Abstract

Technological innovations are increasingly promoted as solutions to climate change. However, many innovations, including Carbon Capture and Storage, bioplastics, and glacier geo-engineering, suffer significant limitations from high costs, speculative efficacy, and adverse ecological consequences. Using Granular Interaction Thinking Theory (GITT), a transdisciplinary framework grounded in information theory, quantum mechanics, and mindsponge theory, in this study, we explain how such technological innovations become systemically favored despite their flaws. We introduce the concept of the “innovation curse,” which arises when institutional and cognitive filtering systems, operating under high informational entropy, default to familiar but ineffective techno-solutions while marginalizing Indigenous and Local Knowledges and nature-based approaches. To address this dysfunction, we propose the Eco-Surplus Transformation Framework, a new model for environmental decision-making designed to foster an eco-surplus culture. Guided by a core semiconducting principle that prohibits offsetting environmental harm with monetary value, the framework establishes a rational hierarchy for climate action that prioritizes harm prevention and proven ecological strategies. We provide the Eco-Surplus Governance Matrix as a toolkit for implementing this paradigm shift through institutional reform. Ultimately, our study argues for a fundamental reorientation of climate strategy away from technological solutionism and toward regenerative, community-driven practices rooted in Indigenous and Local Knowledges to foster long-term environmental resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Losing patience, Kingfisher decides to press the buttons rapidly, hoping to make this foreign ‘opponent’ dizzy, disoriented, and finally frightened. […] Pressing those buttons faster and faster, Kingfisher resembles a circus clown.

But there is one thing he can’t achieve: fear.”

—“Innovation,” in Wild Wise Weird (2024)

Introduction

In our efforts to address climate change and environmental degradation, humanity has increasingly turned to technological innovations as potential solutions. However, these approaches often reveal complex trade-offs and limitations that raise fundamental questions about their viability as long-term sustainability strategies (Lau et al., 2021; McLaughlin et al., 2023). This paradoxical pattern, which we refer to as the “innovation curse,” occurs when costly, energy-intensive technological innovations are prioritized despite their questionable effectiveness, thereby exacerbating environmental problems while displacing more effective alternatives. In fact, the recognition of this pattern was inspired by the story “Innovation,” a satire on the wastefulness of impractical high-tech advancements in Wild Wise Weird (Vuong, 2024). This satirical fable encourages readers to reflect on the genuine vision of sustainability (Nguyen, 2024).

The limitations of technological climate interventions have been documented across multiple domains. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies, for example, despite their theoretical promise, face significant implementation challenges, including high operational costs, energy-intensive processes, and risks of CO2 leakage that compromise their effectiveness (Deng et al., 2017; Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023). Similarly, bioplastics, often presented as sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics, raise concerns about land-use competition, food security impacts, and environmental performance that varies significantly based on production methods and disposal practices (Cruz et al., 2022; Helm et al., 2025; Olagunju & Kiambi, 2024). Glacier geoengineering proposals, while theoretically capable of slowing ice loss, confront major logistical difficulties, uncertain effectiveness, and the risk of unintended impacts on marine ecosystems and ocean circulation (Moore et al., 2018; Sutter et al., 2023; Wolovick & Moore, 2018). These technological approaches exemplify an “eco-deficit culture” that prioritizes end-of-pipe solutions driven by profit-seeking motivations over addressing the systemic drivers of environmental degradation (Hindin, 2022; Vuong, 2021b).

Despite growing evidence of their limitations, high-tech climate innovations continue to receive disproportionate institutional support, media attention, and financial investment compared to nature-based alternatives (Bellamy & Osaka, 2020; Drury et al., 2022; Slavíková, 2019). This preference for complex technological solutions over simpler, nature-based approaches represents a critical knowledge gap in sustainability research. The systematic marginalization of traditional practices reflects broader patterns of technological bias that have been extensively documented across science and technology studies, environmental sociology, and critical development studies.

This technological bias operates through what scholars term “epistemicide” or “epistemic injustice”―the systemic exclusion and devaluation of certain knowledge systems (de Sousa Santos, 2014; Fricker, 2007). Winner (1980) demonstrates how technologies embody political values that exclude alternative ways of knowing, while Scott (1998) reveals how “high modernist” technological schemes consistently undervalue local knowledge despite its proven effectiveness. In environmental contexts, this bias manifests as Western technological paradigms that create development narratives positioning traditional ecological practices as primitive, despite their demonstrated sustainability (Chausson et al., 2020; Lafortezza et al., 2018). Contemporary scholarship extends this analysis through the lens of “digital colonialism,” examining how digital technologies perpetuate historical power imbalances by exploiting Indigenous data and knowledge systems (Carroll et al., 2021; Nothias, 2025; Rana, 2025). This systematic preference for formalized, Western-centric scientific knowledge over diverse, experiential Traditional Ecological Knowledge narrows the perceived solution space and overlooks resilient, time-tested practices (Aswani et al., 2018; IPCC, 2023; Whyte, 2017). While the prior literature compellingly diagnoses the structural and discursive mechanisms that drive knowledge devaluation, it does not fully explain the underlying information-processing dynamics that make Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems vulnerable to knowledge loss in the first place, especially in contemporary climate policy.

To address this gap, in this paper, we apply Granular Interaction Thinking Theory (GITT) (Vuong & Nguyen, 2024a, 2024c), which is grounded in quantum mechanics (Rovelli, 2018), information theory (Shannon, 1948), and mindsponge theory (Vuong, 2023), to examine how the proliferation of technological climate solutions contributes to the innovation curse and accelerates the erosion of nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges. Specifically, our study aims to address three objectives.

First, we critically analyze the limitations, energy requirements, and effectiveness of three prominent technological interventions: CCS, bioplastics, and glacier geoengineering. Second, we demonstrate how information overabundance and competing technological solutions displace nature-based approaches and Indigenous epistemologies. Third, we propose the eco-surplus transformation framework as an alternative paradigm that leverages nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems to address current environmental challenges.

By analyzing the structural biases in climate innovation, we offer a theoretical framework for understanding how the innovation curse systematically disadvantages Indigenous and Local Knowledges despite their proven effectiveness for environmental management. Given the lack of prior research examining how technological fixation erodes traditional ecological practices, our study serves as a pioneering inquiry into these relationships using GITT. Our findings are expected to inform the development of more inclusive, equitable approaches to climate policy that integrate Indigenous wisdom with contemporary governance systems, thereby enhancing both ecological resilience and community empowerment. The eco-surplus framework we propose offers practical pathways for policymakers to reimagine sustainability strategies that operate within planetary boundaries while strengthening community adaptation capacities and traditional knowledge systems that are vital for our collective survival.

The innovation curse

To illustrate the innovation curse, we now examine three widely promoted technological climate interventions: CCS, bioplastics, and glacier geoengineering. Our analysis reveals a consistent pattern of high implementation costs, energy-intensive operations, and unintended consequences that often undermine their sustainability benefits. These technologies exemplify an eco-deficit culture that prioritizes end-of-pipe solutions for the sake of economic growth over addressing systemic drivers of environmental degradation.

Carbon capture and storage

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is a technology designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by capturing CO2 from industrial processes or power generation and storing it permanently underground in geological formations (Lau et al., 2021). The process involves three main steps: capturing CO2 at its source, transporting it to a storage site, and injecting it into deep geological formations such as saline aquifers or depleted oil and gas reservoirs where it can be permanently sequestered (ibid.). CCS has emerged as a potentially vital technology for achieving deep decarbonization, particularly in hard-to-abate industrial sectors like cement, steel, and chemical manufacturing (Lau et al., 2021; McLaughlin et al., 2023).

