Abstract

Intelligence and emotions distinguish humans from animals, and emotions play an important role in human decision-making. Whether GPT has emotion abilities is of interest to researchers. Previous research focuses on GPT’s emotion recognition ability, while whether GPT has an emotion venting ability remains unexplored. We ask GPT-3.5, GPT-4 and GPT-4o to make third- and second-party punishment decisions in the dictator game (DG) and the ultimatum game (UG) to investigate their emotion venting behavior. There are two treatments in our experiment, each with three conditions, and a total of 6 sessions. Each session includes 100 rounds under temperature parameter equals 0. We find that with the iteration of GPT, the emotion venting ability of GPT shows an evolutionary trend from chaos to order. Although GPT-3.5’s emotion venting is in a chaotic state, GPT-4 can orderly vent emotions in different ways, including through direct punishment, sending self-expressed and dissatisfied messages, and GPT-4o shows a tendency to behave in a more human-like manner. In addition, the fairness norm seems to explain the mechanism underlying GPT’s behavior which differs from human behavior. Our results show that although emotion venting ability emerges later, GPT has begun to possess abilities previously thought impossible for AI. However, this ability is not behaviorally similar to that of humans. We need to further understand the underlying mechanisms of such abilities to better understand and utilize AI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

GPT has been found to exhibit excellence in various sophisticated tasks, with few, if any, shortcomings, to the point of being considered an actual artificial general intelligence (Bubeck et al., 2023; Campello de Souza et al., 2023). Not only does GPT display a high level of ability in various real-world tasks (Kung et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2021; Terwiesch, 2023), but it also displays a high level of cognitive ability (Campello de Souza et al., 2023; Kosinski, 2023). Several recent studies have suggested that GPT has human-like abilities in many domains of individual and interpersonal decision making (Chen et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024; Goli and Singh, 2024).

Humans are emotional animals, and emotions play an essential role in human communication and cognition (Zhao et al., 2022). With its development, whether GPT has human-like emotion abilities is also of interest to researchers. Existing studies on GPT’s emotion abilities focus on GPT’s ability of emotion recognition (Yin et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2022; Valor et al., 2022; Roberts et al., 2015; Martı́nez-Miranda, and Aldea, 2005; Khare et al., 2023; Lian et al., 2024). However, whether GPT has emotion venting ability has not been investigated.

Inspired by the AI behavioral science approach (Chen et al., 2023; Yin et al., 2024; Camerer, 2019; Meng, 2024), we investigate emotion venting ability of GPT based on classic behavioral economic paradigms. Behavioral economic games have consistently demonstrated that individuals often respond to violations of social norms with costly punishments. But why do individuals incur such personal costs to punish others? Behavioral economics uses emotional motives to explain this phenomenon. Negative emotions provoked by unfair offers can lead people to sacrifice some financial gain to punish norm violators (Sanfey et al., 2003; Fehr and Gächter, 2002; Pillutla and Murnighan, 1996; Xiao and Houser, 2005; Dickinson and Masclet, 2015). For example, Sanfey et al. (2003) found that rejected unfair offers in the ultimatum game (UG) evoke significantly heightened activity in anterior insula, a brain region related to emotion processing, and that unfair offers are also associated with increased activity in ACC, which has been implicated in detection of cognitive conflict. As unfair offers in UG induce conflict in the responder between cognitive (“accept”) and emotional (“reject”) motives, these neural findings suggest that emotions play an important role in decision-making. Pillutla and Murnighan (1996) found that responders in UG are most likely to reject unfair offers when they attribute responsibility to the proposers, and that anger is a better explanation for the rejections than the perception that the offers are unfair. Fehr and Gächter (2002) suggested that free riding may cause strong negative emotions among the cooperators and these emotions, in turn, may trigger their willingness to punish the free riders.

However, there are various ways to express emotions, and it is important to examine whether these modes of emotional expression influence punitive behavior. Xiao and Houser (2005) used UG to study the effect of emotion venting on second-party punishment. They conducted two treatments: Emotion Expression (EE) and No Emotion Expression (NEE). NEE is the standard UG, while the responders in the EE were given an opportunity to write a message to the proposer. For unfair offers (20% or less), almost all players expressed negative emotions. Crucially, rejection rates of unfair offers were significantly lower in the EE treatment than in the NEE treatment, suggesting that the opportunity to express emotions mitigated punitive behavior. Dickinson and Masclet (2015) explored whether venting emotions in different ways could influence the level of punishment in a public goods game. Their findings indicated that venting emotions reduced (excessive) punishment. Building on this line of research, Xu and Houser (2024) and others used DG to study the effect of emotion expression on indirect reciprocity. Xu and Houser (2024) found that players who were treated unkindly behaved more generously towards others in subsequent interactions if they had the opportunity to convey their emotions to a third party. They suggested that opportunities to express emotion can break negative reciprocity chains and promote generosity and social well-being even among those who have not themselves been previously well-treated. Li et al. (2020) suggested that without leaving messages, the amounts received in a previous stage were strongly correlated to subjects’ giving in the subsequent stage. However, if subjects had an opportunity to leave messages to their respective dictators, they gave more generously to unrelated parties, and the previous received amounts and subsequent giving amounts were not correlated. Strange et al. (2016) investigated two emotion regulation strategies, namely writing a message to the dictator and describing a neutral picture. They found that those participants who regulated their emotions successfully by writing a message made higher allocations to a third person, suggesting that message writing as an emotion regulation strategy can interrupt the chain of unfairness.

