Abstract

Based on the data of 2020 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this paper explores the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among 2501 female employees from the perspective of social role theory. Additionally, it examines the mediating role of subjective well-being and the moderating effect of years of education. The results indicate that gender stereotypes among female employees have a negative predictive effect on job satisfaction. Subjective well-being mediates the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction and the mediating effect of subjective well-being is moderated by years of education. Specifically, compared to female employees with lower years of education, those with higher years of education exhibit a stronger positive predictive effect of subjective well-being on their job satisfaction. Therefore, on the path towards gender equality and female career development, it is necessary to comprehensively consider various factors such as improving the workplace environment, enhancing the impact of education, implementing mental health interventions, and fostering a sense of self-awareness, in order to achieve a substantial improvement in female employees’ job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 20th Party Congress report points out that we should implement an employment-first strategy, address employment issues effectively, and promote high-quality and full employment (Cai et al., 2024). Employment is fundamental to people’s livelihood, and job satisfaction has emerged as a crucial indicator for measuring the quality of employment, profoundly influencing employees’ life satisfaction, well-being, and sense of gain. For female employees, the factors influencing job satisfaction are even more complex, as gender stereotypes often expose them to additional challenges in the workplace. Gender beliefs, as a vital component of social culture, exert significant influence on individuals’ career orientations and planning. The traditional cultural ideas of gender inequality, such as “men as the breadwinners and women as the homemakers” and “women are inferior to men,” still have a significant impact on women’s gender perceptions and career development today. Gender equality, which is related to social harmony and economic development, has always been one of the key issues of concern for both academia and governments worldwide (Duflo, 2012; Pervaiz et al., 2023). China has specifically adopted gender equality as a basic national policy, and has been committed to eliminating gender prejudice and discrimination, striving to achieve gender equality in the workplace and other areas of life (Wang, 2015). After years of effort, the concept of gender equality has gradually been widely accepted. As of 2023, China has the highest number of employed women in the world, with a female employment rate of 44.8%. However, gender stereotypes remain deeply ingrained in the workplace (Lin et al., 2023). Women still face numerous challenges, including but not limited to lower labor force participation rates compared to men, limited opportunities for promotion to senior positions, and being among the first to be laid off during economic downturns (Galos and Coppock, 2023; Kim and Oh, 2022). The full realization of gender equality in the workplace remains a long and arduous journey.

Currently, there is a relatively limited amount of direct research on the relationship between gender stereotypes and women’s job satisfaction, with a greater focus on studies examining the connection between gender stereotypes and career development. In a work environment where gender discrimination and stereotypes are intertwined, women encounter numerous obstacles in their career development, with stalled career advancement and a heightened propensity for turnover being typical manifestations. This point is illustrated by the research conducted by Kezar and Acuña (2020), who found that such an environment can severely hinder women’s career development and may even prompt them to consider leaving their jobs. Tabassum and Nayak (2021) reveal that despite the gradual recognition of women leaders in society, deeply ingrained gender stereotypes continue to pose significant obstacles to women’s career advancement and promotion. In addition, parental gender bias in the workplace is also a significant factor influencing women’s career development. Xu et al. (2023) analyzed the impact of parental gender bias on women’s career development in the workplace and found that such bias can lead women to lose their assertiveness in the workplace, ultimately hindering their career progression. In the exploration of the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction, multiple studies have revealed a negative correlation between them. Janssen and Backes-Gellner (2016) point out that women who are employed in traditionally male-dominated occupations tend to have relatively lower job satisfaction. This reflects that, under the influence of occupational gender stereotypes, women encounter numerous discomforts and challenges in non-traditional career fields, which adversely affect their work experiences. The research conclusions of Lup (2018) are more direct. He points out that the existence of gender stereotypes leads women to face the “glass ceiling effect,” which not only limits their career advancement opportunities but also further reduces their job satisfaction. The research by Cortland and Kinias (2019) also indicates that negative gender stereotypes targeting female employees in the workplace hinder women’s ability to gain a sense of achievement and recognition in their work, thereby undermining their job satisfaction. It is evident that gender stereotypes are not only a complex issue deeply rooted in social culture but also a practical challenge that has a profound impact on women’s career development.

Faced with the vast female employment population, how can we further eliminate gender discrimination and prejudice in the employment environment, and thus promote greater gender equality in the Chinese workplace? This is not only a task for the present but also one that requires concerted efforts from both the government and enterprises for a considerable period of time in the future. Although existing studies have explored the relationship between gender stereotypes and female job satisfaction, they still exhibit deficiencies in the following aspects: Firstly, most of the current research focuses on the relationship between gender stereotypes and career development, while relatively few studies have directly examined the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. Secondly, regarding the impact mechanism of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction, particularly the roles of mediating and moderating variables, existing research has not yet fully explored these aspects. Finally, although the role of education in promoting gender equality has been widely acknowledged, there is still a lack of empirical research on how years of education moderate the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. Based on this, this paper relies on the data from the 2020 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) and focuses on the group of female employees. By introducing social role theory, it constructs a theoretical framework to analyze the relationships among gender stereotypes, subjective well-being, years of education, and female job satisfaction, with the aim of deeply exploring the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees. Compared with the existing literature, the main contributions of this paper are as follows: Firstly, by focusing on female employees and utilizing data from the 2020 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this paper provides a novel research perspective for exploring the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among women, thereby enriching the theoretical and practical foundation in this field. Secondly, in terms of potential influence mechanisms, this paper attempts to empirically test the role of two variables, namely years of education and subjective well-being, in the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees. This provides a scientific basis for promoting employee job satisfaction and gender equality.

Gender stereotypes

Gender role refers to the expectations of male and female behavioral patterns within the sociocultural system, reflecting the societal consensus on appropriate behaviors for both sexes in the family, workplace, and society (Abdul Kadir, 2023). Gender stereotypes originate from the differentiation of gender roles (Hentschel et al., 2019) and represent society’s prevalent perceptions or prejudices towards the personality traits, abilities, behaviors, and roles attributed to both sexes (Ellemers, 2018). Whether presented as positive or negative, these stereotypes share the same essential attribute: they can potentially limit individuals’ diverse development and access to opportunities (Kahalon et al., 2018). Among them, the restrictions on women are particularly severe, starting from their student days and continuing throughout their entire career. In the academic field, gender stereotypes may lead to fewer opportunities for women in male-dominated disciplines such as biology, engineering, and mathematics, where they are often perceived as less competent than men, even when their grades and abilities are comparable or superior to those of their male counterparts (Kuteesa et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2023). In the workplace, the impact of gender stereotypes is mainly manifested in unequal access to job opportunities and career advancement for women. During the recruitment process, men are more likely to be welcomed and selected by employers, while women face stricter hiring requirements (Pireddu et al., 2022). In terms of career advancement, gender stereotypes lead to the “glass ceiling” phenomenon, where women face invisible barriers when it comes to promoting to senior positions and leadership roles (Espinosa and Ferreira, 2022). Despite the increase in the number of women in management and their potential for superior job performance compared to men, there are still only a few women who can reach the senior levels of organizations (Balabantaray, 2023; Liu, 2013).

