Abstract

Addressing the challenges of aging and fostering a healthy China necessitates redefining the socioeconomic role of middle-aged and elderly individuals. Despite the close link between the distribution of household financial assets and financial market stability, few studies have examined the low participation of middle-aged and elderly households in financial markets through the lens of medical resource utilization. This study was conducted to analyze the influence of the utilization level of medical resources and health capital on the financial asset allocation of these households, exploring the underlying mechanisms and differential impacts. Utilizing the 2015 and 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) datasets, this study empirically assessed the impacts of medical resource utilization and health capital on financial asset allocation via logit and Tobit models. A mediating effect model was employed to delve into the mechanisms of action. The findings indicate that medical resource utilization and health capital positively impact the financial market participation and risky asset holdings of middle-aged and elderly households, and these findings are robust. Regarding the mechanisms of action, medical resources influence allocation via health capital. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the effects on high-income and urban households are more obvious, whereas those on middle- and low-income and rural households are not. This study offers a foundation for policy decisions promoting the coordinated development of a healthy China and the financing of the aging population. Recommendations include expanding primary medical services, enhancing households’ health capital, advancing financial reform and innovation, optimizing the asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households, and addressing urban‒rural income disparities to facilitate societal and economic health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Households are the principal undertakers of consumption and savings within the national economy. Household consumption decisions directly affect market demand, thus influencing the production and investment patterns among enterprises, which is relevant for the stability of the financial market (Gomes et al., 2021). Nevertheless, constrained by differences in the investment decision-making capabilities of households in China, the distribution of household financial assets has caused issues such as the persistent simplicity of the household financial investment structure, limited participation in risky financial assets, and the uneven distribution of household wealth. The China Household Wealth Survey Report (2019)Footnote 1 revealed that within the composition of household financial assets in China, cash and deposits (current and fixed) account for nearly 90% of the total; moreover, this proportion is even greater among rural households. Real estate, which is the asset that accounts for the highest proportion of household assets, has an ownership rate exceeding 80%, whereas the ownership rate of financial assets is less than 1/8. Specifically, the proportion of risk-free financial assets is significantly greater than that of risky financial assets.

Simultaneously, population aging is expected to soon become an irreversible trend worldwide, thus generating a series of acute social problems, such as the exacerbation of wealth inequality, differences in the accessibility of medical resources and social support systems, and an increase in health gaps under the combined effect of disease burden and health risks (Chatterji et al., 2015). By the end of 2023Footnote 2, the Chinese population aged 60 years and above had reached approximately 300 million individuals, constituting 21.1% of the total population, while the population aged 65 years and above had reached approximately 210 million individuals, accounting for 15.4% of the total population. According to international definitions, China has an aging society (with a proportion of the population aged 65 and above exceeding 14%). This large and rapidly evolving aging population size will impose considerable pressure on and pose severe challenges for household financial asset decisions and pension systems in China. Considerable assets typically accumulate in middle-aged and elderly households in China. However, such households demonstrate relatively limited engagement in the financial market, especially the risky financial market, resulting in an insufficient proportion of property income in household disposable income (Bialowolski et al., 2022). A considerable number of middle-aged and elderly households hold substantial sums of money but are unaware of their effective allocation, which is not conducive to preserving and appreciating household wealth or the balance and control of the asset portfolio risks of households and has an extremely negatively impact on the operational capacity of the entire national economy (Brunetti et al., 2016). Data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) show that during the 2011-2018 period, only approximately 2% of the elderly population aged 60 and above had invested in risky financial assets such as funds and stocks, which is far lower than the average holding rate of risky financial assets of Chinese residents, which is 59.6%, as calculated by the People’s Bank of China. In contrast, the proportion of stock assets held by the elderly population in the United States is as high as 63%, and 40% of retail investors in Japan are people aged 60 and above (Shao and Chen, 2024). Therefore, analyzing the characteristics of middle-aged and elderly households in terms of financial asset allocation, determining how to guide them to effectively make sound financial investment decisions and conducting an in-depth investigation of their selection behaviors, driving factors and mechanisms of action for risky financial assets can facilitate not only improvements in the material life of middle-aged and elderly households and the alleviation of pension and related financial pressures but also the stable operation of the financial market and the healthy development of the social economy.

Given the deterioration in physiological functions, middle-aged and elderly individuals encounter particularly notable health risks such as disability, disease, and even mortality. They are also more likely to adjust their asset decisions within the family because of variations in health levels (Liu et al., 2023). Hence, health can directly impact the medical care expenditures and risk preferences of a given household and thus influence the choice of asset allocation methods and types for the family (Yogo, 2016; He et al., 2025). Owing to the significant role played by health, an increasing number of scholars have researched individuals’ health quantitatively, considering it a type of estimable asset or capital reserve among people, namely, health capital. Grossman (2017) holds that although health cannot be directly transferred through savings or investments in the real-world environment and there is no technical means of guaranteeing health, similar to other direct assets, the value of health capital decreases over time. Middle-aged and elderly individuals are more inclined to experience a jump-like decline in health capital due to health shocks; thus, they must continuously invest in factors that generate health to maintain their health stocks and limit the rate of health capital loss. Theoretically, when health capital declines, household expenditures frequently increase significantly, resulting in reduced household savings and wealth levels, ultimately altering the degree of risk preference and expectations of family members and the family; hence, this is directly manifested in current and future household consumption levels and the degree of participation in the financial market.

As a highly efficient and extremely important factor for health production, the utilization level represents the convenience of medical services and the affordability of medical service costs, and it directly affects the degree of medical service demand of middle-aged and elderly individuals, thus positively influencing health capital (Ma and Shen, 2023). When the utilization level of medical resources is limited, it may increase the rate of health capital loss, thus adversely impacting future income levels, household wealth, and the asset structure. Simultaneously, the additional economic burden and family care resulting from a low utilization level of medical resources could further influence the economic decisions and financial behaviors of the family regarding, for example, consumption and savings (Liu et al., 2025). Enhancing the utilization level of medical resources is important for achieving healthy aging and the high-quality development of society and the economy. However, the utilization level of medical resources in China exhibits an inverted pyramid-shaped trend (Wan et al., 2021). Manifesting this trend, residents still preferentially select tertiary and secondary hospitals with better medical resources for emergency medical treatment, and the proportion of individuals choosing primary medical institutions is relatively low, resulting in low allocation frequency. Better understanding the utilization level of medical resources could help clarify the actual effects and potential problems in households’ health capital and financial asset allocation and define the future development direction, thereby maximizing the role of medical resource utilization in promoting healthy aging and high-quality economic and social development.

