Abstract

The study traced the development and interactions of complexity, fluency, and accuracy (CAF) in the oral production of six advanced Chinese EFL learners over a semester, adopting a Complex Dynamic Systems Theory perspective. Employing six progressive-sensitive CAF indices, we examined group-level trajectories as well as individual variation and variability. CAF development at the group level was asynchronous and non-linear, characterized by distinct trends. Specifically, lexical diversity displayed a fall-rise pattern, shifting from a decline to an increase. In contrast, overall syntactic complexity declined. Accuracy progressed with an overall improvement, while fluency demonstrated a decreasing trend. Individually, the interactional patterns diverged further: fluency and syntactic complexity often supported each other while accuracy competed with either syntactic complexity or fluency. The developmental paths and interactions were influenced by cognitive trade-offs, learners’ L2 proficiency, educational context, and fatigue. These findings corroborate CDST tenets that L2 oral development is non-linear and adaptive, implying the need for pedagogical approaches that accommodate individual variability through targeted instruction and feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST) views second language (L2) development as an ongoing, emergent process of a holistic system that comprises a wide range of interconnected and interactive subsystems (Lowie and Verspoor, 2022). From this dynamic perspective, a growing body of research has investigated L2 writing and speaking development across different learners and various contexts (see Hiver et al., 2022 for a comprehensive review). Although CDST research has mostly addressed non-oral modalities, L2 speaking deserves more attention due to its reliance on real-time processing, spontaneous formulation, and the absence of editorial opportunities (Lowie and Verspoor, 2022; Yu and Lowie, 2020). Investigating L2 oral development through a CDST lens will offer a more nuanced understanding of the developmental mechanisms of L2 speech, contributing to a more complete picture of L2 production.

As three principal traits of language production, complexity, accuracy, and fluency (CAF) are each complex, multidimensional constructs (Housen et al., 2012), and in CDST terms, CAF are a dynamic and interrelated set of constantly changing subsystems (Norris and Ortega, 2009). Current CDST-based research has explored the dynamics of its subsystems in both naturalistic settings (e.g., Hepford, 2017; Polat and Kim, 2014) and instructed L2 contexts (e.g., Chan et al., 2015; Yu and Lowie, 2020; Yu and Peng, 2024). However, these studies have not adequately examined all CAF dimensions nor employed sufficient indices to measure CAF. Additionally, similar to L2 writing development research, most CDST studies on L2 oral development tend to over-emphasize idiosyncrasy by adopting longitudinal case designs (Lowie and Verspoor, 2022), thus limiting a broader understanding of L2 development. Therefore, CDST researchers have recently advocated an integrative approach that combines both group-level and individual analyses (Hiver et al., 2022), enabling us to “see both the forest and the trees” (Bulté and Housen, 2020).

In light of this, this one-semester longitudinal study aims to investigate the development of the CAF triad and the interactions among its three components in the L2 oral production of a group of Chinese EFL learners. Firstly, we will examine the developmental patterns both at the group and individual levels, and identify intra-individual variability and inter-individual variation. Secondly, we will explore the dynamic interactions among CAF in two focal participants. The current study contributes to the existing research by offering a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of L2 oral development in the Chinese context.

Literature review

Variability and variation in L2 oral development

From a Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST) perspective, variability—both within and between individuals—is an inherent feature of any complex, dynamic system, composed of numerous interconnected subsystems that dynamically interact (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008; van Dijk et al., 2011). Studies have found clear evidence of both individual differences and changes within individual learners in second language development (e.g., Chan et al., 2015; Larsen-Freeman, 2006; Polat and Kim, 2014; Yu, 2020; Yu and Lowie, 2020).

Larsen-Freeman (2006), a pioneering study using a CDST perspective, analyzed the oral and written English production of five Chinese learners over 6 months. Her work demonstrated fluctuating paths of development characterized by inter-individual variation and intra-individual variability. It also highlighted that CAF emerges through adaptation to context, rather than a fixed plan. This study advanced the field by using a “dynamical description” approach (Larsen-Freeman, 2006, p. 594). However, with only four observations across six months, the study’s data collection exhibited larger intervals between observations than is typical in L2 educational settings. Further, it measured CAF using only four quantitative aspects, limiting its scope.

Polat and Kim (2014) tracked one advanced, untutored Turkish learner of English over 12 months in the US. It found that lexical diversity improved markedly, syntactic complexity showed modest or uncertain gains, and accuracy remained highly variable with no clear development, indicating that accuracy improvement was more challenging without formal instruction. The researchers attributed this outcome to the nature of untutored, naturalistic learning, where the learner’s language primarily developed to meet communicative needs, leading to less focus on accuracy.

Chan et al. (2015) followed two identical low-proficiency Taiwanese twins learning English for 8 months, collecting 100 oral and 100 written texts per twin. Using three syntactic complexity measures (mean length of T-unit, dependent clauses per T-unit, coordinate phrases per T-unit) and a hidden Markov model (HMM), it found that oral complexity initially exceeded written complexity, but over time the twins showed inverse developmental trends: Gloria maintained higher complexity in speaking, whereas Grace shifted toward higher complexity in writing. Despite their shared genetics and environment, the individual variation was striking. These distinct patterns support the dynamic usage-based perspective that learners individually self-organize their linguistic subsystems. This case study is especially informative for the sources of L2 variation, strongly aligning with Larsen-Freeman’s (2006) argument that while external social factors undoubtedly shape L2 development, substantial variation is also attributable to internal restructuring within the language learning system.

