Abstract

Individuals may experience psychological distress and feel trapped as a result of adversity in their lives. Individuals may regret their decisions, which may worsen the situation. Individuals must be more resilient in order to survive and adapt to these conditions. The goal of this study was to see if psychological resilience and regret could mediate the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment. The relationships between these variables have never been examined before, and they are addressed for the first time in the current study. Data were gathered through the voluntary participation of 94 male and 243 female university students. Structural Equation Modeling was used to conduct mediation analysis. According to the findings, psychological resilience and regret played a similar mediating role between psychological distress and entrapment. According to the model, psychological distress predicted entrapment and regret positively, but psychological resilience negatively. Individuals experiencing psychological distress are not resilient and experience regret, which may make them more resistant to feelings of entrapment and risks such as suicide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to mainstream media reports, traumatic events such as natural disasters, sexual assault, and child abuse occur frequently around the world and cause significant psychological damage to individuals and societies (Lowe et al., 2015). Individuals’ psychological resilience is viewed as a process of developing psychological and physiological adaptations to better cope with trauma, rather than a trait that allows them to overcome these traumas with as little damage as possible (Atkinson, 2015; Masten, 2001). On the other hand, traumatic events can result in psychological problems. These include post-traumatic stress disorder, severe psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and somatization (Green, 1990). Psychological distress is widely recognized as an indicator of population mental health in public health, population surveys, and epidemiological studies, as well as an outcome in clinical research and intervention studies (Drapeau et al. 2012). Psychological distress is an emotional state that has a negative impact on well-being (Winefield et al., 2012). In other words, high levels of psychological distress indicate a decrease in overall well-being. It is characterized primarily by loss of interest, sadness, and hopelessness in depression, and restlessness and tension in anxiety (Mirowsky & Ross 2002). According to Buchanan et al. (2016), distress has a significant impact.

One emotional response associated with distress is regret. Ermiş and Bayraktar (2021) found that regret can lead to negative outcomes. Individuals experience negative emotions when they believe they made the wrong decision. According to Roese and Summerville. (2005), there is a high rate of regret among these individuals. Regret is an adverse feeling that occurs when a person realizes or imagines that he or she would have been better off if they had made a different decision. Psychological distress is associated with regret and depression (Roese et al., 2009). According to Buchanan et al. (2016), regret can lead to significant changes.

When one takes into account the extent of pessimism regarding the future, social withdrawal, and isolation of psychological distress, these concepts can be seen as semantically related to entrapment. Entrapment signifies an individual’s conviction that they are powerless to alter unfavorable life circumstances and an urgent emotional need to flee from social conditions (Gilbert & Allan, 1998; Massé, 2000). Entrapment has been linked to psychological distress and mental health issues including suicide, depression, and anxiety, according to research (Cramer et al., 2019; Eskin et al., 2016; Brown et al., 1995). A collection of distressing cognitive and physical manifestations that are commonly linked to typical mood swings in the majority of individuals and which, in certain instances, may serve as an indication of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, somatization disorder, or other clinical conditions (American Psychological Association n.d.).

Consistent with the concept of entrapment, regret has been found to be correlated with adverse mental health manifestations such as elevated levels of anxiety and tension, depression, and distress (Roese et al., 2009). Regret, entrapment, and psychological distress have been linked to identical concepts in distinct research investigations, which is to be expected. An unfulfilled need or a stressor that induces distress in the individual, as well as the fight-or-flight response upon perceiving it as a threat, are precursors to psychological distress (Selye, 1974). The fight-or-flight response has been widely acknowledged as an evolved, fundamental defense mechanism (Gilbert & Gilbert, 2003). Entrapment is a condition characterized by obstructed or halted flight behaviors and is conceptualized similarly to psychological distress (Dixon, 1998; Gilbert, 2001). It is evident that regret, psychological distress, and entrapment merit a collective analysis.

Psychological resilience is an additional response that can be cultivated in response to stress, in addition to psychological distress. The correlation between psychological resilience levels and the extent to which certain individuals experience psychological distress in response to stress varies among individuals (Pakalniškienė et al., 2016). Psychological resilience, which is one of several variables that can influence how individuals react to stress, is characterized by the capacity to achieve success despite obstacles or to recuperate from adversity (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Pertaining to this, psychological resilience is a significant factor in elucidating the varying reactions that individuals may have to identical occurrences. Hence, resilience can be defined as the capacity of the majority of individuals to endure extreme levels of stress and trauma while sustaining typical psychological and physical operations and avoiding the development of severe mental disorders (Russo et al., 2012). Individuals must possess a significant degree of psychological resilience to ensure the maintenance of a psychologically sound existence. Nonetheless, psychological distress is inversely associated with psychological resilience, according to a number of studies (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Kiziela et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2016). It is established from these studies that individuals who possess psychological resilience encounter diminished levels of psychological distress. Psychotherapeutically treated clinical samples of patients with affective and anxiety disorders exhibited a progressive reduction in all symptoms of psychological distress and an increase in psychological resilience (Pakalniškienė et al., 2016).

