Abstract

The digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) has become a vital strategy for sustaining cultural diversity in the face of globalization and digital transformation. This study employs bibliometric analysis and CiteSpace visualization tools to examine 798 research articles from the Web of Science (WoS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases (2006–2024). It provides a systematic comparative analysis of methodologies and paradigms in ICH digitization across Chinese and Western academic discourses. The findings reveal distinct conceptual orientations: Western research tends to be technology-centric, emphasizing virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and blockchain for heritage data modeling, digital archiving, and virtual exhibitions. In contrast, Chinese research adopts a culture–technology symbiosis approach, focusing on digital storytelling, with an emphasis on tourism-integrated innovation, community participation, and interdisciplinary collaboration. A temporal analysis highlights digital twins and artificial intelligence (AI) as emerging transformative forces shaping global ICH preservation, integrating technological advancements with cultural imperatives. To address existing gaps, this study proposes a technology–culture–community synergy framework, fostering a holistic and inclusive approach to ICH digitization. By bridging technological rationality with humanistic values, this study contributes to comparative ICH digitization discourse and provides practical guidance for building inclusive digital ecosystems. Ultimately, it contributes to global heritage discourse by redefining digital technology not only as a preservation tool but also as a driver of cultural innovation, offering a strategic roadmap for balancing technological advancement with the ontological integrity of intangible heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has been over two decades since UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003 (Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage 2003, Kurin, 2004; UNESCO, 2020), a pivotal document established to strengthen international cooperation and legal safeguards for the global protection of ICH (Federico Lenzerini, 2011; Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage, 2012). This convention has provided a solid legal foundation for safeguarding cultural diversity worldwide, offering frameworks and guidelines for nations to implement protective measures (Marilena Vecco, 2010). With evolving societal dynamics and the growing emphasis on ICH preservation across countries, there is an urgent need to integrate ICH development and application with modern information technologies (Ma and Guo, 2024). However, a systematic theoretical framework and actionable guidelines for global implementation remain absent.

This study investigates global scholarly research hotspots and emerging trends in the digitalization of ICH, with a particular focus on the divergent priorities and implementation strategies adopted in Chinese and Western academic traditions (Dimmock, 2020). Despite growing international attention, existing literature lacks a systematic framework to account for the cultural, political, and epistemological differences that shape digital preservation practices across regions. This raises critical questions: In what ways do Chinese and Western paradigms diverge in practice, and what common challenges do they encounter in digitizing ICH? Addressing these questions, this study aims to bridge this gap by offering a comparative analysis of digital ICH approaches, thereby contributing both theoretical insights and practical recommendations.

Digitalization of Intangible Cultural Heritage refers to the systematic recording (Hou Yumeng et al. 2022), preservation, and dissemination of ICH through modern digital technologies such as 3D scanning (Huang & Wong, 2019), VR, AR, and big data analytics (Zhou et al. 2019). Unlike traditional physical preservation methods, digitalization not only achieves static conservation but also expands the reach of ICH through interactive and dynamic displays (Zhang et al. 2018), fostering cross-temporal and cross-spatial cultural transmission and innovation (Schneider, 2011). Technologies like 3D scanning and virtual exhibitions have been widely applied in the protection and presentation of cultural heritage (Fabio Bruno et al. 2010; Boboc et al. 2022), significantly enhancing the precision and interactivity of their display. Meanwhile, the establishment of digital platforms transcends geographical and temporal constraints (Stallkamp and Schotter, 2021), enabling global audiences to access and experience cultural heritage conveniently (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 1998). The advancements in ICH digitalization hold profound significance for cultural preservation and transmission, while also opening new avenues for development in cultural and creative industries, education, tourism, and other sectors (Sun et al. 2024). It drives innovation in cultural industries, promotes the sustainable development of heritage (Aririguzoh, 2022), and provides new pathways and platforms for global cultural exchange and mutual understanding.

Digitalization of ICH has gained global momentum, with countries and regions actively adopting modern digital technologies to advance the preservation and transmission of ICH (Stefano, 2021a). While some progress has been achieved, the continuous evolution of technology and growing demands for cultural safeguarding necessitate deeper exploration into ICH digitalization (Hu et al. 2024a).

A prominent example of Western ICH digitalization is the Europeana platform, a pan-European initiative that emphasizes open access, decentralized contribution, and community-driven metadata enrichment. Europeana promotes “digitization as democratization,” where local archives, grassroots organizations, and individuals contribute to heritage collections. Its emphasis on multilingual metadata, creative reuse, and open licensing embodies a participatory digital ethos, aligning with broader European values of cultural pluralism, digital democracy, and user co-curation.

In contrast, China’s Palace Museum Digital Platform represents a top-down model driven by national cultural institutions. It utilizes high-end technologies such as VR/AR, digital twins, and 3D reconstructions to restore historical scenes, reanimate court life, and integrate traditional esthetics into immersive user experiences. The project is part of a wider strategy of “cultural self-confidence” (wenhua zixin) and state-led digital cultural branding, highlighting a centralized approach that prioritizes cultural continuity, symbolic authority, and curated national narratives. Rather than focusing on open access, the emphasis lies in narrative control, visual fidelity, and experiential depth—rooted in heritage diplomacy and cultural revitalization goals.

These two platforms exemplify deeper divergences in how heritage digitization is conceptualized: the West often foregrounds civic participation and digital commons, while China integrates digitalization into a broader framework of cultural policy, national identity construction, and narrative control. Such contrasts are not merely technological but embedded in differing epistemologies, governance structures, and societal expectations of what heritage should do in the digital age. For instance, CNKI literature frequently highlights concepts like “cultural confidence,” “red tourism,” and “folk identity”, while WOS-indexed research more often discusses “digital storytelling,” “user-centered design,” and “VR immersion”, reflecting distinct conceptual orientations.

Current research in this field primarily focuses on the following areas: (1) application and innovation of digital technologies (Chen C and Huang Y, 2020); (2) development of digital platforms and virtual museums for ICH (Alivizatou, 2019; Zihan Xu and Zhangmin Li, 2025); (3) data management and preservation mechanisms (Xudi, 2024); (4) socio-cultural impacts of ICH digitalization (Chung, 2024); (5) integration of ICH digitalization with cultural and creative industries (Dang et al. 2021); and (6) challenges and prospects of ICH digitalization (Hu et al. 2024a).

However, there remains a lack of systematic analysis that comprehensively compares research trends, hotspots, and trajectories between China and other countries. Despite differences in cultural systems and socio-political contexts, such comparative studies could provide robust theoretical foundations for China’s digital preservation and utilization of ICH, while offering fresh insights for global scholars in this interdisciplinary domain. A holistic, cross-cultural framework is urgently needed to bridge fragmented research efforts, clarify cross-national divergences in technological priorities and cultural governance models, and inform more context-sensitive strategies for safeguarding intangible heritage in the digital age.

This study investigates how distinct approaches to the digitalization of ICH in China and the West can evolve into mutually enriching, integrated methodologies. By examining divergent practices and paradigms in ICH digitalization across these cultural contexts, we aim to provide a holistic framework that advances global efforts in this field. Leveraging CiteSpace software (Chen et al. 2023), we analyze literature from the CNKI and WOS databases, combining qualitative and quantitative methods to map global research trends (Chen, 2006), identify emerging trajectories, and pinpoint disciplinary frontiers (Su et al. 2019). The findings seek to catalyze cross-pollination between Eastern and Western scholarly traditions, fostering innovative strategies for preserving and revitalizing intangible heritage in an increasingly interconnected digital era.