In contemporary China, women are still confronted with multifaceted gender stereotypes. Media and sociocultural influences engage in stereotypical framing of female images, excessively accentuating the prominence of physical appearance and gender roles (Sohu, 2025). Within the family, the label of “virtuous wife and good mother” confines women, and upon becoming mothers, they further confront “motherhood penalty”—enterprises hold biases in recruitment and promotion processes, which impedes women’s career advancement (Chen et al., 2022). In the workplace, both men and women generally perceive that the career field is not an ideal one for women. Female leadership styles are subject to bias, with their decisiveness and decision-making abilities being questioned, making advancement difficult for women (Jennifer and Michael, 2014). Therefore, it is of great practical significance to delve deeply into the relationship between gender stereotypes in China and female employees’ job satisfaction.

Gender stereotypes and job satisfaction

Social role theory provides important theoretical support when exploring the relationship between gender stereotypes and female job satisfaction. According to this theory, society holds different role expectations and behavioral norms for men and women (Gutek et al., 1991). These differences not only shape individuals’ career choices and development paths but also influence their job satisfaction. Gender stereotypes, as an integral part of social role theory, exert a profound influence on women’s job satisfaction by defining the “appropriate” behaviors and work roles for both males and females. Within this theoretical framework, the relationship between gender stereotypes and female job satisfaction becomes particularly complex, influenced by various factors, such as sociocultural contexts, individual psychological states, and workplace environments. In sociocultural terms, traditional gender perceptions emphasize the role allocation of “men as the breadwinners and women as the homemakers,” where women are often viewed as incompetent sexual objects or mere caregivers, or defined solely as mothers who support others or as unattractive “iron ladies.” These stereotypes greatly diminish the image of women as workers and severely hinder their development in the workplace (Wood, 1994). For instance, viewing women as sexual objects may lead to sexual harassment in the workplace (Ward et al., 2023). On the other hand, perceiving them as children or mothers often results in underestimation of their job opportunities and competencies (Dwivedi et al., 2018; Hoffmann and Musch, 2019). In terms of individual psychological states, women may feel pressure due to societal expectations placed upon them. Society expects women not only to fulfill the role of caregivers at home but also to maintain competitiveness in the workplace. When women struggle to balance the demands of work and family, their job satisfaction is often affected as well (Martín-Peña et al., 2023). For instance, women may forgo promotion opportunities due to concerns about conflicting work and family responsibilities, or they may hesitate to accept positions that require long working hours and frequent travel (Goldin, 2021). Furthermore, women may also avoid certain career development opportunities out of fear of not conforming to gender role expectations (Casad et al., 2019). In terms of the workplace environment, the prevalence of gender discrimination often makes women feel disrespected and undervalued, which in turn affects their career development and retention rates (Manzi et al., 2024). Conversely, in a workplace environment free from gender bias and offering equal opportunities, women’s professional growth is promoted, and their job satisfaction increases accordingly (Song, 2022). Based on the aforementioned research, the first hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Gender stereotypes towards female employees have a negative predictive effect on job satisfaction.

The role of subjective well-being

Social role theory also provides a theoretical basis for understanding the mediating role of subjective well-being between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. Subjective well-being refers to individuals’ overall evaluation of their quality of life, encompassing both cognitive and emotional components (Diener, 1984). According to social role theory, when individuals are able to adapt to and fulfill the expectations society places on their roles, they may experience higher levels of subjective well-being, which is consistent with the concept of esteem needs in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This theory posits that when an individual’s need for respect is met, they feel more valuable and confident, which are important factors in enhancing subjective well-being (Hanel et al., 2020; Tay and Diener, 2011). However, for female employees, gender stereotypes in the workplace are prone to triggering role conflicts, causing them to struggle between career aspirations and societal role expectations, which subsequently reduces their subjective well-being and further impacts their job satisfaction (Janssen and Backes-Gellner, 2016). Meanwhile, influenced by societal role positioning, people often hold negative expectations towards women who enter male-dominated fields, and further translate these negative anticipations into gender discrimination. As a result, women’s work capabilities are underestimated, and their achievements are seldom recognized (Begeny et al., 2020; Heilman et al., 2024). This chronic neglect and lack of respect undermine women’s self-esteem and self-confidence, subsequently impacting their subjective well-being.

Modern gender perspectives are crucial in breaking down traditional gender stereotypes, enabling women to free themselves from the psychological burdens and role constraints imposed by outdated notions. As women’s perceptions of gender roles become more modernized, they are able to experience higher levels of subjective well-being. Furthermore, studies have shown a significant positive correlation between subjective well-being and job satisfaction (Prati, 2025; Ray, 2021). Spillover theory posits that attitudes, emotions, skills, and behavioral tendencies exhibited by an individual in one specific domain can naturally extend to other domains. This interaction also applies in reverse situations, and this process can have both positive and negative dual effects (Elf et al., 2019; Henn et al., 2020). According to spillover theory, when an individual feels happy in their personal life, this positive emotional state may transfer to the workplace, thereby enhancing job satisfaction (Judge and Watanabe, 1994; Lee et al., 2021). Therefore, this paper has reason to believe that subjective well-being serves as an important mediator between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees. In other words, gender stereotypes influence job satisfaction through the pathway of subjective well-being, such that lower levels of gender stereotypes can lead to higher levels of subjective well-being. And as subjective well-being increases, so does the level of job satisfaction among female employees. Based on this, the second hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 2: Subjective well-being mediates the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees.

The role of years of education

Exploring the mediating role of subjective well-being in the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction can address the question of “how” gender stereotypes influence female employees’ job satisfaction. However, it does not clarify when the mediating effect is more pronounced. Therefore, the study further introduces years of education as a moderator variable to construct a moderated mediation model, aiming to address the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction, as well as to identify when the mediating effect of subjective well-being is more pronounced.

Years of education, defined as the time span an individual spends within the formal education system from enrollment to the completion of a specific educational stage or the acquisition of an academic qualification, serve as a crucial quantitative indicator for measuring an individual’s level of educational attainment. In China, education has always been highly valued, and the implementation of the imperial examination system made education a pivotal opportunity for ordinary people to change their destinies. “Those who excel in their studies may pursue an official career,” as scholars were able to enter the imperial court and hold governmental positions through outstanding performance in the imperial examinations, thereby achieving social mobility and altering their own fates as well as those of their families (Ko, 2017; Kong et al., 2022). This notion has been passed down through generations, exerting profound and far-reaching influences. Even today, a high level of education is still regarded as a powerful stepping stone to decent and well-paid jobs, as well as a fulfilling and happy life. Conversely, individuals with low educational attainment are often labeled as being destined for “low-paid and undignified jobs” and an “unhappy life.” Therefore, differences in years of education can have a significant impact on individuals’ subjective well-being and job satisfaction.

