Abstract

To effectively prepare students for navigating complex societal and sustainability challenges, higher education institutions are increasingly experimenting with transdisciplinary learning environments (TLEs) in which students collaborate with external stakeholders across disciplinary and sectoral boundaries. This empirical study explores how TLEs in Dutch higher education are designed to support co-creation and co-learning between students and societal actors. Using a multiple case study design, eleven TLEs across research universities and universities of applied sciences were analysed. The findings reveal three types of TLEs: Consultancy TLEs (C-TLEs), where students address real-world problems posed by commissioners; Participatory TLEs (P-TLEs), where all participants are explicitly positioned as learners in co-creation processes; and Student-Led TLEs (SL-TLEs), where students initiate the challenge based on their intrinsic motivation and seek out relevant stakeholders. The pedagogical and design decisions made within each type were identified, focusing on how co-creation is facilitated across the phases of co-design, co-production, and co-dissemination, and to what extent co-learning is an explicit goal. While co-creation was often supported, co-learning—especially for stakeholders—was rarely intentionally designed for or assessed. P-TLEs were most explicit in embedding co-creation and co-learning in goals, activities, and support structures. Across cases, several enablers and barriers were identified, such as teacher roles, assessment alignment, use of physical spaces, and institutional embedding. Our findings highlight the importance of designing for “freedom within structure,” recognising learning surprises, and enabling reciprocal partnerships to strengthen TLE impact. The conclusion stresses that while TLEs hold great promise for transformative education and societal engagement, the concept and practice of co-learning remain underdeveloped. These findings call for more research and practical experimentation into supporting, assessing, and making visible the co-learning processes of all actors involved—students, teachers, and stakeholders alike—as a critical step toward realising the third mission of higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Higher education institutions increasingly acknowledge the importance of preparing students for navigating complex, uncertain and pressing societal issues. Grand societal challenges, such as the transition to cleaner energy production or the provision of good and affordable healthcare, ask for societal transformations that cannot be tackled by a single academic discipline or group of professionals. To address these complex problems and get closer to reaching sustainable development goals (SDGs), a transdisciplinary effort of scientists, engineers, governments, companies and citizens is needed (Khoo et al. 2019; Tejedor et al. 2017). It requires collaboration and co-creation of knowledge beyond the boundaries of one’s own discipline and practice to arrive at innovative and sustainable solutions (e.g., Fortuin et al. 2024; Knickel et al. 2019). Fruitful transdisciplinary collaboration is challenging, because different people have different and potentially conflicting disciplinary and societal backgrounds, interests, values and perspectives. To equip students with the necessary transdisciplinary skills and attitudes to operate in such complex and ambiguous environments, it is important for higher education institutions to design and implement learning environments that (1) expose students of different disciplines to open-ended challenges throughout the curriculum (Horn et al. 2024), (2) support students in the co-creation processes among themselves and with external stakeholders (MacLeod and van der Veen 2020; Stentoft 2017), and (3) allow not only students but all learners to become aware of and reflect on their learning with and from each other (Bakırlıoğlu and McMahon 2021; Mers et al. 2025). The latter is essential to guarantee that the impact of the co-creation processes does not remain within the classroom but flows directly into society (Lotz-Sisitka et al. 2015; Regeer et al. 2024).

A growing number of universities put emphasis on their role in addressing societal challenges, both through research and education, and incorporate this role as a central element in their missions (Compagnucci and Spigarelli 2020; Gutierrez et al. 2024). These universities do not consider themselves as the only, or privileged producers of knowledge, but aim to engage governments, companies, NGOs and citizens on an equal footing to co-produce the knowledge that is needed to tackle local, regional and global challenges (Oztel 2020; Regeer et al. 2024). Transdisciplinary approaches to education fit perfectly with these missions. They are inclusive and transcend disciplinary, professional and societal boundaries (Bernstein 2015; Khoo et al. 2019). In this, they go a step further than interdisciplinary approaches. These focus on knowledge co-creation across disciplinary boundaries (van den Beemt et al. 2020), while transdisciplinary approaches attempt to integrate professional, experiential, local, practical, indigenous and other forms of non-academic knowledge as well (O’Sullivan 2025; Pohl et al. 2021; Polk 2015). They aim to tackle problems for society, with society, including the people who are directly affected (Montuori 2013). In transdisciplinary education, differences in disciplinary backgrounds, interests, worldviews, power positions, and values, which often lead to conflicting perspectives on how societal challenges should be framed and tackled and on how responsibilities should be distributed (Fischer et al. 2011; Buchmüller et al. 2021), are not ignored or bracketed, but acknowledged and acted upon.

Embedding transdisciplinary education in the curricula and organisations of universities is challenging (Mers et al. 2025). Learning goals, activities, assessments and support are mostly not geared towards learning and co-creation across the boundaries of disciplinary and professional practices (Horn et al. 2023; van den Beemt et al. 2020). Transdisciplinary education is not a specific ingredient one can simply add to classes with a disciplinary – or interdisciplinary – focus. Nor is it just another research or design method, which can be included by expanding existing methodology courses. Transdisciplinary education is much more than training in transdisciplinary research or design skills (Kubisch et al. 2021). It is a different educational approach, engaging students in wicked, open-ended, real-life challenges, working in a reciprocal relation with external non-academic partners, co-creating innovative ideas, igniting change in society, and experiencing a transformative learning process in which a broad set of transdisciplinary competencies can be developed. It necessitates the ability and willingness to be open to a wide variety of perspectives (disciplinary, as well as non-academic perspectives) and see these differences as learning opportunities instead of hurdles in learning and innovation (Fortuin et al. 2024). For universities, this is a major educational innovation, requiring rethinking all elements of their learning environments. This does not imply that all has to start from scratch. It may be that because of earlier experiences with, for instance, project-based learning (Kokotsaki et al. 2016; MacLeod and van der Veen 2020), interdisciplinary education (van den Beemt et al. 2020), or work-integrated learning (Ferns et al. 2021; Ruskin and Bilous 2021), several elements are already in place. But transdisciplinary education has a different ambition than these more established approaches and asks for a holistic redesign or realignment of the learning environment.

How to effectively design and implement transdisciplinary education is a largely uncharted territory (Daneshpour and Kwegyir-Afful 2022; Horn et al. 2022). There are examples of transdisciplinary education described in literature (e.g., Dorst 2018; Fortuin and van Koppen 2016; Tembrevilla et al. 2023), but there are no clear best practices or dominant educational designs yet. At the same time, transdisciplinary initiatives are being implemented within many higher education institutions, for instance in the Netherlands, and teachers involved in these initiatives are learning quickly about what works and what does not work within their specific contexts. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the knowledge on the design and implementation of transdisciplinary learning environments, drawing on the experiences of a variety of teachers and other educational designers who pioneered transdisciplinary education within their institutions. How do they design these learning environments, enable and support students to co-create with stakeholders towards solutions and learning together, and what helps or hinders them to actualise transdisciplinary education in their programmes and organisations? Given the relatively early stage of development of transdisciplinary education and the variety of contexts in which it is currently being implemented (Exter et al. 2020), a large diversity in learning environments can be expected. In this exploratory study, we will show this variety, using a multiple case study design, and elicit certain patterns, which will be captured in a typology of transdisciplinary education and a number of common enablers and barriers related to the implementation of this educational approach.