This article addresses the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the primary digital strategies and technological approaches for ICH preservation adopted in Western contexts?

-

2.

How do Chinese and Western models of ICH digitalization differ, and where do they intersect?

-

3.

In what ways can the integration of Chinese and Western practices enhance the overall effectiveness and global impact of ICH digitalization?

By examining the differences between Chinese and Western research approaches, application domains, and technological strategies, this study aims to propose a more holistic and globally applicable framework to enhance the effectiveness and global reach of the field, enabling the digitalization of ICH digitalization, and enabling it to better support the transmission of traditional culture and the innovative development of cultural heritage across diverse regions.

Despite increasing attention to the field, existing studies often remain fragmented across disciplines, lacking holistic, transnational perspectives. Future research should strengthen cooperation across disciplines to promote the organic integration of digital technologies with traditional culture. Future studies on ICH digitalization must prioritize “humanistic factors,” transform design philosophies, leverage localized empirical cases, establish interdisciplinary research systems, and develop theoretical frameworks and practical pathways with broad applicability. Through such cross-cultural integration and innovation, effective preservation and transmission of intangible cultural heritage can be achieved in the context of globalization, providing practical solutions for nations in cultural heritage conservation and dissemination while fostering culturally inclusive models to safeguard humanity’s shared heritage.

While this study utilizes quantitative metrics (e.g., the number of digitalization projects and related publications) to identify trends in ICH digitalization (Dippon and Moskaliuk, 2020), these metrics may fail to fully capture the depth and cultural impact of ICH digitalization practices. Quantitative measures risk overlooking nuanced qualitative aspects of ICH digitalization in inheritance, innovation, and cultural reconfiguration (Hu, 2023), such as its role in cultural transmission, innovation, and transformation—elements that challenge traditional perceptions, foster social engagement, and drive cultural evolution. Sole reliance on quantitative data may oversimplify the complexity of ICH digitalization practices, such as the intricate processes of cultural content transmission, active community participation, and long-term cultural significance that transcend quantifiable digital outputs. To address these limitations, this research integrates qualitative assessments with quantitative indicators, focusing on the cultural value of digital outcomes, community acceptance, and their broader implications for cultural preservation and innovation. This balanced approach emphasizes the uniqueness of ICH digitalization practices and highlights their profound yet often unquantifiable contributions to cultural heritage preservation in a globalized context. By merging quantitative and qualitative perspectives, this study aims to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the transformative potential and cultural significance of ICH digitalization.

Research design

This study employs bibliometric analysis and visualization methods based on the WOS and CNKI databases to systematically review the global evolution and developmental trajectory of digital preservation research for ICH. The analysis identifies key research hotspots and emerging trends through knowledge mapping. Through a comparative analysis across four dimensions—practical applications, theoretical frameworks, disciplinary development, and societal impacts—this research reveals significant commonalities, strategic complementarities, areas of convergence, and synergy between Eastern and Western approaches to ICH digitalization. These findings enhance the practical value and applicability of academic research while providing actionable insights for cross-cultural heritage preservation initiatives. The methodological workflow is detailed in Fig. 1.

Research methods

The study is structured as follows

Part 1 introduces the data sources and research methods. Part 2 analyzes digitization policies related to ICH and provides case studies of ICH digitization applications. It further conducts analyses based on the number of published papers, author collaborations, most-cited literature, and research institutions. Additionally, it analyzes and summarizes key categories within the research field, highly cited articles, and literature. Part 3, building on the literature review and integrating global research trends and specific content, compares ICH digitization practices between China and Western countries. It explores their differences and commonalities in four aspects: Cultural values and preservation concepts, Technology application and implementation, Policy and legal frameworks, and Cultural inheritance and public participation. Finally, the paper discusses future research hotspots, evolutionary trends, and development prospects. Through the above analysis of the differences in ICH digitization between China and other developed Western countries, it explores how to achieve cross-cultural dissemination of ICH digitization, promote its integration and complementarity, and proposes future research directions and outlooks for related fields.

Data sources and methodology

This study utilizes WOS and CNKI as core databases. WOS, integrating SCI, SSCI, and AHCI, covers over 20,000 authoritative global journals across disciplines, while CNKI specializes in comprehensive Chinese-language academic resources. Their complementary disciplinary coverage and cultural perspectives establish a robust data foundation for analyzing the digitization of ICH in sustainable development and Sino-Western cultural exchange contexts.

The research theme explores the digitization of ICH within the context of achieving sustainable development and promoting cultural exchange between China and the West. In the years following the 2003 UNESCO Convention, numerous countries and organizations have issued relevant policies or measures, some of which are summarized in Table 1. Consequently, the data collection period spans from January 2006 to December 2024, and this study selects research outcomes from the nearly 19-year period (2006–2024) for visualized analysis.

Next, keyword selection is essential. This study uses “intangible cultural heritage” and “digitalization” as the primary keywords. Accordingly, in the WOS database, the term “digitalization” is represented by the keywords: “VR” OR “Digital Technology” OR “Digital Tech” OR “Information Technology” OR “Digital Sciences” OR “AI” OR “Digitalization” OR “Digitization” OR “Digital” OR “AR”. Meanwhile, “intangible cultural heritage” is represented by “Intangible Cultural Heritage” OR “Living Heritage” OR “Heritage Alive”. Therefore, the search query used in the WOS Core Collection is: (“VR” OR “Digital Technology” OR “Digital Tech” OR “Information Technology” OR “Digital Sciences” OR “AI” OR “Digitalization” OR “Digitization” OR “Digital” OR “AR”) AND (“Intangible Cultural Heritage” OR “Living Heritage” OR “Heritage Alive”).

For the CNKI database, the search formula “(Digitalization + Information Technology) * Intangible Cultural Heritage” is applied. The search is conducted under the “Topic” category, covering core collections such as titles, keywords, authors, and institutions.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria (Zhu et al. 2024): To ensure methodological transparency, the following criteria were applied:

-

Inclusion: Only peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings directly addressing ICH digitalization were retained.

-

Exclusion: Non-academic sources (e.g., book chapters, news articles, reviews, policy briefs), duplicate entries, and publications irrelevant to digital heritage were excluded.

-

Deduplication: Duplicates across CNKI and WOS were identified and removed using manual screening and CiteSpace’s built-in preprocessing functions.

-

Journal Scope (CNKI): Articles were limited to those published in core journals indexed by Peking University Core Journals, CSSCI, CSCD, AMI, WJCI, and EI.

Additionally, we conducted a literature review by collecting, identifying, and organizing publications related to the digitization of intangible cultural heritage from libraries, CNKI, WOS, and other online platforms. Through comprehensive reading and synthesis of existing research, we gained a thorough understanding of current research directions in this field.

Finally, we employed a comparative analysis method to examine the digitization of intangible cultural heritage in Chinese and Western contexts, highlighting the characteristics and achievements of such efforts under different cultural and social backgrounds.

CiteSpace configuration: CiteSpace 6.3.R1, a Java-based scientometric software, was employed to analyze academic trends in ICH digitalization. It enables visualization of the structure, co-occurrence networks, and thematic evolution of research literature across time.

Key parameters used in this study include:

-

Time slicing: 2006–2024 (1-year per slice).

-

Node types: Author, Institution, Country, Keyword, Reference.

-

Selection criteria: Top N = 50 per slice.

A total of 798 initial records were retrieved from two databases: the WoS Core Collection and the CNKI, covering the period from 2006 to 2024 (see Table 2 for full search terms).

After applying strict inclusion criteria, 467 valid articles were retained from the WoS database.

