Abstract

Large gaps in the implementation of climate policies pose a challenge to the achievement of greenhouse gas emission reduction targets. The lack of incentives in the cadre performance evaluation system (CPES) for climate governance constitutes a major cause of the implementation gap. Against this backdrop, the Chinese government has initiated a cadre performance evaluation system transformation (CPEST) in some counties, aiming to reshape the GDP-centred evaluation system. The study links the CPEST to six climate policies and assesses the impact of mixing the two on carbon emissions, employing county-level data spanning 2008-2022 and applying the Difference-in-Differences (DID) model. The study reveals notable synergistic effects between climate policy and CPEST. This effect is particularly prominent in mandatory climate policies and weaker in market-based climate policies. Further tests indicate that goal alignment significantly boosts the synergistic effect between CPES and climate policy when CPES shifts to prioritise green development. Time order is also important; climate policies implemented prior to CPEST contribute to enhancing the mixing effects of the two, yet this contribution is insufficient to generate synergistic effects. The mixing effects of the two are also affected by officials’ characteristics. Specifically, stronger mixing effects are more closely linked to officials who are younger, female, hold a master’s degree, and work in their hometowns. Mechanism analyses show that industrial structure upgrading, green technology innovation, environmental fiscal expenditure, and environmental penalties are the main ways in which policy mixing promotes carbon reduction. However, only the latter three mechanisms can generate policy synergistic effects. The study’s findings offer a significant reference for improving the efficacy of climate policies and reducing carbon emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change poses a threat to human society via over 400 pathways (Mora et al., 2018). The IPCC’s AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023 indicates that, given current greenhouse gas emissions, global temperatures are projected to increase by over 1.5°C by 2030, making it challenging to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to less than 2°C. Given the public nature of climate change, climate policy is regarded as a vital tool for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Governments worldwide have rolled out numerous ambitious climate policies. By 2020, countries involved in the IPAC (International Programme for Action on Climate) had adopted an average of 31 climate policies (Nachtigall et al., 2022). However, a study revealed that just 63 of the 1,500 climate policies implemented across various countries achieved the anticipated carbon reductions (around 4%) (Stechemesser et al., 2024). This further implies that the mitigation gap in climate policies lies not in the adoption gap, but in the often overlooked outcome gap in policy implementation (Fransen et al., 2023).

Why have numerous climate policies been implemented with less effectiveness than anticipated? Poor design, low acceptability, inadequate funding, and weak institutional capacity have been identified as key reasons for the outcome gaps in policy implementation (Goedeking, 2025; Milhorance et al., 2022). And another key barrier that is often overlooked is the discrepancy between climate goals and the performance targets (incentives) of local officials (Patterson, 2023; Struthers, 2020; Wu, 2023). The “bottom-up” policy implementation approach posits that local governments’ will shape the actual policy outcomes (Lipsky, 2010). A growing body of research has also revealed that numerous climate policies fail to generate incentives for achieving goals, resulting in officials lacking political zeal (Guo et al., 2021; Hjerpe et al., 2015). Conflicting climate policy goals and local officials’ economic evaluation targets have also led many climate policies to remain on ineffective policy agendas and programmes (Marks, 2010; Wu, 2023).

However, the existing literature still lacks clear insights into whether and how redesigning the cadre performance evaluation system (CPES) can enhance the effectiveness of current climate policies. Current literature has solely conducted independent assessments of the effectiveness of climate policies and the cadre performance evaluation system in reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Du et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024; Stechemesser et al., 2024; Zeng & Bao, 2024; Zeng et al., 2023). Only a few studies have offered some indirect evidence (reasonable speculation) regarding whether the two can mutually reinforce each other (Lin & Xie, 2023; Lin & Xu, 2022; Struthers, 2020). With the advent of the New Public Management (NPM) movement, governments around the world have nearly all established a sophisticated cadre performance evaluation system (CPES) to enhance bureaucratic efficiency and facilitate the execution of the central government’s will. Hence, in this pivotal decade for achieving the UN climate goals, understanding the impact of CPES on the effectiveness of climate policy implementation is especially urgent and significant.

To bridge existing research gaps, we analyse six representative climate policies currently being implemented in China and link them to the cadre performance evaluation system transformation (CPEST) at the county level in the country. The full removal of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) assessment indicator from CPEST offers a unique opportunity to investigate the synergistic carbon reduction impacts between CPES and climate policy. Our study makes three key contributions to the existing climate policy literature.

Firstly, there are few studies offering direct evidence on how the combination of climate policy and CPES impacts carbon emissions. Using quasi-natural experimental scenarios and detailed data from China, we establish a connection between the two and identify their synergistic effects, generation conditions, and mechanisms.

Secondly, we effectively identify the scope of CPES’s role by examining a broader range and diverse types of climate policies. This research contributes incremental knowledge, facilitating a better understanding and application of CPES to enhance the effects of climate policies.

Thirdly, numerous studies confine themselves to using only provincial or city-level data; we present evidence at the more granular county level. This enables a more detailed analysis of the carbon reduction effects of climate policies and provides more reliable evidence. At the same time, we also utilise data regarding county officials to probe more thoroughly into the role of political elites in policy mixing.

Background, framework, and hypotheses

Policy type and background

Policy classification

The classifications of many climate policy instruments overlap, making it difficult to accurately categorize different climate policies. Moreover, clarifying climate policy types facilitates a more in-depth understanding of the role of CPES in climate policy. Based on the policy’s reliance, climate policy instruments can be broadly divided into market-based policies (relying on market means), mandatory policies (relying on administrative means), and hybrid policies (a combination of the two) (Howlett et al., 1995; Nachtigall et al., 2022). While purely market-based or mandatory policies are straightforward to identify, hybrid policies show a bias either towards market-based policies or mandatory policies. To avoid overly complex policy classifications, we classify climate policies along a continuous spectrum that combines market and administrative means. A schematic diagram is presented in Fig. 1. In this context, the closer a policy is to either end of the spectrum, the more clearly it exhibits characteristics of mandatory or market-based policies. Policies in the middle are hybrid, showing a preference for either market-based or mandatory means. The subsequent section offers a brief overview of various climate policies and the CPEST programme.

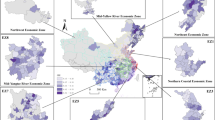

a Distribution of CETP. b Distribution of ERTP. c Distribution of LCCP. d Distribution of AQESP. e Distribution of VMSR. f Distribution of CEPI. This maps is only for illustration and should not be seen as precise geographic data or official boundaries. Detailed policy information should be obtained through official government documents.

Policy background

Following the policy classifications, we provide a brief description of each climate policy in turn.

(1) The carbon emissions trading policy (CETP) is a market-based climate policy that employs market mechanisms to encourage enterprises to transition to a low-carbon model (Jing et al., 2024). It has demonstrated a more effective carbon reduction outcome (Du et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2022). Launched in 2013, the policy was initially implemented in seven provinces and cities, including Beijing and Hubei. In 2016, it was also rolled out in Fujian (Fig. 1a). (2) The energy rights trading policy (ERTP) is another typical market-based policy aimed at energy conservation and emission reduction. It primarily achieves carbon emission reduction by regulating the total amount and intensity of energy consumption (Pan & Dong, 2022). This policy was implemented in four Chinese provinces in 2017 (Fig. 1b). (3) The Low-carbon city policy (LCCP) is a hybrid climate policy that integrates market-based and administrative means (Zou et al., 2022). This programme, guided by the government, aims to foster the development of the market (green technology, green industry, and green economy). As a result, it leans towards market-based policies (Wu et al., 2023). The LCCP was initiated with three rounds of pilot projects in 2010, 2012, and 2017, respectively (Fig. 1c).