From a theoretical perspective, there is a positive correlation between educational attainment and subjective well-being (Araki, 2022; Xiong et al., 2024). According to social role theory, education can alter individuals’ perceptions and expectations of gender roles. As the duration of education extends, women are more likely to break free from the constraints of traditional gender roles, pursue their ideal careers, and consequently enhance their sense of well-being (Du et al., 2021; Rivera-Garrido, 2022). Social comparison theory posits that people tend to evaluate their own circumstances by comparing themselves to others (Festinger, 1954). This evaluation forms the psychological basis for individuals’ perception of happiness (Crusius et al., 2022). Individuals with longer durations of education tend to have an advantage in social comparison, are more likely to gain social recognition and respect, and thus experience enhanced subjective well-being. Research in positive psychology similarly confirms that education has a positive effect on enhancing individuals’ well-being. This is attributed to education’s ability to shape human cognition. With the enhancement of cognitive abilities, individuals are better able to regulate their emotions, thereby deeply experiencing well-being at the psychological level (McRae, 2016; Tamir and Mauss, 2011). Compared to those without higher education, individuals with higher education experiences demonstrate higher levels of well-being. Especially among women, the enhancement of well-being after receiving higher education is more pronounced compared to men (Armitage et al., 2024; Nikolaev, 2018).

Meanwhile, there exists a significant positive correlation between subjective well-being and job satisfaction (Prati, 2025). Years of education may influence the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction through the mediating variable of subjective well-being. Previous studies have demonstrated a significant positive correlation between years of education and job satisfaction (Hur et al., 2019; Pita and Torregrosa, 2021) and this finding is equally applicable to the female demographic. Education provides women with a wider array of career options and employment opportunities, enabling them to approach workplace challenges with greater composure and confidence. Additionally, it enhances the likelihood of women ascending to higher occupational tiers (Elsayed and Shirshikova, 2023; Tang, 2023). Women who receive a longer duration of education are more likely to enter diverse industries and fields, achieving remarkable success in traditionally male-dominated domains (Reshi et al., 2022). This enables them to realize their self-worth and significantly enhances their sense of well-being. Conversely, women with lower levels of education find it challenging to break free from the constraints of traditional roles, facing limited access to male-dominated industries. Their value and labor contributions are often overlooked, resulting in compromised well-being. Such disparities in subjective well-being may lead to differential responses among women with varying educational backgrounds when confronted with gender stereotypes, thereby contributing to differences in job satisfaction based on years of education. Although there is currently a relative dearth of research on the moderating role of years of education, based on the aforementioned analysis, it can be inferred that years of education may serve as an important moderating variable, influencing the complex relationships among gender stereotypes, subjective well-being, and job satisfaction. Therefore, the third hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Years of education moderate the second half of the path through which gender stereotypes influence job satisfaction via subjective well-being. Specifically, for female employees with higher years of education compared to those with lower years of education, their subjective well-being has a stronger positive predictive effect on job satisfaction.

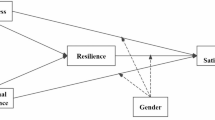

In summary, the theoretical model of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Research design

Data sources and participants

All the data and scales utilized in this paper are sourced from the 2020 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) database. The survey, initiated in 2010, is conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) at Peking University. It involves biennial interviews, and currently, seven rounds of data are available to the public. It employs a stratified multi-stage sampling design, covering 25 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities across China, and has interviewed a total of 14,960 households and 42,590 individuals. Through continuous tracking and recording at the individual, family, and community levels, it comprehensively reveals the dynamic changes in various key areas of China, including social structure, economic development, population mobility, education system, and health status. As a large-scale national social tracking survey project, CFPS provides valuable data resources for studying family and social changes in China. The CFPS encompasses five types of questionnaires: the Family Member Questionnaire, the Household Economy Questionnaire, the Individual Self-Administered Questionnaire, the Child Parent Proxy Questionnaire, and the Individual Proxy Questionnaire. This study selected the Individual Self-Administered Questionnaire, which encompassed the interview information of 28,530 individuals. The research focus of this paper is on the specific group of female employees. After excluding male employees, samples with missing key information, and cases with invalid responses, a total of 2,501 valid samples were obtained, laying a solid data foundation for in-depth exploration of issues related to female employees.

Measures

Dependent variable: job satisfaction (JS)

Internationally, the measurement of job satisfaction mainly follows two approaches: one is the single global rating method, which comprehensively measures employees’ overall satisfaction with their job through a single question; The other is the composite score method, which comprehensively considers various dimensions of job satisfaction and integrates information from these dimensions to form a comprehensive evaluation indicator (Bowling and Zelazny, 2022; Özpehlivan and Acar, 2015). Studies have indicated that the composite score method outperforms the single global rating method in terms of effectiveness (Ironson et al., 1989; Thompson and Phua, 2012). Therefore, this paper uses the composite job satisfaction calculated by the composite score method as a proxy for the dependent variable. In the questionnaire design, the measurement of job satisfaction encompasses five major satisfaction dimensions: income, safety, work environment, work-life balance, and promotion opportunities. Corresponding questions in the questionnaire are set up as follows: “How satisfied are you with the income of this job?”, “How satisfied are you with the safety of this job?”, “How satisfied are you with the working environment of this job?”, “How satisfied are you with the working hours of this job?”, “How satisfied are you with the promotion opportunities of this job?”. Respondents are asked to rate their satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents “very dissatisfied” and 5 represents “very satisfied”. A higher score indicates a higher level of satisfaction. Upon conducting Cronbach’s α test, the internal consistency coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.7, which falls within an acceptable range. This indicates that the scale possesses good internal consistency. In the validity analysis, the indicators utilized include the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value for this scale reached 0.764, and the significance level of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 0.000, which is considerably lower than 0.001. This result provides strong evidence that the scale is appropriate for conducting factor analysis. Subsequently, the scores of the five dimensions are summed and averaged, with the score ranging from 1 to 5. A higher summed score indicates a higher level of job satisfaction among respondents, and conversely, a lower score indicates a lower level of job satisfaction.

Independent variable: gender stereotypes (GS)

Relevant questions are listed in the questionnaire to measure the respondents’ gender stereotypes, specifically: “Men should focus on their careers while women should focus on their families”, “A woman’s success in marriage is more important than her career success”, “A woman’s life is not complete without children”. Respondents are asked to rate their agreement on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represents “Strongly Disagree” and 5 represents “Strongly Agree”. After conducting the Cronbach’s α test, the internal consistency coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.712, which falls within an acceptable range. This indicates that the scale demonstrates good internal consistency. In terms of validity analysis, the KMO value of this scale reached 0.674, and the significance level of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 0.000, significantly lower than 0.001. This result provides strong evidence that the scale is suitable for conducting factor analysis. Subsequently, the scores of these three dimensions are summed, with the total score ranging from 3 to 15. A higher summed score indicates a stronger gender stereotype, meaning that the respondent holds more traditional gender role beliefs; Conversely, a lower summed score indicates a weaker gender stereotype, reflecting more modern and equal gender beliefs held by the respondents.

