Abstract

Countries around the world are making unremitting efforts to align agricultural practices more harmoniously with the ecological environment. In China, smallholder farmers are the primary group practicing sustainable agriculture, yet their participation remains low. However, few studies have focused on the impeding factors stemming from inadequate socio-cultural conditions and possible negative emotions accompanying behavioral implementation. This study investigates the role of behavioral costs and emotional exhaustion in the intention to recycle agricultural wastes (AWs). It employed a sample of 902 Chinese farmers and the partial least squares structural equation model for empirical testing. The results are as follows. First, behavioral costs constitute obstacles stressors causing psychological stress to farmers, leading to emotional exhaustion and negative behavioral intentions to agricultural wastes recycling. For pesticide packages and mulch film, perceived effort and time costs significantly exhaust farmers’ emotional resources. Second, behavioral costs are significant antecedents of perceived behavioral control. Economic and effort costs are key factors that result in low perceived behavioral control in straw recycling. Third, awareness of consequences significantly enhances environmental attitudes or reduces emotional exhaustion, which in turn triggers recycling behavior for all types of AWs. Fourth, rational, ethical, and emotional psychological factors influence behavioral intentions differentially across AWs that have different behavioral costs. Interpersonal interactions effectively activate intrinsic moral and foster positive behavior in crop straw recycling. Grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Normative Theory of Values and Beliefs, and the Resource Conservation Theory, while incorporating behavioral costs and emotional exhaustion, an integrative framework encompassing rationality, morality, and emotions was constructed. The study reveals external barriers and implicit psychological obstacles to farmers’ participation in AWs recycling. The results suggest that reducing behavioral cost barriers and individual sensitivity to private capital losses are more effective ways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To meet the food needs of a growing global population, modern agricultural production is increasingly dependent on the use of chemical products such as fertilizers, pesticides and mulch (Xue et al. 2021; Sharma et al. 2020). This dependence has also been accompanied by a significant increase in plant residues (Singh and Sidhu 2014). The ecological development of agriculture is a key issue and is an important component in achieving sustainable development goals (Yin et al. 2024). Agricultural waste is generally defined as the unavoidable byproducts generated from agrarian activities (Hsu 2021; Shahni et al. 2024), comprising animal waste, food processing waste, crop waste, as well as hazardous and toxic agricultural waste (Obi et al. 2016). Most countries in the world, including China, India, Italy, and British, are facing serious challenges posed by large amounts of agricultural wastes (AWs) (Tripathi et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018). The improper management of AWs not only jeopardizes rural socio-ecological systems by undermining habitat integrity, impeding sustainable agricultural transitions, and exacerbating environmental health risks for farming communities (Kadhim et al. 2022), but also leads to the waste of valuable biomass resources (Shahni et al. 2024). Such mismanagement has potentially harmful effects on human health and can even directly endanger both animal and plant life (Obi et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2021). Thus, there exists an urgent need to devise strategies for the sustainable management and utilization of AWs, while ensuring agricultural sustainability as well as food and health security.

China is the largest producer of AWs (Koul et al. 2022). However, huge quantities of AWs are improperly recycled or utilized and enter the natural environment through indiscriminate disposal, direct landfill, on-site incineration, and mixed disposal with other wastes (Jin et al. 2018; Sharafi et al. 2018). It is estimated that China produces nearly 900 million tons of straw annually, of which approximately 200 million tons are treated inappropriately; over 200 million tons of mulch films are used, with a recycling rate below 2/3 (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China, 2016). Annual pesticide packaging waste volume ranges from 3.5 to 4 billion units(bottles and bags), weighing 100,000 to 180,000 tons (Wang 2019). China has actively pursued policy initiatives and treatment measures for agricultural wastes. The“Management Measures for the Recycling and Treatment of Pesticide Packaging Waste” implemented in 2020 mandated recycling obligations of pesticide producers, operators, and users, establishing a closed-loop management mechanism of “who uses, who returns”; The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued the “Implementation Opinions on the Prevention and Control of Solid Waste Pollution” in 2021, advocating the harmless treatment of four major agricultural solid wastes: livestock and poultry manure, crop straw, agricultural film, and pesticide packaging materials. The 2025 Central Committee’s No. 1 Document further emphasized establishing a green agricultural production standards framework. Despite China’s progress in transitioning agriculture from traditional to modern systems, significant challenges remain (Wang et al. 2022). Unlike developed countries adopt centralized management of large-scale farms, China’s smallholder model dominates, characterized by fragmented arable land holdings. Consequently, AWs are dispersed among micro-farmers, making their participation crucial (Jin et al. 2015). Exploring the determinants of farmers’ AWs recycling behavior is therefore critical for developing precision interventions and promoting a circular economy.

Scholars have identified multiple factors influencing farmers’ AWs recycling behavior. First, government policies play a critical role. Studies across Brazil, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, and China suggest that regulatory policies and management programs enhance recycling efficiency (Pan et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2021). Economic incentives (Chen 2022; Xu et al. 2021) and subsidies (Li et al. 2022) has also proven effective in promoting recycling. Second, informal institutions such as social norms and moral constraints serve as significant drivers (Coronel-Chugden et al. 2024; Li et al. 2022; Zheng and Luo 2022). Additionally, numerous scholars have demonstrated the role of environmental psychological factors in motivating individuals’ recycling behavior regarding AWs (Khoshnodifar et al. 2023; Pronello and Gaborieau 2018), including environmental cognition, personal norms, values, environmental awareness (Khoshnodifar et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2021; Xue et al. 2021). The environmental psychology model suggests posits that individual’s emotional changes may trigger approach or avoidance behaviors (Mehrabian and Russell 1974). Empirically, external barriers or environmental inconveniences may affect the psychological factors of AWs recycling decisions, thereby influencing behavioral intentions (Zhang et al. 2016; De Fano et al. 2022; Otto et al. 2018; Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). However, the inhibitory pathways remain unexplored.

Not doing is not necessarily the opposite of doing. The current study ignores the emotional component of attitudes, reducing the explanatory power of theory regarding behavior (Shen and Wang 2022). It takes time to observe and recognize the benefits of agricultural waste recycling, but the moment of action implementation entails psychological resource depletion. For instance, collecting dispersed mulch films demands time and effort, potentially triggering negative emotions (stress, irritation, etc.) among farmers and consequently causing emotional exhaustion. In other words, the part where attitudes in conventional research typically fail to explain actual behavior is essentially the “attitude toward behavioral non-performance” (Pronello and Gaborieau 2018; Coronel-Chugden et al. 2024). Thus, examining the influence of emotional dynamics during behavioral execution and associated costs on behavioral intention to AWs recycling (i.e., payment of personal resources, an oppositional force) may yield promising approaches for encouraging recycling behavior.

Behavioral costs are obstacles that require the expenditure of personal resources (e.g., time, money, exertion) to be overcome. Empirical evidence has demonstrated that behavioral costs inhibit pro-environmental behavior, such as household waste recycling (Otto et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2016; Andersson and von Borgstede 2010) and tourism waste management (Esfandiar et al. 2020). Behavioral costs stem from the sociocultural conditions in which people act, and are thus behavior- and context-specific. It provides a general contextual threshold for people to participate in the behavior (Kaiser 2021). However, there has been no comprehensive study on the role of behavioral costs in the issue of AWs recycling. Studies have shown that high-level environmental attitudes can compensate for the inhibitory effect of behavioral costs on behavioral occurrence (Kaiser et al. 2021; Kaiser and Lange 2021). The literature also has revealed that behavioral costs, motivation, environmental awareness, sacrifice, and other psychological factors collectively influence recycling behavior (Kramer and Petzoldt 2022; Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). However, they only focus on specific or sporadic psychological perspectives. Therefore, paying attention to the impact and mechanism of behavioral costs on AWs recycling behavior is of great value for enriching the pro-environmental behavior theory and optimizing practical policies.

