Abstract

This study examines how the frequency of social media usage influences the air travel behavior of Chinese residents by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Media System Dependency (MSD) theory. Utilizing 2022 CFPS data, we have applied Logit regression, instrumental variable analysis, mediation analysis, marginal effect analysis, and Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Key findings include: (1) Frequent social media usage significantly increases the likelihood of air travel, especially among individuals with poorer health; (2) Online information dependency has a positive mediating effect, whereas mobile device dependency has a negative one; (3) The negative impact of income satisfaction arises from interactions within intra-group characteristics. This study contributes by elucidating behavioral mechanisms, identifying heterogeneous effects, and validating results through robust methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

Against the backdrop of sustained economic growth and rising income levels in China, the popularization of air travel has accelerated, revealing significant potential for further expansion in this burgeoning market. According to the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC), as of 2019, almost 1 billion people in China had never taken an airplane, with the average number of air travel trips per person being only 0.47, merely 20% of the level observed in developed countries (CAAC, 2021a).

Despite competition from high-speed rail and the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, passenger traffic in China’s aviation market had rebounded to pre-pandemic levels by 2023, highlighting its growth potential (CAAC, 2021b). Forecasts from the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) indicate that the number of commercial aircraft in China is expected to represent 15% of the global market, positioning the country as a key player in the international civil aviation industry (Lee et al., 2014).

The growth prospects of the aviation industry face multiple challenges. On one hand, the widespread adoption of high-speed rail and uncertainties in international geopolitics have introduced volatility into the development of the aviation industry. On the other hand, the rise of social media platforms is influencing people’s decision-making in travel. These platforms, through innovative content dissemination and visual effects, have transformed traditional communication methods and quickly impacted people’s consumption habits and travel decisions. In China, platforms such as WeChat, TikTok, have become integral to residents’ daily lives. Their content not only meets entertainment and work needs but also influences public perceptions and attitudes toward air travel.

For civil aviation and other related industries, leveraging social media platforms for digital marketing could enhance brand awareness, even influence the construction of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) (Lerrthaitrakul & Panjakajornsak, 2014). Whereas the dissemination of negative content on social media, such as reports of aviation accidents or service complaints, can have substantial adverse effects on the public’s intention. Therefore, understanding the impact of social media and responding to the emotional fluctuations it generates has become a critical issue for the aviation industry in enhancing market competitiveness and stability. This study focuses on addressing these challenges.

Research questions

Against this realistic backdrop, this paper aims to explore three core issues: (1) Through what mechanisms does the frequency of social media usage influence individuals’ air travel behavior? (2) Is there significant heterogeneity in this impact mechanism across different groups? (3) How can multiple methods be employed to verify the robustness of the results, and provide a reliable basis for relevant industries to respond to the effects of social media? To address these questions, we propose a TPB-MSD analytical framework to examine the impact of social media usage frequency on individuals’ air travel behavior. We utilize data from the 2022 CFPS, and conduct empirical analyses using methods such as binary Logit regression, etc.

The innovations of this paper are as follows: (1) It focuses on the core variables of social media usage frequency, and provides an in-depth analysis of the specific mechanisms through which it influences individuals’ air travel behavior, thereby addressing the lack of attention to usage frequency in existing studies. (2) It clarifies the heterogeneous effects of social media from the perspective of health status and other dimensions, refining the behavioral differences among various groups. (3) By employing cross-validation with multiple empirical analysis methods, it ensures the accuracy and reliability of the research findings, offering a new perspective and methodological reference for related fields.

Literature review

The impact of social media on individual travel behavior

Existing studies examining the influence of social media on individual travel behavior can be broadly categorized into empirical and normative research. The former focuses on specific case studies, while the latter analyzes underlying mechanisms. In empirical research, Ekkapong Cheunkamon applied the Theory of Planned Behavior to investigate the impact of social media on travel planning among Thai tourists. The study found that social media influences tourists’ travel behavior intentions through factors such as satisfaction, subjective attitudes, and overall perceptions (Cheunkamon et al., 2020).

Similarly, Gulati utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine the cyclical changes in social media usage during the travel decision-making process among residents in developing countries, with a particular focus on India (Gulati, 2024). Van der Meer conducted a comparative analysis of media coverage of aviation and road accidents in the United States from 1996 to 2017, their results suggested that the risks associated with air travel were more likely to be exaggerated by the media, and that biased reporting of negative events could reinforce irrational risk-avoidance behaviors among audiences (Van Der Meer et al., 2022).

In normative research, Sobia Shahzad examined the differential impacts of social media usage across various entities, revealing that promotional activities by governments, official institutions, and tourism organizations received positive feedback through media (Shahzad et al., 2024). P. Pushparaj conducted a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms through which social media influences consumer decision-making, synthesizing 62 cases to explain why certain factors positively or negatively affect decision outcomes (Pushparaj & Kushwaha, 2024). Jumakova Lale explored how social media platforms shape individual travel decisions, noting that, based on gender analysis, females use social media more frequently than males in the travel decision-making (Wibisono & Lale, 2024).

Key factors influencing individual’s air travel behavior

As for the factors influencing air travel, the existing literature primarily concentrates on several specific determinants, including economic conditions, education levels, and health status, etc. Fangni Zhang analyzed the causal relationship between air transport and economic growth, concluding that this relationship is often bidirectional in underdeveloped economies, while in developed economies, the causal direction is typically one-way, flowing from air transport to economic growth (F. Zhang & Graham, 2020). Ae Dingil highlighted the significant impact of education levels on urban residents’ travel decisions, noting that air travel serves as a critical alternative to reliance on cars, thereby promoting the development of sustainable transportation modes (Dingil & Esztergár-Kiss, 2021).

Hongchang Li examined the competitive pressure faced by China’s aviation industry from high-speed rail, and found that the introduction of high-speed rail led to a decline of more than 50% in the number of passengers choosing air travel within 2 years, significantly impacting the growth of the aviation industry (H. Li et al., 2019). Aliza Fleischer investigated the impact of fear of flying (FOF) on air travel behavior, noting that individuals with higher levels of FOF exhibit lower price elasticity of flight demand, which in turn affects their valuation of flight attributes (Fleischer et al., 2012).

The impact of social media on air travel behavior

Direct research on the impact of social media on individual air travel behavior is relatively limited, with most studies concentrating on the content of platform information or analyzing the attributes of the media itself. Chao Pan examined the TikTok accounts of Chinese airlines, and analyzed the current state of these services and proposed four optimization strategies designed to enhance the influence of TikTok accounts in China, their goal was to strengthen recognition of the accounts among both the airlines and ordinary users (Pan & Chi, 2020).

