Abstract

Emergency nurses (EN) are exposed to workplace violence and mental health (MH) disorders. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of empowerment in anger management on the mental health of nurses working in an emergency department). The present intervention study was conducted in the emergency department of Hospital in Iran during 2020. Sixty nurses who met inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to either a control or intervention group. Participants in the intervention group received an anger management treatment conducted in eight sessions within one month. The participants’ mental health was assessed before the intervention and after the one- month intervention using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire. The data were analyzed using SPSS version21. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of the demographic variables (p < 0.05). The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the control and intervention groups before the study were 7.11 and 6.92, respectively, and also there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.718). The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the control and intervention groups one month after the study were 7.01 and 6.01, respectively. The ANCOVA test results demonstrated that no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (p = 0.013). Educating and empowering EN regarding anger management could help improve their mental status. Considering the importance of this issue, nursing managers and educators should take the necessary efforts to incorporate anger management training for nurses working in ED settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), workplace violence is defined as “incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, and involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health”. It is considered as one of the serious dangers that threatens hospital staff, such that the highest prevalence of workplace violence occurs in hospitals (Sahebi et al. 2011). Exposure to workplace violence can be seen more often among nurses working in the emergency departments, since they are more likely to encounter aggressive patients and their caregivers daily, who want the emergency procedures to be performed more quickly (Arik et al. 2012; Teymourzadeh et al. 2014). The previous studies indicated that in recent years, the incidence of violence against nurses has increased in emergency departments (Al-Qadi 2020). In one large study performed in China in 2016, the prevalence of workplace violence among about 30,000 nurses was assessed. The results of the study revealed that nearly 50% of the participants had experienced some types of workplace violence in the past year. The results of the study also revealed that the prevalence of violence against nurses working in the emergency department was significantly higher compared to other hospital wards (Wei et al. 2016). In another study conducted in the United States in 2014, 75% of nurses reported that they had experienced some types of violence in their workplace in the past year (Speroni et al. 2014). The results of one review study performed in Iran in 2018 showed that 74% and 28% of Iranian nurses had experienced the verbal and physical violence in their workplace, respectively (Dalvand et al. 2018).

Being employed in the nursing profession can place considerable stress on a person and put him/her at risk of mental health problems (Nikolaou et al. 2020). The incidence of mental health problems not only negatively affects a nurse’s health, but also reduces the quality of his/her performance in providing nursing care (Perry et al. 2015). In their study, Cheung and Yip (2015) found that more than one-third of nurses participating in their study suffered from some degrees of depression, stress, and anxiety (Cheung and Yip 2015). The results of one national study on nearly 6,000 nurses in Iran revealed that ~70% of Iranian nurses were at risk of mental health disorders (Kheyri et al. 2017). One of the factors contributing to the nurses’ mental health is their exposure to workplace violence (Arik et al. 2012; Bordignon et al. 2016). In their study, Zhang et al. (2018) revealed that nurses who were exposed to greater workplace violence were significantly more stressed (Zhang et al. 2018). In one qualitative study performed in Iran during 2019, Iranian nurses believed that after experiencing workplace violence, they suffered psychological problems, such as distress and depression (Hashemi-Dermaneh et al. 2019). Another study indicated that workplace violence could cause excessive stress and the subsequent medication use in nurses (Havaei, and MacPhee 2020).

Previous studies revealed that empowering nurses regarding anger management could be highly effective in reducing violence against them in the emergency departments (Eslamian et al. 2010; Kalbali et al. 2018). Given the positive effects of empowering nurses regarding anger management in reducing workplace violence, and the relationship between workplace violence and mental health disorders among nurses; therefore, it is hypothesized that the mental health of training emergency department nurses working in anger management would improve. A review of relevant literature revealed that one study had tested this hypothesis. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of empowerment in anger management on mental health of nurses working in the emergency department.

Materials & methods

This was an experimental study was conducted in Iran during 2020. The study participants were randomly assigned to a control or intervention group. The study environment was the emergency department of one of the teaching hospitals affiliated to a University of Medical Sciences in the southeast of Iran.127 registered nurses worked in this emergency department that mostly admitted trauma patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) having at least six months of work experience in the emergency department, (ii) experiencing some type of workplace violence in the past six months according to nurses’ self-report, and (iii) providing informed consent to participate in the study. The rationale for selecting participants who had experienced workplace violence in the past six months was to ensure the inclusion of individuals at greater risk of psychological distress, particularly anger and emotional dysregulation. Previous studies showed that recent exposure to workplace violence could significantly increase stress and anger levels, making these individuals more suitable for evaluating the effectiveness of anger management interventions (Dalvand et al. 2018; Havaei and MacPhee 2020; Lee et al. 2021; Sayaheen et al. 2024). Participants who were absent from two or more intervention sessions or were not available to complete the post-test questionnaires were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling

The sample size was determined using the following formula. In this regard, z1 and z2, considering a 95% confidence level and test power of 0.8 from the normal distribution table, were equal to 1.96 and 0.84, respectively. Therefore, taking these figures into account, the minimum sample required for each group was 25, and by estimating a drop out percentage as 20% for various reasons based on our previous experience in study among emergency nurses, the study sample was 60.

