Abstract

The current study explored the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and protective behaviors among Saudi secondary school students. It further examines the mediating role of cyber threat perception and the moderating effect of internet usage duration. The research was conducted in 2024 on a diverse sample of 1980 secondary school students using a multi-stage sampling method and a multi-center approach across various regions. The research instruments were meticulously designed and validated to align with the cultural context of Saudi. To analyze the data, the study employed confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling using AMOS24 software. Both cybersecurity awareness (β = 0.38, p < 0.001) and internet usage duration (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) positively predicted students’ cyber threat perception, which in turn significantly predicted their data protection behaviors (β = 0.44, p < 0.001). Cyber threat perception mediated the link between cybersecurity awareness and protective behaviors (indirect β = 0.17, p < 0.001), and internet usage duration strengthened both the direct and indirect effects—students with higher daily online time showed a stronger translation of awareness into threat perception and protective action. Accordingly, integrating interactive cybersecurity modules (such as threat simulations and hands-on exercises) within secondary-school programs boosts students’ understanding of threats and leads to improved protective behaviors in their everyday lives. Allocating resources to students with high internet exposure through intensive workshops and parental-teacher partnerships will optimize program impact, as these students derive the most benefit from enhanced awareness and practical training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the increasing threats worldwide, cybersecurity is among the most vital features in any field, including education. The arrival of the Information age and more particularly the development of the Internet has radically affected education and learning (Consoli et al., 2023; y Otaif, 2023). Because schools to prepare students to live in the digital world it is necessary that schools educate the students on how they can effectively deal with the effects of cybercrimes (Samala et al., 2024). This importance is even more apparent in the fast-digitalizing nations like Saudi (Salem et al., 2024).

Like in other fields, cybersecurity is about guarding users’ data and information and increasing people’s awareness about safe/unsafe behaviors and threats (Bada et al., 2019; Zwilling et al., 2022). Previous paradigms of cybersecurity in education reveal that prior initiatives centered more on engineering security systems. However, as specific types of attacks that exploit the lack of knowledge started to appear, the need for more extensive education became obvious (Bandara et al., 2014; Li et al., 2019). Around the world, developed nations have established elaborate programs that are used to educate students on cybersecurity. For instance, students in the United States and Australia have used interactive training programs and simulating cyber-attacks to develop the skills required to detect threats (Bada & Nurse, 2019; Hart et al., 2020; Yigit et al., 2024). Though Saudi, a developing country, is trying to advance in this field by applying strategies like Vision 2030, there are still many deficiencies. The shortage of qualified teachers and the inaccessibility of systematic educational solutions are among the reasons to be discussed (Alsulami et al., 2021; Alzubaidi, 2021).

Cybersecurity is not limited to technical factors; psychological and cultural dimensions also play a significant role. Research shows that users’ perceptions of cyber threats and attitudes toward safe behaviors significantly influence their decision-making (Guerrero, 2024; Singh & Cheema, 2024). For example, in collectivist cultures such as Saudi, social support and the role of parents and teachers can reinforce safe behaviors (Hofstede, 1984). Specifically, in Saudi, with the increasing use of the Internet in schools and modernization initiatives like Vision 2030, there is a pressing need for comprehensive policies to enhance cybersecurity awareness. However, many efforts have focused on improving access to technology, while less attention has been given to cybersecurity awareness (Albaqami et al., 2024; Bunaiyan, 2019).

On the other hand, cybersecurity breaches in schools can have serious economic and social consequences. Economic costs include the loss of sensitive data, rebuilding damaged technology systems, and expenses related to remedial training (Ulven & Wangen, 2021). From a social perspective, these breaches can lead to a decrease in public trust in the education system, disruption of the learning process, and harm to students’ psychological well-being (Catota et al., 2019). These costs can have more severe negative impacts in developing countries like Saudi, where efforts are ongoing to integrate technology into education. Therefore, understanding the factors influencing data protection behaviors can be a crucial step toward enhancing cybersecurity. This study investigates the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and protective behaviors among secondary school students in Saudi. Additionally, it will investigate the mediating role of cyber threat perception and the moderating role of internet usage duration. The findings of this study can help policymakers design more effective educational programs and enhance cybersecurity in educational environments.

Current study

This is the first large‑scale study among Saudi secondary school students to simultaneously examine (a) the mediating role of cyber threat perception in the link between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors, and (b) the moderating effect of internet usage duration on both direct and indirect pathways. By integrating these psychological and usage-based mechanisms within a single structural equation modeling (SEM) framework, this study provides novel insights for tailoring culturally sensitive, exposure-driven cybersecurity education programs in rapidly digitalizing contexts, such as Saudi. Accordingly, the hypotheses of this study were:

-

A positive relationship between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behaviors.

-

Cyber threat perception mediates the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors.

-

Internet usage duration moderates the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors.

Literature review and concepts

Study concept

Due to its centralized structure and management by the Ministry of Education, the Saudi education system holds significant potential for implementing national policies such as Vision 2030 (Alaklabi, 2024). This initiative, aimed at modernizing educational infrastructure and developing digital skills, provides a unique opportunity to expand cybersecurity awareness (Bunaiyan, 2019). However, evaluations indicate that the lack of comprehensive programs and insufficient coordination between policymakers and school administrators have posed significant barriers to the effective implementation of cybersecurity policies (Almomani et al., 2021). Studies have shown that existing programs are often fragmented and designed without considering the specific needs of schools (Alzubaidi, 2021; Srivastava, 2024). For example, initiatives such as “Cyber Awareness for All,” aimed at increasing cybersecurity awareness among students, have shown limited effectiveness due to a shortage of specialized teachers and insufficient educational resources (Alzubaidi, 2021).

This gap is more pronounced in regions with limited access to advanced technologies and educational resources, increasing students’ vulnerability to cyber threats (Alsulami et al., 2021). One of the main obstacles to implementing cybersecurity policies is the misalignment between educational programs and Saudi society’s cultural and social needs (Alarifi et al., 2012; Saleh, 2024). While offering opportunities to promote group-safe behaviors, Saudi collectivist culture can become a barrier to fostering independent attitudes and individual skills in addressing cyber threats without structured education (Hofstede, 1984). Furthermore, current approaches often focus on teaching theoretical cybersecurity concepts, while less emphasis is placed on practical skills, such as cyber threat simulations and protective tools. This approach reduces the effectiveness of programs, particularly for younger age groups who require more practical and interactive training methods (Bada & Nurse, 2019).

