Abstract

While the rapid economic growth promotes industrialization and urbanization, problems such as resource depletion, environmental pollution and ecological damage are inevitable. How to achieve ecological environment improvement through digital inclusive finance while promoting inclusive economic growth has become a new issue for all developing countries. Based on panel data of 733 counties of the Yellow River Basin from 2014 to 2022, this paper empirically analyzes the impact and mechanism of digital financial inclusion on the ecological environment through the fixed-effects, mediation, moderation, and quantile model. The main conclusions of this paper are as follows: (1) Digital financial inclusion increases the ecological environment index by 3.89%. Digital financial inclusion significantly improves the local ecological environment. (2) Digital financial inclusion improves the ecological environment in the Yellow River Basin by promoting technological innovation and rationalization industry structure. This improvement is negatively moderated by the social credit level. (3) In social-economic less developed areas, digital inclusive finance can better promote the ecological environment. Only digitization level of digital financial inclusion can promote the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin. Across the quantile of ecological environment from low to high, the impact of digital financial inclusion on the ecological environment transitions from negative to positive, with its influence progressively increasing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While the rapid economic growth promotes industrialization and urbanization, problems such as resource depletion, environmental pollution and ecological damage are inevitable. The Yellow River basin supports 12% of China’s population and 14% of GDP with 2% of China’s water resources, but agricultural water consumption accounts for 72%. Extensive irrigation has led to groundwater overexploitation in Ningxia, Inner Mongolia and other provinces of China, leading to land desertification. Shanxi, Shaanxi and other places rely on coal resources to develop heavy chemical industry, and the layout of enterprises along the river has led to long-term poor water quality and excessive ammonia nitrogen concentration in Fenhe River, Weihe River and other tributaries. The Outline of the Plan for Ecological Protection and High-quality Development in the Yellow River Basin issued by China’s State Council calls for a “healthy and stable ecosystem” by 2035. As a vital form of financial innovation, digital financial inclusion is increasingly becoming a significant force in promoting inclusive economic and social development due to its convenience, accessibility, and low cost (Chen et al. 2024). With the rapid advancement of digital technology, digital financial inclusion has increasingly demonstrated its potential to promote economic and green development (Ali et al. 2023; Işık et al. 2025; Işık et al. 2024).

Digital financial inclusion refers to the provision of extensive and affordable financial services through digital technology, covering groups such as small and micro enterprises, low-income groups, rural residents that are difficult to reach by the traditional financial system (Hao et al. 2024). Digital inclusive finance has effectively alleviated the major obstacles posed by the lack of funds to technological innovation and its dissemination, especially in the field of green technology. How to achieve ecological environment improvement through digital inclusive finance while promoting inclusive economic growth has become a new issue for all developing countries. The ecosystem of the Yellow River Basin in China is diverse, sensitive and vulnerable, and is facing severe challenges with the development of urbanization (Han et al. 2020). The problems it faces are also common ones encountered in the ecological environment and economic development of various developing countries. Therefore, it is necessary to take it as a typical case to analyze whether digital inclusive finance can improve the ecological environment. As a confluence of urban and rural economies, county economies not only act as natural carriers for integrating urban and rural elements (Chen et al. 2024), which is the primary target group for digital financial inclusion. Based on the county-level data of the Yellow River Basin in China, this paper tries to clarify how digital inclusive finance affects the ecological environment.

Many scholars have conducted research on digital inclusive finance and green development as well as environmental friendliness. He (2022) thinks digital financial inclusion has a consumption smoothing mechanism, which effectively alleviates the negative impact of climate change on the livelihoods of rural residents. Based on the data of 277 cities in China from 2011 to 2017, Lee (2022) finds that the marginal effect of digital inclusive finance on carbon intensity presents a “U-shaped” nonlinear dynamic relationship. Su (2021) finds that digital financial inclusion restrains local ecological efficiency but promotes overall ecological efficiency. Guo (2023) found that digital financial inclusion reduces carbon emissions and improves green total factor productivity. Lee and Wang (2022) finds that digital inclusive finance can directly reduce carbon intensity, and through optimizing the industrial structure and promoting green technology it can also affect carbon intensity. Based on the context of emerging seven economies, Çatik (2024) finds that digital finance inclusion contributes to the environmental deterioration. Chen (2024) finds that digital inclusive finance significantly spurs green innovation within enterprises by easing financing constraints and reducing transaction costs, and pertaining to the enhancement of corporate social responsibility. Notably, recent studies focusing on Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries have deepened the understanding of threshold and nonlinear characteristics in the finance-environment nexus. Işık et al. (2024) applied panel quantile regression to 27 OECD countries and found that the environmental impact of digitalization shifts from weak to strong as ecological quality improves. Similarly, Çatik et al. (2024) used a dynamic panel threshold model to test the Environmental Kuznets Curve in OECD countries’ transport sector, emphasizing that the effect of financial development on emissions depends on institutional thresholds.

Most relevant studies have reached a consistent conclusion at the national level or at the provincial and municipal levels in China that digital inclusive finance is conducive to environmentally friendly green development. However, there are also scholars who hold different viewpoints, such as Cheng (2024) believes China is still in early stage of digital financial inclusion and it delivers polarization effects’ on ecological environment. Similarly, Li (2025) found that digital inclusive finance would encourage the consumption of non-renewable energy, thereby increasing household carbon dioxide emissions from a more microscopic perspective of household. The nuanced county-level perspective is frequently overlooked whose data not only helps address the heterogeneity that is difficult to observe between provinces and the urban-rural divide but also expands the sample size, ensuring the robustness and credibility of research results. Furthermore, there are significant differences in environmental measurement indicators. Some scholars use single indicators, such as energy consumption (Hao et al. 2024),carbon emissions (Mukalayi and Inglesi-Lotz 2023) and PM2.5 (Yang et al. 2022), while few others use comprehensive indicators, such as principal ecological (Feng et al. 2022) and the investment efficiency of renewable energy firms (Wei et al. 2024).

Existing literature on environmental assessment often relies on indicators that measure isolated dimensions or adopt simplified composite measures, rather than embedding ecological complexity into an integrated analytical framework. The influence of digital inclusive finance on the ecological environment is inherently multidimensional, reflecting the fact that the ecosystem itself constitutes an interconnected system. For instance, the mechanisms through which digital finance affects carbon sequestration differ substantially from those influencing pollutant emissions, necessitating a unified approach that simultaneously incorporates factors such as carbon sinks and pollution levels. Such an integrated methodology can more accurately reveal the underlying linkages between digital financial inclusion and ecological outcomes, thereby offering scientifically robust and holistic insights for policy design and implementation. Moreover, prior studies focusing predominantly on OECD economies tend to overlook the distinct challenges faced by less developed regions. These studies seldom integrate both carbon sink capacity and pollution emissions into a consolidated ecological performance index, nor do they examine subnational heterogeneity, particularly at the county level. This critical research gap is what the present study seeks to address.

