Abstract

The unprecedented dual declaration of Mpox as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in 2022 and 2024 by the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the persistent threat of infectious diseases in the post-COVID era. With over 100,000 confirmed cases across 122 countries and an urgent demand for millions of vaccine doses, particularly in Africa, global attention has rightly focused on robust response and preparedness strategies, including enhancing diagnostics and developing medical countermeasures. Amidst this medical urgency, the profound influence of social, mental, and behavioral (SMB) factors, a crucial dimension of outbreak management, is frequently overlooked. This article addresses this critical gap by synthesizing current literature and presenting a structured, people-centric framework for Mpox countermeasures. It is based on a comprehensive search of academic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar) and key policy documents from the WHO, CDC, and Lancet Commissions. We identify that existing evidence on the relationship between Mpox and social determinants of health, mental well-being, and behavioral responses is often limited or conflicting. Issues such as stigma, discrimination, and misinformation lead to social exclusion and adverse mental and behavioral changes, which in turn impede prevention efforts, discourage testing, and delay access to timely care, thereby undermining public health initiatives. To address these barriers, which are compounded by the perceived intangibility of social interventions and economic sanctions, we advocate for shifting from a disease-centric to a people-centric approach. We propose the application of implementation frameworks rooted in established social science theories and introduce a Theory of Change model to rigorously measure the impact of these interventions. Such a tailored, contextual, and measurable shift is essential in achieving shared success, building enduring societal resilience, and achieving a resilience dividend alongside technological advancements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mpox (formerly Monkeypox), a zoonotic viral disease, has been declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in August 2024 (Adepoju 2024). This is the second time that Mpox has been designated a PHEIC, following its first declaration in 2022 (Eurosurveillance Editorial Team 2024). Such a dual declaration for a single pathogen is the first case, which signifies its unique and persistent threat to global health, highlighting the need for a sustained, robust international response.

The current PHEIC declaration is an outcome of the outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and its subsequent spread to neighboring countries. According to the WHO’s latest global Mpox rapid risk assessment in August 2024, the risk level is categorized as high in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and neighboring countries. In contrast, the risk level is moderate globally, and this is also the case in Nigeria and other countries in West, Central, and East Africa. As of November 17, 2024, 20 African countries have reported over 12,00 confirmed cases. Globally, there are over 100,000 cases across 122 countries, including 115 nations where Mpox is a new entrant. This has resulted in urgent global attention on robust response and preparedness strategies, which primarily centered around enhancing diagnostics and providing vaccines, with an urgent demand for millions of vaccine doses, particularly in Africa. However, current treatment options remain limited, in the absence of specific treatments for Mpox and the waning population immunity due to the discontinuation of smallpox vaccination (which offered approximately 85% protection against Mpox) (Christodoulidou and Mabbott 2023).

Amidst this medical urgency, a crucial dimension of outbreak management is often overlooked, i.e., the profound influence of social, mental, and behavioral (SMB) factors. Existing evidence about Mpox’s connection to social determinants of health (SDH), mental well-being, and behavioral responses is often limited or conflicting, which hampers a thorough understanding of how diverse individuals and communities are affected. Issues like stigma, discrimination, and the spread of misinformation can severely hinder prevention efforts, discourage testing, and delay access to timely care. Unlike tangible medical countermeasures, these essential, yet often intangible, resources required for social support and behavioral health are frequently deprioritized in global health discussions.

In view this article explores the critical role of SMB factors in Mpox management. We argue that the frequent neglect of SMB factors undermines the effectiveness of public health countermeasures. Drawing on a evidences collected from limited regional studies and actionable agendas, we aim to (1) empirically demonstrate the impact of SMB factors on Mpox outcomes, (2) leverage established social science theories to provide a structured understanding of these dynamics, and (3) propose concrete, measurable policy and programmatic recommendations aligned with a people-centric approach and the ‘Adapt, Protect, Connect’ framework for pandemic preparedness.

We positioned Mpox as a case study, given its frequent re-emergence as a significant global health security risk. This analysis highlights lessons transferable to future infectious disease challenges in the post-COVID era, emphasizing that biomedical solutions alone are insufficient for holistic and resilient pandemic preparedness.

Method

This article adopted a narrative methodology to synthesize the current literature on SMB considerations in the management of the Mpox outbreak. The primary focus is on how these factors influence the effectiveness of public health countermeasures, including vaccination campaigns, prevention strategies, and timely access to care. Furthermore, to inform the global health threats posed by Mpox, transmission and existing medical countermeasures were discussed, providing a comprehensive 360-degree coverage of the subject to offer collective insights for both biomedical and social sectors.

To gather relevant literature, we searched across three key academic databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords, including but not limited to: ‘mpox,’ ‘monkeypox,’ ‘social determinants of health,’ ‘stigma,’ ‘misinformation,’ ‘vaccine,’ ‘vaccination hesitancy,’ ‘community engagement,’ ‘mental health’, ‘public health policy,’ ‘social theory’, ‘theory of change’, and ‘behavioral interventions.’ While the ‘English’ language literature published since the 2022 global outbreak was prioritized, foundational articles on related public health crises (such as HIV and Ebola) were also considered for historical context and comparative analysis. This was essential to inform the cross-sectoral experiences in managing different infectious diseases and to discuss the current limitations in Mpox management from an SMB lens.

In addition to peer-reviewed articles, we also consulted non-indexed, policy-relevant documents. These included guidelines and reports from organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and official government publications and reports from non-governmental organizations.

The selection of a narrative style offered flexibility, allowing for the development of conceptual models and the integration of theoretical frameworks. These were crucial for addressing multifaceted public health challenges like Mpox. Through this, the article’s core contribution is twofold. First, it moves beyond a mere observation of the neglect of SMB factors in infectious disease management by presenting a structured, people-centric framework for their systematic integration. By using Mpox as a strategic case study, we empirically demonstrate how the failure to address issues such as stigma, misinformation, and SDH directly undermines the effectiveness of biomedical countermeasures. Second, instead of simply critiquing this gap, we offer a solution-oriented methodology. We leverage robust theoretical frameworks from the social sciences, such as the Health Belief Model and the Social Ecological Model, to provide a structured understanding of these dynamics. We then translate these insights into concrete, measurable policy and programmatic recommendations that are explicitly aligned with globally recognized pandemic preparedness strategies, such as the ‘Adapt, Protect, Connect’ framework. It provides a practical blueprint for policymakers to move beyond a disease-centric paradigm toward a more holistic, equitable, and resilient model of public health.

About Mpox: Virology and clinical manifestations

Mpox, a zoonotic disease caused by the Monkeypox virus (MPXV), was first identified in macaque primates in 1958. MPXV is a large, double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family. Historically, Mpox was endemic to the rainforests of Central and West Africa, primarily transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals or the consumption of contaminated meat. However, the exact natural reservoir of MPXV remains undetermined. The first documented human case of Mpox occurred in 1970 in a 9-month-old boy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since the 1980s, global transmission of Mpox has been reported.

To date, three clades of the Mpox virus have been identified, namely Clade I, IIa, and IIb. Although genetic evidence supporting their pathogenicity is evolving, a recent study found distinct variations among these clades. Significant variations resulted from gaps in the genomic structure, frameshift mutations, in-frame nonsense mutations, and altered amino acid tandem repeats (Desingu et al. 2024). Clade IIb viruses, in particular, show specific genetic differences in genes such as C11L, D18L, B1R, B7R, B14R, D4L, IIb-MV27, B16R, and uncharacterized genes like IIb-MV23 and IIb-MV29. These variations, including frameshift mutations and amino acid changes, may contribute to the increased transmissibility and altered virulence of Clade IIb. (Americo et al. 2023).