Given the discussion above, in this paper, data from the CHARLS in 2015 and 2018 are employed, with a focus on middle-aged and elderly households with a higher demand for medical services and lower holding rates of health capital and financial assets, thus placing the utilization level of medical resources, health capital, and households’ financial asset decision-making behaviors under the same analytical framework. Moreover, the varying influences on middle-aged and elderly households with different endowment characteristics are examined. The contributions of this paper are as follows: first, the effect of health capital on households’ financial assets has been confirmed in numerous studies (Shao and Chen, 2024). However, as a key antecedent of health capital, the influence of the utilization level of medical resources on middle-aged and elderly households’ financial asset allocation behavior remains uncertain. In China, as the levels of medical institutions increase, the initial payment standards for hospitalization rise, and the reimbursement rate decreases. The degree of self-payment has an impact on the asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly people (Tang and Li, 2022). Patients do not directly modify outpatient or inpatient behaviors to utilize medical resources rationally; instead, they release the medical pressure on their households, communities, and professional institutions, alleviating the pressure on large hospitals and the medical burden of patients. Unlike previous research, this study, from the perspective of the hierarchy of medical resource allocation in China, distinguishes between primary medical institutions and large hospitals to determine patients’ utilization of medical resources. It then explores the specific impact on their financial asset allocation behavior, providing a new perspective for understanding the financial decisions of middle-aged and elderly households. On the other hand, from the practical needs of medical service utilization, despite the high medical cost, the Chinese middle-aged and elderly households still prefer large hospitals and choose a lower proportion of primary medical institutions (Chen and Zhang, 2024). Therefore, this paper takes health capital as an important influencing mechanism and constructs a theoretical framework of the impact of the level of medical resource utilization on the financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households. This work provides new evidence for enhancing our understanding of how middle-aged and elderly households use primary medical services. Second, compared with most existing studies that aim to measure only a single dimension, the utilization level of medical resources, health capital, and households’ financial asset decisions are characterized through multiple indicators; the influence relationships among the utilization level of medical resources, health capital, and financial asset decisions of middle-aged and elderly households are more accurately assessed empirically; and the results of theoretical research are validated. Third, the heterogeneous influences of the income level and different household registration statuses are investigated. This study not only provides empirical evidence for revealing the specific factors that limit the participation of middle-aged and older households in the financial market and for clarifying differences in the utilization level of medical resources but also provides targeted and operational decision-making reference data for the concurrent development of medical resource popularization and financial allocation among middle-aged and older households. In doing so, this study ultimately promotes financial reform and innovation, contributes to the development of primary medical services, and lays a foundation for the subsequent optimization of the institutional design of primary medical services in China.

Literature review

Health capital and households’ financial asset decision-making behaviors

The literature on household financial asset decision-making behavior is abundant. Most studies are based on demographic characteristics or economic and social perspectives, including age (Li and Liu, 2025), personal skills (Wang et al., 2023), job quality (Name and Liu, 2025a), green finance (Wang and Ren, 2025), artificial intelligence (Liu, 2025b), and basic medical insurance (Liu et al., 2025). Health capital is an essential component of household human capital. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted both in China and elsewhere, revealing that health capital substantially influences the allocation of household financial assets among residents. Li et al. (2025) determined that the health capital of family members significantly impacts households’ asset allocation preferences. When a household experiences health shocks, the proportion of risky financial assets held decreases, and greater attention is devoted to the safety and liquidity of assets; thus, households opt for a more conservative investment strategy. Hangoma et al. (2018) reported that health shocks curtail household consumption and available income and that an increase in medical expenditures causes a reduction in the scale of household financial assets. Yogo (2016) reached the same conclusion: that is, a decrease in health levels causes a reduction in the holding probability and proportion of financial assets (particularly risky assets) among households and the concurrent transfer to assets with higher security (such as productive assets and real estate). Coile and Milligan (2009) focused on elderly households after retirement to analyze the impacts of age and health shocks on household asset portfolios, demonstrating that age adversely affects changes in household car ownership, stocks, and real estate and positively influences the holdings of liquid assets and savings. Yang et al. (2024) revealed that health risks significantly reduce the proportion of risky assets held. This effect occurs among middle- and low-income and elderly households but not among high-income households. Liu et al. (2022) investigated the decision-making behavior of Chinese households with respect to financial assets from the perspective of the liquidity of financial assets and reported that health shocks exert a relatively considerable effect on the liquidity of household financial assets. This finding suggests that, owing to defects in system design, more medical resources are allocated to high-income groups, which constitutes a significant inequality in the development of health capital for low-income groups. Li and Bo (2025) found that health concerns have a significant positive correlation with financial asset allocation, as they cause families to experience additional economic burdens in the future. To ensure there are sufficient funds available when health challenges occur, families plan and adjust their financial asset allocation strategies in advance. Notably, Li and Bo (2025) did not distinguish between risky and risk-free financial assets.

Most scholars maintain that there are multiple reasons why a decline in health capital is detrimental to the allocation of household financial assets among residents. Intuitively, an increase in health risks will not only result in an increase in family medical expenses but also result in direct and indirect costs by reducing labor productivity, labor supply and family income. In terms of direct costs, Li et al. (2025) noted that family medical expenditures and health risks increase significantly when families are confronted with health shocks. This expenditure-related pressure directly leads to a reduction in household risky financial assets. Specifically, when the health status of household members deteriorates, households must increase their investment in medical care. These additional expenditures are frequently drawn from the financial assets of the households, thus reducing the scale of their financial assets. Wang and Sun (2020) reported that an increase in the health expenditures of residents not only reduces the amount of liquid funds available for investment within the family but also affects the risk preference and asset allocation strategy of the family. In the face of health risks, households are more inclined to reduce their holdings of risky and high-return assets such as stocks and funds and instead increase the allocation ratio of risk-free assets such as cash and bank deposits to ensure the liquidity and security of funds. Moreover, health capital is a key mediating factor in the impact of medical expenditures on the allocation of household financial assets. With the acceleration of population aging, a decline in the health capital of an individual manifests as a deterioration in physical strength and cognitive ability. Shin (2021) studied the financial allocation decisions of over 20000 Americans aged 50 and above and reported that older adults with advanced objective memory typically possessed more risky financial assets. In terms of indirect costs, Cheng et al. (2024) conducted a study on over 100,000 elderly people in Singapore and found that the employment rate and labor income of men and women with lower educational levels were significantly lower when they were exposed to health shocks, and they were more likely to retire after falling ill.

The utilization level of medical resources and health capital

Medical resources usually refer to production factors that provide medical services, including medical and health technology and service personnel, medical institutions, medical devices and facilities, medical expenses, medical beds, etc. (Wan et al., 2021). The medical process is very similar to the production process. In this process, medical resources need to be utilized and transformed into medical services, which ultimately benefit patients themselves. Production relations and productive forces must also be effectively matched. However, in terms of the actual situation, there is still a considerable mismatch between productive forces and production relations in China’s medical system. Facing this contradiction, it is necessary to rely on the optimal allocation of medical resources to improve the frequency of patients’ utilization of medical resources. Through regulation and intervention, government departments or market departments allocate medical resources equally and efficiently to different regions and social groups. The main purpose of medical resource allocation is to optimize the social and economic benefits of medical resources (Zhao et al., 2025b), which also indicates that improving the utilization of medical resources holds important practical significance (Wang et al., 2024).