Control variables

Drawing on the research of Collins et al. (2014) and Terpstra-Tong et al. (2025), the control variables in this paper are set as health status (HS), interpersonal relationships (IR), and social status (SS), with specific measurement methods as follows: Health status is reflected by the question “How do you rate your health status?” (with 1 to 5 representing very healthy to unhealthy, respectively); Interpersonal relationships are assessed by the question “How good are your interpersonal relationships?” (with 0 representing the lowest and 10 representing the highest); Social status is measured by the question “How would you rate your social status in your local community?” (with 1 representing very low and 5 representing very high).

Years of education (YE)

The relevant question in the survey questionnaire is “What is your highest completed (graduated) educational level?”. Respondents are required to select from the following options: illiterate/semi-illiterate, primary school, junior high school, senior high school/technical secondary school/vocational high school, junior college, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctoral degree, and those who have never attended school. Following the approach of Xu et al. (2022), an ordinal ranking and scoring system was applied based on the respondents’ reported educational attainment levels. Specifically, the category of “never attended school/illiterate/semi-illiterate” was assigned a score of 0, primary school education received a score of 6, junior high school education was scored as 9, senior high school or its equivalent was given 12 points, junior college education was awarded 15 points, a bachelor’s degree was assigned 16 points, and a master’s degree or higher was valued at 19 points. In this scoring system, a higher score indicates a longer duration of education received.

Subjective well-being (SWB)

Drawing on the approach of Li et al. (2020), the question “How happy do you feel about yourself?” from the questionnaire is used to measure it. Respondents are required to rate their feelings on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates the lowest level of subjective well-being and 10 represents the highest level of subjective well-being.

Data analysis

In this study, data analysis was conducted using SPSS 27.0 and its macro program PROCESS v4.1. To examine the collinearity of the data, multiple covariance tests were conducted. Consistent with Hayes (2022), Model 4 was used to determine the mediating role of subjective well-being between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction, while Model 14 was employed to construct the moderated mediation effect analysis. To illustrate the differences in years of education, interaction effect plots were created based on −1SD and +1 SD scores of gender stereotypes.

Results

Common method bias test

The Harman’s single-factor test was employed to examine whether there was severe common method bias in the current study (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Using SPSS 27.0, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on all items of the questionnaire. The results indicated that the first common factor explained 25.345% of the variance (<40%), suggesting that there was no severe common method bias in the data from this study.

Multiple covariance analysis

To assess multicollinearity among variables, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were used. Multiple collinearity tests were conducted using SPSS 27.0, and a VIF value greater than 10 indicates high multicollinearity. The results showed that the VIF values for all variables were less than 2, indicating no multicollinearity among the variables.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics revealed that the average score for sample health status was 2.653, the average score for interpersonal relationships was 6.886, and the average score for social status was 2.789. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 1. Firstly, gender stereotypes showed a negative correlation with subjective well-being (r = −0.012), and significant negative correlations with years of education and job satisfaction (r = −0.365, p < 0.01; r = −0.109, p < 0.01); Secondly, subjective well-being exhibited significant positive correlations with both years of education and job satisfaction (r = 0.093, p < 0.01; r = 0.236, p < 0.01); Thirdly, there is a significant positive correlation between years of education and job satisfaction (r = 0.191, p < 0.01).

Main effect test

In order to better reflect the relationship between the gender stereotypes and the job satisfaction, a phased regression approach is adopted in the regression analysis. Firstly, only gender stereotypes are included in the model to examine its relationship with job satisfaction independently. Subsequently, on the basis of the initial model (i.e., Model 1), control variables were incorporated to construct Model 2, with the aim of further examining the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. The regression results are presented in Table 2. The results from Model M1 indicate that gender stereotypes significantly negatively predict job satisfaction (β = −0.109, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis H1 is supported. The results from Model M2 show that after introducing control variables, gender stereotypes still significantly negatively predict job satisfaction (β = −0.145, p < 0.001). This result provides strong support for social role theory to a certain extent, suggesting that female employees are still constrained by traditional social roles in real life. Only those female employees who dare to break through the limitations of traditional social roles and have a lower level of agreement with gender stereotypes can achieve relatively higher job satisfaction.

Mediation effect test

After standardizing all variables, analyze the mediating role of subjective well-being between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. Utilize the SPSS macro program PROCESS developed by Hayes (2022) to conduct a mediation effect test based on Bootstrap, with a sample size of 5000 and a 95% confidence interval. The results indicated that after incorporating control variables, gender stereotypes significantly negatively predicted subjective well-being (β = −0.06, p < 0.001; SE = 0.018; R² = 0.252, F = 210.202, p < 0.001);When both gender stereotypes and subjective well-being were included in the regression model, the results showed that subjective well-being significantly predicted job satisfaction (β = 0.163, p < 0.001; SE = 0.022; R² = 0.100, F = 55.729, p < 0.001). The bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method test indicated (see Table 3) that the total effect of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction was significant, with an effect size of -0.032 and a 95% confidence interval of [−0.183, −0.107]; The direct effect of gender stereotypes on subjective well-being was significant, with an effect size of −0.029 and a 95% confidence interval of [−0.173, −0.098]; The indirect effect of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction through subjective well-being was −0.010, with a 95% confidence interval of [−0.017, −0.003], which did not include zero. This indicated that subjective well-being partially mediated the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. Hypothesis H2 was supported, suggesting that reducing gender stereotypes among female employees can enhance their subjective well-being, which in turn contributes to improving their job satisfaction.

Mediated moderation effect test

To examine whether the latter half of the mediation pathway is moderated by years of education, all variables were standardized, and Model 14 from the PROCESS MACRO was utilized to test for this moderated mediation effect. Testing a moderated mediation model requires estimating the parameters of three regression equations. M3 estimates the overall effect of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction; M4 estimates the predictive effect of gender stereotypes on subjective well-being; M5 estimates the moderating effect of years of education between subjective well-being and job satisfaction. In each equation, control variables are included. If the model estimates meet the following three conditions, then a moderated mediation effect exists. (1) In M3, the overall effect of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction is significant; (2) In M4, the predictive effect of gender stereotypes on subjective well-being is significant; (3) In M5, the main effect of subjective well-being on job satisfaction is significant, and the interaction effect between years of education and subjective well-being is also significant (Hayes, 2013; Wen and Ye, 2014).

