Abstract

The impact of scientific research beyond academia is receiving increasing attention from scientists, science policy, and society in general. However, the mechanisms driving this impact remain unclear. This study systematically reviews existing theoretical models and seeks empirical evidence from the REF impact case data. Through grounded coding analysis of 200 cases across four units of assessment, six stages of research generating impact were identified – problem identification, research conduct, output production, output utilization, impact formation, and multi-stakeholder interaction. These stages encompass 10 key elements and 43 corresponding sub-categories, forming a novel theoretical model. Comparative analysis revealed that, while the generation of research impact beyond academia generally follows a similar logic across disciplines, obvious differences exist in motivation, research approach, forms of outputs, types of impacts, etc. We provide four typical cases for illustration. Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of impact generation processes for the societal benefits of scientific research, and provide a basis for research managers to assess scientific contributions according to their distinct characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The traditional mode of knowledge production, which was predominantly centered within scientific institutions and structured by scientific disciplines, has evolved into a more diverse framework known as “Mode 2” knowledge production, which is characterized by a broader array of locations, practices, and guiding principles (Gibbons et al., 1994; Hessels, Van Lente 2008). In this context, a wide range of stakeholders – including evaluators, researchers, practitioners, and funders – are increasingly seeking to understand how scientific research makes a difference in the real world (Hill, 2016). An understanding of how scientific research generates impacts may contribute to developing better ways of delivering impact and serve as a means to demonstrate the contributions of science to society, to justify research funding expenditures to taxpayers, and to provide optimal evidence for future funding allocation decisions (Penfield et al., 2014).

Stakeholders are often keen to see convincing evidence of particularly useful breakthroughs in science. Such incidences are rare and have been named “extraordinary societal impact” (Sivertsen & Meijer, 2020). For example, mRNA research facilitated the development of COVID-19 vaccines, which in turn saved lives and had a global impact on public health. The example shows a typical linear impact process in which the innovation starts with basic research, is followed by applied research and development, and ends with production and diffusion (Godin, 2006). Such impact is highly valuable by significantly enhancing researchers’ awareness of social responsibility and conveying the value of scientific research to the public and funders through media dissemination or other channels. However, extraordinary impact is relatively rare because it is difficult to attribute impact beyond academia to a single study (Budtz Pedersen & Hvidtfeldt, 2023) and because impact is normally based on the “Mode 2” type of science-society interaction. More commonly observed is what can be termed “normal societal impact”, which is the result of active, productive, and responsible interactions between research institutions and societal organizations according to their purposes and aims in society (Sivertsen & Meijer, 2020). However, due to the pervasive nature of the normal impact, accurately recording the details and interactions occurring in real time remains challenging.

Although there have been attempts to explore different types of impacts, such as those that are normal and ubiquitous or extraordinary and rare, as well as to construct linear or interactive models to depict the pathways of impact generation (see Section “Linear and interactive paradigms on impact pathways”), these explorations often remain at the conceptual level. We need to know how societal impact is generated in practice. Some relevant studies have applied the impact case data provided by the Research Excellence Framework (REF) for the evaluation and funding of universities in the UK (see Section “Data”). Nevertheless, most existing research has primarily focused on the outcomes of impact, with insufficient attention paid to the process of its generation (Terämä et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2021). Even when the process is considered, it is typically confined to descriptive statistics of content elements, without progressing to theoretical depth or the development of a systematic model (Biri et al., 2014; Stevenson et al., 2023).

The dual aims of this study are to develop a theoretical model that emphasizes the processes of impact generation rather than the impact itself, and to provide empirical evidence that uncovers universal patterns while highlighting disciplinary differences, given the substantial disciplinary variations in research impact (Oancea, 2013; Sivertsen & Meijer, 2020). By doing so, we seek to inform how research produces impact beyond academia, how the societal value of scientific research can be enhanced, and how such impact can be more effectively evaluated.

To achieve these objectives, this study analyzes REF impact cases to address two questions: (1) As reflected in a certain scale of real-world cases, what are the pathways as scientific research generates impact beyond academia? (2) How do the pathways differ among disciplines? The grounded theory is employed to construct the model of impact pathways, complemented by detailed case studies for further illustration. It should be noted that the genre of case studies for the REF requires the documentation of research pathways, beneficiaries, and outcomes, thereby reflecting a linear approach to tracing the generation of impact (Sivertsen & Meijer, 2020). Still, this source of data allows us to construct a more refined and practically relevant impact pathway model, and, to a certain extent, to provide a process-oriented and multidisciplinary panorama.

Literature review

From outcome-oriented to process-oriented impact evaluation

Outcome-oriented evaluation emphasizes the scope, domain, and magnitude of impact. For example, Terämä et al. (2016) used a text mining technique to identify how impact is interpreted in REF impact case studies and found that institutions present a diverse interpretation of impact, ranging from commercial applications to public and cultural engagement activities, with more broad-based institutions depicting a greater variety of impacts. Zheng et al. (2021) identified three emerging impact types documented in case studies submitted to impact evaluation groups in Australia (Engagement and Impact Assessment) and the UK (Research Excellence Framework), which extend existing frameworks by recognizing new opportunities, prolonging usage, and enhancing user experience. Moreover, scholars applying quantitative analysis have been actively seeking measurements for assessing the level of societal impact (Bornmann, 2013), with altmetrics representing a notable approach (Williams, 2017). Nevertheless, an outcome-oriented perspective may distort institutional priorities and practices, ultimately producing suboptimal outcomes for intended beneficiaries (Lowe, 2013).

By contrast, the process approach, which emphasizes the interactions among different stakeholders throughout the impact generation process, is considered the success key to reinforce research impact and guide knowledge development along constructive trajectories (Spaapen & van Drooge, 2011; Razmgir et al., 2021). Effective incentivization requires a shift away from ex post, outcomes-based evaluation, towards ex ante considerations of process (Upton et al., 2014), which is crucial for clarifying why the impacts occur, thereby enhancing the multifaceted value of scientific research and facilitating more reasonable assessments. While the process approach is a more effective driver to lead research towards impact, outcome-based approaches remain dominant in existing studies (Upton et al., 2014). Against this backdrop, this study will adopt a process-oriented perspective, hoping to contribute to the deeper understanding of impact pathways.

Linear and interactive paradigms on impact pathways

The impact model has been found since the 1970s in varying forms in evaluation research under the name “logic model”. The first publication that used the term “logic model” is usually cited as Evaluation: Promise and Performance by Joseph S. Wholey (1979). Logic models describe the logical linkages among program resources, activities, outputs, customers reached, as well as short, intermediate, and longer-term outcomes. With the intensified results-oriented management and non-profit organizations’ increased accountability, logic models have evolved into an essential tool for telling the programs performance story in theory-based evaluation (McLaughlin & Jordan, 1999). For example, an array of logic models following the steps of resources/inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact, has been adopted by W.K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) to enhance the ability to identify outcomes and anticipate ways to measure them, providing all program participants with a clear map of the road ahead. The logic model represents an early linear way of thinking.