In addition, behavioral choices involve high-cost and low-costs situations, in terms of time, money, and energy. A study suggests that pro-environmental behaviors are more likely to occur when costs and inconvenience are low (Diekmann and Preisendörfer 1998). When the particular situation unable to provide individuals with acceptable conditions for action, environmental beliefs, norms, and awareness of consequences are reported as drivers or interveners of pro-environmental behavior (Andersson and von Borgstede 2010; Steg et al. 2014). Actually, in the context of recycling behaviors involving high financial costs and/or substantial efforts, various motivations(e.g., rationality, morality, and emotion) conflict with each other. There is a long-standing controversy over how they function properly in pro-environmental behaviors (Diekmann and Preisendörfer 2003; Kaiser and Schultz 2009; Tian and Liu 2022). Individuals vary in their perceived costs due to competition among revenue, hedonic, and normative goals (Otto et al. 2018; Steg et al. 2014), which leads to different behavioral decision-making. However, there is a gap in simultaneously exploring the effects of rational, emotional, and ethical factors on AWs’ recycling behavior. Furthermore, AWs recycling practices differ in behavioral costs,and only by elucidating how different factors influence specific AWs recycling behaviors, can precise policies be implemented.

To fill the above gaps, we conducted an online survey in two representative provinces in northwestern and southeastern China, with a total of 902 responding farmers. We aim to address the following research questions: Q1. What is the impact of behavioral costs (including time, economic, and effort costs) and awareness of consequences on the behavioral intention to recycle AWs? Q2. What is the role of emotional exhaustion in AWs recycling behavioral intention, and what are the factors that determine and alleviate it? Q3. What are the multiple driving mechanisms (including paths of rationality, morality, and emotion) of AWs recycling behavioral intention, and differences across AWs with various behavioral costs?

This study extends TPB theory by integrating it with norm activation theory and resource conservation theory in terms of external environmental factors (i.e., adding behavioral costs and consequence awareness) and internal psychological factors (i.e., adding emotional exhaustion and personal norms). It constructs an integrated theoretical framework that contributes a comprehensive understanding of how environmental and psychological barriers affect behavioral intentions to recycle agricultural waste and the corresponding approaches of mitigation or abatement. Specifically, the research contributes to the existing literature in three ways. First, this study bridges the gap in TPB regarding the effect of emotional resources on behavioral intentions by focusing on emotional exhaustion. It establishes the first rural environmental governance participation and decision-making model, revealing the implicit psychological barriers to sustainable agricultural practices. Second, this study addresses the neglect of the influence of behavioral costs on AWs recycling behavior, it identified the antecedents of perceived behavioral control from the perspective of cost barriers, which overcame a critical limitation of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) theory. Third, it further explores the different effects of multidimensional psychological factors on AWs recycling behavior with different behavioral costs, expands the low-cost hypothesis.

Theoretical background

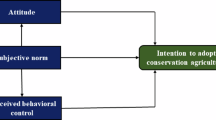

The theory of planned behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is considered a universally applicable theory for explaining human behavior. Existing research has demonstrated that TPB is a reliable and valid model to predict individuals’ pro-environmental intention or behavior, including the recycling behavior of agricultural film, plastic waste, discarded batteries, and face masks etc. (Zhao et al. 2023; Galati et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2016; Oludoye et al. 2023). The TPB is mainly used to predict how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control affect people’s intentions to behave (Ajzen 1991; Abadi 2023). The TPB explains pro-environmental behavior as a rational choice based on deliberate calculation of the expected costs and benefits of as well as the ability to perform the given behavior under certain social pressure (Ajzen 1991; Wu et al. 2022). AWs’ recycling has the characteristic of a positive externality. As economists argue, people are unwilling to put in the energy to improve it, but expect to enjoy the benefits of an improved environment (Li et al. 2022). Any behavior of a person always involves costs (Kaiser and Wilson 2004). People are sensitive to the personal “cost expenditures” associated with altruistic behaviors, especially highly selfish ones. However, little is known in the current literature about the impact of behavioral costs on farmers’ participation in AWs recycling. More importantly, the detailed psychological path is also a black box.

Perceived behavioral control is added to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) as a third key factor to account for situations in which individuals are unable to fully control, culminating in the TPB. Perceived behavioral control is determined by the confidence-framed (perceived difficulty) and control-framed items derived separately from external and internal interventions (Yzer 2012). There is a consensus that internal factors, also known as autonomy factors, have self-efficacy as their most relevant explanatory variable. Environmental barrier factors or perceived difficulties determine the confidence framework, i.e., the capacity aspect. However, little is known about the components of the latter (Zolait 2014; Yzer 2012), especially in the AWs’ recycling behavior. Thus, this study suggests that various types of behavioral costs may be effective antecedents for predicting perceived behavioral control.

Conservation of resources theory (COR)

Plenty of researchers criticized TPB for attaching too much to rational decision-making, excluding the influence of unconscious, associative, and emotional factors (Esfandiar et al. 2019). TPB was found to be unable to explain how the experiential process changes the actor’s behavioral intentions when performing pro-environmental activities. Individuals’ willingness to engage in a particular behavior is not fixed and can be adjusted according to the experiential process (De Groot and Steg 2009). The theory should be expanded to capture subtle changes in behavioral intentions towards pro-environmental behaviors over short periods. Conservation of resources theory (COR) suggests that people will strive to retain and acquire resources and reduce the threat of a net loss (Hobfoll 1988). According to COR, when an individual performs a behavior using more resources, such as energy, condition, etc. (Halbesleben et al. 2014), a certain amount of stress will occur., which can cause an overuse of emotional resources That’s to say, if farmers spend more behavioral costs (e.g., effort and time spent in collecting and centralizing pesticide packages to prescribed disposal sites) on AWs recycling, they will suffer from a loss of physical and mental resources (Wang et al. 2021), called emotional exhaustion, which in turn lead to negative behavior. Therefore, this study extends the TPB model by adding emotional exhaustion to compensate for the underestimation of the impact of instantaneous emotional changes on behavior in existing research. Furthermore, a relationship between behavioral cost variables and emotional exhaustion was established and tested.

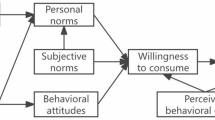

Norm activation model (NAM)

AWs’ recycling is a typical pro-environmental behavior that involves a complex decision-making process often driven by multiple motivations (Onel and Mukherjee 2017; Steg et al. 2014). The original TPB has been proven to have low explanatory power for behavior formation due to its neglect of the role of intrinsic morality or norms (Yuan et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2024). The Norm activation model (NAM) focuses on examining individuals’ altruistic intention and behavior (Schwartz 1977). According to NAM, individual altruistic behavior or intention is influenced by personal norms, and the level of consequence awareness and responsibility attribution contributes to the generation of the norms (Schwartz 1977). Scholars have incorporated personal norms into TPB, and the results consistently indicate that personal norms significantly predict recycling intentions or behaviors, surpassing the original variables of TPB (Yuan et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022; Onel and Mukherjee 2017). In the decision-making process of recycling behavior of AWs farmers are faced with the conflict between protection of social resources and conservation of personal resources. NAM suggests that the creation of altruistic behaviors depends on the assessment of the payment or cost and the possible consequences. People with high environmental concerns perceive social resources (good public environment) as more important and have lower desire for private resource conservation (Liu et al. 2022). Therefore, the introduction of personal norms and awareness of the consequences in the conceptual model contributes to a more comprehensive explanation of behavioral determinants and decision-making processes.