The Earth has sufficient geological storage capacity in saline aquifers and depleted oil/gas reservoirs to sequester approximately two centuries’ worth of anthropogenic CO2 emissions (ibid.). Despite this technical potential, CCS faces formidable implementation barriers (Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023; Wennersten et al., 2015). First, the energy-intensive nature of CCS undermines its efficacy throughout the process chain. Transport alone accounts for 18-40% of a CCS project’s emissions, primarily due to fossil fuel consumption in trucks, trains, and ships (Burger et al., 2024; de Coninck & Benson, 2014). While CCS chains can reduce emissions compared to unmitigated sources, their dependency on fossil fuels for capture and transport operations creates a counterproductive cycle that partially offsets their climate benefits (Burger et al., 2024; Davoodi et al., 2023). The International Energy Agency further highlights that achieving net-zero emissions by 2070 would require nearly 40% of emission reductions to come from technologies that are still not widely embraced by the market (IEA, 2020). This technological and infrastructural challenge is compounded by the “chicken-and-egg” problem between capture, transport, and storage investments, creating additional barriers to widespread CCS deployment (Burger et al., 2024; Lane et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the security of CO2 storage in geological formations presents technical and environmental challenges. While saline aquifers and depleted oil/gas reservoirs offer significant storage potential (Albertz et al., 2023; Lau et al., 2021; Nagireddi et al., 2024), the threat of CO2 leakage remains a primary concern that could undermine both the effectiveness and safety of CCS projects (Deng et al., 2017; Mahjour & Faroughi, 2023). The injection of large CO2 volumes can trigger seismic activity and compromise storage site integrity, particularly in regions with complex geological structures (Krevor et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2022). These risks are compounded by the inherent difficulty of predicting CO2 behavior across different geological contexts, necessitating sophisticated monitoring systems and risk management frameworks (Sori et al., 2024). Despite advances in monitoring, measurement, and verification technologies, fundamental uncertainties persist about the long-term stability of stored CO2 and its potential environmental impacts (Nagireddi et al., 2024).

Finally, there are concerns that widespread CCS deployment could perpetuate fossil fuel dependency and delay necessary energy transitions. While CCS offers a pathway for reducing emissions from hard-to-abate sectors, its integration with enhanced oil recovery operations and existing fossil fuel infrastructure could extend the lifespan of carbon-intensive industries (Leung et al., 2014; Sovacool, 2021; Yasemi et al., 2023). This technological lock-in effect, combined with the high costs and infrastructure requirements of CCS, risks diverting resources and attention from more fundamental transitions to renewable energy systems (de Coninck & Benson, 2014). The continued investment in such technologies may create a false sense of security that technological fixes alone can address climate change without requiring deeper systemic transformations in energy production and consumption patterns (Hindin, 2022; Vuong, 2021b).

This concern is underscored by recent global data. Over the past decade, governments, led by the United States, Norway, Canada, and the European Union, have collectively spent over $20 billion in public funds on CCS projects, with commitments for up to $200 billion more in future support through tax incentives, grants, and innovation programs (Oil Change International, 2023). Despite these substantial financial commitments, global CCS deployment remains far below climate targets. As of late 2023, only about 65 Mt CO₂/year was being captured by around 41 commercial facilities, which represents less than 0.2% of global CO₂ emissions (Hanbury, 2024). This mismatch between the scale of investment and climate outcomes highlights the systemic inefficiency of current climate innovation priorities.

Bioplastics

Bioplastics are polymeric materials derived from renewable biomass sources such as corn starch, sugarcane, cellulose, and vegetable oils, as opposed to conventional plastics manufactured from fossil fuel-based petrochemicals (Mastrolia et al., 2022; Rosenboom et al., 2022). These materials are often promoted as an eco-friendly alternative amid the escalating global plastic pollution crisis that poses unprecedented threats to ecosystems, geophysical processes, and biological integrity (Cruz et al., 2022; Mastrolia et al., 2022). Bioplastics can be categorized based on their biodegradability properties and feedstock origins, with variations in production processes significantly affecting their environmental footprint (Islam et al., 2024; Rosenboom et al., 2022).

The primary advantage of bioplastics lies in their potential to support circular economy principles through renewable feedstock utilization and, in some cases, enhanced biodegradability (Mastrolia et al., 2022; Rosenboom et al., 2022). As conventional plastic production continues to increase, bioplastics offer a theoretical pathway to reduce fossil fuel dependency and mitigate persistent pollution issues associated with traditional plastics (Cruz et al., 2022). Some bioplastic varieties can degrade under specific conditions, potentially reducing accumulation in natural environments when properly managed (Bishop et al., 2021; Mastrolia et al., 2022). However, their adoption comes with complex trade-offs that must be carefully considered (Olagunju & Kiambi, 2024).

The transition to bioplastics could trigger significant land-use changes, potentially threatening biodiversity and food security through competition for agricultural resources (Escobar & Britz, 2021; Escobar et al., 2018; Helm et al., 2025; Leppäkoski et al., 2023). Moreover, the environmental impacts of bioplastic production vary substantially depending on feedstock choice and manufacturing processes, with some bioplastics performing worse than conventional plastics in certain impact categories (Islam et al., 2024; Jin et al., 2023; Olagunju & Kiambi, 2024). As demand for bioplastics grows, so does the pressure on agricultural land to produce the necessary biomass feedstocks (Helm et al., 2025). This could lead to the conversion of natural ecosystems, such as forests and grasslands, into monoculture plantations, resulting in deforestation and biodiversity loss (Colwill et al., 2012; Leppäkoski et al., 2023).

Recent modeling studies indicate that expanding bioplastic production could trigger substantial global land-use changes, with varying impacts across regions and scenarios (Helm et al., 2025; Jin et al., 2023). Under high consumption scenarios, the competition for land between food production, biofuels, and bioplastics becomes particularly intense, potentially leading to forest conversion for agricultural use (Colwill et al., 2012; Escobar et al., 2018). This pressure is exacerbated by the reliance on food crops like corn and sugarcane for bioplastic production, which could compromise food security and agricultural sustainability (Abe et al., 2021; Gerassimidou et al., 2021). While agricultural productivity improvements might partially offset these impacts, the fundamental tension between bioplastic feedstock demands and other land uses remains a critical concern (Colwill et al., 2012).

The environmental benefits of bioplastics are also heavily contingent on effective end-of-life management strategies, revealing another layer of complexity in their sustainability profile. While biodegradability is often touted as a key advantage, many bioplastics require specific industrial composting conditions to degrade effectively, and their behavior in wastewater treatment plants differs significantly from conventional plastics (Bishop et al., 2021; Islam et al., 2024; Mastrolia et al., 2022; Mendes & Pedersen, 2021). With global bioplastic production capacity reaching approximately 2.18 million tonnes in 2023, a significant challenge remains: over 47% of this capacity is not genuinely biodegradable in natural environments but is compostable only in industrial facilities, which are scarce globally (Dey & Jambhale, 2025). Without proper waste management infrastructure and clear disposal protocols, bioplastics can contribute to both conventional plastic pollution and microplastic contamination (Allemann et al., 2024; Verschoor et al., 2022). Life cycle assessments indicate that the environmental performance of bioplastics can vary dramatically based on disposal methods, with some scenarios showing potentially worse environmental impacts than conventional plastics when improperly managed (Cruz et al., 2022; Islam et al., 2024; Olagunju & Kiambi, 2024; Shen et al., 2020).

Finally, it is important to consider that while bioplastics may offer certain ecological advantages, they also perpetuate the mass production and consumption model of “throwaway culture,” focused on disposal rather than addressing the fundamental issue of waste generation or reuse (Hahnel et al., 2015; Taufik et al., 2020; Zhu & Wang, 2020). By providing a seemingly sustainable alternative, bioplastics may create a false sense of environmental responsibility that enables continued single-use practices and mass production models (Zhu & Wang, 2020). Research suggests that consumers may actually increase their consumption and disposal of products labeled as biodegradable or environmentally friendly, a phenomenon known as the “green consumption effect” (Hahnel et al., 2015; Hu & Meng, 2023; Luo et al., 2023). Rather than confronting the systemic drivers of waste proliferation, the bioplastics industry largely maintains existing production-consumption cycles while changing only the material inputs (Islam et al., 2024). This approach fails to challenge the linear model and represents an incremental rather than transformative response to the plastic pollution crisis (Rosenboom et al., 2022).