Traditionally, impact assessments have been occupied primarily with end results conceptualized as the observable “effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia”, as stated in the guidelines for impact cases provided by the UK REF. Many evaluators and evaluation frameworks attempt to break down and attribute multiple activities and outputs to an observable and demonstrable change, rather than exploring the “why” and “how” of impact (Budtz Pedersen & Hvidtfeldt, 2023). A representative example is the 4D (Design – Deliver – Disseminate – Demonstrate) model (Dwivedi et al., 2024), which has been proposed to provide a structured approach for academia to consciously align research endeavors with practice. According to this model, designing research with practical impact in mind, delivering clear and accessible findings, disseminating insights beyond academic circles, and demonstrating tangible benefits to practice, are crucial steps towards maximizing the societal and practical relevance of academic research. Similarly for practical use, University College Dublin has established a research impact toolkit (https://www.ucd.ie/impacttoolkit/), which traces research over time, distinguishing between five different stages on the pathway to impact – inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts. This toolkit also reflects a typical linear model.

However, there is growing recognition that research does not create impact solely through causal pathways. Instead, research is exchanged both directly and indirectly among a diverse range of academic and non-academic institutions, contributing to the generation of productive knowledge (Spaapen & van Drooge, 2011). Developed by Buxton and Hanney in 1996, the Payback Framework stands as the most widely used approach to measure research impact, also with a typical interactive framework (Buxton & Hanney, 1996). It consists of a logic model of seven stages of research from conceptualization to impact, five categories to classify the paybacks, two interfaces for interaction between researchers and potential users of research, as well as various feedback loops connecting the stages. While this framework was originally developed to examine the “impact” or “payback” of healthcare research, it has subsequently been adapted to assess the impact of research in many other areas (Donovan & Hanney, 2011; Hanney et al., 2004). However, potential limitations of the Payback Framework lie in that applying the framework through case studies is labor intensive, and the framework is generally project-focused and less able to explore the impact of the sum total of activities of a research group that has attracted funding from a number of sources (Greenhalgh et al., 2016). Adapted from the Payback Framework, the CAHS (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences) Framework (2009) has been constructed as a more “systems approach” that takes greater account of the various non-linear influences at play in contemporary health research systems. Other interactive frameworks include the EU-funded SIAMPI (Social Impact Assessment Methods through the study of Productive Interactions) Framework (Spaapen & van Drooge, 2011), the Research Contribution Framework (Morton, 2015), and ASIRPA (Joly et al., 2015).

Considering both the advanced nature of the interactive paradigm at the conceptual level and the operability of the linear paradigm at the practical level, our study constructs a finer-grained linear model based on available data, incorporating interactive elements. The resulting model is empirically supported, while also responding to theoretical considerations and contributing to their development. It can be used to enhance the efficacy of grant management practices and facilitate the understanding of the mechanism of impact generation.

Empirical evidence on pathways to impact beyond academia

Mixed-method approaches have proven effective in capturing non-academic impacts and elucidating the processes through which they arise (Meagher et al., 2008). Based on REF impact cases, Biri et al. (2014) quantitatively analyzed different impact types, beneficiaries, and pathways to impact, while Stevenson et al. (2023) took a further step to trace the disciplinary changes from underpinning research to the resulting impacts. Rossi et al. (2017) demonstrate through interviews that impact is co-produced rather than transferred, emerging through sustained interactions, serendipitous ripple effects, and long-term processes. However, these efforts only involve quantitative or qualitative descriptions and have not yet advanced to theoretical depth or developed a systematic model.

It is widely acknowledged that theory-based approaches, which map causal chains from inputs to outcomes and emphasize contribution over attribution, offer explanatory power for understanding why impacts occur (Morton, 2015; Morton, 2012; White, 2009). However, such approaches have yielded limited empirical validation. D’Este et al. (2018) proposed an analytical and operational framework that incorporates individual, organizational, and process-context factors to explain distinct configurations of scientific and societal impacts, but their work remains conceptual and lacks empirical testing. Molas-Gallart et al. (2000) proposed a framework interconnecting research outputs, diffusion channels, and forms of impact, operationalized in a pilot study of the ESRC AIDS Program, yet lack of validation across broader samples. Molas-Gallart and Tang (2011) applied the SIAMPI approach to trace productive interactions in social science research based on interview data, but their contribution offered limited theoretical novelty.

To summarize, while existing research has significantly advanced our understanding of the pathways through which scientific research generates impact beyond academia, it remains constrained by the lack of systematic frameworks grounded in empirical data, as well as by the scarcity of quantitative analyses and cross-domain comparisons based on multiple real-world cases. Our study thus aims to construct a stratified and hierarchical model of impact generation that integrates theoretical and empirical perspectives, thereby advancing both knowledge and practical assessments.

Methodology

Data

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the UK’s system for assessing the quality of research in higher education institutions (HEIs), the outcomes of which are used to inform the allocation of public funding for universities’ research (UKRI, 2024). Established in 2014 as the successor to the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), which served as the primary method for research evaluation in the UK from 1986 to 2008 (Sousa & Brennan, 2014), the REF has been conducted periodically, most recently in 2021, with the next exercise scheduled for 2029. Notably, REF is the first national assessment in the world to formally evaluate the impact of research beyond academia (UKRI, 2022).

The REF is a process of expert review, carried out by expert panels for each of the 34 subject-based units of assessment (UoAs). For each institution, three distinct elements are assessed – the quality of outputs, their impact beyond academia, and the environment that supports research. Among them, the impact is assessed based on impact case studies submitted by HEIs that demonstrate the impacts their research has produced beyond academia. According to the template and guidance (REF 2021, 2020), each case study should include five parts of contents in its main body – summary of the impact, underpinning research, references to the research, details of the impact, and sources to corroborate the impact. In REF 2021, a total of 6,781 impact case studies were submitted (REF, 2022).

The REF has inspired several other countries in the evaluation of societal impact. The data it provides are highly authoritative and reliable, and the case materials it offers are well-structured, richly detailed, and span multiple fields. These features make it a valuable source of evidence for understanding the pathways through which scientific research generates impact beyond academia. Nevertheless, given the geographical limitations of the dataset, caution is warranted when applying the empirical insights of this study to research evaluation and decision-making support in broader national and regional contexts, where the research cultures and policies vary a lot.

Based on data obtained from the impact case study database of REF 2021 (https://results2021.ref.ac.uk/impact), this study identifies key elements in the pathway of scientific research generating impact beyond academia and further constructs the theoretical model and conducts cross-disciplinary comparison. It is important to note that, given the REF’s objective of serving institutional assessments and the data collection methods for reporting extraordinary impacts and the underpinning research, the model constructed based on REF cases is, to some extent, a linear perspective. This may introduce issues related to causality, attribution, internationality, and time scale (Sivertsen & Meijer, 2020). Nevertheless, it provides practical evidence from a certain angle for a better understanding of the pathway of scientific research generating impact beyond academia.

