Abstract

Although previous research showed social exclusion to be detrimental to psychological functioning, less is known about which factors could make individuals more or less vulnerable to these effects. Employing the Self-Determination Theory as a theoretical framework, this study aimed to examine whether childhood trauma intensifies or mitigates the impact of social exclusion on emotion regulation, basic psychological needs, well-being, and ill-being. An online experiment was conducted, thereby manipulating experienced social exclusion through the Cyberball paradigm. Data were collected through self-reports among 162 participants (Mage = 23.69, SDage = 2.80) who were randomly assigned to either a social exclusion or inclusion condition. Besides higher levels of perceived social exclusion, participants in the exclusion condition reported higher ill-being than those in the inclusion condition (with no significant differences observed in terms of the other outcomes). Results further showed childhood trauma to be positively associated with emotion dysregulation and ill-being, and negatively associated with need satisfaction and well-being. Moreover, childhood trauma moderated the effect of social exclusion on well-being, indicating that high childhood trauma was associated with similar levels of well-being in the exclusion and inclusion condition, whereas individuals with low childhood trauma displayed lower well-being in the exclusion (vs. inclusion) condition. The present study expands current knowledge and deepens our understanding by illuminating the role of childhood trauma as a moderator in the immediate distress caused by social exclusion and the long-term consequences on mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Humans are inherently social, with a fundamental need to belong. This need helps them develop and maintain interpersonal relationships that foster their physical and emotional well-being (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Examining the effects of exposure to social exclusion (SE) is, therefore, imperative. SE is the experience of being deliberately avoided and isolated by an individual or group of people, with or without an explicit expression of dislike (Riva, 2016; Williams, 2007). A specific type of SE is ostracism, which is predominantly characterized by ignoring a person without an explanation or explicit declaration of dislike (Wesselmann et al., 2016). Besides activating pain-related areas of the brain (Eisenberger, 2015), SE has been linked to aggravate psychopathology (Reinhard et al., 2020). The detrimental effects of SE are evident across diverse cultural contexts, indicating its universal impact (Hartgerink et al., 2015). Still, some individuals might be more vulnerable to these detrimental effects of SE. Herein, we focus on childhood trauma (CT), which has been found to relate to psychopathology (McKay et al., 2021), poorer emotion regulation (ER), psychological well-being, and socio-emotional development (Sehgal, 2023). Despite previous research linking CT to rejection sensitivity (Gao et al., 2024), there remains an unexplored gap in comprehending how individuals with CT respond when exposed to SE. Based on the Self-Determination Theory, this study aimed to extend previous research by examining the causal relations from SE to ER, basic psychological needs, well-being, and ill-being while exploring the potential moderating role of CT herein.

Social exclusion and emotion regulation

When experiencing SE, individuals employ ER strategies to mitigate negative emotions and maintain positive feelings. ER generally involves monitoring, regulating, modulating, and modifying emotional responses based on situational demands and personal goals (Gross, 2015; Wang et al., 2022). Within Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 2000), three ER strategies are identified (Roth et al., 2019): emotion integration, characterized by a curious and non-judgmental attitude towards emotions; emotion suppression, which involves concealing negative feelings; and emotion dysregulation, marked by a lack of emotional control resulting in overwhelming experiences. Adaptive ER, such as integration, is linked to social competence (Cole and Deater-Deckard, 2009). In contrast, challenges in ER, like suppression and dysregulation, are associated with greater susceptibility to maladjustment and psychopathology (Nozaki, 2015).

Earlier findings show that SE impairs emotional functioning, with a decline in positive mood and increased feelings of hurt following SE or rejection (Rajchert et al., 2023). A systematic review of Cyberball and self-report data also linked adverse peer experiences (victimization and rejection) with more maladaptive and less adaptive ER (Herd and Kim-Spoon, 2021). Intriguingly, acutely excluded individuals exhibit a bias toward positive emotions, suggesting an unconscious use of positive affect to mitigate negative emotions to avoid psychological trauma (DeWall et al., 2011). Given the differential responses individuals exhibit in their ER strategies following SE, it is crucial to investigate potential moderating factors (e.g., CT) that elucidate this variability. Existing research shows that CT is linked to increased rejection sensitivity (Erozkan, 2015), which impairs the effective regulation of emotional responses towards aversive social stimuli (Silvers et al., 2012). In line with this reasoning, this study examines the potential moderating role of CT in the relation between SE and ER strategies to gain a more nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics involved.

Social exclusion and basic psychological needs

At the core of SDT is the basic psychological needs theory, which posits that individuals have three inherent needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) optimal for psychological functioning and growth (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Autonomy satisfaction is characterized by feelings of volition, choice, and self-endorsement, whereas experienced pressure indicates autonomy frustration (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Feelings of effectiveness and mastery typify competence satisfaction, whereas feelings of ineffectiveness, failure, and helplessness represent competence frustration (Chen et al., 2015). Relatedness satisfaction involves feeling connected, valued and cared for by others, whereas feelings of social alienation, exclusion, and loneliness indicate relatedness frustration (Ryan and Deci, 2017). Satisfaction of these needs fosters well-being, autonomous motivation, positive affect, and self-esteem, whereas need frustration is linked to psychological distress and psychopathology (Ryan and Deci, 2017).