Summarily, this study established a comprehensive theoretical framework based on TPB, NAM, and COR, and also includes behavioral cost variables. Specifically, to address the research problem, it takes behavioral costs (including time costs, effort costs, and economic costs) and awareness of consequence as antecedents of the TPB model, and adds emotional exhaustion and personal norms to enrich the psychological decision variables of the TPB model. The importance and necessity of the model were twofold. Firstly, it provides a comprehensive theoretical framework on how behavioral costs affect behavioral intention to recycle AWs. It has advantages in understanding the underlying reasons why pro-environmental behavior (i.e., AWs recycling) does not always occur: (1) the impact of instantaneous emotional changes in executing behavior; (2) the impact of factors that individuals are unable to fully control, such as environmental barriers (behavioral costs). Secondly, this model provides insights into how rational, moral, and emotional psychological pathways simultaneously influence pro-environmental behavior decisions when farmers face conflicts between personal resource conservation and social resource protection. A theoretical support was proposed for exploring how to internalize the external costs of pro-environmental or pro-social behaviors in the future.

Hypotheses development

Influence of rational factors on intention to recycle AWs

Attitude (AT) in TPB is an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of a particular behavior (Ajzen 1991), reflecting the extent to which the actor approves of the behavior. Previous study has confirmed that attitudes can directly influence the intention of AWs’ recycling behavior (Muise et al. 2016). Subjective norms (SN) are the social pressures from others that individuals experience when deciding whether or not to perform a particular behavior (Ajzen 1991), and they reflect the degree of influence that others have on the actor. It has been pointed out that subjective norms exercise a significant positive predictive effect on farmers’ AWs recycling behavioral intention (Khoshnodifar et al. 2023; Rastegari et al. 2023). Perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to an individual’s evaluation of the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior and the existence of resources and opportunities to do so. For example, the cost of performing, the abundance of time, and the strength of the individual’s abilities (Galati et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2023). Perceptions of ability and self-confidence also significantly influence intention to recycle AWs (Wang et al. 2021). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1:Attitude has a significant positive effect on behavioral intention for AWs recycling

H2:Subjective norms has a significant positive effect on behavioral intention for AWs recycling

H3:Perceived behavioral control has a significant positive effect on behavioral intention for AWs recycling

Influence of behavioral costs as difficulty factors

AWs’ recycling behavior depends on some ability, planning, cooperation of others, time, money, and other barriers (Kraft et al. 2005; Yzer 2012). It takes behavioral costs, such as effort cost (EFC), time cost (TIC), and economic costs(ECC) for individuals to perform actions. The perceived behavioral control is usually related to behavioral costs (Kaiser et al. 2021). Recycling AWs is quite difficult when effort costs are high (e.g., traveling long distances to recycling sites) (Esfandiar et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2022). People are often well aware of the economic sacrifices involved in recycling and tend to act in a cost-sensitive manner (Connor et al. 2021). There is a study that suggested that cost and convenience are understood as the fundamental constructs of perceived behavioral control (De Fano et al. 2022). People who perceived higher barriers were less likely to perceive control over their waste disposal behavior (Oludoye et al. 2023). Summarily, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4:Time cost has a significant negative effect on perceived behavioral control .

H5:Effort cost has a significant negative effect on perceived behavioral control .

H6:Economic cost has a significant negative effect on perceived behavioral control.

Antecedents and consequences of emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion (EE) is a feeling of emotional, energetic, and mental exhaustion. In other words, it is a psychological state in which people feel drained of energy, depleted of resources, helpless at work, and emotionally exhausted. Research demonstrated a significant adverse effect of emotional exhaustion on individual intentions for pro-environmental behaviors (Liu et al. 2022).

Studies have shown that when farmers spend more effort, time (e.g., effort and time spent in collecting and centralizing pesticide packages to prescribed disposal sites), and money (e.g., money spent on technical services or products to support recycling), it results in further loss of resources. The stress of resource loss triggers negative emotions in individuals, resulting in emotional exhaustion (Bao and Zhong 2019). Furthermore, when a farmer’s emotions are in a state of depletion, the perceived behavioral control over participation in AWs is diminished (Carmel and Leiser 2017). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H7:Emotional exhaustion has a significant negative effect on behavioral intention for AWs recycling

H8:Time cost has a significant positive effect on emotional exhaustion

H9:Effort cost has a significant positive effect on emotional exhaustion

H10:Economic cost has a significant positive effect on emotional exhaustion

H11:Emotional exhaustion has a significant negative effect on perceived behavioral control

Influence of normative factors on intention to recycle behavior

Personal norms (PN) described as feelings of moral obligation to perform pro-environmental behaviors, significantly predict behavior (Schwartz 1977; Khoshnodifar et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2022). Studies found that adding personal normsto the TPB improves its explanatory power for altruistic behavior (Pakpour et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2022). In addition, personal norms was found to be influenced by subjective norms (Wang et al. 2023). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H12: Personal norms have a significant positive effect on behavioral intention for AWs recycling

H13: Subjective norms have a significant positive effect on personal norms.

The low-cost hypothesis suggests that psychological factors have different impacts on behaviors with different costs, and a strong environmental attitude is required to promote high-cost pro-environmental behaviors. Awareness of consequences (AC) constitutes a vital variable in the NAM (Park and Ha 2014). It refers to the individual’s alertness to possible adverse outcomes of not performing a specific behavior. Previous studies have shown a significant relationship between awareness of consequences and attitude toward AWs recycling (Oludoye et al. 2023; Park and Ha 2014; Shi et al. 2021). Meanwhile, research has shown that environmental concern variables such as knowledge and personal norms have a significantly enhanced impact on high-cost behavior (Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). In general, high levels of awareness of consequence are more likely to trigger personal norms (Wang et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2022). The existing study confirmed that internalized personal norms can be promoted via awareness of consequences (Xu et al. 2024). For the recycling behavior with different behavioral costs, factors beyond attitude need to be further explored. In addition, awareness of consequence also influence emotional exhaustion (Esfandiar et al. 2020; Esfandiar et al. 2019). Given the above relationship, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H14: Awareness of consequences has a significant positive effect on attitude

H15:Awareness of consequences has a significant positive effect on personal norms

H16: Awareness of consequences has a significant positive effect on emotional exhaustion

The conceptual framework is presented in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data collection

The data studied in this paper come from a questionnaire survey conducted by the research group within China. Based on the principles of universality and representativeness, we selected Jiangsu and Shanxi provinces, which are located in the northwest and southeast, respectively. Firstly, they are the major agricultural production provinces in China, and the situation of AWs recycling can cover the national characteristics. Secondly, they have been doing active exploration in encouraging or regulating agricultural waste recycling, such as the introduction of a series of policies, and so on. Third, the economic development levels of these two provinces are similar to the national average in China. The infrastructure, technology, and farmers’ sensitivity to economic factors in them can be extrapolated to a large part of China. In 2024, China’s per capita GDP was 95.7 thousand CNY, with Jiangsu Province at 128 thousand CNY and Shaanxi Province at 62 thousand CNY. In other words, the two provinces well reflect the economic characteristics of both the developed eastern regions and the developing central and western regions of China.

Prior to the formal survey, we conducted a pilot study in which 40 farmers were invited. After receiving feedback, we refined some of the wording and questions so that they could be better understood from the farmers’ perspective. In order to ensure the reliability of the data, a minimum response time was set, and screening questions and duplicate questions were set.