(4) The air quality ecological subsidy policy (AQESP) is a hybrid climate policy that integrates government and market elements. It employs mandatory administrative measures to direct ecological compensation funds from cities with worsening ambient air quality to those with improved conditions (Chang et al., 2024). It is thus essentially grounded in administrative means, yet employs market means to provide economic incentives. The policy was launched in 2014, after which several other provinces and municipalities began to implement it (Fig. 1d). (5) The vertical management system reform of environmental protection agencies (VMSR) is a mandatory policy aimed at addressing the weak institutional capacity in climate governance (Li et al., 2024). It has been implemented in some provinces and cities since 2016 and extended nationwide in 2020 (Fig. 1e). (6) The central environmental protection inspection (CEPI) is a mandatory climate policy that relies on administrative measures. It aims to curb officials’ connivance in polluting and high-carbon emitting activities by strictly holding them accountable for pollution incidents (Lin & Xie, 2023; Tan & Mao, 2021). The programme initiated its first round of inspections in 2016 and launched a second round in 2017 (Fig. 1f). Figure 1 presents the timelines and coverage regions of each climate policy. A more detailed description of these policies is provided in Appendix A.

The cadre performance evaluation system transformation (CPEST) is a programme launched by the Chinese central government in selected counties to better attain the objective of high-quality development. In China, the cadre performance evaluation system significantly shapes officials’ behavioural patterns. China has long established a GDP-centric cadre performance evaluation system. This system made a significant contribution to China’s economic growth miracle (Li & Zhou, 2005), yet it also led to environmental pollution and a widening urban-rural income gap (Chen & Ye, 2025; Liu et al., 2024). In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed at the National Organization Work Conference that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) should no longer serve as a sole criterion for evaluating cadres. This marked the beginning of the transformation of China’s cadre performance evaluation system. In 2014 alone, over 300 county governments implemented the CPEST, completely removing the GDP indicator from the cadre performance evaluation system (CPES). By 2022, approximately 490 county governments had implemented this reform, accounting for around 17% of all districts (Fig. 2). After removing the GDP indicator, CPEST also set distinct new high-incentive targets (such as ecological priority and poverty alleviation priority) based on the specific conditions of each county. This signifies a fundamental shift in the CPES for these districts and counties.

Research framework and hypotheses

Climate governance typically operates within a multi-level structure. Much of the implementation gap arises from the selective enforcement of central (higher-level) government climate policies by local (lower-level) governments (Fransen et al., 2023). CPES shapes the behavioural tendencies of officials and governments (Li & Zhou, 2005), influencing the policy implementation process and outcomes (Zeng & Bao, 2024). Meanwhile, for public-pool resources like climate, cross-level institutional or policy analysis is both necessary and beneficial (Ostrom, 1990). Thus, we regard the impact of CPES on climate policy implementation within a multilevel structure as the starting point and foundational framework for our analysis (Fig. 3).

Under the GDP-centric CPES, local governments exhibit low willingness to implement climate policies (Wu, 2023). This stems from the fact that strict enforcement of such policies will lead to a short-term economic growth slowdown (Bretschger, 2017; Lin & Jia, 2019), which is detrimental to officials’ performance evaluation and promotion prospects. The complete removal of the GDP indicator from CPES will alleviate officials’ concerns, thereby enhancing their willingness to strictly enforce climate policies. Consequently, the integration of CPEST and climate policy generates synergistic effects overall. Furthermore, CPEST is more inclined to generate synergistic effects with mandatory policies (based on administrative means), as it directly regulates government behaviour. In contrast, its impact on market-based policies is relatively indirect, making it difficult to create direct synergistic effects. According to institutional theory, governments engage indirectly in markets by safeguarding property rights and upholding social contracts (North, 1990). Consequently, the alterations in government behaviour induced by CPEST can only exert a limited influence on the market. In summary, we put forward the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis H1: CPEST can generate synergistic effects with mandatory climate policies, but it cannot directly generate synergistic effects with market-based climate policies.

Goal misalignment stands as a significant factor undermining the synergistic effect between policies (Rogge & Reichardt, 2016). For a long time, China’s county economies have primarily relied on high-carbon industries, such as manufacturing, energy, and traditional agriculture. With GDP as the key promotion metric under the cadre performance evaluation system, officials are unlikely to actively support climate policies during their brief tenures (Meng et al., 2019). At this point, the cadre performance evaluation system presents a significant conflict of goals with climate policy. A CPEST that goes beyond GDP orientation can help to directly mitigate the conflict of these goals. In fact, the county-level implementation of CPEST has generally led to the emergence of three new performance evaluation systems: Rural development priority (centred on poverty reduction and agricultural advancement), Green development priority (focused on environmental and ecological protection), and multi-objective concurrency (with no specific priorities). Among these, green development priority is well-aligned with the goals of climate policy. For instance, the new performance targets for these counties explicitly incorporate and assign greater weight to indicators like reducing carbon dioxide emissions, air pollutants, energy consumption, and greening rates. Hence, if county governments establish a new performance evaluation system prioritising green development, they can foster a stronger synergistic effect with climate policies. Simultaneously, CPEST directly affects government actions. As a result, CPEST prioritises green development will be more prominent in mandatory climate policies based on administrative means. In brief, we propose a second hypothesis accordingly.

Hypothesis H2: Goal alignment can foster a synergistic effect, particularly for climate policies dependent on administrative approaches.

Policy mixing occurs not only across space but also over time (Rayner et al., 2017). Policy instruments affect their counterparts in the same domain via extensive feedback loops (Edmondson et al., 2019). This interactive dynamic means that the initially implemented policy has the capacity to shape subsequent ones. Consequently, the time order of policy implementation influences their combined effects. On the one hand, climate policy functions as the primary instrument, and the cadre performance evaluation system transformation (CPEST) serves as the secondary one. Once climate policy is prioritised as the main tool, supplementing it with an appropriately adapted secondary tool (CPEST) can improve the policy mixing effect (Bali et al., 2022). Consequently, under the influence of climate policy, CPEST is more inclined to incorporate climate governance-related indicators during its reform. On the other hand, within the nested institutional framework, higher-tier institutions systematically influence lower-tier ones (Ostrom, 2011). The hierarchical position of climate policies (at the city level) is markedly higher than CPEST (at the county level). Consequently, if high-level climate policies are introduced first, they may shape the specific content and implementation direction of subsequent low-level CPEST, thereby aligning CPEST more closely with climate policy objectives. Certainly, although time order may offer benefits, the impact via policy feedback is constrained. It can only partially shape subsequent policies, lacking the capacity to induce fundamental changes. Consequently, it is inadequate to foster the generation of a synergistic effect. Based on this, we formulate Hypothesis H3.

Hypothesis H3: An appropriate time order contributes to enhancing the hybrid effect between climate policy and CPEST, but not enough to create a synergistic effect.

