Abstract

Generational differences in travel behavior have garnered scholarly attention due to their relevance in effective tourism management and destination marketing. While conventional wisdom assumes generational homogeneity, emerging research highlights intra-generational heterogeneity. Therefore, drawing from the theory of tourism consumption systems, the study aims to identify distinct profiles based on travelers’ preferences. A sample of 980 Indian domestic travelers from different generations (Baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z) was used. The latent profile analysis revealed four distinct profiles, namely, holistic travelers, rooted travelers, spirited travelers, and seasoned social wanderers. Multinomial logistic regression was performed to determine the association between profile membership and demographic variables. The study findings are useful for marketers to segment customers beyond generations and more precisely using their travel preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The tourism sector is a key driver of the global economy, creating employment, promoting local culture, and boosting economic activities (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2024). It contributed 10% to the global GDP in 2024 (Reuters, 2024). While international tourism is gradually recovering post-pandemic (Statista, 2023), domestic tourism remains the key driver of tourism growth (McKinsey & Company, 2024). India has emerged as a major tourist hotspot, offering diverse experiences (Dixit, 2020). Reflecting global trends, domestic tourism contributes 88.4% to India’s tourism GDP (Munjal, 2023; Statista, 2024a), fueled by the rising spending power of the Indian middle class (Statista, 2024b). In 2024, domestic visitor spending increased to about 185.6 billion USD and is expected to grow to 16.4 trillion USD by the end of 2025 (Dwivedi, 2025).

Although scholarly work in tourism is growing rapidly, researchers have predominantly concentrated on international travel, often overlooking domestic tourism, particularly in emerging markets (Meenakshy et al., 2024; Sahoo et al., 2022). Previous literature has argued that market segmentation of travelers based on generational cohorts is useful due to their unique consumption patterns formed by diverse socio-cultural factors (Gardiner et al., 2015; Rita et al., 2019). However, recent studies recommend preference-based segmentation over generational cohorts in providing actionable market segments (Sahoo et al., 2022).

Very few studies have integrated generational analysis with preference-based segmentation to effectively cater to the diverse travel preferences of Indian tourists (Thangavel et al., 2021). Despite the prominence of the multi-generational trips, Anubha and Shome (2021) argue for an urgent need to examine multigenerational perspectives. Driven by recent surge in domestic tourism (Dwivedi, 2025), India has emerged as a potent market that warrants renewed academic exploration. Therefore, to address these gaps in the literature, this study aims to examine and compare the travel preferences of Baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y and Gen Z, and classify them into latent profiles, thereby promoting preference-based traveler segmentation.

Given the growth of domestic tourism and limited existing literature, this study provides valuable insights for marketers, destination marketing organizations (DMOs), and policymakers to enhance their service delivery. The identified traveler profiles will enable DMOs and marketers in tailoring services to diverse traveler groups. The study offers insights to local government administrations on key priorities of Indian tourists that enhance seamless travel experiences at the destination.

Literature review

Theoretical foundations

According to the theory of tourism consumption systems (TTCS) (Woodside and Dubelaar, 2002), the tourism consumption system is defined as “the set of related travel thoughts, decisions, and behaviors by a discretionary traveler before, during, and following a trip” (p. 120). TTCS is built upon the foundational study by Becken and Gnoth (2004), which asserts that tourists engage in a chain of decisions both before and after their trip. According to Woodside and Dubelaar (2002), a leisure tour comprises of key behavioral indicators such as “holiday duration”, “accommodation type”, “leisure destination activities”, and “travel companions” of the travelers.

In tourism research, the TTCS is often used to examine travel behavior in different contexts. Recently, Nautiyal et al. (2022) applied the dimensions of TTCS, such as travel frequency, accommodation type, and destination activities, to conceptualize the typology of yoga travelers. The study demonstrated the application of TTCS in a niche tourism context and highlighted the importance of consumption-based segmentation.

Jog et al. (2024) applied the theoretical lens of TTCS to determine whether demographic variables such as age and gender moderate the effect of souvenir attributes on post-purchase dissonance and tourists’ souvenir purchase satisfaction. Their findings identified age as an important moderator. Yang et al. (2019) demonstrated how the TTCS framework can explain tourists’ accommodation choice. These studies reinforce the integrative power of TTCS in capturing the complex interactions between tourists’ preferences, decision-making, and behavioral outcomes across diverse market segments.

Past researchers (Crompton and Petrick, 2024; George, 2021) posit that it is essential to examine the interaction of personal, psychological, social, and cultural factors to understand consumer preferences and behavior in tourism. Therefore, in this study, the TTCS framework was used to understand consumer preferences towards travel, identify segments based on preferences, and explain the characteristics of these segments.

Domestic tourism

Recent tourism literature demonstrates interest in domestic tourism destinations (Matiza and Slabbert, 2024). The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted focus toward domestic tourism (Sotiriadis, 2021). Domestic tourism is defined as “tourism involving residents of one country traveling nationally” (Choo, 2023, p. 1). Its growth over the past decade is well-documented in countries, such as North America (Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2021), Europe (Žlender and Gemin, 2020), and Australia (Gardiner et al., 2014; 2015). While countries like China, Singapore, and India are actively promoting domestic tourism (Meenakshy et al., 2024), a notable gap remains in the literature on Indian domestic travel (Ahmad et al., 2020; Sahoo et al., 2022).

Past studies (Yousefi and Marzuki, 2015; Giddy and Webb, 2018) examined the preferences of international tourists. Yousefi and Marzuki (2015) found that international tourists are often driven by a desire for novelty, adventure, and cultural exploration, and are also likely to travel for ego enhancement. Giddy and Webb (2018) found that they seek immersive experiences that allow them to engage with different cultures and landscapes. However, the authors suggest that higher costs, visa restrictions, and geopolitical concerns can be significant barriers.

In contrast, domestic tourism often emphasizes convenience, cost-effectiveness, and emotional attachment to familiar environments (Menon et al., 2021; Özel and Kozak, 2012; Shinde, 2015). Özel and Kozak (2012) found that domestic travelers tend to prioritize relaxation, family visits, and regional heritage exploration that reflect a desire for emotional connectivity and reduced travel stress. Menon et al. (2021) highlighted that the domestic visitors are influenced by diverse regional, financial, and cultural aspects. Shinde (2015) found that Indian tourists are influenced by religious beliefs, highlighting pilgrimage tourism to destinations like Varanasi, Tirupati, and Amritsar. Furthermore, experiential tourism, centered on immersive activities such as wildlife safaris, adventure sports, and rural experiences, has emerged (Sneha and Nagarjuna, 2023). Nevertheless, traveling with family members from multiple generations is common in Indian domestic tourism.

Travel preferences and generational cohort theory

Travel preferences are a critical aspect of the travel decision-making process (Karl et al., 2020), influencing choices made before, during, and after a trip (Dixit et al., 2019). In the post-pandemic era, travel preferences have notably shifted, showing changing consumer priorities (Ivanova et al., 2021). Traditionally, tourism marketers have segmented the market using demographic and psychographic variables, such as age, gender, family structure, social class, income, race, ethnicity, and lifestyle (Dixit et al., 2019).

According to generational cohort theory (GCT), individuals belonging to the same generation display similar behavior and share similar beliefs, values, and attitudes (Bravo et al., 2020), given their exposure to similar life experiences (Pennington-Gray et al., 2002). The Center for Generational Kinetics (2024) categorize them as: the silent generation (born in 1945 and before), Baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), Gen X (1965–1976), Gen Y (1977–1995), and Gen Z (1996–2015) and Gen alpha (2015–Present).

Baby boomers, having witnessed the rise of the internet and several societal changes, tend to have a revolutionary outlook towards life (Groth et al., 2017). They exhibit active social interactions (Jain and Maheshwari, 2020) and use the internet to seek information before making purchase decisions (Groth et al., 2017). They consider vacation as an opportunity to escape their daily routine and to maintain a healthy lifestyle (Tomić et al., 2019). Whereas, the Gen X are adaptive and flexible (Jain and Maheshwari, 2020). They follow a conventional approach to balance between Baby boomers and Gen Y (Jain and Maheshwari, 2020). Their choice of destination is often influenced by their family members (Li et al., 2013) and they enjoy adventure tours and outspend Baby boomers on their vacations (Tomić et al., 2019).