Kai Li investigated the relationship between disaster information disseminated through media, and vicarious traumatization among users, they used the MU 5735 crash as a case, arguing that different algorithmic rules play a crucial mediating role in shaping this relationship (K. Li et al., 2024). Adam Buday highlighted the importance of social media as a tool for airlines to evaluate service quality, the findings indicated that full-service carriers typically received complaints related to service quality, whereas low-cost carriers encountered more complaints regarding delays and cancellations (University of Žilina et al., 2023).

Furthermore, a preprint study has investigated the association between the frequency of social media usage and the air travel behavior of Chinese residents. This study explicitly indicates that high-frequency social media usage, especially on platforms such as WeChat, significantly increases people’s willingness to travel by air (Z. Zhang, 2025), providing preliminary references for this research.

Summary and critical review

In summarizing the existing literature, it is evident that numerous studies have demonstrated the profound impact of social media on individuals’ travel decision-making; however, several gaps still need to be addressed.

-

1.

Theoretical dimension: Most existing studies develop analytical frameworks from perspectives such as information dissemination and consumer behavior; however, their theoretical compatibility requires further improvement.

-

2.

Content dimension: Current literature primarily focuses on specific content and tool attributes of social media, while rarely considering the potential impact of the frequency of social media usage on individual decision-making.

-

3.

Methodological dimension: Academic research currently tends to rely on single quantitative methods, such as structural equation modeling, with insufficient exploration of the interaction effects among multidimensional variables.

Against this backdrop, this paper aims to address the aforementioned gaps. Theoretically, it seeks to incorporate media factors into the Theory of Planned Behavior to elucidate the dual-path transmission mechanism through which media influences individual behavior. In terms of content, it focuses on the impact of social media usage frequency on individuals’ air travel behavior, conducts empirical analysis using Chinese case studies, and innovatively employs interaction term regression and marginal effect analysis to explore the heterogeneous characteristics involved.

Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

Core concepts of the theory of planned behavior

Socially and psychologically, individual travel behavior is shaped by personal needs and external stimuli, resulting in specific actions (Pronello & Gaborieau, 2018). In the studies of individual behavior, two major theoretical frameworks are predominant: the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), both developed by Icek Ajzen and his colleagues. These theories primarily investigate the relations between individual behavior and attitudes.

The TRA is based on the premise of rational decision-making. This theory is structured around two primary components, attitude toward the behavior and subjective norm; the former refers to an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of a specific action, with stronger attitudes leading to more definitive behaviors; the latter represents the social pressure an individual experiences when engaging in a particular behavior, highlighting the influence of social groups on individual decision-making; this theory aims to predict behavioral intentions by evaluating the consequences of actions based on the information an individual has gathered in a wholly rational manner (Yzer, 2017). Whereas in real-world scenarios, individual willpower is not autonomous; it is influenced by various factors. Hence Ajzen expanded the TRA into TPB.

The TPB further refines the framework by introducing the variable of perceived behavioral control, which reflects an individual’s perception of the extent of control they have over performing a behavior, taking into account factors such as knowledge, skills, and available information resources, this perception of control directly influences actual behavior; Ajzen emphasized a strong positive correlation between behavioral intention and the attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control; in other words, a more positive attitude and a stronger perception of control lead to a greater intention to act, and the relationships among these variables are illustrated in Fig. 1 (Ajzen, 1991).

It can be seen that the attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control are independent yet interrelated, collectively influencing both behavioral intention and actual behavior. Ajzen further argued that factors such as individual and socio-cultural characteristics, including personality, and cultural background, exert influence on these variables, ultimately shaping an individual’s intentions and behaviors (Ajzen, 1991).

Due to its comprehensive integration of individual will and the influence of the social environment, as well as its capacity to predict and explain individual behavior, the TPB has been widely applied across various fields, including travel behavior, dining, and investment (Sutton, 2001). Since the variable of perceived behavioral control inherently encompasses considerations of information acquisition channels, it offers a natural framework for integrating media-related theories, within which key variables such as social media can be further incorporated.

Theoretical integration of social media

In the context of Media System Dependency (MSD) theory, individuals are more likely to rely on media to navigate ambiguous and uncertain events, as media provide a means to address unclear information (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). Furthermore, during significant risks or crises, the frequency of media usage tends to increase, enabling individuals to acquire valuable information in a timely manner for assessing the situation (Van Aelst et al., 2021). As individuals become more reliant on media, they gradually build trust in the content provided which subsequently influences their behavioral intentions, which suggests that an individual’s behavior is affected by the media dependence they develop (Bangerter et al., 2012).

If the quality of media content fails to meet individuals’ informational needs, their trust in the media diminishes, prompting them to seek alternative sources of information (P.-P. Li & Zhong, 2022). This can lead to a phenomenon similar to the “Tacitus Trap”. Therefore, media trust and media dependence create a positive feedback loop that ultimately influences individual behavior. This relationship can be expressed in terms of the frequency of media usage, with all three variables exhibiting bidirectional correlations.

When integrating the above with the TPB, an individual’s behavior is influenced by three core independent variables: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. The inclusion of social media as a variable indicates that individual behavior is directly affected by media dependence. The development of media dependence, in turn, influences an individual’s overall assessment of available resources, which is subsequently reflected at the behavioral level as perceived behavioral control.

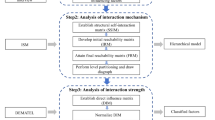

Furthermore, as media trust emerges from media dependence, the establishment of media trust inevitably impacts an individual’s attitude toward uncertain events. These resultant effects ultimately shape behavior itself. Since selecting a mode of transportation is an uncertain event, individuals typically seek information from various sources before making their final decision. Social media, as a well-established source of information, provides individuals with resources that gradually enhance their media dependence and media trust, which are manifested in terms of the frequency of media use. Through this process, social media significantly influences final travel behavior. Figure 2 offers a clearer illustration of the mechanism by which social media affects individual travel behavior.

Referring to Fig. 2, the mechanism by which social media influences individuals’ travel behavior can be further elucidated. The two most critical variables are media dependence and perceived behavioral control. Both variables can directly affect travel behavior, as indicated by the dashed lines, and can also influence travel behavior indirectly through several other mechanisms, as shown by the solid lines. Additionally, the development of media dependence within the MSD enhances individuals’ ability to control and integrate resource information, thereby directly impacting perceived behavioral control in the TPB. The resulting media trust directly influences individuals’ specific attitudes toward relevant events, with all these factors ultimately feeding back into individual behavior.

Introduction to air travel behavior and research hypotheses

Air travel, as a subset of travel behavior, falls within the scope of the proposed mechanism. When faced with the uncertainty of whether to choose air travel, individuals similarly rely on media and other channels to acquire valuable information that assists in their decision-making. If individuals receive information from social media more quickly and of higher quality than from other channels, their dependence on media and trust in it gradually develop through a process of reciprocal reinforcement, leading to an increase in the frequency of media usage.

