Abstract

On the basis of data from 274 prefecture-level cities in China from 2011 to 2022, we use two-way fixed effects and threshold models to assess the impact of green financial technology on carbon emission efficiency. The results indicate that green fintech significantly enhances carbon efficiency, primarily by driving green innovation and advancing artificial intelligence technologies. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that this promoting effect is more pronounced in western regions, nonlow-carbon pilot cities, areas with lower digital infrastructure, areas with higher coal consumption ratios, and areas with low greening level, suggesting that green fintech provides crucial support for economic transition and emission reduction in less developed or carbon-intensive areas. However, the study also identifies a nonlinear relationship: the positive effect of green fintech on carbon efficiency exhibits diminishing marginal returns, indicating that its contribution gradually weakens as green fintech itself develops. Furthermore, while green fintech facilitates low-carbon transformation, it faces the paradox of a “digital carbon footprint,” where energy-intensive data centers and algorithms may partially offset its carbon reduction benefits, and technology gaps could exacerbate regional inequalities in climate governance. In addition to the global push for carbon neutrality, these findings underscore the need to optimize the application mechanisms of green fintech to maximize its net environmental benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of the global response to climate change, carbon peaking and carbon neutrality have become the common goals of governments and international organizations. Since the Paris Agreement was signed, an increasing number of countries and regions around the world have defined timetables and roadmaps for achieving carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. China has set the ambitious goal of achieving a carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. The European Union and the United States have also issued carbon neutrality targets and focused on promoting the green transformation and sustainable development (Luo et al., 2021). However, although countries have adopted a series of policies and measures to promote the reduction of carbon emissions, global carbon emissions are still on the rise, and the task of carbon emission reduction is still arduous (Ben et al., 2022). At the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in 2024, the urgency of global climate governance and the role of green finance are once again at the forefront of discussion (Opoku-Mensah et al., 2024). The conference highlighted the need for the global green transition to rely on innovative fintech tools to facilitate the efficient functioning of carbon markets and the further growth of global climate finance (Bakhsh et al., 2024; Roy et al., 2024). In particular, developing countries, owing to the shortage of technology and capital, face greater green transformation challenges. The application of green financial technology in this context provides strong support for reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable development on a global scale.

As a combination of financial and technological innovation, green fintech has become an important tool for promoting the realization of carbon peak carbon neutrality (Liu et al., 2021). With the progress of science and technology and the application of technologies such as digitization, artificial intelligence, big data and blockchain, green finance is not limited to traditional forms such as green bonds and green funds but also includes more accurate carbon asset management, green project evaluation and monitoring, and digitalization of the carbon trading market and other emerging fields (Zhang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). For example, by establishing a green finance market framework, the EU is pushing financial institutions to incorporate climate and environmental factors into their decision-making processes. China is incentivizing companies and financial institutions to invest more in a low-carbon economy through instruments such as green bonds, green credits and green funds.

Despite the great potential of green fintech in promoting carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, there is still a significant gap in the development of green finance among countries (Ye et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2024). Developed countries, such as the European Union and the United States, started earlier in the application of green financial technology and have formed a relatively complete green financial system and technical foundation (Yuan et al., 2019). For example, the European Union has promoted the green transformation of the financial market by formulating a green finance action plan and introducing a large number of scientific and technological innovations in the carbon emission trading market, which promoted the efficient operation of the carbon market. The United States uses advanced technological means to support the innovation of green finance, encourages technology companies to cooperate with financial institutions, and promotes the popularization and application of green technology. In many developing countries, the application of green fintech still faces technical bottlenecks, a lack of funding, and inadequate policies (Dikau and Volz, 2021). Especially in Asia, Africa and Latin America, although these countries have made some progress in promoting green development, the potential of green fintech has not been fully realized because of inadequate infrastructure, relatively backward green technology and a lack of effective policy support (Jin et al., 2021). Therefore, with China as the representative, this paper studies how the development of China’s green fintech can help achieve the goal of global carbon peaking carbon neutrality, especially in terms of improving Carbon Emission Efficiency (CEE) and realizing the path of global environmental sustainable development, which has important theoretical significance and practical value.

Although green fintech has shown great potential in promoting carbon reduction, the existing research has focused mostly on its macrolevel policy significance or technical application description. In-depth analysis of its implementation effect, mechanism of action, and regional heterogeneity is still insufficient. The existing literature has generally affirmed the promoting effect of green fintech on carbon efficiency by providing green financing channels, optimizing resource allocation and promoting green investment (Wang et al., 2024; Mehmood et al., 2025), but no systematic exploration has been carried out on its internal influence path, nonlinear characteristics and changes in marginal effects. In particular, empirical tests based on large sample data are lacking and fail to reveal the differentiated performance of green fintech under different regional, infrastructure level and energy structure conditions.

Unlike the existing studies, the innovation of this paper is reflected mainly in the following aspects: First, in terms of the research perspective, on the basis of the panel data of 274 prefecture-level cities in China from 2011 to 2022, not only is the linear promoting effect of green financial technology on carbon efficiency verified but also the threshold effect model is adopted for the first time to reveal the nonlinear characteristics of its impact and the law of diminishing marginal effect, deepening the understanding of the complex mechanism of the action of green financial technology. Second, in terms of the research findings, heterogeneity analysis reveals that the carbon efficiency improvement effect of green fintech is particularly significant in the western regions, nonlow-carbon pilot areas, regions with weak digital infrastructure, and areas with a high proportion of coal consumption. This conclusion provides a precise basis for the formulation of differentiated policies. Finally, in terms of policy implications, this paper proposes that the exertion of the effect of green fintech is influenced by multiple factors. Governments in all countries need to further optimize the efficiency of policy design and technology application, providing theoretical references and practical guidance for promoting the precise implementation of green fintech and the global carbon neutrality process.

Literature review

As a key tool for driving carbon reduction, green fintech has gained traction across multiple industries. Although the existing literature has extensively discussed the role of green finance and its technologies in promoting sustainable development, relatively few studies have directly explored the relationship between green fintech and carbon efficiency. Most of the existing research has focused on a broad discussion of the environmental impact of green financial instruments, such as green bonds, carbon trading markets, and green investment funds, with varying conclusions. Green fintech instruments, particularly green bonds (Li et al., 2022) and sustainable green investment funds (Jiang et al., 2022), have also been analyzed for their role in financing projects to reduce carbon emissions. Green bonds have become an important financial tool for raising funds for projects that reduce carbon emissions, such as renewable energy facilities and energy-efficient infrastructure. These funds not only provide economic support for enterprises to carry out emission reduction projects but also increase the market’s attention to low-carbon investment, indirectly improving the CEE of various industries (Rannou et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2023). However, while green bonds help finance sustainability projects, their impact on carbon efficiency remains uncertain because of the lack of a standardized measurement framework and globally harmonized regulatory standards (Korkut et al., 2025).