Theoretical framework

Transdisciplinary learning environments

Transdisciplinary learning environments denote learning environments in which students learn by working on complex, open-ended, real-life societal problems with students from other disciplines and non-academic partners. A learning environment refers to a comprehensive constellation of aligned educational components like learning goals, teaching and learning activities, and assessment (Biggs 1996), including roles, physical and social constellations, support and timing (van den Akker 2003), together supporting the development of aspired learning processes and outcomes. Transdisciplinary learning is an umbrella term, sometimes used as such by higher education institutions, but sometimes also going under labels such as challenge-based learning (Doulougeri et al. 2024; Gallagher and Savage 2023), service learning (Salam et al. 2019), community-engaged learning (Comau et al. 2019), living labs (Tercanli and Jongbloed 2022), or entrepreneurial learning (Baggen et al. 2022). Common ground is that this education aims to prepare students for navigating (grand) societal challenges by equipping them with the knowledge, skills and attitude required to collaborate and co-create innovations in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world with a variety of stakeholders representing a diversity of perspectives (Bohm 2024).

Philipp and Schmohl (2023) mention a number of characteristics of learning environments that make transdisciplinary learning possible, including reduced teacher control, stimulation of creative processes, activation of participation, co-creation without hierarchy, embracing of failures, and ongoing feedback and reflection. Transdisciplinary learning goals go beyond the mere application of disciplinary knowledge and include the appreciation and utilisation of non-academic knowledge, collaboration and co-creation across disciplinary and societal boundaries, and the realisation of change in society (Fortuin et al. 2024; O’Sullivan 2025; Visscher et al. 2022). Transdisciplinary learning environments move beyond multi-disciplinary or interdisciplinary environments, especially in their integration of experiential and local knowledge, their relationship with non-academic stakeholders and their ambition to bring about change in real-life contexts (De Greef et al. 2017; Visscher et al. 2022). They vary in how intensive and reciprocal the exchange with non-academic partners is (O’Sullivan et al. 2025). On one end of the spectrum, stakeholders are involved as commissioners, clients or ‘challenge-owners’, who formulate a problem, invite students to develop an answer, which is in the end often presented to the stakeholder (Horn et al. 2023; Doulougeri et al., 2024). This is labelled by Mobjörk (2010) as ‘consulting transdisciplinarity’. This contrasts with ‘participatory transdisciplinarity’, at the other end of the spectrum, in which students and external actors participate and collaborate on equal terms in the full co-creation process. In practice, collaboration and co-creation processes are more nuanced (Arnstein 1996; O’Sullivan et al. 2025). For example, participation of stakeholders could concentrate in certain stages, like data collection, ideation, or decision-making. And students might experience more or less freedom to take the lead and redefine what stakeholders ask. Power dynamics also play an important role here, as has been shown in transdisciplinary research as well (e.g., Fritz and Meinherz 2020). Power differences exist between students, teachers and stakeholders, as well as between different stakeholder groups (Strumińska-Kutra and Scholl 2022). This makes creating a learning space in which students and various stakeholders see themselves as equal partners in co-creation a challenging and continuous balancing act (e.g., Doulougeri et al. 2024). Designing transdisciplinary learning environments thus requires critically considering the roles of students and stakeholders, and how they can collaborate and co-create in an equal, reciprocal way. Above that, this collaboration of students and stakeholders needs explicit scaffolding and reflection during the process (Fortuin et al. 2024; Horn et al. 2023; Knickel et al. 2019). As such, transdisciplinary learning adds a layer of complexity to multi- or interdisciplinary education, making designing and implementing transdisciplinary learning environments challenging (Visscher et al. 2022).

Co-creation and co-learning

Andrews and colleagues (2024) argue that impactful transdisciplinary work requires knowledge co-creation at different sides of and across the boundaries of academic and non-academic practices, i.e., participatory transdisciplinarity (Mobjörk 2010). Horn et al. (2023), building on the work of Mauser et al. (2013), specify these co-creation processes in transdisciplinary education by distinguishing between co-design, co-production, and co-dissemination. Co-design refers to collaboratively defining the project; co-production to collaborative working on the project, while co-dissemination refers to collaboratively being involved in developing follow-up activities for the project and/or activities to disseminate the outcomes to realise sustainable impact. Horn et al. (2023) found that students were always actively involved in the co-production phase, but less in the co-design and co-dissemination phase, limiting their learning opportunities and interactions with teachers and external stakeholders in these phases. Other studies (Akkerman 2011; Fortuin et al. 2024) showed that simply bringing a diverse set of people or perspectives together will not automatically lead to co-creation and/or learning across boundaries. Also, in the context of transdisciplinary research, Andrews and colleagues (2024) showed the importance of explicitly guiding transdisciplinary projects through several phases of boundary work. In transdisciplinary education, it is important that co-creation between students and stakeholders is enabled and supported throughout all phases.

While these co-creation processes are mostly geared towards generating new knowledge and ideas, often embedded in a product or solution to a problem, the intention of transdisciplinary learning environments is that co-creation leads to co-learning (Bhatta et al. 2025; Knickel et al. 2019). Co-learning can be viewed as participants’ learning with and from each other (Knickel et al. 2019), as well as learning from being confronted with other perspectives, which is inherent to transdisciplinary learning. This can entail learning from reflecting upon one’s own perspectives, and by crossing boundaries of all kinds of disciplinary, cultural and societal practices (Fortuin et al. 2024; Gulikers and Oonk 2019). This learning can happen within an individual as intrapersonal transformation (Fortuin et al. 2024) or develop as a shared new understanding within the team, which is also referred to as social learning (Knickel et al. 2019) or interpersonal transformation (Fortuin et al. 2024). In participatory transdisciplinary learning environments, this learning is not the privilege of students alone. Co-learning concerns students and external stakeholders (Reeves 2019; Merter 2024), and potentially teachers as well (Bakırlıoğlu and McMahon 2021).

Since in transdisciplinary projects, problems are complex, pathways and outcomes are uncertain, and participants have different backgrounds and starting points, one can argue that it is not possible nor desirable to try to completely predefine what should be learned by students and stakeholders (Bakırlıoğlu and McMahon 2021). Transdisciplinary learning entails engaging with constructive friction (Veltman et al. 2019), challenging oneself beyond the current comfort zone, and out-of-the-box thinking. In this line, Baggen et al. (2022) argue that transdisciplinary learning environments should allow for and explicitly engage participants in searching for learning surprises. This means that learners should be allowed and stimulated to learn different things, e.g., in terms of personal learning goals, and be supported to reflect on their actual learning outcomes, expected and unexpected ones. Jorre de St Jorre et al. (2021) furthered this idea by arguing that assessment practices should allow students to be different and show their distinctive talents (i.e., ‘distinctive assessment’). These ideas are challenging within an educational system where programmes have standardised learning objectives and standardised assessment procedures for all students. The learning of stakeholders is less bound by these regulations, but their actual learning often remains elusive. Horn et al. (2023) illuminated that evaluating the societal value of transdisciplinary projects and reflecting upon stakeholder learning was not a common practice. This suggests that paying attention to the learning of stakeholders, alongside the learning of students, often remains implicit in transdisciplinary learning environments.

Independent of the type of transdisciplinary learning environments that are intended and the kind of co-creation and co-learning that are aimed for, constructive alignment between all course elements is imperative in educational design and implementation (Biggs 1996; van den Akker 2003). An effective learning environment requires alignment of a comprehensive set of course elements such as goals, content, learning activities, roles, support, location, timing and assessment (Biggs 1996; Van den Akker 2003).