In the CNKI database, 341 records were initially retrieved from the core academic journals. After manual screening and duplicate removal, 331 valid CNKI articles were retained.

Through visualization and scientometric analysis of publications, keywords, research institutions, authors, and countries from the combined 798 articles, we identified research hotspots, developmental trajectories, and epistemological divergences in the digital preservation of ICH across Chinese and Western contexts.

In this study, a knowledge map was constructed using CiteSpace to analyze data across various domains of Intangible Cultural Heritage Digitization (ICHD) from 2006 to 2024. The temporal analysis reveals distinct evolutionary phases, with foundational studies (2006–2012) emphasizing core themes like “digital preservation” and “technology implementation.” Using annual time slicing with default parameters, we systematically examined keyword co-occurrence patterns, author collaborations, institutional networks, and international publication trends.

The analysis identifies three critical development stages in ICHD research, demonstrating significant paradigm shifts from technological experimentation to integrated conservation frameworks. Through a comparative examination of Chinese and Western digitization practices, this study proposes an adaptive framework for localizing international experiences. The findings establish theoretical foundations for context-sensitive digitization strategies while providing practical recommendations for sustainable implementation, specifically addressing China’s unique requirements in cultural resource management and technological adaptation.

Analysis of research hotspots in digitization of intangible cultural heritage

Results

Publication volume and trends

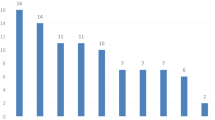

The number of publications serves as a critical indicator for measuring the development of a field (Ludo Waltman, 2016), directly reflecting the level of attention researchers in a country devote to that domain (Aksnes et al. 2019). Figure 2 displays the publication counts from the WOS and CNKI databases between 2006 and 2024. The WOS database contains 476 valid articles, while the CNKI database includes 332 valid entries. Overall, the publication volume shows a gradual upward trend (Table 3).

Changes in publication numbers represent a fundamental metric for tracking the evolution of a research field (M.J. Cobo et al. 2011). From 2006 to 2024, the publication volume in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Digitalization (ICHD) field within the WOS database underwent three distinct phases: Slow Initial Growth (2006–2012), Steady Expansion (2013–2019), and Rapid Development (2020–2024).

In contrast, the trend in the CNKI database from 2006 to 2024 differs slightly. During the early phase, CNKI exhibited faster growth compared to WOS. The second phase saw fluctuating development, while the third phase diverged from WOS trends: WOS experienced accelerated growth, whereas CNKI maintained stable growth in publication volume.

Slow start-up phase (2006–2012)

During the period from 2006 to 2012, research on the digitization of ICH began to emerge (Jansong Bai, 2011). Concurrently, numerous national institutions introduced initiatives to promote the development of ICHD, though research intensity remained relatively low during this phase. In 2005, the General Office of the State Council of China issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage(Xu et al. 2022). In 2006, the Interim Measures for the Protection and Management of National-Level Intangible Cultural Heritage were promulgated (Li et al. 2025), further emphasizing the need to “encourage local governments to disseminate ICH knowledge through mass media and other means, fostering public engagement and shared cultural resources.” Notably, the publication volume on the CNKI database during this period consistently surpassed that of the WOS database.

Steady growth phase (2013–2019)

In 2011, the European Commission launched the Creative Europe program, which aimed to provide €1.46 billion in funding to support Europe’s cultural and creative industries from 2014 to 2020 (Kandyla, 2015; Borrione et al. 2024). This initiative significantly boosted global attention toward ICHD research, including in developing countries, leading to a gradual increase in related academic publications. Additionally, in 2017, China’s General Office of the State Council issued the Notice on Revitalizing Traditional Chinese Crafts, which emphasized “exploring the integration of traditional craftsmanship with modern technology and equipment, improving material processing capabilities, and strengthening the translation of research into practical applications” (Alivizatou-Barakou et al. 2017a; Jing Gao and Bihu Wu, 2017). It also called to “encourage commercial and specialized websites to establish online sales platforms for promoting traditional craft products.” These policies collectively drove rapid growth in ICHD research during this phase.

Rapid development phase (2020–2024)

From 2020 onward, ICHD research entered a phase of accelerated growth, marked by intensified international collaboration and post-pandemic recovery. In 2019, 26 European nations signed a Cooperation Declaration on Advancing Cultural Heritage Digitization(Piaia et al. 2022), urging member states to strengthen partnerships in digital technology and heritage preservation (Lian and Xie, 2024). Building on this, the European Commission introduced the 10 Basic Principles for 3D Digitization of Tangible Cultural Heritage in 2020, providing standardized guidelines for practitioners and institutions engaged in heritage digitization projects. These initiatives spurred a notable increase in ICHD research, with a significant surge observed in 2022 as global sectors recovered from pandemic disruptions and resumed normal operations.

The pandemic’s gradual decline after 2022 further facilitated academic and technological exchanges, enabling renewed focus on digitization efforts (Zancajo et al. 2022; Eric Viardot et al. 2023). Concurrently, advancements in artificial intelligence, 3D modeling, and cloud computing expanded the scope and precision of ICHD applications. By 2023, interdisciplinary collaborations between cultural institutions, tech companies, and academia became commonplace, fostering innovation in virtual reconstructions, digital archiving, and interactive heritage experiences.

Overall, the convergence of sustained technological progress, global cultural exchange, and policy-driven frameworks has positioned ICHD as a critical area of academic and practical interest. The field is rapidly evolving toward establishing a mature research ecosystem, offering actionable insights for global heritage preservation. However, academic output often lags real-world advancements due to publication cycles and implementation delays. As such, this paper predicts a substantial rise in ICHD-related scholarly publications in the coming years, driven by deepening interdisciplinary engagement and the urgent need to safeguard intangible heritage in an increasingly digital world. These developments are expected to further refine methodologies, enhance cross-border partnerships, and solidify ICHD’s role in global cultural sustainability strategies.

Authors’ cooperation distribution analysis

Through systematic analysis of the distribution of author collaboration networks, interdisciplinary collaboration relationships within the ICHD field, and collaborative research directions, this study aims to identify the emergence of core author groups (Liu et al. 2022; Maltseva and Batagelj, 2022). The research seeks to provide new pathways for collaboration between the ICHD domain and other disciplines. Academic contributions from different research teams are quantified based on their published literature and institutional affiliations, with data imported into CiteSpace for further analysis.

The author collaboration network (Fig. 3) comprises 330 nodes—each representing an individual author or institution—and 320 edges that denote co-authorship relationships. The network exhibits a low density of 0.0059, indicating a relatively sparse but emerging collaborative structure within the field of ICH digitalization research. In this visualization, node size corresponds to the number of publications attributed to each author, with larger nodes indicating higher academic output or centrality. The colors of the nodes reflect the temporal distribution of publications, where cooler colors (e.g., purple) represent earlier years and warmer colors (e.g., yellow) denote more recent activity. Edges between nodes signify collaboration; thicker and shorter lines indicate closer co-authorship ties.

The figure presents the co-authorship network extracted from the Web of Science database. Each node represents an author, with node size indicating the number of publications. Links between nodes reflect co-authorship relationships, and thicker lines signify stronger collaboration frequency. Clusters are color-coded to indicate different research groups or academic communities.

Several central clusters can be observed, representing core academic groups with higher internal collaboration. Notably, authors such as Crawford, Guo Jing, Lee Der-Horng, and Giaccardi appear prominently within the network, serving as key connectors or knowledge hubs within the global research landscape.