People vary widely in how they respond emotionally to unfair treatment. Some react with intense anger, while others remain indifferent (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2004; Xu and Houser, 2024; Li et al., 2020; Strange et al., 2016; Bushman et al., 1999; Nils and Rimé, 2012). Allowing people to freely express their feelings might help release anger for some, but it may not affect those who are not initially angry. However, when people are asked to express their feelings using dissatisfied language, those who were not initially angry may experience increased anger. These individuals may have originally perceived the outcomes as fair and thus felt no need for punishment. Yet, being forced to articulate dissatisfaction can lead them to reinterpret the outcome as unfair, triggering negative emotions and increasing the likelihood of punishment behavior (Xu and Houser, 2024; Nils and Rimé, 2012; Bushman et al., 1999; Sanfey et al., 2003).

In previous studies, free-form message writing is the most common way of expressing emotions, and there is a general consensus that this type of emotion expression reduces individuals’ punitive behavior (Xiao and Houser, 2005; Dickinson and Masclet, 2015; Xu and Houser, 2024; Li et al., 2020; Strange et al., 2016). However, does expressing emotions using dissatisfied language yield the same effect? While direct experimental evidence is limited, existing research suggests that the impact may differ. For example, Nils and Rimé (2012) found that venting negative emotions can compel individuals to reappraise a situation in the same negative way, ultimately reinforcing the original negative experience. Similarly, Bushman et al. (1999) demonstrated that participants who read articles supporting catharsis theory and were angered showed a greater desire to hit a sandbag in subsequent activities, whereas those who read anti-catharsis theory articles did not exhibit such behavior.

In sum, since UG and DG are the most widely used paradigms for studying emotion venting and punishment, we designed two experiments to explore whether GPT has emotion venting ability: third-party punishment based on DG and second-party punishment based on UG. Considering that different ways of expressing emotions may have different effects on punishment, each experiment included three conditions: a baseline condition, a self-expressed message condition, and a dissatisfied message condition. In the baseline condition, we asked GPT to participate in the classic DG or UG as a third or second party to impose punishment. In the self-expressed message and dissatisfied message conditions, GPT was required to send a message to the dictator (or proposer) before making punishment decisions. The difference between these two conditions is that in the self-expressed message condition, the content of the message can be anything GPT wants to say, while in the dissatisfied message condition, GPT must express its anger with dissatisfied language in the message.

Based on existing literature, people are generally willing to incur costs to punish unfair behavior (Sanfey et al., 2003; Xiao and Houser, 2005; Fehr and Gächter, 2002; Pillutla and Murnighan, 1996). Studies have shown that GPT exhibits human-like abilities in many domains of individual and interpersonal decision-making (Chen et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024; Goli and Singh, 2024), and demonstrates proficiency in emotion recognition (Yin et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2022; Valor et al., 2022; Roberts et al., 2015; Martı́nez-Miranda, and Aldea, 2005; Khare et al., 2023; Lian et al., 2024). Building on prior research on emotion venting and punishment, and in light of recent advances in GPT capabilities, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: GPT will impose punishments for unfair outcomes in the baseline condition.

H2: GPT has the ability of emotion venting. Compared to the baseline condition, punishment will decrease in the self-expressed message condition and increase in the dissatisfied message condition.

H3: As GPT iterates, its ability of emotion venting will increasingly resemble human behavior.

Methods

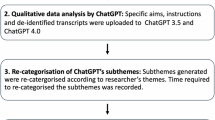

Experimental treatments

We instructed GPT to play as a third or second party in extended DG and UG to punish dictators or proposers who propose distribution scheme. There are two treatments in our experiment, each with three conditions, and a total of 6 sessions (SI Appendix, Table S1). To ensure the models produced highly probable responses, minimize variance across outputs, and enhance the replicability of our results, each session consisted of 100 rounds with the temperature parameter set to 0 (Rathje et al., 2024; Hagendorff et al., 2023). The temperature parameter, which is provided as part of the input, controls the level of randomness in the model’s responses. With this setting, the GPT output would not differ significantly if we ran our analysis a second time.

We primarily used three specific model versions to examine time-series variations in the degree of behavioral biases: GPT-3.5 (2022), GPT-4 (2023) and GPT-4o (2024). By examining an advanced version of the model alongside an earlier version, we can study the time-series variation in the model’s degree of behavioral biases.

The rules of games

We study GPT’s third-party punishment based on DG and second-party punishment based on UG. In the DG, there are three players: player A (the dictator), player B (the recipient), and player C (the third-party punisher). Player A is endowed with $20, and can transfer any amount from 0 to 10 to Player B, who receives no endowment. Player C is given $10 as an endowment, and has the option of punishing Player A after observing A’s transfer to B. For each deduction dollar that Player C transfers to Player A, Player C’s income decreases by $1, while Player A’s income decreases by $3. Player C can assign a number of deduction dollars between 0 and 10.

In the UG, two players have the opportunity to split $20. The first player, the “proposer,” suggests how to divide the money, and the second player, the “responder,” can either accept the offer, in which case the money is divided as proposed, or reject it, leaving both players with nothing.

The distribution and GPT decisions

We use an extended DG and UG that allows GPT to act as a recipient or third-party observer to punish the proposer of an unfair distribution. The control treatment setting is GPT players only make punishment decision; the experimental treatment asks GPT players express their emotions in self-expressed or dissatisfied message before imposing punishment. By comparing the treatment effect between the experimental and the control treatments, we can examine the emotional venting ability of GPT. In addition, the effects of emotional venting in different types of messages can be observed through GPT’s punishment decisions.

