Abstract

This systematic review, that followed the PRISMA framework, examined whether Audience Response Systems (ARS) effectively enhance learning and motivation in higher education. Three research questions were posed: (1) concerning the methodological quality of studies on ARS, (2) regarding the psychoeducational variables studied when using ARS, and (3) about the impact of ARS on learning. The literature search was conducted in Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and ERIC, yielding a total of 653 records. After the screening process, the number was reduced to 135, of which 79 were rejected based on exclusion criteria. Finally, 11 studies were selected for the review (653 → 135 → 11). The results indicate that the methodology and data analysis of the reviewed studies are not very robust, showing limitations in variable control and a limited use of validated instruments for data collection. The main psychoeducational variables investigated include performance, motivation, student engagement and satisfaction. As for the effect on learning, it is demonstrated that there is no consensus in the literature regarding how ARS contribute to academic performance. Currently, there is a debate about the real impact of these applications in higher education despite their popularity. Kahoot! is, by far, the most widely used audience response system in classrooms, surpassing Mentimeter, Socrative, or Wooclap. This review concludes, in line with similar works, that it is necessary to improve the methodological quality of research on ARS to obtain more robust evidence and to confirm their effects on learning and motivation in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Technology in higher education

In 2010, the first iPad was released in the United States, marking the beginning of a decade characterized by the introduction of tablets into the educational field. Steve Jobs was convinced that technology would transform education and change the learning process, making it more dynamic and interactive (Isaacson, 2011). Bill Gates, with some nuances, agreed with this idea: global education would be substantially improved through access to educational software platforms and high-quality, low-cost content and resources (Gates, 2010). In higher education, it is now impossible to imagine a classroom without some type of technological tool or equipment. Universities are destined to use technologies that facilitate the teaching-learning process. However, they must take responsibility for developing evidence-based education where digital tools truly foster meaningful learning and deep understanding, ensuring that their introduction into classrooms is not driven by trends or fashionable ideas.

More than a decade ago, some authors introduced the concept of Learning and Knowledge Technologies (LKT) to emphasize the educational aspect that technological tools can provide, both for students and teachers, particularly focusing on the learning methodology (Granados-Romero et al., 2014). For Lozano (2011), ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) become LKT when the potential of technology is endowed with a clear educational meaning, thus achieving more effective learning. It is, therefore, about “knowing and exploring the possible educational uses that ICT can have for learning and teaching” (p. 46). Some of these uses refer to accessing any information at any time, communicating with other students and/or personalizing education (Márques, 2012).

The impact that LKT has on education and learning has been enhanced by what is known as mobile learning (M-learning or ML). Mobile learning refers to learning that occurs through the mediation of mobile devices (Aznar-Díaz et al., 2019), taking into account its two main characteristics: first, ubiquity, which means that any content can be accessed anywhere and at any time, and second, multiplicity, which refers to the vast amount of digital resources and educational applications that students can use from their own devices (Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2021).

A historic event that further strengthened the relationship between education and technology was the lockdown that populations experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This event had a significant impact not only on school education but also on higher education, as it forced a shift from in-person teaching in classrooms to a sudden virtual environment (Taboada, 2023). Universities had to redesign, in record time, the schedules, spaces, and learning processes (Bhagat, Kim (2020)), making a great effort to offer students a hybrid teaching system that allowed them to continue their academic activities during this extraordinary situation.

In the Community of Madrid (Spain), a study on best teaching practices was conducted across 230 university degree programs, interviewing 350 teachers and 260 students from all Madrid universities during the 2020/21 academic year (Fundación para el conocimiento madri+d (2021)). The conclusions are grouped into three areas: (1) Learning strategies; an increased use of active and collaborative methodologies, such as flipped classrooms, was observed, which fostered student participation. (2) Digital competencies; there was consensus on the need to continue training teachers to improve their ability to apply interactive methodologies and conduct online assessments. (3) Assessment methods; the importance of formative assessment was emphasized, focusing on the acquisition of competencies and the use of emerging digital tools.

In this context, a specific family of mobile-based tools has gained ground in university classrooms: Audience Response Systems (ARS). ARS enable real-time interaction and large-scale response collection, and they are now widely applied across disciplines. This review focuses on ARS as a verifiable instantiation of technology-enhanced pedagogy in higher education.

Audience Response Systems (ARS)

These systems are defined as applications or programs that allow the teacher to receive real-time, immediate feedback in the classroom on a posed question (Loukia & Weinstein, 2024). Such digital tools can be used to gather opinions, assess prior knowledge, or evaluate students’ learning level in real-time by utilizing an application easily accessible from a computer or mobile device. Students respond anonymously and synchronously, either individually or in groups, and the answers are projected onto the classroom screen for everyone to see. In contemporary higher education, audience response systems are commonly used to enhance student participation and engagement; widely used digital applications that function as ARS include Kahoot!, Socrative, Mentimeter, and Wooclap (Wang & Tahir, 2020; Pichardo et al., 2021; Moreno-Medina et al., 2023).

Although in this paper we refer to these applications as ARS, the scientific literature includes various terms to describe them, such as student response systems, audience response systems, personal response systems, classroom response systems, electronic feedback systems, immediate response systems, classroom communication systems, and classroom performance systems. However, instead of converging toward a unified concept, Jurado-Castro et al. (2023), in their recent systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic, coined a new term for ARS: Real-time Classroom Interactive Competition (RCIC). These authors directly connect their proposal of “real-time classroom interactive competition” with game-based learning and mobile learning.