This study aims to explore how Transdisciplinary Learning Environments (TLEs) are designed for educational practice. More specifically, how teachers and educational designers design for co-creation and co-learning between students and external stakeholders in TLE. This aim leads to the first research question guiding this study:

(1a) What types of TLEs can be identified in higher educational practice?

(1b) What design decisions do teachers and educational designers make to enable and support co-creation and co-learning in these different TLEs?

Barriers and enablers

To be effectively implemented, more than just the design of the TLEs needs consideration. Innovative educational designs are to be embedded in educational organisations and ecosystems, with their own culture, ways of working, regulations and beliefs, which creates challenges for implementing TLEs in practice (Doulougeri et al. 2024; Sluijs et al. 2024). These challenges can occur at the classroom level, but also at the programme, institutional, or systemic level. Examples of challenges are, for instance, challenges that arise from the existence of disciplinary silos in educational institutions, and how they are organised and funded (Pelzer et al. 2024). While many higher education institutions aim to establish transdisciplinary learning environments, in practice these often remain monodisciplinary (Gallagher and Savage 2023) or multi-disciplinary, allowing students of different programmes to work alongside each other in a structured manner, but not actually integrating knowledge from different disciplines or from practice (Visscher et al. 2022). Also, current assessment systems, which often adhere to mainly cognitive and disciplinary learning outcomes, make embedding transdisciplinary learning environments within a curriculum difficult (Baggen et al., 2024; van den Beemt et al. 2020; Sluijs et al. 2024). Teachers may tend to overly pre-structure assignments and feel uneasy with guiding and assessing learning outside their expertise (Visscher-Voerman et al. 2019). Furthermore, in TLEs, teachers are required to go outside of their academic comfort zones and intensify connections to societal partners for the purpose of establishing long-term partnerships. Most teachers are not educated to do this and may lack the skills and inclination (Oonk et al. 2020; Plummer et al. 2022). Also, the belief systems and practices of students and teachers are challenged, opening up to learning across boundaries in TLEs (Veltman et al. 2022). For example, students are challenged to take a learning orientation instead of a task-oriented and result-oriented approach to learning. Exploring various perspectives should be seen as a learning opportunity, not as a waste of their time (Fortuin et al. 2024). As a final example, stakeholder involvement can be challenging. They have their own reasons for engaging in TLEs, and they may want their problem to be solved rather than to engage intensively with students in co-creation and co-learning. Aligning interests and expectations to optimise the learning experience for students and stakeholders is challenging (Membrillo-Hernández et al. 2021).

In response, educational institutions might have developed initiatives to overcome these barriers or enable the development of TLEs. For example, reconsidering teacher roles and competencies, teacher trainings, embedding TD learning in educational visions or changing assessment rules and regulations.

This leads to the following research question guiding this study:

(2) What barriers and enablers do teachers and educational designers encounter when implementing transdisciplinary learning environments?

Methodology

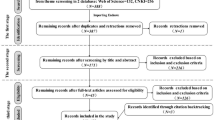

This study adopted an exploratory approach, using a multiple case study to lay bare how co-creation and co-learning between students and external partners were stimulated and supported in transdisciplinary learning environments, and what design decisions were underneath this. As our practical experience shows that embedding these student-stakeholder partnerships in higher education curricula is new and challenging, we chose an exploratory research approach to show what the current practice is. By doing this across eleven different institutions across the Netherlands, this approach shows a rich picture of what TLE’s currently look, why they are designed in the way they are, what challenges they encounter, and where options for improvement and development lie. This approach fits the focus and title of this special issue “Practice based research on interdisciplinary higher education” and is innovative in this field of research on inter- and transdisciplinary education and learning. A multiple case study is suitable as it provides an in-depth, context-sensitive analysis of real-world educational practices (Yin 2014). By examining multiple cases, patterns and variations in design decisions can be identified, as well as the barriers and enablers encountered, enhancing the transferability of findings.

This multiple case study comprises the first phase of a 4-year research project (because of anonymisation, the name and description of the project have been removed here).

Participants

In total, eleven empirical examples of transdisciplinary learning environments in Dutch Higher education were included in the case study. The cases were recruited via LinkedIn in the spring of 2023. We called for courses or a conglomerate of courses (e.g., a minor programme) that met the following criteria:

-

Students work on real, complex societal issues that stem from practice and have no clear solution.

-

Multiple perspectives (i.e., disciplines, stakeholders) are needed to reach a solution.

-

Students work in interdisciplinary groups.

-

Collaboration between students and external stakeholders was intended, allowing for both consultancy and participatory approaches.

-

The case has run at least 2 times (i.e., it is past the start-up phase).

-

The case was not represented in the ANONYMISED NAME-project.

The first call resulted in a list of 27 cases. Sixteen cases were excluded because they did not meet the above-mentioned inclusion criteria, or for other reasons (e.g., more internship-like constructions, students did not work in groups, multiple examples from the same institution, or the problems worked on were not open-ended and uncertain).

Ultimately, eleven cases were included that represented cases from Research Universities as well as Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS)Footnote 1, a variety of domains (e.g., technology/IT, health, social sciences, business/economics) and embedded versus more extracurricular courses. All cases intended to implement elements of transdisciplinary learning environments and met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows a short description of the eleven studied cases. The cases have been labelled A–K for anonymity purposes. From each case, a group of teachers and/or designers (between two and four people) who were involved in the design and implementation took part in the study.

Data collection

Documents

From all cases, documents were collected, like course guides, websites, articles on their learning environments, tools used within their learning environments, etc. In some cases, a lot of detailed materials (up to assessment formats) could be collected, in others, not much information in writing was available. In only one case (case A), teachers set up an evaluation of their TLE that was filled in by students and stakeholders, which was handed in as data.

Semi-structured interviews

For each case, one of the researchers held a semi-structured interview with a group of teachers and/or designers, in which these respondents were asked about the design and implementation of the transdisciplinary learning environment. The interview guide was developed based on the research questions. First, interviewees were asked for a generic overall description of the learning environment, its overall aim, and how students and stakeholders worked together and in what roles (research question 1a). After that, the questions elaborated on what design decisions were made regarding various course design elements (van den Akker 2003) in relation to co-creation and co-learning (research question 1b): the learning goals; the grouping of students (in terms of different disciplines and/or different educational levels); the learning activities regarding co-creation, explicitly addressing learning activities in the co-design, co-production, and co-dissemination phase, and how co-creation was supported or scaffolded throughout the TLE. Separate questions were asked for co-learning: exploring if and how co-learning of students and stakeholders was intended and designed for, and what students and stakeholders learned from each other in the eyes of the teachers/designers. Finally, the researchers asked what teachers and designers experienced to be enablers and barriers in designing and implementing co-creation (and co-learning if that was intended) (research question 2). All interviews were held online via MS Teams, which also allowed for – with informed consent - recording and transcribing the interview.

The study was done under the Ethical approval of Anonymised University, under case number 240085.

Data analysis

The cases were elaborately described in a descriptive meta-matrix (Miles and Huberman 1994) in Excel to make an extensive summary per case, primarily based on interview data. Document analysis was used to fill in the blanks and to support or elaborate findings of the interviews, for instance, regarding intended learning goals. For research question 1a and b, each case was first described in terms of student-stakeholder roles and the way of working with each other. This allowed the researchers to classify cases as representing a consultancy or a participatory approach. One code was inductively created to classify cases that were neither consultancy nor participatory transdisciplinary: student-led cases, in which the challenges to work on originated from the students, who also decided on the involvement of and interactions with stakeholders. After that, the cases were described in detail, following the interview scheme, in particular describing how the course design addressed co-creation (van den Akker 2003) (i.e., learning goals, pedagogy, learning activities, support/scaffolding of co-creation). The design of the learning goals and learning activities was further specified using the co-creation phases of Horn et al. (2023): co-design, co-production and co-dissemination. For co-learning, an Excel column was used to summarise per case what was reported about who was learning, what this learning entailed, and how this learning was designed for and supported. Also, the mentioned enablers and barriers were collected in one column (research question 2).