In Gulf countries, such as the United Arab Emirates, cybersecurity programs that focus on practical training and advanced technologies have yielded significant results. For example, utilizing cyber-attack simulations and specialized training courses for teachers has effectively increased students’ awareness of cyber threats (Aldarmaki, 2018). In comparison, Saudi is still in the early stages of developing such programs and requires further investment in teacher training, the development of appropriate educational content, and the establishment of technological infrastructure in schools. Additionally, experiences from developed countries show that fostering partnerships between the private sector and the government can help secure necessary resources and enhance the effectiveness of educational programs (Zwilling et al., 2022).

As the widespread adoption of digital technologies and the online presence of students have created opportunities for more effective educational programs (Al‐Ghaith et al., 2010; Alshehri et al., 2012), innovative technologies such as cyber-attack simulations, interactive educational applications, and AI-based platforms have proven to be practical tools for teaching cybersecurity concepts in Saudi schools (Khan, 2024). To overcome these challenges, Saudi education system requires more comprehensive approaches, including infrastructure development, specialized teacher training, and fostering a culture of cybersecurity through coordinated educational programs and policy initiatives (Mishra & Hanna, 2023). Additionally, addressing the specific needs of schools in underprivileged areas and enhancing collaboration between government institutions and the private sector are essential steps toward improving the current situation (Alghamdi, 2022).

Cybersecurity awareness

According to Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (1986), humans acquire behaviors through social interactions that involve personal factors and environmental influences, which reciprocally affect behavioral patterns. The framework of this theory hinges on observational learning or modeling, where people learn new abilities and knowledge by observing others and absorbing the results of their behaviors. Through observing instructors and peers successfully deal with phishing threats or adjust privacy settings, cyber students construct cognitive patterns for recognizing and responding to digital threats. Participating in hands-on lab exercises that simulate malware detection develops students’ self-efficacy, which Bandura describes as the strongest indicator of knowledge application to practical tasks(Bandura, 1986). Embedding modeling and guided practice into cybersecurity education enables educators to utilize vicarious learning and self-regulatory feedback to strengthen understanding of safe online behavior principles and methods.

Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (1991) further elucidates the pathway from awareness to action by delineating three proximal determinants of behavioral intention: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Protective behaviors in cybersecurity receive positive evaluation when viewed as beneficial by learners who use strong passwords as an example while perceived social pressure from peers and educators defines subjective norms and perceived control reflects self-assurance in performing secure behaviors in varying circumstances. Empirical studies have corroborated this framework (Ajzen, 1991). The study by Ifinedo (2012) showed that employees planned to follow information security policies based on their attitudes and perceived behavioral control while Pahnila et al. (2007) showed that end-user adherence to security guidelines grew when users felt they possessed necessary skills and organizational backing (Ifinedo, 2012; Pahnila et al., 2007).

For instance, students with a positive attitude toward using complex passwords and receiving social support for this behavior are more likely to adopt this practice in their daily routines (Ng et al., 2009; Siponen et al., 2014). This relationship between awareness, attitude, and behavior highlights the need for educational programs that help reinforce these three factors. Incorporating active learning into educational programs can strengthen users’ attitudes and motivation to engage in safe behaviors (Furnell & Clarke, 2012; Ifinedo, 2014).

Cyber threat perception

The Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers, 1975) focuses on how individuals respond to threats. This model posits that the perception of Threat Severity and threat vulnerability, as well as the evaluation of Coping Efficacy, are key drivers of protective behaviors (Rogers, 1975). In this context, if students perceive cyber threats as serious and believe that available tools, such as antivirus software or software updates, are practical, they are more likely to engage in safer behaviors (Workman et al., 2008). The model also suggests that a lack of accurate threat perception can lead to a failure to perform protective behaviors, even if awareness exists. For example, students who do not perceive threats as serious are likelier to share personal information without considering the risks (Hadlington, 2017; Ng et al., 2009). Therefore, educational programs should focus on strengthening the perception of cyber threats. Studies have shown that threat perception is influenced by cultural and social factors (Hallinger & Kantamara, 2001; Hofstede, 1984). In the cultural context of Saudi, collectivist values enhance threat perception and encourage users to take collective and preventive actions. For example, students who perceive cyber threats as serious and believe that protective tools, such as complex passwords or antivirus software, are practical are more likely to adopt safer behaviors (Ng et al., 2009).

Data protection behavior

The habit theory emphasizes that protective behaviors become effectively ingrained in users’ daily lives when they are formed into habits. For example, if students regularly change their passwords or avoid unknown links, these behaviors will be consistently performed (Verplanken & Orbell, 2003). Deci and Ryan’s (2013) theory of autonomy also emphasizes the importance of a sense of competence and independence in engaging in protective behaviors. This theory suggests that users are more motivated to engage in secure behaviors when they feel they can perform them independently and effectively. Therefore, designing educational programs that reinforce this sense of competence in students is crucial (Deci & Ryan, 2013). Adding experiential-based educational programs can help students turn protective behaviors into habits through continuous practice (Kolb et al., 2014).

Internet usage duration

The media dependency theory (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976) explains how prolonged use of technology can be both an opportunity for learning and a source of vulnerability (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). Users with more experience in the online space may develop better skills in identifying cyber threats, but they may also be exposed to more significant risks due to increased exposure. Education and planning can enhance users’ awareness and protective behaviors when accompanied by education and planning (Zwilling et al., 2022).

Cultural context of Saudi

Hofstede’s cultural values theory identifies collectivist cultural traits as a significant factor in protective behaviors (Hofstede, 1984; Kolb et al., 2014). In collectivist cultures like Saudi, group cooperation and prioritizing collective interests play a central role in shaping behaviors. These traits can be reinforced through group programs in schools or through the involvement of parents and teachers in cybersecurity education. Studies have shown that students participating in group activities are more likely to follow safe norms (Moulin-Stożek et al., 2018; Nasution et al., 2024).