Several decades ago, a system for anonymous and remote interaction known as the clicker became popular (Richardson et al., (2015)), and it was quickly incorporated into educational contexts to support the teaching-learning process (Caldwell, 2007). This device sparked interest in the teaching community, leading to various systematic reviews on the use of clickers in the classroom (MacArthur & Jones, 2008; Kay & LeSage, 2009; Keough, 2012). For instance, Fies and Marshall (2006) reviewed publications to determine whether learning was more effective in traditional teaching environments or those using ARS in the classroom. Although they found that the latter provided more advantages for learning, only two of the reviewed studies included a control group, and most of them collected data through satisfaction surveys without specifying other variables to analyze. They concluded that “it is impossible to assess the effectiveness of the technology itself” (p. 106).

Similarly, Hunsu et al. (2016), in their meta-analysis, examined 111 effect sizes from 53 studies involving more than 26,000 participants, concluding that “only a tiny effect of the clicker was observed on cognitive learning outcomes” (p. 116). They found that only 20% of the analyzed studies conducted pre-test measures, and only 10% of the selected studies randomized their sample.

Among the most well-known current digital applications that can be used as ARS are Kahoot!, Socrative, Mentimeter, and Wooclap. Socrative, which appeared in 2010, allows teachers to load an online questionnaire and then use it with students (see Table 1 for further details). As students respond to the questions, the system provides explanations about the questions. Fraile et al. (2021) studied how Socrative can be a valuable tool for formative assessment while also promoting self-regulated learning. Other research focused on Socrative shows apparent positive results in some psychoeducational variables, though the findings are not conclusive or generalizable (Llamas & De la Viuda, 2022).

Mentimeter was launched in 2014, and very few studies have explored its potential benefits in higher education learning. Scopus only yields around 50 articles between 2013 and June 2024 that include the term Mentimeter in their title, abstract, or keywords. One of the most recent studies (Mohin et al., 2022) concludes that it is “a powerful and flexible tool that holds the solution to improving learning and teaching in large classrooms” (p. 56). However, their research collects data from an ad hoc satisfaction survey, with responses from only 25 volunteers out of the 262 students who participated in the study. Similarly, Pichardo et al. (2021) consider Mentimeter an optimal resource for both online and in-person teaching, promoting student attention and participation, although these authors do not offer any statistical or qualitative analysis of the collected data.

Undoubtedly, the ARS that has generated the most studies is Kahoot!. It is the only application that has been the subject of three systematic reviews or meta-analyses in the last five years (Zhang & Yu, 2021; Donkin & Rasmussen, 2021; Wang & Tahir, 2020). Despite Kahoot!‘s widespread use in education, Jurado-Castro et al. (2023), in their systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 studies on RCIC, express that more research is needed to study the effect of ARS on learning, as there is no consensus on their benefits and “specific and objective reviews” are still needed (p. 3).

Finally, Wooclap is the ARS with the least history, as it entered the digital market in 2016. Wooclap has an evident educational focus and clear potential in the teaching and learning field. This is evidenced by the amount of content and resources on its website related to neuroeducation, meaningful learning, active methodologies, and peer learning. Some authors highlight the effectiveness of Wooclap in improving learning, comprehension, and participation in comparison with traditional classes (Grzych & Schraen-Maschke, 2019), as well as its influence on enhancing the performance and motivation of undergraduate students (Moreno-Medina et al., 2023). However, these studies only use satisfaction surveys to collect data and lack control groups.

Considering the empirical background described above, a brief theoretical framing can help explain how audience response systems (ARS) affect motivation and learning. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness underpins high-quality motivation; common ARS affordances—autonomous participation, immediate performance feedback, and structured peer interaction—can support these needs and thereby foster participation and persistence (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) explains how task and interface design affect learning: signaling, segmentation, and timely feedback can reduce extraneous load, whereas poorly integrated on-screen elements may split attention and hinder schema construction (Sweller, 1988). This theoretical framing guides the interpretation of the existing evidence and the selection of the psychoeducational variables examined in this review.

Objective and research questions

In conclusion, a rigorous evaluation of the potential benefits of using ARS in higher education remains necessary. The present review aims to analyze empirical studies that meet clear criteria for methodological quality and focus on this objective. Consistent with this, Table 2 synthesizes findings from prior systematic reviews on the effectiveness of ARS in learning and underscores the current evidence gap: more studies and more specific analyses are required to determine the actual impact of these applications on learning. Accordingly, this review extends prior syntheses by (i) applying PRISMA-aligned methods and predefined quality thresholds; (ii) analyzing only concrete ARS applications within a unified framework (Kahoot!, Socrative, Mentimeter, Wooclap); and (iii) focusing on the methodological quality of the included studies.

It is therefore important to know what kind of methodology has been used in ARS research, how learning variables are analyzed, and whether a real effect can be observed on these variables. In this review, the concept of “learning improvement” refers to measurable positive changes in variables such as academic performance, motivation, student engagement, or classroom participation, as reported in pre-post comparisons or between-group differences (experimental vs. control). This leads to a literature review with the general objective of verifying the level of scientific evidence on the impact of ARS use on student learning and motivation in higher education. This objective is operationalized into the following research questions:

-

RQ1: What is the methodological quality of research designs on ARS?

-

RQ2: What are the psychoeducational variables investigated when using ARS?

-

RQ3: What effect does the use of audience response systems (ARS) have on student learning outcomes in higher education, regardless of discipline or class size?