The marginal contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) Using specific and accurate multi-source county heterogeneity data, this paper makes an in-depth analysis of the impact of digital inclusive finance on the ecological environment by putting the two dimensions of “carbon sink” and “pollution” under a unified framework based on the entropy method, and expands the data dimensions and measurement methods used in the research on this issue. (2) From the perspective of mediation and moderation effects, this paper clarifies the action mechanism of digital inclusive finance on the ecological environment in China’s Yellow River Basin from both theoretical and empirical aspects, and provides reference for other similar developing countries to promote the ecological environment through digital inclusive finance. (3) From the dimensions of social economy and the development level, coverage breadth and depth of use of digital inclusive finance, this paper makes a detailed analysis of the heterogeneous impact of digital inclusive finance on the ecological environment, expands the research boundary of this field, and provides a more credible reference for targeted policy suggestions.

By using county-level data from the Yellow River Basin (a typical developing-country watershed) and constructing a comprehensive ecological index that combines carbon sequestration (e.g., vegetation carbon storage) and pollutant emissions (e.g., PM2.5, SO₂), we extend the finance-environment research framework from OECD countries to underdeveloped regions, while validating the cross-context relevance of nonlinear relationships between digital inclusive finance and ecological quality. This extension not only enriches the theoretical basis of digital finance for ecological governance but also provides empirical evidence for developing countries facing dual pressures of poverty alleviation and environmental protection.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 1 presents the introduction. Section 2 constructs the theoretical framework about how digital inclusive finance’s impact on the ecological environment. Section 3 presents the research methodology, including variable selection, data sources, and model specification. Section 4 conducts empirical data analysis, testing the role of digital inclusive finance in improving the ecological environment. Section 5 further discusses mediation and moderation effects and performs heterogeneity analysis. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the conclusions, proposes policy recommendations, and discusses this paper’s limitations and future research directions.

Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

With the help of innovative tools such as supply chain finance and green microfinance, digital inclusive finance has effectively lowered the financing threshold for environmentally friendly projects and provided key support to local small and medium-sized enterprises(SMSE) and farmers (Ge et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2021). Under the background of intensive traditional industries in the Yellow River Basin, digital inclusive finance accurately locates scattered and small-scale ecological governance needs, such as water-saving irrigation, straw recycling and other projects, through the deep integration of big data credit investigation. In view of the green transformation financing dilemma commonly faced by SMSE and farmers in the Yellow River Basin (Lu et al. 2022), that is, it is difficult to obtain bank loans due to the lack of traditional collateral and credit records, digital inclusive finance platforms transform fragmented ecological resources into tradable digital assets through mobile payment and smart contract technology. This measure not only attracts the inflow of cross-regional capital, but also optimizes the “spatial mismatch” and “maturity mismatch” of ecological assets in the Yellow River Basin, realizing the efficient allocation of capital factors.

At the same time, the development of digital inclusive finance provides consumers with more convenient and diversified payment methods and financial products. Through digital platforms such as Alipay, consumers can easily access incentive mechanisms for green consumption, such as the “Ant Forest” project, which converts low-carbon behaviors into public welfare experience of virtual tree planting, and the “Green Huabei Special Program”, which provides preferential consumption support for green goods (Chen et al. 2024). These innovative measures not only promote the market penetration of green and intelligent products, but also guide consumers to gradually form low-carbon and environmentally friendly consumption habits, promote the green consumption market from the demand side (Platteau et al. 2014; Qin et al. 2022), and form a synergistic effect with the ecological governance of the supply side of the Yellow River Basin.

Hypothesis 1: Digital financial inclusion improves ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin.

In the process of green transformation in the Yellow River Basin, digital inclusive finance has become the core force to promote green technology innovation by reconstructing the allocation mode of innovation factors (Yang et al. 2024). In the field of financing, digital inclusive finance can penetrate into areas that traditional credit assessment finds difficult to reach, incorporating enterprises’ carbon emission data and environmental protection patents into the credit assessment system, thereby significantly lowering the financing threshold for green technology research and development (Li et al. 2022; Zou and Deng 2022). In terms of risk diversification, the “long tail effect” of digital inclusive finance has effectively stimulated the enthusiasm of social capital to participate in green innovation. New energy enterprises can raise funds for distributed photovoltaic research and development through the crowdfunding platform of digital inclusive finance, and automatically transfer project proceeds to ecological restoration funds with the help of smart contracts (Işık et al. 2024). This positive feedback mechanism of “technology research and development - environmental benefits” has effectively improved the speed of technology diffusion in the fields of smart water-saving irrigation and solid waste resource utilization in the Yellow River Basin compared with the traditional mode, providing a transition path for replacing the highly polluting production mode with clean technology.

Hypothesis 2a: Digital financial inclusion improves the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin by promoting technological innovation.

By virtue of its advantages in digital technology and inclusive characteristics, digital inclusive finance can break through the spatial constraints and information barriers of traditional financial services (Yuan et al. 2023), and effectively alleviate the financing constraints of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises and green technology projects in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River Basin. This improvement in the availability of capital can drive the flow of production factors to modern service industries with low energy consumption and high added value and strategic emerging industries, accelerate the elimination of backward production capacity and optimize the efficiency of resource allocation (Işık et al. 2024; Wang et al. 2022). Secondly, through big data analysis and precise risk control model, digital financial platform can guide credit resources to lean towards environment-friendly industries such as circular economy and clean energy, and promote enterprises in the region to realize green upgrading of production process through technological innovation. Moreover, digital inclusive finance helps to build a cross-regional ecological compensation mechanism and promote the formation of a resource recycling network between upstream and downstream industries in the Yellow River Basin, thus reducing the pollution emission intensity of the whole industrial chain (Cao et al. 2021; Işık et al. 2024; Ren et al. 2023).

Hypothesis 2b: Digital inclusive finance promotes the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin by rationalization of industrial structure.