Gen Y are tech-savvy (Jain and Maheshwari, 2020) and they use technology to gather information before planning vacations (Tomić et al., 2019). They travel frequently and prefer shorter vacations (Lewis et al., 2021). Therefore, they are considered as “next generation” in the travel industry (Tomić et al., 2019). Currently, Gen Z has emerged as a significant consumer base in the tourism sector (Robinson and Schänzel, 2019). They are considered to be intensely anxious and distrustful (Hertz, 2017). This may be due to their early life experience of chaos, uncertainty, volatility, and complexity in the socio-economic environment (Robinson and Schänzel, 2019). They crave safety and financial security as they have never seen a world without war and terrorism (Pinho and Gomes, 2024; Robinson and Schänzel, 2019). Butnaru et al. (2022) posit that Gen Z’s inclination toward responsible travel practices is their defining characteristic. They consider traveling to seek adventure, novelty (Robinson and Schänzel, 2019), and extraordinary experiences (Haddouche and Salomone, 2018).

Past studies on intergenerational differences focused on destination preferences (Huang and Lu, 2017; Li et al., 2013), lifestyles of mountain tourists (Špindler et al., 2025); gastronomic destination preferences (Lebrun and Bouchet 2024; Torres-Casado, López-Mosquera, 2025)); local food consumption (Chen et al., 2024); domestic destination attractiveness perception of Gen Y and Gen Z (Pompurová et al., 2023); information search (Beldona, 2005; Huang and Lu, 2017; Hysa et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2015; Li et al., 2013; Ruiz-Equihua et al., 2022); and online review usage for trip planning (Amaro et al., 2019). Numerous studies have investigated the use of eWOM, specifically among Gen Y (Anubha and Shome, 2021; Bevan-Dye, 2020; Kim and Hwang, 2022; Zhang et al., 2017), as they are the major target segment for hospitality (Heyes and Aluri, 2018) and tourism (Anubha and Shome, 2021; Giachino et al., 2020; Rita et al., 2019).

Furthermore, past studies often focused on Gen Y’ travel behavior (Alemi et al., 2018; Anubha and Shome, 2021; Choudhary and Gangotia, 2017; Giachino et al., 2020; Kaihatu et al., 2021; Lewis et al., 2021; Rita et al., 2019; Ruiz-Equihua et al., 2022). For instance, Giachino et al. (2020) examined the motivation for Gen Y to choose mountain tourism and identified factors like nature and wildlife, sport, relaxation and quiet, trendy location, and food and beverages as their motivators. Rita et al. (2019) found that relaxation and escaping the ordinary are the common motivational factors for Gen Y from the USA and UK. As Gen Y are considered to be the mainstream consumption group (Sun et al., 2020), there has been extensive attention on their travel preferences. Very few studies have been conducted to understand the travel preferences of older consumers like Baby boomers (Otoo and Kim, 2020; Otoo et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021) and Gen X (Kim et al., 2015). This evidence also suggests that in South America, Africa, and Asian regions, the older tourism segment is under-researched (Hung and Lu, 2015). In Indian travel literature, generational cohort studies have been predominantly focused on Gen Y (Anubha and Shome, 2021; Choudhary and Gangotia, 2017).

Recent studies on Gen Z’s travel behavior examined the impact of social networking sites (Etrata et al., 2025) and user-generated content (Correia et al., 2025) on their behavioral intentions. Furthermore, these studies have focused primarily on sustainable travel behavior (Lima-Vargas et al., 2024; Liu-Lastres et al., 2025) and the gastronomic tourism behavior of Gen Z (Made Purnami et al., 2025; Purwanegara et al., 2025). A bibliometric study of Gen Z and tourism research (Ivasciuc et al., 2024) reveals that though there is increased research on the aforementioned research themes, there is still a void in unearthing new insights into Gen Z’s preferences.

Research gaps

The literature review reveals three key research gaps. First, prior studies often consider generational cohorts as homogeneous groups with uniform behavioral patterns, despite growing evidence of intra-generational differences in travel preferences (Glover and Prideaux, 2009; Otoo et al., 2020; Prayag et al., 2022). This challenges traditional segmentation approaches and underscores the need to reassess traveler preferences for more accurate market segmentation. Second, although preference-based segmentation is gaining practical relevance, it has rarely been combined with generational analysis to produce actionable traveler profiles (Sahoo et al., 2022), limiting a deeper understanding of evolving tourist decision-making. Profiling consumer segments using the TTCS framework, combined with key demographic indicators like generational cohorts, can offer a more nuanced understanding of the tourism market. Finally, despite the rapid growth of India’s tourism sector, existing literature has largely focused on international travel, overlooking domestic travel preferences. This is a significant gap, as domestic and international tourists often display distinct behavioral and consumption patterns (Chatterjee et al., 2017; Rishi and Chatterjee, 2023). Therefore, the study aims to address the following research question: “Are there any distinct profiles based on key travel preferences across Baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z?” This study is among the few to collect extensive data across four generations, aiming to classify tourists into latent profiles and extend preference-based traveler segmentation in India, grounded in the TTCS framework.

Methodology

This study employed a survey method to collect data from 980 Indian travelers across four generations (Baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z), aged 18 to 78 years. This age group represents the Indian travelers who have decision-making power. Although the target population is finite, no comprehensive sampling frame exists for generational traveler groups. Therefore, the sample was drawn from Facebook travel group members, leveraging the platform’s extensive reach in India. According to NapoleonCat (2024), India has over 566 million Facebook users, amounting to 39% of the national population and making it one of the largest user bases globally (Statista, 2024c). The selection criterion required respondents to be members of active Indian Facebook travel groups, administered by Indians and consisting of at least 5000 members.

Quota sampling was employed, as it is effective when probability sampling is not feasible due to the lack of a sampling frame (Seow et al., 2017). It also helps in obtaining a sample that closely represents the target population (Sharma, 2017). Quotas were set based on generational cohorts (age groups) to ensure balanced representation across Baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z. A minimum of 200 respondents from each generation was considered sufficient for the intended analysis.

To reduce selection bias inherent in quota sampling, the questionnaire link was distributed across diverse Facebook travel groups with members from varied age groups. The number of responses across different cohorts was monitored to ensure inclusivity, minimizing the overrepresentation of specific demographics. A total of 980 completed responses were received, and the demographic profile of the respondents is presented in Table 1. The differences between group sizes were relatively small, with the largest group (Gen Y with 262 respondents) and the smallest group (Baby boomers with 233 respondents) differing by only 29 individuals. The variation across the groups was approximately 11%, demonstrating reasonable group equivalence.

Survey instrument and variables

Taking cues from Woodside and Dubelaar (2002), several behavioral indicators of travel preferences were measured, such as “holiday duration,” “accommodation type,” “leisure destination activities,” and “travel companions.” Holiday duration assessed whether travelers preferred long holidays, short holidays, weekend getaways, and day trips. Accommodation types were classified as accommodation at a hotel, accommodation with family or friends, accommodation at bed and breakfast, accommodation at homestays, and camping. Leisure destination activities included sampling local food at destinations, sightseeing, shopping, attending events like music festivals or sporting competitions, visiting museums, outdoor activities like cycling or hiking, and partying. Travel companions included traveling alone, traveling with family, traveling with friends, and traveling with group travel packages. All the questions were measured using a five-point Likert scale.

The face validity of the survey instrument was assessed by four experts in the area of consumer behavior and marketing research. Based on the qualitative feedback and recommendations obtained from the experts, the survey instrument was revised. Furthermore, 11 individuals (non-experts) from the target population were also considered to assess whether the survey instrument effectively captured all the important travel preferences of domestic travelers. This step further refined the questions included in the survey instrument to suit the context of Indian domestic tourism. After implementing revisions based on the feedback, a final survey instrument was shared in Facebook travel groups.

Results

Following Mekoth et al. (2024), an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to reduce the dimensions and identify factors. It was followed by latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify distinct profiles of travelers based on the factors. Finally, a multinomial logistic regression (MLR) was used to examine the association between the profile membership and demographic variables and examine for the confounding effects. The descriptive statistics for the variables across four generations are presented in Table 2.