CPEST primarily influences the effectiveness of climate policy implementation by regulating officials’ behaviour. Consequently, the implementation efficacy of CPEST is also contingent upon the characteristics of officials. Firstly, CPEST fundamentally influences officials’ behaviour by providing incentives. Officials are more inclined to respond to the new cadre performance evaluation system when they harbour higher promotion expectations. Within the Chinese government, age is a key factor limiting promotion, with younger age indicating greater promotion prospects (Wang et al., 2020). Accordingly, the younger local principal officials are, the more likely they are to respond to the CPEST, thereby reinforcing the policy mixing effect. Secondly, women’s heightened sense of social responsibility and empathy render them more attentive to long-term environmental benefits (Zelezny et al., 2000). Research has also demonstrated that female government officials are instrumental in formulating policies that produce better carbon reduction outcomes (Wu, 2025). Thus, following the removal of the GDP target, female officials in charge are more inclined to exert greater efforts in enhancing environmental quality, thereby contributing to a more robust policy mixing effect. Thirdly, education enhances cognitive abilities (Ritchie & Tucker-Drob, 2018). Officials with higher educational attainment are more likely to grasp the core orientation (the sustainability orientation) of CPEST and comprehend the long-term ramifications of climate governance, thereby making decisions that are more beneficial to the effective implementation of climate policies. Thus, a higher level of educational attainment among officials corresponds to a greater capacity to reinforce the policy mixing effect. Fourthly, officials exhibit hometown preferences and are inclined to make decisions that facilitate the long-term development of their hometowns (Do et al., 2017). Climate governance and carbon reduction typically represent long-term development strategies. Consequently, officials serving in their hometowns are more inclined to respond to climate policies once the GDP target ceases to be assessed. In summary, we hereby propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis H4: The characteristics of officials affect the CPEST and climate policy mixing effect. Officials who are younger, female, highly educated, and serve in their hometowns contribute to enhancing the policy mixing effect.

Market and government mechanisms serve as crucial means for climate policies to achieve carbon emission reductions. Firstly, achieving low-carbon development requires reaching the “inflection point” of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) (Grossman & Krueger, 1995). This is primarily accomplished through green technological innovation and industrial structure upgrading. Climate policy offers a range of conditions for stakeholders to engage in climate governance. These encompass carbon trading regulations (e.g., CETP), restrictions on energy misuse (e.g., ERTP), technology subsidies (e.g., LCCP), financial compensation mechanisms (e.g., AQESP), the enhancement of institutional capacity (VMSR), and environmental accountability systems (CEPI). These initiatives will facilitate green technological innovation and industrial structure upgrading, ultimately contributing to carbon emission reduction. The removal of GDP-based assessment will help reduce the government’s concern about implementing climate policies, thereby enhancing the carbon-reduction impact of the aforementioned mechanisms. Secondly, when market failure occurs, government environmental regulation serves as a complementary approach to curbing carbon emissions. Before the abolition of the GDP-based assessment (a scenario of incentive deficiency), officials typically fulfilled their environmental regulatory duties in a formalistic manner due to considerations of economic growth (Meng et al., 2019; Wu, 2023). This is evident in the low proportion of environmental protection expenditures and the inadequate deterrent effect of environmental penalties. Following the abolition of the GDP-based assessment, the newly introduced strong incentives (eco-prioritization) and climate policies will impose dual pressure on local governments. Consequently, local governments will give priority to enhancing administrative tools, such as environmental fiscal expenditure and environmental penalties, to achieve carbon emission reduction. Therefore, under the policy mixes, the above governmental mechanisms will have a more significant carbon reduction effect. Based on this, we put forward the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis H5: The combination of CPEST and climate policies can drive carbon emission reduction by promoting industrial structure upgrading, fostering green technological innovation, increasing fiscal expenditure on environmental protection, and imposing stricter environmental penalties.

Research design

Identification methods

The Difference-in-Differences (DID) model can effectively circumvent systematic errors and endogeneity issues, thereby accurately identifying the policy treatment effects (Lin & Xie, 2023; Stechemesser et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2023). It is highly appropriate for evaluating the effects of the above policies implemented in selected regions. Therefore, our model is designed as follows:

\({Carbon}_{it}\) denotes carbon emissions. \({Policy}_{it}^{Climate}\) denotes each climate policy, marking 1 for the year of implementation and subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. \({Policy}_{it}^{CPEST}\) denotes CPEST, with 1 for the year of implementation and subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. \({Policy}_{it}^{Climate+CPEST}\) denotes a mix of climate policies and CPEST, with 1 for the year of implementation and subsequent years in which the county implements both climate policies and CPEST, and 0 otherwise. \({{X}_{it}}\) represent a series of control variables. \({{\gamma}_{it}}\) is a time-fixed effect, and \({{\delta}_{it}}\) is a county-fixed effect. \({\alpha }_{1}\), \({\alpha }_{2}\), \({\alpha }_{3}\) are intercept terms. \({\beta }_{1}\), \({\beta }_{2}\), \({\beta }_{3}\) capture the policy treatment effects, by comparing these three coefficients, we can determine whether there is a synergistic effect between climate policy and CPEST. Finally, \({{\mu}_{it}}\) is a random error term.

By assessing the six climate policies, CPEST, and their combinations with the aid of (1)–(3), we can calculate the mixing effect between climate policies and CPEST(Wu et al., 2023). Drawing on relevant studies(del Río, 2014), our criteria for determining the policy synergistic effect are presented in Fig. 4. If \(\mid{\beta }_{3}\mid \!>\! \mid{\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{2}\mid\), the synergistic effect can be deemed to exist.

Variables and data

We use panel data for 1578 counties from 2008 to 2022. The dataset contains three components: carbon emissions, policy data, and economic and social data. In line with relevant studies (Stechemesser et al., 2024), the carbon emissions data are sourced from the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR). This data offers three advantages for this study. First, EDGAR data exhibits high accuracy. The Chinese carbon emissions data it provides generally aligns with trends observed in other data sources (Xia et al., 2024). Second, compared to other datasets, the grid-level data (0.1° × 0.1°) provided by EDGAR enables us to calculate carbon emissions at the county level. Third, although EDGAR cannot substitute for high-precision local emission inventories, its data, marked by global consistency, long-term coverage, and comprehensiveness, act as a systematic and comparable source of county-level emission data for evaluating policy impacts. Drawing on the Chinese government’s common criteria for policies (Wang et al., 2015), we measure carbon intensity as the amount of carbon emissions (in 100,000 tons) per RMB one billion of GDP. To mitigate heteroskedasticity, the relevant data are subjected to a logarithmic transformation (Lyu et al., 2023). The policy data are compiled by the research team from government documents, official websites, and news reports.

Economic and social data are mainly used to construct the mechanism variables and control variables. They come from county statistical yearbooks, county statistical bulletins on national economic and social development, government websites, and the EPS statistical platform. The mechanism variables include industrial structure upgrading (ISU), green technology innovation (GTI), environmental fiscal expenditure (EFE) and environmental penalties (EP). ISU is measured using the cosine angle of the unit vectors of the first, second, and third industries (Wu & Liu, 2021). GTI is expressed as the logarithm of the number of green patent applications. County-level data are obtained by aggregating from a patent database according to the green patent classification number (Dong et al., 2020). EFE is measured by taking the proportion of environmental protection expenditures in fiscal expenditures. It is obtained by weighting county fiscal expenditures as a share of city from city environmental expenditures. EP is measured using the logarithm of the number of environmental penalty cases. These cases are sourced from the PKULAW database. Detailed measurements of mechanism variables are provided in Appendix B. The control variables consisted of three dimensions, economic, policy and physical geographic characteristics, totalling nine variables. Appendix B reports the measurement criteria and descriptive statistics of the main variables.

Empirical analyses

Examination of the effect of individual policy

We evaluate the carbon reduction effect of each of the six climate policies and CPEST. The results in Fig. 5 show that CETP, ERTP, LCCP, VMSR and CPEST all reduce county carbon emissions at the 1% significance level. The carbon reduction effects of AQESP and CEPI are not significant. More detailed information on the regression results can be found in Appendix C. The estimates derived from AQESP and CEPI align with existing research, indicating that these policies are ineffective in sustained carbon reduction (Chang et al., 2024; Pan, 2025). These results suggest that most climate policies and CPEST have a significant carbon reduction effect. However, two mandatory policies, AQESP and CEPI, exhibit no significant carbon reduction effects at the county level, suggesting that policy instruments relying on administrative means may have led to an implementation gap.

