Abstract

In the light of increasing extremist attacks in Western Europe, we take a step back and provide the first large-scale, systematic, and cross-national investigation of commonalities and differences between people who hold left- or right-wing radical, political extremist, or religious fundamentalist attitudes. Using survey data from Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands, we investigate to what extent these attitudes can be explained by similar or different factors at the individual level and how much support these individuals show for political violence. Using a unique survey with newly developed and validated measures, we find several commonalities (and some differences) in the socio-demographic and socio-psychological backgrounds of radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists. However, our research shows that these groups differ strongly in their support to justify political violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently published reports documented a sharp increase in extremist attacks throughout Europe after the outbreak of the Hamas-Israel war (Renard & Cook, 2023). Given the importance of the matter, reports in the media and scholarly attention in the past focused on investigating the prevalence and origins of actual extremist attacks (e.g., Jasko et al., 2022). Unfortunately, individuals committing such crimes are only those at the utmost pinnacle of the pyramid of radicalization, and there are many more who engage in lower acts of aggression like stigmatization, out-group hate, or “armchair support” for political violence (McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017). Although these acts are not as serious as actual attacks, they can provide camaraderie and feelings of belonging for people undergoing radicalization, which can ultimately become a connective tissue between supporters and actual perpetrators of political violence (Jungkunz, Fahey, & Hino, 2024; Youngblood, 2020).

In contrast to these studies that focus on behavioral aspects, in this paper, we are interested in the attitudes that stand behind such acts, and thus in the people who share the convictions that lead to extremist behavior. This allows us to distinguish between latent attitudes and manifest forms of behavior (Ajzen, 1991). More specifically, we differentiate between political extremists, right-wing and left-wing radicals, and religious fundamentalist attitudes. We then want to know to what extent these attitudes can be explained by similar or different explanatory factors at the individual level, and to what extent the support of violence varies between these groups.

While there is some conceptual overlap between extremism, radicalism, and fundamentalism, they can also be differentiated along several dimensions. Extremism refers to any attitudes that challenge the constitutional democratic state (Backes, 1989, 2007; Isenhardt et al., 2021; Jungkunz, 2022). These anti-democratic attitudes consider ambivalence within society and politics as illegitimate (Backes, 1989; Lipset & Raab, 1971; Mudde, 2010) and build upon a claim for absolute truth, the construction of friend-and-foe images, dogmatism, a holistic and deterministic conception of history, an identitarian construction of society, dualistic rigorism, and the fundamental condemnation of the present state of being (Backes, 1989, 2007).

Religious fundamentalism (REF) shares several aspects of political extremism, especially its anti-democratic elements (Koopmans, 2015; Pfahl-Traughber, 2010). However, it focuses on religious aspects and can be described as the belief in a single collection of religious teachings that embodies the infallible truth about mankind and divinity, and that this truth is essentially challenged by forces of evil that must be fought with force (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). The fundamental equality between human beings and their individual freedom is also negated (Brandt & Reyna, 2010).

In contrast to extremism that seeks to completely abolish democracy, radicalism accepts procedural democracy but opposes the fundamental values of liberal democracy (Mudde, 2010). Among radicals, a differentiation is made between those on the political right and left: right-wing radicalism (RWR) negates the inherent equality of human beings and manifests itself in an affinity for ethnic nationalism, racism, social Darwinism, xenophobia, ethnocentrism, and antisemitism. Left-wing radicalism (LWR) extends the idea of equality to the point of superimposing individual freedom and manifests in the support of socialism, anti-fascism, anti-racism, resistance to oppressive law enforcement tactics, and opposition to capitalism, militarism, and imperialism (Jungkunz, 2022). While radicals are not extremists, as they do not oppose the constitutional democratic state, extremists can likely also be right- or left-wing radicals depending on their political preferences.Footnote 1 Finally, we primarily view radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism as attitudinal phenomena. While violent protests and militant actions are the most visible expressions, they should not be considered essential to these concepts (Backes, 2007). Equating them with violence blurs the distinction between these terms and others like fanaticism and terrorism, which are already conflated in some academic discussions (Berger, 2018; Zinchenko, 2014).

Theoretical background

The drivers of radicalism, extremism, and religious fundamentalism

The far left and far right are often perceived as fundamentally opposed, yet their intersection can be complex (Backes & Jesse, 2006; Jungkunz, 2022). For example, Nazi organizations like the SA included former communists, earning the label Beefsteak Nazis—“brown on the outside, red inside”—for their dual affiliation (Brown, 2009, 139). Similarly, leaders such as Juan Perón in Argentina and Getúlio Vargas in Brazil shaped a populist, lower-class fascism that blended extreme nationalism, corporatism, and disregard for constitutional norms (Lipset, 1959b; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). These cases are not anomalies, but reflect broader trends where regimes merge left-wing and right-wing elements (McClosky & Chong, 1985). Successful right-wing movements often adopt left-wing tactics, displaying reactionary rather than conservative ideologies (Scheuch & Klingemann, 1967). Similar observations and commonalities can be found for religious fundamentalists (Pfahl-Traughber, 2010). Thus, the strategic frameworks and ideologies of radical, extremist, and fundamentalist groups often reveal mutual patterns (Jungkunz, 2022; Pfahl-Traughber, 2010).

Radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists further share similar socio-economic and psychological profiles. Supporters of these movements tend to come from lower socio-economic backgrounds and experience social deprivation, such as broken homes and negative interactions with authorities and teachers (Infratest Wirtschaftsforschung GmbH, 1980; Klingemann & Pappi, 1972; Lipset, 1959a; Lubbers & Scheepers, 2007; Noelle-Neumann & Ring, 1984; Schils & Verhage, 2017). These individuals also tend to exhibit common personality traits, such as authoritarianism, traditionally associated with the far right, but also observed in left-wing extremists (Caprara & Vecchione, 2013; Ray, 1983; Shils, 1954) and religious fundamentalists (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992; Brandt & Reyna, 2014; Wylie & Forest, 1992). Notably, some studies show higher authoritarianism in post-communist societies, with pro-communist attitudes correlating with authoritarian tendencies (Altemeyer, 1988; Lederer & Schmidt, 1995; McFarland, 1998; McFarland et al., 1992). These findings suggest that both extremes are vulnerable to moral disengagement, a psychological mechanism enabling harmful behaviors (Bandura et al., 1996).

The primary driver behind an individual’s shift toward radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism is, however, their quest for significance, or “the fundamental human need to matter” (Webber & Kruglanski, 2017, 34), which is either triggered by the actual or by the prospective loss of importance (Kruglanski et al., 2014). This loss may occur, for instance, due to disillusionment with politics, marginalization within social groups, experiences of discrimination, income inequality, and internal drives for cognitive closure and conformity. Together, these elements foster feelings of alienation and dissatisfaction, both with societal structures and with one’s own identity (Hogg & Adelman, 2013; Hogg et al., 2013; Kruglanski et al., 2017, 2018).

Previous research has identified several characteristics that may trigger significance loss, i.e., anomia (Legge & Heitmeyer, 2012; Srole, 1956), material deprivation, socio-emotional disintegration, and experienced prejudice against one’s group or social identity (Gest et al., 2018; Pettigrew, 2016), authoritarian personality traits (Altemeyer, 1996; Oesterreich, 2005), political alienation (Paige, 1971; Pattyn et al., 2012), and low socio-structural background (Rooduijn et al., 2017; Visser et al., 2014).

All of these experiences make it more likely for someone to develop left- or right-wing radical, extremist, or fundamentalist attitudes, because such ideologies provide structured black-and-white worldviews with internal homogeneity and hierarchical leadership.

The consequences: the support of political violence

The quest for significance might not only lead to radicalism, extremism, or fundamentalism but, in a further step, even to political violence. However, violence is not a prerequisite to be considered radical, extremist, or fundamentalist (Backes, 2007). It is therefore important to distinguish between these and other concepts, such as fanaticism or terrorism, and more generally between latent attitudes and manifest forms expressed in behavior. The relationship between attitudes and behavior is complex, and various factors, such as social norms, opportunity structures, and abilities, prevent people from acting according to their attitudes (Ajzen, 1991). Moreover, we know that even among people with extremist attitudes, only a minority becomes violent (McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017; Nivette et al., 2017). Rather than lumping such attitudes and political violence together, it makes more sense to consider violence as a possible consequence of radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism. Investigating how, for instance, anti-democratic attitudes are related to attitudes towards violence could help us better understand the processes that lead to actual violence (Kruglanski et al., 2018).

The few studies that relate actual violence to attitudes focus on young people or do not differentiate between the general population, radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists (Funk et al., 1999; Nivette et al., 2017). Some differentiate between left-wing and right-wing extremist youth, but analyze their delinquency rates without taking political violence into account (Haymoz et al., 2023). Only a few look at political violence and show that 2.6% of left-wing extremists and 4.4% of right-wing extremist youth have engaged in at least one of four types of politically violent behavior in the last 12 months (Manzoni et al., 2018). However, support for violence is slightly higher among left-wing extremists (6.5%) than among right-wing extremists (4.4%). Others investigate violent incidents and show that left-wing extremists are less likely to use violence and that their attacks are less lethal (Jasko et al., 2022). However, these studies do not say anything about the potential for violence and how many extremists do not become violent or do not even support violence. Therefore, we do not know whether the number of violent acts depends on the size of the extremist groups in question.

It is, however, important to know how widespread support for violence is among radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists and how these shares compare to those among the general population. Such an approach allows us to gain an understanding of the potential of political violence, but also of the dominant norms in society and among certain groups that might make actual political violence more acceptable (Dancygier, 2023). Studies on the support of violence among the general population come to very different conclusions (Jungkunz, 2025; Vegetti & Littvay, 2022). While some show that up to 44 percent of the US population supports politically motivated violence (Kalmoe & Mason, 2022), others argue that these figures are way too large due to design and measurement problems (Holliday et al., 2024; Westwood et al., 2022). They conclude that violence is mainly concentrated at the extremes of the political spectrum, which they do not analyze further.