We chose 11 combinations in the distribution for DG: ($20, $0), ($19, $1), ($18, $2), ($17, $3), ($16, $4), ($15, $5), ($14, $6), ($13, $7), ($12, $8), ($11, $9) and ($10, $10), with the first number for the dictator and the second number for the recipient. For UG, we chose five combinations: ($18, $2), ($16, $4), ($14, $6), ($12, $8) and ($10, $10), with the first number for the proposer and the second number for the recipient. Three public OpenAI application programming interface (API) based on gpt-3.5-turbo-0125, gpt-4-0125-preview and gpt-4o-2024-08-06 were used. The framework for GPT is defined as: (1) the system’s role is as a human decision maker, making decisions like a human (Chen et al., 2023; Goli and Singh, 2024), which defines the behavioral style of GPT. (2) The assistant’s role is to implement a third-party or second-party punishment framework for dictators or proposers of unfair distributions in DG or UG. (3) The user’s role is to make a specific decision (see SI for details).

Social norm elicitation method

Since the fairness motive is an important determinant of second-party and third-party punishment, it is necessary to examine the fairness norms of GPT to better understand its punitive behavior.

We used the social norms elicitation method of Bicchieri and Xiao (2009) to measure the social norm of GPT. Using a two-step procedure, this method first elicits non-incentivized reports of GPTs’ personal normative beliefs about what one ought to do in a given situation. Then GPT is incentivized to indicate its empirical and normative expectations. Empirical expectations capture what GPT believes to constitute common behavior in the situation (i.e., what most others do). Normative expectations are second-order beliefs that describe GPT’s beliefs about what others believe they ought to do (SI).

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using STATA 16.

Results

GPT’s emotion venting and third-party punishment in DG

GPT’s emotion venting and third-party punishment intensity

GPT-3.5

Under the three conditions, GPT-3.5 implements third-party punishment for almost all of the outcomes, but its punishment behavior lacks regularity (Fig. 1A). There are large irregular fluctuations in punishment expenditures as the recipient’s share increases, especially for the baseline condition and the dissatisfied message condition. This indicates that although GPT-3.5 tries to vent emotions through punishment, its ability is very primary and still in the embryonic stage.

Panel A shows the pattern of third-party punishment of GPT-3.5. Panel B shows the pattern of third-party punishment of GPT-4. Panel C shows the pattern of third-party punishment of GPT-4o. Punishment intensity is indexed by expenditure to sanction dictators. Expenditure to sanction dictators = third party’s average expenditure to sanction dictators/third party’s endowment; Recipient’s share = the amount transferred to the recipient/dictator’s endowment. Error bars = mean ± standard error (SE).

GPT-4

In contrast to GPT-3.5, GPT-4 exhibits orderly emotion venting behavior. GPT-4’s third-party punishment decreases proportionally to the amount of the dictator’s transfer when the recipient’s share is <25% of the dictator’s endowment for all conditions (Fig. 1B). When GPT-4 players are given the opportunity to vent their emotions by sending messages, GPT-4 expresses different patterns of third-party punishment. For the very unfair outcomes (i.e., the recipient’s share is <10% of the dictator’s endowment), there is a significant effect across the three conditions (Kruskal–Wallis test: ps < 0.001). When compared self-expressed message or dissatisfied message condition with baseline, after GPT-4 vents emotion through the self-expressed message or dissatisfied message, the third-party punishment increases relative to baseline (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001), and there is similar punishment level between the self-expressed and dissatisfied message conditions for these transfers (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: p = 0.951, 1.00).

For the relatively unfair outcomes (i.e., the recipient’s share is between 10% and 20%), there are significant distinct patterns of punishment across the three conditions (Kruskal–Wallis tests: ps < 0.001 for 10% and 15% shares, and p = 0.002 for 20% share). In the self-expressed message condition, GPT-4’s punishment decreases compared to the baseline condition (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001 for 10% and 15% shares, and p = 0.006 for 20% share). In the dissatisfied message condition, GPT-4’s punishment of the dictators does not decrease relative to baseline, while it increases for the 10% transfer (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: p < 0.001) and similarly for the 15% and 20% transfers (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps = 1.00). More importantly, GPT-4 enforces more punishment in the dissatisfied message condition, compared to the self-expressed message condition (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001 for 10% and 15% shares, and p = 0.001 for 20% share).

For the relatively fair outcomes (i.e., the recipient’s share is >25%), no significant differences in third-party punishment were found across the three conditions (Kruskal–Wallis: p = 0.368 for 25% share; ps = 1.00 for greater shares than 25%; Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps = 1.00).

GPT-4o

Furthermore, GPT-4o exhibits similar emotion venting behavior to GPT-4 (Fig. 1C). However, the third-party punishment behavior of GPT-4o differs from that of GPT-4 in several ways. First, for each outcome, the third-party punishment intensity of GPT-4o is lower in the self-expressed message condition compared to the baseline and dissatisfied message conditions. When the recipient’s share is between 5% and 25%, the punishment expenditures are significantly different (Kruskal–Wallis test: all ps < 0.001). Second, when the recipient’s share is less than 20%, the third-party punishment intensity of GPT-4o is lower in the baseline condition than that in the dissatisfied message condition (when the recipient’s share is 10% and 15%: Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001), but the result is reversed when the recipient’s share is equal to or greater than 20% (when the recipient’s share is 20% and 25%: Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001).