Method

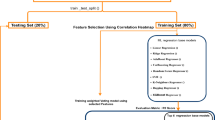

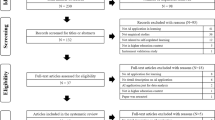

PRISMA 2020 reporting guidance for systematic searches was followed (Page et al., 2021), together with best-practice recommendations for transparent search reporting (Moher et al., 2015; Cooper, 2010). Searches were conducted across multiple sessions during February 2024; records and counts reflect the state of each database as of 29 February 2024 (end-of-month cutoff). Searches were run in Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate; indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESCI), Scopus (Elsevier), and ERIC (U.S. Department of Education). Identical limits were applied across platforms: publication years 2018–2024, languages English/Spanish, and journal articles only. To ensure replicability, explicit Boolean grouping and field qualifiers were used as follows (see Table 3):

It was decided to search for the specific names of the ARS tools that would be the focus of the study due to their high frequency of use (“kahoot*“ OR “Wooclap” OR “mentimeter” OR “socrative”). This approach was taken to increase search precision instead of targeting digital tools in general. The exclamation mark at the end of Kahoot! was replaced by an asterisk.

To select the variables for analysis, synonyms and commonly used terms in the literature were checked using the UNESCO Thesaurus (“motivation” OR “outcomes of education” OR “classroom climate” OR “learner engagement” OR “learn*“ OR “participation” OR “feedback”).

To evaluate whether ARS use is associated with differences in learning and motivation under comparable conditions, inclusion was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles reporting inferential statistical analyses (beyond descriptive summaries) and employing a control/comparison group; studies lacking these elements were excluded at eligibility. The educational level was limited to higher education, and purely e-learning contexts were excluded to avoid mixing environments with distinct interaction patterns. These design choices align with the stated research questions and with best-practice guidance for transparent, reproducible syntheses (see Table 4).

Kahoot! is the most widely used audience response application in university classrooms and the one that has been most extensively researched (Jurado-Castro et al., 2023). When analyzing the results provided by Scopus specifically on Kahoot!, a significant increase in publications starting in 2018 is observed. The number of documents found rose from 17 in 2017 to 54 in 2018. A similar pattern is seen in Web of Science, where the number of documents increased from 38 in 2017 to 86 in 2018. Therefore, we consider 2018 to be a turning point in studies on ARS. Additionally, we followed the criterion of Wood and Shirazi (2020), who state in their systematic review that after 2018, research tends to exhibit better methodological quality.

Non–peer-reviewed grey literature sources (e.g., theses, reports, preprints) were not searched, and expert consultation was not conducted. In addition to database searches, a targeted handsearch of peer-reviewed journals in educational technology—The Internet and Higher Education; Computers in the Schools; Computers & Education; Journal of Computers in Education; Educational Technology Research & Development; International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education; and Research in Learning Technology—was undertaken, applying the same limits and eligibility criteria as in WoS, Scopus, and ERIC. This step yielded four additional records; three were excluded at eligibility for prespecified reasons, and one study met all criteria and was included. Specifically, Cameron and Bizo (2019) did not use a control group; Mayhew et al. (2020) did not report inferential statistical analyses; and Anggoro and Pratiwi (2023) examined an ARS that was not among the four applications of interest for this review. In Computers & Education, one article meeting all inclusion criteria was identified (Orhan & Gursoy, 2019). These counts are reflected in the PRISMA flow diagram.

A total of 653 records were identified through databases (Web of Science=346; Scopus=285; ERIC = 22). Prior to screening, 518 records were removed (198 duplicates; 320 ineligible by automation tools), leaving 135 records for title/abstract screening. Seventy-nine records were excluded with predefined reasons (systematic reviews/meta-analyses; ARS not specified as the focal tool; ARS not central to the study; e-learning context; pre-university samples; non-student participants; topic misalignment). Fifty-six full texts were assessed for eligibility, of which 46 reports were excluded because the statistical analysis was unspecified or descriptive-only. Targeted journal handsearching yielded 4 additional records; 3 were excluded at eligibility and 1 was included. In total, 11 studies were included in the review. Counts correspond to Fig. 1 and reflect database status as of 29 February 2024.

Finally, to provide a measure of the scientific quality of the publications, after evaluating the journals in which the selected articles were published, it was found that none of them are indexed in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) database of Web of Science. However, 7 of these articles are indexed in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SJR) of Scopus. Table 5 provides detailed information on the quartiles and the impact factor associated with the highest quartile.

Results

Table 6 provides a detailed summary of the 11 articles extracted after the systematic review process. The collected data includes information on the authors, year of publication, sample size, implemented ARS application, measurement instruments, data analysis, results, and study variables. Of the reviewed articles, 9 focus on assessing the effectiveness of Kahoot!, one on Socrative, one on Mentimeter, and none were found on Wooclap.

Across included studies, the “control” condition was operationalized as instruction without an ARS, typically relying on standard didactic activities, textbook/worksheets or paper-and-pencil quizzes. In a within-cohort, session-level design, “control sessions” were those in which no Kahoot! quiz was administered, whereas in a three-arm design at least one non-ARS comparator (e.g., written report or video) functioned as the control.

RQ1: What is the methodological quality of research designs on ARS?

Firstly, there is significant heterogeneity in sample sizes, ranging from 40 to 274 participants, with most studies involving samples of fewer than 70 participants. Typically, participants are divided into two conditions: an experimental group using an ARS application and a control group that does not use it. Only one study (Andrés et al., 2023) includes a third condition, where participants follow a methodology based on video visualization. In four articles, group assignment was done by convenience sampling, four others do not report the sampling method, and only three employed random assignment.

Secondly, regarding the measurement instruments used, studies focused on language learning or specific medical content measure performance in various ways. These include tests on grammar, vocabulary, writing skills, oral communication, or specific knowledge, often created ad hoc by the authors. Only two articles utilized adapted versions of international language tests like TOEIC or IELTS. In the case of team skills, these are measured using the VALUE rubric developed by the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Similarly, studies that measure students’ perceptions often design ad hoc questionnaires or surveys specifically for the research, with only a few adapting instruments from other authors.