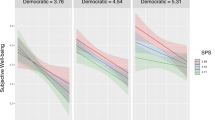

As shown in Table 4, M3 is significant, with gender stereotypes negatively predicting job satisfaction (β = −0.136, p < 0.001), satisfying condition (1); M4 is significant, with gender stereotypes negatively predicting subjective well-being (β = −0.060, p < 0.001), satisfying condition (2); M5 is significant, with subjective well-being positively predicting job satisfaction (β = 0.164, p < 0.001), and the interaction term between years of education and subjective well-being is also significant (β = 0.045, p < 0.01), satisfying condition (3). Furthermore, the effect size of the moderating term is −0.003, with a confidence interval of [−0.006, −0.000]. The interval does not include 0, indicating that the second half of the mediation pathway of subjective well-being is moderated by years of education, so Hypothesis 3 was supported. To more clearly explain the nature of the interaction effect between subjective well-being and years of education, this study divided participants into high and low groups based on the mean plus or minus one standard deviation of years of education. Simple slope tests were conducted and a simple effect analysis diagram (Fig. 2) was plotted. The results indicate that for the high-score group, i.e., female employees with higher years of education, subjective well-being has a stronger positive predictive effect on job satisfaction (B = 0.209, t = 6.685, p < 0.001). For the low-score group, i.e., female employees with lower years of education, the positive predictive effect of subjective well-being on job satisfaction is weakened (B = 0.118, t = 4.751, p < 0.001). Overall, the process through which gender stereotypes influences job satisfaction via subjective well-being is moderated by years of education. For female employees with lower educational attainment, the indirect effect of gender stereotype on job satisfaction, mediated by subjective well-being, has an index value of −0.007(Boot SE = 0.003, 95%CI = [−0.014, −0.002]); For female employees with higher educational attainment, this indirect effect is relatively larger, with an index value of −0.012 (Boot SE = 0.004, 95%CI = [−0.023, −0.005]).

Discussion

Gender stereotypes have a negative predictive effect on job satisfaction among female employees

This study validates Hypothesis 1, which suggests that the lower the degree of agreement among female employees with traditional gender stereotypes such as “women are inferior to men,” the greater the likelihood of their job satisfaction increasing. This conclusion aligns with existing research, which emphasizes that gender stereotypes have a significant and often negative impact on women’s workplace experiences. Heilman (2012) pointed out that gender stereotypes shape societal expectations regarding women’s abilities, and when women are perceived as not possessing the qualities deemed necessary for certain occupations, they encounter numerous obstacles in the workplace. Carpini et al. (2023) further emphasized that gender stereotypes can negatively impact women’s job satisfaction by influencing their self-perception and others’ evaluations of them. The underlying reason may lie in the fact that women have long been influenced by the outdated notion that “a woman without talent is virtuous,” which often confines them to the domestic sphere, preventing their talents from being fully realized (Liang, 2024; Qiu, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Even when women courageously step out of their domestic spheres and enter the workforce, they often struggle to escape the shadow of gender stereotypes. The less positive attitudes held by male colleagues towards their abilities can lead women to unconsciously underestimate their own capabilities and worth. When confronted with various workplace challenges, they exhibit lower levels of confidence and self-efficacy, and are reluctant to step into more competitive male-dominated roles. Instead, they tend to opt for relatively “feminine” roles that are perceived as less demanding, while reluctantly finding themselves in male-dominated work environments (Martin and Barnard, 2013). Conversely, when women courageously break free from the constraints of traditional gender roles, they are able to embrace more flexible gender role norms and experience a reduction in “work-family conflict” (Townsend et al., 2024). At this juncture, their mindset also becomes more positive. This newfound confidence and resilience enable them to navigate the workplace with greater ease and self-assurance, thereby enhancing their job satisfaction (Orkibi and Brandt, 2015).

Subjective well-being mediates the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction of female employees

This study validates Hypothesis 2, which suggests that the lower the degree of agreement among female employees with gender stereotypes, the more effectively it can enhance their subjective well-being, thereby promoting an increase in job satisfaction. Subjective well-being is not only a crucial indicator for measuring individual quality of life but also an important factor influencing the improvement of job satisfaction among female employees (Skevington and Böhnke, 2018; Buecker et al., 2023). In the workplace, female employees who hold a high level of endorsement of gender stereotypes are often profoundly influenced by traditional notions. This leads to frequent conflicts between their work and family responsibilities, significantly diminishes their well-being, and restricts their career choices. For instance, when women opt for family-friendly paid employment, they often encounter undervaluation of their work, lower remuneration, and hindered career advancement (Huang and Gamble, 2015). Such unfair circumstances may prompt them to resign and seek opportunities in different organizations. This, in turn, can have a detrimental impact on their mental health and well-being, thereby impeding the enhancement of their job satisfaction (Elçi et al., 2021). Conversely, for female employees who have a low level of endorsement of gender stereotypes, this low endorsement can enhance their self-efficacy and subjective well-being (Weiss et al., 2012). When confronted with challenges, they are able to maintain a high level of self-efficacy. This positive mindset not only bolsters their subjective well-being but also, through the enhancement of well-being, exerts a positive influence on their job performance and career advancement.

The mediating role of subjective well-being is moderated by years of education

Specifically, for female employees with longer educational experiences, the positive predictive effect of their subjective well-being on job satisfaction is particularly significant. This study validates Hypothesis 3. According to in-depth research in positive psychology, years of education not only represent the accumulation of knowledge but also serve as a means of honing emotional intelligence and self-regulation abilities (Pluskota, 2014; Duan et al., 2020). As the years of education increase, female employees gradually acquire more effective emotion management skills. This enables them to maintain a more positive mindset when facing work challenges and workplace pressures, thereby more deeply experiencing the true meaning of happiness. More importantly, according to social comparison theory, individuals evaluate their own circumstances by comparing themselves with others (Festinger, 1954) in order to gain self-esteem and a sense of fulfillment. Higher education is often seen as a symbol of professional competence and work ethics. Compared to women without higher education, those with a higher educational background are in a more advantageous position in social comparison and are more likely to gain social recognition and respect. This not only enables them to enter more diversified professional fields but also grants them the opportunity to vie for higher-level positions and secure higher salaries (Zhang and Zhu, 2024). Such external affirmation undoubtedly enhances their sense of well-being, which in turn elevates their job satisfaction.

Conclusion

In the dual context of promoting high-quality and sufficient employment and the increasing awakening of women’s self-awareness, it is of great significance to explore the impact of gender stereotypes on female employees’ job satisfaction. Based on individual-level data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in 2020 and a comprehensive review of relevant academic literature, this paper delves into the complex relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees, relying on social role theory. Furthermore, it elaborates on how gender stereotypes specifically influence job satisfaction from the two crucial dimensions of subjective well-being and years of education. The main findings are as follows: Gender stereotypes among female employees have a significant negative predictive effect on job satisfaction. Subjective well-being mediates the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees. The indirect effect of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction through subjective well-being is moderated by years of education. Specifically, compared to female employees with lower years of education, the indirect effect is more pronounced among those with higher years of education.

From the theoretical level, this study deepens the understanding of the relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction. This study is the first to explicitly identify subjective well-being as a mediating variable between gender stereotypes faced by female employees and their job satisfaction. Although previous studies have extensively explored gender stereotypes and job satisfaction separately, they have seldom delved deeply into the underlying psychological mechanisms between the two. Through empirical analysis, this study reveals how the reduction of gender stereotypes faced by female employees indirectly influences job satisfaction via psychological mechanisms. This finding not only enriches the understanding of the pathways through which gender stereotypes affect job satisfaction but also offers a new theoretical framework for subsequent research, encouraging scholars to pay more attention to the impact of gender stereotypes on individuals’ psychological aspects and how such psychological influences further extend into the work domain. Furthermore, this paper innovatively introduces years of education as a moderating variable into the relationship model of “gender stereotypes → subjective well-being → job satisfaction”, and delves deeply into its specific mechanism of action in the mediating effect of subjective well-being. This move not only deepens the understanding of the complex relationships among various variables but also provides a new theoretical perspective for comprehending the role of education in the fields of gender equality and workplace satisfaction. Previous studies often regarded education as an independent influencing factor. In contrast, this study places it within a more complex theoretical model, revealing the significant role of years of education in mitigating the negative impacts of gender stereotypes, enhancing subjective well-being, and improving job satisfaction. This finding not only enriches the theoretical research in the fields of gender equality and job satisfaction but also further highlights the immense potential of education in promoting gender equality and enhancing female employees’ workplace well-being.