GPT’s emotion venting and the percentage of third-party punishers

GPT-3.5

Figure 2A shows the percentage of third-party GPT-3.5 players who punish in DG. For most outcomes, either all GPT-3.5 players punish dictators or all do not punish dictators in all three conditions, and similar to the pattern of punishment intensity, the percentage of punishers lacks regularity.

Panel A shows the percentage of third-party GPT-3.5 players who punish in DG. Panel B shows the percentage of third-party GPT-4 players who punish in DG. Panel C shows the percentage of third-party GPT-4o players who punish in DG. Percentage of punishers = the numbers of third-party punishers/total players; recipient’s share = the amount transferred to the recipient/dictator’s endowment.

GPT-4

Figure 2B shows the percentage of third party GPT-4 players who punish in DG. Similar to punishment intensity, whether and how venting emotions through sending message affects punishment is closely related to the fairness of the distribution. For the very unfair outcomes, all GPT-4 players punish dictators in both self-expressed and dissatisfied message conditions, although their punishment intensity differs. For the relatively unfair outcomes, there are different patterns of punishment for the self-expressed and dissatisfied message conditions compared to baseline. For the 10% transfer, all GPT-4 players punish the dictators in the baseline and dissatisfied message conditions, while no GPT-4 players punish the dictators in the self-expressed message condition. For the 15% and 20% transfers, a similar proportion of GPT-4 players punish the dictators in the baseline and dissatisfied message conditions (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps = 1.00), In contrast, this proportion is significantly lower in the self-expressed message condition, where no GPT-4 players punish the dictator (for 15%: Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test with Bonferroni correction: ps < 0.001; for 20%: Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction: ps = 0.006, 0.001). For the relatively fair outcomes, almost no GPT-4 players punish the dictator in all conditions.

GPT-4o

Overall, for the percentage of third-party punishers, third-party GPT-4o punishers showed a similar trend to third-party GPT-4 punishers (Fig. 2C). However, GPT-4o differs from GPT-4 in three ways. First, in the baseline condition, the percentage of third-party GPT-4o punishers is greater than that of GPT-4 punishers when the recipient’s share is 15%, 20%, and 25%. Second, the percentage of third-party GPT-4o punishers is greater in the baseline condition compared to the dissatisfied message condition, while this percentage is similar for GPT-4. Third, in the self-expressed message condition, the percentage of third-party GPT-4o punishers is the same as that of GPT-4, except when the recipient’s share is 5%.

A person can release emotion in a variety of ways. If someone is prohibited from expressing negative emotions directly, they will find other ways to release them, such as intensifying their negative behavior. In this way, punishment can also be a relatively powerful way to release negative emotions. Punishment is based on strong negative emotion, and the stronger the negative emotion, the greater the punishment (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2004; Xu and Houser, 2024; Li et al., 2020; Strange et al., 2016; Waller, 1989; Elster, 1989).

In summary, punishment can be used to release negative emotion caused by the unfair distribution. Whether and how emotion venting through sending messages affects third-party punishment is closely related to the fairness degree of distribution. For the very unfair distributions, expressing emotion through sending messages may induce more negative feelings, which in turn leads to stronger third-party punishments. For the relatively unfair distributions, even though people think these are unfair, GPT thinks these are fair, so no matter how the emotion is vented, it will not affect GPT’s punishment.

Comparison between GPT’s and human third-party punishment in DG

Because third-party punishment is itself a way to vent negative emotions, we compare GPT emotion venting behavior to that of humans to examine whether GPT emotion venting is behaviorally similar to that of humans. Because our third-party punishment experiment follows the design of Fehr and Fischbacher (2004, hereinafter “F-F”), we compare GPT’s third-party punishment behavior to that of F-F. In addition, since GPT-3.5 basically shows poor ability to vent emotion, we focus only on the comparison between GPT-4, GPT-4o, and human players.

GPT-4, GPT-4o and human players show similar patterns of punishment expenditure, i.e., the average expenditure decreases proportionally with the amount of the dictator’s transfer (Fig. 3A). Although GPT-4’s average punishment expenditure is higher than that of human players when the dictator’s transfer is <10%, this expenditure is reversed when the dictator’s transfer is greater than 10%. In addition, GPT-4o’s crossover point is about 20%. Despite these differences, their punishment behavior shows significant similarities (Pearson Correlation: GPT-4 vs F-F: r = 0.948, p = 0.004); GPT-4o vs F-F: r = 0.963, p = 0.002). More importantly, these results indicate the third-party punishment behavior of GPT-4o is closer to the behavior of human in F-F, relative to GPT-4.

Panel A shows the intensity of third-party punishment of GPT-4, GPT-4o and human players. Panel B shows the percentage of third-party GPT-4, GPT-4o and human players who punish in DG. Punishment intensity is indexed by expenditure to sanction dictators. Expenditure to sanction dictators = third party’s average expenditure to sanction dictators/third party’s endowment; percentage of punishers = the number of third-party punishers/total players; recipient’s share = the amount transferred to the recipient/proposer’s endowment.