Mpox shares some similarities with smallpox in its presentation, but generally has a lower case fatality rate and less efficient person-to-person transmission. The virus enters the body through the respiratory or skin routes. Infected antigen-presenting cells migrate to nearby lymph nodes, thereby facilitating the dissemination of the virus through the lymphatic system. While the exact mechanism of viral migration from the initial infection site to lymph nodes is still debated, it can subsequently target other major organs (Lum et al. 2022). A hallmark feature of Mpox is the development of painful skin lesions that progress through four distinct stages (macules, papules, vesicles, and pustules) over 2–4 weeks. These skin lesions are often preceded or accompanied by prodromal symptoms, such as fever (62–72%), swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy, 56–86%), muscle aches (myalgias, 31–55%), general malaise (23–57%), and headache (25–55%). The 2022 global outbreak, primarily caused by clade IIb MPXV, has seen an increase in proctitis (14–36%) and pharyngitis (13–36%), which can sometimes be the initial symptoms of Mpox. Additionally, the outbreak has presented with atypical symptoms like the absence of prodromal symptoms and genital lesions, suggesting sexual transmission. While most infections have been linked to close and intimate contact with symptomatic individuals, particularly male-to-male sexual contact, other modes of transmission, such as heterosexual contact, skin-to-skin contact with caregivers, needle-stick injuries, and occupational exposure, have also been reported (Karan et al. 2023; Acharya et al. 2024).

Medical countermeasures

For the re-emergence of Mpox, global emphasis is directed toward enhancing diagnostics and developing effective medical countermeasures, including antivirals and vaccines. However, the current treatment options for Mpox are limited to two FDA-approved (JYNNEOS and ACAM2000) and one Japanese vaccine (LC16m8). JYNNEOS, a Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) vaccine, has demonstrated significant efficacy in preventing Mpox. It can lower the risk of Mpox disease by 62% to 85% in unvaccinated individuals. Furthermore, for individuals already exposed to Mpox, MVA-BN can reduce the risk of disease by 20% (Grabenstein and Hacker 2024). WHO has recently prequalified it. Likewise, LC16m8, an attenuated smallpox vaccine developed and manufactured by KM Biologics in Japan, has been placed under the WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) for use against Mpox. Another FDA-approved vaccine, ACAM2000, a live, replicating vaccinia virus vaccine, is effective but carries a higher risk of serious complications, especially for immunocompromised individuals and their close contacts. Similarly, two smallpox antivirals, tecovirimat and brincidofovir, have been evaluated for their potential to mitigate Mpox symptoms and complications. However, recent findings from the PALM007 trial conducted by the USA’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) have shown that tecovirimat did not significantly reduce the duration of Mpox lesions in children and adults with clade I Mpox (NIAD 2024).

While several promising vaccine candidates are currently in development, their market entry will take time, even with expedited regulatory processes like emergency use authorization. Meanwhile, the demand for existing vaccines has surged, particularly in Africa. The immediate need reaches 10 million doses, far surpassing the available supply of 2–3 million doses (Kuppalli et al. 2024). In this, global solidarity is evident, with the U.S. donating 50,000 vaccines to Africa, the establishment of the Access and Allocation Mechanism (AAM) for Mpox pledging over 3.6 million vaccine doses, Japan pledging 3 million doses of the LC16 vaccine, and the Global Fund pledging $9.5 million for Africa (Center for outbreak response innovation, JHU 2024; WHO 2024).

However, scaling up the existing vaccine arsenal and ensuring equitable distribution remains a significant challenge (Health Policy Watch 2022). This potential demand-supply gap has adverse consequences for public health, impacting SMB health outcomes (Malta et al. 2022).

Mpox and Social Determinants of Health (SDH)

The social determinants of health (SDH) refer to the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. These include socioeconomic conditions, such as income, race, and education, as well as broader societal factors like social policies and political systems (Braveman and Gottlieb 2014). SDH significantly influences health inequities, the unfair and avoidable differences in health status observed within and between populations.

The significant impact of SDH on health outcomes has been well-studied in some diseases. A large-scale longitudinal study has demonstrated the influence of factors such as geographic location, socioeconomic status, and living conditions on AIDS-related outcomes in LMICs (Lua et al. 2023). For instance, individuals from disadvantaged socioeconomic groups, including the poor, Black populations, the illiterate, and those with inadequate housing, are at a higher risk of acquiring HIV and experiencing poorer outcomes. Likewise, TB remains a significant social disease, closely linked to poverty (Bhargava et al. 2021). Factors such as poor health perceptions, high healthcare costs, and limited access to healthcare facilities hinder TB patients from seeking timely care.

Additionally, socioeconomic disparities, poor living conditions, malnutrition, substance abuse, comorbidities, and incarceration increase the risk of TB infection and disease progression. Mere attention to SDH positively influenced TB by reducing cases up to 84.3% (Carter et al. 2018). The same has been the finding for COVID-19, as it has disproportionately affected societies. Many SDH, including poverty, exposure to environmental pollutants, and racial/ethnic discrimination, have significantly influenced individual susceptibility and community-level responses to the pandemic (Abrams and Szefler 2020).

While Mpox has been circulating since the late 1980s, with periodic outbreaks in Africa, the correlation between SDH and Mpox has been relatively understudied. An argument for such limited attention is the significant health disparity between wealthy nations and the rest of the world, where rich nations were less concerned until the recent global spread (Malta et al. 2022).

Emerging evidence suggests that SDH can significantly influence the transmission, prevention behaviors, and treatment outcomes of Mpox. Several factors contribute to this disparity, including transmission within specific social and sexual networks, limited access to quality healthcare due to stigma and fear, increased risk for individuals with underlying health conditions, and systemic barriers to accessing essential SDH such as affordable housing, nutritious food, and healthcare (Table 1).

Mpox has disproportionately impacted marginalized communities and people of color (Leonard et al. 2023). SDH influenced transmission dynamics among MSM groups who are particularly vulnerable due to overlapping sexual networks and existing health disparities (Paparini et al. 2024; Omame et al. 2025). Likewise, factors such as minority status, unemployment, and housing instability have been linked to higher rates of Mpox infection. For instance, Black men and those living in high-density housing areas are more likely to test positive for Mpox, highlighting the role of social vulnerability in disease transmission (Leonard et al. 2023).

A recent US-based study based on the 2022 Mpox outbreak found that social determinants such as education, race/ethnicity, and discrimination impact exposure to Mpox information and subsequent health anxiety (Otmar and Merolla 2024). A strong correlation was established between increased exposure to Mpox-related messages and higher anxiety levels in the initial phase of the outbreak. Similarly, in another study, racial and ethnic disparities were notable, with Black and Hispanic males experiencing significantly higher incidence rates compared to White males (relative risk of 6.9 and 4.1, respectively, at the peak of the outbreak) (Kota et al. 2023). This disparity persisted despite vaccination rates being somewhat higher among racial and ethnic minority groups, indicating that increased vaccination alone was insufficient to offset the disproportionate incidence and highlighting the more profound, systemic influence of SDH. Likewise, another study from Bangladesh revealed a strong association between sociodemographic profiles and the level of education on Mpox vaccine perception and vaccination intention (Islam et al. 2023b).

These are not merely individual challenges but reflect broader societal failures that perpetuate health inequities. This is reflected in treatment outcomes, where disparities in healthcare access, often driven by socioeconomic factors, have led to delayed diagnoses and treatments. This exacerbated the disease burden in vulnerable populations (Hogben and Leichliter 2008; Leonard et al. 2023). Likewise, the presence of HIV in the MSM community complicates Mpox treatment outcomes. HIV increases susceptibility to Mpox, and the co-management of these diseases requires integrated healthcare approaches that address both medical and social needs (Gopalappa and Khoshegbhal 2023; Omame et al. 2025).