Drawing on Larsen-Freeman’s (2006) CAF framework, Yu and Lowie (2020), in combination with Yu (2020), incorporated multiple variables, thereby better capturing the multidimensionality of CAF. Yu and Lowie (2020) tracked oral complexity (syntactic complexity measured by mean length of AS-unit, lexical diversity indexed by VocD) and accuracy (global error-free AS-units, error-free past-tenses) of ten Chinese EFL freshmen over 12 weeks. Group averages showed linear improvement in both metrics, yet individual trajectories were non-linear and highly variable. Yu (2020), drawing on two participants’ data from Yu and Lowie’s dataset, explored how oral fluency (speed, breakdown, repair) and the CAF triad evolve and interact. The findings revealed that fluency’s three subsystems followed non-linear, highly variable paths, alternating between periods of relative stability and turbulent “restructuring” periods. One key limitation of these two studies is that the researchers did not report group-level developmental trajectories, but instead conducted product-based comparison of group means. This approach failed to reveal the process-oriented developmental patterns.

To understand the underlying causes of variability in L2 oral development, extant research has explored the influence of various individual, social, and contextual factors (Hiver and Ai-Hoorie, 2016). While learning context (e.g., Hepford, 2017; Polat and Kim, 2014) and initial L2 proficiency (e.g., Chan et al., 2015; Vercellotti, 2017; Yu and Lowie, 2020) serve as crucial underlying factors, research has empirically identified factors such as exposure to English in natural setting and prior L2 knowledge (Yu and Lowie, 2020), cognitive strain (Hepford, 2017) and motivation (Hepford, 2017; Yu and Peng, 2024).

These preceding studies have informed the present investigation in three ways. Firstly, they laid the foundation for the conceptual framework of CAF in L2 oral development research, representing a more holistic yet manageable approach. Secondly, they informed the selection of empirically grounded subconstructs and their corresponding measurements, which is essential to obtain more discernible paths of development. Finally, most of them addressed factors influencing individual variability and variation in oral development, prompting the present study to explore the underlying reasons behind such changes and disparities.

Interactions among CAF

CDST views language as a fully interconnected dynamic system where CAF subsystems interact in supportive, competitive, or conditional ways: growth in one may aid, hinder, or condition another (e.g., frequent word use precedes syntactic complexity) (Lowie et al., 2011). Research investigating CAF interactions in oral production from a CDST perspective has yielded diverging findings. For example, Hepford (2017), Yu (2020), and Yu and Lowie (2020) reported complex and dynamic interactions, where improvements in one dimension were sometimes accompanied by a decline in others (competition), while at other times, they appeared to mutually reinforce each other (support). In contrast, Vercellotti (2017) found that improvements in one CAF dimension coincided with advances in the others, suggesting that CAF dimensions developed synergistically.

Hepford (2017) conducted a 15-month longitudinal case study to track how Juan, a Spanish-speaking Fulbright scholar, developed CAF while learning English naturalistically in the U.S. Her study revealed that while the relationship between complexity and accuracy measures remained relatively stable over time, their interaction with fluency varied, influenced by the cognitive strain the learner experienced. Additionally, the learner’s fluctuating motivation impacted his focus on either complexity or accuracy at different times.

Within the context of Chinese L2 education, Yu (2020) and Yu and Lowie (2020) found interconnected and dynamic relationships among oral CAF for her two participants over a 12-week observation period. The findings revealed that CAF relations shifted over time: accuracy and fluency transitioned from competitive to supportive, whereas complexity-fluency and complexity-accuracy patterns diverged between the two learners, which were due to the influence of initial L2 proficiency and prior schooling.

Vercellotti’s (2017) study tracked 66 ESL learners (mixed L1s) enrolled in a U.S. intensive English program, collecting 294 two-minute monologues at monthly intervals over 3–10 months. CAF were operationalized as AS-unit length and VocD (complexity), percentage of error-free clauses (accuracy), and mean pause length ≥200 ms (fluency). They were analyzed with Hierarchical Linear Modeling and within-individual correlations while controlling for initial proficiency and topic. The findings consistently showed improvements across all CAF measures. Specifically, grammatical CAF advanced linearly. Lexical variety had a non-linear trajectory, showing a slight decline and followed by steeper increase over time. A CDST interpretation by Vercellotti is that CAF constructs are “connected growers” (de Bot, 2008), which require fewer attentional resources than unconnected subsystems (Spoelman and Verspoor, 2010).

Despite significant advancements, current research on CAF has disproportionately focused on individual variability rather than group-level patterns. Moreover, advanced L2 learners in the Chinese context remain underrepresented in published research. To address these gaps, the present study examines CAF’s developmental paths and their interactional patterns in the L2 oral production of a cohort of six advanced L2 learners at a Chinese university. This design draws methodological insights from existing CDST studies concerning participant sample size. Specifically, studies utilizing a longitudinal case design typically feature one or two participants, while those conducting group-level analyses commonly involve a minimum of five. Thus, the two research questions are: (1) What are the developmental trajectories of CAF in advanced learners’ L2 oral production over one semester? (2) What are the interactional patterns among CAF in advanced learners’ L2 oral production over one semester?

Methodology

Participants

The study’s participants comprised six junior English majors (three males, three females) from an intact class of twenty students at a university in eastern China, aged 20-22. They had received over ten years of formal English instruction in primary and secondary schools, where Chinese EFL teachers prioritized form-focused instruction and viewed grammar as integral to language competence or an exam requirement (Li and Xu, 2023). The participants had also completed two years of English instruction in college, during which they received approximately 10 class hours per week of various English skills courses, including Comprehensive English, Listening, Speaking, and Writing. Comprehensive English aimed to enhance overall proficiency through in-depth textbook study. In these courses, students engaged in oral activities, such as presentations and discussions, receiving feedback on their general performance and specific errors. In their junior year’s first semester, during which this study was conducted, the participants took the Academic Writing course, taught by the first researcher, an experienced instructor with over 25 years of teaching English to college students. The course was designed to cultivate argumentative writing skills, foster critical thinking, and provide a foundation for the BA Thesis Writing Course.

