Abstract

Motivational Interviewing (MI) can improve the quality of practice of social and health professionals, but achieving sustainable change in MI skills is difficult. MI learning is often conceptualised as an individual endeavour. Social processes have been used to support MI training outcomes to some extent, but broader social contexts remain understudied. This paper focuses on the uptake of MI in child and family social work – a field that is associated with multiple social contexts (e.g., clients, colleagues, managers, teams, and multi-professional networks). It explores the different functions that social contexts play for child and family social workers in the process of taking up MI. Child and family social workers participated in an evidence-based MI training and were interviewed individually (N = 32) post-training. Content analysis was used to explore how participants described social dimensions of taking up MI. Of the various social dimensions, social appraisal and social identification (e.g., norms, modelling, social feedback, we-intentions, common agenda and collective responsibility) were highlighted as central to the MI behaviour change process. Co-workers, peer groups and managers were identified as important social groups that facilitated or hindered the uptake of MI. The importance of the MI-trained colleagues was highlighted as a key element in facilitating the uptake and maintenance of MI. Our findings highlight, in particular, the role of social planning and collective agency in MI learning. We outline recommendations for incorporating ‘the social’ into future research and practice in MI training. Social contexts hold promise for improvement and should be harnessed to support better interactional practices among health and social care professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-quality social work practice requires good interaction skills. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a widely adopted counselling approach that emphasises collaboration, acceptance, evocation, and compassion (Miller & Rollnick, 2023). Empirical evidence shows that MI-based counselling is more effective than standard counselling across a range of behaviours and contexts (Frost et al., 2018; Markland et al., 2005). In the context of child and family social work, previous research has found an association between social workers’ interaction skills and better outcomes for service users (Forrester et al., 2019).

Social workers’ interaction skills are a prerequisite for effective client work, the building of trust, and the experience of being heard (Reith-Hall & Montgomery, 2023). The interactional context of child and family social work is characterised by power imbalances and asymmetrical power relations, stemming from the fundamental social work dilemma of balancing care and control. Particularly in the context of child protection, the working relationship between social workers, children, and families is often characterised by tense and uncooperative dynamics (De Boer & Coady, 2006; Forrester et al., 2012; Lundahl et al., 2020). It is recognised that managing the intense emotional demands of professional practice is challenging (Hussein, 2018; McFadden et al., 2015; Stalker et al., 2007). However, there is limited research on the teaching and learning of interactional skills in this emotionally charged context at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels of social work education (Reith-Hall & Montgomery, 2023).

MI appears to be helpful and relevant in the interactional context of child and family social work (Forrester et al., 2019), but it is not easily taken up in a sustainable way (Hall et al., 2016; Schwalbe et al., 2014). Current scientific knowledge about MI training for professionals outlines key factors for successful learning of skills, such as integrating observation, feedback, and coaching into training (Schwalbe et al., 2014). However, meta-analyses show that many trained professionals struggle to achieve sustainable change despite extensive training (Hall et al., 2016; Schwalbe et al., 2014). There are significant gaps in the evidence on how to most effectively train and support professionals in taking up MI in a sustainable way, and professionals who are trained in MI may have a hard time implementing it. Social contexts have been used to some extent in understanding how best to train MI (e.g., group-based coaching, discussions within training sessions, simulations). However, social contexts can influence this process in many other ways that have not yet been explored.

MI training tends to be individualistic. Interaction training interventions typically consist of information provision and practical exercises. The need to identify the most effective scaffolding strategies for teaching and learning MI has been recognised (Kaltman & Tankersley, 2020), and MI skills training requires didactic training, practical rehearsal, and sustained support (Frey et al., 2021; Miller & Moyers, 2015). Research also suggests that role-playing and ongoing supervision to support maintenance of skills lead to greater effects (Kaczmarek et al., 2022). While MI learning is often conceptualised as an individual endeavour, it is easy to see that the above-mentioned elements are social in nature. Whilst the social context of the training, and most obviously the social context provided by the clients, is seen as essential to practice within in order to improve (Forrester et al., 2019; Miller & Rollnick, 2023), there are less obvious examples of social contexts for the learning process. Indeed, theories suggest that social influences on behaviour change can operate through multiple interpersonal pathways - dyadic interactions such as coaching being one example (Scholz et al., 2020). Social support is one of the most effective types of behaviour change intervention (Albarracín et al., 2024), and the social environment can play a crucial role in sustained behaviour change (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). For example, setting goals as a team may be more effective in achieving goals than setting goals individually (Epton et al., 2017).