The resilience-based approach, as opposed to concentrating on the mechanisms that cause distress, advocates for an examination of the elements that empower people to endure stressors (Johnson et al., 2017). Resilience, as opposed to psychological distress, is characterized by active coping mechanisms, social attachment, optimism, hope, resourcefulness, and adaptability (Joseph & Linley, 2006). Demoralization and pessimism regarding the future, anguish and stress, self-depreciation, social withdrawal and isolation, somatization, and withdrawal from oneself are the six general types of psychological distress (Massé, 2000). Evidently, resilience is in direct opposition to the aforementioned. Furthermore, in contrast to resilience and psychological distress, individuals experiencing entrapment frequently report feelings of solitude and seclusion (Gilbert & Gilbert, 2003). In addition, the correlation between entrapment and suicidal ideation may be strengthened or weakened by resilience (O’Connor & Portzky, 2018). The significance of resilience in mitigating suicidal ideation is growing in prominence as a subject of investigation and emphasis in suicide prevention and research (Zhang et al., 2022). Similarly, in contrast to psychological distress and entrapment, there exists substantial evidence suggesting that resilience is negatively correlated with stress, anxiety, and depression (McGarry et al., 2013). Based on the comprehensive information provided, it is evident that psychological resilience is a multifaceted concept that encompasses both entrapment and psychological distress.

As a result, people are more likely to experience stressful situations that have long-term consequences. Unwanted situations such as psychological distress, entrapment, and regret may develop in reaction to these negative life occurrences. There is hope that people will be able to overcome these negative influences with resilience. Understanding why some people acquire psychological problems while others are more adaptable necessitates taking into account individual differences in psychological vulnerability. In this regard, the current study is guided by the vulnerability stress models (Ingram & Luxton, 2005), which holds that the psychological impact of traumatic life events is largely determined by a person’s vulnerability level. Protective elements, such as psychological resilience, can buffer or minimize the negative consequences of stress. Regret is defined as feeling distressed and upset over one’s mistakes (Landman, 1987). Therefore, by viewing the past more negatively, a high degree of distress may intensify the sense of regret. Regret could be recognized as a vulnerability in the context of vulnerability stress models (Ingram & Luxton, 2005). Therefore, regret can be used to justify entrapment as a factor that facilitates and predisposes a person to a disordered condition. Protective factors such as resilience have been suggested to buffer the effects of stress. However, this study considers resilience and regret as indirect psychological mechanisms that explain the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment. Rather than interactional or contingent effects, the research model focuses on the internal emotional and cognitive pathways that allow distress to lead to a sense of disengagement. In view of the relevant scholarly literature, it is judged worthwhile to study the interconnected conceptions of psychological distress, resilience, regret, and entrapment within the framework. As a result, the hypotheses investigated in the current study were developed.

H1. Psychological distress has a significant positive relationship with regret and entrapment and a significant negative relationship with resilience.

H2. There is a mediating role of psychological resilience between psychological distress and entrapment.

H3. There is a mediating role of regret between psychological distress and entrapment.

H4. There is a parallel mediating role of psychological resilience and regret between psychological distress and entrapment.

Method

Participants and procedure

A total of 337 Turkish university students from 32 different cities, 94 males and 243 females, participated in the study. A sample size of more than 200 is deemed adequate for this type of research (Singh et al., 2016). Participants were told about the study’s aim, substance, and confidentiality standards, and they volunteered to participate. Individuals who read and agreed to the informed consent paragraph at the start of the online survey form were considered eligible to participate in the study. The questionnaire took about 10–12 min to complete, and data was collected using Google Forms. No incentive or reward was provided.The data was collected through online and social media announcements.

Measures

K-10 psychological distress scale

The instrument was designed by Kessler et al. (2002) to assess psychological distress, which is an emotional state of harm that adult individuals experience and is characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as four-week levels of anger, agitation, and psychological fatigue. The adaptation study that Altun et al. (2019) undertook was in the Turkish language. The scale possesses a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.95. In the instructions of the scale, the participants were asked to indicate how often they felt the emotion in each item by thinking about their feelings in the last 30 days. The response options on the one-dimensional, ten-item scale are classified as 5-point Likert-type items, ranging from 1 (indicating never) to 5 (indicating always). The scale yields a range of 10–50 points, with higher scores signifying greater levels of psychological distress.