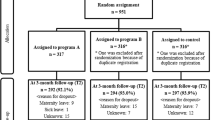

The sample comprised 60 nurses who met the inclusion criteria. After preparing an initial list of eligible nurses, 60 were selected through a convenience sampling method. Then, they were randomly divided into two equally-sized groups (n = 30 per group) using the random number table. Allocation to the participants into intervention and control groups was performed by a nurse manager who was unaware of the groups and study methods.

Intervention

Participants in the control group did not receive any intervention. The subjects in the intervention group participated in an anger management program. The program was performed over eight sessions (two sessions per week). The duration of each session was two hours between 10 and 12 A.M. The sessions were held in a classroom at the hospital. The content of the anger management program included: 1) conceptualization: discussing the nature of anger and how people react to it. This stage was conducted through discussing one’s anger experiences in the past; 2) acquisition of skills and practiced: Using coping strategies with a cognitive-behavioral approach. At this stage, the person practiced the learned skills under the supervision of a therapist; and, 3) application and follow-up: this component included the application of learned skills in real life. To reach this stage, the person was faced with anger-provoking situations. All the classes were administered by a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, and a psychiatric nurse.

Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the study procedure.

Data gathering tools

The demographic information of participants in both groups was collected using a researcher-made checklist. The participants’ mental health was assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). This questionnaire consists of 12 items, and it is a self-administered screening questionnaire. This questionnaire examines the ability to concentrate, loss of sleep due to worry, playing a useful part, capability of making decisions, feeling constantly under strain, inability to overcome difficulties, ability to enjoy day-to-day activities, ability to face problems, feeling unhappy and depressed, losing confidence, thinking of self as worthless, and feeling reasonably happy over the past few weeks. A bimodal scoring method of 0-0-1-1 is used for scoring each item. Total score ranges from 0 to 12 where the higher scores indicate worse health. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire has been reported to be high among Iranian nurses (Tagharrobi et al. 2015).

Analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS version 21. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test used to determine normality of the data. ANCOVA test was employed to determine whether the difference between the mean scores of mental health of the control and intervention groups was significant. Paired t-tests were applied to compare the mean scores of mental health in each group before and after the intervention. descriptive tests (such as mean and frequency) were used to describe the demographic variables. P value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 54 nurses completed the study. One participant in the intervention group withdrew in the middle of the study due to personal reasons. Two other participants in this group did not complete the questionnaire after the intervention. Three participants in the control group did not complete post-test questionnaire and were excluded from the study. No statistically significant differences were observed between both groups with respect to the demographic variables including age, sex, education level, and work experience (p < 0.05).

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the participants’ demographic characteristics. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, education level, or work experience (p > 0.05 for all variables).

Mental health before the intervention

The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the control and intervention groups before the study were 7.11 and 6.92, respectively. The independent t-test results showed that this difference was not statistically significant between the two groups (p = 0.718).

Mental health one month after the intervention

The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the control and intervention groups after one- month intervention were 7.01 and 6.01, respectively. The ANCOVA test results showed that this difference was statistically significant between the two groups (p = 0.013). The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the control group before and one month after the intervention were 7.11 and 7.01, respectively. The paired t-test results demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference in this group in terms of the mean scores before and one month after the intervention in (p = 0.774). The mean scores of mental health among nurses in the intervention group before and one month after the intervention were 6.92 and 6.01, respectively. The results of paired t-test revealed that the statistically significant difference was found in this group in terms of the mean scores before and one month after the intervention (p = 0.017). Table 2 indicates the participants’ responses to 12 items of the General Health Questionnaire in details.

Discussion

It is necessary to consider the mental health of nurses working in emergency departments and use strategies to intervene where necessary. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of implementing an anger management program on the mental health of Iranian nurses working in the emergency department. The results of the present study revealed that participation in anger management program can significantly improve the mental health of nurses.