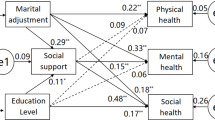

Understanding how social dimensions contribute to MI skill development, either positively or negatively, can help us to better understand the process of uptake. Ultimately, this knowledge could inform more effective training approaches. For instance, peer support might facilitate both technical skill development and deeper engagement with the spirit of MI through shared reflection and problem-solving. However, empirical investigation of such social mechanisms in MI training contexts remains limited. The current article addresses this gap by exploring the different functions and roles that social contexts (e.g., co-workers, peer groups, managers) play for child and family social workers in the process of taking up MI. Child and family social work is a field that is closely linked to many social contexts. In addition to working individually with clients, social workers typically work in pairs with colleagues, in teams, and as part of multi-professional and interdisciplinary networks, supported by managers and service leaders (see Fig. 1). Evidence suggests that working in pairs or teams has a number of benefits for social work practice. These include the potential for workplace learning (Uusitalo, 2019), the creation of space for reflection and the containment of emotions (Ferguson et al., 2020), and the impact of team stability, cohesion, and experience of support on social workers’ resilience, service quality, and potentially service users’ experience (McFadden, 2020).

Insights from behaviour change science could be used to train and support professionals in the sustainable uptake of MI (Renko et al., in press). While behaviour change research has been focused on psychological influences on behaviour, there has been an increasing focus on interpersonal and social aspects. Recently, social factors influencing behaviour change processes have been collated into a framework that may provide a useful starting point for researchers investigating social influences - the Social Dimensions for Health Behaviour (SDHB; Rhodes & Beauchamp, 2024). The authors examined constructs in behaviour change theories that are both psychological and social/relational in nature. In this study, we will use SDHB as a starting point to explore child and family social workers' accounts of how different social contexts and groups contributed to their MI learning process. In what ways do the participants make sense of social contexts that support or hinder their learning of and use of MI in client encounters?

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted as part of a larger mixed-methods research project evaluating the feasibility of the MI interaction training targeted for child and family social workers (Aaltio et al., in press). The training was originally developed in the United Kingdom and adapted to Finland. It targeted MI skills (collaboration, autonomy, empathy, and evocation), complemented with specific child and family social work skills, i.e., purposefulness, clarity about concerns, and child focus (Forrester et al., 2019). The adapted training programme was pre-tested with eight social workers and seven social work master’s students between October and December 2023, prior to the start of the actual training sessions scheduled for the spring of 2024. The present evaluation focuses on the actual training sessions, which took place in two groups between March and May 2024 and between April and June 2024.

Participants

The study was carried out in three well-being service counties in Southern Finland. The study procedures were reviewed by the ethical committee of the University of Helsinki in September 2023. Recruitment followed different routes: The training was advertised via e-mails and meetings with child and family social work teams. Altogether, thirty-three social workers were trained.

Intervention description

Both training groups received a four-day training package (training days consisted of both practical exercises, group discussions and short lectures), three coaching sessions, optional peer groups (á 4-6 persons, to reflect on the practice and learning process), and two optional online booster sessions with facilitated small group discussions on challenges and successes of adopting MI in practice. The full content of the training is described in detail elsewhere (Aaltio et al., in press). All four full-day training sessions, as well as the coaching sessions, were facilitated by three facilitators with extensive experience either in MI-based training or in social work education. To support the uptake of MI, participants’ team managers were offered a 3-day implementation coaching. Managers were advised to encourage and follow up MI skills practice in teams, for example, by using the conversation ideas for peer support sessions.

A printed workbook was given to participants at the first training session to support learning both during and between sessions. The workbook included a self-practice programme and suggested a staged schedule to make self-practice more manageable (Renko et al., in press). Participants were encouraged to reflect on their experiences, challenges, and successful applications of MI techniques in real-life settings. The self-practice programme included structured templates for peer support groups. Participants were encouraged to form groups within their teams or office locations. The programme recommended three group meetings during the training period, with flexibility in the meeting format (examples provided were 30-minute virtual meetings, face-to-face meetings, or walking meetings following team gatherings). In order to best support the targeted learning at each phase of the training, three structured discussion templates for the peer group discussions were offered in the workbook, incorporating several behaviour change techniques: social support (practical and emotional) through guided peer discussions, problem solving through structured reflection on implementation challenges, and restructuring of the social environment through by establishing regular peer contact. Each template guided participants through progressively more advanced MI elements: the first focused on implementation of - and barriers to - basic skills and reflective listening, the second on reinforcement and change talk recognition, and the third on MI-consistent advice giving and session structuring. Each template included structured reflection on implementation challenges and collective problem-solving exercises.