Entrapment scale short-form (E-SF)

The Turkish implementation of the De Beurs et al. (2020) scale was examined and approved by Türk et al. (2024). When applied to samples of adults, the scale with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88 is appropriate. It consists of four items and is one-dimensional. The goodness of fit indices of the scale reveal that the scale shows a good fit (χ2 = 6.125, df = 2, p < 0.05; χ2/df = 3.06; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.99; IFI = 0.99; GFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.98; RFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.013). In the scale instructions, participants are asked to rate how much they agree with the situations in the scale items. The Likert scale consists of five points for responses (0 = It doesn’t suit me at all, 4 = It suits me perfectly). The minimum achievable score on the scale is zero, while the maximum possible score is sixteen. Greater scores are indicative of greater entrapment.

Brief psychological resilience scale

The instrument was created by Smith et al. (2008) with the purpose of assessing the psychological resilience of adults. The research on Turkish adaptation was undertaken by Doğan (2015). The calculated coefficient of internal consistency for the Turkish version is 0.83. x2/sd (12.86/7) = 1.83, NFI = 0.99, NNFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99, RFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, and SRMR = 0.03 were the goodness-of-fit indices for the scale. The 5-point Likert scale comprises a single dimension and six items: inappropriate (1), not at all inappropriate (2), somewhat inappropriate (3), appropriate (4), and completely inappropriate (5). Scores ranging from 6 to 30 are attainable using the scale.

Regret elements scale

For use with adult samples, Buchanan et al. (2016) developed this method. A Turkish cultural adaptation was made by Aktu (2023). The reliability coefficient of the scale, as determined by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.92. The scale comprises a total of ten items, of which two, each consisting of five items, gauge the affective and cognitive dimensions. It was determined that the fit indices of the scale were satisfactory (x2/df = 2.09, RMSEA = 0.043, SRMR = 0.07, NNFI/TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.92). The scale instructions include the sentence “Regarding the decisions I make in my life…”, and participants answered the scale items with this instruction in mind. The response options span a 7-point Likert scale, which reads “strongly agree” (7) and “strongly disagree” (1). The scale yields scores that exhibit a range of 10 to 70. It is evident that as the scores acquired from the scale rise, individuals perceive a greater degree of regret.

Data analysis

The objective of the study was to establish a correlation between university students’ levels of psychological distress, entrapment, resilience, and regret. The research encompassed the utilization of SPSS, JASP, and AMOS software applications. Descriptive statistics, normality analysis, and reliability assessment were conducted using JASP, while correlation analysis was carried out using SPSS. Following the correlation analysis’s confirmation of significant results, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted. SEM, which is conducted utilizing the AMOS program, is considered a highly effective quantitative analysis technique due to its capability of generating decisions based on multiple parameters (Kline, 2011). A two-stage SEM was utilized in accordance with the guidelines provided by Kline (2011). The initial phase involved assessing the verification status of the measurement model, which examines the interconnections among indicator variables, latent variables, and the interrelationships among these latent variables. Following validation of the measurement model, the hypothetical structural model was evaluated. To assess the outcomes of the SEM, the indices of goodness of fit suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) were taken into account. Besides degrees of freedom and chi-square (X2), the following metrics were computed in this context: GFI, RFI, CFI, NFI, IFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA. Critical values include a χ2 to degrees of freedom ratio of less than 5, GFI, RFI, CFI, NFI, IFI, and TLI values above .90, and SRMR and RMSEA values below .08 (Hu & Bentler 1999; Tabachnick & Fidell 2001). Moreover, AIC and ECVI values were assessed alongside the chi-square difference test to determine which model was superior among multiple models in SEM. The model with the smallest AIC and ECVI values is deemed superior (Akaike, 1987; Browne & Cudeck 1993).

Since the measurement instruments for the concepts of psychological distress, entrapment, and resilience were unidimensional, the item partitioning method was used in SEM. The parcellation method, which is applied to personality trait concepts, increases the reliability of the scales, decreases the number of observed variables, and facilitates the manifestation of a normal distribution (Nasser-Abu Alhija & Wisenbaker, 2006). Parcellation produced two dimensions pertaining to psychological distress, namely entrapment and resilience.

Bootstrapping was employed in conjunction with SEM in this investigation to bolster the significance of mediation and provide robust corroboration (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). The sample size was increased to 10,000 through the bootstrapping procedure, and confidence intervals (C.I.I.) were computed using the bootstrap value (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The observed lack of zero values within the confidence intervals provides further evidence that the mediation under consideration is substantially significant.

Results

The results of correlation analysis and descriptive statistics are presented initially in this section. Following this, the outcomes of the structural and measurement models are displayed. The outcomes of the bootstrapping procedure are subsequently detailed.