Data & method

Data

We conducted a survey via a recruited Bilendi online access panel in Germany (N = 2117), Great Britain (N = 2039), and the Netherlands (N = 2045) spanning from June 21 to September 13, 2022. Participation in the panel is voluntary and contingent upon a double-opt-in registration process. Prior to commencement, participants provided written informed consent through an online interface. The survey was administered in the respective official languages and achieved demographic representativeness in terms of age (18–69 years), gender, and educational attainment. The survey contained an oversampling of Muslims (for a different purpose), which is why we weighted all models to adjust for the distribution of religious background. Further information about sampling and question wording can be found in Appendix A and Tables A.1–A.2 in the Supplementary Material. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Mannheim (38/2022).

Since only a small part of the population has such attitudes, we selected countries where radical, extremist, or fundamentalist actors have played a certain role in the near past to make sure that there are enough people to investigate. We selected Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands to cover a variety of political contexts within Western Europe. Our aim is not to explain potential country differences but to see how explanatory factors at the individual level and support of violence among radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists can be generalized across different contexts.

Measures

We use newly developed and validated measures that are presented in the Supplementary Material and that have been selected from an exhaustive list of already existing national and international measures over several rounds of pre-testing (Jungkunz, Helbling, & Osenbrügge, 2024). The goal was to build succinct indices that consist of a small number of the most viable items using factor-analytic methods. At the same time, a wide conceptual scope was maintained while country-specific topics were omitted. In order to ensure measurement invariance across countries, concise scales covering the most pertinent elements of the corresponding concepts were developed. Accordingly, the specific items of each index do not necessarily cover all aspects of the respective concepts.

The scales include a six-item battery on LWR (α = 0.782), an eight-item battery on RWR (α = 0.882), and a five-item battery on general political extremism (GEX, α = 0.825). Furthermore, we use the item battery by Altemeyer & Hunsberger (2004) to capture religious fundamentalism (REF, α = 0.850). All items were measured on five-point Likert scales from do not agree at all (one) to fully agree (five). For Figs. 1 and 4, we created mean indices for all concepts and calculated cut-off values for respondents who, on average, agreed with each item of the respective scale (i.e., scored a four or higher on the indices).

Our study further contained socio-psychological and socio-demographic indicators. For anomia, we use a four-item battery (α = 0.904, Fischer & Kohr, 1980). We capture material deprivation through three items (α = 0.794, Callan et al., 2011) and socio-emotional disintegration through a two-item measure (α = 0.791, Heitmeyer et al., 2013). Due to a lack of an existing scale for political alienation, we use 15 items to form a mean index (α = 0.928). For authoritarian personality traits, we use the twelve-item battery by Oesterreich (α = 0.771, Oesterreich, 2005). The concept is superior to other attitudinal measures of authoritarianism (see e.g., Altemeyer, 1996), as it measures authoritarian traits that predate radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism in the causal chain. We further include additional social-structural information about religion and religiosity, education, sex, and age.

Finally, we capture political violence justification through four items developed by Kalmoe (Kalmoe, 2014) and an additional six items used by the German Internet Panel Study (German Internet Panel, University of Mannheim, 2024). Given the debate about political violence items in surveys (Kalmoe & Mason, 2022; Westwood et al., 2022) and the varying degree and specificity of the individual violence items, we analyze each item separately. Question wording and coding of all items are described in detail in Tables B.1–B.3 in Appendix B in the Supplementary Material.

Results

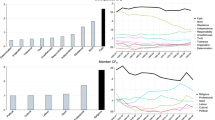

We see in Fig. 1 that on average religious fundamentalists are the smallest group across the six countries, with around two to three percent in all three countries.Footnote 2 Extremists are slightly more common in most countries in our sample, with ~3–6% of the population.Footnote 3 The share of right-wing radicals is somewhat higher and ranges between six and seven percent in all three countries. As for left-wing radicals, we find the largest group in Great Britain (15%) and somewhat lower numbers for Germany (10%) and the Netherlands (9%).Footnote 4

Socio-demographic basis

Furthermore, we like to know to what extent there are commonalities or differences between radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism with regard to socio-demographic characteristics (Fig. 2). We find that right-wing radicalism is less pronounced among women (b = −0.15, 95% CI [−0.20; −0.15]) and the higher educated (b = −0.35, 95% CI [−0.40; −0.30]), whereas the degree is somewhat higher among Protestants (b = 0.08, 95% CI [0.10; 0.15]), Catholics (b = 0.22, 95% CI [0.15; 0.29]), and Muslims (b = 0.35, 95% CI [0.24; 0.46]) as compared to people with no religion, as well as religious respondents (b = 0.23, 95% CI [0.16; 0.31]). Age and living in a more rural region play either no or only a very limited role.

Shown are standardized estimates for continuous predictors (age and region) and unstandardized estimates for all categorical indicators from bivariate linear regression models with 95% confidence intervals. LWR left-wing radicalism, RWR right-wing radicalism, REF religious fundamentalism, GEX general extremism. The reference categories are “no religion” for religion and “not religious” for religiosity. Data source: own Study (DE, GB, and NL).