These participants were classified as high-intermediate/advanced English learners, a categorization consistent with Ortega and Byrnes’s (2008) identification of third-year college students as advanced learners, and with L2 development research in China (Zheng, 2012; Wang and Tao, 2020). Further supporting this classification were their scores on the Test for English Majors-Band 4 (TEM-4), a national standardized exam for English majors in Chinese universities, administered at the close of their second year. The participants’ TEM-4 scores in the written component were: Eric and Luke (90), Tina and Alex (87), Laura (82), and Joan (78). All scores exceeded the “good” level within the TEM-4’s grading system (excellent: 80–100; good: 70–79; pass: 60–69; fail: 0–59). Furthermore, post-recruitment informal discussions with the participants indicated that they had high motivation to further enhance their English proficiency, particularly their speaking skills.

Measurements of CAF

Due to the multidimensionality of CAF and the array of available measures (Norris and Ortega, 2009), selecting appropriate metrics is crucial. Following common practice, this study employs two progress-sensitive measures for each CAF component, resulting in a total of six measurements. This approach efficiently manages data and analysis, thus avoiding an overwhelming number of potential interpretations (Bulté and Housen, 2020).

Two dimensions of complexity were chosen: syntactic complexity and lexical diversity. Following Polat and Kim (2014) and Yu and Lowie (2020), we measured syntactic complexity using the mean length of AS-units (MLA). To gauge lexical diversity, we employed VocD, which was proven appropriate for analyzing oral data from L2 English speakers, as supported by Lu (2012).

Accuracy was assessed using two variables: a general measure and a specific measure. General oral accuracy, calculated by the mean number of error-free AS-units (MNEFA), offered a holistic view of participants’ L2 grammatical use (Yu and Lowie, 2020). Specific oral accuracy was measured by the percentage of correct use of verb forms (CVU), which refers to the proportion of accurately used verbs in terms of tense, aspect, modality, and subject-verb agreement (Yuan & Ellis, 2003). The more common metric of correct verb tense was not employed, as the oral tasks in this study, such as discussing whether technology brings people closer, primarily elicited opinions and did not require frequent use of the past tense.

Similarly, two measures of fluency were calculated: speed fluency and breakdown fluency. Speed fluency was operationalized as speech rate (SR), measured in syllables per minute. Breakdown fluency, indexed by pausing, was measured by mean length of pause (MLP). Both SR and MLP are considered valid indices for oral fluency (Foster et al., 2000). Table 1 presents all six CAF measures.

The Analysis of Speech Unit (AS-unit) was chosen as the unit of analysis due to its suitability for spoken language segmentation (Foster et al., 2000) and its use in prior research to measure syntactic complexity and overall accuracy in oral language development (Polat and Kim, 2014; Yu and Lowie, 2020). AS-units are defined as “a single speaker’s utterance consisting of an independent clause, or sub-clausal unit, together with any subordinate clause(s) associated with either” (Foster et al., 2000, p.365).

Data collection

The data in the present study comprised recordings of opinion-making oral tasks and semi-structured interview protocols collected throughout a 16-week semester. The monologic recordings were analyzed quantitatively to assess language development and interaction, while the interview data were used to explain the underlying reasons for the development and the influential factors. To minimize topic effects, eight different IELTS Speaking Test topics were selected across three themes: education, society, and attitude toward life.

Participants completed one oral task within three minutes every other week, with all sessions audio-recorded in a language lab, yielding eight data points per participant. In line with the TEM-4 Oral Test (Part II) format, which requires test-takers to deliver a monologue expressing opinions on a given topic, participants received three minutes of planning time, during which note-taking was permitted. Having previously taken the TEM-4 Oral Test, the participants were already familiar with this task format. Moreover, the preparation time was provided because the study began at the start of the participants’ junior year, several months after they took the TEM-4 Oral Test, thus unlikely to create additional pressure.

Individual interviews were conducted in a quiet corner of a university Café within two days after the second, fourth, sixth, and eighth recordings, resulting in four interviews per participant. Following a semi-structured guide, the interviews included questions concerning the participants’ past English learning experience, areas of focus while undertaking these oral tasks, and factors influencing their language use. The interviews were conducted in Chinese to reduce potential misunderstandings.

Data analysis

Oral task data were transcribed using the Chinese app, Tencent Meeting, and subsequently verified for accuracy by the second researcher. The transcripts were then coded for CAF in CHAT format, a standard format compatible with the Computerized Language Analysis (CLAN) software suite (MacWhinney, 2000). Syntactic complexity was calculated using the mean length of AS-unit (MLA) analysis within CLAN, while lexical diversity was quantified using the VOCD subprogram to determine the VocD value.

AS-unit segmentation was first conducted by the second researcher, following Foster et al. (2000). To ensure the reliability, the first researcher analyzed the dataset independently, and the simple percentage agreement between the two researchers was 98.8%. Through discussion, the two researchers finally reached a consensus.