The foundational religious and moral values in Saudi society have a significant influence on student perspectives and daily actions in both physical and online spaces. education in Saudi upholds Islamic values such as trustworthiness, respect for others’ rights, and Godly accountability, which shape digital etiquette practices and responsible information sharing norms. Students who approach online interactions using these moral principles will internalize safe-use norms as part of their ethical responsibilities. Saudi schools utilize moral education derived from Qur’anic studies and character-building programs to reinforce these values, which serve as the normative standard for assessing cybersecurity behaviors.

Collectivist societies use group cooperation to strengthen their foundational moral principles. Students gain experience in negotiating shared responsibilities while building mutual trust and adhering to collective conduct standards during collaborative classroom projects. During their active supervision of group activities, parents and teachers teach technical knowledge while establishing stronger social norms that prevent risky online behaviors. This relational scaffolding transforms safe cyber habits from individual decisions into established community standards.

The significance of values and norms in cybersecurity education remains underexplored because current research primarily comes from Western and secular settings, which neglects how these elements function within Saudi educational institutions. This study provides a culturally grounded framework to foster cyber resilience by examining the interplay between religious-moral teachings, cooperative learning structures, and parental-teacher engagement. Integrating cybersecurity education into moral training programs alongside family–school partnerships may lead to greater improvements in threat awareness and defensive actions compared to traditional technical training methods. These findings provide guidance for developing interventions tailored to Saudi students’ cultural values, including faith-based digital literacy workshops and community-driven “safe‑surfing” pledges.

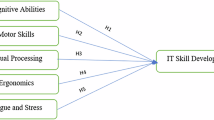

Conceptual model of the research

Based on the theoretical framework and findings of previous studies, the conceptual model of the research was outlined (Fig. 1).

Method

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted in April–May 2024 and employed a stratified, multi-stage sampling design to ensure a representative cross-section of Saudi secondary school population.

Participants and procedures

First, the country was stratified into its five major regions—Central, Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern (according to the Ministry of Education’s boundaries). Within each area, The author obtained official lists of all public and private secondary schools. Simple random sampling was applied to select ten schools per region, balancing five public and five private institutions while reflecting each region’s urban–rural distribution. From each chosen school, two classes were then randomly selected—one comprising students in Grades 10–11 and the other in Grade 12—to capture the full adolescent age range of 16–18 years and to minimize clustering effects within schools.

The study enrolled 1980 students from multiple secondary schools across Saudi who were chosen through a multi-stage sampling approach. Researcher implemented procedures to maintain diversity across urban and rural school selections, ensuring proper representation. Students had to meet three conditions to be included in the research: they needed to attend secondary school and use internet-based educational tools, and their parents agreed to let them join the study. The selection method produced samples that accurately represented the study’s target population. The study was conducted in 2024.

Measures

Measures development

I employed a rigorous, multi-phase procedure based on best practices for scale development to create and validate three novel instruments: the Cybersecurity Awareness Scale, the Cyber Threat Perception Scale, and the Data Protection Behavior Scale. In the initial phase, an exhaustive systematic literature review was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, employing a broad array of keyword combinations to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant constructs. Search terms included “cybersecurity awareness,” “cyber threat perception,” “data protection behavior,” “online safety,” “digital literacy,” “information security education,” “risk perception,” “scale development,” “psychometric evaluation,” “instrument validation,” “adolescent cybersecurity,” “protective behavior,” and “security countermeasures”. These keywords guided the assembly of a detailed handbook of theoretical models, empirical findings, and existing measurement approaches, which in turn informed the drafting of the initial item pools.

All significant articles, reports, and guidelines were documented in an extensive handbook that established both theoretical and empirical foundations for creating measurement items. Based on the detailed handbook, initial sets of 16, 21, and 19 items were developed for awareness, threat perception, and data protection behavior, respectively. An expert panel, including a licensed psychologist (PhD), a biostatistician (PhD), and a cybersecurity and data protection specialist, was formed to evaluate the item pool. During both solo evaluations and combined sessions, panelists reviewed each question for its clarity, relevance, and representation of the conceptual target, while also providing suggestions for new items to fill identified gaps. The wording was refined and redundant items were removed through repeated discussions between experts and the author, while areas requiring greater depth were expanded, resulting in the first-draft forms (Form I) of each scale. The expert group used a 4-point scale to determine the perceived importance of each item, thereby establishing face validity. All items with scores under 1.5 were eliminated, but items scoring above 1.5 remained on the list or underwent revisions for improved accuracy. The item reduction process yielded 13 items for cybersecurity awareness measurement, 16 items for threat perception assessment, and 14 items for evaluating data protection behavior (Form II). During the next stage of content validation, qualitative expert feedback was integrated with quantitative indices. Each item was evaluated by experts for relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness, which informed minor modifications to the wording. The CVI was computed for all scale items, retaining those with CVIs ≥ 0.79 while revising others, and the CVR was determined using Lawshe’s (1975) method to discard or edit items with CVR scores below 0.62 for the ten-member panel. The final versions of the survey included 11 items related to cybersecurity awareness, alongside 13 items for threat perception and another 11 items targeting data protection behavior.

The pre‑final scales were tested through a pilot study involving 50 secondary school students to evaluate readability and interpretability, while response patterns were examined. Participants’ input regarding unclear wording and response fatigue led to minor adjustments in the phrasing and sequence of items. Participants completed each scale consisting of closed‑ended statements rated on a 5‑point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) after receiving a clear explanation of the study’s purpose. This following section demonstrates the psychometric evaluation of these instruments through analysis of their factor structure along with their reliability and construct validity.

Cybersecurity awareness scale

The goal is to assess students’ awareness of cybersecurity concepts and principles, including awareness of threats, protective tools, and preventive measures. This scale consists of 11 items that evaluate students’ behaviors related to cybersecurity. Items such as “I know that sending sensitive information over the internet without encryption could lead to a breach of my personal information” and “If the software asks for access to my personal information, I will check whether this request is necessary before accepting it” are included. The reliability of this scale was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85. The unidimensional model with 11 items for the Cybersecurity Awareness scale was examined. The fit indices indicate that the unidimensional model for this scale is confirmed: [χ²/df = 2.89; RMSEA = 0.04 (0.03–0.05); CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.01; IFI = 0.97; PCFI = 0.63; GFI = 0.98; PNFI = 0.63]. Also, the factor loadings of all items were above 0.5 and significant at the 0.001 level. Also, the factor loadings of the items were between 0.534 and 0.922. Table S1 presented the full item descriptions of the cybersecurity awareness scale.