Glacier geoengineering

Glacier geoengineering refers to a set of proposed interventions aimed at slowing or reversing the collapse of polar ice sheets, particularly in regions like the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which has been identified as a major contributor to future sea-level rise (Batchelor et al., 2023; Duffey et al., 2023; Sutter et al., 2023). These interventions include methods such as constructing artificial islands near glacier grounding lines, managing subglacial water flow, and blocking warm water intrusion beneath ice shelves (MacAyeal et al., 2024; Moore et al., 2018).

The primary advantage of glacier geoengineering lies in its potential to delay the collapse of ice sheets, which could contribute to catastrophic sea-level rise. Some interventions, such as underwater barriers and cold-water pumping, have been modeled as potential solutions to slow ice loss (Moore et al., 2018; Wolovick & Moore, 2018). However, the effectiveness of these interventions is highly uncertain, with studies suggesting that even under optimal scenarios, interventions like stratospheric aerosol injection could only delay, not prevent, ice sheet collapse under high-emission pathways (Sutter et al., 2023), thereby raising critical questions about their long-term viability as climate solutions (Duffey et al., 2023).

Additionally, the implementation of glacier geoengineering faces significant economic and logistical obstacles that challenge its viability as a climate change mitigation strategy. Proposed interventions such as constructing artificial islands, installing pinning-point structures, and managing subglacial water flow require unprecedented investments in infrastructure and equipment (Gertner, 2024; Moore et al., 2018). For example, constructing an 80-km-long seawater curtain at 600 m depth is estimated to cost $40-$80 billion, with ongoing annual maintenance costs of $1–2 billion (Keefer et al., 2023). The logistical complexity is particularly daunting in regions like the Amundsen Sea in western Antarctica, where even icebreakers struggle to access potential intervention sites (Moon, 2018). These challenges are compounded by the need for energy-intensive water-pumping systems that must cover nearly the entire glacier catchment to be effective (Lockley et al., 2020; Moon, 2018). The substantial energy requirements of these systems would likely generate significant greenhouse gas emissions, potentially undermining the very climate goals these interventions aim to achieve (Lockley et al., 2020). Furthermore, the harsh polar environments necessitate continuous maintenance and monitoring, resulting in long-term financial commitments that extend well beyond the initial implementation costs (Gray, 2021; Sovacool, 2021). This combination of high capital requirements, logistical constraints, and ongoing operational expenses raises serious questions about the economic viability of large-scale glacier geoengineering projects.

Moreover, the efficacy of glacier geoengineering interventions remains highly uncertain due to the complex dynamics of ice sheet systems. While modeling studies suggest that interventions like underwater barriers and cold-water pumping could theoretically slow ice loss, their real-world effectiveness faces significant challenges (Moore et al., 2018; Wolovick & Moore, 2018). Recent research indicates that even under optimal conditions, these interventions could not prevent the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse in high-emission scenarios (Sutter et al., 2023). This limited effectiveness is partly due to the persistence of subsurface ocean warming, which continues to destabilize ice shelves even when surface temperatures are reduced (Alevropoulos-Borrill et al., 2024). Furthermore, while some interventions aim to slow ice loss by creating physical barriers or altering meltwater flow, they must be carefully evaluated to avoid triggering feedback mechanisms that could accelerate ice loss (Lockley et al., 2020; MacAyeal et al., 2024; Moon, 2018).

Glacier geoengineering interventions also carry substantial risks of unintended environmental consequences across multiple scales. The construction of artificial islands and underwater barriers could significantly disrupt marine ecosystems and ocean circulation patterns, while water pumping systems might alter the delicate balance of subglacial environments (Field, 2025; MacAyeal et al., 2024). These interventions also raise critical governance challenges, as their effects could extend beyond national boundaries and impact global ocean circulation patterns (Moore et al., 2021; Sovacool, 2021; Tuana et al., 2012). The transboundary nature of these impacts necessitates careful consideration of international justice and compensation mechanisms, particularly for developing nations disproportionately affected by sea-level rise.

Granular interaction thinking theory: a framework for understanding information processing and knowledge bias

The limitations of technological climate interventions highlighted above point to a deeper systemic issue—as we proliferate complex technological solutions, we may be creating more problems than we solve. In our pursuit of technological solutions to climate change, have we inadvertently created a system that undermines the very knowledge we need to survive? This question becomes particularly pressing as we examine how the exponential growth of technological solutions actually increases systemic complexity, contributing to resource inefficiencies and the systematic loss of Indigenous and Local Knowledges. While multiple factors such as colonialism, assimilation, and marginalization have contributed to Indigenous and Local Knowledge erosion (Aswani et al., 2018; Gómez-Baggethun, 2022; Johnson-Jennings et al., 2020; Kodirekkala, 2017; Tran et al., 2025), in this section, we apply GITT to explain how information processing mechanisms systematically bias knowledge selection in complex decision-making environments.

What is GITT?

Granular Interaction Thinking Theory (GITT) is an emerging transdisciplinary framework designed to explain how humans and institutions absorb, process, and prioritize information within complex environments (Vuong & Nguyen, 2024a, 2024c). GITT posits that human decision-making, at both individual and societal levels, can be understood as the result of granular interactions among information units shaped by cognitive, cultural, and institutional filters. The theory integrates three foundational theories: Shannon’s information theory (Shannon, 1948), quantum mechanics (Hertog, 2023; Rovelli, 2018), and mindsponge theory (Vuong, 2023) to provide a holistic model of information management. Each component addresses a different aspect of the information processing, and their integration reveals mechanisms that none could explain in isolation.

At its foundation, GITT uses Shannon’s information theory to model the challenge facing any decision-making system: informational entropy. From an ecological and social perspective, a high-entropy information environment, which is rich with diverse “knowledge units” ranging from scientific data to traditional practices, is potentially the most resilient and just, as it contains a wide array of adaptive solutions. However, for a decision-making system with finite cognitive, economic, and institutional resources, this diversity induces high informational entropy: a state of uncertainty and potential overload. This processing challenge is a systemic stressor; when the variety of available knowledge exceeds the system’s evaluative capacity, it can lead to cognitive overload, poor prioritization, and institutional paralysis. Shannon quantified this principle of processing uncertainty with the formula:

Here, H(X) represents the informational entropy of a random variable X with possible outcomes \(\left\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots ,{x}_{n}\right\}\) and corresponding probabilities \(\left\{P\left({x}_{1}\right),P\left({x}_{2}\right),\ldots ,P\left({x}_{n}\right)\right\}.P\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the probability of the outcome \({x}_{i}.\)Each probability \(P\left({x}_{i}\right)\) represents how likely each outcome x_i is to occur. In our study context, the variable X can be interpreted as humanity’s processing system in the current state, with i number of knowledge or solution units. Each knowledge or solution unit has its \(P\left({x}_{i}\right)\) probability to be stored and processed within humanity. Peak entropy is reached when all solutions appear equally probable \((P\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is uniform), creating a decision-making bottleneck where the system is overwhelmed by choice. For example, when decision-makers face numerous climate solutions, from CCS to Indigenous practices, the system can become paralyzed by indecision. Information theory predicts that such a system must develop filtering mechanisms to reduce this internal uncertainty, but it does not specify what those filters will be or whether they will select for the most effective solutions.

To explain the nature of this filtering process, GITT incorporates three fundamental principles from quantum mechanics: granularity, relationality, and indeterminacy (Rovelli, 2018; Schrödinger, 1944). These principles describe the universal constraints governing how complex systems interact with information.