Another area of research interest is the integration of technology-driven solutions, such as blockchain and big data, into green fintech platforms that can optimize carbon trading processes and enhance carbon tracking capabilities (Hussain et al., 2023). The application of blockchain technology in carbon trading platforms has increased transparency and reduced transaction costs, making carbon markets more efficient and accessible. By improving the efficiency of carbon credit trading and verifying emissions reductions, blockchain technology can facilitate more accurate measurement and enhancement of CEE (Young et al., 2022). Similarly, big data analytics has been used to monitor and predict carbon emissions in real time, providing actionable insights that can help businesses optimize their carbon footprint (Liu et al., 2024a). Despite the promising development of big data technology, some scholars have noted the direct impact of fintech on CEE. Despite the potential of technological advances in green fintech, its actual impact on carbon efficiency varies significantly across regions and sectors (Meng et al., 2024). However, while green financial technology has positive effects, some negative effects cannot be ignored (Wang et al., 2023). First, green financial technology may exacerbate the digital divide, especially in developing countries and regions where infrastructure and technological levels are relatively backward and where the advantages of green financial technology cannot be fully leveraged. According to relevant research, the unbalanced development of technology may cause these regions to miss the opportunity to achieve sustainable development by utilizing green fintech (Bughio et al., 2025). Furthermore, the popularization of green financial tools is often accompanied by an immature market. Some green financial products have low transparency and high risks, which may lead to excessive speculation in the capital market and the formation of financial bubbles (Zhang, 2023). Finally, green financial technologies may lead to unreasonable resource allocation. Driven by technology, green capital often flows to areas with high returns while ignoring other small-scale projects that also have environmental benefits but are more difficult to quantify (Jiang et al., 2022).

As an indicator of environmentally sustainable development, CEE is based on its unique advantages in measuring the development of a low-carbon economy and environmentally sustainable development. In recent years, the research on environmentally sustainable development has received extensive attention, and many scholars have measured the environmentally sustainable development ability of this field by constructing a comprehensive index system or selecting individual carbon emission indicators (Grachev and Pliamina, 2016; Prasad and Mishra, 2017). However, the scope of sustainable development is too broad, and its definition remains controversial. Therefore, from the perspective of global low-carbon economic growth, it is more practical to focus on the efficiency of environmental governance in the environmental field (Wang et al., 2016). From the perspective of global value chains, energy efficiency does not always adequately reflect a country’s governance capacity in the low-carbon international market, especially in regard to carbon reduction. Although energy efficiency is essential for improving productivity, reducing energy waste and reducing energy consumption per unit of output, it may not fully reflect how a country is responding to the global climate change challenge, especially in terms of carbon emission reduction, which may be a more appropriate indicator (Iftikhar et al., 2016; Wang and Ma, 2018). In this context, CEE, as a measure of environmental sustainability, can accurately reflect the actual effect of a country in promoting a low-carbon transition and is highly important in the framework of promoting global environmental sustainability (Wang et al., 2019). Through carbon efficiency, we can not only assess whether a country or region can maintain or enhance economic growth while reducing carbon emissions but also better demonstrate its ability to promote global environmentally sustainable development.

Overall, although the existing literature has extensively evaluated the role of green fintech in enhancing environmental sustainability in terms of green bonds, green investments, and blockchain technology, some obvious shortcomings still exist. First, green fintech has the potential to transform carbon emission reduction strategies, but the existing literature has focused mainly on the overall impact of green fintech on the environment at different levels, and research on how green fintech affects CEE at the overall level is lacking. This limitation makes it more difficult to assess the effectiveness of regulatory and financial incentives in promoting carbon efficiency through green fintech. Second, few studies have analyzed the mechanisms through which green fintech affects carbon efficiency and have ignored the differences between different regions in promoting green fintech, which makes a comprehensive assessment of its impact difficult. For example, there are different challenges and opportunities for improving carbon efficiency across geographical locations and policy coverage areas. In addition, most of the existing studies have focused on the linear effects of green fintech and less on its nonlinear effects. Considering the financial and technical nature of green fintech, it may have nonlinear effects on CEE. Therefore, this paper expands its focus, conducts nonlinear research, and tracks the “nonlinear effects” between green fintech and emission efficiency.

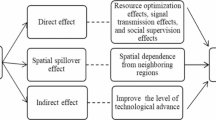

In view of these shortcomings, this paper aims to first assess the impact of green fintech on CEE, focusing on linear and nonlinear analyses at the overall level. Next, this paper explores the intermediary mechanism through which green fintech empowers CEE, the heterogeneity among regions, and the reasons for the differences in results in different regions; thus, the mechanism through which green fintech empowers the efficiency of other carbon emissions is determined. The specific research ideas are shown in Fig. 1. This analysis will help inform the formulation of more precise and effective policies to promote carbon efficiency to achieve environmental sustainability.

Research hypotheses

Green fintech and carbon emission efficiency

As a cross-disciplinary category that integrates fintech innovation and environmental sustainability goals, green fintech can not only support the development of green industries by optimizing capital allocation and promoting capital liquidity but also play a significant role in improving CEE and reducing carbon emission intensity by promoting the popularization and application of low-carbon technologies. In the actual operation process, green fintech has unique advantages in promoting green transformation, guiding resource flow, optimizing industrial structure, etc. (Le et al., 2021). According to resource-based theory and innovation diffusion theory, green fintech can effectively promote the flow of capital to low-carbon and environmental protection industries, improve CEE, and help achieve sustainable development goals (Fahy, 2000; Green and Hevner, 2000). Second, from the perspective of institutional economics, green fintech can optimize resource allocation and effectively address market failure by establishing a sound green financial system (Hamiltonet al., 1976). For example, by promoting the market-oriented application of green technologies, green fintech reduces the need for government intervention, improves the efficiency of green investment, and promotes the popularization of low-carbon technologies in the long term. Third, the driving role of green fintech is regulated by factors such as the market environment, policy support, and the degree of technological innovation. In the case of a good market environment, green financial technology can guide enterprises to more actively carry out green transformation through the capital market and promote further amplification of the carbon emission reduction effect. Accordingly, this paper proposes H1:

H1. Green fintech contributes to the growth of carbon emission efficiency.

In the early stages of green finance technology development, carbon efficiency can be significantly improved by encouraging investment in clean technology, increasing capital flows to environmental projects, and improving resource allocation. At this stage, green financial technologies act as catalysts for innovation, driving large-scale carbon emission reductions (Kerr and Avendano, 2020). Financial innovations such as green bonds, carbon trading platforms, and sustainable investment funds show great potential to channel capital to low-carbon industries, improve their production processes, and incentivize companies to adopt green practices (Zhou et al., 2022; Shao et al., 2022).

However, with the continuous development of green finance technology, its marginal benefit in reducing carbon emissions gradually decreases. Several factors contribute to this diminishing effect. First, with the spread of technology, the most impactful carbon reduction opportunities have often already been realized. Once the industry adopts cleaner technologies, it becomes more difficult to further improve CEE (Xu et al., 2023). Second, market saturation and stability in the green finance market could lead to less innovation, limiting the ability of financial instruments to create new and more efficient emission reduction opportunities. Finally, with the mainstream use of green technologies, the space for the differentiation of carbon emission reduction strategies has gradually narrowed, reducing the overall effectiveness of green finance interventions (Marra et al., 2020). Combined with the relevant theories of new economic geography, it can be inferred that the development path of green financial technology presents the characteristics of increasing returns in the early stage and decreasing returns in the later stage. Accordingly, this paper proposes H2:

H2: The development of green finance technology has a nonlinear effect on carbon emission efficiency, and as green finance technology matures, its promoting effect gradually weakens.

