Abstract

This study explores how superstition, specifically China’s “zodiac year” belief predicting bad luck, influences corporate charitable donations, addressing the unexplored psychological mechanism behind religion’s impact on CSR. Using a sample of Chinese listed firms from 2007 to 2022, we find that before their zodiac year, the chairperson tends to increase the firm’s charitable donations due to their anticipation of bad luck, which highlights the impact of managers’ nonstandard beliefs on CSR. This effect is more pronounced in regions with a strong Taoist atmosphere and within family firms. Mechanism tests indicate that the impact intensifies when firms underperform or face negative media coverage, reflecting heightened insecurity. Additionally, chairpersons tend to engage in quiet giving and purchase extra insurance before their zodiac year, highlighting self-enhancement and self-protection motivations. Our findings reveal a mechanism of egoistic motivation behind CSR, that is, executives make donations for personal psychic gratification for themselves. This study contributes to the research on both religion and motivation of charitable donations by providing a novel perspective to explain the motivation behind corporate charitable donations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As economic development progresses, enterprises face increasing pressure to address social issues through responsible practices. Many social challenges are rooted in distributional inequities (Luo and Kaul 2019). Corporate charitable donations help improve social relations, supports vulnerable groups, reduces wealth disparities, and promotes common prosperity, representing an important manifestation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Zhou and Liu 2024). In business ethics research, CSR remains a central and widely studied topic (Batlles de la Fuente and Abad Segura 2023). Thus, unpacking the black box of why companies engage in charitable donations has got continual attention in academia. Existing studies have discussed its economic, political, reputational, and altruistic motivations (e.g., Jiang et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016; Zhou and Liu 2024), which can be categorized into egoistic and altruistic motives (Zhou and Liu 2024). Specifically, most scholars paid attention to the egoistic motives in terms of explicit benefit, and found that firms engage in charitable donations to gain important resources, such as financial resource, reputation or legitimacy from stakeholders (e.g., Petrenko et al. 2016; Wang and Qian 2011). Some studies on altruistic motivation, developing from the perspective of psychological cognition, hold that firms engage in corporate charitable donations selflessly (Su 2019; Xu and Ma 2022). Although extant literature advances our understanding of motivation behind corporate charitable donations, it fails to thoroughly explore the egoistic motivations from the psychological perspective of decision makers.

Religious and cultural beliefs play a crucial role in shaping managers’ psychological biases and decision-making processes. Early work has acknowledged that managers’ personal traits and beliefs influence organizational outcomes (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). Building on this, researchers have emphasized factors such as ethical training, cultural background, and life experiences as important sources of psychological influence (Ma et al. 2020; Wood 1991). Particularly, as an important factor affecting people’s psychological well-being and cognition, the role of religion in promoting CSR is drawing scholars’ attention increasingly (Koburtay et al. 2023; Su 2019). Existing studies have predominantly centered on mainstream religious cultures, highlighting their educational role in fostering altruistic motivations of firms to “do good” (Su 2019; Xu and Ma 2022). However, this focus has often overlooked the pervasive influence of superstitions, a religious belief system that remains deeply ingrained in modern societies (Fisman et al. 2023), and neglected the self-interest mechanisms that may underlie the influence of religion.

Based on attribution theory, managers may attribute luck as a factor in the failure or success of corporate (Liu and de Rond 2016), and many managers consider superstition to be an important factor in the company’s strategic decisions, emphasizing the various roles that luck plays in the organization’s success (Brownell et al. 2024; Tsang 2004). To address this gap, we investigate “luck belief” associated with the zodiac year, which represents a unique Chinese superstition deeply rooted in Taoist folk tradition. This belief stems from the notion that individuals may offend the Grand Duke of Jupiter (tai sui in Chinese) during their zodiac birth year, incurring bad luck that recurs every 12 years (Li et al. 2021a). Given the regularity of the zodiac year, it strongly influences managers’ risk-taking, thereby reducing risky investments (Fisman et al. 2023; Hirshleifer et al. 2018). Built on prior research, we argue that the effects of the zodiac year superstition extend beyond the actual year, with managers taking preemptive actions to mitigate potential bad luck resulting from their zodiac year. Thus, we shift the focus from investment risk to corporate charitable donations, a key aspect of social responsibility with lower risk and a strong insurance effect (Li et al. 2021a). We posit that managers’ anticipation of bad luck during their zodiac year increases charitable donations as a strategy to secure good fortune or psychological insurance, reflecting egoistic motivations rooted in decision-makers’ psychology.

Numerous pieces of evidence suggest that executives facing their zodiac year may engage in preemptive philanthropic activities as a form of risk mitigation. Wang Shi, founder of Vanke (000002.SZ), whose office prominently featured tiger-themed artwork reflecting his zodiac sign, dramatically increased environmental and rural education donations in 2021—the year preceding his sixth zodiac year. Another notable example is Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba Group (BABA.N). In 2011—the year preceding his zodiac year, Alibaba Group and its subsidiaries jointly established the Alibaba Foundation, which was approved by the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China. Jack Ma became the first volunteer of the foundation. The foundation focuses on various public welfare projects, including poverty alleviation, education support, and environmental protection. These examples suggest that luck beliefs may systematically influence the timing and magnitude of corporate charitable donations.

To better understand the psychological motivations behind managers’ corporate charitable donations before their zodiac year, this study draws on established psychological theories of self-enhancement and self-protection (Alicke and Sedikides 2009). Self-enhancement theory proposes that individuals engage in prosocial behaviors to improve their self-image and derive psychological satisfaction. In the context of zodiac year superstition, managers may view charitable donations as a way to reinforce their identity as socially responsible and morally upright leaders. At the same time, self-protection theory suggests that individuals take preventative actions to guard against perceived threats or risks. Anticipating potential misfortunes during their zodiac year, managers might increase donations as a form of psychological insurance, aiming to mitigate bad luck and shield themselves from adverse outcomes. Integrating these theories offers a comprehensive framework that captures both the proactive pursuit of positive self-regard and the defensive efforts to avoid negative consequences in managers’ philanthropic decisions.

Based on a sample of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2007 to 2022, we focus on chairpersons’ zodiac year belief, given their pivotal decision-making role in Chinese firms (Fisman et al. 2023). Aligned with our prediction, our findings reveal an increase in charitable donations when chairpersons are nearing their zodiac year. This trend suggests that executives may engage in charitable donations to seek personal “luck” influenced by their nonstandard beliefs. Furthermore, we find that this relationship is strengthened for firms who are in regions with strong Taoist influence, which exerts considerable impact on managers’ zodiac year beliefs. The relationship is also prominent within family firms because of managers’ ability to engage in charitable donations. The mechanism test shows that when the enterprise’s performance is below aspiration and it is exposed to more negative news, that is, when the enterprise experiences greater insecurity, the promoting effect is more significant. At the same time, the chairpersons are more likely to make quiet giving and purchase insurance one year before zodiac year. This indicates that the executives’ charitable donations in the year before their zodiac year might be due to the self-enhancement and self-protection mechanisms to deal with risks.