Procedure

All participants were invited for individual interviews on the first day of the training. We conducted semi-structured individual interviews with 32 participants to capture their accounts of taking up and maintaining MI. The interviews were conducted by three researchers during the participants’ working hours. The interviews were conducted by the first (ER - a postdoctoral fellow in social psychology, with extensive experience in conducting qualitative interviews in various research projects concerning sensitive topics, interaction, and motivation), third (JM - an associate professor in social work, with a wide range of expertise in social work with children and families and in qualitative methodology) and fourth (NI - a postdoctoral researcher in social work, with a broad expertise in child and family social work and qualitative research in these settings) author, either face-to-face or via Microsoft Teams (depending on the participant’s preference) after the training, 3-8 weeks after the final training session. The interviewers were not involved with the training programme delivery. However, NI provided the training participants guidance to audio-record their own practice (these results are reported elsewhere, see Aaltio et al., in press). NI also observed all four training days in group 1, and ER observed the last two training days in group 2.

The purpose of the individual interviews was to explore the participants’ own interpretations of the course participation and of learning MI. A topic guide (see Supplement 1) was used as an interview tool to ensure consistency across interviews and consisted of three main themes: (a) general experiences of training and access to training, (b) description of MI and its application in the context of client work, and (c) training as a learning process and support for the use of MI. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. The product of the data collection was a large body of empirical data comprising 394 pages of verbatim transcribed text (font Times New Roman, font size 12, line spacing 1). The data are stored on a secure network storage location at the University of Helsinki with a backup copy. Only research staff have access to the storage location.

Analysis

This study employed a qualitative content analysis. The systematic analysis of the data was conducted with a focus on the semantic, manifest content, in accordance with the principles of inductive content analysis as outlined by Elo and Kyngäs (2008) and Mayring (2000). The rationale for selecting this method was rooted in the study design, which focuses on an in-depth exploration of participants’ perspectives.

At the beginning of the analytical process, the first author (ER) undertook a comprehensive reading of the transcripts in order to gain an overarching understanding of the entire data set. ER then undertook a second reading of the transcripts, this time focusing on the interviewees’ experiences of changes in their interaction styles during and after the training and their perspectives on the use of the self-practice programme. These preliminary readings suggested that comments about change and the use of the self-practice programme were related to various social aspects of learning MI. Based on these findings, the research focus was discussed and clarified with all authors; participants’ accounts related to the social aspects of learning MI were selected as suitable units of analysis.

ER continued the analysis to further explore how participants described the social aspects of learning MI. To do this, ER first marked all sections where the participants associated the process of learning MI with social aspects. ER-generated codes are inductively generated by exploring the data extracts and marking the data segments with coding labels (i.e., words or short phrases). To analyse and structure the social elements, ER grouped the inductively generated codes under the dimensions of the Social Dimensions for Health Behaviour (SDHB; Rhodes & Beauchamp, 2024). The framework codes constructs residing within behaviour change theories into 10 social dimensions: socially appraised perception, meta-perceptions, injunctive norms, motivation to comply, descriptive norm, perceived social support, appraisal of others, attachment ties, shared cognition, and relational self-perceptions. The authors note that an additional 46 constructs were broad, catch-all terms like ‘social factors’ or ‘interpersonal influences’, and call for increased attention to the nuanced ways in which social processes shape behaviour (Rhodes & Beauchamp, 2024). Following the initial grouping of codes into SDHB dimensions, the grouping was presented to and discussed among the co-authors, who provided feedback on the relevance and refinement of themes. Final grouping was generated and named by ER.

The SDHB was originally developed as a working taxonomy in the field of health behaviour research. To our knowledge, there are no comprehensive frameworks that encompass a wide range of social factors related to interaction behaviour change, so we used the SDHB as a starting point.

In order to understand the barriers and facilitators to optimal uptake of motivational interviewing, it is important to recognise that motivational interviewing and behaviour change are intertwined. First, motivational interviewing can play an important role in promoting and sustaining desirable behaviours (Hagger & Hardcastle, 2014). Second, motivational interviewing is itself a behaviour that is embedded in a wider social context and can be learned, promoted, and thus changed. The SDHB proved to be a valuable analytical framework for exploring the social aspects of interactional behaviour change in our interview data. The framework facilitated the categorisation and organisation of social aspects and allowed the addition and removal of dimensions to achieve a more optimal fit with the social aspects described by participants in our data set.

Results

In general, participants associated learning MI with a variety of social contexts. In the interviews, participants described learning MI as an inherently social process in which the acquisition of skills is facilitated or hindered by the input of others, such as peer groups, managers, and, in particular, MI-trained colleagues (including team members and co-workers). To further analyse the social processes involved in learning MI, we used the SDHB (Rhodes & Beauchamp, 2024, see Analysis section above) framework as a starting point. The SDHB includes social appraisals (socially appraised cognitions and socially appraised behaviours) and social identification dimensions. Table 1 provides a summary of the dimensions ER analysed from the data and shows how and with which social groups they were described in the context of MI uptake (Supplement 3 provides this table with sample citations).