Since one of the main objectives of this study is to compare the differences in the impact pathway across various disciplinary fields, 50 cases selected from each of four representative UoAs – Clinical Medicine (UoA 1), Mathematical Sciences (UoA 10), Computer Science and Informatics (UoA 11), and Business and Management Studies (UoA 17) – are used for analysis. These UoAs cover natural and social sciences, basic and applied sciences, as well as physical and life sciences. Due to the varying total number of cases across the four UoAs (respectively 254, 176, 271 and 504), and their relatively large volume for manual reading, it is necessary to establish specific rules for case selection:

To construct a robust theoretical model, it is imperative that the case data exhibit high overall quality and comparability. This study firstly selects institutions of similarly high research caliber and then draws cases within these institutions. To be more specific, in REF 2021, each submission is assigned with an overall quality profile level (4-star, 3-star, 2-star and 1-star). The quality of 4-star cases is world-leading in terms of originality, significance, and rigor (REF, 2022). For each UoA, institutions that meet the following criteria are selected: the overall quality profile level of more than 50% of their submissions is 4-star, indicating these institutions generally exhibit high research standards in their respective fields. Focusing on cases submitted by these institutions, there are 117, 56, 82 and 91 cases in each UoA. Subsequently, we randomly sample cases from each institution to reach 50 cases per UoA. This methodology combines stratified and random sampling techniques, ensuring that the 200 selected cases for analysis are both manageable in scale and sufficiently representative.

Method

To examine the diverse impacts of scientific research, existing studies have proposed five types of impact evaluation design for various aims and context – experimental and statistical methods, textual, oral and arts-based methods, systems analysis methods, indicator-based approaches, and evidence synthesis approaches (Reed et al., 2021). This study employs a text-based approach based on grounded theory, complemented by descriptive statistical methods.

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that seeks to develop theories that are grounded in data systematically gathered and analyzed (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which is useful in developing context-based, process-oriented descriptions and explanations of phenomena (He et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). This study examines the generation of research impact beyond academia, presenting an exemplary application of grounded theory. When operationalizing the theory, the joint interaction between data collection and analysis to achieve iterative conceptualization is fundamental (Urquhart et al., 2010). Through multiple rounds of data supplementation, concept refinement, and comparative analysis, the three-step coding process – open coding, axial coding, and selective coding – has been completed.

In specific, open coding involves breaking down raw data to define concepts and refine their meanings, thereby categorizing the original concepts. In this study, 43 categories were extracted from the original impact case texts. Axial coding aims to further reveal the internal logical relationships between concepts, such as causal relationships, sequential relationships, and similarities. Based on the 43 categories, this study extracted 10 main categories. Selective coding involves organizing and refining the main categories to identify core categories, establish connections between core and main categories, and construct a theoretical explanation of these relationships. This study ultimately identified 6 core categories. The categories, main categories, core categories and their interrelations are detailed in Table 1.

During the coding process, a theoretical saturation test was conducted to determine whether further data collection and analysis were necessary (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Grounded theory does not prescribe a specific sample size or proportion for this test. Following prior studies (He et al., 2023; Rowlands et al., 2016), the sample size for the theoretical saturation test in this study was set at one-fifth. For each UoA, 40 cases were randomly selected for coding, while 10 additional cases were reserved for the saturation test. After completing the three-step coding of the initial 40 cases, the remaining 10 were analyzed in the same manner. No new essential categories or relationships emerged, indicating that theoretical saturation had been achieved and that the established model was reliable.

It is important to clarify that a single case may be classified under one or more categories within each main category. Consequently, in the following analysis, the cumulative proportions for each category in a certain main category are not sum to one. Rather, the emphasis is placed on the quantity of cases associated with each category for each UoA, which is comparable due to the same total number of cases.

We would also like to emphasize that, in order to enhance the reliability of the manual coding results, we adopted a three-step strategy. Firstly, we selected one representative case characterized by highly rich content and complex impact pathways from each of the four UoAs. These cases were jointly discussed by the research team to determine how to extract categories and to reach consensus, while also clarifying discipline-specific considerations. Secondly, we employed a double back-to-back coding procedure, and checked the consistency of the binary (0–1) coding results across categories at the case levelFootnote 1. Following established practices (Díaz et al., 2023; Douglas et al., 2022), two co-authors with domain expertise independently coded the texts in sequence. During this process, each coder could refer to the categories identified by the other, and through discussion, revision, and integration, they ultimately reached consensus. However, the coders are blinded to each other’s coding decisions, thereby ensuring the independence of judgments regarding whether a given case contained a particular category. To assess inter-coder reliability, we adopted the widely used Cohen’s Kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960; Nili et al., 2020). The detailed results of this reliability test are reported in Table 2, showing an overall Kappa value of 0.868, which indicates that the coding results are reliableFootnote 2. Thirdly, the statistical analyses based on the coded data also produced interpretable results (see Section “Results”), which indirectly demonstrates the overall robustness of the coding process.

After completing the coding work, we proceed with model construction and employ descriptive statistical methods for comparative analysis across disciplines, followed by case studies for in-depth interpretation.

Results

Pathway of scientific research generating impact beyond academia

Figure 1 presents the model constructed from the analysis of 200 pieces of REF impact cases based on the three-step coding process of grounded theory. The model delineates the progression of impact through incubation, cultivation, and formation periods. Three periods involve stages including problem identification, research conduct, output production, output utilization, and impact formation. Furthermore, the interaction with relevant stakeholders can influence these processes.

Identifying problems

Regarding problem identification, we focus on both motivation and target audience. The former involves four specific types – scientific interest, value realization, commercial benefit, and political demand. The latter involves four groups – academia, public, industry, and government.

Motivation is the process that drives, selects and directs goals and behaviors (Dweck et al., 2023). The rationale behind conducting a study, to a certain extent, determines the potential impact it can achieve. According to existing theories (Gerhart & Fang, 2015), motivation can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic types. Intrinsic motivation, characterized by higher autonomy, is generally of higher quality than extrinsic motivation, which is influenced by external factors. In this study, scientific interest and value realization can be regarded as intrinsic motivations, while commercial benefit and political demand can be categorized as extrinsic motivations. In the context of investigating research impact beyond academia, we aim to explore the roles of different types of motivations.

Target audience consists of the group originally intended to be served by the research, which to a certain extent determines the ultimate impact on the covered population. It is necessary to clarify that the four categories of motivations and target audiences do not correspond directly. For example, a study aimed at addressing fundamental scientific issues pertinent to the development of a particular industry may be driven by scientific curiosity, yet its beneficiaries lie within the industry.