After describing the individual cases, a cross-case analysis was conducted in two steps. First, the authors collaboratively identified variations found within every design decision for co-creation and co-learning across the cases (i.e., learning goals, pedagogy, etc.). Second, using input from the first step, author 1 (JG) identified patterns between the design decisions and the three types of transdisciplinarity: consultancy, participatory and student-led. These identified patterns were discussed, elaborated and refined in discussion with authors 2 and 4 (AK and IV). Author 3 (KV) was involved as an auditor to review the interpretations being made in the cross-case analysis steps 1 and 2. In this way, the within and cross-case analyses were transparent and did justice to the eleven individual cases, while leveraging the findings to a higher level of abstraction that allowed for making the results transferable to other cases (Korstjens and Moser 2018).

Results

Types of TLEs and their student and stakeholder collaborations (research question 1a)

Five cases were classified as consultancy transdisciplinary learning environment (C-TLE) and four as participatory (P-TLE). The P-TLEs explicitly intended all partners to co-learn and assigned stakeholders the role of “learner”: “we learned that language is key in these learning environments. Therefore, we explicitly refer to everybody as a lab learner” (teacher, case F). In the C-TLE cases, teachers and designers did not explicitly report the intention for all partners to learn. In these cases, there was always a commissioner or challenge owner, and the focus of the TLE was on developing a solution or product for their problem. Two C-TLEs originated in practice (Case B and D), meaning that they were initiated by an external partner, often a professional community initiated by government or companies, in which the university became involved. Two of the P-TLEs were initially set up by a community (i.e., a professional or citizen community) together with the university. Overall, C-TLEs and P-TLEs seemed to involve different kinds of stakeholders. In C-TLEs, most partners represented companies or (local) government. In P-TLE, students worked more with communities, citizens or non-profit organisations.

Two cases could not be classified as either consultancy or participatory. They can be typified as “student-led”. These cases did not start with a problem or challenge from a societal partner. They explicitly intended to start from students’ intrinsic motivation (Case G) or impact capacity (Case I). Both TLEs had an overall framing in a grand societal or sustainability challenge (i.e., inequity or wide prosperity), within which students explored their interests, drivers and ambitions, “what impact do you want to make (in this region/own environment)” (Case I). After this, students were grouped based on their shared interests. These groups then explored how to translate their interests into a real-world problem within their own environment/region. They formulated a real-life case and were responsible for finding stakeholders relevant to this case. In these two cases, the roles of the stakeholders, the kind of stakeholders involved and how they were involved, and what they learned, were dependent on the problem and decisions made by the student groups. As a result, the role of the stakeholders varied: “the role of the stakeholder(s) depends on the group of students: Helpdesk, collaborator, co-learner, expert” (teacher case G). Table 2 summarises the design decisions of the three TLE constellations.

Design decisions regarding co-creation and co-learning (research question 1b)

The results below typify the three transdisciplinary learning environments constellations identified and how these can be described by the design decisions made in these three types.

-

1.

Consultancy Transdisciplinarity (C-TLEs) (Cases: B, C, D, E, J)

C-TLEs were found in three universities of applied sciences and in two combined initiatives from a research university, a university of applied sciences and a VET institution. In C-TLEs, external stakeholders, mostly acting as commissioners, provided the problem context and set the desired outcomes. In the two cases originating from professional communities, a knowledge broker engaged educational partners for each challenge. In these C-TLEs, students worked in interdisciplinary and multilevel groups (i.e., RU, UAS and VET students from different programmes). In the other C-TLEs, the intention was to work in interdisciplinary student groups, although this did not always work out in practice. In Case C, for instance, all participating students came from a social work or care education background.

As C-TLEs were geared towards finding a solution for commissioners’ problems, learning goals rarely referred to co-creation or co-learning. In four of the five C-TLEs, there were no transdisciplinary course-specific learning goals that all students had to meet. They entered the course with learning goals from their own educational programmes, which did not explicitly reflect co-creation or co-learning. Except for case C, in which “being able to respond to questions and needs of stakeholders” was stated as a learning goal in the course guide. Regarding the underlying pedagogies, the cases differed. Two cases used challenge-based learning, one research-driven education, one boundary crossing and interprofessional education, and one impact education. The cases had in common that they only loosely translated the pedagogies into learning activities, student or teacher roles, procedures or organisation. For example, the interviewees of the two challenge-based learning cases considered their learning environments to be open and organic, meaning that the process was not pre-structured by a strict methodology and evolved depending on student needs.

Regarding the learning activities for the three co-creation phases, patterns could be identified. In C-TLEs, projects were not co-designed by students and stakeholders. Although the problems were complex and open-ended in terms of solutions, they were largely predefined by the external partners. Student groups could tweak the problem a bit to align with their educational goals, make it researchable, and fit within their timeframe. Only in one C-TLE, explicit co-design activities included. The general problem and process was for all student groups the same: “doing a health scan in a community and designing an intervention for health promotion” (course guide). Each student group was assigned a different community, and the co-design activities related to contextualising the general problem together with this community.

Co-production refers to students and stakeholders collaboratively working on the problem throughout the process towards a solution or new idea. In three of the C-TLE cases the interviews nor the documents showed explicitly designed activities for co-production. In these cases, students were introduced to the main stakeholder at the start, after which further collaboration was up to the students. For example, in case E, students were expected to ask feedback from their commissioner, but this was not organised nor visible in the goals or assessment criteria. Two C-TLEs had explicitly designed learning activities for co-production. In case D, a kick-off, midterm and final presentation meeting was organised, in which feedback from the external partners was gathered. In case C, projects had an explicit procedure that required students to regularly check in with stakeholders. Regarding co-dissemination – or the follow-up of the projects – the C-TLEs focused mainly on the usefulness of the developed outcome for the commissioner. Interviewees of case J stressed the impact on the external company: Students needed to develop a product that was directly usable for the commissioner. Besides, three of the five C-TLEs employed an “estafette method” (i.e., relay race), meaning that the outcomes of one student cohort were intended to be the starting point for the next. However, this was not always successful, for instance, because the end results were of too low quality to follow up on, or because the stakeholders came up with new questions.

How was the co-creation process supported or scaffolded? The guidance structure of three of the five C-TLEs consisted of scheduled sessions in which student groups shared their experiences and challenges. In four of the five C-TLEs, support sessions took place at a physical location outside of the educational institutions (e.g., at the commissioner’s company, or in the learning community ‘hub’), though mostly not with external stakeholders being present. In these sessions, the teachers took the role of facilitator, except for case D, where an external knowledge broker facilitated. The support students received in these sessions mainly focused on the project outcomes. The knowledge broker in Case D stated that “support on the educational programme specific learning goals needs to be arranged by the teachers of the different programmes or educational institutions. They are responsible for reaching or assessing these programme specific learning goals”. The extent and form of this teacher support differed largely between education partners.