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature. First, we bring a fresh perspective to CSR research by demonstrating an egoistic motivation behind CSR from the perspective of executives’ psychology, that is for accumulation of personal luck. This focus makes the study distinct from prior research emphasizing the influence of religion on altruism (Su 2019; Xu and Ma 2022). From a psychological perspective, we employed the theories of self-enhancement and self-protection to explore the motives behind the behavior of top executives, thereby expanding the scope of our research. Second, we reveal the general psychological mechanism by which the informal cultural belief of luck superstition influences the decision-making of executives. We found that managers’ perception of luck systematically alters their assessment of the value of enterprise activities, not only reducing risk preference, but also stimulating preventive strategic behaviors centered on accumulating moral capital and seeking psychological insurance. Apart from Asian countries like China, superstition concepts and behaviors are almost universally present in all human societies (Tsang 2004). Therefore, this mechanism has been verified in the context of Chinese zodiac superstition, but it is also applicable to other superstition systems in other cultures, such as numerical taboos, astrological predictions. Third, we highlight the importance of considering regional religious atmosphere and firm ownership in studying the impact of superstitions on corporate decisions. We also emphasize the contextual factors that enable superstition to exert its influence.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Executives’ cognition and firm’s CSR

Upper echelons theory holds that firms’ organizational decisions can be driven by the values and cognitive bases of their top managers (Hambrick and Mason 1984), leading to the wave of research on top management team of firms (e.g., CEO, entrepreneurs, and managers). Given CSR is a crucial decision (Xu and Ma 2022), scholars have paid great attention to the influence of executives’ characteristics on CSR (e.g., Jiang et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2018). Early studies investigated the relationship between executives’ demographic characteristics and firms’ CSR, such as gender (Peterson and Philpot 2007). As the research further develops, scholars investigated the influence of executives on firms’ CSR in two perspectives: (1) their background or experience; (2) their psychological traits.

On one hand, studies have pointed out that “ethical training, cultural background, and life experiences all play a role in establishing the principles that motivate human behavior” (Wood 1991). In the context of CSR, scholars also recognized the influence managers’ background or experience, such as CEOs’ academic backgrounds (Ma et al. 2020), early famine experience (Xu 2023) and their political ideologies (Jiang et al. 2018). Especially, religion, one of the crucial social norms, which can shape individuals’ personal belief, value, and attitudes toward both economic, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities of business, has garnered increasing attention (Wang and Lu 2021). Previous research has found that religious atmosphere in a region can induce managers to be less selfish and more stakeholder orientated, which results in an enhanced commitment to CSR in firms (Su 2019). And managers’ religious school attendance experience has a positive relationship with CSR performance (Xu and Ma 2022). On the other hand, the effect of managers’ personality or psychological traits on firms’ CSR has also been receiving growing attention, such as hubris (Tang et al. 2015), narcissism (Petrenko et al. 2016), overconfidence (Sauerwald and Su 2019). For instance, Petrenko et al. (2016) highlighted that CSR can be a response to leaders’ personal needs for social attention and image reinforcement, thereby illustrating that CEO narcissism has positive effects on CSR.

Based on the above, prior studies have largely examined the role of religions or culture in executives’ altruistic motives behind CSR, or the influence of their personalities on the egoistic motivations related to social wealth. However, existing CSR research appears to overlook the influence of religions or culture from the perspective of egoistic motivation. Unlike stable psychological traits such as overconfidence, “luck belief” is based on informal institutions. However, these factors may interact with each other. According to attribution theory, self-serving bias indicates that people tend to attribute failures to bad luck and successes to personal ability and effort (Miller and Ross 1975), which may lead to overconfidence (Camerer and Lovallo 1999). This makes luck belief a unique but potentially interacting antecedent factor in the cognitive framework of top managers. In reality, religions can affect individuals’ perception of their potential loss and induce executives conduct CSR for self-serving motives. In our study, we focus on executives’ perception of their luck, which is a significant element of executives’ beliefs derived from superstitious cultures, being an area that has garnered considerable attention among scholars (Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a). We investigate its influence on CSR decision by combining the religious culture and personal psychological bias.

Zodiac year superstition and belief in luck

Superstitions about future uncertainty and preventing misfortune, including astrology and fortune-telling, are widespread in many cultures and modern societies (Fisman et al. 2023). In Taoist culture and traditional Chinese astrology, each lunar year in a 12-year cycle is associated with a specific animal, essentially forming the Chinese zodiac (sheng xiao in Chinese)Footnote 1 (Levitt 1997). Every Chinese individual has a zodiac sign (sheng xiao animal) designated based on their Chinese lunar year of birth, which is an important dimension of their horoscope (ba zi in Chinese). For example, individuals born in the dragon year are often believed to be superior (Chen 2018). Additionally, a widespread belief is that one’s birth year and zodiac sign can predict luck. Specifically, in Chinese astrology, every 12th year—one’s zodiac year of birth (ben ming nian in Chinese)—brings bad luck and thus poses risks or misfortunes, including health issues, career challenges, and economic loss (Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a). Such belief reflects an irrational cognition related to luck and one’s expectations of external control (Darke and Freedman 1997).

According to the psychological literature, irrational belief in luck can influence an individual’s risk expectations and behaviors (Chiu and Storm 2010). For example, belief in bad or good luck will cause individuals to either underestimate or overestimate the probability of success and hence affect their decision-making (Wohl and Enzle 2002). In the context of the Chinese zodiac year superstition, individuals in their zodiac year usually believe bad luck is with them and will be extremely cautious in making decisions, including turning to no-risk investments (Fisman et al. 2023). Such a belief in bad luck during one’s zodiac year is still widespread across China (Li et al. 2021a) and influences managers’ decision-making. Scholars have recently paid attention to the influence of the zodiac year superstition and reported a lower level of firms’ risk-taking during managers’ zodiac year, including increasing cash holdings and reducing R&D expenditures and acquisitions (Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a), and increasing corporate charitable donations (Cai et al. 2025). Their findings extend our understanding of the important role of irrational beliefs in business, but they mainly focus on the riskiness of activities without considering their potential benefits. Moreover, they only investigate the influence of the zodiac year superstition by examining decisions during firms’ managers’ zodiac year. In China, one’s zodiac year recurs every 12th year since birth, indicating that it is not a random event but can be anticipated. How firms’ decision-makers will act in advance to reduce the likelihood of bad luck is a topic that remains unanswered.

Existing research has confirmed that the belief in luck can inhibit managers’ adventurous behaviors during the zodiac years. However, we believe that there might be a deeper behavioral manifestation, namely the pre-emptive response when facing misfortune. Therefore, the core issue of our study is that the executives’ luck beliefs not only inhibit risks when threats arise, but also prompt them to take specific preventive actions, such as firms’ charitable donations, before the misfortune actually occurs.

Zodiac year superstition and firms’ charitable donations

Previous research has shown that CSR activities are affected by the culture of a region and the perceptions of firm executives (Wood 1991; Xu and Ma 2022). As the zodiac year superstition is deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and strongly correlates with managers’ risk attitudes, we hypothesize that it shapes firms’ CSR. Focusing on charitable donations, a prevalent form of external CSR (Ge and Zhao 2017), we examine the influence of executives’ zodiac year beliefs on firms’ donations.