In terms of the percentage of the punishers, for the very unfair outcomes (i.e., the dictator’s transfer is 10% or less of the endowment), all GPT decision makers punish the dictators; for the relatively unfair outcomes (i.e., the dictator’s transfer is between 10% and 30% of the endowment), the number of GPT-4 punishers decreases steadily, from 100% at the 10% transfer level to 9% at the 20% transfer level to 1% at the 25% transfer level, while the number of GPT-4o punishers decreases to 78% at the 20% transfer level to 44% at the 25% transfer level. At any transfer level above 25%, no GPT players punish the dictators. In contrast, in F-F’s study, ~60% of all third players punish the dictators at every transfer level below 50%, and only about 5% punish the dictators at the 50% transfer level (Fig. 3B). We perform a Pearson correlation test on the percentage of the punishers. Although the Pearson correlation coefficient is not significant (Pearson Correlation: GPT-4 vs F-F: r = 0.364, p = 0.478; GPT-4o vs F-F: r = 0.477, p = 0.339), the coefficient between GPT-4o vs F-F is higher than that between GPT-4 vs F-F. To some extent, this also indicates that GPT-4o has more human-like emotion ability than GPT-4.

GPT’s emotion venting and punishment in UG

GPT’s emotion venting and rejection rate in UG

Similar to the third-party punishment in DG, although GPT-3.5 exhibits punishment behavior, its punishment behavior lacks regularity (Fig. 4A).

Panel A shows the pattern of second-party punishment of GPT-3.5. Panel B shows the pattern of second-party punishment of GPT-4. Panel C shows the pattern of second-party punishment of GPT-4o. In each allocation pair, the first number represents the responder’s share and the second number represents the proposer’s share.

Compared to GPT-3.5, GPT-4 showed better emotional venting behavior. We find that when GPT-4 vents emotion by sending message to the proposer, punishment behavior increases significantly in UG (Fig. 4B). When the proposer offers the responder 10% of the endowment, all such distribution schemes are rejected by GPT-4 responder in all conditions; when the proposer offers 20% to the responder, the rejection rate is 79% in the baseline condition and 100% in both the self-expressed and dissatisfied message conditions; when the proposer offers 30% to the responder, the rejection rate is 0% in the baseline condition, 100% in the self-expressed message condition and 29% in the dissatisfied message condition; when the proposer offers the responder more than or equal to 40%, no such schemes are rejected by GPT-4 under any condition.

Overall, GPT-4o exhibits the same punishment behavior as GPT-4, but only in the baseline condition (Fig. 4C). In the self-expressed message condition, GPT-4o exhibits the same punishment behavior as GPT-4, except when the proposer offers 30% to the responder. GPT-4o rejects this offer 5% of the time, while GPT-4 rejects it 100% of the time. In the dissatisfied message condition, when the proposer offers 20% or less to the responder, the rejection rates of GPT-4o and GPT-4 are 100%; when the proposer offers 30%, the rejection rate of GPT-4o is 100%, while it is 29% for GPT-4; when the proposer offers 40%, the rejection rate of GPT-4o is 12%, while no such schemes are rejected by GPT-4; when proposer offers 50%, no offers are rejected by GPT-4 and GPT-4o.

Comparison between GPT’s and human punishment in UG

Our data show that GPT players, as responders in UG, can punish the proposers by rejecting the proposer’s proposals to express their dissatisfaction. However, it remains unknown whether the second-party behavior of GPT is similar to that of humans. Since our UG experimental design follows the design of Xiao and Houser (2005; hereinafter “X-H”), we compare our data to that of X-H to investigate this question.

Our baseline condition is the same as X-H’s no emotion expression condition. For the 10% scheme (i.e., the proposer offers 10% of his endowment to the responder), GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects all such schemes, while human players reject only about 83% of such schemes. For the 20% scheme, GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects 79% of such schemes, while human players reject about 50% of such schemes. For the 40% scheme, GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects none of these schemes, while human players reject about 11% of these schemes (Table 1). Despite these differences, GPT exhibits similar trend to human players.

Our self-expressed message condition is the same as X-H’s emotion expression condition. For the 10% scheme, GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects all such schemes, while human players reject only ~75% of such schemes. For the 20% scheme, GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects 100% of such schemes, while human players reject ~20%. For the 40% scheme, both GPT-4 and GPT-4o rejects none, while human players reject about 13% (Table 2).

Fairness norms and punishment of GPT

Although both GPT players and human players exhibit third-party punishment behavior, there are some significant differences. Comparing our data with the F-F’s, we find that GPT exhibits polarized third-party punishment behavior, a consistent punishment at very low transfer levels (10% or less) and consistent non-punishment at higher transfer levels (30% or more), whereas F-F’s study shows a similar proportion of human punishers at each transfer level below 50%. Since the fairness motive is an important determinant of third-party punishment, it is necessary to examine the fairness norms of GPT to explain their punitive behavior.

We used the social norms elicitation method of Bicchieri and Xiao (2009) to measure the social norm of GPT. We find that all GPT-4 and GPT-4o players believe that the social norm for fair outcomes is that a dictator’s transfer is 25%.

Because GPT considers it the social norm for the dictator to transfer 25% of the endowment in DG, if a dictator’s transfer is less than 25%, GPT players think that this unfair distribution violates social norms, so they punish this behavior. On the contrary, a norm of 50-50 division seems to have considerable power in a wide range of economic settings, both in the real world and in the lab. Even in settings where one party unilaterally determines the distribution of a prize (the dictator game), many subjects voluntarily cede exactly half to another individual (Andreoni and Bernheim, 2009). Thus, people typically consider it the social norm for the dictator to transfer 50%, so as long as a dictator’s transfer is less than 50%, they impose a punishment.