Regarding the co-learning of students and stakeholders, it becomes clear that C-TLEs did not explicitly aim or organise for stakeholder learning. This learning could be related to the co-creation process or the final products of the students, but this was not made explicit. Regarding the products, several C-TLE interviewees downplayed the potential. Projects often resulted in ‘half-products’ or ‘low quality’ products for stakeholders, and one interviewee stressed that their stakeholders were prepared for this beforehand: “They know that we cannot promise that [high quality products], they need to also want to take the deep dive, that is what innovation means”. Still, stakeholder involvement in these C-TLEs persists, suggesting that they are considered valuable to engage in. Interviewees reported that collaboratively working on real-life challenges proved insightful, offering stakeholders a “fresh and up-to-date look at the problem”. Regarding the learning of students, all interviewed teachers, without exception, considered these learning environments to provide a powerful and innovative learning experience for students. However, they did provide only fragmented evidence for this. In case C, “students learned to make contact with professionals and community”, while in case B, the interviewee reported that “in the beginning the discussions are technical and practical. Later on, when various companies get involved, students start to discuss the expertise they need from each other. Gradually, students start to really learn from each other”. In one case, teachers seemed genuinely surprised about the large number of students who followed their transdisciplinary course, while they could also choose courses deepening their disciplinary domain. They perceived this as a sign that – apparently – students regard these courses as highly valuable for their learning.

In summary, C-TLEs are problem-driven settings in which external stakeholders act as commissioners, providing real-world challenges for students to address, with limited emphasis on co-creation or co-learning and varying degrees of pedagogical structure and stakeholder involvement throughout the process.

-

2.

Participatory Transdisciplinary Learning Environments (P-TLEs) (A-F-H-K)

P-TLEs were found in a university of applied sciences, two research universities and a collaboration of a research university, university of applied sciences and VET. In all P-TLEs, students worked in interdisciplinary groups. The diversity of involved disciplines was high in three of the four P-TLEs, as these were open to several educational programmes. Case H involved only two programmes, which were interdisciplinary in themselves (interdisciplinary social studies and urban studies).

All P-TLEs aimed at making a positive societal impact and they had learning goals related to co-creation, though not always to all phases. Only case K had explicit learning goals regarding co-design: “together with the community partners clearly define the societal problem” (K). Co-production learning goals were present in course document of all cases, for example “undertake co-creation processes and develop and facilitate inter- and transdisciplinary teams” (H)” and “develop an intervention in co-creation with the community” (K). Also, co-dissemination learning goals were part of all P-TLEs, in terms of “making a (sustainable) impact in the region/community” (A, F, H, K). Two P-TLEs had explicit learning goals referring to students’ personal and professional development (e.g., “learners (proactively) manage their professional performance, development, and growth by reflecting on their actions, using feedback” (F)). In Case F, teachers explicitly mentioned that students needed to add and develop personal learning goals.

Regarding pedagogy, the P-TLEs were diverse, including design thinking, boundary crossing, place-based learning, and community-engaged learning. Compared to the C-TLEs, the pedagogies in the P-TLEs were more embedded within the learning environment in terms of designed structures, activities, feedback sessions or assessment structures. For example, several cases structured the co-creation process along the design thinking phases or using a predefined assessment rubric on boundary crossing (Case A). Case F had the most structured and elaborated pedagogy. It had four “climbs” building on the design thinking phases, with activities structured using the design canvas tool (Smeenk 2023), formative assessment, intermediate products and feedback rounds, and a well-defined assessment procedure. The learning goals and assessment criteria were process-oriented and content/domain independent, allowing for different learning trajectories for different students, as was shown in the assessment guide: “The lab learner involves the lab context, their own values, and future aspirations in the learning goals and reflects on the (possibilities for) integration thereof”.

The P-TLEs differed in how they designed co-creation learning activities. Regarding co-design, cases H and K had a comparable setup, in which students went into the community to specify and clearly define the problem for which an intervention was to be developed. In case K, students received a challenge beforehand, but this was quite open. They had to go into a self-chosen community to explore and co-design a challenge to work on. All P-TLEs are intended for co-production and co-dissemination. However, in only half of the cases, explicit learning activities were designed to engage students and stakeholders in the co-production process or co-dissemination process. For example, both these cases had formalised the seeking of feedback from stakeholders. Case F organised regular “jam sessions” at their living lab in which students and stakeholders engaged in co-creation activities. In the two other cases, students were also expected to co-create with external stakeholders, but it was up to the students how to do this. Regarding co-dissemination, case H was the most established. This case is built on a long-term partnership with its own website. Students had to translate their project results into a post for this website, making them concrete for the community. Three of the four P-TLEs aimed to work towards follow-up projects (“the estafette method”). This was best embedded in case H, where student groups were explicitly involved in the start-up of a following student group, where they transferred their findings.

In comparison to C-TLEs, the P-TLEs showed other types of support or scaffolding. Where the C-TLE’s coaching sessions focused primarily on the product, most P-TLEs focused on connecting and co-creating with stakeholders and dealing with the open-endedness and complexity of the problem. This was done in coaching sessions and additional workshops, for instance, on participatory research methods or on disseminating project results to the local community. In two cases, interviewees and course documents explicitly mentioned scaffolding students toward specific learning goals such as “exploring perspectives” and “taking ownership”. The guidance structure differed among the four P-TLEs. Where two P-TLEs pre-structured and scheduled formative assessments or informal feedback dialogues, one case was fully on-demand, meaning that coaching was available upon the student’s request. One P-TLE had a mixed approach, with a scheduled coaching session every week, and a teacher “monitoring from a distance and providing direction when needed” (case A, teacher). Regarding roles, all P-TLEs engaged external stakeholders in coaching or supporting students by giving feedback, participating in a professional advisory board, or coaching students upon their request.

Without exception, the P-TLEs aimed at co-learning, intending both students and stakeholders to learn from the endeavour. However, only in case A stakeholder learning was evaluated, to some extent, by asking stakeholders what engaging in the P-TLE brought to them. Reporting on the evaluation responses, interviewees mentioned stakeholders valued that “students were able to identify the questions behind the question” and provided new perspectives on their problems. Regarding student learning, three of the four P-TLEs had explicit learning goals related to co-learning in their course document. In these cases, students were required to show what they learned from the participatory process, boundary crossing and other perspectives. Interviewees from all cases reported that students experienced the learning environment as engaging, powerful, or something of the like. Like with the C-TLEs, the interviewees gave limited concrete evidence of specific student or stakeholder learning.

In summary, Participatory Transdisciplinary Learning Environments (P-TLEs) are purposefully structured around co-creation with communities to achieve societal impact. Students work in interdisciplinary groups, engage in open-ended, participatory processes supported by embedded pedagogies and learning goals that emphasise co-design, co-production, and co-dissemination. Co-learning of both students and stakeholders is intended, though not explicitly designed for.

-

3.

Student-led Transdisciplinary Learning Environments (SL-TLEs) (Cases G and I)

This third profile of TLEs was found in two cases, one at a university of applied sciences and one at a research university. In these cases, there was a longer start-up period, of about two weeks, in which students undertook activities to explore their motivation, interests, drivers and impact ambitions within the broader theme of the TLE (i.e inequity or wide prosperity). Based on this exploration, interdisciplinary groups were formed. The groups jointly defined their challenge, after which students looked for stakeholders relevant to their challenge. Thus, students were in the lead in defining a problem and identifying external stakeholders to collaborate with. Regarding this way of working, a designer and teacher of case I mentioned: “keeping the students together for the first two weeks and guiding them with all kinds of activities in their personal development and motives makes the students become a real group who will help each other much more and automatically during the rest of their project”.