Based on the self-protection theory, managers who face the threat of bad luck in their zodiac year may take preventive charitable actions as a way to alleviate psychological risks, by performing symbolic good deeds to establish “moral insurance” to cope with expected unfortunate events. The belief in luck can affect an individual’s decision-making, manifested as making preparations in advance to obtain good luck or avoid bad luck. For example, some athletes are inclined to wear lucky charms during major matches (Burger and Lynn, 2005). The sign for the 13th floor in buildings is typically removed while the Chinese avoid using the number “4” as they are “unlucky” numbers in relevant culture (Fisman et al. 2023). Such phenomenon can also be found in the capital market; for instance, Chinese firms are more likely to choose “lucky” numbers rather than “unlucky” numbers during initial public offering (Hirshleifer et al. 2018). One’s zodiac year occurs once every 12 years, and traditionally is considered unlucky. Considering the bad luck brought by each zodiac year, people often take preventive measures, such as wearing red clothes, to resist the evil power of the zodiac year. This time strategy is consistent with the recorded risk-aversion patterns, such as the peak of insurance purchases before the zodiac year (Fisman et al. 2023), and reflects the desire to protect the interests of individuals and organizations before the escalation of the crisis. Therefore, in addition to reducing high-risk investments (Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a), corporate leaders are also believed to take measures to mitigate potential adverse factors before their zodiac year arrives.

At the same time, the self-enhancement theory states that making donations before the zodiac year can allow managers to maintain a positive leadership image and control, avoiding attributing charitable behavior to desperate emotions driven by superstition. Among firms’ business activities, CSR can provide insurance-like effects (Shiu and Yang 2017). As an important part of CSR, corporate philanthropic activities, which involve “doing good” for society and signify firms’ altruism (Dong et al. 2021), are highly beneficial to firms’ reputation and can increase shareholder reaction (Cha and Rajadhyaksha 2021). Thus, charitable donations have a strong insurance effect on future negative events (Godfrey et al. 2009). Firms’ charitable donations can also improve CEOs’ social attention and reputation (Zhu and Zhao 2023). A good reputation serves as an intangible asset for individuals or organizations to handle adverse events (Zavyalova et al. 2016). Meanwhile, Taoism advocates people’s virtue, which is called Dé (also Te) (Du et al. 2016). In China’s Taoist culture, virtue is accumulated through good deeds (xing shan ji de). In other words, people can do good things to accumulate good fortune for the future. Thus, making donations ahead of the zodiac year can be regarded as a good way to save good luck that would buffer the decreasing luck in the coming zodiac year.

To further explore the practical relevance of these theoretical considerations, we conducted interviews with MBA students, who, as managers, have profound insights into management practices. The interview results showed that many of them did take preventive measures one year before their zodiac years to alleviate the possible misfortunes. They emphasized the psychological comfort and sense of control brought by these preventive actions. They also stressed that it would be too late to take action in the year of zodiac year, which is consistent with the aforementioned mechanisms of self-protection and self-enhancement.

On the basis of the preceding discussion, we propose that firms’ leaders are more likely to conduct business activities linked to good deeds (e.g., donations) in advance to accumulate good luck or gain insurance for the coming zodiac year. As chairpersons generally serve as the ultimate decision-makers of firms (Fisman et al. 2023), we focus on chairpersons and their anticipation of the zodiac year. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1 Firms’ charitable donations increase as the zodiac year of their chairpersons approaches.

Boundary conditions

Hypothesis 1 predicts a positive relationship between chairpersons’ anticipation of their zodiac year and firms’ charitable donations. In this part, we explore the boundary conditions of this relationship by identifying factors that may influence chairpersons’ zodiac year belief and the ability to conduct good deeds.

Moderating role of Taoist atmosphere

As the Chinese zodiac astrology and zodiac year superstition are among the ideological contents of Taoism (Levitt 1997), we argue that Taoism culture influences the degree of chairpersons’ belief in the zodiac year superstition and the relation between the zodiac year superstition and firms’ charitable donations. In China, Taoism is the principal indigenous religion (Su 2019), but it also has other registered religions, including Buddhism, Catholicism, and Islam. Thus, the religious atmosphere varies across regions.

We argue that regional Taoist cultural atmosphere strengthens the perceived legitimacy and salience of this superstition among chairpersons, thereby amplifying its influence on philanthropic behavior. It is important to note that Taoist cultural influence operates not merely through individual belief, but through social reinforcement and normative pressure. The religious atmosphere reflects the religious culture and traditions of a region (Wang and Lu 2021). The doctrine or belief of a religion can serve as a type of social norm associated with people’s ethical perceptions (Du et al. 2016) and further influence individuals’ behavior (Su 2019). Previous studies have pointed out that firms’ managers can be affected by the religious atmosphere in the region where the firms are located, even when managers have no obvious religious beliefs (El Ghoul et al. 2012). In particular, religious sites can promote the diffusion of relevant beliefs through physical and social interactions with those sites and with peers in the same region (Su 2019). Consequently, when firms are located in regions with strong Taoist atmosphere, their chairpersons are likely to be influenced by the zodiac year superstition. In particular, they are likely to increase their firms’ charitable donations in anticipation of the coming zodiac year to accumulate good luck or obtain insurance for hedging the potential bad luck. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 The positive relationship between chairpersons’ anticipation of their zodiac year and firms’ charitable donations is highly pronounced for firms located in regions with strong Taoist atmosphere.

Moderating effect of family firm

The influence of managers’ perceptions on firms’ strategies and activities also depends on their power. In private firms, the chairperson usually owns the ultimate control (Fisman et al. 2023). Particularly in family firms, Family ownership provides family owners with the authority and control to determine the firms’ strategic goals based on the family agenda and reasons (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011). Thus, we argue that family firm control influences the relation between the zodiac year superstition and firms’ charitable donations.

Family members are not rational economic persons, and their family or personal demands are strong drivers of family firms’ behaviors (Li et al. 2021b). Scholars have found that a key motivation for family firms’ CSR is to maintain or increase the family’s socioemotional wealth rather than economic outcomes (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011). Family firm will transfer the family’s values to the firm (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2011), and family members view the firm as an extension of the family. They attach great importance to their roles within the family business and pay close attention to the internal management and external image of the enterprise (Berrone et al. 2012). Threats to the manager’s luck are often perceived as threats to the family’s reputation and legacy. Thus, when the chairperson of a family firm is approaching their zodiac year, the bad luck belief can be a strong driver for firms’ business decision. That is, they are more likely to do things in anticipation of the coming zodiac year to fulfill their own personal emotional objectives, such as accumulating good luck.

Furthermore, when family firms’ owners are risk-averse, they are likely to invest in self-insurance activities because such activities reduce the severity of any possible losses that might occur (Briys and Schlesinger 1990). Charitable donations can have an insurance effect by accumulating moral reputational capital for a firm (Godfrey et al. 2009). Moreover, charitable donations may be an especially strong signal of generosity for family firms given the enduring social and emotional bonds that many families have with their firms (He and Yu 2019). Scholars have also found that family firms’ religious CEOs engage in charitable behavior and that the signaling of moral capital may be even greater (Maung et al. 2020). Family firms’ managers view charitable actions not only as a means to ensure personal safety, but also as a way to enhance the status and reputation of the family business. In other words, charitable donations have a relatively strong insurance effect on family firms’ leaders who are influenced by religion. Accordingly, chairpersons influenced by Taoist culture are more likely to use charitable donations as an insurance to hedge the potential bad luck brought about by their upcoming zodiac year.

In this study, we argue that for family firms, the influence of the zodiac year superstition on firms’ charitable donations is relatively strong. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 The positive relationship between chairpersons’ anticipation of their zodiac year and firms’ charitable donations is pronounced for family firms.