The actual utilization rate of foreign capital plays a positive moderating role in the relationship between digital inclusive finance and ecological environment improvement in the Yellow River Basin, and its mechanism is reflected in the dual path of “technology spillover and standard traction.” First of all, foreign enterprises are usually embedded in the international green supply chain system, and their advanced environmental governance technologies and management norms spread to local enterprises through the industrial linkage effect (Wang et al. 2022). Secondly, foreign capital inflows are often accompanied by the endogeneity of ESG investment standards, and the hard requirements of international capital on environmental performance are coordinated with the green credit evaluation system of digital inclusive finance, which encourages financial institutions to give priority to supporting renewable energy, ecological restoration and other projects in cross-border capital flows (Zhou et al. 2023). Especially in the export-oriented economically active regions in the lower reaches of the Yellow River Basin, the combination of foreign-led industrial clusters and digital financial tools can accelerate the transmission process of “green technology introduction-localized innovation-environmental performance improvement,” thus amplifying the ecological and environmental improvement effect of digital inclusive finance.

Hypothesis 3a: The actual utilization rate of foreign capital positively moderates the improvement of the ecological environment by digital financial inclusion in the Yellow River Basin.

In regions with high credit level, although a perfect credit investigation system reduces financial risks, it may weaken the initiative of market players in environmental governance. In order to maintain credit ratings, enterprises are more inclined to choose traditional environmental protection measures with low risks and clear compliance, rather than green technology innovation that requires long-term investment and high uncertainty, resulting in green projects supported by digital inclusive finance becoming formal transformation (Chen et al. 2022). At the same time, excessive transparency of credit information may lead to “data paralysis,” that is, financial institutions rely too much on historical credit data to screen customers and ignore the potential dynamic improvement ability of environmental performance (Liu et al. 2023). In the regions where the credit system needs to be improved in the Yellow River Basin, the low social credit level instead forced the digital financial platform to innovate the risk control model, and more accurately identify and motivate the substantial environmental protection behaviors by dynamically tracking the indicators such as corporate pollution emissions and resource consumption (Zhou et al. 2023), thus partially offsetting the inhibiting effect of the rigid credit system on the green transformation.

Hypothesis 3b: The social credit level negatively moderates the improvement of the ecological environment by digital financial inclusion in the Yellow River Basin.

Methodology

Variables selection

Explained variable

The explained variable is the ecological environment level, measured by the comprehensive ecological environment index (EEI) calculated based on the entropy method. For EEI, the positive indicators(carbon sink) include the amount of afforestation (unit: hectare) and the amount of carbon sequestration by vegetation (unit: ton), which are used to evaluate the carbon sink capacity and environmental sustainability of the ecosystem. Negative indicators(pollution) include carbon emissions and PM2.5 emissions, sulfur dioxide emissions in industrial waste gas (unit: ton), soot emissions in waste gas (unit: ton), and nitrogen oxide emissions in waste gas (unit: ton) to comprehensively measure the ecological environment level.

The comprehensive ecological environment index (EEI) can systematically describe the two-way mechanism of “carbon sink” and “pollution” for ecological environment, and using entropy method to dynamically weight, and overcome the problem of one-sided single index. On the one hand, the entropy method automatically assigns weights according to the index dispersion (for example, the weight increases when the regional difference of PM2.5 expands), accurately capturing the stage focus of ecological restoration and pollution control in different sections of the Yellow River Basin. On the other hand, multi-indicator collaborative quantification avoids the disadvantage that single data is vulnerable to interference by extreme values. At the same time, through the symmetric processing of positive and negative indicators, the nonlinear superposition effect of digital inclusive finance and other technical means on ecological gain and pollution reduction is revealed, which provides a multi-dimensional robust benchmark for the evaluation of policy effects.

Core explanatory variable

The core of digital inclusive finance lies in using digital technology to lower the threshold and cost of financial services and expand the coverage of financial services, especially for groups with insufficient financial services coverage. The digital financial inclusion (DFI) index co-published by Alibaba and the Digital Finance Research Center of Peking University (Zhang et al. 2023) is widely used in digital financial inclusion related research. This paper selects its first-level indicators, index aggregate (DFIia) to effectively ensure the comprehensiveness, timeliness, and reliability of DFI (Liu et al. 2023). There are three second-level indicators of the DFI index, which are coverage breadth (DFIcb), usage depth (DFIud), and digitization level (DFIdl). To unify the dimensions, the above core explanatory Variables are divided by 100.

Control variable

Regarding existing literature, other socio-economic control Variables selected in this paper include: (1) Industrialization Level (IL). The proportion of traditional industrial sectors shows a significant positive correlation with pollutant emission intensity (Liu et al. 2023). (2) Degree of financial strain (DFS). Government financial pressure will weaken investment in environmental governance through crowding-out effect (Chen et al. 2024). (3) Fiscal dependency (FD). If the fiscal dependence is high, the government’s fiscal revenue is relatively abundant, and more resources may be invested in environmental protection and governance projects (Su et al. 2025). (4) Degree of financial deepening (DFD). A well-developed financial system can provide more financing channels to support the development of environmental protection projects and green technologies (Gong et al. 2025). (5) Gross regional product (GDP). Economic growth is usually accompanied by an increase in resource consumption, but may also lead to an increase in investment in environmental protection (Lei and He 2025).

Sample selection and data sources

The amount of afforestation is from the Statistical Yearbook of Forestry and Grassland of China. County-level carbon emission and vegetation carbon sequestration data from 2014 to 2017 are obtained from Chen (2020), Carbon emission data from 2018 to 2022 are completed using the interpolation method based on continuous data from 1999 to 2017 (Chen et al. 2020). PM2.5 data from Dalhousie University’s Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group. The Sulfur dioxide emissions in industrial waste gas, soot emissions in waste gas, nitrogen oxide emissions in waste gas to comprehensively and other socio-economic indicators comes from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). For the accuracy of the datasets, this paper undertakes meticulous cross-referencing and supplementing the databases mentioned above. The list of national-level poor counties is from the “List of 832 Poor Counties in China” issued by the National Rural Revitalization Administration. The list of contiguous poverty-stricken areas is from the Explanatory Note of the Poverty Alleviation Office of The State Council on Announcing the List of Contiguous Poverty-stricken Areas by County throughout the Country.

The steps for constructing and cleaning unbalanced panel data in this paper are as follows: (1) The Yellow River basin originates from Bayankara Mountain on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and flows eastward into the Bohai Sea, traversing nine provinces of China, encompassing 115 prefecture-level cities and 963 counties (Zhang et al. 2023). The data samples of this paper are firstly restricted to the counties within the Yellow River basin. (2) Missing values in the panel data are supplemented using the interpolation method, and newly established or abolished county-level administrative units, as well as counties with significant data gaps, are excluded. (3) Considering that the county-level digital inclusive financial index has only been released since 2014, the panel data starts from 2014. (4) There is an obvious lag in the update of county data in China, usually more than two years behind the current year, and the time coverage period of some key data is short. (5) Samples with missing core explanatory variables, explained variables and key control variables are eliminated. (6) The panel data of 745 counties in the Yellow River Basin from 2014 to 2022 is constructed.