The information individuals obtain from the media regarding air travel can be divided into two types: the positive, brand-building marketing advertisements; and the negative, complaints or safety incidents. The application of social media in air travel enhances the digital experience for users, reduces individual travel costs, and promotes airline revenue (Awori et al., 2012). While incidents such as airline accidents are infrequent, their media attention is increasing, and the disproportionate coverage of negative events further distorts individuals’ risk perception of air travel (Van Der Meer et al., 2019). As individuals’ frequency of social media usage increase, the likelihood of encountering positive or negative information theoretically becomes equal. Due to the platform algorithms and so on, individuals are likely to be exposed to one type of information over the other, affecting their decisions on air travel.

It is evident that the frequency of social media usage, given the media’s “Magnifying glass” and “Double-edged sword” functions, does not exert a uniform effect on individual air travel behavior. Considering the sporadic nature of air disasters and complaints, along with ongoing improvements in safety measures, air travel continues to be one of the safest modes of transportation (Borucka & Romele, 2024). Even with an increase in the frequency of social media usage, the impact of negative information on individual air travel behavior remains limited. Hence we propose Hypothesis 1:

H1: The frequency of social media usage generally has a positive impact on individuals’ air travel behavior.

Furthermore, based on the theoretical deduction and analytical framework of TPB-MSD, it is evident that the two variables—media dependence and perceived behavioral control—can directly influence travel behavior and also indirectly affect it through several mediating mechanisms. This suggests the presence of potential mediating effects among various variables within the framework. Therefore, when examining the impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior, it is essential to consider both the direct effects and the possible mediating roles of variables such as media dependence. Accordingly, we propose Hypothesis 2:

H2: There are mediating effects within the TPB-MSD theoretical framework, which are manifested through variables such as media dependence.

Finally, combined with the literature review, it is evident that groups differing in gender, health status, and other characteristics consider various factors when deciding whether to choose air travel, which ultimately affects their travel behavior differently. This indicates clear heterogeneity among different groups in how social media influences individuals’ air travel behavior. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3:

H3: The impact of social media usage frequency on individuals’ air travel behavior exhibits significant heterogeneity.

Data and methods

Data source

The data used in this paper are derived from the 2022 wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), conducted by Peking University. This survey project aims to track and collect multi-level data from individuals, families, and communities across China, reflecting changes in various domains such as Chinese society, economy, population, education, and health. The CFPS sample is a multi-stage probability sample drawn using implicit stratification, with a particular emphasis on geographic representation. This sampling approach not only reduces survey costs but also fully accounts for the variations in China’s social context, thereby enhancing the sample’s representativeness and explanatory power.

Variable construction

The focus of this study is to analyze the impact of social media usage frequency on Chinese residents’ air travel behavior; therefore, the dependent variable should be directly related to air travel. Based on the surveys in the 2022 CFPS, we measured respondents’ air travel behavior using their answers to the question “Have you ever taken an airplane so far?” Responses of “No” and “Yes” were coded as 0 and 1.

The independent variable should be related to the frequency of social media usage. We selected one observable variable: “In the past week, did you watch short videos or live-streaming programs on social media platforms (such as TikTok, Kwai, WeSee, etc.) almost every day” Responses of “No” and “Yes” were used to measure the respondents’ social media usage frequency, coded as 0 and 1, respectively.

As previously explained, individual and sociocultural factors—including age, personality, gender, and cultural background—can influence behavior through constructs in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), such as perceived behavioral control, behavioral attitudes, and subjective norms. Based on the content of the 2022 CFPS questionnaire, we selected and coded the following control variables: Gender (female = 0, male = 1); Age (divided into 7 groups using 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 as cut-off points, coded 1–7); Health status (divided into 5 levels from “very unhealthy” to “very healthy,” coded 1–5); Marital status (unmarried or cohabiting = 0; married, divorced, widowed, etc. = 1); Household registration (agricultural or others = 0, non-agricultural or residential = 1); Education level (below junior college = 0, junior college or above = ); Income satisfaction (measured on a five-point scale ranging from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied,” coded from 1 to 5).

In addition, the hypothesis H2 posits a mediating effect. To further test this hypothesis, we selected two variables from the 2022 CFPS that directly assess media trust and media dependency, based on Media System Dependency theory, as mediating variables. The first variable, “Daily time spent using mobile devices to access the internet,” is measured on a 5-level scale in 120-min increments, coded 1 to 5, to assess respondents’ level of media dependency. The second variable, “The importance of the internet for your learning and access to information,” is measured on a 5-level scale ranging from “very unimportant” to “very important,” coded 1 to 5, to directly measure media trust.

Overall, the selected variables were recoded based on their characteristics and transformed into categorical variables, primarily binary and ordinal polytomous types, to facilitate further analysis. For detailed variable definitions, please refer to Table 1.

Data processing and handling of missing values

The CFPS database content can be broadly categorized into four modules: the Family Member Questionnaire, the Family Economic Questionnaire, the Individual Self-Administered Questionnaire, and the Parental Proxy-Report Questionnaire for Children, with 4 separate databases were generated based on the questionnaire content and results. We merged the four 2022 databases to create a comprehensive dataset containing 54,002 observations, from which we selected and cleaned the relevant variables according to our research requirements.

Preliminary screening revealed that the dependent variable, Air, and the independent variable, Video, contained 47,016 and 24,506 non-applicable (N/A) values, both exhibiting high rates of missing data. Furthermore, the missing data mechanism was identified as Missing Not At Random (MNAR), indicating that subsequent imputation can not fully eliminate bias. Additionally, the number of complete cases obtained via listwise deletion was only 4278, limiting the explanatory power. Hence we adopted multiple imputation methods, employing Logit and Ologit models to impute binary and ordinal polytomous variables.

Given the relatively large original sample size, we generated only 5 imputed datasets, totaling ~300,000 observations. To integrate the multiple imputation results while preserving the original sample structure, we merged the 5 imputed datasets—prioritizing the retention of non-missing data from the original dataset and sequentially supplementing missing values with imputed results—ensuring no missing values remained across all variables. The final merged database included all variables with a sample size of 54,002, which not only preserved the authenticity of the original data, but also eliminated missing values through the imputation process, thereby enhancing data credibility.

After imputation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. Firstly, we compared the mean values of Video before and after imputation, as shown in Fig. 3. In the original data, the mean value of Video in the group where Air = 1 was significantly higher than in the group where Air = 0, indicating a positive correlation between Air and Video. In the imputed data, the mean value for the Air = 1 group remained higher than that of the Air = 0 group, although the difference narrowed, suggesting a weakening of the positive correlation. Overall, the sensitivity analysis confirmed that the effect of Video on Air is robust. The original sample may have overestimated the actual correlation due to data missing not at random (MNAR), and the imputed data is more representative.