Conducting research

Regarding research conduct, we mainly distinguish three types of research approaches. Theoretical research is a logical exploration of a system of beliefs and assumptions, encompassing theory construction, literature review, hypothesis generation, etc. Laboratory research can be understood as research in the lab in this study, not only involving using specialized equipment, instruments, and techniques to observe and manipulate variables under controlled conditions but also including quantitative or qualitative analysis and conclusion formulation based on empirical data. Field research is a type of context research that takes place in the user’s natural environment as opposed to a lab or an orchestrated setting, especially emphasizing the interaction with entities external to the research team. Conducting research in different ways leads to varying degrees of engagement with diverse aspects of society during the research process, thereby influencing the formation of impact beyond academia.

Producing outcomes

Regarding output production, we focus on both the form of research outcomes and their research level. The former involves articles, patents, standards, books, products, and reports. The latter involves basic research and applied research.

The form of outcomes serves as the carrier for research to generate and amplify their impact. Different disciplines exhibit varying forms of outcomes. For instance, research in humanities and social sciences primarily produces articles and monographs, whereas research in engineering and technology areas primarily produce patents and products. The dissemination efficacy outside academia of these diverse forms of outcomes also varies. For instance, reports may garner greater attention and references from policy and management departments.

The level of research reflects the degree of its foundational or applied nature. For a long time, people have been accustomed to dichotomizing scientific research into basic research and applied research. The conceptual connotations of these terms are relatively complex and have continually evolved with the times, attracting extensive debate and discussion among scholars (Schauz, 2014). In this study, we adopt these terms primarily to distinguish between two types of research: one that provides foundational support for practical applications and one that directly serves practical application scenarios. Research leaning towards the applied end of the spectrum is more oriented towards practical production and life, and thus might be more likely to produce impact beyond academia compared to basic research.

Utilizing outcomes

Regarding output utilization, we mainly distinguish five types of influence approaches. In some cases, the direct utilization of research outcomes can generate immediate impact, such as designing a treatment protocol that healthcare professionals adopt directly, thereby producing health impact. However, more often, research outcomes require mediated translation to exert influence beyond academia. Academic communication refers to the dissemination of research outcomes through channels such as academic lectures, conferences, workshops, etc. Commercial translation involves expanding the impact of research outcomes through technological applications, product upgrades, business operations, etc. Public dissemination leverages the power of the general public to spread research outcomes, through channels such as social media, public debate, etc. Decision-making support aims to generate or expand the impact of research outcomes by supporting the formulation and adjustment of policies. These various approaches are beneficial for promoting the impact of research outcomes across different scenarios and on various scales.

Generating impact

Regarding impact generation, we mainly focus on the type and the scope of impact. The former involves political, legal, technological, cultural, societal, economic, health, and environmental types. The latter involves local, national, and international scopes.

The type of impact defines the area that the research exert influence on, which is related to the established objectives of research. Taking the science-policy interaction as an instance (Cao et al., 2025), a study aimed at supporting policy formulation might be more likely to yield policy impacts. Simultaneously, the type of impact is also shaped by uncertainties. For example, the development of a patent intended to foster technological innovation may inadvertently alter public perceptions and lead to societal impacts. The choice of examining the type of impact rather than more specific content-level characteristics is primarily guided by the theoretical model constructed in this study, aiming for comprehensive and concise summarization, and facilitating cross-disciplinary comparisons. The categorization of impacts by domains of action is already well-established in the existing literature (Kuruvilla et al., 2006).

The scope of impact defines the broadness of the population affected by the research outcomes, which serves as a useful lens for examining the incrementally, multidimensional, and interdependent nature of impacts across micro, meso, and macro levels within emerging and complex environments (Harper et al., 2020). If the research is directed towards a specific entity, such as a company, and the outcomes directly affect this entity, it will be regarded as producing a local impact. If the research is not aimed at a particular target and addresses broader issues, or if the research initially targeting a specific entity subsequently influences broader national or international contexts, it will be considered to produce a national or international impact.

Interacting with stakeholders

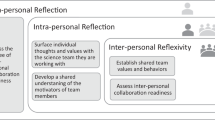

Regarding the interaction with stakeholders, we mainly focus on the collaborative research during the process of research conduct and the enhanced utilization during the process of output utilization. The former involves academic interaction, public engagement, industry participation, and governmental support. The latter involves academic rewards, media coverage, industry recognition, and authoritative adoption.

Interacting with relevant stakeholders during the research process facilitates early recognition and analysis of their actual needs, thereby enabling research outcomes to better meet societal demands. It also promotes stakeholders’ deeper understanding of the research process, earlier adoption of research outcomes, and more effective dissemination of the impacts of the outcomes. For instance, continuous engagement and interaction with the public during the research process can facilitate earlier dissemination and impact of research outcomes among the public.

During the process of utilizing research outcomes, the involvement of external entities can enhance their impact and facilitate further dissemination. For instance, if a medical or health-related paper receives coverage from authoritative media outlets, it may significantly increase public exposure to relevant information and thereby promote health literacy.

It should be noted that, unlike the core categories discussed earlier, interaction with relevant stakeholders does not correspond to a specific stage in the linear progression of scientific research and thus does not lie on the main path; rather, it is considered as a contributing factor within the model. This, however, does not diminish its significance. By contrast, this interaction process exemplifies a non-linear conception of the pathway through which impact emerges, reflecting a shift from first- and second-generation cultures that treat impact as a top-down, add-on or two-way exercise in “research impact literacy” towards third-generation cultures that embed researchers in knowledge ecosystem, emphasize systems thinking, and pursue “just transformations” via co-learning, co-design, and context-sensitive “best fit” solutions rather than universal “best practice” (Reed & Rudman, 2023). This core category assumes a guiding and directly facilitative role in the formation of research impact beyond academia.

Differences of the pathways among different disciplines

What kinds of impacts does research across various fields generate beyond academia?

Given that our research focus is the impact beyond academia, our primary comparison is on the characteristics of the impact generated by scientific research in different fields.

Figure 2 illustrates the number of cases in each UoA across various impact types. It can be observed that a significant number of cases in all four UoAs result in economic impact, while cases generating legal, cultural, and environmental impacts are relatively fewer. In comparison, research in the field of clinical medicine predominantly results in political and health impacts; research related to mathematics or computer and information science tends to yield technological impacts; and research pertaining to business and management is more likely to produce societal impacts.

Apart from the type of impact, variations are also observed in terms of the scope of impact. Compared to local and national impacts, more cases have generated international impacts. The proportions of cases generating three different scopes of impact in the total samples are respectively 25%, 58.5% and 80.5%. Especially, the proportions of cases generating international impacts in the fields of clinical medicine as well as computer science and informatics are particularly prominent, accounting for 96% and 90% respectively. In actual, medical research is fundamentally designed to benefit all of humanity, rather than being confined to specific geographic populations. This principle is particularly evident in the United Kingdom, which has shown a significant commitment to addressing diseases prevalent in developing countries (Zhang et al., 2020). Likewise, research in engineering and technology frequently harnesses the capabilities of industries, particularly large multinational corporations, to enhance the global impact of their findings.