Extant research has established a link between SE and basic psychological needs. A series of experiments by Ricard (2011) demonstrated that SE predicted frustration of all three basic needs (autonomy, relatedness, and competence), while social inclusion led to increased fulfillment. Furthermore, Gao et al. (2024) and Legate et al. (2013) found that ostracism impacted individuals’ needs for autonomy and relatedness (but not competence), with ostracized persons reporting heightened frustration in these areas. Additionally, minor everyday instances of exclusion, whether as the ostracizer or the ostracized, have been found to relate to reduced daily need satisfaction, specifically autonomy and relatedness (Legate et al., 2021). However, there is limited research on the relation between SE and basic psychological needs within the SDT paradigm, and even less is known about what could moderate these relations. Considering CT as a need-thwarting experience, potentially disrupting individuals’ basic psychological needs even before encountering SE, this study investigates how CT may moderate the association between SE and basic needs.

Social exclusion and mental health

Well-being is a multidimensional construct focusing on optimal psychological functioning and growth (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Three frequently proposed dimensions are emotional well-being, which involves experiencing positive emotions; psychological well-being, which encompasses finding meaning in life, autonomy, and personal growth; and social well-being, which involves perceiving opportunities for growth and belonging to the community (Keyes, 2002). Ill-being, on the other hand, is defined as the presence of a non-specific set of psychopathological symptoms, for instance, depression, anxiety, or stress (de Leval, 1995). The dual continua model of mental health suggests that mental well-being and ill-being are related, yet distinct continua (Keyes, 2012, 2013). Most importantly, a lack of ill-being does not assure well-being (Ryff et al., 2006).

Correlational studies linked SE to lower emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Jiang and Ngai, 2020). Similarly, studies on cyber ostracism show that excluded individuals reported lower levels of emotional (but not psychological) well-being than included people (Schneider et al., 2017). However, previous experimental research has primarily focused on either aspects of ill-being or emotional well-being (Lutz, 2023), limiting our understanding of SE’s overall impact on well-being and ill-being altogether. To understand SE’s impact on mental health, this study incorporates well-being and ill-being within a single research model for a distinctive comparison of SE’s impact on ill-being versus well-being while taking CT as a moderator.

Childhood trauma as a moderator

CT encompasses negative life experiences that occurred during childhood, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect, which result in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, and development (World Health Organization WHO (2022)). We will first discuss CT’s relation with our primary outcomes: ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health (i.e., well-being, ill-being).

Focusing on ER, CT has been found to relate to increased dysregulation, avoidance, and suppression of emotions, and reduced emotion integration, with the relation to emotion dysregulation being found for multiple types of CT (Gruhn and Compas, 2020). Only a few studies thus far examined the relation between CT and basic psychological needs, indicating CT to be related to less need satisfaction and more need frustration (Arayici and Sutcu, 2024). Regarding mental health, an abundant amount of research revealed CT to be strongly linked to various adverse mental and physical health outcomes throughout life, from maladaptive psychological functioning to psychopathology (McKay et al., 2021).

Although SE seems to affect individuals universally, some people are likely more sensitive to such experiences than others. SDT employed the principle of “universality without uniformity” (Vansteenkiste et al., 2023), which indicates that there might be differences in the consequences of need-thwarting experiences (e.g., SE) based on a series of factors (e.g., CT) which can cause variation in the strength of associations with the outcomes (e.g., ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health), but not in the direction of the associations. For example, previous research employing the diathesis-stress model indicated that pre-dispositional factors like CT can interact with stressors such as SE to elicit severe psychological responses (Roisman et al., 2012). Less is known, however, about the potential moderating role of CT in the effects of SE from an SDT perspective. Specifically, no study thus far has examined possible interactions between CT and SE in predicting ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health. Given the detrimental direct effects of CT on mental health (Baldwin et al., 2024) and the heightened sensitivity to rejection among individuals with CT (Gao et al., 2024), it is likely that CT exacerbates people’s reactions to SE.

The present study

As detailed above, both SE and CT are detrimental for individuals’ psychological functioning. However, research detailing the effects of SE on ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health is scarce, has provided mixed findings, or has not considered both the bright (e.g., well-being) and dark (e.g., ill-being) sides of functioning. Moreover, it seems likely that individuals’ reactions to SE are diverse, indicating the need to examine possible moderators in these relations. This study, therefore, also focused on the potential moderating role of CT in the effects of SE. As a moderator, CT may influence the severity of the response to SE by amplifying effects on ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health. Further, while SDT has been extensively applied in various contexts, its value in explaining the interactions between SE and CT has yet to be rigorously tested. In sum, this study aimed to examine the causal effects of SE on ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health (i.e., well-being and ill-being) while exploring the possible moderating effects of CT herein. The following four hypotheses were preregistered (see OSF: https://osf.io/hcrnd).

-

H1a: Participants in the SE condition, compared to those in the inclusion condition, report a lower level of adaptive ER, need satisfaction, and well-being;

-

H1b: and a higher level of maladaptive ER, need frustration, and ill-being.

-

H2a: Participants with a higher level of CT, compared to those with a lower level of CT, suffer more from SE as indicated by lower levels of adaptive ER, need satisfaction, and well-being;

-

H2b: and higher levels of maladaptive ER, need frustration, and ill-being.