Accuracy was manually computed. Following Leonard and Shea (2017), the criteria for errors were predefined: grammar errors were calculated, and pronunciation and intonation errors were excluded. The first and second researchers identified the errors and counted the values independently in the same subset of 15 samples. They achieved 93% agreement on MNEFA and 94.5% on CVU, and eventually, all disagreements were settled following a discussion. After this reliability check, the second researcher then completed the accuracy computations for the remaining data. In addition, intra-rater reliability was checked, with the second researcher doing all the counting and calculation for a second time two months later. The percentage of consistency was 98.5% (MNEFA) and 97% (CVU), respectively.

To calculate fluency, Praat and Syllable Counter (http://www.wordcalc.com/) were utilized. For each recording, total speech time and pausing time were provided by Praat. The minimum silent pauses were set to 0.3 s, following Raupach (1980). For each transcript, syllable count was supplied by the Syllable Counter.

The resulting data were analyzed by using CDST techniques, including moving min-max graphs (window size = 3) to visualize developmental trajectories, and moving correlations to visualize interactional patterns. Min-max graphs were used to highlight the degree of variability of development (van Dijk et al., 2011). A large bandwidth signifies anomalous variance, implying the potential for a phase transition; conversely, a relatively narrow bandwidth indicates a stable state. Interactional patterns were presented by moving correlation graphs, and the correlation coefficients were computed using the MS Excel spreadsheet program. The data were initially detrended and subsequently normalized (0–1 scale) to facilitate comparison (Verspoor and van Dijk, 2011).

In examining individual variability, the study first calculated the variance of each participant’s six measurements using SPSS 26.0. Based on these calculations, two participants were identified for each measure: one with the highest variance and the other with the lowest variance. This approach allowed for a focused analysis of the extremes in variability among participants. Furthermore, all interview responses were translated into English by the second researcher, and the transcriptions were cross-checked by the participants, with a few misinterpretations corrected.

Results

The development of complexity, accuracy, and fluency (CAF)

The first research question aims to explore group patterns and intra-individual variability to gain a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic development of CAF in advanced Chinese learners’ L2 speech. Therefore, measures of complexity (VocD, MLA), accuracy (MNEFA, CVU), and fluency (SR, MLP) were analyzed both at group and individual levels.

Complexity

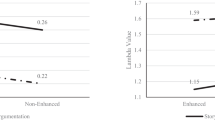

Figure 1 presents moving mix-max graphs of the group means for lexical diversity (VocD) and syntactic complexity (MLA), with second-order polynomial trendlines added to each trajectory to represent the general developmental trends. To highlight the variability in lexical diversity (VocD), we selected Tina (σ2 = 15.77) and Joan (σ2 = 4.17) because they represented the most variable and the least variable, respectively in this measure. Similarly, we selected Eric (σ2 = 3.84) and Alex (σ2 = 2.90) for syntactic complexity analysis. Contrasting high and low variance cases in VocD and MLA could better reveal diverse developmental trajectories.

Our group-level observations revealed a U-shaped trajectory for lexical diversity (VocD), with vocabulary richness increasing significantly after a dip at Week 6 and then remaining at a high level. Conversely, syntactic complexity (MLA) generally decreased, notably peaking when lexical diversity reached its lowest point. While lexical diversity tended to stabilize in the last week, syntactic complexity continued to fluctuate in the later period of the semester.

Individually, both Tina and Joan demonstrated a U-shaped developmental path for lexical diversity (VocD), as shown in Fig. 2. Tina’s lexical diversity was highly volatile initially but stabilized towards the semester’s end. Joan’s trajectory, conversely, exhibited continuous oscillation throughout the semester, with fluctuations becoming more pronounced in the later period. However, unlike Joan, Tina demonstrated a visibly increased lexical diversity at the end of the semester, indicating a development of lexical skills. In terms of syntactic complexity (MLA), Eric and Alex exhibited divergent developmental trajectories (Fig. 3). Eric’s syntactic complexity generally improved, despite a sudden drop and heightened fluctuations as the semester concluded. Alex’s syntactic complexity steadily decreased, experiencing a temporary recovery at Week 6, followed by continued decline and increased fluctuation.

Accuracy

In Fig. 4, both group-level accuracy measures (MNEFA, CVU) exhibited an upward trend, undergoing initial fluctuations, a period of stability, and then volatility during the final stage. Specifically, global accuracy (MNEFA) showed initial mild fluctuations, followed by a brief stability and increasing volatility in the late stage. In contrast, correct verb use (CVU) shifted from high volatility to relative stability and returned to volatility.

Figures 5 and 6 demonstrate the global accuracy (MNEFA) development for Alex (σ2 = 0.18) and Laura (σ2 = 0.12), and the specific accuracy (CVU) change for Tina (σ2 = 0.96) and Laura (σ2 = 0.01). At the individual level, our observations revealed distinct patterns in global accuracy. Alex’s oral output, despite an initially low starting point, followed a discernible trajectory: periods of progress and stabilization, a subsequent challenge, and then ultimate improvement. Laura’s performance, by contrast, suggests a more volatile and cyclical model, characterized by alternating phases of advancement and setbacks. When verb usage as indexed by CVU was analyzed, Tina demonstrated consistent overall improvement in accuracy after an initial instability. Conversely, Laura’s verb accuracy generally declined, characterized by a substantial fall-rise pattern, followed by further decline, recovery, and subsequent drops.

Fluency

Figure 7 illustrates a decreasing trend for group speed fluency (SR), initiated by an upward jump. This included an initial surge, followed by an abrupt decrease, further declines, recovery, and a final decline. In contrast, group breakdown fluency (MLP) displayed an oscillating growth trajectory, transitioning from greater to reduced variability over time. Both trajectories, considering the nature of MLP as a negative fluency indicator, converge to suggest an overall decrease in fluency, marked by increasing stability reflected in the declining volatility.