The investigation was carried out by the research team. Sample selection was done by stratified random sampling. 13 prefecture-level cities in Jiangsu Province and 10 prefecture-level cities in Shaanxi Province were included in the survey. According to the level of economic development, the number of farmers, and the area of farmland, stratified sampling is adopted within each prefecture-level city. 2 counties were selected from each prefecture-level city, and 46 counties were used in total. According to the same principles and methods, 2 townships are randomly selected from each county, and approximately 15 households are randomly selected from each township based on the village roster. Township cadres organized and convened farmers, and then distributed survey questionnaires to them. Members of the research team participated, assisted, and supervised throughout the entire process. Eventually, a total of 1307 questionnaires were actually distributed, excluding invalid questionnaires (including hasty answer, random answers, contradictions, incomplete answers, etc.) totaling 405, obtaining 902 valid questionnaires. The effective recovery rate of the questionnaire was 69.01%. It meets the expected requirements of this survey. After completing the questionnaire, the respondents will get a payment of 50 RMB for time spent. All participants were informed and agreed that their answers would be used for academic research.

Variable measurement

The questionnaire consists of two main parts. The first part is demographic information, and the statistical results are shown in Table 1. The second part is the measurement scales for the variables involved in the model. Measurement scales for all variables were cited from similar well-established literature. The details are as follow (see Supplementary Table S1 online): attitude (Galati et al. 2020), subjective norms (Galati et al. 2020), perceived behavioral control (Galati et al. 2020; Zolait 2014), personal norms (Onwezen et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2022), emotional exhaustion (Karatepe et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2022), awareness of consequence (Onwezen et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2022), time cost (Omar et al. 2022; Oludoye et al. 2023; Zolait 2014), energy cost (Omar et al. 2022; Zolait 2014), economic cost (Omar et al. 2022; Zolait 2014), behavioral intentions to recycle (Ajzen 1991; Wang et al. 2022). All items were measured via a 7-point Likert scale, with scores 1–7 indicating progressively increasing in compliance.

Data analysis technique

This study analyzed the validity of the data and tested the hypotheses using PLS-SEM via SmartPLS V3.0. The first stage involves evaluating the measurement model, which mainly includes the internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the latent variables. The second stage is to test the hypothesized path. We test the hypothesized paths of different agricultural wastes by dividing the conceptual model into three sub-models and repeating the Bootstrap test 5000 times. Specifically, the recycling behaviors of pesticide packaging waste, discarded agricultural film, and crop straw are taken as dependent variables, respectively. We adopted this technology for several reasons. First, unlike CB-SEM analyses, PLS-SEM does not require the data to have a normal distribution (Chin 1998). Second, PLS-SEM is more suitable for complex models with many constructs or exploratory theoretical model verification when seeking the extension of existing models (Hair et al. 2021). Therefore, we considered PLS-SEM as an appropriate approach.

Harman’s one-factor test was used to test the potential common variance. The analysis shows that ten factors are present in each recycling behavior model and the highest variance demonstrated by a single factor is 21.133%, 20.815%, and 20.729% separately, far below the recommended value of 40% (Podsakoff et al. 2003). As a result, common method bias does not pose a serious threat to the research findings. The chi-square tests and independent sample t-tests were performed via SPSS 22.0. The findings indicated no significant difference between the first and last 300 respondents (p < 0.05), thus, non-response bias was not an evident problem (Armstrong and Overton 1977).

Results

Measurement model

As shown in Table 2, Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables were between 0.748 and 0.946, which were higher than the threshold of 0.7. All the composite reliability (CR) values were between 0.853 and 0.965, greater than 0.8. The rho_A values were all greater than 0.7. These reflected good internal consistency and reliability (Hair et al. 2021). The AVE and outer loadings exceeded the limit values of 0.50 and 0.70, and the convergent validity was confirmed. Table 3 displayed the HTMT ratios, although a few values are greater than 0.85, the discriminant validity was satisfactory overall.

Structural model analysis

The variance inflation factor (VIF) was checked, which indicates that VIF values between the latent variables are all below 3.3. Therefore, there is no serious problem of multicollinearity. The structural model was evaluated using the PLS-SEM, and the results demonstrate a good fit: i) The SRMR values of the models for RB of pesticide packages, mulch film, and straw were 0.033, 0.034, and 0.039, which were less than the recommended threshold value 0.08. (ii) All Q2 values and Q² predict values obtained by the blindfolding technique were greater than 0, achieving the prediction relevance (Table 4).

Table 4 reports the results of the hypothesis in the conceptual model. In order to make the results more intuitive, the results are also visualized (Fig. 2). First, the factors in the original TPB model have different effects on the recycling behavior of different agricultural wastes. Attitude had significant positive effects on all three types of AWs recycling behaviors (H1), the effect of subjective norms on the recycling behavior of straw was not significant (H2), and the effect of perceived behavioral control on the recycling behavior of pesticide packaging was not supported (H3). Meanwhile, the effort cost and economic cost had significant negative effects on perceived behavioral control, while no significant effect of time cost was observed, including pesticide packages, mulch, and straw. This implies that H4 is not valid and H5 and H6 are valid.

Second, the results report that emotional exhaustion shows a direct negative effect on BIPR and BIMR. That is to say, H7 held for these two. Time cost, effort cost, and economic cost showed a significant effect on emotional exhaustion, which argued for hypotheses H8, H9, and H10. In addition, the results show that emotional exhaustion tends to have a significant negative effect on farmers’ perceived behavioral control (H11).

Thirdly, there was no association between personal norms on the RBP and RBM, and H12 only held for the BISR.Meanwhile, subjective norms effectively triggered positive personal norms (H13).,The results showed a significant positive effect of awareness of consequences on attitude and personal norms, which supported H14 and H15. Awareness of consequences also significantly reduced emotional exhaustion in the farms (H16).

Mediation effects analysis

In the model constructed in this study, there are 13 paths involving mediating effects with awareness of consequences and behavioral costs as the independent variables and behavioral intention to recycle as the dependent variable. Table 5 reports the specific indirect effects of three types of psychosocial factors on BIPR. The results show that the indirect effects of time cost, effort cost, and economic cost on BIPR were significant through the mediation of emotional exhaustion. In addition, awareness of consequences also had a significant effect on BIPR indirectly through the specific mediator of attitude.

Table 6 shows specific results on BIMR. The results showed that time cost, effort cost, and awareness of consequences had significant indirect effects on recycling behavior through either the mediator of emotional exhaustion or the chain channel of emotional exhaustion to perceived behavioral control. economic cost has a negative impact on recycling behavior only via the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion. Meanwhile, effort cost and economic cost also exerted inhibiting effects on recycling behavior through perceived behavioral control. In addition, awareness of consequences significantly motivated positive environmental attitudes, which in turn promoted recycling behavior.

The specific results of BISR are shown in Table 7. Most of the results are the same as the BIMR. The time cost, effort cost, economic cost, and awareness of consequences had significant indirect effects on recycling behavior through the chain channel of emotional exhaustion to perceived behavioral control. Meanwhile, effort cost and economic cost also exerted inhibiting effects on recycling behavior through perceived behavioral control. In addition, awareness of consequences positively influences recycling behavior, not only through attitude but also through personal norms.

Multi-group analysis. A multi-group analysis was conducted to further investigate potential differences in relationships among groups in terms of age (Age), educational level (Edu) of the farmer, and annual agricultural income (Inc) of the farm. Regarding age, the samples were divided into two groups: respondents with an age above 56 (Age_Higher) and those aged 55 and below (Age_Lower). Further, regarding education level, respondents who have received more than 12 years of education were classified as Edu_Higher, while the others were classified as Edu_Lower. Based on yearly agricultural income level, two groups were generated: Inc_Higher (above 50 thousand CNY) and Inc_Lower (50 thousand CNY and below).

To determine the validity of the effects, measurement invariance was established before PLS-MGA. The Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) approach was employed to determine the homogeneity between the two groups. The results of the MICOM test are acceptable for further study, as suggested by Matthews (2017). The results of the MGA in terms of Age, Edu, and agricultural Inc are shown in Table 8. According to the MGA results, there are significant differences in several paths. The p-values of group differences for the other comparison paths were determined to be more than 0.05. It is revealed no statistically significant differences in any correlations.