Although the assumption of linear trend may lead to systematic bias in the interpolation results, the evolution of ecological environment usually presents a gradual feature. In view of the change inertia and continuity of ecological parameters (such as vegetation coverage and pollutant concentration usually do not have step mutation), under the realistic conditions of limited data availability, interpolation method is still a relatively reasonable scheme to fill data gaps. The descriptive statistics of each variable are shown in Table 1.

Model specification

To evaluate the ecological environment of the counties in the Yellow River basin, the entropy method is employed to objectively assign weights based on the data dispersion. The specific measurement steps are as follows:

Standardization of positive indicators(carbon sink):

Standardization of negative indicators(pollution):

Where Xi,j is the original data of variable j in county i, Yi,j is the data after normalization; min and max represent the maximum and minimum of values, respectively. The above values are normalized.

The second step: comprehensive calculation of the ecological environment.

Where, Pi,j is the proportion of county i in the index of variable j; ej is the entropy of the variable j; gj is the difference coefficient of the variable j; wj is the weight of the variable j, and Score is the comprehensive ecological environment index.

Since the panel data used in this paper has the characteristics of large cross-sectional dimension and relatively short time dimension, after comprehensive consideration of its characteristics such as serial correlation, heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence (see the analysis of Supplementary Table A~F in the Appendix), this paper finally decides to adopt time fixed effect and individual fixed effect with standard errors clustered to the county dimension as the benchmark regression model.

In this model, the setting of fixed effects can effectively absorb unobservable heterogeneous factors among different counties, such as differences in geographical endowments and historical policies. This treatment makes between-group R² play a leading role in the improvement of the overall explanatory power of the model. The benchmark regression model is set as follows:

Where EEIit is the ecological environment level of county i in t year; DFIit is the development level of digital inclusive finance in t year of county i; πi is the individual fixed effect; λt is the time fixed effect; Controlit is the control Variables; ɛit is the error term; α is the constant term; EEIit-1 is the ecological environment level of county i in t-1 year. In addition to introducing time-fixed and individual-fixed effects to eliminate the influence of time-varying and individual-varying factors, this paper clusters the standard error to the county level for alleviating the inter-group correlation and avoiding the problem of excessive significance caused by underestimating the standard error.

Empirical analysis

Baseline regression

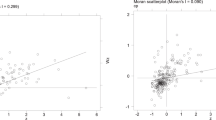

The distribution of the comprehensive ecological environment index data in the Yellow River Basin is shown in Fig. 1. The comprehensive ecological environment index at the county level generally exhibits a gradual upward trend and tends to converge over the years.

Overall, most of the observation points are relatively concentrated at the lower EEI, while in areas with a higher level of digital inclusive finance, the observation points show a larger-scale aggregation state as shown in Fig. 2. In addition, there are also a considerable number of observation points distributed in areas where both EEI and digital inclusive finance are at a relatively high level. However, merely through the visual display of the sunflower chart, it is not sufficient to directly determine the correlation between EEI and digital inclusive finance. Based on this, this paper further conducts an in-depth empirical analysis based on the benchmark regression model to explore a more precise and detailed relationship between the two.

The time-fixed, individual-fixed, and standard error clustering are introduced into the benchmark regression successively, whose regression results were shown in Table 2 (1)–(4). The influence coefficient of DFIia on EEI fluctuates between 1.06% and 3.89%.

The column (4) is taken as the benchmark regression results in this paper, the influence coefficient of DFIia on the EEI is 3.89%, hypothesis 1 of this paper is proved. DFI can improve the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin.

Robust test

Change the explanatory variables

Take the logarithm of DFIia (Ln_DFIia) and substitute it into the core explanatory variable for calculation, the regression result is shown in the column (1) of Table 3.

Change the sample

-

(1)

The sample was winsorized at 1% quantile, and the regression result is shown in column (2) of Table 3.

-

(2)

The samples were grouped by province and censored at 1% quantile, and the regression result is shown in column (3) of Table 3.

-

(3)

Considering urban areas may differ from non-urban counties in many aspects, such as economic development level, population size, industrial structure. The regression results of Excluding the urban areas is shown in column (4) of Table 3. The influence coefficient of DFIia on EEI is fluctuates between 1.89% and 4.36%.

Change the regression model

Considering that the panel data in this paper typically have a large cross-sectional dimension (N = 733) and a relatively short time dimension (T = 9), even if the time individual fixed effect model is adopted in the benchmark regression and the standard error is clustered to the county dimension, there may still be some problems such as heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence. In this regard, the regression model is replaced with a regression model that is more specific to heteroscedasticity and interface dependence to test the robustness of the regression results. The regression model is replaced as follows: (1) Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS); (2) Driscoll–Kraay standard error; (3) Bootstrap standard error (repeated sampling 500 times); (4) Heteroscedasticity robust standard error; (5) Difference Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), the regression results are shown in columns (1)–(5) of Table 4.

The correlation coefficients of the robustness test are consistent with those of the baseline regression in terms of numerical value and confidence, which proves the robustness of the benchmark regression.

Endogenous test

For baseline regression, clustering standard errors based on the fixed-effects model helps to mitigate endogeneity to a considerable degree. Given that the instrumental variable two-stage least squares method (IV-2SLS) can alleviate the endogenous problem caused by reverse causation, this paper selects Disthangzhou*Mean-DFIia and Average-DFIiacity as the instrumental variable.

Disthangzhou*Mean-DFIia is the intersection term of the spherical radius distance from Hangzhou and the average annual value of digital inclusive finance across the country (Li et al. 2022). Hangzhou is the birthplace of Alipay, one of the largest providers of digital inclusive finance in China. The diffusion of digital technology shows a “distance attenuation effect”, that is, the closer to Hangzhou, the higher the penetration rate of digital finance. Geographical distance is determined by natural endowment and historical administrative divisions, and has nothing to do with county-level economic policies, environmental governance, etc. Theoretically, it does not directly affect the ecological environment (Lu et al. 2021). Geographical distance is fixed and constant, while DIF changes dynamically over time. Therefore, the mean of the national DIF level is introduced to construct the transaction multiplication term to overcome the problem that if DIF spreads rapidly over time, the correlation of static distance may weaken. In addition, the exogeneity of geographic distance is transmitted through the interaction term, and the national mean is not affected by individual counties.