What are the underlying motivations that drive the generation of impact in these fields?

Given the significant impact of research, its trajectory is largely established during the initial stages. Consequently, we aim to focus specifically on the driving factors of scientific research within different fields.

Figure 3 illustrates the number of cases in each UoA across various motivations. In the field of clinical medicine, value realization is the primary motivation, followed by scientific interest. Actually, medical research is often conducted with the aim of improving human health and enhancing the well-being of the population, which aligns with our common understanding. In the field of mathematics, scientific interest is the primary motivation, which aligns with the characteristics of foundational disciplines that typically require a curiosity-driven motivation. In the field of computer and information sciences, the distribution of different types of motivations is relatively balanced, with the phenomenon of industry-driven interests being more pronounced. In the field of business management, political demand is the primary motivation, which reflects the social scientists generally engage in more direct and frequent interactions with policymakers compared to natural scientists.

Apart from the motivation, variations are also observed in terms of the target audience. Overall, the proportions of cases targeted at academia, the public, industry, and government are respectively 9.5%, 35.5%, 55.5% and 27.5%. Focusing on different fields, public-oriented cases are prominent in the medical field, accounting for a significant 76%. In the fields of mathematics as well as computer and information sciences, industry-oriented cases are the most prevalent, with proportions of 58% and 66% respectively. In the field of business management, government-oriented cases are relatively notable, constituting 40% of the total.

Do the pathways through which impact is generated vary among different fields?

This part of analysis further integrates the research development and dissemination process, and compares the varieties in impact pathways across different fields by analyzing the flow of various elements within the pathways, as shown in Fig. 4.

Our first observation is that compared to other UoAs, UoA 1 features a greater number of cases where the research is conducted through field research, primarily involving clinical trials conducted in the target population’s locale. This is closely related to the relatively comprehensive research chain in the medical field, which encompasses the entire process from basic research to applied research and clinical practice. To some extent, this approach effectively promotes the utilization and dissemination of research findings, thereby enhancing the impact of the research. In addition, what has surprised us is the crucial position of decision-making support in the process of utilizing outcomes. While medical research findings can be directly applied to make an impact for certain, given the critical importance of human health and life, their deeper and more far-reaching influence often stems from informing the establishment of medical guidelines, which in turn steer medical practice.

Regarding the other three UoAs, each possesses its own distinct characteristics as well. Because mathematics is a more fundamental discipline, it often integrates with application scenarios from various fields to conduct research and generate impact. Consequently, we observe that UoA 10 tends to engage in more basic research, and the approaches to utilizing research outcomes are more diverse. Simultaneously, due to the engineering and technical application orientation of computer and information sciences, there is a closer connection with industry. As a result, we observe that cases in UoA 11 produce more patents, products, and (industrial) standards, and it exerts its influence more through commercial translation. Additionally, the field of business management, which falls under the broader category of social sciences, exhibits its unique features. Most notably, the output from UoA 17 includes a remarkable number of books and reports. The former is marked by greater public appeal, systematic approach, and longer-term value, making it easier to disseminate through academic exchanges and public communication channels. The latter demonstrates higher levels of professionalism, dissemination potential and guiding value, effectively supporting decision-making processes.

To what extent do diverse stakeholders contribute to the process of impact generation?

It has been observed that various entities, including the government, industry, the public, and academia, play crucial roles in generating impact beyond academia. The last analysis of this section compares the involvement of diverse stakeholders in the process of conducting research and utilizing outcomes among different fields, as shown in Fig. 5.

As observed from the subplot (a), among four UoAs, the proportions of cases involving academic interaction and industry participation are both prominent. In the field of clinical medicine and mathematics, there are relatively more cases pertaining to public engagement, which may be attributed to the extended research translation chain and the relatively indirect impact characteristic of these two fields, thereby necessitating more non-targeted support from civil society. Conversely, in the field of computer and information science, as well as business and management, there are relatively more cases receiving governmental support.

As observed from the subplot (b), for the four UoAs, cases involving media coverage are all relatively few. It is understandable that there remains a certain distance between academia and the media. The media are not typically the primary audience for academic research and their engagement with scholarly work is often limited. Zooming into different specific fields, the impact of research outcomes is primarily expanded through authoritative adoption in the medical field, whereas in the other three fields, the impact is more commonly extended through industry recognition.

Case studies for a better understanding of the pathways

Building on the previously presented descriptive statistical analysis, this section introduces four cases from four distinct UoAs, as shown in Fig. 6. The objective is to visually elucidate the pathways through which research impact is generated beyond academia, thereby deepening the comprehension of this intricate process and its variations across different disciplines.

The first case comes from the field of clinical medicine. In this case, researchers aimed to reduce HIV-associated mortality in Africa and other low-resource settings and have developed approaches to address cryptococcal meningitis (CM) in HIV+ people. Their research outcomes have been incorporated into World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and led to changes in clinical practice in Africa, including stimulating investment, enabling the training of health care staff, saving lives, etc. This case exemplifies an impact pathway characterized by value-driven, multi-stakeholder participation, and diverse impacts induced by decision support for international influential institutions.

The second case comes from the field of mathematics. In this case, researchers aimed to provide high-performance optimization software for Format Solutions, the world’s leading supplier of software for food formulation, and have focused on addressing large-scale linear programming (LP) problems and developed two optimization software. Their research outcomes have been applied to industrial practice and supported the technological innovation and strategic development of the enterprise. This case exemplifies an impact pathway characterized by demand-driven, multi-type outputs, and profound impacts induced by directly serving the specific target.

The third case comes from the field of computer science and informatics. In this case, researchers have identified the potential of temporal planning to provide strategic control for automated drilling systems. They were deeply involved in the technological practice of Schlumberger, a Fortune 500 Oil & Gas Services Company, engaging in product development, testing and deployment. Their research outcomes have brought the company improvements in efficiency, consistency, and safety, along with a competitive edge. This case exemplifies a translation pathway from academic research to industrial application, especially featuring the bi-directional learning between academia and industry (Mäkinen & Sapir, 2023).

The fourth case comes from the field of business and management. In this case, researchers aimed to address the skills gap faced with organizations, which might limit their ability to flourish and restrain their employees’ access to rewarding careers. Researchers have investigated two issues concerning contemporary apprenticeship training – the capacity of new apprenticeship programs to meet emerging skills needs, and the benefits of cross-national exchanges of good practices to inform the implementation of apprenticeship programs. Their research outcomes have been instrumental in persuading policy-makers in the UK to create a new and unique apprenticeship program for technicians in the life sciences and the biotech sector and influenced policy-makers and industrial organizations in the US to support new networks to help small and medium-sized enterprises train apprentices. This case exemplifies an impact pathway that closely aligns with the national and societal needs, to identify problems, conduct research, and generate impact, demonstrating the distinct characteristics of social science research.