Regarding age, there exists a significant difference in the effect of awareness of consequences on emotional exhaustion. For both older and younger groups, awareness of consequences has a significantly negative impact on emotional exhaustion. However, the emotional exhaustion for the older group is influenced more by awareness of consequences than that for the younger group. Effort costs significantly affected emotional exhaustion in both groups, with a greater effect on the older age group.

Regarding agricultural income level, awareness of consequences shows a significant difference in attitude between groups with higher income. It can be found that the attitude of the group with higher agricultural income is more sensitive to awareness of consequences. In contrastfor the group with lower agricultural income, awareness of consequences also positively affects attitude, but the effect is lower.

In terms of farmers’ education level, significant differences are found in awareness of consequences, emotional exhaustion, and effort cost. For groups with a higher education level, awareness of consequences has a relatively higher influence on emotional exhaustion than that for groups with lower education levels. Emotional exhaustion has a stronger and negative influence on perceived behavioral control for groups with lower education levels. Further, effort cost has a positive and significant effect on emotional exhaustion for groups with lower education levels, while it is not significant for groups with a higher education level. The effect of effort cost on perceived behavioral control is significant in both groups, and is greater for the high education level group. It is worth noting that in this comparison, the relationship between social norms and behavioral intention in pesticide packaging recycling intention yielded results opposite to those of the other two AWs. The results show that social norms have a significant positive effect on behavioral intention for group with a higher education level, while the effect is not significant for the other. However, there was no significant difference in this pathway between high and low education levels for the other two types of waste.

Discussion

This study is one of the few that investigated the influence of obstructive forces (behavioral costs and emotional exhaustion) on recycling behavior of AWs and concentrated on analyzing the mediating mechanisms of emotional exhaustion, together with moral and rational factors. These associations were measured from data collected from Chinese farmers, and most of the hypotheses were confirmed.

First, in the original TPB model, attitude is the strongest and most stable determinant influencing agricultural waste recycling behavior (including pesticide packaging, agricultural film, and straw) among Chinese farmers. This suggests that farmers’ intentions to recycle AWs are significantly enhanced when they have a high positive attitude toward recycling. This is consistent with the earlier findings (Galati et al. 2020). Perceived behavioral control on behavioral intention to recycle pesticide packaging has not been demonstrated. This result indicated that farmers perceived deficiencies in conducting since it is almost impossible to rely on technology, machinery, and other means for pesticide packaging recycling, which requires a lot of time and effort (Meng et al. 2015). Subjective norms significantly influence behavioral intention to recycle for pesticide packaging and agricultural film, but not for crop straw. The results differ from those of studies conducted in Pakistan, the northeastern region, and Guangdong Province in China (Raza et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2022; Zheng and Luo 2022). In fact, there are also uncertain results in previous studies about the relationship between them (Xu et al. 2024). The reason for poor predictive power may lie in surrounding farmers generally lack straw recycling practices (weak descriptive norms), subjective norms are difficult to form effective constraints (Xue et al. 2021). Some studies have also found that the driving force of subjective norms can be overshadowed by practical constraints such as economics and technology (Mills et al. 2017).

Second, emotional exhaustion was found to be a significant opposing force to participating in AWs recycling among farmers, which works both directly and indirectly. Consistent with the view held by COR theory (Hobfoll 1988), due to the loss of psychological resources, farmers exhibit negative behaviors to retain surplus resources or avoid net losses. This study identifies behavioral costs constitute a stressor, which can lead to heightened emotional exhaustion and then reduce the motivation to engage in AWs recycling behavior (Kaiser and Lange 2021). The finding that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between behavioral costs and recycling behavior is not only in line with the stress-strain-outcome model (Jabutay et al. 2022) but also supported by other studies (Esfandiar et al. 2019). Concerning specific waste types, perceived time costs and effort costs negatively affected pesticide packaging and mulch film recycling behavior through the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion, which was also testified in similar studies (Liu et al. 2022; Otto et al. 2018).

Third, the results reveal that awareness of consequence promotes positive behavioral intention to AWs recycling indirectly through attitudes, emotional exhaustion, or emotional exhaustion-perceived behavioral control. Previous studies have reached similar conclusions, indicating that environmental responsibility is an antecedent of attitude (De Fano et al. 2022), and pro-environmental (social) sense of calling is the predictor for emotional exhaustion (Karatepe et al. 2021). The low-cost hypothesis suggests that as the cost of behavior increases, higher environmental attitudes are needed to compensate (Kaiser and Lange 2021). This study adds new insights to the low-cost hypothesis in that the introduction of interventions, such as information about behavioral consequences or environmental knowledge that reduces emotional exhaustion of the actor, is another effective path to offset high behavioral costs. Moreover, it argues that the classification of agricultural waste recycling behavior as general recycling behavior (low-cost behavior) seems to be hasty and supports the idea that its determinants should be explored separately as different behaviors (Diekmann and Preisendörfer 2003; Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). This study tends to conclude that the recycling behavior of crop straw is high cost, and further research introducing experimental economics and other approaches is necessary in the future.

Contrary to expectation, for pesticide packaging and agricultural films, the mediating role of personal norms between awareness of consequence and intention to recycle behavior is not significant. This finding may stem from the fact that it is difficult to quantify the negative consequences of inappropriate recycling on the reduction of soil fertility and contamination of produced water, so awareness of the consequences has not yet been internalized as a personal norm to guide farmers’ pro-environmental behavior stably (Wang et al. 2022). In contrast, for straw, subjective norms can trigger positive personal norms, positively influence farmers’ intentions to recycle AWs. This suggests that active interpersonal interactions are more effective for activating intrinsic moral and emotional responses (Yin and Shi 2021).

Fourth, it identified and validated that behavioral cost is an external difficulty factor for farmers’ perceived behavioral control over AWs’ recycling process. It implied that behavioral costs are also the underlying constructs for perceived behavioral control of Pro-environmental behavior on the production end (De Fano et al. 2022). The previous studies have tested the significant effects of facilitation (technology, resources, and government support), cost (available time, space, and ease of conducting) on perceived behavioral control (De Fano et al. 2022; Zolait 2014), this study further clarifies and simplifies the factors that are classified ambiguously. It was found that perceived economic costs as an impediment to the recycling behavior of discarded mulch and straw, which is mostly mediated by perceived behavioral control.

This study conducted multiple group analyses. The significant differences in several paths indicate that behavioral distinctions exist among different groups, and further provide insights into the differences in behavioral patterns of farmers (Li et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2021; Andersson et al. 2010). The older farmers’ awareness of consequences is more likely to cause emotional exhaustion. The Nature Connectedness Theory also points out, the deep connection between elderly farmers and the land will amplify the psychological impact of environmental degradation (Restall et al. 2015). In China, older farmers have experienced decades of labor-intensive agricultural production methods and are willing to expend physical effort on collecting AWs. Therefore, compared with the younger, the negative impact of effort costs on emotional exhaustion is less. This result supports the idea that intention to protect environment increases with age from another perspective (Otto et al. 2014). Research indicates that households with a high proportion of agricultural income exhibit a stronger perception of environmental risks (Yu et al. 2022). In this context, the awareness of consequences has a greater influence on attitudes toward waste recycling among farmers with high agricultural income. This aligns with the findings of this study.