Social appraisal dimensions of learning MI

Socially appraised cognitions

Interpreted through the lens of the SDHB, the participants described a number of social appraisal dimensions of learning MI. Their descriptions of socially appraised cognitions included beliefs about how participants were seen by their colleagues (i.e., metaperceptions). In the context of learning MI, this included participants' own beliefs about how their colleagues saw them handling significant instances of interaction, acknowledging their performance. However, participants noted that a common understanding of MI is a prerequisite for recognising success.

24: If I would be alone from this work community, then it would be a lot more difficult. Now when I can talk with somebody who knows what I mean with what I bring up, so it’s a lot easier, than if I tried to just anybody, like did you notice, like what type of a question I asked.

The current project included the implementation of coaching to engage leaders and managers in change processes (Isokuortti et al., in press). Participants talked about how injunctive norms within their organisations supported learning MI. Strengthening these norms was particularly associated with managers who were seen to be “fully on board (24)”, to think that “this is good training (24)”, and to create opportunities to participate in the training and to develop professionally in general.

1: That the manager has been willing to arrange such an opportunity, that you can participate in it. Certainly also arranges that time for us, for example like in a team or somewhere, so that we can do that kind of personalisation, such as with the workbook, for example.

….

Overall, the role of the manager is that there is that attitude of going forward and evolving, and it is palpable. They always hope that you will go, that you can go take part in this or that. And yeah, go ahead and test it. And what a good idea. That there’s permission to think about things.

However, a few participants indicated that they had expected and anticipated that their managers would communicate more robust injunctive norms to facilitate learning MI. They felt that the role of the manager in supporting learning MI remained unclear.

15: At least I don’t feel that I’ve received any kind of support for this from the manager, even though they’ve apparently been to the implementation trainings. That that has then perhaps remained a little unclear to me, like how has it been thought, that the managers support this, the learning of new skills.

….

That you can ask, like how you are doing in learning these skills and what kind of support would you need, and somehow then maybe lead that kind of joint discussion for the team about this. So that we could talk together, about what kind of things we’ve gotten from this training, and so at least for now we haven’t really had that here.

Socially appraised behaviours

In relation to socially appraised behaviours, participants talked about appreciating their team members’ skills and enthusiasm for learning MI (descriptive norms): “And you hear how someone else is using these very methods, it’s great to watch from the sidelines. They are such skilled people at this job (25)”. Participants also described how acknowledging accomplishments in a peer group created collective descriptive norms. The achievements identified in the peer group inspired ways of interacting in the future.

11: And in a way we always start at the beginning. Like well, I haven’t really thought about this at all. But then when you start to talk about it, then you’re like, well, actually, I have. And then we also quite often share about those cases and experiences with them. And I think that’s really valuable.

…

Well somehow they then, nevertheless our conversation started. But maybe they then in a way gave some kind of inspiration, that we shared. Even though at first you couldn’t think of any real cases. But then you could after all. And then we talked about them and then we kind of forgot about the workbook.

On the other hand, some pointed out that collective descriptive norms created in the peer group could also hinder MI learning by providing a blessing for idleness and inactivity in practicing MI.

32: Sometimes we were a couple of us from here on the same computer, but in a way we held them remotely and I thought they were pretty nice, that you could talk about whether you had remembered, and you got that peer support, that apparently nobody else remembered either to do something at some point.

Social modelling was seen as an important feature for learning and sustaining MI. Participants talked about how they modelled and imitated their colleagues to better learn and practice MI. Listening carefully and observing others during coaching sessions and client encounters were described as prerequisites for social modelling: “So that in a way I may have observed more closely how others work. And in some ways I’ve picked up the good stuff from there (24).” Participants also considered how they could spread the word about MI to their colleagues and act as role models for others.

32: At the same time there were some situations, where someone had for example used the complex reflection in some really challenging situation, and said, that it had then opened up the situation and taken the matter forward, that the meeting didn’t end up becoming an argument, so then there were those situations, that others there were also like I could try that myself as well.

Participants associated perceived social support and the sharing of learning experiences with positive feelings and emotions. They described how sharing made their learning experience complete, and reflected that, alone, this experience would have remained dull. Participants also reflected on how they could share different feelings and cases related to learning MI.

11: I think sharing with others has been really important in this. Like this wouldn’t have, alone it would have been really bleak. So you’ve been able to mirror other people’s thoughts to your own. And now, for example, when we had this our [place] group meeting in the morning. It was really fun. It’s really nice to hear.