Cyber threat perception scale

The Cyber Threat Perception Scale was developed to assess how students perceive the seriousness and likelihood of encountering cyber threats while using the internet. After applying the detailed content validation processes, the final tool comprises 13 self-reported items. Representative items include: I will neither enter my personal information nor click on any suspicious links that claim I have won a prize. The scale achieved excellent internal consistency reliability, as demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, indicating that all items effectively measure one underlying construct. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the single-factor model. The 13‑item, one‐factor model demonstrated acceptable to good fit across multiple indices: The model fit statistics show χ²/df = 3.01; RMSEA was found to be 0.06 with a 90% confidence interval of [0.05, 0.07]; CFI and IFI both scored 0.94; SRMR came in at 0.03; GFI reached 0.96; PCFI was 0.58; and PNFI also registered 0.58. The results validate that the scale operates as a unified single-dimensional tool to measure cyber threat perception among Saudi secondary school students. Also, the factor loadings of all items were above 0.5 and significant at the 0.001 level. Also, the factor loadings of the items were between 0.576 and 0.833. Table S2 presented the full items description of the cyber threat scale.

Data protection behavior scale

The Data Protection Behavior Scale was designed to capture the frequency and consistency of students’ self‑reported actions aimed at safeguarding personal data in online environments. Following the item development and validation procedures outlined previously, the final version comprises 11 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Sample items include “Every time I use a website, I log out of my account after finishing to ensure its security,” and “I regularly check my mobile operating system and software for the latest updates. The internal consistency of the scale was outstanding, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91, indicating high homogeneity among items. A single‑factor structure was tested using confirmatory factor analysis. The 11‑item unidimensional model demonstrated an acceptable to good fit: χ²/df = 3.47; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07 (90% CI [0.06, 0.08]); Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.92; Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.92; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.04; Goodness‑of‑Fit Index (GFI) = 0.94; Parsimony‑Corrected CFI (PCFI) = 0.53; and Parsimony‑Normed Fit Index (PNFI) = 0.53. These indices collectively support the Data Protection Behavior Scale as a reliable and valid unidimensional measure of protective behaviors among Saudi secondary school students. Also, the factor loadings of all items were above 0.4 and significant at the 0.001 level. Also, the factor loadings of the items were between 0.451 and 0.810. Table S3 presented the full items description of the data protection behavior scale.

Demographic information form

A survey was designed to collect demographic information, including the students’ gender, educational level, and daily internet usage duration. It included questions on students’ gender (male or female), current high school grade level (first year, second year, or third year), and their average daily Internet usage duration, reported in minutes.

Analytical strategy

This study employed path analysis with the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method using AMOS 24 software to examine the mediating and moderating model. Additionally, univariate normality assumptions were tested based on skewness and kurtosis indices, and multivariate normality was assessed based on the Mardia coefficient. Given that the skewness and kurtosis values for the study variables were within the range of [−2, 2] and the critical ratio of the Mardia coefficient was <5, the univariate and multivariate normality assumptions were confirmed (Kline, 2023).

The model fit was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.9, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) > 0.9, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) > 0.9, Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index (PCFI) > 0.5, Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PNFI) > 0.5, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08.

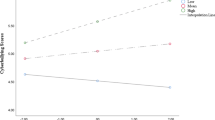

The study examined the moderating effect of continuous internet usage duration by creating an interaction term through the multiplication of mean-centered cybersecurity awareness and mean-centered daily internet usage hours. The latent interaction was incorporated into the SEM analysis in AMOS by applying an unconstrained product-indicator approach, in accordance with Klein and Moosbrugger’s (2000) procedure. The model incorporating the interaction term demonstrated a significantly improved data fit over the baseline model without moderation, as indicated by the statistical results (Δ χ² (1) = 7.85, p = 0.005; ΔCFI = 0.012; ΔRMSEA = 0.005). The simple‐slope plots at −1 SD (low usage) and +1 SD (high usage) illustrated that students who used the internet more frequently exhibited a stronger positive relationship between cybersecurity awareness and protective behaviors.

Ethical compliance

This research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the College of Education, Umm Al-Qura University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in compliance with relevant ethical guidelines for research involving human participants, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted under the protocol number 2401120492 for the project titled [The Relationship Between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behaviors Among Saudi Secondary School Students: The Mediating Role of Cyber Threat Perception and the Moderating Role of Internet Usage Duration], with an approval date of January 2024. The study was approved on the condition that it adhered strictly to the submitted protocol, with any amendments requiring prior approval. All participants provided informed consent, and parental consent was secured for minors before data collection.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation

In this study, 1980 high school students from Saudi were surveyed. Of these, 1075 students (54.3%) were female, and 905 students (45.7%) were male. Additionally, 570 students (28.8%) were in their first year of high school, 865 students (43.7%) were in their second year, and 545 students (27.5%) were in their third year. The average daily internet usage among the students was 203.90 ± 107.36 min, with a range from 5 to 599 min (Table 1). The results of the Pearson correlation test revealed a positive and significant relationship between the research variables (p < 0.001).

Evaluation of the proposed model

The fit indices of the proposed research model indicate that the proposed model is confirmed: [χ² (8) = 37.5, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.01; RMSEA = 0.043, 90% CI [0.031, 0.058]; PNFI = 0.61; PCFI = 0.62; IFI = 0.97; GFI = 0.95]. Figure 2 shows the standardized coefficients of the proposed research model.

Direct paths

Table 2 demonstrated that Cybersecurity Awareness (β = 0.38, P < 0.001) and Internet Usage Duration (β = 0.27, P < 0.001) produce a positive and significant impact on Cyber Threat Perception. A positive and significant impact on Data Protection Behavior was demonstrated by Cybersecurity Awareness (β = 0.23, P < 0.001), Internet Usage Duration (β = 0.30, P < 0.001), and Cyber Threat Perception (β = 0.44, P < 0.001). Internet Usage Duration proved to be a significant moderator between Cybersecurity Awareness and Cyber Threat Perception, according to the statistical results, β = 0.16 and P = 0.009. The association between Cybersecurity Awareness and Cyber Threat Perception demonstrates variable slopes when comparing students with different internet usage levels as depicted in Fig. 3. The correlation between these two variables demonstrates greater strength for students who frequently use the internet (β = 0.49, P < 0.001) than for those who use it less often (β = 0.12, P = 0.089), as shown in Fig. 3.