Data and methods

Data and sample

Our sample comprises data on Chinese mainland listed firms from 2007 to 2022. Our study period starts in 2007 because Chinese firms required to disclose donation in their annual report in that year. The data are obtained from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). As chairpersons in China are generally the ultimate controllers of firms and usually have the highest decision-making authority (Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a), we focus on chairpersons’ zodiac beliefs and identify the board chairs. We collect chairs’ biographical data, including birthdate, gender, and education, from the CSMAR database, Sina Finance, and Google/Baidu. Following previous studies (Li et al. 2021a), we exclude firms with foreign-born board chairs, those experiencing board chair turnover and observations with missing information. Our final sample comprises 35,806 firm–year observations from 4, 217 firms.

Variables and measurement

Dependent variables

(1) Log of donation, measured as the logarithm of the total donation for cases with a positive donation amount in year t, leaving those cases with no donation as zero (Zhang et al. 2016). (2) Donation ratio, measured as the ratio of firms’ total donations to sales (one thousand yuan) in year t, leaving those cases with no donation as zero (Zhu and Zhao 2023).

Independent variable

We construct Pre zodiac year, which equals 1 if year t is one year before the chair’s zodiac year and 0 otherwise. The chair’s zodiac year is the year that the zodiac sign is the same as her/his birth zodiac year, which recurs every 12 years (Li et al. 2021a). We gather the birthdates of the firms’ chairs, which can only be specified by birth year and birth month. For instance, someone born in July 1989 (Year of the Snake) would have their zodiac year in 2001, 2013, 2025, 2037, and so on. As zodiac year is calculated based on the Chinese lunar calendar and the Chinese New Year begins sometime between late January and mid-February, we assign chairpersons born in January to the previous year’s zodiac animal and confirm their zodiac, following prior studies (Fisman et al. 2023). For instance, China’s Lunar New Year in 1989 was on February 6th. Consequently, individuals born between January 1th and February 5th of that year are attributed to the zodiac sign Loong (also called Dragon), rather than Snake. Therefore, the years 2000, 2012, 2024, and 2036 mark their respective zodiac years. Due to the absence of precise birth dates for the chairs, those born in February are assigned the zodiac animal of their birth year. Moreover, in the robustness test we exclude observations where the chair’s birth month matches the lunar New Year month, as it would makes zodiac year determination ambiguous.

Moderating variables

We construct two moderating variables. (1) Family firm: A dummy variable that equals one if the firm is a family firm in year t and zero otherwise. We define the family firm as firms in which the actual controller is a natural person, and at least one family member holds a position in board or top management team, following Chrisman and Patel (2012). (2) Since religious sites are a physical embodiment of the religious atmosphere, we measure the Taoist atmosphere by using which is measured as dividing the number of Taoist temples in the city where the firm is located by the total population of the city (Xu and Ma 2022).

Control variables

We control for several factors that likely influence firms’ charitable donations following extant research (Zhang et al. 2016). At the firm level, we control for Firm size, measured as the log of firm assets in year t-1 as larger firms are more likely to face greater public scrutiny over their social practices (Zhu and Zhao 2023); and Firm age, measured as the number of years since the firm’s listing on the stock market in year t (Marquis and Qian 2014). We include Firm profitability as return on assets and Firm leverage as the ratio of debt to sales as charitable donations is related to firms’ financial conditions. We include CSR evaluation, measured as firms’ CSR ratings from Hexun in year t-1, to control for firms’ past engagement in CSR. We include SOE, which equals 1 if the firm is ultimately controlled by the government and 0 otherwise (Marquis and Qian 2014); Largest shareholding, which is measured as the proportion of the first largest shareholder (%); and Duality, which is coded as 1 for firms with a dual CEO–chair and 0 otherwise. We also include Inddirector, which measured as the proportion of independent directors in the board, since it would influence firm’s decision. Moreover, we control Firm visibility, measured as the log of the number of media coverage the firms received in year t-1, following prior study (Marquis and Qian 2014).

At the chairperson level, we control for Chairman age as age may influence the resources available to them and their risk-taking; Chairman gender, which equals 1 if the firm’s chairperson is male and 0 otherwise; Chairman education, which is coded as 0 for no college experience, 1 for bachelor’s degree, 2 for master’s degree, and 3 for doctoral degree; and Chairman overseas background, which equals 1 if the firm’s chairperson has overseas work or education experience and 0 otherwise.

At the macro level, we control for Industry concentration, measured as the Herfindahl–Hirshman index in the focal firm’s industry (four digits) in year t-1, as high levels of concentration reduce intra-industry competition and influence firms’ CSR (Flammer 2018); and Market development, measured as the marketization index of the province where the firm is located in year t-1 (Wang et al. 2019). Finally, we control for year and firm fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity, which is according to the result of the Hausman test (p = 0.000).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 indicates that the independent variable Pre zodiac year is positively correlated with Log of donation and Donation ratio. Moreover, all VIF values are less than 2.00, and the mean VIF value is 1.27, which is below the recommended benchmark of 10, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a serious concern in our analysis.

Hypotheses testing

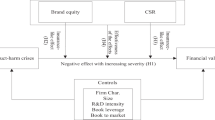

Table 2 presents the results with Log of donation as the dependent variable. Model 1 reports the result of baseline model. Model 2 reports the main effect and shows that the coefficient on Pre zodiac year is significantly positive (p < 0.05). Thus, the result supports Hypothesis 1, which states that firms would make more charitable donations as their chairpersons’ zodiac year approaches. The coefficient on the interaction Pre zodiac year × Family firm in Model 3 is positive and significant (p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 2. In Model 4, the coefficient on the interaction Pre zodiac year × Taoist atmosphere is also positive (p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 3. Model 5 presents the full model, and both moderating effects are significant. We calculate economic significance following Genin et al. (2021), since our dependent variable is log-transformed. The results indicates that Pre zodiac year raises firm-year donation by 19.5% (e^0.178–1), holding other variables constant. This increase translates to an additional RMB 336,850 (yuan) in donation, based on the mean donation of RMB ¥1,727,436 (1,727,436×19.5% = 336,850).

Table 3 presents the results for the dependent variable Donation ratio, which is measured as the ratio of firms’ donation (yuan) to sales (thousand yuan) and shows that all the hypotheses remain supported. Similarly, we calculate economic significance, following Flammer and Kacperczyk (2019). The results indicates that Pre zodiac year raises firm donation ratio by 8.53% (0.038/0.445), holding other variables constant. This increase translates to an additional RMB 357,200 (yuan) in donation, based on the mean sales of RMB 9,400,000 (thousand yuan) (0.038 × 9,400,000 = 357,200). Due to the winsorization of both dependent variables, there are minor discrepancies in the resulting economic effect sizes. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that board chairs are motivated to engage in corporate donations in advance, to counteract the perceived misfortune of their upcoming zodiac year.

To further show the effect of Pre zodiac year, we conduct a T-test (reported in Table 4) and illustrate the comparison of firms’ donation between Pre zodiac year and other years in Fig. 1. As Table 4 shows, both dependent variables Log of donation and Donation ratio are significantly larger in one year prior to zodiac year than in other years (p = 0.028, p = 0.081, respectively). Figure 1 also shows the tendency. This result lends support to our hypotheses.

Robustness tests

We conduct several robustness tests to ensure the robustness of our study.