From the methodological level, this study utilizes individual-level data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in 2020 and validates the relationships among gender stereotypes, subjective well-being, years of education, and job satisfaction through rigorous empirical analysis. This empirical study based on large-scale data not only enhances the reliability and generalizability of the research results but also provides methodological insights for research in related fields. Additionally, this study constructs a clear research framework and hypothesis system through detailed literature reviews and theoretical derivations, providing a reproducible research pathway for subsequent researchers.

This paper not only deepens our understanding of the complex relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction but also provides valuable practical guidance for promoting gender equality and women’s career development. Specifically, this paper finds that there is a significant direct impact between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees, and that gender stereotypes also exert indirect effects through various pathways. Therefore, on the path towards pursuing gender equality and women’s career development, it is necessary to comprehensively consider various factors such as improving the workplace environment, enhancing the impact of education, intervening in mental health, and cultivating a sense of self-awareness, in order to achieve a substantial increase in female employees’ job satisfaction. Firstly, it is crucial to create a workplace environment free from gender bias and discrimination, ensuring fairness and transparency in key areas such as recruitment and promotion. Talent selection should be strictly based on competence, experience, and potential to ensure that every employee enjoys equal opportunities in their career development path. In terms of remuneration, the principle of equal pay for equal work must be strictly adhered to. Moreover, it is imperative to ensure comprehensive safety measures in the workplace, such as conducting regular maintenance and upgrades of hardware facilities. Meanwhile, it is essential to foster a harmonious and equitable work atmosphere through initiatives such as implementing employee care programs. It is also of paramount importance to arrange working hours reasonably to avoid excessive overtime and unreasonable work schedules. Only in this way can female employees be provided with a platform to fully demonstrate their capabilities, promote the joint development of enterprises and employees. Secondly, education is the key to breaking down gender barriers and promoting women’s advancement (Daraz et al., 2024). From a macro perspective, it is crucial to ensure that women have equal educational opportunities and outcomes as men at all educational stages, guaranteeing that women can access longer periods of education and thereby enhancing their overall years of schooling. In the specific practice of schools, it is essential to optimize curriculum design to avoid gender stereotypes embedded in course content. Additionally, gender equality education should be comprehensively implemented in schools through diverse forms such as classroom teaching and social practice, enabling female students to recognize that women can achieve outstanding accomplishments in various fields, thereby promoting the awakening of their self-awareness. Through these measures, a solid foundation can be laid for women’s future career development, fostering the cultivation of more female talents who possess innovative spirits and a strong sense of social responsibility. Furthermore, the enhancement of female employees’ subjective well-being plays a crucial role in improving their job satisfaction, and the improvement of subjective well-being is inseparable from good mental health (Diener et al., 2017). Employers should attach great importance to mental health interventions for female employees, regarding them as a crucial component of enterprise human resource management. On the one hand, systematic mental health training should be provided to help female employees acquire methods and skills to cope with workplace stress. On the other hand, services such as anonymous hotlines or psychological counseling should be established to offer female employees a safe and confidential channel for venting their feelings, enabling them to promptly release work-related stress and negative emotions. Through these initiatives, female employees can be assisted in effectively coping with workplace stress, enhancing their psychological resilience, and consequently improving their job satisfaction. Lastly, as the subjects perceiving job satisfaction, female employees should establish positive self-cognition and avoid “self-limiting beliefs.” Female employees should recognize their own abilities and value, dare to challenge the constraints of traditional gender roles, and actively pursue their career goals. Meanwhile, they should uphold the principles of self-respect, self-confidence, self-reliance, and self-improvement, discarding outdated notions such as “it’s better to marry well than to do well in one’s career.” continuously enhance their professional skills and comprehensive qualities, and strengthen their competitiveness in the workplace. In addition, female employees should dare to say “no” to any form of gender bias and discrimination in the workplace, resolutely safeguarding their dignity and rights. In this way, it can not only enhance their own job satisfaction and career development, but also contribute to the process of achieving gender equality in society.

However, it needs to be emphasized that this study has certain limitations. Firstly, although the CFPS data has high representativeness and authority, the timing and scope of its data collection may limit the comprehensiveness of the study. Future research could consider incorporating data from other time periods or geographical regions to more comprehensively capture the dynamic factors influencing female employees’ job satisfaction. Secondly, although this paper introduces subjective well-being and years of education as mediator and moderating variables, the formation of job satisfaction is a complex process involving factors at multiple levels. Therefore, this study may not have covered all important variables. Future research can further explore other potential variables, such as family support and organizational culture, to build a more comprehensive theoretical model. Lastly, this study mainly focuses on the situation of female employees in China, and whether the findings are applicable to female employees in other cultural backgrounds and regions still requires further verification. Future research can undertake cross-cultural comparisons to explore the universality and particularity of the impact of gender stereotypes on job satisfaction.

Data availability

Data is available in the supplementary materials or upon the request to the corresponding author.

References

Abdul Kadir NB (2023) Gender roles: cultural considerations. In: Shackelford TK (eds) Encyclopedia of sexual psychology and behavior. Springer, Cham, p 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_251-1

Araki S (2022) Does education make people happy? Spotlighting the overlooked societal condition. J Happiness Stud 23(2):587–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00416-y

Armitage JM, Wootton RE, Davis OSP et al. (2024) An exploration into the causal relationships between educational attainment, intelligence, and wellbeing: an observational and two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. Npj Ment Health Res 3(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-024-00066-x

Balabantaray SR (2023) Women’s leadership and sustainable environmental initiatives: a macroscopic investigation from ecofeminism framework. Int J Multidiscip Res Growth Eval 4(4):1039–1046

Begeny CT, Ryan MK, Moss-Racusin CA et al. (2020) In some professions, women have become well represented, yet gender bias persists—perpetuated by those who think it is not happening. Sci Adv 6(26):eaba7814. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba7814

Bowling N, Zelazny L (2022) Measuring general job satisfaction: which is more construct valid—global scales or facet-composite scales? J Bus Psychol 37:91–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09739-2

Buecker S, Luhmann M, Haehner P et al. (2023) The development of subjective well-being across the life span: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 149(7-8):418–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000401

Cai Y, Liu S, Zhang X (2024) The digital economy and job quality: facilitator or inhibitor?-Evidence from micro-individuals. Heliyon 10(4):e26536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26536