Left-wing radicalism, in turn, shows a higher degree for women (b = 0.18, 95% CI [0.13; 0.23]), Muslims (b = 0.64, 95% CI [0.53; 0.75]), and religious respondents (b = 0.30, 95% CI [0.22; 0.38]), but a lower degree for the higher educated (b = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.17; −0.07]), younger individuals (β = −0.17, 95% CI [−0.20; −0.15]), and Protestants (b = −0.17, 95% CI [−0.24; −0.10]). There are no or only minor associations with rurality and being Catholic.

Religious fundamentalism is much higher among Muslims (b = 1.57, 95% CI [1.47; 1.66]) and, obviously, religious individuals (b = 1.42, 95% CI [1.36; 1.48]) and higher among Protestants (b = 0.58, 95% CI [0.52; 0.64]) and Catholics (b = 0.59, 95% CI [0.53; 0.65]). It is, however, somewhat lower among younger individuals (β = −0.17, 95% CI [−0.20; −0.15]) and the more highly educated (b = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.17; −0.07]). There is no association with sex or living in a more rural region.

Finally, extremism is substantially higher among Muslims (b = 0.68, 95% CI [0.57; 0.78]) and religious individuals (b = 0.44, 95% CI [0.37; 0.52]), and also somewhat higher among Catholics (b = 0.24, 95% CI [0.18; 0.31]), but lower among younger people (β = −0.25, 95% CI [−0.27; −0.23]) and the higher educated (b = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.18; −0.08]). We do not find significant effects with rurality, sex, or being Protestant. Overall, the pattern is quite similar in a multivariate model which includes all socio-demographic and socio-psychological characteristics (see Fig. A.1 in the Supplementary Material). The overall pattern in the pooled data is also largely similar in the three individual countries (see Figs. A.4–A.9 in the Supplementary Material).

In sum, we find that the socio-demographic basis is very similar across radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism: It is men, younger and less educated people who are more radical, extremist, or fundamentalist. There are two exceptions: Women have a higher tendency to be left-wing radicals than men, and older people are not less right-wing radical than younger people. We also find that Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, and, more generally, religious people are all more radical, extremist, and (obviously much more) fundamentalist than non-religious people. One exception is that Protestants are less left-wing radical.

Socio-psychological characteristics

Figure 3 shows the relationships between socio-psychological predictors and left- and right-wing radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism. We provide descriptive summary statistics and country-specific results in the Supplementary Material.

Right-wing radicalism is associated with a strong sense of authoritarianism (β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.26; 0.31]), feelings of anomia (β = 0.32, 95% CI [0.30; 0.35]), material deprivation (β = 0.44, 95% CI [0.42; 0.47]), and political alienation (β = 0.29, 95% CI [0.26; 0.31]) and to a somewhat lesser degree socio-emotional disintegration (β = 0.18, 95% CI [0.16; 0.21]). Although left-wing radicalism is fairly similarly characterized by feelings of anomia (β = 0.31, 95% CI [0.29; 0.34]), socio-emotional disintegration (β = 0.16, 95% CI [0.13; 0.18]) and political alienation (β = 0.31, 95% CI [0.29; 0.33]), the association with material deprivation (β = 0.30, 95% CI [0.28; 0.32]) is somewhat lower compared to right-wing radicalism, and we find a non-significant relationship with authoritarianism (β = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.02; 0.03]).

Religious fundamentalism is somewhat positively associated with authoritarianism (β = 0.10, 95% CI [0.08; 0.12]), feelings of anomia (β = 0.21, 95% CI [0.19; 0.23]), material deprivation (β = 0.22, 95% CI [0.19; 0.24]), and socio-emotional disintegration (β = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01; 0.06]), although the relationships are generally somewhat weaker compared to left- and right-wing radicalism. Uniquely for religious fundamentalism, we find no significant association with political alienation (β = 0.01, 95% CI [−0.01; 0.03]). Finally, general political extremism is also characterized by a strong sense of authoritarianism (β = 0.22, 95% CI [0.19; 0.24]), feelings of anomia (β = 0.33, 95% CI [0.31; 0.35]), and material deprivation (β = 0.44, 95% CI [0.42; 0.46]), and a weaker relationship with socio-emotional disintegration (β = 0.07, 95% CI [0.05; 0.10]) and political alienation (β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.09; 0.14]).

Taken together, we find that all socio-psychological characteristics are related to radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism. While anomia is similarly important for all four forms, the importance of the other characteristics varies between indices. Material deprivation is more important for extremism and right-wing radicalism than for left-wing radicalism and fundamentalism. Political alienation plays an important role for right- and left-wing radicalism, but no role for fundamentalism. Finally, authoritarianism is most relevant for right-wing radicalism and extremism and, to some extent, also for fundamentalism, but not for left-wing radialism. The overall pattern of these relationships is mostly consistent in a multivariate model (including all socio-demographic and socio-psychological characteristics), although the associations are somewhat weaker on average, which is to be expected given that some of the predictors correlate weakly to moderately (see Figs. A.2 and A.3 in the Supplementary Material). Only in the case of socio-emotional disintegration, we find that the relationship is substantially reduced across models. The overall patterns in the pooled data are also largely similar in the three individual countries (see Figs. A.4–A.9 in the Supplementary Material).