Factor analysis

The underlying dimensions of the respondents’ travel preferences were identified using EFA. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.05) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (0.739) scores indicated the data is suitable for principal component analysis. Varimax rotation was used to examine travel preferences. Factor loadings of at least 0.50 were deemed acceptable for item inclusion, and an eigenvalue of 1.0 was employed for the factor extraction criterion (Hair et al., 2017). After removing six items with low factor loadings (<0.5), varimax rotation was used to re-analyze the remaining items (See Table 3). Five components explained 62.089% of the total variance, each with high reliability coefficients and eigenvalues exceeding 1.00. The identified factors were: planned holiday, impromptu holiday, holiday with acquaintances, basic travel priorities, and exciting destination experience. Internal consistency for each factor was confirmed using Cronbach’s Alpha, all exceeding the 0.7 threshold. For factors with fewer items, inter-item correlations were examined in line with Pallant’s (2020) recommendations, and scores were within the acceptable range of 0.2–0.4. Following this, LPA was conducted to identify traveler profiles based on these factors.

Latent profile analysis

LPA is a person-centered (Howard and Hoffman, 2017; Spurk et al., 2020), mixture-model (Magidson and Vermunt, 2002; Song and Shim, 2021) technique that addresses the identification of unobserved subpopulations (latent profiles) within a heterogeneous population by utilizing a specific set of variables. In this study, LPA was employed to identify unobserved subgroups of travelers based on the travel preference factors determined and established from the EFA. Past tourism research on travel motivation (Song and Bae, 2018), and tourist perceptions of an urban park (Song and Shim, 2021) employed LPA to identify latent subgroups within the heterogeneous population. Unlike traditional clustering techniques, such as k-means or hierarchical clustering, which rely on researchers’ subjective interpretations (Bergman and Trost, 2006), the LPA identifies subgroups using rigorous statistical parameters, including entropy and fit indices (Song and Shim, 2021). Therefore, the current study employs LPA, considering its superiority and robustness, to categorize travelers from four generations based on their travel preferences.

This study uses the snowRMM (Seol, 2025) module built in Jamovi version 2.6 (2024) to conduct the LPA. Jamovi is an easy-to-use statistical tool that can conduct many single and multivariate analyses (Şahi̇ and Aybek, 2019). While examining the LPA results, the model fit parameters such as Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and entropy were evaluated based on the recommendations of the existing studies (Dong et al., 2023; Kwarikunda et al., 2022; Nwosu et al., 2023; Wang and Ngok, 2024). These studies suggest that the lower values for BIC and AIC, reflect a better model fit. Dong et al. (2023) suggest the entropy level which determines the quality of classification in LPA must be above 0.6. The entropy below 0.6 is unacceptable as it indicates an individual classification error rate as high as 20% (Dong et al., 2023). Furthermore, bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) was also examined. The BLRT p-values below 0.05 indicate that a model with k profiles is a better fit than a model with k-1 profiles (Gonzálvez et al., 2021; Nwosu et al., 2023). Gonzálvez et al. (2021) also recommends to have at least 25 members per profiles for meaningful interpretation.

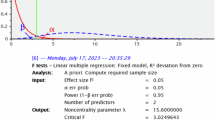

While the model with six profiles had lowest AIC value, the model with four profiles was found to have a better classification accuracy and significant BLRT-p value (See Table 4). Posterior‐probability diagnostics also showed a satisfactory separation of individuals into four profiles (Prob_max = 0.88; Prob_min = 0.70). Furthermore, the six-profile model produced the smallest class comprising only 4% of the sample, that raised concerns about interpretability. Therefore, the model with four profiles was evaluated as the best-fitting model. Figure 1 shows the visualization of the travel preference factors (estimated means) across four profiles (classes).

Profile 1 comprised 16.3% of the total sample. Members exhibited moderate preferences across most travel preference factors, with the lowest scores for basic travel priorities. This suggests a modest and balanced approach to travel planning, with less emphasis on essentials and more flexibility in their overall travel behavior. Therefore, they were named “Holistic travelers.”

Profile 2 accounted for 19.1% of the sample. Members of this profile showed the strongest preference for basic travel priorities and the least interest in impromptu holidays, indicating a highly structured and cautious travel style. Their moderate interest in holiday with acquaintances further reflects a grounded and socially rooted approach to travel. Accordingly, this group was labeled “Rooted travelers.”

Profile 3 represented 56.1% of the sample, the largest segment. Members of this profile showed the strongest preference for exciting destination experiences and ranked second in impromptu holiday preferences, reflecting their desire to travel spontaneously and travel to exciting destinations. Given their enthusiasm for dynamic and adventurous travel, this group was labeled “Spirited travelers.”

Profile 4 comprised of only 8.5% of the sample and showed the highest preference for impromptu holidays and holiday with acquaintances, but the lowest interest in exciting destination experiences. This suggests that their travel behavior is driven more by social connection than by novelty or adventure. Reflecting their emphasis on companionship and spontaneity, this group was labeled “Seasoned social wanderers.” Demographic characteristics for all four profiles are summarized in Table 5.

Multinomial logistic regression

After identifying the latent profiles, MLR was conducted to investigate how demographic variables predict the probability of membership in each profile relative to a reference group. It examined whether generation, gender, education, income, employment status, and marital status predicted membership in the four travel preferences profiles (reference class = Profile 1). The results revealed the overall model had better fit and goodness of fit than the intercept-only model, χ² (42) = 243.35, p < 0.001, and accounted for a modest but meaningful share of the variance (McFadden R² = 0.11; Nagelkerke R² = 0.14). Fit indices were also acceptable (AIC = 2091.33; BIC = 2311.27) (See Table 6).

Omnibus likelihood-ratio tests (See Table 7) showed that generation, education, income, and employment status each contributed uniquely to the model (p < 0.05), whereas gender and marital status did not.

Key predictors

The results revealed that compared to Baby boomers (reference category), members of Gen Z were only 0.13 times likely to occupy Profile 2 (SE = 0.62, p < 0.01) and 0.08 times likely to occupy Profile 4 (SE = 1.05, p < 0.05). Similarly, Gen Y were only 0.31 times likely to occupy Profile 4 (SE = 0.47, p < 0.05), whereas their likelihood of being members of Profile 2 and Profile 3 did not significantly differ from Baby boomers (p2 = 0.23 and p3 = 0.36). Generation X did not display a significant difference from Baby boomers across any profiles (all p > 0.05). No generations had significant differences for Profile 3. These results indicate that younger generations, specifically Gen Z, are less likely to be part of Profile 2 or Profile 4 compared to Baby boomers, whereas in the case of Profile 3, there was a negligible generational difference.

Regarding education, the individuals with a bachelor’s degree had a higher likelihood of being in Profile 2 (Rooted travelers) with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.44 (SE = 0.32, p < 0.05), Profile 3 (Spirited travelers) with an OR of 2.63 (SE = 0.26, p < 0.001), and Profile 4 (Seasoned social wanderers) with an OR of 3.31 (SE = 0.42, p < 0.01) than the individuals with below bachelor’s degree education (the reference category). A stronger pattern was observed among master’s degree holders, who were 2.64 times more likely to belong to Profile 2 (SE = 0.37, p < 0.05), 3.23 times more likely to belong to Profile 3 (SE = 0.30, p < 0.001), and 2.88 times more likely to belong to Profile 4 (SE = 0.47, p < 0.05). However, respondents with a PhD or higher level of education showed no statistically significant likelihood of belonging to Profile 2 (OR = 2.99, SE = 0.76, p > 0.05) or Profile 3 (OR = 2.83, SE = 0.68, p > 0.05). For Profile 4, no reliable estimates could be generated due to the absence of PhD participants in that group, resulting in an odds ratio and standard error of zero.

Income emerged as the strongest demographic variable, which played a significant role in profile membership. Compared to respondents with annual income less than 1 million INR, respondents with 1–2 million INR income were 6.82 times more likely to belong to Profile 2 (SE = 0.44, p < 0.001), 3.31 times more likely to belong to Profile 3 (SE = 0.42, p < 0.01), and 4.59 times more likely to belong to Profile 4 (SE = 0.50, p < 0.01). The effect was notably stronger for the highest income members (above 2 million INR). These respondents were 10.91 times more likely to be in Profile 2 (SE = 0.76, p < 0.01), 5.72 times more likely to be in Profile 3 (SE = 0.74, p < 0.05), and 7.66 times more likely to be in Profile 4 (SE = 0.82, p < 0.05) compared to the reference category.