The duration of internet use significantly moderated the relationship between cyber threat perception and data protection behavior (β = 0.21, p < 0.001). Figure 4 illustrates the variation in the relationship between Cyber Threat Perception and Data Protection Behavior among students with high internet usage and those with low internet usage. Students who use the internet more frequently exhibit a stronger relationship between these variables (β = 0.53, P < 0.001) than those who use the internet less frequently (β = 0.16, P = 0.039) as shown in Fig. 4.

Indirect effects and moderated mediated effects

The indirect effect of cybersecurity awareness on data protection behavior through cyber threat perception was significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.001). Therefore, the mediating role of Cyber Threat Perception in the relationship between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behavior is confirmed. Additionally, regarding the moderating role of Internet Usage Duration in the indirect relationship between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behavior, the results in Table 3 show that the indirect effect of Cybersecurity Awareness on Data Protection Behavior through Cyber Threat Perception was significant and more substantial for students with a high level of internet usage (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) compared to students with a low level of internet usage (β = 0.02, p = 0.311).

The results of pairwise comparisons of the indirect effect of Cybersecurity Awareness on Data Protection Behavior at three levels of Internet Usage Duration (one standard deviation below the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean) show a significant difference in the indirect effect between students with high internet usage ( + 1 SD) and those with low internet usage (−1 SD) and average usage. Additionally, there is a significant difference between the indirect effect in students with average and low internet usage, such that the mediating effect of Cyber Threat Perception in the relationship between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behavior becomes increasingly pronounced with higher levels of internet usage (Table 4).

Discussion

This section includes a discussion of the interpretation of the findings in light of previous studies, practical applications, policy implications, limitations of the study, suggestions for future research, and conclusion. The text is supported and developed with scientific references.

Research findings demonstrated that Cybersecurity Awareness positively influences Data Protection Behaviors in students, which underscores the critical role of cybersecurity education and awareness in strengthening digital security. The results match various longstanding scientific theories. The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) identifies positive attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control as the key factors that influence individual behaviors. Awareness of cybersecurity leads to positive attitudes that support safe online behaviors. Through practical training with threat simulations, students gain confidence in protective actions while parents and teachers provide essential support as normative influences who encourage protective behavior adoption.

Furthermore, according to the Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers, 1975), the severity and vulnerability of cyber threats play an important role in motivating protective behaviors. Students who understand the likelihood of encountering threats and their consequences are more motivated to follow safety principles. This finding is particularly reinforced when students are exposed to real-world simulations of cyber risks (Alzubaidi, 2021). Previous studies also support these findings. For example, Zwilling et al. (2022) demonstrated that more aware users are more likely to use protective tools, such as data encryption and antivirus software. Similarly, a study in Bahrain found that when cybersecurity awareness is reinforced simultaneously by parents and teachers, students are more likely to choose safe behaviors (Ayyash et al., 2024). Likewise, a study in Sweden emphasized that cyber threat simulations and practical exercises are key factors in enhancing the impact of awareness on protective behaviors (Jabali & Baher, 2024).

However, some studies have presented different results. For instance, research by Chandarman and Van Niekerk showed that even highly cybersecurity-aware users may exhibit unsafe behaviors. This issue could stem from overreliance on technology and a lack of practical training (Chandarman & Van Niekerk, 2017). Cultural values and social interactions shape protective behaviors in collectivist societies, such as Saudi. Parents and teachers, as key members of social norms, can reinforce students’ protective behaviors through modeling positive behaviors (Alnatheer, 2012). This aligns with the findings of Ayyash et al., which indicate that the involvement of parents and schools in collectivist environments plays a crucial role in enhancing cybersecurity awareness (Ayyash et al., 2024). In contrast, in individualist societies, such as Sweden, there is a greater emphasis on individual responsibility and the use of technological tools to enhance protective behaviors (Jabali & Baher, 2024). These differences suggest that cybersecurity education should be tailored to each society’s cultural and social context.

Moreover, this study demonstrated that cyber threat perception serves as a key mediator between cybersecurity awareness and students’ data protection behaviors. This finding is consistent with the Protection Motivation Theory. According to this theory, the perception of the severity and vulnerability of threats plays an important role in increasing the likelihood of adopting protective behaviors. This mediating role is significantly strengthened in educational environments that emphasize simulating cyberattacks and presenting real-life scenarios. Students exposed to simulated risks develop a better perception of real threats and are more motivated to follow protective measures. (Rogers, 1975) proposed this process as a practical framework for changing risky behaviors.

According to Social Cognitive Theory, threat perception is directly influenced by the interaction between knowledge, skills, and the social environment. Educational environments that incorporate simulations and practical exercises can foster effective interactions and enhance threat perception (Bandura, 1986). According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, threat perception can foster a positive attitude toward safe behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). In societies like Saudi, social norms and family interactions play a significant role in reinforcing this attitude. This aligns with findings from studies conducted in Saudi, which show that social interactions and organizational responsibility have a positive impact on users’ protective behaviors (Asfahani, 2024). This finding is also consistent with research conducted in Bahrain, which demonstrated that threat perception plays a crucial mediating role in translating cybersecurity awareness into safe behaviors (Ayyash et al., 2024). A study in Vietnam showed that the severity and vulnerability of perceived cyber threats act as key mediating factors in shaping protective behaviors. Users who perceive threats as serious are more likely to use protective tools (Tran et al., 2024). However, a study in Malaysia found that threat perception alone does not directly impact protective behaviors but can strengthen them when combined with other factors, such as fear of cyberattacks (Vafaei-Zadeh et al., 2024). Studies have shown that cybersecurity simulations can have a significant impact on enhancing threat perception and improving protective behaviors. For instance, a study in the UK found that users’ perception of cyber risks improves when they receive security information through real-life simulations (Van Schaik et al., 2017). Furthermore, research in Saudi has demonstrated that incorporating practical exercises into educational settings helps increase the sense of behavioral control and improves protective behaviors (Alzubaidi, 2021).