The impact of awareness of consequences on emotional exhaustion is greater in groups with a higher education level than in the other group. It differs from previous research (Candeias et al. 2024). The reason may be that individuals with higher educational levels have a more scientific and systematic understanding of environmental risks, but they are also more acutely aware of the limitations of personal contributions. The cognitive conflict between “knowing and doing” accelerates the exhaustion of psychological resources. In contrast, the low-education group developed a psychological buffer due to cognitive ambiguity. This finding provides new insights for existing literature. For farmers with a lower education level, emotional exhaustion had a stronger inhibitory effect on perceived behavioral control. This result suggests that emotional exhaustion largely weakens the rational and logical systems of low-education individuals, reducing their perception of the difficulty and controllability of recycling behavior (Chen et al. 2021). For farmers with higher education levels, perceived behavioral control is more sensitive to effort costs. For farmers with lower education levels, effort costs have a significant negative impact on emotional exhaustion. These conclusions provide a more detailed mechanism for how effort costs hinder recycling behavior. Additionally, for pesticide packaging, the insignificant influence of social norms on recycling behavior intentions in group with lower education suggests that subjective norms or others’ judgments do little to shape their pro-environmental behavior.

Conclusions and implications

Conclusion

In summary, this study aims to promote smallholder farmers’ active participation in the proper recycling and management of AWs, thereby advancing agricultural sustainability and environmental friendliness. It focuses on investigating the underlying barriers and mitigating factors. Specifically, this study is the first to examine the impact of emotional exhaustion on behavioral intentions of AWs recycling. More significantly, it highlights the critical role of behavioral costs based on large-scale data in shaping these recycling practices. The main findings are as follows. First, it was found that behavioral costs constituted a barrier stressor to farmers, leading to emotional exhaustion and negative behavioral intentions to recycle agricultural wastes. Specifically, for pesticide packages and mulch, perceived energy and time costs exhaust farmers’ emotional resources and result in negative recycling behaviors. Second, behavioral costs are significant antecedents of perceived behavioral control. Economic and effort costs are key factors that result in low perceived behavioral control in straw recycling. Third, awareness of consequences significantly enhances farmers’ environmental attitudes or reduces emotional exhaustion, which in turn triggers their recycling behavior for all types of AWs. This study adds new insights to the low-cost hypothesis in that the introduction of interventions, such as information about behavioral consequences or environmental knowledge that reduces the emotional exhaustion of the actor, is another effective path to offset high behavioral costs. Fourth, rational, ethical, and emotional psychological factors have different impacts on the intention of AWs recycling behavior with different behavioral costs.

Given the results, mitigation strategies were proposed. A substantial reduction in behavioral costs and a reduction in individual sensitivity to private capital loss are suggested as promising ways to encourage recycling behavior among AWs. Meanwhile, the government should develop precise policies for different categories of recyclables. Using the “Theory of Change” approach, this study generalized the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework for behavioral intentions to recycle AWs. It clearly demonstrates how the theoretical model works to achieve the stated goals (see Fig. 3).

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to theory in several ways. First, this study enriches the temporal effects of AWs’ recycling behavior by incorporating emotional exhaustion parameters (Liu et al. 2022). It establishes the first rural environmental governance participation and decision-making model that includes emotional exhaustion dimensions, revealing the implicit psychological barriers to sustainable agricultural practices. This study successfully broadens the frontiers of COR theory to pro-environmental behaviors at the production end and clarifies the antecedents and consequences of emotional exhaustion, which enriches TPB weaknesses to explain emotional differences in behavior processes.

Second, this study provides a theoretical framework for understanding the impact of behavioral costs on behavioral intentions to recycle AWs by extending the TPB model for the first time. Meanwhile, the antecedents of perceived behavioral control, especially in AWs recycling, were identified and confirmed from the perspective of obstructive behavioral costs. It remedies a strong existing limitation of the TPB theory, which is that control beliefs are generalized concepts under specific research scenarios or problems (Yzer 2012).

Third, this study expands the low-cost hypothesis for agricultural waste recycling behaviors. Previous studies have mostly focused on discussing the relationship between behavioral costs and attitudes (psychological factors), such as interaction, superposition, or moderation. This study clarified the impact of three psychological pathways, namely ethical norms, emotional changes, and rationality, on the behavioral intention to recycle AWs with different behavioral costs. A new insight was identified that drawing attention to the consequences of behavioral choices can be seen as an effective alternative to substantially reducing behavioral costs.

Practical implications

Policymakers can benefit from this study in several ways. First, the study proves that behavioral costs and emotional exhaustion have a negative effect on is agricultural waste recycling behavior. It inspires us that the first way to encourage farmers to engage in recycling behavior is to reduce behavioral costs. Improving the accessibility of recycling facilities or developing low-cost recycling methods is the most direct and fundamental means (Diekmann and Preisendörfer 1998; Khan et al. 2020). These measures, which weaken the disincentives, are promising for the future, as opposed to economic incentives, which have been criticized as unstable and prone to moral hypocrisy.

Second, the findings emphasize the need to consider AWs’ recycling as a multifactorial behavior, and the government should develop precise incentive policies for different categories of AWs (Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). For example, the recycling of pesticide packaging waste should be promoted through adding recycling or storage containers to field plots (Chi et al. 2014), establishing recycling stations along farm roads, encouraging informal waste collectors, etc. (In rural China, where farm areas are generally separated from settlements, there are barely any garbage recycling installations in farm areas currently). The recycling of mulch films and straw can be characterized by infrequency and scale, and perceived economic costs are seen as the most significant barrier to behavior. Therefore, the provision of affordable technology equipment or even free social services is necessary. Meanwhile, the behavioral patterns of farmers with different characteristics are distinctive. For younger farmers, those with higher agricultural income levels, or those with lower education levels, developing easy-to-understand training courses and strengthening environmental risk education through non-textual forms (e.g., village radio broadcasts and graphic manuals) are recommended.

Third, this study confirms that the three categories of rationality, morality, and emotion have a superimposed or offsetting influence on agricultural waste recycling behavior. Policymakers are required to pay attention to the combined effects, and reducing individual sensitivity to the loss of private capital by reinforcing the influence of moral norms is a second important strategy. These approaches able people to draw attention to the environmental consequences of behavioral choices. Policymakers are supposed to move toward an intervention strategy that emphasizes more information, education, and awareness (Otto et al. 2018), which aims to reduce the perception of high behavioral costs (Byrka et al. 2017). That is, farmers are encouraged to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., behave without emotion) in some metacognitive way (Kudesia 2019; Walsh and Arnold 2018). On the other hand, these strategies help people to think about behavioral decisions based on multiple goals. If subjected to asymmetric information and low awareness of consequences for a long period, people will focus on the main task (not recycling to save effort or money) and ignore other goals (e.g., protecting the productive capacity of arable land, not threatening cultivation for decades or the next generation) (Zhang et al. 2024).

Limitations and future research

The study also presents some limitations. First, the random samples used in this study were from relevant provinces in China. The ecological perspective of “unity between heaven and humanity” in the Eastern context leads to a stronger awareness of environmental responsibility, which contrasts with the “threat-response” model emphasized in Western environmental psychology. Meanwhile, the environmental attitudes and social norms of farmers in different cultures vary considerably across regions. Such different contexts may lead to different results (Raza et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2022; Zheng and Luo 2022). A further segmented discussion based on different cultures and socioeconomic contexts is necessary in the future.

Second, this study uses self-reported data from respondents based on a questionnaire, which runs the risk of creating a social desirability bias. Self-reported data are easier to obtain and analyze, such as the various types of behavioral costs paid for participating in recycling behaviors. To improve validity and counteract social desirability bias, this study used at least three different items to measure an indicator (Andersson and von Borgstede 2010). However, it would be more convincing if conditions allowed for the collection of objective data to measure the variables of behavioral costs and actual behavior.