The overarching aim of these SL-TLEs was to let students develop their impact capacity and/or explore their intrinsic motivations and drivers. This was shown in learning goals such as “the ability to engage as a real person (authentic being) in real-world urgencies and drive change for the good” (Case I, course documents). Both SL-TLEs also had explicit learning goals on co-creation with stakeholders, such as “the ability to participate with stakeholders in the process of learning and development”, or “engaging with communities”. A teacher of case G stressed during the interview that the learning goals necessitate collaboration, engagement, co-creation and making an impact in the community.

Neither SL-TLEs adhered to a particular pedagogical approach. Regarding the design choices for co-creation activities (co-design, co-production and co-dissemination), the SL-TLEs did not design activities for student-stakeholder co-creation. As these SL-TLEs strongly intended to build on students’ motivation and initiative, teachers did not want to intervene in this process. This led to a dilemma described by a teacher of Case G: “we experience a dilemma between aiming at more stakeholder involvement while on the other hand wanting to start from the intrinsic motivation of students. Can we for example arrange speed-dating sessions between students and stakeholders, or are we then taking over the process from students?”. Thus, while the learning goals of both SL-TLEs necessitated stakeholder engagement and co-creation, it was fully up to the students how to actualise this.

Regarding support or scaffolding, both SL-TLEs strongly focused on coaching the process, engaging students in the wickedness of the challenge, and students’ ownership. For example, “the focal point of <case I> is to nurture an understanding of the underlying problems, rather than hastily pursuing solutions” (course document case I). In Case I, each student group had two teachers to coach them (roles), developing multiple ties between students and coaches. In both cases, students had to take ownership of their coaching (roles). In case G, this was quite organic; in case I, this was more organised. Coaching sessions were planned twice a week: Every Monday, students were asked to identify coaching questions within their group, as input for sessions on Tuesday and Thursday. Next to the coaching, both SL-TLEs also organised other didactical activities such as workshops on exploring a diversity of perspectives, or doing participatory research.

The SL-TLEs strongly focused on students’ intrinsic motivation and learning, and did not explicitly aim for co-learning of stakeholders, although having an impact on society was considered key. Interviewees of both SL-TLEs stressed the impact of the learning experience on students, especially on their personal development. Teachers of case G specified that their SL-TLE “has a lasting impact on students, who really learn how to work from their own drivers and motivation, from their own values. And with that also really want to make an impact in society”.

To summarise, SL-TLEs place students at the centre of the learning process, granting them full ownership over defining societal challenges, engaging stakeholders, and shaping co-creation processes, with a strong emphasis on personal motivation, value-driven impact, and process-oriented coaching rather than on predefined pedagogical or co-creation structures.

Enablers and barriers regarding co-learning and co-creation (research question 2)

All interviewees reported designing and implementing transdisciplinary learning environments as rewarding – in terms of what it does for students and their learning – yet challenging. This result section shows expressed enablers and barriers clustered in five themes. These touch upon various levels within the educational institutions, like the personal level, the course level, the physical, the organisational or the curriculum level.

Beliefs, roles, role perception

Several interviewees reported that students, teachers and stakeholders needed to adapt to be able to engage on an equal level as learners in a co-creation process. They indicated that students tended to fall back into a passive or consultant role, that stakeholders were inclined to take on a commissioner role, and teachers tended to “slip into teacher mode, where we tell students what to do. While the relationship is reciprocal and equal” (case K). Approaching students as professionals was reported to be an enabler. In addition, interviewees of case C noted that students of different study programmes did not always see each other as equal contributors, and they stressed the importance of investing in equity in the interdisciplinary student groups and making use of everybody’s talent.

Relatedly, interviewees in all cases mentioned the barrier of teachers’ (in)ability to design, implement or coach in these types of learning environments. Some teachers were not used to or willing to adopt a coaching role and engage in the open-ended, ambiguous and uncertain co-creation across (disciplinary) perspectives. These teachers tended to fall back into “old behaviour”, focusing on developing or applying disciplinary knowledge instead of focusing on the process of co-creation with students and external partners.

A reported enabler was teachers taking an outward-looking role: connecting to stakeholders and investing in (long-term) partnerships, approaching learning also from the perspective of external partners, and building bridges between students and partners. A barrier in this respect was that this outward-looking teacher role was not supported, recognised and rewarded by educational institutions.

Language and wording

In several cases, respondents were considerate about language and wording. Speaking each other’s language helps better understand each other. In order to stimulate participatory rather than consultancy transdisciplinarity, teachers in case F explicitly used new terms to reframe roles: “We call everybody in the learning environment (students, external stakeholders as well as teachers) a Lab Learner. This stresses that everybody is learning” and “we changed our “presentation sessions” to “Jam Sessions”. This supported collective brainstorming and discussing ideas by students and stakeholders, rather than students presenting their ideas to the stakeholders.

Goals and assessment

Assessment of students was reported to be challenging in many cases. Case A interviewees reported the difficulty of assessing all students in the same way, as they had different disciplinary backgrounds and educational levels. Students entering the learning environment with (programme-specific) learning goals – which was mostly the case in C-TLEs - hindered co-creation and co-learning, as these students focused on their disciplinary learning objectives. Having transdisciplinary course-specific learning goals held for all students – as seen in the P-TLEs and SL-TLEs - was regarded as an enabler for co-creation and assessment thereof. In case F, clear structures with various formative and feedback moments, also involving external stakeholders, proved an enabler of co-learning processes.

A physical space outside of the educational institution

Having a physical space outside of the educational institution was mentioned by three P-TLE cases as helping the co-creation process and creative thinking. In three C-TLEs, most activities also happened at an external physical location, but designers of these cases did not explicitly report this as an enabler. Teachers of case G reported that having such a physical space was an important “wish for the future” as they experienced not having this space as hampering the co-creation process.

Embedding into different curricula

Most cases were not connected to one specific educational programme. They were either extracurricular or minors and could be followed by students of various programmes. Connecting these TLEs to the various educational programmes was reported as challenging. Finding the right educational programmes required for a project, fitting the diverse timeframes or connecting to their diverse learning goals. Only one case (case J) was an institution-wide, top-down initiative, in which all programmes were (eventually) expected to be involved in any of the developed transdisciplinary semester courses. While this top-down approach was seen as an enabler by the interviewees, having resulted in already nineteen programmes participating, it was regarded to be a barrier as well. In this initiative, the focus was on developing partnerships, defining topics within four strategic themes, and connecting them to a wide range of semester courses. At the same time, there were few explicit guidelines for design decisions, and the design of the courses was left up to the respective teachers, leading to a wide variety and a lot of reported struggles with fostering and assessing co-creation and co-learning across the involved disciplinary programmes. Interviewees of two other cases reported that their initial extracurricular initiative needed to be “taken up as a minor” by educational programmes in order to remain alive (because extracurricular activities were not financed after a few years). Being dependent on programmes for financing the learning environment can threaten co-learning and co-creation in a TLE. For example, case G was only taken up as a minor by two programmes, resulting in fewer interdisciplinary student groups. In case I, various concessions were made to the open, creative, student-driven process, as the educational system could not deal with these uncertainties.