Individual analysis focused on Eric and Luke, who represented the most contrasting patterns in the two fluency measures: Eric (σ2 = 17.02) and Luke (σ2 = 12.79) for SR; Eric (σ2 = 0.16) and Luke (σ2 = 0.03) for MLP.

As demonstrated in Figs. 8 and 9, the trajectories of Eric and Luke revealed intriguing differences. Initially, Eric’s fluency was lower than Luke’s, as indicated by Eric’s slower SR. However, Eric became more fluent over time, with an increasing SR, although his pausing time increased slightly. This longer, more considered delivery contrasted with Luke, whose SR decreased while his pausing time showed a decreasing trend from the fourth week, highlighting a more connected speech flow as the semester progressed.

Interactions among CAF

Our second research question concerns the relationships among CAF. Global measures of CAF were used as they are more effective for analyzing the relationship (Skehan and Foster, 1999; Yu and Lowie, 2020); specifically, lexical diversity (VocD) and mean length of AS-units (MLA) for lexical and syntactic complexity, mean number of error-free AS-units (MNEFA) for accuracy, and SR for fluency.

To investigate inter-individual variation, we chose Tina and Laura as illustrative exemplars because their variances across the four key measures were consistently at the extremes. Tina’s variances ranked in the top three (VocD, σ2 = 15.78; MLA, σ2 = 2.92; MNEFA, σ2 = 0.17; SR, σ2 = 14.76), and Laura’s were among the bottom three (VocD, σ2 = 12.11; MLA, σ2 = 1.78; MNEFA, σ2 = 0.12; SR, σ2 = 14.06). It should be noted that SR variability for Laura is comparable to Tina’s, suggesting that inter-individual differences may not fully explain the extreme values for this measure.

Interactions between complexity and accuracy

Figure 10 illustrates the changing relationship between lexical diversity (VocD) and accuracy (MNEFA) over time. For Tina, the correlation was initially negative but then shifted to positive. While a brief reversion to a slightly negative correlation occurred, the relationship subsequently became consistently positive, suggesting that lexical diversity and accuracy improved simultaneously as the study progressed. In contrast, the correlation for Laura fluctuated throughout the study. The final correlation was negative, indicating a potential inverse relationship between lexical diversity and accuracy near the study’s conclusion. This fluctuation and eventual negative correlation suggest that Laura’s lexical diversity and accuracy did not develop simultaneously; instead, periods of increased lexical diversity may have been associated with decreases in accuracy, vice versa.

As shown in Fig. 10, the interplay between syntactic complexity (MLA) and grammatical accuracy (MNEFA) for both Tina and Laura revealed a highly competitive relationship, suggesting a trade-off between the two, particularly for Tina. However, Tina’s correlation displayed fluctuations during weeks 6 and 7, whereas Laura’s remained relatively stable. This pattern suggests that Tina may have been experimenting with different levels of complexity, potentially at the expense of accuracy, while Laura appeared to adopt a more consistent strategy for balancing these two aspects of linguistic performance.

Interactions between complexity and fluency

Figure 11 illustrates a primarily competitive interaction between vocabulary diversity (VocD) and speed fluency (SR) for Tina, whereas Laura’s relationship showed considerable variability. Tina’s lexical diversity and fluency initially supported each other, but quickly transitioned into a competitive relationship. Despite a positive correlation at Week 5, the general trend suggests that as her VocD increased, her SR decreased, or vice versa. Laura’s data displayed fluctuations between negative and positive correlations, indicating that vocabulary expansion sometimes hindered fluency, or the reverse. Ultimately, the relationship reverted to a positive correlation towards the end of the semester, highlighting her improved ability to use a wider vocabulary fluently.

The interaction between syntactic complexity (MLA) and SR demonstrated a generally convergent pattern for both Tina and Laura (Fig. 11). Despite Laura’s increased variability, both participants exhibited a largely positive correlation, particularly in the latter half of the semester, suggesting that increased syntactic complexity coincided with improved SR. This shared trend implies that both Tina and Laura could expand their syntactic repertoire without compromising fluency, potentially indicative of their growing language proficiency and communicative efficiency.

Interactions between accuracy and fluency

Figure 12 reveals that the interaction between accuracy (MNEFA) and fluency (SR) was predominantly competitive for both Tina and Laura. For both participants, the development of these two subsystems appeared generally asynchronous throughout the study, marked by distinct periods where they were in full competition. While this competitive trend held true for most of the study for Tina, Laura experienced a brief positive correlation at Week 4, indicating a temporary period where improvements in both accuracy and fluency coincided. This overall competitive relationship suggests that an increased focus on one aspect, whether fluency or accuracy, often led to a decline in the other for both Laura and Tina.

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to investigate the development and interaction of CAF in the L2 monologic speaking of advanced Chinese learners over a semester. Conducting both group-level and individual analyses to uncover the general patterns as well as idiosyncrasies, we have yielded insightful findings.

Generally, the development of L2 speaking among participants displayed discordant patterns across the three dimensions of CAF. Specifically, Lexical complexity followed a fall-rise trend, while syntactic complexity generally declined. Accuracy showed an overall increase, whereas fluency demonstrated a decreasing trend. This unsynchronized development was not only evident at the group level but also reflected in individual learners. For instance, moving correlation graphs of Tina and Laura revealed that their fluency-accuracy and syntactic complexity-accuracy interactions remained largely competitive, although their lexical diversity-fluency and lexical diversity-accuracy interactions fluctuated between competitive and supportive phases. These findings resonate with broader theoretical perspectives. Specifically, they support Skehan’s (2009) contention that the simultaneous development of all three CAF components is uncommon, and that fluency tends to align with either accuracy or complexity, but typically not both.