Comparing these four cases reveals that research cycles in the natural sciences are considerably longer than those in the social sciences. In both fundamental and applied fields, research encompasses a complex and multi-layered progression, ranging from basic, applied, and translational phases. This extended and intricate process enables natural science research, despite its initial indirect societal connections – whether in physical or life sciences – to engage continuously with diverse stakeholders and progressively address real-world needs, thereby generating substantial impact beyond academia. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the boundaries of scientific research are not confined to specific scenarios. Social sciences are not solely associated with public and policy domains, nor are natural sciences exclusively linked to technology and industry. Both natural and social sciences demonstrate a convergence of disciplines, contexts, and audiences in the process of generating impact beyond academia. For example, medical research outcomes necessitate policy support to effectively contribute to public health, while research in economic management can significantly benefit industries driven by economic interests. Similarly, computer engineering research thrives on the exchange of knowledge between academia and industry, whereas mathematics research holds broader potential for generating and applying results.

In summary, for scientific research across four UoAs, the generation of impact beyond academia follows a generally consistent logic, though specific pathways may vary due to disciplinary characteristics. This section offers a more intuitive explanation through concrete case studies. Regardless of the research field, researchers have opportunities to create impact beyond academia. However, it is essential to recognize the differences among fields to reasonably evaluate the realistic contributions of scientific research.

Conclusion and discussion

Main findings

Based on the impact cases provided by the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF 2021), as well as mixed methods incorporating grounded theory, statistical analysis and case studies, this study constructs a theoretical model outlining the pathway through which scientific research generate impact beyond the academic community. A comparative analysis across different disciplines is conducted, with specific cases provided to illustrate the findings.

At the theoretical level, the proposed model not only involves various kinds of research contributions – outputs, outcomes and realized benefits (Belcher & Halliwell, 2021), but also traces antecedent steps such as research motivation and research approach within the linear process of knowledge production (Macnaghten, 2022), while emphasizing interactions with different stakeholders that define the trajectory of impact and introduce nonlinear dynamics into impact generation (Pappas et al., 2023). Our model inherits the linear and nonlinear perspectives of existing theoretical models (Sivertsen & Meijer, 2024), while further integrating and formalizing the fragmented elements identified in real-world cases (Biri et al., 2014; Rossi et al., 2017; Stevenson et al., 2023). In doing so, it extends existing frameworks by combining their conceptual structures with robust empirical evidence, thereby achieving a transition from theoretical discussion and isolated case illustrations to a systematic revelation of underlying patterns.

At the empirical level, our findings highlight the presence of disciplinary variations and indicate that scientific research can produce impacts beyond academia to varying extents and through diverse pathways. As examples, medical research tends to be value-driven and generate global health and policy impacts; mathematics achieves translation mainly through cross-disciplinary applications; computer and information sciences produce technological and international impacts via industrial linkages; and management science generates societal impacts by responding to social and policy demands. These patterns, validated through a substantial set of real-world cases, provide more robust evidence than prior interpretations based on limited case studies (Oancea, 2013). Such insights are critical for research evaluation practices, as they provide clarity about the entities and dimensions to be assessed, and support the implementation of characteristics-based evaluation.

Practical implications

This study primarily contributes to practice by clarifying the kinds of societal impacts and by elucidating the mechanisms through which such impacts are generated. The findings have several implications for different stakeholders.

For research evaluators, it is crucial to recognize that different types of research follow distinct pathways toward impact beyond academia and produce varied outcomes. Evaluation should therefore adopt a differentiated and tiered approach, acknowledging that not all research is expected to achieve societal impact. However, where appropriate, societal impact should be incorporated into assessment frameworks, with explicit consideration of long-term, unintended, and even negative effects (Derrick et al., 2018). While such an approach broadens the recognition of diverse forms of research value, it also confronts the enduring challenge of developing reliable and meaningful assessment strategies in practice (Bornmann, 2012; Gerke et al., (2023); Sørensen et al., 2022).

For individual researchers, it is important to understand that societal impact often emerges gradually, interactively, and varies significantly across disciplines. There should be no undue pressure to pursue or rapidly achieve societal impact. Instead, scholars should identify approaches that align with their own research practices and intellectual goals and strengthen the meaningful involvement of stakeholders and end-users throughout the project lifespan (Aiello et al., 2021).

For societal actors, recognizing their roles within the pathways of research generating impact beyond academia enables their more active and effective engagement in the scientific process. Such engagement may take diverse forms, including financial support, collaborative research, promotional activities, or other forms of involvement, and contributes to ensuring that research outcomes are more closely aligned with societal needs. In this regard, stakeholder engagement and non-academic dissemination constitute critical mechanisms through which scientific research can produce societal impact and address pressing societal challenges (Dotti & Walczyk, 2022).

For management bodies, attention should be directed toward the establishment of platforms and channels that facilitate interaction among various actors, such as the participatory knowledge infrastructure described by Oortwijn et al. (2024) and the societal interaction plan described by Pulkkinen et al. (2024). By implementing well-designed incentive mechanisms and funding systems, and fostering conditions conducive to transdisciplinary collaboration, mutual trust, and sustained engagement, these bodies can enhance the interface between academia and society. Such efforts are likely to increase the societal relevance and impact of research throughout its full cycle, encompassing problem identification, knowledge production, and the dissemination and implementation of results.

Limitations and future work

We acknowledge several limitations that warrant further exploration and deepening:

Firstly, our analysis is based on key information and narrative chains extracted from impact case texts submitted by individuals, which are institutionally curated, selective, and often self-promotional. Consequently, these texts may overrepresent “success stories” while downplaying longer-term, latent, unintended, or negative impacts (e.g., harmful technologies, inequitable policies) that are challenging to capture through self-reported data (Then et al., 2017). Nonetheless, our case texts provide a sufficiently detailed account of the processes generating impact beyond academia. It should be noted, however, that the model proposed in this study remains partially linear, whereas real-world impacts frequently exhibit recursive, chaotic, or emergent dynamics.

Secondly, the study is constrained by its reliance on manual annotation. Although a dual-coder and back-to-back procedure was employed to enhance reliability, a certain degree of subjectivity is inevitable, and the coding results might be influenced by individual perceptions. Moreover, the labor-intensive nature of manual annotation limits the sample size. As robust and sophisticated annotation procedures are time-consuming and not always feasible or affordable (Greenhalgh et al., 2016), future research could benefit from semi-automated methods to identify statistically significant patterns and enable more comprehensive comparative analyses.

Lastly, a cautious interpretation of the research findings is necessary, as this study is based solely on institutions at specific levels within the UK higher education system, which may have a unique focus on the impact of scientific research beyond academia. However, a basis for mutual learning among countries is more in demand than a formulation of best practice (Sivertsen, 2017). The model and the associated patterns identified in our study are somewhat context-based and need to be validated with a broader sample.