Support of political violence

Figure 4 shows that there is great variation in the justification of political violence across radicals, extremists, fundamentalists, and the general population that does not belong to these groups. We find the strongest justification of violence among extremists who (strongly) agree with ~48 percent (murder political opponent) to 60 percent (removal of flyers). Right-wing radicals are somewhat less, but still considerably inclined to justify violence, ranging from 32 percent (murder political opponent) to 43 percent (removal of flyers). Furthermore, about a third of left-wing radicals agrees with the use of force in politics, varying between 21 percent (murder political opponent) to 32 percent (removal of flyers). Finally, religious fundamentalists are the least likely to justify political violence, ranging from 5 percent (murder political opponent) to 19 percent (threaten politicians).Footnote 5 The support of violence among the general population varies between four and nine percent. Thus, we find a clear hierarchy that considers general extremists as the most likely to support violence, followed by right- and left-wing radicals. Religious fundamentalists show the least support, which could, however, be influenced by the question wording, which specifically mentions “politicians”, “the government”, or “a political opponent”. This overall pattern in the pooled data is also largely similar in the three individual countries (see Figs. A.10–A.12 in Supplementary Material).

Share of (strong) agreement with political violence justification statements. Respondents are considered radicals, extremists, or fundamentalists if they agreed, on average, with all items of the respective scale. Numbers in parentheses refer to the respondents who are not considered radical, extremist, or fundamentalist. LWR left-wing radicalism, RWR right-wing radicalism, REF religious fundamentalism, GEX general extremism. Data source: own study (DE, GB, and NL).

Conclusion

This paper is the first to compare different forms of political attitudes that pose a threat to (liberal) democracy using newly developed and validated indices and to examine the extent to which these attitudes are associated with similar socio-demographic, socio-psychological characteristics and similar levels of support for violence. Thus, it goes beyond many previous studies that focused on one form of radicalism, extremism, or fundamentalism. Such an approach is important because it not only allows us to find potential similarities between attitudes that are conceptually different but share certain elements, but it also enables the development of better-informed countermeasures.

We found that the socio-demographic basis is very similar across radicalism, fundamentalism, and extremism with regard to gender, age, education, place of living, and religion, with a few exceptions. It also appeared that the “basic human need to matter” plays a role for all the groups studied here, but that specific socio-psychological characteristics are more important for some than for others. There are similarities with regard to anomia and material deprivation, but also some substantial differences that point toward different origins in the radicalization process. Whereas authoritarianism positively predicts right-wing radicalism, religious fundamentalism, and general political extremism, it is negatively related to left-wing radicalism. Socio-emotional disintegration and political alienation are much more relevant for left- and right-wing radicalism than for religious fundamentalism and general political extremism.

We also learned that support for violence varies widely among radicals, extremists, and fundamentalists, despite some shared socio-psychological characteristics. There is a clear hierarchy in the justification of political violence, with the strongest support found among general political extremists, followed by right- and left-wing radicals and religious fundamentalists. The latter one has to be viewed with a grain of salt, though, as religious fundamentalists might be more inclined to support political violence for religious reasons instead of political ones.

The good news is that among the general population, only a tiny minority supports violence, and support is strongest among extremists, who themselves are a fairly small group. Nevertheless, there appears to be a widespread climate of support for violence on the fringes of European societies, which legitimizes violence and may, in turn, encourage some to act. “Armchair support” for political violence can provide feelings of camaraderie and belonging for people in the radicalization process, which can serve as a connective tissue between supporters and actual perpetrators of political violence. This is an important extension of the literature that examines actual violence without considering the potential for violence or wider support networks, or focusing only on the general population (see also the discussion of implicit extremist attitudes as discussed by Jungkunz, Helbling, & Isani, 2024).

With regards to the limitations of our research, we acknowledge the discussion about the face validity and potential overstatement of support for political violence in surveys (Kalmoe & Mason, 2022; Westwood et al., 2022). To circumvent these concerns, we specifically selected a wide range of very specific items that should make the reported figures more trustworthy. Furthermore, our work is based on attitudes, not behavior. While we understand this as a major advantage of our research, we acknowledge that holding radical, extremist, or fundamentalist attitudes does not imply that someone will follow up with respective actions. In fact, the overwhelming majority of those with such beliefs will never act (McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017).

Finally, we acknowledge potential limitations of online access panels (Couper, 2000). The key challenge is the difficulty of capturing individuals with extreme or radical views, as these groups are typically underrepresented in conventional survey modes, including web-based platforms. This underrepresentation can result from self-selection bias, where those with extreme views may be less inclined to participate, or due to barriers such as distrust of surveys and concerns about anonymity (Johnson et al., 2014). However, while this limitation affects the share of people with radical, extremist, or fundamentalist views, it should not affect our findings regarding the relative differences between the different groups we investigated. Thus, our numbers in Fig. 1 should be viewed as conservative estimates and likely to be somewhat understated.