Thirdly, while all the articles report having a time measurement (pre-post) and a condition or group (experimental vs. control), only three studies employ analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for main effects and interactions between these factors. In the remaining articles, mean comparisons are performed only within time (pre-post) for each group separately, or score comparisons are made between groups only in the pre-test or post-test phases.

RQ2: What are the psychoeducational variables investigated when using ARS?

Of the 11 articles analyzed, seven focus on testing the effectiveness of ARS applications, comparing an experimental or treatment group using the application with a control group that does not, specifically in language learning. Two studies focus on improving knowledge in specific subjects within the medical field, such as pathology, one article examines the enhancement of team skills, and another investigates student performance and participation in a research methodology course. In the studies focused on language learning or specific medical content, the variable of interest is operationalized as “performance.”

Additionally, some studies set objectives aimed at descriptively measuring, only in the experimental group, perception variables related to motivation toward the use of Kahoot!, enjoyment, engagement, utility for learning, ease of use, autonomy, self-regulation, or participation. A synthesis figure plots psychoeducational variables against ARS types (Fig. 2). Each cell encodes the overall direction of effect observed across the included studies: ↑ positive; ↔ null; ◐ mixed/inconclusive; ↓ negative; — no data. No eligible study evaluated Wooclap, hence all Wooclap cells are marked with —.

Beyond the variables described, two common patterns emerge. First, there is a lack of explicit theoretical grounding in established frameworks—such as Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) or Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988)—to guide hypothesis formulation and justify the selection of variables. Second, ad hoc instruments predominate for measuring constructs such as motivation or engagement. Internal consistency is often reported (Cronbach’s alpha), but standardized scales are rarely employed. There are few exceptions, such as the Student Engagement Scale or the VALUE rubric for teamwork. Taken together, heterogeneity in how variables are conceptualized and the weak theoretical basis of data-collection instruments reduce comparability across studies and hinder a deeper understanding of the psychoeducational variables analyzed.

RQ3: What effect does the use of audience response systems (ARS) have on student learning outcomes in higher education, regardless of discipline or class size?

Regarding the effectiveness of ARS applications, six articles did not find significant differences between the two conditions (experimental and control), while four reported some improvements in post-test scores favoring the experimental group, and one found improvements only in the experimental group using Kahoot! but not in the group using Quizizz. These improvements were observed in enhanced oral communication or pronunciation skills, increased knowledge in specific subjects like pathology or medical pharmacology, or overall performance gains.

Upon closer examination of these findings, Yürük’s (2020) study found that the group using Kahoot! showed greater pronunciation skills in the post-test compared to the control group. In Kim & Cha’s (2019) research, the experimental group using Socrative also scored higher in oral skills compared to the control, with participants also reporting improved confidence and interest in learning.

Focusing on studies aimed at increasing knowledge in specific subjects, Elkhamisy & Wassef (2021) found that students who practiced using Kahoot! during sessions scored better on pathology tests than those who did not. Similarly, Kamel & Shawwa (2021) found that knowledge of pharmacology was greater in sessions where students used Kahoot!, compared to the control group. However, in this study, the test used to compare performance between groups included the same questions that had been tested in the Kahoot! application, meaning that the effect of learning or test recall was not controlled for.

Discussion and conclusions

The main objective of this systematic review on Audience Response Systems (ARS) in higher education was to evaluate the quality of the available scientific evidence regarding their impact on student learning. Based on the work conducted, several conclusions can be drawn.

With respect to RQ1 (methodological landscape), the evidence base has expanded but remains methodologically uneven. It is evident that in recent years there has been an increase in the number of studies investigating the use of ARS in classrooms to assess the potential impact of these applications in higher education (Kocak, 2022). However, it should be noted that most studies lack a solid methodological framework that would allow the development of a well-organized body of knowledge on the impact of ARS on learning, or on variables such as motivation, classroom climate, or performance. Only 11 of the 653 initially found articles employ rigorous research methodologies. Accordingly, interpreting observed outcomes requires caution given the constraints of the underlying designs. In this context, several design features limit the strength of inferences about ARS effects.

Regarding RQ2 (psychoeducational variables investigated), most studies prioritize indicators of motivation and engagement over conceptual learning and retention. It should also be highlighted that a large proportion of the reviewed studies emphasize variables such as motivation, engagement, or student interest, while less attention is paid to conceptual learning or long-term understanding. As emphasized by Alam et al. (2025), technology-mediated classroom interaction can only foster deep learning when instructional design explicitly targets conceptual change and durable knowledge. Therefore, future ARS research should not only measure short-term perceptions but also include validated instruments and longitudinal designs that allow the evaluation of conceptual gains and knowledge retention.

Turning to RQ3 (effects on learning outcomes), the findings are mixed. Some studies suggest significant improvement in the experimental group before and after the intervention in variables such as motivation (Madiseh et al., 2023) or participation and engagement (Orhan & Gursoy, 2019). While this is a positive indicator, the reality is that most research lacks a control group to compare results, does not use standardized instruments, and does not conduct conclusive statistical analyses (Donkin & Rasmussen, 2021). Consequently, it can be concluded that the methodological designs of ARS research in higher education tend to be simplistic and are generally limited to comparing means using descriptive statistics, with a widespread absence of rigorous designs. It can therefore be stated that short-term improvements in motivation/participation are more consistent than long-term improvements in performance, which remain inconclusive.