The utilization level of medical resources referred to in this study focuses mainly on the microlevel of medical resource allocation, which is an expression of an individual’s health needs, specifically including the choice of medical treatment method and medical institution. The choice of medical treatment method refers to an individual’s choice between outpatient services and hospitalization. The choice of medical institution refers to the individual’s selection of a medical institution on the basis of subjective medical preferences such as whether the medical institution is a medical insurance reimbursement institution, the distance of the medical institution, the accessibility of medical resources, the scope of services provided by the medical institution, and the quality of medical resource services (Ordu et al., 2021).

Differences in the utilization level of medical resources can influence the duration, cost, and convenience with which residents can obtain medical and health services; thus, they directly influence health capital. Davies and Schramme (2025) proposed that health capital exhibits positive externalities; that is, individuals can significantly increase their health levels by effectively leveraging medical resources and fulfilling their demands for health services. Gao et al. (2025) reported that the ability to obtain medical resources via the internet is positively correlated with the health levels of regional residents and that the abundance of medical resources can considerably increase the accumulation of health capital. Guo et al. (2025) indicated that government investment in health capital through measures such as optimizing medical resources, promoting the integration of medical resources, leveraging technological advancements, and rationally investing in industrial capital can significantly increase the health capital of the public and promote the health and well-being of individuals and society. The impact of the utilization level of medical resources on health capital is not constant; rather, it exhibits regional differences. Wan et al. (2021) and Wu et al. (2022) empirically demonstrated that the inequality in medical resource allocation among regions and the trend of low utilization frequency have increased, indicating a failure to adapt to the diverse health service needs of residents. There is an urgent need to transform the inverted pyramid-shaped structure of the medical and health service system and to balance the fairness and frequency of medical resource allocation among regions.

Differences in the utilization levels of medical resources have raised increasing concerns worldwide (Richardson et al., 2022). Top et al. (2020) utilized the data envelopment analysis (DEA) method to evaluate medical and healthcare utilization in 36 African countries. They discovered that the utilization level of medical and healthcare in 15 countries is low. There is still a severe shortage of medical resources allocated to the African region to meet people’s basic health capital needs. Nasiri et al. (2024) reported that after the implementation of the Health Transformation Plan (HTP) in Iran, an uneven distribution of health resources still existed, especially in terms of the geographical concentration of comprehensive physicians. This unreasonable distribution could limit the accumulation of health capital for certain groups and may aggravate health inequalities in society. In some professional fields, this phenomenon has intensified inequality. In Pakistan, which is subject to frequent changes in government and pressure from a rapidly growing population, almost all sectors are subject to high-level political intervention, which affects the rational allocation of medical resources to medical and health departments, resulting in an insufficient drug supply and the inability of health facilities to fully function, affecting the health activities of the public (Nawaz et al., 2021). In China, the implementation of the urban‒rural dual system has resulted in a much lower utilization rate of primary medical resources in rural areas than in urban areas. Zhao et al. (2025a) proposed that, while the government focuses on increasing its investments in medical and health finance, increasing the capacity of primary medical and health institutions as health gatekeepers and balancing the allocation of medical resources are even more crucial.

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesis

Health capital and financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households

The asset portfolio model established by Edwards (2010) incorporates health into the utility function and analyzes the relationship between investors’ health status and their allocation behavior of risky assets; it assumes the existence of two types of investors with infinite life expectancy: investor \(h\), whose current health capital level is relatively high but faces the risk of a decline in health capital, and investor \(u\), whose health capital level is relatively low and who incurs medical expenses to maintain the necessary level of health. At the same time, it is assumed that investors have no labor income but only financial asset returns (both risky and risk-free financial assets). The model indicates that when the level of health capital is low, investors will increase their medical expenditures (such as medical services, nursing, etc.) to avoid or mitigate further losses of health capital and reduce the allocation of risky assets.

Drawing on the Edwards asset portfolio model and combined with Grossman’s (1972) health demand theory, this study further determines whether the utilization level of medical resources affects household asset allocation behavior by constructing an intertemporal asset allocation model at the household level.

For all households with wealth \({W}_{t}\) in period \(t\), consumption expenditure \({C}_{t}\), and health capital level \({H}_{t}\), their constant elasticity of substitution utility function based on consumption \({C}_{t}\) and health \({H}_{t}\) is as follows:

where \(\varphi\) represents the relative preference degree of the household for \({C}_{t}\), and \(\gamma\) represents the substitution elasticity coefficient. In period \(t\), the household invests in risky financial assets and risk-free financial assets. The investment proportion of risky financial assets is \({\alpha }_{t}\), and the investment proportion of risk-free financial assets is \(1-{\alpha }_{t}\). Among them, \(0\le \alpha \le 1\). The expected rate of return of risky financial assets is \(R\), the fixed return rate of risk-free assets is \({R}_{f}\), and the rate of return of the household’s financial asset investment portfolio is \({R}_{t+1}={\alpha }_{t}R+(1-{\alpha }_{t}){R}_{f}\).

For household \(u\) with a lower level of health capital, in addition to the aforementioned returns on household financial assets, its wealth accumulation is also influenced by labor income and medical expenditures. Specifically, the household has labor income \({Y}_{t}\), which reflects the stable cash flow generated by human capital. At the same time, household \(u\) purchases medical services at price \({P}_{t}\) in period \(t\). If the household’s utilization level of medical resources is high, it can be reasonably diverted to the corresponding professional institutions according to specific circumstances, effectively reducing medical service costs and reducing household medical expenditures (Liu et al., 2023). Setting the proportion of this deduction as \(\lambda\), \(\lambda \in (0,1)\), then the household’s medical expenditure in period \(t\) is \((1-\lambda ){P}_{t}{H}_{t}\), and the level of wealth in period \(t+1\) is calculated as follows:

According to Grossman’s (1972) theory of health demands, individuals or families can invest in health through medical expenditures, increasing the health capital stock. The health capital at \(t+1\) can be represented as \({H}_{t+1}=(1-\delta ){H}_{t}+{I}_{t}\). Here, \(\delta\) represents the health depreciation rate, and the higher the age, the higher the health depreciation rate. \({I}_{t}\) represents health investment. Since health investment includes both monetary and time investments, for the sake of simplifying the analysis, only the element of medical expenditure is considered here; that is, \({I}_{t}=(1-\lambda ){P}_{t}{H}_{t}\). At this point, the target utility function and constraints of the household can be expressed as follows:

The optimal proportion of risky financial assets for household \(u\), which has a relatively low level of health capital, is

Household h with a higher level of health capital is at risk of a decline in health level \({\pi }_{h}\). If the health capital of household h does not decrease in period t, then no medical services need to be purchased. In this case, the level of wealth in period t+1 is calculated as follows:

The health capital level in period \(t+1\) is \({H}_{t+1}^{h}=(1-\delta ){H}_{t}\). If the health condition of household members deteriorates in period \(t\), the household must purchase medical services to compensate for the decline in the level of health capital. At this time, the level of wealth and health capital of household \(h\) in period \(t+1\) are the same as those of household \(u\). Therefore, the target utility function of household \(h\) is calculated as follows:

The optimal proportion of risky financial assets for household \(h\), which has a higher level of health capital, is as follows:

Compared with the derivation of household \(u\), the core difference lies in the following: household \(h\) only pays medical expense \((1-\lambda ){P}_{t}{H}_{t}\) with a probability of \({\pi }_{h}\). The difference in expected costs leads to a change in the risk asset allocation ratio \({\alpha }_{t}^{h}\) of household \(h\), where the denominator includes \({\pi }_{h}\), ultimately resulting in \({\alpha }_{t}^{h} > {\alpha }_{t}^{u}\).