Method

Participants

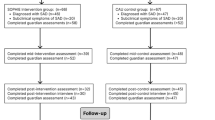

A priori power analysis was conducted to estimate the required sample size (using GPower 3.1; Faul et al., 2009). With α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and a medium effect size of f = 0.25 (Yaakobi, 2021), the desired sample size was 179. A total of 319 individuals initially participated in the study. However, 136 participants were excluded from the analyses because they could not connect to the Cyberball game, had incomplete demographic information or missing responses on questionnaires, and an additional 21 participants were removed for being over the age limit of 30 years. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 162 young adults (74.4% female, 25.3% male, Mage = 23.69, SDage = 2.80, 18–30 years). Based on Banerjee’s (2020) suggestions regarding non-parametric sample sizes in experimental games, this sample size was well-powered at 93%. Our homogeneous sample (mostly young, highly educated female) resulted from recruitment through university networks and social media. While this limits generalizability, it provides a controlled context for examining theoretical relations within specific populations and is methodologically appropriate for establishing baseline effects, as SE varies across different demographic groups (Abrams et al., 2011). Further demographic characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1.

Procedure

The study employed a between-subjects experimental design to investigate the effects of SE using the Cyberball paradigm. All hypotheses and procedures were preregistered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/hcrnd/). Graduate students in the Netherlands recruited participants through convenience and snowball sampling in their social network and via social media (e.g., WhatsApp and Facebook). The survey tool Qualtrics was employed, into which Cyberball was directly integrated. Participants received a detailed information letter outlining the study’s aims, the procedures involved, and the voluntary and anonymous nature of their involvement. Individuals with a psychiatric disorder or those outside the 18–30 age range were deemed ineligible to participate. Upon consenting, participants responded to demographic questions and a CT questionnaire, and were then randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions of the Cyberball paradigm: SE or inclusion. Following Cyberball, participants responded to measures assessing perceived SE (i.e., manipulation check), ER, basic psychological needs, well-being, and ill-being, along with items assessing familiarity and credibility regarding Cyberball. Participants were then debriefed and advised to contact the study supervisor if they experienced discomfort or had concerns. All measures and instructions were in English. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Utrecht University (protocol no. 22-0550).

Cyberball

To induce a state of SE (versus inclusion), the Cyberball (Version 5.4.0.2; Downing and Hales, 2019) paradigm, initially designed by Williams and Jarvis (2006), was employed. Cyberball is a virtual ball-tossing game that stimulates feelings of SE or social inclusion (Williams and Jarvis, 2006). Participants were randomly assigned via Qualtrics to either the SE condition (n = 79) or the inclusion condition (n = 83). The game involved three players (two preprogrammed, one participant) with 30 ball tosses at a 2-second interval over a period of 3 minutes. In the exclusion condition, participants received the ball only 10% of the time (Eres et al. 2021) before being excluded from the rest of the game. In contrast, in the inclusion condition, participants received the ball consistently throughout the game (i.e., 33% of the time).

Measures

Childhood trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2011) was used to assess CT experiences before the Cyberball game. This 28-item self-report instrument consists of five subscales: emotional, physical, sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect. Respondents rated statements (e.g., “I believe that I was physically abused”) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often true), with the scores averaged to calculate a total CT score. The CTQ-SF demonstrated good internal reliability in this study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92.

State social exclusion

After the Cyberball game, participants rated their feelings of being ignored and excluded through 7 items (e.g., “During the game, to what extent did you feel excluded?”) to assess perceived SE, adapted from previous research (Dvir et al., 2019; Holte et al., 2022). Responses on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much so) were aggregated into a composite score. The items demonstrated sufficient reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71.

State emotion regulation

The Emotion Regulation Inventory (ERI; Roth et al., 2019) was employed to assess participants’ ER, focusing on state ER by slightly adapting instructions to assess the regulation of current negative emotions. The ERI has three subscales: dysregulation (e.g., “It is hard for me to control my negative emotions such as sadness or anger”), suppression (e.g., “I try not to express my negative emotion”), and integration (e.g., “I try to understand why I feel negative emotions”), each containing four items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree). All three subscales showed good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for dysregulation at 0.88, suppression at 0.87, and integration at 0.87.

State basic psychological needs

The Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; (Chen et al., 2015) was used to assess participants’ basic psychological needs, with instructions slightly modified for state need satisfaction and need frustration. This 24-item scale covers three needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, relatedness), with 12 items on need satisfaction (e.g., “I feel that my decisions reflect what I really want” for autonomy satisfaction) and 12 items on need frustration (e.g., “Most of the things I do feel like ‘I have to’” for autonomy frustration). Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), and scores were averaged to determine levels of need satisfaction and frustration. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for need satisfaction and frustration were 0.86 and 0.90, respectively.

State well-being

The Mental Health Continuum short form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2012) was used to measure state well-being, with instructions focused on how participants currently felt or thought. This 14-item scale assessed emotional well-being (e.g., “happy”; 3 items), psychological well-being (e.g., “That you like most parts of your personality”; 6 items), and social well-being (e.g., “That people are basically good”; 5 items). Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely), and the total mean score was employed. The scale exhibited good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89.

State ill-being

The Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI − 18; Derogatis, 2017) assessed current psychopathological symptoms via 18 items. The BSI-18 includes subscales for somatization (e.g., “Faintness or dizziness”), anxiety (e.g., “Feeling fearful”), and depression (e.g., “Feeling lonely”). Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely), and the total mean score indicated ill-being. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha of the BSI-18 was 0.91.

Familiarity and credibility concerning Cyberball

At the end of the experiment, four items assessed perceived credibility and familiarity regarding Cyberball (Holte et al., 2022). Specifically, two items assessed credibility (e.g., “How believable was Cyberball to you?”) and showed adequate internal consistency (α = 0.69). The other two items (e.g., “Before this study, did you ever play Cyberball?”) assessing familiarity displayed poor internal consistency (α = 0.35).