Green innovation and artificial intelligence

Green financial technology plays a significant role in promoting CEE through the application of green innovation. Integrating innovative environmental technologies with financial services enables more efficient allocation of resources toward sustainable projects and activities (Kerr and Avendano, 2020). Green innovation, driven by the support of financial technologies, facilitates the development and implementation of low-carbon solutions across industries. As these technologies continue to evolve, they help industries reduce energy consumption and lower carbon emissions, thus enhancing overall CEE (Zhou and Wang, 2022). Studies suggest that the introduction of green financial products and services can accelerate the adoption of such innovations, creating a positive feedback loop that further increases carbon efficiency.

Artificial intelligence (AI), a cornerstone of green financial technology, significantly contributes to CEE. AI enables the precise monitoring and management of carbon emissions across various sectors, providing real-time data and predictive analytics. Through machine learning algorithms, AI can identify inefficiencies in production processes, optimize resource usage, and recommend strategies to minimize carbon footprints. Additionally, AI helps in automating processes and decision-making, allowing for more responsive and scalable solutions to environmental challenges (Zhao et al., 2023). By facilitating the integration of AI into green financial systems, AI helps companies and industries achieve higher levels of CEE, making it an essential tool in the pursuit of sustainable development goals. Accordingly, this paper proposes H3a and H3b:

Hypothesis 3a: Green financial technology promotes carbon emission efficiency by fostering green innovation.

Hypothesis 3b: Green financial technology promotes carbon emission efficiency by leveraging artificial intelligence.

Variable selection and source

Variable selection

Explained variable: carbon emission efficiency

The core issue of this paper is environmental sustainability. CEE is used as the explained variable and is calculated via the SBM (Slack-Based Measure) model to measure the environmentally sustainable development ability of each region. The higher the CEE is, the stronger the environmentally sustainable development ability. The SBM-DDF (Slack-Based Measure-Directional Distance Function) model is constructed to calculate the CEE of each prefecture-level city. The CEE of each city in China is calculated by taking the capital, energy and labor of each city as inputs; GDP as the expected output; and CO2 emissions as the unexpected output (Xing et al., 2024). The calculation methods for each indicator are listed in Table 1.

Explanatory variable: green fintech (gfs)

In this paper, green financial technology in each region is measured through the degree of coupling coordination between green finance and financial technology. Specifically, green finance represents the role of the financial system in promoting environmental protection and sustainable development, whereas fintech refers to improving the efficiency and accessibility of financial services through technological innovation. When green finance and fintech are coupled to a high degree, the two can promote each other and synergy occurs in the process of promoting green development and sustainable investment. A high degree of coupling indicates that innovative financial technology can more effectively support the popularization and optimization of green financial products and services and can reflect the development level of green financial technology as a whole. This paper builds a coupling model of green finance and fintech for reference (Xiao & Chen, 2024), as shown in Formulas (1) to (3).

where C is the degree of coupling between fintech and green finance, and U and V are the scores of the fintech and green finance subsystems, respectively, calculated by the entropy method. Moreover, a coupling coordination model is introduced to measure the degree of coupling coordination between urban green finance and fintech.

where D is the degree of coupling coordination between the green finance and fintech systems, whose value range is [0,1], and T is the overall coordination index of green finance and fintech, reflecting the overall coordination of the two systems. To determine the α and β values of the contribution to the coordinated development level, in this paper, it is assumed that green finance and fintech are equally important; that is, α = β = 0.5.

With respect to the evaluation system of green finance, many scholars at home and abroad have discussed and studied the construction of green finance systems and constructed relatively complete index systems. On the basis of the research content and in reference to many valuable studies, this paper selects seven indicators to construct a green finance index system (Lee et al., 2024) on the basis of the research of many other scholars, the actual development situation of China’s provinces and the availability of variable data. In addition, the fintech measurement methods are divided into the following five dimensions. For the inclusive finance dimension, which evaluates the performance of the region in promoting financial inclusion and is measured in combination with the financial inclusion index of Peking University (Yuan et al., 2024); In terms of blockchain applications, this dimension examines whether the region is a national-level pilot city for blockchain innovation applications. The artificial intelligence dimension measures the level of technological application in the region and is reflected through the Baidu Artificial Intelligence Index. The development basis is measured by the cumulative number of fintech companies registered in the region and represents fintech infrastructure construction (Ding et al., 2024). The specific indicator system is shown in Table 2. Finally, the entropy method is used to evaluate the indicators of the green finance and fintech index systems. The comprehensive evaluation value of green finance and fintech is obtained by calculating the simple weight of the index. In addition, this paper plots the green fintech index of various cities in China for 4 years, namely, 2011, 2015, 2019 and 2022, as shown in Fig. 2.

Control variables

Many other factors affect the efficiency of carbon emissions. Combined with the previous literature review, the following variables are selected as control variables in this paper.

GDP per capita (lnpgdp). The index used in this paper is the per capita GDP of each city. Changes in per capita GDP may indeed have a direct effect on high-quality economic development. The per capita GDP reflects a region’s economic level and productivity. Economic development can provide more resources to support high-quality development and promote green and sustainable economic transformation (Du et al., 2012).

Government intervention (gov). In this paper, the proportion of general budget expenditure in the GDP of each city is used to measure the degree of government intervention. Government intervention can encourage enterprises to invest in low-carbon technologies and green energy by providing economic incentives such as subsidies and tax breaks to reduce carbon emissions (Xiang et al., 2023).

Green coverage rate (greenare). In this paper, the green coverage rate of each urban built-up area is used to measure the level of green coverage. By increasing green cover, especially through large-scale afforestation and urban greening, the atmospheric carbon dioxide content can be effectively reduced, and the CEE can be improved (Liu et al., 2024b).

Information development (phone). In this paper, the natural logarithm of the number of mobile phone users in each city at the end of the year is used to measure the information development of each city. Moreover, informatization promotes transparency and efficiency in all areas of society, improves public services, and enhances social governance capacity (Lv et al., 2022). By accelerating the informatization process, regions and countries can achieve more efficient and sustainable economic growth, thus promoting the economic transition to high-quality development.

Industrial structure (sc). In this paper, the proportion of the added value of the secondary industry to the added value of the tertiary industry is used to measure the level of the industrial structure of each city. Industrial structure refers to the proportion and relationships among various industries or sectors in a country or region (Zhao et al., 2020). Different industries have different energy demands, technology levels and carbon emission characteristics; thus, the adjustment and optimization of industrial structure can significantly affect CEE.

Trade dependence (open). In this paper, the proportion of total import and export trade in the GDP of each city is used to measure the degree of trade dependence. The influence of trade dependence on CEE is multifaceted (Liu et al., 2024c). On the one hand, international trade may lead to the transfer effect of carbon emissions and reduce the direct carbon emissions of developed countries through outsourcing the production process. On the other hand, trade may also promote the introduction of green technologies and the demand for low-carbon products and promote improved CEE.

Model setting

Fixed effect model

On the basis of the above assumptions, this paper aims to explore the internal mechanism through which green finance promotes CEE. To achieve this goal, a bidirectional fixed-effects model is adopted; that is, a panel data model that takes into account individual and time effects is used. The specific setting of the model is shown in Formula (4).

where CEEit is the explained variable and represents CEE; gfsit is the core explanatory variable, which represents the core explanatory variable, namely, the green financial technology index of city i in year t; and \({\alpha }_{1}\) is the transmission efficiency of CEE enabled by green fintech. If it is significantly positive, it indicates that green fintech can promote the improvement of CEE. X is the total control variable; cityi and timei are individual and time fixed effects, respectively; and \({e}_{it}\) are random disturbance terms.