It can be seen that the level of health capital is an important factor influencing households’ allocation of risky assets. For household \(h\) with a higher level of health capital, the uncertainty from the decline in the level of health and associated medical expenses is relatively smaller. They are less concerned about their future finances, and, therefore, are more willing to allocate a higher proportion of risky assets. However, for household \(u\) with a lower level of health capital, to maintain health, they must purchase medical services. The certainty of medical expenses makes them more inclined to adopt a conservative allocation and reduce the proportion of risky assets held. The above indicates that the higher the level of health capital, the stronger the households’ willingness to allocate risky assets.

On this basis, the following hypothesis is formulated in this paper:

H1: The higher the health capital of middle-aged and elderly households is, the more inclined they are to make risky financial asset decisions and increase the proportion of risky financial asset holdings.

Furthermore, regardless of the current level of health capital, when a household needs to purchase medical services to maintain the level of health capital, improving the utilization level of medical resources can reduce the cost and time of treatment and care, alleviate the burden of obtaining medical resources, lower the threshold for seeking medical care, and enhance the accessibility of medical services and medical resources. This can effectively safeguard the household’s health capital and directly increase the probability and proportion of holding risky financial assets.

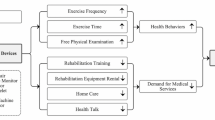

In summary, the utilization level of medical resources determines the medical expenditures of middle-aged and elderly households as well as the recovery and improvement in individual health capital. Health capital influences the future income level and wealth structure of middle-aged and elderly households and affects their economic decisions and financial behaviors, such as the consumption and savings of other goods. Therefore, from the perspective of a causal logical relationship, when analyzing the influence of the utilization level of medical resources on the financial asset decision-making behavior of middle-aged and elderly households, health capital must be incorporated as a factor. On this basis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: The higher the utilization level of medical resources of middle-aged and elderly households is, the better the health capital of household members can be guaranteed.

H3: The utilization level of medical resources can impact financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households through health capital.

Experimental design

Model construction

Double-hurdle model

Regarding the allocation of risky financial assets in middle-aged and elderly households, this study not only determines whether they participate but also takes into account their holding proportions to more comprehensively understand the situation of risky financial asset allocation in these households. At the same time, only the proportion of risky financial assets held by households that participate in these investments can be observed, while for families that do not participate in investments, the observed values are all 0; thus, the data are censored. Academia typically employs the Tobit model for analysis. However, the drawback of the Tobit model is that it treats participation behavior and the holding proportion as the same decision-making process for analysis, and regards the zero value as a corner solution. Cragg proposed the double-hurdle model as an extension of the traditional Tobit model, which relaxes the assumptions of the Tobit model and regards “decision” and “degree” as two different stages. This model can obtain different estimated coefficients. Therefore, this study uses the double-hurdle model to conduct an empirical test on the risky financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households, compensating for the shortcomings of the traditional Tobit model. It not only solves the estimation result bias caused by directly deleting zero observations but also avoids the endogeneity problem of the two-stage equation (Pan and Sun, 2022), thereby obtaining more rigorous estimation results.

Firstly, the decision equation for the first hurdle is constructed as follows:

where \({T}_{i}^{\ast }\) represents whether the middle-aged and older household \(i\) has risky financial assets. If the middle-aged and elderly household \(i\) has such assets, then \({T}_{i}\)= 1; otherwise, \({T}_{i}\)= 0. \({Z}_{ij}\) represents the level of medical resource utilization, health capital and other potential factors that affect the participation of the middle-aged and elderly household \(i\) in risky financial assets; \(\gamma\) represents the estimated coefficient; and \({\upsilon }_{i}\) represents the random error term.

Furthermore, the degree equation for the second hurdle is as follows:

where \({y}_{i}^{\ast }\) represents the proportion of risky financial assets held by the middle-aged and elderly household \(i\); if \({T}_{i}^{\ast } > 0\), the middle-aged and elderly household possesses risky financial assets \({T}_{i}=1\); if \({T}_{i}^{\ast } > 0\) and \({y}_{i}^{\ast } > 0\), the proportion of risky financial assets held by the middle-aged and elderly household is \({y}_{i}^{\ast }={y}_{i}\); \({X}_{i}\) represents a series of related factors, such as the utilization level of medical resources and health capital that affect the participation degree; \(\beta\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\) represent the estimated coefficients; and \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) represents the random error term.

Based on the above equation, the log-likelihood function is constructed as follows:

where l n L represents the log-likelihood value, and \(\phi (\cdot )\) represents the probability density function of the standard normal distribution. By using the maximum likelihood estimation method, all the required parameter values can be obtained.

Mediating effect model

On the basis of previous health analysis studies, the efficient utilization of medical resources is a crucial aspect of health investment. The level of health capital can be influenced by efficient medical resource utilization, subsequently impacting the financial asset allocation behavior of middle-aged and elderly households. Therefore, in this study, a mediating effect model is constructed to examine whether the utilization level of medical resources affects the financial asset allocation behavior of middle-aged and elderly households through its impact on the health capital level. In traditional stepwise regression coefficient analysis methods, introducing a mediating variable as a control variable into the main regression process may lead to issues of endogeneity bias, resulting in inconsistent estimated coefficients. Hence, there is no need to implement the third step of the traditional three-step method; instead, providing a theoretical and intuitive explanation of the impact of the mediating variable on the explained variable suffices (Jiang, 2022). The mechanism of action of the mediating effect of long-term care insurance is expressed as follows:

where \(UMR\) denotes the utilization level of medical resources; \(HC\) denotes health capital; \(a\) denotes the impact of the utilization level of medical resources on the intermediary variable; \(C\) denotes the control variables; and \(\eta\) denotes the random error term.

Selection of data sources and variables

The data in this study were obtained from the 2015 and 2018 waves of the CHARLS, a survey conducted by the China Social Science Survey Center at Peking University. This survey targets individuals aged 45 years and above and their spouses to comprehensively investigate aging-related issues through interdisciplinary research. With the use of a stratified random sampling method, this survey covers various domains, including demographics, health status, healthcare and insurance, occupation, retirement, pension income, expenditure, assets, and community characteristics; it covers 150 counties and 450 communities in 28 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) and has good national representativeness.