A review of the relevant literature revealed that one previous study examined the effect of anger management on nurses’ mental health. In the study researchers investigated the effect of anger management mindfulness program on psychiatric nurse’s mental health. Aligning with what we found, previous studies reported that anger management mindfulness program significantly improved psychiatric nurse’s mental health (Ando et al. 2022). To the best of our knowledge, three studies examined the effect of the implementation of an anger management program on the rate of workplace violence among nurses working in the emergency departments. Two studies were conducted in Iran and one in Australia. In the first study performed in 2010, Eslmian et al. evaluated the effect of anger management program on violence rate against nurses in an emergency department. The population of the study consisted of 60 nurses. In their study, Eslmian et al. showed that the participation of emergency nurses in anger management program significantly reduced the incidence of psychological violence rate against them. The results also showed that the incidence of physical violence was not affected by the participation of nurses in anger management program and in fact, the incidence of such violence against nurses was not different before and after the intervention (Eslamian et al. 2010). In their study, Kalbali et al. (2018) examined the impact of an anger management training, including face-to-face classes and online training, on controlling workplace violence among 112 nurses working in the emergency departments. Kalbali et al. also showed that participation in anger management training could empower nurses in controlling workplace violence and consequently reduce the incidence of workplace violence against them (Kalbali et al. 2018). In a third study conducted in Australia, the effectiveness of a short training program on the behavior of nurses working in an emergency department in the face of workplace violence and the incidence of such violence was examined. The results of the study showed that participation in such training program increased the knowledge and changed the attitudes of nurses working in the emergency department in relation to workplace violence and ultimately reduced the incidence of workplace violence against nurses by up to 50% (Deans 2004). Previous study showed that nurses with lake of anger management ability experience more work challenges, such as more aggression during work time, more occupational violence, more work stress, increased mental fatigue, and burnout that negatively affect their mental health (Ando et al. 2022; Farahani and Ebadie Zare 2018; Lee et al. 2021; Tanabe et al. 2023). In the present study, it seems that by training nurses working in the emergency department regarding anger management, they could manage this daily issue in the emergency department more effectively and as a result, were less exposed to workplace violence, resulting in a significant improvement in their mental health.

Previous studies demonstrated that nurses responded to workplace violence in different ways (Arik et al. 2012). In many cases, responses to workplace violence take the form of anger, fear, anxiety and long-term stress, inadequacy and shame, and guilt, which is inappropriate and harmful, and in long-term, can affect all aspects of one’s health, including mental health (Needham et al. 2005). Nurses usually do not receive the necessary education on anger management and how to deal with workplace violence while studying at nursing schools and when starting work in a hospital. In this regard, one study performed in 2019 showed that nearly 96% of nurses did not receive the necessary education om the management of workplace violence (Alam et al. 2019). It seems that the implementation of anger management programs for emergency nurses should be considered by hospital managers. In addition, educating nurses while studying at nursing schools as nursing students in this regard can also be helpful.

Conclusions

The mental health of nurses working in emergency departments can affect their performance. The results of the present study revealed that the empowerment of emergency nurses regarding anger management could significantly improve their mental health. The results of the present study can be used by nursing managers in order to implement educational programs in relation to anger management and empower emergency nurses. In addition to empowering nurses, other issues, such as the implementation of prevention programs and guidelines, and reporting cases related to workplace violence should also be considered by managers to protect emergency nurses. Given the lack of similar studies, it is therefore recommended that further studies be conducted in this regard, especially multi-center studies to enhance the generalizability of findings.

Limitations

The present study was performed on nurses working in an emergency department, so the findings cannot be generalized to those working in other wards or settings. Therefore, it is recommended that more studies be conducted on larger sample sizes. Risk of sampling biases and systematic errors should be considered because we used convenience sampling method.

Data availability

The datasets used in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alam MD, Latif A, Rani Mallick D, Khaleda Akter M (2019) Workplace violence among nurses at public hospital in Bangladesh. EAS J Nurs Midwifery 1(5):148–154

Al-Qadi MM (2020) Nurses’ perspectives of violence in emergency departments: a metasynthesis. Int Emerg Nurs 52:100905

Ando M, Kukihara H, Kurihara H (2022) Development of anger management mindfulness program and effects on mental health and fatigue of psychiatric nurses. Open J Soc Sci 10(5):488–495

Arik C, Anat R, Arie E (2012) Encountering anger in the emergency department: identification, evaluations and responses of staff members to anger displays. Emerg Med Int 2012:603215

Bordignon M, Monteiro MI (2016) Violência no trabalho da Enfermagem: um olhar às consequências. Rev Brasileira de Enferm 69:996–999

Cheung T, Yip PS (2015) Depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress among Hong Kong nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(9):11072–11100

Dalvand S, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Najafi F, Zahednezhad H, Sayehmiri K (2018) The prevalence of workplace violence against Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta - analysis. Shiraz E-Med J 19(9):e65923

Deans C (2004) The effectiveness of a training program for emergency department nurses in managing violent situations. Aust J Adv Nurs 21(4):17–22