These observations are consistent with prior reviews that report mixed or modest effects and call for stronger designs. From this systematic review, we can conclude that our results are consistent with the findings of previous reviews. Jurado-Castro et al. (2023) state that there is no consensus on how ARS contribute to academic performance and that there is currently a debate about the impact of these tools, despite their popularity in classrooms. Kocak (2022) concludes that contradictory results exist in the literature regarding the effectiveness of ARS and that further research is needed. Zhang & Yu (2021) highlight that some studies show no improvements in learning outcomes. Donkin and Rasmussen (2021) point out that all analyzed studies use perception questionnaires to measure the impact of ARS, and none evaluate long-term outcomes. Wood & Shirazi (2020) argue that ARS are not effective as mere question-and-answer tools. Wang & Tahir (2020) find that while the use of Kahoot! generates favorable perceptions among students and teachers about its positive effects on various variables, empirical studies are needed to confirm its impact on learning. Finally, Hussain & Wilby (2019) note that most studies on ARS lack proper controls and that their impact is only marginally positive.

Beyond the specific responses to the research questions posed, we found other aspects. First, the pedagogical co-interventions accompanying ARS may influence the observed effects. Another point to emphasize in the methodological design is that, when ARS are employed alongside other pedagogical activities, these interactions can affect outcomes. Co-interventions such as flipped classroom structures, video-supported tasks, or mandatory group work may interact with ARS and influence the observed results; evidence from multi-component designs suggests that they can enhance learning (Roman et al., 2025). However, in the included studies, co-interventions were seldom specified with sufficient detail, which prevented meaningful comparative analyses of their independent contribution; consequently, effects are interpreted cautiously and are attributed primarily to the presence or absence of ARS. Future evaluations should pre-register and explicitly report co-interventions to enable moderation analyses and clearer causal attribution.

Second, at the platform level, usage patterns are not uniform; Kahoot! stands out, predominating and differing due to its game-based learning features. Kahoot! is, without doubt, the most widely used ARS in higher education classrooms and the one with the most research devoted to it. This is not a superficial aspect, since, compared to Mentimeter, Wooclap, or Socrative, Kahoot! is the only application based on Game-Based Learning (Wang & Tahir, 2020). Some publications directly link the concept of games to ARS, referring to them as Game-Based Student Response Systems (GSRSs) (Licorish & Lötter, 2022), when in reality this label only applies to Kahoot!, without considering that many other audience response applications lack the competitive component characteristic of Kahoot!. Moreover, some evidence suggests that certain gamification elements (e.g., points, leaderboards, badges, immediate feedback) may enhance the satisfaction of psychological needs —autonomy, competence, and relatedness—, which is particularly relevant given Kahoot!’s game-based design (Sailer et al., 2017).

And third, technology acceptance frameworks help explain the widespread adoption of ARS regardless of their demonstrated impact on learning. One possible explanation for why Kahoot! is the most widely used application compared to others can be found in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), developed by Davis (1989). This model seeks to explain the factors influencing technology use, concluding that two determining variables exist: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Yong et al., 2010). The model can even predict teachers’ use of technology, considering whether it is perceived as useful and easy to implement in a classroom setting (Abundis & Hinojosa (2023)). This could explain why ARS applications are so widely used in university teaching, possibly more due to their ease of use than to evidence-based education. Complementarily, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) posits that intention and use are driven by performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions, offering a framework to interpret the widespread uptake of ARS in higher education (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Taken together, these models suggest that the broad diffusion of ARS may be driven as much by perceived usefulness, ease of use, and the context of application.

Taken together, these results outline where ARS show potential and where stronger evidence is still needed, setting the stage for the methodological limitations discussed next.

Limitations and prospective

Conducting this systematic review revealed several methodological limitations that shaped the inferences drawn when synthesizing the current corpus on ARS.

First, statistical power is a widespread limitation. The power of many selected studies is low, as several report small sample sizes—some with fewer than 50 participants—which reduces the ability to detect statistically significant effects even when real differences exist. In low-power studies, the probability of committing a Type II error (false negative) increases, which could partly explain why some results fail to show significant effects despite potentially relevant improvements in learning or motivation. This limitation underscores the need to interpret null findings with caution and reinforces the advisability of including larger and more representative samples in future studies to ensure reliable and generalizable conclusions.

Second, longitudinal evidence is virtually absent. In the reviewed studies, no evaluation is conducted to determine whether the observed improvements are sustained over time: all measurements are taken immediately after the intervention, without delayed post-tests or follow-ups. This short-term perspective restricts the assessment of knowledge retention or sustained motivation derived from ARS use. As noted by Hunsu et al. (2024), longitudinal follow-up is essential to determine whether student response systems generate lasting learning gains rather than merely temporary increases in performance. Future research should prioritize extended evaluation horizons to move beyond the immediate post-test and better understand the sustained impact of ARS in higher education.

Third, teacher-related variability is rarely modeled. Tools such as Kahoot! or Mentimeter require not only technical familiarity but also pedagogical adaptation and real-time facilitation skills. It is plausible that part of the observed improvements are influenced—at least partially—by the enthusiasm, creativity, or prior experience of the instructor with digital tools rather than by the ARS platform itself. Very few studies attempt to isolate the specific contribution of ARS from the instructional behavior accompanying its use. As highlighted by previous research (Achuthan et al., (2014)), teacher receptivity and creative implementation, along with institutional infrastructure and digital preparedness, are key factors for successfully integrating educational technologies. Future studies should account for these contextual elements through instructor-level variables, mixed-methods approaches, or controlled comparisons across multiple instructors.

Fourth, subgroup analyses relevant to equity are scarcely reported. Most publications do not examine whether outcomes differ according to student characteristics such as gender or prior academic performance. This omission limits understanding of whether ARS are equally effective across diverse populations. Given the importance of educational equity, it is necessary to examine differential effects to determine whether ARS use benefits all students equally or whether specific subgroups require tailored strategies or additional support.