Granularity establishes that information and energy within any system are finite and discrete rather than infinite and continuous. For human decision-making, this means that cognitive resources—such as attention, processing capacity, and memory—have absolute limits. No individual or institution can simultaneously attend to an unlimited number of information inputs. This forces selective attention, which inevitably prioritizes certain knowledge units while excluding others from consideration.

Relationality demonstrates that information exists only in relation to other information within existing frameworks. Knowledge cannot be evaluated in isolation; it gains meaning only through comparison with existing beliefs, institutional structures, and cultural values. This principle explains why identical information (such as Indigenous fire management practices) receives different evaluations depending on the institutional framework through which it is processed.

Indeterminacy reveals that future outcomes remain fundamentally probabilistic rather than deterministic, even with complete information. When decision-makers choose between climate solutions, they cannot predict outcomes with certainty. This uncertainty forces reliance on value-based judgments and institutional preferences rather than objective calculations of effectiveness.

Finally, the mindsponge theory provides a specific cognitive and psychological model that explains how humans filter and prioritize information when facing complexity (Vuong, 2023). The theory conceptualizes the mind (whether individual or collective) as an information collection-cum-processor that functions like a sophisticated “sponge, ” which absorbs or rejects information based on its perceived compatibility with a core set of values and beliefs. Information that aligns with this core is absorbed and integrated, while information that conflicts with it is rejected consciously and subconsciously.

In the context of GITT, the mindsponge mechanism is the engine of knowledge prioritization. The criteria for absorption are not based on objective truth or empirical effectiveness but on compatibility with values existing within the system. This explains why certain solutions (e.g., those aligning with values of economic growth or technological progress) may be readily accepted and funded, while other, perhaps more effective, solutions (e.g., those rooted in Indigenous and Local Knowledges) are marginalized if they challenge dominant norms and values.

Taken together, GITT provides a comprehensive framework for understanding information processing in complex environments, where information theory explains the problem of entropy, quantum principles describe the universal constraints on processing information, and mindsponge theory details the value-driven mechanism of filtering and selection. This entire adaptive process is fundamental to survival, as GITT suggests humanity can be understood as a collective information-processing system that continuously interacts with its external environment, restructuring itself to sustain its existence. Aligning with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution (Darwin, 2003; Darwin & Wallace, 1858), this principle emphasizes that only systems that effectively manage information—by efficiently acquiring, storing, transmitting, and processing it—can survive, grow, and reproduce in a dynamic environment.

GITT and the formation of the innovation curse

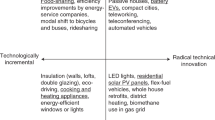

Building on the theoretical foundation of GITT, we can now trace the systemic progression from information overload to the formation of the innovation curse in climate solution selection. As established in Section 3.1, GITT posits that humanity functions as a collective information processing system that must filter environmental ideas, knowledge, and data to survive and adapt. In the context of climate change, the sheer volume and diversity of proposed solutions create a high-entropy environment, triggering the cognitive, social, and institutional filtering mechanisms that GITT describes. This process, illustrated in Fig. 1, explains how well-intentioned efforts can lead to a counterproductive lock-in to a narrow set of solutions.

Stage 1: high-entropy information environment

As depicted in the upper portion of the diagram, contemporary climate discourse is characterized by a maximum entropy condition. Decision-makers are confronted with a vast and varied landscape of potential solutions, ranging from high-tech interventions like CCS, geoengineering, and AI-driven monitoring systems to nature-based alternatives rooted in Indigenous and Local Knowledges, such as traditional agroforestry and community-led conservation. In this high-entropy state, where numerous, disparate solutions appear equally viable, the cognitive and institutional capacity for evaluation becomes overwhelmed.

The overabundance of competing knowledge or solution units leads to decision paralysis, inefficient resource allocation, and policy stagnation. As a result, even costly, high-tech, and unproven innovations receive the same level of legitimacy as time-tested, nature-based solutions despite clear differences in effectiveness, resilience, and long-term impact (Chausson et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2025). This knowledge prioritization can take two distinct forms:

First, decision-makers often favor expensive, uncertain innovations that require substantial investment, continuous updates, and corporate backing (Arora et al., 2016; Pries & Guild, 2011). These technologies often promise large-scale solutions but come with hidden costs, long-term uncertainties, and dependence on proprietary systems (Vuong & Nguyen, 2024a). For example, while CCS and geoengineering are marketed as revolutionary climate solutions, CCS plants have failed in over 80% of cases, proving economically and operationally unviable (Rai et al., 2010). Similarly, AI-driven environmental monitoring systems, while valuable, often require constant updates and expensive maintenance, making them inaccessible to resource-limited regions (Dai et al., 2023).

Alternatively, decision-makers could prioritize readily available, time-tested nature-based solutions that have proven effective through generations of Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems (Gómez-Baggethun, 2022). These solutions require lower financial investment while delivering long-term ecological and social benefits (Mendonça et al., 2021). They are locally adapted, ensuring resilience in specific environmental and cultural contexts (Blackman & Veit, 2018; Ramos-Castillo et al., 2017), and offer co-benefits beyond carbon sequestration, such as biodiversity conservation, soil regeneration, and water cycle restoration (Chausson et al., 2020).

Ultimately, when peak informational entropy is reached without clear, evidence-based knowledge prioritization, decision-makers and institutions encounter systemic inefficiencies, resulting in paralysis, misaligned policies, and poor resource allocation (Shannon, 1948; Vuong & Nguyen, 2024c). This informational saturation creates the exact conditions of maximum uncertainty that Shannon’s theory predicts, necessitating a systematic and inherently biased filtering process described in the next stage.

Stage 2: cognitive filtering and biased prioritization

The overwhelming volume of information forces the system to apply filters, which are governed by the GITT principles of granularity, relationality, and indeterminacy. Granularity establishes finite processing constraints that force selective attention. Relationality means that solutions are not evaluated independently but are filtered through pre-existing institutional frameworks, economic models, and cultural values. Indeterminacy drives value-based prioritization when facing uncertain future outcomes.

These cognitive constraints give rise to two main systemic biases: first, an economic bias that favors proprietary, patentable technologies that align with market incentives and promise scalable, profitable returns; and second, an institutional bias that privileges formalized, Western-scientific approaches that fit into existing bureaucratic, academic, and policy structures. This is the mindsponge mechanism in action: information compatible with dominant values (e.g., technological progress, perpetual economic growth) is absorbed, while information that challenges these values (e.g., non-proprietary, place-based Indigenous and Local Knowledges) is rejected, often before its effectiveness can be rationally assessed.

Stage 3: low-entropy lock-in and the innovation curse

This filtering process generates systematic knowledge prioritization that creates what the diagram terms “high-tech solutions as legitimate climate response.” The belief system becomes self-reinforcing: proprietary technologies receive corporate investment, which generates media attention and policy support, which attracts more investment. Simultaneously, alternative pathways, particularly nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems, face systematic rejection through structural exclusion from funding mechanisms, policy frameworks, and institutional recognition. The consequence is low-entropy lock-in, characterized by overconcentration on high-tech climate solutions despite their proven limitations. The cognitive rigidity of this system prevents adaptation to new information about the effectiveness of nature-based solutions, while single-path dependency limits society’s ability to respond to technological failures.

This progression culminates in the innovation curse formation, manifesting in four critical consequences: resource misallocation to unproven technologies, systematic erosion of Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems, continued environmental damage from end-of-pipe approaches, and increased systemic vulnerability stemming from technological dependency. This demonstrates how information entropy dynamics, rather than objective effectiveness assessments, primarily drive climate solution prioritization, leading to significant inefficiencies and misaligned policies.