Threshold effect

In this paper, a threshold model is selected to study the nonlinear impact of green fintech on CEE, and the threshold established is shown in Formula (5).

where CEEit is the explained variable, gfsit is the core explanatory variable, the threshold variable is I, and X represents the control variable. In addition, β0 is the intercept term, cityi and timei are the individual and time fixed effects, respectively, and eit is the random disturbance term. I is an indicator function, and the value of the function is 1 if the condition in parentheses is true; otherwise, the value is 0.

Data sources

(1) Sources of the variables. The data sample in this paper is the panel data of 274 prefecture-level cities in China from 2011 to 2022. The data mainly come from the China Statistical Yearbook for 2001–2023, the Statistical Yearbook of each city, the Statistical Yearbook of China Environment, the Statistical Yearbook of China Energy, and the Statistical Yearbook of China Science and Technology. (2) Processing of the variables. In accordance with the requirements of the model, the main variables are properly processed as follows: To ensure stationary data and avoid the problem of heteroscedasticity, the logarithmic transformation of per capita GDP is carried out. Similarly, to improve the stationarity of the data and eliminate heteroscedasticity, the number of patent applications, etc., is also logarithmically processed. (3) Data cleaning. First, city samples lacking indicator data are excluded. Second, for the outliers in the data, this paper adopts the tailing processing method and performs tailing processing up and down by 1% for all the continuous variables in the model. Finally, for the processing of some missing values, linear interpolation technology is adopted to fill in the missing data points, thereby ensuring the integrity and continuity of the data. The variables selected in this paper and the corresponding descriptive statistical results are shown in Table 3.

This paper conducts an empirical study on the relevant data obtained, resulting in the following descriptive statistical findings. A total of 3288 valid sample data points are collected. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for carbon efficiency (CEE), green finance (DI), and the level of economic development (lnpgdp). As shown in Tables 1–3, the CEE of the explained variable fluctuates considerably, with an average value of 0.449, a standard deviation of 0.283, and minimum and maximum values of 0.020 and 1.789, respectively. This finding indicates significant variation in CEE across different regions or enterprises in the sample. The mean value of green finance (DI), the core explanatory variable in this paper, is 0.577, with a standard deviation of 0.110 and minimum and maximum values of 0.000 and 0.849, respectively, suggesting that there are relatively developed green finance sectors in the sample, although some disparities still exist. The higher average of green finance may reflect the rapid growth of green finance in recent years and its potential to enhance carbon efficiency.

For the control variables, the mean value of the scientific and technological innovation level (sc) is 1.162, with a relatively high standard deviation of 0.565, indicating substantial variation in innovation levels across different regions or enterprises. The mean value of GDP per capita (lnpgdp) is 10.792, with a standard deviation of 0.570, suggesting noticeable differences in the overall economic level. Additionally, the average value of government expenditure (gov) is 0.201, indicating that government investment in environmental protection or green development is relatively limited but still varies. In terms of infrastructure, the average value for information development (phone) is 5.878, reflecting the general popularity of communication facilities. The mean value of green space coverage (greenare1) is 0.397, with a large standard deviation of 0.117, suggesting significant regional variation in the extent of green areas. Finally, the average level of trade dependence (open) is 0.187, indicating that economic openness is relatively low for most of the sample.

Analysis and findings

Multicollinearity test

The variance inflation factor (VIF) is a measure of the degree of multicollinearity between the independent variables in a regression model. In general, when the VIF is greater than 10, it indicates that there is a strong multicollinearity problem, which may lead to the instability of the estimated results and a decline in the interpretation ability. According to the VIF estimation results for each variable in Table 4, the maximum VIF value is 2.42, the minimum value is 1.05, and the mean value is 1.76, which indicates that the collinearity between the independent variables in the model is weak, the estimated results are relatively robust, and regression analysis can be performed.

Benchmark regression results

This study conducted regression analysis using the individual-time double fixed effects model. As shown in Table 5, the model R² is 0.875, with good goodness of fit, indicating that the model Settings can effectively explain most of the variations. After controlling for relevant variables, the impact coefficient of green fintech (gfs) on CEE was 0.257, and it was significant at the 1% level. This result confirms that green fintech has a significant promoting effect on carbon emission reduction efficiency, which is consistent with the theoretical expectations of Ran and Zhang (2023). In-depth analysis shows that this measurement result is supported by a clear real-world transmission mechanism. Green fintech enhances the efficiency of environmental governance through a dual path of “technology empowerment + financial resource allocation”: On the one hand, technologies such as big data, blockchain and artificial intelligence have enabled precise identification of green projects, dynamic assessment of environmental risks and penetrating supervision of capital flow, significantly improving the policy directness and risk control efficiency of green finance; On the other hand, it has effectively guided capital to concentrate from high-carbon sectors to low-carbon technologies and enterprises by broadening the market boundaries of green credit, green bonds and carbon financial products, thereby alleviating the financing constraints of the environmental protection industry. The synergy of this technological empowerment and financial support not only reduces the overall cost of emission reduction for society but also accelerates the industrial application of green innovative technologies, promoting a structural improvement in CEE as a whole.

From the influence results of the control variables, the influence coefficient of trade dependence (open) and the green coverage rate on CEE (TS) is significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that trade dependence and the green coverage rate can significantly promote CEE and improve environmentally sustainable development. The coefficients of the effects of government intervention (gov) and industrial structure (sc) on CEE are significantly negative. This might be because insufficient policy implementation and weak supervision have led to the failure to achieve the expected policy effects, thereby negatively affecting CEE. However, high-carbon industries account for a relatively large proportion of the industrial structure, which may lead to a decline in CEE and make it difficult to achieve effective control and optimization of carbon emissions. The influence coefficient of per capita GDP (lnpgdp) and information development (phone) is not significant. This might be because the relationship between per capita GDP and CEE may not be simple linear. Especially at certain development stages, the relationship between economic growth and carbon emissions may be more complex, and there may be an “inverted U-shaped” effect. The improvement in informatization development may indirectly affect CEE through means such as enhancing production efficiency and optimizing resource allocation, and there is a certain “lag”. In particular, when informatization has not yet fully permeated all industries, its impact may be relatively limited in the short term.

Robustness test

Exclude municipalities

China’s municipalities (such as Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) may differ significantly from other regions because of their unique economic structure, policy environment, and high level of economic development. When the impact of green fintech on carbon efficiency is examined, the presence of municipalities may skew the results. Therefore, this paper further verifies whether green fintech has a universally applicable effect on CEE by eliminating the samples of municipalities directly under the central government. In Column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient of green fintech is still significantly positive after the influence of municipalities directly under the central government is eliminated, and the model established in this paper can be considered robust.

Replace the measurement methods

To measure the robustness of the results of the influence of green fintech on CEE mentioned above, this paper changed the measurement method of CEE from the SBM model to the YCC model to measure CEE again. The regression results obtained are shown in Column (2) of Table 6. According to the results, after the measurement method of the CEE of the core explained variable is changed, the coefficient corresponding to gfs is still significantly negative at the 1% level. The coefficient symbol of the regression result of the explained variable after replacing the measurement method and the obtained conclusion are generally consistent with the above results, so the regression results above are relatively robust.