Fifth, inconsistent reporting of group size prevents planned moderation testing. In the included studies, class size was recorded irregularly, and when available, categorized as small ( ≤ 30), medium (31–60), or large ( > 60). Most group comparisons were conducted in small classes ( ≈ 19–30 students per arm), with fewer cases in medium-sized classes ( ≈ 55 per arm) and cohort-level implementations (N ≈ 255–274). Since section-level group size was not reported consistently, moderation analyses could not be conducted. Therefore, class size should be considered an a priori design priority and a factor in power planning for future ARS trials.

Beyond design, measurement practices also limit comparability. Most studies collect data through perception surveys or satisfaction questionnaires (Donkin & Rasmussen, 2021) or use ad hoc instruments created by instructors or researchers. However, standardized and validated instruments exist to measure the most common variables in this line of research. For example, classroom climate can be measured with the Classroom Motivational Climate Questionnaire (CMCQ, Tapia & Heredia, 2008), the Motivational Orientation and Climate Scale (MOC, Stornes et al., (2011)), the Patterns of Adaptive Learning (Midgley et al., 2000), or the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-University Form (Schaufeli et al., 2002). To objectively assess academic engagement, the questionnaire developed by Alonso-Tapia et al., (2017) can be used. When an instrument is administered in the same language and within a comparable higher education population, cultural adaptation is not required beyond documenting format/administration changes; if used in another language or context, or if items are modified, recommended procedures include forward translation, reconciliation, back-translation, expert review of conceptual equivalence, and cognitive pretesting, followed by confirmation of factorial structure and—when comparisons are planned—tests of measurement invariance (Wild et al., 2005). Future ARS research should prioritize validated measures with explicit evidence of reliability and dimensionality and document adaptation processes when instruments are translated or modified.

In line with the above, the timing of assessment and analytical decisions also deserve attention. To distinguish short-term recall from long-term learning, outcome evaluation should include both an immediate post-test and a delayed post-test approximately 2–4 weeks later (Roediger & Butler, 2011). Designs should ensure baseline equivalence (e.g., pretest measures) and apply analyses that account for it (e.g., ANCOVA or mixed models). Reports should include effect sizes and confidence intervals to facilitate comparison across studies.

Finally, publication channel impact and terminological heterogeneity add complexity to synthesis. Most articles appear in medium-impact journals, with few studies published in top-quartile education or technology outlets; furthermore, the wide variety of terms used to label and conceptualize ARS generates heterogeneous definitions of these student response applications.

Taken together, these limitations contextualize the preceding findings and justify the research priorities to be addressed in future.

Looking ahead to future research, the priority is clear: conduct studies with robust methodologies that enable statistical analyses with control groups and, in addition, employ validated and standardized data-collection instruments beyond perception or satisfaction surveys. It is also advisable to broaden the scope to a wider range of audience response applications—not only Kahoot!—to understand their differences and similarities and how they relate to learning.

Moreover, although this review focuses on pedagogical outcomes, the economic and infrastructural feasibility of ARS tools is a key factor in their adoption. Issues such as licensing costs, device availability, internet connectivity, and classroom conditions constrain the scalability and sustainability of their use in different educational contexts. As Achuthan, Murali (2015) note, educational technologies should be evaluated not only for their learning impact but also for their cost-effectiveness and implementation feasibility; these practical considerations deserve greater attention in future research and policy planning.

Based on the findings and limitations identified, the following methodological and thematic priorities are proposed to guide research on ARS in education:

-

Conduct longitudinal studies to evaluate the long-term impact of ARS on academic performance, knowledge retention, and student motivation.

-

Broaden outcome variables to include engagement, active participation, and long-term retention, beyond short-term perceptions or scores.

-

Increase sample sizes and ensure diversity in participant characteristics to improve generalizability and statistical power.

-

Investigate differential effects of ARS across student subgroups (e.g., gender, prior academic performance, learning styles) to support inclusive and equitable practices.

-

Examine the instructor’s role as a moderating factor (pedagogical adaptation, digital competence, facilitation style, receptivity to educational technology).

-

Compare ARS platforms (e.g., Kahoot!, Mentimeter, Socrative) in terms of usability, engagement, and effectiveness to inform instructional design.

-

Consider the economic and infrastructural feasibility of implementation (cost, connectivity, scalability), especially in resource-limited settings.

These priorities can be addressed through experimental or quasi-experimental designs with control groups, validated instruments, and longitudinal follow-up. Incorporating preregistration, the reporting of effect sizes and confidence intervals, and analyses that adjust for baseline (e.g., ANCOVA or mixed-effects models) will help build a more comprehensive, realistic, and evidence-based understanding of how ARS function across diverse educational contexts.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abundis VM, Hinojosa JI (2023) Evaluación de la aplicación Microsoft Teams mediante el Modelo de Aceptación Tecnológica (TAM). TLATEMOANI Rev. Acad.émica de. Investigación 44:86–99

Achuthan K, Murali SS (2015) A Comparative Study of Educational Laboratories from Cost & Learning Effectiveness Perspective. In Silhavy R, Senkerik R Oplatkova Z, Prokopova Z, Silhavy P (eds), Software Engineering in Intelligent Systems. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (vol 349). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18473-9_15

Achuthan K, Sivan S, Raman, R (2014) Teacher receptivity in creative use of virtual laboratories. In 2014 IEEE Region 10 Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10 HTC) (pp. 29–34). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/R10-HTC.2014.7026321

Alam TM, Stoica GA, Özgöbek Ö (2025) Asking the classroom with technology: a systematic literature review. Smart Learn. Environ. 12(7):1–49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00348-z

Ali R, Abdalgane M (2022) The impact of gamification “Kahoot App” in teaching English for academic purposes. World J. Engl. Lang. 12(7):18–25. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v12n7p18