35: I think that what has been somehow wonderful in my opinion, is that I have also seen those other colleagues and in a certain way, perhaps noticed that the things, where you experience enormous frustration with client cases and with clients and their parents, that they are universal in their own way. That yes actually others feel also, that in a way I am not alone.

Participants described how the peer meetings and their reflective working community helped to clarify parts of the training content that had felt distant, acted as a reminder and helped to bring MI back to mind.

33: And then the peer meetings have also been useful, because there is between the training days, they have reminded me of this topic and brought it back to mind, so otherwise it can easily be forgotten in everyday life.

…

Well, for example, in the group, when we recalled what they were, like what we could practice and what kind of techniques, so, for example, the change speech, which remained for several people, or felt that it remained a little bit more foreign, so then we revised it together, like what was it that it meant and what it consisted of.

Participants saw bringing MI back to mind as essential, also from the perspective of continuity and maintaining MI in the future: “So it was meaningful, and somehow in terms of that kind of continuity. So that the topic lives on in the whole team (10)”. Participants described how this recall was done in collaboration with a colleague and/or team through collective remembering.

31: That somehow there would be those meetings at least every once in a while, where you would talk about this or would bring back to mind these things. It could very well be in our peer group also. Somehow so, that it would maybe maintain these learnt things.

However, sharing and reflecting with colleagues has not been without its challenges. Participants expressed how easy it was to get off track while sharing: “Our problem is probably always that then it starts meandering the conversation always somewhere (1)”. Some pointed out how the structure provided in the workbook could have helped to focus the discussion.

16: but then when we were with our own group, it was maybe a bit more free in a way. Like, we had the workbook there.

H2: Yeah (nice)

16: We did use it, but it probably went a bit off the rails, the discussion, but we had it there as a foundation.

Participants described the importance of receiving social feedback on MI skills from MI-trained colleagues. They also noted that both giving and receiving feedback requires courage: “It requires having a colleague who dares to say something. And doesn’t just say that it went really well (24).”

35: So that there would’ve been, for example, the opportunity to have meetings together with someone who has been through this training with me. So that you would’ve gotten also somehow, like hey did you notice, or you could’ve gotten that kind of peer feedback on, like hey did you notice, when we talked there about this and this thing. So did you notice, that at first you started to, but then hey you corrected it like this. Or like hey at this point I was left wondering whether this could have been. So that then you could be at the meeting as a kind of sparring partner.

Social identification dimensions of learning MI

Participants’ accounts were also related to different social identification dimensions of learning MI. They described bonds (attachment ties) with their MI-trained colleagues: “It’s been wonderful, when there have been others in the same, so that you’re not alone here talking and thinking and evaluating things (1).” Participants talked about feeling safer when they attended the training with familiar colleagues: “I encouraged my co-workers also, so that I don’t have to go alone (21)”.

5: We hoped for it in beginning, that we would all get to it (coaching session) together. So that no one would have to go alone in a way. Because it felt, that it was earlier, that we were really vulnerable there. Everyone was terribly nervous about the situation. And somehow it’s even quite scary that situation, when you get from your own work, where everyone is doing it with such a big heart.

Some participants also commented on how attending the training with their colleagues and team members enhanced the sense of community, making it easier to ask for help in learning MI.

2: We were like with our own, who are from the same unit here [name of place] so like next to each other, and even though we did quite a lot with the people next to us, so I didn’t mind, because it was perhaps a little bit like strengthening for our sense of community, which we don’t have time to like do here during working hours.

….

I think it was like necessary, because then it always makes it easier to ask for advice and help, then here in like your own work community.

Furthermore, according to our interpretations, social dimensions of shared cognition were also evident in participants’ accounts of learning MI. Participants spoke of how they have used social goal-setting in order to attend the training: deciding with their team members that yes, we will participate.

10: Maybe I’d say, that if it wouldn’t have been the team’s thought, that let’s go then, then I probably wouldn’t have been like, well I’ll go alone, and I thought that it supports the learning as well, that there were at least a few of us there. It was a positive group pressure, where you could think about whether you would want to go.

In addition, the participants talked about we-intentions to build and enhance the social motivation to learn MI: “Co-workers. They help a lot. Because when we have that enthusiasm there, then it makes it so that I don’t have to be there alone. It’s somehow wonderful that there are many of us (25).”

In addition to social goal setting and motivation, participants also described a shared understanding of optimal communication style as something essential to learning MI. The significance of the MI-trained co-worker/team was highlighted as a pivotal element in facilitating the implementation and maintenance of MI. In the absence of MI skills among team members, it can prove challenging to use these skills effectively if a co-worker or other team member ‘steer’ the interaction in a manner that is contrary to the principles of MI and: “Gets in the way of your own method (6)”.