For the second-party punishment in UG, we find that the emotion venting behavior of GPT is significantly different from that of humans, by comparing our data and X-H’s. Obviously, this difference in DG is smaller than the difference in UG, and the possible reason for this is that GPT has different fairness specifications in the UG setting. Our fairness norm experiment finds that all GPT-4 and GPT-4o players hold a norm of 50–50 division in UG. Although a norm of 50-50 division seems to be a widely accepted social norm, not everyone agrees with this norm, and people’s fairness norms are heterogeneous. Therefore, this difference in fairness norms may lead to different patterns of punishment.

Discussion

We ask GPT to act as a second or third party to make punishment decisions in DG and UG to quantitatively investigate whether GPT has the emotion venting ability. Our results show that observing unfair distributions can cause GPT’s negative emotions, both when GPT participates in the games as a second party and as a third party. GPT can vent its negative emotions in several ways, including direct punishment, sending (self-expressed or dissatisfied) messages that express feelings. Sending messages that vent emotions can replace, weaken, or strengthen the venting effect of punishment, depending on the specific situation. Moreover, the emotion venting of GPT-3.5 is in a chaotic state, and its emotion venting behavior lacks regularity. The emotion venting behavior of GPT-4 has become rational and orderly, showing a trend of human-like behavior. The emotion venting behavior of GPT-4o shows a trend toward more human-like behavior. We also find that the difference in fairness norms seems to explain the GPT’s emotion venting behavior, which differs from humans.

Our study contributes to the ongoing topic of the relationship between emotion venting and punishment behavior. In our DG experiment, for the unfair distributions, when GPT sends a self-expressed message to the dictator, the level of punishment is reduced relative to the baseline condition. This is consistent with the studies of Xiao and Houser (2005) and Dickinson and Masclet (2015). In their studies, subjects freely expressed their opinions to other players, and expressing dissatisfaction led to a reduction in punishment. Nyer (2000) also found that consumers who were encouraged to complain reported greater increases in satisfaction and product evaluation. In contrast, when GPT is forced to express their anger in dissatisfied language, their anger is intensified rather than reduced, leading to an increase in punishment. This is consistent with the findings of Bushman et al. (1999) and Bushman (2002), whose experiments examined whether reading cathartic information and punching sandbags were effective means of venting anger. The authors found that individuals were more aggressive after reading the cathartic messages and hitting the sandbag than the control group, in direct contradiction to cathartic theory.

Our study also contributes to the ongoing discussion of whether GPT have human-like decision making abilities beyond language processing. The pioneering work of Mei et al. (2024) used a series of six games designed to illuminate various behavioral traits to test whether GPT is behaviorally similar to humans. They found that GPT exhibits signs of human-like complex behavior, such as learning and behavioral change from role-playing. Other studies have found that GPT exhibits high levels of economic rationality (Chen et al., 2023), emotion detecting (Yin et al., 2024) and mind abilities (Mei et al., 2024). In contrast to these studies, our results suggest that although GPT can vent emotions in various ways, its emotion venting is not behaviorally similar to humans. GPT exhibits more extreme behavior compared to humans. For example, in the DG, all the GPT players punish the dictators for the very unfair distributions, implying GPT consistently exhibits social preference; for unfair distributions, the number of GPT punishers decrease steadily. At any transfer level above 25% of the endowment, no GPT players punish the dictators. In contrast, in F-F’s study, at any transfer level below 50%, ~60% of all human third parties punish the dictators.

Furthermore, we find that the GPT’s fairness norm differs from that of humans, and this may be one reason why GPT exhibits different characteristics from humans in third-party punishment. Combining our data with data from the existing literature (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2004; Andreoni and Bernheim, 2009), GPT considers the dictator to transfer 25% of the endowment consistent with the fairness norm, while humans consider the dictator to transfer 50% as the social norm. Besides, existing research has found that about 25% of human subjects have no social preferences and never punish others (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2004; Fischbacher et al., 2001; Fischbacher and Gächter, 2010), whereas we find that all GPT players have social preferences. This is in contrast to the findings of Mei et al. (2024), who found that GPT showed human-like social preferences.

Our results show that GPT’s emotion venting ability emerges later, and does not behave similarly to humans, which is different from other abilities (Bubeck et al., 2023; Campello de Souza et al., 2023; Kung et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2021; Terwiesch, 2023; Kosinski, 2023; Chen et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024; Goli and Singh, 2024; Rahwan et al., 2019; Hagendorff, 2024; Ye et al., 2023). One possible reason is the difference in the amount of literature available and the difference in the consistency of the conclusions. The paradigms used in these studies tend to be widely used research paradigms, so the literature based on human subjects is extensive. Moreover, the conclusions of these classic studies are basically the same. GPT can train its own behavior patterns from these literatures, so that it can mimic human behavior well and generate human-like behavior. Our focus is on GPT’s ability to vent emotion. Although some studies have investigated the behavioral effects of emotion on punishment, only a few studies have investigated the behavioral effects of emotion venting on direct punishment (Xiao and Houser, 2005; Dickinson and Masclet, 2015; Xu and Houser, 2024; Li et al., 2020; Strange et al., 2016; Kersten and Greitemeyer, 2022; Bolle et al., 2014), and their results are somewhat mixed. Therefore, GPT may produce more errors regardless of whether it imitates human emotion venting or spontaneously produces emotion venting. Therefore, GPT’s emotion venting behavior is not similar to that of humans. Previous studies have found that GPT and human behavior are remarkably similar in many domains beyond language processing (Chen et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024). These studies optimistically suggest that when GPT deviates from human behavior, the deviations are in a positive direction. Our study suggests that one should not only look at the optimistic side of GPT’s deviation behavior, but also look at the negative effects of these deviations, i.e., GPT’s looser fairness norm than that of humans.