Average-DFIiacity is the average value of DFIia of other counties in the same city. Digital inclusive finance has the possibility of “siphon effect”, that is, developed counties may attract deposits and customer resources from surrounding areas, and there may be competition among counties under the condition of limited resources (Chen et al. 2024). Therefore, the development level of digital finance in other counties will have an impact on the development of digital finance in their own counties with the help of spatial spillover effect. At the same time, as a virtual economic activity, the direct environmental pollution caused by digital inclusive finance across counties can be almost ignored. In addition, the ecological environment status of other counties is not directly related to the relevant policies of digital inclusive finance in this county.

As shown in column (1)–(2) of Table 5. The Sanderson–Windmeijer multivariate F-test, the Cragg–Donald Wald F-test and the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM test all show that the instrumental variables are very strong and there is no weak instrumental variable problem. The Kleibergen–Paap rk LM test indicates that the model is sufficiently identified and the number of instrumental variables is sufficient. The Anderson–Rubin Wald test and Stock–Wright LM S test show that the endogenous variables are still jointly significant in the master equation even when the weak instrumental variable problem is considered. The Hansen J test shows that the instrumental variables are exogenous and there is no overidentification problem. Disthangzhou*MEAN-DFIia and Average-DFIiacity are significantly correlated with DFIia. The coefficients of DFIia for EEI is significantly positive and consistent with the benchmark regression.

Further discussion

Mechanism analysis

Mediation effect analysis

Regarding the baseline regression, the mediator effect model is constructed as follows:

Where Mit represents the mediation variable of t years in i county; JGCC is the industrial structure level coefficient, whose higher value means more reasonable and advanced the industrial structure of the region; GDPPrimary is the output value of the primary industry; GDPSecond is the output value of the secondary industry; GDPTeriary is the output value of the tertiary industry. LQ is the location quotient, whose higher value means the higher the level of specialization and industry agglomeration.

Use the number of valid New invention patents (Patents) and newly registered enterprises in the field of scientific research and technical services (New-tech) to measure level of technological innovation. In this paper, the JGCC and the LQ are used to measure the rationalization degree of industrial structure. Substituting Patents, New-tech, JGCC, and LQ into Mit to explore the mediator effect, whose regression results are shown in Table 6 (1)–(4). The influence coefficient of Patents, New-tech, JGCC, and LQ on EEI is 29.19%, 51.47%, 31.08%, and 14.55%, hypothesis 2a and 2b of this paper are proved. Digital financial inclusion improves the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin by promoting technological innovation and rationalization industry structure.

Moderation effect analysis

Based on Eq. (8), this paper introduces the interaction term between DFIia and macroeconomic factors (R×DFIia), the moderating effects model as shown in Eq. (12).

Where Rit is the regulating variable and ψ is its correlation coefficient. The actual utilization of foreign capital (AUFC) is used to measure the actual utilization of foreign capital, and the year-end loan balance of financial institutions (YLBFI) is used to measure the social credit level. The regression results are shown in Table 7 (1)–(2).

The influence coefficient of AUFC×DFIia on EEI is 1.52% but not significant. Although there are signs of the actual utilization of foreign capital positive moderates the promotion effect of DFI on ecological environment, the evidence is insufficient to confirm a significant correlation between the two. This may be because the sample size of AUFC is too small, resulting in potentially insufficient statistical power to detect a significant correlation. It may also be that the true correlation between AUFC and this promotion effect is weak and fails to reach statistical significance even in the right direction. This may require follow-up studies to collect more data and conduct more in-depth analysis.

The interaction term YLBFI×DFIia has a positive influence coefficient of 0.10% on EEI, which is significant at the 95% confidence level. This result supports Hypothesis 3b of this paper. The social credit level negatively moderates the improvement of DFI on the ecological environment. In the high-credit social environment, the focus of economic activities may deviate from ecological and environmental protection, which restricts the role of digital inclusive finance in supporting green projects. In addition, a high level of social credit may mean that the market is more mature, the marginal effect of digital inclusive finance is reduced.

Heterogeneity analysis

Socio-economic heterogeneity

To analyze the heterogeneous impact of DFI on the ecological environment under different social-economic foundations, this paper divides the samples into two sub-samples according to whether they are National-level Poor Counties and contiguous areas of extreme poverty. The regression results are shown in Table 8 (1)–(4). In national-level Poor Counties and contiguous areas of extreme poverty, the influence coefficient of DFIia on EEI is 6.01% and 5.33%, respectively. The influence coefficient of DFIia on EEI is 1.35% and 2.02% in other areas, and this influence is not significant. DFI can better promote the ecological environment in social-economic less developed areas. To ensure the robustness of the results, this paper divides the samples into two sub-samples based on whether belonging to poor areas (National-level Poor Counties or contiguous areas of extreme poverty) or not. As shown in columns (5)–(6), the influence coefficients of the regression results are similar to the previous findings.

Traditional financial services have been absent in poor areas for a long time. The introduction of digital inclusive finance can quickly fill the funding gap and directly improve the environment through targeted support for green agriculture, ecological restoration and other projects. Digital inclusive finance in poor areas is often bundled with poverty alleviation and ecological protection policies, with strong policy orientation and more focus on the environment. In addition, the poor areas in the Yellow River Basin have serious desertification and soil erosion, and the foundation of the state environment is weak. In economically active regions, financial institutions are more concerned about business sustainability and may prefer non-green high-return projects, such as real estate, to low-return environmental projects. The “inclusiveness” of digital inclusive finance in this scenario serves more for economic growth than environmental goals. In contrast, the level of original environmental governance in developed regions is high, and the marginal contribution of digital inclusive finance is small.

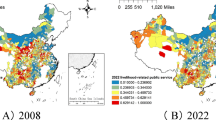

Analysis of sub-dimensions of digital financial inclusion

The overall growth of DFI in China has covered various development trends of its different sub-dimensions which are coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitalization level (Liu et al. 2023). The analysis of the social-economic effect of DFI should also focus on the different effects of sub-dimensions besides the index aggregate. (1) The extent of digital financial inclusion coverage breadth is primarily associated with account coverage, which expands the reach of financial services, especially to individuals and businesses in remote and non-core urban areas (Wang and Wang 2021). (2) The usage depth of DFI mainly reflects the digital financial business and provides fast loan approval and fund disbursement (Mu et al. 2023). (3) The digitization level of DFI primarily measures the extent and scope of digital technologies adopted in operations and services. The data distribution of coverage breadth, usage depth and digitization level is shown in Fig. 3, presenting obvious portability characteristics.