Secondly, we tested the standardized coefficients of Air on Video in both the complete original dataset and the imputed dataset using two basic regression models: OLS and Logit. The results are presented in Table 2. The OLS results indicated that the effect coefficient of Video on Air decreased in the original complete sample, but the positive association remained significant. The Logit model further confirmed this trend, with the reduction in effect magnitude consistent with the direction of changes in mean differences.

Model selection

We intend to adopt a multi-method approach for this research.

(1) Descriptive Statistics: We will provide a brief characterization of the data.

(2) Benchmark regression: We will employ a binary Logit regression model to analyze the impact of various variables on individuals’ air travel behavior, comparing the results with those obtained from a Probit regression.

(3) Endogeneity analysis: We plan to revalidate the model using methods such as instrumental variable (IV) estimation, and two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) regression to address potential issues such as mutual causality.

(4) Robustness checks: We will use the control variable method, and Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to assess the robustness of the model.

(5) Mediation effect: We will apply the bootstrap method to test the significance of mediating variables, and use the KHB (Karlson-Holm-Breen) method to decompose the mediation effect.

(6) Heterogeneity analysis: We will employ interaction term regression and marginal effect analysis, to elucidate the differences in the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable across various groups.

(7) Further Analysis Section: We will employ the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition method to examine the differences arising from varying frequencies of social media usage, thereby providing empirical support.

Specification of the benchmark regression model

Given that the core dependent variable in this study—whether an individual chooses air travel—is a binary categorical variable, we selected binary Logit regression for the benchmark analysis and compared its results with those of Probit regression. The rationale for comparing these two models lies in their distinct distributional assumptions: Logit regression assumes that the random error term follows a logistic distribution, which facilitates parameter estimation via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) with relatively stable computational processes and lower sensitivity to outliers.

In contrast, Probit regression assumes the random error term follows a standard normal distribution, resulting in a more concentrated distribution curve. These differences in distributional assumptions lead to certain numerical discrepancies in the estimation results. However, in most applications, both models tend to yield consistent conclusions regarding the significance and direction of the core explanatory variables’ effects. Thus, comparing their results can further verify the reliability of the estimation outcomes.

The specific Logit model is presented as Eq. (1), where Aird denotes the cumulative probability of residents choosing air travel, with Aird ≤ 1; β0 represents the constant term of the model; β1 and βj denote the coefficients of the independent variable and control variables, respectively, with the control variables summed up; and εd stands for the random error term. Following the benchmark regression, we will further conduct a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test to assess the presence of multicollinearity among variables.

Endogeneity issues

The endogeneity issues in this paper mainly involve two aspects. First, there is a reciprocal causal relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable; second, there are other omitted variables, etc. To address these issues, we further introduce the instrumental variable method. The selection of instrumental variables must satisfy conditions such as correlation and exogeneity, they are highly correlated with the frequency of social media usage but do not have a direct impact on air travel. Based on the content of the 2022 CFPS questionnaire, we select two instrumental variables: “The importance of the internet to daily life” is measured on a five-point scale ranging from “very unimportant” to “very important,” with values assigned from 1 to 5 and labeled as the variable Life. The variable “Whether one purchased online in the past week” has responses “No” and “Yes,” coded as 0 and 1 respectively, with the variable label Pur. Since the core dependent variable is binary and the benchmark model is a Logit model, we adopt 2SRI to address endogeneity. The model specifications are as follows.

Stage 1: Use Life and Pur as instrumental variables to predict the core independent variable. The regression equation is specified as Eq. (2). Here, Videod is the core independent variable, representing the frequency with which respondents watched short videos on social platforms in the past week. Lifed and Purd serve as the instrumental variables, indicating the importance of the internet in respondents’ daily lives and whether they shopped online, respectively. Control variables that affect the frequency of short video viewing are also included. μ1d is the residual from the first-stage regression, which will be used later to control for endogeneity. From the first-stage regression, the fitted value Videod_hat of the endogenous independent variable Videod is obtained, and the residual is retained. The relevance of the instrumental variables is assessed using the F-statistic.

Stage 2: We use the predicted values of the instrumental variables from the first stage to replace the original independent variable. Since the model is based on a binary Logit framework, the second stage employs the same approach to estimate its impact on air travel behavior, as shown in Eq. (3). Here, β1 represents the coefficient of the endogenous independent variable Videod_hat, which is instrumented; μ₁d_hat is the residual term from the first stage, and λ is its coefficient. This method allows us to control for the endogeneity between social media usage frequency and air travel behavior, thereby providing a more accurate estimate of the impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior.

After completing the second-stage regression, we will further conduct an over-identification test on the instrumental variables. For example, by examining the Hansen J-statistic of the model, if the result shows p > 0.05, it indicates that there is insufficient evidence to reject the hypothesis of instrumental variable validity.

Robustness checks

To ensure the robustness of the research findings presented in this paper, we will employ multiple robustness testing methods, primarily the control variable method and the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method. The control variable method is used to ensure that other potential factors do not confound the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. We will sequentially introduce control variables such as Age, Health, and Edu into the regression model and compare the results across models with different specifications to verify the stability of the findings. Subsequently, we will apply the PSM method. As shown in Eq. (4), we will estimate the probability that an individual frequently uses social media (Video = 1) by constructing a Logit model, where PS(Xd) represents the propensity score of the d-th individual, reflecting the probability of frequent social media use conditional on the control variables Xd.

Given the large sample size of this study, to balance estimation accuracy and operational efficiency, we chose to use only K-nearest neighbor matching (K = 4) for the analysis. For each individual in the treatment group (Video = 1), four individuals with the closest propensity scores are selected from the control group (Video = 0) for matching, followed by a balance test to verify the matching quality. After this test, it is necessary to analyze the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) to measure the average treatment effect for the treatment group, as shown in Eq. (5). Here, Air1 represents the actual air travel outcome of individuals in the treatment group (Video = 1), and Air0 represents the actual air travel outcome of individuals in the control group (Video = 0). The difference between these two outcomes reflects the net effect of social media usage frequency on air travel.

Mediation effects analysis

Given that the frequency of social media usage may affect air travel through mediating variables, it is necessary to explore the mediating effects involved. Based on the contents mentioned earlier, we can set up models (6) and (7) as follows. In model (6), Mediatori,j represents two mediating variables, Mobile and Info; γj is the regression coefficient of the independent variable on each mediating variable; and εi,j is the random error term. In model (7), j’ is the coefficient representing the impact of each mediating variable on air travel behavior; and εi is the random error term.