In future research, we will seek to identify more diverse sources of impact case data, integrate a broader range of research samples, and develop more advanced coding techniques. These efforts will enable us to compare and validate the preliminary findings of this study across larger-scale datasets, extended temporal spans, a wider array of disciplines, and more varied evaluation contexts.

Data availability

Our data is obtained from the impact case study database of REF 2021 (https://results2021.ref.ac.uk/impact), which is open to the public. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

For our task, two strategies for assessing coding consistency were possible. The first involved sentence-level coding, where each individual case was segmented into sentences, and the coders’ agreement on the categorization of the same sentence was tested. The second involved case-level coding, where for each category, the coders’ annotations of the cases as a whole were compared. Considering that our coding required attention to the broader context of each case – for instance, a sentence mentioning a citation of a paper in a policy document alone does not indicate whether the researcher intended to highlight the role of policy agency in disseminating the impact of research outputs or the policy impact of research outputs themselves – we adopted the second strategy. Specifically, we conducted a binary (0–1) coding of whether each category was present in a given case and evaluated inter-coder agreement at the case level.

It can be observed that the Kappa values vary across categories as well as across units of assessment. Differences across categories primarily stem from the associated cognitive complexity. For example, determining what constitutes industry recognition is not as straightforward as identifying media coverage. Differences across units of assessment might be related to the characteristics of the research areas and the coders’ knowledge backgrounds. For example, mathematics is more inclined toward basic research, and the manifestations of its societal impact outside of the educational sector may be relatively obscure. Meanwhile, the coders possess greater expertise in computer science and information management, which may have facilitated the achievement of consensus in related areas.

References

Aiello E, Donovan C, Duque E et al. (2021) Effective strategies that enhance the social impact of social sciences and humanities research. Evid Policy 17(1):131–146

Panel on Return on Investment in Health Research (2009) Making an Impact: A Preferred Framework and Indicators to Measure Returns on Investment in Health Research. Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Belcher B, Halliwell J (2021) Conceptualizing the elements of research impact: towards semantic standards. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1):183

Biri D, Oliver K, Cooper A (2014) What is the impact of BEAMS research? An evaluation of REF impact case studies from UCL BEAMS. (STEaPP Working Paper). Department of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Public Policy, University College London, London, UK

Bornmann L (2012) Measuring the societal impact of research: research is less and less assessed on scientific impact alone—we should aim to quantify the increasingly important contributions of science to society. EMBO Rep. 13(8):673–676

Bornmann L (2013) What is societal impact of research and how can it be assessed? A literature survey. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 64(2):217–233

Budtz Pedersen D, Hvidtfeldt R (2023) The missing links of research impact. Res Eval 33:rvad011

Buxton M, Hanney S (1996) How can payback from health services research be assessed? J Health Serv Res Policy 1(1):35–43

Cao Z, Zhang L, Huang Y et al. (2025) How does scientific research influence policymaking? A study of four types of citation pathways between research articles and AI policy documents. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 76(10):1340–1356

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20(1):37–46

D’Este P, Ramos-Vielba I, Woolley R et al. (2018) How do researchers generate scientific and societal impacts? Toward an analytical and operational framework. Sci Public Policy 45(6):752–763

Derrick GE, Faria R, Benneworth P et al. (2018) Towards characterising negative impact: Introducing Grimpact. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Science and Technology Indicators: Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators in Transition (Vol. 2018-09-11, pp. 1199-1213). Leiden University, CWTS. http://hdl.handle.net/1887/65230

Díaz J, Pérez J, Gallardo C et al. (2023) Applying inter-rater reliability and agreement in collaborative grounded theory studies in software engineering. J Syst Softw 195:111520

Donovan C, Hanney S (2011) The ‘Payback Framework’ explained. Res Eval 20(3):181–183

Dotti NF, Walczyk J (2022) What is the societal impact of university research? A policy-oriented review to map approaches, identify monitoring methods and success factors. Eval Program Plan 95:102157

Douglas S, Merritt D, Roberts R et al. (2022) Systemic leadership development: impact on organizational effectiveness. Int J Organ Anal 30(2):568–588

Dweck CS, Dixon ML, Gross JJ (2023) What Is Motivation, Where Does It Come from, and How Does It Work? In Motivation Science: Controversies and Insights (pp. 0). Oxford University Press

Dwivedi YK, Jeyaraj A, Hughes L et al. (2024) "Real impact": Challenges and opportunities in bridging the gap between research and practice – Making a difference in industry, policy, and society. Int J Inf Manag 78:102750

Gerhart B, Fang M (2015) Pay, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, performance, and creativity in the workplace: Revisiting long-held beliefs. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 2(1):489–521

Gerke DM, Uude K, Kliewe T (2023) Co-creation and societal impact: Toward a generic framework for research impact assessment. Evaluation 29(4):489–508

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H et al. (1994) The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. SAGE, London

Glaser B, Strauss A (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, USA

Godin B (2006) The linear model of innovation: The historical construction of an analytical framework. Sci Technol Hum Values 31(6):639–667

Greenhalgh T, Raftery J, Hanney S et al. (2016) Research impact: a narrative review. BMC Med 14(1):78

Hanney SR, Grant J, Wooding S (2004) Proposed methods for reviewing the outcomes of health research: the impact of funding by the UK's `Arthritis Research Campaign'. Health Res Policy Syst 2(1):4

Harper LM, Maden M, Dickson R (2020) Across five levels: The evidence of impact model. Evaluation 26(3):350–366

He C, Xu J, Zhou L (2023) Understanding China’s construction of an academic integrity system: A grounded theory study on national-level policies. Learned Publ 36(2):217–238

Hessels LK, Van Lente H (2008) Re-thinking new knowledge production: A literature review and a research agenda. Res policy 37(4):740–760

Hill S (2016) Assessing (for) impact: Future assessment of the societal impact of research. Palgrave Commun 2(1):1–7

Joly PB, Gaunand A, Colinet L (2015) ASIRPA: A comprehensive theory-based approach to assessing the societal impacts of a research organization. Res Eval 24(4):440–453

Kellogg Foundation WK (2004) Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action: Logic model development guide. Author, Battle Creek, MI

Kuruvilla S, Mays N, Pleasant A et al. (2006) Describing the impact of health research: a Research Impact Framework. BMC Health Serv Res 6(1):134

Lowe T (2013) New development: The paradox of outcomes — the more we measure, the less we understand. Public Money Manag 33(3):213–216

Macnaghten P (2022) Models of science policy: from the linear model to responsible research and innovation. In The Responsibility of Science (pp. 93−106). Cham: Springer International Publishing

Mäkinen EI, Sapir A (2023) Making Sense of Science, University, and Industry: Sensemaking Narratives of Finnish and Israeli Scientists. Minerva 61(2):175–198

McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB (1999) Logic models: A tool for telling your programs performance story. Eval Program Plan 22(1):65–72