Table 4 further details the profiles of top-contributing authors, including their total publications, institutional affiliations, and co-authorship frequency, highlighting their influence and collaborative capacity in the field. This network graph, generated using CiteSpace 6.3.R1 based on WoS data (2006–2024), provides a visual representation of the evolving scholarly landscape in ICH digitization and reveals potential opportunities for enhanced international and interdisciplinary cooperation.

By integrating Price’s Law with CiteSpace analytical methods, this study focuses on collaboration patterns within the research field and cross-citation relationships among researchers. Price’s Law, a critical metric in scientometric analysis, quantifies the distribution of scholarly productivity (Kastrin and Hristovski, 2021). Its formula is expressed as

In this context, \({M}_{{\rm{P}}}\) represents the minimum number of publications required for an author to qualify as a “core author,” while \({N}_{{\rm{P}}max}\) denotes the publication count of the most prolific author during the study period. This method scientifically identifies active contributors in the field (S. Alonso et al. 2009). As shown in Table 3, the highest number of publications by a single author in the WOS database is five, thus \({N}_{{\rm{P}}max}=5\). Substituting this value into Formula (1):

This result indicates that scholars who have published two or more papers (rounded from 1.675) can be classified as core authors in this research domain.

Similarly, as shown in Table 5, we analyzed 331 papers published between 2006 and 2024 in the CNKI database. Each node represents an author, with node size indicating publication output and node color reflecting publication year (from purple to yellow). Edges denote co-authorship relationships. The network shows moderate connectivity and a dispersed structure, suggesting limited large-scale collaboration in Chinese ICH digitalization research. The most prolific author in this dataset published five papers. Substituting this value (\({N}_{P\max }=5\)) into Formula (1), we derive:

This calculation confirms that scholars who have published two or more papers (rounded from 1.675) qualify as core authors in this field.

Overall, while some scholars in this field demonstrate relatively high publication outputs, the intensity of collaborative engagement remains limited (Fig. 4). Current collaborations predominantly occur within small teams, with minimal cross-team interactions. According to CiteSpace analysis, the field currently lacks academic teams with strong central leadership. To advance the discipline, future efforts should prioritize strengthening partnerships and knowledge exchange between academic institutions and regional scholars, thereby fostering cross-regional academic collaboration. Such in-depth cooperation is expected to cultivate leading research groups with significant scholarly influence, driving sustained innovation and progress in the field.

This figure displays the co-authorship network derived from the CNKI database. Each node represents an individual author, with larger nodes indicating higher publication output. Edges between nodes reflect collaborative relationships, and different colors indicate distinct clusters or research groups.

Highly cited articles

In the WOS Core Collection, we conducted a keyword search using “ICHD” to retrieve cited articles, which were then sorted by citation count in descending order to generate Table 6. The most cited article is “Digitization of Cultural Heritage: Challenges and Opportunities” (Skublewska-Paszkowska et al. 2022) (cited 12 times, centrality 0.01). This study examines the technical, ethical, and legal challenges of digitizing cultural heritage, with a focus on the current applications of digital technologies in preservation efforts. It highlights the potential of digitization for safeguarding, showcasing, and disseminating traditional cultural heritage. The second most cited paper, “Digitizing Intangible Cultural Heritage Embodied: State of the Art(Hou et al. 2022)” (cited 12 times, centrality 0.03), explores the digitization of ICH, particularly how digital technologies can capture and convey the living, dynamic aspects of ICH. The authors address the technical and curatorial complexities of integrating both tangible and intangible dimensions within meaningful contexts. The third-ranked article, “Heritage 3D: A Tool for Exploring and Visualizing Cultural Heritage Through 3D Models” (Kassahun et al. 2018) (cited 11 times, centrality 0.03), introduces the “Heritage 3D” tool, designed for the exploration and visualization of cultural heritage via 3D modeling. The paper elaborates on how this tool enables innovative approaches to preservation, exhibition, and research, while also discussing the challenges of applying 3D modeling in heritage studies. Detailed information on other cited works is provided in Table 6 and Fig. 5.

Figure 5 further visualizes the references with the strongest citation bursts identified in the Web of Science dataset between 2006 and 2024. In this CiteSpace-generated network map, each node represents a reference article, and the size of the node corresponds to its citation frequency—larger nodes indicate more frequently cited papers. The color spectrum (from purple to yellow) reflects the time of citation burst onset, with yellow indicating more recent influence. The links (edges) between nodes reflect co-citation relationships, indicating the presence of thematic or conceptual clusters among influential works. This visualization helps to identify emerging research frontiers and benchmark literature within the field of ICHD.

In the CNKI database, due to the limitations of CiteSpace software in analyzing data from this platform, a table was manually created to list the top 10 most cited articles. The most cited article is “Research on the Digital Protection and Development of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage” (cited 866 times). This study focuses on the critical role of digital technologies in the preservation and transmission of ICH, exploring implementation pathways and providing recommendations for advancing this field.

The second most cited article is “Digital Preservation: A New Approach to Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage” (cited 437 times). This work highlights digitization as a technological innovation in ICH preservation, emphasizing its potential to enhance efficiency while advocating for its integration with traditional methods and attention to cultural ethics. The article laid the early theoretical and practical foundations for digitizing ICH.

The third most cited study is “Preservation and Utilization of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Digital Era” (cited 347 times). It argues that digital technologies offer new pathways for ICH conservation but require balancing technological, cultural, and traditional considerations. The research underscores the significance of cultural innovation in practice and constructs an analytical framework for ICH digitization, providing valuable insights for policymaking and implementation (see Table 7 for details of other highly cited works).

Through an analysis of highly cited literature across the two databases (WOS and CNKI), distinct differences in research directions between Western and Chinese scholarship in the field of ICHD become evident.

In the WOS database, the highly cited articles focus on innovative applications of digital technologies—such as VR, AR, 3D modeling, motion capture, and ubiquitous computing—in the preservation, exhibition, and education of cultural heritage. These studies reflect the global trend toward digitization and interdisciplinary integration in cultural heritage research, encompassing multidisciplinary perspectives.

In contrast, the CNKI database features articles that emphasize theoretical foundations, technological applications, status analyses, and future development pathways for the digitization of ICH. Key themes include technical aspects (e.g., digital collection, storage, and display), dissemination methods (e.g., new media and information space theory), and explorations of policy frameworks and interdisciplinary collaboration.

WOS publications prioritize technical details and the development of tools, often targeting international audiences and emphasizing the intersection of technology and heritage. CNKI’s highly cited works, however, center on theoretical discussions, policy analyses, and practical implementations of digital data collection, storage, dissemination, and VR technologies.

This comparison underscores the necessity for cross-disciplinary collaboration in ICHD research to establish a more comprehensive system that addresses contemporary needs in heritage preservation and transmission. Citation counts not only indicate the academic influence of these works but also highlight their significance and representativeness within the field. By analyzing highly cited articles, researchers can identify current frontiers and predict future trends (Cipresso et al. 2018; Yan and Zhang, 2023). Furthermore, examining the relationship between citation frequency and publication timelines helps reveal the field’s developmental trajectory and emerging advancements.

Research hotspots and research strategies

Keyword co-occurrence network

Keyword co-occurrence analysis is a method that examines the distribution patterns of selected keywords within a database (Aryadoust and Ang, 2021; Yuan et al. 2022). Compared to co-citation analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis offers a more intuitive visualization of research hotspots, thematic distributions, and disciplinary structures within a field (Liu et al. 2015). This approach helps uncover the core content, methodologies, and central ideas of scholarly articles. By employing keyword co-occurrence analysis, researchers can identify key themes and emerging trends in a domain, thereby providing robust support for a deeper understanding of the research landscape.