Finally, for employment status, compared to unemployed (reference category), employed individuals were 0.32 times likely (SE = 0.45, p < 0.05) and self-employed individuals were 0.33 times likely (SE = 0.48, p < 0.05) to be in Profile 2. Whereas for Profile 3 and Profile 4, there was a negligible difference for employment status.

The overall findings highlight income, education, generation, and employment status as strongest predictors of profile membership. However, gender and marital status did not have any significant impact (p > 0.05). Table 8 summarizes the odds ratios and significance values for the MLR.

Traveler profiles

Profile 1: Holistic travelers

This profile had a mix of all four generations, and members had moderate preferences across all travel factors (refer to Fig. 1). It represents a value-oriented segment, characterized by balanced travel behavior rather than strong inclinations toward any specific dimension. The findings are consistent with existing tourism literature (Amaro et al., 2023; Fung and Jim, 2015; Carrascosa-López et al., 2021), which highlights that tourists often exhibit multi-faceted preferences when selecting destinations. This segment demonstrates a broad interest in various travel aspects, reflecting a flexible and well-rounded travel orientation.

Income and education levels provided contextual explanation for this profile. With over 94.38% earning less than 1 million INR annually, members tend to prefer balanced, budget-friendly travel. Existing travel research suggests economic factors significantly influence travel choices in developing countries (Struwig, du Preez, 2024). Additionally, 26.9% had the lowest education level, the highest among all profiles, suggesting a strong desire to gain knowledge through new experiences. This aligns with the “want-it-all” traveler segment identified in existing literature (Fung and Jim, 2015).

Profile 2: Rooted travelers

This profile had a higher representation of Baby boomers and Gen X respondents, indicating a shared preference pattern that reflects a combination of generational values and economic status. Members of rooted travelers exhibited a higher preference for basic travel priorities such as comfortable accommodation, sightseeing, and trying local food. They also preferred traveling with acquaintances, which reflects a shared orientation towards reliable and comfortable travel experiences.

The existing literature postulates that a mature generation like the Baby boomers is much more resistant to any change in their lives (Laukkanen et al., 2007), suggesting their adherence to a fixed schedule-based lifestyle (Tsadok-Cohen et al., 2023) and the emphasis on basic structured travel routines that would reduce both physical and cognitive strain (Patterson, 2006). One of the plausible explanations for this behavior can be derived from Sheth’s (1981) work, where the author states that several individuals might opt for consistency in life rather than striving for new activities. Furthermore, their preference of traveling with acquaintances might stem from their desire to develop new social connections. Existing research also provides evidence to this notion by suggesting that strong social engagement among older tourists positively contributes to their overall well-being by enhancing self-esteem (Qiao et al., 2022). The Gen X, often referred to as the ‘sandwich generation’ (Miller, 1981) are commonly tasked with the added responsibility of taking care of their children and parents (Sudarji et al., 2022). This dual caregiving role might explain their inclination for travel preferences that prioritizes basic needs and socially rewarding conversations. Given the likelihood of traveling with children or older parents, they focus on comfort, convenience, and basic needs without seeking novel experiences. Furthermore, establishing social relationships and interacting with supportive companions provides a vital outlet to cope with this challenging situation and foster a sense of emotional validation (Pashazade et al., 2024).

Profile 3: Spirited travelers

This profile predominantly consists of Gen Z and Gen Y travelers who demonstrate a dual focus on meeting basic travel needs while also seeking exciting destination experiences. Despite nearly 78.9% of the members earning less than INR 1 million annually, they report the highest travel frequency, that is, 37.27% travel once a year and 24% at least twice a year. This suggests that for spirited travelers, travel is clearly a priority, and they tend to favor value-for-money plans that balance essential comforts with engaging experiences.

These travelers also prefer an “exciting destination experience” (attending events; adventure sporting etc.) For instance, in India the number of music festivals is expected to grow exponentially from 8000 in 2018 to 16700 in 2025 (Baruah, 2023), driven predominantly by the Electronic Dance Music concert culture (Chakravarty and Bennett, 2024; Chaturvedi, 2025). Several studies (D’Andrea, 2007) have highlighted that tourism enables youth to break away from their monotonous daily routines, often through engagement in subcultures such as rave parties (D’Andrea, 2007; Boirot and Thurnell-Read, 2023; Mach et al., 2022).

Shopping has also emerged as a critical factor influencing destination choice among Indian youth, offering both psychological gratification and social value (Khan, 2019; Choi et al., 2018). Notably, while the overall tourism sector in India is growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10%, sports tourism has surged ahead with a 17.5% growth rate, making it a key driver for city branding and youth engagement (Chanda, 2024; Szmigin et al., 2017). Additionally, Indian youth increasingly gravitate toward adventure-based outdoor activities such as rafting, trekking, and camping (Kar and Roy, 2020; Times of India, 2024) as a means to seek thrill, escape routine (Brymer and Feletti, 2020; Lekies et al., 2015), and improve overall well-being (Próchniak and Próchniak, 2023).

Young consumers across several countries have demonstrated a strong preference for novel and adventurous tourism experiences (Lepp and Gibson, 2008; Williams and Soutar, 2009). For instance, youth in China and Singapore have shown a particular affinity for adventure tourism, reinforcing the relevance of our findings within Asian contexts that share similar domestic tourism dynamics (Gardiner et al., 2023). This inclination toward adventure-seeking behavior is closely linked to the concept of ‘self-identity,’ which highlights the significance of the roles that individuals occupy within the social structure and how they express them through role-consistent behavior (Gardiner et al., 2023, p.2).

Profile 4: Seasoned social wanderers

In the final profile, Baby boomers and Gen X exhibited the highest preference for holidays with acquaintances and impromptu travel. While mature generations are typically associated with structured and planned travel (Patterson, 2006; Jang and Wu, 2006), this profile deviates from the norm, revealing a segment driven by social connection and spontaneous getaways. A comparable trend was observed in Germany, where older travelers also showed a growing inclination toward making spontaneous travel decisions (Tourism Review News Desk, 2019).

A key factor explaining this behavior is that approximately 44.8% of the members are either self-employed or retired, indicating greater temporal flexibility and control over their schedules. Huber (2019) highlights that personal and professional commitments often constrain travel preferences, but once these responsibilities lessen, older individuals are more inclined to adopt new hobbies like travel. Life stage transitions, such as reduced career pressure and post-retirement freedom, enable greater spontaneity in travel planning (Hysa et al., 2021; Pascual-Fraile et al., 2024). Additionally, the awareness of limited time remaining in life influences senior tourism behavior, with Fleischer and Pizam (2002) noting that this stage is often guided by a desire for self-fulfilling experiences.

However, despite their inclination towards spontaneous travel plans, they primarily seek socially enriching connections. These members showcase a desire to travel and spend time with their close companions, like family and friends (Pascual-Fraile et al., 2024), since social engagement enhances their overall well-being and self-esteem (Qiao et al., 2022). Thus, rather than planning for exciting experiences, this profile predominantly focuses on spontaneous travel plans with a close-knit group.

Theoretical contributions

The study enhances the understanding of domestic travelers’ preferences by integrating the TTCS with GCT. This integration provides a dynamic framework for analyzing and predicting travel behavior in culturally diverse and socio-economically evolving countries like India. By identifying distinct traveler profiles, the study demonstrates how generational attributes influence travel preferences and uncovers key intra-generational variations, offering deeper insight into travel preferences across age groups. The study also confirms that generational differences serve as an important subdivision within the TTCS. The latent profile approach combines the two traditional theories and reveals the coexistence of multiple consumption system subgroups within the generational cohort.

The study empirically identifies four profiles: holistic travelers, rooted travelers, spirited travelers and seasoned social wanderers based on their travel preferences. By offering multi-layered insights into travel preference patterns across four generations, it challenges the commonly held assumption of homogeneity within generational cohorts in tourism literature. This re-evaluation contributes meaningfully to the advancement of GCT in the tourism domain. Also, by illustrating how generational shifts in lifestyle and values influence travel-related consumption systems, the study reinforces the validity and relevance of integrating GCT with the TTCS framework.