In view, the concept of ‘minority stress theory’ provides a valuable framework for understanding these dynamics, explaining how chronic exposure to discrimination and social marginalization impacts health anxiety and the effectiveness of health communication within marginalized communities (Parmenter and Winter 2025). This theoretical underpinning helps explain observed disparities in information processing and anxiety, underscoring that addressing SDH is not solely an ethical consideration but a pragmatic necessity for effective disease control and prevention. Ignoring these root causes means that public health interventions, even well-intentioned ones like vaccine campaigns, will inherently fail to reach or fully protect the most vulnerable populations, thereby allowing for sustained transmission and perpetuating outbreaks. This strengthens the argument for people-centric approaches as a fundamental requirement for achieving shared public health success.

Mental and Behavioral issues in vaccinations

Behavior and mental health are intricately linked, influencing each other in complex ways. This relationship is bidirectional, acts as a continuous feedback loop, and involves mutual exchange. For Mpox, this complex interplay is multifaceted (Table 2). It requires a crucial understanding for developing effective interventions and promoting overall well-being, thereby shaping the trajectories of outbreaks. COVID-19 is an example of the recent past that showed how mental health prolonged the pandemic fear. A study by Yang et al. (2024) among Indian adults revealed strong associations between various pandemic-related worries, including financial stress, and increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (Yang et al. 2024). Financial stress emerged as the most prominent factor contributing to these mental health issues.

Regardless of the disease, the interplay between mental health and behavior can significantly influence vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. Mental health factors, such as motivation, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation, can shape vaccine decision-making. Conversely, behavioral factors, like anxiety and stress related to vaccine hesitancy, can negatively impact mental health and reinforce negative attitudes toward vaccines. This intricate relationship has been observed in the context of Mpox as well. Older men who have sex with men (MSM), those who perceived a higher risk of Mpox infection, and those who received Mpox information from healthcare providers were more likely to get vaccinated (Huang et al. 2024). Conversely, MSM with higher levels of depression were less likely to be vaccinated. Similar trends were observed in a study conducted in Ghana (Ghazy et al. 2023). Older individuals were more likely to accept the Mpox vaccine than younger individuals, and males were more likely to accept the vaccine than females. However, a study conducted on Chinese MSM with an average age of 24 revealed a positive intention to receive the Mpox vaccine, ranging from 66.2% to 88.4% across various scenarios (Luo et al. 2024). Factors positively influencing vaccination intention included knowledge of Mpox, perceived susceptibility to infection, perceived disease severity, emotional distress, perceived benefits of vaccination, self-efficacy in getting vaccinated, and having one male sexual partner. These findings suggest that age may not be the sole determinant of vaccine acceptance in this demographic.

Stigma is another factor that contributes to vaccine hesitancy and challenges in vaccine distribution, particularly among marginalized groups. In the US, Black sexual minority men reported concerns about Mpox vaccine availability and hesitancy, which were linked to stigma and a sense of neglect by the health system (Turpin et al. 2023). As such, studies from Brazil and the UK established that efforts to reduce stigma are crucial for improving vaccination uptake and ensuring comprehensive sexual health screenings (Alyafei and Easton-Carr 2025).

Social media platforms can significantly influence mental health, which in turn shapes behavior. A study examining tweets related to Mpox found that social media discourse can contribute to stigmatization and concerns about vaccine safety, which can ultimately impact decision-making regarding vaccination (Rajkhowa et al. 2023). Sharply contrasting evidence was presented by Garcia-Iglesias et al. 2023 who highlighted the positive role of social media in the context of the 2022–2023 Mpox outbreak. The platform played a crucial role in disseminating accurate information, challenging stigma, and promoting advocacy and collaboration. This evidence indicates that social media can have both positive and negative influences on mental health. Importantly, cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that social platforms can contribute to the development of social capital, which can influence vaccination decisions and provide support against stigma, potentially creating subcultures that may challenge societal norms (Reich 2020). Conversely, studies involving gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have indicated that social capital can facilitate engagement in HIV prevention by increasing awareness and uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (Zarwell et al. 2019). While specific studies on the impact of social capital on Mpox transmission and vaccination are limited, it is reasonable to assume that some of these principles remain relevant. To improve Mpox management, it is crucial to invest in research to better understand the role of social capital in shaping behaviors and attitudes related to the disease. However, it could be ascertained that vaccine hesitancy and the ability to sustain behavioral changes are not simply due to a lack of information. They are complex phenomena deeply influenced by a multitude of interacting factors. These include individual beliefs, social norms, self-efficacy, and the dynamics of how innovations diffuse through social networks (Alyafei and Easton-Carr 2025). For example, even with accurate information, high perceived barriers (e.g., fear of stigma) or discouraging social norms can lead to low uptake (Linares-Navarro et al. 2025). Public health campaigns must therefore move beyond a simplistic ‘information deficit model’ to address the psychological, social, and structural determinants of behavior. This requires designing sophisticated interventions that not only inform but also enhance self-efficacy, leverage positive social norms, actively reduce perceived barriers, and tailor strategies to different community adoption stages.

Other mental and behavioral issues

The impact of Mpox on mental health and behavior transcends traditional discussions on vaccination. This stems from Mpox’s association with sexual transmission in LGBTQ+ communities, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM) (Acharya et al. 2024). Historically, LGBTQ+ individuals face disproportionately higher rates of mental health issues compared to heterosexual and cisgender populations. It results from the widespread stigma and discrimination associated with these communities that significantly impact Mpox prevention efforts.(Acharya et al. 2024). The immediate impact is negative health-seeking behavior that deters individuals from seeking health services, leads to underreporting of cases, and exacerbates existing health disparities. In the UK, stigma was reported to be a significant barrier to care-seeking, with feelings of shame being a common deterrent (Paterson et al. 2025). In Brazil, a high level of Mpox awareness and willingness to vaccinate was observed, yet stigma remained a barrier to accessing health services (Torres et al. 2023).

Furthermore, public health messaging that inadvertently stigmatizes certain groups undermines trust in health authorities and reduces the effectiveness of prevention campaigns. In the UK, the LGBTQ+ community and local health clinics played a crucial role in countering stigma and promoting health-seeking behavior, despite challenges from central public health authorities (Biesty et al. 2024). In the Western Pacific region, stigma against the gay community was identified as a more significant issue than the spread of the Mpox virus itself, highlighting the need for sensitive and inclusive public health strategies (Zhu and Pan 2024).

Collectively, these impact social behaviors among affected populations. For instance, gay, bisexual, and MSM communities in the U.S. reported changes in sexual behaviors and social activities. This was to mitigate exposure to the virus, influenced by perceived and experienced stigma (Hong, 2023). Disgust and stigma towards Mpox patients can also prevent people from adopting preventive behaviors, as seen in a study examining the role of disgust in influencing prevention intentions (Cao and Zheng 2025).

Societal discrimination often leads to increased psychological distress and mental health disorders, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts (Alnaher et al. 2024). For MSM individuals, conflicts between social expectations and personal preferences can lead to psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and risky sexual behaviors. Fear of social exclusion hinders health-seeking behaviors, increasing the risk of STIs (Gonzales and Henning-Smith 2017). These challenges are pronounced in rural areas due to limited access to services, discrimination, and societal stigma (Maria et al. 2024). These factors create barriers to accessing care, exacerbating mental health inequities and highlighting the need for targeted interventions.

