content system of science communication be embedded into local emergency plans and drills, aligning knowledge dissemination with protocols outlined in the Emergency Response Law, Science Popularization Law, and Emergency Plan Management Measures. These measures can enhance the institutionalization and effectiveness of disaster communication at the grassroots level.

However, this study has several limitations that warrant further attention. First, in selecting official Weibo accounts, we primarily focused on analyzing the content of science communication, rather than the actual communication effects or the level of public engagement. This limits our understanding of how different audiences perceive and respond to rainstorm-related information. Future research should integrate audience interaction data, such as likes, comments, shares, and sentiment analysis of user feedback, to assess the effectiveness and reception of different communication strategies. Second, the identification and categorization of framing strategies relied on manual coding and inductive interpretation, which introduces a degree of subjectivity. Although this process was conducted rigorously, the potential for bias remains. Future studies could apply automated or semi-supervised machine learning techniques to enhance the consistency and replicability of frame classification, and test these categories across a broader dataset to validate generalizability. By addressing these limitations, future research can offer a more comprehensive and empirically grounded understanding of government science communication in disaster contexts.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Furthermore, the data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Secondary sources and data were publicly available at the time of submission and are provided in the supplementary information accompanying this article.

Notes

China’s flood season varies by region, but considering the seven major rivers, the period from May to September is defined as the frequent rainstorm phase, representing the emergency stage for rainstorm disaster prevention. The period from October to April of the following year is the occasional rainstorm phase, representing the routine stage for rainstorm disaster prevention.

References

Akbar S, Ekasari S, Asy’ari F (2025) Crisis communication effectiveness in disaster management: case studies and lessons. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Bus 4(2):251–263

Allum N, Sturgis P, Tabourazi D et al. (2008) Science knowledge and attitudes across cultures: a meta-analysis. Public Underst Sci 17(1):35–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506070159

Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR (2001) A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives: complete edition. Addison Wesley Longman, Inc

Andreastuti SD, Paripurno ET, Subandriyo S et al. (2023) Volcano disaster risk management during crisis: implementation of risk communication in Indonesia. J Appl Volcano 12:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13617-023-00129-2