TTCS is often contextualized in western or international tourism contexts (Li et al., 2013). By contextualizing GCT within the domestic tourism setting of an emerging market, this study offers valuable insights into India’s rapidly growing tourism landscape. The study demonstrates that the holistic travelers profile included mix of the four mainstream generation who displayed a similar pattern. While rooted travelers and seasoned social wanderers had majority of older travelers, the former emphasized basic travel priorities and family-oriented vacation whereas the latter profile members emphasized spontaneity with strong need for social connections and traveling with acquaintances. The spirited travelers, with majority younger profile members were leaning more towards excitement in their travel experiences along with fulfilling basic travel needs.

The study findings also highlight the intricacies of domestic tourist behavior thereby contributing to the growing literature on Indian domestic tourism. A report by McKinsey forecasts that India will be the biggest source of leisure tourists due to rising economic prosperity (Aggarwal et al., 2023). Therefore, it is imperative to examine the different travel preferences of Indian consumers to effectively manage the tourism market. The present study highlights the interplay between family orientations, societal bonds, and spontaneity in shaping the travel preferences of Indian domestic travelers. These findings on the consumption pattern of the younger and mature generations contributes to the evolving discourse on tourism literature.

Practical and policy implications

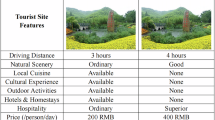

The travel preferences of Indian tourist profiles offer practical implications for DMOs and travel service providers to tailor their offerings and marketing strategies. The findings indicate that younger generations are drawn to exciting destinations and prefer traveling with acquaintances. DMOs and service providers can capitalize on this by designing social group travel packages and offering group discounts to encourage friend circles and families to travel together. Curated itineraries that combine daytime adventure activities with evening social experiences, such as café outings or nightlife options, can effectively meet both thrill-seeking and social bonding needs. Likewise, as younger travelers also value comfort, providers should ensure packages include basic amenities and conveniences. DMOs partnering with popular online travel platforms can further enhance their outreach by deploying targeted digital campaigns specifically aimed at the youth segment.

Another interesting finding of the study is the presence of older adults across three distinct travel segments. While their inclusion in the holistic and rooted traveler groups aligns with existing expectations, their presence in the “seasoned social wanderers” segment is particularly novel. These older travelers show a strong preference for impromptu holiday plans and traveling with acquaintances, indicating a desire for spontaneous, socially engaging travel experiences. DMOs targeting this segment can promote easily accessible tourist destinations ideal for short trips, especially on online travel platforms. Also, bundling tour packages with long weekend holidays can further appeal to this demographic, offering them flexible and convenient travel options that suit their evolving lifestyles.

The study highlights a strong investment opportunity for adventure sport operators in India, driven by the younger generation’s preference for exciting travel experiences. Tour operators and DMOs in lesser-known destinations should promote unique offerings like rock climbing in Malshej Ghat (Maharashtra), scuba diving in Kapu (Karnataka), and trekking at Ginnorgarh (Madhya Pradesh). With most adventure tourism concentrated in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, there’s untapped potential in promoting alternative locations. DMOs can also expand offerings to include moderately challenging activities tailored for older travelers (Wilson et al., 2017).

Beyond adventure tourism, music and sports tourism are also rapidly gaining traction in India, especially among the youth who readily travel to attend specific events. This trend presents an opportunity for DMOs to create targeted tour packages combining major events, often held in cities like Goa, Kolkata, or Delhi, with short sightseeing itineraries. Integrating event merchandise (e.g., music bands or sports teams) into these packages can further enhance the appeal. A coordinated strategy involving event promoters, local transit authorities, and merchandising partners can significantly boost tourist engagement and increase average visitor spending.

The findings suggest that basic travel elements such as sightseeing, comfortable hotel stays, and local food appeal to all generations. These should be treated as essential by DMOs, as ensuring these basics can extend visitor stays and boost revenue for mid-range hotels, eateries, and transport services. Investing in such infrastructure, especially in lesser-known destinations, is crucial to revitalizing domestic tourism in India. Also, with many tourists preferring to travel with family, enhancing family-friendly tourism facilities can make destinations more attractive. These improvements not only support tourism growth but also create new revenue streams and employment opportunities for local communities.

With over 18 million foreign tourists visiting India in 2023 (Ministry of Tourism, 2024), the country has emerged as a leading global travel destination. To enhance foreign visitor satisfaction, strategic upgrades such as multilingual signage, multilingual tour guides, and universal QR code payment systems are essential. These measures can improve tourist experiences and generate tangible returns for both DMOs and private operators. Leveraging campaigns like ‘Chalo India’ and the ‘Incredible India Content Hub,’ DMOs have both the opportunity and responsibility to deliver high-quality services, as positive word-of-mouth from foreign tourists can significantly boost the sector’s growth.

From a societal perspective, policymakers can expand pro-tourism initiatives in lesser-traveled areas to generate employment and uplift local communities. Tourism can benefit a range of stakeholders, from hotel staff and tour guides to food vendors showcasing regional cuisine. It also presents opportunities for indigenous businesses, such as Kashmir’s Khatamband or Odisha’s Pipili Chandua artwork, to gain global visibility. This can support socio-economic development through increased exports and regional growth. The findings are also applicable to other developing countries with similar demographics, offering a framework to stimulate their domestic tourism sectors.

Limitations

While the study offers valuable insights, it has certain limitations. The use of cross-sectional quantitative data restricts the understanding of how travel preferences evolve over time. Self-reported responses may also be influenced by biases like social desirability, affecting the accuracy of the findings. Moreover, relying on Facebook travel groups for data collection may exclude less tech-savvy individuals or those from rural areas with limited internet access, thus limiting the study’s overall representativeness. Another limitation is that although the study examines the role of demographic variables, such as generation, income, education, gender, employment status and marital status, it does not consider potential confounding variables such as family responsibility. Although the study incorporated various travel preferences based on Woodside and Dubelaar’s (2002) framework, it did not account for travelers’ information search behavior or their use of technology in trip planning, which are increasingly relevant in shaping modern travel decisions.

Future research directions

The limitations open avenues for future research. In the future, longitudinal studies could track changes in travel preferences across generational cohorts over time, capturing the effects of societal and economic shifts on behavior. A mixed-methods approach, especially incorporating in-depth qualitative interviews, can yield deeper insights into domestic traveler preferences. Future research may also broaden the scope by focusing on rural or economically disadvantaged travelers, offering a more inclusive view of India’s domestic tourism landscape. Further, future studies could compare domestic travelers across emerging markets to enhance generalizability. Exploring variables like family responsibilities, life-cycle stages, and external factors such as climate change or economic downturns can guide adaptive tourism strategies.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the travel preferences of Indian domestic tourists across four generational cohorts by integrating TTCS with GCT. Using latent profile analysis, it identifies four distinct traveler segments, each reflecting unique patterns shaped by generational values, socio-economic factors, and lifestyle preferences. These include: holistic travelers, rooted travelers, spirited travelers, and seasoned social wanderers. Holistic travelers, comprising a mix of all generations, exhibit similar, balanced travel preferences. Rooted travelers, primarily older cohorts, focus on basic needs and family-oriented vacations. Spirited travelers, largely younger individuals, seek adventure and excitement while ensuring comfort. Seasoned social wanderers, mostly mature travelers, value spontaneity and prefer traveling with close acquaintances, highlighting the importance of social connection.