Moreover, while online platforms ensure anonymity, which may encourage openness about sensitive topics, they also introduce issues of non-response bias. Certain demographic groups, such as older or less digitally literate individuals, may thus be excluded, further distorting the representation of extremist ideologies. Therefore, while online panels are efficient for broad attitudinal analysis, they may fail to fully capture the more hidden and marginalized populations central to studies of radicalization and extremism. This challenge is not unique to online surveys, but is a concern in most survey modes, requiring complementary strategies, such as targeted recruitment and mixed-method approaches, to address these gaps.

Data availability

Data and replication materials are available in the corresponding author’s Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IPPSHD).

Notes

Correlations between radicalism, extremism, and fundamentalism scales range between 0.18 (LWR and RWR) and 0.58 (RWR and GEX), indicating some overlap but also substantial differences between these groups (see Table A.3 in the Supplementary Material). Furthermore, left- and right-wing radicals often differ in their views on democracy and pathways to radicalization (Mudde, 2022; Youngblood, 2020). Our comparison does not equate them, but treats them as distinct phenomena worthy of investigation.

The shares of fundamentalists for Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands correspond to those other studies have found for Western European countries: Koopmans (2015) shows that less than 4 percent among Christian natives in Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria and Sweden can be considered fundamentalists. In our study, 1.7% of Christians hold fundamentalist beliefs compared to 2.9% in Great Britain and 5.1% in the Netherlands. Among Muslims, however, fundamentalism is much more widespread, ranging from 15.7% in the Netherlands to 17.5% in Germany and Great Britain (see Fig. A.13 in the Supplementary Material).

These numbers also correspond to what other studies have found in Germany (Jungkunz, 2022).

There are only three cases in which we find significant differences between Christian and Muslim fundamentalists regarding political violence justification: online harassment, being stopped from attending a political event, and getting a brick through the window. In these three instances, the share of Muslims who support these measures is about 15 to 20% higher compared to Christian fundamentalists (see Fig. A.14 in the Supplementary Material).

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav 50:179–211

Altemeyer B (1988) Enemies of freedom: understanding right-wing authoritarianism. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Altemeyer B (1996) The authoritarian specter. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Altemeyer B, Hunsberger B (1992) Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. Int J Psychol Relig 2(2):113–133

Altemeyer B, Hunsberger B (2004) A revised religious fundamentalism scale: the short and sweet of it. Int J Psychol Relig 14(1):47–54

Backes U (1989) Politischer extremismus in demokratischen verfassungsstaaten. Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden

Backes U (2007) Meaning and forms of political extremism in past and present. Cent Eur Political Stud Rev 4(4):242–262

Backes U, Jesse E (2006) Gefährdungen der freiheit: extremistische ideologien im Vergleich. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Pastorelli C (1996) Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol 71(2):364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

Berger JM (2018) Extremism. MIT Press, Cambridge

Brandt MJ, Reyna C (2010) The role of prejudice and the need for closure in religious fundamentalism. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 36(5):715–725

Brandt MJ, Reyna C (2014) To love or hate thy neighbor: the role of authoritarianism and traditionalism in explaining the link between fundamentalism and racial prejudice. Pol Psychol 35(2):207–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12077

Brown, TS (2009) Weimar radicals: Nazis and Communists between authenticity and performance. Berghahn Books, New York

Callan MJ, Shead NW, Olson JM (2011) Personal relative deprivation, delay discounting, and gambling. J Pers Soc Psychol 101(5):955–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024778

Caprara GV, Vecchione M (2013) Personality approaches to political behavior. In: Huddy L, Sears DO, Levy JS (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 23–58

Couper MP (2000) Web surveys: a review of issues and approaches. Public Opin Q 64(4):464–494. https://doi.org/10.1086/318641

Dancygier R (2023) Hate crime supporters are found across age, gender, and income groups and are susceptible to violent political appeals. Proc Natl Acad Sci 120(7):e2212757120

Decker O, Kiess J, Brähler E (2022) The dynamics of right-wing extremism within German society: escape into authoritarianism. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY

Fischer A, Kohr HU (1980) Politisches Verhalten und empirische Sozialforschung: Leistung und Grenzen von Befragungsinstrumenten. Juventa, München

Funk JB, Elliott R, Urman ML, Flores GT, Mock RM (1999) The attitudes towards violence scale. a measure for adolescents. J Interpers Violence 14(11):1123–1136

German Internet Panel, University of Mannheim (2024) German Internet Panel, Wave 60 (July 2022). GESIS https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA7880?doi%E2%80%89=%E2%80%8910.4232/1.14364

Gest J, Reny T, Mayer J (2018) Roots of the radical right: nostalgic deprivation in the United States and Britain. Comp Polit Stud 51(13):1694–1719. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017720705

Haymoz S, Baier D, Jacot C, Manzoni P, Kamenowski M, Isenhardt A (2023) Gang members and extremists in Switzerland: similarities and differences. Eur J Criminol 20(2):672–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708211029833

Heitmeyer W, Zick A, Kühnel S, Schmidt P, Wagner U, Mansel J, Reinecke J (2013) Group-oriented animosity against people (GMF-Survey 2011). GESIS Data Archive. https://search.gesis.org/research_data/ZA5576?doi = 10.4232/1.11807 Version Number: 1.0.0 Type: dataset