Given the existing burden, it is predictable that the contradiction of Mpox by individuals in these communities will have severe consequences (Keum et al. 2023). Studies have shown that individuals diagnosed with Mpox grapple with anxiety and depression due to the physical symptoms, social stigma, and uncertainty surrounding the disease (Jaleel et al. 2024). The highly contagious nature of Mpox and the recommended isolation periods can lead to feelings of loneliness and social isolation, further exacerbating mental health issues. The stigma associated with Mpox can lead to discrimination, bullying, and social exclusion, negatively impacting the mental health and well-being of affected individuals (Orsini et al. 2023). Evidence suggests that stigmatization has led to individuals concealing infections or symptoms, inadvertently contributing to the spread of the disease. In some cases, individuals with Mpox have even fled their countries, potentially exposing others to the virus without seeking necessary medical care (Sah et al. 2022).

While stigma and discrimination pose significant challenges to Mpox prevention, community-led initiatives and inclusive public health strategies have shown promise in mitigating these effects. The involvement of affected communities in designing and implementing health interventions like peer support initiatives and co-designing public health communications can enhance trust and improve health outcomes (El Dine et al. 2024; Paterson et al. 2025). For example, The LGBTQ+ community and local sexual health clinics have played a crucial role in countering stigma and supporting health-seeking behavior during the Mpox outbreak (Biesty et al. 2024). Likewise, community-led health promotion efforts have been effective in increasing trust and engagement among priority populations, inclusing GBMSM and ethnic minority groups (Biesty et al. 2024). These initiatives have included participatory workshops and targeted outreach efforts, which have helped to address misinformation and promote vaccine uptake. Recommendations for reducing stigma include ensuring equitable access to vaccines and treatments (Paterson et al. 2025).

However, addressing stigma requires a multifaceted approach that includes education, policy changes, and the promotion of social acceptance. Future research should focus on developing and validating tools to measure stigma and its impact on health behaviors, as well as exploring interventions that can effectively reduce stigma in diverse contexts.

All these mental health events significantly impact sexual behaviors. A survey conducted during that period revealed that nearly half (48%) of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) reduced their number of sexual partners (CDC 2023). Additionally, 50% reported engaging in fewer one-time encounters with partners met on dating apps or sex venues. However, these behavior changes may not be sustainable in the long term. There is a concern that as sexual practices return to pre-outbreak norms, Mpox could potentially spill over from high-risk networks to the broader population (Karan et al. 2023). This is evident from a community-based surveillance study that detected Mpox DNA (Clade IIb) in 1.3% of discarded condoms collected across 16 countries in the Global South (Wannigama et al. 2024). Notably, India and Pakistan exhibited the highest positivity rates. This provides empirical evidence of ongoing risk and highlights the challenge of maintaining long-term adherence to risk-reduction behaviors. This situation illustrates a paradox: initial behavioral shifts, often driven by acute fear, may not persist without sustained support and structural changes. Public health strategies must therefore move beyond immediate, crisis-driven messaging to build long-term resilience and foster sustainable behavior change, understanding the underlying psychological, social, and environmental factors that influence adherence over time.

Discussion

The 2024 global Mpox outbreak, especially by the Clade II virus, adds to the list of public health security threats. However, the recent emergence, which is linked to African endemicity and the 2022 outbreaks, reflects a gross underpreparedness of varying degrees among different nations. It requires introspection—exactly where the actions fall short and need more focus. With existing evidence presented here on Mpox and its relationship with SDH, mental and behavioral factors, it seems that somewhere, people-centric approaches are missing. Contrasting evidence and a lack of critical studies hinder our ability to fully understand how diverse individuals from different societies and sexual orientations may be affected. To address the complex dimensions of disease management Carter et al. highlighted the lack of formalization and consistent definition of ‘social sciences’ within One Health (OH) agendas. They further emphasized the ongoing debate surrounding the optimal integration of social sciences into the conceptualization, coordination, implementation, and evaluation of OH initiatives. The authors suggested entry routes for a much broader spectrum of social and behavioral sciences capabilities that will better assist OH in meeting its contemporary goals.

This highlights the fact that outbreaks reveal the complex nature of health systems, which are shaped by both global and local factors, resulting in multifaceted and interconnected solutions that extend beyond medical countermeasures. It requires equal prioritization of SMB factors, similar to existing approaches on diagnostics and medical countermeasures. Such an approach requires a more diverse range of stakeholders, including experts from social science disciplines, as well as public health experts and technology developers.

This raises a question about why SMB implementation is facing systemic barriers. Among these, we address three broader barriers. The first barrier is the perceived ‘intangibility’. Unlike a vaccine or a diagnostic test, which are tangible products with clear, measurable outputs, concepts such as trust-building, community engagement, or stigma reduction are complex processes that are difficult to quantify using traditional, immediate outcome-based metrics. This difficulty in measurement makes them ‘less appealing to policymakers and funders who often prioritize immediate and tangible results’. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle: underfunded SMB interventions struggle to demonstrate their full impact, which in turn reinforces the perception of their ‘intangibility’ and reduces future investment. This bias towards the tangible is a significant economic and political barrier, as funding mechanisms often favor quantifiable outcomes over complex, long-term social processes.

The second barrier results from ‘political determinants of health’ that have historically shaped health outcomes by influencing the distribution of resources and the implementation of health policies. This has been evident in the varying responses to health crises across different political systems (Dawes et al. 2022). While there is limited evidence of its impact on Mpox, a study from the USA found that political orientation and resource allocation were critical factors affecting vaccine distribution and coverage during the 2022–2023 mpox outbreak. States with Democratic political orientations and higher public health spending saw better vaccine coverage, highlighting the role of political decisions on health outcomes (Kang et al. 2024). Moreover, the discussion on political determinants intensifies. Strong evidence suggests that politically motivated economic sanctions by the USA or the EU have a profound impact on global health (Poddar and Rao 2025). From 1971 to 2021, these sanctions were linked to an estimated 564,258 deaths annually (95% CI 367,838–760,677), a figure higher than the annual number of battle-related casualties (106,000 deaths) (Health 2025). More importantly, these economic sanctions had direct effects on access to medical products, the provision of healthcare services, and civilian mental health, and indirectly affected health determinants such as food security and socioeconomic development. LMICs impacted most where adverse health effects of sanctions are most pronounced among vulnerable populations, including children, women (compared to men), and the most marginalized group. Given Mpox’s origin, prevalence, and distribution, it is reasonable to predict that these sanctions have a profound impact on Mpox transmission and management. Although more focused studies are required to quantify the full extent of the damage.

The third barrier is the result of the first two, where pandemics exacerbate existing economic difficulties, such as unemployment and financial stress, which in turn lead to widespread mental health problems and can trigger negative behaviors (Lu and Lin 2021). These negative behaviors include resistance to public health measures, panic buying, and substance abuse, creating a vicious feedback loop. Economic instability, whether pre-existing or pandemic-induced, exacerbates mental health issues and leads to behaviors that hinder effective outbreak control (Murphy et al. 2021). This, in turn, prolongs the crisis, further damaging the economy and deepening social inequalities.

Thus, it brings us to a final question: How can we bring a people-centric approach to the center by advancing the integration of broader social science dimensions in outbreak responses, including those for Mpox and pathogens of future outbreaks? We believe there is an urgent need to review the entire landscape of existing recommendations and categorize and prioritize them based on context for locational and target group-specific needs. This can provide a nuanced and holistic understanding of the situation, facilitating the construction of an operational roadmap in parallel with other preparedness and response efforts. Most importantly, it can avoid the risk of reinventing the wheel and instead provide options to move forward in a much more sensible manner.

Implementation frameworks

To move beyond problem identification towards systematic solutions, the explicit application of established behavioral and social science theories provides a powerful lens for understanding, predicting, and intervening on Mpox-related behaviors and outcomes. These frameworks can serve as actionable blueprints for systematically designing, implementing, and evaluating effective public health interventions.