The data from the WOS database was imported into the software, with the time slice set from 2006 to 2024 and a time interval of 1 year. Using keywords as network nodes, a keyword co-occurrence map for ICHD was generated, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

According to Fig. 6, the keyword co-occurrence network in the WOS database, the ICHD field contains 392 nodes and 786 links, resulting in a network density of 0.0103. In this visualization, the node size reflects the frequency of keyword occurrences—the larger the circle, the more frequently the keyword appears. The links between nodes indicate co-occurrence relationships, meaning that the connected keywords appear together in the same articles. Network density (D) represents the overall tightness of the connections within the network. It is calculated using the following formula:

where D represents the network density, E denotes the number of connections (links), and N is the number of nodes. The density value ranges between [0, 1] (Meng et al. 2020; Zhong et al. 2023). A value approaching 0 indicates a completely isolated network with no connections, while a value approaching 1 signifies a fully connected network where every node is linked to all others. In this study, the relatively low density (0.0103) suggests a diverse and expanding research field with emerging thematic clusters rather than a tightly interconnected structure.

Using the keyword frequency statistics provided by CiteSpace, the top two high-frequency keywords from each of the three phases (2006–2024) were extracted and are presented in Table 8.

Figure 7 presents the keyword co-occurrence network for ICHD-related literature retrieved from the CNKI database. The map comprises 305 nodes (keywords) and 352 links (co-occurrence relationships), with a network density of 0.0076. Compared to the WOS network (see Fig. 6), this lower density indicates weaker overall connectivity among research topics, suggesting greater fragmentation and limited thematic integration across studies within the Chinese academic context. The relatively sparse network structure reflects a more dispersed research landscape, with less frequent collaboration or convergence among keyword clusters. When examined in conjunction with the temporal distribution of keywords in Table 9, the visualization helps identify stage-specific research hotspots and highlights the evolving thematic focus within CNKI-indexed ICHD literature over time.

The vertical stripes represent years, while the size of each node indicates the frequency of keyword occurrence. Larger circles denote higher frequency. Co-occurring links suggest thematic connections between keywords. Core keywords such as “数字化 (digitization),” “保护 (preservation),” and “传承 (transmission)” indicate sustained scholarly focus in Chinese literature, with increasing attention to virtual reality, cultural tourism, and public participation in recent years (Fig. 8).

This timeline visualization highlights the annual emergence and clustering of keywords related to intangible cultural heritage digitalization (ICHD) in Chinese literature. Larger circles represent higher keyword frequency, with “数字化” (digitization), “保护” (preservation), and “文化遗产” (cultural heritage) as central themes. The color gradient indicates different years of appearance from 2006 (purple) to 2025 (yellow), while lines denote co-occurrence relationships between keywords.

The timeline-based co-occurrence map visualizes keyword evolution, where node size reflects frequency and connecting lines indicate co-occurrence. Key terms such as “cultural heritage,” “virtual reality,” and “augmented reality” dominate, reflecting the Western emphasis on immersive technology in ICH preservation. The visualization illustrates the shift from foundational themes (e.g., digital archives) to emerging topics such as digital twins and community engagement (Fig. 9).

In summary, based on literature from both databases and statistical results, researchers in the WOS database frequently used keywords such as digital preservation and digital technology during the early stages of ICHD research. During the stable growth period, ICH and cultural heritage became the most prominent keywords. In recent years (2023–2024), the research hotspots in the ICHD field have shifted to models and user experience. This indicates a transition in the ICHD field from an initial focus on digital technology to the current emphasis on applying models and methods to enhance user experience in the digital preservation and dissemination of intangible cultural heritage. Overall, Western scholars prioritize the application of digital technologies in cultural heritage presentation, particularly through innovative tools like VR and AR to improve interactive user experiences and innovative designs for cultural transmission. In contrast, literature from the CNKI database focuses on the digital preservation and transmission of cultural heritage, especially through data processing, information technology, and AI to safeguard and disseminate cultural content. Detailed comparisons are provided in Table 10. Notably, due to the CNKI retrieval date being December 31, 2024, a small number of publications labeled as “online first” in the database have actual publication dates in 2025, which explains the inclusion of 2025 data in Fig. 9. By analyzing Figs. 8 and 9, the annual research hotspots in this field can be clearly identified.

Keyword clustering analysis

Keyword clustering analysis can effectively categorize knowledge domains, enabling in-depth exploration of research hotspots (Nan Ye et al. 2020). A Q value (modularity) >0.3 indicates significant clustering, as shown in Formula (3). When the S value (weighted average silhouette) exceeds 0.5, it suggests a reasonable clustering structure (Li et al., 2024). When S > 0.7, the clustering results are not only reasonable but also efficient and highly convincing (Wang et al., 2024), as demonstrated in Formula (4).

Figure 10 presents the clustering map of the WOS database, with Q = 0.6243 and S = 0.9364, indicating strong structural differentiation with clear community boundaries. The silhouette value (S) exceeding 0.7 reflects high intra-cluster consistency and reliable clustering results, with substantial differences between intra-cluster and inter-cluster elements and well-defined node assignments.

Figure 10 contains a total of 13 major clusters, each composed of keywords representing research themes in the field. The cluster numbering (e.g., #0, #1) reflects the relative centrality of the theme, with smaller numbers indicating more central clusters (Chen, 2006). For example, Cluster #0 intangible cultural heritage is the largest and most core cluster. Cluster #1 user experience (Tong et al. 2018; Hulusic Vedad et al. 2023; Shen et al. 2024) and #3 virtual reality (Lucio Tommaso De Paolis a et al. 2022) represent technology-oriented subtopics. Clusters like #7 digital protection (Zhou et al. 2019; Skublewska-Paszkowska et al. 2022) and #8 digital preservation (Pramartha and Davis, 2016; Cozzani et al. 2017) are closely related to cultural heritage conservation.

The analysis of the CNKI database identified 9 clusters with Q = 0.776 and S = 0.965 (Fig. 11), indicating a high degree of community structure and well-delineated thematic boundaries. The strong modularity (Q) and silhouette (S) values demonstrate that the clusters are both well-formed and meaningfully separated, effective representation of distinct research groups or hotspots within the knowledge domain.

Clusters positioned earlier in the analysis (e.g., #0 digitalization, #1 protection, #2 inheritance, #3 big data, #4 digital technology, #5 inheritors (Su et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2023)) reflect core research directions and emerging focal areas. These results highlight how scholars in the CNKI database leverage digital technology to protect intangible cultural heritage, emphasizing preservation methods, cultural continuity, and the integration of heritage practices into modern urban contexts.

The colors and contours in Fig. 11 represent the temporal and topical spread of each cluster, where warmer colors (e.g., yellow, orange) indicate more recent research. The compactness of node clusters and their density reflect stronger intra-topic cohesion, particularly around digitalization-related themes.

Keyword timeline analysis

Timeline analysis of keywords focuses on tracking the evolution of specific keywords over time to identify research trends, while time zone mapping is used to visualize the distribution of keywords over time (Xin-Lei Yu et al. 2022). Specifically, timeline analysis helps uncover the emergence, duration, and transformation of core concepts within a knowledge domain, offering a diachronic perspective that highlights both continuity and novelty in scholarly discourse. Compared to static keyword co-occurrence maps, timeline analysis presents the longitudinal trajectories of key themes, thus facilitating a deeper understanding of field evolution and thematic transitions (Yuqing Geng et al. 2024).