Recognizing the pivotal role of households in asset allocation decisions and considering constraints related to data availability, this study focuses primarily on data pertinent to middle-aged and elderly households. To increase the comparability among samples and to reduce sample duplication, following Zhang et al. (2025), we retain the household heads of each family whose age is greater than or equal to 45 years as household representatives to form household samples. Second, owing to the decline in cognitive ability among people of advanced age and the small sample size, samples with household heads over 80 years old are excluded. After excluding samples with missing or significantly abnormal key variables, two periods of mixed cross-sectional data for 2015 and 2018 are formed, with a sample size of 1,888 households. In the subsequent sections, the dependent variables, core explanatory variables and control variables are explained.

Dependent variables

Owing to incomplete information on productive household assets in the CHARLS data, this paper largely focuses on household financial risk assets based on the work of Shao and Chen (2024). Thus, we examine participation in holding risky financial assets and the proportion of such assets in total financial assets.

Participation in holding risky assets refers to whether a household has invested in at least one type of risky asset, including stocks, funds, or loansFootnote 3. If is the household has done so, the value is 1 and 0 otherwise.

The proportion of risky financial assets represents the ratio of such assets relative to the overall family finances, including stocks, funds and loans, covering both risk-free (e.g., cash deposits) and risky (e.g., stocks) assets. The scale of household financial assets includes all risk-free financial assets (including cash, bank deposits, Treasury bills, housing provident funds, etc.) and all risky financial assets.

Core explanatory variables

A key focal point explored in this paper is the impact of health capital on various related aspects, with reference to the studies of Bu et al. (2024). Health capital evaluation encompasses subjective self-assessment indicators along with objective metrics. As a subjective indicator, self-assessment of health status reflects an individual’s judgment of his or her overall health condition. Meanwhile, to identify the real health status of individuals more objectively, this paper constructs objective indicators through health quality.

Self-assessment of health status. Self-assessment of health status is defined using the binary method based on the item “How do you think your health condition is?” in the questionnaire. In the CHARLS data, individuals’ evaluations of their own health conditions are divided into five levels: very good, good, average, poor and very poor. To be more targeted, in this paper, very good, good and average are combined into the “health” indicator, and poor and very poor are combined into the “unhealthy” indicator. Individuals who consider their health conditions to be very good, good or average are assigned the value of 1, and those who consider their health conditions to be poor or very poor are assigned the value of 0.

Health quality indicator. The health quality indicator was originally proposed by Kaplan and Anderson (1988). The value of this indicator varies between 0 and 1, where a value of 0 indicates death, and a value of 1 indicates optimal wellness. Notably, lower numbers indicate lower health capital held by middle-aged and elderly households. This indicator comprises action, physical activity, social activity, and symptom indicators. Each element is divided into three distinct states, and corresponding weights are assigned to these four indices during construction. Specific aspects of the CHARLS survey conform to each indicator according to weight coefficients that are comparable to those adopted by Kaplan and Anderson (1988); this enables the derivation of the health quality indicator for middle-aged and elderly households that objectively mirrors the size of their health capital (health quality indicator = 1 + W*action indicator+W*physical activity indicator+W*social activity indicator+W*symptom indicator)Footnote 4.

Another major explanatory variable of this paper is the utilization level of medical resources. Incorporating the research of Sun and Luo (2017) and in view of the characteristics of the CHARLS database, this paper selects the number of visits and hospital grades to measure the utilization level of medical resources, including the following:

-

The number of visits for outpatient treatment in the last month (frequency of monthly outpatient visits).

-

The number of hospitalizations in the last year (frequency of annual hospitalizations).

-

The total number of visits to community healthcare service centers, clinics or nursing homes in the last month (primary healthcare institution visits).

-

The total number of visits to comprehensive/specialized/traditional Chinese medicine hospitals in the last month (visits to large hospitals).

Control variables

Control variables are incorporated to consider the influence of other factors on the impact of long-term care insurance on financial asset allocation. In line with previous studies (Shao and Chen, 2024;He and Lin, 2024; Liu et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2024), this study selects control variables that may affect the decision-making process regarding financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly individuals to evaluate the net effect. These variables primarily pertain to individual basic attributes and family circumstances. Individual characteristics include the age of the household head, the household registration status, education level, and medical insurance participation. Household characteristics include the number of family members, annual family income, annual family expenditures, and household food expenditures. Specific definitions and assignments of these variables are provided in Table 1.

According to Table 2, only 6.4% of households hold risky financial assets, with the average proportion of risky assets to total assets reaching only 3.9%. These findings suggest a relatively limited inclination toward investing in risky financial assets among middle-aged and elderly households in China, resulting in overall low market participation. With respect to individual characteristics, the average age of the financial decision maker of the household is approximately 61 years. Most individuals in the sample exhibit an education level at or below the elementary school level; they largely hail from rural areas, and they have an average household size of approximately three members. These descriptive statistics are largely consistent with those of prior research (Shao and Chen, 2024), indirectly reflecting the typical nature of the sample results obtained in this study.

Analysis of the empirical results

Baseline regression analysis results

After checking for multicollinearity, it was found that the variance inflation factors were all below 5, far less than the critical value of 10; additionally, none of the correlation coefficients exceeded 0.5. Therefore, the problem of multicollinearity can be preliminarily excluded, which provides a basis for further testing the rationality of the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses. Additionally, the Durbin–Watson values are all close to 2, indicating no serial correlation problem in the model. All the DfBeta coefficients are less than 1. According to the criteria of Viechtbauer and Cheung (2010), the sample data do not have significant outliers.

Table 3 provides an analysis of the impacts of the utilization level of medical resources and health capital on financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households. After controlling for a series of relevant variables, subjective health capital and objective health capital significantly promote household financial asset allocation. Specifically, subjective health capital significantly and positively affects household participation in holding risky financial assets, with proportions of subjective health capital and objective health capital of 1% and 5%, respectively; the regression coefficients are 0.065 and 0.067, respectively.

Objective health capital positively impacts household participation in holding risky financial assets, and this result is significant at the 5% level. The regression coefficient is 0.111. However, the influence on the proportion of households holding risky assets is not significant. One possible reason is that health quality indicators are an objective form of health capital based on facts and data. Such objective indicators can hardly directly reflect the feelings and experiences of residents or can hardly be quantified at any time. Therefore, even when the level of objective health capital is relatively good, middle-aged and elderly families may invest in risky financial instruments due to future healthcare risks but may not significantly adjust their holdings of risky assets out of precautionary savings motives. Based on these results, H1 is partially confirmed.

The impact of medical resource utilization on financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households is examined. As indicated in Table 3, the number of monthly outpatient visits significantly and negatively influences participation in holding risky assets and the proportion of such assets. This might be because fewer outpatient visits indicate a household’s better health condition, resulting in lower expected medical expenses, which leads to a lower demand for liquidity of funds and a stronger risk tolerance. Households are thus more willing and capable of participating in risky financial asset investments. Conversely, the frequency of visits to primary healthcare facilities significantly and positively impacts participation in holding risky assets and the proportion of such assets; this might be because, first, regular visits to primary healthcare institutions (such as for chronic disease management, health check-ups, and vaccinations) help detect health issues early, reducing the risk of high medical expenses due to severe treatments in the future. Thus, the preventive savings needed by households to cope with health uncertainties can be relatively reduced. Second, the services provided by primary healthcare institutions in China are mostly basic and inclusive. The medical expenses are relatively low, and the self-expenses after insurance reimbursement are also low, thus releasing more disposable income in the household.