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a psychological framework used to understand and predict health behaviors by focusing on individual beliefs about health conditions. The model’s constructs, including perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy, play a crucial role in shaping preventive behaviors and vaccine acceptance. For instance, public health campaigns can tailor messages to increase perceived susceptibility among specific risk groups or highlight the benefits of vaccination while actively addressing perceived barriers, such as concerns about side effects, access difficulties, or stigma. The HBM has been effectively utilized in various health contexts, including maternal antenatal care and COVID-19 vaccination, to predict and enhance preventive behaviors. It emphasizes the role of perceived threats and benefits in motivating health actions (Subedi et al. 2025). In the context of mpox, the model suggests that increasing perceived susceptibility and severity, while reducing perceived barriers, can enhance preventive behaviors and vaccine acceptance (Gao et al. 2025). As such, public health messaging should focus on these aspects to improve compliance with preventive measures (Walsh-Buhi et al. 2024).

A study conducted at the Cook County Jail in Illinois used the HBM to assess mpox knowledge and attitudes among residents and staff. It found that while there was a perceived susceptibility to mpox, there was uncertainty about the severity of the infection. This uncertainty, coupled with limited knowledge, acted as a barrier to preventive actions (Hassan et al. 2024). The study highlighted the importance of clear communication and education about mpox risks and vaccination options. It suggested that correctional facilities could enhance disease prevention by providing tailored messages and ensuring access to hygiene and disinfecting supplies.

HBM was also applied to address healthcare workers’ Vaccine Hesitancy. For example, in the Czech Republic, a study on healthcare workers (HCWs) revealed significant vaccine hesitancy towards mpox, with only 8.8% willing to receive the vaccine. The HBM constructs of perceived susceptibility and cues to action were critical in predicting vaccine acceptance (Riad et al. 2022). The study identified suboptimal levels of factual knowledge about mpox vaccines and treatments among HCWs, with digital news and social media being the primary information sources. This underscores the need for targeted educational campaigns to address misconceptions and improve vaccine uptake.

While the HBM provides a valuable framework for understanding health behaviors, it is essential to consider the broader social and cultural factors that influence individual perceptions and actions. For instance, the stigma associated with specific populations, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), can affect perceived susceptibility and barriers to preventive measures (Yang et al. 2023). Additionally, the effectiveness of interventions may vary across different settings and populations, highlighting the need for context-specific strategies.

This brings to the application of Social Cognitive Theory into the discussion. It incorportes individual factors (e.g., self-efficacy), behavioral factors, and environmental factors into the discussion (Islam et al. 2023a).. This theory is highly relevant for community-based interventions, demonstrating how they can leverage observational learning (e.g., peer role models), social support, and reinforcement to promote desired behaviors, such as vaccine uptake or safe sexual practices. The theory’s principles have been used to understand and influence health behaviors related to mpox, particularly in marginalized communities. SCT can help address this by using social representations and media to challenge negative stereotypes and promote positive health behaviors. By anchoring mpox to familiar cultural phenomena and using emotive language, health messages can become more relatable and impactful (Nerlich and Jaspal 2025). Moreover, SCT has been found to be helpful in creating a supportive environment that encourages individuals to adopt preventive measures and seek treatment (Schunk and DiBenedetto 2023). It was possible by engaging community networks and providing social support.

While SCT provides a robust framework for understanding and influencing health behaviors, it is not without limitations. The theory often overlooks non-cognitive processes and individual differences, which can affect the applicability of its principles across diverse populations. Additionally, the broad scope of SCT can make it challenging to apply comprehensively in specific contexts, such as mpox, where cultural and social nuances play a significant role (Myrick and Yang 2022).

Such challenges open the possibility for testing the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a psychological framework that has been widely applied to address health-related behaviors, particularly in sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The theory has been effectively used to design interventions aimed at changing health behaviors by targeting attitudes towards the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. For instance, a study covering 492 MSM revealed a high intent-to-vaccinate; however, only 48% received at least one vaccine dose (Jongen et al. 2024). As such, a high intent for vaccination among MSM does not necessarily lead to high vaccine uptake. Mpox risk perception emerged as a more critical factor in determining actual vaccination uptake than initial intent.

While promising, TBP may not fully account for impulsive behaviors or contextual factors that influence decision-making (Hohmann and Garza 2022). Additionally, the effectiveness of TPB-based interventions can vary across different cultural and demographic contexts. Therefore, it requires specific social and cultural contexts of the target population for Mpox management.

Existing policy-level discourse

Translating the understanding of SMB dynamics into actionable strategies requires concrete policy and programmatic recommendations, explicitly aligned with established global frameworks. The good news is that global momentum has already been initiated for a more balanced health system preparedness for outbreak responses. Incidentally, in the middle of the Mpox outbreak, the Global Pandemic Monitoring Board at the WHO came out with its 2024 Report. The report reworked and redefined the critical drivers of pandemic risk and provided a roadmap for strengthening defenses against pandemic (Global Preparedness Monitoring Board 2024). Along with technological, economic, and environmental factors, social aspects have emerged as a key driver in addressing the pandemic. This recognition has led to a transformative shift in approach, moving from the traditional ‘Prevent, Detect, Respond’ model to a more adaptive ‘Adapt, Protect, Connect’ framework. The ‘Adapt’ pillar emphasizes the need for agile planning and risk communication strategies that are continuously adapted to diverse local social contexts and the evolving information ecosystem. The ‘Protect’ pillar focuses on strengthening ‘social protection’ as a critical shield against pandemic risks. This involves advocating for social programs as safety nets, ensuring income protection, and addressing global inequities in social protection, particularly in low-income countries. Finally, the ‘Connect’ pillar advocates for ‘whole-of-society approaches’ and robust intersectoral efforts, particularly through the ‘One Health’ approach, which integrates human, animal, and environmental health with social protection and equity. This requires fostering strong connections between public and private sectors, academic institutions, and civil society organizations. This is exactly what we called for here: a more aligned, dynamic, and people-centric approach. To be more specific to current discussion, a structured, multi-term plan for integrating SMB interventions into the Mpox response, using the ‘Adapt, Protect, Connect’ framework is proposed here (Table 3) While such reports offer hope for a new era of outbreak response and more impactful outcomes, only time will tell how these recommendations will be integrated into national action plans.

To provide a more in-depth view of the growing discourse in SMB interventions, we also compared three critical documents: The Lancet Commission on Pandemic Preparedness (2022), the WHO Pandemic Agreement (2025), and the Lancet One Health Commission (2025) (Sachs et al. 2022; Winkler et al. 2025; WHO 2025a). A clear evolution is evident in how SMB interventions are considered in pandemic preparedness, yet significant gaps remain (Table 4). The Lancet Commission on Pandemic Preparedness (2022) provides the most explicit and action-oriented critique of past failures. It directly identifies misinformation, lack of trust, and insufficient public engagement as major contributors to the pandemic’s devastation. The report proposes a robust roadmap that includes a ‘vaccination-plus’ strategy, which integrates socioeconomic measures and community-level health system strengthening, and an explicit focus on human behavior as central to pandemic suppression (SDSN 2022). This document, while a retrospective analysis, sets a high bar for what a people-centric response should look like.

The WHO Pandemic Agreement (2025), in contrast, adopts a more high-level, principles-based approach. It successfully incorporates key SMB concepts by rooting the agreement in principles of equity and a ‘whole-of-society’ approach, and it acknowledges the need to protect ‘vulnerable populations’ (Evaborhene 2025). However, it largely fails to provide a detailed, prescriptive roadmap for SMB interventions. The agreement’s primary focus is on legal frameworks for equitable access to biomedical tools like vaccines and therapeutics, and a system for pathogen sharing (Correia et al. 2025). While a ‘whole-of-society’ approach is mentioned, a concrete roadmap with dedicated funding for mental health support, behavioral science teams, or specific community engagement protocols is largely absent. This creates a significant gap between the high-level principle and its actionable implementation.