Plan of analysis

Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and preliminary analyses were conducted with the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 23). To examine the effects of the background variables (i.e., age, gender, level of education, marital status, and English proficiency), a multivariate (MANCOVA) analysis was conducted with all the study variables as dependent variables. Further, t-test were used to examine if the two conditions were statistically different in terms of predictor and outcome variables. Bivariate correlations were conducted within each of the two experimental conditions. The open-source software R (R: The R Project for Statistical Computing, 2023) with the implementation of the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) was used to test the hypothesized model (Fig. 1) by integrating the bootstrapping approach.

Relations from condition, childhood trauma, and their interaction to emotion regulation, basic needs, well-being, and ill-being. Note. For reasons of clarity, only significant coefficients are reported. The paths from the covariate English proficiency level are not reported. Covariances between variables are not reported. Standardized values are reported. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptives and correlations

Descriptives of and correlations between the study variables are displayed in Table 2. Results showed that CT was significantly and positively associated with emotion dysregulation, frustration, and ill-being while being negatively related to need satisfaction and well-being. Furthermore, emotion dysregulation and suppression were significantly and negatively associated with need satisfaction and well-being, whereas being positively associated with need frustration and ill-being. Emotion integration was positively associated with need satisfaction only. Additionally, there was a significant positive and negative association of need satisfaction with, respectively, well-being and ill-being, while need frustration showed an opposite pattern of relations. Moreover, emotion dysregulation was positively associated with emotion suppression. Finally, a significant negative association was observed between well-being and ill-being and between need satisfaction and frustration. Manipulation checks, the relationship of the background variables, and assumption testing are reported in the Supplementary Material 1. Correlations between the subscales of CT and the outcomes are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

Primary analyses

Condition effects

Subsequently, a MANCOVA was conducted with condition as a fixed factor and English language proficiency as a covariate to examine differences in the mean scores for ER, basic psychological needs, well-being, and ill-being between the two conditions. As displayed in Table 3, no significant differences were observed between the two conditions, except for ill-being. Specifically, participants in the exclusion condition reported higher ill-being than those in the inclusion condition (p = 0.03).

Moderation analysis

Subsequently, a moderation analysis was conducted to examine the possible moderating role of CT in the relations between the condition and the outcomes (i.e., ER, basic psychological needs, well-being, and ill-being). As displayed in Fig. 1 and Table 4, a saturated model was tested. Results showed a significant positive association of CT with emotion dysregulation, a negative association with need satisfaction, and a positive and negative association with ill-being and well-being, respectively (although this latter relation had a standardized coefficient greater than 1, this is acceptable; see also Deegan, 1978; Jöreskog, 1999). Furthermore, condition was unrelated to the outcome variables, except for a significant negative association with well-being (indicating a lower level of well-being in the exclusion condition).

Additionally, a significant interaction effect was found between CT and condition on well-being (see Fig. 2). Participants with low CT exhibited a lower level of well-being in the exclusion compared to the inclusion condition (simple slope = −0.35; t = −2.53; p = 0.01). In contrast, participants with high CT exhibited similar levels of well-being in both conditions (simple slope = 0.17; t = 0.99; p = 0.33). In an explorative fashion (i.e., these analyses were not preregistered), we also examined (1) the possible moderating role of the subscales of CT and (2) the moderating role of overall CT in the relation between condition and the satisfaction or frustration of the three needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Results of these analyses can be found in Supplementary Material 2.

Discussion

Grounded in the SDT framework, the two primary aims of this study were (1) to examine the effects of SE on ER, basic psychological needs, and mental health, and (2) to investigate whether CT might moderate these relations. First, the manipulation with the Cyberball paradigm succeeded, as participants reported higher SE in the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition. Our findings partly support hypothesis H1b, showing higher ill-being in the SE than in the inclusion condition. However, the other hypotheses lacked support, as no significant differences appeared between conditions in adaptive/maladaptive ER, need satisfaction, need frustration, and well-being, and CT moderated SE's relation with well-being in an unexpected manner.

Social exclusion and emotion regulation

We anticipated higher maladaptive and lower adaptive ER in the SE versus inclusion condition (H1a, H1b); however, no significant differences in ER strategies were observed across both conditions. The findings contradict previous research linking adverse peer experiences to increased maladaptive and decreased adaptive ER (Herd and Kim-Spoon, 2021). Methodological differences may explain the contrasting results we obtained. First, unlike previous studies that focused on mood alterations, attachment styles, and clinical samples, our study focused on the association between SE and ER among a convenience sample. Second, the brief Cyberball manipulation may lack the intensity or duration needed to elicit ER strategies. Third, individuals without ER difficulties often recover rapidly from the effects of Cyberball manipulation (Hartgerink et al., 2015). Additionally, our immediate assessments may have missed delayed ER response, and the factors of psychological inflexibility and resilience in our homogenous sample might have moderated such responses (Cobos-Sánchez et al., 2022). Further research should investigate the role of individual differences, such as ER difficulties, resilience, and psychological flexibility, in the relation between SE and ER.

Social exclusion and basic needs

We expected lower need satisfaction and higher need frustration in the SE versus inclusion condition (H2a, H2b), however, no significant differences were observed across both conditions. This contradicts prior findings linking SE to reduced need satisfaction and increased relatedness frustration (Ricard, 2011).