As shown in Fig. 12, the timeline indicates that WOS scholars have gradually shifted their research toward more efficient and innovative technologies, such as virtual reality (Li, 2020; Qiu et al. 2024), artificial intelligence (Cao, 2025), and digital humanities, while also placing greater emphasis on user experience optimization. This trend reflects a paradigm shift from passive documentation to interactive and immersive engagement with ICH. Research hotspots have evolved from a single focus on preservation and protection to a more diverse range of applications, including social media (Qihang Qiu, 2023) and augmented reality (Liu, 2023; Buragohain et al. 2024). The emergence of these new keywords also points to interdisciplinary integration and the growing role of participatory digital platforms in ICH dissemination.

This figure visualizes the temporal distribution and clustering of keywords in CNKI-indexed literature on ICH digitalization from 2006 to 2024. Key thematic clusters include “Digitalization,” “Protection,” “Inheritance,” and “Big Data.” The color gradient indicates the time of emergence, with warmer colors (e.g., yellow) representing more recent years. Node size reflects frequency, and links represent co-occurrence relationships among terms.

Figure 13 presents the keyword timeline analysis of CNKI scholars in the field of ICHD. In the figure, nodes represent keywords, and their size indicates the frequency of occurrence (Vlase and Lähdesmäki, 2023). The color gradient, ranging from cool colors (blue purple) to warm colors (orange yellow), represents the progression of time. Earlier years are shown in purple, while more recent years appear in yellow. The cluster labels on the right and the node colors illustrate the temporal evolution, with darker purple indicating earlier years, closer to 2006.

For example, cluster #0 “digitalization” has been a consistent research topic from the early years to the present. However, there was a pause in research activity during 2020–2021, which may correlate with disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, cluster #11 “cultural space” was only active between 2015 and 2019, suggesting a period-specific focus that did not continue into the following years. These temporal differences reveal that CNKI scholars tend to concentrate on foundational or policy-driven topics that evolve in bursts, often shaped by national agendas or external disruptions. Overall, based on the above analysis, Chinese and Western scholars exhibit divergent thematic evolutions and temporal dynamics in the field of ICHD.

Research trends analysis

The intensity of keyword emergence can be explored by analyzing multiple thematic terms to investigate shifts in hot research topics within specific periods. Burst terms reflect abrupt changes in research focus during particular intervals (Zhang and Zou, 2022; Hu et al. 2024b). In these studies, high-frequency keyword shifts are identified as burst changes, revealing the timing of transitions in research themes and the evolving dynamics across different periods. Using CiteSpace’s burst detection method, we analyzed the evolution of 18 burst terms in the WOS database from 2006 to 2024. As shown in Table 11, there are distinct differences in research hotspots across disciplines and timeframes.

From 2006 to 2012, studies on ICHD primarily focused on digital preservation and digital museums. Starting in 2011, the volume of ICHD-related literature increased rapidly, with research still centered on ICH. By 2015, the field diversified significantly, expanding into disciplines such as architecture, interactive design, and folk dance, with dance-related topics emerging as a research hotspot.

From 2020 onward, key research themes shifted toward digital storytelling, embodied interaction, and design methodologies, while sustainable development gained prominence in recent years. Many keywords experienced a sharp rise in research intensity over short periods and maintained high visibility, suggesting influences from technological advancements, growing academic interest, or policy-driven initiatives. For example, the rapid growth of “sustainable development” and “cultural heritage” studies post-2021 likely aligns with global emphasis on sustainable cultural preservation. This trend highlights that research and practice now extend beyond technical aspects to encompass long-term cultural, social, and environmental impacts.

Table 12 presents the keyword emergence analysis for ICHD in the CNKI database. From 2006, virtual reality and information technology gradually gained prominence, reaching a significant peak during 2006–2009. While information technology began to decline around 2013, virtual reality remained active, reflecting sustained scholarly interest. During this period, research hotspots primarily revolved around ethnic minorities and information technology, marking the early developmental phase of technological applications.

Starting in 2009, themes such as preservation and traditional culture emerged, with “preservation” showing a rapid upward trend from 2009, peaking in intensity after 2013 and maintaining prominence until 2015. This likely mirrors growing societal attention to cultural heritage conservation. The keyword “archives” garnered notable focus between 2010 and 2011 before declining, indicating a short-lived concentration on archival studies. Similarly, “ethnic minorities” and “Manchu culture” attracted brief attention around 2010 but diminished after 2012.

The evolving research trends are categorized into five distinct phases (summarized in Table 13). Overall, the focus shifted from traditional cultural preservation to digital technology applications, driven by rapid technological advancements. Emerging fields like artificial intelligence and digital culture signal future innovations in safeguarding and transmitting intangible cultural heritage, highlighting technology’s transformative role in both methodology and practice.

A comparative analysis of ICHD between China and the West

Based on bibliometric analysis and multidimensional knowledge mapping in the field of ICHD, combined with visualized data on national academic contribution distribution, author collaboration networks, and institutional synergy matrices, this study reveals multidimensional structural disparities between Chinese and Western ICHD research. Specifically, these differences can be deconstructed into four core dimensions: cultural cognition, technology application spectrum, legal and policy frameworks, and cultural transmission and public participation. Empirical data indicate that clustering analysis of scholar contribution mapping shows Western highly cited studies predominantly focus on technology-driven deconstruction of cultural heritage, while Chinese academic outputs systematically analyze the empowerment mechanisms of digital technologies in reconstructing cultural ontology. By establishing a cross-cultural comparative research framework, these findings not only provide a theoretical lens for interpreting the diverse global development models of ICHD but also offer evidence-based decision support systems for digital preservation practices through differentiated technology adaptation strategies and institutional optimization solutions.

The common grounds in digital research of ICH between Chinese and Western approaches

Both in China and the West, the application of digital technologies has remained a central focus in the study of ICH. Specifically, current research in both regions has demonstrated significant commonalities across the following four dimensions:

-

1.

Enhancing the efficiency and quality of ICH safeguarding:

Researchers universally emphasize leveraging digital technologies—such as big data, AI, and VR—to improve the efficiency and quality of ICH preservation, particularly in data storage, reconstruction, and presentation. These technologies enable digital preservation, accurate representation, and extensive dissemination of ICH, thereby facilitating its long-term safeguarding and intergenerational transmission. Digitization not only aids in preserving physical forms but also reveals its cultural essence in multiple dimensions (Smith, 1999; Hutson, 2024).

-

2.

Facilitating ICH transmission and global sharing: In the context of globalization, how digital technologies break geographical and temporal constraints to expand the reach of ICH dissemination has become a shared academic concern (Alivizatou-Barakou et al. 2017). Digitization provides cultural heritage with a platform to transcend linguistic and cultural barriers, enabling it to engage broader audiences and fostering global cultural exchange and mutual understanding.

-

3.

Interdisciplinary integration and innovation: With the rise of Digital Humanities, scholars increasingly prioritize the deep integration of humanities disciplines with technical fields such as computer science and data analytics (Zhang et al. 2024; Segessenmann et al. 2025), driving innovation in cultural heritage preservation methodologies. Interdisciplinary research perspectives have enabled more comprehensive exploration and optimization of digital technologies in ICH protection, education, and exhibition practices.

-

4.

Sustainability and innovativeness: This study posits that sustainable ICH conservation requires dialectical synthesis between addressing current societal demands and adopting cutting-edge preservation technologies, thereby establishing dynamic safeguarding ecosystems (Stefano, 2021). Digital technologies offer novel pathways for sustainable preservation while aligning ICH with modern esthetic preferences and functional demands, promoting its revitalization and reinterpretation in today’s world. For instance, Western scholars focus more on immersive cultural experiences through AR or VR, whereas Chinese researchers emphasize intelligent preservation and transmission via big data and AI-driven analysis.