Third, further exploring the moderating role of other emotional factors and experimentally analyzing the effects of interventions such as information, knowledge, economic subsidies, and policy regulations are also valuable directions for future research.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality commitments made to survey participants. Making the full data set publicly available might compromise the privacy assurances given to participants upon their agreement to partake in the study and could also contravene the ethical approval obtained for the research. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abadi B (2023) Impact of attitudes, factual and causal feedback on farmers’ behavioral intention to manage and recycle agricultural plastic waste and debris. J Clean Prod 424:138773

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Andersson M, von Borgstede C (2010) Differentiation of determinants of low-cost and high-cost recycling. J Environ Psychol 30(4):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.02.003

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

Bao Y, Zhong W (2019) How stress hinders health among Chinese public sector employees: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of perceived organizational support. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(22):4408

Byrka K, Kaiser FG, Olko J (2017) Understanding the acceptance of nature-preservation-related restrictions as the result of the compensatory effects of environmental attitude and behavioral costs ER-. Environ Behav 49(5):487–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516653638

Candeias AA, Galindo E, Reschke K, Bidzan M, Stueck M (2024) The interplay of stress, health, and well-being: unraveling the psychological and physiological processes. Front Psychol 15(2024):1471084

Carmel E, Leiser D (2017) From perceived control to self-control, the importance of cognitive and emotional resources. Behav Brain Sci 40:e321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X17000917

Chen H, Eyoun K (2021) Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int J Hospitality Manag 94:102850

Chen S (2022) British dairy farmers’ management attitudes towards agricultural plastic waste: reduce, reuse, recycle. Er Polym Int 71(12):1418–1424. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.6442

Chi X, Wang MYL, Reuter MA (2014) E-waste collection channels and household recycling behaviors in Taizhou of China ER-. J Clean Prod 80:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.056

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod Methods Bus Res 295(2):295–336

Coronel-Chugden J, Castillo JA, Moreno-Quispe LA, Flores-Castillo M, Campos FG (2024) Sociodemographic factors and feelings of guilt in household waste management in Peruvian households ER-. Int J Innovative Res Sci Stud 7(2):567–575. https://doi.org/10.53894/ijirss.v7i2.2684

Diekmann A, Preisendörfer P (1998) Environmental behavior: discrepancies between aspirations and reality. Rationality Soc 10(1):79–102

Diekmann A, Preisendörfer P (2003) Green and greenback: the behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Rationality Soc 15(4):441–472

Esfandiar K, Pearce J, Dowling R (2019) Personal norms and pro-environmental binning behaviour of visitors in national parks: the development of a conceptual framework. Tour Recreat Res 44(2):163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1580936

Esfandiar K, Dowling R, Pearce J, Goh E (2020) Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: an integrated structural model approach. J Sustain Tour 28(1):10–32

De Fano D, Schena R, Russo A (2022) Empowering plastic recycling: Empirical investigation on the influence of social media on consumer behavior. Resour Conserv Recycling 182:106269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106269

Galati A, Sabatino L, Prinzivalli CS, D Anna F, Scalenghe R (2020) Strawberry fields forever: that is, how many grams of plastics are used to grow a strawberry? J Environ Manag 276:111313

De Groot JIM, Steg L (2009) Morality and prosocial behavior: the role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J Appl Soc Psychol 149(4):425–449. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449

Hair Jr, JF, Hult, GTM, Ringle, CM, Sarstedt, M, Danks, NP, Ray, S (2021) Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. Springer Nature, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Halbesleben JRB, Neveu J, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M (2014) Getting to the “COR”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory ER-. J Manag 40(5):1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hobfoll SE (1988) The Ecology of Stress. New York: Taylor and Francis

Hsu E (2021) Cost-benefit analysis for recycling of agricultural wastes in Taiwan. Waste Manag 120:424–432

Jabutay FA, Suwandee S, Jabutay JA (2022) Testing the stress‐strain‐outcome model in Philippines‐based call centers ER-. J Asia Bus Stud 17(2):404–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-06-2021-0240

Jin S, Bluemling B, Mol APJ (2015) Information, trust and pesticide overuse: Interactions between retailers and cotton farmers in China ER-. NJAS Wagening J Life Sci 72-73(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2014.10.003

Jin S, Bluemling B, Mol AP (2018) Mitigating land pollution through pesticide packages–the case of a collection scheme in Rural China. Sci Total Environ 622:502–509

Kadhim ZR, Ali SH, Barbaz DS, Alnagar AS (2022) The economic and environmental effects of recycling plant agricultural wastes in Iraq (yellow maize production farms in Babil Province - a case study). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 1060(1):12145. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1060/1/012145

Kaiser FG (2021) Climate change mitigation within the Campbell paradigm: doing the right thing for a reason and against all odds. Curr Opin Behav Sci 42:70–75

Kaiser FG, Wilson M (2004) Goal-directed conservation behavior: the specific composition of a general performance. Personal Individ Diff 36(7):1531–1544

Kaiser FG, Schultz PW (2009) The attitude–behavior relationship: a test of three models of the moderating role of behavioral difficulty 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 39(1):186–207

Kaiser FG, Lange F (2021) Offsetting behavioral costs with personal attitude: Identifying the psychological essence of an environmental attitude measure ER-. J Environ Psychol 75:101619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101619

Kaiser FG, Kibbe A, Hentschke L (2021) Offsetting behavioral costs with personal attitudes: a slightly more complex view of the attitude-behavior relation. Personal Individ Diff 183:111158

Karatepe OM, Rezapouraghdam H, Hassannia R (2021) Sense of calling, emotional exhaustion and their effects on hotel employees’ green and non-green work outcomes. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manag 33(10):3705–3728. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2021-0104

Khan O, Daddi T, Slabbinck H, Kleinhans K, Vazquez-Brust D, De Meester S (2020) Assessing the determinants of intentions and behaviors of organizations towards a circular economy for plastics ER-. Resour Conserv Recycling 163:105069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105069

Khoshnodifar Z, Ataei P, Karimi H (2023) Recycling date palm waste for compost production: A study of sustainability behavior of date palm growers. Environ Sustainability Indic 20:100300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2023.100300

Koul B, Yakoob M, Shah MP (2022) Agricultural waste management strategies for environmental sustainability. Environ Res 206:112285

Kraft P, Rise J, Sutton S, Røysamb E (2005) Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? Br J Soc Psychol 44(3):479–496

Kramer J, Petzoldt T (2022) A matter of behavioral cost: contextual factors and behavioral interventions interactively influence pro-environmental charging decisions. J Environ Psychol 84:101878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022. 101878

Kudesia RS (2019) Mindfulness as metacognitive practice ER -. Acad Manag Rev 44(2):405–423. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0333

Li B, Xu C, Zhu Z, Kong F (2022) How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: subsidies VS social norms. J Clean Prod 367:133016

Liu S, Cheng P, Wu Y (2022) The negative influence of environmentally sustainable behavior on tourists. J Hospitality Tour Manag 51:165–175

Ma J, Gao H, Cheng C, Fang Z, Zhou Q, Zhou H (2023) What influences the behavior of farmers’ participation in agricultural nonpoint source pollution control?—Evidence from a farmer survey in Huai’an, China. Agric Water Manag 281:108248

Matthews L (2017) Applying multigroup analysis in PLS-SEM: a step-by-step process. In: Latan H, Noonan R (eds) partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 219–243

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974) An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

Meng T, Klepacka AM, Florkowski WJ, Braman K (2015) What drives an environmental horticultural firm to start recycling plastics? Results of a Georgia survey. Resour Conserv Recycling 102:1–8

Mills J, Gaskell P, Ingram J, Dwyer J, Reed M, Short C (2017) Engaging farmers in environmental management through a better understanding of behaviour. Agric Hum Values 34:283–299

Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China (2016) Pilot Program for Promoting the Resource Utilization of Agricultural Waste (No. 90 of 2016). Beijing: Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China

Muise I, Adams M, Côté R, Price GW (2016) Attitudes to the recovery and recycling of agricultural plastics waste: a case study of Nova Scotia, Canada. Resour, Conserv Recycling 109:137–145