Why expensive innovation wins: market bias and institutional legitimacy

Despite the inefficiencies, high costs, and long-term risks associated with these high-tech, corporate-backed solutions, they consistently receive greater economic and institutional support than low-cost, time-tested nature-based solutions (Lafortezza et al., 2018; Slavíková, 2019; van der Jagt et al., 2020). This reflects what Winner (1980) identifies as the inherently political nature of technological choices, in which technical artifacts embody forms of power and authority that systematically privilege certain solutions while excluding others. Our GITT framework reveals the information-processing mechanisms underlying this bias: when facing high informational entropy from competing solutions, institutional cognitive constraints favor codified, proprietary knowledge over oral, place-based wisdom. This systemic bias is primarily driven by two interconnected factors: economic incentives and institutional legitimacy, both of which shape global knowledge hierarchies and funding priorities.

A fundamental reason for the preference for costly innovations lies in the economic structure of proprietary knowledge. Market-driven models prioritize patented technologies because they create commercial opportunities for investors and corporations, reinforcing a system where profitability, rather than effectiveness, determines which solutions receive support (Arora et al., 2016; Pries & Guild, 2011). The "battery bubble," for example, shows how hype, policy incentives, and financial speculation can drive investment into a single technology, risking outcomes like "immiserizing growth" (Vuong et al., 2025). Meanwhile, many Indigenous and Local Knowledge-based solutions lack clear ownership structures, making them incompatible with Western intellectual property regimes and market-driven funding models (Mendes et al., 2020). Furthermore, Indigenous and Local Knowledges are collective, context-dependent, and transmitted across generations, which makes it difficult to commodify or integrate into deeply rooted mainstream financial system (Nguyen et al., 2023). This economic misalignment ensures that high-cost technological solutions, despite their inefficiencies, receive disproportionate financial backing, while Indigenous and Local Knowledge-based practices remain systematically excluded from funding opportunities (Bellamy & Osaka, 2020; Slavíková, 2019).

A clear example can be found in climate adaptation policies, where large-scale engineering projects, geoengineering solutions, and high-tech carbon capture technologies receive billions in funding, while Indigenous peoples and local communities, who play a critical role in managing carbon sinks and conserving biodiversity, receive less than 1% of global climate finance (Blackman & Veit, 2018; Nelson et al., 2023; Ramos-Castillo et al., 2017). This disparity is not merely a funding issue but a structural bias in how solutions are valued and prioritized. Governments and investors favor high-tech, capital-intensive projects because they fit within existing financial, legal, and governance structures, while simpler, community-led ecological practices are dismissed as “non-innovative” or difficult to scale (Bridgewater, 2018; Chausson et al., 2020). Ultimately, this economic misalignment reinforces a system where expensive innovations take precedence over simpler, more effective ecological practices, perpetuating a cycle of technological dependency rather than investing in more sustainable, localized solutions (Gómez-Baggethun, 2022).

The second major reason for this structural bias is the institutional legitimacy and media amplification that accompany expensive, corporate-backed innovations (Drury et al., 2022). Technologies endorsed by corporations and powerful institutions receive disproportionate media attention, policy integration, and financial backing, reinforcing the perception that they are the most viable solutions (Bellamy & Osaka, 2020; Dai et al., 2023). In contrast, Indigenous and Local Knowledges are often oral, context-dependent, and intergenerational, making them less visible within formal knowledge systems (Gómez-Baggethun, 2022). Knowledge transmission in Indigenous and Local contexts occurs through lived experience and everyday practice rather than codified reports, patents, or academic publications, creating a fundamental mismatch with dominant institutional frameworks (Nesterova, 2020). This lack of formalization leads to structural exclusion from funding mechanisms, governance structures, and climate adaptation policies, further reducing its perceived legitimacy (Mendonça et al., 2021).

Additionally, regulatory uncertainty, fragmented policies, limited financial incentives, and low public awareness of Indigenous and Local Knowledges further marginalize its adoption (Nesterova, 2020). Even in cases where Indigenous and Local Knowledges have proven their effectiveness, such as in forest conservation, agroecology, and climate resilience, their integration into mainstream decision-making remains weak due to scientific elitism, economic barriers, and institutional inertia (Blackman & Veit, 2018; Bridgewater, 2018). The tendency to favor high-tech, capital-intensive solutions over nature-based, community-led approaches not only distorts climate and sustainability discourse but also reinforces existing power imbalances in knowledge production and policy influence (Chen et al., 2020; Miklian & Hoelscher, 2020; Vuong, 2021b).

For example, for thousands of years, Indigenous Australians have practiced cultural burning to manage landscapes, reduce fuel loads, and prevent catastrophic wildfires. These controlled burns, carefully timed with seasonal weather patterns and biocultural indicators (McKemey et al., 2020), effectively clear dry vegetation while maintaining biodiversity and supporting traditional food resources (McGregor et al., 2010). Historical records and paleoecological studies confirm that widespread Indigenous burning shaped Australian ecosystems, keeping shrub cover low and reducing the intensity of wildfires (Mariani et al., 2024). However, colonial policies suppressed and even criminalized these practices, favoring fire exclusion and suppression strategies (Fletcher et al., 2021). Over time, this shift increased fuel loads, contributing to the very conditions that make modern wildfires so destructive. Despite growing evidence of its effectiveness, cultural burning remains marginalized in favor of high-tech firefighting interventions such as aerial water bombing and large-scale prescribed burns (Perry et al., 2018). These costly and reactive approaches receive disproportionate media attention, policy support, and public funding, reinforcing the perception that technological fire suppression is superior (Laming et al., 2022). However, studies show that such methods fail to address long-term fire risks because they do not integrate localized, fine-scale Indigenous fire management (Huffman, 2013).

The devastating 2019 - 2020 Australian bushfires (also known as Black Summer fires), which burned more than 17 million hectares of land, destroyed thousands of homes, and resulted in massive biodiversity losses, demonstrated the failures of modern fire suppression policies (NHRA, 2023; Wintle et al., 2020). Studies later acknowledged that Indigenous fire knowledge could have significantly reduced the severity of these fires, had it been systematically integrated into national fire management policies (Fletcher et al., 2021; Kreider et al., 2024; Mariani et al., 2024). However, despite this acknowledgment, Indigenous fire practitioners still struggle to secure funding and institutional support, while government-led large-scale fire strategies and bureaucratic fire management models continue to dominate wildfire policies worldwide (Maclean et al., 2023; Perry et al., 2018).

Losing what we need most: the erosion of time-tested solutions

Earth, our only known planet capable of supporting human life, has finite resources. Yet the persistent prioritization of uncertain, expensive innovations over time-tested, nature-based solutions continues to accelerate environmental degradation, deplete biodiversity, and drive irreversible knowledge loss (Li et al., 2022). This misalignment between technological investment and planetary constraints not only threatens present stability but also compromises humanity’s long-term adaptability and survival (Lafortezza et al., 2018).

At the heart of this crisis lies a fundamental limitation in humanity’s ability to process and retain information. As informational entropy rises, decision-makers and institutions are forced to filter out “non-prioritized” knowledge, often favoring digitized, standardized information over traditional, experience-based wisdom (Nguyen et al., 2025; Vuong & Nguyen, 2024b). Indigenous and Local Knowledges, which are deeply embedded in oral traditions, cultural practices, and ecological adaptation, are frequently the first casualty of this filtering process and, in many cases, irretrievable (Gómez-Baggethun, 2022). Without intentional prioritization, the rapid loss of traditional ecological wisdom not only erases invaluable cultural heritage but also disrupts proven sustainable resource management practices, leading to further ecosystem degradation and reduced climate resilience (Mendes et al., 2020; Ramos-Castillo et al., 2017).