Long-term partnerships

Investing in long-term partnerships is seen as an enabler. Building trust, not overasking professionals, creating commitment and working on challenges that everybody feels an urgency for were mentioned in this respect. In case I there were experiences with both profit partners and non-profit partners. They experienced working with non-profit partners as more fruitful, as they were driven by values that connected more easily to students, while economic value was more difficult for these students. The issue of delivering results/products that were of too low quality for partners to use directly was mentioned as a barrier in several other cases. Several respondents mentioned (the wish) to work with an estafette method – in which student groups build on each other’s work – for fostering these long-term partnerships, but respondents of only one case reported this to be successful.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore how Transdisciplinary Learning Environments (TLEs) are designed for educational practice. Education that intends to educate students to navigate wicked societal and sustainability challenges in interdisciplinary student groups and in collaboration with non-academic partners (O’Sullivan 2025). Therefore, we conducted a multiple case study with eleven cases to identify the types of TLEs found in Dutch Higher Education and the design decisions that teachers or educational designers made to enable and support co-creation and co-learning between students and external stakeholders within these TLE types (Research question 1a/b). Additionally, enablers and barriers for implementing TLEs for co-creation and co-learning in TLEs in Higher Education were explored (Research question 2).

Three types of TLEs

While the design of a TLE clearly depends on the particular context, the eleven reviewed cases could be clustered in three types of TLEs: Consultancy (C-TLEs; five cases); Participatory (P-TLEs four cases) and Student-Led (SL-TLEs; two cases). Consultancy and participatory types were expected based on TD literature (Mobjörk 2010), while the student-led type was inductively identified. These three types represented a diverse constellation of design decisions concerning co-creation and co-learning between students and stakeholders. In short,

-

C-TLEs are problem-driven settings where external stakeholders commission real-world challenges to students, with limited emphasis on co-creation or co-learning and varying degrees of pedagogical and stakeholder engagement.

-

P-TLEs emphasise structured co-creation and co-learning with communities, involving students in interdisciplinary, participatory processes aimed at societal impact, supported by embedded pedagogies and co-design principles.

-

SL-TLEs centre on student agency, with students defining challenges, engaging stakeholders, and driving co-creation based on personal motivation and values, guided by process-oriented coaching rather than predefined structures.

In the introduction, it was argued that to really deal with grand societal and sustainability challenges and to make a sustainable impact in society, a participatory approach in which all partners engage in a mutual, equal and reciprocal co-creation and co-learning process might be required (Andrews et al. 2024). In practice, this was seen in only four cases. This finding can be interpreted as indicating that, from a rich selection of TLEs in the Netherlands, fewer than half of the cases were being developed in line with the ideal model. On the other hand, one may question whether this should be considered problematic, as each type can contribute to the students’ learning journey in its own distinct way. All types have their value in a curriculum that intends to foster students’ capabilities to navigate societal and sustainability challenges. The C-TLEs allow students to engage with real-life, authentic challenges from a non-academic – often business – partner in an out-of-the-university setting. Students co-create in an interdisciplinary and sometimes multilevel group a real-life and relevant societal solution. As such, they engage in processes key to transdisciplinary learning: boundary crossing, knowledge integration and actionable knowledge creation (Fortuin et al. 2024; O’Sullivan 2025). This experience relates to all dimensions of authentic learning (Gulikers et al. 2004) and connects to the educational concept of “challenge-based learning” (van den Beemt et al. 2022; Doulougeri et al. 2024), which is found to stimulate students’ learning, competency development and motivation (Gulikers et al. 2005; Gulikers et al. 2006). The SL-TLEs are grounded in exploring students’ intrinsic drivers, taking ownership and impact capacity. This might be important for students identifying their own identity and becoming more aware of their own perspectives and the roles they want to take in navigating societal challenges.

If the intention of the TLE is to really engage in transdisciplinary co-learning and co-creating innovative, feasible practices for society, then a P-TLE seems most fit (Andrews et al. 2024). In previous research, Baggen et al. (2024) explored the differences and values of in-curricular versus extracurricular TLEs. They found that both had their own challenges and values, though extracurricular TLEs seemed to allow for more engagement with uncertainty and co-creation with external partners, and as such, strengthened the participatory nature. In our study, indeed, respondents of various P-TLEs and SL-TLEs argued that having to become part of the curriculum (i.e., in-curriculum) required doing concessions to the participatory, out-of-the-box, uncertain co-creation process. Thus, designing and implementing P-TLEs within a higher education curriculum, without losing typical transdisciplinary values, might be the most challenging endeavour. Still, C-TLEs, SL-TLEs and inter- and extracurricular P-TLEs might all have their own role in students’ learning journeys towards change agents navigating wicked societal challenges in co-creation with others.

Designing for co-creation

The four P-TLEs found in this study were most explicit in their pedagogies and design decisions for enabling and supporting co-creation between students and stakeholders. This is in line with previous studies, which also show that engaging students and stakeholders in co-creation requires explicit instruction, learning activities and teacher supporting strategies (Bohm 2024; Fortuin et al. 2024; Veltman et al. 2019; Veltman et al. 2022; Tassone et al. 2022). Veltman and colleagues (2019) stress the importance of explicitly engaging all learners in the wickedness of the challenge and taking time to explore diverse perspectives. Tassone et al. 2022, supported by the recent work of Bohm (2024), identified an important pedagogical enabler for fostering learning in transdisciplinary and uncertain learning environments: balancing between an emancipatory pedagogy stressing openness, student autonomy and empowerment versus instrumental pedagogy stressing clear guidelines, procedures and formats. We would like to frame this as creating “freedom and autonomy within clear boundaries”. Or put it the other way around: Having a structure and clear boundaries enables maximum freedom and autonomy for all stakeholders. Our study, supported by the TLE work of Sluijs and colleagues (2025), suggests that the design thinking phases are helpful in this respect.

Furthermore, explicitly challenging traditional roles and beliefs seems imperative to create a space for equal and reciprocal co-creation required in a P-TLE. The P-TLE interviewees reported the necessity of coaching students and training teachers in this. All partners tend to fall back on traditional behaviours and roles in terms of looking for the right answer, students taking the passive and executing role, teachers taking the expert role, and stakeholders not taking on the role of learner. Also, institutional or disciplinary silos inhibit co-creating across practices. Thus, creating a space for real equality and reciprocity as a basis for actual co-creation seems challenging and requires explicitly considering long-held practices, roles and power relations (Strumińska-Kutra and Scholl 2022). This also stresses the necessity of building long-term partnerships, which was reported to be an enabler in our study.

Several additional enablers were found in our study that support these co-creation processes: having an external physical location to learn and work together; carefully considering the language used in the TLE in terms of how to address the various partners (i.e., all learners) or frame the co-creation sessions; having TD course overarching learning goals that explicate co-creation and that are the same for all students, instead of working with programme specific – disciplinary – learning goals and assessments, and working with non-profit partners driven by values or sustainable impact. Also, compared to the previous TLE cases reviewed by Horn et al. (2023), our cases showed substantially more attention to co-dissemination. Many of the cases were driven by either wanting to make a positive impact or to stimulate students to find their personal drive and realise personal impact. Explicitly stimulating students and stakeholders to think about the kind of impact they intend to make, and what they can do to make this impact sustainable after the end of their current project, also seems to support the co-creation process.