Table 1 provides descriptive and correlation statistics (arithmetic mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values) pertaining to the variables. Upon examination of Table 1, it becomes evident that the skewness (ranging from -.173 to.395) and kurtosis (ranging from -.722 to.054) values of the variables fall within the acceptable ranges specified by Finney and DiStefano (2006) for normality criteria of ±2 for skewness and ±7 for kurtosis.

A statistically significant positive relationship is observed between psychological distress and entrapment (r = .75 p < .001), between psychological distress and regret elements (r = .65 p < .001), and between entrapment and regret elements (r = .71 p < .001), as indicated by the relationships in Table 1. There is a significant positive relationship between psychological distress and resilience (r = -.47 p < .001), entrapment and resilience (r = -.50 p < .05), and regret elements and resilience (r = -.40 p < .001).

Once significant relationships were identified between the concepts, the measurement model was initiated. The measurement model comprises four latent variables, namely regret, entrapment, psychological distress, and entrapment, with a total of eight observed variables associated with each latent variable. The fit values, as indicated by the results, are detailed in Table 2. In general, the fit values are satisfactory. Further, it is acknowledged that the factor loadings exhibit a range of values from 0.73% to 0.96%. Consequently, the observed values are indicative of the latent variables.

The structural model was utilized to examine the effectiveness of a model in which resilience and regret function as full mediators between psychological distress and entrapment. The comprehensive mediation approach makes the assumption that psychological distress and entrapment are not directly related. Furthermore, it considers the influence of regret and resilience factors on the prediction of psychological distress. Table 2 displays the fit values of the model in which the elements of regret and resilience are fully mediated. In order to determine the most effective mediator model, partial mediators of resilience and regret were incorporated into the model. The partial mediator model posits that psychological distress and entrapment are connected in a direct manner, with additional mediating factors of resilience and regret. In Table 2, the fit values of the test results are presented. Each model’s fit values are deemed acceptable. The determination of the selected model will be based on the outcomes of the chi-square difference test as well as the AIC and ECVI values.

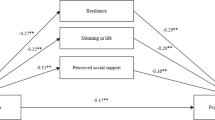

Based on the outcomes of the chi-square difference test used to determine which model components involving regret and resilience would be preferred as full or partial mediators, it is clear that the model benefits significantly from the addition of a direct path connecting psychological distress and entrapment. The chi-square difference test was performed to determine which models would be preferred and if resilience and regret elements served as full mediators or partial mediators. The results indicated that the additional direct path connecting psychological distress and entrapment significantly improves the model (Δx2 = 37,721, sd = 1, p < 0.001). Furthermore, it is observed that the AIC and ECVI values for the partial mediation model are comparatively lower than those for the full mediation model. Preferred among these outcomes was the model in which regret and resilience serve as partial mediators between psychological distress and entrapment. The model’s path coefficients are illustrated in Fig. 1.

The purpose of bootstrapping was to bolster and supplement the research. Consequently, the significance of each direct path coefficient is established. The findings are presented in Table 3.

The levels of resilience and regret elements among university students partially mediate the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment, according to these findings. Furthermore, a parallel mediation occurs between regret and resilience in the context of psychological distress and entrapment.

Discussion

Occasional psychological distress and entrapment may be experienced by individuals due to circumstances including traumatic events and challenging living conditions. The current study involved a sample of university students. Early adulthood, the stage of life in which university students live, necessitates several changes in their living arrangements, relationships, education, and jobs. As a result, adulthood is a vital stage that can cause stress and psychological distress (Matud et al., 2020). Examining the correlation between psychological distress and entrapment, as well as the influence of other concepts in this correlation, is beneficial for determining measures that can be implemented to changing people’s life in a favorable way under more favorable circumstances. There may be occasions when individuals are dissatisfied with the choices they make in their struggle for survival. Regret regarding one’s decisions can thus be an affective state that is susceptible to negative evaluation by others. Conversely, psychological resilience enables an individual to readily adjust to the difficult circumstances that arise throughout their lifetime, which is an exceedingly favorable circumstance. The objective of the present study was to investigate the potential mediating effect of psychological resilience and regret on the association between entrapment and psychological distress. The findings from the analyses suggest that psychological resilience and regret function in a mediating capacity that is parallel to that of entrapment and psychological distress. Put simply, entrapment can be predicted by psychological distress via psychological resilience and regret. The obtained results and the hypotheses developed for the present investigation were evaluated in consideration of the existing relevant literature.