The loss of Indigenous and Local Knowledges extends far beyond cultural heritage. It represents the erosion of sophisticated ecological understanding that has sustained local ecosystems and human societies for generations. Indigenous and Local Knowledge systems provide adaptive, sustainable resource management practices that are crucial for long-term environmental resilience, biodiversity conservation, and socio-economic stability (Nesterova, 2020; Vijayan et al., 2022). As this knowledge disappears, societies increasingly default to unsustainable, short-term practices, leading to biodiversity loss, ecosystem degradation, and declining community well-being (Mendes et al., 2020; Ramos-Castillo et al., 2017). As we advance in our efforts to address climate change, the central challenge is no longer merely generating more technological solutions, but rather discerning which solutions genuinely drive progress and which merely add to an overcrowded, high-entropy information landscape (Vuong & Nguyen, 2024a). If society continues to channel resources toward high-cost, uncertain technologies while neglecting Indigenous and Local Knowledges and nature-based solutions, we risk undermining the very foundations of sustainable solutions and knowledge that we need most.

Overcoming the innovation curse: the eco-surplus transformation framework

The environmental crises of the 21st century demand a radical shift in how humanity approaches technology and nature. The innovation curse, as outlined in Section 3, arises from a high-entropy information environment where biased decision-making systems prioritize speculative, resource-intensive technologies over sustainable, time-tested solutions. This eco-deficit culture, rooted in assumptions of infinite resources and technological supremacy, leads to inefficiencies and the marginalization of vital ecological knowledge. In this section, we propose the Eco-Surplus Transformation Framework, a strategic approach that reduces informational entropy, reorients societal values, and centers nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges as sophisticated, low-entropy technologies. This framework, detailed in four subsections, offers a practical roadmap for transitioning from eco-deficit to eco-surplus thinking, ensuring climate action is effective, equitable, and aligned with planetary boundaries.

From eco-deficit to eco-surplus culture

Our GITT analysis revealed a system trapped in an eco-deficit culture—a paradigm that consistently prioritizes economic compatibility over ecological effectiveness. This culture operates through a biased information filter that, when overwhelmed by high-entropy environments of competing climate solutions, defaults to familiar, profitable options while systematically rejecting effective, non-market solutions. The resulting innovation curse manifests as wasteful spending, marginalization of proven knowledge, and increased systemic risk.

The transition from an eco-deficit to an eco-surplus culture represents a profound shift in how societies approach and prioritize environmental solutions. From a GITT perspective, this transition fundamentally repairs the biased filtering mechanisms that favor unsustainable practices. This repair is achieved by elevating nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges, which possess critical advantages over conventional technological interventions.

First, this transition reshapes the mindsponge filter by replacing a value system focused on single-variable efficiency with one that prioritizes multifunctionality and holism. Engineered climate interventions typically target single variables like carbon sequestration, often at high financial and ecological costs. In contrast, an eco-surplus framework prioritizes approaches like forest restoration, because they are multifunctional, simultaneously sequestering carbon, preventing soil erosion, improving water retention, regulating microclimates, and supporting biodiversity—a suite of co-benefits that no single technology can replicate (Seddon et al., 2020).

Second, the shift effectively manages entropy by reducing complexity and allowing for more efficient, evidence-based decision-making. For example, the decision-making paralysis described by GITT is often a product of attempting to impose rigid, “one-size-fits-all” technological models onto dynamic systems. Indigenous and Local Knowledges, however, are intrinsically tied to the ecological, social, and cultural realities of specific landscapes, ensuring that environmental management remains adaptive and contextually relevant (McGregor et al., 2010; Mendes et al., 2020). This place-based approach minimizes entropy (uncertainty) and decision complexity because it evolves through continuous feedback from local conditions, thereby avoiding the catastrophic failures that often result from applying external frameworks to complex ecosystems (McGregor et al., 2010).

Finally, an eco-surplus culture aligns with principles of granularity, relationality, and indeterminacy by promoting humans’ Nature Quotient (NQ), the capacity to perceive, process, and organize information about the interconnections and dynamic interactions among complex information-processing systems, and embracing the self-regulation and adaptability of natural systems (Vuong & Nguyen, 2025). Unlike industrial interventions such as CCS or geoengineering, which require constant energy inputs, maintenance, and human oversight, nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges function as self-organizing systems. For example, forests regenerate through natural succession, wetlands filter pollutants through biological processes, and Indigenous agroforestry systems adapt to local conditions without artificial inputs (Chausson et al., 2020). Their effectiveness stems from working with natural cycles and feedback loops, allowing resilience to emerge organically rather than being engineered at great cost.

The eco-surplus transformation framework

To operationalize an eco-surplus culture and prevent a relapse into destructive patterns, we introduce the eco-surplus transformation framework. This framework is built upon a non-negotiable core logic: the semiconducting principle of value exchange. This principle stipulates that while environmental value (e.g., a restored ecosystem) can be converted into recognized economic and social value, monetary value cannot be used to offset or justify environmental harm (Vuong, 2021a). Like a semiconductor that allows an electrical current to flow in only one direction, this principle makes the flow of value strictly regenerative.

Figure 2 below illustrates how the semiconducting principle functions as the central intervention in the eco-surplus transformation framework. The framework illustrates the complete pathway from the problem (eco-deficit culture with biased information filters leading to the innovation curse) through the intervention (semiconducting principle) to the solution (eco-surplus culture with corrected filters), and finally, the toolkit (governance matrix for implementation). The semiconducting principle corrects the biased filter by systematically prioritizing proven solutions, such as nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledge practices, while constraining speculative technologies to targeted applications and blocking destructive actions that create environmental debt.

Applying the semiconducting principle translates into a clear, three-tiered hierarchy of climate action that ensures resources are allocated with maximum efficiency:

Tier 1: prevent environmental debt and destruction (highest priority)

The most logical first step is to significantly limit activities that create new carbon debt and contribute to irreversible ecosystem loss. This includes phasing out new fossil fuel projects, reducing deforestation, and curbing the overconsumption that drives resource depletion. As research confirms, protecting primary forests, which are irreplaceable carbon sinks, is vastly more cost-effective than attempting to repair damage after it has occurred (Nelson et al., 2023).

Tier 2: scale proven, cost-effective solutions (second priority)

Once active destruction is stopped, focus shifts to expanding proven, low-cost solutions. This tier is dominated by nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges, such as regenerative agriculture and community-led conservation. These approaches offer high returns at a fraction of the cost of industrial alternatives; for example, Indigenous-managed lands consistently demonstrate superior biodiversity outcomes compared to top-down conservation efforts (Garnett et al., 2018).

Tier 3: target technological interventions (lowest priority)

High-risk, high-cost technologies like geoengineering and carbon capture should be treated as last resorts. They are reserved only for residual problems that cannot be solved through the first two tiers. This approach minimizes the wasteful tendencies of the innovation curse by prioritizing proven, effective solutions over speculative fixes.

Pathways to implementation

The three-tiered hierarchy of climate action, derived from the semiconducting principle, provides a clear and rational plan for prioritizing solutions. However, this hierarchy cannot be implemented within the existing eco-deficit governance systems that created the problem. Operationalizing this prioritized approach—halting destruction, scaling proven solutions, and targeting technology as a last resort—requires a fundamental shift in the institutional rules that govern innovation, participation, and accountability.

To guide this transformation, we have developed the Eco-Surplus Governance Matrix, presented in Table 1. Grounded in scholarship from environmental justice, responsible innovation, and, crucially, Indigenous studies, this matrix serves as both a diagnostic tool and a practical toolkit. As Table 1 details, it contrasts the flawed characteristics of eco-deficit and eco-surplus approaches across five critical governance principles that determine how societies process information, allocate resources, and make environmental decisions.

Translating these governance principles into practice requires coordinated action across four interconnected pathways. The first step is to build hybrid knowledge systems that enact the principle of Knowledge Valuation. This represents a fundamental shift in environmental governance, moving beyond extractive consultation toward genuine knowledge co-production (Bednarek et al., 2018). To overcome institutional inertia, boundary-spanning mechanisms must be created to facilitate collaboration between researchers, Indigenous Nations and local communities, and policymakers, ensuring that sustainability governance does not remain disconnected from the ecological intelligence embedded in place-based knowledge systems (Fletcher et al., 2021). This is directly linked to empowering community leadership and actualizing the principle of Participation & Power. This requires moving beyond mere participation to active engagement in Indigenous resurgence and self-determination, recognizing the inherent right of communities to lead and make decisions about their own lands and futures (Simpson, 2017; Whyte, 2020). Supporting Indigenous-led conservation projects, community-managed forests, and participatory mapping initiatives has demonstrated higher ecological success rates and greater community resilience compared to top-down approaches (Nelson et al., 2023).