Hogg MA, Adelman J (2013) Uncertainty identity theory: extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. J Soc Issues 69(3):436–454

Hogg MA, Kruglanski AW, van den Bos K (2013) Uncertainty and the roots of extremism. J Soc Issues 69(3):407–418

Holliday DE, Iyengar S, Lelkes Y, Westwood SJ (2024) Uncommon and nonpartisan: antidemocratic attitudes in the American public. Proc Natl Acad Sci 121(13):e2313013121

Infratest Wirtschaftsforschung GmbH (1980) Politischer Protest in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln, Mainz

Isenhardt A, Kamenowski M, Manzoni P, Haymoz S, Jacot C, Baier D (2021) Identity diffusion and extremist attitudes in adolescence. Front Psychol 12:711466. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.711466

Jasko K, LaFree G, Piazza J, Becker MH (2022) A comparison of political violence by left-wing, right-wing, and Islamist extremists in the United States and the world. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119(30):e2122593119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122593119

Johnson TP, Holbrook AL, Atterberry K (2014) Surveying political extremists. Tourangeau, R, Edwards, B, Johnson, TP, Wolter, KM & Bates, N. Hard-to-survey populations. Cambridge University Press, Cambrige, 379–398

Jungkunz S (2022) The nature and origins of political extremism in Germany and Beyond. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Jungkunz S (2025) Economic hardship increases justification of political violence. Representation 61(1):131–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2023.2292177

Jungkunz S, Fahey RA, Hino A (2025) Populist attitudes, conspiracy beliefs and the justification of political violence at the US 2020 elections. Polit Stud 3(2):592–611

Jungkunz S, Helbling M, Isani M (2024) Measuring implicit political extremism through implicit association tests. Public Opin Q 88(1):175–192

Jungkunz S, Helbling M, Osenbrügge N (2024) Measuring political radicalism and extremism in surveys: three new scales. PLoS One 19(5):e0300661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300661

Kalmoe NP (2014) Fueling the fire: violent metaphors, trait aggression, and support for political violence. Polit Commun 31(4):545–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.852642

Kalmoe NP, Mason L (2022) Radical American Partisanship. Mapping violent hostility, its causes, and the consequences for democracy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Klingemann HD, Pappi FU (1972) Politischer Radikalismus: Theoretische und methodische Probleme der Radikalismusforschung, dargestellt am Beispiel einer Studie anläßlich der Landtagswahl 1970 in Hessen. Oldenbourg, München, Wien

Koopmans R (2015) Religious fundamentalism and hostility against out-groups: a comparison of muslims and christians in Western Europe. J Ethn Migr Stud 41(1):33–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.935307

Kruglanski AW, Gelfand MJ, Bélanger JJ, Sheveland A, Hetiarachchi M, Gunaratna R (2014) The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: how significance quest impacts violent extremism. Adv Polit Psychol 35(1):69–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12163

Kruglanski AW, Jasko K, Chernikova M, Dugas M, Webber D (2017) To the fringe and back: violent extremism and the psychology of deviance. Am Psychol 72(3):217–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000091

Kruglanski AW, Jasko K, Webber D, Chernikova M, Molinario E (2018) The making of violent extremists. Rev Gen Psychol 22(1):107–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000144

Lederer G, Schmidt P (1995) Autoritarismus und Gesellschaft. Leske + Budrich, Opladen

Legge S, Heitmeyer W (2012) Anomia and discrimination. Salzborn, S, Davidov, E & Reinecke, J. Methods, theories, and empirical applications in the social sciences. Festschrift for Peter Schmidt. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 117–125

Lipset SM (1959a) Democracy and working-class authoritarianism. Am Sociol Rev 24(4):482–501

Lipset SM (1959b) Social stratification and ’right-wing extremism’. Br J Sociol 10(4):346–382

Lipset SM, Raab E (1971) The politics of unreason. Right-wing extremism in America, 1790–1970. Heinemann, London

Lubbers M, Scheepers P (2007) Euroscepticism and extreme voting patterns in Europe. Loosveldt, G., Swyngedouw, M. & Cambré, B. Measuring Meaningful Data in Social Research. Acco, Leuven, 71–92

Manzoni P, Baier D, Haymoz S, Isenhardt A, Kamenowski M, Jacot C (2018) Verbreitung extremistischer Einstellungen und Verhaltensweisen unter Jugendlichen in der Schweiz. ZHAW Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, Zurich

McCauley C, Moskalenko S (2017) Understanding political radicalization: the two-pyramids model. Am Psychol 72(3):205–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000062

McClosky H, Chong D (1985) Similarities and differences between left-wing and right-wing radicals. Br J Polit Sci 15(3):329–363

McFarland SG (1998) Communism as religion. Int J Psychol Relig 8(1):33–48. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0801_5

McFarland SG, Ageyev VS, Abalakina-Paap MA (1992) Authoritarianism in the former Soviet Union. J Pers Soc Psychol 63(6):1004–1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.1004

Mudde C (2010) The populist radical right: a pathological normalcy. West Eur Polit 33(6):1167–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.508901

Mudde C (2022) The far-right threat in the United States: a European perspective. ANNALS Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 699(1):101–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211070060