Examination of policy mixing effects

This section focuses on examining whether the mix of climate policies and CPEST could have a greater carbon reduction effect. We assess the carbon reduction effects of each of the six climate policies mixed with CPEST. The results in Fig. 6 show that the mixing effect of market-based climate policies (CETP, CRTP, and LCCP) with CPEST is less than the linear sum of the two (not satisfying \(\mid{\beta }_{3}\mid \!>\! \mid\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}\mid\)) and does not produce a significant synergistic effect. In contrast, the mixing effect of mandatory climate policies (AQESP, VMSR, and CEPI) and CPEST is greater than the linear sum of the two (satisfying \(\mid{\beta }_{3}\mid \!>\!\mid\beta_{1}+\beta_{2}\mid\)) and produces a significant synergistic effect. These results suggest that CPEST does not have a synergistic effect with all climate policies, but it can generate a significant synergistic effect when mixed with climate policies based on administrative means. The results support Hypothesis H1.

Parallel trend tests and placebo tests

Parallel trend tests

The DID model must satisfy the parallel trends assumption. We use the event study method to test each policy (both single and mixed) that has significant carbon reduction effects. As shown in Fig. 7, the pre-event estimated coefficients for each policy and their mixture with CPEST are insignificant. The data analysis results align with the parallel trends assumption. Given that staggered DID may produce estimation biases due to the heterogeneity of treatment effects. To enhance the reliability of parallel trends, we also re-evaluated using two heterogeneity-robust DID models (Callaway & Sant’Anna, 2021; Sun & Abraham, 2021). Appendix D details the parallel trend test model and presents the estimation results for the new model. The findings in Appendix D indicate that the parallel trend holds even after accounting for estimated bias.

Placebo tests

To eliminate the possibility of chance, we also perform placebo tests for each policy with a notable carbon reduction effect. Specifically, we generate 1,000 spurious ‘time-area’ shocks for each policy. If the true estimates differ significantly from the false ones, it indicates that the policy effects are not due to chance. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the true effects of all policies (represented by red dashed lines) differ significantly from the spurious ones, with all p-values on the left being below 0.1. Hence, it can be inferred that the estimates are not randomly generated and the results are robust.

Robustness tests

To ensure the robustness of the estimates, we also perform the following four tests.

Firstly, exogenous policy interference is excluded. We mainly exclude the potential impact of atmospheric control policies. These policies include: The Announcement on the Implementation of Special Emission Limits for Air Pollutants, issued in February 2013. The Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Air Pollution, issued in September 2013. The Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Battle for the Blue Sky, published in 2018. We create dummy variables based on policy treatment timing and location, and incorporate them into regression models to eliminate these confounding factors. As shown in Appendix D(Fig. 4), the estimates align with the baseline results.

Secondly, we take into account the impacts of vegetation and transport conditions. Research has demonstrated that vegetation (particularly forests) and high-speed railways exert significant carbon-reduction effects (Lin et al., 2021; Wu, 2025). We further control for these factors to reduce potential disturbances. We primarily measure vegetation conditions using the normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI). The data are sourced from the MOD13A3 dataset published by NASA. High-speed rail is measured based on whether a county has high-speed rail services. For a county with high-speed rail services, the value is set to 1 in the year of opening and subsequent years; otherwise, it is 0. As depicted in Appendix D(Fig. 5), the new estimates still align with the baseline results after accounting for the effects of vegetation and traffic conditions.

Thirdly, interference among samples within the policy mixes is alleviated. On the one hand, when evaluating individual policy effects, we exclude control-group samples influenced by another policy. On the other hand, when assessing policy mixing effects, we eliminate control-group samples affected by a single policy. For example, for CETP and CPEST, we exclude control-group samples affected by CPEST while assessing CETP. Similarly, when evaluating CPEST, we eliminate control-group samples influenced by CETP. When evaluating the mixing of CETP and CPEST, we removed control-group samples influenced by either CETP or CPEST. With regard to VMSR and CEPI, two policies that were gradually rolled out across the board, we reduce the disturbance by including another policy as a control variable. For instance, when evaluating VMSR, CPEST is incorporated into the control variables. When assessing the mixing effect of VMSR and CPEST, policy shock dummies for VMSR and CPEST are added to the control variables. Along these lines, we evaluate each of the six climate policies and CPEST and their mixing effects. Due to space constraints, the estimation results are presented in Appendix E. The results can still support the previous conclusions.

Fourthly, we reduce the interference of heterogeneity in treatment effects by employing different estimation models. Recent research shows that the classical interleaved difference-in-differences (DID) model will produce estimation bias when faced with heterogeneity in treatment effects (Baker et al., 2022). The new DID method, proposed by Sun and Abraham (denoted as SADID), effectively resolves the aforementioned issue (Sun & Abraham, 2021). To mitigate this effect, we conduct the estimation using SADID. The estimation results are presented in Appendix E. These results indicate that policy effects have not undergone substantial changes, thereby validating the previous assumptions.

Analysis of policy synergistic effects and mechanisms

Analysis of conditions for synergistic effect

Impact assessment of goal alignment

Based on the previous section, it can be seen that there are three new types of performance assessment in CPEST. Among them, the green development priority is most consistent with the goals of climate policy. In order to analyse the mixed effects of three different CPEST and climate policies, we develop the following model:

In Eq. (4), \(T{{\rm{ype}}}_{{\rm{it}}}^{{\rm{m}}}\) denotes different CPEST types. \(m\) takes values of 1 or 2, indicating that the type of CPEST is green development priority or other priority, respectively. The other parameters are consistent with the baseline regression.

Insufficient samples in the treatment group may lead to estimation bias in the DID model (Conley & Taber, 2011). To avoid such issues, we examine the number of counties that implement both climate policy and CPEST (green development priority) before analysing them. It is found that ERPT satisfies the conditions in only 1% of the counties, while the remaining five climate policies have a proportion of 5% or more. Therefore, ERPT is not included in the analysis of goal alignment.

Figure 9 reports the results of the analysis after considering goal alignment. The results in Fig. 9a–e indicate that when combining climate policies with CPEST, the integration of green development priority CPEST and climate policies can generate a more pronounced carbon reduction effect. This indicates that, by removing the GDP indicator from the cadre performance evaluation system (CPES) and incorporating green development as a strong incentive indicator within it, a more significant mixing effect with climate policy can be attained. The findings in Fig. 9f reveal that mandatory policies produce more significant synergistic effects when there is a higher degree of goal alignment. Meanwhile, the LCCP, which previously lacked synergistic effects with CPEST, also demonstrates synergistic effects under the goal alignment scenario. This is likely because the LCCP is a hybrid climate policy that also employs certain administrative measures (Wen et al., 2022). Under goal alignment conditions, CPEST can strengthen the administrative measures within the LCCP, thereby enabling synergistic effects to occur. However, for purely market-based climate policies like the CETP, no synergistic effect emerges, even under the goal alignment conditions. This aligns with the theoretical analysis, indicating that CPEST can enhance climate policies relying on administrative means but has a comparatively limited influence on those based on market means. In conclusion, Hypothesis H2 is tested.

Impact assessment of time order

To assess the influence of time order, we design the following model:

In Eq. (5), \(TOrde{r}_{{\rm{it}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\) denotes the time order of policy implementation. \(T\) takes the value of 2 if the climate policy is implemented after CPEST, otherwise \(T\) takes the value of 1. The other parameters are consistent with the baseline regression.