Finally, this study’s results revealed that internet usage duration can moderate the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors. According to the Internet Dependency Theory, prolonged use of online technologies can help users develop skills to interact with cyberspace, but this dependency may also lead to risky behaviors. This theory suggests that users increasingly rely on the Internet as a primary source for information, communication, and daily activities (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). The Internet Trust Theory emphasizes users’ trust in Internet security and that online tools can directly impact their behaviors. This theory explains that overtrust in technology, especially among users with limited cybersecurity awareness, may lead to a diminished perception of cyber threats (Chen & Zahedi, 2016; Moallem, 2024). In cases where users possess sufficient cybersecurity knowledge, trust in the internet can facilitate the increased use of protective tools like data encryption and security software. However, users with excessive trust in technology may neglect their protective actions and become overly reliant on online tools to safeguard their data (Moallem, 2024).

This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies, which suggest that frequent internet usage, when accompanied by structured training, can enhance safe behaviors. For example, the results of Dinev & Hu showed that prolonged use of internet technologies, when paired with sufficient cybersecurity knowledge, positively impacts users’ protective behaviors (Dinev & Hu, 2007). Similarly, Zwilling et al. confirmed that structured and prolonged internet use and educational programs can positively affect users’ protective behaviors. Their study showed that trained users are likelier to use protective tools like data encryption and security software (Zwilling et al., 2022). Van Schaik et al. also emphasized that cybersecurity simulations and exposure to real threats can enhance users’ risk perceptions and strengthen safe behaviors. Their study found that when exposed to practical training, long-term internet users are more inclined to adopt protective behaviors (Van Schaik et al., 2017).

On the other hand, the results of Chen & Zahedi’s study indicate that prolonged internet usage, if done without sufficient awareness, can lead to over-trust in technology. This trust may reduce users’ sensitivity to threats. However, combining continuous use with educational programs can mitigate these adverse effects and enhance users’ protective behaviors (Chen & Zahedi, 2016).

Finally, this research expands cybersecurity behavior studies beyond the existing Western-centric, adult-focused literature by emphasizing the unique sociocultural dynamics of Saudi youth. This study reveals how normative forces from family and institutional authorities influence secondary school students’ understanding of cyber threats and their protection responses within high-power-distance collectivist societies, highlighting complexities not captured by models from individualistic cultures. The research reveals that, within the Protection Motivation Theory framework, cyber threat perception acts as a mediator, indicating that threat assessment in Saudi exerts a distinct, consequential, and indirect influence. This suggests that mere awareness elevation is insufficient without additional interventions to increase perceived danger and susceptibility. The relationship between awareness and behavior becomes significantly stronger among heavy users when Internet usage duration is considered as a continuous variable, rather than being split into arbitrary categories, thus questioning the general applicability of current educational programs. These contributions enhance theoretical models of cybersecurity behavior while offering culturally specific guidance for educators and policymakers to develop more effective awareness campaigns in Saudi and similar high-context environments.

Theoretical implications

Results indicate that as students’ cybersecurity awareness increases along the scale from ‘somewhat aware’ to ‘very aware,’ their online threat perception rises by 0.4 standard units, shifting behavior from sporadic to consistent identification of phishing and malware scams. Every extra hour spent online per day raises threat perception by about 0.3 standard units resulting in more frequent users becoming more cautious when surfing the internet. Students with elevated threat perceptions adopt protective measures like software updates and strong passwords at rates nearly half a standard unit above those who perceive fewer dangers. The research indicates that providing hands-on training and resources to heavy internet users produces the greatest improvements in real-world data protection behaviors, as these users experience threats more acutely and translate that awareness into protective actions more effectively.

Policy implications

Integration of Cybersecurity Education into the Curriculum: Cybersecurity topics should be incorporated into the curriculum at all educational levels. The use of simulation tools and interactive modules can make this education more effective (AlMindeel & Martins, 2021).

Attention to Underserved Areas: The development of educational infrastructure and the provision of technological equipment for schools in underprivileged areas is essential (Alzubaidi, 2021).

Educational programs should incorporate the religious and ethical values of Saudi society. Combining these values with cybersecurity topics can increase the acceptance of these programs within the community (Aldarmaki, 2018).

Workshops for Parents: Parents can play a crucial role in reinforcing safe cybersecurity behaviors among their children (Odaibat & Eyadah, 2024).

Teacher Training: Organizing specialized courses for teachers turns them into key agents for implementing cybersecurity programs in schools (Alenezi & Alfaleh, 2024; Srivastava, 2024).

Game-Based Learning: Cybersecurity games can make learning security concepts more engaging and effective for students (Hart et al., 2020).

Continuous Monitoring: Developing continuous assessment systems to measure the effectiveness of educational programs and identify areas for improvement (MOUWERS-SINGH & MUSIKAVANHU, 2024).

Game-Based Learning: Cybersecurity games can make learning security concepts more engaging and effective for students (Hart et al., 2020).

Continuous Monitoring: Developing continuous assessment systems to measure the effectiveness of educational programs and identify weaknesses (MOUWERS-SINGH & MUSIKAVANHU, 2024).

Limitations and directions for future research

This study yielded meaningful and valuable results, but it also has certain limitations. The study’s sample population consisted solely of high school students from Saudi, which limits the ability to apply findings to other age categories and different global locations. Self-reported instruments maintain validity but tend to produce response bias when participants give socially desired answers. Future research should utilize additional data collection methods from varied sources, including observational data and feedback from teachers and parents. The research used data from Saudi exclusively so researchers should expand studies to various countries with different educational systems to enhance generalizability.

Despite the focus on secondary schools, future research is needed to determine whether the same mechanisms apply to both younger (primary) and older (tertiary) student groups. For younger students, a gamified approach may be required to instill basic cybersecurity habits. In comparison, older students may benefit from more advanced, discipline-specific modules (e.g., secure coding for computer science majors). Testing the mediated–moderated model across these settings will reveal how age, cognitive development, and curriculum demands influence awareness–behavior relationships and guide the design of stage-appropriate interventions.

Moreover, future studies should investigate how these mediated and moderated relationships vary across different demographic groups and cultural contexts. For instance, younger children may require gamified, play‑based approaches to establish foundational cybersecurity habits, while university students might benefit from advanced, discipline‑specific modules (e.g., secure coding for computer science majors). Comparative cross‑cultural research—examining both collectivist and individualist educational settings—would further clarify the boundary conditions of the model and inform the design of tailored interventions worldwide.