Finally, the Lancet One Health Commission (2025) represents a foundational approach that informs these other documents (Winkler et al. 2025). The One Health model inherently acknowledges the interconnectedness of human and environmental health, which is a key social determinant. It promotes multisectoral and transdisciplinary approaches, which are a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for robust SMB interventions. While it provides the conceptual framework for why social factors matter, it typically focuses on the human-animal-environment interface and less on the specific mental and behavioral dynamics of a human population under stress. The gap-filling required, in the context of the Mpox review, is for these high-level frameworks to move beyond general principles and provide a detailed blueprint for how to systematically fund, staff, and deploy social and behavioral interventions in real-time, from combating stigma to establishing national mental health support systems, making them as central and well-resourced as vaccine and antiviral distribution plans.

Geopolitical dimension of policy implementation

While the policy-level discourse is increasingly advocating exclusive integration, global and national-level frameworks show a varied spectrum of integration. This ranges from explicit inclusion to subtle acknowledgment, highlighting a critical disparity in pandemic preparedness philosophies. The omission of social science, behavioral economics, and community factors is not an isolated incident but a systemic and geopolitically significant issue.

The World Health Organization (WHO), particularly in its push for a new Pandemic Agreement, has demonstrated a strong, albeit often high-level, awareness of the need for social and behavioral science. A 2022 commentary from the WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on Behavioral Insights and Sciences explicitly called for the inclusion of these disciplines in the new international instrument, citing their critical role in understanding transmission drivers and designing effective, acceptable interventions (WHO 2022a, b). While this signals a top-down recognition of the issue, the challenge remains in translating these principles into binding, country-level frameworks with clear mandates and dedicated resources for social scientists.

The recently launched India’s One Health Mission, based on the consolidation and revamping of all existing One Health efforts, is based on three pillars: integrated disease surveillance, environmental surveillance, and robust outbreak investigation mechanisms. Multiagency collaborations from health, defense, and technology, with connectivity to an international knowledge base, mobilize these pillars. Interestingly, neither the pillars nor the stakeholders have called out or involved social science and service agencies or sectors.

In contrast, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) presents a more progressive model where emphasis on improved Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) is given a central priority (Africa CDC 2024). The framework prioritizes two-way communication, active social listening, and building trust through consistent messaging via local, credible channels. This focus is rooted in the region’s long history of responding to outbreaks like Ebola and HIV, where community trust and engagement were pivotal to success (WHO 2025). Being more deeply ingrained in the practical realities of public health in diverse, low-trust environments, it provides a robust model for other nations seeking to create more inclusive and effective response strategies.

National frameworks also offer a compelling contrast. The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC), for example, has shown a growing, if sometimes reactive, integration of social and behavioral factors (Ochu et al. 2021; Ojeka-John et al. 2023). While initially modeled on the US CDC, the NCDC’s experience with outbreaks like Ebola and its COVID-19 response highlighted the critical role of social and behavioral change communication (SBCC) (Ochu et al. 2021). A 2021 study on their COVID-19 response revealed that the NCDC’s communication efforts evolved to be more community-centric, involving local leaders and using vernaculars to combat resistance to public health measures (Ojeka-John et al. 2023). The NCDC’s framework has recognized that an effective response must move away from a ‘victim-blaming’ approach to one of community empowerment, suggesting a learning process that has led to a more integrated, though not always perfect, approach.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a more formalized, yet still evolving, relationship with social and behavioral sciences. The CDC’s Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services has a dedicated team of social and behavioral scientists who work to integrate these insights into outbreak investigations (Holtzman et al. 2006). The CDC provides tools for thematic analysis of community feedback and guidelines for adapting surveys to understand public perceptions. However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed significant limitations in the US CDC’s framework, particularly its unpreparedness for the political polarization of public health issues like masking and vaccination (Valiavska and Smith-Frigerio 2020; Kerr et al. 2021). This reveals that while the US CDC has the institutional capacity for social science, its framework did not adequately anticipate or prepare for the profound influence of political and social factors on pandemic responses, a lesson that many other frameworks have yet to fully internalize.

Measuring success

To overcome the systemic barrier posed by the perceived ‘intangibility’ of SMB interventions, rigorous measurement of their impacts is imperative to secure policy and funding traction. While the actions themselves might appear intangible, their effects can be evaluated. In this direction, a Theory of Change (ToC) model is particularly well-suited for measuring the success of SMB interventions in Mpox countermeasures. Unlike more rigid models like logic models, which often fail to capture the complex, interconnected nature of public health challenges (Mills et al. 2019; Voss et al. 2025), ToC explicitly maps out the logical and causal pathways from inputs and activities to desired long-term outcomes (Romão et al. 2023).

The ToC model has been used in public health for a wide range of complex infectious diseases and social interventions (Weston et al. 2020). For example, it has been applied to evaluate interventions for cholera outbreaks, where a ToC was developed to frame a study on the effectiveness of distributing hygiene kits to households (D’Mello-Guyett et al. 2020). It has also been utilized in HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programs (Fournier et al. 2025). Interventions aimed at reducing stigma and enhancing access to care were developed to achieve the long-term objectives of reducing transmission and improving quality of life (Mahajan et al. 2008). Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers and policymakers employed infectious disease models to inform policy changes and predict outcomes. This acknowledged that SDH and human behavior were key factors in the spread of the virus (Bonell et al. 2020). These applications demonstrate the ToC’s utility in situations where a purely biomedical approach is insufficient.

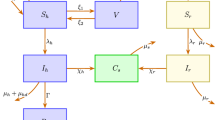

By combining evidence presented in this article and experiences from other infectious diseases, a ToC model framework is proposed here (Fig. 1). The core theory behind this is that by implementing targeted, community-driven communication and outreach, one can increase knowledge, reduce stigma, and empower individuals to adopt preventive behaviors. This, in turn, will lead to a measurable reduction in Mpox transmission and improved community well-being. As measurement endpoints, the ToC model considers the process, outcome, and proxy metrics. The process metrics, often referred to as outputs, will measure the direct results of a program’s activities. Outcome metrics measure the changes that result from the program’s activities. For example, short-term outcomes refer to immediate changes, such as an increase in public awareness of Mpox symptoms. Intermediate outcomes are the behavioral changes that follow, such as an increase in people seeking early testing. Long-term outcomes are the ultimate impacts, like a reduction in disease transmission rates. Likewise, for a social intervention, an outcome metric might be a measurable increase in vaccination uptake or a decrease in self-reported stigma. Finally, the Proxy metrics, or proxy indicators, are used when direct measurement of an outcome is complex, costly, or time-consuming, which is particularly relevant for diseases like Mpox.

The development and selection of metrics should be a collaborative process, co-designed with community representatives. This ensures that the metrics are relevant, culturally appropriate, and truly reflect the priorities and experiences of the affected communities, thereby enhancing the ‘people-centric’ approach. One promising example is the Mpox vaccine hesitancy scale, grounded in the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity in assessing vaccine hesitancy among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China (Gao et al. 2024). The scale provides valuable insights that can inform tailored interventions and public health strategies by identifying key dimensions such as maladaptive rewards, self-efficacy, response efficacy, and response costs. While this scale holds promise, further research is needed to explore its applicability and cultural adaptability in diverse settings.