CPEST was predominantly implemented between 2014 and 2016 (66% in 2014), while some climate policies, such as VMSR, commenced later. Analysing the policy-mixing effects of implementing these climate policies prior to CPEST, the relatively limited or even non-existent sample of CPEST meeting the criteria could result in biased estimates. Therefore, we select climate policies initiated before 2014 for analysis, and the policies meeting the criteria are CETP and LCCP. The results in Fig. 10 show that districts implementing the climate policy prior to CPEST achieve more significant carbon reduction effects. Nevertheless, the mixing effect of the two policies is marginally lower than the sum of the two policies and still does not produce a synergistic effect. The aforementioned results imply that the time order is beneficial for enhancing the combined effect of climate policy and CETP, but it is not yet sufficient to facilitate synergistic effect generation. Hypothesis H3 is tested.

Impact assessment of the official’s characteristics

To evaluate the impact of official characteristics, we formulate the following model:

In Eq. (6), \({{{OCharacteristics}}}_{{{it}}}\) represents a dummy variable for the official’s characteristics, including Age (with the dummy variable set to 1 if age ≤48), Gender (where the dummy variable is 1 if the official is female), Educational background (the dummy variable equals 1 if the official holds a master’s degree), and Hometown service (the dummy variable is 1 if the official serves in their hometown). The remaining variables are consistent with those in the baseline regression.

In China, the county party secretary acts as the de facto top-ranking local official, with this status becoming increasingly pronounced since 2013. Therefore, our study centres on the individual characteristics of county committee secretaries. The data are compiled from Baidu Encyclopaedia and the biographical information of officials on government websites. Some missing information on county clerks renders the sample size inconsistent with that in the baseline regression. Consequently, this section solely examines the impact of various officials’ characteristics on the policy mixing effect, without exploring whether they can produce policy synergistic effects.

For Chinese officials, a younger age means stronger political incentives (Wang et al., 2020). The results in Fig. 11(a) indicate that younger county commissioners tend to enhance the carbon reduction impact of policy mixes, which is observed in all policy combinations. This aligns with theoretical analyses suggesting that CPEST primarily resolves goal conflict and incentive incompatibility in climate governance via goal incentives. This further validates the role of incentives in the cadre performance evaluation system for strengthening climate policy.

Regarding gender, the results in Fig. 11b demonstrate that female county commissioners facilitate the enhancement of the carbon reduction effects of policy mixes, a pattern evident across all policy combinations. This aligns with previous theoretical analysis indicating that female officials’ pro-environmental traits are more beneficial for improving their environmental performance, particularly after the removal of GDP indicator assessments. This result also matches existing research findings (Wu, 2025).

Regarding educational background, the findings in Fig. 11c indicate that county commissioners holding a master’s degree are more likely to enhance the policy mixing effect, a pattern evident in most policy mixes. This may be due to the fact that education improves officials’ cognitive abilities, enabling them to better grasp the long-term benefits and emerging trends in the CPEST transition. As a result, they are more likely to factor climate policy goals into their decision-making.

Regarding hometown (place of birth), the results in Fig. 11d demonstrate that county commissioners serving in their hometowns are more likely to enhance the policy mixing effect, evident in 83% (5 out of 6) of all policy combinations. This stems from officials’ hometown preference, prompting them to be more inclined to formulate decisions and plans that benefit their hometowns’ long-term development, such as climate governance. In conclusion, Hypothesis H4 is tested.

Mechanisms identification

This section centres on three mandatory climate policies that can directly generate synergistic effects with CPEST, thus providing a better understanding of the role of CPEST. To this end, we devise the following triple difference model:

In Eq. (7), \({{{Mechanism}}}_{{{it}}}\) represents various mechanism variables, while the other variables remain consistent with those in the baseline regression. Figure 12 presents the mechanism analysis results of VMSR, and the results for the other two policies are essentially the same (refer to Appendix F for details).

Market mechanisms include industrial structure upgrading (ISU) and green technology innovation (GTI). Figure 12 indicates that the estimated coefficients for both single policies and policy mixes on carbon emissions are significantly negative in both ISU and GTI. This implies that the combination of climate policy and CPEST can reduce carbon emissions by facilitating industrial structure upgrading and green technology innovation, thereby validating the market mechanism proposed in Hypothesis H5. Furthermore, a comparison of the coefficients shows that policy mixing has no synergistic effect on ISU (0.007 + 0.006 > 0.011, absolute value), while it has a synergistic effect on GTI (0.15 + 0.12 < 0.28, absolute value). This is because the removal of the GDP assessment enables officials to allocate more financial resources (green technology subsidies) to green technology sectors instead of traditional technology sectors. This prevents the government from overemphasising economic growth at the expense of undermining the carbon reduction impacts of green technology innovations (Du et al., 2019). It also implies that green technology innovation (GTI) serves as one of the channels via which policy mixes can yield synergistic effects. Government mechanisms include environmental fiscal expenditure (EFE) and environmental penalties (EP). As illustrated in Fig. 12 (with details in Appendix F), neither climate policy alone nor CPEST alone can achieve a significant reduction in carbon emissions via EFE and EP. In contrast, a mix of climate policy and CPEST can significantly reduce carbon emissions by enhancing EFE and EP. The governmental mechanisms proposed in Hypothesis H5 are also validated. Moreover, a coefficient comparison indicates that policy mixes produce a synergistic effect on both EFE and EP. This is because independent mandatory climate policies, although they significantly boost environmental investment and environmental penalties in the short run, display characteristics of campaign-style governance and lack sustainability. For instance, certain studies have revealed that the impacts of some mandatory climate policies vanish merely six months later (Pan, 2025). Consequently, it is challenging to detect such carbon-reduction effects in long-term estimations. The removal of the GDP evaluation fundamentally eases officials’ concern that ‘stringent regulation results in a GDP slowdown’, thereby facilitating the standardisation and precision of environmental regulation. This finding also elucidates why mandatory climate policies can generate a synergistic effect with CPEST.

The above findings can be explained through the theoretical lens of an authoritarian-liberal hybrid in China’s environmental governance. Past literature has typically portrayed China as a classic example of an authoritarian environmentalist, relying on command-and-control measures for environmental governance (Gilley, 2012). However, recent evidence increasingly indicates that China’s environmental governance is not merely authoritarian but a hybrid of authoritarianism and liberalism. In other words, environmental governance outcomes hinge not only on national policies but also on local politics (Lo, 2015). The official political (career) incentive system is a vital part of local politics, directly shaping local policy implementation preferences (Li & Zhou, 2005; Zeng & Bao, 2024). The conflict in incentive mechanisms between climate governance and economic goals has diminished the central government’s control over local climate policy implementation (Lo, 2015). This scenario implies that climate policies, particularly those relying on command-and-control tools, will be unable to deliver sufficient expected outcomes. Following the implementation of CPEST, incentive conflicts were eliminated, thereby stimulating local governments’ political enthusiasm for implementing climate policies. In this context, the mix of CPEST and climate policies can amplify policy effects through carbon reduction pathways. This offers a convincing explanation for the results of the mechanism analysis.

Under the aforementioned theoretical scenario, the synergistic effects of mechanisms triggered by policy mixes can be further accounted for by attention theory and performance information features. Policy implementation is subject to the local officials’ decision-making process (Lipsky, 2010). Attention-based decision theory posits that organizational actions stem from the process of allocating attention to performance information (Jones & Baumgartner, 2005). Performance information characteristics directly influence the attention allocation process, with some key manifestations being that decision-makers are more likely to prioritize objective performance metrics and signals conveyed by internal performance information (van der Voet & Lerusse, 2024). When CPEST is mixed with climate policies, decision-makers need to make trade-offs and prioritize among multiple carbon reduction mechanisms. Compared with the complex and long-term industrial structure upgrading process, the other three mechanisms are relatively more measurable as objective performance indicators. Since the latter three can be objectively measured using the number of patents, fiscal expenditure amount, and the count of environmental penalties, these indicators are also commonly used in local government planning objectives and official performance evaluations. Therefore, local governments will allocate more resources to the three carbon reduction mechanisms (GTI, EFE, and EP) as a priority, thus enhancing synergistic effects. Meanwhile, EFE and EP serve as internal performance information, which is more apt to shape government decision-making priorities. This partly explains why synergistic effects are more pronounced within governmental mechanisms.