Several factors might explain these null results. For instance, the brief Cyberball manipulation may not have had a sufficiently significant impact on basic needs compared to the real-life SE experience. Moreover, the artificial nature of Cyberball may have reduced ecological validity, as participants likely viewed the game as temporary and impersonal, not effecting the needs at all. Additionally, prior Cyberball studies (e.g., Lutz, 2023; Seidl et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022) primarily examined Williams’s (2009) fundamental needs, rather than SDT needs. A few studies that reveal significant associations between SE and basic needs from an SDT perspective (Legate et al., 2013, 2021) employed different experimental conditions (ostracizing, neutral, and compliance) and populations (workers and students), which limit comparability with our findings. These methodological variations may help explain the contrasting findings in this study. Future research should consider SE in real-life situations and individual differences in assessing the link between SE and basic needs from an SDT perspective.

Social exclusion and mental health

We hypothesized that participants would show lower well-being and higher ill-being in the SE versus inclusion condition. However, no significant between-condition differences were found in either condition for well-being, disconfirming our hypothesis (H1a). This finding is inconsistent with past studies reporting a negative association between SE and emotional well-being (Schneider et al., 2017). Several factors may explain this finding. First, previous studies employed different methods (e.g., subtypes of well-being, social media-induced stress) or clinical samples, which limit comparability with our findings. Second, well-being is relatively stable and may not alter after a brief Cyberball-induced SE experience (Houben et al., 2015), which participants may not perceive as potentially threatening due to the vertical position of participants’ avatars in the Cyberball game that influenced their expectations of SE, leading to reduced negative impact on their well-being (Schuck, Niedeggen, and Kerschreiter, 2018). Third, the organism-environment interaction model (Lerner et al., 2006) suggests that individual characteristics (e.g., personality traits, resilience, coping strategies) and environmental factors (e.g., SE) jointly shape developmental outcomes (e.g., well-being). Our highly educated sample may have had protective factors that buffered the impact of SE on their well-being.

Interestingly, participants reported higher levels of ill-being in the SE condition than in the inclusion condition, supporting the (H1b) hypothesis. This resonates with previous research linking SE to depression (Filia et al., 2025). This finding is explained well with the dual pathway model (Vansteenkiste et al., 2023), which posits that exposure to adverse environments (e.g., SE) has a more pronounced impact on the development of maladaptive outcomes (e.g., ill-being) than on adaptive outcomes (e.g., well-being). The differential impact of SE on well-being and ill-being in our findings suggests that these outcomes are two distinct constructs (Ryff et al., 2006), implying that the presence of one does not necessarily imply the absence of the other. Additionally, the nature of the items in the survey could offer another explanation. Specifically, participants responded to ill-being items in a narrow, emotion-focused context (e.g., loneliness; Franke et al., 2017), while well-being items reflected broader evaluations (e.g., satisfaction with one’s personality; Keyes, 2002). This difference in item scope may explain the divergent findings related to well-being and ill-being. Future research should examine real-life SE, individual factors, and how the breadth of measurement influences the effect of SE on both well-being and ill-being.

The moderating role of childhood trauma

CT significantly moderated the relation between SE and well-being, although this moderation was not in line with our hypothesis (H2a). Specifically, individuals with low CT experienced lower well-being in the exclusion versus inclusion condition, whereas those with high CT experienced similar levels of well-being in both conditions. This suggests that low CT magnifies the detrimental effects of SE, while stable well-being among high CT individuals may reflect experiential avoidance. Such avoidance entails the tendency to avoid or escape negative internal experiences (e.g., thoughts, emotions, and memories), and has been consistently associated with CT (Lewis and Naugle, 2017). Moreover, individuals with higher levels of CT also show reduced dACC activation following ostracism (van den Berg et al. (2018)), indicating lower sensitivity to SE. This reduced sensitivity to SE and the use of experiential avoidance might explain the stable levels of well-being among individuals with high CT during both SE and inclusion.

Several factors may contribute to the null moderation effect of CT on the relations between SE and ER strategies, basic needs, and ill-being. First, brief SE experiences with Cyberball might primarily impact physiological responses (e.g., high blood pressure) (Eres et al. 2021), without immediately translating into detectable changes in psychological outcomes, which require more time to process. Additionally, CT’s influence on the relations between SE, ER, basic needs, and ill-being may operate through more complex mechanisms (non-linear relations) rather than simple moderation, which traditional interaction analyses could not capture (Duprey et al., 2023; McLaughlin and Lambert, 2017). Future research should integrate physiological markers and individual differences with psychological outcomes in a longitudinal, real-life investigation to capture the influence of CT on responses to SE.

Furthermore, exploratory findings with the subscales of CT (i.e., emotional abuse, emotional neglect, minimization and denial) showed that people with high scores on these subscales were less affected by the negative effects of SE on emotion dysregulation, need satisfaction, and well-being. Specifically, higher emotional abuse (compared to lower) was associated with decreased emotion dysregulation during the exclusion versus inclusion condition. Higher emotional neglect and minimization/denial were associated with similar levels of need satisfaction and well-being in the exclusion versus inclusion condition. Physical neglect and sexual abuse showed no significant interaction effect, and no CT subscale interacted with SE on emotion suppression, emotion integration, need frustration, or ill-being. These findings suggest responses to SE vary by CT type, highlighting the need to examine how distinct types of trauma influence ER, basic needs, and well-being in the context of SE.