With valued knowledge and empowered leadership in place, it becomes possible to transform economic and legal frameworks to align with the Innovation Goal of Relational Well-being and enforce Accountability. This requires moving beyond conventional growth-oriented indicators like GDP toward frameworks that capture long-term ecosystem stability and intergenerational sustainability (Farley & Voinov, 2016). Legal frameworks must be strengthened to protect Indigenous and Local Knowledges from biopiracy and ensure equitable benefit-sharing (Ogar et al., 2020). For example, financial mechanisms like Payment for Ecosystem Services must be restructured to remove bureaucratic barriers and center Indigenous leadership, ensuring fair compensation for environmental stewardship rather than favoring intermediaries (Blackman & Veit, 2018). Finally, these domestic reforms must be supported by aligned multi-scale governance to ensure Transparency and policy coherence. Global agreements must translate into legally binding national actions that prioritize nature-based solutions and Indigenous and Local Knowledges, addressing the enforcement gaps that allow market-driven solutions to dominate (Haenssgen et al., 2023). A key driver of this transformation is educational reform that integrates place-based learning to foster deeper ecological consciousness (Gray & Sosu, 2020), and, crucially, upholding principles of Indigenous Data Sovereignty that affirm community control over information about their lands and resources (Rainie et al., 2019).

Ultimately, the pathways outlined here offer a grounded blueprint for cultivating an eco-surplus culture. By aligning institutional governance with the semiconducting principle and embedding the justice-oriented values of the Governance Matrix, this approach directly addresses root causes of the innovation curse: the biased information filters and misplaced priorities diagnosed at the outset of our framework. The practical reforms—from building hybrid knowledge systems to ensuring Indigenous data sovereignty—are the tangible means of making the three-tiered hierarchy of climate action operational. This governance model, therefore, does not merely suggest alternatives; it systematically redirects attention and resources away from speculative technologies and toward prevention and the scaling of effective, context-based solutions. In doing so, it provides the institutional foundation for a more just, ecologically sound, and resilient future.

Conclusion

This study has critically examined the innovation curse that dominates contemporary climate change discourse and implementation strategies. Our analysis of Carbon Capture and Storage, bioplastics, and glacier geoengineering reveals a consistent pattern of high implementation costs, energy-intensive operations, and unintended consequences that often undermine their sustainability benefits. These technologies exemplify an eco-deficit culture that prioritizes end-of-pipe solutions over addressing systemic drivers of environmental degradation.

Through the application of Granular Interaction Thinking Theory, we theorized how this paradigm increases informational entropy and system inefficiencies, driven by economic incentives and institutional biases that favor proprietary innovations over time-tested ecological practices. To counter this, we proposed the Eco-Surplus Transformation Framework, a systematic approach designed to repair these flawed institutional filters. The core of this framework is the semiconducting principle, which enforces a regenerative flow of value and establishes a clear, three-tiered hierarchy of climate action: first, halt environmental destruction; second, scale proven, nature-based solutions; and third, use targeted technology only as a last resort.

To make this hierarchy operational, we developed the Eco-Surplus Governance Matrix, a proposed toolkit for institutional reform. This matrix embeds principles of epistemic, procedural, and distributive justice into governance, providing concrete pathways to dismantle the biases that perpetuate the innovation curse. The transition requires building hybrid knowledge systems, reforming economic and legal frameworks to value relational well-being, aligning multi-scale governance, and, crucially, empowering community self-determination.

Looking forward, future research should focus on the practical implementation of this framework. This includes studies on operationalizing the Governance Matrix across different cultural and political contexts and developing integrated valuation methods that capture the holistic benefits of Tier 1 and Tier 2 solutions. Further research is also essential on how to facilitate genuine knowledge co-production without reducing Indigenous and Local Knowledges to an extractive resource for Western science.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our application of Granular Interaction Thinking Theory to climate governance represents an exploratory theoretical framework that requires empirical validation through real-world case studies. Second, while we identify information-processing mechanisms as a key factor in the marginalization of Indigenous and Local Knowledges, we recognize this as one factor among multiple historical and structural causes, including colonialism, assimilation policies, and systemic discrimination. Third, the Eco-Surplus Transformation Framework we propose is conceptual and needs testing through pilot implementations to assess its practical viability across different cultural, political, and economic contexts. Finally, our analysis focuses primarily on three technological interventions (CCS, bioplastics, and glacier geoengineering) and may not fully capture the complexity of innovation biases across all climate technologies. Future research should address these limitations through empirical studies, broader technological analyses, and collaborative implementation with Indigenous communities and policymakers.

For policymakers, this study serves as a call to move beyond technological solutionism. It underscores the urgent need to redirect funding toward Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, reform intellectual property laws to protect communal knowledge, and establish institutional structures that support the co-production of knowledge as outlined in our matrix.

The path forward lies not in abandoning technological innovation but in reorienting our innovation paradigms to work with, rather than against, natural systems. By addressing the structural biases that favor high-cost technologies, societies can adopt more sustainable and equitable strategies. The eco-surplus framework offers a theoretical blueprint for this transition, enabling us to preserve and revitalize the sophisticated ecological intelligence that has sustained human societies for millennia and is essential for a resilient future.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Abe MM, Martins JR, Sanvezzo PB, Macedo JV, Branciforti MC, Halley P, Brienzo M (2021) Advantages and disadvantages of bioplastics production from starch and lignocellulosic components. Polymers 13(15):2484, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/13/15/2484

Adger WN, Paavola J, Huq S, Mace MJ (2006) Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change. MIT Press

Agyeman J (2005) Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice. NYU Press, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfxz0

Albertz M, Stewart SA, Goteti R (2023) Perspectives on geologic carbon storage [Review]. Front Energy Res 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2022.1071735

Alevropoulos-Borrill A, Golledge NR, Cornford SL, Lowry DP, Krapp M (2024) Sustained ocean cooling insufficient to reverse sea level rise from Antarctica. Commun Earth Environ 5(1):150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01297-8

Allemann MN, Tessman M, Reindel J, Scofield GB, Evans P, Pomeroy RS, Simkovsky R (2024) Rapid biodegradation of microplastics generated from bio-based thermoplastic polyurethane. Sci Rep. 14(1):6036. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56492-6

Arora A, Cohen WM, Walsh JP (2016) The acquisition and commercialization of invention in American manufacturing: Incidence and impact. Res Policy 45(6):1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.02.005

Aswani S, Lemahieu A, Sauer WHH (2018) Global trends of local ecological knowledge and future implications. PLoS One 13(4):e0195440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195440

Batchelor CL, Christie FDW, Ottesen D, Montelli A, Evans J, Dowdeswell EK, Dowdeswell JA (2023) Rapid, buoyancy-driven ice-sheet retreat of hundreds of metres per day. Nature 617(7959):105–110. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05876-1

Beck A (2021) The Yurok Tribe Is Using California’s Carbon Offset Program to Buy Back Its Land. Yes Magazine. https://www.yesmagazine.org/environment/2021/04/19/california-carbon-offset-program-yurok-tribe-land-back

Bednarek AT, Wyborn C, Cvitanovic C, Meyer R, Colvin RM, Addison PFE, Leith P (2018) Boundary spanning at the science–policy interface: the practitioners’ perspectives. Sustain Sci 13(4):1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0550-9

Bellamy R, Osaka S (2020) Unnatural climate solutions? Nat Clim Change 10(2):98–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0661-z