A preliminary examination of the correlation of psychological distress with entrapment, resilience and regret was conducted. The results show that distress is a positive predictor of entrapment and regret. In addition, distress negatively predicts resilience. Consequently, a heightened feeling of psychological distress corresponds to an intensified perception of confinement. Psychological distress is defined as a condition of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms such as hopelessness, sadness, and loss of interest, which are indicative of depression, and restlessness and a sense of tension, which are symptoms of anxiety (Mirowsky & Ross 2002). Suicide has been found to be correlated with psychological distress (Eskin et al., 2016). Entrapment is a concept that has been linked to suicide (Cramer et al., 2019). A positive correlation between psychological distress and entrapment was observed in studies where both variables were considered (Chabbouh et al., 2024; Taliaferro et al., 2020). Entrapment is a psychological state in which a person perceives the circumstances of their existence as being beyond their control, inevitable, and inseparable (Gilbert & Gilbert, 2003). Entrapment, similar to psychological distress, may manifest in response to stressful life circumstances (Brown et al., 1995). Entrapment and psychological distress are both terms that pertain to adverse circumstances experienced by an individual. In addition, past studies have also shown that there is a negative relationship between psychological distress and resilience and a positive relationship between psychological distress between regret (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Roese et al. 2009). The results of the present investigation support previous study findings. Based on the aforementioned evidence, individuals reporting lower levels of psychological distress also tend to report lower levels of entrapment and regret.

The study additionally examined whether the association between entrapment and psychological distress was mediated by psychological resilience. The hypothesis was thus validated, and it was determined that psychological distress served as a partial mediator. Consequently, psychological distress was found to be directly associated with entrapment, and this association was partially mediated by psychological resilience. This topic has been the subject of research in the literature. Psychological resilience is characterized as the capacity to swiftly recover from adversity, such as depression, illness, or other adverse circumstances, as well as to adapt and revert back to one’s previous state (Earvolino‐Ramirez, 2007). Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s capacity to rebound from adversity by sustaining typical psychological and physical functioning, as well as to prevent the development of severe mental illnesses that would otherwise induce distress or entrapment (Russo et al., 2012). The relationship between psychological distress and resilience has been the subject of research. The aforementioned research has established a negative correlation between psychological resilience and distress (Kiziela et al., 2019). Conversely, entrapment has been identified as a risk factor for adverse consequences, including stress, mental health symptoms, and suicidal ideation (Siddaway et al., 2015; Cheon, 2012). Conversely, resilience is a substantial factor in determining whether entrapment and suicidal ideation are strengthened or weakened and is frequently incorporated into suicide prevention research (O’Connor & Portzky, 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). Furthermore, an analysis of the correlation between resilience and depression, anxiety, and stress reveals that, in contrast to psychological distress and entrapment, resilience has a negative association with these constructs (McGarry et al., 2013). On the basis of the foregoing, it is possible to conclude that psychological resilience is a notion that can offer those experiencing psychological distress greater optimism regarding their ability to escape entrapment.

Within the scope of the research, an additional hypothesis was investigated and confirmed to be accurate: regret functions as a mediator between psychological distress and entrapment. The findings derived from the analysis indicate that regret serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between entrapment and psychological distress. To put it simply, psychological distress was both directly and indirectly associated with entrapment, with regret functioning as a partial mediator. Regret can be defined as an individual’s personal discontentment with a previous decision they made and the conviction that they would have been in a more favorable position had they made an alternative choice (Pieters & Zeelenberg, 2007). Regret, which is associated with distress, encompasses the apprehension that a prior decision will not be modified (Ermiş & Bayraktar, 2021; Roese et al., 2009). Research has demonstrated that regret, like psychological distress and entrapment, is correlated with symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression (Kraines et al. 2017; Perdomo 2021; Roese et al. 2009). These studies provide further evidence in favor of the notion that entrapment can be predicted through regret and psychological distress. Given these circumstances, it is conceivable that individuals who undergo significant psychological distress may similarly experience regret and entrapment.

In conclusion, the present study investigated the mediating function of psychological resilience and regret in the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment, as proposed as the main hypothesis. The study’s results indicate that regret and psychological resilience function in parallel as mediators between entrapment and psychological distress. Several studies have established a direct correlation between psychological distress and both entrapment and psychological resilience (Cramer et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2016). Furthermore, the correlation between regret-related concepts and psychological distress and entrapment provides further support for the main hypothesis, which was validated within the parameters of the present investigation. For instance, individuals who experience psychological distress and entrapment are known to report feelings of loneliness and isolation; conversely, those who exhibit psychological resilience demonstrate the exact opposite (Gilbert & Gilbert, 2003; Joseph & Linley, 2006; Massé, 2000). Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that suicidal ideation is correlated with psychological distress (Eskin et al., 2016). In addition, the relationship between entrapment and suicidal thoughts may be influenced by resilience (O’Connor & Portzky, 2018). Given the aforementioned factors and the contributions of psychological resilience and regret to the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment, it is reasonable to hypothesize that individuals with higher resilience and lower regret tend to report lower levels of entrapment. Resilience and satisfaction with one’s past decisions appear to be related to lower levels of entrapment, which has been associated with serious mental health risks, including self-harm. This forecast might serve as an indication to have essential caution.