The findings have several theoretical, practical, and policy implications. The integration of TTCS and GCT provides a robust framework for understanding tourism behaviors in culturally diverse countries like India. Practically, the insights enable DMOs and marketers to design tour packages and develop targeted marketing strategies. These findings also underscore the universal appeal of core travel elements, such as comfortable accommodation and local cuisine, across generational cohorts.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aggarwal D, Constantin M, Kalra K, Mundra N (2023) From India to the world: Unleashing the potential of India’s tourists. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/from-india-to-the-world-unleashing-the-potential-of-indias-tourists. Accessed 1 Nov 2023

Ahmad N, Menegaki AN, Al‐Muharrami S (2020) Systematic literature review of tourism growth nexus: an overview of the literature and a content analysis of 100 most influential papers. J Econ Surv 34(5):1068–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12386

Alemi F, Circella G, Handy S, Mokhtarian P (2018) What influences travelers to use Uber? Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of on-demand ride services in California. Travel Behav Soc 13:88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.06.002

Amaro S, Andreu L, Huang S (2019) Millennials’ intentions to book on Airbnb. Curr Issues Tour 22(18):2284–2298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1448368

Amaro S, Chaves NB, Henriques C, Barroco C (2023) Motivation-based segmentation of visitors to a UNESCO Global Geopark. Geoheritage 15(2):79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-023-00797-5

Anubha N, Shome S (2021) Intentions to use travel eWOM: Mediating role of Indian urban millennials’ attitude. Int J Tour Cities 7(3):640–661. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2020-0073

Baruah A (2023) Music concerts are set to be a ₹1000 crore business in India. CNBC TV18. https://www.cnbctv18.com/entertainment/music-concerts-are-set-to-be-a-1000-crore-business-in-india-18523781.htm. Accessed 26 Sep 2023

Becken S, Gnoth J (2004) Tourist consumption systems among overseas visitors: reporting on American, German, and Australian visitors to New Zealand. Tour Manag 25(3):375–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00133-X

Beldona S (2005) Cohort analysis of online travel information search behavior: 1995–2000. J Travel Res 44(2):135–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505278995

Bergman LR, Trost K (2006) The person-oriented versus the variable-oriented approach: are they complementary, opposites, or exploring different worlds? Merrill-Palmer Q 52(3):601–632. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0023

Bevan-Dye AL (2020) Antecedents of Generation Y consumers’ usage frequency of online consumer reviews. Span J Mark -ESIC 24(2):193–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-12-2019-0102

Boirot A, Thurnell-Read T (2023) From stag party tourism to alcohol cultures. J Festive Stud 5:254–271. https://doi.org/10.33823/jfs.2023.5.1.179

Bravo R, Catalán S, Pina JM (2020) Intergenerational differences in customer engagement behaviours: An analysis of social tourism websites. Int J Tour Res 22(2):182–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2327

Brymer E, Feletti F (2020) Beyond risk: The importance of adventure in the everyday life of young people. Ann Leis Res 23(3):429–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1659837

Butnaru GI, Niţă V, Melinte C, Anichiti A, Brînză G (2022) The nexus between sustainable behaviour of tourists from Generation Z and factors influencing environmental quality. Sustainability 14(19):12103. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912103

Carrascosa-López C, Carvache-Franco M, Mondéjar-Jiménez J, Carvache-Franco W (2021) Understanding motivations and segmentation in ecotourism destinations: application to natural parks in Spanish Mediterranean area. Sustainability 13(9):4802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094802

Chakravarty D, Bennett A (2024) Is there an Indian way of raving? Reading the cultural negotiations of Indian youth in the trans-local EDM scene. J Youth Stud 27(6):802–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2023.2174008

Chanda K (2024) Not just cricket, sports tourism is also driven by football, tennis, and F1: Monish Shah of DreamSetGo. Forbes India. https://www.forbesindia.com/article/lifes/not-just-cricket-sports-tourism-is-also-driven-by-football-tennis-and-f1-monish-shah-of-dreamsetgo/93479/1. Accessed 26 Sep 2024

Chatterjee TK, Rishi B, Nargundkar R (2017) A motive-based segmentation of Indian domestic tourists. Int J Indian Cult Bus Manag 14(2):162–176. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJICBM.2017.081972

Chaturvedi RM (2025) Concert economy is boosting tourism, creating jobs: PM Modi. The Economic Times. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/media/entertainment/concert-economy-is-boosting-tourism-creating-jobs-pm-modi/articleshow/117649625.cms. Accessed 28 Jan 2025

Chen J, Xu A, Tang D, Zheng M (2024) Divergence and convergence: a cross-generational study on local food consumption. Sci Rep 14:12681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64284-1

Choi M, Law R, Heo CY (2018) An investigation of the perceived value of shopping tourism. J Travel Res 57(7):962–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517726170

Choo H (2023) Domestic tourism. In: Jafari J, Xiao H (eds) Encyclopedia of tourism. Springer, pp 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_255-2

Choudhary P, Gangotia A (2017) Do travel decision-making styles and gender of Generation Y have any association with travel information share on social networking sites? J Hosp Tour Technol 8(2):152–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-09-2016-0052

Correia R, Aksionova E, Venciute D, Sousa J, Fontes R (2025) User-generated content’s influence on tourist destination image: a generational perspective. Consum Behav Tour Hosp. https://doi.org/10.1108/CBTH-11-2023-0208

Crompton JL, Petrick JF (2024) A half-century reflection on pleasure vacation motives. Ann Tour Res 104:103692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103692

D’Andrea A (2007) Global nomads: Techno and new age as transnational countercultures in Ibiza and Goa. CiNii. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA84905522. Accessed 26 Sep 2024

Dixit SK (2020) Special issue: Tourism in India. Anatolia 31(2):177–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1749454

Dixit SK, Lee K-H, Loo PT (2019) Consumer behavior in hospitality and tourism. J Glob Scholar Mark Sci 29(2):151–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/21639159.2019.1577159

Dong J, Chen J, Li Y, Huang X, Rong X, Chen L (2023) Relationship between freshmen’s psychological health and family economic status in Chinese universities: a latent profile analysis. Psychol Res Behav Manag 16:3489–3502. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s424798

Dwivedi M (2025) India’s tourism sector hits new high: WTTC reports Rs 3.1 trillion in international spend. Economic Times. https://travel.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/research-and-statistics/figures/indias-tourism-sector-surges-31-trillion-in-international-spending-reported-by-wttc/121625678. Accessed 4 Jun 2025

Etrata Jr AE, Torres JB, Raborar JLO (2025) Factors influencing Filipino Generation Z’s travel intention and behavior: perceived use of social networking sites. Rev Integr Bus Econ Res 14(1):553–571

Fleischer A, Pizam A (2002) Tourism constraints among Israeli seniors. Ann Tour Res 29(1):106–123

Fung CKW, Jim CY (2015) Segmentation by motivation of Hong Kong Global Geopark visitors in relation to sustainable nature-based tourism. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 22(1):76–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2014.999262

Gardiner S, Grace D, King C (2014) The generation effect. J Travel Res 53(6):705–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514530810

Gardiner S, Grace D, King C (2015) Is the Australian domestic holiday a thing of the past? Understanding baby boomer, Generation X and Generation Y perceptions and attitude to domestic and international holidays. J Vacat Mark 21(4):336–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715580188

Gardiner S, Janowski I, Kwek A (2023) Self-identity and adventure tourism: cross-country comparisons of youth consumers. Tour Manag Perspect 46:101061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101061

George R (2021) Tourism and hospitality consumer behaviour. In: Marketing tourism and hospitality. Palgrave Macmillan, pp 65–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64111-5_3

Giachino C, Truant E, Bonadonna A (2020) Mountain tourism and motivation: millennial students’ seasonal preferences. Curr Issues Tour 23(19):2461–2475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1653831

Giddy JK, Webb NL (2018) Environmental attitudes and adventure tourism motivations. GeoJournal 83(2):275–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9768-9

Glover P, Prideaux B (2009) Implications of population ageing for the development of tourism products and destinations. J Vacat Mark 15(1):25–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766708098169

Gonzálvez C, Sanmartín R, Vicent M, García-Fernández JM (2021) Exploring different types of school refusers through latent profile analysis and school-related stress associations. Sci Prog 104:00368504211029464. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504211029464

Groth A, Constantini G, Schlögl S (2017) Perception of source credibility within touristic virtual communities: a cross-generational examination. In: Marcus A (ed) Design, user experience, and usability: understanding users and contexts. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 10289. Springer, pp 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58640-3_34

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2017) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Haddouche H, Salomone C (2018) Generation Z and the tourist experience: tourist stories and use of social networks. J Tour Futures 4(1):69–79

Hertz N (2017) Think millennials have it tough? For “Generation K,” life is even harsher. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/29/think-millennials-have-it-tough-for-generation-k-life-is-even-harsher. Accessed 29 Nov 2017

Heyes A, Aluri A (2018) How millennials perceive leisure luxury hotels in a sharing economy? Res Hosp Manag 7(2):75–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2017.1444709

Howard MC, Hoffman ME (2017) Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches. Organ Res Methods 21:846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021