Conclusion

This study found that cybersecurity awareness and internet usage duration have a positive relationship with data protection behaviors among Saudi students. Cybersecurity awareness plays a key role in strengthening protective behaviors, and perceived cyber threats act as a mediating factor in this relationship. Additionally, internet usage duration serves as a moderating factor in the relationship between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors, especially for students with higher internet usage. These findings confirm the importance of cybersecurity education and awareness of threats in educational environments, emphasizing the need for comprehensive educational programs tailored to the cultural and social context. Ultimately, policymakers and educational administrators should design and implement effective educational programs and policies to enhance cybersecurity awareness and protective behaviors in schools, thereby preparing students to face cyber threats in the digital world.

Data availability

The corresponding author will provide the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current work upon reasonable request.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179−211

Al‐Ghaith W, Sanzogni L, Sandhu K (2010) Factors influencing the adoption and usage of online services in Saudi Arabia. Electron J Inf Syst Develop Ctries 40:1–32

Alaklabi M (2024) Decentralization Iimplementation in Saudi Arabian educational system: a qualitative study. University of the Incarnate Word

Alarifi A, Tootell H & Hyland P (2012) A study of information security awareness and practices in Saudi Arabia. 2012 international conference on communications and information technology (ICCIT). 2012 International Conference on Communications and Information Technology (ICCIT), Hammamet, Tunisia, 2012, pp. 6-12

Albaqami S, Nekovee, M & Khan I (2024) The future of IoT security in Saudi Arabian startups: a position paper. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 15(11)

Aldarmaki AR (2018) Customization of school-based cyber security awareness material for grade 12 Emirati students. https://khazna.ku.ac.ae/ws/portalfiles/portal/16922436/20182.pdf Accessed Dec 2018

Alenezi N & Alfaleh M (2024) Enhancing digital citizenship education in Saudi Arabian elementary schools: designing effective activities for curriculum integration. Front Edu https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1494487

Alghamdi AA (2022) Parents’ awareness of cybersecurity. J Eng Appl Sci 9(2):10−29

AlMindeel R, Martins JT (2021) Information security awareness in a developing country context: insights from the government sector in Saudi Arabia. Inf Technol People 34:770–788

Almomani I, Ahmed M, Maglaras L (2021) Cybersecurity maturity assessment framework for higher education institutions in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ Comput Sci 7:e703

Alnatheer MA (2012) Understanding and measuring information security culture in developing countries: case of Saudi Arabia. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/64070/ Accessed 5 Nov 2012

Alshehri M, Drew S & Alfarraj O (2012) A comprehensive analysis of e-government services adoption in saudi arabia: obstacles and challenges. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2012.030201

Alsulami MH, Alharbi FD, Almutairi HM, Almutairi BS, Alotaibi MM, Alanzi ME, Alotaibi KG, Alharthi SS (2021) Measuring awareness of social engineering in the educational sector in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Information 12:208

Alzubaidi A (2021) Measuring the level of cyber-security awareness for cybercrime in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 7:e06016

Asfahani AM (2024) Perceptions of organizational responsibility for cybersecurity in Saudi Arabia: a moderated mediation analysis. Int J Inf Secur 23:2515–2530

Ayyash M, Alsboui T, Alshaikh O, Inuwa-Dute I, Khan S & Parkinson S (2024) Cybersecurity Education and Awareness among Parents and Teachers: a survey of Bahrain. IEEE Access. pp. 86596−86617

Bada M, Nurse JR (2019) Developing cybersecurity education and awareness programmes for small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Inf Comput Security 27:393–410

Bada M, Sasse AM & Nurse JR (2019) Cyber security awareness campaigns: why do they fail to change behaviour? arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1901.02672

Ball-Rokeach SJ, DeFleur ML (1976) A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun Res 3:3–21

Bandara I, Ioras F & Maher K (2014) Cyber security concerns in e-learning education. ICERI2014 Proceedings, pp. 728−734

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs NJ 1986:2

Bunaiyan WA (2019) Preparing the Saudi educational system to serve the 2030 vision: a comparative analysis study. University of Denver

Catota FE, Morgan MG, Sicker DC (2019) Cybersecurity education in a developing nation: the Ecuadorian environment. J Cybersecur 5:tyz001

Chandarman R, Van Niekerk B (2017) Students’ cybersecurity awareness at a private tertiary educational institution. Afr J Inf Commun 20:133–155

Chen Y, Zahedi FM (2016) Individuals’ internet security perceptions and behaviors. Mis Q 40:205–222

Consoli A, Kovatcheva E, Catenazzi N, Gregori N & De Angelis K (2023) Cyber-security education as a key factor of the digital transformation for non-IT professionals. ICERI2023 Proceedings,

Deci EL & Ryan RM (2013) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior, 1st edn. Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 372

Dinev T, Hu Q (2007) The centrality of awareness in the formation of user behavioral intention toward protective information technologies. J Assoc Inf Syst 8:23

Furnell S, Clarke N (2012) Power to the people? The evolving recognition of human aspects of security. Comput Security 31:983–988

Guerrero VL (2024) Cyber threats, cyber risks, and cybersecurity responses: modeling whole-of-nation strategy implementation for American organizations and citizens. https://open.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/3721/ Accessed Aug 2024

Hadlington L (2017) Human factors in cybersecurity; examining the link between Internet addiction, impulsivity, attitudes towards cybersecurity, and risky cybersecurity behaviours. Heliyon 3(7) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00346

Hallinger P, Kantamara P (2001) Exploring the cultural context of school improvement in Thailand. Sch Effect Sch Improv 12:385–408

Hart S, Margheri A, Paci F, Sassone V (2020) Riskio: A serious game for cyber security awareness and education. Comput Security 95:101827

Hofstede G (1984) Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. sage, pp 327

Ifinedo P (2012) Understanding information systems security policy compliance: an integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput Security 31:83–95

Ifinedo P (2014) Information systems security policy compliance: an empirical study of the effects of socialisation, influence, and cognition. Inf Manag 51:69–79

Jabali A & Baher N (2024) Exploring the impact of cybersecurity knowledge and awareness on behavioral choices for protection among university students in Sweden. Inform Security Int J 34:7−22

Khan S (2024) Security and Privacy in Smart Cities Using Artificial Intelligence against Cyber Attacks. Appl Soft Comput 113:107859