While differences exist in specific technological applications and theoretical frameworks, Chinese and Western approaches to ICH digitization share fundamental goals in safeguarding, transmission, dissemination, and user experience enhancement. Both emphasize leveraging modern technological tools to ensure the long-term preservation and effective transmission of cultural heritage, while fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative methodologies. These shared characteristics reflect a unified global vision for advancing ICH safeguarding and innovation through digital technologies, transcending regional boundaries to address universal challenges in cultural sustainability.

Comparison of digital preservation of ICH between China and the West

Western nations pioneered digital ICH preservation through early adoption of VR/AR/AI technologies, exemplified by the U.S. “American Memory” project (2000) that digitized 5 million archives to preserve cultural narratives through publicly accessible databases. Similarly, the Library of Congress’s “National Digital Library Program” launched extensive initiatives to make historical sound recordings and folk narratives accessible worldwide. China’s systematic digital safeguarding commenced post-2005 following the State Council’s policy mandate, establishing foundational frameworks despite later initiation compared to Western technological leadership. For instance, the “China National Digital ICH Archive,” launched in 2011 by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of China, marked a nationwide effort to catalog and visualize state-level intangible heritage items, particularly through centralized cultural bureaus.

-

1.

Cultural values and preservation philosophies

China: In digitalizing ICH, China emphasizes dual goals of cultural inheritance and preservation, prioritizing the cultural and social significance of ICH. Efforts focus on safeguarding folk traditions, traditional crafts, festivals, and rituals, with digitization serving primarily as a tool for cultural “archiving”.

For example, the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute has digitally recorded over 1000 embroidery patterns and needlework processes, using high-resolution imaging to preserve complex textile knowledge for future generations. Similarly, the National Library of China has digitized thousands of hours of audio-visual records of traditional festivals and dialect songs, archiving endangered cultural expressions for academic research and museum displays.

The West: Western approaches prioritize cultural diversity and accessibility, emphasizing public education and global sharing. Digitization often aims to create open-access resources through online platforms, enabling worldwide audiences to engage with heritage.

For instance, Europeana provides access to over 50 million digitized items—including folk songs, manuscripts, and photographs—across multiple EU countries. Many projects emphasize multilingual access and participatory interpretation to foster global engagement. Projects like the British Library Sounds Archive and the Smithsonian Folklife Archive also showcase how Western initiatives democratize access to ICH materials via digital means.

The fundamental divergence lies in orientation: China prioritizes cultural continuity and state-led safeguarding as a mission of national heritage, whereas Western practices prioritize openness, pluralism, and democratized access to intangible cultural heritage through participatory digital ecosystems.

-

2.

Technological applications and implementation

China: In recent years, China has increasingly adopted advanced technologies like VR, AR, 3D scanning, and modeling to preserve traditional crafts and performing arts (Meng Li et al. 2022). Emerging tools like AI and big data are also being explored to analyze and catalog ICH resources systematically.

For instance, the “Digital Dunhuang” project has employed photogrammetry and AI-based pattern recognition to restore and simulate the ancient murals of the Mogao Caves. In another case, the VR rendition of Beijing opera scenes allows immersive access to stylized movements and musical traditions, thus ensuring broader intergenerational appeal.

The West: Western countries maintain leadership in innovative applications, particularly in digital museums (Pioli, 2024), archives, and document preservation. European projects, for instance, leverage data mining and intelligent search technologies to enhance academic research.

For example, the EU-funded “Time Machine Project” uses AI to reconstruct historical urban environments in 4D models, integrating architectural, cultural, and linguistic elements. In the US, the “Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages” at Stanford uses natural language processing to preserve oral traditions across indigenous communities. These implementations also prioritize interoperability, enabling integration into open heritage ecosystems.

China’s technological applications focus on immersive visual reconstruction and cultural fidelity, led by state institutions, while Western approaches emphasize interactivity, openness, and user-centered design enabled by decentralized, collaborative innovation.

-

3.

Policy and legal frameworks

China: China’s ICH digitization policies operate within a state-driven framework focused on centralized cultural heritage management (Ye et al. 2025). The Intangible Cultural Heritage Law (2011) and subsequent regulations have spurred digitization efforts, though challenges remain in establishing standardized systems and robust legal safeguards for digital outputs.

For instance, while digital archives are mandated in policy documents like the “13th Five-Year Plan for Cultural Development”, there is limited public access to digital databases beyond government portals such as the Ministry of Culture’s official site.

The West: Western nations established legal frameworks for ICH digitization earlier, guided by international agreements like UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003). Regional policies, such as those in the EU, enforce strict copyright and intellectual property protections while promoting cross-border digital collaboration.

For example, Europeana operates under the Creative Commons licensing system, ensuring legal clarity while encouraging reuse in educational and creative industries. In the U.S., the “Digital Millennium Copyright Act” supports fair use for preservation while limiting misuse through digital rights management.

China adopts a centralized, policy-driven approach to ICH digitalization with evolving legal safeguards, while Western frameworks emphasize legal pluralism, cross-border cooperation (Rukasha and Ndwandwe, 2024), and robust protections for intellectual property and digital ethics.

-

4.

Cultural transmission and public engagement

China: In China, the digitization of ICH extends beyond academic circles to emphasize public engagement at the societal level, particularly in local ICH projects (He and Wen, 2024; Xu et al. 2024). These initiatives prioritize the involvement of local communities and inheritors (e.g., artisans, performers), recognizing their role as both transmitters and co-creators of cultural meaning. One notable example is the Digital Museum of Chinese Traditional Villages, a national platform that integrates drone photography, 3D modeling, and VR walkthroughs to document and present the architecture, rituals, oral histories, and crafts of thousands of heritage-rich rural communities. Supported by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the project empowers rural communities to preserve their living traditions while inviting the public to explore and learn through immersive digital experiences. Additionally, digital technologies—especially short-form video platforms such as Douyin (TikTok)—have further enabled community members and younger generations to participate in disseminating and reinterpreting cultural heritage. Viral campaigns showcasing traditional embroidery, paper-cutting, or folk rituals not only boost visibility but also foster renewed interest and pride in intangible traditions.

The West: Western approaches focus on leveraging open platforms and digital resource sharing to enhance public participation. ICH digitization projects often integrate educational programs and interactive tools to foster global engagement. Examples include “Google Arts & Culture” immersive exhibits of endangered languages and rituals, or the “Crowdsourced Transcription Project” at the U.S. National Archives, which invites users to digitize, tag, and narrate archival heritage content. Platforms like Europeana and UNESCO’s digital portals emphasize collaborative preservation, inviting global audiences to contribute content or share interpretations.

China emphasizes broad dissemination and narrative presentation through media and institutional support, while Western models prioritize participatory engagement, community authorship, and inclusive co-curation of intangible heritage.

Beyond surface-level differences in tools and techniques, the divergent priorities of Chinese and Western ICH digitalization efforts reflect distinct sociopolitical contexts and epistemological frameworks. China’s emphasis on national identity, cultural continuity, and tourism integration is rooted in a state-driven policy environment and a cultural heritage governance model that seeks to centralize and safeguard national narratives. In contrast, Western approaches tend to prioritize technological innovation, open access, and immersive user design—features aligned with liberal academic traditions, market-driven digital ecosystems, and participatory design philosophies. These fundamental distinctions underscore the importance of contextualizing digital heritage practices within their broader ideological and institutional settings.