One important factor for the discordant development of participants’ oral complexity, accuracy and fluency could be the trade-off effect. According to the Limited Capacity Hypothesis (Skehan, 1998, 2009), maintaining accuracy and complexity concurrently can create tension when resources are constrained. Given the documented improvements in accuracy throughout the semester, participants may have strategically allocated their cognitive attentional resources towards achieving higher accuracy. This prioritization likely came at the expense of syntactic complexity, leading to its observed decline in these productive activities.

Our further observation of individual participants, such as Tina and Laura, revealed a similar finding, i.e., the accuracy-syntactic complexity interaction was predominantly negative. This aligns with Hepford’s research (2017), where elaboration—measured by words per AS-unit and thus analogous to the syntactic complexity measure of MLA in our study—and accuracy are found to be in a competitive relationship for her naturalistic learner. The consistency between our results and Hepford’s across differing learner contexts provides evidence for the hypothesis that the inherent trade-off between syntactic complexity and accuracy in L2 oral performance is largely independent of the educational setting (whether instructed or naturalistic). This conclusion, however, must be viewed with caution, given the small sample sizes.

Evidence supporting the trade-off effect is evident in Alex’s interview data. Alex’s syntactic complexity declined overall while his general accuracy improved over the semester. He reported in the first interview noticing frequent errors in his oral output, which he perceived negatively impacted the quality of his L2 production. To mitigate this, he made a deliberate decision to “use simple sentence structures and avoid complex sentences where possible”. This self-reported strategy aligns with a CDST perspective, which posits that learners’ attentional focus shifts developmentally (Verspoor and Behrens, 2011). Such situation-specific shifts likely led to declining syntactic complexity in compensation for enhanced accuracy in Alex’s oral production.

Learners’ L2 proficiency level could be another contributing factor. Our study, specifically focusing on advanced learners, identified an asynchronous developmental pattern: a fall-rise trajectory for lexical diversity alongside a decreasing trend in syntactic complexity. This stands in direct contrast to research on lower-proficiency learners. For instance, Yu and Lowie (2020) observed a concerted development in complexity and accuracy among two intermediate-level Chinese learners. Similarly, Vercellotti (2017) reported synchronous, consistent improvement across all CAF measures for a group of students in an intensive English program in the U.S., whose initial proficiency was considerably below advanced. These opposing findings suggest that the interplay between proficiency and CAF development evolves across different stages of L2 acquisition, potentially becoming more challenging to coordinate as learners reach higher proficiency levels.

As an exception to competitive interactions, the co-development of fluency and syntactic complexity identified in Tina and Laura was also likely due to the proficiency level effect. Both participants exhibited a generally supportive relationship between fluency and syntactic complexity, a finding in alignment with Norris and Ortega (2009) that both relative fluency and higher complexity combined tended to be good predictors for more advanced learners.

Thirdly, the blended influence of China’s educational context and instructional practices played a crucial role. The increased accuracy at the expense of syntactic complexity, as evidenced by Tina and Laura’s interactional patterns, contrasted with Polat and Kim (2014), who documented progress in complexity without corresponding gains in accuracy in an untutored, naturalistic L2 learner. This inconsistency was likely due to the participants’ different priorities in oral production. While Polat and Kim’s untutored speaker prioritized workplace communicative effectiveness rather than grammatical accuracy, participants in this study had been instructed to prioritize accuracy, even in meaning-focused activities. This instructional approach mirrors the pervasive form-focused instruction in Chinese EFL education, where grammar teaching holds a significant role in secondary schools (Li and Xu, 2023). Such a strong emphasis on grammatical accuracy persists at the university level, where instructors continue to prioritize error correction in oral feedback. This was supported by Alex’s fourth interview data, in which he reported that “We have been taught to use correct English in school and at college. So I’m cautious about whether my speaking contains errors or not.” Taken together, this interplay between macro-level educational traditions and micro-level instructional practices collectively shaped the learners’ prioritization of accuracy over other dimensions.

Beyond its influence on accuracy, the instructional setting may also explain another developmental pattern: while our participants’ lexical and syntactic complexity both declined in the early stage, lexical complexity improved in the later stage. This was possibly due to formal classroom instructions, which directed their attention to lexical development. This was supported by Tina’s second interview data, which revealed that their teachers “liked listing the synonyms of the new word and using examples from real life to make sentences” to help them “understand the meaning and learn about the usage”. Although she admitted that they had few opportunities to “actively use the new words”, the primary focus on lexical acquisition provided important input for their lexical knowledge and might have eased their cognitive burden that confronted them in the earlier stage. By contrast, less instructional focus on syntactical knowledge might have resulted in less attention to syntactic production, thus partly contributing to their declining syntactic complexity. Evidence came from Alex, who reported deliberate avoidance of complex structures in his speech, which was also influenced by the classroom instruction:

In our Academic Writing course this semester, our professor gave us examples of what good English writing is, and using lengthy and complex structures was not encouraged. I think it is also true for English speaking. So, I’m practicing simpler structures when I speak. (Alex, 3rd interview)

Alex’s comment suggests that, for him, recent pedagogical experiences encouraged a focus on simplicity, which in turn led to a conscious compromise of syntactic complexity in his oral production.