Klein A, Moosbrugger H (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika 65:457–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338

Kline RB (2023) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications, pp 494

Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE & Mainemelis C (2014) Experiential learning theory: previous research and new directions. In: Sternberg RJ & Zhang L-F (eds.) Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, 1st edn. Routledge, pp. 286

Lawshe CH (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28:563–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

Li L, He W, Xu L, Ash I, Anwar M, Yuan X (2019) Investigating the impact of cybersecurity policy awareness on employees’ cybersecurity behavior. Int J Inf Manag 45:13–24

Mishra R, Hanna AH (2023) A systematic literature review on the cybersecurity gaps in Saudi curriculum that affect the banking sector. J Contemp Issues Bus Gov 29:468–490

Moallem A (2024) Human behavior in cybersecurity privacy and trust. In: Stephanidis C & Salvendy G (eds). Human-computer interaction in intelligent environments, 1st edn. CRC Press, pp. 466

Moulin-Stożek D, de Irala J, Beltramo C, Osorio A (2018) Relationships between religion, risk behaviors and prosociality among secondary school students in Peru and El Salvador. J Moral Educ 47:466–480

MOUWERS-SINGH C & MUSIKAVANHU TB (2024). A narrative review on enhancing cybersecurity in higher education institutions: the role of continuous training and awareness. Expert J Business Manag 12:67−73

Nasution A, Sumarni S, Lubis N (2024) The application of religious values in humanistic education in the elementary school curriculum: an ethnographic study. IJEGRA Int J Educ Glob Res Anal 1:27–37

Ng B-Y, Kankanhalli A, Xu YC (2009) Studying users’ computer security behavior: a health belief perspective. Decis Support Syst 46:815–825

Odaibat AA & Eyadah HTA (2024) A proposed conception of the role of the family in achieving digital security in light of achieving cybersecurity. life 7(10)

Pahnila S, Siponen M & Mahmood A (2007) Employees’ behavior towards IS security policy compliance. 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS'07), pp. 156b

Rogers RW (1975) A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 91:93–114

Saleh T (2024) Factors affecting cybersecurity awareness: a qualitative study in Saudi Arabia. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag 13: 751–762

Salem M, Samara K & Al-Tamimi A-K (2024) Navigating challenges in online cybersecurity education: insights from postgraduate students and prospects for a standardized framework. ACM Trans Comput Edu 24:1−32

Samala AD, Rawas S, Criollo-C S, Bojic L, Prasetya F, Ranuharja F, Marta R (2024) Emerging technologies for global education: a comprehensive exploration of trends, innovations, challenges, and future horizons. SN Comput Sci 5:1175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-03538-1

Singh B, Cheema SS (2024) Psychology in cybersecurity: unveiling the human dimensions of digital resilience. Int J Adv Netw Appl 16:6281–6290

Siponen M, Mahmood MA, Pahnila S (2014) Employees’ adherence to information security policies: an exploratory field study. Inf Manag 51:217–224

Srivastava AK (2024) Critical analysis of cybersecurity awareness programs in school education. Libr Prog Int 44:18282–18303

Tran DV, Nguyen PV, Vrontis D, Nguyen STN, & Dinh PU (2024) Unraveling influential factors shaping employee cybersecurity behaviors: an empirical investigation of public servants in Vietnam. J Asia Business Stud 18(6):1445–1464

Ulven JB, Wangen G (2021) A systematic review of cybersecurity risks in higher education. Future Int 13:39

Vafaei-Zadeh, A, Nikbin, D, Teoh, KY, & Hanifah, H (2024). Cybersecurity awareness and fear of cyberattacks among online banking users in Malaysia. https://www.emerald.com/insight/0265-2323.htm Accessed 30 Sept 2024

Van Schaik P, Jeske D, Onibokun J, Coventry L, Jansen J, Kusev P (2017) Risk perceptions of cyber-security and precautionary behaviour. Comput Hum Behav 75:547–559

Verplanken B, Orbell S (2003) Reflections on past behavior: a self‐report index of habit strength 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 33:1313–1330

Workman M, Bommer WH, Straub D (2008) Security lapses and the omission of information security measures: a threat control model and empirical test. Comput Hum Behav 24:2799–2816

Otaif MY (2023) Awareness of cybersecurity and its relationship to digital transformation among supervisors of the education department in Jazan region. Int J Res Educ 47:73–132

Yigit Y, Kioskli K, Bishop L, Chouliaras N, Maglaras L & Janicke H (2024) Enhancing cybersecurity training efficacy: a comprehensive analysis of gamified learning, behavioral strategies and digital twins. 2024 IEEE 25th International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM), Perth, Australia, pp. 24-32

Zwilling M, Klien G, Lesjak D, Wiechetek Ł, Cetin F, Basim HN (2022) Cyber security awareness, knowledge and behavior: A comparative study. J Comput Inf Syst 62:82–97

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. was responsible for all the writing of the article and data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the College of Education, Umm Al-Qura University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in compliance with relevant ethical guidelines for research involving human participants, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted under the protocol number 2401120492 for the project titled “The Relationship Between Cybersecurity Awareness and Data Protection Behaviors Among Saudi Secondary School Students: The Mediating Role of Cyber Threat Perception and the Moderating Role of Internet Usage Duration”, with an approval date of January 15, 2024. The study was approved on the condition that it adhered strictly to the submitted protocol, with any amendments requiring prior approval.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the survey period, which spanned from April 1, 2024, to May 30, 2024, using a survey questionnaire. Participants were fully informed of the purpose of the study, the scope of their participation, and how their data would be used, and they were assured that their anonymity and confidentiality would be maintained throughout the research process. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any repercussions. For vulnerable participants, consent was appropriately obtained from their legal guardians following a clear explanation of the research objectives and procedures. No incentives or payments were offered for participation. The study involved non-interventional research methods (surveys and questionnaires). Participants were explicitly made aware of the reasons for conducting the research, the intended use of the data, and the fact that there were no anticipated risks associated with their participation. All procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. As stated in the Methods section, data collection was conducted during April–May 2024, after receiving ethical approval in January 15, 2024.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alqarni, A. The relationship between cybersecurity awareness and data protection behaviors among Saudi secondary school students: the mediating role of cyber threat perception and the moderating role of internet usage duration. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1837 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06122-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06122-x