Conclusion

The study’s findings established the partial mediating function of regret and resilience components in the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment. That is to say, psychological distress serves as a direct predictor of entrapment, whereas regret and resilience factors predict entrapment indirectly. It was discovered that psychological distress among college students is a variable that can increase entrapment by contributing to an increase in regret elements and a decrease in psychological resilience. Psychological distress is a quantitative framework utilized in the literature to elucidate the interconnections among the notions of entrapment, resilience, and regret components. The capacity of individuals to regulate their psychological distress can have both direct and indirect effects on their regret management capabilities. Similarly, the robustness of their psychological resilience can also have an influence on their levels of entrapment. Pupils may encounter psychological distress at some point in their lives. Enhancing an individual’s psychological resilience and developing the capacity to regulate regret both emotionally and cognitively during moments of remorse could potentially amplify the degree of entrapment experienced. Psychoeducation programs that foster psychological resilience and emotional control in individuals will have a positive impact on psychological distress and entrapment.

Limitations and Future Research

While the research findings make a valuable contribution to the field, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. To commence, the data utilized in this investigation were gathered via self-reported measurement instruments. This finding suggests that the explanatory power of the data is limited to the capabilities of the measurement instruments employed. In subsequent investigations, alternative methodologies such as peer assessment, observation, interviews, and self-report-based measurement instruments may be employed. Although online self-report questionnaires have some limitations (e.g., tendency to respond subjectively, uncontrolled environment), this method was found to be appropriate for the current study. Moreover, the online format facilitated voluntary and anonymous participation, increasing accessibility. An additional constraint pertains to the research methodology. Despite the utilization of structural equation modeling, which is known to yield robust results when applied to quantitative methods, and the bootstrapping of 10,000 samples to increase the sample size, it is imperative to exercise caution and prudence when attributing causes and effects due to the cross-sectional design of the sample and the quantitative method employed. One additional limitation concerns the gender distribution in the sample. Furthermore, the study’s participants were limited to Turkish university students. Given this circumstance, care must be taken when extrapolating the findings. Future studies that look at the existing research variables must be carried out using various samples. As 72% of the participants were female, this gender imbalance may limit the generalizability of the findings, especially in terms of gender-specific psychological processes.

While the structural equation model does predict psychological distress in response to entrapment, resilience and regret components, and regret and resilience in relation to entrapment, longitudinal and experimental research might be necessary or needed to prove or explore whether there exist causal relationships. An additional constraint of this research is that it is restricted to the aforementioned variables. One can investigate the mediating role of various concepts in the relationship between psychological distress and entrapment. Resilience and regret were used to explain how distress affects entrapment in this study. Potential moderating effects were not examined. Future studies that employ moderation analyses to identify interactional effects will expand similar theoretical models. On the other hand, individuals may require a variety of skills in order to adapt to life. In addition, it is possible to develop programs that aim to enhance psychological resilience. Programs that manipulate the emotions of individuals through the use of regret elements are possible to develop.

Practical Implications

The study’s findings reveal that psychological distress is linked to entrapment, with resilience and regret acting as mediators. These findings can be used to inform a variety of individual and institutional activities. Individuals who build resilience skills may be better able to withstand the harmful impacts of psychological distress. In this context, psychoeducation programs, group-based psychological counseling methods, and individual counseling services can be designed to boost resilience, particularly among university students. At the institutional level, educational institutions and counseling centers can develop content to help students cope with regret in a healthier way. Workshops or self-compassion-themed trainings that support students’ decision-making processes may be beneficial in preventing regret from becoming a severe psychological load to bear. In conclusion, the study’s findings offer insight on preventive treatments that might be applied to improve university students’ mental health. The academic atmosphere should be viewed as the natural setting for such actions.

Theoretical Implications

The study offers theoretical contributions in addition to practical ones. The paper offers empirical evidence on how intrinsic cognitive-emotional characteristics influence how distress, such as regret and resilience, predicts entrapment through mediation, building on the Vulnerability Stress Models (Ingram & Luxton, 2005). The simultaneous influence of resilience and regret suggests that distress works through both negative feelings (regret) and protective feelings (resilience), instead of directly leading to feeling trapped. According to the current study, people feel more confined when their distress feeds their regret. Consequently, regret is regarded as a cognitive-emotional process that can facilitate entrapment. In a similar vein, this framework’s framing of resilience as a protective element supports its theoretical function of lessening the psychological weight of distress. To capture emotional experiences and coping, this study adds regret and resilience as mediators to the current vulnerability stress models. A multifaceted perspective on the interplay of emotions, cognitive processes, and vulnerabilities in the face of distress is presented in the current research.