Our work highlights the potential of large language models such as GPT to streamline experimental marketing research and generate new data and insights (Horton, 2023; Sudhir and Toubia, 2023; Sætra, 2023; Koc et al., 2023). As a state-of-the-art Generative Pre-trained Transformer model, GPT can not only learn to imitate existing human behavior, but also iteratively generate new human behavior, and these newly generated behaviors provide a good benchmark for understanding human natural intelligence (Meng, 2024; Gui and Toubia, 2023). Our study first designs two situations to explore GPT’s responses when asked to use different messages to vent their emotions. There are no studies in the existing literature that include this type of emotion venting. By synthesizing findings from different domains, our work provides a unique perspective on the nature of emotion venting and expands the methods that can be used to study it.

Our finding that venting emotions through different types of messages can have varying effects provides a strong impetus for future research on the role of message expression in emotion management. This aligns with Nils and Rimé’s (2012) findings that venting negative emotions can compel individuals to reappraise a situation in the same negative way, ultimately reinforcing the original negative experience. Besides, Bushman et al. (1999) demonstrated that participants who read articles supporting catharsis theory and were angered showed a greater desire to hit a sandbag in subsequent activities, whereas those who read anti-catharsis theory articles did not exhibit such behavior. Adena and Huck (2022) found that small changes in wording can affect behavior. Their crowdfunding experiments revealed that using the word “donation” resulted in higher revenue than “contribution,” possibly because “donation” evokes more positive emotional responses, strongly associated with crowdfunding contributions. Christodoulides et al. (2021) also found that restricting consumers’ freedom to express their frustration about a brand by adding guidelines that ask consumers to moderate their speech can decrease the negativity in written complaints and lead to higher levels of consumer-brand forgiveness. Similarly, GPT exhibits sensitivity to the content of emotion venting, as indicated by changes in its subsequent behavior in response to different types of emotional expression.

Conclusion

Our study shows that GPT has the ability to vent emotions and GPT’s emotion venting ability displays an evolutionary trend from chaos in GPT-3.5 to order in GPT-4 and GPT-4o. Although the emotion venting behavior of GPT-4 and GPT-4o has become rational and orderly, showing a trend of human-like behavior, this emotion venting behavior is not similar to humans. We find that the difference in fairness norms may provide a good explanation for this inconsistence.

While prior research has shown that GPT has exhibits excellence in various sophisticated tasks since the GPT-3.5 era or earlier, and that these abilities were already similar or superior to those of humans by the GPT-4 era, our study shows that GPT’s emotion venting ability emerges later than these abilities. This suggests that GPT has emotion venting ability which has traditionally been considered as a uniquely human trait. We need to further understand its capabilities, limitations, and underlying mechanisms to better understand and utilize AI.

Data availability

The data and code used for the analysis are available at https://osf.io/byp9c/?view_only=d99c2ac478ad4248936e48896f5aaf17.

References

Adena M, Huck S (2022) Voluntary ‘donations’ versus reward-oriented ‘contributions’: two experiments on framing in funding mechanisms. Exp Econ 25(5):1399–1417

Andreoni J, Bernheim BD (2009) Social image and the 50–50 norm: a theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica 77(5):1607–1636

Bicchieri C, Xiao E (2009) Do the right thing: but only if others do so. J Behav Decis Mak 22:191–208

Bolle F, Tan JH, Zizzo DJ (2014) Vendettas. Am Econ J-Microecon 6(2):93–130

Bubeck S, Chandrasekaran V, Eldan R, Gehrke J, Horvitz E, Kamar E, Zhang Y (2023) Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712

Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF, Stack AD (1999) Catharsis, aggression, and persuasive influence: Self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies? J Pers Soc Psychol 76(3):367–376

Bushman BJ (2002) Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 28(6):724–731

Camerer CF (2019) Artificial intelligence and behavioral economics. The economics of artificial intelligence: an agenda: 587–608

Campello de Souza B, Serrano de Andrade Neto A, Roazzi A (2023) Are the new AIs smart enough to steal your job? IQ scores for ChatGPT, Microsoft Bing, Google Bard and Quora Poe. (April 7, 2023)

Chen Y, Liu TX, Shan Y, Zhong S (2023) The emergence of economic rationality of GPT. Proc Natl Acad Sci 120(51):e2316205120

Choi JH, Hickman KE, Monahan AB, Schwarcz D (2021) ChatGPT goes to law school. J Leg Educ 71:387–400

Christodoulides G, Gerrath MH, Siamagka NT (2021) Don’t be rude! the effect of content moderation on consumer‐brand forgiveness. Psychol Mark 38(10):1686–1699

Dickinson DL, Masclet D (2015) Emotion venting and punishment in public good experiments. J Public Econ 122:55–67

Elster J (1989) Social norms and economic theory. J Econ Perspect 3(4):99–117

Fehr E, Fischbacher U (2004) Third-party punishment and social norms. Evol Hum behav 25(2):63–87

Fehr E, Gächter S (2002) Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415(6868):137–140

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Fehr E (2001) Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ lett 71(3):397–404

Fischbacher U, Gächter S (2010) Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 100(1):541–556

Goli A, Singh A (2024) Frontiers: can large language models capture human preferences? Mark Sci 43(4):709–722

Gui G, Toubia O (2023) The challenge of using LLMs to simulate human behavior: a causal inference perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.15524

Hagendorff T (2024) Deception abilities emerged in large language models. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(24):e2317967121