Based on the above results, middle-aged and elderly households may be overly dependent on large hospitals, especially in treating mild cases as serious illnesses and providing insufficient care. As the utilization efficiency of medical resources improves, the number of outpatient visits can be reduced, and the pressure of outpatient visits can be transferred from large hospitals to primary medical institutions. Therefore, the regression results of the number of outpatient visits and hospital grades in this study indicate that the coefficient of monthly outpatient visits is negative, while the number of visits to primary medical institutions is positive, suggesting an increase in the utilization level of medical resources. This factor further reduces hospitalization reimbursement expenses and daily care service costs for families, alleviates the problem of tight utilization of medical resources, and provides an opportunity to adjust economic decisions or financial behaviors, such as consumption and savings. This study further analyzes the use of monthly outpatient visits and visits to primary medical institutions as proxy variables for the utilization level of medical resources.

Robustness testing

Endogeneity treatment

In China, the utilization level of medical resources is highly related to the region where residents live and the tiered medical system (Feng et al., 2023). It is relatively independent of individual subjective economic decisions, and, even though it has an inverse causal relationship with financial asset allocation, this relationship is relatively weakFootnote 5. Health capital is endogenous and closely linked to the household and economic environments, directly influencing future choices. Moreover, households may invest in risky financial assets to generate returns that can be used to cover increased healthcare expenditures, thus impacting their health capital in reverse. Consequently, potential endogeneity issues may influence the estimated effect of health capital on financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households.

To mitigate potential endogeneity problems and ensure the robustness of the estimates, instrumental variable (IV) estimation is employed. Following Lei and Lin (2009) and Shen and Yu (2021), this study uses the overall health capital of the sample community as an instrumental variable, and measures it by the average value of the subjective self-reported health status and objective health quality indicators within the community of the sample households. The specific steps are as follows: In the first stage, health capital is taken as the dependent variable and the instrumental variable is used as the independent variable for an OLS regression, obtaining the fitted values of the endogenous variable; in the second stage, the fitted values of the endogenous variable are included in the double-hurdle model for regression.

The selection of instrumental variables is based on considerations of relevance and excludability: in terms of relevance, the health capital status of the community where one is located is closely related to an individual’s health capital. The poorer the overall health status of a community is, the more often it reflects that the medical facilities in the community are relatively lacking, the medical level is relatively low, and the natural environment (air, greenery, water quality, etc.) is not conducive to physical health. These characteristics of the community significantly affect the health level of individuals (Seo et al., 2021). With respect to excludability considerations, the overall health status of a region represents a macroscopic average value, while the financial asset allocation of families is a decision made according to the individual circumstances at the micro level. In a healthy region, the risk investment participation of an unhealthy household will not increase simply because the overall health status of the region is good; this is because household members usually only care about the health level within their own household, and the average health level of other residents in the community does not directly affect the risky financial market participation and asset holdings of a single household (Shen and Yu, 2021). At the same time, changes to the health level of a region can be quite slow. Individual investors in households will pay more attention to information directly related to asset prices. Under the condition of no extreme public health events, a region’s health level is a very weak signal and will not become a direct factor in households’ financial asset allocation decision-making (Gan et al., 2020). The regression results of the second stage are presented in Table 4.

The first-stage regression analysis findings provided in Table 4 reveal that the F statistic significantly exceeds 10, indicating a notable correlation between the instrumental variables and endogenous variables. In the second stage regression, the chi-square values were all statistically significant at the 1% level, and the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test values were all statistically significant at the 5% level or higher. This indicates the equation has an endogeneity problem. After considering the endogeneity issue, the direction and significance of the impact of health capital on the financial asset decision-making behavior of middle-aged and elderly households are basically consistent with those in Table 3, although the coefficient has significantly decreased. This finding suggests that if the endogeneity issue is not addressed, the benchmark regression results will be overestimated. However, the impact effect of health capital on the financial asset decision-making of middle-aged and older families still holds, partly confirming H1.

Winsorize

Following Wang et al. (2023), we winsorized the data to mitigate the potential impacts of outliers on the estimation outcomes. The primary variables were winsorized at the 5% and 95% percentiles before regression analyses were conducted again via an adjusted sample range, as detailed in Table 5. The direction and significance of the influences of the utilization level of medical resources and health capital on financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households closely conform to benchmark regression, indicating the robustness of the research findings.

Adjust the standard errors, core explanatory variables and the dependent variable

To further verify the robustness of the benchmark regression results, this paper adjusts the robust standard errors, health capital, medical resource utilization level, and risky financial assets based on the benchmark regressionFootnote 6. First, the clustered robust standard errors in the baseline regression are adjusted to heteroscedastic robust standard errors. The regression results with adjusted robust standard errors and the inclusion of households fixed effects still match the baseline regression results, demonstrating the robustness of the baseline regression results. Second, the health indicators mentioned in the previous text mainly focused on physical health. In this study, the depression scale provided by CHARLS was used to measure the mental health of middle-aged and elderly peopleFootnote 7 To comprehensively identify the impact of health capital on the asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households, the results showed that the higher the health capital, the more likely households are to make risky financial asset decisions and increase the proportion of these assets, which was basically consistent with the baseline regression results. Third, since the measurement of medical resource utilization level in this paper is based on the count variable of the number of visits, there may be a problem of overdispersion. The indicators of the medical resource utilization level are log transformed again, and the regression results are basically consistent with the baseline regression results. Finally, after excluding loans from the participation and the proportion of risky financial assets, the coefficients of the regression results decreased significantly, although the significance and direction remained basically unchanged. This finding indicates that, after not considering the possible bias caused by a small sample size, the influence of health capital and medical resource utilization is still robust.

Mechanism analysis

Given the analysis above, the utilization level of medical resources may also influence the financial decision-making behavior of middle-aged and elderly households through their health capital. Therefore, this mechanism is investigated in depth. Since only monthly outpatient visits and visits to primary healthcare institutions yield significant impacts, as detailed in Table 3, they are employed as proxy variables for mechanism analysis. The mediation model regression results are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6 shows that the utilization level of medical resources significantly and positively affects both subjective and objective health capital within the sample, which conforms to theoretical expectations. It can be seen that although both the monthly outpatient visits and the visits to primary medical institutions are indicators for measuring the utilization of medical resources, they have opposite impacts on health capital. This reflects the actual differences under China’s tiered medical system. From the perspective of monthly outpatient visits, this indicator reflects the overall frequency of outpatient medical visits, including repeated visits, ineffective visits, or multiple hospital trips due to a shortage of medical resources. High outpatient visits often indicate that middle-aged and elderly people have high medical costs and waste time, and expose themselves to health risks due to cross-infection or excessive medical treatment. From the perspective of visits to primary medical institutions, this indicator reflects the reasonable medical behavior under the effective implementation of the tiered medical system. Primary medical institutions (such as community health service centers) usually provide more convenient, economical, and continuous health management services, such as chronic disease management, health consultation, and preventive health care. More visits to primary medical institutions reflect a more efficient and reasonable utilization of medical resources, which is conducive to early intervention and reducing the occurrence of serious diseases, thereby enhancing health capital. These two aspects reveal the dual impact of the level of medical resource utilization on health capital: an increase in the level of medical resource utilization can improve the self-assessed health status and health quality indicators of middle-aged and elderly households. Following Jiang (2022), who analyzed the mediating effect, these results suggest that the utilization level of medical resources can increase health capital, subsequently influencing financial asset-related decision-making behavior among middle-aged and elderly households; thus, H2 and H3 are confirmed.