Conclusions and discussions

Conclusions

At a critical juncture when global climate governance still confronts a huge carbon reduction gap, it is urgent to better incentivise governments to put effort into climate policy. This study enriches the existing literature and informs policy-making by conducting a large-scale examination of the synergistic effect between China’s climate policy and cadre performance evaluation system. This study finds that climate policies can generate a synergistic effect with cadre performance evaluation systems (beyond GDP-orientation). This effect is predominantly observed in mandatory climate policies and is less evident in market-based climate policies. Second, goal alignment is crucial. When green development is set as a new priority incentive target in the cadre performance evaluation system, the policy synergistic effects can be substantially strengthened. Meanwhile, time order matters. Implementing climate policies prior to CPEST aids in enhancing the mixing effects of the two, yet it is still inadequate to generate synergistic effects. Additionally, official characteristics significantly influence policy mixing effects. Stronger mixing effects are more closely linked to officials who are younger, female, hold a master’s degree, and work in their hometowns. Finally, the mechanism analysis reveals that industrial structure upgrading, green technology innovation, environmental fiscal expenditure, and environmental penalties are the primary means by which policy combination contributes to carbon reduction. The latter three also serve as the main channels for generating policy synergistic effects.

Discussions

Our study explores the impact of combining climate policies and the cadre performance evaluation system on the effectiveness of carbon reduction. These findings contribute to the literature on climate governance in multi-tiered systems and offer new insights into policy mixing research. A detailed discussion is presented in this section.

The findings that mandatory climate policies and the cadre performance evaluation system have a significant synergistic effect on carbon emission reduction offer reliable theoretical support and practical solutions to enhance the effectiveness of environmental regulatory tools. There is no consensus on the carbon abatement effects of mandatory climate policies, as these effects vary depending on the national context (Danish et al., 2020). Several studies indicate that, under a multilevel governance system, many mandatory climate policies fail to effectively reduce carbon emissions in the long term (Chang et al., 2024; Pan, 2025). Insufficient incentives leading to a ‘campaign-style governance’ characteristic are deemed the primary cause of this issue. Therefore, effectively bridging policy goal conflicts between the central and local governments is crucial for sustaining the effects of campaign-style governance (Dong et al., 2024). We find that adjusting the cadre performance evaluation system, especially by completely removing the GDP indicator and adding the green development indicator, can precisely resolve this problem and facilitate the generation of long-lasting carbon reduction effects. It is noteworthy that the weak synergistic effects between market-based climate policies and the cadre performance evaluation system do not undermine their long-term value. As our study reveals, well-designed market-based policy instruments have enduring carbon reduction effects in themselves. This aligns with the policy effects observed in most studies (Du et al., 2022; Stechemesser et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2023). Therefore, the optimisation direction should be to reconfigure the time dimension of assessment indicators and design indicators that capture the long-term, indirect impacts of market policies (e.g., carbon market activity, green finance penetration, innovation spillovers), rather than curtailing the use of market instruments.

Our findings on goal alignment, time order, and officials’ characteristics also provide useful insights into existing research on climate policy mixing. Current research on climate policy mixes focuses on the synergistic effects among various climate policy types (Oberthür & von Homeyer, 2023; Stechemesser et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2023). However, cross-level and complementary policy measures are often overlooked (Bali et al., 2022). Under multi-level governance structures, friction or conflict in vertical policy instruments can hinder the low-carbon transition process (Zepa & Hoffmann, 2023). In many countries with strong government systems, this friction usually comes from political incentive trade-offs (Wu, 2023). We find that increasing goal alignment between governmental performance evaluation systems and climate policy can alleviate this discord and thus substantially augment the carbon reduction effects of climate policy. In terms of time order, some studies have found that high-level policies given priority guide lower levels of government, thereby contributing to policy coordination and enhancing the effectiveness of such policies (Huang, 2019). This is corroborated by our empirical results. Giving priority to the execution of climate policies can assist the as-yet-unreformed official performance evaluation system in devising more compatible indicators, thereby enhancing carbon reduction. However, interaction and feedback mechanisms between policies (Edmondson et al., 2019) alone are not yet sufficient to achieve synergistic effects. In terms of official characteristics, many studies find that younger, female, better-educated, and hometown-based officials are more likely to facilitate carbon reduction in climate policy implementation (Meng et al., 2019; Wu, 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). We further show that these official characteristics also influence policy mix effects, particularly when official performance evaluation systems intervene. This county-level evidence deepens the understanding of how political factors affect policy mix.

In terms of the mechanism of action, green technology innovation is widely recognised as an important channel for climate policy to promote carbon reduction (Chen et al., 2022). However, a study using data from 71 economies finds that green technologies may not necessarily result in substantial carbon reductions, especially when governments are more focussed on growing their economies (Du et al., 2019). Our findings indicate that mixing climate policy with an official performance evaluation system that goes beyond GDP-orientation can significantly enhance carbon reduction efficacy via green technology innovation, generating synergistic effects. In terms of the government’s environmental regulatory mechanisms (environmental fiscal expenditure and environmental penalties). Several studies find that increased environmental spending in climate policy programmes has not had a significant carbon reduction effect in the short term (Yuan & Pan, 2023). Environmental penalties produce limited effectiveness owing to ‘low costs of violations’. Even when the cost of violating the law is substantially raised, its effectiveness still gradually diminishes (Zhang & Liu, 2023). Our results are also consistent with the fact that climate policy or CPEST alone does not achieve significant carbon reduction through these mechanisms. However, it is worth noting that a mix of the two can achieve significant carbon reductions through these channels (with a synergistic effect). This aligns with the findings of an analysis on the BRICS countries, indicating that the effectiveness of environmental investments in carbon reduction also hinges on governance quality (Ul Hassan et al., 2024).

Policy implications

The key finding of this study is that effective carbon reduction demands not only well-formulated policies but also a robust policy implementation mechanism. Cadre performance evaluation systems can serve as a core element in enhancing this mechanism. To this end, we offer the following policy implications:

Firstly, the performance evaluation system for government officials should be reorganised to improve the efficacy of climate policies and manage the substantial pressure of carbon emission reduction. Although the ‘Beyond GDP’ initiative was launched long ago, economic growth still takes precedence in government performance indicators in many developing countries. For countries and regions with ambitious climate goals and significant carbon reduction shortfalls, clear, quantifiable, and mandatory climate targets (such as carbon emission cuts and renewable energy share) should be integrated into performance assessment frameworks at all government levels and in key sectors, shifting away from the traditional GDP-centric model. It is crucial to emphasise that reforming government performance systems should not merely involve incorporating climate targets. Instead, it must substantially elevate their priority and weight. This is especially relevant for countries or regions that are reforming their performance systems but have not yet made green objectives a central focus.

Secondly, optimise policy implementation procedures and official structures to harness the potential for synergistic effects. The findings based on the time order reveal that after the implementation of relevant climate policies (especially mandatory), new climate appraisal indicators should be introduced or given significantly greater weight in the cadre performance evaluation system at an appropriate time. This enables officials to be more adaptive and take action. This helps to reduce potential conflicts between the existing cadre performance evaluation system and the new climate policy. Our research also identifies traits of officials that contribute to improved climate governance. During the appointment of officials responsible for key climate and sustainable development issues, all things being equal, priority could be given to groups with the following traits: younger, female, more highly educated officials, and those serving in their hometowns.