Conclusion

Using Mpox as a case example of an emerging global health security threat, we presented a collection of empirical evidence in this article on the SDH, the psychological impacts of Mpox, and the dynamics of mental and behavioral responses. A scattered understanding without cohesive, contextual, and tailored measurement endpoints presents a systemic barrier to integrating social sciences, collectively underscoring the indispensable necessity of a truly integrated approach. As such, addressing SDH, mental health, and behavioral factors is not merely supplementary but fundamental to effective outbreak management and future pandemic preparedness. The neglect of these factors disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, perpetuates health inequities, and ultimately undermines the effectiveness of overall response efforts for everyone.

Therefore, achieving ‘shared success’ in global health security is inextricably linked to addressing the human dimensions of infectious diseases. This requires a fundamental paradigm shift in how public health views, plans, funds, and implements its responses. This shift moves from a predominantly disease-centric or biomedical model to a truly ‘people-centric’ model that prioritizes the SMB well-being of communities as core components of health security. In this direction, evaluating program performance through the Theory of Change model will be critical. It will inform how actions are translated into outcomes and whether further course corrections are warranted. In conclusion, investing in SMB health yields a ‘resilience dividend’ that complements the success of ‘technological dividends’, leading to a more effective outbreak preparedness ecosystem. A long-term strategic investment will be required by the collective engagement of multisectoral experts to mitigate immediate crisis impacts and also build enduring societal resilience against future health threats.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Abrams EM, Szefler SJ (2020) COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respiratory Med 8:659–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4

Acharya A, Kumar N, Singh K, Byrareddy SN (2024) Mpox in MSM: Tackling Stigma, Minimizing Risk Factors, Exploring Pathogenesis, and Treatment Approaches. Biomedical Journal 100746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2024.100746

Adepoju P (2024) Mpox declared a public health emergency. Lancet 404:e1–e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01751-3

Africa CDC (2024) JOINT PRESS RELEASE | Supporting Immediate Emergency Response for Cross Border Communities in Eastern Africa. In: Africa CDC. https://africacdc.org/news-item/joint-press-release-supporting-immediate-emergency-response-for-cross-border-communities-in-eastern-africa/. Accessed 7 Aug 2025

Alnaher S, Wolthusen R, Khan FA, Zeshan M (2024) An exploration of unique mental health challenges and resilience factors within the LGBTQ+ community: a systematic review. J Socio Psychol Religious Stud 6:10–26. https://doi.org/10.53819/81018102t4282

Alyafei A, Easton-Carr R (2025) The health belief model of behavior change. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B (2023) Virulence differences of mpox (monkeypox) virus clades I, IIa, and IIb.1 in a small animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120:e2220415120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2220415120

Bhargava A, Bhargava M, Juneja A (2021) Social determinants of tuberculosis: context, framework, and the way forward to ending TB in India. Expert Rev Respiratory Med 15:867–883. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2021.1832469

Biesty CP, Hemingway C, Woolgar J et al. (2024) Community led health promotion to counter stigma and increase trust amongst priority populations: lessons from the 2022–2023 UK mpox outbreak. BMC Public Health 24:1638. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19176-4

Bonell C, Melendez-Torres GJ, Viner RM et al. (2020) An evidence-based theory of change for reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission in reopened schools. Health Place 64:102398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102398

Braveman P, Gottlieb L (2014) The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 129:19–31

Cao X, Zheng N (2025) How does disgust affect mpox prevention? Examining the underlying mechanisms of perceived severity and perceived susceptibility moderated by stigma. Health Commun 40:713–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2364377

Carter DJ, Glaziou P, Lönnroth K et al. (2018) The impact of social protection and poverty elimination on global tuberculosis incidence: a statistical modelling analysis of Sustainable Development Goal 1. Lancet Glob Health 6:e514–e522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30195-5

CDC (2023) Impact of Mpox Outbreak on Select Behaviors | Mpox | Poxvirus | CDC. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/amis-select-behaviors.html. Accessed 26 Nov 2024

Center for outbreak response innovation, JHU (2024) Mpox virus: Clade I and II: Situation update (16 September 2024)

Christodoulidou MM, Mabbott NA (2023) Efficacy of smallpox vaccines against Mpox infections in humans. Immunother Adv 3:ltad020. https://doi.org/10.1093/immadv/ltad020

Correia T, Buissonnière M, McKee M (2025) The pandemic agreement: what’s next? Int J Health Planning Manage n/a: https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.70000

Dawes DE, Amador CM, Dunlap NJ (2022) The political determinants of health: a global panacea for health inequities. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health

Desingu PA, Rubeni TP, Nagarajan K, Sundaresan NR (2024) Molecular evolution of 2022 multi-country outbreak-causing monkeypox virus Clade IIb. iScience 27:108601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108601

D’Mello-Guyett L, Greenland K, Bonneville S et al. (2020) Distribution of hygiene kits during a cholera outbreak in Kasaï-Oriental, Democratic Republic of Congo: a process evaluation. Confl Health 14:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00294-w

El Dine FB, Gebreal A, Samhouri D et al. (2024) Ethical considerations during Mpox Outbreak: a scoping review. BMC Med Ethics 25:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-024-01078-0

Eurosurveillance editorial team (2024) Note from the editors: WHO declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. Eur Surveill 29:240815v. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.33.240815v

Evaborhene NA (2025) Africa’s role in the WHO pandemic agreement. Lancet 405:2198–2199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01122-5

Fournier B, Kwame A, Caron-Roy S et al. (2025) Process evaluation of an HIV stigma reduction intervention among young people in northern Uganda. Health Promot Int 40:daaf083. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaf083

Gao Q, Liu S, Tuerxunjiang M et al. (2025) Mpox prevention self-efficacy and associated factors among men who have sex with men in China: large cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 11:e68400. https://doi.org/10.2196/68400

Gao Y, Liu S, Xu H et al. (2024) The Mpox vaccine hesitancy scale for Mpox: links with vaccination intention among men who have sex with men in six cities of China. Vaccines (Basel) 12:1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091009

Garcia-Iglesias J, May T, Pickersgill M, et al. (2023) Social media as a public health tool during the UK mpox outbreak: a qualitativestudy of stakeholders’ experiences. BMJ Public Health 1:e000407. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjph-2023-000407

Ghazy RM, Yazbek S, Gebreal A et al. (2023) Monkeypox vaccine acceptance among ghanaians: a call for action. Vaccines (Basel) 11:240. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020240

Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (2024) The Changing Face of Pandemic Risk: 2024 Report. https://gpmb.org/reports/m/item/the-changing-face-of-pandemic-risk-2024-report. Accessed 26 Nov 2024

Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C (2017) Health disparities by sexual orientation: results and implications from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Community Health 42:1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0366-z

Gopalappa C, Khoshegbhal A (2023) Mechanistic modeling of social conditions into disease predictions for public health intervention-analyses: application to HIV. 2023.03.01.23286591

Grabenstein JD, Hacker A (2024) Vaccines against mpox: MVA-BN and LC16m8. Expert Rev Vaccines 23:796–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2024.2397006

Hassan R, Meehan AA, Hughes S et al. (2024) Health belief model to assess mpox knowledge, attitudes, and practices among residents and staff, Cook County Jail, Illinois, USA, July-August 2022. Emerg Infect Dis 30:S49–S55. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3013.230643

Health Policy Watch (2022) Exclusive: closure of world’s only manufacturing plant for Monkeypox vaccine raises questions about world’s ability to meet rising demand—health policy watch. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/exclusive-china-monkeypox-bavarian-nordics/. Accessed November 26 2024

Health TLG (2025) The health toll of economic sanctions. Lancet Glob Health 13:e1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(25)00278-5

Hogben M, Leichliter JS (2008) Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sexually Transmitted Dis 35:S13. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3cad

Hohmann LA, Garza KB (2022) The moderating power of impulsivity: a systematic literature review examining the theory of planned behavior. Pharmacy 10:85. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10040085