Heterogeneity analysis

Income level

Keynesian theory of money demand indicates that transaction motivation makes residents more inclined to hold assets with high liquidity, such as cash and delivery time deposits, whereas precautionary motivation makes residents more inclined to hold low-risk assets, such as bank savings. As a key factor influencing transaction motivation and precautionary motivation, income plays an indispensable role in household financial asset decisions. Grinblatt et al. (2011) noted that if families lack the necessary physical capital, they may find it difficult to participate in risky financial markets.

This study is based on the research of Shao and Chen (2024), in which the sample is categorized into two groups according to median annual household income. In this study, the influences of the utilization level of medical resources and health capital on financial asset decisions are examined. As indicated in columns (1) to (4) of Table 7, health capital imposes a significant and positive effect on participation in holding risky assets and the ratio of such assets for the group with an income above the median. However, health capital does not significantly influence households with an income below the median. Compared with high-income households, low-income households exhibit lower risk resistance capabilities. Even if family members possess favorable health capital that can alleviate economic burdens, this will not affect their risk preferences, as they lack surplus wealth to participate in risky financial markets.

With respect to the utilization level of medical resources, the numbers of monthly outpatient visits, visits to primary healthcare institutions, and visits to large hospital facilities all significantly influence the degree of participation in holding risky assets and the ratio of such assets for the group with an income above the median. However, the overall utilization level of medical resources does not significantly affect the group with income below the median; only the number of outpatient visits per month and the level of primary healthcare institutions will have an impact on the proportion of risky assets in households below the median. This difference results from higher-income households already exhibiting higher risk preferences, more diverse income structures, and an awareness of diversified financial assets. Further enhancement in family medical resource utilization behavior—such as reducing the number of outpatient visits or transferring outpatient consultations from large hospitals to primary healthcare institutions—may result in decreased household medical expenses and savings accumulation. This could prompt households to continuously optimize their financial asset structure to achieve balanced family asset allocation and wealth preservation and appreciation.

Urban and rural regions

Owing to the enduring dichotomy between urban and rural regions in China, substantial differences exist in financial market development across these regions. Furthermore, compared with their urban counterparts, rural inhabitants face relative disadvantages in accessing information channels and capabilities. Despite ongoing efforts for urbanization and inclusive finance initiatives that aim to resolve the segmentation of financial markets between these two areas, factors such as the household registration (hukou) system continue to impact households’ decision-making processes, resulting in heightened risk aversion within rural communities (Fan and Yu, 2022). In the future, exploration of heterogeneous impacts through a lens focused on household registration differences is needed. Building upon the research of Li et al. (2024), we divide the overall sample into distinct groups comprising both urban families and their rural counterparts based on hukou distinctions, thus facilitating an examination of potential differences between these two demographic segments.

Columns (5) to (8) of Table 7 indicate that health capital exerts a significant and positive influence solely on participation in holding risky financial assets among individuals with an urban hukou, whereas its impact remains statistically nonsignificant among those with a rural hukou. One plausible explanation is that, owing to slow advancements in household registration reform, rural inhabitants continue to experience heightened risks associated with retirement, occupation, and housing, thus constraining the favorable role of increased health capital in their decision-making behavior concerning financial assets. In contrast to those in rural regions, households in urban regions additionally face substantial pressures related to the education of offspring and property ownership; this pressure may cause crowding-out effects on holding risky financial assets, consequently limiting the promoting effects of health capital exclusively at the level of participation in risky financial markets.

The utilization level of medical resources, encompassing the frequency of monthly outpatient consultations, visits to primary care facilities, and visits to major hospitals, substantially influences urban residents’ participation in holding risky financial assets and their allocation of such assets. It also significantly impacts the proportion of risky assets held by rural households. This phenomenon can be partly attributed to the notable differences in the accessibility and quality of resources, such as geriatric care facilities or medical services, between rural areas and urban centers. Thus, increasing the utilization level of medical resources holds greater marginal utility for increasing household wealth among urban residents because of the greater reduction in time and material costs resulting from improved medical resource utilization. Consequently, this incentivizes urban residents to allocate their financial assets effectively.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

In this study, CHARLS data from 2015 and 2018 are adopted as the research sample to examine the impact, mechanisms, and heterogeneous effects of the utilization level of medical resources on financial asset allocation behavior among middle-aged and elderly households from a health capital perspective. The key findings are as follows: first, an increased utilization level of medical resources, as demonstrated by a reduced number of outpatient visits and a shift in outpatient consultation pressure toward primary medical institutions, significantly increases the probability of middle-aged and elderly households participating in risky financial markets and increases their holding ratio of risky assets. Second, overall, health capital, as indicated by self-assessed health status and health quality indicators, positively influences financial asset allocation among middle-aged and elderly households while mediating the relationship between the utilization level of medical resources and financial asset allocation. Third, differences in income level and household registration result in heterogeneous utilization levels of medical resources and health capital impacts. For high income and urban households, the favorable utilization level of medical resources and notable health capital encourage increased financial asset allocation. However, this impact is smaller for middle- and low-income and rural households. The research conclusions have several policy implications:

First, the reduction in outpatient visits and the increase in visits to primary care services can alleviate the medical burden on middle-aged and elderly households and reduce the uncertainty of future large medical expenditures. They can also play a guiding and optimizing role in the financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households. Therefore, the focus of medical resource investment should shift from “treatment” to “prevention”, and efforts should be made to achieve the followins: vigorously promote the incremental reform of medical resources; solve the structural shortage of basic medical services in different regions; achieve the integration of a high-quality medical talent team centered around primary medical institutions; incorporate more commonly used drugs and treatment items for chronic disease management into the reimbursement directory of primary medical insurance; fully meet the medical needs of middle-aged and elderly households; continuously improve the accessibility of community and basic health service institutions; play the role of “gatekeepers”; and promote the first-visit system at the primary level, further providing favorable conditions for middle-aged and elderly households to invest in risky financial assets.

Second, the reduction in outpatient visits and the increase in visits to primary healthcare services can further enhance the health capital level of middle-aged and elderly households, providing a solid guarantee for the allocation of risky financial assets. To better leverage the mechanism of health capital, effectively converting health capital into financial capital, financial institutions should be encouraged to develop financial products and planning services linked to healthy behaviors. For instance, consistent with ensuring data security and privacy, a “health credit” system could be established. Regular physical examinations and successful completion of chronic disease management at primary healthcare institutions could be regarded as positive information and included in the credit assessment. Financial services, such as more favorable subscription rates for funds, could be provided for creditworthy middle-aged and elderly households, motivating them to pay more attention to their own health and actively participate in the allocation of risky financial assets.