Meanwhile, to better test the mediating effect of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior, we prefer to use the non-parametric percentile Bootstrap method. This method can accurately estimate the standard error of the mediating effect path. We set the number of Bootstrap resampling iterations to 500 and the confidence level to 95%. If the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect does not include 0, it indicates that the mediating effect is significant. In addition, we choose to further estimate the existing mediating effects through the KHB method, clarifying the direct effects, indirect effects, and contribution rates of each mediating variable to further assist in verification. Among them, the direct effect refers to the direct impact of the independent variable Video on the dependent variable Air without going through mediating variables; the indirect effect is the impact through mediating variables; the total effect is the sum of the two; and the contribution rate is the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect.

Heterogeneity analysis

To further explore the complex non-linear relationship between social media usage frequency and air travel behavior, it is essential to examine the existing heterogeneity. Given the relatively large dataset in this study, where all variables are categorical and interactive joint effects exist among them, methods such as grouped regression cannot fully or effectively utilize the data when subgroup sample sizes are small. Therefore, we prefer to analyze heterogeneity using interaction term regression, which is better suited to our circumstances. The model is presented in Eq. (8).

Based on the Logit regression model discussed earlier, we incorporate interaction terms between the independent variable Video and the control variables to capture their interaction effects Videoi*Xik. The coefficient of the interaction term allows us to more comprehensively examine how the control variables influence the relationship between Video and Air, determine whether the control variables moderate this relationship, and analyze their marginal effects. This analysis enhances the model’s predictive power and provides targeted insights for further research.

Empirical analysis results

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 presents the results of the descriptive statistics. The sample consists of a total of 54,002 observations. The mean of the dependent variable, Air, is 0.6275, indicating that nearly 40% of respondents have never flown on a plane. The mean of the independent variable, Video, is 0.7616, with a standard deviation of 0.4261. This suggests that most respondents have a relatively high frequency of social media usage, although there is some variability within the group.

In terms of the control variables: the mean Age is 4.9217, indicating that middle-aged and elderly groups constitute a relatively large proportion of the sample. The mean value of gender (Gen) is 0.5099, reflecting a relatively balanced gender ratio. The mean health score (Health) is 3.1531, suggesting that most respondents are in relatively good health. The mean marital status (Mar) is 0.8218, reflecting the majority of respondents are married. The mean education level (Edu) is 0.1373, showing that most respondents have relatively low educational level. The mean household registration status (Hukou) is 0.2753, revealing a relatively high proportion of non-agricultural household registrations. Finally, the mean income satisfaction (Inc) is 3.4483, indicating that most respondents are satisfied with their personal income.

As for the mediating variables, the mean score for Mobile is 1.7329, indicating that most respondents spend relatively little time using mobile devices to access the internet. The mean value for Life is 3.6241, suggesting that most respondents consider the internet to be fairly important in their daily lives. Additionally, the relatively high standard deviations for these variables reflect significant variability within the sample.

The results of the correlation analysis between variables are presented in Fig. 4. Notably, the correlation coefficient between Air and Video is 0.17, indicating a weak positive correlation. This suggests a preliminary positive association between high-frequency social media usage and air travel; specifically, individuals who use social media more frequently may have a slightly higher likelihood of air travel. However, the strength of this association is limited and requires validation through subsequent regression models.

Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient between Air and Hukou is 0.44, indicating that respondents with urban or non-agricultural household registrations are more likely to choose air travel. The correlation coefficient between Health and Age is -0.40, reflecting the objective trend that self-rated health tends to decline with increasing age. The correlation coefficient between Mar and Age is 0.49, which corresponds to the social reality that the proportion of married individuals increases with age. Additionally, the correlation coefficient between Edu and Hukou is 0.33, somewhat reflecting the tendency for individuals with non-agricultural household registrations to have slightly higher educational levels.

Overall, these results demonstrate the diversity and broad distribution of individuals in the sample regarding social media usage, air travel behavior, and other control variables, providing a solid foundation for subsequent steps such as model construction and empirical analysis.

Benchmark regression

The results of the benchmark regression are presented in Table 4, which compares the outcomes of Probit and Logit regression models. By examining the estimated coefficients and significance levels of the models both before and after incorporating control variables, we can clarify the direction and magnitude of the effects of the core independent variable and control variables on individuals’ air travel behavior. It is evident that, despite the differing distributional assumptions of the Logit and Probit models, the coefficients for Video are both positive and highly significant, thereby supporting the Hypothesis H1. Meanwhile, the control variables demonstrate high significance in both models, with consistent coefficient directions.

A noteworthy point is that the regression results for Inc are significantly negative, indicating that the higher an individual’s income satisfaction, the lower their probability of air travel. This finding appears to contradict basic economic principles. A preliminary hypothesis is that individuals with high income satisfaction may prefer a more stable lifestyle, while middle-income groups might have a stronger demand for air travel. This issue warrants further analysis in subsequent steps.

In addition, to assess the degree of multicollinearity among variables, we conducted a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test for each variable. Although the VIF test is based on linear relationships, its underlying logic for detecting collinearity issues is applicable to regression models, including logistic regression, thereby effectively ensuring the stability of parameter estimation. If VIF < 10 or 1/VIF is close to 1, it indicates that the correlation between the independent variable in the model and other independent variables is low, and the problem of multicollinearity is mild; otherwise, it is high, and variables with high collinearity need to be further excluded. The results are presented in Table 5. The mean VIF is 1.19, indicating no significant multicollinearity in the regression model. Additionally, the model demonstrates strong overall explanatory power.

Endogeneity analysis

To more effectively address endogeneity issues such as mutual causality and omitted variable bias in the model, we selected the instrumental variables Life and Pur and applied the 2SRI method. By constructing a two-stage model, we isolated endogeneity effects and accurately identified the causal relationships between the core variables. The results are presented in Table 6.

In the first stage, Video was set as the dependent variable, with instrumental variables Life and Pur, along with control variables. The correlation between the instrumental variables and the independent variable was verified using the F-statistic, and the fitted value, Video_hat, was generated. In the second stage, the fitted Video_hat and residuals (resid) were incorporated into the Logit model, and the exogeneity of the instrumental variables was assessed using the Hansen J-statistic.

The third column presents auxiliary analysis results obtained by directly including the instrumental variables in the Logit model. The instrumental variables Life and Pur showed a significant positive correlation, indicating that individuals who perceive the internet as more important to daily life or who engage in online shopping have a higher probability of using social media platforms to watch short videos daily.

The results confirm a strong correlation between the instrumental variables and the endogenous independent variable. Meanwhile, the reported F-statistic of 892.90 far exceeds the empirical critical value of 10, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis of “insufficient identification of instrumental variables” and confirming that the instrumental variables effectively predict the endogenous independent variable.