Carpini JA, Luksyte A, Parker SK et al. (2023) Can a familiar gender stereotype create a not‐so‐familiar benefit for women? Evidence of gendered differences in ascribed stereotypes and effects of team member adaptivity on performance evaluations. J Organ Behav 44(4):590–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2702

Casad BJ, Petzel ZW, Ingalls EA (2019) A model of threatening academic environments predicts women STEM majors’ self-esteem and engagement in STEM. Sex Roles 80:469–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0942-4

Chen WQ, Zhong YQ, Xiong JY (2022) Work or family? A glimpse into the predicament of “motherhood punishment” for women. https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20220402A01HZO00. Accessed 22 Apr 2022

Collins BJ, Burrus CJ, Meyer RD (2014) Gender differences in the impact of leadership styles on subordinate embeddedness and job satisfaction. Leadersh Quart 25(4):660–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.02.003

Cortland CI, Kinias Z (2019) Stereotype threat and women’s work satisfaction: the importance of role models. Arc Sci Psychol 7(1):81–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/arc0000056

Crusius J, Corcoran K, Mussweiler T (2022) Social comparison: theory, research, and applications. In: Theories in social psychology 2nd edn. Wiley, New York, p 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394266616.ch7

Daraz U, Hussain Z, Ibrahim et al. (2024) Breaking barriers, building futures: the transformative impact of education on women’s empowerment in Malakand division, Pakistan. Int Res J Soc Sci Hum 3(2):92–119

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 95(3):542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener E, Pressman SD, Hunter J et al. (2017) If, why, and when subjective well‐being influences health, and future needed research. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 9(2):133–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12090

Du H, Xiao Y, Zhao L (2021) Education and gender role attitudes. J Popul Econ 34(2):475–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00793-3

Duan W, Chen Z, Ho SMY (2020) Positive education: theory, practice, and evidence. Front Psychol 11:427. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00427

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. J Econ Lit 50(4):1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051

Dwivedi P, Joshi A, Misangyi VF (2018) Gender-inclusive gatekeeping: how (mostly male) predecessors influence the success of female CEOs. Acad Manag J 61(2):379–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1238

Elçi M, Sert-Özen A, Murat-Eminoğlu G (2021) Perceived gender discrimination and turnover intention: the mediating role of career satisfaction. In: Mehtap O (Ed) New strategic, social and economic challenges in the age of society 5.0 implications for sustainability, vol 121. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. European Publisher, London, p 64–76. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.04.8

Elf P, Gatersleben B, Christie I (2019) Facilitating positive spillover effects: new insights from a mixed-methods approach exploring factors enabling people to live more sustainable lifestyles. Front Psychol 9:2699. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02699

Ellemers N (2018) Gender stereotypes. Annu Rev Psychol 69(1):275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

Elsayed A, Shirshikova A (2023) The women-empowering effect of higher education. J Dev Econ 163:103101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103101

Espinosa MP, Ferreira E (2022) Gender implicit bias and glass ceiling effects. J Appl Econ 25(1):37–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2021.2007723

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Galos DR, Coppock A (2023) Gender composition predicts gender bias: a meta-reanalysis of hiring discrimination audit experiments. Sci Adv 9(18):eade7979. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade7979

Goldin C (2021) Career and family: women’s century-long journey toward equity. Princeton University Press, Princeton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691226736

Gutek BA, Searles, Klepa L (1991) Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. J Appl Psychol 76(4):560–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560

Hanel PHP, Wolfradt U, Wolf LJ et al. (2020) Well-being as a function of person-country fit in human values. Nat Commun 11(1):5150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18831-9

Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York

Hayes AF (2022) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications, New York

Heilman ME (2012) Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res Organ Behav 32:113–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.003

Heilman ME, Caleo S, Manzi F (2024) Women at work: pathways from gender stereotypes to gender bias and discrimination. Annu Rev Organ Psych 11(1):165–192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-110721-034105

Henn L, Otto S, Kaiser FG (2020) Positive spillover: the result of attitude change. J Environ Psychol 69:101429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101429

Hentschel T, Heilman ME, Peus CV (2019) The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes: a current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves. Front Psychol 10:11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

Hoffmann A, Musch J (2019) Prejudice against women leaders: Insights from an indirect questioning approach. Sex Roles 80:681–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0969-6

Huang Q, Gamble J (2015) Social expectations, gender and job satisfaction: front-line employees in China’s retail sector. Hum Resour Manag J 25(3):331–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12066

Hur H, Maurer JA, Hawley J (2019) The role of education, occupational match on job satisfaction in the behavioral and social science workforce. Hum Resour Dev Q 30(3):407–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21343

Ironson GH, Smith PC, Brannick MT et al. (1989) Construction of a job in general scale: a comparison of global, composite, and specific measures. J Appl psychol 74(2):193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.2.193

Janssen S, Backes-Gellner U (2016) Occupational stereotypes and gender-specific job satisfaction. Ind Relat 55(1):71–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12126

Jennifer Z, Michael T (2014) Advancing gender parity in China: solutions to help women’s ambitions overcome the obstacles. https://www.bain.com/insights/advancing-gender-parity-in-china/. Accessed 25 Nov 2014

Judge TA, Watanabe S (1994) Individual differences in the nature of the relationship between job and life satisfaction. J Occup Organ Psych 67(2):101–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1994.tb00554.x

Kahalon R, Shnabel N, Becker JC (2018) Positive stereotypes, negative outcomes: reminders of the positive components of complementary gender stereotypes impair performance in counter‐stereotypical tasks. Br J Soc Psychol 57(2):482–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12240

Kezar A, Acuña AL (2020) Gender inequality and the new faculty majority. The Wiley handbook of gender equity in higher education (eds NS Niemi, MB Weaver-Hightower). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119257639.ch6

Kim CH, Oh B (2022) Taste-based gender discrimination in South Korea. Soc Sci Res 104:102671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102671

Ko KH (2017) A brief history of imperial examination and its influences. Society 54(3):272–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0134-9

Kong X, Zhang X, Yan C et al. (2022) China’s historical imperial examination system and corporate social responsibility. Pac-Basin Financ J 72:101734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101734

Kuteesa KN, Akpuokwe CU, Udeh CA (2024) Gender equity in education: addressing challenges and promoting opportunities for social empowerment. Int J Appl Res Soc Sci 6(4):631–641. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i4.1034

Lee DW, Hong YC, Seo H et al. (2021) Different influence of negative and positive spillover between work and life on depression in a longitudinal study. Saf Health Work-Kr 12(3):377–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2021.05.002

Li L, Zhang Z, Fu C (2020) The subjective well-being effect of public goods provided by village collectives: evidence from China. PLoS One 15(3):e0230065. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230065

Liang B (2024) Cultural sources of gender gaps: confucian meritocracy reduces gender inequalities in political participation. Elect Stud 91:102848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102848

Lin GL, Shi JN, Wang YQ et al. (2023) Advancing gender equality in the Chinese workplace. https://www.doc88.com/p-39529442082961.html. Accessed 21 July 2023

Liu S (2013) A few good women at the top: the China case. Bus Horiz 56(4):483–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2013.04.002