Adjust the sample period

To avoid the impact of the results of green fintech and CEE on the epidemic period, this paper selects the adjustment cycle method to test the reliability of the above results by eliminating the data during the epidemic period (2020–2022). Column (3) in Table 6 shows that the regression coefficient of green fintech in the adjusted sample period is 0.325 at the significance level of 1%, which indicates that after the impact of the epidemic is excluded, green fintech still has a promoting effect on CEE, which is consistent with the sign of the influence coefficient of the previous regression results. Therefore, the regression results above are relatively robust.

Add control variables

Finally, the control variable “human capital” is added to this paper. To ensure that the promoting effect of green fintech on CEE does not interfere with the influencing factors of missing variables, human capital is added in this paper to reestimate the model. The regression results in Column (4) of Table 6 show that after the control variables are added, the regression coefficient of the effect of green finance on CEE is positive and passes the significance test at the 1% level, which is consistent with the above results and further verifies the stability of the model in this paper.

Remeasure the explanatory variables

To verify the robustness of the coupling coordination degree model of green finance and fintech mentioned earlier, this paper adopts principal component analysis (PCA) instead of the entropy weight method to reestimate the coupling coordination degree of green finance and fintech. PCA can extract the most representative characteristic variables through dimension reduction processing, thereby avoiding the possible subjective bias of the entropy weight method, and can better identify the key factors affecting CEE. Column (5) of Table 6 presents the estimation results of the regression model that incorporates the new coupling coordination degree index into CEE. The results show that after recalculating green fintech, its impact on CEE remains significantly positive, and the results of this paper are relatively robust.

Endogeneity test

Instrumental variable method

To accurately determine the causal identification effect of green fintech on the CEE, it is necessary to address possible endogeneity problems. First, the deviation in the results is caused by missing variables in the model. On the basis of previous studies, although this paper controls a series of important factors affecting the CEE, omissions inevitably occur. Second, the problem of reverse causality. Carbon efficiency may also turn around the development of green fintech. In this paper, the internet penetration rate of each prefecture-level city is used as an instrumental variable to satisfy the externality and correlation hypothesis of the instrumental variable. Table 7 shows the results of the two-stage least squares method. The results show that in the first-stage regression, the coefficient of the instrumental variable is significantly positive, and the weak instrumental variable hypothesis can be rejected. In the second-stage regression, the coefficient of green fintech (gfs) is still significantly positive and consistent with the previous results. This suggests that green fintech can still promote carbon efficiency even after endogenous issues are eliminated.

Adopt policy-based IVs

To enhance the reliability of the causal relationship between green finance and CEE, this paper introduces policy-based instrumental variables (IVs), taking the green finance reform and innovation pilot zone policy as the policy shock to green fintech. The implementation of this policy provides natural policy shocks for different regions and can effectively eliminate potential endogeneity problems. By using the green finance reform and innovation pilot zone policy shock as an instrumental variable, a placebo test is conducted. The placebo test results in Fig. 3 indicate that the hypothesized ineffective policies (i.e., policy shocks unrelated to green finance) failed to significantly affect CEE, which further confirms the effectiveness of using green finance pilot policies as instrumental variables and the reliability of causal inference. Therefore, policy shocks can help identify the true causal relationship between green finance and CEE to a certain extent, enhancing the robustness and credibility of the research results.

Mechanism analysis

Intermediary effect analysis

This paper uses a two-step approach to test whether green innovation and artificial intelligence have an intermediary effect on the impact of green fintech on CEE, where the level of green innovation is measured by the number of green patent applications per thousand people in each prefecture-level city, and the level of artificial intelligence is measured by the penetration rate of robots. The regression results in Table 8 show that the influence coefficient of green innovation (GI) in Column (1) is 1.227 and is significant at the 1% level, which means that green fintech has a significant positive effect on green innovation. In addition, green innovation plays a crucial role in improving carbon efficiency in aspects such as green technology and energy efficiency (Razzaq et al., 2021). By promoting green innovation, we can not only reduce carbon emissions but also promote sustainable economic and environmental development. These findings indicate that environmental regulation plays a partial intermediary role in the positive promotion effect of green finance on CEE, that is, green finance enhances environmental regulation, which subsequently affects the development of CEE; therefore, environmental regulation is the transmission path of the contagion effect of green finance. To further examine the role of green fintech in promoting green technological innovation, this paper examines the impact of green fintech on the subdimensions of green patent technologies, mainly carbon capture and storage technologies (CCS), energy storage technologies (EST), sustainable energy technologies (SET), and renewable energy technologies (RET). By constructing a regression model and conducting a detailed analysis of the relevant variables, the results show that green fintech has a significant positive effect on promoting green patent technologies, especially in the fields of CCS technology, energy storage technology and renewable energy (Columns (2) to (5) of Table 8). Specifically, the popularization of green fintech helps accelerate the research and development and innovation of these green technologies, especially in the field of renewable energy, where the number and quality of patents for technologies such as photovoltaic and wind power have significantly increased.

In addition, this article uses the robot penetration rate in each prefecture-level city as the development indicator of artificial intelligence. The regression results in Table 8 reveal that the influence coefficient of artificial intelligence (AI) in Column (2) is 0.0605 and is significant at the 1% level, which means that the implementation of green financial technology promotes the development level of artificial intelligence. In addition, the application of AI in energy system optimization, such as in smart grids and demand response systems, can significantly improve the energy distribution efficiency and utilization efficiency and reduce carbon emissions (Chen et al., 2022). Therefore, artificial intelligence plays a partial intermediary role in the positive promotion effect of green financial technology on CEE; thus, it is believed that green financial technology will improve the level of artificial intelligence to improve the CEE. Finally, the impact of green fintech lies in its ability to reduce the carbon emissions of enterprises by increasing the convenience of financing costs. Specifically, green fintech enhances the service efficiency of financial institutions and optimizes the loan process, enabling enterprises to obtain financing more conveniently. This directly affects the reduction in financing costs. To test this impact, this paper uses the natural logarithm of the loan balance of financial institutions as an indicator to measure the financing cost. The results in Column (7) of Table 8 show that the introduction of green fintech significantly enhances the accessibility of financing, prompting enterprises to increase their investment in low-carbon technologies and environmental protection projects and ultimately achieving an effective reduction in carbon emissions.

Heterogeneity analysis

To investigate in depth the differences in the impact of green financial technology (gfs) on the CEE in the eastern, central and western regions of China, this study, on the basis of the regional division standards of the National Bureau of Statistics, divides the sample cities into three major regions: the eastern, central and western regions. The regression results in Columns (1) to (3) of Table 9 show that the impact of green financial technology on CEE presents a significant gradient difference between the east, central and western regions. The estimated coefficient in the western region is significantly positive at the 1% level and is notably higher than the full sample estimate, indicating that the carbon reduction effect of green fintech in this region is the most prominent. This phenomenon can be explained from the perspective of regional development characteristics and marginal effects: The industrial structure in the eastern region is composed mainly of high-tech industries and modern service industries. The existing green financial system is relatively complete, and the marginal improvement brought by green financial technology is limited. In the western region, the proportion of traditional energy industries is relatively high. Through technologies such as blockchain traceability and big data risk control, green financial technology has effectively addressed the issue of information asymmetry in green project financing and has significantly improved the efficiency of resource allocation. The estimated coefficient of the central region failed the significance test, indicating that the region may be in a transitional period of industrial transformation. The integration depth of green financial technology and traditional industries is insufficient, resulting in the carbon reduction effect not being fully manifested. This discovery is in line with the “structural inertia” theory of the transformation and development of emerging economies, indicating that the stage of regional economic development is an important constraint affecting the effectiveness of green financial technology.