One final crucial challenge in designing TLEs is that of constructive alignment. Obviously, constructive alignment is inherent and key to proper educational design (Biggs 1996; van den Akker 2003). However, we argue that constructive alignment has additional difficulties in TLEs. As is inherent to wicked problems, the learning processes and outcomes of a TLE cannot be fully predefined, which is challenging for predefining learning goals and assessments (see also Sluijs et al. 2024). Moreover, the P-TLEs stressed that to foster co-creation, TLE overarching learning goals and assessment are required that focus primarily on the process and learning from other perspectives, instead of on disciplinary knowledge development or application. Baggen et al. (2022) argue that these kinds of learning environments should allow for learning surprises, which means that unexpected learning should be allowed and recognised. Finally, in TLEs, students from different educational programmes and sometimes different educational levels collaborate. These students enter the TLE with diverse backgrounds and are therefore also likely to contribute differently and to learn different things. Thus, we argue that constructive alignment in TLEs needs to be reconceptualised in a way that learning goals and assessment allow for this openness, uncertainty, learning surprises and differences between students (Jorre de St Jorre et al. 2021; Visscher-Voerman et al. 2025).

Going beyond co-creation: stimulating co-learning

Whereas all cases were selected for having intentional collaboration between students and external stakeholders, this study showed that co-learning remained largely implicit across the eleven reviewed cases. Results showed only a few indications of learning from each other (e.g., stakeholders reporting that students offer them a fresh, up-to-date perspective on the challenge) and even fewer indications of learning with each other (e.g., stakeholders who reported on experiencing the learning with students as a professionalisation). While all P-TLEs explicitly aimed to foster learning for all partners involved, other cases did not intend to foster the learning of stakeholders explicitly, even questioning whether stakeholder learning is the responsibility of an educational initiative. This is an interesting discussion from the perspective of the third mission of universities (Compagnucci and Spigarelli 2020). If universities truly aim to address major societal and sustainability challenges (challenges that require co-creation across diverse practices), then it becomes essential to ask whether the learning of all involved partners is not only crucial for innovation, but also for ensuring feasible and lasting implementation within society.

The respondents of all cases – independent of their origin, aim, and results - were largely positive about the transdisciplinary initiative. This positivity was evident, even in those cases where resulting products were reported to be of “low quality” or “half-products”. Thus, these TLEs probably had an added value for all involved that remains rather implicit or is not tangible. The implicitness of the transdisciplinary co-learning processes was also found in other studies (Knickel et al. 2019; Plummer et al. 2022). In response, Knickel and colleagues recently developed a reflective framework for evaluating and reflecting on the learning and collaboration processes in transdisciplinary settings. Studies on TD learning stress the importance of making learning – and learning surprises - explicit (Philipp and Schmohl 2023) through reflective activities and feedback dialogues (Philipp and Schmohl 2023; van Rijnsoever et al. 2023). Surprisingly, the reviewed documents and interviews did only marginally illuminate information on these kinds of (reflective, feedback, evaluative or learning surprises) practices.

On top of this, many cases discussed the challenge of actually grasping learning in their TLE, for students but also for stakeholders. How do we grasp the learning outcomes or impact of TLEs? Assessment was often mentioned to be one of the most challenging parts of TLEs, as also found in previous studies (e.g., Doulougeri et al. 2024; van Rijnsoever et al. 2023). Several cases even mentioned assessment practices to inhibit co-creation and co-learning. Thus, while it is a limitation of our study that we did not consider students’ assessments or reflection reports, nor ask students and stakeholders themselves about their learning, it can be questioned to what extent the used assessments really grasp students’ transdisciplinary (co-)learning. Moreover, only one case (case A) undertook an evaluation with stakeholders, getting a glimpse of the perceived effects of the TLE on stakeholders’ learning. Future research on assessment in TLEs seems imperative. How can assessments be used in such a way that they support, explicate or visualise and acknowledge student and stakeholder learning in TLEs? This requires a reconsideration of the why, what and how of assessment and assessment quality (Gulikers 2022).

Practical and theoretical relevance

This empirical study on TLEs offers practical as well as theoretical insights. First, the three types of TLEs found in the study provide a framework that can guide future educational initiatives. These three types of TLEs, their aims and design decisions, can support teachers and designers to make more informed decisions on the why, what and how of transdisciplinary education they intend to design. Second, this study enriches the theoretical framework surrounding transdisciplinary education by providing empirical evidence of how various design decisions impact the implementation, and what are evident barriers or enablers for co-creation and co-learning. It, for example, contributes to understanding the dynamics between learning goals, learning activities, pedagogy and stakeholder involvement within a transdisciplinary context.

This study has shown -in line with other studies- that fostering co-learning within TLEs is still underexposed. One could wonder why the design for, support, and evaluation of co-learning receives so little attention in practice. Apparently, evidence-informed research insights and practical knowledge on co-learning is lacking. We need a more thorough conceptualisation of co-learning, situated in a context of co-creation by multiple stakeholders with different backgrounds, knowledge and skills, and perspectives, acknowledging the interplay between individual and collective learning. And we argue for studies in which teachers actively experiment with supporting co-learning of all learners, including stakeholders, as a key step forward in the design and implementation of TLEs, educating students for their future and contributing to universities’ third mission of being societally engaged and actually contributing to global societal and sustainability challenges (Compagnucci and Spigarelli 2020).

In summary, the current study not only offers practical guidance for educators and institutions but also contributes valuable insights to the theoretical discourse on transdisciplinary education and detected further areas for designing and studying transdisciplinary learning environments.

Data availability

This study draws on qualitative data (e.g., interviews, course documents) collected within specific educational programmes and institutions. Due to the nature of these materials, full anonymity cannot be guaranteed. Moreover, the informed consent obtained from participants (see “Ethical Statement” section) explicitly restricted data sharing beyond the research team, permitting only anonymised reporting at the case level. Consequently, the underlying data cannot be made publicly available. The processed data can be requested and obtained via the corresponding author [Judith.gulikers@wur.nl]. The interview guide is added as supplementary material (in Dutch).

Notes

UAS stands for University of Applied Sciences. These are four year programmes at EQF level 6, bachelor level. In the Netherlands Research Universities (“RU” at EQF level 6 and 7) and Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) together make up the “Higher Education” offer. VET programmes (Vocational Education and Training) in this study represent EQF level 4.

References

Akkerman SF (2011) Learning at boundaries. Int J Educ Res 50(1):21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.005

Andrews LM, Munaretto S, Mees HLP, Driessen PPJ (2024) Conceptualising boundary work activities to enhance credible, salient and legitimate knowledge in sustainability transdisciplinary research projects. Environ Sci Policy 155:103722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103722

Baggen Y, Lans T, Gulikers J (2022) Making entrepreneurship education available to all: design principles for educational programs stimulating an entrepreneurial mindset. Entrep Educ Pedagog 5(3):347–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420988517

Baggen Y, Tho C, Gulikers J, Tassone VC, Wesselink R (2024) Examining the potential of in- and extra-curricular challenge-based learning in higher education: a Delphi study. Innov Educ Teach Int https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2024.2417798

Bakırlıoğlu Y, McMahon M (2021) Co-learning for sustainable design: the case of a circular design collaborative project in Ireland. J Clean Prod 279:123474

van den Beemt A et al. (2020) Interdisciplinary engineering education: a review of vision, teaching, and support. J Eng Educ 109(3):508–555. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20347

van den Beemt A, van de Watering G, Bots M (2022) Conceptualising variety in challenge-based learning in higher education: the CBL-compass. Euro J Eng Educ 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2022.2078181

Bernstein JH (2015) Transdisciplinarity: a review of its origins. development, and current issues. J Res Pract 11(1):1–20

Bhatta A, Vreugdenhil H, Slinger J (2025) Harvesting living labs outcomes through learning pathways. Curr Res Environ Sustain 9:100277

Biggs J (1996) Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Int J High Educ Res 32:347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871