Lup D (2018) Something to celebrate (or not): the differing impact of promotion to manager on the job satisfaction of women and men. Work Employ Soc 32(2):407–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017713932

Manzi F, Caleo S, Heilman ME (2024) Unfit or disliked: how descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes lead to discrimination against women. Curr Opin Psychol 60:101928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101928

Martin P, Barnard A (2013) The experience of women in male-dominated occupations: a constructivist grounded theory inquiry. Sa J Ind Psychol 39(2):1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1099

Martín-Peña ML, Cachón-García CR, De Vicente y Oliva MA (2023) Determining factors and alternatives for the career development of women executives: a multicriteria decision model. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01936-z

McRae K (2016) Cognitive emotion regulation: a review of theory and scientific findings. Curr Opin Behav Sci 10:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.004

Nikolaev B (2018) Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? J Happiness Stud 19:483–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9833-y

Orkibi H, Brandt YI (2015) How positivity links with job satisfaction: preliminary findings on the mediating role of work-life balance. Eur J Psychol 11(3):406–418. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i3.869

Özpehlivan M, Acar AZ (2015) Assessment of a multidimensional job satisfaction instrument. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 210:283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.368

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY et al. (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Peng AY, Hou JZ, KhosraviNik M et al. (2023) She uses men to boost her career”: Chinese digital cultures and gender stereotypes of female academics in Zhihu discourses. Soc Semiot 33(4):750–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2021.1940920

Pervaiz Z, Akram S, Ahmad Jan S et al. (2023) Is gender equality conducive to economic growth of developing countries? Cognit Soc Sci 9(2):2243713. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2243713

Pireddu S, Bongiorno R, Ryan MK et al. (2022) The deficit bias: candidate gender differences in the relative importance of facial stereotypic qualities to leadership hiring. Br J Soc Psychol 61(2):644–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12501

Pita C, Torregrosa R (2021) Education and job satisfaction. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21579.72481

Pluskota A (2014) The application of positive psychology in the practice of education. SpringerPlus 3:147. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-147

Prati G (2025) Is job satisfaction related to subjective well-being? Causal inference from longitudinal data. Appl Res Qual Life 20:133–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10400-2

Qiu R (2023) Traditional gender roles and patriarchal values: critical personal narratives of a woman from the Chaoshan region in China. New Dir Adult Con Educ 2023(180):51–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20511

Ray TK (2021) Work related well-being is associated with individual subjective well-being. Ind health 60(3):242–252. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2021-0122

Reshi IA, Sudha DT, Dar SA (2022) Women’s access to education and its impact on their empowerment: a comprehensive review. Morfai J 1:446–450. https://doi.org/10.54443/morfai.v1i2.760

Rivera-Garrido N (2022) Can education reduce traditional gender role attitudes? Econ Educ Rev 89:102261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102261

Skevington SM, Böhnke JR (2018) How is subjective well-being related to quality of life? Do we need two concepts and both measures? Soc Sci Med 206:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.005

Sohu (2025) 2025 content analysis of gender representation in advertising in China 2025 (English Version). https://gov.sohu.com/a/899387680_121649899. Accessed 28 May 2025

Song JM (2022) Female senior managers and the gender equality environment: evidence from South Korean firms. Pac -Basin Financ J 75:101838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101838

Tabassum N, Nayak BS (2021) Gender stereotypes and their impact on women’s career progressions from a managerial perspective. IIM Koz Soc Manag Rev 10(2):192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975220975513

Tamir M, Mauss IB (2011) Social cognitive factors in emotion regulation: Implications for well-being. In: Nyklíček I, Vingerhoets A, Zeelenberg M (eds) Emotion Regulation and Well-Being. Springer, New York, p 31–47

Tang Z (2023) The effects of education upward mobility on income upward mobility: evidence from China. Econ Res-Ekonomska Istraživanja 36(1):2119424. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2119424

Tay L, Diener E (2011) Needs and subjective well-being around the world. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(2):354. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023779

Terpstra‐Tong JLY, Treviño LJ, Yaman AC et al. (2025) Gender composition at work and women’s career satisfaction: an international study of 35 societies. Hum Resour Manag J 35(2):397–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12570

Thompson ER, Phua FTT (2012) A brief index of affective job satisfaction. Group Organ Manag 37(3):275–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601111434201

Townsend CH, Kray LJ, Russell AG (2024) Holding the belief that gender roles can change reduces women’s work–family conflict. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 50(11):1613–1632. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231178349

Wang HQ (2015) Implement the basic state policy of gender equality write a new chapter in the development of Chinese women. https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2015-09/24/nw.D110000gmrb_20150924_1-08.htm. Accessed 24 Sep 2015

Ward LM, Daniels EA, Zurbriggen EL et al. (2023) The sources and consequences of sexual objectification. Nat Rev Psychol 2(8):496–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00192-x

Weiss D, Freund AM, Wiese BS (2012) Mastering developmental transitions in young and middle adulthood: the interplay of openness to experience and traditional gender ideology on women’s self-efficacy and subjective well-being. Dev Psychol 48(6):1774–1784. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028893

Wen ZL, Ye BJ (2014) Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: competitors or backups? Acta Psychol Sin 46(5):714–726. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714

Wood JT (1994) Gendered lives: communication, gender, and culture. Wadsworth Pub, Belmont

Xiong X, Hu RX, Ning W (2024) The relationship between educational attainment, lifestyle, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults: a longitudinal survey from 2012 to 2020. Front Public Health 12:1480050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1480050

Xu H, Zhou H, Xu Y (2022) Development of educational attainment and gender equality in China: new evidence from the 7th National Census. China Popul Dev Stud 6(4):425–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00122-z

Xu M, Liu B, Xu Z (2023) Lost radiance: Negative influence of parental gender bias on women’s workplace performance. Acta Psychol Sin 55(7):1148–1159. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2023.01148

Zhang L, Zhang Y, Cao R (2022) Can we stop cleaning the house and make some food, Mum? A critical investigation of gender representation in China’s English textbooks. Linguist Educ 69:101058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101058

Zhang L, Zhu J (2024) Can higher education improve egalitarian gender role attitudes? Evidence from China. China Econ Rev 88:102311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2024.102311

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY was responsible for research design and literature review; ZL for drafting the initial manuscript; KQ for translation and editing; and YS for data collection and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was formally submitted for review to the Institutional Review Board at Liaoning Normal University. Upon assessment, and considering that the present study involving only the analysis of preexisting, fully anonymized data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), does not involve sensitive information, poses no more than minimal risk to participants and all the procedures adhere to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the committee officially granted an exemption from ethical approval on January 2, 2025 (NO: LL2025003).

Informed consent

The data used in the study were obtained from a fully anonymized public database from which all personally identifiable information had been removed. We had no access to any identifiable personal information and it was impossible to contact the original subjects. Obtaining informed consent was therefore impracticable. Given the nature of the research, the waiver of informed consent does not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Zhu, L., Kang, Q. et al. The relationship between gender stereotypes and job satisfaction among female employees: the role of years of education and subjective well-being. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1913 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06181-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06181-0