The policy of low-carbon pilot cities is a significant measure taken by China to promote carbon reduction. To study the differences in the carbon reduction effect of green financial technology between low-carbon pilot cities and nonpilot cities, this paper divides the sample cities into pilot and nonpilot groups on the basis of the list of “three batches” of low-carbon pilot cities announced by the National Development and Reform Commission. The group regression results based on the low-carbon pilot cities (Columns (4)–(5) of Table 9) show that the impact coefficient of green financial technology in nonpilot cities reaches 0.273 and is significant at the 1% level, which is significantly greater than that in pilot cities. This seemingly paradoxical phenomenon actually reflects the inherent law of policy effects: The pilot cities have established relatively complete green financial infrastructure through previous policy intervention, and the marginal contribution of green financial technology is relatively limited. However, in nonpilot cities, owing to the lack of a systematic low-carbon policy system, green fintech effectively compensates for the insufficient institutional supply through digital platforms, smart contracts and other technologies, generating a more significant policy substitution effect. This discovery provides new empirical evidence for understanding the interaction between the institutional environment and technological innovation and echoes the theory of “directed technological change”.

To further investigate the effects of differences in regional digital infrastructure levels and the degree of reliance on coal in energy structures on the carbon reduction effect of green financial technology, this paper also conducted a grouped regression analysis based on the development level of digital infrastructure and the proportion of coal consumption in sample cities. Among them, the level of digital infrastructure is measured by the number of mobile communication base stations, while the energy structure is represented by the proportion of coal consumption in total energy consumption. The results in Columns (1) to (4) of Table 10 show that the impact of the development level of green fintech (DI) on CEE is significantly heterogeneous under different conditions. In regions with relatively low levels of digital infrastructure, green fintech has a significant positive effect on CEE (coefficient of 0.402), indicating that in areas with relatively weak digital foundations, green fintech can significantly improve carbon efficiency by increasing financing convenience and reducing the financing costs of green projects. In contrast, in regions with a more developed digital infrastructure, the impact of green fintech on carbon efficiency does not pass the significance test. This may be because the original digitalization level in these regions is relatively high, and the marginal improvement effect brought by green fintech is limited, making it difficult to further significantly promote the improvement of carbon efficiency.

On the other hand, the characteristics of the energy structure also significantly regulate the policy effects of green financial technology. In regions with a relatively low proportion of coal consumption, the impact of green financial technology on CEE is negative but not significant, indicating that these regions have initially formed a relatively low-carbon economic structure and that the role that green financial technology can play in reducing emissions is relatively limited. In regions with a high proportion of coal consumption, green financial technology has a significant positive effect on carbon efficiency (coefficient of 0.566), indicating that the demand for green financial technology in these areas is more urgent. It effectively promotes the improvement of CEE by optimizing resource allocation, guiding green investment and supporting the clean transformation of energy. On this basis, through multidimensional heterogeneity analysis, this study reveals the complex mechanism of the carbon reduction effect of green fintech. First, the effect of green fintech is jointly constrained by multiple factors, such as the regional development stage, institutional environment, infrastructure and energy structure. Second, there is a significant complementary and substitutive relationship between green financial technology and traditional green financial tools, and it shows a stronger policy substitution effect in regions with insufficient institutional supply. Third, the effect of green financial technology shows a distinct marginal diminishing feature, and differentiated promotion strategies need to be formulated on the basis of regional characteristics.

Finally, to examine the boundary conditions of the impact of green financial technology on environmental sustainable development, this study grouped each city based on the median of the built green space area and conducted heterogeneity tests. The test results in columns (5) to (6) of Table 10 show that there are significant differences between groups in the effect of green financial technology. Specifically, in the group of cities with lower greening levels, the coefficient of gfs is 0.611 and is significant at the 1% level, indicating that green fintech can significantly promote the environmental sustainability of such cities. However, in the urban group with a higher level of greening, the coefficient of gfs was negative and not significant. For the possible reasons why the impact of green financial technology is not significant in the group of cities with a higher level of greening, we conduct the following in-depth analysis: Firstly, this may be related to the law of diminishing marginal effects. In cities with a high level of greening, the infrastructure for environmental governance is already relatively complete, and the quality of the ecological environment may have approached a relatively high “ceiling”. At this stage, as an incremental policy tool, the marginal improvement space that green financial technology can bring is relatively limited, so its statistical effect is not significant. Secondly, there may be policy substitution or saturation effects. Highly green cities are usually economically developed regions with strict environmental protection standards. They may have long implemented a series of strong environmental regulations and green industrial policies. Against this backdrop, the role of green fintech has been partially replaced or masked by these existing and more forceful policy measures, making it difficult for its independent contribution to stand out.

Threshold effect test

Before regression estimation, it is necessary to determine the threshold number of the model to correctly set the model form. In this paper, green finance is taken as the threshold variable, and Table 11 shows the results of the threshold test with green fintech as the threshold variable. The single threshold hypothesis, double threshold hypothesis and triple threshold test are carried out on the threshold effect. Columns (3) and (4) present the F statistics obtained after hypothesis testing and their corresponding P values, respectively. The results of the two threshold effect tests reject the hypothesis that the model has a triple threshold and accept the hypothesis that the model has a double threshold at the significance level of 5%. Therefore, the econometric model is set as a double threshold model in this paper.

Table 12 gives the specific double threshold estimate and its corresponding 95% confidence interval. The threshold estimate is the corresponding γ value when the likelihood ratio statistic LR is equal to zero. Therefore, the double threshold estimates with green fintech as the threshold variable are 0.3296 and 0.6479 in this paper. The likelihood ratio plot in Fig. 4 shows an “inflection point” or “jump,” which indicates that the impact of the data changes significantly around certain values, i.e., the threshold effect exists.

Table 13 shows the estimation results of the threshold model. The results show that before and after the first threshold estimation (0.3296), the impact coefficient of green financial technology on the CEE increase from –0.0164 to 0.278, and the significance level after the threshold value is 1%, indicating a gradually increasing marginal effect. When this threshold is combined with the implementation of green finance policies in reality and the maturity of the green bond market, when the green bond market is still in its initial stage or has a low penetration rate, the effect of green financial technology on improving CEE is relatively limited. At this stage, there are relatively few market participants, and the liquidity of funds and the selection of green investment projects are limited, which limits the influence of green fintech. At this point, the development of green fintech relies more on policy promotion and the establishment of market trust, and its effectiveness may be limited by the level of capital market development, investors’ awareness and the intensity of policy implementation. However, once the green bond market enters the medium development stage, that is, when the degree of coordination of green financial technology exceeds 0.3296, the market mechanism gradually improves, the scale and depth of green investment increase, and the promoting effect of green financial technology significantly improves. At this point, the application of green financial products and technologies has gradually expanded to a wider range of industries and fields. The trust of market participants and technical support has been strengthened. The improvement effect of green financial technology on CEE has begun to emerge, and the marginal effect has gradually increased. This stage of development in the green bond market can be regarded as a crucial period when green fintech gradually plays an important role.