Data availability

The anonymized dataset generated and analyzed in this study was directly collected from university students through psychological assessment questionnaires. As the dataset includes ethically sensitive information, it has been anonymized to protect participant confidentiality and is currently shared for review purposes only. The dataset can be accessed at the following link: Data set.

References

Akaike H (1987) Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 52(3):317–332

Aktu Y (2023) The adaptation of the regret elements scale to Turkish culture. Turkish Psychological Counseling Guidance J 13(70):372–387

Altun Y, Özen M, Kuloğlu MM (2019) Psikolojik Sıkıntı Ölçeğinin Türkçe uyarlaması: Geçerlilik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Anatol J Psychiatry/Anadolu Psikiyatr Derg 20:23–31

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Psychological Distress. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved April 5, 2024. https://dictionary.apa.org/psychological-distress

Atkinson, BJ (2015). Relationships and the neurobiology of resilience. Couple Resilience: Emerging Perspectives, 107-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9909-6_6

Bacchi S, Licinio J (2017) Resilience and psychological distress in psychology and medical students. Academic Psychiatry 41:185–188

Brown SJ, Goetzmann WN, Ross SA (1995) Survival. J Financ 50(3):853–873

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Ed 154:136–136

Buchanan J, Summerville A, Lehmann J, Reb J (2016) The regret elements scale: distinguishing the affective and cognitive components of regret. Judgm Decis Mak 11(3):275–286

Chabbouh, A, Charro, E, Al Tekle, GA, Soufia, M, Hallit, S (2024). Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the short entrapment scale in a non-clinical sample of young adults. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 37(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-024-00286-2

Cheon SH (2012) Relationships among daily hassles, social support, entrapment and mental health status by gender in university students. Korean J Women Health Nurs 18(3):223–235

Connor KM, Davidson JR (2003) Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC). Depression Anxiety 18(2):76–82

Cramer RJ, Rasmussen S, Tucker RP (2019) An examination of the entrapment scale: factor structure, correlates, and implications for suicide prevention. Psychiatry Res 282:112550

De Beurs D, Cleare S, Wetherall K, Eschle-Byrne S, Ferguson E, O’Connor DB, O’Connor RC (2020) Entrapment and suicide risk: the development of the 4-item entrapment scale short-form (E-SF). Psychiatry Res 284:112765

Dixon AK (1998) Ethological strategies for defence in animals and humans: their role in some psychiatric disorders. Br J Med Psychol 71(4):417–445

Doğan T (2015) Kısa psikolojik sağlamlık ölçeği’nin Türkçe uyarlaması: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. J Happiness Well-Being 3(1):93–102

Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prévost D (2012) Epidemiology of psychological distress. Mental Illnesses-Understanding. Prediction Control 69(2):105–106

Earvolino‐Ramirez M (2007) Resilience: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum 42(2):73–82

Ermiş EN, Bayraktar S (2021) Adaptation of multidimensional existential regret inventory to Turkish: reliability and validity analysis. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar 13:421–440

Eskin M, Sun JM, Abuidhail J, Yoshimasu K, Kujan O, Janghorbani M, Flood C, Carta MG, Tran US, Mechri A, Hamdan M, Poyrazlı S, Aidoudi K, Bakhshi S, Harlak H, Moro MF, Nawafleh H, Phillips L, Shaheen A, Taifour S, Tsuno K, Voracek M (2016) Suicidal behavior and psychological distress in university students: a 12-nation study. Arch Suicide Res 20(3):369–388

Finney, SJ, DiStefano, C (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 269-314

Gilbert P (2001) Evolutionary approaches to psychopathology: the role of natural defences. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry 35(1):17–27

Gilbert P, Allan S (1998) The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychological Med 28(3):585–598

Gilbert P, Gilbert J (2003) Entrapment and arrested fight and flight in depression: an exploration using focus groups. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract 76(2):173–188

Green BL (1990) Defining trauma: terminology and generic stressor dimensions 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 20(20):1632–1642

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55

Ingram RE, Luxton DD (2005) Vulnerability-stress models. Dev psychopathology: a vulnerability-stress Perspect 46(2):32–46

Johnson J, Panagioti M, Bass J, Ramsey L, Harrison R (2017) Resilience to emotional distress in response to failure, error or mistakes: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 52:19–42

Joseph S, Linley PA (2006) Growth following adversity: theoretical perspectives and implications for clinical practice. Clin Psychol Rev 26(8):1041–1053

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32(6):959–976

Kiziela A, Viliūnienė R, Friborg O, Navickas A (2019) Distress and resilience associated with workload of medical students. J Ment Health 28(3):319–323

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press, New York

Kraines MA, Krug CP, Wells TT (2017) Decision justification theory in depression: regret and self-blame. Cogn Ther Res 41:556–561

Landman J (1987) Regret: a theoretical and conceptual analysis. Joumal Theoty Soc Behauiour 7(2):135–160