Meagher L, Lyall C, Nutley S (2008) Flows of knowledge, expertise and influence: A method for assessing policy and practice impacts from social science research. Res Eval 17(3):163–173

Molas-Gallart J, Tang P (2011) Tracing ‘productive interactions’ to identify social impacts: An example from the social sciences. Res Eval 20(3):219–226

Molas-Gallart J, Tang P, Morrow S (2000) Assessing the non-academic impact of grant-funded socio-economic research: Results from a pilot study Res Eval 9(3):171–182

Morton S (2015) Progressing research impact assessment: A ‘contributions’ approach. Res Eval 24(4):405–419

Morton SC (2012) Exploring and Assessing Social Research Impact: A Case Study of a Research Partnership’s Impacts. The University of Edinburgh, UK

Nili A, Tate M, Barros A et al. (2020) An approach for selecting and using a method of inter-coder reliability in information management research. Int J Inf Manag 54:102154

Oancea A (2013) Interpretations of Research Impact in Seven Disciplines. Eur Educ Res J 12(2):242–250

Oortwijn W, Reijmerink W, Bussemaker J (2024) How to strengthen societal impact of research and innovation? Lessons learned from an explanatory research-on-research study on participatory knowledge infrastructures funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Health Res Policy Syst 22(1):81

Pappas IO, Vassilakopoulou P, Kruse LC et al. (2023) Practicing effective stakeholder engagement for impactful research. IEEE Trans Technol Soc 4(3):248–254

Penfield T, Baker MJ, Scoble R et al. (2014) Assessment, evaluations, and definitions of research impact: A review. Res Eval 23(1):21–32

Pulkkinen K, Aarrevaara T, Rask M (2024) Societal interaction plans—A tool for enhancing societal engagement of strategic research in Finland. Res Eval 33:rvae002

Razmgir M, Panahi S, Ghalichi L et al. (2021) Exploring research impact models: A systematic scoping review. Res Eval 30(4):443–457

Reed MS, Rudman H (2023) Re-thinking research impact: Voice, context and power at the interface of science, policy and practice. Sustain Sci 18(2):967–981

Reed MS, Ferré M, Martin-Ortega J et al. (2021) Evaluating impact from research: A methodological framework. Res Policy 50(4):104147

REF (2022, 2022-05-12) Guide to the REF results. Retrieved 2024-07-31 from https://2021.ref.ac.uk/guidance-on-results/guidance-on-ref-2021-results/index.html

REF 2021 (2020) Guidance on submissions (2019/01). Retrieved 2024-08-15 from https://2021.ref.ac.uk/publications-and-reports/guidance-on-submissions-201901/index.html

Rossi F, Rosli A, Yip N (2017) Academic engagement as knowledge co-production and implications for impact: Evidence from Knowledge Transfer Partnerships. J Bus Res 80:1–9

Rowlands T, Waddell N, McKenna B (2016) Are We There Yet? A Technique to Determine Theoretical Saturation. J Comput Inf Syst 56(1):40–47

Schauz D (2014) What is Basic Research? Insights from Historical Semantics. Minerva 52(3):273–328

Sivertsen G (2017) Unique, but still best practice? The Research Excellence Framework (REF) from an international perspective. Palgrave Commun 3(1):1–6

Sivertsen G, Meijer I (2020) Normal versus extraordinary societal impact: How to understand, evaluate, and improve research activities in their relations to society? Res Eval 29(1):66–70

Sivertsen G, Meijer I (2024) Evaluating and Improving the Societal Impact of Research. In Challenges in Research Policy: Evidence-Based Policy Briefs with Recommendations (pp. 21-28). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland

Sørensen OH, Bjørner J, Holtermann A et al. (2022) Measuring societal impact of research—Developing and validating an impact instrument for occupational health and safety. Res Eval 31(1):118–131

Sousa SB, Brennan JL (2014) The UK Research Excellence Framework and the Transformation of Research Production. In C. Musselin & P. N. Teixeira (Eds.), Reforming Higher Education: Public Policy Design and Implementation (pp. 65-80). Springer Netherlands

Spaapen J, van Drooge L (2011) Introducing ‘productive interactions’ in social impact assessment. Res Eval 20(3):211–218

Stevenson C, Grant J, Szomszor M et al. (2023) Data enhancement and analysis of the REF 2021 Impact Case Studies. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Terämä E, Smallman M, Lock SJ et al. (2016) Beyond Academia – Interrogating Research Impact in the Research Excellence Framework. PLOS ONE 11(12):e0168533

Then V, Schober C, Rauscher O et al. (2017) How Are Impacts Identified? The Impact Model. In V. Then, C. Schober, O. Rauscher, & K. Kehl (Eds.), Social Return on Investment Analysis: Measuring the Impact of Social Investment (pp. 93-119). Springer International Publishing

UKRI (2022, 2022-03-31) How Research England supports research excellence. Retrieved 2025-09-18 from https://www.ukri.org/who-we-are/research-england/research-excellence/ref-impact/

UKRI (2024, 2024-04-08) How Research England supports research excellence. Retrieved 2024-07-31 from https://www.ukri.org/who-we-are/research-england/research-excellence/research-excellence-framework/

Upton S, Vallance P, Goddard J (2014) From outcomes to process: Evidence for a new approach to research impact assessment Res Eval 23(4):352–365

Urquhart C, Lehmann H, Myers MD (2010) Putting the ‘theory’ back into grounded theory: Guidelines for grounded theory studies in information systems. Inf Syst 20(4):357–381

White H (2009) Theory-based impact evaluation: Principles and practice. J Dev Effect 1(3):271–284

Wholey JS (1979) Evaluation: Promise and performance. Urban Institute, Washington, DC

Williams AE (2017) Altmetrics: An overview and evaluation. Online Inf Rev 41(3):311–317

Zhang L, Zhao W, Liu J et al. (2020) Do national funding organizations properly address the diseases with the highest burden?: Observations from China and the UK. Scientometrics 125(2):1733–1761

Zhang Z, Xie J, Xu X et al. (2023) Modeling the information behavior patterns of new graduate students in supervisor selection. Inf Process Manag 60(3):103342

Zheng H, Pee LG, Zhang D (2021) Societal impact of research: a text mining study of impact types. Scientometrics 126(9):7397–7417

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 72374160, L2424104), the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Grant No. WHXZ2022-02), the China Association for Science and Technology (Grant No. KXYJS2024016), and the National Laboratory Centre for Library and Information Science at Wuhan University. The authors also thank UK REF for providing data required for research purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZC and LZ; methodology: ZC; formal analysis: ZC, ZW, and CL; writing (original draft preparation): ZC; writing (review and editing): ZC, LZ, and GS; visualization: ZC; supervision: LZ; funding acquisition: LZ and ZC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Zhang, L., Wang, Z. et al. How does scientific research generate impact beyond academia? Cross-disciplinary comparison based on REF impact cases. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1856 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06129-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06129-4