Including chair fixed effect

To further probe robustness, we include chairperson fixed effects. Model 1 and Model 3 of Table 5 report the results, showing significantly positive coefficients on the independent variable Pre zodiac year; Model 2 and Model 4 of Table 5 present that both moderating effects are significant, and thereby reinforcing our findings.

Including the influence of zodiac year, post zodiac year and CEOs’ Pre zodiac year

First, to further examine the influence of Pre zodiac year instead of the influence of other years by construct a dynamic model following Fisman et al. (2023). Specifically, we construct three additional variables to represent the 2 years preceding the chair’s zodiac year, the year of the chair’s zodiac year, one year post the chair’s zodiac year, respectively. We utilize dummy variables for all measures and incorporate them into the baseline model specification. Models 1 and 2 in Table 6 report the results after including Pre zodiac year and the three new variables, which shows that the coefficients on Pre zodiac year are still significantly positive (p < 0.05, p < 0.05 respectively), thus supporting our hypothesis that chairpersons may increase firms’ charity donations to ensure good luck one year before their zodiac year. However, the coefficients on other variables are almost insignificant, which suggests that firms’ charity donations do not increase during their chairpersons’ zodiac year. We attribute this phenomenon to the chair’s stronger motivation for risk aversion over “luck-seeking” in their actual zodiac year. Previous studies have demonstrated that belief in the zodiac year elevates managers’ risk perception, which leads to reduced investments (e.g., in R&D) and higher corporate cash holdings during the chair’s zodiac year (Li et al. 2021a). Consequently, the chairs choose to maintain corporate cash holdings instead of increasing investments (including donations) in their zodiac year, due to the substantial financial outlay that donating represents.

Second, to control for CEO influence, we construct the variable Pre zodiac year of CEO, coded as one if year t is one year before the CEO’s zodiac year and zero otherwise. Models 3 and 4 in Table 6 report the results after incorporate the variable into the baseline model. The results show that the coefficients on Pre zodiac year are still significantly positive (p < 0.1, p < 0.05, respectively). Hence, Hypothesis 1 is supported. We also noted that the coefficient on Pre zodiac year of CEO in Model 3 is insignificant and in Model 4 is slightly significantly (p = 0.09). This pattern is explained by the relatively concentrated equity structure in China, which generally grants chairpersons the ultimate controllers and supreme decision-making authority (Li et al. 2021a), overshadowing CEO influence.

Adopting propensity score matching approach

Following previous research (Li et al. 2021a), we use propensity score matching (PSM) to mitigate potential endogeneity due to the observable differences between firms managed by chairpersons in their pre-zodiac years and those who are not. Specifically, in the first step, we estimate the likelihood of certain firms being managed by chairpersons in their pre zodiac year by using Pre zodiac year as the dependent variable and including the full set of control variables). We implement nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.01, performing 1:3 matching. This procedure generates 10,980 unique matched firm–year observations, among which 3095 observations are firms managed by chairpersons in their pre-zodiac years and 7885 observations are not. Table 7 reports t-test results of all independent variables between the treated and control groups, before propensity score matching and after matching. The T-test results show that no significant difference exists for any of the variables after matching.

In the second step, we rerun the regressions based on the matched sample. Table 8 reports the results based on the matched samples, which presents that the coefficients on Pre zodiac year are still significantly positive (p < 0.05, p < 0.1 respectively), consistent with our main analyses.

Placebo test

To mitigate the problem of spurious correlation in large samples, we conduct a placebo test on the main hypothesis, following existing studies (Eggers et al. 2024). Specifically, following the actual proportion of firms managed by chairpersons in their pre-zodiac years in the sample, we randomly selected from the sample and assign variable Pre zodiac year to one, which is regarded as new “pseudo” treatment group. Since the new treatment group is generated randomly, the “pseudo” independent variable Pre zodiac year should theoretically have no significant effect on firms’ donation. Conversely, if the coefficient of the pseudo dummy variable is significantly different from zero, it indicates the presence of spurious correlation in the regression model, suggesting that the earlier regression results may be driven by some unobservable inherent differences in the sample. To ensure the robustness of the results, the original sample was randomly shuffled 500 times, and the main hypothesis was re-tested following the above procedure.

Figure 2 presents the results of the placebo test based on 500 random assignments. The horizontal axis represents the estimated coefficients of the “pseudo” Pre zodiac year, the left vertical axis indicates kernel density distribution of coefficients. The mean value of the coefficient for the “pseudo” Pre zodiac year is zero and significantly deviates from the actual regression coefficient value of 0.178 (as indicated by the dashed line). This demonstrates that after random permutation, whether the year is Pre zodiac year has no significant effect on the firms’ donation. The baseline conclusions of this paper are less likely to be driven by unobservable omitted variables, and no serious issue of spurious correlation exists.

Alternative samples

We also run regression models by narrowing the sample. First, we restrict our sample to firms with chairs who have served for more than 12 years, which including 7,853 observations with 575 firms. Model 1 and Model 2 of Table 9 report the results, which shows the coefficients on Pre zodiac year are still significantly positive (p < 0.001, p < 0.05, respectively). Second, we exclude observations where the chair’s birth month matches the lunar New Year month, as it would makes zodiac year determination ambiguous. The results are shown in Model 3 and Model 4 of Table 9, also consistent with our main analyses.

Supplementary analyses

Mechanism testing

To further reveal the mechanism between Pre zodiac year and firms’ donation, we conduct two grouping analyses. As established previously, firm leaders engaging in charitable activities in advance to accumulate goodwill against the potential risk of upcoming zodiac year. Consequently, leaders in firms facing higher perceived misfortune risk exhibit heightened motivation for luck-seeking behavior. We adopt two dummy variables to measure the perceived misfortune risk that firms face. (1) Firms’ performance serves as a crucial indicator of their risk level. When a firm’s performance is below aspiration levels, executives will view low performance as a problem (Greve 2003). Thus, we construct variable Below Aspiration, which equals to one if a firm’s performance in year t-1 fell below its performance in year t-2, and zero otherwise (Jung et al. 2023). (2) Firms’ negative news also indicates firms’ risk level. Scholars noted that negative reports negatively impact firms’ reputation and legitimacy, and even lead to sanctions by stakeholders (Zhu and Zhao 2025). Thus, we construct variable More negative news, which equals to one if a firm’s ratio of negative news to total news exceeds the industry mean, and zero otherwise. We then estimate our primary regression model by grouping the sample based on these two variables.

Table 10 presents the results grouped by Below Aspiration, indicating that the independent variable Pre zodiac year is significantly and positively correlated with both dependent variables—Log of donation and Donation ratio—when Below Aspiration = 1, but insignificant when Below Aspiration = 0. These findings suggest that chairpersons are more likely to seek good luck through donations ahead of their zodiac year when the firms face higher performance risk. Similarly, Table 11 shows the results grouped by More negative news. Here, Pre zodiac year is significantly and positively associated with both dependent variables when More negative news = 1, but not when it equals 0. This implies that chairpersons are more inclined to make donations for luck prior to their zodiac year when the firm is exposed to greater reputation risk. The above results further proves that firm leaders are motivated to engage in preemptive charitable activities to accumulate good luck ahead of the potential risks of their upcoming zodiac year.