O Connor P, Assaker G (2021) COVID-19’s effects on future pro-environmental traveler behavior: an empirical examination using norm activation, economic sacrifices, and risk perception theories. J Sustain Tour 30(1):89–107

Obi FO, Ugwuishiwu BO, Nwakaire JN (2016) Agricultural waste concept, generation, utilization and management. Niger J Technol 35(4):957–964

Oludoye OO, Van den Broucke S, Chen X, Supakata N, Ogunyebi LA, Njoku KL (2023) Identifying the determinants of face mask disposal behavior and policy implications: an application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Resour, Conserv Recycling Adv 18:200148

Omar Q, Yap CS, Ho PL, Keling W (2022) Predictors of behavioral intention to adopt app among the farmers in Sarawak, Malaysia. Br Food J 124(1):239–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2021-0449

Onel N, Mukherjee A (2017) Why do consumers recycle? A holistic perspective encompassing moral considerations, affective responses, and self‐interest motives. Psychol Mark 34(10):956–971

Onwezen MC, Antonides G, Bartels J (2013) The Norm Activation Model: an exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J Econ Psychol 39:141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.07.005

Otto S, Kaiser FG (2014) Ecological behavior across the lifespan: why environmentalism increases as people grow older. J Environ Psychol 40:331–338

Otto S, Kibbe A, Henn L, Hentschke L, Kaiser FG (2018) The economy of E-waste collection at the individual level: a practice oriented approach of categorizing determinants of E-waste collection into behavioral costs and motivation ER-. J Clean Prod 204:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.293

Pakpour AH, Zeidi IM, Emamjomeh MM, Asefzadeh S, Pearson H (2014) Household waste behaviours among a community sample in Iran: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag 34(6):980–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman. 2013.10.028

Pan Y, Ren Y, Luning PA (2021) Factors influencing Chinese farmers’ proper pesticide application in agricultural products – a review ER -. Food Control 122:107788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107788

Park J, Ha S (2014) Understanding consumer recycling behavior: combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam Consum Sci Res J 42(3):278–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12061

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Pronello C, Gaborieau J (2018) Engaging in pro-environment travel behaviour research from a psycho-social perspective: a review of behavioural variables and theories ER-. Sustainability 10(7):2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072412

Rastegari H, Petrescu DC, Petrescu-Mag RM (2023) Factors affecting retailers’ fruit waste management: behavior analysis using the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Environ Dev 47:100913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2023. 100913

Raza MH, Abid M, Yan T, Naqvi SAA, Akhtar S, Faisal M (2019) Understanding farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable crop residue management practices: a structural equation modeling approach. J Clean Prod 227:613–623

Restall B, Conrad E (2015) A literature review of connectedness to nature and its potential for environmental management. J Environ Manag 159:264–278

Schwartz SH (1977) Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in experimental social psychology, 10, pp. 221–279. Elsevier

Shahni K, Rajashekar Y, Haobam B, Rajan JP, Singh KB (2024) Rare and unexplored traditional waste food processing and fermentation methods of the meitei-pangal community of Manipur: a northeastern state of India ER-. J Asian Sci Res 14(3):301–316. https://doi.org/10.55493/5003.v14i3.5075

Sharafi K, Pirsaheb M, Maleki S, Arfaeinia H, Karimyan K, Moradi M, Safari Y (2018) Knowledge, attitude and practices of farmers about pesticide use, risks, and wastes; a cross-sectional study (Kermanshah, Iran). Sci Total Environ 645:509–517

Sharma A, Shukla A, Attri K, Kumar M, Kumar P, Suttee A, Singh G, Barnwal RP, Singla N (2020) Global trends in pesticides: a looming threat and viable alternatives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 201:110812

Shen M, Wang J (2022) The impact of pro-environmental awareness components on green consumption behavior: the moderation effect of consumer perceived cost, policy incentives, and face culture ER. Front Psychol 13:580823. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022

Shi J, Xu K, Si H, Song L, Duan K (2021) Investigating intention and behaviour towards sorting household waste in Chinese rural and urban–rural integration areas ER-. J Clean Prod 298:126827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126827

Singh Y, Sidhu HS (2014) Management of cereal crop residues for sustainable rice-wheat production system in the Indo-Gangetic plains of India. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad 80(1):95–114

Steg L, Bolderdijk JW, Keizer K, Perlaviciute G (2014) An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: the role of values, situational factors and goals ER -. J Environ Psychol 38:104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.01.002

Tian H, Liu X (2022) Pro-environmental behavior research: theoretical progress and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(11):6721

Tripathi N, Hills CD, Singh RS, Atkinson CJ (2019) Biomass waste utilisation in low-carbon products: harnessing a major potential resource. NPJ Clim Atmos Sci 2(1):35

Walsh MM, Arnold KA (2018) Mindfulness as a buffer of leaders’ self-rated behavioral responses to emotional exhaustion: a dual process model of self-regulation. Front Psychol 9:2498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02498

Wang F, Cheng Z, Reisner A, Liu Y (2018) Compliance with household solid waste management in rural villages in developing countries. J Clean Prod 202:293–298

Wang M, Gong S, Liang L, Bai L, Weng Z, Tang J (2023) Norms triumph over self-interest! The role of perceived values and different norms on sustainable agricultural practices. Land Use Policy 129:106619

Wang Y, Yuan Z, Tang Y (2021) Enhancing food security and environmental sustainability: a critical review of food loss and waste management. Resour, Environ Sustain 4:100023

Wang Y, Wang N, Huang GQ (2022) How do rural households accept straw returning in Northeast China? Resour Conserv Recycling 182:106287

Wang Y, Long X, Li L, Wang Q, Ding X, Cai S (2021) Extending theory of planned behavior in household waste sorting in China: the moderating effect of knowledge, personal involvement, and moral responsibility. Environ Dev Sustain 23:7230–7250

Wang D, Fu J, Xie X, et al. (2022) Spatiotemporal evolution of urban-agricultural-ecological space in China and its driving mechanism. J Clean Prod 371:133684

Wang M (2019). The amount of pesticide packaging waste is astonishing, and recycling and disposal work remain arduous. Retrieved from http://www.jsppa.com.cn/article.php?id=1844

Wu L, Zhu Y, Zhai J (2022) Understanding waste management behavior among university students in China: environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Front Psychol 12:771723

Xu X, Zhang Z, Kuang Y, Li C, Sun M, Zhang L, Chang D (2021) Waste pesticide bottles disposal in rural China: policy constraints and smallholder farmers’ behavior. J Clean Prod 316:128385

Xu Z, Meng W, Li S, Chen J, Wang C (2024) Driving factors of farmers’ green agricultural production behaviors in the multi-ethnic region in China based on NAM-TPB models. Glob Ecol Conserv 50:e2812

Xue Y, Guo J, Li C, Xu X, Sun Z, Xu Z, Feng L, Zhang L (2021) Influencing factors of farmers’ cognition on agricultural mulch film pollution in rural China. Sci Total Environ 787:147702

Yin J, Shi S (2021) Social interaction and the formation of residents′ low-carbon consumption behaviors: an embeddedness perspective. Resour, Conserv Recycling 164:105116

Yin Q, Wang Q, Du M et al. (2024) Promoting the resource utilization of agricultural wastes in China with public-private-partnership mode: an evolutionary game perspective. J Clean Prod 434:140206

Yu L, Liu W, Yang S, Kong R, He X (2022) Impact of environmental literacy on farmers’ agricultural green production behavior: evidence from rural China. Front Environ Sci 10:990981

Yuan Y, Xu M, Chen H (2022) What factors affect farmers’ levels of domestic waste sorting behavior? a case study from Shaanxi Province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(19):12141

Yzer M (2012) Perceived behavioral control in reasoned action theory: a dual-aspect interpretation. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 640(1):101–117