Eslamian J, Fard SH, Tavakol K, Yazdani M (2010) The effect of anger management by nursing staff on violence rate against them in the emergency unit. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 15(Suppl 1):337–342

Farahani M, Ebadie Zare S (2018) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral anger management training on aggression and job satisfaction on nurses working in psychiatric hospital. Zahedan J Res Med Sci 20(2):e55348

Hashemi-Dermaneh T, Masoudi-Alavi N, Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M (2019) Nurses’ experiences of workplace violence in Kashan/Iran: a qualitative content analysis. Nurs Midwifery Stud 8:203–209

Havaei F, MacPhee M (2020) Effect of workplace violence and psychological stress responses on medical-surgical nurses’ medication intake. Can J Nurs Res 53(2):134–144

Kalbali R, Jouybari L, Derakhshanpour F, Vakili MA, Sanagoo A (2018) Impact of anger management training on controlling perceived violence and aggression of nurses in emergency departments. J Nurs Midwifery Sci 5:89–94

Kheyri F, Seyedfatemi N, Oskouei F, Mardani-Hamooleh M (2017) Nurses’ mental health in Iran: a national survey in teaching hospitals. SJKU 22(4):91–100

Lee HY, Jang MH, Jeong YM, Sok SR, Kim AS (2021) Mediating effects of anger expression in the relationship of work stress with burnout among hospital nurses depending on career experience. J Nurs Scholarsh 53(2):227–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12627

Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, Fischer JE, Dassen T (2005) Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 49(3):283–296

Nikolaou I, Alikari V, Tzavella F, Zyga S, Tsironi M, Theofilou P (2020) Predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms among Greek nurses. JHSCI 10(1):90–98

Perry L, Lamont S, Brunero S, Gallagher R, Duffield C (2015) The mental health of nurses in acute teaching hospital settings: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs 14(1):15

Sahebi L, Gholamzadeh Nikkjoo R (2011) Workplace violence against clinical workers in Tabriz Educational Hospitals. IJN 24(73):27–35

Sayaheen B, Ahmad MM, Al-Maaitah R (2024) The association between workplace violence and psychological distress among nurses working in psychiatric hospitals in Jordan. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 62(2):15–22. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20241205-02

Speroni KG, Fitch T, Dawson E, Dugan L, Atherton M (2014) Incidence and cost of nurse workplace violence perpetrated by hospital patients or patient visitors. J Emerg Nurs 40(3):218–228

Tagharrobi Z, Sharifi KH, Sooky Z (2015) Psychometric analysis of Persian GHQ-12with C-GHQ scoring style. Prevent Care Nurs Midwifery J 4(2):66–80

Tanabe Y, Asami T, Yoshimi A, Abe K, Saigusa Y, Hayakawa M, Hishimoto A (2023) Effectiveness of anger‐focused emotional management training in reducing aggression among nurses. Nurs Open 10(2):998–1006

Teymourzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Akbari-Sari A, Hakimzadeh SM (2014) Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching hospital in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag 3(6):301–305

Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, Huang N (2016) Workplace violence against nurses-prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 56:63–70

Zhang SE, Liu W, Wang J, Shi Y, Xie F, Cang S et al. (2018) Impact of workplace violence and compassionate behaviour in hospitals on stress, sleep quality and subjective health status among Chinese nurses: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 8(10):e019373

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the vice president of research at Bam University of Medical Sciences and the participating nurses (All emergency nurses and All staff). This study was funded by the Bam University of Medical Sciences. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, data collection, and interpretation of results or in writing the manuscript [Grant No. 99/029].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJ, JJ, AN and TIB contributed to conceiving and designing the study. The data collection was done by TIB and AA. MJ, HR and JJ analyzed and interpreted the data. MJ, JB, HR, and AN wrote the first draft of the manuscript and translated it. MJ, AN and JB consulted and supervised the process of research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Bam University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.MUBAM.REC.1399.029) on April 25, 2020.

Informed consent

Before recruiting participants, all involved nurses were thoroughly informed about the study’s aims and procedures. The researchers conveyed the objectives and methods to the participants, who were then asked to read and sign the informed consent form prior to being allocated to study groups on May 10, 2020. Participants were made aware of the purpose and nature of the study, the procedures involved, and their right to withdraw at any time without facing any penalties. Their responses were guaranteed confidentiality, with clear explanations provided regarding the anonymization of their data, secure storage, exclusive use for research purposes, and protection against unauthorized access. The potential risks and benefits of participation were transparently communicated. Furthermore, contact details for both the research team and the ethics committee were given to address any questions or concerns. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nassehi, A., Ilaghinezhad Bardsiri, T., Rafiei, H. et al. Effect of an anger management program on mental health of nurses working in an emergency department. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06227-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06227-3