Impact of pre zodiac year on donation detail and relevant decisions

We also conduct several regressions by using alternative dependent variables. First, we construct two variables to unpack firms’ donation decision: (1) Donationnum, which is measured as the number of donation projects disclosed in non-business expenditure of balance sheet; (2) Log of averagedonation, which is measured by dividing the total donation amount by the number of donation projects. We include both Pre zodiac year and Zodiac year in the regressions. Model 1 and Model 2 of Table 12 present the results, which shows that the coefficient on Pre zodiac year is only significantly positive for dependent variable Donationnum, but insignificant for dependent variable Log of averagedonation. And the coefficients on Zodiac year are both insignificant. The results suggest that firms’ charitable donations increase in one year before the chair’s zodiac year, because the num of donation projects increases. And these donation projects are very likely to be newly added temporarily rather than regularly projects in the long term.

Second, we also construct a new variable Quietgiving, to reflect the disclosure of firms’ charitable donations. Quietgiving is a dummy variable, which equals to one if the firm discloses the amount of donations in its annual report for the year but fails to disclose any donation information in its CSR report, and zero otherwise (Wang et al. 2021). As shown in Model 3 of Table 12, the coefficient on Pre zodiac year is significantly negative, suggesting that chairpersons donate more in the year preceding their zodiac year but prefer to do so discreetly. This indicates that such donations are not mainly driven by tangible benefits (e.g., reputational concerns, political capital, and stakeholder appeasement), but rather by a desire for psychological reassurance—an egoistic motivation we term “luck-seeking” behavior.

Third, we construct a variable Liability insurance, to examine the effect of Pre zodiac year on firms’ insurance activity. Liability insurance, a dummy variable, equals to one if the firms announced they buy liability insurance for directors and managers in year t; and zero otherwise. Model 4 of Table 12 shows a significantly positive coefficient on Pre zodiac year, indicating that firms are more likely to purchase liability insurance in the year before the chair’s zodiac year. Based on a review of numerous corporate announcements, such insurance typically carries a one-year term starting from the announcement date. Therefore, the liability insurance purchased in the year preceding the zodiac year appears to serve primarily as a hedge against the potential risk of upcoming zodiac year. The above results further proves that firm leaders are motivated to take proactive activities, to mitigate the potential risks of their upcoming zodiac year, whether for psychological or actual security.

Qualitative evidences

To further validate the hypotheses proposed in this study, we also conducted a series of interviews, primarily selecting chairs or managers of enterprises from the MBA students at our university. Several interviewees remarked: “I, along with many business acquaintances around me, still hold considerable belief in traditional Chinese customs” and “when it comes to the impact of zodiac year, the prevailing attitude is ‘better to believe it exists than to assume it does not’”. When asked, “What actions do you intend to take as your zodiac year approaches?”, some respondents replied, “Besides purchasing red strings and red clothing in advance, I generally pay more attention to public welfare activities. As the old saying goes, “accumulating fortune through good deeds.’” We also ask the question, “When you make donations, what is your primary motivation? Is it purely about doing good, or are there other factors involved?” The interviewees answered, “The intention to do good is certainly a part of the reason, but there are also personal considerations. We believe performing good deeds can bring safety and accumulate positive karma, which feels especially important during sensitive periods.” They also stated that such self-motivated belief becomes stronger as the zodiac year approaches. To the follow-up question, “Why do you engage in philanthropic activities in advance?”, some respondents argued: “There is an old saying in Chinese— ‘preparing for adversity’ (Wei yu chou mou in Chinese)”; “It feels like trying to ‘accumulate merit’ during the year of bad luck would simply be too late.” The interview data added further insights into our hypothesized relationship.

Discussion and conclusion

Recent research has paid attention to the motivation behind firms’ charity, and broadly categorizing them into egoistic related to explicit economic benefits and altruistic drivers attributed to religious culture (Zhou and Liu 2024). However, the role of superstitious beliefs—particularly those related to luck—has been largely overlooked. Superstitions, which persist across most cultures and are thought to affect outcomes in uncertain situations, remain prevalent in modern societies (Fisman et al. 2023). Focusing on the Chinese astrological belief that one’s zodiac year brings bad luck, we propose that managers increase corporate charitable donations in advance to seek protection or attract good fortune. Using data from Chinese listed firms, we find that anticipated misfortune leads to higher donations prior to the zodiac year, underscoring the influence of executives’ nonstandard beliefs on CSR practices. This effect is more pronounced in regions with a strong Taoist culture and within family-controlled firms. Our study reveals a mechanism of an egoistic motivation to explain executives’ donation decisions. Robustness checks and supplementary analyses further support the presence of an egoistic psychological motivation behind these preemptive charitable contributions.

Theoretical implications

Our study contributes to the literature on behavioral finance, upper echelons theory, superstitions and CSR. First, this study contributes to both behavioral finance and upper echelons theory by examining the influence of managers’ nonstandard beliefs on CSR. Existing research in these streams has established that managerial beliefs significantly influence firm decisions (e.g., Barrero 2022; Xu and Ma 2022). However, prior work has predominantly focused on executives’ stable long-term psychological traits—such as religious beliefs (e.g., Cai et al. 2019; Xu and Ma 2022), optimism (e.g., Deshmukh et al. 2021), and political ideology (e.g., Jiang et al. 2018) —while largely overlooking dynamic shifts in managerial psychology. Introducing a superstition perspective, our study demonstrates that executives’ sense of being “lucky” varies across contexts and timing, thereby influencing strategic decisions. By highlighting the role of the “Zodiac year” superstition in shaping chairs’ psychological states, we provide novel empirical evidence on how short-term perceptions of misfortune affects corporate charity donations. Thus, this study extends the theoretical framework on psychological underpinnings of executive behavior.

Second, we contribute to the CSR research by further unpacking the black box of the motivation behind executives’ charity. Existing research has extensively examined corporate philanthropic motives, broadly categorizing them into egoistic and altruistic drivers (Zhou and Liu 2024). Egoistic motivations are typically linked to explicit benefits such as economic gain, political advantages, and reputational capital (e.g., Jiang et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016). Altruistic motivations, on the other hand, are often attributed to the moral or educational influence of religious culture, which encourages selflessness among executives (e.g., Su, 2019; Xu and Ma 2022). Our study, however, reveals that under the influence of zodiac year superstition—which is one ideological aspect of Taoism religion (Levitt 1997), executives may also engage in donations out of egoistic motives. Specifically, such behavior is driven not by tangible benefits, but by the desire to invoke personal luck and ward off potential future risks. These findings refine and expand our understanding of corporate donation behavior, especially in emerging markets where superstitions may be prevalent, by introducing a nuanced, psychologically grounded motivation that transcends the conventional egoistic-altruistic dichotomy.

Third, our study advances the understanding of how superstitions shape corporate decision-making. While prior studies have explored the role of luck perception in executives’ behavior, they focused primarily on executives’ risk preferences (e.g., Fisman et al. 2023; Gao et al. 2021; Hirshleifer et al. 2018), neglecting how superstitious beliefs influence managers’ assessment of potential benefits. Moreover, prior studies have largely considered the impact of superstitions within the current period (e.g., Fisman et al. 2023; Li et al. 2021a), neglecting the anticipatory nature of luck perception, which can lead to preventive decision-making far in advance. By demonstrating that executives make preemptive charitable donations to counteract anticipated misfortune in the upcoming zodiac year, our study reveals how such superstitions engender an insurance-like perception of charity and a belief in its power to attract future good fortune, thereby prompting proactive managerial responses. Overall, this research introduces both a temporal dimension and a benefit-assessment perspective to the management literature on the superstitious culture, thereby extending prior work by uncovering how superstitions can proactively influence corporate decision-making within the realm of charitable donations.