Alonso-Tapia J, Nieto C, Merino-Tejedor E, Huertas J, Ruiz M (2017) Assessment of learning goals in university students from the perspective of ‘person-situation interaction’: the Situated Goals Questionnaire (SGQ-U). Estudios de. Psicol.ía 39(1):1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02109395.2017.1412707

Andrés, C, Ortiz, X, Olivares, JP, Vidal, R, Cámara, HF, Teuber, V (2023) Development of teamwork skills using ICTs in undergraduate students of food industry engineering degree. Int. J. Eng. Pedagogy, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v13i4.36971

Anggoro KJ, Pratiwi DI (2023) University students’ perceptions of interactive response system in an English language course: a case of Pear Deck. Res. Learn. Technol. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v31.2944

Aznar-Díaz I, Cáceres MP, Trujillo JM, Romero-Rodríguez JM (2019) Mobile learning y tecnologías móviles emergentes en Educación Infantil: percepciones de los maestros en formación. Rev. Espacios 40(5):14

Bhagat S, Kim D (2020) Higher Education Amidst COVID-19: Challenges and Silver Lining. Inf. Syst. Manag. 37(4):366–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100059

Caldwell JE (2007) Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best-practice tips. Life Sci. Educ. 6(1):9e20. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.06-12-0205

Cameron KE, Bizo LA (2019) Use of the game-based learning platform KAHOOT! to facilitate learner engagement in Animal Science students. Res. Learn. Technol. 27. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v27.2225

Cárdenas-Moncada C, Véliz-Campos M, Zurita-Beltrán E (2020) The effect of Kahoot! on the motivation and engagement of Chilean vocational higher-education EFL students. Computer-Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 21(1):64–78

Cooper, H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach (4th ed.). Sage

Davis F (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of information technology. MISQuarterly 73(3):319–340

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychologist 55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Donkin R, Rasmussen R (2021) Student Perception and the Effectiveness of Kahoot!: A Scoping Review in Histology, Anatomy, and Medical Education. Anat. Sci. Educ. 14(5):572–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2094

Elkhamisy FAA, Wassef RM (2021) Innovating pathology learning via Kahoot! game-based tool: a quantitative study of students’ perceptions and academic performance. Alex. J. Med. 57(1):215–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/20905068.2021.1954413

Fies C, Marshall J (2006) Classroom response systems: a review of the literature. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 15(1):100–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-006-0360-1

Fraile J, Ruiz-Bravo P, Zamorano-Sande D, Orgaz-Rincón D (2021) Evaluación formativa, autorregulación, feedback y herramientas digitales: uso de Socrative en educación superior. Retos 42:724–734. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v42i0.87067

Fundación para el conocimiento madri+d (2021). Informe de buenas prácticas docentes en periodo COVID-19. Recuperado de: https://www.madrimasd.org/calidad-universitaria/publicaciones/informe-buenas-practicas-docentes-en-periodo-covid-19

Gates, B (2010). Education and the potential of tablets. Forbes

Granados-Romero J, López-Fernández R, Avello-Martínez R, Luna-Álvarez D, Luna-Álvarez E, Luna-Álvarez W (2014) Las tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones, las del aprendizaje y del conocimiento y las tecnologías para el empoderamiento y la participación como instrumentos de apoyo al docente de la universidad del siglo XXI. Medisur 12(1):289–294

Grzych G, Schraen-Maschke S (2019) Interactive pedagogic tools: evaluation of three assessment systems in medical education. Annales de. Biologie Clin. 77(4):429–435. https://doi.org/10.1684/abc.2019.1464

Herrada RI, Baños R, Alcayde A (2020) Student Response Systems: A Multidisciplinary Analysis Using Visual Analytics. Educ. Sci. 10(12):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120348

Hunsu NJ, Adesope O, Bayly DJ (2016) A meta-analysis of the effects of audience response systems (clicker-based technologies) on cognition and affect. Computers Educ. 94:102–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.013

Hunsu, N, Dunmoye, I, Feyijimi, T (2024) Clickers for effective learning and instruction: An examination of the effects of audience response systems in the classroom. In Technology for Effective Learning and Instruction (pp. 207–222). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003386131-20

Hussain FN, Wilby KJ (2019) A systematic review of audience response systems in pharmacy education. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 11(11):1196–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.07.004

Isaacson, W (2011) Steve Jobs. Simon & Schuster

Jurado-Castro JM, Vargas-Molina S, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Benítez-Porres J (2023) Effectiveness of real-time classroom interactive competition on academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9:e1310. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1310

Kapsalis GD, Galani A, Tzafea O (2020) Kahoot! as a formative assessment tool in foreign language learning: A case study in Greek as an L2. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 10(11):1343–1350. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1011.01

Kay RH, LeSage A (2009) Examining the benefits and challenges of using audience response systems: a review of the literature. Comput. Educ. 53(3):819–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.05.001

Keough SM (2012) Clickers in the classroom: a review and a replication. J. Manag. Educ. 36(6):822–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562912454808

Kim H-S, Cha Y (2019) Effects of using Socrative on speaking and listening performance of EFL university students. STEM. 20(2):109–134. https://doi.org/10.16875/stem.2019.20.2.109

Kocak O (2022) A systematic literature review of web-based student response systems: Advantages and challenges. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27(2):2771–2805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10732-8

Licorish SA, Lötter AL (2022) When Does Kahoot! Provide Most Value for Classroom Dynamics, Engagement, and Motivation?: IS Students’ and Lecturers’ Perceptions. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 33(3):245–260

Llamas CJ, De la Viuda A (2022) Socrative como herramienta de mejora del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en educación superior. RIED-Rev. Iberoam. de. Educación a Distancia 25(1):279–297. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.1.31182