Bishop G, Styles D, Lens PNL (2021) Environmental performance of bioplastic packaging on fresh food produce: a consequential life cycle assessment. J Clean Prod 317:128377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128377

Blackman A, Veit P (2018) Titled Amazon indigenous communities cut forest carbon emissions. Ecol Econ 153:56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.06.016

Bridgewater P (2018) Whose nature? What solutions? Linking ecohydrology to nature-based solutions. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol 18(4):311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2018.11.006

Burger J, Nöhl J, Seiler J, Gabrielli P, Oeuvray P, Becattini V, Bardow A (2024) Environmental impacts of carbon capture, transport, and storage supply chains: status and the way forward. Int J Greenh Gas Control 132:104039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2023.104039

Campos-Silva JV, Peres CA (2016) Community-based management induces rapid recovery of a high-value tropical freshwater fishery. Sci Rep. 6(1):34745. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34745

Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR principles for indigenous data futures. Sci Data 8(1):108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0

Chausson A, Turner B, Seddon D, Chabaneix N, Girardin CAJ, Kapos V, Seddon N (2020) Mapping the effectiveness of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation. Glob Change Biol 26(11):6134–6155. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15310

Chen S, De Bruyne C, Bollempalli M (2020) Blue economy: community case studies addressing the poverty–environment nexus in ocean and coastal management. Sustainability 12(11):4654, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/11/4654

Colwill JA, Wright EI, Rahimifard S, Clegg AJ (2012) Bio-plastics in the context of competing demands on agricultural land in 2050. Int J Sustain Eng 5(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19397038.2011.602439

Courtois V (2024) Indigenous-led conservation is key to achieving COP16 biodiversity goals. Indigenous Leadership Initiative. https://www.ilinationhood.ca/blog/meetingcop16goalswithindigenousledconservation

Cruz RMS, Krauter V, Krauter S, Agriopoulou S, Weinrich R, Herbes C, Varzakas T (2022) Bioplastics for Food Packaging: Environmental Impact, Trends and Regulatory Aspects. Foods 11(19):3087, https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/19/3087

Dai X, Tang J, Huang Q, Cui W (2023) Knowledge spillover and spatial innovation growth: evidence from China’s Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability, 15(19)

Darwin C (2003) On the Origin of Species (Knight, D Ed. Reprint ed.). Routledge

Darwin C, Wallace AJJOTPOTLSOLZ (1858) On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. J Proc Linn Soc Lond Zool 3(9):45–62

Davis H, Todd Z (2017) On the importance of a date, or, decolonizing the anthropocene. ACME: Int J Crit Geographies 16(4):761–780. https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v16i4.1539

Davoodi S, Al-Shargabi M, Wood DA, Rukavishnikov VS, Minaev KM (2023) Review of technological progress in carbon dioxide capture, storage, and utilization. Gas Sci Eng 117:205070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgsce.2023.205070

de Coninck H, Benson SM (2014) Carbon dioxide capture and storage: issues and prospects. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 39(2014):243–270

de Sousa Santos B (2014) Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Routledge. https://unescochair-cbrsr.org/pdf/resource/Epistemologies_of_the_South.pdf

Deng H, Bielicki JM, Oppenheimer M, Fitts JP, Peters CA (2017) Leakage risks of geologic CO2 storage and the impacts on the global energy system and climate change mitigation. Clim Change 144(2):151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2035-8

Dey M, Jambhale R (2025) Bioplastics statistics by material type, usage, region and trends. Sci-Tech Today. https://www.sci-tech-today.com/stats/bioplastics-statistics-updated

Drury M, Fuller J, Keijzer M (2022) Biodiversity communication at the UN Summit 2020: blending business and nature. Discourse Commun 16(1):37–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/17504813211043720

Duffey A, Irvine P, Tsamados M, Stroeve J (2023) Solar geoengineering in the polar regions: a review. Earth’s Future 11(6):e2023EF003679. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003679

Eco Jurisprudence Monitor (2014) New Zealand Te Urewera Act 2014. Eco Jurisprudence Monitor. https://ecojurisprudence.org/initiatives/te-urewera-act-2014/

Ens E, Pert P, Clarke P, Budden M, Clubb L, Doran B, Wason S (2015) Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: review and insight from Australia. Biol Conserv 181:133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.008

Escobar N, Britz W (2021) Metrics on the sustainability of region-specific bioplastics production, considering global land use change effects. Resour Conserv Recycling 167:105345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105345

Escobar N, Haddad S, Börner J, Britz W (2018) Land use mediated GHG emissions and spillovers from increased consumption of bioplastics. Environ Res Lett 13(12):125005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaeafb

Farley J, Voinov A (2016) Economics, socio-ecological resilience and ecosystem services. J Environ Manag 183:389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.065

Field L (2025) Ice Preservation. In Geoengineering and Climate Change (pp. 287-295). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394204847.ch17

Fletcher M-S, Romano A, Connor S, Mariani M, Maezumi SY (2021) Catastrophic Bushfires, Indigenous Fire Knowledge and Reframing Science in Southeast Australia. Fire, 4(3)

Fricker M (2007) Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

Gagnon VS, Ravindran EH (2023) Restoring human and more-than-human relations in toxic riskscapes: in perpetuity within Lake Superior’s Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Sand Point. Ecol Soc, 28(1), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-13655-280102

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Molnár Z, Robinson CJ, Leiper I (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat Sustain 1(7):369–374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0100-6

Geels FW (2011) The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: responses to seven criticisms. Environ Innov Soc Transit 1(1):24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002

Gerassimidou S, Martin OV, Chapman SP, Hahladakis JN, Iacovidou E (2021) Development of an integrated sustainability matrix to depict challenges and trade-offs of introducing bio-based plastics in the food packaging value chain. J Clean Prod 286:125378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125378

Gertner J (2024) Can $500 Million Save This Glacier? In. The New York Times

Goldstein BD (2001) The precautionary principle also applies to public health actions. Am J Public Health 91(9):1358–1361. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.9.1358

Gómez-Baggethun E (2022) Is there a future for indigenous and local knowledge? J Peasant Stud 49(6):1139–1157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1926994

Gray D, Sosu EM (2020) Renaturing Science: The Role of Childhoodnature in Science for the Anthropocene. In Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A, Malone, K & Barratt Hacking E (Eds.), Research Handbook on Childhoodnature : Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research (pp. 557-585). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67286-1_38

Gray KA (2021) Climate Action: The Feasibility of Climate Intervention on a Global Scale. In Burns, W, Dana, D & Nicholson SJ (Eds.), Climate Geoengineering: Science, Law and Governance (pp. 33-91). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72372-9_3

Gupta A (2010) Transparency in global environmental governance: a coming of age? Glob Environ Politics 10(3):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_e_00011

Haenssgen MJ, Leepreecha P, Sakboon M, Chu T-W, Vlaev I, Auclair E (2023) The impact of conservation and land use transitions on the livelihoods of indigenous peoples: a narrative review of the northern Thai highlands. Policy Econ 157:103092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103092

Hahnel UJ, Arnold O, Waschto M, Korcaj L, Hillmann K, Roser D, Spada H (2015) The power of putting a label on it: green labels weigh heavier than contradicting product information for consumers’ purchase decisions and post-purchase behavior. Front Psychol 6:1392. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01392

Hanbury S (2024) Billions in public funds ‘wasted’ on carbon capture projects, report finds. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/billions-in-public-funds-wasted-on-carbon-capture-projects-report-finds/

Harmsworth G, Awatere S, Robb M (2016) Indigenous M?ori values and perspectives to inform freshwater management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ecol Soc, 21(4). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269997

Helm LT, Venier-Cambron C, Verburg PH (2025) The potential land-use impacts of bio-based plastics and plastic alternatives. Nat Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01492-7

Hertog T (2023) On the origin of time: Stephen Hawking’s final theory. Random House. https://www.google.com/books/edition/On_the_Origin_of_Time/llBTEAAAQBAJ