To explore the heterogeneity of DFI different sub-dimensions, DFIcb, DFIud, and DFIdl were substituted into explanatory Variables respectively, and the regression results are shown in Table 9 (1)~(3). The influence coefficient of DFIcb and DFIud for EEI is 1.37% and 1.22%, respectively, which is positive but not significant. The influence coefficient of DFIdl on EEI is 0.95%, and significant at 90% confidence level. Only the development of digitization level dimension of digital inclusive finance can improve the ecological environment.

Coverage breadth of DFI mainly refers to the reach of financial services. Although its expansion can improve financial inclusion, it may be accompanied by resource misallocation at the initial stage. In the absence of regulatory constraints, funds may flow to highly polluting industries, offsetting the environmental benefits of green projects. Usage depth of DFI reflects user activity, which may indirectly increase energy consumption by stimulating consumption and expanding production.

Digitization promotes the proportion of high-tech industries and reduces energy consumption per unit of GDP through industrial upgrading effect. Digital infrastructure can break down geographic constraints and facilitate cross-city sharing of environmental technologies. In addition, digital tools can also lower information barriers to green technology R&D and ease financing constraints. Therefore, digitization level of DFI has a more prominent performance in improving the ecological environment than the coverage breadth and usage depth.

Quantile regression

In regions with fragile ecological environments, ecosystems are already under significant stress, confronting complex issues such as severe pollution and ecological degradation. When digital inclusive finance first enters these areas, its characteristics in resource allocation and industrial guidance make it more likely to integrate with the existing economic models, which are typically centered around traditional industries. Given that the current industrial structure in these regions is dominated by high-pollution and high-energy-consuming industries, the support from digital inclusive finance to traditional sectors may, to some extent, exacerbate the destruction of the ecological environment (Zhang et al. 2024). Regions with good ecological environments, on the other hand, present different characteristics. These regions not only have a relatively healthy ecological environment foundation, but also have a relatively high awareness of ecological environment protection among the government and residents. Against this backdrop, digital inclusive finance can effectively guide funds into green industries. In addition, the industrial structure of these regions is more inclined towards eco-friendly industries, such as eco-tourism, green agriculture, and cultural and creative industries, etc. There exists a positive mutual promotion relationship between their development and the improvement of the ecological environment. Digital inclusive finance forms a virtuous interaction between the ecological environment and economic development by providing financial support for the expansion and upgrading of these industries.

This paper employs the “qrprocess” command introduced by Chernozhukov (2022) to obtain information on the conditional distribution and mitigate the influence of outliers on the estimated outcomes. To further analyze the varying impact of DFI on different quantiles of the ecological environment index, this paper established the following quantile regression model, where Q(EEIit|DFIit) is the quantile function, represents the regression result of a particular quantile of EEIit.

Table 10 sequentially displays the regression results of DFIia at quantiles 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9, whose influence coefficient is −0.92%, −0.45%, 0.11%, 1.32%, and 51.75%, respectively. When the EEI is at the low level (0.1 quantile), the impact of DFIia on the ecological environment is negative, the DFI will slightly worsen the ecological environment. With the improvement of EEI (from 0.1 to 0.5 quantile), this negative impact has gradually weakened. When the EEI is at a medium level (0.5 quantile), When the EEI is at the high level (0.7 quantile), the impact of DFI on the improvement of the ecological environment is relative limited, but it has turned from negative to positive. When the EEI is at the more higher level (0.9 quantile), the improvement on the ecological environment by DFI is prominent.

The impact of digital financial inclusion on the ecological environment shifts from negative to positive as we move from lower to higher quantiles, with the influence gradually increasing. In regions with poor ecological conditions (low quantiles), digital financial inclusion may drive more economic activities and resource exploitation, often at the expense of environmental protection, leading to further degradation. However, as the ecological environment improves, digital financial inclusion can become more aligned with sustainable development models, such as green finance and environmental technology, gradually producing positive effects.

Conclusion and policy implications

Prior research on digital financial inclusion and environmental sustainability has predominantly relied on macro-level analyses and single-dimensional indicators, overlooking county-level heterogeneity and ecological complexity. This study addresses these gaps by employing a county-level panel dataset, constructing a comprehensive ecological index integrating carbon sink and pollution metrics, and utilizing quantile regression to uncover threshold effects and differential impacts across regions. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of digital finance’s role in environmentally vulnerable areas. By constructing panel data covering 733 counties in the Yellow River Basin from 2014 to 2022 through multiple channels, this paper analyzes the impact and mechanism of digital financial inclusion on the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin through the fixed-effect model, mediator effect, moderator effect, and quantile model, and draws the following conclusions: (1) Digital financial inclusion increases the ecological environment index of the Yellow River Basin by 3.89%, significantly improving the local ecological environment. (2) Digital financial inclusion improves the ecological environment in the Yellow River Basin by promoting technological innovation and rationalization industry structure. This improvement is negatively moderated by the social credit level. (3) In social-economic less developed areas, digital inclusive finance can better promote the ecological environment. Only digitization level of digital financial inclusion can promote the ecological environment of the Yellow River Basin. Across the quantile of ecological environment from low to high, the impact of digital financial inclusion on the ecological environment transitions from negative to positive, with its influence progressively increasing.

This paper puts forward the following policy recommendations: (1) Improve the precision of digital governance and reduce reliance on traditional credit systems. Given the observed negative moderating effect of social credit levels, it is essential to diminish dependence on conventional credit mechanisms through technological innovation. The establishment of a county-level Yellow River Basin Eco-Finance Digital Platform is recommended to integrate real-time monitoring data, such as satellite remote sensing and internet of things devices, tracking corporate carbon footprints and pollution levels. Artificial intelligence algorithms can be deployed to dynamically identify financing needs for green projects, enabling precise capital allocation and reducing misinvestment risks in high-pollution industries. This approach is particularly critical for counties with well-developed credit systems but significant ecological pressures. (2) Implement differentiated interventions based on ecological baseline conditions. Considering that digital finance may exert adverse effects in counties with low ecological quantiles, capital inflows into high-pollution industries (e.g., coal mining and paper manufacturing) should be strictly restricted in these regions. Targeted Eco-Restoration Special Loans should prioritize the application of pollution control technologies, including agricultural non-point source pollution prevention and ecological restoration of tailings ponds. For counties with medium or high ecological baselines, policies should expand the scale of green technology patent pledge financing to foster industrial upgrading, such as supporting seed industry innovation in agritech zones and developing low-carbon logistics hubs. These measures can amplify the positive ecological spillovers of digital finance in regions with stronger ecological foundations. (3) Strengthen synergies between digital infrastructure and green financial instruments. As only the digitization level of digital finance significantly promotes ecological improvement, incorporating county-level digital metrics into the evaluation criteria for green credit discounts and carbon-neutral bond issuance thresholds is advised. These metrics may include 5G coverage rates and big data platform maturity. Counties achieving high digitalization scores could be allocated preferential re-lending quotas to support ecological product value realization initiatives, such as Value of Ecosystem Services accounting and pilot financial products for biodiversity protection. Such integration would reinforce the intermediary role of technological innovation and industrial restructuring in sustaining ecological gains.