Loukia D, Weinstein N (2024) Using technology to make learning fun: technology use is best made fun and challenging to optimize intrinsic motivation and engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39:1441–1463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00734-0

Lozano R (2011) De las TIC a las TAC: tecnologías del aprendizaje y del conocimiento. Anuario Think. EPI 5(1):45–47

MacArthur JR, Jones LL (2008) A review of literature reports of clickers applicable to college chemistry classrooms. Chem. Educ. Res Pr. 9(3):187–195. https://doi.org/10.1039/B812407H

Madiseh FR, Al-Abri A, Sobhanifar H (2023) Integrating Mentimeter to boost students’ motivation, autonomy, and achievement. Computer-Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 24(3):232–251

Marquès PR (2012) Impacto de las TIC en educación: funciones y limitaciones. 3ciencias 2(1):14–29

Mayhew E, Davies M, Millmore A, Thompson L, Pena Bizama A (2020) The impact of audience response platform Mentimeter on the student and staff learning experience. Res. Learn. Technol. 28. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v28.2397

Midgley, C, Maehr, M, Hruda, L, Anderman, E, Anderman, L, Freeman, K, Gheen, M, Kaplan, A, Kumar, R, Middleton, MJ, Nelson, J, Roeser, R, Urdan, T (2000) Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales. University of Michigan

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2015) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000097

Mohin M, Kunzwa L, Patel S (2022) Using Mentimeter to enhance learning and teaching in a large class. Int. J. Educ. Policy Res. Rev. 9(2):48–57. https://doi.org/10.15739/IJEPRR.22.005

Moreno-Medina M, Peñas-Garzón M, Belver C, Bedia J (2023) Wooclap for improving student achievement and motivation in the Chemical Engineering Degree. Educ. Chem. Eng. 45:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2023.07.003

Orhan D, Gursoy G (2019) Comparing success and engagement in gamified learning experiences via Kahoot and Quizizz. Comput. Educ. 135:15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.015

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pichardo JI, López-Medina EF, Mancha-Cáceres O, González-Enríquez I, Hernández-Melián A, Blázquez-Rodríguez M, Jiménez V, Logares M, Carabantes-Alarcon D, Ramos-Toro M (2021) Students and Teachers Using Mentimeter: Technological Innovation to Face the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Pandemic in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 11(11):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110667

Richardson AM, Dunn PK, McDonald C, Oprescu F (2015) Crisp: an instrument for assessing student perceptions of classroom response systems. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 24(4):432e447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-014-9528-2

Roediger III HL, Butler AC (2011) The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15(1):20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003

Roman C, Delgado MÁ, García-Morales M (2025) Embracing the efficient learning of complex distillation by enhancing flipped classroom with tech-assisted gamification. Educ. Chem. Eng. 50:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2024.11.001

Romero-Rodríguez JM, Aznar-Díaz I, Hinojo-Lucena FJ, Gómez-García G (2021) Uso de los dispositivos móviles en educación superior: relación con el rendimiento académico y la autorregulación del aprendizaje. Rev. Complut. de. Educación 32(3):327–335. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.70180

Sailer M, Hense JU, Mayr SK, Mandl H (2017) How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers Hum. Behav. 69:371–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033

Schaufeli WB, Martínez IM, Pinto AM, Salanova M, Bakker AB (2002) Burnout and Engagement in University Students: A Cross-National Study. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 33(5):464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003

Shawwa L, Kamel F (2023) Assessing the knowledge and perceptions of medical students after using Kahoot! in pharmacology practical sessions at King Abdulaziz University Jeddah. Cureus 15(3):e36796. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36796

Sianturi AD, Hung R-T (2023) A Comparison between Digital-Game-Based and Paper-Based Learning for EFL Undergraduate Students’ Vocabulary Learning. Eng. Proc. 38(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2023038078

Stornes EB, y, Bru E (2011) Perceived motivational climates and selfreported emotional and behavioural problems among Norwegian secondary school students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 32(4):425–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310397280

Sweller J (1988) Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 12(2):257–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Taboada MB (2023) Educación, tecnologías y agencias en tiempos de virtualidad forzada. magis, Rev. Internacional de. Investigación en. Educación 16:1–23. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m16.etat

Tapia JA, Heredia B (2008) Development and initial validation of the Classroom Motivational Climate Questionnaire (CMCQ). Psicothema 20(4):883–889

Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27(3):425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Wang AI, Tahir R (2020) The effect of using Kahoot! for learning: A literature review. Computers Educ. 149:103818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103818

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P (2005) Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures. Value Health 8(2):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x

Wood R, Shirazi S (2020) A systematic review of audience response systems for teaching and learning in higher education: the student experience Comput. Educ. 153:103896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103896

Yong LA, Rivas LA, Chaparro J (2010) Modelo de aceptación tecnológica (TAM): un estudio de la influencia de la cultura nacional y del perfil del usuario en el uso de las TIC. INNOVAR 20:197–204

Yürük N (2020) Using Kahoot as a skill improvement technique in pronunciation. J. Lang. Linguistic Stud. 16(1):137–153. https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.712669

Zhang Q, Yu Z (2021) A literature review on the influence of Kahoot! On learning outcomes, interaction, and collaboration. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26(4):4507–4535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10459-6

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Spanish State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science and Innovation under grant PID2022-138175NB-I00.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAHM conceptualized the study, coordinated the team, and performed the article screening. MGP analyzed the data, conducted the article screening, and drafted the results section. JSS conducted the database search, selected and screened the articles, and wrote the text. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required

Informed consent

Informed consent is not required

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Serrada-Sotil, J., Huertas Martínez, J.A. & Granado-Peinado, M. Do audience response systems truly enhance learning and motivation in higher education? A systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1767 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06042-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06042-w