The coefficient of the residual (resid) in the second stage was 0.083 and statistically significant, indicating the presence of endogeneity issues, such as mutual causality, in the benchmark regression. After including the residual, the effect of endogeneity on air travel choices was isolated.

Additionally, the Hansen J-statistic was 0.1463, suggesting that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the instrumental variables are uncorrelated with the random error term. This confirms that the instrumental variables, Life and Pur, satisfy the exogeneity condition and are valid. Furthermore, although the coefficients of Video_hat and Video differed, both remained positively significant.

These results demonstrate that endogeneity issues have been adequately addressed, and the model estimation results more accurately reflect the true causal effect, providing a reliable foundation for subsequent analyses.

Robustness check

To further verify the robustness of the model, we first employed the control variable method to validate the results, as shown in Table 7. It can be observed that as control variables are sequentially added to the benchmark model, the variable consistently exhibits a significant positive effect. All control variables also generally demonstrate statistical significance, and the model’s Pseudo R-squared value increases, indicating good model fit and strong robustness.

A notable point is that the variable Gen initially exhibited a positive but insignificant effect, which gradually shifted to a significant negative effect as additional control variables were introduced. This suggests that the impact of gender on air travel may be influenced by factors such as household registration and education level, underscoring the importance of sequentially incorporating control variables to reveal the true relationship. Regardless of the inclusion of other variables, the core independent variable’s positive impact on air travel remains significant, and the model’s goodness-of-fit improves with the addition of control variables, further confirming the robustness of the research findings.

To further eliminate the potential influence of sample selection bias on the core conclusions, we employed the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method. By matching individuals with high-frequency social media usage (treatment group, Video = 1) to those with low-frequency usage (control group, Video = 0) who share similar characteristics, we simulated a randomized experimental design. Given the large sample size, we utilized 4-nearest neighbor matching (K = 4) to balance operational efficiency and estimation accuracy. The balance test results are presented in Fig. 5. Prior to matching, the standardized bias for each control variable was generally high, indicating significant differences in characteristics between the treatment and control groups in the original sample. After matching, the standardized bias for all variables decreased substantially, with the absolute bias for most variables falling below 5%, suggesting that the matching effectively balanced the characteristics between groups.

After completing the matching process, we calculated the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT), with the results presented in Table 8. The probability difference between the matched treatment group and the matched control group is 0.1299, indicating that, after balancing the characteristics between groups, high-frequency social media usage still significantly increases the probability of air travel by ~13%. This suggests that Hypothesis H1 remains valid after controlling for sample selection bias, demonstrating strong robustness.

Mediation effect analysis

The mediation effect path model generally involves two steps: first, analyzing the impact of the independent variable on the mediating variables; second, assessing the impact of the mediating variables on the dependent variable. We firstly analyzed the effect of the independent variable, Video, on the two mediating variables, Mobile and Info, individually, and then examined the impact of these mediating variables on the dependent variable, Air. The Bootstrap method was used for resampling, with the number of resamples set to 500 and the confidence interval set at 95%. If the confidence interval of the mediating effect does not include 0, it indicates a significant effect. The results are shown in Table 9. It can be seen that the confidence intervals for both Mobile and Info do not include 0, and their p-values are less than 0.05, indicating that both have significant mediating effects.

We further analyzed the mediating pathways of Mobile and Info, with the results presented in Table 10. It can be observed that the impact of social media usage on the mediating variables exhibits distinct characteristics: high-frequency social media usage (Video = 1) significantly and positively influences mobile device dependence (Mobile = 1), while it significantly and negatively affects online information dependence (Info = 1). The mediating variables also differ in the direction of their effects on air travel: mobile device dependence (Mobile = 1) significantly and negatively impacts air travel, and online information dependence (Info = 1) likewise exerts a significant negative effect on air travel.

One reason for this negative impact is that even short-term use of mobile devices can disrupt interpersonal relationships (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2013), thereby reducing individuals’ attention to complex decisions. It is also noteworthy that after incorporating the mediating variables, the direct effect of social media usage on air travel remains significant, indicating that both paths represent partial mediation. In other words, social media usage not only indirectly affects air travel through mediating variables but also exerts a direct effect. This further validates the rationality of the TPB-MSD framework.

We further measured the mediating effects using the KHB method, decomposing the total effect of social media usage on air travel into direct effects (impacts not transmitted through mediators) and indirect effects (impacts transmitted through Mobile or Info). The results are presented in Table 11.

The results indicate that the total effect of social media usage on air travel is 0.1356. Specifically, the indirect effect through mobile dependence is -0.0017, while the direct effect is 0.1373, suggesting that dependence on mobile devices plays an inhibitory role in the impact of social media usage on air travel, contributing -43.6% to the total effect. Conversely, the indirect effect through information dependence is 0.0056, with a direct effect of 0.1299, indicating that reliance on online information has a promoting effect, contributing 143.6%. These findings are corroborated by the Bootstrap test, which not only confirms the significance of the two mediating paths but also reveals directional differences among the mediating variables in the impact process, further validating the rationale of Hypothesis H2.

Heterogeneity analysis

To further investigate whether the effect of social media usage frequency on willingness to travel by air varies according to individual characteristics, this study examines heterogeneity using interaction term regression and marginal effect analysis. We selected ordered categorical variables such as Health, Age, and Inc to construct interaction terms with the independent variable Video, and incorporated them separately into the Logit model for analysis. The results are presented in Table 12.

The moderating effects of Age and Inc are limited, indicating that the influence of social media usage frequency on willingness to travel by air does not vary significantly based on age or income satisfaction. However, Health exhibits an initial moderating effect, suggesting that health status may influence the relationship between social media usage frequency and air travel willingness. Individuals in better health may be exposed to more travel-related information through social media, thereby strengthening the positive impact of social media usage on their willingness to travel by air. Nonetheless, this effect is not consistently significant and requires further validation through marginal effect analysis.

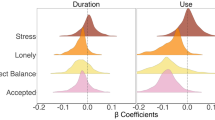

We further analyzed the marginal effects of the interaction term Video_Health, with the results presented in Fig. 6. It can be observed that the marginal effects are significant across all groups with varying health conditions. Specifically, the marginal effect for Health = 1 is ~0.09, indicating that even the group with the poorest health is positively influenced by social media.

As health status improves, the positive influence of social media significantly strengthens. When Health = 3, the marginal effect reaches its peak, indicating that individuals with moderate health are most sensitive to social media information. This group tends to underestimate the limitations imposed by their health conditions while relying on social media for travel inspiration, thereby significantly increasing their willingness to travel by air—a typical example of “optimistic bias” (Scheier et al., 2021). As health status improves further, the promoting effect begins to diminish, since better health provides greater flexibility in travel choices. Overall, the impact of social media on willingness to travel by air exhibits an inverted U-shaped, stepwise pattern, which largely supports the validity of Hypothesis H3.