Practical implications

Our findings also offer significant practical implications for stakeholders, including executives, investors, and policymakers.

First, this research highlights that superstition can influence executives’ perception of their luck, consequently materially affecting corporate decisions, including philanthropic contributions and investment in liability insurance. Investors and other stakeholders should incorporate an assessment of top managers’ superstitious beliefs into due diligence processes and governance evaluations. For instance, during executive selection or board appointments, stakeholders may examine behavioral cues, such as the design of workplaces, participation in religious or superstitious activities, or regional cultural factors of their growth environment, to gauge the extent to which irrational beliefs may drive decision-making. Investors can also conduct behavioral interviews or surveys. Special attention should be paid in regions with a stronger presence of religious sites (e.g., Taoist temples), in family-controlled firms, and in situations where firm performance is declining or negative publicity arises, as the superstitious effect is more pronounced under these conditions.

Second, stakeholders such as civil society organizations and industry watchdogs could encourage greater transparency around corporate philanthropic motives and promote more rational decision-making frameworks that align with long-term business objectives. Moreover, although this study is situated in the Chinese cultural context, its implications extend to other settings where non-standard beliefs (e.g., astrology, numerology, or omens) may influence managerial behavior. A deeper understanding of how such beliefs operate can help global investors and multinational firms better anticipate and mitigate superstitious risks in cross-cultural management.

Third, policymakers can use these insights to encourage the adoption of diversity and inclusion policies that acknowledge cultural beliefs while promoting evidence-based governance. For example, governments could develop guidelines that help firms balance respect for cultural diversity with the need to avoid superstitious bias in strategic decisions. Additionally, corporate governance codes could emphasize the importance of rational and transparent procedures in areas such as donations and risk management, thereby reducing the potential negative impact of non-standard beliefs. By recognizing and addressing the role of superstition in management, all stakeholders can contribute to more rational, transparent, and sustainable corporate practices—both within and beyond cultural contexts where such beliefs are prevalent.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that suggest fruitful future directions. First, it examines the impact of “zodiac year” superstition solely through the lens of corporate donation. Future studies could extend this line of inquiry to other domains of CSR, such as environmental practices, employee relations, or supply chain ethics.

Second, our measure of religious atmosphere is constructed at the macro level, which captures broad cultural exposure but may not adequately reflect individual-level variation in superstitious belief. Moreover, due to data constraints, the current study treats “zodiac year” superstition as a static influence. Future research could develop a more nuanced psychometric scale and employ longitudinal survey methods to assess executive beliefs directly and dynamically. And future work could investigate how executives’ superstitious beliefs interact with other religious influences and shape decision-making over time.

Third, although the Chinese context provides a compelling setting for this study, and our study can extend to other settings where non-standard beliefs may influence managerial behavior, Future studies could examine whether the behavioral patterns identified extend to other superstitious beliefs or cultural taboos—both within and beyond the Chinese context.

Beyond these limitations, several new research directions emerge. Future studies could investigate the role of corporate governance in either mitigating or amplifying the effects of superstitious beliefs on firm outcomes. Additionally, researchers may employ experimental designs to establish causal mechanisms or utilize fine-grained data to trace how individual executives’ superstitions translate into organizational behaviors. Cross-country comparative studies could also help disentangle the complex interplay of cultural, institutional, and individual factors influencing superstitious decision-making. Finally, integrating methods from cognitive neuroscience or behavioral economics may offer deeper insights into the mental processes that underlie superstitiously motivated strategies.

Conclusion

Our study provides empirical evidence that chairpersons’ zodiac year belief leads to increased corporate charitable donations as a means of seeking luck and avoiding misfortune. The effect is more pronounced in regions with strong Taoist culture and in family firms. Our findings highlight the role of leaders’ non-rational beliefs in CSR decisions and reveal a unique, self-serving psychological motivation behind charitable donations—driven by personal psychological benefits rather than conventional strategic benefits. By introducing the influence of nonrational beliefs into the literature on behavioral finance, upper echelons and CSR, this research expands understanding of how subconscious cultural factors shape corporate decision-making. It also offers practical insights for investors and policymakers to better monitor and mitigate superstitious influences in business contexts.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The Chinese zodiac begins with the sign of the Rat, followed by the Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig.

References

Alicke MD, Sedikides C (2009) Self-enhancement and self-protection: what they are and what they do. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 20(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280802613866

Barrero JM (2022) The micro and macro of managerial beliefs. J Financ Econ 143(2):640–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.06.007

Batlles de la Fuente A, Abad Segura E (2023) Exploring research on the management of business ethics. Manag Lett 23(1):11–21. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.221694ea

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gomez-Mejia LR (2012) Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam Bus Rev 25(3):258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511435355

Briys E, Schlesinger H (1990) Risk aversion and the propensities for self-insurance and self-protection. South Econ J 57(2):458–467. https://doi.org/10.2307/1060623

Brownell KM, Cardon MS, Bolinger MT, Covin JG (2024) Choice or chance: How successful entrepreneurs talk about luck. J Small Bus Manag 62(3):1684–1717. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2023.2169703

Burger JM, Lynn AL (2005) Superstitious behavior among American and Japanese professional baseball players. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 27(1):71–76. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2701_7

Cai X, Liao L, Pan Y, Wang K (2025) Seeking blessings by doing good: Top executive superstitions and corporate philanthropy. J Corp Financ 92:102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2025.102775

Cai Y, Kim Y, Li S, Pan C (2019) Tone at the top: CEOs’ religious beliefs and earnings management. J Bank Finance 106:195–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.06.002

Camerer C, Lovallo D (1999) Overconfidence and excess entry: an experimental approach. Amer Econ Rev 89(1):306–318. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.1.306

Cha W, Rajadhyaksha U (2021) What do we know about corporate philanthropy? A review and research directions. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib 30(3):262–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12341

Chen T (2018) Dragon CEOs and firm value. Aust Econ Rev 51(3):382–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12277

Chiu J, Storm L (2010) Personality, perceived luck and gambling attitudes as predictors of gambling involvement. J Gambl Stud 26:205–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9160-x

Chrisman J J, Patel P C (2012) Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Acad Manag J 55(4):976–997. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0211

Darke PR, Freedman JL (1997) The belief in good luck scale. J Res Pers 31:486–511. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2197

Deshmukh S, Goel AM, Howe KM (2021) Do CEO beliefs affect corporate cash holdings? J Corp Finance 67:101886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101886

Dong X, Gao J, Sun SL, Ye K (2021) Doing extreme by doing good. Asia Pac J Manag 38:291–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9591-y

Du X, Du Y, Zeng Q, Pei H, Chang Y (2016) Religious atmosphere, law enforcement, and corporate social responsibility: evidence from China. Asia Pac J Manag 33(1):229–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9441-0

Eggers AC, Tuñón G, Dafoe A (2024) Placebo tests for causal inference. Am J Polit Sci 68(3):1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12818

El Ghoul S, Guedhami O, Ni Y, Pittman J, Saadi S (2012) Does religion matter to equity pricing? J Bus Ethics 111:491–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1213-x