Enhancing the ecological environment through digital financial inclusion also holds potential for other developing countries, particularly in areas with fragile ecological environments. However, adjustments are necessary to account for the specific circumstances of each location. When promoting digital financial inclusion, it is crucial to integrate local environmental regulations, policy enforcement, and the regulatory capacity of financial markets to ensure financial resources do not flow into environmentally harmful areas. The successful promotion of digital financial inclusion is contingent upon the regional digital infrastructure. Therefore, initial investments should focus on building digital infrastructure, bridging the digital divide between regions, and establishing a technological foundation for the expansion of digital financial inclusion.

This paper also has some limitations: (1) There are significant geographical and economic gradient differences within the Yellow River basin, and the research conclusions may not be applicable to other non-watershed regions. In addition, as a national strategic key region in China, the Yellow River Basin enjoys special ecological compensation policies and financial pilot projects, while other regions may lack similar policy support, making it difficult to replicate the environmental effects of digital inclusive finance. The research scope can be further expanded to other river basins or non-river basin economic zones, and cross-regional comparisons can be made in order to provide a more comprehensive analysis perspective. (2) Due to the high data integrity requirements of spatial models and the objective gaps in county-level data samples, this study employs a fixed effect model without considering spatial spillover effects. In the future, acquiring more comprehensive data sources or developing new models that account for both spatial spillover effects and data integrity could enable the use of more complex spatial models in related research.

Data availability

The socio-economic data at the county level are obtained from the China County Statistical Yearbook (https://www.shujuku.org/china-county-statistical-yearbook.html. accessed on 31 October 2025) and the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database (https://data.csmar.com. accessed on 31 October 2025). The data of digital financial inclusion index comes from the open research platform for digital economy in ant financial website (https://www.deor.org.cn/research/numberdata#hotChart. accessed on 31 October 2025). The data that support the findings of this study are available from Difan Wu, upon reasonable request.

References

Ali J, Ghildiyal AK (2023) Socio-economic characteristics, mobile phone ownership and banking behaviour of individuals as determinants of digital financial inclusion in India. Int J Soc Econ 50(10):1375–1392. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-10-2022-0673

Cao S, Nie L, Sun H, Sun W, Taghizadeh-Hesary F (2021) Digital finance, green technological innovation and energy-environmental performance: evidence from China’s regional economies. J Clean Prod 327:129458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129458

Çatik AN, İlhan A, Akdeniz C (2024) Testing the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in the transport sector for OECD countries: a dynamic panel threshold approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 31(4):6372–6384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31468-7

Chen C, Fan M, Fan Y (2024) The role of digital inclusive finance in green innovation. PLoS One 19(12):e0315598. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0315598

Chen J, Gao M, Cheng S, Hou W, Song M, Liu X, Liu Y, Shan Y (2020) County-level CO2 emissions and sequestration in China during 1997–2017. Sci Data 7(1):391. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00736-3

Chen L, Du T, Wu D, Lai C (2024) Can digital financial inclusion promote the nighttime economy? - New evidence from Chinese counties’ nighttime lighting data and threshold model. Technol Econ Dev Econ 30(6):1553–1571. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2024.22245

Chen L, Liu C, Li Z, Wu D (2024) The impact of clean energy demonstration province policies on carbon intensity in Chinese counties based on the multi-phase PSM-DID method. Environ Sci Pollut Res 31(9):12978–12994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31799-5

Chen X, Zhao J, Zhou L (2024) Knowledge protects against pollution: the health effects of the cadmium rice event in China. World Dev 175:106470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106470

Chen Y, Yang S, Li Q (2022) How does the development of digital financial inclusion affect the total factor productivity of listed companies? Evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 47:102956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.102956

Cheng Q, Zhao X, Zhong S, Xing Y (2024) Digital financial inclusion, resident consumption, and urban carbon emissions in China: a transaction cost perspective. Econ Anal Policy 81:1336–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2024.02.021

Chernozhukov V, Fernandez-Val I, Melly B (2022) Fast algorithms for the quantile regression process. Empir Econ 62(1):7–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01898-0

Feng S, Chong Y, Yu H, Ye X, Li G (2022) Digital financial development and ecological footprint: evidence from-biased innovation and environmental inclusion. J Clean Prod 380:135069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135069

Ge H, Tang L, Zhou X, Tang D, Boamah V (2022) Research on the effect of rural inclusive financial ecological environment on rural household income in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):2486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042486

Gong M, Han F, Chen S, Liu T (2025) Differential analysis of the impact of adopting outsourced machinery services on land transfer between contracted and outsourced land-holding. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12(1):831. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05254-4

Guo D, Qi F, Wang R, Li L (2023) How does digital inclusive finance affect the ecological environment? Evidence from Chinese prefecture-level cities. J Environ Manag 342:118158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118158

Han M, Niu X, Tang M, Zhang B-T, Wang G, Yue W, Kong X, Zhu J (2020) Distribution of microplastics in surface water of the lower Yellow River near estuary. Sci Total Environ 707:135601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135601

Hao Y, Liu S, Zhao A, Yan G (2024) How does digital financial inclusion affect energy usage? Evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 60(4):769–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2023.2251649

He C, Qiu W, Yu J (2022) Climate change adaptation: a study of digital financial inclusion and consumption among rural residents in China. Front Environ Sci 10:889869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.889869

Işık C, Bulut U, Ongan S, Islam H, Irfan M (2024) Exploring how economic growth, renewable energy, internet usage, and mineral rents influence CO2 emissions: a panel quantile regression analysis for 27 OECD countries. Resour Policy 92:105025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2024.105025