Lowe, SR, Blachman-Forshay, J, Koenen, KC (2015). Trauma as a public health issue: Epidemiology of trauma and trauma-related disorders. Evidence Based Treatments For Trauma-Related Psychological Disorders: A Practical Guide For Clinicians, 11-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07109-1_2

Massé R (2000) Qualitative and quantitative analyses of psychological distress: methodological complementarity and ontological incommensurability. Qual Health Res 10(3):411–423

Masten AS (2001) Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol 56(3):227

Matud MP, Díaz A, Bethencourt JM, Ibáñez I (2020) Stress and psychological distress in emerging adulthood: a gender analysis. J Clin Med 9(9):2859

McGarry S, Girdler S, McDonald A, Valentine J, Lee SL, Blair E, Wood F, Elliott C (2013) Paediatric health‐care professionals: Relationships between psychological distress, resilience and coping skills. J Paediatrics Child Health 49(9):725–732

Mirowsky, J, Ross, CE (2002). Measurement for a human science. J Health Soc Behav 152−170. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090194

Nasser-Abu Alhija F, Wisenbaker J (2006) A Monte Carlo study investigating the impact of item parceling strategies on parameter estimates and their standard errors in CFA. Struct Equ Modeling 13(2):204–228

O’Connor RC, Portzky G (2018) Looking to the future: a synthesis of new developments and challenges in suicide research and prevention. Front Psychol 9:391532

Pakalniškienė V, Viliūnienė R, Hilbig J (2016) Patients’ resilience and distress over time: is resilience a prognostic indicator of treatment? Compr Psychiatry 69:88–99

Perdomo, N (2021). Mortality salience and moral dilemmas: The impact of stress on regret in trolley problem decision-making. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Fort Hays State University. https://doi.org/10.58809/IURD7282

Pieters R, Zeelenberg M (2007) A theory of regret regulation 1.1. J Consum Psychol 17(1):29–35

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comp 36:717–731

Roese NJ, Summerville A (2005) What we regret most… and why. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 31(9):1273–1285

Roese NJ, Epstude KAI, Fessel F, Morrison M, Smallman R, Summerville A, Galinski AD, Segerstrom S (2009) Repetitive regret, depression, and anxiety: findings from a nationally representative survey. J Soc Clin Psychol 28(6):671–688

Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han MH, Charney DS, Nestler EJ (2012) Neurobiology of resilience. Nat Neurosci 15(11):1475–1484

Selye, H (1974). Stress without distress. In Psychopathology of Human Adaptation (pp. 137-146). Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2238-2_9

Siddaway AP, Taylor PJ, Wood AM, Schulz J (2015) A meta-analysis of perceptions of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety problems, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality. J Affect Disord 184:149–159

Singh, K, Junnarkar, M, Kaur, J (2016). Measures of positive psychology. Development and Validation. Berlin: Springer

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J (2008) The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 15:194–200

Tabachnick, BG, Fidell, LS (2001) Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education

Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ, Jeevanba SB (2020) Factors associated with emotional distress and suicide ideation among international college students. J Am Coll Health 68(6):565–569

Türk N, Yasdiman MB, Kaya A (2024) Defeat, entrapment and suicidal ideation in a Turkish community sample of young adults: an examination of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional (IMV) model of suicidal behaviour. International Review of Psychiatry, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2024.2319288

Winefield HR, Gill TK, Taylor AW, Pilkington RM (2012) Psychological well-being and psychological distress: is it necessary to measure both? Psychol Well-Being Theory, Res Pract 2:1–14

Zhang D, Tian Y, Wang R, Wang L, Wang P, Su Y (2022) Effectiveness of a resilience-targeted intervention based on “I have, I am, I can” strategy on nursing home older adults’ suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 308:172–180

Zou G, Shen X, Tian X, Liu C, Li G, Kong L, Li P (2016) Correlates of psychological distress, burnout, and resilience among Chinese female nurses. Ind Health 54(5):389–395

Acknowledgements

This research has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol has been approved by the Yıldız Technical University Scientific Research and Ethical Review Board (Address: ‘etik.yildiz.edu.tr/dogrula’ Report No: 20240402854 Verification Code: 9f93a). Furthermore, this research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards declared in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent updates.

Informed Consent

All participants voluntarily participated in the study and provided informed consent. Respondents in this investigation were university students. On April 25, 2024, informed consent was obtained after it was clarified that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Prior to completing the questionnaire, they were informed of the purpose, scope, and potential risks of the study. The use of all personal information was exclusively for academic research and was maintained in strict confidentiality.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akyıl, Y., Çağlar, A. & Erdinç, B. The mediating role of resilience and regret between psychological distress and entrapment: parallel mediation model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06102-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06102-1