Fisman R, Huang W, Ning B, Pan Y, Qiu J, Wang Y (2023) Superstition and risk taking: evidence from “Zodiac Year” beliefs in China. Manag Sci 69(9):5174–5188. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4594

Flammer C (2018) Competing for government procurement contracts: the role of corporate social responsibility. Strateg Manag J 39(5):1299–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2767

Flammer C, Kacperczyk A (2019) Corporate social responsibility as a defense against knowledge spillovers: evidence from the inevitable disclosure doctrine. Strateg Manag J 40(8):1243–1267. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3025

Gao H, Shi D, Zhao B (2021) Does good luck make people overconfident? Evidence from a natural experiment in the stock market. J Corp Finance 68:101933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101933

Ge J, Zhao W (2017) Institutional linkages with the state and organizational practices in corporate social responsibility: evidence from China. Manag Organ Rev 13(3):539–573. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2016.56

Genin AL, Tan J, Song J (2021) State governance and technological innovation in emerging economies: state-owned enterprise restructuration and institutional logic dissonance in China’s high-speed train sector. J Int Bus Stud 52(4):621–645. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00342-w

Godfrey PC, Merrill CB, Hansen JM (2009) The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg Manag J 30(4):425–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.750

Gómez-Mejía LR, Cruz C, Berrone P, De Castro J (2011) The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad Manag Ann 5(1):653–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2011.593320

Greve HR (2003) A behavioral theory of R&D expenditures and innovations: evidence from shipbuilding. Acad Manag J 46(6):685–702. https://doi.org/10.5465/30040661

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manag Rev 9(2):193–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/258434

He W, Yu X (2019) Paving the way for children: family firm succession and corporate philanthropy in China. J Bus Finance Account 46(9–10):1237–1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12402

Hirshleifer D, Jian M, Zhang H (2018) Superstition and financial decision making. Manag Sci 64(1):235–252. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2584

Jiang F, Zalan T, Tse HHM, Shen J (2018) Mapping the relationship among political ideology, CSR mindset, and CSR strategy: a contingency perspective applied to Chinese managers. J Bus Ethics 147(2):419–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2992-7

Jung H, Lee YG, Park SH (2023) Just diverse among themselves: How does negative performance feedback affect boards’ expertise vs. ascriptive diversity? Organ Sci 34(2):657–679. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2022.1595

Koburtay T, Jamali D, Aljafari A (2023) Religion, spirituality, and well‐being: a systematic literature review and futuristic agenda. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib 32(1):341–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12478

Levitt S (1997) Taoist astrology: a handbook of the authentic Chinese tradition. Simon and Schuster

Li J, Guo JM, Hu N, Tang K (2021a) Do corporate managers believe in luck? Evidence of the Chinese zodiac effect. Int Rev Financ Anal 77:101861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101861

Li X, Li C, Wang Z, Jiao W, Pang Y (2021b) The effect of corporate philanthropy on corporate performance of Chinese family firms: The moderating role of religious atmosphere. Emerg Mark Rev 49:100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100757

Liu C, de Rond M (2016) Good night, and good luck: perspectives on luck in management scholarship. Acad Manag Ann 10(1):409–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1120971

Luo J, Kaul A (2019) Private action in public interest: the comparative governance of social issues. Strateg Manag J 40(4):476–502. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2961

Ma Z, Zhang H, Zhong W, Zhou K (2020) Top management teams’ academic experience and firms’ corporate social responsibility voluntary disclosure. Manag Organ Rev 16(2):293–333. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2019.58

Marquis C, Qian C (2014) Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organ Sci 25(1):127–148. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0837

Maung M, Miller D, Tang Z, Xu X (2020) Value-enhancing social responsibility: Market reaction to donations by family vs. non-family firms with religious CEOs. J Bus Ethics 163:745–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04381-8

Miller DT, Ross M (1975) Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin 82(2):213–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076486

Peterson CA, Philpot J (2007) Women’s roles on US Fortune 500 boards: director expertise and committee memberships. J Bus Ethics 72:177–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9164-8

Petrenko OV, Aime F, Ridge J, Hill A (2016) Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strateg Manag J 37(2):262–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2348

Sauerwald S, Su W (2019) CEO overconfidence and CSR decoupling. Corp Gov Int Rev 27(4):283–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12279

Shiu YM, Yang SL (2017) Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance‐like effects? Strateg Manag J 38(2):455–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2494

Su K (2019) Does religion benefit corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Evidence from China. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26(6):1206–1221. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1742

Tang Y, Qian C, Chen G, Shen R (2015) How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir)responsibility. Strateg Manag J 36(9):1338–1357. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2286

Tsang EWK (2004) Toward a scientific inquiry into superstitious business decision-making. Organ Stud 25(6):923–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604042405

Wang H, Jia M, Zhang Z (2021) Good deeds done in silence: stakeholder management and quiet giving by Chinese firms. Organ Sci 32(3):649–674. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2020.1385

Wang H, Qian C (2011) Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: the roles of stakeholder response and political access. Acad Manag J 54(6):1159–1181. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0548

Wang J, Lu J (2021) Religion and corporate tax compliance: evidence from Chinese Taoism and Buddhism. Eurasian Bus Rev 11(2):327–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00153-x

Wang X, Hu L, Fan G (2019) NERI index of marketization of China’s provinces report. National Economic Research Institute, Beijing

Wei J, Ouyang Z, Chen HA (2018) CEO characteristics and corporate philanthropic giving in an emerging market: the case of China. J Bus Res 87:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.018

Wohl MJ, Enzle ME (2002) The deployment of personal luck: Sympathetic magic and illusory control in games of pure chance. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 28(10):1388–1397. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702236870

Wood D (1991) Corporate social performance revisited. Acad Manag Rev 16(4):691–718. https://doi.org/10.2307/258977

Xu B, Ma L (2022) Religious values motivating CSR: an empirical study from corporate leaders’ perspective. J Bus Ethics 176:587–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04688-x

Xu Z (2023) CEOs’ early famine experience, managerial discretion and corporate social responsibility. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):672. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02192-x

Zavyalova A, Pfarrer MD, Reger RK, Hubbard TD (2016) Reputation as a benefit and a burden? How stakeholders’ organizational identification affects the role of reputation following a negative event. Acad Manag J 59(1):253–276. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0611

Zhang J, Marquis C, Qiao K (2016) Do political connections buffer firms from or bind firms to the government? A study of corporate charitable donations of Chinese firms. Organ Sci 27(5):1307–1324. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1084

Zhou L, Liu X (2024) The new government–business relationship and corporate philanthropy: an analysis based on political motivation. Eurasian Bus Rev 14:807–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-024-00269-4

Zhu L, Zhao J (2023) Entrepreneurs’ self-perceived social status and firms’ philanthropy: evidence from Chinese private firms. Asia Pac Bus Rev 29(3):588–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1978235

Zhu L, Zhao J (2025) Do politicians’ career concerns affect firms’ environmental information disclosure? Evidence from Chinesepublicly listed firms. J Bus Res 186:115018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.115018

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 72402249].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the present paper and approved the submission. Limin Zhu was responsible for the conceptualization, theory development, methodology, data collection, data processing, data analysis, and original draft writing. Wenlei Yu was involved in conceptualization, theory development, writing reviews, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Yu, W. From superstition to generosity: the role of executives’ luck belief in corporate charitable donations in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1753 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06045-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06045-7