Participants spoke of how this similar challenge was also, and frequently even more markedly, evident when engaging with broader interdisciplinary networks and a diverse array of professionals. They described the frustration and despair they experienced when attempting to practice MI in a multi-professional environment where everyone had their own aims, agendas and styles of interaction. They also highlighted the difficulty of integrating MI into the counter-MI styles of interaction used by other professionals.

5: It’s really difficult because everyone has their own agenda. You have to get it somehow, like, talked about beforehand. That’s probably the most challenging part. Because you’re not on your own, but you rely on other authorit-. I think it’s really, if you start thinking about it, it’s quite frustrating.

2: Because there are quite a lot of these joint discussions with different parties. So not everyone has that motivational interviewing training. So, then they may be a little different those meetings, if like one party starts having a kind of monologue. And at times if you go to some hospital, then it’s that kind of a hierarchical environment, where that kind of doctor monologue begins and then when the monologue ends, they say that they have another place to go to and now you others can continue or the social side can continue, while I leave [laughs].

Participants also described the importance of social planning and goal setting with a colleague or team member in how to conduct meetings with clients. On the other hand, they also expressed how social planning and goal setting could make it easier to use the workbook and the self-practice programme to learn MI.

15: Well yes and they (co-worker who attended the training) have made it a lot easier to plan ahead as well, and then we’ve somehow thought about, like how will we orient ourselves to the meeting together, and how we think that these things are important to approach and somehow. I notice that it’s been really meaningful with a person who is in this same training.

29: And for example, just a small thing, that if you for example ask a question from the client and wait for that silent moment to come, then some employees don’t have the patience to be silent for very long. So even that kind of a pretty small thing, but in terms of your working a pretty big thing, so how these things, for example before a meeting, how these are agreed upon and planned. These are those small, but meaningful things.

Finally, participants also associated learning and practising MI with relational self-perceptions, namely shared responsibility and public engagement within their working community. They described how this sense of shared responsibility facilitated the maintenance of peer groups and the continuation of practice and learning in the future. We have a shared future and a shared responsibility to make it better.

6: We probably also have some personal responsibility for this learning process for how I keep it up myself, so it’s probably something, that is now more emphasised by the team and the work partnership.

Participants spoke of how positive interdependence could help to generate together ideas for sustaining MI in the future: “How we could support it, what we could practice, how we could run that peer group idea and make it suit ourselves, maybe that (1).”

26: The idea is good, that with those two colleagues from child protection I would try to, or at least one, the other has been bit less on board, that we would keep it up. That we would come back to this every now and then. We’re in the same unit but different teams. I should talk with them, that it should maybe be like, that you can also create it yourself.

Discussion

Ensuring optimal interaction styles among professionals is a promising strategy to enhance the quality of child and family social work. This study makes several contributions to the understanding of how comprehending social dimensions can enhance MI training. First, while previous research has identified the need for effective scaffolding strategies in MI training (Kaltman & Tankersley, 2020), our findings reveal various social processes in skill development. The perceived importance of collegial peer support activities suggests that social dimensions of learning may be more influential than previously recognised in MI training literature.

Practical, theoretical, and policy implications

First, these findings have important implications for the conceptualisation and design of MI training interventions, particularly in the context of child and family social work, but also beyond the social work context. Our findings challenge individualistic approaches to MI skill development. While existing training programmes (Hall et al., 2016; Schwalbe et al., 2014) typically focus on individual-level processes among professionals working individually, our findings suggest that MI learning in child and family social work contexts operates as a highly collective process, shaped by social support, shared norms, and organisational culture.

Second, the findings can inform organisational policy. Achieving change in the child and family social work setting seems to require wider organisational change (Forrester et al., 2018), and it is important to engage leaders and managers in the change process. For this reason, implementation coaching was included in the current project. While the leaders and managers felt that the coaching was beneficial for the introduction of MI in teams, especially frontline managers wished for more information about the MI itself to be able to better support social workers in exercising the skills (Isokuortti et al., in review).

Third, our findings contribute to theory building, particularly in relation to the social dimensions of professional learning. The importance of social dimensions is consistent with the broader behaviour change literature, which highlights the key role of social processes in professional behaviour change, but represents a novel finding in MI training research.

Finally, these findings have practical implications for MI training. First, training programmes should explicitly support social learning mechanisms. Our study showed that within the context of child and family social work, training participants preferred to reflect on their practice and experiences together, rather than individually, and that peer group discussions brought useful contributions, over and above counselling and feedback sessions with the facilitators. Secondly, individual practice materials may be more effective if they are embedded in social contexts, e.g., by encouraging participants to set up times to fill in self-assessment sheets and work through supporting material in meetings with peers. Setting up peer group meetings also provides an additional opportunity to break learning objectives into more manageable “chunks”, and thus encourage practice/rehearsal. Thirdly, organisational support for peer learning could be considered, especially if MI training is organised for several employees in an organisation. Table 2 summarises the recommendations.