Huang Q, Lu Y (2017) Generational perspective on consumer behavior: China’s potential outbound tourist market. Tour Manag Perspect 24:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.07.008

Huber D (2019) A life course perspective to understanding senior tourism patterns and preferences. Int J Tour Res 21(3):372–387

Hung K, Lu J (2015) Active living in later life: an overview of aging studies in hospitality and tourism journals. Int J Hosp Manag 53:133–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.10.008

Hysa B, Karasek A, Zdonek I (2021) Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in Society 5.0 idea. Sustainability 13(3):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031018

Ivanova M, Ivanov IK, Ivanov S (2021) Travel behaviour after the pandemic: the case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 32(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1818267

Ivasciuc IS, Candrea AN, Ispas A, Piuaru BA (2024) A bibliometric analysis of Generation Z and tourism research: Insights from VOSviewer mapping. Adm Sci 14(12):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14120337

Jain A, Maheshwari M (2020) An exploratory study on intergenerational learning in Indian IT workspace. South Asian J Hum Resour Manag 7(2):233–256

Jamovi (2024) Software (version 2.6). The Jamovi Project. https://www.jamovi.org. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Jang SS, Wu CME (2006) Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: an examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tour Manag 27(2):306–316

Jiménez-Barreto J, Sthapit E, Rubio N, Campo S (2019) Exploring the dimensions of online destination brand experience: Spanish and North American tourists’ perspectives. Tour Manag Perspect 31:348–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.07.005

Jog D, Gumparthi VP, Jena SK (2024) The antecedents and consequences of post-purchase dissonance among tourists purchasing souvenirs: the moderating role of gender, age, and time elapsed. J Hosp Tour Manag 58:51–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.11.003

Kaihatu TS, Spence MT, Kasim A, Satrya IDG, Budidharmanto LP (2021) Millennials’ predisposition toward ecotourism: the influence of universalism value, horizontal collectivism, and user-generated content. J Ecotour 20:145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2020.1795183

Kar D, Roy PK (2020) How temperament, character, flow state and motivation play roles in adventure and non-adventure sports: a comparative study. Eur J Phys Educ Sport Sci 6(9). https://doi.org/10.46827/ejpe.v6i9.3461

Karl M, Bauer A, Ritchie WB, Passauer M (2020) The impact of travel constraints on travel decision-making: a comparative approach of travel frequencies and intended travel participation. J Destin Mark Manag 18:100471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100471

Khan S (2019) Travel lifestyle of young Indian students: “Gender distinct” or “gender blurred.” Int J Hosp Tour Syst 12 (2)

Kim H, Xiang Z, Fesenmaier DR (2015) Use of the internet for trip planning: a generational analysis. J Travel Tour Mark 32(3):276–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.896765

Kim JY, Hwang J (2022) Who is an evangelist? Food tourists’ positive and negative eWOM behavior. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 34(2):555–577. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2021-0300

Kwarikunda D, Schiefele U, Muwonge CM, Ssenyonga J (2022) Profiles of learners based on their cognitive and metacognitive learning strategy use: occurrence and relations with gender, intrinsic motivation, and perceived autonomy support. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:294. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01322-1

Laukkanen T, Sinkkonen S, Kivijärvi M, Laukkanen P (2007) Innovation resistance among mature consumers. J Consum Mark 24(7):419–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760710834834

Lebrun A-M, Bouchet P (2024) Dining-out preferences of domestic tourists at a gastronomic destination: the major influence of localness in France. Tour Manag Perspect 50:101217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2023.101217

Lekies KS, Yost G, Rode J (2015) Urban youth’s experiences of nature: Implications for outdoor adventure recreation. J Outdoor Recreat Tour 9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2015.03.002

Lepp A, Gibson H (2008) Sensation seeking and tourism: tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice. Tour Manag 29(4):740–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.08.002

Lewis C, Nelson K, Black R (2021) Moving Millennials out of the too hard basket: exploring the challenges of attracting Millennial tourists to rural destinations. J Hosp Tour Manag 46:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.11.012

Li X, Li X, Hudson S (2013) The application of generational theory to tourism consumer behavior: an American perspective. Tour Manag 37:147–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.01.015

Lima-Vargas AE, Martínez-González O, Geronimo-Cruz J, Lima-Vargas S (2024) Sustainable behavior of Generation Z tourists’ water consumption. Sustainability 16(22):9651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229651

Liu-Lastres B, Bao H, Cecil A (2025) Exploring gaps in young generations’ sustainable travel behavior: a mixed-methods study. J Sustain Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2025.2453693

Mach L, Connors J, Lechtman B, Plante S, Uerling C (2022) Party tourism impacts on local stakeholders. Anatolia 33(2):222–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2022.2040914

Made Purnami N, Wayan Mujiati N, Putu Laksmi Danyathi A, Siwi Kartika Sari U, Komang Dea Marcellina Putri Darmada D (2025) Culinary connections: the mediating role of customer brand co-creation behavior in gastronomic and revisit intentions. Innov Mark 21(1):26–36. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.21(1).2025.03

Magidson J, Vermunt JK (2002) Latent class models for clustering: a comparison with K-means. Can J Mark Res 20:36–43

Matiza T, Slabbert E (2024) Destination marketing and domestic tourist satisfaction: the intervening effect of customer-based destination brand equity. J Promot Manag 30(2):302–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2023.2253240

McKinsey & Company (2024) The state of tourism and hospitality 2024. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel/our-insights/the-state-of-tourism-and-hospitality-2024. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Meenakshy M, Prasad KDV, Bolar K, Shyamsunder C (2024) Electronic word-of-mouth intentions in personal and public networks: a domestic tourist perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–15

Mekoth N, Koloth S, Thomson AR (2024) Segmentation based on attitude: a cultural tourist dichotomy. Anatolia 35(4):804–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2024.2322621

Menon S, Bhatt S, Sharma S (2021) A study on envisioning Indian tourism–through cultural tourism and sustainable digitalization. Cogent Soc Sci 7(1):1903149. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1903149. Article

Miller DA (1981) The ‘sandwich’ generation: adult children of the aging. Soc Work 26(5):419–423

Ministry of Tourism (2024) Year End Review-2024: Ministry of Tourism. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2087824. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Munjal P (2023) A systemic analysis of the impact of the pandemic on the Indian tourism economy. Margin J Appl Econ Res 17(1–2):113–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/00252921231200209

NapoleonCat (2024) Facebook users in India. NapoleonCat. https://napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-india/2024/02/. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Nautiyal R, Albrecht JN, Carr A (2022) Conceptualising a tourism consumption-based typology of yoga travellers. Tour Manag Perspect 43:101005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101005

Nwosu KC, Wahl WP, Nwikpo MN, Hickman GP, Ezeonwunmelu VU, Akuneme CC (2023) School refusal behaviours profiles among Nigerian adolescents: differences in risk and protective psychosocial factors. Curr Psychol 42:28564–28578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03890-6

Otoo FE, Kim S (2020) Analysis of studies on the travel motivations of senior tourists from 1980 to 2017: progress and future directions. Curr Issues Tour 23(4):393–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1540560

Otoo FE, Kim S, Park J (2020) Motivation-based segmentation of Chinese senior travelers: the role of preferences, sociodemographic, and travel-related features. J Vacat Mark 26(4):457–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766720942550

Özel ÇH, Kozak N (2012) Motive-based segmentation of the cultural tourism market: a study of Turkish domestic tourists. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 13(3):165–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2012.645199

Pallant J (2020) SPSS survival manual. Routledge, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117445

Pan T, Shu F, Kitterlin-Lynch M, Beckman E (2021) Perceptions of cruise travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: market recovery strategies for cruise businesses in North America. Tour Manag 85:104275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104275

Pascual-Fraile MDP, Villacé-Molinero T, Talón-Ballestero P, Chaperon S (2024) Post-pandemic collaborative destination marketing: effectiveness and impact on different generational audiences. J Vacat Mark. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667231224091

Pashazade H, Maarefvand M, Abolfathi Momtaz Y, Abdi K (2024) Coping strategies of the sandwich generation in the care process: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 24(1):3373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-14501-0

Patterson IR (2006) Growing older: tourism and leisure behaviour of older adults. CABI, Wallingford