Within the same educational setting, however, Eric’s oral development stood out as a distinct case, whose trajectory highlights the role of additional educational experiences beyond regular classroom activities. Unlike the rest of the group who showed trade-offs between syntactic complexity and fluency, Eric demonstrated consistent gains in both dimensions over the semester. In the fourth interview, Eric attributed his advancement to his engagement in preparing for an English writing competition, particularly in crafting argumentative essays.

Well, I’ve been preparing for an English writing contest this semester. Um, I wrote argumentative essays every week, really focusing on composing powerful arguments and convincing opinions. I think this training improved my critical thinking ability, and so it helped me come up with opinions quickly in oral tasks. (Eric, 4th interview)

Eric’s anecdotal account suggests that this external experience eased the cognitive demands of speech planning, contributing to a more fluent delivery. While this is an observation from a single participant, it aligns with broader theories on how individual learners’ recent language experience, among a range of factors, dynamically shapes their L2 performance (Larsen-Freeman, 2006; Verspoor and Behrens, 2011).

In the broader educational context, temporal and situational variability—such as learner fatigue—represents a fourth potential influence on CAF development. The observed drop in syntactic complexity, especially in the last week, was likely a consequence of the sustained task demands of this project throughout the semester. Learner fatigue was proposed as a contributing factor in L2 development (Verspoor & van Dijk, 2011). Similarly, burnout was recognized as contributing to decreased syntactic complexity at the end of an academic year (Zheng & Feng, 2017). Further anecdotal evidence from our study supports this: both Eric and Alex reported in the fourth interview feeling “tired and stressed” during exam weeks, a period when they had to manage project recordings alongside final exams and term papers.

Conclusion

This study explored the development and interaction of CAF in advanced Chinese EFL learners’ oral production. Our analyses revealed the asynchronous pattern of development across these three dimensions. Specifically, lexical diversity initially decreased but later showed a recovery, while overall syntactic complexity declined. Accuracy generally improved, whereas fluency demonstrated a decreasing trend. Besides, the study revealed that while fluency and syntactic complexity supported each other, accuracy often competed with either complexity or fluency. This variability in development and interaction was largely influenced by factors such as cognitive resource availability, initial L2 proficiency level, educational context, and fatigue. Beyond these influencing factors, the study also highlighted the potential benefit of supplemental training as a complement to formal instruction.

Our findings offer valuable theoretical and pedagogical implications. Theoretically, the results empirically support the view of L2 oral development as a non-linear, adaptive process characterized by the dynamic interplay among language subsystems (Larsen-Freeman, 2006; de Bot, 2008). Specifically, we observed varying interactions between fluency, complexity, and accuracy, highlighting the complex and interconnected nature of language development, characteristic of advanced Chinese EFL learners. These nuanced insights drawn from our study represent a novel theoretical contribution.

Pedagogically, this understanding underscores the importance of recognizing the adaptive, personalized nature of language learning. To effectively apply this insight, educators should adopt pedagogical approaches that cater to individual learners’ needs. These could include implementing curricula with varied task types to foster vocabulary and syntactic development, and providing feedback that addresses both progress and the strategic choices learners make to help them navigate fluctuating performance. Additionally, designing classroom activities that foster communicative fluency and purposeful language use, rather than prioritizing immediate accuracy or grammatical complexity, can support more authentic language development. Given the significant impact of cognitive load on oral performance, instructors should also aim to reduce unnecessary cognitive strain during speaking tasks. For instance, scaffolding complex tasks into manageable steps (e.g., providing pre-task vocabulary preparation or guided outlines), allowing flexible planning time tailored to learners’ proficiency levels, or avoiding overly demanding tasks (such as tight time limits or overly difficult topics) that could hinder meaningful communication and overburden cognitive resources.

It should be noted that our conclusions drawn regarding developmental features are primarily based on visual inspection and would benefit from the integration of statistical analysis. Moreover, given the relatively small sample size of our study, future research could employ a larger cohort to enhance the generalizability of our findings. Extending the observation period, for example, to a full academic year, would also provide more comprehensive insights into L2 oral development. This longer timeframe would facilitate the differentiation between fluctuations characteristic of developmental reorganization and those influenced by temporary contextual effects. In addition, including within and between clause pauses could have provided more revealing insights into fluency development and its developmental interaction with other CAF aspects. Finally, researchers should carefully select measurements appropriate for their specific research context and objectives. As Skehan (2009) cautions, dimensions such as fluency are especially sensitive to environmental influence on language use.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bulté B, Housen A (2020) A critical appraisal of the CDST approach to investigating linguistic complexity in L2 writing development. In: Fogal G, Verspoor M (eds) Complex Dynamic Systems Theory and L2 Writing Development, John Benjamins,. Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 207–238. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.54

Chan P, Verspoor M, Vahtrick L (2015) Dynamic development in speaking versus writing in identical twins. Lang Learn 65(2):298–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12107

de Bot K (2008) Introduction: second language development as a dynamic process. Mod Lang J 92(2):166–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00712.x

Foster P, Tonkyn A, Wigglesworth G (2000) Measuring spoken language: a unit for all reasons. Appl Linguist 21(3):354–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.3.354

Hepford E (2017) Dynamic second language development: the interaction of complexity, accuracy, and fluency in a naturalistic learning context. Dissertation, Temple University

Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH (2016) A dynamic ensemble for second language research: putting complexity theory into practice. Mod Lang J 100(4):741–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12347

Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH, Evan R (2022) Complex dynamic systems theory in language learning: a scoping review of 25 years of research. Stud Second Lang Acquis 44:913–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000553

Housen A, Kuiken F, Vedder I (eds) (2012) Dimensions of L2 performance and proficiency: complexity, accuracy and fluency in SLA. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.32