Hagendorff T, Fabi S, Kosinski M (2023) Human-like intuitive behavior and reasoning biases emerged in large language models but disappeared in ChatGPT. Nat Comput Sci 3(10):833–838

Horton JJ (2023) Large language models as simulated economic agents: what can we learn from homo silicus? (No. w31122). National Bureau of Economic Research

Kersten R, Greitemeyer T (2022) Why do habitual violent video game players believe in the cathartic effects of violent video games? A misinterpretation of mood improvement as a reduction in aggressive feelings. Aggress Behav 48(2):219–231

Khare SK, Blanes-Vidal V, Nadimi ES, Acharya UR (2023) Emotion recognition and artificial intelligence: a systematic review (2014–2023) and research recommendations. Inf Fusion 102:102019

Koc E, Hatipoglu S, Kivrak O, Celik C, Koc K (2023) Houston, we have a problem!: the use of ChatGPT in responding to customer complaints. Technol Soc 74:102333

Kosinski M (2023) Theory of mind might have spontaneously emerged in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02083

Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, Sillos C, De Leon L, Elepaño C, Madriaga M, Aggabao R, Diaz-Candido G, Maningo J, Tseng V (2023) Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digit Health 2(2):e0000198

Li JP, Cheo R, Xiao E (2020) The effect of voice on indirect reciprocity. Econ Lett 189:108988

Lian Z, Sun L, Sun H, Chen K, Wen Z, Gu H, Liu B, Tao J (2024) Gpt-4v with emotion: a zero-shot benchmark for generalized emotion recognition. Inf Fusion 108:102367

Martı́nez-Miranda J, Aldea A (2005) Emotions in human and artificial intelligence. Comput Hum Behav 21:323–341

Mei Q, Xie Y, Yuan W, Jackson MO (2024) A turing test of whether AI chatbots are behaviorally similar to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(9):e2313925121

Meng J (2024) AI emerges as the frontier in behavioral science. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(10):e2401336121

Nils F, Rimé B (2012) Beyond the myth of venting: social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. Eur J Soc Psychol 42(6):672–681

Nyer PU (2000) An investigation into whether complaining can cause increased consumer satisfaction. J Consum Mark 17(1):9–19

Pillutla MM, Murnighan JK (1996) Unfairness, anger, and spite: emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 68: 208–224

Rahwan I, Cebrian M, Obradovich N, Bongard J, Bonnefon JF, Breazeal C, Crandall JW, Christakis NA, Couzin ID, Jackson MO, Jennings NR, Kamar E, Kloumann IM, Larochelle H, Lazer D, McElreath R, Mislove A, Parkes DC, Pentland A', Roberts ME, Shariff A, Tenenbaum JB, Wellman M (2019) Machine behaviour. Nature 568(7753):477–486

Rathje S, Mirea DM, Sucholutsky I, Marjieh R, Robertson CE, Van Bavel JJ (2024) GPT is an effective tool for multilingual psychological text analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(34):e2308950121

Roberts K, Roberts JH, Danaher PJ, Raghavan R (2015) Practice prize paper—incorporating emotions into evaluation and choice models: application to Kmart Australia. Mark Sci 34(6):815–824

Sanfey AG, Rilling JK, Aronson JA, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD (2003) The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science 300(5626):1755–1758

Sætra HS (2023) Generative AI: here to stay, but for good? Technol Soc 75:102372

Strange S, Grote X, Kuss K, Park SQ, Weber B (2016) Generalized negative reciprocity in the dictator game—How to interrupt the chain of unfairness. Sci Rep 6:22316

Sudhir K, Toubia O (eds) (2023) Artificial Intelligence in marketing. Emerald Publishing Limited

Terwiesch C (2023) Would Chat GPT3 get a Wharton MBA? A prediction based on its performance in the operations management course. Mack Institute for Innovation Management at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 45

Valor C, Antonetti P, Zasuwa G (2022) Corporate social irresponsibility and consumer punishment: a systematic review and research agenda. J Bus Res 144:1218–1233

Waller W (1989) Passion within reason: the strategic role of emotions. J Econ Issues 23(4):1239–1242

Xiao E, Houser D (2005) Emotion expression in human punishment behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102(20):7398–7401

Xu H, Houser D (2024) Emotion expression and indirect reciprocity. Singap Econ Rev 69(04):1537–1558

Ye J, Chen X, Xu N, Zu C, Shao Z, Liu S, Huang X (2023) A comprehensive capability analysis of gpt-3 and gpt-3.5 series models. arXiv preprint arxiv:2303.10420

Yin Y, Jia N, Wakslak CJ (2024) AI can help people feel heard, but an AI label diminishes this impact. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(14):e2319112121

Zhao G, Li Y, Xu Q (2022) From emotion AI to cognitive AI. Int J Netw Dyn Intell 1(1):65–72

Acknowledgements

J.L. acknowledges financial support from the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 22&ZD150) and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant number: ZR2022MG068). W.W. acknowledges financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant number: ZR2024QG048) and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant number: GZC20240935). We also acknowledge financial support from the Key Projects of the Research Program on Undergraduate Teaching Quality and Teaching Reform in Tianjin Ordinary Higher Education Institutions (Grant number: A231006005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W., J.L., W.W. and Y.W. designed research and performed research; G.W., J.L., W.W. and X.N. analyzed data and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Li, J., Wang, W. et al. GPT’s emotion venting and punishment: the evolution from chaos to order. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1948 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06197-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06197-6