Further discussion

A noteworthy observation in the benchmark regression is that, although the coefficient for Inc is statistically significant, it is negative. This suggests that as social media usage frequency increases, groups with lower income satisfaction tend to choose air travel more often. This finding appears to contradict conventional economic theory, prompting us to conduct further research into this phenomenon.

We applied the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition method for our investigation. Originally developed to analyze wage differentials in the labor market, this method has since been widely used to study group differences in various binary outcome variables (Zhou & Guo, 2021). The core principle of this method is to decompose the outcome difference between two groups (e.g., Video = 1 and Video = 0) into two components: the endowments effect, which represents the portion of the outcome difference attributable to differences in the mean values of independent variables between the groups; and the coefficients effect, which reflects the portion of the outcome difference due to differences in the regression coefficients of the independent variables on the outcome between the groups.

In this study, both Air and Video are binary variables, with the primary focus on the direction of influence and group heterogeneity of the variable Inc, which satisfies the application conditions for the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Our objective is to determine whether the negative impact of income satisfaction on air travel arises from differences in income satisfaction levels between groups with varying social media usage habits or from differences in the strength of income satisfaction’s effect on air travel across these groups. We selected Video as the grouping variable. First, we applied the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition to Inc to analyze the values of its associated effects, then sequentially included relevant control variables to observe the patterns of change in these values. The results are presented in Table 13.

Based on the overall results of the models across groups, the probability of air travel is higher among the high-frequency social media usage group (group_2 = 0.674) than among the low-frequency usage group (group_1 = 0.480), with a consistent inter-group difference of -0.193. This finding confirms a positive correlation between social media usage and air travel.

Meanwhile, as control variables are progressively included, the contributions of the decomposed components undergo systematic changes: the endowment effect value gradually shifts from 0 to -0.048, indicating that differences in characteristic levels increasingly contribute to narrowing the inter-group gap; the coefficient effect value changes from -0.193 to -0.135 (with the absolute value decreasing from 0.193 to 0.135), suggesting that after accounting for additional control variables, the explanatory power of differences in characteristic influence intensity on the inter-group gap diminishes but remains the primary source.

In the case of Inc, both its endowment effect and coefficient effect are insignificant, indicating that its negative impact does not stem from differences in income satisfaction between social media users and non-users. Instead, it arises from a synergistic interaction with other variables. For example, the high coefficient effects of Hukou and Edu in model (7) suggest that the social media user group has a higher proportion of individuals with advanced education levels and non-agricultural household registrations, who may be more sensitive to income satisfaction.

When middle-income groups experience a “scarcity mindset,” they tend to pursue immediate gratification and self-orientation, thereby reducing guilt during consumption (Tang et al., 2022), which amplifies the negative impact of Inc. The inter-group gap in air travel is primarily driven by the coefficient effects of variables such as Hukou and Edu, while the negative impact of Inc may be a characteristic within this group rather than a difference between groups. Therefore, we can conclude that the negative impact of Inc on Air is not caused by direct differences between groups but by the combined effect of various factors within the group.

Admittedly, demonstrating this issue requires further causal inference and the inclusion of additional control variables to enable a more comprehensive analysis, which also offers new directions for future research.

Conclusions

Research findings

This study examines the impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior among Chinese residents. Drawing on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Media System Dependency Theory (MSD), a dual-path transmission mechanism model is developed. Utilizing data from the 2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) and employing a range of analytical methods, the following conclusions are reached:

(1) The frequency of social media usage has a significant positive impact on air travel behavior. Individuals who frequently use social media are more likely to choose air travel, and this conclusion remains robust after controlling for endogeneity, sample selection bias, and conducting multiple robustness tests. Mechanistically, social media influences travel decisions both directly—by shaping individuals’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control regarding air travel—and indirectly. It creates a positive feedback loop of media dependence and trust, thereby enhancing the efficiency and credibility of individuals’ access to air travel information, which in turn facilitates behavioral change. Although occasional negative events on social media may trigger short-term risk aversion, the positive effects—such as increased information transparency and improved promotional communication—predominate.

(2) The mediating mechanism is dualistic. The positive mediating effect of information indicates that social media usage increases the likelihood of air travel by enhancing individuals’ reliance on online information, further confirming that information acquisition efficiency is a key driving factor. Conversely, the negative mediating effect of mobile device usage suggests that excessive dependence on mobile devices may reduce the propensity to travel by air. This is likely because fragmented usage limits time for in-depth decision-making or causes information overload, leading to delayed decisions. However, overall, the positive effect of online information outweighs the negative impact of mobile device use, resulting in a net positive effect of social media on air travel.

(3) Significant heterogeneity exists among different groups. The impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior varies across groups, particularly concerning health status. Individuals with poorer health conditions exhibit a higher propensity for air travel when frequently using social media. This may be because health-constrained individuals rely more on social media to access convenient travel information, and positive content on these platforms alleviates their concerns about long-distance travel. Additionally, the interaction effect between health status and social media usage follows an inverted U-shaped pattern: moderately healthy groups are the most sensitive to social media information, with their willingness to travel by air being most strongly stimulated; conversely, groups in excellent health show less dependence on social media due to their greater flexibility in travel choices.

Research limitations and directions for future research

(1) Limitations in data collection. This study relies on data from the 2022 CFPS, which provides only a cross-sectional snapshot at a specific point in time and cannot capture the dynamic changes between social media usage and air travel behavior. Additionally, the measurement of social media usage in the dataset focuses on social media platforms in general, potentially overlooking the differential impacts of various platforms. Furthermore, the original dataset contains a substantial number of non-applicable values; despite corresponding imputation and sensitivity analyses, it remains challenging to completely avoid bias. Future research could collect more detailed panel data to clarify the long-term dynamic relationships between variables. It could also expand the sample scope to include different countries or cultural contexts to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

(2) Limitations in Analytical Methods. Although the instrumental variable approach was employed to address endogeneity concerns, unobserved confounding variables—such as individuals’ social activity levels and information processing capabilities—may still influence the estimation results. Additionally, a bidirectional causal relationship between health status and air travel may exist but has not yet been fully elucidated. Moreover, the mediating effect analysis focused solely on mobile device dependence and online information dependence, without examining the specific transmission pathways of core variables from the Theory of Planned Behavior, such as subjective norms and perceived behavioral control. Consequently, the analysis of the “attitude-intention-behavior” sequence lacks sufficient detail. Future research should further investigate the specific roles of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control in this impact process.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the 2022 wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Researchers interested in accessing the CFPS data must submit an application through the official CFPS platform (https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/) and comply with the data usage agreement. Due to CFPS data protection regulations, processed data cannot be publicly shared.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211