The main effects of childhood trauma

Our findings revealed several main effects of CT. CT was positively associated with emotion dysregulation and need frustration, and negatively associated with need satisfaction. This corroborates previous findings linking CT with heightened maladaptive ER, ER difficulties, need frustration, and reduced need satisfaction (Geng et al., 2022; Rashid et al., 2024). Second, CT was negatively associated with well-being, mirroring previous research linking CT to reduced psychological well-being (Sehgal, 2023; Volgenau et al., 2023). However, no significant association emerged between CT and ill-being. Individual factors (e.g., resilience) or current stressors (e.g., SE) may explain this, as recent experiences may have a more potent effect on ill-being than past trauma (Hu et al., 2024). Additionally, our immediate assessment of ill-being may not capture CT’s broader temporal impact. Lastly, exploratory findings with the subscales of need satisfaction and frustration (i.e., autonomy, competence, relatedness) revealed that CT was associated with reduced autonomy and relatedness satisfaction, and increased autonomy and relatedness frustration.

Limitations and future research

This study had several important strengths. First, it is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the moderating role of CT in the relation between SE, ER, basic needs, well-being, and ill-being. Moreover, the experimental design to examine SE’s causal effects is a crucial strength of this study. Additionally, our hypotheses were pre-registered, and sample size was justified both parametrically and non-parametrically, enhancing the transparency and replicability of our findings.

The present study, however, has several limitations. First, the homogeneity of our sample (primarily young, highly educated females) limits the generalizability of our findings. As SE responses vary across age groups and clinical populations (Abrams, Rutland (2011); Seidl et al., 2020), our results are not applicable to male participants, older adults, adolescents, or individuals with clinical conditions. Future research should include more diverse samples with balanced gender representation. Moreover, this study’s cross-sectional design limits insight into the moderation effect. Future longitudinal research could better capture the long-term impact of CT and SE by using self-reported data in conjunction with clinical interviews or third-party reports for a more comprehensive assessment of CT over time.

Furthermore, this study relied on self-reported measures, which may introduce bias due to social desirability or recall errors. Methodologically, retrospective reports on maltreatment can differ from prospective reports in 50% of their responses due to potential recall biases (Baldwin et al., 2024). Lastly, though not the goal of our study, future research could explore how personality traits, attachment styles, and coping strategies shape responses to SE among individuals with CT.

Practical implications

Beyond extending SDT by showing how CT and social contexts shape psychological and emotional processes, our findings offer several practical implications. First, practitioners should routinely evaluate trauma history (specifically, emotional abuse and neglect), and rejection sensitivity. Trauma-informed therapists should consider diverse responses to SE among individuals with high CT, requiring interventions beyond inclusion-focused approaches. Practitioners should incorporate coping skills training to mitigate the impact of SE on ill-being. At the same time, community programs and schools should provide targeted ER training and basic needs assessments for socially excluded individuals to reduce the adverse impact of SE and to improve the well-being. This refines conventional social skills programs into trauma-informed, evidence-based practices.

Although the observed interaction effects were modest, they reflect typical moderation magnitudes in psychological research (Aguinis et al., 2005) and can have significant application over time (Funder and Ozer, 2019). Even minor effects, when contextualized within trauma-informed frameworks, can provide meaningful insights for intervention strategies in clinical, educational, and digital domains.

Conclusion

By integrating SE and SDT frameworks, our study examined the causal effects of SE on ER, basic needs, and well-being, and the moderating role of CT herein. We found that SE predicted higher ill-being, though no effects emerged for ER, basic needs, or well-being. Additionally, CT significantly moderated the SE-well-being link, with individuals with high CT experiencing similar levels of well-being during the exclusion and inclusion condition. Furthermore, exploratory analyses with the subscales of CT provided significant interactions between (1) emotional abuse and SE on emotion dysregulation, (2) emotional neglect and SE on need satisfaction and well-being, and (3) minimization and denial, and SE on need satisfaction and well-being. These findings contribute to a better understanding for both researchers and practitioners into how past CT may impact responses to SE and provide pathways for further exploration by incorporating individual differences and coping mechanisms in real-life context.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the OSF repository, [https://osf.io/hcrnd/]. Data are stored securely at the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Utrecht University, in accordance with ethical approval (Protocol No. 22-0550) and European data protection regulations (GDPR).

References

Abrams D, Weick M, Thomas D, Colbe H, Franklin K (2011) On-line ostracism affects children differently from adolescents and adults. Br J Dev Psychol 29:110–123. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151010X494089

Abrams D, Rutland A (2011) Children’s understanding of social exclusion: developmental perspectives and strategies to reduce prejudice. In: Levy SR, Killen M (eds) Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood (pp. 211–230). Oxford University Press

Aguinis H, Beaty JC, Boik RJ, Pierce CA (2005) Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: a 30-year review. J Appl Psychol 90(1):94–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.94

Arayici S, Sutcu S (2024) The relationship between childhood trauma, exercise addiction, emotion regulation difficulties, and basic psychological needs in Türkiye. J Clin Sport Psych 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2023-0036

Baldwin JR, Coleman O, Francis ER, Danese A (2024) Prospective and retrospective measures of child maltreatment and their association with psychopathology: a systematic review and meta- analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0818

Banerjee S (2020) Sample sizes in experimental games. Res Econ 74(3):221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2020.07.002

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J (2011) Childhood trauma questionnaire [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.1037/t02080-000

Chen B, Vansteenkiste M, Beyers W, Boone L, Deci EL, Van der Kaap-Deeder J, Duriez B, Lens W, Matos L, Mouratidis A, Ryan RM, Sheldon KM, Soenens B, Van Petegem S, Verstuyf J (2015) Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv Emot 39(2):216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Cobos-Sánchez L, Flujas-Contreras JM, Becerra IG (2022) Relation between psychological flexibility, emotional intelligence and emotion regulation in adolescence. Curr Psychol 41(8):5434–5443