Holtzman D, Neumann M, Sumartoj E et al. (2006) Behavioral and social sciences and public health at CDC. MMWR Suppl 55:14–16

Hong C (2023) Mpox on Reddit: a Thematic Analysis of Online Posts on Mpox on a Social Media Platform among Key Populations. J Urban Health 100:1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00773-4

Huang M-F, Chang Y-P, Lin C-W, Yen C-F (2024) Factors related to Mpox-vaccine uptake among men who have sex with men in Taiwan: roles of information sources and emotional problems. Vaccines (Basel) 12:332. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12030332

Islam KF, Awal A, Mazumder H et al. (2023a) Social cognitive theory-based health promotion in primary care practice: a scoping review. Heliyon 9:e14889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14889

Islam MR, Haque MA, Ahamed B et al. (2023b) Assessment of vaccine perception and vaccination intention of Mpox infection among the adult males in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study findings. PLoS ONE 18:e0286322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286322

Jaleel A, Farid G, Irfan H et al. (2024) A systematic review on the mental health status of patients infected with Monkeypox Virus. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak 35:107–118. https://doi.org/10.5765/jkacap.230064

Jongen VW, Groot Bruinderink ML, Boyd A et al. (2024) What determines mpox vaccination uptake? Assessing the effect of intent-to-vaccinate versus other determinants among men who have sex with men. Vaccine 42:186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.12.018

Kang H, Rovelsky S, Kang NH et al. (2024) Variation in Mpox vaccine coverage in the United States: influence of political orientation and public health resources. Open Forum Infect Dis 11:ofae567. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofae567

Karan A, Contag CA, Pinksy B (2023) Monitoring routes of transmission for human mpox. Lancet 402:608–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01131-5

Kerr J, Panagopoulos C, van der Linden S (2021) Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Pers Individ Dif 179:110892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110892

Keum BT, Hong C, Beikzadeh M et al. (2023) Mpox stigma, online homophobia, and the mental health of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. LGBT Health 10:408–410. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2022.0281

Kota KK, Hong J, Zelaya C et al. (2023) Racial and ethnic disparities in mpox cases and vaccination among adult males—United States, May-December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 72:398–403. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a4

Kuppalli K, Dunning J, Damon I et al. (2024) The worsening mpox outbreak in Africa: a call to action. Lancet Infect Dis 24:1190–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00577-2

Leonard M, Fairman R, Polk C et al. (2023) 2674. Disparities in Mpox care: use of the social vulnerability index to predict mpox infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 10:ofad500.2285. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad500.2285

Linares-Navarro R, Sanz-Muñoz I, Oneca-Vallejo V, et al (2025) Psychosocial impact and stigma on men who have sex with men due to monkeypox. Front Public Health 13:. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1479680

Lu X, Lin Z (2021) COVID-19, Economic impact, mental health, and coping behaviors: a conceptual framework and future research directions. Front Psychol 12:759974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759974

Lua I, Silva AF, Guimarães NS, et al (2023) The effects of social determinants of health on acquired immune deficiency syndrome in a low-income population of Brazil: a retrospective cohort study of 28.3 million individuals. The Lancet Regional Health—Americas 24:. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100554

Lum F-M, Torres-Ruesta A, Tay MZ et al. (2022) Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat Rev Immunol 22:597–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4

Luo S, Jiao K, Zhang Y et al. (2024) Behavioral Intention of receiving Monkeypox vaccination and undergoing Monkeypox testing and the associated factors among young men who have sex with men in China: large cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 10:e47165. https://doi.org/10.2196/47165

Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA et al. (2008) Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 22:S67–S79. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62

Malta M, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Rimoin AW, Strathdee SA (2022) Monkeypox and global health inequities: a tale as old as time…. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:13380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013380

Maria S, Irwin P, Gillan P et al. (2024) Navigating mental health frontiers: a scoping review of accessibility for rural LGBTIQA+ communities. J Homosexuality 0:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2024.2373798

Mills T, Lawton R, Sheard L (2019) Advancing complexity science in healthcare research: the logic of logic models. BMC Med Res Methodol 19:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0701-4

Murphy L, Markey K, O’ Donnell C et al. (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre-existent mental health conditions: a scoping review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 35:375–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2021.05.002

Myrick JG, Yang Y (2022) Social cognitive theory. In EY. Ho, CL Bylund, & JCM van Wert (Eds.): The International encyclopedia of health communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, p 1–4

Nerlich B, Jaspal R (2025) Mpox in the news: social representations, identity, stigma and coping. Med Humanities 51:161–171. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2023-012786

NIAD (2024) The Antiviral Tecovirimat is Safe but Did Not Improve Clade I Mpox Resolution in Democratic Republic of the Congo|NIAID: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/antiviral-tecovirimat-safe-did-not-improve-clade-i-mpox-resolution-democratic-republic. Accessed 26 Nov 2024

Ochu CL, Akande OW, Ihekweazu V et al. (2021) Responding to a pandemic through social and behavior change communication: Nigeria’s experience. Health Secur 19:223–228. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2020.0151

Ojeka-John RO, Sanusi BO, Adelabu OT et al. (2023) Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, awareness creation and risk communication of Covid-19 pandemic amongst non-literate population in South-West Nigeria: Lessons for future health campaign. J Public Health Afr 14:2673. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2023.2673

Omame A, Iyaniwura SA, Han Q et al. (2025) Dynamics of Mpox in an HIV endemic community: a mathematical modelling approach. MBE 22:225–259. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2025010

Orsini D, Sartini M, Spagnolo AM et al. (2023) Mpox: “the stigma is as dangerous as the virus” Historical, Social, Ethical Issues and Future forthcoming: Mpox: “the stigma is as dangerous as the virus”. J Preventive Med Hyg 64:E398–E398. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2023.64.4.3144

Otmar CD, Merolla AJ (2024) Social determinants of message exposure and health anxiety among young sexual minority men in the United States During the 2022 Mpox Outbreak. Health Commun 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2397272

Paparini S, Whelan I, Mwendera C et al. (2024) Prevention of sexual transmission of mpox: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis of approaches. Infect Dis 56:589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2024.2364801

Parmenter JG, Winter SD (2025) Inequity within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) community as a distal stressor: an extension of minority stress theory. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diversity 12:308–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000674

Paterson A, Cheyne A, Tulunay H et al. (2025) Mpox stigma in the UK and implications for future outbreak control: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMC Med 23:422. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-025-04243-3

Poddar A, Rao SR (2025) The consequences of U.S. retreat from the global health security leadership. Health Secur 23:282–288. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2025.0055

Rajkhowa P, Dsouza VS, Kharel R et al. (2023) Factors influencing monkeypox vaccination: a cue to policy implementation. J Epidemiol Glob Health 13:226–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-023-00100-9

Reich JA (2020) “We are fierce, independent thinkers and intelligent”: social capital and stigma management among mothers who refuse vaccines. Soc Sci Med 257:112015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.027

Riad A, Drobov A, Rozmarinová J et al. (2022) Monkeypox knowledge and vaccine hesitancy of czech healthcare workers: a health belief model (HBM)-based study. Vaccines 10:2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10122022

Romão DMM, Setti C, Arruda LHM et al. (2023) Integration of evidence into theory of change frameworks in the healthcare sector: a rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE 18:e0282808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282808

Sachs JD, Karim SSA, Aknin L et al. (2022) The Lancet Commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic The Lancet 400:1224–1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01585-9

Sah R, Mohanty A, Reda A et al. (2022) Stigma during monkeypox outbreak. Front Public Health 10:1023519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1023519

Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK (2023) Learning from a social cognitive theory perspective. In: Tierney RJ, Rizvi F, Ercikan K (eds) International encyclopedia of education, 4th edn. Elsevier, Oxford, p 22–35