Thirdly, the linkage between climate policy and cadre performance evaluation systems should be strengthened, and the transmission mechanism of the mixture of the two should be reinforced. Our study reveals that removing the GDP indicator in the cadre performance evaluation system significantly enhances the carbon reduction effects of environmental spending and environmental penalties. For countries and regions that rely on environmental regulation for carbon emission control, it may be advisable to enhance the sustained carbon mitigation effect of environmental regulatory policies by modifying the official performance evaluation system (increasing the proportion of low-carbon targets and reducing the weight of GDP indicators). At the same time, attention should also be paid to the scope of its role, as it has restricted synergistic effects related to market-based climate policies.

Finally, we should implement a tiered (at different government levels) and categorized (according to policy types) carbon reduction pathway. Central or provincial governments ought to focus on the integrated application of climate policies and performance evaluation instruments. Higher-level governments can establish climate policy targets as core performance indicators for lower-level governments. At the same time, clarify the policy positioning, especially for mandatory policies, and leverage the policy impact through a corresponding evaluation system. County-level governments should focus on the “last mile” of policy implementation to achieve targeted incentives. County-level governments should translate higher-level policy requirements into quantifiable performance targets. These targets should guide resource allocation toward four key channels: industrial structure upgrading, green technology innovation, environmental fiscal expenditures, and environmental penalties. For mandatory climate policies, a management plan should be established that combines target breakdown with performance-based rewards and penalties. Prior to policy implementation, emission reduction targets should be quantified and allocated, clearly defining the responsibilities of officials at all levels. Following the implementation of the policy, regions exceeding their emission reduction targets will receive incentives such as additional assessment points and special bonuses. Regions failing to meet targets will face punitive measures, including formal interviews and accountability, reinforcing the rigid constraints of policy and evaluation. For market-based climate policies, synergies should be enhanced by combining performance evaluation with market empowerment. On one hand, local governments can factor the innovative results of market-driven policies (e.g., carbon market trading volumes) into cadre evaluation “innovation bonus points”, spurring them to implement market-based climate policies. On the other hand, the government should strengthen publicity and training to enhance officials’ financial literacy and policy awareness, thereby breaking the mindset that prioritizes administrative directives over market-based approaches.

Limitations

Despite our substantial efforts, this endeavour still has certain limitations. First, we employ high-generality criteria to classify climate policies. However, this approach may overlook some promising ones, such as those associated with the digital and intelligent transformation of industries. Future research could categorise climate policies in greater detail to encompass more policy types. Specifically, it could focus on analysing the synergistic effects of the cadre performance evaluation system and industrial digital transformation policies. Second, the mechanism through which time order enhances policy mixing effects requires further exploration. Due to limited research data, we have been unable to delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms by which time order promotes policy combination. Future research can incorporate more detailed information from policy texts for expansion. Third, due to space constraints and limited research data, we have not explored the potential impact of public participation. Future research could further examine its role in policy mixing. Fourth, given the measurement errors in EDGAR’s county-level emission data, we mainly regard it as high-quality, indicative data. Future research may consider integrating EDGAR data with local datasets, including municipal energy statistics, environmental statistical bulletins, and high-resolution remote sensing data, to improve the accuracy of county-level carbon emissions estimates. This facilitates a more accurate assessment of the economic value of carbon reduction policies, providing an effective reference for weighing policy impacts.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Baker AC, Larcker DF, Wang CCY (2022) How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? J Financ Econ 144(2):370–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2022.01.004

Bali AS, Howlett M, Ramesh M (2022) Unpacking policy portfolios: Primary and secondary aspects of tool use in policy mixes. J Asian Public Policy 15(3):321–337

Bretschger L (2017) Climate policy and economic growth. Resour Energy Econ 49:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.03.002

Callaway B, Sant’Anna PHC (2021) Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. J Econ 225(2):200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001

Chang DH, Zhang ZY, Song HC, Wu J, Wang X, Dong ZF (2024) Icing on the cake” or “fuel delivered in the snow”? Evidence from China on ecological compensation for air pollution control. Environ Impact Assess Rev 109:107620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107620

Chen Y, Ye Q (2025) Is the digital government achieving its sustainability goals? The impact of urban mobile government apps on the urban-rural income gap. Cities 165:106073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2025.106073

Chen ZG, Zhang YQ, Wang HS, Ouyang X, Xie YX (2022) Can green credit policy promote low-carbon technology innovation? J Clean Prod 359:132061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132061

Conley TG, Taber CR (2011) Inference with “Difference In Differences” with a small number of policy changes. Rev Econ Stat 93(1):113–125. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00049

Danish, Ulucak R, Khan SUD, Baloch MA, Li N (2020) Mitigation pathways toward sustainable development: Is there any trade-off between environmental regulation and carbon emissions reduction? Sustain Dev 28(4):813–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2032

del Río P (2014) On evaluating success in complex policy mixes: the case of renewable energy support schemes. Policy Sci 47(3):267–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-013-9189-7

Do QA, Nguyen KT, Tran AN (2017) One Mandarin benefits the whole clan: hometown favoritism in an authoritarian regime. Am Econ J -Appl Econ 9(4):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20130472

Dong D, Ran R, Liu BS, Zhang JF, Song CC, Wang J (2024) Recentralization and the long-lasting effect of campaign-style enforcement: From the perspective of authority allocationPalabras Clave(sic)(sic)(sic). Rev Policy Res 41(1):239–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12548

Dong ZQ, He YD, Wang H, Wang LH (2020) Is there a ripple effect in environmental regulation in China? - Evidence from the local-neighborhood green technology innovation perspective. Ecol Indic 118:106773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106773

Du KR, Li PZ, Yan ZM (2019) Do green technology innovations contribute to carbon dioxide emission reduction? Empirical evidence from patent data. Technol Forecast Soc Change 146:297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.06.010

Du ZL, Xu CC, Lin BQ (2022) Does the Emission Trading Scheme achieve the dual dividend of reducing pollution and improving energy efficiency? Micro evidence from China. J Environ Manag 323:116202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116202

Edmondson DL, Kern F, Rogge KS (2019) The co-evolution of policy mixes and socio-technical systems: Towards a conceptual framework of policy mix feedback in sustainability transitions. Res Policy 48(10):103555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.010

Fransen T, Meckling J, Stünzi A, Schmidt TS, Egli F, Schmid N, Beaton C (2023) Taking stock of the implementation gap in climate policy. Nat Clim Change 13(8):752–755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01755-9

Gilley B (2012) Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environ Polit 21(2):287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.651904

Goedeking N (2025) Closing the implementation gap in urban climate policy: Mexico’s public transit buildup. Environ Polit https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2025.2500188

Grossman GM, Krueger AB (1995) Economic growth and the environment. Q J Econ 110(2):353–377

Guo SH, Song QJ, Qi Y (2021) Innovation or implementation? Local response to low-carbon policy experimentation in China. Rev Policy Res 38(5):555–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12436

Hjerpe M, Storbjörk S, Alberth J (2015) There is nothing political in it”: triggers of local political leaders’ engagement in climate adaptation. Local Environ 20(8):855–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.872092

Howlett M, Ramesh M, Perl A (1995) Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems. Oxford University Press

Huang P (2019) The verticality of policy mixes for sustainability transitions: A case study of solar water heating in China. Res Policy 48(10):103758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.02.009

Jing ZB, Liu ZD, Wang T, Zhang X (2024) The impact of environmental regulation on green TFP: A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s carbon emissions trading pilot policy. Energy 306:132357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.132357

Jones, BD, & Baumgartner, FR (2005). The politics of attention: How government prioritizes problems. University of Chicago Press