Cole PM, Deater-Deckard K (2009) Emotion regulation, risk, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50(11):1327–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02180.x

de Leval N (1995) Scales of depression, ill-being and the quality of life—is there any difference? An assay in taxonomy. Qual Life Res 4(3):259–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02260865

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deegan J (1978) On the occurrence of standardized regression coefficients greater than one. Educ Psychol Meas 38(4):873–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447803800404

Derogatis LR (2017) Symptom checklist-90-revised, brief symptom inventory, and BSI-18. In Handbook of Psychological Assessment in Primary Care Settings (2nd ed). Routledge

DeWall CN, Deckman T, Pond Jr. RS, Bonser I (2011) Belongingness as a core personality trait: how social exclusion influences social functioning and personality expression. J Personal 79(6):1281–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00695.x

Downing and Hales (2019) Cyberball [computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.empirisoft.com/cyberball.aspx.Retrieved 1 July 2020. [Computer software]. https://www.empirisoft.com/cyberball.aspx

Duprey EB, Handley ED, Russotti J, Tyrka AR, Cicchetti D (2023) A longitudinal examination of child maltreatment dimensions, emotion regulation, and comorbid psychopathology. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51:71–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-00913-5

Dvir M, Kelly JR, Williams KD (2019) Is inclusion a valid control for ostracism? J Soc Psychol 159(1):106–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1460301

Eisenberger NI (2015) Meta-analytic evidence for the role of the anterior cingulate cortex in social pain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu120

Eres R, Bolton I, Lim MH, Lambert GW, Lambert EA (2021) Cardiovascular responses to social stress elicited by the Cyberball task. Heart Mind 5(3):73–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/hm.hm_31_21

Erozkan A (2015) The childhood trauma and late adolescent rejection sensitivity. Anthropologist 19:413–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2015.11891675

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A et al. (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Filia K, Teo SM, Brennan N, Freeburn T, Baker D, Browne V, Gao CX (2025) Interrelationships between social exclusion, mental health and wellbeing in adolescents: insights from a national Youth Survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 34:e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796024000878

Franke GH, Jaeger S, Glaesmer H, Barkmann C, Petrowski K, Braehler E (2017) Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 17(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0283-3

Funder DC, Ozer DJ (2019) Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 2(2):156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

Gao S, Assink M, Bi C, Chan KL (2024) Child maltreatment as a risk factor for rejection sensitivity: a three-level meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence Abus 25(1):680–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231162979

Geng J, Bao L, Wang H, Wang J, Gao T, Lei L (2022) Does childhood maltreatment increase the subsequent risk of problematic smartphone use among adolescents? A two-wave longitudinal study. Addict Behav 129:107250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107250

Gross JJ (2015) Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq 26(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Gruhn MA, Compas BE (2020) Effects of maltreatment on coping and emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Child Abus Negl 103:104446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104446

Hartgerink CHJ, Beest I, van, Wicherts JM, Williams KD (2015) The ordinal effects of ostracism: a meta-analysis of 120 cyberball studies. PLoS One 10(5):e0127002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127002

Herd T, Kim-Spoon J (2021) A Systematic review of associations between adverse peer experiences and emotion regulation in adolescence. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 24(1):141–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00337-x

Holte AJ, Fisher WN, Ferraro FR (2022) Afraid of social exclusion: fear of missing out predicts cyberball-induced ostracism. J Technol Behav Sci 7(3):315–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-022-00251-9

Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, Kuppens P (2015) The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 141(4):901–930. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038822

Hu H, Chen C, Xu B, Wang D (2024) Moderating and mediating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences among college students. BMC Psychiatry 24(1):273. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05719-x

Jiang S, Ngai SS (2020) Social exclusion and multi-domain well-being in Chinese migrant children: exploring the psychosocial mechanisms of need satisfaction and need frustration. Child Youth Serv Rev 116:105182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105182

Jöreskog KG (1999) How large can a standardized coefficient be? https://www.statmodel.com/download/Joreskog.pdf

Keyes CLM (2002) The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 43(2):207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Keyes CLM (ed) (2012) Mental well-being: international contributions to the study of positive mental health (2013th edn). Springer

Keyes CLM (2013) Promoting and protecting positive mental health: early and often throughout the lifespan. In: Keyes CLM (ed), Mental Well-Being (pp. 3–28). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8_1

Legate N, DeHaan CR, Weinstein N, Ryan RM (2013) Hurting you hurts me too: the psychological costs of complying with ostracism. Psychol Sci 24(4):583–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612457951

Legate N, Weinstein N, Ryan RM (2021) Ostracism in real life: evidence that ostracizing others has costs, even when it feels justified. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 43(4):226–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2021.1927038

Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Almerigi J, Theokas C (2006) Dynamics of individual context relations in human development: a developmental systems perspective. In: Thomas JC, Segal DL, Hersen M (eds), Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology, Vol. 1. Personality and Everyday Functioning (pp. 23–43). John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Lewis M, Naugle A (2017) Measuring experiential avoidance: evidence toward multidimensional predictors of trauma sequelae. Behav Sci 7(1):Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010009

Lutz S (2023) Why don’t you answer me?! Exploring the effects of (repeated exposure to) ostracism via messengers on users’ fundamental needs, well-being, and coping motivation. Media Psychol 26(2):113–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2101008

McKay MT, Cannon M, Chambers D, Conroy RM, Coughlan H, Dodd P, Healy C, O’Donnell L, Clarke MC (2021) Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 143(3):189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13268