Third, due to the heterogeneity of financial investment behaviors among households of different income levels and in different regions, while continuing to ensure the utilization level and health capital of medical resources for high-income and urban middle-aged and elderly households, more diversified and personalized financial services and products should be provided. The design and development of financial products should be innovated, the types of financial products available to this group of middle-aged and elderly families should be increased, the risk control of financial products should be strengthened, and relevant institutional guarantees should be provided. For low-income and rural middle-aged and elderly households that have not significantly benefited from the utilization of medical resources and health capital, primary medical care should be further strengthened, the coverage of medical resources for such household should be expanded, their health conditions should be improved, the medical burden should be reduced, the rational layout of medical resources should be prioritized, and the attractiveness of risky financial market investment for rural and low-income families should be comprehensively considered in the future.

Finally, this study also has certain limitations. First, in the 2020 CHARLS data, due to the lack of relevant information on the financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households and restrictions on data availability, it was not possible to incorporate the latest dataset for analysis; this may have resulted in a certain time lag, preventing it from reflecting many changes after the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, more comprehensive and timely data can be further explored to more accurately grasp the dynamic trends of medical resource utilization and financial asset allocation of middle-aged and elderly households. Second, because the CHARLS data were cleaned, mixed cross-sectional data, their effectiveness for other countries and their external generalizability still need to be verified. In the future, coherent panel data from China and other countries could be selected to reverify the relevant conclusions from this study. Third, the level of medical resource utilization is dynamic and complex, and the influencing factors of family financial asset allocation have multidimensional characteristics. Due to the limitations of the CHARLS data, there may be certain deviations in the measurement of core explanatory variables, the selection of instrumental variables and control variables. In the future, a broader perspective could be adopted to explore the overall impact of medical resource utilization on the financial asset decision-making of middle-aged and elderly households.

Data availability

Original data for this study are available in the CHARLS: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/. We are unable to share this data in a public forum as we have not been granted the right to do so. Any questions about the data used in this paper can be directed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Source: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/

Regarding the identification of risky financial assets, international scholars mostly refer to stocks and funds. However, Chinese scholars have included loans in the category of risky assets. The reason for this is as follows: First, based on China’s actual circumstances, personal loans have a certain interest rate and high risk. Therefore, including loans in the category of risky assets is somewhat reasonable (Lei and Zhou, 2010). Second, the data of this paper are middle-aged and elderly people aged 45 and above. The proportion of individuals investing in stocks and funds in the sample is relatively small. Using the generalized category of risky financial assets (including loans) can avoid generating large errors in the regression results (Cai et al., 2023). The original variables of CHARLS are HC040_W3 and HC041_W3.

For example, if one MOB is 2, PAC is 2, SAC is 2, and CPX is 11, then the health quality indicator is W = 1 + (−0.062) + (-0.060) + (−0.061) + (−0.257) = 0.616.

This study takes “utilization level of medical resources” as the dependent variable and “financial asset allocation” as the independent variable for the regression analysis. No significant impact was found, so it can be concluded that there is no significant reverse causal relationship.

Due to space limitations, the regression results are not presented.

Constructing a depression index with 10 questions, including two positive questions, namely, “I am hopeful about the future” and “I am happy”; 8 negative questions, namely, “I am troubled by some trivial matters”, “I have difficulty concentrating when doing things”, “I feel depressed”, “I find it very difficult to do anything”, “I am afraid”, “I have poor sleep”, “I feel lonely”, and “I feel that I cannot continue my life”. The answers include 4 options: “Rarely or never, not much, sometimes or half of the time and most of the time”. The positive questions are reversed and assigned values of 4, 3, 2, and 1, while the negative questions are assigned values of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and the total score is calculated. The lower the score, the lower the degree of depression; that is, the higher the health capital.

References

Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2023) When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Q J Econ 138(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjac038

Bialowolski P, Cwynar A, Weziak-Bialowolska D (2022) The role of financial literacy for financial resilience in middle-age and older adulthood. Int J Bank Mark 40(7):1718–1748. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2021-0453

Brunetti M, Giarda E, Torricelli C (2016) Is financial fragility a matter of illiquidity? An appraisal for Italian households. Rev Income Wealth 62(4):628–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12189

Bu T, Ma R, Wang YH, Wang XY, Tang DS, Deng LY (2024) Measurement on health capital of workforce: evidence from China. Soc Indic Res 174(2):569–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03403-x

Cai HB, Han JR, Song JQ (2023) Childhood influences of risk asset investment-an empirical analysis based on CHARLS database. J Hunan Univ 37(1):40–49

Chatterji S, Byles J, Cutler D, Seeman T, Verdes E (2015) Health, functioning, and disability in older adults—present status and future implications. Lancet 385(9967):563–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61462-8

Chen WM, Zhang Q (2024) The impact of the development of primary medical services on the health of the elderly in China. Popul J 46(2):93–107

Cheng TC, Kim S, Petrie D (2024) Health shocks, health and labor market dynamics, and the socioeconomic-health gradient in older Singaporeans. Soc Sci Med 348:116796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.116796

Coile C, Milligan K (2009) How household portfolios evolve after retirement: the effect of aging and health shocks. Rev Income Wealth 55(2):226–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2009.00320.x

Davies B, Schramme T (2025) Health capital and its significance for Health Justice. Public Health Ethics 18(1):phaf001. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phaf001

Edwards RD (2010) Optimal portfolio choice when utility depends on health. Int J Econ Theory 6(2):205–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7363.2010.00131.x

Fan JX, Yu Z (2022) Prevalence and risk factors of consumer financial fraud in China. J Fam Econ issues 43(2):384–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09793-1

Gan L, Lu XM, Wang X, Zhou RX, Li ZH, Wang F, Lin C, Chen S, Zhang Y, Cheng ZY, Wu YL (2020) The changing trend of China’s household wealth under the shocks of COVID-19. J Mod Financ 25(10):3–8+34

Gao Y, Yang Y, Lu J, Chen C, Liang X (2025) Does digital economy development enhance Chinese residents’ health? Impact and mechanism. BMC Public Health 25(1):1154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22325-y

Gomes F, Haliassos M, Ramadorai T (2021) Household finance. J Econ Lit 59(3):919–1000. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20201461

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M, Linnainmaa J (2011) IQ and stock market participation. J Financ 66(6):2121–2164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01701.x

Grossman M (1972) On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health. J Political Econ 80:223–255

Grossman M (2017) On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. In Determinants of health. Columbia University Press

Guo TJ, Tong Y, Yu YZ (2025) The influence of government health investment on economic resilience: a perspective from health human capital. Int Rev Econ Financ 99:104050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2025.104050

Hangoma P, Aakvik A, Robberstad B (2018) Health shocks and household welfare in Zambia: an assessment of changing risk. J Int Dev 30(5):790–817. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3337