Li GY, Liu ZH, Zhao QY, Zhang GF (2024) Vertical intergovernmental environmental protection supervision authority changes and boundary pollution control: A case study of China. Econo Anal Policy 84:230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2024.08.014

Li H, Zhou L-A (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89(9-10):1743–1762

Lin BQ, Jia ZJ (2019) What will China’s carbon emission trading market affect with only electricity sector involvement? A CGE based study. Energy Econ 78:301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.11.030

Lin BQ, Xie JW (2023) Superior administration’s environmental inspections and local polluters’ rent seeking: A perspective of multilevel principal-agent relationships. Econ Anal Policy 80:805–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2023.09.023

Lin BQ, Xu CC (2022) Does environmental decentralization aggravate pollution emissions? Microscopic evidence from Chinese industrial enterprises. Sci Total Environ 829:154640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154640. Article

Lin Y, Qin Y, Wu J, Xu M (2021) Impact of high-speed rail on road traffic and greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Clim Change 11(11):952–957

Lipsky M (2010) Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation

Liu Z, Wang H, Zhou Y (2024) Assessment of emission reduction effects in China’s economic transformation and sustainable development strategy. Ecol Indic 167:112522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112522

Lo K (2015) How authoritarian is the environmental governance of China? Environ Sci Policy 54:152–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.001

Lyu J, Liu TL, Cai BF, Qi Y, Zhang XL (2023) Heterogeneous effects of China’s low-carbon city pilots policy. J Environ Manag 344:118329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118329

Marks D (2010) China’s Climate Change Policy Process: improved but still weak and fragmented. J Contemp China 19(67):971–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2010.508596

Meng H, Huang XJ, Yang H, Chen ZG, Yang J, Zhou Y, Li JB (2019) The influence of local officials’ promotion incentives on carbon emission in Yangtze River Delta, China. J Clean Prod 213:1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.036

Milhorance C, Howland F, Sabourin E, Le Coq JF (2022) Tackling the implementation gap of climate adaptation strategies: understanding policy translation in Brazil and Colombia. Clim Policy 22(9-10):1113–1129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2085650

Mora C, Spirandelli D, Franklin EC, Lynham J, Kantar MB, Miles W, Smith CZ, Freel K, Moy J, Louis LV, Barba EW, Bettinger K, Frazier AG, Colburn JF, Hanasaki N, Hawkins E, Hirabayashi Y, Knorr W, Little CM, Emanuel K, Sheffield J, Patz JA, Hunter CL (2018) Broad threat to humanity from cumulative climate hazards intensified by greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Clim Change 8(12):1062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0315-6

Nachtigall D, Lutz L, Rodríguez MC, Haščič I, Pizarro R (2022) The climate actions and policies measurement framework: A structured and harmonised climate policy database to monitor countries’ mitigation action. OECD Environment Working Papers. https://doi.org/10.1787/2caa60ce-en

North, DC (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press

Oberthür S, von Homeyer I (2023) From emissions trading to the European Green Deal: the evolution of the climate policy mix and climate policy integration in the EU. J Eur Public Policy 30(3):445–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2120528

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press

Ostrom E (2011) Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Stud J 39(1):7–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00394.x

Pan ST (2025) Dynamic responses of carbon emissions to central environmental protection inspection in China. Empir Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-025-02745-w

Pan YL, Dong F (2022) Design of energy use rights trading policy from the perspective of energy vulnerability. Energy Policy 160:112668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112668

Patterson JJ (2023) Backlash to Climate Policy. Glob Environ Polit 23(1):68–90. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00684

Rayner J, Howlett M, Wellsteacr A (2017) Policy Mixes and their Alignment over Time: Patching and stretching in the oil sands reclamation regime in Alberta, Canada. Environ Policy Gov 27(5):472–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1773

Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM (2018) How much does education improve intelligence? A meta-analysis. Psychol Sci 29(8):1358–1369

Rogge KS, Reichardt K (2016) Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: An extended concept and framework for analysis. Res Policy 45(8):132–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.04.004

Stechemesser A, Koch N, Mark E, Dilger E, Klösel P, Menicacci L, Nachtigall D, Pretis F, Ritter N, Schwarz M, Vossen H, Wenzel A (2024) Climate policies that achieved major emission reductions: Global evidence from two decades. Science 385(6711):884–892. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adl6547

Struthers CL (2020) The political in the technical: understanding the influence of national political institutions on climate adaptation. Clim Dev 12(8):756–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1689905

Sun LY, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J Econ 225(2):175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006

Tan YT, Mao XQ (2021) Assessment of the policy effectiveness of Central Inspections of Environmental Protection on improving air quality in China. J Clean Prod 288:125100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125100

Ul Hassan S, Basumatary J, Goyari P (2024) Impact of governance and effectiveness of expenditure on CO2 emission (air pollution): lessons from four BRIC countries. Manag Environ Qual 35(8):1721–1743. https://doi.org/10.1108/meq-12-2023-0424

van der Voet J, Lerusse A (2024) Performance information and issue prioritization by political and managerial decision-makers: A discrete choice experiment. J Public Adm Res Theory 34(4):582–597. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muae011

Wang YF, Song QJ, He JJ, Qi Y (2015) Developing low-carbon cities through pilots. Clim Policy 15:S81–S103. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1050347

Wang Z, Zhang QH, Zhou LA (2020) Career incentives of city leaders and urban spatial expansion in China. Rev Econ Stat 102(5):897–911. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00862

Wen SY, Jia ZJ, Chen XQ (2022) Can low-carbon city pilot policies significantly improve carbon emission efficiency? Empirical evidence from China. J Clean Prod 346:131131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131131

Wu JX (2025) Cities that breathe: Quantifying carbon emission reductions through forest city designation. Policy Econ 178:103541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2025.103541

Wu JX, Nie X, Wang H (2023) Are policy mixes in energy regulation effective in curbing carbon emissions? Insights from China’s energy regulation policies. J Policy Anal Manage. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22535

Wu N, Liu Z (2021) Higher education development, technological innovation and industrial structure upgrade. Technol Forecast Soc Change 162:120400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120400

Wu S (2023) A systematic review of climate policies in China: Evolution, effectiveness, and challenges. Environ Impact Assess Rev 99:107030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.107030

Xia X, Ren P, Wang X et al. (2024) The carbon budget of China: 1980–2021. Sci Bull 69(1):114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.11.016

Yuan S, Pan XF (2023) The spatiotemporal effects of green fiscal expenditure on low-carbon transition: empirical evidence from China’s low-carbon pilot cities. Ann Reg Sci 70(2):507–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01159-1

Zelezny LC, Chua PP, Aldrich C (2000) New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J Soc issues 56(3):443–457

Zeng JJ, Bao R (2024) Moving beyond gross domestic product: The impacts of gross domestic product-centric cadre performance targets shift on environmental protection. Public Admin Dev. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.2055

Zeng SB, Jin G, Tan KY, Liu X (2023) Can low-carbon city construction reduce carbon intensity? Empirical evidence from the low-carbon city pilot policy in China. J Environ Manag 332:117363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117363

Zepa I, Hoffmann VH (2023) Policy mixes across vertical levels of governance in the EU: The case of the sustainable energy transition in Latvia. Environ Innov Soc Transit 47:100699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100699

Zhang H, Lai J, Kang CY (2025) Does leading officials’ accountability audit of natural resources mitigate carbon emissions? Evidence from China. Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2025.2484025

Zhang K, Liu YT (2023) A review of the system of “daily continuous penalty” in China’s environmental protection practice-From the perspective of law and economics. Environ Impact Assess Rev 98:106976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106976

Zou C, Huang YC, Wu SS, Hu SL (2022) Does “low-carbon city” accelerate urban innovation? Evidence from China. Sustain Cities Soc 83:103954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.103954

Acknowledgements