McLaughlin KA, Lambert HK (2017) Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: mechanisms of risk and resilience. Curr Opin Psychol 14:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.004

Nozaki Y (2015) Emotional competence and extrinsic emotion regulation directed toward an ostracized person. Emotion 15(6):763–774. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000081

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing (2023) Retrieved 31 October 2023, from https://www.r-project.org/

Rajchert J, Konopka K, Oręziak H, Dziechciarska W (2023) Direct and displaced aggression after exclusion: role of gender differences. J Soc Psychol 163(1):126–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2022.2042173

Ricard N (2011) Effects of social exclusion and inclusion on basic needs satisfaction, self-determined motivation, the orientations of interpersonal relationships, and behavioural self-regulation

Reinhard MA, Dewald-Kaufmann J, Wüstenberg T, Musil R, Pogarell O (2020) The vicious circle of social exclusion and psychopathology: a systematic review of experimental ostracism research in psychiatric disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 270(5):521–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01074-1

Riva P (2016) Emotion regulation following social exclusion: psychological and behavioral strategies. In: Riva P, Eck J (eds), Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact (pp. 199–225). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33033-4_10

Roisman GI, Newman DA, Fraley RC, Haltigan JD, Groh AM, Haydon KC (2012) Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis–stress: recommendations for evaluating interaction effects. Dev Psychopathol 24(2):389–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000065

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48:1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Roth G, Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM (2019) Integrative emotion regulation: Process and development from a self-determination theory perspective. Dev Psychopathol 31(3):945–956. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000403

Rashid A, Costa S, Van der Kaap-Deeder J (2024) The role of childhood trauma in young adults’ emotion regulation, psychological needs, and psychological functioning. J Trauma Dissociat Off J Int Soc Study Dissociat (ISSD) 26(2):178–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2024.2429474

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2017) Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications

Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, Davidson RJ, Singer B (2006) Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom 75(2):85–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090892

Schneider FM, Zwillich B, Bindl MJ, Hopp FR, Reich S, Vorderer P (2017) Social media ostracism: the effects of being excluded online. Comput Hum Behav 73:385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.052

Sehgal R (2023) The effects of childhood trauma on emotional regulation and psychological well being in young adults. Tuijin Jishu/J Propuls Technol 44:462–472. https://doi.org/10.52783/tjjpt.v44.i4.864

Seidl E, Padberg F, Bauriedl-Schmidt C, Albert A, Daltrozzo T, Hall J, Renneberg B, Seidl O, Jobst A (2020) Response to ostracism in patients with chronic depression, episodic depression and borderline personality disorder a study using Cyberball. J Affect Disord 260:254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.021

Silvers JA, McRae K, Gabrieli JDE, Gross JJ, Remy KA, Ochsner KN (2012) Age-related differences in emotional reactivity, regulation, and rejection sensitivity in adolescence. Emotion 12(6):1235–1247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028297

Schuck K, Niedeggen M, Kerschreiter R (2018) Violated expectations in the cyberball paradigm: testing the expectancy account of social participation with ERP. Front Psychol 9:1762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01762

van den Berg LJM, Tollenaar MS, Pittner K, Compier-de Block LHCG, Buisman RSM, van IJzendoorn MH, Elzinga BM (2018) Pass it on? The neural responses to rejection in the context of a family study on maltreatment. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 13(6):616–627. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy035

Vansteenkiste M, Ryan RM, Soenens B (2020) Basic psychological need theory: advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv Emot 44(1):1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

Vansteenkiste M, Soenens B, Ryan RM (2023) Basic psychological needs theory: a conceptual and empirical review of key criteria. In Ryan RM (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197600047.013.5

Volgenau KM, Hokes KE, Hacker N, Adams LM (2023) A network analysis approach to understanding the relationship between childhood trauma and well-being later in life. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(4):1127–1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01321-y

Wang T, Mu W, Li X, Gu X, Duan W (2022) Cyber-ostracism and well-being: a moderated mediation model of need satisfaction and psychological stress. Curr Psychol 41(7):4931–4941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00997-6

Wesselmann, ED, Grzybowski, MR, Steakley-Freeman, DM, DeSouza, ER, Nezlek, JB, Williams, KD (2016) Social exclusion in everyday life. In Riva P, Eck J (eds), Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact (pp. 3–23). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33033-4_1

Williams KD (2007) Ostracism. Annu Rev Psychol 58(1):425–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

Williams KD, Jarvis B (2006) Cyberball: a program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behav Res Methods 38(1):174–180. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192765

World Health Organization (WHO) (2022) Retrieved 8 May 2024, from https://www.who.int

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Asma Rashid conceived and designed the study, conducted data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Jolene van der Kaap-Deeder contributed to the experimental data collection design and provided detailed feedback throughout the research and writing process. Sebastiano Costa assisted in the process of data analysis and offered critical feedback on the manuscript draft. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of Utrecht University with approval number 22-0550 on 02/12/ 2022. The procedures used in this research adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

All participants provided written informed consent online before participation. After reading an information letter describing the study’s aims, procedures, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time, participants gave consent via the Qualtrics platform between December 13, 2022, and January 11, 2023. Only after providing consent could, they proceed to the study. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their data and that it would be used solely for research and publication purposes. After completing the study, they were fully debriefed about the deception involved in the Cyberball manipulation. The study also included safeguards such as distress monitoring and the provision of mental health support resources. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rashid, A., Costa, S. & van der Kaap-Deeder, J. The effects of social exclusion on emotion regulation, basic needs, well-being, and ill-being: examining the moderating role of childhood trauma. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06220-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06220-w