Several limitations should be noted. The SDHB framework has been developed as a working taxonomy to help researchers categorise and organise social variables in health behaviour research. In this study, the target behaviour is learning MI, not health behaviour. Nevertheless, analysis of the data shows that these dimensions are useful in outlining the variety of ways in which interviewees describe the role of social relationships in learning MI. Strengths of our study include a nuanced sample of individual interviews, allowing for rich insights and perspectives on the topic.

Our findings indicate that, within the field of child and family social work, taking into account the social dimensions could promote sustainable change in interactional styles. Although this study does not provide conclusive evidence on to the objective effectiveness of social learning processes compared to isolated learning, it generates an important aspect to be studied in the future. Future research should investigate how different social support mechanisms contribute to the development of MI skills among professionals in different professional settings, and how these can best be integrated into training programmes. With a more highly powered design, one could establish how much, on average, and especially for whom, and under which conditions, such peer group/social learning elements more readily improve training outcomes. In addition, research is needed to understand how professional role demands (Renko et al., 2022) and organisational contexts influence the effectiveness of different learning approaches (Forrester et al., 2018).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential value of focusing on social dimensions when applying behaviour change science to MI training and highlights the crucial role of social processes in professional skill development. Participants described how they worked together towards the goal of learning MI, demonstrating collective agency (Bandura, 2006). These findings may inform more effective approaches to supporting the sustainable implementation of MI in child and family social work practice and across a range of helping professions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to compromising privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aaltio E, Saurio K, Heino M, Pasanen K, Isokuortti N, Alasimonen L, Moilanen J, Hankonen N, Forrester D, Jäppinen M Motivational Interviewing training for child and family social workers in Finland: An exploratory evaluation study. Br J Soc Work (in press)

Albarracín D, Fayaz-Farkhad B, Granados Samayoa JA (2024) Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions. Nat Rev Psychol 3(6):377–392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00305-0

Bandura A (2006) Toward a psychology of human agency. Psychol Sci 1(2):164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

De Boer C, Coady N (2006) Good helping relationships in child welfare: Learning from stories of success. Child Fam Soc Work 12(1):32–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00438.x

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62(1):107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Epton T, Currie S, Armitage CJ (2017) Unique effects of setting goals on behavior change: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 85(12):1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000260

Ferguson H, Warwick L, Cooner TS, Leigh J, Beddoe L, Disney T, Plumridge G (2020) The nature and culture of social work with children and families in long-term casework: Findings from a qualitative longitudinal study. Child Fam Soc Work 25:694–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12746

Forrester D, Westlake D, Glynn G (2012) Parental resistance and social worker skills: Towards a theory of motivational social work. Child Fam Soc Work 17(2):118–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00837.x

Forrester D, Westlake D, Killian M, Antonopolou V, McCann M, Thurnham A, Thomas R, Waits C, Whittaker C, Hutchison D (2019) What is the relationship between worker skills and outcomes for families in child and family social work? Br J Soc Work 49(8):2148–2167. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy126

Forrester D, Westlake D, Killian M, Antonopoulou V, McCann M, Thurnham A, Thomas R, Waits C, Whittaker C, Hutchison D (2018) A randomized controlled trial of training in motivational interviewing for child protection. Child Youth Serv Rev 88:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.02.014

Frey AJ, Lee J, Small JW, Sibley M, Owens JS, Skidmore B, Johnson L, Bradshaw CP, Moyers TB (2021) Mechanisms of motivational interviewing: A conceptual framework to guide practice and research. Prev Sci 22(6):689–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01139-x

Frost H, Campbell P, Maxwell M, O’Carroll RE, Dombrowski SU, Williams B, Cheyne H, Coles E, Pollock A (2018) Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE, 13(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204890

Hagger MS, Hardcastle SJ (2014) Interpersonal style should be included in taxonomies of behavior change techniques. Front Psychol 5:254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00254

Hall K, Staiger PK, Simpson A, Best D, Lubman DI (2016) After 30 years of dissemination, have we achieved sustained practice change in motivational interviewing? Addiction 111(7):1144–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13014

Hussein S (2018) Work engagement, burnout and personal accomplishments among social workers: A comparison between those working in children and adults’ services in England. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 45(6):911–923