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Balsalobre-Lorente D, Sharif A (2024) ECON-ESG factors on energy efficiency: fostering sustainable development in ECON-growth-paradox countries. Gondwana Res 135:103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2024.07.020

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Pinzon S, Jabeen G (2024) Navigating sustainability: unveiling the interconnected dynamics of ESG factors and SDGs in BRICS-11. Sustain Dev 32(5):5437–5451. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2977

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Yan J, Alvarado R, Ahmad M (2025) The nexus of economic growth, energy prices, climate policy uncertainty (CPU), and digitalization on ESG performance in the USA. Clim Serv 38:100572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2025.100572

Işık C, Ongan S, Ozdemir D, Yan J, Demir O (2024) The sustainable development goals: theory and a holistic evidence from the USA. Gondwana Res 132:259–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2024.04.014

Lee C-C, Wang F (2022) How does digital inclusive finance affect carbon intensity? Econ Anal Policy 75:174–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.05.010

Lee C-C, Wang F, Lou R (2022) Digital financial inclusion and carbon neutrality: evidence from non-linear analysis. Resour Policy 79:102974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102974

Lei X, He S (2025) Climate shocks and innovation persistence: evidence from extreme precipitation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12(1):881. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05229-5

Li G, Zhang R, Feng S, Wang Y (2022) Digital finance and sustainable development: evidence from environmental inequality in China. Bus Strat Environ 31(7):3574–3594. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3105

Li Y (2025) How does digital financial inclusion affect households’ CO2? Micro-evidence from an emerging country. J Econ Bus 133:106222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2024.106222

Liu C, Chen L, Li Z, Wu D (2023) The impact of digital financial inclusion and urbanization on agricultural mechanization: evidence from counties of China. PLoS ONE 18(11):e0293910. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293910

Liu C, Chen L, Wu D, Yuan H (2023) Multi-objective robust optimal allocation of rural integrated energy system considering energy cascade efficient utilization and flexible thermoelectric ratio. J Syst Manag, 1–23. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/31.1977.N.20231215.1417.002

Liu Y, Luan L, Wu W, Zhang Z, Hsu Y (2021) Can digital financial inclusion promote China’s economic growth? Int Rev Financial Anal 78:101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101889

Lu C, Ji W, Hou M, Ma T, Mao J (2022) Evaluation of efficiency and resilience of agricultural water resources system in the Yellow River Basin, China. Agric Water Manag 266:107605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107605

Lu X, Guo J, Zhou H (2021) Digital financial inclusion development, investment diversification, and household extreme portfolio risk. Account Financ 61(5):6225–6261. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12863

Mu W, Liu K, Tao Y, Ye Y (2023) Digital finance and corporate ESG. Financ Res Lett 51:103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103426

Mukalayi NM, Inglesi-Lotz R (2023) Digital financial inclusion and energy and environment: global positioning of sub-Saharan African countries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 173:113069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.113069

Platteau J-P, Somville V, Wahhaj Z (2014) Elite capture through information distortion: a theoretical essay. J Dev Econ 106:250–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.10.002

Qin X, Wu H, Li R (2022) Digital finance and household carbon emissions in China. China Econ Rev 76:101872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101872

Ren X, Zeng G, Gozgor G (2023) How does digital finance affect industrial structure upgrading? Evidence from Chinese prefecture-level cities. J Environ Manag 330:117125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.117125

Su H, Duan L (2025) The role of community mutual aid networks and social relationship capital in household financial vulnerability in China: heterogeneous influence of region. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12(1):897. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05259-z

Su Y, Li Z, Yang C (2021) Spatial interaction spillover effects between digital financial technology and urban ecological efficiency in China: an empirical study based on spatial simultaneous equations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168535

Wang X, Wang Q (2021) Research on the impact of green finance on the upgrading of China’s regional industrial structure from the perspective of sustainable development. Resour Policy 74:102436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102436

Wang X, Wang X, Ren X, Wen F (2022) Can digital financial inclusion affect CO2 emissions of China at the prefecture level? Evidence from a spatial econometric approach. Energy Econ 109:105966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105966

Wei D, Ahmad F, Abid N (2024) Digital financial inclusion, environment volatility and investment efficiency: Demand and supply side experiences of Chinese listed renewable energy firms. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-05575-5

Yang J, Guo X, Zhang X (2024) Analysis of the effect of digital financial inclusion in promoting inclusive growth: mechanism and statistical verification. Economics, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/econ-2022-0078

Yang L, Wang L, Ren X (2022) Assessing the impact of digital financial inclusion on PM2.5 concentration: evidence from China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(15):22547–22554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17030-3

Yuan H, Cen W, Du T (2023) Digital finance and county ecological performance—new evidence from China counties. Sustainability 15(24):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416691

Zhang F, Zhou L, Huang J (2024) “First kilometer” to realize common prosperity: impact of public bus expansion into villages on farmers’ income mobility. Appl Econ 56(40):4761–4775. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2216438

Zhang K, Qian J, Zhang Z, Fang S (2023) The impact of carbon trading pilot policy on carbon neutrality: empirical evidence from Chinese cities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(5):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054537

Zhang X, Zhou J, Liao Z, Xu H (2023) The influence of green finance on the high-quality development of cities: an empirical study on the Yellow River Basin. Singapore Econ Rev, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590823470070

Zhou L, Sun J, Hu W, Zhang Y (2023) Asset smoothing and consumption smoothing: disaster‐coping strategies in noncontiguous and contiguous destitute areas. China World Econ 31(2):223–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12475

Zhou L, Sun J, Turvey CG (2023) Conflicts, calamities and nutritional poverty traps in a peasant economy: evidence from rural China 1929–1933. Singap Econ Rev 68(03):729–759. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590819500280

Zou J, Deng X (2022) To inhibit or to promote: how does the digital economy affect urban migrant integration in China? Technol Forecast Soc Change 179:121647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121647

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following projects: [1] Project of Fujian Social Science Foundation in 2025 (No. FJ2025C036). [2] 2023 Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project of Fujian, (No. 2023J05219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZL, CJ, DW; Methodology: ZL; Software, CJ, DW; Validation: ZL, CJ, DW, JZ; Investigation: ZL, CJ, DW; Data processing: CJ, DW; Writing—review & editing: DW, JZ; Supervision: ZL; Funding acquisition: ZL. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

There are no human subjects or animals in this article and ethical approval is not applicable.

Informed consent

There are no human subjects or animals in this article, and consent to participate is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Jiao, C., Wu, D. et al. Can digital financial inclusion improve the ecological environment? Evidence from counties in the Yellow River Basin of China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1959 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06256-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06256-y