Awori K, Clark E, Gonçalves A, Effner T, Yang J, Oakley I, Nunes N (2012) Flytalk: Social media to meet the needs of air travelers. CHI’12 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, pp 1769–1774

Ball-Rokeach SJ, DeFleur ML (1976) A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun Res 3:3–21

Bangerter A, Krings F, Mouton A, Gilles I, Green EGT, Clémence A (2012) Longitudinal investigation of public trust in institutions relative to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 7:e49806

Borucka A, Romele M (2024) Examining airplane accidents through the lens of fatalities in such catastrophes. 2024 12th international conference on traffic and logistic engineering (ICTLE), pp 84–87

CAAC (2021a) Northwest civil aviation launches the ‘I deliver warmth and smooth traffic to the first passengers’ activity. http://www.caac.gov.cn/local/XBGLJ/XB_XWZX/XB_DQYW/202109/t20210903_209114.html Accessed 1 Sept 2015

CAAC (2021b) Statistical bulletin of civil aviation industry development in 2023.http://www.caac.gov.cn/English/Research/Reports/Statistical/202412/t20241211_226085.htmlAccessed 27 Jun 2024

Cheunkamon E, Jomnonkwao S, Ratanavaraha V (2020) Determinant factors influencing Thai tourists’ intentions to use social media for travel planning. Sustainability 12:7252

Dingil AE, Esztergár-Kiss D (2021) The influence of education level on urban travel decision-making. Periodica Polytechnica Transport Eng 50:49–57

Fleischer A, Tchetchik A, Toledo T (2012) The impact of fear of flying on travelers’ flight choice: choice model with latent variables. J Travel Res 51:653–663

Gulati S (2024) Unveiling the tourist’s social media cycle: Use of social media during travel decision-making. Glob Knowl, Mem Commun 73:575–595

Lee K-H, Hwang H-W, Oh Y-J (2014) Study on the current status and prospects of China aviation industry. J Korean Soc Aviat Aeronautics 22:51–64

Lerrthaitrakul W, Panjakajornsak V (2014) The impact of electronic word-of-mouth factors on consumers’ buying decision-making processes in the low cost carriers: a conceptual framework. Int J Trade Econ Financ 5:142–146

Li H, Strauss J, Lu L (2019) The impact of high-speed rail on civil aviation in China. Transp Policy 74:187–200

Li K, Li J, Li Y (2024) The effects of social media usage on vicarious traumatization and the mediation role of recommendation systems usage and peer communication in China after the aircraft flight accident. Eur J Psychotraumatol 15:2337509

Li P-P, Zhong F (2022) A study on the correlation between media usage frequency and audiences’ risk perception, emotion and behavior. Front Psychol 12:822300

Pan C, Chi R (2020) Analysis and research on operation of tik tok accounts of chinese airlines. 2020 IEEE 2nd international conference on civil aviation safety and information technology (ICCASIT), Weihai, China, 2020, pp 936–939

Pronello C, Gaborieau J-B (2018) Engaging in pro-environment travel behaviour research from a psycho-social perspective: a review of behavioural variables and theories. Sustainability 10:2412

Przybylski AK, Weinstein N (2013) Can you connect with me now? how the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. J Soc Personal Relatsh 30:237–246

Pushparaj P, Kushwaha BP (2024) Social media influencer marketing: a systematic literature review using TCM and ADO framework. Int J Consum Stud 48:e13098

Scheier M, Swanson JD, Barlow MA, Greenhouse J, Wrosch C, Tindle H (2021) Optimism versus pessimism as predictors of physical health: a comprehensive reanalysis of dispositional optimism research. Am Psychol 76:529–5488

Shahzad DrS, Zeib F, Tariq N (2024) Social media adoption in tourism promotion and tourist intention: a diffusion of invovation approach. J Media Entrepreneur Stud 4:107–117. https://doi.org/10.56536/jmes.v4i.49

Sutton S (2001) Theory of planned behaviour. In: Ayers S, Baum A, McManus C, Newman S, Wallston K, Weinman J, West R (eds) Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, pp 223–228

Tang H, Li L, Su S (2022) Experiencing less leads to the use of more: The effect of a scarcity mindset on product usage. J Bus Res 149:139–148

University of Žilina, Buday A, Badánik B (2023) Social media as a tool for airline service quality assessment. Práce Štúd. https://doi.org/10.26552/pas.Z.2023.2.05

Van Aelst P, Toth F, Castro L, Štětka V, Vreese CD, Aalberg T, Cardenal AS, Corbu N, Esser F, Hopmann DN, Koc-Michalska K, Matthes J, Schemer C, Sheafer T, Splendore S, Stanyer J, Stępińska A, Strömbäck J, Theocharis Y (2021) Does a crisis change news habits? a comparative study of the effects of covid-19 on news media use in 17 European countries. Digit Journal 9:1208–1238

Van Der Meer TGLA, Kroon AC, Verhoeven P, Jonkman J (2019) Mediatization and the disproportionate attention to negative news: the case of airplane crashes. Journal Stud 20:783–803

Van Der Meer TGLA, Kroon AC, Vliegenthart R (2022) Do news media kill? how a biased news reality can overshadow real societal risks, the case of aviation and road traffic accidents. Soc Forces 101:506–530

Wibisono RD, Lale J (2024) The impact of social media on tourist destination choices: a quantitative analysis. OPSearch Am J Open Res 3:141–146

Yzer M (2017) Theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior. In: Rössler P, Hoffner CA, Zoonen L (eds) The international encyclopedia of media effects, 1st edn, Wiley, pp 1–7

Zhang F, Graham DJ (2020) Air transport and economic growth: a review of the impact mechanism and causal relationships. Transp Rev 40:506–528

Zhang Z (2025) The impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior among chinese residents: evidence from the 2022 CFPS. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202503.0702 Accessed 10 March 2025

Zhou M, Guo W (2021) Comparison of second-child fertility intentions between local and migrant women in urban China: a blinder–Oaxaca decomposition. J Ethn Migr Stud 47:2417–2438

Acknowledgements

We thank the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data source conducted by the Chinese Social Science Survey Center (ISSS) at Peking University. This research was funded by the Zhujiang College, South China Agricultural University 2024 Annual University-Level Research Project (Grant No. 2024ZJKYC015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Zhiying Zhu; Writing—review and editing, Zhiying Zhu; Project administration, Zehao Zhang; Funding acquisition, Zehao Zhang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Zhu, Z. The impact of social media usage frequency on air travel behavior: an empirical analysis from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 13, 14 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06311-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06311-8