Isokuortti N, Muurinen H, Heikkinen A, Palsola M, Kouvonen P Implementointiosaamisen vahvistaminen sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollossa: johtajien ja esihenkilöjen kokemuksia valmennuksesta [Enhancing implementation competence in social and health services: leaders’ and managers’ experiences from a coaching]. Sosiaalilääketieteellinen Aikakauslehti [J Soc Med]. In press

Kaczmarek T, Kavanagh DJ, Lazzarini PA, Warnock J, Van Netten JJ (2022) Training diabetes healthcare practitioners in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Health Psychol Rev 16(3):430–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1926308

Kaltman S, Tankersley A (2020) Teaching motivational interviewing to medical students: a systematic review. Acad Med 95(3):458–469. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011

Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski SU, White M, Sniehotta F (2016) Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev 10(3):277–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

Lundahl B, McDonald C, Vanderloo M (2020) Service users’ perspectives of child welfare services: A systematic review using the practice model as a guide. J Public Child Welf 14(2):174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2018.1548406

Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S (2005) Motivational Interviewing and self–determination theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 24(6):811–831. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.6.811

Mayring P (2000) Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

McFadden P (2020) Two sides of one coin? Relationships build resilience or contribute to burnout in child protection social work: Shared perspectives from Leavers and Stayers in Northern Ireland. Int Soc Work 63(2):164–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818788393

McFadden P, Campbell A, Taylor B (2015) Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. Br J Soc Work 45(5):1546–1563. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct210

Miller WR, Moyers TB (2015) The forest and the trees: Relational and specific factors in addiction treatment. Addiction 110(3):401–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12693

Miller WR, Rollnick S (2023) Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. The Guilford Press

Reith-Hall E, Montgomery P (2023) Communication skills training for improving the communicative abilities of student social workers: A systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev 19(1):e1309

Renko E, Kohonen K, Heino M, Palsola M, Aaltio A, Jäppinen M, Forrester D, Hankonen N Beyond Training: Evaluation of Practitioner Behaviour Change Booster Components as Part of a Motivational Interviewing Training Programme. Psychol Serv (in press)

Renko E, Koski-Jännes A, Absetz P, Lintunen T, Hankonen N (2022) A qualitative study of pre-service teachers’ experienced benefits and concerns of using motivational interaction in practice after a training course. Hum Soc Sci Commun 9:458. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01484-y

Rhodes RE, Beauchamp MR (2024) Development of the social dimensions of health behaviour framework. Health Psychol Rev, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2024.2339329

Scholz U, Berli C, Lüscher J, Knoll N (2020) Dyadic Behavior Change Interventions. In Hamilton K, Cameron LD, Hagger MS, Hankonen N, Lintunen T (Eds.), The Handbook of Behavior Change (pp. 632–648). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108677318.043

Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A (2014) Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta‐analysis of training studies. Addiction 109(8):1287–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12558

Stalker CA, Mandell D, Frensch KM, Harvey C, Wright M (2007) Child welfare workers who are exhausted yet satisfied with their jobs: How do they do it? Child Fam Soc Work 12(2):182–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00472.x

Uusitalo I (2019) Työssä oppiminen lastensuojelun sosiaalityössä—Reunaehtoja ja mahdollisuuksia ammatillisen asiantuntijuuden kehittymiselle [Väitöskirja]. Turun yliopisto

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants. We also thank Elina Aaltio, Donald Forrester, Minttu Palsola and Kaisa Pasanen for their contributions in developing/modifying the intervention and designing data collection. Thanks to Laura Alasimonen, Meri Haikonen, Nuppu Koivu and Kaisa Saurio for their contributions in data collection and Leena Ehrling and Sirpa Tapola-Tuohikumpu, who acted as trainers together with Jäppinen. This research was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (grant ID VN/14893/2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by ER, JM and NI. The analyses were performed by ER. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ER and MH All authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MH created the visualisations. NH and MJ provided supervision, coordinated the project and acquired the funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval statement

The ethics approval for the study protocol was obtained from the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences (Ethical approval number: Statement 59/2023), date of approval: 1.9.2023. The review board states that the planned study is ethically acceptable (scope of approval: the approval covers data collection, participant recruitment, participant groups, intervention, research methods used, and the overall study design). All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Consent was obtained orally before starting the interview by the interviewee from the participant (interviews took place between 30.4.2024 and 27.6.2024. The consent was audio-recorded and covered participation, data use and consent to publish. According to Finnish data protection legislation and the GDPR, recorded oral consent is considered equivalent to written consent because it is recorded and can be verified afterwards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Renko, E., Heino, M.T.J., Moilanen, J. et al. How do social contexts support practitioners’ uptake of Motivational Interviewing? Social identification and appraisal among child and family social workers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06133-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06133-8