Discussion

This study reveals the key principles and practical pathways for the digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage through multidimensional analysis, with three main contributions. Firstly, it compares global research trends and paradigms by conducting a quantitative analysis of literature from the CNKI and WOS databases (2006–2024) using CiteSpace, highlighting academic dynamics and thematic evolution in digital ICH research. Secondly, it systematically compares the differences between Western and Chinese practices in technological applications and social impacts of digital ICH preservation. Thirdly, it proposes an integrated innovation framework combining Chinese and Western approaches, showing the potential for merging technical standardization with local cultural adaptation.

The research confirms the rapid growth of global digital ICH studies and reveals structural differences in collaborative networks: Western scholarship exhibits a “multi-nodal decentralized pattern” compared to China’s “hub-and-spoke centralized model”. Technological divergences are identified, with Western efforts emphasizing immersive dissemination technologies versus China’s focus on intelligent analytics. A “technology–culture double helix” model illustrates the contrast between the West’s “technology-driven” approach and China’s “culturally embedded” preservation paradigm. This reflects what Alivizatou (2019) identifies as divergent ontologies of digital heritage: one centered on openness and participatory access, the other grounded in symbolic continuity and national identity. The study suggests that Western platform-based dissemination risks flattening cultural content, while China faces communication barriers in regional protection practices.

Three integration pathways are proposed:

-

1.

Combining Western motion capture technology with China’s contextualized narrative approaches.

-

2.

Integrating global digital archive standards with local metadata specifications.

-

3.

Merging virtual community operations with physical inheritor networks. For instance, China could adopt Western immersive technologies to enhance communication effectiveness, while both sides could exchange experiences in community revitalization and localized heritage transmission. The study also recommends establishing global standards for digital ICH resources and balancing cultural ethics to address emerging challenges.

Based on comparative analysis of Eastern and Western approaches to digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage, this study proposes that future paradigms require Sino-Western collaboration to advance a “technology–culture–community” (Alsaleh, 2024) trilateral synergy framework. Specifically:

-

1.

Technological integration should establish coupling mechanisms between dynamic capture technologies and contextual narratives, such as embedding semantic annotation systems for traditional craftsmanship within motion capture frameworks.

-

2.

Standard interoperability necessitates building mapping systems between global digital archiving standards and local metadata to achieve a structured representation of cultural specificity.

-

3.

Ecological convergence requires designing integrated virtual-physical transmission networks that channel user participation data from virtual communities back into physical inheritor training systems. This tripartite approach reconciles technological innovation with cultural authenticity and bridges global standardization with localized implementation.

To further strengthen theoretical framing, this study connects observed empirical patterns to broader theories in digital heritage, cultural semiotics, and global cultural governance (Alsaleh, 2024). The emergence of AI, VR, and the metaverse as heritage technologies represents not only technical advancement but also symbolic shifts in how cultures are encoded, accessed, and transmitted (Smith and Waterton, 2009; Giaccardi, 2012). These tools mediate the tension between preservation and transformation, raising questions about authenticity, participation, and power in digital heritage ecosystems. As highlighted in recent cultural policy research (Xu et al. 2023), the negotiation of global standards and local meaning-making requires multi-scalar thinking across disciplinary and geopolitical boundaries.

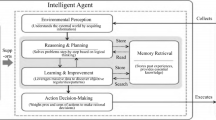

To illustrate the interactive and mutually reinforcing relationships among technological tools, cultural meanings, and community actors in digital ICH practices, a conceptual framework has been developed (see Fig. 14). This “Technology–Culture–Community” synergy model highlights how appropriate digital tools, symbolic practices, and participatory engagement can be integrated to preserve authenticity, enhance expression, and transmit heritage effectively across contexts. For a detailed articulation of inter-element tensions and collaborative goals (see Table 14).

This study systematically analyzes the practical differences and inherent connections between Chinese and Western approaches to digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage, advancing methodological innovation in the field through the construction of a culturally contextualized technological adaptation framework. The research demonstrates that the integration of Eastern and Western digital practices not only enhances preservation effectiveness but also reshapes contemporary value systems for intangible cultural heritage through the technical characteristics of digital civilization, offering creative solutions for sustaining cultural diversity. Looking ahead, there is an urgent need to establish interdisciplinary collaboration frameworks that emphasize the convergence of digital humanities and cultural anthropology. This requires in-depth exploration of emerging technological domains such as AI ethics construction and metaverse ecosystem evolution, investigating their impact mechanisms on the living transmission of intangible cultural heritage and corresponding cultural governance paradigms. Ultimately, these efforts aim to develop more inclusive pathways for digital cultural heritage preservation that harmonize technological progress with the protection of cultural authenticity while addressing global-local dynamics in standardization processes.

Limitations of the study

This study systematically analyzes the practical similarities and differences, as well as theoretical characteristics, of digital ICH research in China and the West using CiteSpace tools. However, the following limitations exist:

-

1.

Data source constraints: This research mainly draws from CNKI and WOS literature, possibly omitting insights from alternative academic platforms or gray literature.

-

2.

Methodological limitations: CiteSpace-based co-occurrence analysis offers trend identification but lacks the depth to examine nuanced technical and sociocultural dynamics. Given that ICH is a living culture, purely quantitative tools are limited in revealing its ethical, political, and affective layers.

-

3.

Potential cultural bias: Divergent East–West perspectives may introduce interpretive bias. Cross-cultural collaboration and reflexive methodologies are needed to balance dominant discourse frameworks and avoid unilateral interpretations.

-

4.

Lack of empirical validation: This study lacks field-based evidence. Future research should incorporate interviews with practitioners and digital platform users to form empirical feedback loops validating preservation outcomes.

-

5.

Scope limitations: The comparative focus on China and the West omits the Global South. Including African, Southeast Asian, and Indigenous digital heritage practices would broaden global applicability and epistemological diversity.

In summary, while this study offers new perspectives for understanding the cross-cultural logic of ICH digital preservation, it necessitates expanding data sources, deepening empirical analysis, and establishing collaborative networks to translate theory into practice. Ultimately, this will foster a more inclusive and adaptable global system for the digital safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage.

Conclusion

Summary of key findings

This study provides an in-depth comparative exploration of digital practices and applications for ICH in Western and Chinese contexts, analyzing global research trends from 2006 to 2024 using CiteSpace. The findings reveal a growing interest and diversity in ICH digital research, reflected in the increasing volume of publications in the CNKI and WOS databases, as well as expanding collaborative networks among authors and institutions.

Western scholars prioritize advanced digital technologies—such as 3D modeling, VR, and AI—to document and disseminate ICH, particularly emphasizing enhanced public engagement and cross-regional communication. By contrast, Chinese scholars focus on integrating digital technologies with traditional culture, leveraging big data and intelligent analytics to advance the “smart preservation” of ICH, with particular emphasis on cultural education and community participation.

This research fills a critical gap in comparative digital heritage studies by combining dual-source bibliometric analysis and qualitative interpretation, offering a panoramic view of global scholarly dynamics. It provides novel empirical evidence distinguishing the methodological trajectories, technological emphases, and socio-cultural framing of ICH digitization in distinct academic systems.

Comparative insights and synergy potential

Comparative analysis highlights significant differences in technological application, social impact, community involvement, and cultural context between Chinese and Western approaches. Western practices emphasize global sharing of cultural heritage through digital platforms, promoting cultural diversity and knowledge dissemination, with notable progress in digital museums and virtual exhibitions. Chinese practices, however, prioritize the fusion of digital tools with traditional cultural values, aiming to protect, transmit, and innovate ICH, particularly showcasing regional distinctiveness in safeguarding ethnic and local cultures.