Pennington-Gray L, Kerstetter DL, Warnick R (2002) Forecasting travel patterns using Palmore’s cohort analysis. J Travel Tour Mark 13(1–2):125–143. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v13n01_09

Pinho M, Gomes S (2024) Generation Z as a critical question mark for sustainable tourism—an exploratory study in Portugal. J Tour Futures 10(3):486–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-07-2022-0171

Pompurová K, Šimočková I, Rialti R (2023) Defining domestic destination attractiveness: Gen-Y and Gen-Z perceptions. Curr Issues Tour 27:2004–2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2220953

Prayag G, Aquino RS, Hall CM, Chen N, Fieger P (2022) Is Gen Z really that different? Environmental attitudes, travel behaviours and sustainability practices of international tourists to Canterbury, New Zealand. J Sustain Tour 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2144241

Próchniak P, Próchniak A (2023) Adventure recreation in blue spaces and the wellbeing of young Polish adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(5):4472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054472

Purwanegara MS, Windasari NA, Perdhana HF, Ashadi MFR, Aprilianty F (2025) Improving gastro-tourism experience through 3D virtual attractions: evidence from tourists’ self-reported and neurophysiological responses. J Hosp Tour Technol 16(2):229–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-01-2024-0022

Qiao G, Ding L, Xiang K, Prideaux B, Xu J (2022) Understanding the value of tourism to seniors’ health and positive aging. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031476

Reuters (2024) Travel industry to contribute record $11 trillion to global GDP in 2024. Reuters Business. https://www.reuters.com/business/travel-industry-contribute-record-11-trillion-global-gdp-2024-2024-09-03. Accessed 3 Sep 2024

Rishi B, Chatterjee TK (2023) Typology of Indian domestic tourists: clustering based on motives to visit. FIIB Bus Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145231151328

Rita P, Brochado A, Dimova L (2019) Millennials’ travel motivations and desired activities within destinations: a comparative study of the US and the UK. Curr Issues Tour 22(16):2034–2050. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1439902

Robinson VM, Schänzel HA (2019) A tourism inflex: generation Z travel experiences. J Tour Futures 5(2):127–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0014

Ruiz-Equihua D, Casaló LV, Romero J (2022) How old is your soul? Differences in the impact of eWOM on Generation X and millennials. J Hosp Tour Insights 5(3):553–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-10-2020-0193

Şahi̇ NM, Aybek E (2019) Jamovi: an easy to use statistical software for the social scientists. Int J Assess Tools Educ 6:670–692. https://doi.org/10.21449/ijate.661803

Sahoo BK, Nayak R, Mahalik MK (2022) Factors affecting domestic tourism spending in India. Ann Tour Res Empir Insights 3(2):100050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2022.100050

Seol (2025) SnowRMM: Rasch Mixture, LCA, and Test Equating Analysis. (Version 5.9.1) [Jamovi Module]. GitHub. https://github.com/jamovi/snowrmm. Accessed 15 Jul 2025

Seow AN, Choong YO, Moorthy K, Chan LM (2017) Intention to visit Malaysia for medical tourism using the antecedents of Theory of Planned Behaviour: a predictive model. Int J Tour Res 19(3):383–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2120

Sharma G (2017) Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. Int J Appl Res 3(7):749–752. https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2017/vol3issue7/PartK/3-7-69-542.pdf

Sheth JN (1981) Psychology of innovation resistance: the less developed concept (LDC), in diffusion research. Res Mark 4(3):273–282

Shinde KA (2015) Religious tourism and religious tolerance: Insights from pilgrimage sites in India. Tour Rev 70(3):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-10-2013-0056

Silva O, Medeiros T, Vieira V, Furtado S (2021) Motivations of senior tourists: the case of the Azores Islands, Portugal. Anatolia 32(4):617–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2021.1999758

Sneha N, Nagarjuna G (2023) Experiential tourism: nature-based tourism trends in India. In: The Routledge handbook of nature-based tourism development. Routledge, pp 383–395

Song H, Bae SY (2018) Understanding the travel motivation and patterns of international students in Korea: using the theory of travel career pattern. Asia Pac J Tour Res 23:133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1410193

Song H, Shim C (2021) Comparing resident and tourist perceptions of an urban park: a latent profile analysis of perceived place value. J Sustain Tour 29:1180–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1872586

Sotiriadis M (2021) Tourism destination marketing: academic knowledge. Encyclopedia 1(1):42–56. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1010007

Špindler T, Gorenak M, Lesjak M (2025) Changing lifestyles through generations: the case of active sports tourists in mountains. J Sport Tour 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2025.2484178

Spurk D, Hirschi A, Wang M, Valero D, Kauffeld S (2020) Latent profile analysis: a review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J Vocat Behav 120:103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445

Statista (2023) Global tourism’s slow recovery from the pandemic. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/30879/international-tourist-arrivals-and-direct-impact-of-tourism-on-gdp/. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Statista (2024a) Distribution of travel and tourism GDP in India FY 2023, by type of visitor. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1279385/india-travel-and-tourism-gdp-by-type-of-visitor/. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Statista (2024b) Domestic tourism in India. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/5733/domestic-tourism-in-india/#topicOverview. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Statista (2024c) Leading countries based on the number of Facebook users as of January 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/268136/top-15-countries-based-on-number-of-facebook-users/. Accessed 15 Jul 2024

Struwig J, du Preez EA (2024) The effect of income on the relationship between travel motives and destination choices. South Afr J Econ Manag Sci 27(1):5286

Sudarji S, Panggabean H, Marta RF (2022) Challenges of the sandwich generation: stress and coping strategy of the multigenerational care. Indigenous: J Ilm Psikol 7(3):263–275

Sun S, Law R, Zhang M (2020) An updated review of tourism-related experimental design articles. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25(7):710–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1699128

Szmigin I, Bengry-Howell A, Morey Y, Griffin C, Riley S (2017) Socio-spatial authenticity at co-created music festivals. Ann Tour Res 63:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.12.007

Thangavel P, Pathak P, Chandra B (2021) Millennials and Generation Z: a generational cohort analysis of Indian consumers. Benchmark Int J 28(7):2157–2177. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-01-2020-0050

The Center for Generational Kinetics (2024) Generational breakdown: Info about all of the generations. GenHQ. https://genhq.com/faq-info-about-generations. Accessed 26 Sep 2024

Times of India (2024) The future of adventure tourism: trends to watch. Times India Travel. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/things-to-do/the-future-of-adventure-tourism-trends-to-watch/articleshow/110852980.cms. Accessed 9 Oct 2024

Tomić S, Leković K, Tadić J (2019) Consumer behaviour: the influence of age and family structure on the choice of activities in a tourist destination. Econ Res Ekon Istraž 32(1):755–771. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1579663

Torres-Casado B, López-Mosquera N (2025) From Baby Boomers to Z: gastronomic preferences and the generational framework of experience and branding. J Destin Mark Manag 37:101003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2025.101003

Tourism Review News Desk (2019) Germans travel a lot, no matter their age. Tourism Review News Desk. https://www.tourism-review.com/germans-travel-a-lot-young-and-old-news11147. Accessed 22 Jul 2019

Tsadok-Cohen R, Cohen Elimelech O, Ferrante S, Meyer S (2023) You need to set a daily schedule’: understanding successful aging via three-sided viewpoints. Healthcare 11(22):3005. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11223005

Wang Z, Ngok K (2024) Non-coresidential intergenerational relations from the perspective of adult children in China: typology and social welfare implications. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03028-y

Williams P, Soutar GN (2009) Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Ann Tour Res 36(3):413–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.02.002

Wilson DL, Hallo JC, Sharp JL, Mainella HFP, McGuire FA (2017) Activity selection among baby boomer national park visitors: the search for a sense of adventure. J Outdoor Recreat Tour 19:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.06.001

Woodside AG, Dubelaar C (2002) A general theory of tourism consumption systems: a conceptual framework and an empirical exploration. J Travel Res 41(2):120–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728702237412

World Travel and Tourism Council (2024) Economic impact report: Global trends. World Travel and Tourism Council. https://researchhub.wttc.org/product/economic-impact-report-global-trends. Accessed 15 Feb 2024

Yang Y, Tan KPS, Li X (2019) Antecedents and consequences of home-sharing stays: Evidence from a nationwide household tourism survey. Tour Manag 70:15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.004