Larsen-Freeman D (2006) The emergence of complexity, fluency, and accuracy in the oral and written production of five Chinese learners of English. Appl Linguist 27(4):590–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/aml029

Larsen-Freeman D, Cameron L (2008) Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2007.00148.x

Leonard KR, Shea CE (2017) L2 speaking development during study abroad: fluency, accuracy, complexity, and underlying cognitive factors. Mod Lang J 101(1):179–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12382

Li CY, Xu JF (2023) The sustainability of form-focused instruction in classrooms: Chinese secondary school EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices. Sustainability 15(7):6109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076109

Lowie W, Caspi T, van Geert P, Steenbeek H (2011) Modeling development and change. In: Verspoor M, de Bot K, Lowie W (eds) A dynamic approach to second language development: methods and techniques. John Benjamins, Philadelphia/Amsterdam, p 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.29

Lowie W, Verspoor M (2022) A complex dynamic systems theory perspective on speaking in second language development. In: Derwing T, Munro M, Thomson R (eds) The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and speaking. Routledge, p 39–53. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003022497

Lu XF (2012) The relationship of lexical richness to the quality of ESL learners’ oral narratives. Mod Lang J 96(ii):190–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01232.x

MacWhinney B (2000) The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk: Transcription format and programs, 3rd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Norris JM, Ortega L (2009) Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: the case of complexity. Appl Linguist 30(4):555–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp044

Ortega L, Byrnes H (2008) The longitudinal study of advanced L2 capabilities. Routledge, New York

Polat B, Kim Y (2014) Dynamics of complexity and accuracy: a longitudinal case study of advanced untutored development. Appl Linguist 35(2):184–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt013

Raupach M (1980) Temporal variables in first and second language speech production. In: Dechert HW, Raupach M (eds) Temporal variables in speech. De Gruyter Mouton, p 263–270

Skehan P (1998) A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.5070/L4111005027

Skehan P (2009) Modelling second language performance: integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency, and lexis. Appl Linguist 30(4):510–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp047

Skehan P, Foster P (1999) The influence of task structure and processing conditions on narrative retellings. Lang Learn 49(1):93–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00071

Spoelman M, Verspoor MH (2010) Dynamic patterns in the development of accuracy and complexity: a longitudinal case study on the acquisition of Finnish. Appl Linguist31(4):532–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amq001

van Dijk M, Verspoor M, Lowie W (2011) Variability and DST. In: Verspoor M, de Bot K, Lowie W (eds) A Dynamic approach to second language development: methods and techniques. John Benjamins, Philadelphia/Amsterdam, p 55–84. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.29

Vercellotti ML (2017) The development of complexity, accuracy, and fluency in second language performance: a longitudinal study. Appl Linguist 38(1):90–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv002

Verspoor M, Behrens H (2011) Dynamic systems theory and a usage-based approach to second language development. In: Verspoor M, de Bot K, Lowie W (eds) A dynamic approach to second language development: methods and techniques. John Benjamins, Philadelphia/Amsterdam, p 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.29

Verspoor M, van Dijk M (2011) Visualizing interactions between variables. In: Verspoor M, de Bot K, Lowie W (eds) A dynamic approach to second language development: methods and techniques. John Benjamins, Philadelphia/Amsterdam, p 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.29

Wang Y, Tao SC (2020) The dynamic co-development of linguistic and discourse-semantic complexity in advanced L2 writing. In: Fogal GG, Verspoor MH (eds) Complex dynamic systems theory and L2 writing development. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1075/lll5.54

Yu HJ (2020) A dynamic study of Chinese English learners’ oral language fluency development and CAF interactions. Foreign Lang World 197(2):81–89

Yu HJ, Lowie W (2020) Dynamic paths of complexity and accuracy in second language speech: a longitudinal case study of Chinese learners. Appl Linguist 41(6):855–877. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz040

Yu HJ, Peng HY (2024) Developmental dynamics in oral fluency and learner motivation: a dual-focus approach. Int J Appl Linguist 34(4):1401–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12577

Yuan F, Ellis R (2003) The effects of pre-task planning and on-line planning on fluency, complexity and accuracy in L2 monologic oral production. Appl Linguist 24(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/24.1.1

Zheng YY (2012) Exploring long-term productive vocabulary development in an EFL context: the role of motivation. System 40:104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.01.007

Zheng YY, Feng YL (2017) A dynamic systems study on Chinese EFL learners’ syntactic and lexical complexity development. Mod Foreign Lang 40(1):57–63

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu Wang was responsible for research design, draft writing, and revision. Kailu Wang was responsible for data collection and data analysis. Li Tao was responsible for revising the draft. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was granted approval by the Academic Committee of the School of Foreign Languages at Soochow University (September 2, 2022; No. 2022010611), which is responsible for the ethical review of all research projects conducted by faculty of the school. All procedures in this study were designed and implemented in line with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The scope of the approval covered all aspects of the study.

Informed consent

Prior to participation, all participants were informed about the research purpose, the procedures involved, the scope of data use, the measures for data protection, the potential publication of anonymized findings, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants between September 6 and September 9, 2022, ensuring voluntary participation and confidentiality of responses. The study information and consent form were presented on the first page of the questionnaire using the online platform Wenjuanxing. Participants indicated their informed consent by choosing to proceed with the questionnaire, and they retained the option to withdraw at any time according to their preference.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wang, K. & Tao, L. The developmental dynamics of complexity, accuracy, and fluency in advanced Chinese EFL learners’ oral production. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 2000 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06321-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06321-6