Mudde C, Rovira Kaltwasser C (2017) Populism: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, New York

Nivette A, Eisner M, Ribeaud D (2017) Developmental predictors of violent extremist attitudes: a test of general strain theory. J Res Crime Delinq 54(6):755–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427817699035

Noelle-Neumann E, Ring E (1984) Das Extremismus-Potential unter jungen Leuten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1984. Institut für Demoskopie, Allensbach

Oesterreich D (2005) Flight into security: a new approach and measure of the authoritarian personality. Political Psychol 26(2):275–297

Paige JM (1971) Political orientation and riot participation. Am Sociol Rev 36(5):810–820

Pattyn S, van Hiel A, Dhont K, Onraet E (2012) Stripping the political cynic: a psychological exploration of the concept of political cynicism. Eur J Pers 26(6):566–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.858

Pettigrew TF (2016) In pursuit of three theories: authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Annu Rev Psychol 67:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033327

Pfahl-Traughber A (2010) Gemeinsamkeiten im Denken der Feinde einer offenen Gesellschaft: Strukturmerkmale extremistischer Ideologien. Pfahl-Traughber, A. Jahrbuch für Extremismus- und Terrorismusforschung 2009/2010. Fachhochschule des Bundes für Öffentliche Verwaltung, Brühl/Rheinland, 9–32

Ray JJ (1983) Half of all authoritarians are left wing: a reply to Eysenck and Stone. Polit Psychol 4(1):139–143

Renard T, Cook J (2023) Is the Israel-Hamas war spilling over Into Europe? https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/is-the-israel-hamas-war-spilling-over-into-europe

Rooduijn M, Burgoon B, van Elsas EJ, van de Werfhorst HG (2017) Radical distinction: support for radical left and radical right parties in Europe. Eur Union Polit 18(4):536–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517718091

Scheuch E, Klingemann HD (1967) Theorie des Rechtsradikalismus in westlichen Industriegesellschaften. In Ortlieb, H-D. & Molitor, B. Hamburger Jahrbuch für Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftspolitik. J.C.B. Mohr, Tübingen, 11–29

Schils N, Verhage A (2017) Understanding how and why young people enter radical or violent extremist groups. Int J Confl Violence 11(2):1–17

Schroeder K, Deutz-Schroeder M (2015) Gegen Staat und Kapital—für die Revolution! Linksextremismus in Deutschland—eine empirische Studie. Peter Lang, Frankfurt

Shils EE (1954) Authoritarianism: “right” and “left”. In: Christie R, Jahoda M (Eds.) Studies in the scope and method of “The Authoritarian Personality”. Free Press, Glencoe, IL, 24–49

Srole L (1956) Social integration and certain corollaries: an exploratory study. Am Sociol Rev 21(6):706–716

Vegetti F, Littvay L (2022) Belief in conspiracy theories and attitudes toward political violence. Ital Polit Sci Rev 52(1):18–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.17

Visser M, Lubbers M, Kraaykamp G, Jaspers E (2014) Support for radical left ideologies in Europe. Eur J Polit Res 53(3):541–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12048

Webber D, Kruglanski AW (2017) Psychological factors in radicalization: a “3N” approach. In: LaFree G, Freilich JD (eds) The Handbook of Criminology of the Terrorism. Wiley–Blackwell, Hoboken, 33–46

Westwood S, Grimmer J, Tyler M, Nall C (2022) Current research overstates American support for political violence. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119(12):e2116870119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116870119

Wylie L, Forest J (1992) Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism and prejudice. Psychol Rep 71(3_suppl):1291–1298. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3f.1291

Youngblood M (2020) Extremist ideology as a complex contagion: the spread of far-right radicalization in the United States between 2005 and 2017. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00546-3

Zinchenko YP (2014) Extremism from the perspective of a system approach. Psychol Russia: State Art 7(1):23–33. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2014.0103

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Project number 438614532). The funding organization had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MH, SJ, and NO; data curation: SJ and NO; formal analysis: SJ and NO; funding acquisition: MH and SJ; investigation: SJ and NO; methodology: SJ and NO; project administration: MH and SJ; resources: MH, SJ, and NO; software: SJ and NO; supervision: MH and SJ; validation: MH, SJ, and NO; visualization: SJ and NO; writing—original draft: MH and SJ; writing—review & editing: MH, SJ, and NO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Mannheim on June 16, 2022 (approval number: 38/2022). The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained in written form from all participants prior to their participation in the study. Consent was collected electronically at the beginning of the online survey, which was administered between June 21 and September 13, 2022, to adult participants (aged 18 years and older) residing in Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. Participants were first presented with an information page outlining the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, the assurance of anonymity, the types of data being collected, and the intended use of the data for academic research. Only respondents who explicitly confirmed their agreement were able to proceed to the questionnaire. All responses were stored and analyzed in anonymized form. Participants were informed that they could discontinue participation at any time without penalty. The study was based on non-interventional research and involved no interventions or foreseeable risks to participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Helbling, M., Jungkunz, S. & Osenbrügge, N. A comparison of individual needs and support of violence among radicals, extremists and fundamentalists in Western Europe. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06295-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06295-5