Before and after the second threshold estimation (0.6479), the influence coefficient of green financial technology on CEE decreases from 0.278 to 0.232, indicating that the marginal utility first increases but then decreases, with obvious nonlinear characteristics. This change could correspond to the mechanism of action of green fintech after market maturity is relatively high and the policy environment is stable. As the green bond market matures further, the policy system becomes increasingly complete, the market size continues to expand, and the marginal effect of green financial technology gradually weakens. This is because in a highly saturated market, the improvement benefits of green fintech on CEE start to decline. The green financial tools and technologies in the market gradually become conventional, and their innovative and breakthrough roles gradually weaken. Furthermore, the market has reached a relatively high proportion of green financing. Improvement in the CEE relies more on the comprehensive promotion of technological innovation, industrial structure adjustment and the green transformation of the entire society rather than the single role of fintech.

Therefore, when the degree of coordination of green fintech is greater than 0.3296, green fintech always significantly promotes CEE, especially during the transition process of the green bond market from the initial stage to the mature stage. However, with the development of green financial technology, especially with the further maturation of the market and the continuous advancement of policies, its marginal improvement effect on CEE has gradually weakened. The nonlinear characteristics of green fintech indicate that with the advancement of policies and technologies, its mechanism of action manifests differently at different stages: When the degree of coordination of green fintech is between 0.3296 and 0.6479, the CEE can be significantly improved. However, when market maturity further increases, the role of green fintech tends to weaken, and the effect may decrease or be limited. The impact of green fintech on CEE is complex and phased.

Conclusions and implications

Conclusion

On the basis of the panel data of prefecture-level cities in China from 2011 to 2022, this study systematically investigated the linear and nonlinear effects of green financial technology on CEE by constructing fixed-effect and threshold-effect models. The empirical results show that green fintech significantly improves the CEE by broadening green financing channels, optimizing resource allocation efficiency and driving green investment. Moreover, the deep integration of green innovation and artificial intelligence technology has further unleashed the emission reduction potential of green fintech: green innovation promotes the implementation of environmentally friendly technologies, while artificial intelligence enhances carbon efficiency through precise data analysis and decision optimization. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the carbon reduction effect of green fintech is particularly significant in western regions, non-low-carbon pilot cities, areas with weak digital infrastructure, areas with high coal consumption ratios and areas with low greening level, highlighting its differentiated role under different development stages and resource endowment conditions. Most importantly, the research shows that the improvement effect of green financial technology on carbon efficiency clearly decreases, that is, as its development level increases, the emission reduction effect per unit of investment gradually weakens. In conclusion, green fintech has become an important force in promoting the improvement of CEE. However, its effectiveness is complex and influenced by multiple factors, and its effectiveness needs to be optimized through precise policy design and technological application.

Implications

On the basis of the above conclusions, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations, aiming to provide references for developing countries to increase their CEE and promote sustainable environmental development:

First, green financial technology should be incorporated into the national sustainable development strategy system, and a multilevel green financial tool framework should be established and improved. Developing countries should actively promote the establishment and popularization of special tools such as green funds, green bonds and green loans and focus on guiding funds to flow into key emission reduction areas such as energy, transportation and construction. The government needs to work with financial institutions to build an incentive-compatible regulatory framework and reduce the cost of green investment and financing through mechanisms such as interest subsidies, guarantees and risk compensation. Especially in regions with poor resource endowments and insufficient coverage of traditional finance, the technological advantages of green financial technology should be fully leveraged. By leveraging blockchain and artificial intelligence, the transparency of financing and the efficiency of capital allocation can be enhanced, resulting in the coordinated advancement of environmental protection and economic growth.

Second, the integrated support system of green technological innovation and digital infrastructure should be strengthened. It is suggested that developing countries increase their investment in green technology research and development and the field of renewable energy, with a focus on breaking through technological bottlenecks in areas such as clean energy, energy conservation and consumption reduction. Enterprises and research institutions should be encouraged to jointly develop innovation consortia through policy tools such as tax incentives and research and development subsidies, and the commercial application of green technologies should be accelerated. For the western regions and relatively economically backward areas, differentiated support policies should be formulated to enhance the guidance and empowerment of green financial technology. Low-carbon pilot cities should further deepen the reform and innovation of green finance, focus on technological innovation and institutional integration, and form replicable and scalable transformation models.

Third, a multidimensional and dynamically adjusted carbon reduction policy system should be established. Given the obvious nonlinear characteristics and diminishing marginal law of the green fintech effect, developing countries should avoid overreliance on a single policy tool and instead need to develop a systematic solution that combines policy incentives, market mechanisms and behavioral guidance. It is suggested that a monitoring and evaluation mechanism for the effectiveness of green financial technology be established. Policy priorities should be dynamically adjusted on the basis of the development stage and regional characteristics. In the early stage of technology promotion, basic investment and demonstration guidance should be increased. As the application deepens, the focus should gradually shift to the construction of market mechanisms and institutional optimization to ensure the long-term, stable and sustainable nature of carbon reduction actions. Moreover, through publicity and education as well as consumption guidance, the concept of green and low-carbon throughout society should be cultivated, and a governance pattern featuring multiparty collaboration among technology, policy, the market and society should be formed.

Limitations

Green financial technology has become an important driver of improved CEE and has gained significant attention in recent years. However, the existing research in this area still faces several limitations, particularly related to data availability, the diversity of green financial instruments, and regional differences.

First, the impact of green fintech on carbon efficiency can vary across countries, depending on economic structure, technological capabilities, and policy environments. In regions with low reliance on green financial instruments, particularly in noncapital-intensive cities, the potential impact of green fintech may not be fully realized. Therefore, cross-regional comparisons may not account for the varying levels of green fintech development, leading to biased assessments of its impact.

Second, the diversity of green fintech makes quantifying its effect on carbon efficiency difficult. Different financial instruments, such as green bonds and carbon markets, complicate research methods. The existing quantitative models may not capture the multidimensional role of green fintech, especially given rapid technological changes and complex interactions between financial instruments and environmental policies. The absence of standardized measurement indices adds uncertainty to the assessment of its impact. Furthermore, incomplete statistical data, particularly at the prefecture level in China, limit the depth of research. Green fintech effects require long-term data tracking, but most studies focus on short-term effects and neglect potential long-term effects. Additionally, in regions with developing green finance markets, the lack of sufficient historical data further complicates research.

Finally, green fintech development is strongly influenced by the policy environment. Differences in green policies across regions—such as subsidy policies, carbon pricing, and green taxes—can result in varying effectiveness. However, a lack of detailed policy data means that existing studies often fail to account for these policy differences, which can affect the accuracy of research findings. Therefore, although this study has discussed in depth the impact of green fintech on CEE, it still cannot completely overcome the limitations of insufficient data, cross-border differences, and the diversity of financial instruments. Future research can further improve the overall understanding of the efficiency of green fintech in driving carbon emissions through richer datasets, cross-country comparative studies, and long-term data series tracking.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bakhsh S, Zhang W, Ali K, Anas M (2024) Transition towards environmental sustainability through financial inclusion, and digitalization in China: Evidence from novel quantile-on-quantile regression and wavelet coherence approach. Technol Forecast Soc Change, Elsevier, Vol. 198(C)

Bughio A, Teng Y, Tunio AR et al. (2025) The short- and long-run causal correlation between green finance, renewable energy consumption, and economic growth. Energy Environ 36(2):888–907

Chang L, Moldir M, Zhang Y, Nazar R (2023) Asymmetric impact of green bonds on energy efficiency: fresh evidence from quantile estimation. Utilities Policy, Elsevier, Vol. 80(C)

Chen P, Gao JW, Ji Z, Liang H, Peng Y (2022) Do artificial intelligence applications affect carbon emission performance?—Evidence from panel data analysis of Chinese cities. Energies 15:5730–5730

Dikau S, Volz U (2021) Central bank mandates, sustainability objectives and the promotion of green finance. Ecological economics 184:107022

Ding GX, Kang N (2024) The impact of digital financial inclusion on China’s regional disparities in the quality of economic development: Based on the relational data paradigm. Econ Anal Policy 62:629–651

Du L, Chu W, Cai SH (2012) Economic development and carbon dioxide emissions in China: Provincial panel data analysis. China Econ Rev 2:371–384

Fahy J (2000) The resource‐based view of the firm: some stumbling‐blocks on the road to understanding sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of European industrial training 24:94−104

Fan M, Zhou Y, Lu Z, Gao S (2024) Fintech’s impact on green productivity in China: Role of fossil fuel energy structure, environmental regulations, government expenditure, and R&D investment. Resources Policy 91:104857

Grachev V, Pliamina O (2016) Environmental performance of various methods of electric power generation. Ecol, Environ Conserv 3:1539–1548

Green GC, Hevner AR (2000) The successful diffusion of innovations: Guidance for software development Organizations. IEEE Softw 6:96–103

Hamilton D, Tool MR, Tilman R, Phillips RJ, Troub RM, Boulding KE, ... & Breit W (1977) Science and Ceremony: The Institutional Economics of CE Ayres. J Econ Issues 11: 635-665

Hussain S, Gul R, Ullah S (2023) Role of financial inclusion and ICT for sustainable economic development in developing countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 194:122725

Iftikhar Y, He W, Wang Z (2016) Energy and CO₂ emissions efficiency of major economies: A non-parametric analysis. J Clean Prod 77:779–787

Jiang P, Jiang H, Wu J (2022) Is inhibition of financialization the sub-effect of the green credit policy? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters 47:102737

Jiang W, Wang X, Wu X (2022) Analysis of the impact of ecological innovation and green investment on China’s CO2 emissions. J Environ Public Health 2022:3783985

Jin Y, Gao X, Wang M (2021) The financing efficiency of listed energy conservation and environmental protection firms: evidence and implications for green finance in China. Energy Policy 153:112254

Kerr TM, Avendano F(2020) Green loans and multinational corporations: Financial innovation to deliver sustainability. Nat Resour Environ 2:46–49

Korkut PU, Kartal MT, Zahoor A, Sinha A (2025) Relationship between green bonds and carbon neutrality: Evidence from top five emitting countries’ sectoral CO2 emissions. Financ Innov 1:10–10

Lahouel BB, Taleb L, Zaied YB, Managi S (2022) Business case complexity and environmental sustainability: nonlinearity and optimality from an efficiency perspective. J Environ Manag 301:113870

Le TN-L, Aikins EJ, Tiwari AK (2021) Time and frequency domain connectedness and spill-over among fintech, green bonds and cryptocurrencies in the age of the fourth industrial revolution. Technol Forecast Soc Change 120:382–382

Lee CC, Song HP, An JF (2024) The impact of green finance on energy transition: Does climate risk matter? Energy Econ 107:258

Li Y, Zhou M, Sun H, Liu J (2022) Assessment of environmental tax and green bonds impacts on energy efficiency in the European Union. Econ Change Restruct 2:1063–1081

Liu H, Yao P, Latif S, Aslam S, Iqbal N (2021) Impact of Green financing, FinTech, and financial inclusion on energy efficiency. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 13:18955–18966

Liu M, Zhan M, Liu YP, Zhao M (2024a) Impact of FDI and foreign trade openness on carbon emissions in China: evidence from threshold regression model. Appl Econ 58:8332–8345

Liu Y, Li Z, Chen H, Cui X (2024b) Impact of big data on carbon emissions: Empirical evidence from China’s national big data comprehensive pilot zone. Sustainability 19:8313–8313

Liu Y, Fan C, Xue D (2024c) A review of the effects of urban and green space forms on the carbon budget using a landscape sustainability framework. Sustainability 16:1870

Luo Y, Song K, Ding X, Wu X (2021) Environmental sustainability of textiles and apparel: A review of evaluation methods. Environ Impact Assessment Review 86:106497

Lv TG, Hu H, Zhang XM, Xie HL, Wang L, Fu SF (2022) Spatial spillover effects of urbanization on carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. China Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23:33920–33934

Marra M (2020) High speed rail and China’s new economic geography: Impact assessment from the regional science perspective. Region Stud 4:590–590

Mehmood K, Kautish P, Mehrotra A, Alofaysan H, Papa A (2025) Forging sustainable synergies: Unleashing fintech-driven supply chain collaboration for enhanced green supply chain performance. Technol Forecast Soc Change 219:124244

Meng Y, Yu J, Yu Y, Ren Y (2024) Impact of green finance on green total factor productivity: New evidence from improved synthetic control methods. J Environ Manag 123:394–394

Opoku-Mensah E, Chun W, Ofori EK, Ampofo SA, Chen W, Appiah-Otoo I (2024) Revisiting the role of ICT and green institutional governance in environmental sustainability and proposing an ecological footprint mitigation pathway using a volatility-driven model. J Cleaner Production 434:139824

Prasad M, Mishra T (2017) Low-carbon growth for Indian iron and steel sector: exploring the role of voluntary environmental compliance. Energy Policy 100:41–50

Ran CY, Zhang YR (2023) The driving force of carbon emissions reduction in China: Does green finance work. J Clean Prod 421:138502

Rannou Y, Boutabba MA, Barneto P (2021) Are Green Bond and Carbon Markets in Europe complements or substitutes? Insights from the activity of power firms. Energy Econ 104:105651

Razzaq A, Wang YF, Chupradit S, Suksatan W, Shahzad F (2021) Asymmetric inter-linkages between green technology innovation and consumption-based carbon emissions in BRICS countries using quantile-on-quantile framework. Technol Soc 66:101656

Roy SK, Alam MT, Mojumder P, Mondal I, Kafy AA, Dutta M, Mahtab SB (2024) Dynamic assessment and prediction of land use alterations influence on ecosystem service value: A pathway to environmental sustainability. Environ Sustain Indic 21:100319

Shao J, Lou Z, Wang C, Mao J, Ye A (2022) The impact of artificial intelligence (AI) finance on financing constraints of non-SOE firms in emerging markets. Int J Emerging Markets 17:930−944

Wang S, Ma Y (2018) Influencing factors and regional discrepancies of the efficiency of carbon dioxide emissions in Jiangsu, China. Ecol Indic 90:460–468

Wang S, Chu C, Chen G, Peng Z, Li F (2016) Efficiency and reduction cost of carbon emissions in China: a non-radial directional distance function method. J Clean Prod 62:624–634